Townsend C.R., Begon M., Harper J.L. Essentials of Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

necessary for tree functioning, plants also depend critically on actual water

availability. Indeed, energy and water availability inevitably interact, since higher

energy inputs lead to more evapotranspiration and a greater requirement for

water (Whittaker et al., 2003). Thus, in a study of southern African trees, species

richness increased with water availability (annual rainfall), but first increased and

then decreased with available energy (PET; Figure 10.4b). Such hump-shaped

richness patterns will be a recurring feature in this chapter.

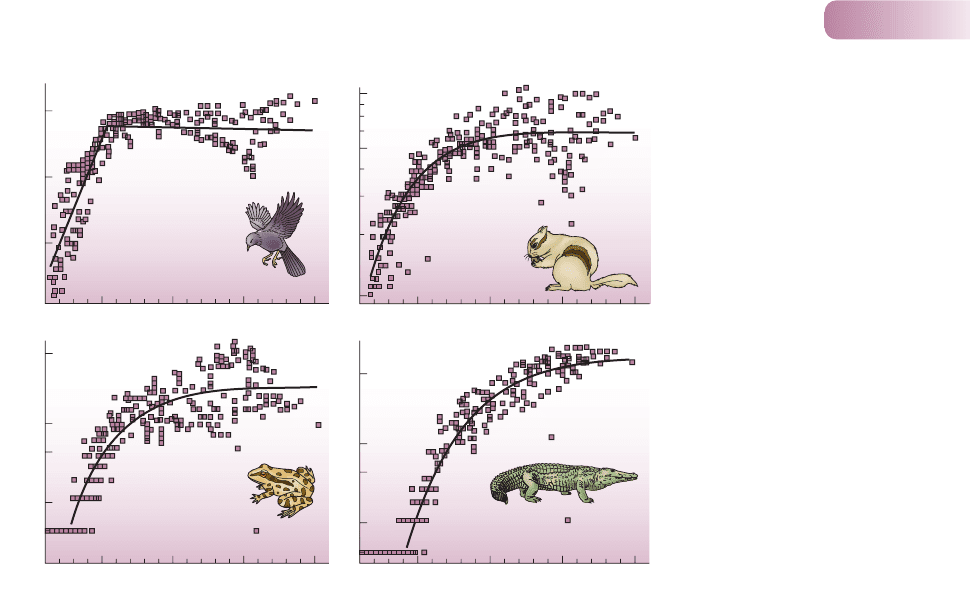

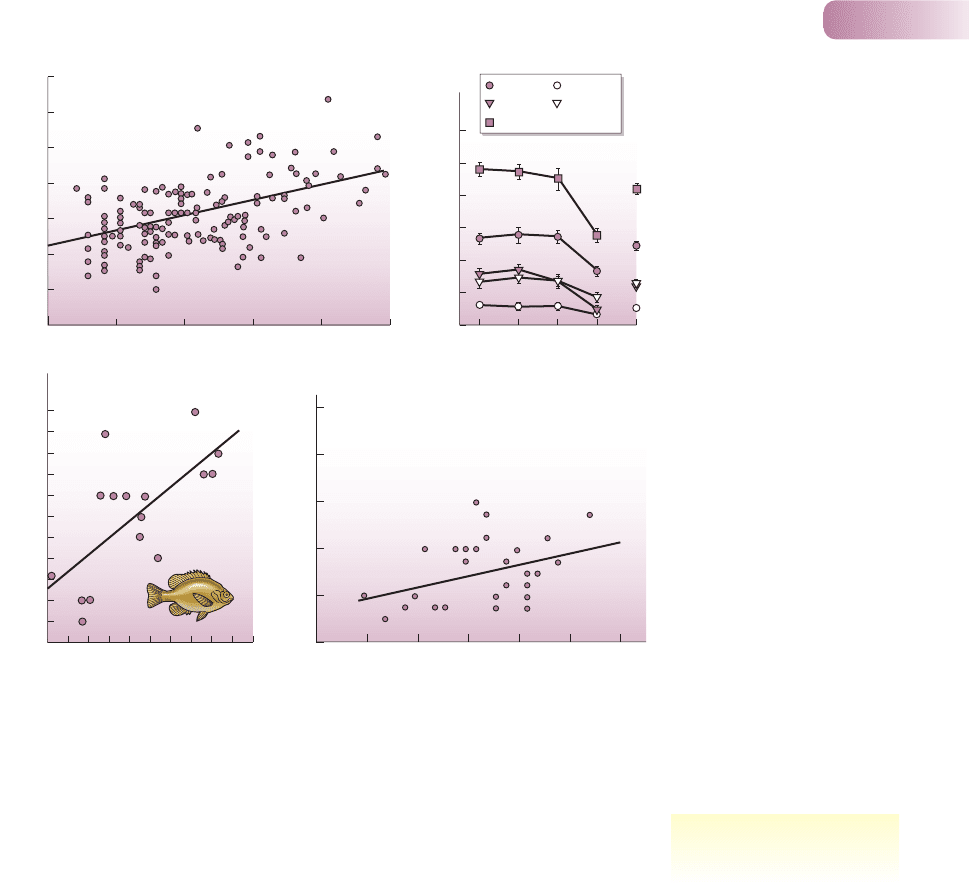

When the North American work (Figure 10.4a) was extended to four verte-

brate groups, species richness correlated to some extent with tree species richness

itself. However, the best correlations were consistently with PET (Figure 10.5).

Why should animal species richness be positively correlated with crude atmo-

spheric energy? The answer is not known with any certainty, but it may be because

for an ectotherm, such as a reptile, extra atmospheric warmth would enhance

the intake and utilization of food resources; while for an endotherm, such as a

bird, the extra warmth would mean less expenditure of resources in maintaining

body temperature and more available for growth and reproduction. In both cases,

then, this could lead to faster individual and population growth and thus to larger

populations. Warmer environments might therefore allow species with narrower

niches to persist and such environments may therefore support more species in

total (Turner et al., 1996) (see Figure 10.3b).

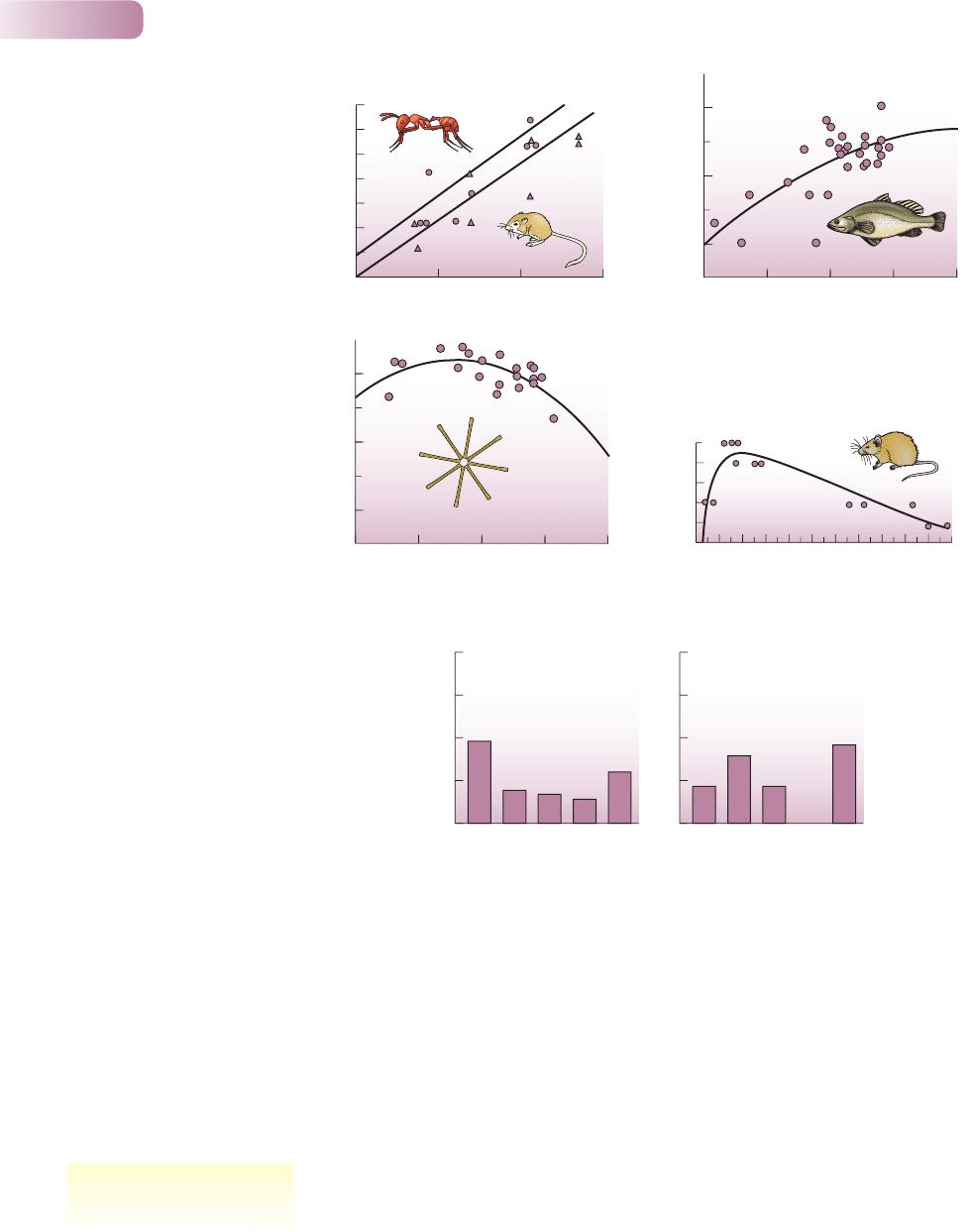

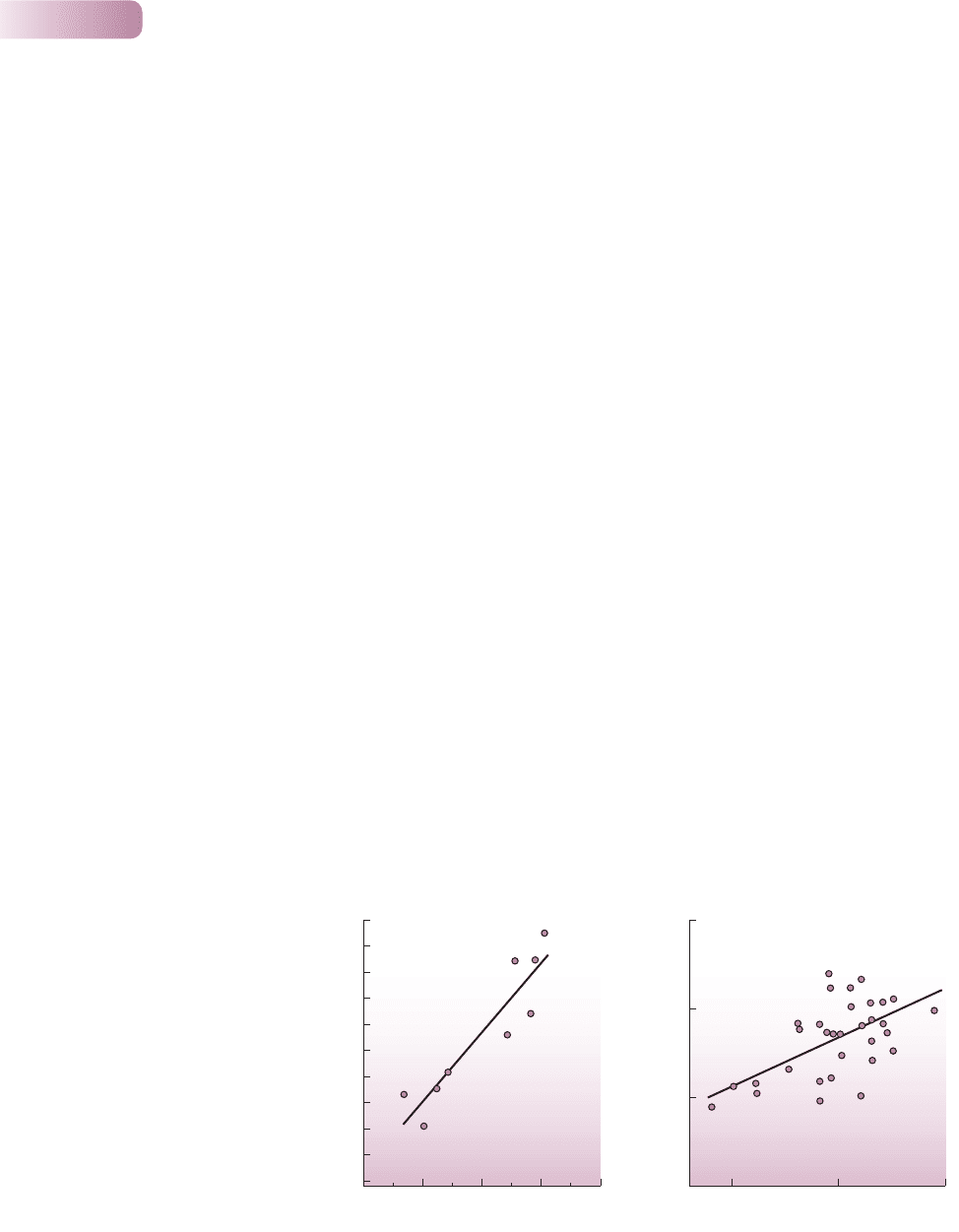

Sometimes there seems to be a direct relationship between animal species rich-

ness and plant productivity. Thus, there are strong positive correlations between

species richness and precipitation for both seed-eating ants and seed-eating

rodents in the southwestern deserts of the United States (Figure 10.6a). In such

arid regions, it is well established that mean annual precipitation is closely related

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

329

200

100

50

90

50

10

50

10

5

1

0

50

10

5

1

0

500 1000 1500 2000500 1000 1500 2000

500 1000 1500 2000500 1000 1500 2000

(a)

(b)

(c) (d)

Species richness

Potential evapotranspiration (mm yr

–1

)

Figure 10.5

Species richness of: (a) birds,

(b) mammals, (c) amphibians

and (d) reptiles in North America

in relation to potential

evapotranspiration.

AFTER CURRIE, 1991

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 329

to plant productivity and thus to the amount of seed resource available. It is

particularly noteworthy that in species-rich sites, the communities contain more

species of very large ants (which consume large seeds) and more species of very

small ants (which take small seeds) (Davidson, 1977). It seems that either the range

of seed sizes is greater in the more productive environments (Figure 10.3a) or

the abundance of seeds becomes sufficient to support extra consumer species with

narrower niches (Figure 10.3b). The species richness of fish in North American

lakes also increases with an increase in productivity of the lake’s phytoplankton

(Figure 10.6b).

On the other hand, an increase in diversity with productivity is by no means

universal, as shown for example, by the unique experiment that started in 1856

at Rothamsted in England (see Box 10.1). An 8 acre pasture was divided into

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

330

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Number of common species

Mean annual precipitation (mm)

100 200 300

(a)

5

4

3

2

1

0

Rainfall (mm)

660600480360120 180 300 420 54060 240

(d)

(e)

Percentage of studies

Productivity–diversity patterns

60

40

20

0

80

60

40

20

0

80

Humped

Positive

Negative

U-shape

None

Animals

Humped

Positive

Negative

U-shape

None

Vascular plants

(b)

431

0

0

1

2

2

431

0

0

1

2

2

(c)

Species richness (log

10

scale)

Species richness (log

10

scale)

n = 39 n = 23

Primary productivity

(mg C m

–2

yr

–1

; log

10

scale)

Primary productivity

(mg C m

–2

yr

–1

; log

10

scale)

Number of

rodent species

Figure 10.6

Relationships between species

richness and productivity. Where

best-fit lines are shown (see

Box 1.2), each is statistically

significant. (a) The species richness

of seed-eating rodents (triangles)

and ants (circles) inhabiting sandy

soils increased along a geographic

gradient of increasing precipitation

and, therefore, of increasing

productivity. (b) Species richness

of fish increased with primary

productivity of phytoplankton in a

series of North American lakes,

while (c) species richness of the

phytoplankton themselves showed a

hump-shaped relationship, increasing

with productivity when productivity

was low, but declining at higher

levels. (d) Species richness of desert

rodents also showed a hump-shaped

relationship when plotted against

annual rainfall. (e) Percentage of

published studies on plants and

animals showing various patterns

between species richness and

productivity. All conceivable patterns

have been detected, but hump-

shaped and positive patterns, such

as those shown in (a) to (d), are

well represented. However, it is

not uncommon for no pattern to

be documented.

(a) AFTER BROWN & DAVIDSON, 1977; (b, c) AFTER DODSON ET AL., 2000; (d) AFTER ABRAMSKY & ROSENZWEIG, 1983; (e) AFTER MITTELBACH ET AL., 2001

other evidence shows richness

declining with productivity...

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 330

20 plots, two serving as controls and the others receiving a fertilizer treatment

once a year. While the unfertilized areas remained essentially unchanged, the

fertilized areas showed a progressive decline in species richness (and diversity).

Such declines have long been recognized. Rosenzweig (1971) referred to them

as illustrating “the paradox of enrichment”. One possible resolution of the paradox

is that high productivity leads to high rates of population growth, bringing about

the extinction of some of the species present because of a speedy conclusion to

any potential competitive exclusion (see Section 6.2.7). At lower productivity,

the environment is more likely to have changed before competitive exclusion is

achieved. An association between high productivity and low species richness has

been found in several other studies of plant communities (reviewed by Tilman,

1986). It can be seen, for example, where human activities lead to an increased

input of plant resources like nitrates and phosphates into lakes, rivers, estuaries

and coastal marine regions; when such ‘cultural eutrophication’ is severe, we con-

sistently see a decrease in species richness of phytoplankton (despite an increase

in their productivity).

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that several studies have demonstrated

both an increase and a decrease in richness with increasing productivity – that

is, that species richness may be highest at intermediate levels of productivity.

Species richness declines at the lowest productivities because of a shortage

of resources, but also declines at the highest productivities where competitive

exclusions speed rapidly to their conclusion. For instance, there are humped

curves when the number of lake phytoplankton species is plotted against over-

all phytoplankton productivity (Figure 10.6c; the decline at higher productivity

is analogous to the cultural eutrophication mentioned above) and when the

species richness of desert rodents is plotted against precipitation (and thus

productivity) along a geographic gradient in Israel (Figure 10.6d). Indeed, an

analysis of a wide range of such studies found that when communities differing

in productivity but of the same general type (e.g. tallgrass prairie) were compared

(Figure 10.6e), a positive relationship was the most common finding in animal

studies (with fair numbers of humped and negative relationships), whereas with

plants, humped relationships were most common, with smaller numbers of posit-

ives and negatives (and even some U-shaped curves – cause unknown!). Clearly,

increased productivity can and does lead to increased or decreased species richness

– or both.

10.3.2 Predation intensity

The possible effects of predation on the species richness of a community were

examined in Chapter 7: predation may increase richness by allowing otherwise

competitively inferior species to coexist with their superiors (predator-mediated

coexistence); but intense predation may reduce richness by driving prey species

(whether or not they are strong competitors) to extinction. Overall, therefore,

there may also be a humped relationship between predation intensity and species

richness in a community, with greatest richness at intermediate intensities, such

as that shown by the effects of cattle grazing (illustrated in Figure 7.24).

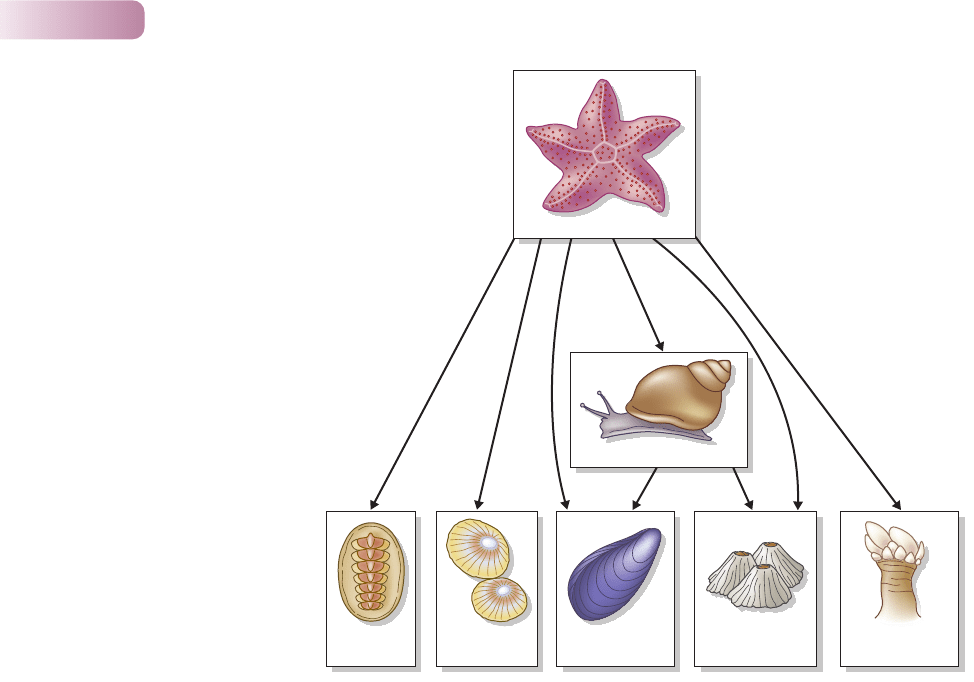

A classic example of predator-mediated coexistence is provided by a study that

established the concept in the first place: the work of Paine (1966) on the influ-

ence of a top carnivore on community structure on a rocky shore (Figure 10.7).

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

331

. . . and further evidence

suggests a ‘humped’ relationship

predator-mediated coexistence

by starfish on a rocky shore

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 331

The starfish Pisaster ochraceus preys on sessile filter-feeding barnacles and

mussels, and also on browsing limpets and chitons and a small carnivorous whelk.

These species, together with a sponge and four macroscopic algae (seaweeds),

form a typical community on rocky shores of the Pacific coast of North America.

Paine removed all starfish from a stretch of shoreline about 8 m long and 2 m

deep and continued to exclude them for several years. The structure of the

community in nearby control areas remained unchanged during the study, but

the removal of Pisaster had dramatic consequences. Within a few months, the

barnacle Balanus glandula settled successfully. Later mussels (Mytilus californicus)

crowded it out, and eventually the site became dominated by these. All but

one of the species of alga disappeared, apparently through lack of space, and

the browsers tended to move away, partly because space was limited and partly

because there was a lack of suitable food. The main influence of the starfish

Pisaster appears to be to make space available for competitively subordinate

species. It cuts a swathe free of barnacles and, most importantly, free of the

dominant mussels that would otherwise outcompete other invertebrates and

algae for space. Overall, there is usually predator (starfish)-mediated coexistence,

but the removal of starfish led to a reduction in number of species from 15

to eight. The concept of predator-mediated coexistence is not only intrinsically

interesting; it also finds a surprising application in the field of restoration ecology

(Box 10.2).

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

332

Pisaster (starfish)

Thais (whelk) 1 sp.

Chitons

2 spp.

Limpets

2 spp.

Mytilus (bivalve)

1 sp.

Acorn barnacles

3 spp.

Mitella

(goose barnacle)

Figure 10.7

Paine’s rocky shore community. The

profound influence of the predatory

starfish could only be detected by

removing them. In the absence of

Pisaster, other species became

dominant (first barnacles and then

mussels) leading to an overall

reduction in species richness. This is

a classic case of predator-mediated

coexistence.

AFTER PAINE, 1966

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 332

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

333

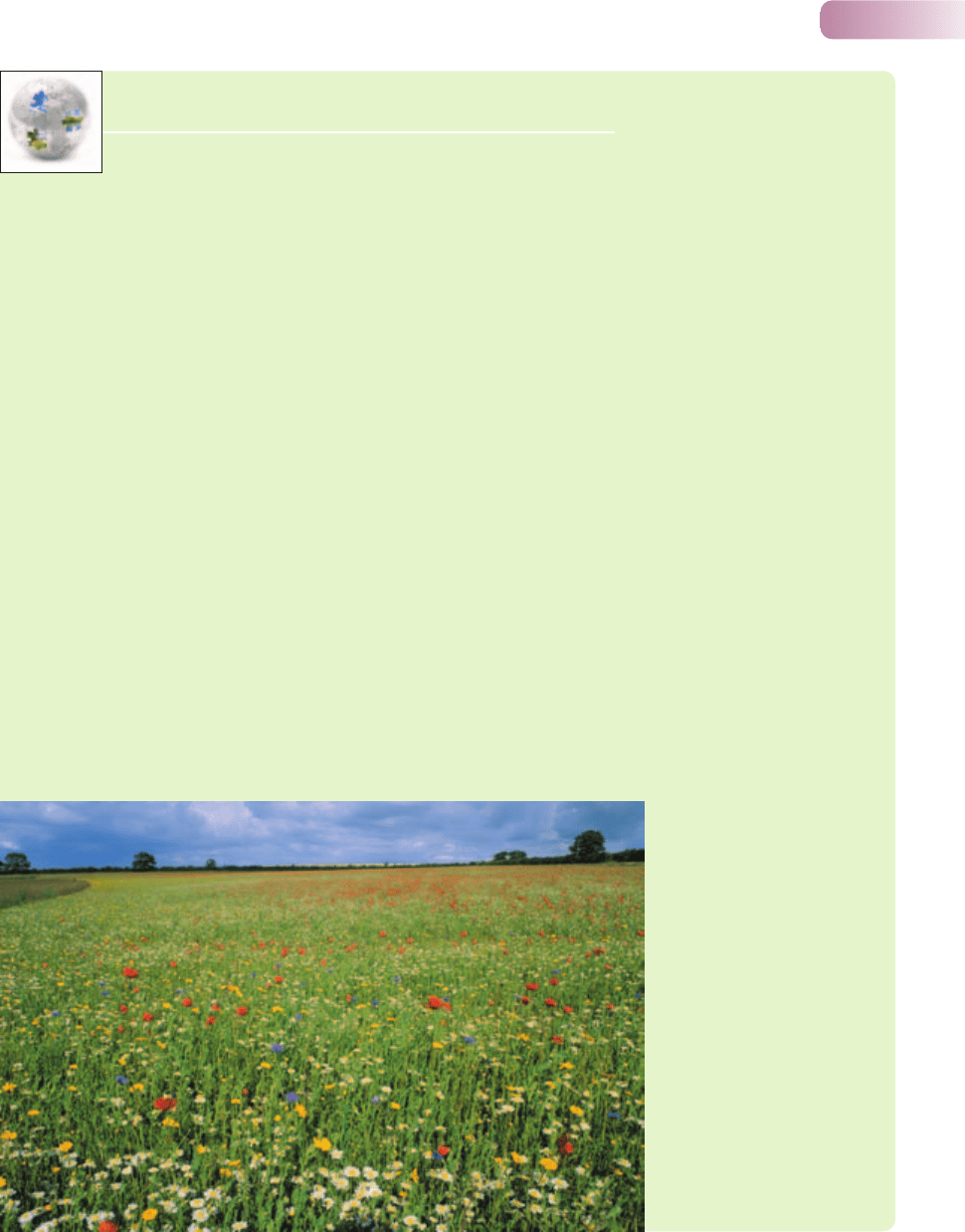

10.2 TOPICAL ECONCERNS

10.2 Topical ECOncerns

Species-rich meadows are now uncommon in agri-

cultural landscapes in Europe because decades

of intensive fertilizer application have allowed a few

species to competitively exclude others, a pattern

that echoes the results of the remarkable century-

long Rothamsted experiment (see Figure 10.1).

It is not uncommon nowadays for attempts to

be made to restore the lost species richness of

these pasture settings. One approach is to use

what we know about predator-mediated coexistence

or, more generally, exploiter-mediated coexistence.

This occurs when one species ‘exploits’ as food a

number of species in the community, reducing the

dominance of the most competitively superior species

and allowing less competitive species to maintain a

foothold.

One example of exploiter-mediated coexistence

occurs when parasites exert a leveling effect. Rhinanthus

minor, an annual plant, is capable of its own limited

photosynthesis but is known as a ‘hemiparasite’

because it typically taps into the photosynthetic

products of other plants by building connections with

their roots. Researchers reasoned that the presence

of the hemiparasite might facilitate recovery to

species-rich grassland via exploiter-mediated coexis-

tence (Pywell et al., 2004). To test this hypothesis in

an agriculturally impoverished grassland, they estab-

lished experimental plots with various densities of

Rhinanthus minor. After the hemiparasite populations

had become established, the researchers sowed a

mixture of seeds of 10 native wildflower species

that had been lost from the grassland as a result of

intensive agriculture. After 2 years the hemiparasite

was found to have suppressed the growth of the

parasitized plants and this led, the following year, to

the desired increase in grassland species richness

because competitive exclusion had been circumvented

(Figure 10.8).

Using exploiter-mediated coexistence to assist grassland

restoration

A species-rich flower meadow

© ALAMY IMAGES A4T6HC

s

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 333

10.3.3 Spatial heterogeneity

Environments that are more spatially heterogeneous can be expected to accom-

modate extra species because they provide a greater variety of microhabitats,

a greater range of microclimates, more types of places to hide from predators,

and so on. In effect, the extent of the resource spectrum is increased (see

Figure 10.3a).

In some cases, it has been possible to relate species richness to the spatial hetero-

geneity of the abiotic environment. For instance, a study of plant species growing

in 51 plots alongside the Hood River, Canada, revealed a positive relationship

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

334

An understanding of exploiter-mediated coexistence

holds promise for future meadow restoration efforts.

Can you think of any other aspects of the theory of

species richness that could be applied to the benefit

of impoverished grasslands? (Clue – check out the

‘intermediate disturbance hypothesis’, described in

Section 10.4.2. These intensively farmed landscapes

have also been subject to regular and intensive dis-

turbances caused by heavy mowing or grazing. What

might the intermediate disturbance hypothesis have to

offer in restoring grassland species richness?)

s

Figure 10.8

Relationship between frequency of occurrence of the hemiparasite Rhinanthus minor and species richness of plants per

experimental plot of grassland. The presence of the hemiparasite leads to lower plant height, because of reduced success of

the parasitized plants, and the following year to increased species richness because of suppression of competitive exclusion

by the dominant species.

(LEFT) © ALAMY IMAGES A02Y49; (RIGHT) AFTER PYWELL ET AL., 2004

richness and the heterogeneity

of the abiotic environment

10

8

100200406080

6

4

2

0

Cumulative richness per plot in 2002

Frequency of Rhinanthus per m

2

in 2001 (%)

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 334

between species richness and an index of spatial heterogeneity (based, among

other things, on the number of categories of substrate, slope, drainage regimes

and soil pH present) (Figure 10.9a).

Most studies of spatial heterogeneity, though, have related the species richness of

animals to the structural diversity of the plants in their environment, either as a result

of experimental manipulation of the plants, as with the spiders in Figure 10.9b,

but more commonly through comparisons of natural communities that differ in

plant structural diversity (Figure 10.9c) or plant species richness (where higher

species richness equates to greater spatial heterogeneity; Figure 10.9d).

Whether spatial heterogeneity arises from the abiotic environment or is pro-

vided by biological components of the community, it is capable of promoting an

increase in species richness.

10.3.4 Environmental harshness

Environments dominated by an extreme abiotic factor – often called harsh

environments – are more difficult to recognize than might be immediately apparent.

An anthropocentric view might describe as extreme both very cold and very hot

habitats, unusually alkaline lakes and grossly polluted rivers. However, species

have evolved and live in all such environments, and what is very cold and extreme

for us must seem benign and unremarkable to a penguin.

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

335

30

26

22

18

14

10

10 15 25 35

Ant species richness

(d)

20 30 40

Aug 6

(b)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Sep 5

Oct 2

Oct 22

0 2.0

Index of vegetation diversity

11

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6

(c)

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0.1 0.2 0.3

Index of environmental heterogeneity

0.4 0.5 0.6

Number of vascular plant species

(a)

Date

Number of spider species per branch

Seasonal

mean

Number of fish species

Tree species richness

Control Bare

Patchy

Thinned

Tied

Figure 10.9

(a) Relationship between the number

of plants per 300 m

2

plot beside the

Hood River, Northwest Territories,

Canada, and an index (ranging from

0 to 1) of spatial heterogeneity in

abiotic factors associated with

topography and soil. (b) In an

experimental study, the number of

spider species living on Douglas

fir branches increased with their

structural diversity. Those ‘bare’,

‘patchy’ or ‘thinned’ were less

diverse than normal (‘control’) by

virtue of having needles removed;

those ‘tied’ were more diverse

because their twigs were entwined

together. (c) Relationship between

animal species richness and an index

of structural diversity of vegetation

for freshwater fish in 18 Wisconsin

lakes. (d) Relationship between

arboreal ant species richness in

Brazilian savanna and the species

richness of trees (a surrogate for

spatial heterogeneity).

(a) AFTER GOULD & WALKER, 1997; (b) AFTER HALAJ ET AL., 2000; (c) AFTER TONN & MAGNUSON, 1982; (d) AFTER RIBAS ET AL., 2003

animal richness and plant spatial

heterogeneity

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 335

We might try to get around the problem of defining environmental harshness

by ‘letting the organisms decide’. An environment may be classified as extreme

if organisms, by their failure to live there, show it to be so. But if the claim is to

be made – as it often is – that species richness is lower in extreme environments,

then this definition is circular, and it is designed to prove the very claim we wish

to test.

Perhaps the most reasonable definition of an extreme condition is one that

requires, of any organism tolerating it, a morphological structure or biochem-

ical mechanism that is not found in most related species and is costly, either

in energetic terms or in terms of the compensatory changes in the biological

processes of the organism that are needed to accommodate it. For example,

plants living in highly acidic soils (low pH) may be affected directly through injury

by hydrogen ions or indirectly via deficiencies in the availability and uptake

of important resources such as phosphorus, magnesium and calcium. In addition,

aluminum, manganese and heavy metals may have their solubility increased to toxic

levels. Moreover, the activity of symbiotic fungi (mycorrhizas enhancing uptake

of dissolved nutrients – see Section 8.4.5) or bacteria (fixation of atmospheric

nitrogen – see Section 8.4.6) may be impaired. Plants can only tolerate low pH if

they have specific structures or mechanisms allowing them to avoid or counteract

these effects.

Environments that experience low pHs can thus be considered harsh, and the

mean number of plant species recorded per sampling unit in a study in the

Alaskan Arctic tundra was indeed lowest in soils of low pH (Figure 10.10a).

Similarly, the species richness of benthic (bottom-dwelling) invertebrates in

streams in southern England was markedly lower in the more acidic streams

(Figure 10.10b). Further examples of extreme environments that are associated

with low species richness include hot springs, caves and highly saline water

bodies such as the Dead Sea. The problem with these examples, however, is that

each is also characterized by other features associated with low species richness,

such as low productivity and low spatial heterogeneity. In addition, many occupy

small areas (caves, hot springs) or areas that are rare compared to other types of

habitat (only a small proportion of the streams in southern England are acidic).

Hence extreme environments can often be seen as small and isolated islands.

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

336

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

34567

Species richness

Soil pH

567

Mean stream pH

60

Number of invertebrate taxa

40

20

0

(a) (b)

Figure 10.10

(a) The number of plant species in

the Alaskan Arctic tundra increases

with soil pH. (b) The number of taxa

of invertebrates in streams in

southern England increases with the

pH of stream water.

(a) AFTER GOUGH ET AL., 2000; (b) AFTER TOWNSEND ET AL., 1983

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 336

We will see in Section 10.5.1 that these features, too, are usually associated with

low species richness. Although it appears reasonable that intrinsically extreme

environments should as a consequence support few species, this has proved an

extremely difficult proposition to establish.

10.4 Temporally varying factors that

influence species richness

Temporal variation in conditions and resources may be predictable or unpredict-

able and operate on time scales from minutes through to centuries and millennia.

All may influence species richness in profound ways.

10.4.1 Climatic variation

The effects of climatic variation on species richness depend on whether the

variation is predictable or unpredictable (measured on time scales that matter

to the organisms involved). In a predictable, seasonally changing environment,

different species may be suited to conditions at different times of the year.

More species might therefore be expected to coexist in a seasonal environment

than in a completely constant one (see Figure 10.3a). Different annual plants in

temperate regions, for instance, germinate, grow, flower and produce seeds at

different times during a seasonal cycle; while phytoplankton and zooplankton

pass through a seasonal succession in large, temperate lakes with a variety of

species dominating in turn as changing conditions and resources become suitable

for each.

On the other hand, there are opportunities for specialization in a non-seasonal

environment that do not exist in a seasonal environment. For example, it would

be difficult for a specialist fruit-eater to persist in a seasonal environment when

fruit is available for only a very limited portion of the year. But such specialization

is found repeatedly in non-seasonal, tropical environments where fruit of one

type or another is available continuously.

Unpredictable climatic variation (climatic instability) could have a number of

effects on species richness. On the one hand: (i) stable environments may be able

to support specialized species that would be unlikely to persist where conditions

or resources fluctuated dramatically (Figure 10.3b); (ii) stable environments are

more likely to be saturated with species (Figure 10.3d); and (iii) theory suggests

that a higher degree of niche overlap will be found in more stable environments

(Figure 10.3c). All these processes could increase species richness. On the other

hand, populations in a stable environment are more likely to reach their carrying

capacities, the community is more likely to be dominated by competition, and

species are therefore more likely to be excluded by competition (o¯ is smaller, see

Figure 10.3c).

Some studies seem to support the notion that species richness increases as

climatic variation decreases. For example, there is a significant negative relation-

ship between species richness and the range of monthly mean temperatures for

birds, mammals and gastropods that inhabit the West coast of North America

(from Panama in the south to Alaska in the north) (MacArthur, 1975). However,

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

337

temporal niche differentiation in

seasonal environments

specialization in non-seasonal

environments

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 337

this correlation does not prove causation, since there are many other things that

change between Panama and Alaska. There is no established relationship between

climatic instability and species richness.

10.4.2 Disturbance

Previously, in Section 9.4, the influence of disturbance on community structure

was examined, and it was demonstrated that when a disturbance opens up a gap,

and the community is dominance controlled (strong competitors can replace

residents), there tends in a community succession to be an initial increase in rich-

ness as a result of colonization, but a subsequent decline in richness as a result

of competitive exclusion.

If the frequency of disturbance is now superimposed on this picture, it seems

likely that very frequent disturbances will keep most patches in the early stages

of succession (where there are few species) but also that very rare disturbances

will allow most patches to become dominated by the best competitors (where

there are also few species). This suggests an intermediate disturbance hypothesis,

in which communities are expected to contain most species when the frequency

of disturbance is neither too high nor too low (Connell, 1978). The intermediate

disturbance hypothesis was originally proposed to account for patterns of rich-

ness in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. It has occupied a central place in

the development of ecological theory because all communities are subject to

disturbances that exhibit different frequencies and intensities.

Among a number of studies that have provided support for this hypothesis,

we turn first to a study of green and red algae on different-sized boulders on

the rocky shores of southern California (Sousa, 1979a, 1979b). Wave action

disturbs small boulders more frequently than larger ones; thus, small boulders

had a monthly probability of movement of 42%, intermediate-sized boulders

a probability of 9%, and large boulders a probability of only 0.1%. After a

disturbance clears space on a boulder, ephemeral green algae (Ulva spp.) are

quick to colonize, but later in the year several species of perennial red alga

feature in the succession, including Gelidium coulteri, Gigartina leptorhinchos,

Rhodoglossum affine and Gigartina canaliculata. The last of these gradually takes

over until within 2–3 years it dominates the community, tending to competitively

exclude the early and mid-successional species. G. canaliculata then persists

unless there is a further disturbance. Sousa found that algal species richness was

lowest on the frequently (F) disturbed small boulders – these were dominated

most often by Ulva. The highest levels of species richness were consistently

recorded on the intermediate boulder class (I), most of which held mixtures of

3–5 abundant species from all successional stages. Finally, species richness on the

rarely disturbed (R), largest boulders was lower than the intermediate class, with

a monoculture of G. canaliculata on some of them (Figure 10.11a).

Disturbances in small streams often take the form of bed movements during

periods of high discharge, and because of differences in flow regimes and in the

substrata of stream beds, some stream communities are disturbed more frequently

than others. This variation was assessed in 54 stream sites in the Taieri River in

New Zealand. The pattern of richness of macroinvertebrate species conformed to

the intermediate disturbance hypothesis (Figure 10.11b). Finally, in controlled

field experiments, natural phytoplankton communities in Lake Plußsee (north

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

338

the intermediate disturbance

hypothesis...

. . . supported by studies of algae

on boulders on a rocky shore...

. . . and from studies of

invertebrates in small streams

and plankton in lakes

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 338