Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

146 | chapter three

by constant police surveillance.

81

Some indication of the perceived threat

Arabs posed to the city’s public life can be gleaned from a 1948 portrayal

from the politically conservative newspaper L’Aurore, which along with the

L’Époque reported frequently on the new peril:

North Africans are, in Paris, specialists and record holders of the night-

time attack. More precisely, the Arab is the thief who awaits a late passerby

on the corner of the street, attacks him, and steals his watch. The reality

of the Arabs swarming Paris is that this city is today one of the least safe

in the world between sundown and sunset. Of the 105,000 North Africans

in the Paris region, 80,000 are unemployed. They are lodged in atrocious

boarding houses on the rue de la Charbonnière or in Grenelle with ten

other of their fellow religious. They are tubercular and syphilitic.

82

The presence on the streets and in cafés and bars of groups of Muslim Arab

men provoked a mix of exotic images and dread: “The provincial or tourist

who wanders the streets at certain hours between La Chapelle and the place

Clichy registers a picturesque image in the presence of more and more North

Africans, gathered in groups on the sidewalks of the boulevards or regularly

sitting in the establishments of Montmartre.” And “the streets of Paris seem

to be less safe than the exterior boulevards in 1900!”

83

One reason for this alarmist discourse was that the population of North

Africans in the Seine department had jumped, according to official statis-

tics, from around 45,000 before the war to over 100,000, especially after the

borders were opened to Algerian immigration with the September 20, 1947,

law establishing “continuity” between France and the department of Algeria.

However, including the underground floating population, estimates of the

number of North African immigrants in the city and suburbs were much

higher by the mid-1950s. They were the ultimate outsiders, excluded from the

public sphere and the spaces of public life, perceived only as a menace. The

vast majority were Algerian men, with a much smaller number of Tunisians

and Moroccans—all looking for work in the city’s industries. The newcom-

ers arrived in the capital with high hopes but often completely without re-

sources, falling rapidly into the worst of conditions. A study by the Institut

national d’études démographiques (INED) estimated that some 60,000

North Africans—60 percent of their official numbers in Paris—remained

unemployed.

84

Those who did find work most often labored in heavy industry

public space and confrontation | 147

and in construction, where their jobs were low paid, temporary, and seasonal.

Jean-Pierre Chabrol’s 1953 “Paris Stories” series for L’Humanité explores

the obscure, clandestine places of these undesirables. Chabrol arrives in the

2nd arrondissement on the rue Grénéta near Réamur-Sébastopol, where he

describes the “despicable lairs, for the price of gold, where a third of Alge-

rian workers attempt to live with their families. We already know about the

shameful boxes, without windows, without furniture or beds, constructed for

them like cages under cramped stairways, and for which they pay three to six

thousand francs a month.” The Sunday of his visit, the water in the building

is turned off and the poor renters are left to beg for water in the streets.

85

The Algerian War (1954–62) massively increased the number of exiles and

added large numbers of women and children who were escaping the crisis.

By the late 1950s official estimates put the number of cheap rooming houses,

cafés, bars, and assorted establishments exclusively serving the North African

population in Paris at well over two thousand.

86

The settlers were mainly clustered in the fleabag hotels, boarding houses,

hostels, and streets of La Chapelle and La Gotte d’Or in the 18th arrondisse-

ment, around La Villette in the 19th and 20th arrondissements, and around

the cité Jeanne d’Arc in the 13th arrondissement. Thousands found work and

lodging in the inner ring of northern suburbs at Clichy, Levallois, Gennevil-

liers, Aubervilliers, and Saint-Denis. As early as in 1945, the geographer Jean

Gravier (who would make his career cataloguing the dreadful conditions in

Paris) described the tenements in places such as Saint-Denis as “a sordid

concentration camp for immigrants.”

87

West of Paris they gathered in the

slums of Puteaux and Nanterre and around Boulogne-Billancourt. They

moved outward from the 13th arrondissement into the suburbs of Vitry

and Choisy-le-Roi. Although the inhabitants appeared to be nomadic, their

migration generally followed a traditional pattern. Immigrant settler com-

munities acted as a buffer. Newcomers sought out contacts from their old

neighborhoods in Algeria who might provide lodging, aid in finding work,

and a communauté de douar (village community). The state’s Service des af-

faires musulmanes, the Seine prefecture, and the prefecture of police issued

a series of official reports aimed at surveying and controlling disruptive im-

migrant populations. Identifying their place of origin and religion was the

framework for the construction of discrete social and ethnic characteristics.

For example, according to the “Étude de la population nord-africaine à Paris

et dans le département de la Seine,”

88

completed by the prefecture of police

148 | chapter three

in 1955, nearly all of the four thousand Algerians in the northern district of

La Villette were Kabyles from the capital city of Algiers and neighboring

Tizi-Ouzou. They found work in the Lebaudy and François refineries or

in La Villette’s foundries and metallurgical works. They congregated in the

some 150 Algerian bars, cafés, and markets in the neighborhood, establish-

ments never frequented by the local working-class population. The report’s

findings thus reinforced the boundary between native Parisians and the new

immigrants. In both La Goutte d’Or on the Right Bank (home to nearly

four thousand North Africans) and the slums of the 13th arrondissement on

the Left Bank (another three thousand), immigrants were mainly from the

cities of Tizi-Ouzou and from Bougie (Béjaïa). In the 13th arrondissement,

they gathered in the cafés on the rue Nationale and the rue du Château-

des-Rentiers. In the suburbs, the situation was much worse. Police estimated

that some four thousand migrants in Gennevelliers were crowded into sordid

shelters, shacks, and cellars, much of which was clandestine. The bidonville

of La Plaine in Nanterre was infamous. There, over eight thousand North

Africans found refuge in assorted claptrap housing, blockhouses, and squat-

ter camps on rotting wastelands. Sanitary conditions were abominable. In-

deed, the term bidonville itself was first used in the 1950s during the French

protectorate in Morocco to describe poor neighborhoods where the roofs of

makeshift housing were cut out of metallic fuel containers or bidons. It then

came into general use to depict indigènes algériens who were blamed for the

physical decline of metropolitan areas. In the series “Capitals of Suffering”

(1957), the L’Humanité reporter Raymond Lavigne descended into the abyss

of the Nanterre bidonville to find life stories of utter misery and unremit-

ting danger. Djemila’s broken-down wooden hut went up in flames with his

wife and children inside. They were saved, only to find themselves living in

a condemned basement so humid the children were sent to a sanatorium,

while his wife awaited the birth of a fifth child. The interviews are a litany of

sorrows.

89

Early on, the prefect Roger Verlomme acknowledged the growing hu-

manitarian crisis in Paris and outlined the government’s efforts to alleviate

it. Public shelters or foyers reserved for North Africans were opened in Bati-

gnolles and Malesherbes in the 17th arrondissement, in Gennevilliers, and

in Nanterre. By the mid-1950s there were five in Paris and thirty-four in the

suburbs. A North African dispensary was created at the Franco-Musulman

Hospital in Bobigny. Soup kitchens were pressed into service. But whether

public space and confrontation | 149

it was a question of public aid or the reality of their social marginalization,

what characterized the condition of North African immigrants was spatial

segregation. They remained in their own wards, their own bars and cafés,

strictly divided from the normal life of the neighborhood they inhabited. In

the long, passionate public debate over housing conditions in Paris, only

rarely were North African immigrants included among the dispossessed.

In what was essentially an extension of the colonial regime, North African

immigrants labored to reconstruct France without taking any part in the

country’s life. In Les Deux bouts, the novelist Henri Calet visits an Algerian

construction worker named Ahmed Brahimi, a veteran of Leclerc’s famous

2nd French Armored Division who took part in the 1944 Normandy landing.

Calet follows him on his daily commute to the chic district around the place

de l’Étoile, where he labors on a construction project for luxury apartments

costing over two million francs each. “What is curious about Ahmed,” Calet

dryly remarks, “is that although he builds houses with his own hands, he has

been more or less homeless since he came to France.” For two months after

his arrival in Paris in 1952, Ahmed passed his nights going from one bistro

to another, and then wandered the streets until work started in the morning.

Since “nearly all the hotel owners refuse to rent to Muslims . . . even if they

are well dressed,” he finally found one room to share with ten other Algerian

immigrants.

90

Government reports accounted for these conditions by explaining that

Algerians were generally from rural villages and little prepared for life in the

modern spaces of the capital, a convenient fiction (despite the data showing

that most were from Algiers, Tizi-Ouzou, and Bougie) that hid the underly-

ing official strategy of racial containment and exclusion. According to the

1955 police report, the influence of Islam furthered the chasm, as did the

dense living circumstances of the immigrant population: “It appears almost

impossible for the moment to imagine the assimilation of North Africans into

a purely secular [laïque] society.”

91

In a continuation of fears about hygiene

and contagion in the bidonvilles, North Africans were believed to carry deadly

diseases, especially tuberculosis. They remained excluded in Paris, speaking

Arabic, wearing traditional clothing, retaining Islamic cultural practices and

their own sense of the public sphere. The most important public gathering

places for Algerians were the neighborhoods of La Chapelle and La Goutte

d’Or, especially the triangle formed by the rue de la Charbonnière, the rue de

Chartres and the boulevard de la Chapelle. This was the heart of the “Pari-

150 | chapter three

sian Medina,” the Trois Chats, as they were known. It was dominated by the

open-air Charbonnière market, by the network of Arab bars and cafés, and

the social life of the street. In his Paris insolite, Jean-Paul Clébert described

the atmosphere in 1952:

You know you are entering the Arab bistros of La Goutte d’Or and La

Chapelle by the odor of kef. The men sit silently smoking on benches

along walls of cracking plaster, steadily sipping water or tea in between

their cigarettes, not even bothering to crumble their pastille or crush the

tobacco in their pockets that they roll by pinching, and then put care-

fully on the table, spreading it out on three pieces of Job Noir cigarette

paper.

92

The “oriental market, a sort of souk,” as it was referred to in the press,

93

attracted thousands of North Africans from throughout the metropolitan

region, especially on weekends, drawn by its informal economy of cheap

clothing, food, and wares. It was an illicit space, one of the centers of the

black-market trade, with everything from American military stockpiles to

goods stolen throughout the region to drug traffickers. For years after the

war, the market was tacitly ignored by the authorities. Around it were as-

sembled some 72 cheap hotels and 127 cafés, most of them run by immigrants

from Tizi-Ouzou and Bougie and serving the local immigrant population.

The hotel-café was the public arena of ethnic life and sociability as well as

an expression of cultural heritage. Much as in nineteenth-century Paris, it

acted as a transformative, mnemonic site: a passage between private and

public life, between the collective practices of the village and the modern

city. With their phonograph music, singing, and dancing, the Arab cafés of

the rue Nationale, for example, “had the allure of guinguettes,” according to

Jean-Paul Clébert.

94

Young men spilled out into the streets around their fa-

vorite haunts in an expanding circle of public sociability. Sundays were the

only times immigrant workers had to venture out from work into the city.

Like other Parisians, they strolled the boulevards, met in cafés, and went to

soccer matches, bicycle races, and films, especially Egyptian films near the

gare de l’Est. As North Africans came increasingly to dominate neighbor-

hood public life in places such as La Goutte d’Or, the former residents fled

the area. The animosity between North African and Parisians was mutual.

In what the 1955 police surveillance report referred to as a “vicious circle,”

public space and confrontation | 151

their presence on the landscape provoked fear and anxiety—to which their

reaction was defiance and further isolation.

95

All North Africans (including Moroccans and Tunisians) were considered

guilty by association and were under constant suspicion of terrorism and

collusion with the revolutionary Front de libération nationale (FLN). Police

surveillance, raids, and roundups were the norm given the overt intolerance

and bigotry spurred on by daily newspapers and xenophobic fears of criminal-

ity and foreignness. The Service des affaires indigènes nord-africaines on the

rue Lecomte scrutinized every aspect of North African life in the capital. The

function of certain spaces in the metropolis is to isolate and make invisible.

La Goutte d’Or became this kind of acknowledged heterotopic territory. The

paramilitary attack against it was a mark of the deepening crisis of decoloniza-

tion. In December 1947 police agents, accompanied by journalists, staged a

grande rafle (raid) at La Goutte d’Or, surrounding the neighborhood and tak-

ing into custody some one hundred individuals who were carted off to police

headquarters on the quai des Orfèvres. The roundups of suspicious Algerians

continued through the winter.

96

The 1955 police report acknowledged 4,405

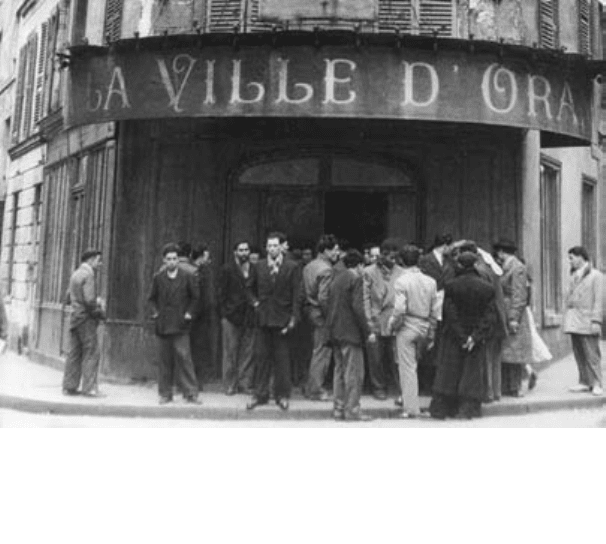

figure 15. North Africans gathered in front of La Ville d’Oran Hotel, where furnished

rooms were rented to immigrants, April 1950. © keystone-france.

152 | chapter three

Algerians arrested in 1952, then 5,143 arrested in 1953, and 5,471 arrested in

1954. The increase signaled the worsening of relations. Algerians constituted

25 percent of those arrested for murder, 35 percent of those apprehended for

violent behavior, 54 percent of those arrested for violent theft, 54 percent of

those arrested for armed robbery in public, 52 percent of those arrested for

shooting, and 60 percent of those arrested for carrying weapons.

97

In early

August 1955 the Fête de l’Aïd El Kébir brought another round of violence

at La Goutte d’Or. Here the volatile character of la fête was stripped of sen-

timent and interpreted instead as an assault, an attack against the French

nation itself by fanatic mobs. Police intervention in the market on the rue

de la Charbonnière was met with attacks by some 1,500 to 2,000 protestors.

Hundreds of young Algerians rampaged through the neighborhood, attacking

passersby, damaging stores, and throwing bricks at automobiles. Police and

the Paris prefecture retaliated by permanently closing down the infamous

black-market bazaar and cordoning off the neighborhood to all but locals

with identity papers for the next week.

The escalating crisis in Algeria made the sense of the imminent threat

North African immigrants posed to the city’s public domain explosive. The

mounting calls for Algerian independence or separatism were treated as

despicable treachery. The traditional Algerian People’s Party was outlawed.

To take its place, Messali Hadj’s radical Mouvement pour le triomphe des

libertés démocratiques (movement for the victory of democratic freedoms,

or MTLD) opened its headquarters on the boulevard Saint-Michel. As the

Algerian nationalist movement began to appropriate the capital’s symbolic

sites of protest, the state’s repressive apparatus was intensified. The appear-

ance of Arab and Muslim delegations at the United Nations in Paris in 1951

was the occasion for a general prohibition of any North African political

activity. The rally planned at Vél’ d’Hiv turned into what the newspaper

Franc-tireur termed a “police roundup reminiscent of the sad measures of

Chiappe-Tardieu-Laval.” Squads of police and CRS units raged through the

area, setting up roadblocks around Vél’ d’Hiv. Thousands were hunted down

and arrested.

98

An illegal rally in the Salle Wagram led to a thousand arrests

and violent confrontations with police on the place des Ternes. Increasingly

politicized, Algerians protested against the prohibition of the newspaper

Algérie libre at the headquarters of the Société nationale des entreprises de

presse (SNEP) on the rue Réaumur the same year. In what had become a

too-frequent finale, the protest ended in violent confrontation with police

public space and confrontation | 153

that left wounded on both sides, and then more arrests. The MTLD and its

supporters attempted to claim the symbolic space of the Champs-Élysées

for a march in support of their leader, Messali Hadj, in May 1952. A political

demonstration at Vél’ d’Hiv in December of that year led to a second police

raid in the area that ended with violent confrontations and three thousand

taken into custody.

99

Algerian delegations also took part with increasing regularity in the tra-

ditional May Day and July 14 processions from the place de la Nation to

the Bastille, usually under the protective wing of the Communist Party. In

general Algerian immigrants during the period 1945–54 were seen as laborers

necessary for reconstruction. Although the communists maintained a discreet

distance from MTLD-organized protests, nonetheless Algerians were treated

with respect as workers. Their political groups were welcomed at the time-

honored public pageants, but they marched separately from the main contin-

gent and always under police surveillance. The traditional commemoration

of February 1934 from the Bastille to the place de la Nation in 1951 brought

some twenty thousand people into the streets. But the most notable feature

in this working-class spectacle was some six thousand Algerians marching

under the banner of the MTLD. During the May Day march the same year,

the appearance of separatist MTLD flags led to riots on the rue Ledru-Rollin.

Hundreds were arrested and sixty-eight wounded. Ironically, the police had

attempted to prevent trouble by arresting in advance some 1,600 Algerians

who were coming into Paris from the suburbs. The huge protests against the

arrival of the American General Ridgway in May 1952 brought Algerians

along with the PCF out into the streets in record numbers. The one death

reported during the riots and skirmishes with police was that of an Algerian

on the place Stalingrad.

By far the most violent and deadliest incident took place during the fête

nationale celebration on July 14, 1953. Although the march from the Bastille

to the place de la Nation was the traditional opportunity for the PCF to

flex its political muscle, the throngs on parade through the working-class

stronghold were part of a popular fête and were tolerated if they followed

the time-honored pattern approved by the police. It was a political festival,

with workers marching behind union and factory banners along with floats,

folkloric groups, and marching bands. What sparked confrontation was in

part the changing economic atmosphere. By the mid-1950s, reconstruction

was winding down. Employment opportunities in the Paris region began

154 | chapter three

to dry up even though industrial productivity remained high. Competition

for jobs, especially those taken by North African immigrants, sharpened

racism. Always precarious, jobs for the marginalized Algerian community

dropped precipitously, especially during the winter months, and became

an increasing source of discontent.

100

This combination of economic pres-

sures and the growing crisis of the Algerian War effectively split North Afri-

can “undesirables” off psychologically and politically even further from any

pool of working-class solidarity. Tensions between nationalist paratroopers

and Algerians had already put previous marches on edge, with insults flying

on both sides. Impassioned by their own crusade for freedom, the Algerian

contingents were increasingly segregated from the main processions. Where

they had once been welcomed as comrades, North Africans were now eyed

with bitterness and suspicion in the fading ouvriériste imaginary.

In pouring rain, the march passed before the reviewing stands, where

stood Marcel Cachin (a deputy and municipal councilor from La Goutte

d’Or), Jacques Duclos, and Communist Party notables, and then began to

disperse under the watchful eyes of law enforcement. But the contingent of

Algerians, five thousand to six thousand strong, continued to rally for the

MTLD under the Trône column, demanding freedom for Messali Hadj and

chanting for Algerian independence and an end to colonialism. When police

rushed in to break up the gathering, the inevitable violence broke out. It went

on for nearly an hour. Bistros on the place de la Nation were ransacked, and

police cars were set ablaze; Cachin and Duclos were rushed away from the

bloody scene. Police and CRS forces charged the rioters. The melee ended

in seven dead (six Algerians and one French) and some one hundred people

wounded, many of whom were police. Crowds milled around the disaster;

according to Le Parisien libéré, “a woman sat dumbstruck on the bandstand

where the orchestra was set to play for the July 14 ball, next to the piano,

which was miraculously untouched.”

101

The tragedy was a turning point for

the capital. The outpouring of shock and emotion reverberated through the

neighborhoods as people descended into the streets. With demonstrations

banned, the protests took a variety of alternative forms: localized corteges

against police brutality, the gathering of signatures for letters of protest, pub-

lic moments of silence. Makeshift memorial plaques with the names of the

victims, who had died “for liberty,” appeared spontaneously on the streets

once more as people reached into the immediate past of the Liberation for

commemorative practices. On June 21 a massive meeting was organized by

public space and confrontation | 155

the Communist Party at the Cirque d’Hiver in the 11th arrondissement to

demonstrate the city’s “anger against those responsible for this reactionary

and racist crime at the place de la Nation.” The PCF called for work stoppages

throughout the city’s industries. Thousands waited in line to view the bod-

ies at the Grand Mosque on the Left Bank, and more than twenty thousand

people marched from the Maison des Métallos to Père Lachaise Cemetery

for the burial services.

102

But the events only ended with more repression.

Arrests continued. The prefect of police, Maurice Papon, resuscitated the old

Brigade nord-africaine, a police unit specializing in the repression of North

African activities and rechristened it the Brigade des aggressions et violences

(BAV). The new name sardonically laid out the outfit’s mission. The public

spaces of the city were entered into the topography of colonial war. Paris was

well on its way to Charonne.

As Algeria exploded, so did the streets of the capital. The war and struggle

for independence in 1955 and 1956 provoked immediate reaction. Algerian

workers demonstrated in La Goutte d’Or against the state of emergency

declared in Algeria in July 1955. Bands of young men, joined by students,

headed for the main railroad stations, where they staged protests by blocking

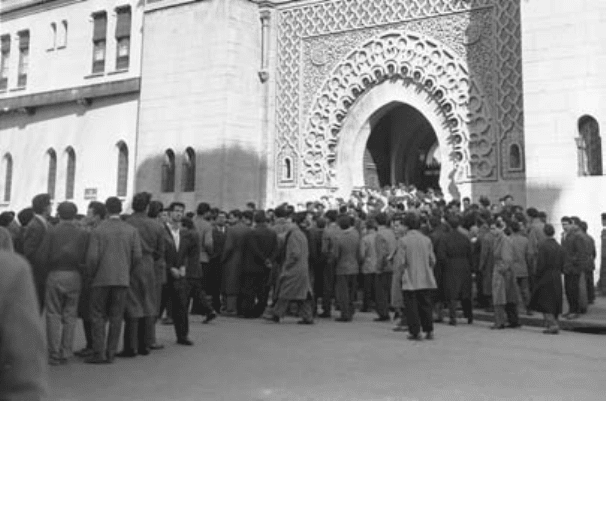

figure 16. The crowd of North Africans gathering in front of the Grand Mosque on March

9, 1956. © bettmann/corbis.