Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

0004 Despite a great deal of individual variability in

the perception of these sensations, hunger can be

associated with clear symptoms; it is partly through

reference to these that people can make judgements

about the intensity of their hunger experience. The

measurement of hunger, desire to eat, or urge to eat is

most commonly conducted using fixed-point or

visual-analog scales. Respectively, these require the

subject to choose a number from a scale or a point

on a line that corresponds to their current state of

hunger. Careful presentation of these scales to people

who understand what is being asked of them will

yield meaningful information. More importantly,

quantifying the subjective experience of hunger

makes it a state, which is amenable to scientific inves-

tigation. Consequently, hunger can be described

qualitatively in terms of the sensations with which it

is associated, and it can also be measured quantita-

tively. This means that the significance of hunger can

be understood through its structure and by its inten-

sity. In recent years, the visual analog scale technique

has been incorporated into the screen of a small hand-

held computer. This device, called the Electronic

Appetite Rating System (EARS) provides a conveni-

ent and user-friendly way of monitoring hunger

during the course of a day.

Hunger, Eating Patterns and the Satiating

Power of Food

0005 If hunger is the feeling that reminds us to seek food,

then the consumption of food is the action that di-

minishes hunger and keeps it suppressed for a certain

period of time, perhaps until the next meal or snack.

The capacity of food to reduce the experience of

hunger is called the satiating power or satiating

efficiency. This power is achieved by certain proper-

ties of the food itself engaging with various physio-

logical and biochemical mechanisms within the body

that are concerned with the processing of food once it

has been ingested. The satiating power of food there-

fore results from a variety of biological processes and

is an important factor in the control of hunger. Some

foods have a greater capacity to maintain suppression

over hunger than other foods. (See Satiety and Appe-

tite: Food, Nutrition, and Appetite.)

0006 How is hunger related to the overall control of

human appetite and food consumption? The feeling

of hunger is an important component in determining

what we eat, how much we eat, and when we eat.

However, it must be seen in a context of social and

physiological variables. On the one hand, eating

patterns are maintained by certain enduring habits,

attitudes, and opinions about the value and suitability

of foods and overall liking for them. These factors,

derived from the cultural ethos, largely determine the

range of foods that will be consumed, and sometimes

the timing of consumption. The intensity of hunger

experienced may also be determined, in part, by the

culturally approved appropriateness of this feeling.

0007On the other hand, normal hunger is more import-

antly associated with the events surrounding meals –

so-called periprandial circumstances – and the

periods between meals. Thus, hunger can be con-

sidered to arise from an interaction between the

physiological requirements of the body for food

(or particular nutrients) and the capacity of food to

satisfy these requirements. Hunger will therefore be

successively stimulated and suppressed, giving rise to

a diurnal rhythm. This rhythm, and the relationship

between hunger and eating, may be modulated by

certain social factors (e.g., distressing psychological

events) or interrupted by some disease states.

Hunger and the Satiety Cascade

0008When food consumption reduces hunger and inhibits

further eating, two processes are involved. For tech-

nical precision and conceptual clarity, it is useful to

describe the distinction between satiation and satiety.

Both terms may be assigned workable operational

definitions (i.e., definitions that depend upon meas-

urable events). Satiation can be regarded as the pro-

cess that develops during the course of eating and

eventually brings a period of eating to an end.

Accordingly, satiation can be defined by the measured

size of the eating episode (volume or weight of food,

or value of the energy content). Hunger declines as

satiation develops and usually reaches its lowest point

at the end of a meal. Satiety is defined as the state of

inhibition over further eating that follows the end

of an eating episode and arises from the consequences

of food ingestion. The intensity of satiety can be

measured by the duration of time elapsing until eating

is recommenced, or by the amount consumed at the

next meal. The strength of satiety is also measured by

the duration of the suppression of hunger. As satiety

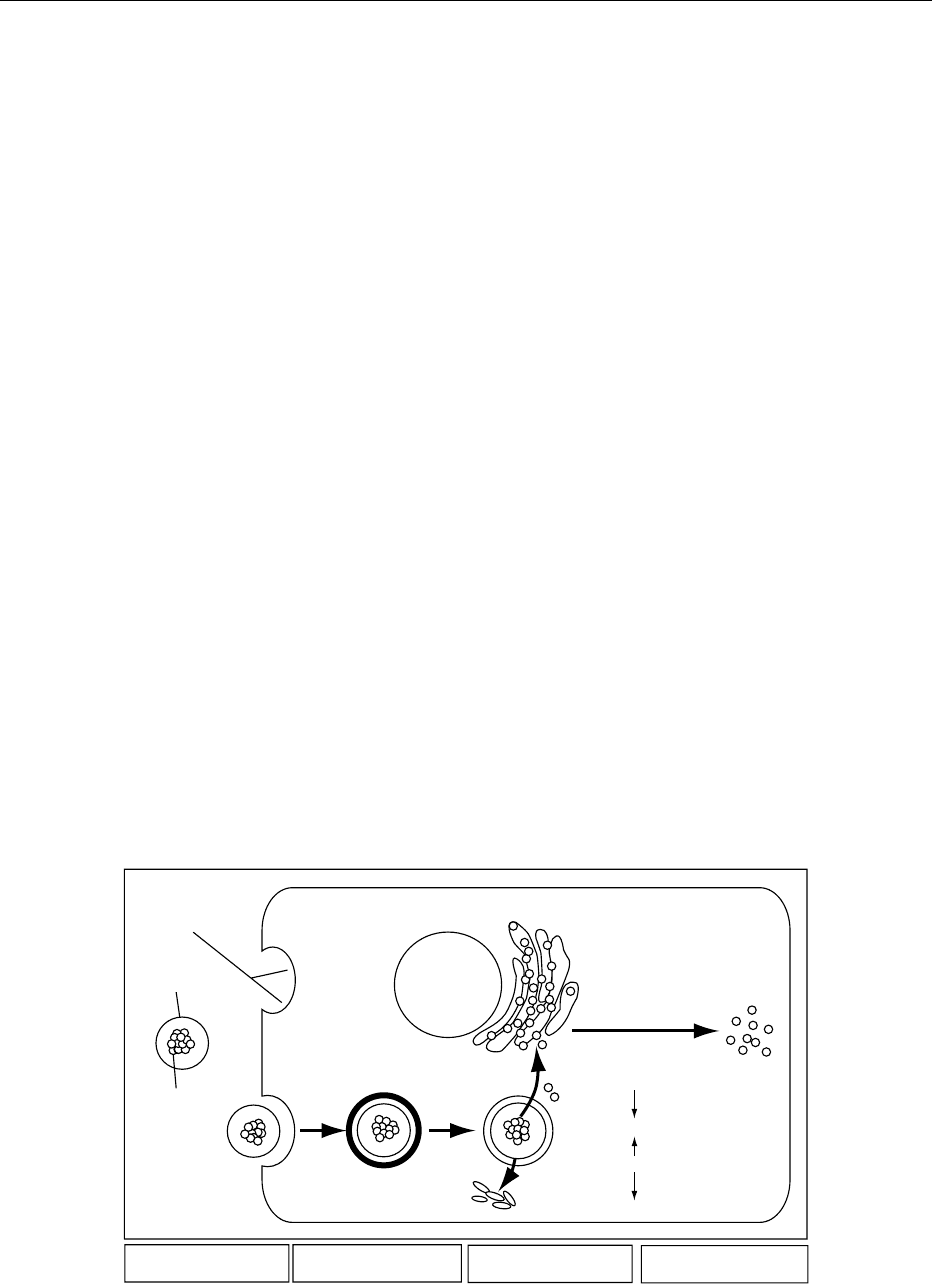

weakens, so hunger is restored. Figure 1 indicates the

changes that occur in the rating of hunger during a

meal (as satiation develops) and following a meal (as

satiety evolves). It can be seen that the measurement

of hunger is an important index of the degree of

satiation and satiety.

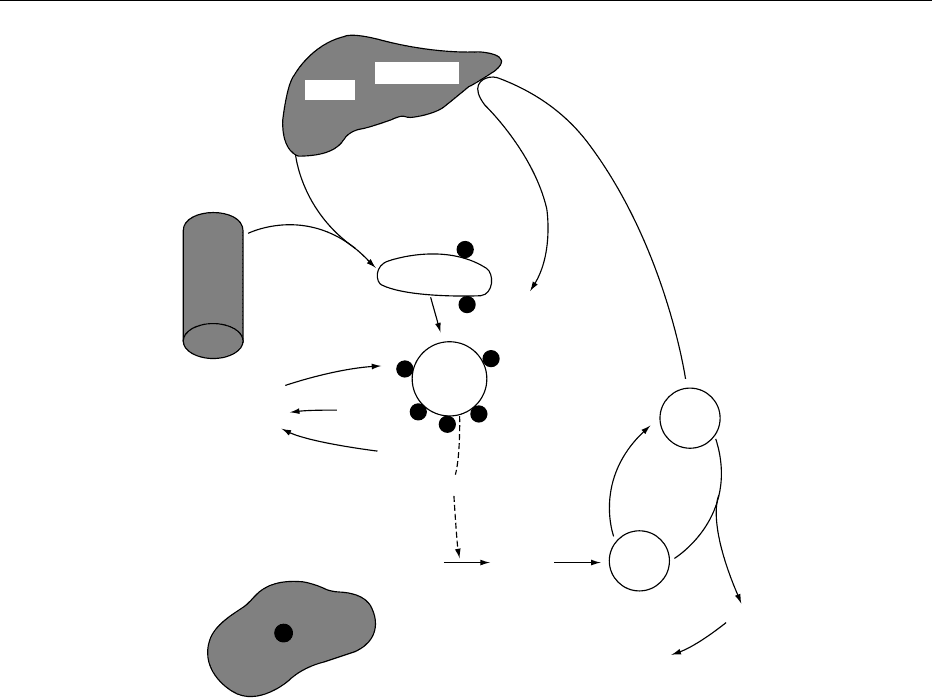

0009In the view of some researchers, satiation and

satiety can be referred to as intrameal satiety and

intermeal satiety, respectively. What mechanisms are

responsible for these processes? It is clear that the

mechanisms involved in reducing hunger and in

maintaining the suppression over hunger range from

those that occur when food is initially sensed, to the

HUNGER 3179

effects of metabolites on bodily tissues following

digestion and absorption (across the wall of the intes-

tine and into the bloodstream). By definition, satiety

is not an instantaneous event but occurs over a

considerable time period; it is therefore useful to dis-

tinguish different phases of satiety, which can be

associated with different mechanisms. This concept

is illustrated in Figure 2.

0010 Four mediating processes are identified: sensory,

cognitive, postingestive, and postabsorptive. These

maintain inhibition over hunger (and eating) during

the early and late phases of satiety. Sensory effects are

generated through the smell, taste, temperature, and

texture of food, and it is likely that these factors

inhibit eating in the very short term. Cognitive effects

represent the beliefs held about the properties of

foods, and these factors may help to inhibit hunger

in the short term. The category identified as post-

ingestive processes includes a number of possible

actions, including gastric distension and rate of gas-

tric emptying, the release of hormones such as chole-

cystokinin, and the stimulation of physicochemically

specific receptors along the gastrointestinal tract.

The postabsorptive phase of satiety includes those

mechanisms arising from the action of metabolites

after absorption across the intestine and into the

blood system. This category embraces the action of

chemicals such as glucose and amino acids, which

may act directly on the brain after crossing the

blood–brain barrier or may influence the brain

indirectly via neural inputs following stimulation

of peripheral chemoreceptors. The most important

suppression and subsequent control of hunger is

brought about by postingestive and postabsorptive

mediating processes.

Conditioned Hunger

0011It should be kept in mind that the psychobiological

system for appetite control has the capacity to

learn, i.e., to form associations between the sensory

and postabsorptive characteristics of foods. This

means that it will be useful to distinguish between

the unconditioned effects of foods, i.e., those in

which the natural biological consequences of food

processing in the gut are reflected in satiety, and the

conditioned effects that come into play owing to

the links developed between sensory aspects of

food – particularly those that are tasted – and later

metabolic effects generated by the same food. The

sensory characteristics (or cues) therefore come

to predict the impact that the food will later

exert. Consequently, these cues can suppress hunger

according to their relationship with subsequent

physiological events. However, the potency of this

mechanism depends upon the stability and reliability

of the relationship between tastes (sensory cures) and

physiological effects (metabolic consequences) of

food. When there is distortion or random variation

between sensory characteristics and nutritional prop-

erties, the conditioned control of hunger is weakened

or lost. Therefore, learned hunger will not be an

important factor when the food supply contains

many foods with identical tastes but differing meta-

bolic properties.

Is Hunger the Cause of Eating?

0012In searching for an answer to this question, we can

begin by considering whether hunger is a necessary or

a sufficient condition for eating to occur. Since hunger

may be present, but a person may volitionally prevent

123

Time of rating (h)

Mean rating of hunger (mm)

DinnerLunch

0

20

40

60

80

100

0.5 0.75 1

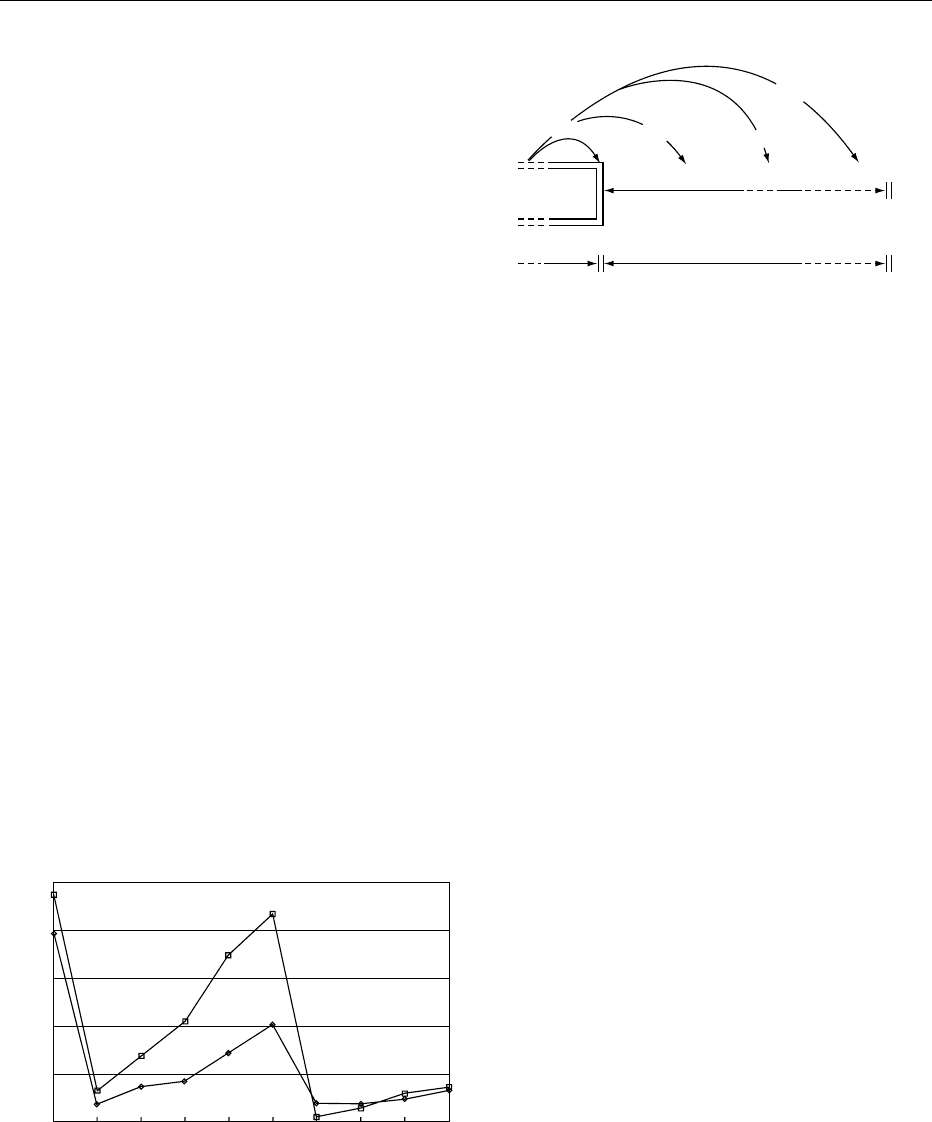

fig0001 Figure 1 Profiles of the ratings of the subjective experience in

two groups of subjects, one of which ate a large lunch (^) and the

other a lunch 50% smaller (h). Each meal suppressed hunger,

but the intensity of hunger recovered more rapidly following the

small meal. Four hours after the first meal, subjects were given

another meal to eat (dinner), and hunger was again suppressed.

Hunger ratings reflect the amount of food consumed and the

timing of meals.

Mediating processes

Postabsorptive

Postingestive

LateEarly

Cognitive

Sensory

Food

SatietySatiation

fig0002Figure 2 Satiety cascade. This diagram represents the medi-

ating processes, arising from food consumption, that influence

the feeling of hunger and determine the satiating efficiency of the

food.

3180 HUNGER

themselves from eating (e.g., someone undertaking a

fast for moral or political conviction), hunger is not a

sufficient condition. Occasions can also be imagined

where a person would eat, if food was particularly

tempting, where no hunger was being experienced.

0013 Therefore, it appears that hunger is neither a suffi-

cient nor a necessary condition for eating, i.e., the

relationship between hunger and eating is not based

on biological inevitability. However, under many

circumstances, there is a synchronous relationship

between the pattern of food intake and the rhythmic

oscillation of hunger. Moreover, the results of many

studies confirm the strong relationship between the

intensity of experienced hunger sensations and the

amount of food consumed. For example, when

hunger and eating have been monitored continually,

it has been reported that ‘the correlation using hunger

ratings and intake during the same hour of the day

was r ¼< 0.5 (P < 0.02). That is, hunger ratings at the

start of each hour were correlated with reported

intake in the hour following each hunger rating.’ In

addition, significant correlations have been found

between hunger ratings prior to a lunch and subse-

quent intake of fat, protein, and energy, indicating

that these measures of subjective hunger provide a

valid index of actual food intake. The correlations

found in almost all studies indicate that, in many

circumstances, the measured intensity of hunger reli-

ably predicts the amount of food that will be con-

sumed. This fact has led to the proposal that there is a

causal connection between hunger and the size of a

following meal. Table 1 shows measured correlations

between hunger, food intake, and related subjective

experiences.

0014 These observations provide the basis for a working

conceptualization. The correlations are sufficiently

strong and reliable to allow us to act as if hunger is

a cause of eating. In actuality, it is probably the case

that common physiological mechanisms induce

changes both in hunger and in the eating response.

Therefore, we can consider an appetite control system

in which hunger, eating, and physiological mechan-

isms (of the satiety cascade) are coupled together.

However, the coupling is not perfect, and there will

be circumstances where, for example, a physiological

treatment will change eating but not hunger. In other

words, uncoupling can occur. However, when this

happens, e.g., under certain conditions of fasting or

in disordered eating, the mechanisms responsible can

provide useful information about the role of hunger

in the overall control of appetite. It should be noted

that, although a number of individuals often deny

that sensations of hunger are related to when eating

occurs, under scientifically controlled conditions,

there is usually a strong relationship between hunger

and eating. (See Sensory Evaluation: Sensory Charac-

teristics of Human Foods.)

Disorders of Hunger

0015The clinical eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and

bulimia nervosa, are commonly believed to encom-

pass major disturbances of hunger. Yet the role that

hunger may play is not entirely clear. Contrary to the

literal meaning of the term, ‘anorexia’ is not experi-

enced as a loss of appetite. Rather, clinicians recog-

nize that anorexics may endure intense bouts of

hunger during their self-imposed restricted eating.

For some, their strength in resisting intense episodes

of hunger provides a feeling of self-mastery and con-

trol that is absent in most other areas of their lives.

Anorexics therefore overcome their feelings of

hunger. However, there is some evidence to suggest

that in conditions of total starvation, hunger may

become temporarily diminished. However, once

eating is recommenced, hunger may return rapidly

and with extreme intensity. (See Anorexia Nervosa.)

0016Like anorexia, bulimia finds its literal meaning in

an altered state of hunger –‘ox hunger.’ But again, the

term is imprecise. Close analysis of the physiological

states, which characteristically provide an eating

binge, show hunger to be lower than it is prior to a

normal meal. In addition, while the urge to eat may

be strong during a binge, the large amount of food

consumed implies some defect in satiation rather than

in hunger. Research that has monitored hunger in

eating disordered patients during a simple meal de-

scribes both great individual variability in the hunger

experience and examples of extreme disorganization.

In some cases, hunger appears quite dissociated from

the circumstance of eating. It is likely that a stable

tbl0001 Table 1 Intercorrelations between ratings of hunger, other

subjective sensations, and measure of food intake observed in

experimental studies in lean and obese subjects (all correlation

coefficients shown are statistically significant)

Food intake

(kcal)

Hunger Desire to

eat

Fullness

Lean subjects

Hunger 0.75

Desire to eat 0.77 0.96

Fullness 0.69 0.93 0.97

Prospective

consumption

0.80 0.97 0.95 0.91

Obese subjects

Hunger 0.65

Desire to eat 0.68 0.96

Fullness 0.54 0.75 0.77

Prospective

consumption

0.66 0.88 0.89 0.78

HUNGER 3181

eating pattern is necessary in order to normalize the

experience of hunger, and this may take a long time to

establish. (See Bulimia Nervosa.)

0017 Obesity is another condition in which hunger is

often assumed to be impaired. In seeking a cause for

excess weight, overeating has been regarded as being

caused by high levels of hunger. Although it is now

accepted that, on average, obese individuals have a

higher energy intake than lean people, this cannot

necessarily be assigned to higher levels of hunger. It

appears that the experience of hunger is similar in

lean and in most obese subjects. Studies suggest that

in general, there is no gross fault in the obese food-

intake regulation system. Any ‘fault’ is likely to be

subtle. An indication of this comes from the response

to a reduced-energy diet. Obese people, in common

with those of normal weight, respond to a reduction

in their energy intake by increased feelings of hunger.

Alternatively, anorectic drugs or nutrients that sup-

press hunger appear to do so similarly in obese and

lean people. Attempts to lose weight by dieting may

fail because of an inability to manage hunger. How-

ever, it should be recognized that for some very obese

people, the sensation of hunger occurs in an eccentric

fashion and is not related to periods of eating. Some

people can report strong feelings of hunger and full-

ness simultaneously, (See Obesity: Etiology and

Diagnosis.)

Hunger and Health

0018 The analysis of the phenomenon of hunger, the influ-

encing mechanisms, and its relationship to the regu-

lation of food intake indicate that hunger is a potent

factor in the maintenance of general health. In

societies where food is plentiful, the relatively mild

experiences of hunger play a biological useful role in

the orderly regulation of eating patterns. When food

is scarce, the power of hunger can drive people to

desperate deeds. In certain disease states, a very in-

tense hunger or its absence can indicate the severity of

the underlying pathology. In other extreme circum-

stances, hunger is forced out of synchrony with

physiological mechanisms, eating behavior, or both.

This labile or disregulated hunger reflects the path-

ology of the appetite system. The drive to eat, identi-

fied as hunger, is therefore a significant marker of

health. If the mechanisms underlying this drive are

compromised, hunger can become difficult to control.

(See Malnutrition: The Problem of Malnutrition.)

See also: Anorexia Nervosa; Bulimia Nervosa;

Malnutrition: The Problem of Malnutrition; Obesity:

Etiology and Diagnosis; Satiety and Appetite: Food,

Nutrition, and Appetite; Sensory Evaluation: Sensory

Characteristics of Human Foods

Further Reading

Blundell JE and Rogers PJ (1991) Hunger, hedonics, and the

control of satiation and satiety. In: Friedman M and

Kare M (eds) Chemical Senses, vol. 4, pp. 127–148.

New York: Marcel Dekker.

De Castro JM and Elmore DK (1988) Subjective hunger

relationships with meal patterns in the spontaneous

feeding behaviour of humans: evidence for a causal

connection. Physiology and Behaviour 43: 159–165.

Hill AJ, Magson LD and Blundell JE (1984) Hunger and

palatability: tracking ratings of subjective experience

before, during and after the consumption of preferred

and less preferred food. Appetite 5: 361–371.

Keys A, Brozek J, Henscher A, Mickelson O and Taylor HL

(1950) The Biology of Human Starvation, vol. II. Min-

neapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

King NA, Lawton CL, Delargy HJ, Smith FC and Blundell

JE (1997) The electronic appetite rating system (EARS):

a portable computerised method for continuous auto-

mated monitoring of motivation to eat and mood. In:

Wellman PJ and Bartley GH (eds) Ingestive Behavior

Protocols, pp. 71–76. Society for the Study of Ingestive

Behavior.

Monello LF and Mayer J (1967) Hunger and satiety sensa-

tions in men, women, boys and girls. American Journal

of Clinical Nutrition 20: 253–261.

Hydrogenation See Vegetable Oils: Types and Properties; Oil Production and Processing; Composition

and Analysis; Dietary Importance

3182 HUNGER

Hygiene See Cleaning Procedures in the Factory: Types of Detergent; Types of Disinfectant; Overall

Approach; Modern Systems; Food Poisoning: Classification; Tracing Origins and Testing; Statistics; Economic

Implications; Contamination of Food; Escherichia coli: Occurrence; Detection; Food Poisoning; Occurrence and

Epidemiology of Species other than Escherichia coli; Food Poisoning by Species other than Escherichia coli;

Effluents from Food Processing: On-Site Processing of Waste; Microbiology of Treatment Processes; Disposal of

Waste Water; Composition and Analysis; Food Safety; Salmonella: Properties and Occurrence; Detection;

Salmonellosis; Saponins; Spoilage: Chemical and Enzymatic Spoilage; Bacterial Spoilage; Fungi in Food – An

Overview; Molds in Spoilage; Yeasts in Spoilage

Hyperglycemia (Hyperglycaemia) See Diabetes Mellitus: Etiology; Chemical Pathology;

Treatment and Management; Problems in Treatment; Secondary Complications

HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA)

J P D Reckless and J M Lawrence, University of

Bath, Combe Park, Bath, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Lipids

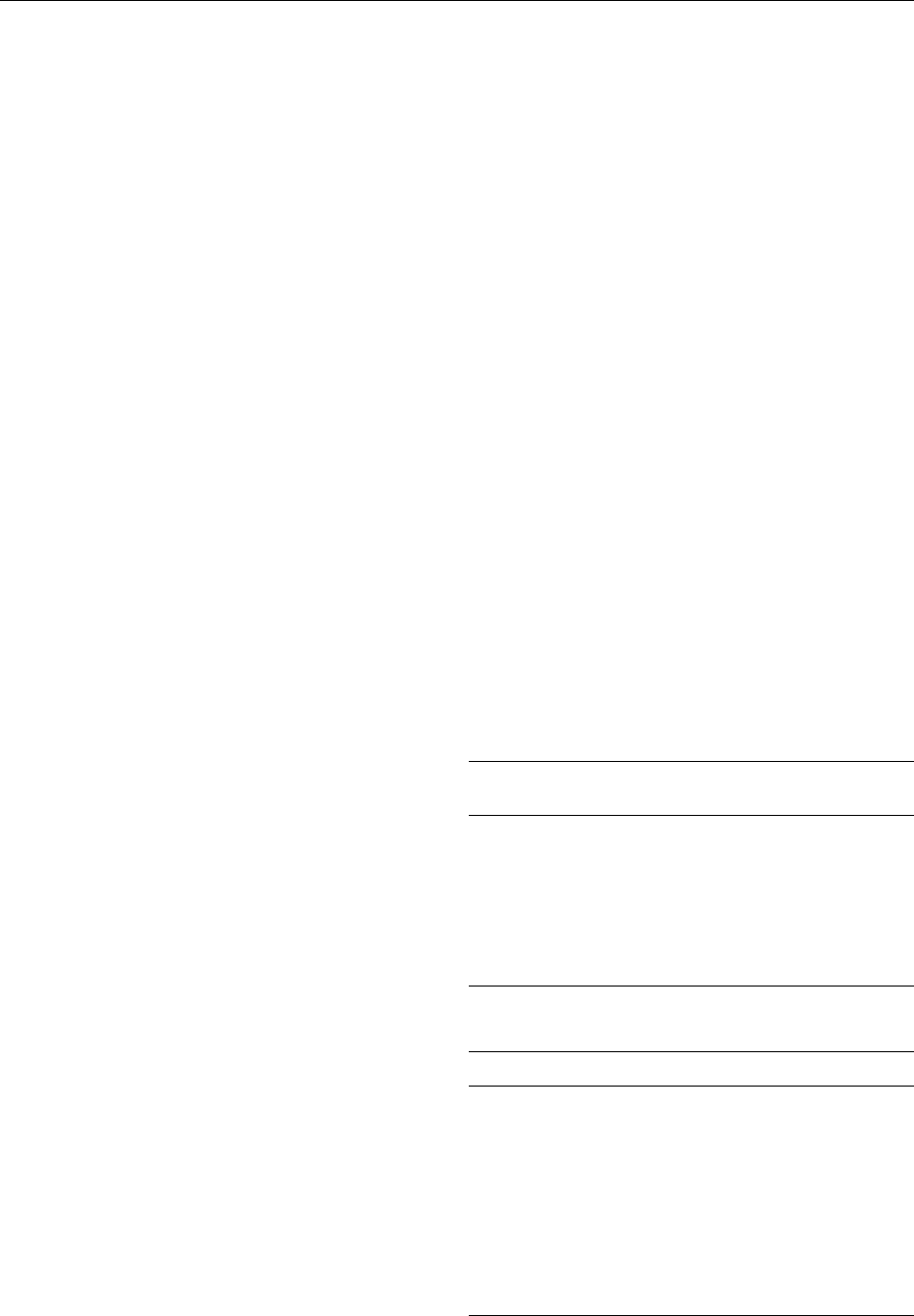

0001 Lipids are a heterogeneous group of substances that

play key roles in normal physiology. Two groups are

important – that where a main component includes

one or more fatty acids (such as triglycerides and

phospholipids) and that where the main component

is a steroid nucleus (such as cholesterol and steroid

hormones). Both groups are relatively insoluble in

water. The lipoprotein transport system carries these

hydrophobic compounds through the aqueous

medium of blood plasma to their site of use, in a

carefully regulated process. Lipoproteins consist of a

package of triglycerides, cholesterol (free and esteri-

fied), phospholipids, and apolipoproteins, with a

hydrophilic shell and a hydrophobic core (Figure 1).

The sites of synthesis are the gut and liver. The main

lipoproteins are high (HDL), low (LDL), and very

low (VLDL) density lipoproteins, and chylomicron7s.

Each has a different group of surface apolipo-

proteins, pivotal in determining the site, mechanism,

and speed of lipoprotein metabolism. The precise

molecular composition in each lipoprotein class

varies considerably.

0002 Hyperlipidemia means high levels of fats in the

blood, which may be physiological postprandially.

Pathological hyperlipidemia results from disordered

metabolism of the lipoproteins with either excess

production, altered clearance, or both. It is most

commonly multifactorial, involving both environ-

mental and intrinsic factors. Many genetic disorders

are now well recognized, causing various degrees of

hyperlipidemia or dyslipidemia (altered compos-

ition). Genetic studies have helped the understanding

of lipoprotein metabolism.

0003This review discusses normal lipoprotein metab-

olism, focusing on hyperlipidemia. As treating

hyperlipidemia has significant benefits in terms of

long-term health, having an understanding of normal

and abnormal lipoprotein metabolism is becoming

increasingly important.

The Intestine

0004Most dietary fats are triglycerides. These are hydro-

lyzed to mono- and diacylglycerols, nonesterified

fatty acids (NEFA) and glycerol by pancreatic or gut

lipases, and absorbed as mixed micelles in the small

intestine. In the intestinal cells, triglycerides are

reformed and interact with apolipoprotein B-48

(apoB48) to form chylomicrons. ApoB48 is the struc-

tural protein for chylomicrons. Each chylomicron

has one molecule of apoB48 and carries very large

numbers of triglyceride molecules. Precise numbers

vary widely, as does the chylomicron size, depending

on the diet (diameter 100–1000 nm). Chylomicrons

also accommodate any dietary cholesterol absorbed

HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA) 3183

(usually less than 0.5 g per day). They are released

into the intestinal lymphatics and subsequently into

the circulation via the thoracic duct.

Chylomicron Metabolism

0005 In the systemic circulation, chylomicrons receive

apolipoproteins additional to apoB48, particularly

apolipoprotein C (apoC) and apolipoprotein E

(apoE), from HDL (Figure 2). One apoC, apoC-II,

activates the enzyme lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and

facilitates ligand/enzyme binding between LPL and

chylomicrons. LPL is found widely on capillary endo-

thelial tissues of many organs including adipose tissue

and skeletal and cardiac muscle. The activated

enzyme hydrolyzes chylomicron-triglyceride, and

NEFA are released for uptake into tissues to be stored

or used as energy. As triglyceride is removed, the

relative concentration of cholesterol rises, and the

lipoprotein becomes smaller and denser. Excess sur-

face components of phospholipids, free cholesterol,

and apolipoproteins (but not the apoB48) are trans-

ferred to HDL. The efficiency of this process depends

on the activity of LPL and also the VLDL triglyceride

level in the circulation, as VLDL competes with chy-

lomicrons for LPL. The chylomicron remnant is re-

moved by liver receptor uptake, dependent on

multiple copies of apoE on the remnant surface.

This receptor is structurally related to the LDL recep-

tor (see Low Density Lipoprotein) as a member of

the LDL-supergene family and is named the LDL

receptor-related protein (LRP). The affinity of the

binding depends on the apoE phenotype. Chylomicron

remnant removal effectively delivers dietary choles-

terol and residual triglyceride to the liver.

Very Low Density Lipoproteins (VLDL)

0006VLDL are the other major triglyceride-rich lipopro-

teins (Figure 3). They carry endogenous, hepatically

CE

TG

free cholesterol

apoprotein

phospholipid

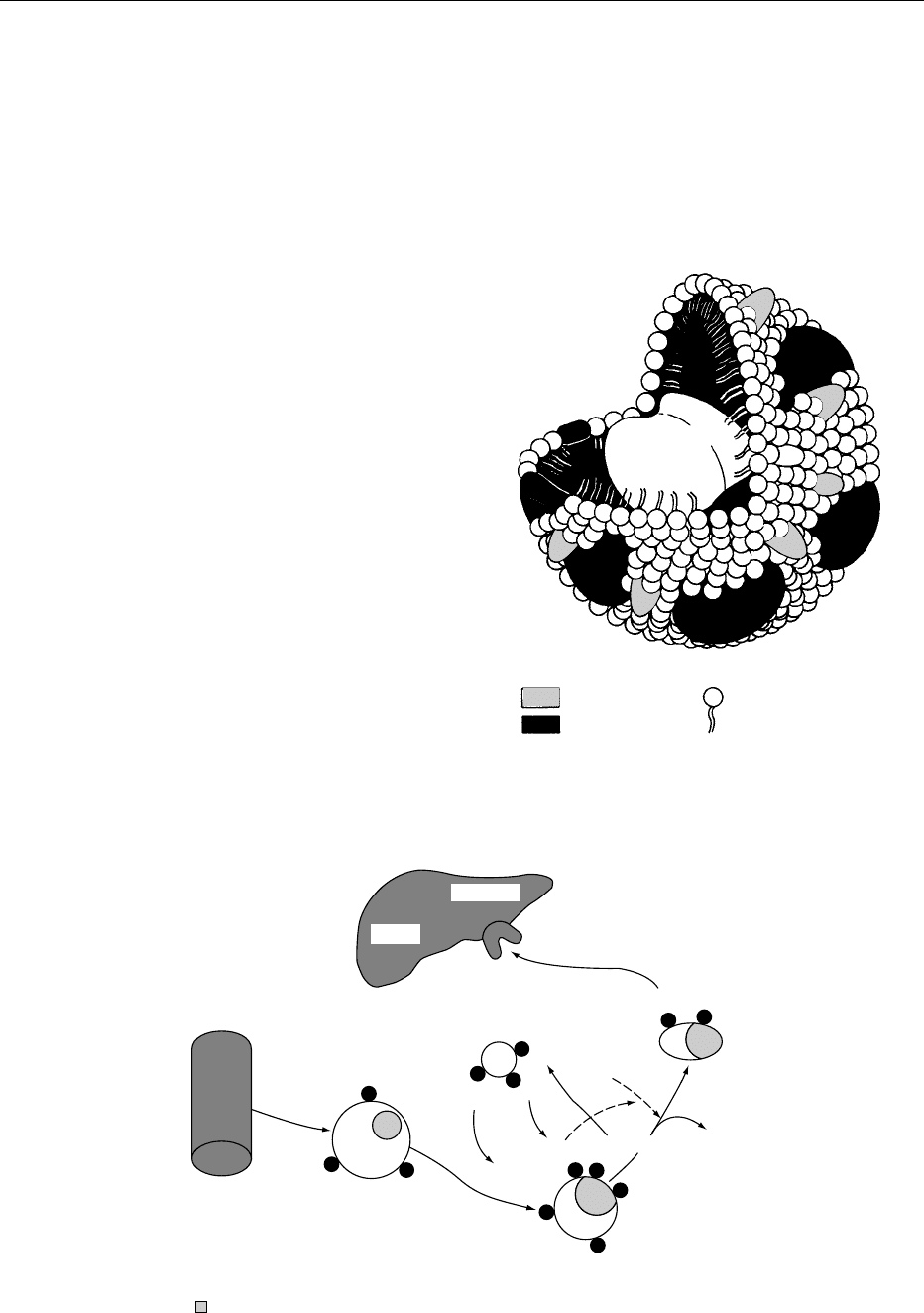

fig0001Figure 1 Diagram of a human plasma lipoprotein. From Feher

and Richmond, Lipid and Lipid Disorders, Gower Medical Publish-

ing, with permission.

Receptor

LIVER

Cholesterol

Tg

SMALL INTESTINE

Chylomicron

Apo−AI

Apo−B48 C

E

AI

LPL

Apo−CIII

Apo−CII

Apo−AI

Apo−E

Apo−E

Apo−B48

Apo−B48

Chylomicron

remnant

FFA

+

Glycerol

HDL

2

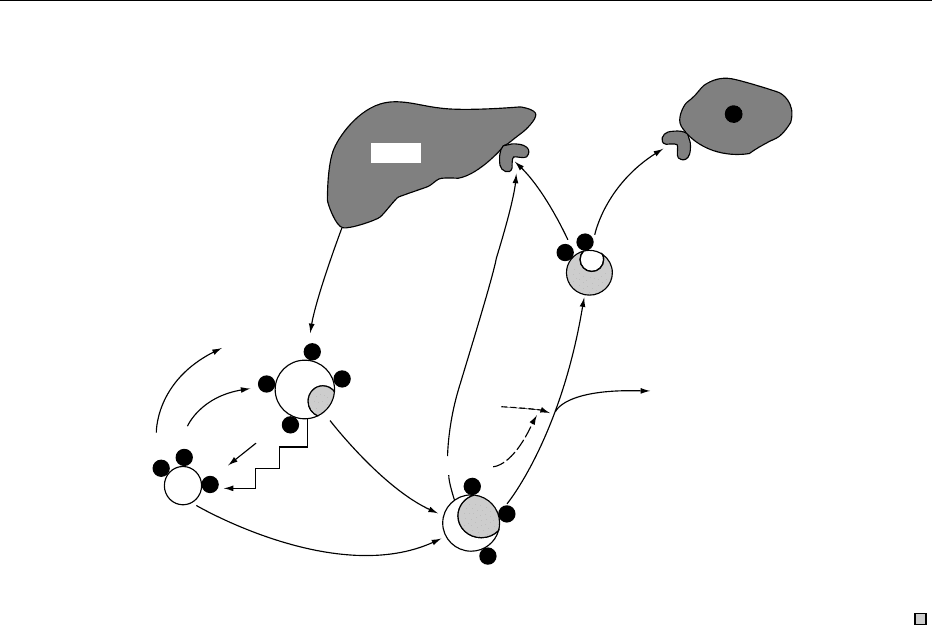

fig0002 Figure 2 Chylomicron metabolism: synthesis and degradation. The pathway for metabolism of triglyceride of exogenous, dietary

origin. h, triglyceride (Tg);

, cholesterol; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; FFA, free fatty acid. Reproduced from Hyperlipidaemia, Encyclo-

paedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993, Academic Press.

3184 HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA)

synthesized triglycerides, largely derived from dietary

carbohydrate or from plasma NEFA, and are of a

large size (30–60 nm diameter). Each VLDL particle

has a single molecule of a larger apoB form, apoB100,

with other apolipoproteins (apoE and apoCs) being

acquired in plasma from HDL. Like apoB48, apoB100

has a structural role, but also a functional role as a

ligand for catabolism. The same gene codes for apoB

in both gut and liver, but in the gut, there is post-

translational editing of messenger RNA, resulting in a

stop codon at position 2153. A truncated (48%)

apoB48 is then formed as the structural apolipopro-

tein, whereas in VLDL, the whole 100% of apoB is

synthesized to provide also the functional ligand

component.

0007 VLDL size is dependent on the triglyceride content,

with large buoyant triglyceride-enriched VLDL being

formed at times of triglyceride excess. These large

VLDL may be a poorer substrate for the usual path

of metabolism involving apoCII-dependent activation

of LPL and apoCII-LPL binding similar to that seen

with chylomicrons, and thus have a longer residency

time in the blood. As triglyceride is hydrolyzed,

VLDL particles shrink with loss of surface compon-

ents to HDL and subsequent catabolism to LDL via

IDL. This process is less efficient in the presence of

high triglyceride levels and large buoyant VLDL. A

longer plasma residency time allows a greater

exchange of triglyceride from VLDL into LDL and

HDL with reverse exchange of cholesterol ester,

mediated by cholesterol ester transfer protein

(CETP). This produces cholesterol-enriched VLDL

remnants that are less readily metabolized to LDL

and can be removed by alternative, but potentially

atherogenic, pathways. Additionally, this process

produces triglyceride-enriched LDL that shrink as

some triglyceride is hydrolyzed in the liver by another

endothelial enzyme, hepatic lipase, producing small,

dense LDL

3

(see below).

Intermediate Density Lipoproteins (IDL)

0008Intermediate density lipoproteins are formed as an

intermediate step in the normal metabolism of

VLDL. They are catabolized rapidly, and the concen-

tration in the plasma is therefore usually very low.

IDL are either taken up directly by the liver through

binding of surface apoE on IDL to apoE or apoB100/

apoE receptors, or are converted to LDL. The exact

mechanism of this is unclear but involves the loss of

Receptor

Receptor

LIVER

Apo−E

Apo−C

Apo−A

VLDL

Apo−B100

Apo−B100

E

C

A

Chol

CETP

HDL

2

*Chol

IDL

LDL

LPL

Apo−CII

Apo−E

Apo−E

Apo−B100

FFA

+

glycerol

EXTRAHEPATIC

TISSUES

fig0003 Figure 3 VLDL metabolism. The pathway for metabolism of triglyceride of endogenous, hepatic origin. h, triglyceride (Tg); ,

cholesterol; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; FFA, free fatty acid; Chol, free cholesterol; *Chol, esterified cholesterol; CETP, cholesterol ester

transfer protein. Reproduced from Hyperlipidaemia, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson

RK and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993, Academic Press.

HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA) 3185

apoE and the C-apolipoproteins and further triglycer-

ide hydrolysis by hepatic lipase.

Low Density Lipoproteins (LDL)

0009 LDL are effectively responsible for delivery to tissues

of cholesterol used for cell membrane synthesis and

repair, and for processes such as synthesis of steroid

hormones and vitamin D (Figure 4). Entry into cells

occurs either in a concentration-dependent nonspeci-

fic manner or, more importantly, by a very closely

regulated receptor-mediated pathway. LDL bind to

specific LDL apoB100/apoE receptors on cell mem-

branes, and LDL–receptor complexes are internalized

and undergo lysosomal degradation. The cholesterol

ester is hydrolyzed to free cholesterol, while most of

the LDL receptors are recycled. The highest concen-

tration of receptors is found in the liver.

0010 In order to maintain cellular function, the cell con-

tent of cholesterol is very tightly regulated. High

intracellular levels of free cholesterol lead to:

1.

0011 Suppression of endogenous cell cholesterol synthe-

sis by inhibition of the rate limiting enzyme 3-

hydroxy, 3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A reductase

(HMG CoA-reductase).

2.

0012 Suppression of apoB-100/apoE receptor synthesis.

3.

0013 Increased activity of acyl-coenzyme A cholesterol

acyl-transferase (ACAT), leading to increased

cholesterol esterification.

LDL particles are not homogeneous and can be

divided on the basis of size and density into LDL

1

,

LDL

2

, and LDL

3

. LDL

1

, the largest and least dense, is

a better substrate for the LDL receptor and is also less

easily oxidized. Individuals with higher levels of LDL

1

relative to LDL

3

are said to have a type A phenotype,

and those with the converse are said to have a type B

phenotype. Excess LDL

3

is associated with an excess

risk of coronary heart disease (see Hyperlipidemia

and the Origin of Clinical Atheroma below).

High Density Lipoproteins (HDL)

0014HDL are the smallest, most dense of the lipoproteins,

and are involved as cholesterol acceptors in reverse

cholesterol transport from the peripheral tissues to

the liver where the cholesterol is either excreted into

the bile or assembled into other lipoproteins

(Figure 5). HDL are synthesized in both the liver

and gut. Initially secreted as disk-shaped protein and

phospholipid bilayers, they mature by acquiring lipid

and protein components from intracellular and extra-

cellular fluids and from other lipoproteins to form

spherical particles of 5–15 nm diameter. The predom-

inant and structural apolipoproteins of HDL are

apolipoproteins A-I and A-II, with significant

amounts of apoCs and apoE, but with no apoB.

HDL particles are divided by size and density into

smaller and denser HDL

3

and larger and less dense

HDL

2

. HDL

2

particles tend to contain apo A-I only

and HDL

3

particles tend to contain both apoAI

and apoAII. The presence of larger, less dense HDL

2

correlates with more efficient reverse cholesterol

transport.

LDL

receptors

Protein

LDL

Cholesteryl

linoleate

LDL binding Internalization

Lysosomal

hydrolysis

Regulatory actions

1

2

3

Golgi apparatus

Cholesteryl

oleate

HMG CoA

reductase

ACAT

LDL receptors

1

2

3

Amino acids

fig0004 Figure 4 Regulation of intracellular cholesterol concentration by LDL-cholesterol uptake. Reproduced from Hyperlipidaemia, En-

cyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993, Academic Press.

3186 HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA)

0015 The mechanism of reverse cholesterol transport is

gradually being elucidated. Evidence suggests that

cells replete with cholesterol express HDL-binding

sites on the plasma membrane. Intracellular signaling

promotes hydrolysis of stored cholesterol esters,

movement of free cholesterol to the cell surface, and

transfer down a concentration gradient to HDL. Sur-

face cholesterol is esterified by lecithin cholesterol

acyl transferase (LCAT), an HDL-associated enzyme.

The resulting hydrophobic cholesterol ester enters the

HDL core, leaving the surface cholesterol depleted

and thus maintaining the concentration gradient

with the cell membrane. Cholesterol esters are trans-

ferred from HDL by CETP to VLDL, IDL, and LDL.

Cholesterol esters are delivered to the liver substan-

tially by receptor-mediated LDL uptake, and some

directly delivered from HDL. Synthesis of HDL

depends on transfer of surface components from

VLDL catabolism. When there is hypertriglycerid-

emia, the number and size of VLDL particles rise.

As larger VLDL particles tend to be catabolized

more slowly, the availability of surface components

for HDL is reduced, hence partly explaining the fre-

quent inverse relationship between the concentra-

tions of VLDL and HDL.

Consequences of Hyperlipidemia

0016While severe hypertriglyceridemia can lead to pan-

creatitis, the major consequence of hyperlipidemia is

accelerated atherogenesis with premature coronary

heart disease (CHD), stroke, and peripheral vascular

disease. The major risk factors for early CHD are

hypertension, cigarette smoking, hyperlipidemia,

and diabetes mellitus, risk increasing markedly when

multiple risk factors are present.

Hyperlipidemia and the Origins of Clinical

Atheroma

0017Atheroma occurs in large elastic and muscular arter-

ies such as the aorta, coronary, femoral, and carotid

LIVER

Cholesterol

SMALL INTESTINE

Apo−AI

Apo−AI

Apo−AII

Apo−AII

Apo−E

Apo−C Apo−D

LCAT

LCAT

CETP

*Chol

Chol

HDL

2

HDL

3

Cholesterol

CHOLESTEROL RICH

CELLs

VLDL

+

chylomicron

VLDL

fig0005 Figure 5 HDL metabolism; Chol, free cholesterol; *Chol, esterified cholesterol; CETP, cholesterol ester transfer protein; LCAT,

lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase. Reproduced from Hyperlipidaemia, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition,

Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993, Academic Press.

HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA) 3187

arteries, and especially at predisposed sites such as

bifurcations where there is flow disturbance. Plaques

form on the basis of fatty streaks that may be present

very early in life. Damage to the endothelial lining

from high blood pressure, local injury, or poor

oxygen supply results in increased permeability,

enabling lipoproteins to pass more easily into the

subendothelial space. LDL and triglyceride-rich lipo-

protein remnants are atherogenic. The influx into the

arterial wall depends on both the concentration and

the size of the LDL particles in plasma. The higher the

concentration of LDL in the plasma, the greater is the

degree of influx, and smaller denser LDL

3

particles

cross the endothelium more easily. LDL in the arterial

wall undergoes a number of changes including oxida-

tion with LDL

3

particles being more susceptible. The

oxidized LDL particles are engulfed by scavenger

macrophages. These macrophages are formed from

monocytes that have traversed the damaged endothe-

lial wall and are immobilized in response to a number

of chemical signals. In response to altered LDL, the

macrophages express acetylated LDL receptors and

take up LDL to become lipid rich foam cells. These

undergo apoptosis producing a lipid-rich extracellu-

lar medium. Smooth muscle cells migrate from the

arterial media in response to this process. These pro-

liferate and produce a connective tissue matrix rich

in collagen, elastin, and proteoglycans forming the

plaque cap, as part of a damage-healing process.

0018 Plaques may be asymptomatic. In contrast, they

may result in a significant reduction in blood flow,

producing symptoms such as angina or claudication.

A plaque that has a thin cap and a large lipid core

may be unstable and susceptible to rupture. In

such plaques, the excess macrophage component

produces metalloproteinases that break down the

collagen matrix (synthesized by smooth muscle

cells), making cap thinning and plaque rupture

(especially at the shoulder of the cap) more likely.

Should this happen, acute occlusion of a vessel may

occur, causing syndromes such as acute myocardial

infarction.

Classification of Hyperlipidemia

0019 Hyperlipidemia normally refers to high concentra-

tions of the blood lipids, cholesterol, and triglycer-

ides. These high levels reflect underlying changes in

lipoproteins, and could be caused by overproduction,

reduced catabolism or both. Thus, high levels of

triglycerides reflect elevated concentrations of the

triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, chylomicrons and

VLDL, and their remnants. An increase in cholesterol

concentration usually reflects an increase in LDL,

with or without an accompanying increase in VLDL.

Occasionally, raised total cholesterol may be due to a

very high HDL alone.

0020Hyperlipidemia may be secondary to other medical

disorders or therapy, or it may be primary. Primary

hyperlipidemia may be caused by a single gene defect

or, more commonly, by a polygenic background

influenced by environmental factors.

0021Originally, primary (inherited) disorders were

classified on the physicochemical characteristics of

lipoproteins defined in the laboratory using ultracen-

trifugation or electrophoresis (Table 1). Treatment of

a patient’s hyperlipidemia often results in changes in

the lipoprotein pattern and laboratory characteristics,

so that such a classification has limited value. It is

more useful to define the disease or metabolic defect,

and as this is becoming increasingly possible, efforts

to do this should always be made. Secondary causes

of hyperlipidemia are listed in Table 2. Obesity,

diabetes, and excess alcohol commonly act on a

genetic background to produce hyperlipidemia.

Hypercholesterolemia

Common or Polygenic Hypercholesterolemia

0022In the population as a whole, cholesterol levels

approach a normal distribution. Epidemiological

tbl0001Table 1 Classification of hyperlipidemia (Fredrickson’s

classification, as modified by the World Health Organization)

Ty p e o f

hyperlipidemia

Cholesterol Triglyceride Lipoprotein raised

I Raised Chylomicrons

IIa Raised Normal LDL

IIb Raised Raised LDL plus VLDL

III Raised Raised IDL

IV Normal or

raised

Raised VLDL

V Raised Markedly

raised

Chylomicrons plus

VLDL

tbl0002Table 2 Commoner secondary causes of hyperlipidemia

Cause Example

Metabolic and nutritional Obesity

Alcohol

Endocrine Diabetes mellitus

Hypothyroidism

Pregnancy

Drugs b-blockers

Thiazides

Estrogens

Renal disease Chronic renal failure

Nephrotic syndrome

Liver disease Biliary obstruction

3188 HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA)