Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

186 | chapter four

distinctively shaped, articulated spaces. This perspective was a result of his

association with Chombart, with whom he frequently “discussed ethnol-

ogy and anthropology,”

37

as well as the influence of Bardet’s notion of “cit-

ies within cities.” Rather than simply understanding it as an urban parcel,

the street and the cours or public square were articulated as the elemental

spaces of collective life. In 1939, in îlot insalubre 16, in the Marais between

the churches of Saint-Gervais and Saint-Paul, Auzelle and Sébille proposed

building renovations rather than complete demolition, the conservation of

ancient roadways, and if necessary, the clearing out of bâtiments parasitaires

(parasitic buildings) to “open up” the local landscape of traditional public

courtyards and squares.

38

By the war’s end in 1945, Auzelle was in charge of a number of recon-

struction projects being carried out by the newly established MRU, and in

1948 he was named director of the study center for the MRU’s Direction

générale de l’urbanisme et de l’habitat. His Technique de l’urbanisme, pub-

lished in 1953, was instrumental in opening up the debate about urbanism to

the larger public. In 1947 Auzelle enlisted Chombart for a diagnostic study

of the suburban development of La Plaine at Clamart in the department

of Hauts-de-Seine north of Paris. The evaluation would “take the pulse” of

place and social environment for state planners, who would then use it to

thread the distinctive character of the neighborhood into their redevelopment

schemes. Around fifty of these diagnostic studies were done under Auzelle’s

guidance between 1950 and 1955, particularly within the context of his col-

laboration on Chombart’s momentous investigation Paris et l’agglomération

parisienne. They included Auzelle’s use of the maquettoscope, which added a

telescopic lens to aerial photography in order to take highly detailed images

of the built environment, infrastructure, social and commercial networks,

and topography of sites under renovation. According to Auzelle, these kinds

of multifaceted site studies were the key to successful urban redevelopment

and the reenergizing of local collective life.

39

Swooping down on the city as

if to catch it unawares, the aerial sequences sited, surveyed, and opened the

city for examination. In many ways they shared the same visual perspective

as the commercial films produced about Paris in the 1950s (see chapter 5).

The renovation of La Plaine at Clamart from 1947 to 1952 was one of

the most eloquent counterstatements to the eventual policy of grand ensemble

suburban housing complexes. His design took into account the social needs

of community and neighborhood as well as existing architectural volumes,

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 187

views, and the natural environment. An unpretentious permeability existed

between the street and the interiors of homes. A complete range of some

two thousand new dwellings were constructed in a series of îlots urbains that

were oriented toward the streets and modeled after his vision of the garden

city. New construction respected the scale of existing historic structures. A

greenbelt threaded through the new district, linking playgrounds, the com-

mercial center, schools, and church. Strict traffic regulations limited the types

of vehicles allowed access to the all-important network of community lanes

and roads that represented neighborhood spatiality and sociability. Develop-

ing his methods through the 1950s, Auzelle carried out a diagnostic study of

“sector 7” of the infamous zone surrounding Paris that would be developed

under the Lafay Law for the construction of housing estates. The area from the

porte de Pantin to the porte des Lilas was subjected to excruciating analysis

of topography and soil quality, historical evolution, population, and social

and community services. The result was a plan that privileged neighborhood

groupings or îlots composed of different housing blocks (“some low, some

high”) centered on a community complex of public services, school, and

church.

40

Auzelle’s work exemplifies the attentiveness to temporality and distinct

spatiality that characterized an alternative French vision of modern urban

planning at midcentury. It was distinguished by the deep relationship between

urban planners and sociologists and the way they interacted in their research.

Urbanists shared a social-reformist orientation and a humanist approach

that steered away from monumental designs for the capital and instead frac-

tured the space of the city into îlots, or naturalized neighborhoods of lived

experience. In other words, urbanisme was translated as social reform—or,

perhaps more exactly, as the opportunity to redeem a population shattered

by war and mounting daily struggle. It was in many ways an extension of the

reformist or social municipalism of the 1930s, which was based on the notion

of a social contract and new social rights through expert knowledge of the

city. This discourse ennobled the working classes and what were perceived

as their indigenous collective spaces. Taken together, this reading of Paris

created an influential planning corpus that largely eschewed the tabula rasa

of modernist universalism and instead attempted to invent a particularist

vision of a progressive, twentieth-century capital. Modern urban planning

would be assimilated into the city’s historic cultural geography. Planners

imagined Paris as a timeless web of vernacular districts, historic buildings,

188 | chapter four

and monumental stage sets. Here lay the creative tableau upon which France

would press forward into a modern renaissance and regain its glory. The

city’s historic places were to be protected and its quality of life enhanced by

rejuvenating neighborhoods both in the central city and in the suburbs. Just

as the îlot acted as the wellspring of social life in the city, the cité-jardin was

to be the basic social unit of the suburbs. Twentieth-century urban planning

and social reform would revive the magnetism of la ville lumière and represent

the unique character of French modern.

The Avant-Garde

This third section of the chapter looks at the shared visions of Paris among

the postwar avant-garde, specifically from the perspective of the lettrist move-

ment, which would eventually evolve into the Situationist International (SI),

and of the writers Léo Malet and Henri Calet. The literature on the SI in

particular is distinguished by its quantity and its exceptional quality, and it

is not my intent to go over such well-cultivated ground here. On the other

hand, the brilliant urban reportage of Malet and Calet is far less well-known.

41

Rather than focusing with exactitude on the œuvre of each, my purpose is to

situate these actors or, even more pointedly, these wanderers as they crossed

and crisscrossed the spaces of Paris along with Auzelle, Chevalier, Chombart,

Prévert, and Ronis—each of them carrying out their urban mapping, pointing

their cameras and their maquettoscopes, recording the layers of meaning in the

city’s spatiality, and creating a common portrait of an idiosyncratic, natural-

ized urban topography. They shared an ethos of descending into the streets

to discover the city’s soul. Together their narrative imagery infused Paris with

a moral aesthetic that was humanist, populist, and ultimately poetic.

There is no doubt about the continued influence of the prewar avant-garde

movements and especially of surrealism on postwar intellectual and artistic

elites. In the case of France, the aesthetic continuities across the Second

World War may be more interesting than the ruptures, especially in relation

to experiments in urban space. In fact, cultural historian Pascal Ory argues

that it is a mistake to see surrealism as a movement of the prewar years. The

real victory of surrealism dates from the Liberation, when the generation that

had shared a youthful phase of surrealist avant-gardism came into their own

as the new elites.

42

Prévert, Lefebvre, and Raymond Queneau were the cul-

tural celebrities of the late 1940s and 1950s. Surrealism encouraged them to

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 189

confront life, reality, and the urban nexus from a capricious, radical trajectory.

The surrealists imagined Paris spatially. The monumental spaces of moder-

nity, the grands boulevards, the cafés and shopping districts, the flamboyant

and monumental face of the capital were cast off as touristic, effete, without

spontaneity. Instead, the surrealist itinerary wound through the populist,

ordinary spaces of the city in neighborhoods such as Les Halles, Saint-Paul,

and Saint-Merri. It was there that individuals could situate themselves and

find a sense of identity, meaning, and value. The experience of space piqued

the imagination and insight into the self as well as the surrounding city in a

“topography of subjectivity.”

43

Personal identity and destiny are manifested

in the encounter with the urban setting. The streets and spaces of Paris are

arenas of possibility, of individual metamorphosis, of emotion and play.

The postwar movement that most closely followed in the footsteps of the

surrealist urban wanderer was the lettrists, which formed around Debord and

Jean-Isidore Isou in the 1950s. As Isou shouted at the January 8, 1946, Paris

premiere of Tristan Tzara’s play La Fuit at the Vieux-Colombier Theater in

Saint-Germain-des-Prés, “Dada is dead! Lettrism has taken its place!” Isou

saw the Lettrists as a youth movement that would carry on a post-Dada

avant-garde art for the new age. The promise that “12 million young people

will hit the streets in the lettrist revolution!” was scrawled onto the walls of the

Left Bank.

44

The movement’s stomping ground was Saint-Germain-des-Prés,

and its experimental landscape was Paris. The inflammatory antics produced

by this antecedent of the SI around both its artistic production and infight-

ing were its own form of street theater. In April 1950 they disrupted Easter

Sunday mass at Notre Dame by posing as priests chanting condemnations

against the church and exhorting parishioners to “exalt in a land where God

is dead.”

45

The founding document of the Lettrist International, the first to

break away from Isou’s group, was duly signed at Aubervilliers by Debord and

a few followers, shoved in a bottle, and thrown into “the sea” (the canal). They

disrupted a Charlie Chaplin press conference at the Hôtel Ritz in October

1952. They painted graffiti on the city walls. Members of the group produced a

“spoken” news bulletin lasting for two or three hours from a bench on the place

Saint-Sulpice. Provocateur allies of Debord rained stink bombs and sneezing

powder on the audience trying to fathom a showing of Hurlements en faveur de

Sade at the Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin in June 1952. This was precisely the

kind of clownish Left Bank agitprop theater that subverted the society of the

spectacle. Debord and his band snubbed the existentialist scene at the Tabou

190 | chapter four

and the Rose Rouge nightclubs to find more unpretentious, cheaper haunts:

the Mabillon and Old Navy on the boulevard Saint-Germain, the Chop Gau-

loise on the rue Bonaparte, and especially the Café Moineau on the rue du

Four. There they could merge into the inspired zone of the ordinary.

The lettrists pushed the notion of flânerie forward by roaming through

Paris in what they called the dérive or drift. To demystify the spectacle of

mass consumer culture, Debord and his band descended into the streets of

the working-class neighborhoods of Paris to explore the ludic culture that

survived there. Debord was fascinated by the dramatic urban social geog-

raphy of Chombart and his Paris et l’agglomération parisienne. Chombart’s

dissection of Paris revealed astonishing subtleties in the uses of the city and

the indigenous social associations at the level of the neighborhood. During

the summer of 1953, the lettrists went on “heroic expeditions” through the

alien microzones of Paris.

46

They drifted through the Chinese neighborhood

behind the gare de Lyon, to the “beautiful and tragic” rue d’Aubervilliers and

the district of La Plaine, through the 13th arrondissement to the rue Sauvage

(which they described as “one of the most moving nocturnal perspectives in

the capital,” “more alive than the Champs-Élysées”),

47

on to the Saint-Paul

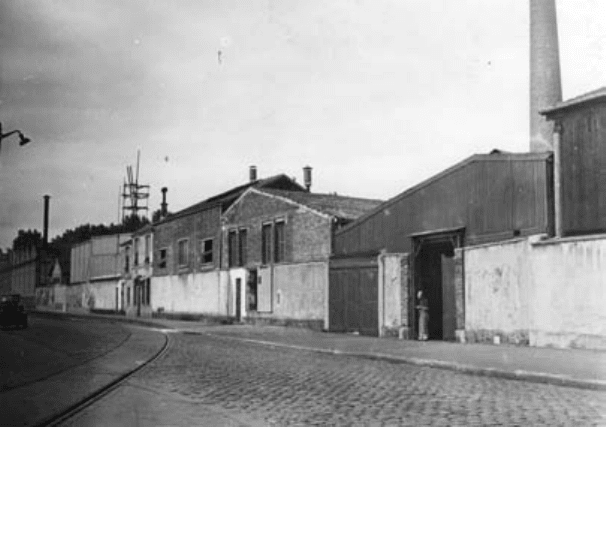

figure 19. The rue Sauvage, September 29, 1953. © coll. pavillon de l’arsenal, clich

duvp.

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 191

section of the Marais, across to Les Halles—and then slipped back across

the Seine to the Arab bar on the rue Xavier-Privas and to their headquarters

on the “continent” Contrescarpe and the cafés of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

In his 1953 “Formula for a New Urbanism,” in a naming ritual not unlike

that which took place after the Liberation, Ivan Chtcheglov (writing under

the pseudonym Gilles Ivain) discovered the mysteries of the city’s signs and

billboards:

Center for Functional Recuperation

Saint-Anne Ambulance

Café Fifth Avenue

Prolonged Willingness Street

Family Boarding House in the Garden

Stranger’s Hotel

Wild Street

And the swimming pool on the Street of Little Girls. And the police

station on Rendezvous Street. The medical-surgical clinic and the free

placement center on Goldsmith’s Quay. The artificial flowers on Sun

Street. The Chateau Cellars hotel, the Ocean Bar, and the Coming and

Going Café. The Epoch Hotel.

48

Street names and signs become a magical cryptography of neglected back-

waters. Texts on this activity were published in Naked Lips in 1955 and 1956.

Debord’s 1959 film On the Passage of a Few People through a Brief Moment of

Time included depictions of their “drifts” through the sinuous spaces of the

city, searching for eccentricity and the exotic, for play, for the erotic, for any

signs of freedom and refusal. The sublime was found in chance encounters,

in dubious characters and forbidden pleasures. In his 1950 pictographic tour

of “Saint Ghetto des Prêts” (Saint-Germain-des-Prés), the lettrist Gabriel

Pomerand described a place seething with legend and possibilities in every

chance encounter; every moment, word, building, person revealed an open-

ing into a secret utopia. “Saint-Germain-des-Prés is a ghetto,” he wrote;

“Everyone there wears a yellow star.”

49

Debord was fascinated by the deviant characters that inhabited these

emotive spaces. Drinking and drugs, carousing and run-ins with the police,

wandering the streets with slogans painted on their clothes, his band of fol-

192 | chapter four

lowers was itself a living example of détournement (diversion). In his seminal

article on situationist space, Tom McDonough points out that as a practice

of the city, the dérive “reappropriated public space from the realm of myth,

restoring it to its fullness, richness, and its history.”

50

But the lettrists were

hardly alone on these expeditions. The Liberation in August 1944 was of

course the ultimate model of appropriation and street theater. Debord and

his band were joined in the course of these pre- and post-Liberation years

by a youth pageantry of costumed zazous sporting yellow stars in dangerous

wartime resistance, existential beatniks in black roaming Saint-Germain-des-

Prés, and partying students dressed in the bizarre garb of the mônome de bac.

Weird styles and gestures, the farcical manipulation of symbols, and playful

carnival rites made up a subversive theater in the setting of the street. Play

and the festive produced novel environments. All manner of unexpected,

dangerous, potentially creative things could happen.

The perpetuation of this inspired bond between social marginality, the

avant-garde, and the everyday theater of urban space was remarkable. Jean

Vilar, the director of the Théâtre national populaire (TNP), dreamed of de-

mystifying French drama and moving it in a democratic direction. Writing in

Esprit in 1949, Vilar declared, “The pimps, the whores, sailors, workers, stu-

dents, concierges, bus drivers, drunkards, tramps, neighborhood shopkeepers,

the pretty young girls on the street, all mixed inside the theater are better for

our dramatic literature than the Saint-Sulpicien, the orthodox Marxist, or

the committed literati and the ex-prince of the black market.”

51

By midcen-

tury the conventional flâneur had transmuted into another, more subversive

figure—that of the vagabond-seer who alone possessed the marginal vision that

transgressed boundaries and turned them into thresholds. Vilar’s materializa-

tion of the all-seeing tramp haunting the city’s streets in Marcel Carné’s 1946

Les Portes de la nuit produced this way of seeing. “Revelation about life in a

city,” according to Jean-Paul Clébert, one of Paris’s greatest urban observers

in search of the strange, “is . . . reserved for the initiated, for very rare poets,

for the very numerous vagabonds, each of them drinking it in according to

their mood and their emotional capacity. And to conquer it you have to be

truly a vagabond-poet or a poet-vagabond.”

52

The avant-garde reached into

an ethnographic index of extraordinary Parisian street types to create scenes

of subjectivity and sensuality, of intuitiveness. Paris was less a European cul-

tural capital than a disjointed, quotidian theater of the exiled. The everyday

spaces of the city were the terrain of marginality, deviance, and subversion.

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 193

This was also a confrontation with individual psyche, a compulsive,

dreamlike search for the self. The lettrists mapped out what they called a

“psychogeography” of Paris based on their surreal, mixed-up drifts. A collage

was made of a torn-up city map in an intuitive cartography of space that was

subjective, disjointed, undisciplined. Their diagrammatic experiments led to

the publication in 1957 of The Naked City. The title was based on Jules Das-

sin’s American detective film The Naked City (1948),

53

which Debord held in

high regard. In fact, the similarities between the detective genre and Debord’s

psychogeographic collage of Paris, in which he hopes, as he writes in his 1955

“Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” to capture “the sudden

change of atmosphere in a street within the space of a few meters, the sharp

division of a city into zones of distinct psychological climates,” are unmistak-

able.

54

The parallels are clearest in relation to the narrative maps of Paris in

Léo Malet’s detective series Les Nouveaux mystères de Paris, written between

1953 and 1959. Malet is considered one of the founders of the French roman

noir, the detective fiction that was the literary analog of the film noir so ap-

propriate to the mood in France in the 1940s and 1950s. Although the series

won the Grand Prix de littérature policière in 1948 as well as the prestigious

Grand Prix de l’humour noir Xavier Forneret in 1959, it initially achieved

only limited popular success. A play on Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris

(1841), each novel in the series takes place in one of the arrondissements of

Paris. The setting is urban. The spaces of Paris are the central characters of

these novels, and Malet adored exploring and exposing their incongruities,

their life and death. His visual and anthropological perspective attempted to

capture the authentic essence of urban life in much the same way as did the

early situationists, or Chombart or even Auzelle. All attempted to penetrate

the superficial urban spectacle and grasp an authentic humanity and the

spaces of truth.

Malet lived most of his life on the edges of society and experienced

firsthand the marginality and disconnectedness the lettrists attempted to

capture in their dérives. He knew the reality of the city’s mean streets below

the mystifying spectacle of capitalism, especially in the 13th arrondissement,

where the new arrival from Montpellier at first found refuge in a vegetar-

ian hostel on the rue de Tolbiac. It was not far from where, in 1926, he was

found by the police, destitute, sleeping under the pont Sully.

55

Malet was

the vagabond-seer come to life. He was inspired by a mélange of influences

that included an early interest in anarchism. Employment in a series of low-

194 | chapter four

paying jobs helped him survive: dishwasher at Félix Potin, factory laborer,

telephone operator, newsboy, cabaret singer. These experiences would find

their way into his novels in pointillist detail. In the 1930s he discovered sur-

realism and found himself in the frequent company of André Breton, Paul

Éluard, Alberto Giacometti, and Louis Aragon. Imprisoned in Germany

after the June 1940 invasion, Malet was released in 1941 and returned to

Paris and the Left Bank. In 1952, desperate for a scheme that would earn

him money, he came up with the idea for a series of hardboiled thrillers

starring the detective de choc (ace detective) and flâneur extraordinaire Nestor

Burma, owner and sole operator of the Fiat Lux Detective Agency. Burma’s

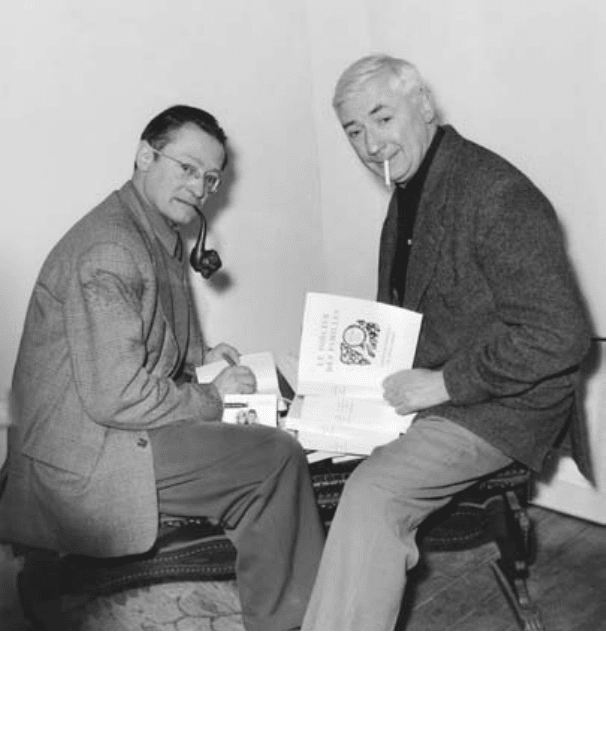

figure 20. Novelist Léo Malet and illustrator Felix Labisse with their book Les Nouveaux

Mystères de Paris, October 31, 1958. © rue des archives / the granger collection, new york.

spatial imagination and the avant-garde | 195

adventures begin during the Second World War and continue through the

1950s. In an autobiographical twist, he is, like Malet, a former left-wing

idealist and anarchist. Malet planned to have the character solve a crime

in each of the city’s arrondissements, and fifteen of the twenty books were

written.

Despite all the recognizable Parisian landmarks in these novels, there is

no one prominent center. Malet avoids the monumental capital in search of

the authentic life of the city, the lived experience revealed in the microscopic,

anthropological gaze of Nestor Burma. The urban fragments, the objects and

details, that typify the spaces of the city gain significance in an atmosphere of

a trivial, everyday actuality. Burma’s flânerie is little more focused than the

wanderings of the lettrists. True to his surrealist proclivities, Malet allowed

the story to take form as Burma strolled through the landscape, acting as

a surrogate for readers. In his notes on the flâneur, Walter Benjamin noted

the figure’s performance as detective. The role presented a “plausible front,

behind which, in reality, hides the riveted attention of an observer who will

not let the unsuspecting malefactor out of his sight.”

56

In tracking down clues

and duplicitous characters, Nestor Burma paces the city’s streets hunting

for the details, the unusual, instantaneous moments in the life of these ur-

ban places that will reveal the truth he is seeking. The precision of his gaze

is investigatory, almost photographic.

Both Debord and Malet attempt to lay bare the social body of the city.

Their urban landscape was feminine, ripe with sensuous, hidden qualities.

Malet’s lyric descriptions are atmospheric and at times erotic, first because

in detective novels the city is always feminine, and secondly because the po-

etic sentimentality is emotional and bittersweet. Debord too (and, for that

matter, Chevalier and Chombart as well) explored his passion for the city

and searched out the emotional feel of its streets, uncovering its secrets. Both

Malet and Debord splinter the map of Paris into fragments. They search for

tiny clues: Malet to solve a crime and Debord to transform urban life. And

for both, the fragmented spaces of the city can be experienced only by a

situated subject in a discrete period of time. The perception of place is dis-

tinct, particular to a localized urban milieu. Malet’s descriptions are exact;

they shape a topographic drama. Each arrondissement and neighborhood

is illuminated by the particularities of its landscape and its buildings, by the

continuity of its streets and spaces. Simple facts, bits of local lore, and fleeting

images are not merely inert, but take on the character of lived life. They are