Townsend C.R., Begon M., Harper J.L. Essentials of Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

feed back to promote further increases in species richness (predator-mediated

coexistence, Figure 10.3c), which provides further resources and more hetero-

geneity, and so on. In addition, temperature, humidity and wind speed show much

less temporal variation within a forest than in an exposed early successional stage,

and the enhanced constancy of the environment may provide a stability of condi-

tions and resources that permits specialist species to build up populations and

persist (Figure 10.3b). As with the other gradients, the interaction of many factors

makes it difficult to disentangle cause from effect. But with the successional gradient

of richness, the tangled web of cause and effect appears to be of the essence.

10.6 Patterns in taxon richness in the

fossil record

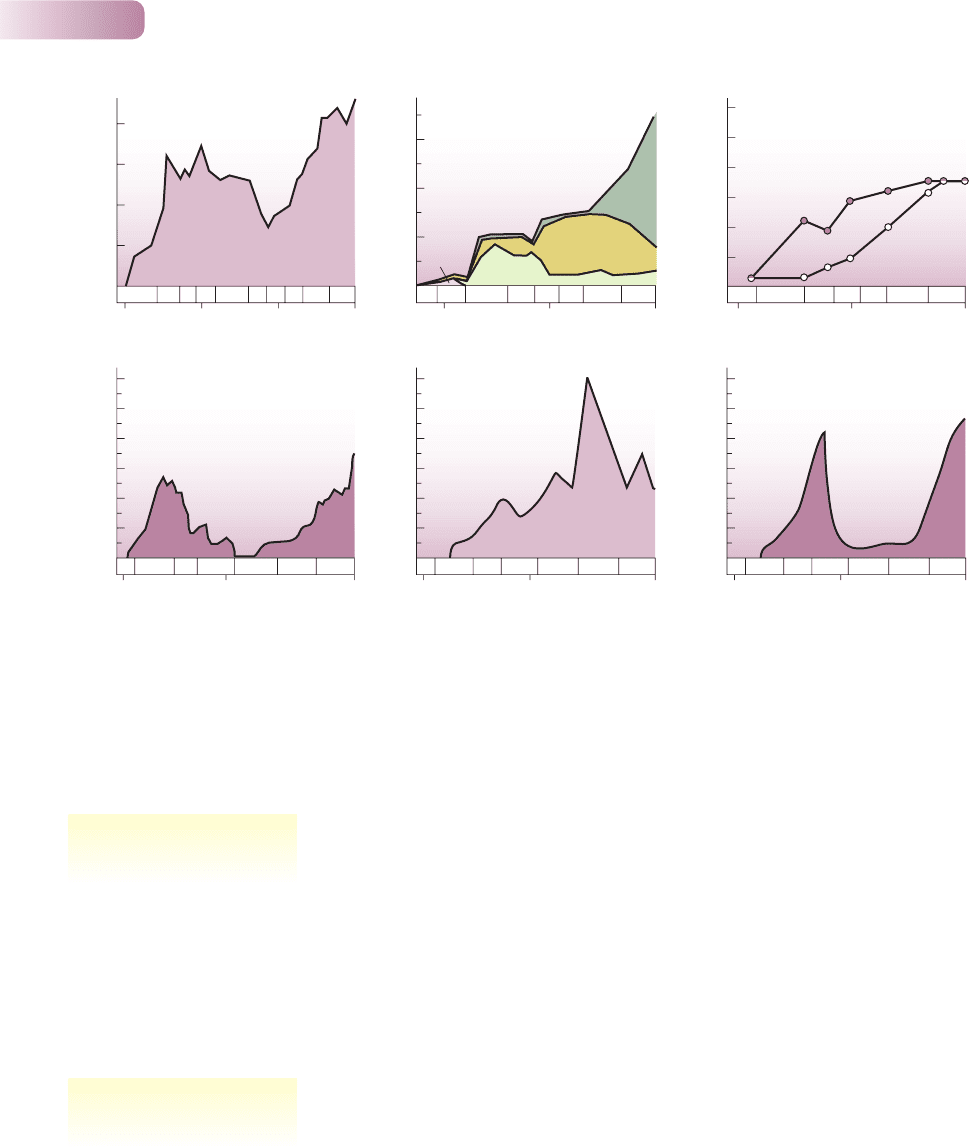

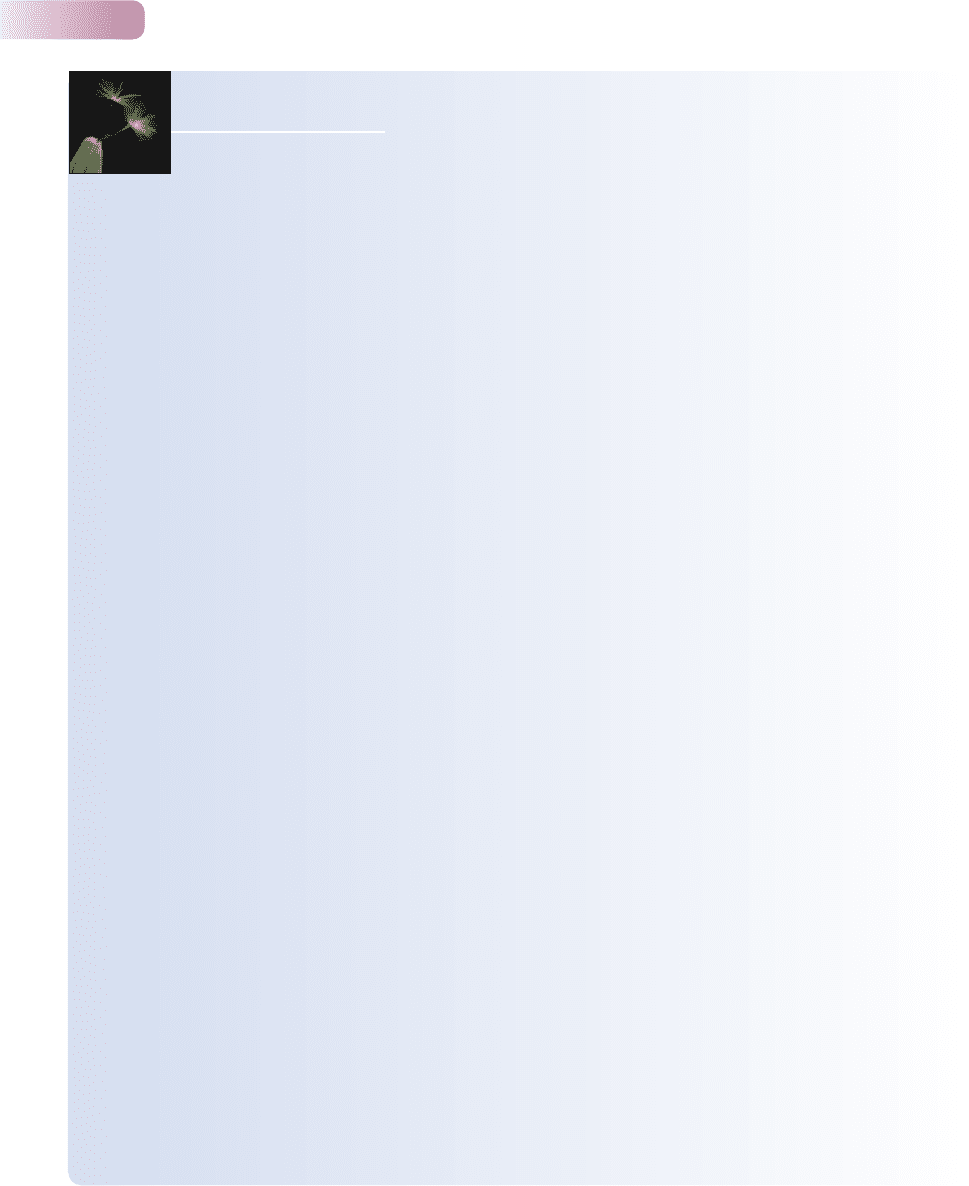

Finally, it is of interest to take the processes that are believed to be instrumental

in generating present-day gradients in richness and apply them to trends occurring

over much longer timespans. The imperfection of the fossil record has always been

the greatest impediment to the paleontological study of evolution. Nevertheless,

some general patterns have emerged, and our knowledge of six important groups

of organisms is summarized in Figure 10.21.

Until about 600 million years ago, the world was populated virtually only by

bacteria and algae, but then almost all the phyla of marine invertebrates entered

the fossil record within the space of only a few million years (Figure 10.21a). We

have seen that the introduction of a higher trophic level can increase richness at

a lower level by ‘exploiter-mediated coexistence’; thus, it can be argued that the

first single-celled herbivorous protist was probably instrumental in the Cambrian

explosion in species richness. The opening up of space by grazing on the algal mono-

culture, coupled with the availability of recently evolved eukaryotic cells, may have

caused the biggest burst of evolutionary diversification in the planet’s history.

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

349

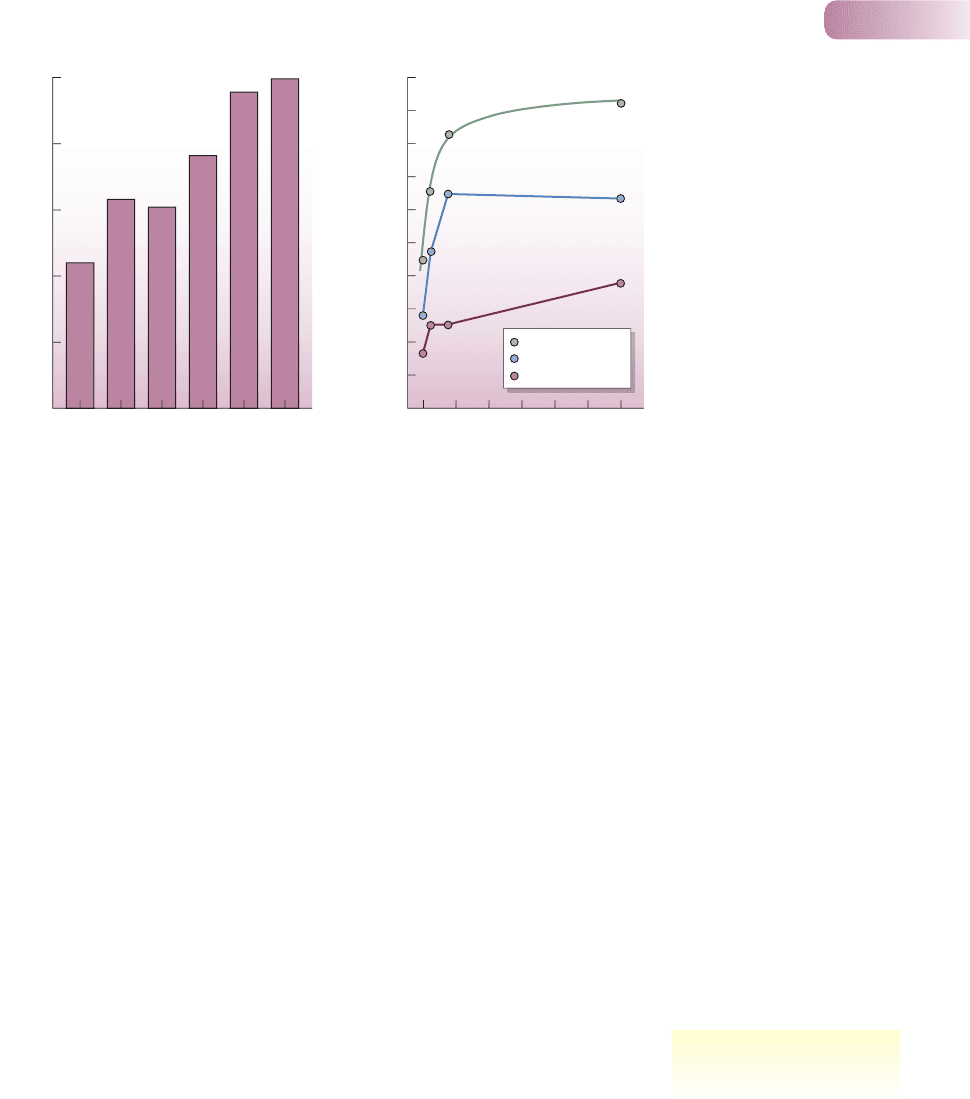

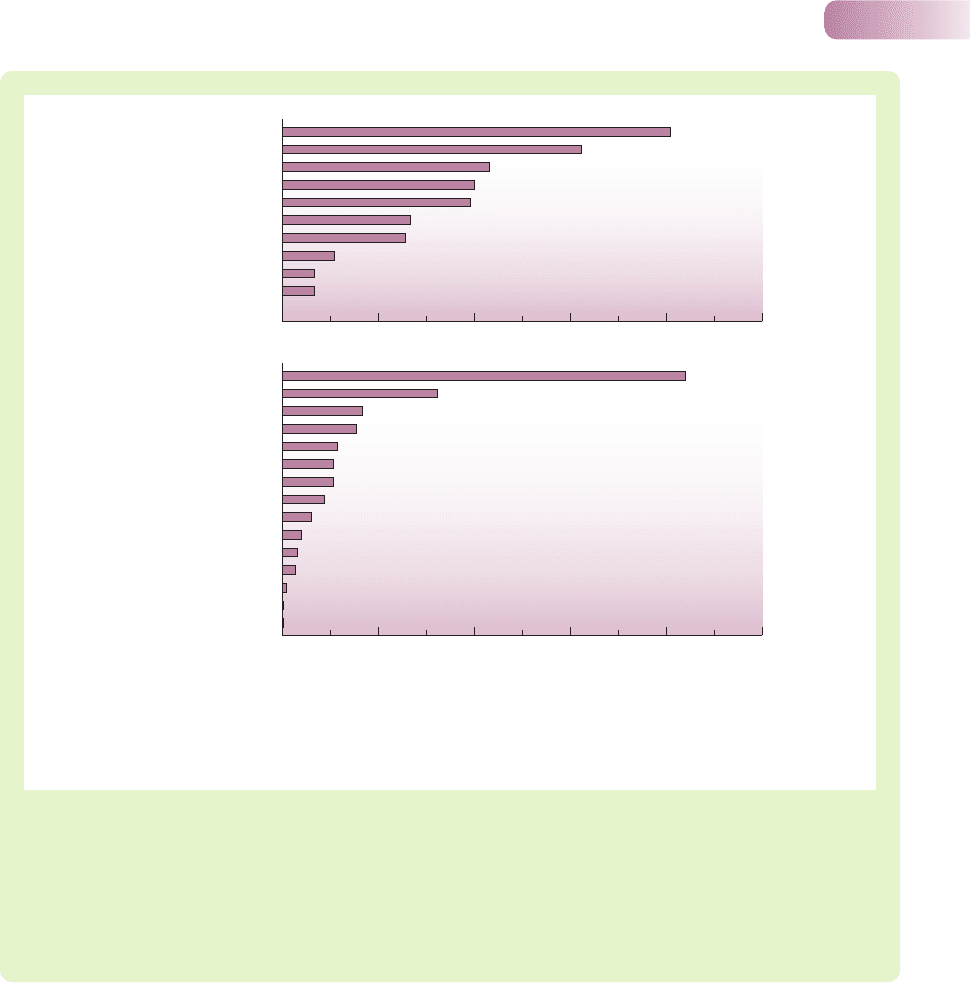

(a) AFTER SHANKAR RAMAN ET AL., 1998; (b) AFTER BROWN & SOUTHWOOD, 1983

Bird species richness per transect

Succession

25

20

15

10

5

Hemipterous insect species richness

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

(b)

04050603010 20

0

(a)

1-year fallow

5-year fallow

10-year fallow

25-year fallow

100-year fallow

Primary forest

Years since abandonment of old field

Total Hemiptera

Homoptera

Heteroptera

Figure 10.20

Examples of increases in animal

species richness during succession.

(a) Bird species richness increased

after shifting cultivation ceased in

tropical rain forest in northeast

India. Areas that were left fallow

after being retired from cultivation

for known periods were compared

with the undisturbed primary forest.

(b) The species richness of true

bugs (insects in the suborders

Homoptera and Heteroptera of the

order Hemiptera) increased with

time after an English farm field

was taken out of cultivation.

the Cambrian explosion:

exploiter-mediated coexistence?

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 349

In contrast, the equally dramatic decline in the number of families of shallow-

water invertebrates at the end of the Permian (Figure 10.21a) could have been a

result of the coalescence of the Earth’s continents to produce the single super-

continent of Pangaea; the joining of continents produced a marked reduction in the

area occupied by shallow seas (which occur around the periphery of continents)

and thus a marked decline in the area of habitat available to shallow-water

invertebrates. Moreover, at this time the world was subject to a prolonged period

of global cooling in which huge quantities of water were locked up in enlarged

polar caps and glaciers, causing a widespread reduction of warm, shallow sea

environments. Thus, a species–area relationship may be invoked to account for

a reduction in taxon richness at this time.

The analysis of fossil remains of vascular land plants (Figure 10.21b) reveals

four distinct evolutionary phases: (i) a Silurian–mid-Devonian proliferation of

early vascular plants; (ii) a subsequent late-Devonian–Carboniferous radiation

of fern-like lineages (pteridophytes); (iii) the appearance of seed plants in the

late Devonian and the adaptive radiation to a gymnosperm-dominated flora; and

(iv) the appearance and rise of flowering plants (angiosperms) in the Cretaceous

and Tertiary. It seems that after initial invasion of the land, made possible by

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

350

Number of familiesNumber of families

Number of families

Number of families

(a) Shallow-water marine invertebrates (b) Vascular land plants (c) Insects

(d) Amphibians (e) Reptiles (f) Mammal-like reptiles and mammals

400

300

200

100

0

40

50

60

30

20

10

0

600 400 200 0

Cam O S D P Tri TertJKCarb

400 200 0

D P Tri TertJKCarb

40

50

60

30

20

10

0

400 200 0

D

P

Tri TertJKCarb

40

50

60

30

20

10

0

400 200 0

D P Tri TertJKCarb

Number of species

400

Number of orders or

major suborders

4

2

0

10

12

8

6

600

200

0

400 200 0

SD PTri TertJKCarb

400 200 0

D P Tri TertJKCarb

Maximum

estimate

Minimum

estimate

A Early vascular plants

B Pteridophytes

C Gymnosperms

D Angiosperms

A

B

C

D

Synapsid

groups

Therian

groups

Geological time (million years before present)

(a) AFTER VALENTINE, 1970; (b) AFTER NIKLAS ET AL., 1983; (c) AFTER STRONG ET AL., 1984; (d–f) AFTER WEBB, 1987

Figure 10.21

Patterns in taxon richness through the fossil record. (a) Families of shallow-water marine invertebrates. (b) Species of vascular land plants in

four groups – early vascular plants, pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms. (c) Orders and major suborders of insects (minimum values

are derived from definite fossil records; the maximum values include ‘possible’ records). (d) Families of amphibians, (e) families of reptiles and

(f) families of ‘mammal-like reptiles’ (Synapsids) and Therian mammals (includes both marsupial and placental groups). Key to geological periods:

Cam, Cambrian; O, Ordovician; S, Silurian; D, Devonian; Carb, Carboniferous; P, Permian; Tri, Triassic; J, Jurassic; K, Cretaceous; Tert, Tertiary.

the Permian decline: a

species–area relationship?

competitive displacement among

the major plant groups?

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 350

the appearance of roots, the diversification of each plant group coincided with

a decline in species numbers of the previously dominant group. In two of the

transitions (early plants to gymnosperms, and gymnosperms to angiosperms), this

pattern may reflect the competitive displacement of older, less specialized taxa

by newer and presumably more specialized taxa.

The first undoubtedly herbivorous insects are known from the Carboniferous.

Thereafter, modern orders appeared steadily (Figure 10.21c) with the Lepidoptera

(butterflies and moths) arriving last on the scene, at the same time as the rise

of the angiosperms. Coevolution between plants and herbivorous insects (see

Section 8.4.3) has almost certainly been, and still is, an important mechanism

driving the increase in richness observed in both land plants and insects through

their evolution.

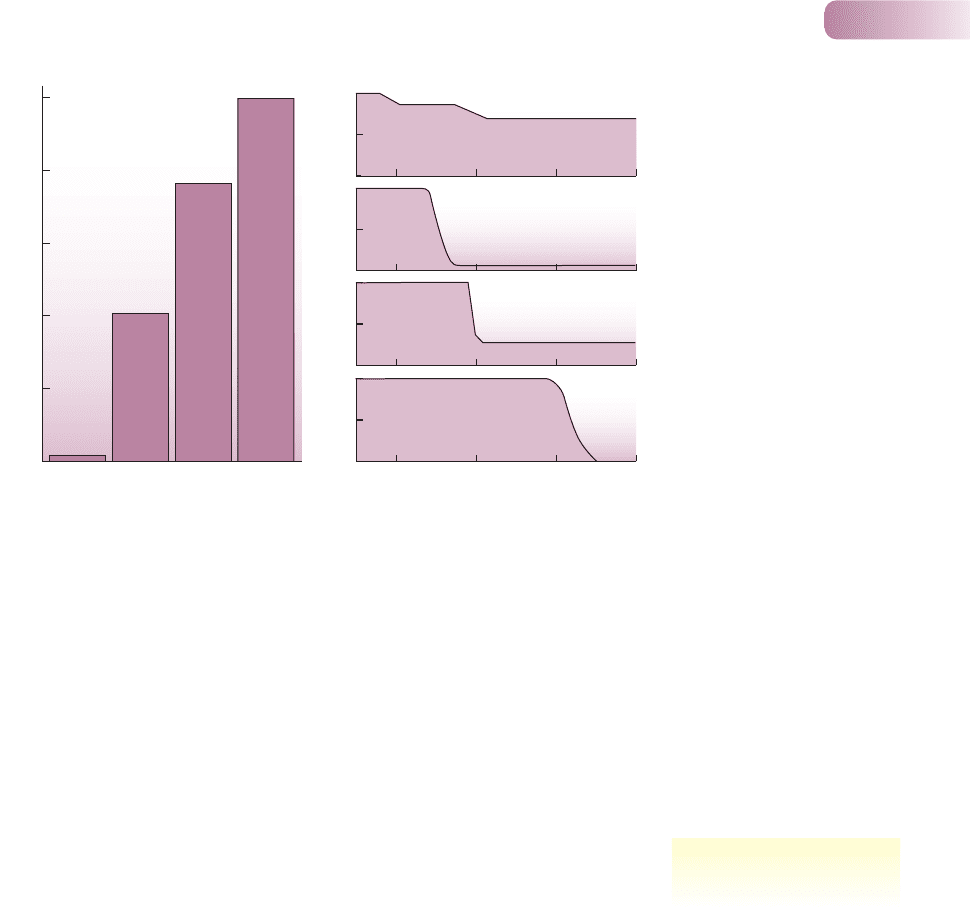

Toward the end of the last ice age, the continents were much richer in large

animals than they are today. For example, Australia was home to many genera

of giant marsupials; North America had its mammoths, giant ground sloths and

more than 70 other genera of large mammals; and New Zealand and Madagascar

were home to giant flightless birds, the moas (Dinornithidae) and elephant

birds (Aepyornithidae), respectively. During the past 30,000 years or so, a major

loss of this biotic diversity has occurred over much of the globe. The extinctions

particularly affected large terrestrial animals (Figure 10.22a), they were more

pronounced in some parts of the world than others, and they occurred at differ-

ent times in different places (Figure 10.22b). The extinctions mirror patterns of

human migration. Thus, the arrival in Australia of ancestral aborigines occurred

between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago; stone spear points became abundant

throughout the United States about 11,500 years ago; and humans have been

in both Madagascar and New Zealand for 1000 years. It can be convincingly

argued, therefore, that the arrival of efficient human hunters led to the rapid

overexploitation of vulnerable and profitable large prey. Africa, where humans

originated, shows much less evidence of loss, perhaps because coevolution of

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

351

(a) AFTER OWEN-SMITH, 1987; (b) AFTER MARTIN, 1984

100

80

60

40

20

0

Generic extinctions (%)

Body mass range (kg)

0.01–5 5–100 100–1000 1000+

1.3

41

76

100

100

50

0

100

50

0

100

50

0

100

50

0

100,000 10,000 1000 100

Survival (%)

Years ago

(a) (b)

Africa

Australia

North America

Madagascar–New Zealand

Figure 10.22

(a) The percentage of genera of large

mammalian herbivores that have

gone extinct in the last 130,000

years is strongly size-dependent

(data from North and South America,

Europe and Australia combined).

(b) Percentage survival of large

animals on three continents and

two large islands (New Zealand and

Madagascar). The dramatic declines

in taxon richness in Australia, North

America and the islands of New

Zealand and Madagascar occurred

at different times in history.

extinctions of large animals in the

Pleistocene: prehistoric overkill?

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 351

large animals alongside early humans provided ample time for them to develop

effective defenses (Owen-Smith, 1987).

The Pleistocene extinctions herald the modern age, in which the influence

upon natural communities of human activities has been increasing dramatically.

10.7 Appraisal of patterns in species

richness

There are many generalizations that can be made about the species richness of

communities. We have seen how richness may peak at intermediate levels of avail-

able environmental energy or of disturbance frequency, and how richness declines

with a reduction in island area or an increase in island remoteness. We find also

that species richness decreases with increasing latitude, and declines or shows a

hump-backed relationship with altitude or depth in the ocean. It increases with an

increase in spatial heterogeneity but may decrease with an increase in temporal

heterogeneity (increased climatic variation). It increases, at least initially, during

the course of succession and with the passage of evolutionary time. However, for

many of these generalizations important exceptions can be found, and for most

of them the current explanations are not entirely adequate.

It also needs to be recognized that global patterns of species richness have been

disrupted in dramatic ways by human activities, such as land-use development,

pollution and the introduction of exotic species (Box 10.4).

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

352

richness patterns –

generalizations and exceptions

10.4 TOPICAL ECONCERNS

10.4 Topical ECOncerns

Throughout the history of the world, species have

invaded new geographic areas, as a result of chance

colonizations (e.g. dispersed to remote areas by

wind or to remote islands on floating debris; see

Section 10.5.1) or during the slow northward spread

of forest trees in the centuries since the last ice age

(see Section 2.5). However, human activities have

increased this historical trickle to a flood, disrupting

global patterns of species richness.

Some human-caused introductions are an accid-

ental consequence of human transport. Other species

have been introduced intentionally, perhaps to bring a

pest under control (see Section 12.5), to produce a new

agricultural product or to provide new recreational

opportunities. Many invaders become part of natural

communities without obvious consequences. But some

have been responsible for driving native species

extinct or changing natural communities in significant

ways (see Section 14.2.3).

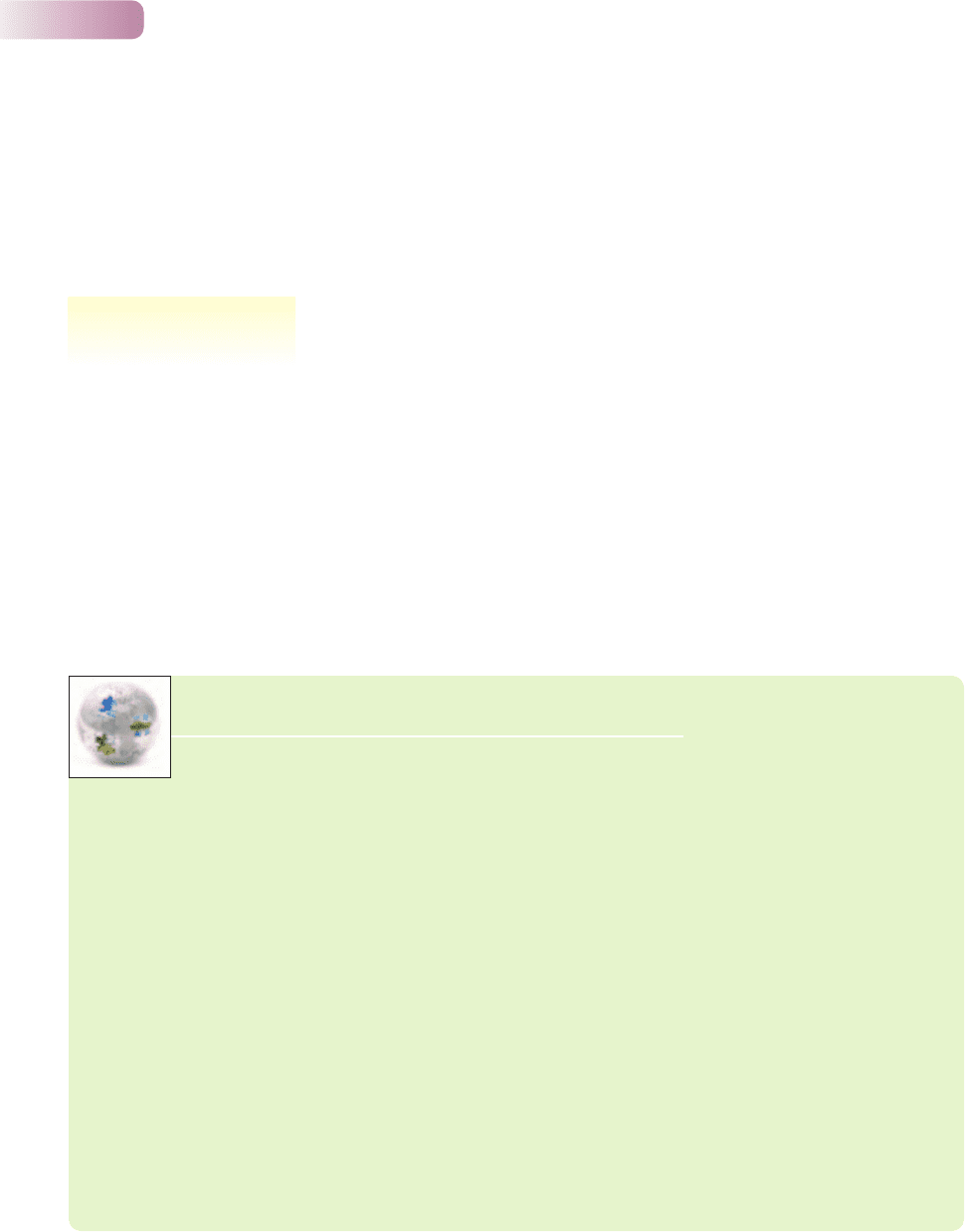

The alien plants of the British Isles illustrate a

number of general points about invaders. Species

inhabiting areas where people live and work are more

likely to be transported to new regions, where they

will tend to be deposited in habitats like those where

they originated. As a result, more alien species are

found in disturbed habitats close to human trans-

port centers (docks, railways, cities) and fewer in

remote mountain areas (Figure 10.23a). Moreover,

more invaders to the British Isles are likely to arrive

from nearby geographic locations (e.g. Europe) or

The flood of exotic species

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 352

Unraveling richness patterns is one of the most difficult and challenging areas

of modern ecology. Clear, unambiguous predictions and tests of ideas are often

very difficult to devise and will require great ingenuity of future generations of

ecologists. Because of the increasing importance of recognizing and conserving

the world’s biological diversity, though, it is crucial that we come to understand

thoroughly these patterns in species richness. We will assess the adverse effects

of human activities, and how they may be remedied, in Chapters 12–14.

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

353

from remote locations whose climate matches that of

Britain (e.g. New Zealand) (Figure 10.23b). Note the

small number of alien plants from tropical environ-

ments; these species usually lack the frost-hardiness

required to survive the British winter.

Europe

Mediterranean

Asia

China

New Zealand

Japan

Australia

Atlantic Islands

India

Hedges and shrub

Arable and gardens

Rocks and walls

Coasts

Streamsides

Marsh and fen

Grass

Heath

Mountains

0 100 200

Number of alien species

300 400 500

0 0.2 0.4

Proportion of alien species in total flora

0.6 0.8 1

(a)

(b)

Waste ground

Woodland

North America

South America

Turkey and Middle East

South Africa

Central America

Tropics

Review the options available to governments to

prevent (or reduce the likelihood) of invasions of

undesirable alien species.

Figure 10.23

The alien flora of the British Isles (a) according to community type (note the large number of aliens in open, disturbed habitats close

to human settlements) and (b) by geographic origin (reflecting proximity, trade and climatic similarity).

AFTER GODFRAY & CRAWLEY, 1998

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 353

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

354

Richness and diversity

The number of species in a community is referred to

as its species richness. Richness, though, ignores the

fact that some species are rare and others common.

Diversity indices are designed to combine species

richness and the evenness of the distribution of indi-

viduals among those species. Attempts to describe a

complex community structure by one single attribute,

such as richness or diversity, can still be criticized

because so much valuable information is lost. A more

complete picture is therefore sometimes provided in a

rank–abundance diagram.

A simple model can help us understand the deter-

minants of species richness. Within it, a community

will contain more species the greater the range of

resources, if the species are more specialized in their

use of resources, if species overlap to a greater extent

in their use of resources, or if the community is more

fully saturated.

Productivity and resource richness

If higher productivity is correlated with a wider range

of available resources, then this is likely to lead to an

increase in species richness, but more of the same

might lead to more individuals per species rather than

more species. In general, though, species richness

often increases with the richness of available resources

and productivity, although in some cases the reverse

has been observed – the paradox of enrichment – and

others have found species richness to be highest at

intermediate levels of productivity.

Predation intensity

Predation can exclude certain prey species and reduce

richness or permit more niche overlap and thus

greater richness (predator-mediated coexistence).

Overall, therefore, there may be a humped relation-

ship between predation intensity and species richness

in a community, with greatest richness at intermediate

intensities.

Spatial heterogeneity

Environments that are more spatially heterogene-

ous often accommodate extra species because they

provide a greater variety of microhabitats, a greater

range of microclimates, more types of places to hide

from predators and so on – the resource spectrum is

increased.

Environmental harshness

Environments dominated by an extreme abiotic factor

– often called harsh environments – are more difficult

to recognize than might be immediately apparent.

Some apparently harsh environments do support

few species, but any overall association has proved

extremely difficult to establish.

Climatic variation

In a predictable, seasonally changing environment,

different species may be suited to conditions at

different times of the year. More species might there-

fore be expected to coexist than in a completely con-

stant environment. On the other hand, opportunities

for specialization (e.g. obligate fruit-eating) exist in a

non-seasonal environment that are not available in a

seasonal environment. Unpredictable climatic varia-

tion (climatic instability) could decrease richness by

denying species the chance to specialize, or increase

richness by preventing competitive exclusion. There

is no established relationship between climatic instab-

ility and species richness.

Disturbance

The intermediate disturbance hypothesis suggests

that very frequent disturbances keep most patches

at an early stage of succession (where there are

few species), but very rare disturbances allow most

patches to become dominated by the best com-

petitors (where there are also few species). Originally

proposed to account for patterns of richness in trop-

ical rain forests and coral reefs, the hypothesis has

SUMMARY

Summary

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 354

Chapter 10 Patterns in species richness

355

occupied a central place in the development of

ecological theory.

Environmental age: evolutionary time

It has often been suggested that communities may

differ in richness because some are closer to equilib-

rium and therefore more saturated than others, and

that the tropics are rich in species in part because the

tropics have existed over long and uninterrupted periods

of evolutionary time. A simplistic contrast between the

unchanging tropics and the disturbed and recovering

temperate regions, however, is untenable.

Habitat area and remoteness: island

biogeography

Islands need not be islands of land in a sea of water.

Lakes are islands in a sea of land; mountaintops are

high-altitude islands in a low-altitude ocean. The

number of species on islands decreases as island

area decreases, in part because larger areas typically

encompass more different types of habitat. However,

MacArthur and Wilson’s equilibrium theory of island

biogeography argues for a separate island effect

based on a balance between immigration and extinc-

tion, and the theory has received much support. In

addition, on isolated islands especially, the rate at

which new species evolve may be comparable to or

even faster than the rate at which they arrive as new

colonists.

Gradients in species richness

Richness increases from the poles to the tropics.

Predation, productivity, climatic variation and the greater

evolutionary age of the tropics have been put forward

as partial explanations.

In terrestrial environments, richness often (but not

always) decreases with altitude. Factors instrumental

in the latitudinal trend are also likely to be important in

this, but so are area and isolation. In aquatic environ-

ments, richness usually decreases with depth for

similar reasons.

In successions, if they run their full course, richness

first increases (because of colonization) but eventu-

ally decreases (because of competition). There may

also be a cascade effect: one process that increases

richness kick-starts a second, which feeds into a third,

and so on.

Patterns in taxon richness in the fossil record

The Cambrian explosion of taxa may have been an

example of exploiter-mediated coexistence. The Permian

decline may reflect a species–area relationship when

the Earth’s continents coalesced into Pangaea. The

changing pattern of plant taxa may reflect the com-

petitive displacement of older, less specialized taxa

by newer, more specialized ones. The extinctions of

many large animals in the Pleistocene may reflect the

hand of human predation and hold lessons for the

present day.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

Review questions

Asterisks indicate challenge questions

1 Explain species richness, diversity index and

rank–abundance diagrams and compare what

each measures.

2 What is the paradox of enrichment, and how

can the paradox be resolved?

3 Explain, with examples, the contrasting effects

that predation can have on species richness.

4* Researchers have reported a variety of

hump-shaped patterns in species richness,

with peaks of richness occurring at intermediate

levels of productivity, predation pressure,

disturbance and depth in the ocean. Review the

evidence and consider whether these patterns

have any underlying mechanisms in common.

5 Why is it so difficult to identify ‘harsh’

environments?

s

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 355

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

356

6 Explain the intermediate disturbance

hypothesis.

7 Islands need not be islands of land in an ocean

of water. Compile a list of other types of habitat

islands over as wide a range of spatial scales

as possible.

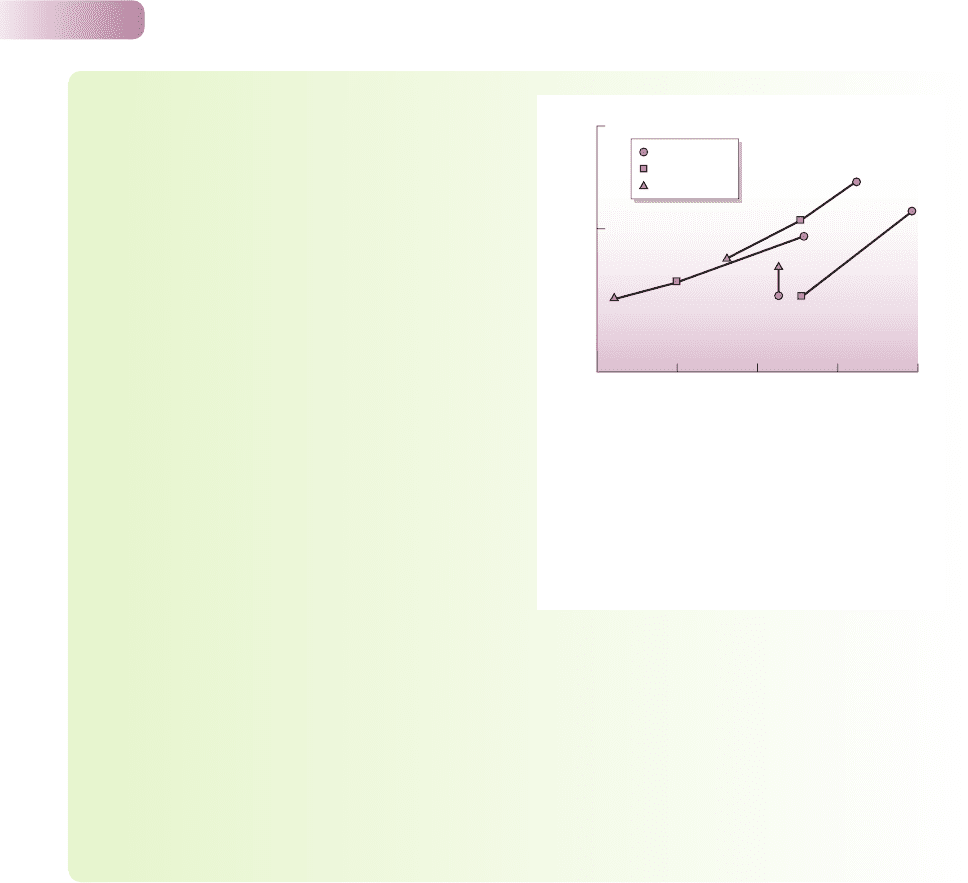

8* An experiment was carried out to try to

separate the effects of habitat diversity and

area on arthropod species richness on some

small mangrove islands in the Bay of Florida.

These consisted of pure stands of the

mangrove species Rhizophora mangle, which

support communities of insects, spiders,

scorpions and isopods. After a preliminary

faunal survey, some islands were reduced

in size by means of a power saw and brute

force! Habitat diversity was not affected, but

arthropod species richness on three islands

nonetheless diminished over a period of

2 years (Figure 10.24). A control island, the size

of which was unchanged, showed a slight

increase in richness over the same period.

Which of the predictions of island biogeography

theory are supported by the results in the

figure? What further data would you require to

test the other predictions? How would you

account for the slight increase in species

richness on the control island?

9* A cascade effect is sometimes proposed

to explain the increase in species richness

during a community succession. How might

a similar cascade concept apply to the

commonly observed gradient of species

richness with latitude?

10 Describe how theories of species richness that

have been derived on ecological time scales

can also be applied to patterns observed in

the fossil record.

s

50

100

75

50

100 225 500 1000

Species richness

Island 3

Island area (m

2

)

Island 1

Island 2

Control

island

1969 census

1970 census

1971 census

Figure 10.24

The effect on the number of arthropod species of artificially

reducing the size of three mangrove islands. Islands 1 and 2

were reduced in size after both the 1969 and 1970 censuses.

Island 3 was reduced only after the 1969 census. The control

island was not reduced, and the change in its species

richness was attributable to random fluctuations.

AFTER SIMBERLOFF, 1976

9781405156585_4_010.qxd 11/5/07 14:58 Page 356

357

Chapter 11

The flux of energy and

matter through ecosystems

CHAPTER CONTENTS

11.1 Introduction

11.2 Primary productivity

11.3 The fate of primary productivity

11.4 The process of decomposition

11.5 The flux of matter through ecosystems

11.6 Global biogeochemical cycles

Chapter contents

KEY CONCEPTS

In this chapter, you will:

l

recognize that communities are intimately linked with the abiotic

environment by fluxes of energy and matter

l

understand that net primary productivity is not evenly spread across

the Earth

l

appreciate that transfer of energy between trophic levels is always

inefficient – secondary productivity by herbivores is approximately

an order of magnitude less than the primary productivity on which

it is based

l

recognize that much more of a community’s energy and matter passes

through the decomposer system than the live consumer system

l

appreciate that decomposition results in complex, energy-rich

molecules being broken down by their consumers (decomposers

and detritivores) into carbon dioxide, water and inorganic nutrients

l

understand that in global geochemical cycles, nutrients are moved

over vast distances by winds in the atmosphere and in the moving

waters of streams and ocean currents

Key concepts

9781405156585_4_011.qxd 11/5/07 15:00 Page 357

11.1 Introduction

All biological entities require matter for their construction and energy for their

activities. This is true not only for individual organisms, but also for the popula-

tions and communities that they form in nature. The intrinsic importance of

fluxes of energy and of matter means that community processes are particularly

strongly linked with the abiotic environment. The term ecosystem is used to

denote the biological community together with the abiotic environment in which

it is set. Thus, ecosystems normally include primary producers, decomposers and

detritivores, a pool of dead organic matter, herbivores, carnivores and parasites

plus the physicochemical environment that provides living conditions and acts

both as a source and a sink for energy and matter. It was Lindeman (1942) who

laid the foundations for ecological energetics, a science with profound implications

both for understanding ecosystem processes and for human food production

(Box 11.1).

In order to examine ecosystem processes, it is important to understand some

key terms.

l

Standing crop. The bodies of the living organisms within a unit area

constitute a standing crop of biomass.

l

Biomass. By biomass we mean the mass of organisms per unit area of ground

(or water) and this is usually expressed in units of energy (e.g. joules per

square meter) or dry organic matter (e.g. tonnes per hectare). In practice

we include in biomass all those parts, living or dead, that are attached to

the living organism. Thus, it is conventional to regard the whole body of a

tree as biomass, despite the fact that most of the wood is dead. Organisms

(or their parts) cease to be regarded as biomass when they die (or are shed)

and become components of dead organic matter.

l

Primary productivity. The primary productivity of a community is the

rate at which biomass is produced per unit area by plants, the primary

producers. It can be expressed either in units of energy (e.g. joules per

square meter per day) or of dry organic matter (e.g. kilograms per hectare

per year).

l

Gross primary productivity. The total fixation of energy by photosynthesis

is referred to as gross primary productivity (GPP). A proportion of this,

however, is respired away by the plant itself and is lost from the community

as respiratory heat (R).

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

358

Like all biological entities, ecological communities require matter for their

construction and energy for their activities. We need to understand the routes by

which matter and energy enter and leave ecosystems, how they are transformed

into plant biomass and how this fuels the rest of the community – bacteria and

fungi, herbivores, detritivores and their consumers.

the standing crop and primary

and secondary productivity

9781405156585_4_011.qxd 11/5/07 15:00 Page 358