Whitbread D. The Design Manual (анг.яз.)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

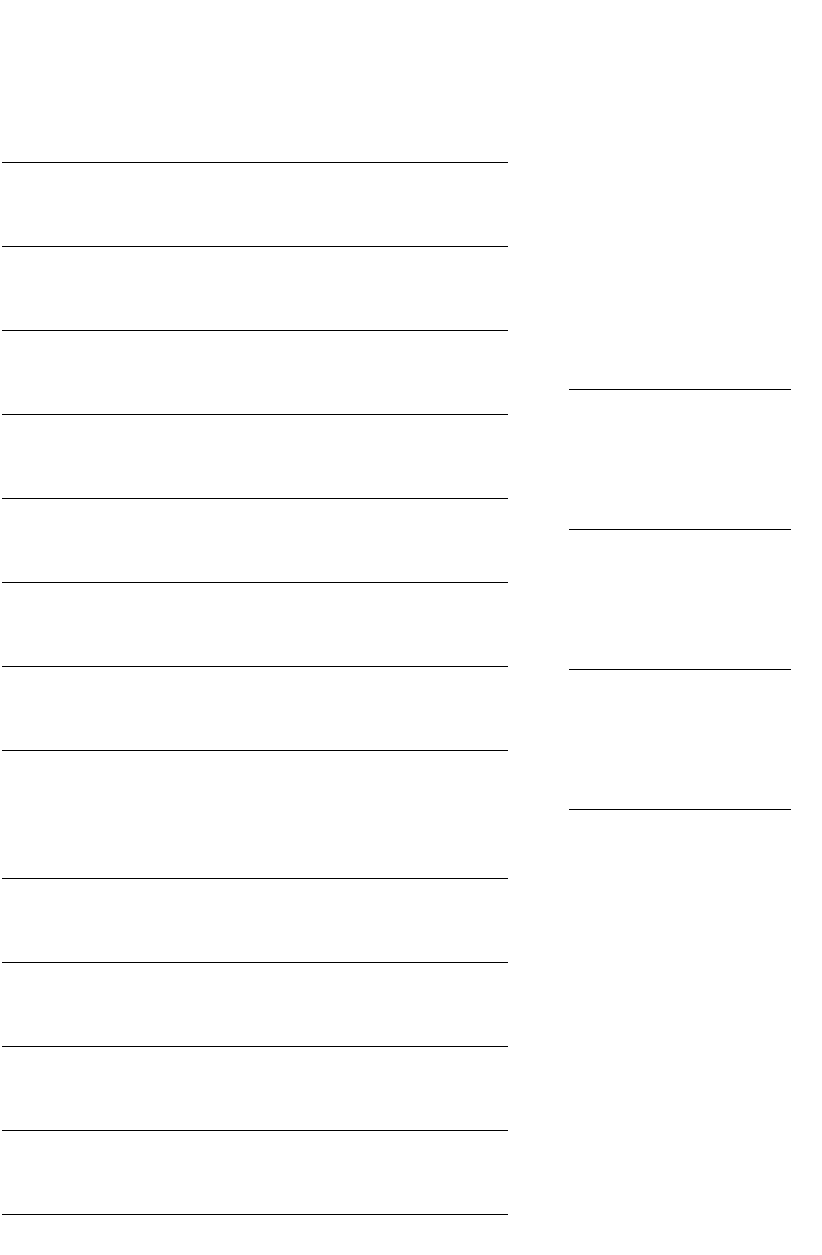

Typography 171

Serif typefaces

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Century schoolbook Morris Fuller Benton 1924

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Garamond Claude Garamond 1530

ABCDEFGHIJ 12345

Trajan Carol Twombly 1989

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Baskerville John Baskerville 1754

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Goudy old style Frederic Goudy 1915

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Times new roman Stanley Morison 1931

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Bodoni Giambattista Bodoni 1798

!"#$%&'()*+,-&./012

Palatino Hermann Zapf 1949

Optional names for Palatino: Palladium, Elegante, Andover,

Paladio, Patina, Malibu

ABCDE abcdefgh 12345

Bembo Francesco Griffo 1495

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Galliard Matthew Carter 1978

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Cheltenham Bertram Goodhue 1896

ABCDEFGH abcdefgh 12345

Matrix Zuzana Licko 1986

Serifs

Bracketed serif

I

Times new roman

Modern serif

I

Modern no. 20

Slab serif

I

Rockwell

All typeface examples are shown

in 18 point.

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 171

Slab serif typefaces

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Rockwell Inland Typefoundry 1910

Optional names for Rockwell: Stymie, Memphis, Cairo

ABCDE abcdef 12345

Clarendon English Fann Street Foundry 1845

ABCDE abcdefgh 12345

Italia Colin Brignall 1975

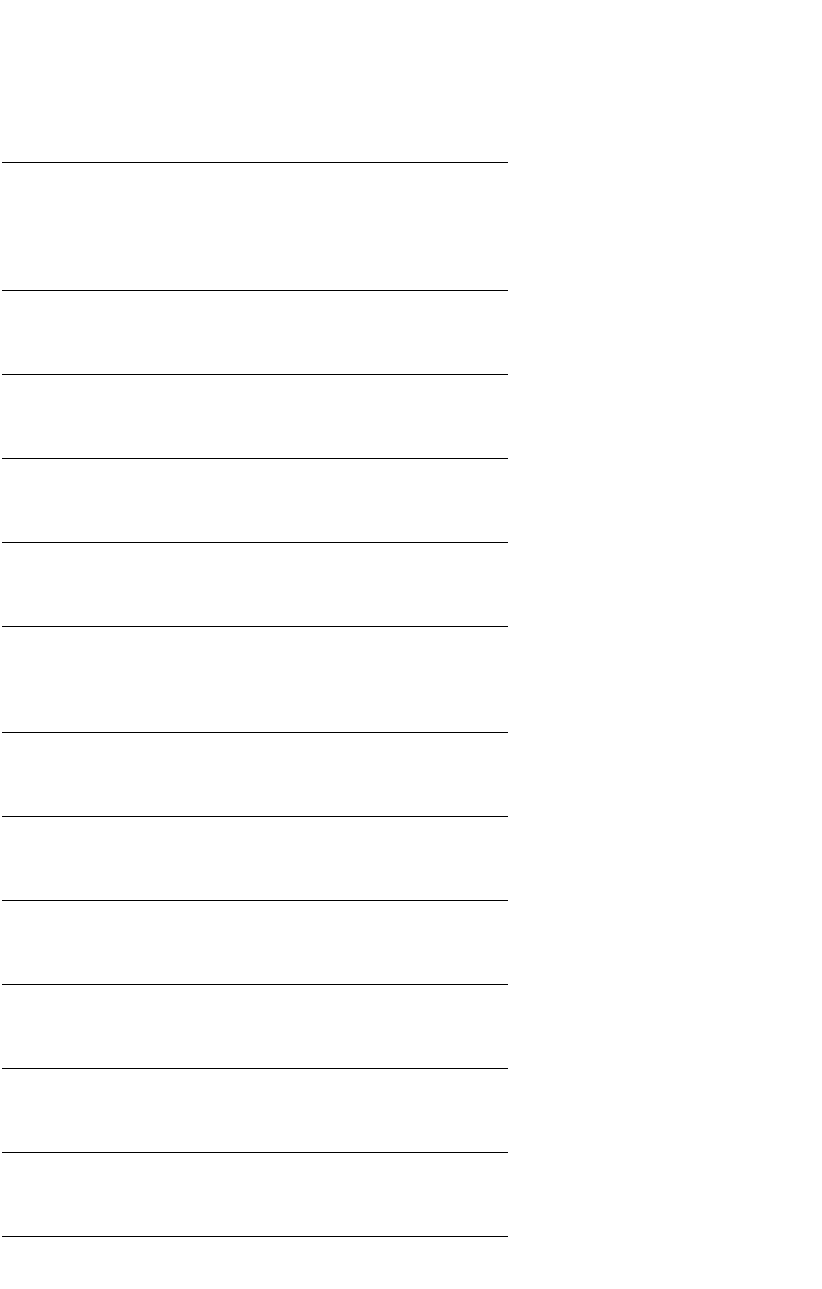

Sans serif typefaces

‘Sans serif’ is a French term, which means ‘without serif’.

Sans serif types used to be called ‘grotesques’ and that’s the

way some people prefer to think of them.

Though sans serif type is considered to be less readable

than serif type, it is the most legible type. When you learn

the alphabet, you are taught sans serif shapes because they

are the basic or ‘pure’ forms of the symbols, and therefore

the most legible or easiest to recognise letterforms. You

were probably taught to read using sans serif type.

Its greater legibility is one of the reasons that sans serif

type is used for headlines, billboard advertising and

numberplates, and for signage on highways, at hospitals,

in airport terminals and car parks.

However, as typefaces for text setting, they are consid-

ered ‘modern’, like the architecture of Le Corbusier. If you

want a futuristic or contemporary look, sans serif type can

help. This is probably because the ‘big name’ sans serifs

like Futura, Helvetica and Univers were developed in the

mid-twentieth century and sat comfortably with Art Deco’s

geometric designs and its development into streamlining

and, later, the international style.

Sans serif can look more informal or ‘friendly’ than serif

type, although some perceive the ‘clarity’ of a geometric

sans serif to be ‘clinical’ or ‘distant’.

Sans serif type also has the appearance of constant

stroke thickness. If you look at the capital A, all strokes

appear to be the same width. Because of this, they work at

very small sizes and in reverse—good news for people who

need to put photographers’ credits up the sides of photos,

write ‘Registered trade mark’ under a logo, or use any

other fine print.

172 Production

This is Rod.

This is Janette.

See Rod and

Janette run.

Futura

DOING IT SMARTER

Tiny type

Sans serif type remains quite

readable at even 3 or 4 point. You

should use wider letterspacing at

such small sizes.

Constant stroke thickness

A

Transit

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 172

Sans serif typefaces

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Helvetica Max Miedinger 1957

Optional names for Helvetica: Newton, Triumvirate, Helios, Swiss,

Geneva, Megaron, Claro, Vega

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Univers Adrian Frutiger 1957

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Frutiger Adrian Frutiger 1975

ABCDE abcdefgh 12345

Meta Erik Spiekermann 1991

ABCDEF abcdefgh 12345

Gill sans Eric Gill 1929

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Optima Hermann Zapf 1958

Optional names for Optima: Chelmsford, Optimist, Musica, Oracle, Zenith

ABCDEFGHIJ 12345

Lithos Carol Twombley 1989

ABCDE abcdefgh 1234

Franklin Gothic Morris Fuller Benton 1905

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Friz quadrata Ernst Friz 1965 (a hybrid serif font, used as sans serif)

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Futura Paul Renner 1927

ABCDE abcdefgh 12345

Template gothic Barry Deck 1990

ABCDEFGHIJKL 12345

Avant garde Herb Lubalin 1970 CAPS ONLY

Typography 173

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 173

Serif versus sans serif

Arguments rage about which style of type is superior.

Some people like to quote readability tests and all sorts of

statistics to back up their claims. But the fault with much of

the testing is that it starts from the assumption that serif

and sans serif types are interchangeable—that you can set

up your type specifications (which include the size of type,

the leading and the length of each line) and simply change

the typeface and run the test again. But you don’t specify

a holiday based on your car’s limitations, and then change

to an airline booking, without altering your schedule

and costing.

Each typeface category has tasks it performs well—

and there will be some tasks it will not perform well.

It is not usually the typeface at fault, but more what the

user does with it.

Scripts

Script typefaces tend to mimic handdrawn or calligraphic

type. The letters are often linked to each other, hence the

self-explanatory subdivisions of script called connecting

scripts and non-connecting scripts. There is also a subset

called blackletter based on Gothic pen letterforms which

was the form of the movable type Johannes Gutenberg

invented for his Bible published in 1455.

In nearly every case, script typefaces should be used only

in lower case with initial capital letters.

A mistake often made with wedding invitations and

other traditional uses of script faces is to choose a swirling

copperplate script typeface, which is often difficult to read.

Script typefaces can be used effectively but usually need to

be larger than 14 point and used for titles, and headings

such as ‘The Wedding of Jennifer and Matthew’, ‘The

Signing of the Register’, ‘The Exchange of Rings’. But when

it comes to readability, consider pairing them with a

classical serif which often works well with the traditional

scripts and blackletter fonts associated with weddings.

Contemporary scripts and casual scripts usually work

better with sans serif typefaces.

174 Production

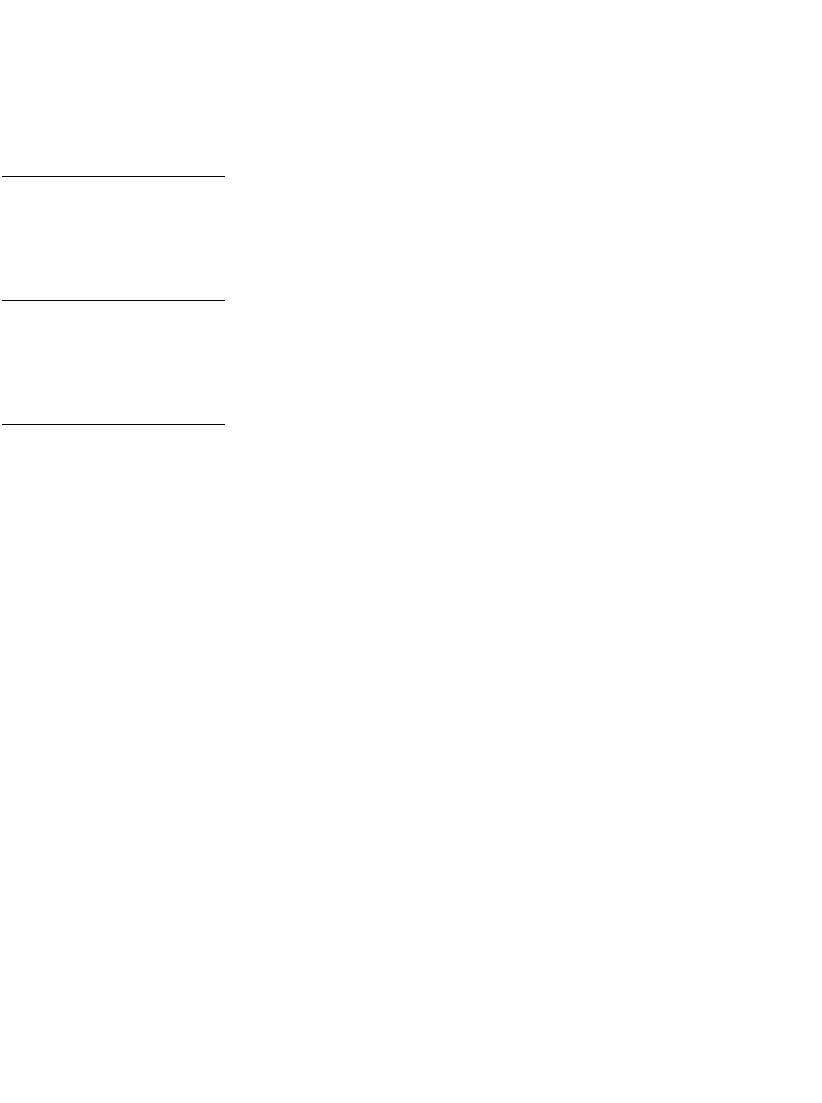

Compare a serif typeface

with a sans serif

Notice the serifs at the end of the

stroke and compare the thickness

and stress of the strokes.

So

Times new roman

So

Transit

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 174

Script typefaces

ABCDEFG abcdefghi 12345

Zapf chancery Hermann Zapf 1974

ABCDE abcdefgh 12345

Snell roundhand Matthew Carter 1965

ABCDEFG abcdefghij 12345

Kaufmann Max R. Kaufmann 1936

ABCDE abcde 12345

Brush script Robert E. Smith 1942

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Mistral Roger Excoffon 1955

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Sassoon primary Rosemary Sassoon 1990

ABC abcde 1234

American uncial Eisner and Flake

ABCDEFGHI abcdefghijklmno 123456

Erikrighthand Erik van Blokland 1991

ABCDEFGH abcdefghijklm 12345

Justlefthand Just van Rossum 1991

Blackletter typefaces

!"#$%&'()*+,-.&/0123

Old English Morris Fuller Benton 1901

ABCDE abcdef 12345

Fette fraktur Wagner and Schmidt 1875

ABCDEFG abcdefghijk 12345

Wilhelm Klingspor gotisch Rudolf Koch 1925

Typography 175

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 175

Specialty and display typefaces

Specialty typefaces can have letterforms that have been

adorned in some way. They are usually relegated to titling

and can lend atmosphere to a piece of text.

Avoid clichéd typeface choices in this category, such as

using letterforms with icicles on them for refrigeration

contractors and flame letterforms for ‘red hot’ sales—the

novelty has worn off and is less than successful.

Many decorative typefaces do not have a complete font

set. They may have only capitals, numbers and selected

punctuation marks. Often they aren’t extended into a family,

so you will rarely find an italic or a bold.

Symbol and picture fonts

There have always been dingbat fonts. They haven’t always

been called that, because it’s the American word used to

describe a font of symbols. Europeans used to call them pi

fonts (after the mathematical symbol pi—π), symbol fonts or

fleurons (or, in England, printer’s flowers). But what do they

do? Whatever you call them, they come in handy for:

r dressing up a pull-quote

r setting mathematical equations or formulae

r creating a border

r making some interesting bullets for a series of

dot points

r decorating a title page

r producing a piece of feature typography.

On forms, tick boxes are outlined squares. On business

cards and in Yellow Pages advertisements, instead of using

the word ‘telephone’, telephone symbols are often used. On

coupons, the scissors along the broken line are found in

dingbat fonts. There are many pointing tools (hands,

arrows, aeroplanes) that are used on pamphlets to highlight

product features and prices. In magazine and newsletter

pull-quotes, chunky opening and closing quotes are

sometimes dingbats.

There are some other uses you can put them to—

particularly as they are now installed on your computer and

can be used as you would use any other font. They can be

italicised, outlined, reversed, tracked and kerned, enlarged

or reduced, overlapped (horizontally by tracking, vertically

by changing leading, or, with even greater freedom, by

layering different text blocks), condensed or expanded

(using horizontal scaling), and their baseline can shift.

176 Production

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 176

Specialty or display typefaces, symbol or picture fonts

!"#$%&'()*%+,-.

Broadway engraved Morris Fuller Benton 1929

ABCDEFGHIJ abcdefghijklmn 12345

Playbill R. Harling 1938

abcdefgHIJK 12345

Neuland Rudolf Koch 1923

ABCD abcd 1234

Copperplate gothic Frederic Goudy 1901

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Typeface six Neville Brody 1986

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Typeface seven Neville Brody 1986

ABCDE abcdefg 12345

Fur extra rounded Paul Sahre 1993

ABCDEFGHIJ abcdefghijklmnopqrs 12345890

Industria inline Neville Brody 1990

Beowolf 23 Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum 1990

This random font will construct a slightly different letterform each time.

Typography 177

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 177

Specialty or display typefaces, symbol or picture fonts

abcdefgHIJ 12345

Osprey Stephen Farrell 1993

!"#$%&'()*+,&-./01

Verdana Matthew Carter 1996

This font was developed as a free-to-air font for the World Wide Web.

★✯➣♠♥♣●■▲☛❦✈✂

Zapf Dingbats Hermann Zapf

ΑΒΧ∆Ε αβχδεφγ ≤°∞ℑ♠

Symbol font

Decorated initials

178 Production

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 178

DOING IT SMARTER

Type families

Develop your awareness of the

capabilities of a type family by using

only one typeface and its variants.

That is, don’t rely on different faces

to create a hierarchy of information.

Insist that only one typeface (and its

family members) be used.

DOING IT SMARTER

Readable text type

Develop awareness of readability

requirements for text setting by

setting short pieces of fiction. Effort

is not expended on selecting heading

attributes, but focuses on the details

of creating good text—type

selection, leading, tracking,

justification, line length, etc.

If you need an angled oval, you can condense a circle by

slimming it down with horizontal scale, then italicising it

and, if necessary, rotating the text block to the desired

angle. However, it’s quicker and easier to do that with a

drawing tool.

Picture fonts have been released by some font producers

and are able to be distorted with type commands in the

same way. Picture fonts compete with clip art.

With these symbols and pictures available as a font, they

have the attributes of any computerised font—they are

much more flexible than dingbats used to be.

Typefaces, families and fonts

The naming conventions of typefaces are similar to how we

name one another—there is a family name and given

names to distinguish each of the family members. In type

nomenclature, the family name comes first. That is the

name of the typeface—Helvetica, Palatino, Garamond,

Frutiger. This is followed by the name of the family

member or font (or the English preference, fount)—bold,

medium, light, italic, etc. A ‘font’ is one set of capitals,

lower case, numbers, punctuation marks, symbols and

special characters.

Often, many fonts will exist within one typeface design.

The typeface is developed like a family—there is a set of

characteristics (based on the genetic make-up or the type

equivalent of the DNA of the originally drawn version) that

the resulting family members share. It might be a geomet-

ric detail, a particular shape of serif, a particular method of

generating a stroke or a more complex curve that recurs.

Each of the fonts is then given a name that describes its

difference from the original. If it leans to the right, it is

called italic or oblique. If it is slimmed down, it is called

condensed or narrow or compressed. If it gets wider, it is called

expanded. If its strokes get thicker and it looks darker, it is

called bold. If the strokes get even thicker, it is called

extrabold or black. If its strokes get thinner, it is called light.

If its strokes get even thinner, it is called extralight or thin or

fine. There are other variants, often self-explanatory, such as

outline, inline and shadow.

With all these variants taking the family name as well,

the original face is often given a font title—it could be

called medium or roman. If there is a font drawn between

the medium and the bold, it might be called demi or book.

Typography 179

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 179

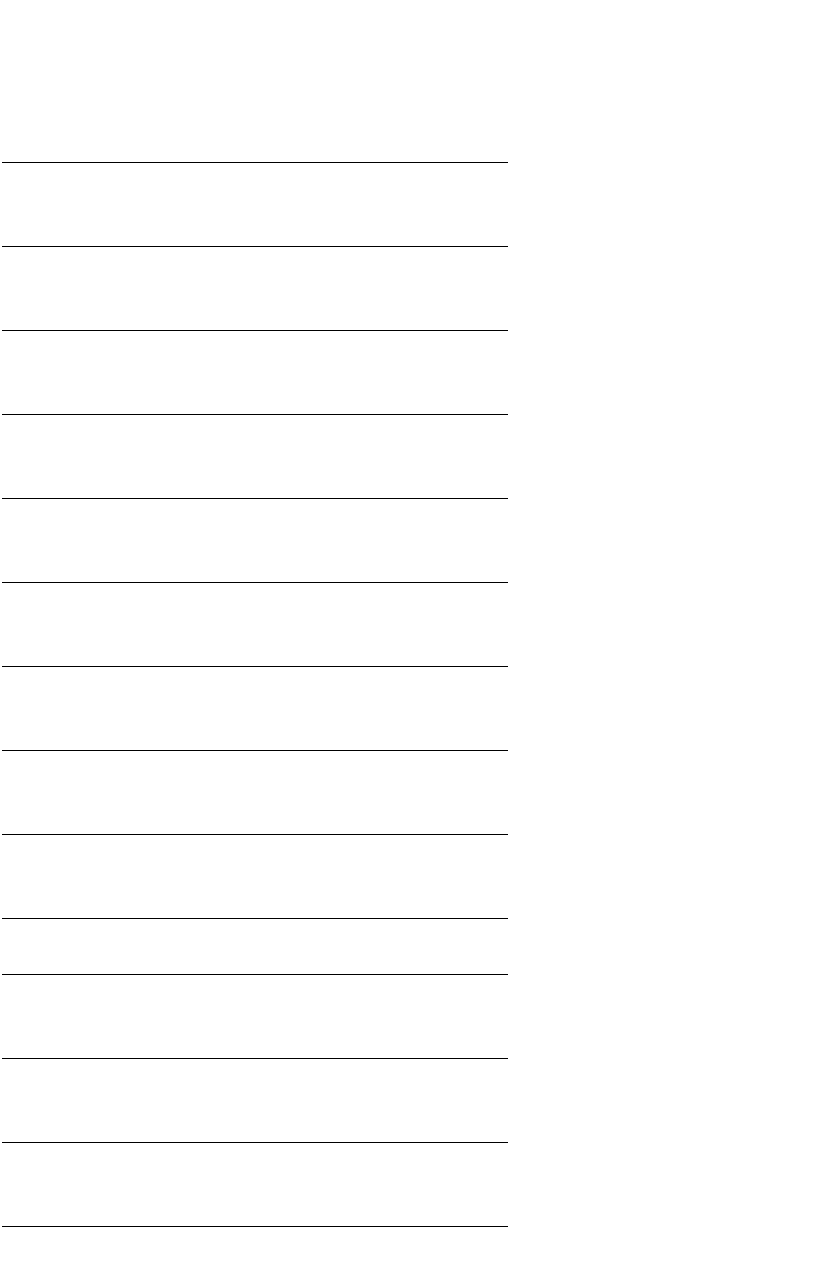

A font

Scala Martin Majoor 1990–98

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQ

RSTUVWXYZ

Capitals/upper case/majuscules

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuv

wxyz

Lower case/minuscules

abcdefghijklmnopqrst

uvwxyz

Small capitals

1234567890 1234567890

Oldstyle/text/non-lining numbers Lining/display numbers

-–—•&#

Hyphen En rule Em rule Bullet Ampersand Hash

180 Production

Expanded font sets

A specialist set or expert set will

mostly include:

q small capitals that are slightly

thicker and stockier than the

capitals so that they are the

same optical weight and spacing

as the lower-case characters

q titling capitals that are slightly

slimmer and narrower than the

normal capitals

q an oldstyle number set as an

alternative to the normal

aligning numbers

q full set of diacritical marks for

foreign language setting

q more ligatured character

combinations

q ‘true’ fractions

q optional swash capitals for

display setting

q optional ampersands

q a selection of dingbats in the

style of the font.

Æ æ Œ œfiflß $ ¢ £ ¥ e

Dipthongs Ligatures Eszett Dollar Cent Pound Yen Euro

ç ñ åäâáà˘¯˙ ı @ ©®™

Diacritical marks/accents (L–R: cedilla, tilde, ring, Dotless i Commercial Copyright Registered Trade

umlaut, circumflex, acute, grave, breve, macron, dot) ‘at’ mark mark mark

+=<>–÷≠√ .- %° π∑Ω∆µ

Mathematical symbols Fractions Per cent Degree Pi Greek symbols

:;?¿!¡\⁄/

Colon Semicolon Question Opening Exclamation Opening Backslash Fraction bar Solidus/

question exclamation slash

,.…*†‡§¶||

Comma Full stop/ Ellipsis Asterisk Dagger Double Section Paragraph Parallel

period (US) dagger marker marker lines

‘’ “” ‹› «» „ '" () [] {}

Single Double Single Double Base Foot Parentheses Square Braces

quotes quotes guillemets guillemets quotes and inch brackets

DWD-DM06 7/5/01 12:56 PM Page 180