Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

166 | chapter four

was the Paris of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Broadly speaking, it was not

so much a militant vision of the working class as a notion of a brotherhood

of people, that is, of workers and ordinary people who were wage earners of

all sorts. Secondly, intellectuals attempted to take up responsibility for the

rebuilding of France and openly ally with this populist community. They took

their cues from the militancy in the streets, from the strikes and demonstra-

tions, the ouvriérisme that resounded in the spaces of the capital. Coming

together in a renewed, progressive patriotism was a theme familiar from

the Resistance that continued through the reconstruction years. Joining the

Communist Party was one way for many prominent left-wing intellectuals

to struggle on the same side as the class of the future. The new elites would

help to nourish and improve the lot of working Parisians and give voice to the

silenced and ignored. The result was a humanistic vision of this victorious,

collective urban milieu that took hold of intellectuals from a variety of ideo-

logical sensibilities and backgrounds. Inspiration could be found among the

progressive, archetypal Parisians of the street. Even scientific investigations

of the city echoed this heroic imagery. The vernacular space of the city—the

experiences of the everyday and the outpouring of public life—was the arena

of social reconciliation and unity. Third, tradition and modernity were not

juxtaposed. The historicity of every element of space and landscape estab-

lished meaning and distinctiveness. The human scale of the neighborhood,

the social interactions, the improvisations and festivities that took place there

gave everyday life its own authentic, unstructured aesthetic.

The result was the construction from the 1930s through the 1950s of a

distinctively French approach to urban planning and to Paris. This vision of

a mosaic of petits villages—the natural and traditional spaces of community

for the classes populaires—was a far cry from that proposed by the modern-

ist mandarins attached to CIAM, or that envisioned by many technocratic

social reformers. High modernism envisioned a city no longer encumbered

with its history, its idiosyncrasies, its everyday culture. Urban topography

was imagined as cleared, vacant space, waiting to be filled with a monu-

mental morphology—new buildings and new notions of both the public

and private domain. Space was abstract, objective, and measurable, quali-

ties often encapsulated in the term “site.” Despite this normative vision of

modern postwar transformation, there was in reality no one single version of

modernism. Rather, there were a variety of modernisms that were debated

within and adapted to local contexts. It was in fact this multiform quality that

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 167

continually twisted and refashioned the notion of the modern city. French

intellectual elites were mesmerized by the richness of neighborhood collec-

tive life that was lived in the streets and spaces of Paris. They plunged into a

world of images and sensations that was peopled by whom they imagined to

be modern, self-actualizing, valiant individuals who found their strength in

collective existence. The landscape of Paris was poetic, humanistic, almost

sheathed in a golden dust.

The Populist Currents of Urban Sociology

An extraordinary intellectual debate took place in Paris in 1951 at the Deux-

ième semaine sociologique, sponsored by the embryonic CNRS and its first

research laboratory, the Centre d’études sociologiques (CES). The theme

was villes et campagnes. It was a pageant of the intellectual avant-garde that

would swing inquiry toward a more critical and applied appraisal of soci-

ety, the economy, mentalities, and history. Among the participants were the

historians Lucien Febvre, Fernand Braudel, Ernst Labrousse, and Louis

Chevalier. The sociologists were represented by Georges Friedmann, Alain

Touraine, Georges Gurvitch, Henri Lefebvre, and Paul-Henry Chombart

de Lauwe. The architect Robert Auzelle, the geographers Marcel Roncayolo

and Jean Gottmann, and the economists Alfred Sauvy, Jean Fourastié, and

Charles Bettelheim led the effort toward a multidisciplinary conversation

on the problems facing a rapidly changing France. The Villes et campagnes

conference reopened the public debate on French cities and exactly captured

this key moment of urban transformation. The backdrop was the clash be-

tween the rural world, where true French identity lay, and the urban one.

Ernst Labrousse began the event with a presentation that posited urban

life as a “conquering civilization.” Given what the gathering described as

the “permanence of the rural milieu as a distinctive social characteristic of

France,” was there any way to save it? Fernand Braudel answered that the

“rural world was not always lost.” Its distinctive qualities were profound

and resilient. The challenge was to find a policy that would reconcile the

two worlds—that would, in the words of Alfred Sauvy, “ruralize the city and

urbanize the countryside.”

3

It was an imagery that had resonated among

technocrats and intellectuals during the Vichy years (see chapter 7). There

remained, however, the particular “problem of Paris.” The capital, accord-

ing to the historian Lucien Febvre, was “the urban monster par excellence.

168 | chapter four

Because of its astonishing grandeur, at the local level, this city of Paris has

grown and developed so excessively with so many problems that I’ve never

seen anyone, up to today, consider this situation viable.”

4

Auzelle voiced anxiety about the traumas caused by reconstruction and

rapid urbanization, for which “it was difficult to see remedies.” In an interview

published in 1986, Alain Touraine described this early postwar French socio-

logical thought as carrying the weight of the French defeat and as “anxious

and somewhat pessimistic” about the changes the country faced.

5

Moderniza-

tion was certainly not new to France. But the difference was the accelerated

pace of change, which threatened to overwhelm the French way of life. This

apprehension was associated with urbanization and a conquering modern

rationalism. The trente glorieuses were shifting the terrain of everyday exis-

tence out of recognition. It was an overwhelming specter. The experience

of Paris was traumatizing. It siphoned off the vitality of France. There was

little to be said for it beyond the brutal commutes, dreadful housing, and

oppressive daily grind the growing population was forced to suffer. For the

intellectuals assembled at the Villes et campagnes conference, reconstruc-

tion was accelerating these trends with a frightening intensity. Modern post-

war life promised to disrupt traditional communities, create an increasingly

chaotic urban environment, and push people further into the grip of “mass

culture.” How had it come to this? The technocratic and intellectual elites

who had emerged from the war and who now sat together in this conference

in March 1951 had no intention of repeating the mistakes of the past. Their

motivations were shame over the catastrophe that had befallen France and,

springing from that, both a renewed patriotism and a belief in recovery. Yet

there was anxiety about the country’s future role. Humanism provided them

with a guide through this thicket of difficulties and with a form of heroic self-

affirmation. And Paris was the terrain on which they would carry out their

vision of universal brotherhood and cooperation.

Although experts were eager to help, little was actually known about the

working classes staging their street theater or about their genuine needs and

aspirations. Urban studies or urban sociology proper did not even formally

exist in France before the war.

6

Its progenitors were Maurice Halbwachs

and Marcel Mauss, both disciples of Émile Durkheim. The work of this

second generation of Durkheimians provided French intellectuals with a

massive interpretive framework. But in the context of postwar reconstruc-

tion, reliance on this theoretical corpus proved unsatisfactory. A variety of

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 169

intellectual voices called for demystification and genuine familiarity with

the working classes, for an understanding of their real world, the reality of

their lives, in order to improve their prospects through reform. Progressive

thinkers could no longer be cut off from ordinary Parisians, for it was they

who were leading the way forward. This shared desire to actually know what

was happening to the “workers” in postwar France, both in their daily lives

and in their work environment, and then to bring this knowledge to planners

and decision makers who could implement reform, constituted one of the

major intellectual motivations behind all postwar sociology. Social scientists

simply had to come to grips with the contextual aspects of everyday life and

space from the perspective of the people who lived it. There was a quality to

it of human solidarity and emotional union born from the Resistance and

Liberation.

Tony Judt makes the point that there was also an aspect of intellectual

“slumming” and condescension in this newfound humility and desire to help

the working classes.

7

The task was made easier by the heroic vision of the

worker that dominated in these years. Self-actualizing, moral, and good, with

a saintly glow that symbolized the soul of France, le peuple were infinitely ap-

proachable. Despite this idealized vision, there was a genuine desire among

thinkers from a variety of ideological casts to find common cause and a unity

of spirit with the working classes.

The new role of the sociologist was to take the pulse of French society

and organize a system of social knowledge that could influence the rapid

transformation taking place before their eyes. Georges Gurvitch, the director

of CES and convener of the Villes et campagnes conference, acknowledged

that it was up to teams of experts such as themselves to launch social stud-

ies and offer tangible reform and policy guidelines. As a result, a host of

geographic and sociological studies appeared about Paris immediately after

the war and through the 1950s. Some of it was a continuation of inquiries

carried on before the war, such as Demangeon’s exacting analysis Paris: La

Ville et sa banlieue, which first appeared in 1934 and was republished in 1949.

The geographer Pierre George and his research team published their find-

ings on the Paris suburbs in 1950, and the historian and demographer Louis

Chevalier completed a series of population studies of Paris for the INED

and, by the end of the decade, for the Institut national de la statistique et

des études économiques (INSEE). Chevalier dedicated some of his courses

at the Collège de France to urban sociology, and his Le Problème de la soci-

170 | chapter four

ologie des villes (1958) was the first major review of the discipline. Chevalier

thought that urban sociology based on scientific and statistical analysis was

by its very nature “associated directly or indirectly to public responsibility.”

8

He insisted on the importance of “working with the administration” to ac-

cumulate the data necessary for understanding the social composition and

the diversity of France’s cities—an approach, by the way, that did not make

use of American methodologies, which “[left] important problems in the

dark.”

9

Instead, Chevalier evoked Halbwachs’s analysis of collective memory

and the “stones of the city” in articulating the permanence of the Parisian

milieu, the “very particular form of sensibility, intelligence, spirit” specific

to the capital. Statistical and social science research required scrutiny at the

level of the quartier and its everyday life. There, sociologists and public ad-

ministrators would come to understand “the workers of Paris, the children

of Paris,” who Chevalier believed would benefit from public aid.

10

Sociologists became interactive, descending into the streets to study ordi-

nary people in their own world and the workings of their neighborhoods. The

class prejudices of elitist theoreticians who deigned to speak on behalf of the

lower orders they disdained would no longer be tolerated. Sociology would

be based on genuine fieldwork, on sympathy and respect for the sociologists’

subjects. A new emphasis on subjective meaning and “insider knowledge”

would reveal the ways in which people reflexively negotiated their life-world.

Working-class behavior, gestures, language, and social relations became the

material of investigation. This approach was a defense of autonomous popu-

lar culture, with its own collective space and practices. Chevalier’s work is

especially evocative of this interplay between analysis and imagination that

invented a naturalized, ethnographic spatial landscape. His population stud-

ies and his better-known Classes laborieuses et classes dangereuses (1958) were

based on exacting scrutiny of the pays of Paris that assumed a geographic

determinism. Chevalier argued that Parisian civilization exhibited different

characteristics depending on the quartiers. The criminality in Montmartre

differed from that in Belleville. In his flânerie through Paris, Chevalier found

poetry and pleasure, and an innate sensuality in urban civilization that per-

vaded every aspect of life. His intimacy with urban space produced as much

passion as scientific analysis.

11

All of these intellectual trends were crucial to the thought of the sociolo-

gist Paul-Henry Chombart de Lauwe. He had been a student of Halbwachs

and was also heavily influenced by Mauss. Like a number of French intel-

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 171

lectuals, Chombart discovered the French working classes during the war, as

a member of the Resistance, and in the post-Liberation years of reconstruc-

tion. It was this new awareness that moved him to switch his sociological

and ethnographic training from Central Africa to the classe ouvrière in Paris.

As with many of these midcentury social reformers, Catholic thought played

an instrumental role in the construction of Chombart’s social humanism.

His ideas were clearly guided by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin; by Catholic

social action movements such as Robert Garric’s applied-research “Social

Teams” in the northern districts of Paris, in which Chombart participated

before the war; and by the questionnaire methodologies of the Dominican

cleric Louis-Joseph Lebret’s Économie et Humanisme movement, founded

in 1941, with which Chombart maintained contact.

12

Their shared Christian

humanism was not ideological, but instead found its inspiration in concrete

projects for democracy and social justice. Vichy’s call for moral regeneration

initially offered the possibility of a spiritual rebirth for the nation. This ideal

helps explain why Chombart became involved in the Vichy regime’s Uriage

Leadership School. It was there that he began to outline his ambition of

“remaking contact with France” and learning the reality that the working

classes faced, not just from a disinterested empirical point of view, but be-

cause of “our affection for them and our desire to help them.”

13

It was also

at Uriage that he began to assemble his young team of researchers to carry

out the study of a grand cité.

Disillusioned with Vichy as it become more collaborationist, in 1942

Chombart joined the Allied troops in North Africa and served as an RAF

fighter pilot. With the war’s end, he returned to the Musée de l’Homme and

was eventually hired by the new CES as one of a number of unconventional

scholars largely ignored by French academic elites. In 1949–50 Chombart

set up the Groupe d’ethnologie sociale at the Musée de l’Homme to study

the behavior of the working class in the metropolis of Paris. Although French

sociology remained largely wedded to specifically productivist models, Chom-

bart’s interest was centered on the relationship between work and the needs

and aspirations of the working-class family in terms of lodging, space, trans-

port, and consumption—the conditions of their daily lives. Taking the local

working-class community as a framework, his research team analyzed the shift

from traditional urban neighborhoods to new forms of modern habitat and

their impact on families’ psychosociological welfare. In other words, in the

Chombartian universe, material conditions did not dictate social phenom-

172 | chapter four

ena and the city. Instead, urban morphology itself—that is, the spaces and

practices of urban life—reflected or represented society as a whole. Reading

the urban landscape was the best way to understand this framework of social

and economic relations. The result was Chombart’s Paris et l’agglomération

parisienne, published in 1952, a two-volume tour de force in the interdisciplin-

ary study of urban community that utilized interview techniques, a panoply

of social and economic statistics, cartography, and data on housing, disease,

violence, and juvenile delinquency.

14

For Chombart, only urban social science

methods such as these could provide the essential knowledge, the documented

basis from which public authorities could meet the needs and aspirations of

the city’s working population.

Chombart’s findings delineated the differences between bourgeois and

working-class conceptions of social relations. His research specifically distin-

guished the rhythms of everyday collective life in the eastern neighborhoods

of Paris from those of the beaux quartiers in the western part of the city. While

the bourgeois emphasized individuality and isolation from the urban milieu,

the worker looked for the social connections essential for survival. Collective

practices were mapped onto the dynamic spatial arrangement of daily needs,

the comings and goings of women and children, the pattern of commerce

and services, the going to and returning from work that together created the

intimacy and sociability of everyday neighborhood life. Pensée populaire was

elaborated in public places, at markets and fairs, and in family homes. The

basic unit of community life functioned in tangible, multifaceted spaces

that changed with the rhythms of daily existence. It was this rich collective

experience, imperceptible from the exterior, that tied together the working-

class community and offered families stability, shared memory, and social

cohesion. The connection between home and neighborhood was fluid and

open. The barriers guarding privacy were porous. The need to share outlooks

and experiences, to share the joys and pains of life, was more important than

preserving independence.

15

The Chombartian view of this world gave it a

rational social consciousness. It was obvious to postwar sociological thinking

that the neighborhood was a natural social unit closely knit by internal ties

and hidden away in the vast metropolis of Paris.

Paris et l’agglomération parisienne included meticulous geographic profiles

of the decentered spaces of the city. The level was the arrondissement, a spe-

cific sector, or an îlot. Although the arrondissement may have begun as an

arbitrary administrative boundary, it was interpreted as having evolved into

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 173

a “living unit.” At the next level down in the spatial hierarchy, the landscape

of social life was situated in discrete “familiar spaces” that represented a true

quartier. To focus even more intently on each neighborhood, the petite îlot

represented a natural unit whose boundaries and style of life were palpable.

16

The sociologist Jean-Pierre Frey has pointed to the commonalities between

Chombart’s social mapping of the Paris landscape and that of the urbanist

Gaston Bardet (see the next section in this chapter), who had created highly

detailed diagrams of the city’s fragmented social morphology before the Sec-

ond World War.

17

Both Chombart’s and Bardet’s underlying objective was

to understand the life of the quartier and the ways in which its inhabitants

interacted informally to create a sense of community and spatial organization.

They shared an organic, naturalist conception of the lived environment. The

analysis invented a picture of how people appropriated place to their needs

and aspirations and portrayed the spatial representations and practices that

shaped milieu. This information could then be used by planners whose objec-

tives were to renovate Paris and create new suburban communities around

it. Most important, this vision of the traditional working-class quartier and

îlot acted as a counterpoint to descriptions of depraved urban slums or îlots

insalubres, code words for clearance and removal. Chombart’s lens magnified

the viability and hidden beauty of social life in precisely these forsaken areas.

It became the rallying cry for his efforts to prevent the wholesale destruc-

tion of neighborhoods such as the rue Mouffetard, the Marais, or the rue

Nationale.

This shift in discourse can best be examined in the 13th arrondissement

on the Left Bank. It was one of the city’s densest industrial districts, packed

with the city’s old flour mills and the Say sugar refinery, the railroad and in-

dustrial networks around the gare d’Austerlitz, gas works and factories, the

automobile plants of Panhard & Levassor and SNECMA, the starch and

shoemaking workshops, and the breweries, tanneries and laundries along the

Bièvre River. And it was suffering a decline that was rapidly finishing off the

city’s traditional manufacturing sector, leaving miserable slum conditions in

its wake. Claptrap buildings in a maze of ancient alleyways and sordid lanes

offered shelter for working-class families, immigrants, and the poor. The entire

area was in an advanced state of decay. The sector known as La Gare, situ-

ated behind the gare d’Austerlitz between the boulevard de la Gare (now the

boulevard Vincent Auriol) and the boulevard Masséna, was identified as part

of îlot insalubre 4 on the city’s official register of slum districts. It contained

174 | chapter four

some of the most notorious cours de miracles in the city: the cité Doré and

in particular the militant cité Jeanne d’Arc, where political protests in 1934

had reached insurrectionary proportions. The confrontational atmosphere

meant they were slated for slum clearance without delay—among the few

partial projects carried out in the interwar years. The rue Nationale and the

axis of the rue Jeanne d’Arc, the rue de Patay, and the rue de Tolbiac were

the district’s main arteries. All of these blighted areas were delineated by city

officials according to a well-established discourse on social hygiene and pub-

lic health: rates of tuberculosis and contagious diseases, alcoholism, infant

mortality, housing conditions, and “intellectual instability and immorality.”

18

The closure of the old Ivry gas works in particular had left the area in a state

of advanced neglect, represented by the bleak, dejected rue du Château-des-

Rentiers.

It was to La Gare that Chombart’s young research team went to discover

the social spaces of the working classes. Nearly fifty thousand people lived

in the neighborhood, which according to their study, “has a bad reputation:

there is a homeless shelter on the Château des Rentiers, a cité Jeanne d’Arc

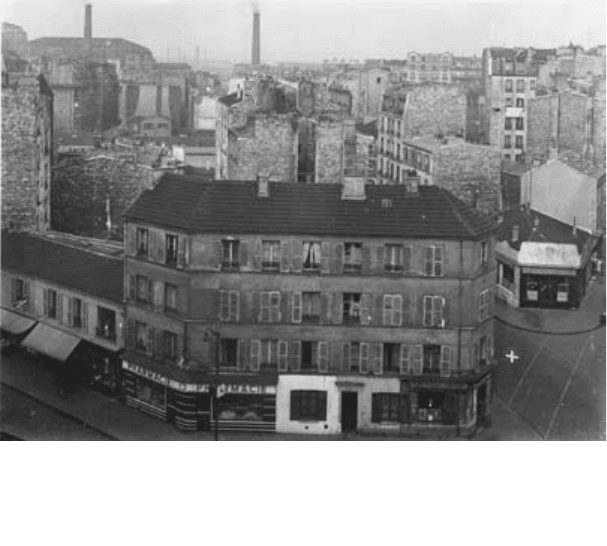

figure 18. View of îlot 4 and the rue du Château-des-Rentiers, March 8, 1951. © coll.

pavillon de l’arsenal, clich duvp.

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 175

peopled by ragpickers, seedy dance halls that offer cheap wine, houses of pros-

titution.” Miserable shanties and abandoned depots left to ruin were inter-

spersed with vacant property, putrid canals, and railroad lines. North African

immigrants lived squeezed together in cheap rooming houses, along with new

arrivals from Vietnam and the rest of Asia. Algerian bars attracted the police.

Wandering through the district in 1954, the writer Jean-Paul Clébert called

it a “neighborhood fertile in tip-off meetings, a region littered with shelters,

clinics, poor houses, philanthropic good works, Nicolas Flamel on the rue du

Château-des-Rentiers, Le Corbusier—the A.S. skyscraper called the White

House—rue Cantagrel.”

19

Chombart’s team set to work studying the area’s

history, demography, and density, and the quality of its lived environment:

its public spaces, its circulation and transportation patterns, its workforce, its

commerce and local economic life, its recreation and entertainment activi-

ties. The mix of data was mapped in a sociopsychological cartography that

located distinct quartiers and îlots and graphically distinguished every aspect

of the area’s everyday life with diagrams and maps filled in with patterns of

lines, shading, and contoured shapes. The vision was organic, immediate. The

results gave a stunning portrait of La Gare as a dynamic “little city” with a

diverse social life, and it delineated the specific needs of the community.

20

Chombart and his team were crucial to the postwar development of

French urban sociology. Their research was a product of a left-wing Catholic

social reform movement that was open to social science methods, especially

the neighborhood surveys of British social reformers in London and the ur-

ban ecology approach of Anthony Burgess and Robert Park in Chicago. As

a spatial imaginary, it mapped collective practices to a heterogenic ideal of

“place.” Their investigations were also illustrative of the interactional posture

of French urban sociology and the close bond between research and the state.

Chombart’s relationships with Auzelle (who had been in the same military

unit as Chombart and became a top official at the Ministère de la construc-

tion et de l’urbanisme) and to Paul Delouvrier (a companion from the Uriage

Training School) were instrumental in establishing relationships with the

state planners who would carry out indispensable reforms. The research for

Paris et l’agglomération parisienne, done in association with Auzelle’s Centre

d’études de la Direction générale de l’urbanisme (study center on urbanism)

at the MRU, helped to sharpen the diagnostic tools for state urbanists faced

with reconstruction and the renovation of slum districts. A series of grants

from the MRU, the Commissariat général du Plan, and the District de la ré-