Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Leaper S (1997) HACCP: A Practical Guide. Technical

Manual No. 38. Campden and Chorleywood Food Re-

search Association, UK.

Lupien JR and Kenny MF (1998) Tolerance limits and

methodology: effect on international trade. Journal of

Food Protection 61(11): 1571–1578.

Mortimore S and Wallace C (1994) HACCP: A Practical

Approach. London: Chapman & Hall.

Mossel DA, Struijk CB, van der Zwet WC, Heijkers FH and

Dankert J (1998) Identification, assessment and manage-

ment of food-related microbiological hazards: historical,

fundamental and psycho-social essentials. International

Journal of Food Microbiology 40(3): 211–243.

Nothermans S, Zwietering MH and Mead GC (1994) The

HACCP concept: identification of potentially hazardous

microorganisms. Food Microbiology 11: 203–214.

Pearson AM and Dutson TR (1995) HACCP in Meat,

Poultry and Fish Processing. Advances in Meat Research

Series, 1st edn., vol. 10. Glasgow: Blackie Academic &

Professional.

Philips J (1997) Food Standards Agency. An Interim Pro-

posal by Professor Philip James. London: FSA.

Roberts D and Hobbs BC (1993) Food Poisoning and Food

Hygiene, 6th edn. London: Arnold.

Sprenger RA (1993) Hygiene for Management. A Text for

Food Hygiene Courses, 6th edn. Highfield.

Tauxe RV (1997) Emerging foodborne diseases: An evolv-

ing public health challenge. Emerging Infectious Dis-

eases 3(4): 425–434.

Todd EC (1997) Epidemiology of foodborne diseases: a

worldwide review. World Health Statistics Quarterly

50(1–2): 30–50.

Voysey PA and Brown M (2000) Microbiological risk

assessment: a new approach to food safety control.

International Journal of Food Microbiology 58:

173–179.

FOOD SECURITY

J T Cook, Boston University School of Medicine,

Boston, MA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 This article is about food security in the USA and the

factors that promote it. It is also about poverty-

related food insecurity and hunger, their prevalence

in the US population, and some of their causes and

consequences. The article is not about normal hunger

per se, although normal hunger is a critical element of

the definition and measurement of food insecurity

severe enough to include hunger. Instead, this article

is about hunger that people in civilized societies agree

should not exist. It is about hunger experienced invol-

untarily in a country that claims to be the wealthiest

in the world; hunger experienced by several million

people because they lack adequate resources to afford

enough food for an active and healthy life. This kind

of hunger is most accurately seen as a social problem,

and the circumstances and managed process within

which it occurs are known as food insecurity.

0002 In pursuit of objectives of the National Nutrition

Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990, the

US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food and

Consumer Services (FCS) and the Department of

Health and Human Services’ National Center for

Health Statistics (NCHS) were assigned responsibility

for establishing a research program to develop stand-

ardized measures of food security, food insecurity and

hunger for the US population. That research program

was initiated in 1992 as the Food Security Measure-

ment Project (FSMP). In the first phase of this on-

going research program, a household-level survey

instrument was developed for annual administration

by the US Census Bureau as a supplement to its

nationally representative Current Population Survey

(CPS). In the second phase, data from the CPS

Food Security Supplement, administered to a sample

of approximately 60 000 households, were used to

create and validate a food security scale for the US

population.

0003The remainder of this article, briefly describes

the food security measures, their application over

the period 1995–2000 in the FSMP, and some of the

main findings from this research. I also discuss

aspects of the social, political, and economic contexts

within which the food security measures were applied

during this period as they relate to the causes and

consequences of food insecurity and hunger in the

USA.

What is Food Security?

0004The term food security came into usage over the past

two decades to describe a person’s, household’s, or

community’s ability to obtain enough nutritious food

for a healthy life. The concept of food security

initially emerged during the 1980s in international

2688 FOOD SECURITY

development work.

1

It was adopted in the early

1990s as a useful framework for describing, research-

ing, and designing policies to address poverty-related

food access problems at the household level in the

USA. Research conducted during the 1980s and

1990s in the USA found that household food security

is a managed process rather than a state or condition.

Within this framework, a household’s ‘food manager’

obtains, prepares, and makes food available to

household members in a way determined by the

household’s overall resources and preferences.

0005 When a household’s resources (usually de-

rived from money income and/or benefits from social

safety-net programs) are plentiful, it is likely to

be food-secure. If, however, household resources

become scarce for a period of time, the food manager

(usually the mother or another adult in the house-

hold) undertakes a managed process aimed at ensur-

ing that sufficient food will be available to enable

household members to avoid hunger.

0006 This managed process often involves a variety of

coping strategies undertaken to supplement the

household’s food supply. These include actions such

as putting off paying rent or bills, borrowing money

or food from friends or family members, reducing the

variety of foods prepared and served (often by cutting

out fresh fruits and vegetables), and relying on low-

cost ‘filling’ foods. The process of managing house-

hold food insecurity often involves considerable

emotional stress for members of the household as

worries about whether available food will last, or

whether there will be money available to buy food,

intensify. Households in this condition are said to

have become food-insecure.

0007 If a food-insecure household’s resource scarcity or

food insufficiency persists or worsens, the household

food manager may be forced to take actions that

lead to reductions in the quality and/or quantity of

food available to household members. In food-

insecure US households with children, it is typical

for adults to reduce their food intake below normal

levels (by reducing the size of meals, or skipping

meals) to spare the children from experiencing

hunger. However, if the household’s food insecurity

continues or becomes more severe, food intake by

children in the household eventually also will be re-

duced below normal levels. This usual pattern of

rationing makes it possible to identify two levels of

severity of hunger in US households; moderate hunger

and severe hunger. When the former occurs in house-

holds with children, usually only adults in the house-

hold experience hunger. With the latter, both adults

and children experience hunger.

What is Hunger?

0008Hunger is a feeling that everyone has some under-

standing of because all animals experience hunger,

as far as we know. At the individual level, hunger is

a physiological state or condition, a set of neuro-

logical sensations, and a psychological drive. Hunger

is an uneasy or painful sensation caused by a lack of

food, and it is a motivation to obtain and consume

food. We all know when we are hungry, and we can

even say how hungry we are and how it feels. We may

be ‘so hungry we could eat a horse,’ or we may ‘just

need a little something.’ For humans, hunger is usu-

ally a normal and healthy response to emptying of

food and nutrients from the stomach and upper

gastrointestinal tract.

0009But what about hunger that poor people in devel-

oping countries experience, or poor people in de-

veloped countries who do not have enough money

or other resources to buy, store, and prepare sufficient

food for a healthy active life? How is this hunger

different from ‘normal’ hunger? When does hunger

become problematic? At what point does it rise to the

level of a social concern? Is it when the motivation to

obtain and consume food cannot be satisfied due to a

lack of resources? How often must this condition

exist, for how long, and for how many people and

families before it is seen as a social problem that

merits a policy response? Historically, concerns about

food insufficiency have been articulated in terms of

malnutrition, undernutrition, and nutrient deficien-

cies. How are food insecurity and hunger related to

malnutrition? Are these conditions synonymous, or

can they exist independently?

0010These kinds of questions are critical to a clear under-

standing of food insecurity and hunger as social prob-

lems. They are also central to accurate definition and

measurement of food security, food insecurity, and

hunger, and to the design and implementation of ef-

fective policies to prevent or reduce these conditions.

Measuring Food Security

0011To design an effective research program for develop-

ing measures of food security, food insecurity, and

1

The term food security appears extensively in the work of the United

Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (UN/FAO), the Consultative

Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), the International

Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the World Bank, and other

international development organizations during the 1980s and 1990s. In

1994, the UN/FAO launched the Special Program for Food Security, ‘a

multidisciplinary program that combines expertise and experience from a

wide range of fields to promote an integrated and participative approach to

food security’. In November 1996, representatives from 185 countries and

the European Community met in Rome for the World Food Summit. Out of

that week-long conference emerged the Rome Declaration on World Food

Security and an accompanying Plan of Action to reduce food insecurity and

hunger by half in all countries by 2015.

FOOD SECURITY 2689

hunger for use in the public policy arena, a federal

interagency team first identified an appropriate

measurement framework. This measurement frame-

work expressed practical limits for the scope of the

measures and clarified the contexts to which they

would be applied and the type of instruments, data,

and analytical methods from which they would be

derived.

0012 Consensus conceptual definitions of food security,

food insecurity and hunger for the US context were

derived and published by the Life Sciences Research

Office (LSRO) of the Federation of Associations for

Experimental Biology (FASEB) in collaboration with

the American Institute of Nutrition (AIN) in 1990.

These conceptual definitions were operationalized,

and empirical measures of food security developed

under sponsorship of USDA/FCS and CDC/NCHS

in the Food Security Measurement Study (FSMS) of

1995–1997.

0013 Data from initial administration of the Food Secur-

ity Supplement in 1995 were used in a split-sample

procedure to create and validate a food security scale.

Population-weighted data were also used to produce

estimates of the prevalence of food security, food

insecurity, and hunger in the US population. The

Food Security Supplement has been administered by

the Census Bureau annually since 1995 as part of

the CPS. A time-series of annual food security data

and resulting prevalence estimates for the noninstitu-

tionalized US population by major sociodemographic

characteristics is available for the period 1995–2000.

In addition, overall state-level prevalence estimates

are available for 1995–1998.

Definition and Measurement of Food Security

0014 The conceptual definitions of food security, food in-

security, and hunger synthesized by the LSRO’s

expert panel have been stated as:

0015 Food security: Access by all people at all times to enough

food for an active, healthy life.

Food insecurity: Limited or uncertain availability of nu-

tritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncer-

tain access to food.

Hunger: The uneasy or painful sensation caused by a

lack of food. The recurrent and involuntary lack of

access to food . . . Hunger, in its meaning of the uneasy

or painful sensation caused by a lack of food, is . . . a

potential, although not necessary, consequence of food

insecurity. Malnutrition is also a potential, although not

necessary, consequence of food insecurity.

0018 Item response theory methods involving nonlinear

(logistic) factor analytic scaling models were used to

develop the 18-item food security scale from re-

sponses to a larger number of questions in the Food

Security Supplement to the CPS. When operational-

ized, the three conceptual categories listed above were

shown to represent adjacent levels of severity of a

single well-ordered phenomenon. Food security

emerged as a continuum, with households at the

least-severe level termed food secure, and those at

the most severe level termed food insecure with severe

hunger, as follows:

0019Food secure: Household shows no or minimal evidence

of food insecurity.

0020Food insecure without hunger: Food insecurity is evident

in households’ concerns and adjustments to household

food management, including reductions in diet quality,

but with no or limited reductions in quantity of food

intake.

0021Food insecure with moderate hunger: Food intake for

adults in the household is reduced to an extent that

implies that adults experience hunger due to a lack of

resources. If children are present, the quality of food

available to them may be reduced, but usually not its

quantity.

0022Food insecure with severe hunger: Households with

children reduce the children’s food intake to an extent

that implies that the children experience hunger as a

result of inadequate household resources. Adults in

households with or without children experience exten-

sive reductions in food intake.

0023The two categories including hunger are based on

survey responses indicating that food intake has

been reduced below normal levels (e.g., by reducing

the size of meals, skipping meals, or going a whole

day without eating) for adults or children in the

household, or both, and that these reductions oc-

curred specifically because the household did not

have enough food or money to buy food. Cut-point

selection procedures required that a pattern of repeti-

tion of such intake reductions occur for two or more

months out of the previous 12 months for hunger to

be confidently inferred. Thus, even though hunger is a

normal state experienced by all people, the Food

Security Scale was designed to capture recurrent re-

source-constrained hunger, experienced because a

household does not have sufficient food or financial

resources to buy food.

Prevalence of Food Insecurity and Hunger in the

USA

0024The Food Security Scale produces continuous inter-

val-level (without a true zero value) household food

security scores for all households in which an adult

respondent completes the survey. The continuous

scores are then used to categorize households into

one of the four categories just described on the basis

of cutoff values determined in the initial FSMS and

2690 FOOD SECURITY

validated with data from the five successive imple-

mentations of the scale (in 1996–2000).

0025 In recent years, with high rates of growth in the US

economy and very low unemployment, increasingly

smaller proportions of most demographic subgroups

experienced food insecurity with severe hunger. As a

result, USDA analysts combined the two severity

levels involving hunger and now report prevalence

estimates for three levels of severity only (food secure,

food insecure without hunger, and food insecure with

hunger). Table 1 shows the prevalence of these three

food security categories for US households and resi-

dents by selected characteristics in 2000, the latest

year for which estimates are available.

2

0026 Overall, 11.1 million US households (10.5%) were

food-insecure at some level of severity in 2000. In 3.3

million households (3.1%), at least one adult or child

experienced hunger.

3

Just over 33.0 million people

(12.1%) lived in food-insecure households in 2000,

and 9.0 million lived in households where hunger was

experienced. Examination of Table 1 shows that

people in households with children (ages < 18 years)

have almost two and a half times the risk of being

food-insecure as those in households without children

(relative risk (RR): 0.164/0.067 ¼2.4). People in

female-headed households with children and no

spouse have nearly three times the risk of being

food-insecure as those in married-couple households

with children (RR ¼2.8).

0027 Other notable comparisons of the prevalence of

food insecurity and hunger include those by race/

ethnicity of household, ratio of household income

to poverty, and area of residence. People in non-

Hispanic Black and Hispanic households have nearly

three times the risk of being food insecure as non-

Hispanic White households (RR ¼2.8 and 2.9, re-

spectively, compared to non-Hispanic Whites), and

people in central-city households have nearly twice

the risk of being food insecure as people in metropol-

itan households not in central cities (RR ¼1.9).

Households with incomes below 185% of the poverty

threshold have over six times the risk of being food

insecure as those with incomes greater than or equal

to 185% of poverty (RR ¼6.3). The prevalence of

food insecurity and hunger rises steadily as the ratio

of household income to poverty decreases (similar to

a dose–response effect), with the highest prevalence

among households whose incomes are below 100%

of poverty.

Food Insecurity, Hunger, and Malnutrition

0028It is important to note the relationships among pov-

erty, food insecurity, hunger, and malnutrition. In

the consensus conceptual definitions derived by the

LSRO/AIN expert panel (listed above) and operation-

alized in the FSMS, hunger and malnutrition are

described explicitly as ‘potential, although not neces-

sary’ consequences of food insecurity. Resource-

constrained hunger is ‘nested’ within food insecurity,

occurring at its more severe levels. It is accurate to say

that hunger, so defined, is both a necessary and suffi-

cient condition to imply food insecurity.

0029Malnutrition in its broadest meaning, however, is

neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition to imply

food insecurity or hunger, though it may. Malnutri-

tion, both as undernutrition and overnutrition, can

occur in the absence of food insecurity or hunger,

though either or both of these latter conditions may

be associated with malnutrition and may even cause

it. Clinically, however, there can be multiple causes of

malnutrition, some of which do not involve food

insecurity or hunger.

0030It is unlikely, in the absence of morbidity, con-

genital anomaly, or pathology, that protein–calorie

undernutrition occurs in the US population, unless

it is accompanied by relatively severe food insecurity

or hunger. However, it is not at all uncommon for

micronutrient undernutrition or deficiencies to occur

under conditions of food insecurity without hunger,

or even under food-secure conditions. Indeed, prom-

inent clinical concerns often arise due to micronu-

trient deficiencies associated with food insecurity

short of measurable hunger, or with only moderate

hunger.

0031In the past two decades, consequences of overnu-

trition have emerged as important factors in some of

the most serious threats to human health (e.g., dia-

betes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, ortho-

pedic conditions, sleep apnea, asthma, and cancer).

Overweight and obesity are epidemic in the USA

across nearly all age levels, with growing concerns

regarding emergence of obesity at earlier childhood

ages and implications for later body composition and

health. Trends in the US economy and society, includ-

ing effects of technological change on prices and

availability of food, patterns of food advertising,

marketing, consumption and eating behavior, work,

and physical activity, have led to conditions that

2

As of writing, the data for 2001 have been collected but not analyzed. The

USDA and the Census Bureau are preparing for implementation of the 2002

CPS survey.

3

Since questions in the Food Security Supplement do not ask specifically

about the conditions of each member of the household, it is not possible to

ascribe hunger status to all members of households with more than one adult

and one child. One can, however, ascribe overall food insecurity status to all

members of any household that is not food-secure. In addition, if a

household is categorized as ‘food insecure with hunger,’ it is appropriate to

say that all members live in a household where hunger is experienced. This

minor unintended limitation results from the specific form of the survey and

the questions it contains.

FOOD SECURITY 2691

support widespread overconsumption of calories

relative to daily needs.

0032 Since the 1970s, research literature has accumu-

lated, suggesting that food insecurity may play a

role in the onset of overweight and obesity among

some low-income subpopulations. Though the evi-

dence is not yet conclusive, there are several lines of

research currently underway whose results to date are

consistent with hypothesized associations between

food insecurity and obesity. To the extent that there

are associations between food insecurity and obesity,

affected low-income subpopulations may be doubly

challenged in their efforts to maintain healthy body

composition, diets and lifestyles.

Poverty, Food Insecurity, and Social

Welfare Programs

0033 A clear understanding of food insecurity and hunger

in the USA requires knowledge of their relationships

to poverty, and the range of social policies and

programs that have emerged to address both. By

definition, resource-constrained food insecurity is pri-

marily an issue for low-income families, or families

with limited resources. However, the nature of the US

economy, food system, and social welfare system adds

to heterogeneity in expression of food insecurity. The

way in which poverty and food security are defined

and measured in the USA also adds complexity to

relationships between these two conditions.

US Poverty Measures

0034When created in 1963, the US poverty levels were

based on the cost of a minimally nutritious diet.

Though these thresholds have been updated annually

since 1963 for inflation, they have not yet been re-

vised to reflect the change in proportion of total

household expenditures spent for food. In the 1960s,

the average household spent roughly one-third of its

total monthly expenditures for food (averaged over

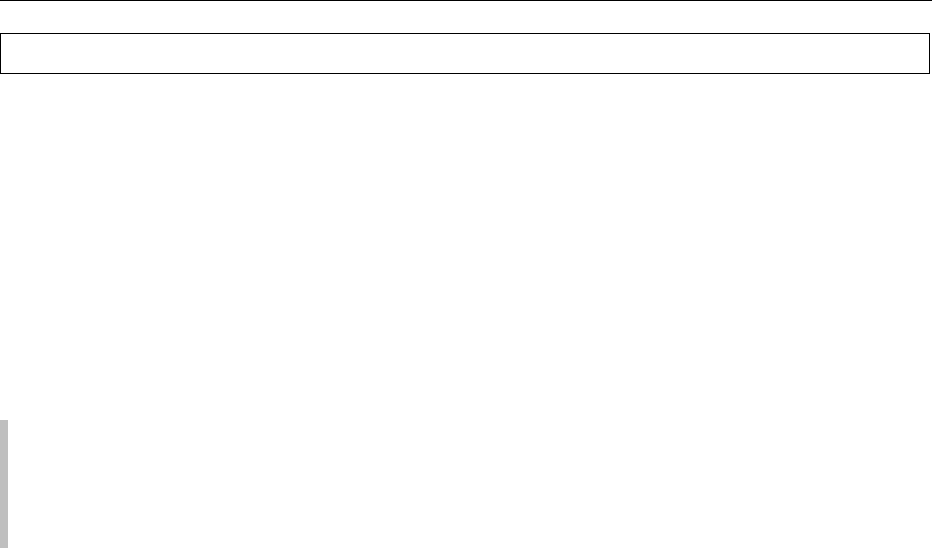

tbl0001 Table 1 Prevalence of food security, food insecurity without hunger, and food insecurity with hunger for persons by selected

characteristics of households: 2000

a

Category Total Food-secure Food-insecure (all) Food-insecure withno hunger Food-insecurewithhunger

(1000s) (1000) (%) (1000) (%) (1000) (%) (1000) (%)

All households 106 043 94 942 89.5 11 101 10.5 7 786 7.3 3 315 3.1

All Persons 273 685 240 454 87.9 33 231 12.1 24 708 9.0 8 523 3.1

Adults 201 922 181 586 89.9 20 336 10.1 14 763 7.3 5 573 2.8

Children < 18 years 71 763 58 868 82.0 12 895 18.0 9 945 13.9 2 950 4.1

Household composition

With children < 18 years 152 995 127 857 83.6 25 138 16.4 19 489 12.7 5 649 3.7

With children < 6 years 72 810 59 413 81.6 13 397 18.4 10 580 14.5 2 817 3.9

Married-couple families 112 734 99 496 88.3 13 238 11.7 10 782 9.6 2 456 2.2

Female head, no spouse 30 705 20 715 67.5 9 990 32.5 7 204 23.5 2 786 9.1

Male head, no spouse 7 410 5 964 80.5 1 446 19.5 1 123 15.2 323 4.4

With no children < 18 years 120 690 112 597 93.3 8 093 6.7 5 219 4.3 2 874 2.4

More than one adult 93 196 87 756 94.2 5 440 5.8 3 694 4.0 1 746 1.9

Women living alone 16 157 14 526 89.9 1 631 10.1 977 6.0 654 4.0

Men living alone 11 336 10 313 91.0 1 023 9.0 549 4.8 474 4.2

Households with elderly 47 580 44 416 93.4 3 164 6.6 2 396 5.0 768 1.6

Elderly living alone 10 125 9 409 92.9 716 7.1 523 5.2 193 1.9

Race/ethnicity of households

White non-Hispanic 195 171 178 962 91.7 16 209 8.3 11 759 6.0 4 450 2.3

Black non-Hispanic 33 505 25 755 76.9 7 750 23.1 5 631 16.8 2 119 6.3

Hispanic (of any race) 32 945 24 920 75.6 8 025 24.4 6 365 19.3 1 660 5.0

Other non-Hispanic 12 065 10 818 89.7 1 247 10.3 953 7.9 294 2.4

Ratio of household income to poverty

Under 1.00 33 447 19 750 59.0 13 697 41.0 9 763 29.2 3 934 11.6

Under 1.30 48 786 30 852 63.2 17 934 36.8 12 991 26.6 4 943 10.1

Under 1.85 71 509 49 402 69.1 22 107 30.9 16 279 22.8 5 828 8.2

1.85 and over 163 288 155 215 95.1 8 073 4.9 6 348 3.9 1 725 1.1

Area of residence

Inside metropolitan area 221 518 195 268 88.1 26 260 11.9 19 467 8.8 6 783 3.1

In central cities 65 772 54 511 82.9 11 261 17.1 8 451 12.8 2 810 4.3

Not in central cities 117 791 107 349 91.1 10 442 8.9 7 579 6.4 2 863 2.4

Outside metropolitan areas 52 167 45 186 86.6 6 981 13.4 5 241 10.0 1 740 3.3

a

Totals exclude households whose food security status is unknown.

From Nord M, Kabbani N, Tiehen L et al. (2002) Measuring Food Security in the United States: Household Food Security in the United States, 2000.

USDA/ERS Food Assistance and Nutrition Research Report No. 21. Washington, DC:

2692 FOOD SECURITY

all households at all income levels). In principle, this

implied that multiplying the average cost to house-

holds of a minimally nutritious diet by a factor of

three would provide an indication of the poverty

threshold, or the minimum amount of income needed

to meet basic needs.

0035 Using the cost of the USDA’s Thrifty Food Plan for

different size families as estimates of the costs of

minimally nutritious diets, the poverty thresholds

were obtained by multiplying these dollar values by

three. This remains the basis of poverty measurement

in the USA today. Elegant as it is in logic and simpli-

city, this measure only succeeds when the relative

proportion of the average household budget spent

on food is accurate. Setting aside the question of

whether this is the most accurate approach to esti-

mating the cost of households’ basic needs, a more

fundamental concern is whether the proportion of

household income spent on food has remained con-

stant over time.

0036 Since 1963, the average annual proportion of

household expenditures spent for food has declined

consistently to about 11% in 2000. Over the same

period, the average annual proportion of expend-

itures spent on other basic needs (most notably hous-

ing and transportation) increased consistently. As a

result, using the same multiplier logic underlying the

initial definition of the poverty thresholds with cur-

rent proportions of expenditures on food implies a

multiplier of approximately 9 instead of 3. Obviously

this would lead to much higher income levels being

identified as poverty thresholds, and much larger

numbers and proportions of people identified as

being in poverty.

0037 Another peculiar anachronism in US poverty meas-

urement is that households headed by elderly persons

(ages 65 and over) have lower poverty thresholds

than similar households headed by people under 65

years of age. This practice dates to an era in which

most Americans worked in occupations involving

extensive physical exertion, retirement from which

ostensibly reduced energy and other nutrient require-

ments and hence the cost of food for people over age

65. Depending on the size and characteristics of the

household (e.g., the number of related children under

the age of 18 years), poverty thresholds for house-

holds headed by elderly people are 4–10% lower than

for comparable households headed by nonelderly.

Thus, elder-headed households must have lower

incomes (be worse off financially) than nonelder-

headed households before they are classified as being

in poverty. As a result, the number and proportion of

elderly households and persons reported in poverty

understate the actual extent and dimensions of pov-

erty among the elderly. In turn, this affects eligibility

for assistance from various social welfare programs

among some elderly who may be in need.

0038Support for the view that the current poverty

thresholds understate the costs of basic needs and

therefore lead to underestimation of the level and

proportion of the US population at risk for health

issues associated with poverty comes from several

sources. The National Research Council (NRC) of

the National Academy of Science conducted a review

of the US poverty measures in the mid-1990s, finding

them deficient in several respects and recommending

a number of changes. The overall effect of implemen-

tation of the NRC recommendations would be to

increase the number and proportion of people identi-

fied as living in poverty.

0039Another relevant set of studies attempts to deter-

mine the minimum income levels actually needed by

different size and type of families in different geo-

graphic locations within the USA for basic economic

self-sufficiency. These studies use actual current data

on costs of basic goods and services in different states

and regions together with existing taxes and tax

credits to estimate actual minimum economic self-

sufficiency income levels. Generally, the resulting

self-sufficiency income estimates fall above 200% of

the federal poverty thresholds.

0040The food-insecurity prevalence estimates summar-

ized in Table 1 for 2000 also provide useful informa-

tion regarding the relevance of the current poverty

thresholds. Data in Table 1 show that, at income

levels at or above 185% of poverty, the prevalence

of food insecurity and hunger is quite low, with over-

all food insecurity at 4.9%, food insecurity without

hunger at 3.9%, and only 1.1% of households experi-

encing hunger (numbers do not sum due to rounding).

Households with incomes equal to, or greater than,

130% but less than 185% of poverty have higher rates

of food insecurity, with 18.4% food insecure overall,

14.5% without hunger, and 3.9% with hunger.

0041The numbers and proportions of people in poverty

by selected household characteristics are shown in

Table 2. These data reflect similar patterns to those

for food insecurity shown in Table 1. People living in

households with children have higher poverty rates

than those in households without children, people in

households headed by single females have higher

poverty rates than those in households headed by

married couples, and people in Black and Hispanic

households have higher rates of poverty than non-

Hispanic Whites.

0042Table 3 contains state-level average poverty rates

and food-insecurity prevalence rates for the years

1996–1998 from the CPS. Calculation of the Pearson

correlation coefficient for these two measures indi-

cates a strong positive relationship between poverty

FOOD SECURITY 2693

and food insecurity (R ¼0.72). The resulting coeffi-

cient of determination for poverty and food insecurity

is also sizeable (R

2

¼0.51), indicating that approxi-

mately 51% of the variance in food insecurity among

states is explained by poverty.

Social Safety-net Programs

0043 Public policies and programs that provide support for

low-income individuals and families are increasingly

important in reducing and preventing food insecurity,

especially in urban areas. One of fifteen food assist-

ance programs funded and overseen by the federal

government, the Food Stamp Program (FSP) is the

nation’s largest nutrition safety-net program for

low-income people. Gross income eligibility for re-

ceipt of food stamps is 130% of poverty, making most

households with incomes below this level, and that

fulfill other eligibility requirements, able to receive

food assistance if they apply.

0044 However, the Personal Responsibility and Work

Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996,

the most recent US welfare reform law, changed sev-

eral aspects of the FSP, making many legal permanent

residents and single adults without children ineligible.

In addition, provisions of PRWORA aimed at

diverting or deterring applications for cash assistance,

and sundry new rules aimed at enforcing compliance

with behavioral expectations, appear to have led

many households eligible for food stamps not to

apply. There is evidence that the magnitude and ex-

tensiveness of changes made by PRWORA may have

created so much uncertainty about the new welfare

system that many current and potential recipients are

frequently uninformed or misinformed regarding

their eligibility and other critical aspects of program

operation.

0045PRWORA eliminated entitlement status from cash

assistance to families with dependent children

(AFDC) and replaced it with Temporary Assistance

for Needy Families (TANF), while transforming fed-

eral funding for AFDC/TANF into a system of block

grants to states. New rules and regulations under

PRWORA enabled states to place additional restric-

tions on eligibility and impose a wide range of new

behavioral requirements for continued receipt of aid,

along with punitive sanctions for failure to comply

with these requirements. The new law placed an

overall 5-year limit on the receipt of benefits for

most recipients and transferred primary responsibil-

ities for design, implementation, and oversight of

tbl0002 Table 2 Number and percentage of persons in poverty by selected characteristics: 2000

Characteristics Totalin population/group (1000s) Numberinpoverty (1000s) Percentage in poverty

All persons 275 924 31 054 11.3

Children under 18 71 936 11 553 16.1

Ages 18–64 years 171 010 16 142 9.4

Ages 65 years and older 32 978 3 359 10.2

Type of household

Married-couple families 180 272 10 138 5.6

Related children under 18 years 51 926 4 219 8.1

Related children under 6 years 17 426 1 490 8.6

Female head, no spouse 37 422 10 425 27.9

Related children under 18 years 15 382 6 116 39.8

Related children under 6 years 4 655 2 196 47.2

Women living alone 16 307 3 159 19.4

Men living alone 11 571 1 592 13.8

Race/ethnicity

White (non-Hispanic) 193 917 14 532 7.5

Black 35 752 7 862 22.0

Hispanic 33 716 7 153 21.2

Ratio of income to poverty

Under 0.50 275 924 12 099 4.4

Under 1.00 275 924 31 054 11.3

Under 1.30 275 924 45 843 16.6

a

Under 1.85 275 924 73 329 26.6

Under 2.00 275 924 80 535 29.2

Area of residence

In metropolitan areas 224 349 24 136 10.8

In central cities 80 144 12 906 16.1

Not in central cities 144 205 11 230 7.8

Outside metropolitan areas 51 575 6 919 13.4

a

Estimates in this row were obtained by linear interpolation between 1.25 and 1.50.

From Dalaker JD (2001) Poverty in the United States: 2000. US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, Series P60-214 Washington, DC: US GPO.

2694 FOOD SECURITY

welfare programs to state and local governments.

These changes allowed states wide latitude in impos-

ing even stricter time limits and other eligibility

requirements.

0046A primary goal of welfare reform was to move

recipients off the case loads and into jobs. In many

states, innovative approaches to delivery of services in

support of this transition from welfare to work

emerged. As a result of the welfare reform changes

and growth in the economy during the 1990s, between

1994 and 1999, the national AFDC/TANF caseload

declined by 8.0 million recipients (56.0%). Over the

same period, the average national monthly FSP case-

load declined by 9.3 million recipients (33.8%).

0047Several studies have documented extensive declines

in participation in the FSP during the 1990s and show

that a large part of the decline was due to growth in

the economy and falling unemployment raising the

incomes of previously eligible households above the

income eligibility level. However, these and other

studies also show that a majority (56%) of the decline

in FSP caseloads resulted from a decline in the partici-

pation rates, the proportion of eligible households

participating.

0048Food-security prevalence data from the USDA

show that from 1995 to 1999, even though food

insecurity declined overall, among households with

incomes at or below 130% of the poverty level (the

gross income eligibility cutoff for the FSP), food inse-

curity actually increased from 23 to 28%. This indi-

cates that many low-income households stopped

receiving food stamps, or did not apply for them,

even though they were food-insecure and felt they

needed more food. In addition, studies of the private

emergency food-assistance system over the same

period indicate that many households leaving the

TANF and FSP caseloads are relying more heavily

on food from private emergency sources such as

food pantries, soup kitchens, and shelters.

Summary and Conclusion

0049Poverty-related food insecurity and hunger are real-

ities experienced by millions of US households. They

are associated with both overnutrition and undernu-

trition but are not congruent with malnutrition. Food

insecurity impacts human development and health

throughout the life-cycle, but can be particularly

harmful during critical or vulnerable stages early

and late in life. Understanding the causes and con-

sequences of food insecurity and knowing how to

identify and measure them can improve the quality

and effectiveness of social policies, and facilitate

prevention and reduction of many kinds of health

problems.

tbl0003 Table 3 Average percentage in poverty and food-insecure by

state: 1996–98

State Average percentage

in poverty

1996^98

Average percentage

food-insecure

1996^98

Difference

1996^98

US 13.2 9.7 3.5

AK 8.8 7.6 1.2

AL 14.7 11.3 3.4

AR 17.2 12.6 4.6

AZ 18.1 12.8 5.3

CA 16.3 11.4 4.9

CO 9.3 8.8 0.5

CT 9.9 8.8 1.1

DC 22.7 11.1 11.6

DE 9.5 6.8 2.7

FL 13.9 11.5 2.4

GA 14.3 9.7 4.6

HI 12.3 10.4 1.9

IA 9.4 7.0 2.4

ID 13.2 10.1 3.1

IL 11.1 8.2 2.9

IN 8.6 7.8 0.8

KS 10.1 9.9 0.2

KY 15.5 8.4 7.1

LA 18.6 12.8 5.8

MA 10.3 6.3 4.0

MD 8.6 7.1 1.5

ME 10.6 8.7 1.9

MI 10.8 8.1 2.7

MN 9.9 6.9 3.0

MO 10.4 8.6 1.8

MS 18.3 14.0 4.3

MT 16.4 10.2 6.2

NC 12.5 8.8 3.7

ND 13.2 4.6 8.6

NE 10.8 7.5 3.3

NH 8.4 7.4 1.0

NJ 9.0 7.3 1.7

NM 22.4 15.1 7.3

NV 9.9 8.6 1.3

NY 16.6 10.0 6.6

OH 11.6 8.5 3.1

OK 14.8 11.9 2.9

OR 12.8 12.6 0.2

PA 11.3 7.1 4.2

RI 11.8 8.7 3.1

SC 13.3 10.2 3.1

SD 13.0 6.4 6.6

TN 14.5 10.9 3.6

TX 16.1 12.9 3.2

UT 8.5 8.8 0.3

VA 11.3 8.3 3.0

VT 10.6 7.7 2.9

WA 10.0 11.9 1.9

WI 8.6 7.2 1.4

WV 17.6 9.0 8.6

WY 12.0 9.0 3.0

From Nord M, Jemison K and Bickel G (1999) Prevalence of Food Insecurity

and Hunger, by State 1996^98. USDA/ERS, Food Assistance and Nutrition

Research Report No. 2, September 1999 and Dalaker J (1999) Poverty in the

United States: 1998. US Census Bureau Current Population Reports, Series

P60-207, US GPO, Washington, DC, September 1999.

FOOD SECURITY 2695

0050 Numerous public policies and programs exist to

ameliorate and prevent poverty-related food insecur-

ity and hunger. However, the resources to support

them ebb and flow with the politics of annual state

and federal budgetary cycles. Support and need for

these social safety-net programs also vary with

business cycles. Unfortunately, need often expands

as support shrinks along with employment and gov-

ernment revenues during recessions, and shrinks as

support expands along with employment and govern-

ment revenues during expansions.

0051 In March 2001, the US economy reached the peak

of an unprecedented 10-year period of expansion and

has been in recession for more than a year. It is worth

noting that the record expansionary period from

March 1991 to March 2001 began with an un-

employment rate at 6.8%, and 8.6 million workers

unemployed. During the 10-year expansion, the un-

employment rate remained above 6% until Septem-

ber 1994, continued above 5% until April 1997, only

dipped below 4% for the two months of September

and October 2000, and remained at or above 4%

through the peak month of March 2001, when it

stood at 4.3% with 6.1 million workers unemployed.

0052 This strongly suggests that the ‘full employment’

unemployment rate (i.e., the lowest unemployment

rate that the US economy can reach and sustain for

any appreciable length of time) is probably not lower

than 4%, and may be even higher (e.g., 5%). The

importance of this is that under known conditions,

unemployment is not likely to fall below 4% for very

long (if at all), and poverty, food insecurity, and

hunger are not likely to disappear altogether, even

during economic booms. A clear understanding of

the causes and consequences of poverty-related food

insecurity and hunger, and of effective policies to

reduce and prevent them is critical to the public

well-being. Such understanding is more attainable

now that valid and reliable food security measures

are available and being used.

See also: Hunger; Malnutrition: The Problem of

Malnutrition; Malnutrition in Developed Countries

Further Reading

Anderson SA (ed) (1990) Core indicators of nutritional

state for difficult-to-sample populations. Life Sciences

Research Office, Federation of American Societies for

Experimental Biology. J Nutr 120(11S): 1557–1600.

Bickel G, Andrews M and Klein B (1996) Measuring Food

Security in the United States: A Supplement to the CPS.

In: Hall D and Stavrianos M (eds) Nutrition and Food

Security in the Food Stamp Program. USDA/FCS/OAE,

Alexandria, VA.

Cahalan T, Genser J, Kissmer C, Macaluso TF and Olander

C (2001) The Decline in Food Stamp Participation: A

Report to Congress. USDA/FNS, Report No. FSP-01-

WEL.

Dietz WH (1995) Does hunger cause obesity? Pediatrics

95(5): 766–767.

Hamilton WL, Cook JT, Thompson WW, Buron LF, Fron-

gillo EA, Olson CM and Wehler CA (1997) Household

Food Security in the United States in 1995: Summary

Report of the Food Security Measurement Project.

USDA/FCS/OAE: Alexandria, VA.

Hamilton WL, Cook JT, Thompson WW, Buron LF, Fron-

gillo EA, Olson CM and Wehler CA (1997) Household

Food Security in the United States in 1995: Technical

Report of the Food Security Measurement Project.

USDA/FCS/OAE, Alexandria, VA.

Kim M, Ohls J and Cohen R (2001) Hunger in America

2001: National Report Prepared for America’s Second

Harvest. Chicago, IL and Princeton, NJ.

Nord M, Jemison K and Bickel G (1999) Measuring Food

Security in the United States: Prevalence of Food Inse-

curity and Hunger by State, 1996–1998. USDA/ERS

Food Assistance and Nutrition Research Report No. 2,

Washington, DC.

Nord M, Kabbani N, Tiehen L, Andrews M, Bickel G and

Carlson S (2002) Measuring Food Security in the United

States: Household Food Security in the United States,

2000. USDA/ERS Food Assistance and Nutrition Re-

search Report No. 21. Washington, DC.

Olson CM (1999) Nutrition and health outcomes associ-

ated with food insecurity and hunger. J Nutr 129: 521S–

524S.

Radimer K, Olson CM, Greene JC, Campbell CC and

Habicht JP (1992) Understanding hunger and develop-

ing indicators to assess it in women and children. J Nut

Educ 24(S): 36S–44S.

Read MA, Frence S and Cunningham K (1994) The role of

the gut in regulating food intake in man. Nutr Rev 52:

1–10.

Rogers BL, Brown JL and Cook JT (1994) Unifying the

poverty line: a critique of maintaining lower poverty

standards for the elderly. Journal of Aging and Social

Policy 6(1/2): 143–166.

Townsend MS, Peerson J, Love B, Achterberg C and

Murphy SP (2001) Food insecurity is positively related

to overweight in women. J Nutr 131: 1738–1745.

Wehler CA, Scott R and Anderson J (1992) The Community

Childhood Hunger Identification Project: A Model of

Domestic Hunger – Demonstration Project in Seattle,

Wahsington. J Nut Educ 24(S): 29S–35S.

2696 FOOD SECURITY

Foreign Bodies See Adulteration of Foods: History and Occurrence; Detection; Contamination of Food

FREEZE-DRYING

Contents

The Basic Process

Structural and Flavor (Flavour) Changes

The Basic Process

J D Mellor and G A Bell, formerly of CSIRO, North

Ryde, Australia

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Introduction

0001 Freeze drying, which is also known as lyophilization,

is the process of removing water from a product by

freezing it then subliming the ice to vapor. Sublim-

ation is a physical phenomenon by which solid ice is

converted directly into vapor without it passing

through the liquid state. Removing water from food,

by sublimation, protects the material against loss of

important constituents and against chemical reac-

tions that are associated with withdrawing or vapor-

izing liquid water.

0002 Freeze drying occurs in nature through the com-

bined effects of solar heating, cold dry winds, and

rarified atmospheres of mountainous regions. These

natural conditions are used to produce freeze-dried

‘stock’ fish in Norway and a dried potato product

called chuno in Peru. Freeze drying is also used in a

peculiar way by the North American red squirrel

which is known to spread pieces of food in the forks

of trees at the beginning of winter, thereby freeze

drying its food supply.

0003 Dried foods offer convenience of storage and trans-

port derived from their long shelf-life and low weight.

Freeze-dried foods enjoy these properties and are

generally of higher quality than products dried by

other processes. As a result, freeze-dried foods tend

to be preferred in culinary arts over other dried

products. (See Drying: Theory of Air-drying.)

0004 Loss of water vapor from the product depends

mainly on two influences: heat available to the

product; and the vapor pressure differential across

the subliming interface between frozen and dry

layers. In practice, these two factors are often com-

promised in the interest of production economics.

Despite widespread use of freeze drying in biological

laboratories and in drug and vaccine production, the

development of freeze drying as a food technology

has been fraught with cost and scale-up problems.

Its application to large-scale food processing has

been limited to a small number of products including

instant coffee, soup mixes, military rations, and

herbs.

0005The final quality of a freeze-dried product can be

determined by optimizing conditions in three steps in

the process: the primary phase, the drying phase, and

the supplementary phase.

Primary Phase

0006Before freezing, certain preparations are necessary,

depending on the product in question. For example,

slicing, dicing, and mincing will alter the surface area

of the product from where drying can proceed,

blanching the product will alter its enzymatic proper-

ties, while cooking causes reductions in the free and

bound water in the product. These preparations will

also tend to enhance heat transfer in the product

during the drying phase and, therefore, the speed

and quality of the result. (See Freezing: Operations.)

0007The water content of a food comprises both free

water and water bound to proteins. When a food

freezes, a large portion of the free water becomes

frozen and is disposable as ice for sublimation. The

disposable proportion varies from product to prod-

uct, and is determined by the final temperature ar-

rived at after freezing. Water remaining in the product

after drying may promote microbes and dete-

rioration. Therefore, the temperature to which the

FREEZE-DRYING/The Basic Process 2697