Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

136 | chapter three

Eugène Claudius-Petit’s caustic remark that “‘France is not a milk cow with

an inexhaustible udder.’ In other words,” he translated, “if you want a place

to live, count on yourselves.” If France could not solve its housing problem,

it would lead to catastrophe. Collin needled the Seine prefecture to study

the low-cost housing projects being completed by communist municipalities

at Aubervilliers and Argenteuil.

64

The housing crisis was exploited very successfully by the PCF, especially

after the party’s expulsion from government in 1947 and return to opposition.

In 1951 the raconteur and novelist Jean-Pierre Chabrol began a series for

L’Humanité entitled “Paris Stories” that mounted to a flânerie by taxi through

the city to explore the social landscape. It employed the humanist, life-story

technique typical of the counternarrative to state rationalist discourse. In

one episode, the archetypal Parisian concierge leads the reader into a poor

neighborhood in the city’s northern outskirts: “There are neighborhoods in

Paris where the silence must thwart the sleep of Monsieur Claudius-Petit,

that minister of ruins and grand constructor of amerilôques chateaux.” Con-

cierge Madame Douillard is listening to the entreaties of a man at the door

asking for a place to live:

He says his prayers but knows he hasn’t a chance; “. . . even a small

room? An attic? An old office even, I’ll take anything.” He stops himself

from yelling, “I’m not a beggar. I work hard, honestly. I have a wife and

children. . . .” “You are the tenth one since the beginning of the week,”

Madame Douillard answers his pleas.

But she knows how hard life is in this poor neighborhood;

she senses it around her . . . the growing anger against the rising costs, the

misery, the preparation for war. She has already collected one hundred

and twenty signatures in the little notebook she has been given in the

petition drive for the Pact of Five. It’s already full! “Even if people say

that the ministers have invited Adenauer, the head of the Nazis, to Paris,

only a few years after the Liberation. It’s not possible!”

65

Throughout the winter months of 1953, L’Humanité featured an ongoing series

of articles on housing and slum conditions in Paris. Interviews with families

barely surviving in sordid hovels were followed by scathing criticism of the

public space and confrontation | 137

Seine prefecture. The housing crisis was blamed on the Americans and the

cold war, which siphoned off funds needed to build homes. In the miserably

cold winter of January 1953, a group of shanties illegally sitting on land over

an ancient mushroom cavern in Nanterre disappeared into a black abyss of

vapors. When asked why they were living there, the inhabitants responded,

“We knew it was risky, but at least it was a roof over our heads!” “US Go

Home!” the article ended; “We want to build for the French, not for the oc-

cupiers! More money for houses, not for guns.”

66

In retaliation against the PCF’s withering criticism, the prefect of the

Seine defended the government’s record by arguing that the housing crisis

could be solved if monies didn’t have to be poured into the French defense

budget to counteract international communism. The crisis was brought on

by people’s refusal to spend more of their salary on where they lived. It was

caused by strikes in the construction industry and by architects.

67

Respond-

ing to the government’s cold-war campaign warning against a “French Soviet

republic,” the well-known socialist mayor of Sceaux, Édouard Depreux, wrote

in the newspaper L’Avenir de la banlieue de Paris that

these anticommunist advertising slogans have little influence on families

living in cellars, attics, slums, on young families waiting in vain for six or

seven years for housing, on dozens of thousands of workers condemned

to a mediocre standard of living. Freedom, in the name of which they

should mobilize against dictatorship and totalitarianism . . . has little

meaning to them. To be free requires having a minimum of well-being

and comfort.

68

As evidence of the mounting public pressure, in 1953 the MRU officially

changed its name to the Ministère de la reconstruction et du logement (min-

istry of reconstruction and housing, or MRL). Yet little changed beyond the

symbolic. Writing in an article entitled “Our Houses and Our Cities” in a

special issue of Esprit, the sociologist Paul-Henry Chombart de Lauwe re-

proached this

‘‘happy country,” France, which displays the splendors of Paris for tour-

ists. . . . But leprous neighborhoods, stinking alleyways, and shantytowns

are judiciously hidden away because of the taboo about housing. Hun-

dreds of thousands of families live in hell in cheap hotel rooms, in sheet-

138 | chapter three

metal huts, in one-room hovels. And at the same time, there are men of

goodwill, truly sincere, who say that the problem of housing is not that

bad, that it will pass in two or three years.

69

Public outrage over the tragic plight of the homeless in Paris was finally

galvanized by what one author has called Abbé Pierre’s agitprop campaign.

70

The Catholic priest Henri de Grouès, known by his Resistance pseudonym

Abbé Pierre, worked among the vagrants and squatters in the notorious zone

surrounding the city. Grouès joined the Resistance and eventually worked

for the legendary Vercors maquis. Captured and imprisoned by the enemy,

he escaped, crossed the Pyrenees into Spain, and finally reached Algiers. In

1946 he was elected to the National Assembly on the Christian Democratic

Mouvement républicain populaire (MRP) ticket and adroitly used his political

connections to fund his community projects. His Emmaüs self-help com-

munity grew from the youth hostel he established in 1947 in an old house in

Neuilly-Plaisance, in the suburbs east of Paris. Its “pilgrims” quickly shifted

from weekend and overnight backpackers to homeless vagrants and families

desperate for shelter. The roots of Emmaüs lay in the notions of Christian

humanism and social welfare in which much of centrist political ideology

was absorbed at the war’s end. By 1954 more than a hundred families lived

at Emmaüs in a series of self-constructed apartments and dwellings made

from prefabricated lumber frames set on cement foundations with tin roofs.

They were paid for with the meager proceeds derived from ragpicking and

recycling programs organized on a community-wide basis. The Emmaüs

community was built illegally, without the required MRU construction per-

mits, dependent for protection on Abbé Pierre’s celebrity and influence.

71

Offshoots of Emmaüs were established at suburban Neuilly-sur-Marne, at

Pontault-Combault, and at Plessis-Trévise. The workers in and around his

colonies were invariably communists or sympathizers who participated in

such rituals as the Fête de l’Humanité and the annual May Day procession

from the place de la Bastille to the place de la République. To display his

solidarity with them, Abbé Pierre himself regularly appeared in the parades

and also took part in demonstrations denouncing the Marshall Plan, NATO,

and Coca-Cola.

In what became a foundational allegory for the housing movement, during

the night of January 6–7, 1954, just after the French Chamber of Deputies

had refused to allocate funds for emergency shelters for the poor, a baby died

public space and confrontation | 139

of cold in the abandoned shell of a city bus that served as his family’s home

in Neuilly-Plaisance. The commercial media was instrumental in exposing

this tale of the excluded, which normally would have gone unseen and un-

noticed. It is an account of human misfortune meant to be emotional in

content. The incident was not an anomaly. Seventeen Parisians were found

frozen to death in one frigid night that winter. Then, in early February 1954,

the worst cold wave in memory struck the city. Over the course of a week,

the severe weather claimed the lives of some one hundred Parisians, among

them infants and elderly trapped in ramshackle unheated tenements. In an-

other emblematic account, the police found a woman sprawled dead on the

boulevard de Sébastopol, an eviction notice from her landlord clutched in her

fist. The morgue was crammed with the frozen bodies of homeless clochards,

and the hospitals were filled with the sick and shivering.

Incensed by the tragedies, Abbé Pierre launched a public campaign on

behalf of the homeless and poor. He wrote an open letter to the minister of

construction and housing, Maurice Lemaire, inviting him to the funeral of

the poor dead infant who came to symbolize the human tragedy of the hous-

ing crisis. He wrote to Le Figaro and on February 1 appealed to Parisians,

via a broadcast on Radio Luxembourg, to assemble each night at the place

du Panthéon in a great rescue campaign.

72

Thousands of people in their

automobiles showed up ready to hunt the city for the homeless freezing on

the streets. Abbé Pierre demanded the opening of shelters and funding for

emergency housing. The radio, daily newspapers, and magazines took up his

call with nonstop features on the housing problem, the human drama of the

slums, and the misery of the homeless. Les Actualités françaises featured “A

Night with Abbé Pierre” in local movie theaters. The visual narrative begins

with images of bitter cold and the frozen Seine, with homeless families ly-

ing in the streets and sitting over grates for heat. The scenes are followed by

shots of Abbé Pierre visiting the destitute and of his claptrap cité d’urgence,

made up of sheds, old trailers, and pieced-together huts. The last sequence is

almost pure social sponsorship, with Abbé Pierre at the Panthéon asking for

help and people answering his call, contributing blankets and clothing.

73

A tireless promoter, Abbé Pierre spoke from church pulpits, in the streets

and bistros, over the radio, during theater intermissions, even in nightclubs.

He wangled a spot on the radio quiz show Double or Nothing, breezed through

a series of questions on international affairs, and won 300,000 francs. He

climbed the stage at the Gaumont Palace and, with a spotlight silhouetting

140 | chapter three

his profile against the white screen, confronted an audience of thousands

waiting to hear his appeal. The images of Abbé Pierre and his self-help com-

munity electrified public opinion. Through the mass media and through

television broadcasts and films produced about Abbé Pierre beginning in

1954 and continuing for some years after, the public essentially consumed

what Roland Barthes called a bright display of Christian charity. It collectively

gazed “at the shop-window of saintliness” and responded to the ideal of good

works.

74

Abbé Pierre’s radio broadcasts from Neuilly-Plaisance initiated an

“insurrection of kindness” that drew reporters from newspapers and national

magazines such as Paris Match and Elle intent on doing photo spreads on

the community of ragpickers who had pricked the national conscience. In

February 1954 Paris Match published exposés that included Grouès’s life

story and a panoply of photographs on homelessness and his good works in

the capital. Many of them displayed families finally finding a roof over their

heads: “Having become in one night Star no. 1 of film, radio, music hall and

television, this shock-priest leads his monstrous parade with the faith and

marvelous candor of Saint Francis.”

75

The grotesque images of the dispos-

sessed exposed the contradictions of the trente glorieuses, placed the housing

crisis front and center on the public stage, and succeeded in completely

subverting official discourse.

The French responded to all these mediatized entreaties with unprec-

edented compassion and generosity. The plight of the homeless exploded

into broad daylight, and public opinion was mobilized. Within two weeks of

his call of February 1 on Radio Luxembourg, more than one billion francs

poured into Abbé Pierre’s coffers. Local aid committees were organized.

The Hotel Rochester on the tony rue de la Boétie near the Champs-Élysées

offered space for a drop-off center for blankets and coats. The area was

jammed with people bringing donations. A tent was set up on the rue de la

Montagne Saint-Geneviève for collecting and distributing sleeping bags to

the dispossessed. Money, clothes, hotel rooms, and office and storage space

were donated. Marches and mass meetings were staged. The press was flooded

with reports on the appalling state of French housing. Le Monde related the

details of the suicide of a young mother who killed herself so that her family

would have more room in their thirty-square-foot hovel.

76

Caught up in the

campaign, Métro supervisors converted three unused stations into a dor-

mitory for the destitute, while the French railways reopened a closed wing

of the gare d’Orsay as a storage depot for donated supplies. Neighborhood

public space and confrontation | 141

city halls were opened to welcome the homeless at night. Day after day the

popular press showcased feature articles on the community outpouring.

The result of all this media coverage was the emergence of the margin-

alized and homeless from the hidden recesses, the otherness, of the city’s

spaces. Invisibility was replaced by a moving forward onto the public stage

in a spectacle of poverty. Press depictions of the compagnons eking out an

existence at Emmaüs followed the poetic, sentimental images of the working

poor taking up responsibility for their condition and sharing the burden of

reconstruction. The illumination of the destitute made clear that they were

neither drunks nor vagrants, but good French working families—the virtu-

ous poor. Their moral fiber was upright, and they were capable of a transfor-

mative posture, of affecting the construction of the urban realm. The short

1954 promotional film on Abbé Pierre and Emmaüs focused on the power of

celebrity and its political entitlement, with politicians and housing officials

trekking out to Neuilly-Plaisance in deference to the self-help colony, where

figure 12. Demonstrators gather in front of the Hôtel de Ville to march in support of

Abbé Pierre’s housing campaign. Photograph by Stephanie Tavoularis, December 23, 1954.

© bettmann/corbis.

142 | chapter three

workers handed out copies of the issue of Paris Match featuring Abbé Pierre.

The film laid bare the poverty that haunted the prosperity of the trente glo-

rieuses with the poignancy and dramatic naturalism that marked the visual

perspective of these years. Emmaüs is presented as a world that taps into the

innate fraternity and camaraderie found among the peuple. The community

of workers builds a shelter as a celebration of collective fraternity. It is a geste

d’humanité celebrated with a song and the ceremonial handing over of the

keys to a waiting family, who open the door to their new home.

77

More than just good works, this self-help housing movement amounted

to a radical urbanism. It demonstrated passion and instrumentality at a local-

ized, self-directed level. The space of exclusion was transformed into a space

of freedom, and the poor were set in motion to reimagine and fashion their

urban realm. The margins of the city become a magical arena of urbanistic

design. Hundreds of barrel-shaped barracks (dubbed “igloos”) were set up

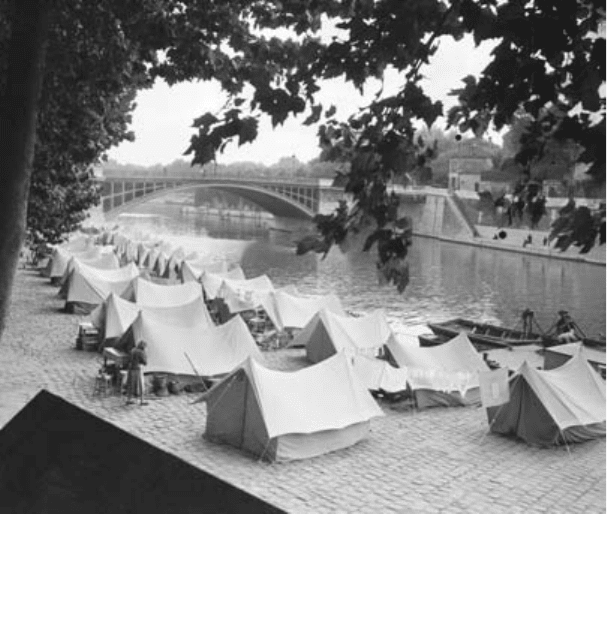

figure 13. Tent city for the homeless erected along the Seine River by Abbé Pierre. Photo-

graph by René Henry, October 1, 1955. © bettmann/corbis.

public space and confrontation | 143

at Noisy-le-Grand modeled after emergency shelters designed in 1945. In

an embarrassing slap at the sluggish MRU bureaucracy, under Abbé Pierre’s

direction the ragpicker-builders designed and built a complete model for an

efficiency home in six weeks. With the help of a public loan, they adopted the

avant-garde housing blueprints of the architect Jean Prouvé for an emergency

shelter development at Plessis-Trévise that was completed in two months.

78

In a signal of their populist political authority, in August 1955 Abbé Pierre

and his crew of ragpickers were filmed by film and television crews setting

up a cité d’urgence of tent shelters in the center of Paris, amid the traffic on

the pont Sully and the quai Henri IV. The images spotlight a family setting

figure 14. Abbé Pierre helping to install a low-income housing prototype designed by

Jean Prouvé along the Seine near the Alexandre III Bridge, February 20, 1956. © rue des

archives/agip.

144 | chapter three

up house inside one of the shelters, with the good wife and mother tending

to her family and the children tucked contentedly in bed.

79

Paris Match continued its coverage of the housing drama with a 1954

follow-up report on the poor couple who had lost their infant to the cold.

The narrative construction exudes populist poetic humanism. Paul and Lu-

cette had met at a July 14 bal populaire at Boulogne-Billancourt. He worked

at the Renault factory; she was a laundress. They had been thrown out of

their two-room apartment by an unscrupulous landlord. Paul first heard of

Abbé Pierre at the factory, and the family found shelter in the converted

bus at the Emmaüs community at Neuilly-Plaisance. By mustering all their

pitiful resources, Paul was able to buy the motorbike he needed to commute

to the Renault factory. But tragedy struck the young family with the death

of their infant, Marc-Petit, on that cold January night in 1954. And Lemaire

did indeed attend the funeral for the baby. He walked solemnly behind the

horse-drawn funeral carriage along with Abbé Pierre and his compagnons in

civic atonement for the tragedy. The sad procession wound through a miser-

able landscape of hovels gathered below the mammoth gas tanks of the cité

des Coquelicots at Neuilly-Plaisance. But at the narrative’s conclusion, after

terrible heartbreak, Paul and Lucette receive the keys to one of the first homes

in the emergency-housing village of Plessis-Trévis: three rooms, a kitchen,

a bathroom, and a garden. “Thanks to Abbé Pierre,” the Paris Match article

concludes, “the baby coming in the spring will be born in a real home.”

80

The end of Claudius-Petit’s tenure as reconstruction minister in 1953 is

usually seen by scholars as the key moment in the struggle for housing. In

this interpretation, state officialdom instinctively responded to the mounting

crisis and initiated a comprehensive policy of construction. However, in ret-

rospect it is clear that although 1953–54 was indeed the turning point, Abbé

Pierre’s campaign was the key impetus for change. People from a variety of

backgrounds joined together in common cause to create a highly mediatized

counterpublic sphere. Under increasing pressure, the government launched

construction of thousands of emergency housing units in the zone verte (as

the zone was then called) just outside the city limits. The marginal, forgotten

spaces of Paris emerged into public view and claimed a right to social jus-

tice. The French parliament voted to subsidize low-cost housing to the tune

of hundreds of thousands of francs, and it inaugurated a series of measures

aimed at expanding the stock of modest housing options: the reinstitution of

the wartime 1 percent charge on employers to finance lodging for their work-

public space and confrontation | 145

ers; a design competition, known as Opération Million, for durable, low-cost

family homes; the LOGECO program to stimulate the private construction of

reasonably priced residences; and the Plan Courant, which offered generous

loans (up to 80 percent of cost) for would-be homeowners. The winner of the

Opération Million competition, the architect Georges Candilis, conferred

with Abbé Pierre in the design and construction of a hundred buildings for

the poor at Bobigny, Blanc-Mesnil, and other communes around Paris. The

February 7, 1953, “Lafay Law” permitted the construction of residential es-

tates in the zone through a new system of expropriation. The measure provided

the first hope of relief from the housing crisis. In response, in December 1953

and January 1954 the municipal council approved a construction program

for 4000 housing units on seven different sectors of the zone. This shift in

government housing policy was triggered by the social tensions evident on

the streets of Paris. It was a reaction to passionate public protest and to the

magical urbanism carried out in the fragmented, marginalized spaces of the

city. The large-scale public-housing projects eventually put into place from

the mid-1950s on were meant to quell this social conflict and to counteract

the enormous influence of the communists and of Abbé Pierre, whose cam-

paigns on behalf of the working classes received overwhelming support.

The Presence of Undesirables

In 1949 Le Parisien libéré reported on the general attitude toward the growing

number of North Africans on the streets of Paris: “‘They are liars, thieves, lazy’

. . . this, without much interest in the fact that Moroccans are outstanding

workers in the most laborious jobs (in foundries for example), that the quasi-

totality of Tunisians in Paris live a perfectly normal life, that 30,000 Algerians

who have long lived in the capital have regular and honorable employment.”

Having said this, the newspaper went on to chronicle the dolorous condi-

tions that the 1,500 to 2,000 new arrivals each month found in ““verminous

slums” such as La Goutte d’Or, “in hovels in Gennevilliers, Argenteuil or

Boulogne-Billancourt where boards and pieces of carton take the place of

windows, where they hang out and are squeezed into the most lamentable

conditions, where a pair of shoes is a luxury for those who dreamt only a

month before of a brilliant return to their country, their fortune having been

made.” The paper estimated that some 80,000 to 90,000 North Africans lived

in these conditions—if they weren’t homeless, living on the street, hounded