Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

studies have shown that the risk of coronary artery

disease rises with the cholesterol level. Several large-

scale intervention studies have demonstrated that

lowering cholesterol reduces CHD risk in both pri-

mary and secondary (after the event) prevention.

0023 In addition to common or polygenic hyperchol-

esterolemia, a number of well-defined inherited

syndromes are well recognized resulting in hyper-

cholesterolemia and an increased CHD risk.

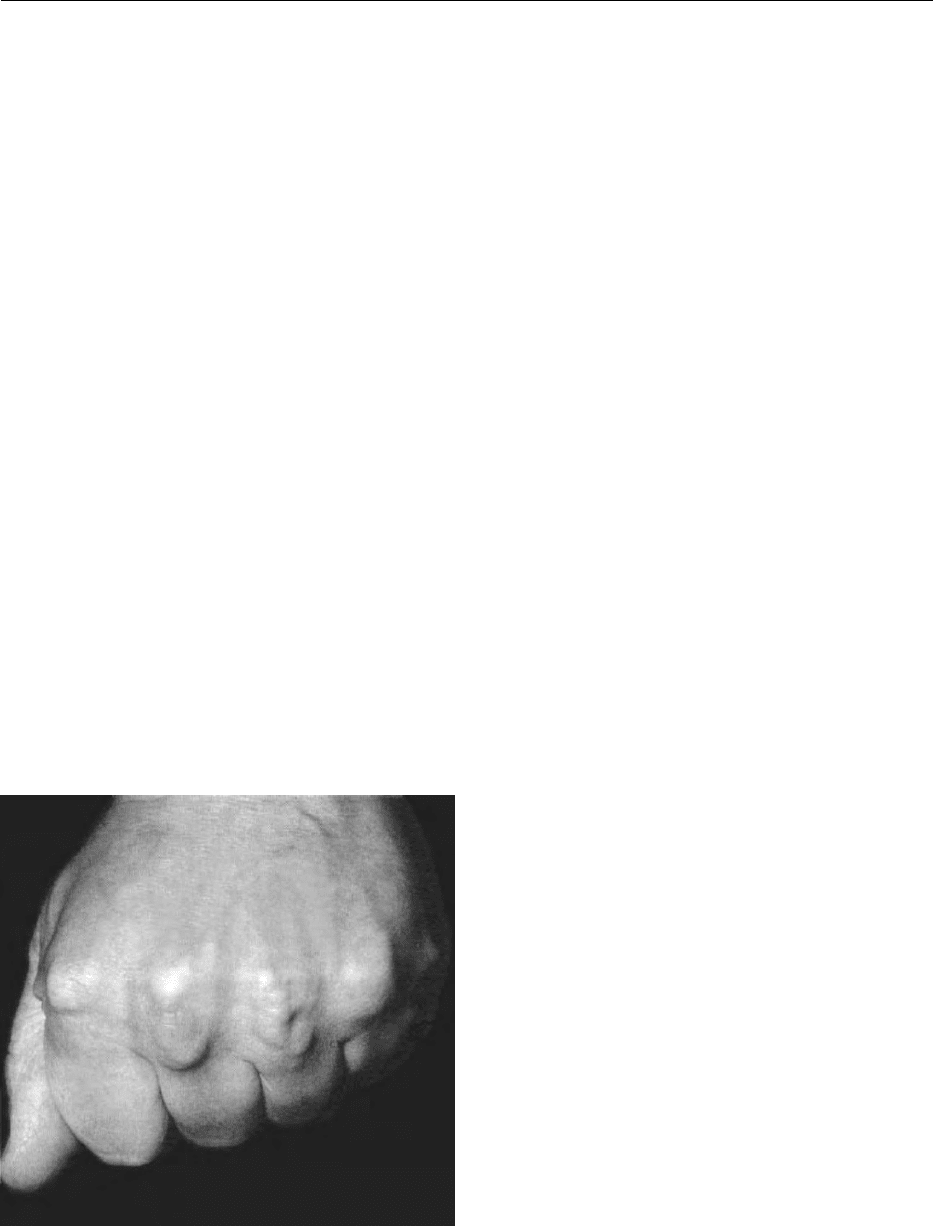

Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH)

0024 Familial hypercholesterolemia is the commonest dis-

ease in Western populations to be caused by a single

dominant gene defect. It is characterized by a raised

cholesterol from birth, subsequent development of

cutaneous and tendon xanthomata, and premature

vascular disease (Figure 6). The gene coding the

LDL receptor is found on chromosome 19. Over

150 different LDL receptor mutations have been

characterized, affecting receptor synthesis and func-

tion. Heterozygous FH (1 mutant and 1 normal gene)

affects 0.2% of the population, the homozygous con-

dition occurring at a rate of 1:1 000 000. A true

homozygote will have two copies of the same defect,

but compound heterozygosity (with two different

defects) is more common.

0025 Homozygous FH is characterized by extreme

hypercholesterolemia (cholesterol is approximately

four times normal) with cutaneous and tendon xan-

thomata and corneal arcus beginning in childhood.

Significant atheromatous involvement of the aortic

root with coronary ostial stenosis is present by pu-

berty, and death from coronary heart disease usually

occurs prior to the age of 20 in untreated individuals.

0026Tendon xanthomata are also pathognomonic of

heterozygous FH occurring in some adults. LDL chol-

esterol is typically twice normal. Untreated, it leads to

CHD in 50% of males by the age of 50 years, and

50% will have died by the age of 60. Fifty per cent of

females will have clinical CHD by age 60 when 15%

will have died.

0027The diagnosis of homozygous FH is usually

straightforward. Heterozygous FH should be con-

sidered in any patient with hypercholesterolemia

and personal or family premature CHD. Tendon

xanthomata in any family member almost certainly

establish the diagnosis, as does high LDL in children.

0028FH is also caused by abnormalities in apoB such as

in familial defective apolipoprotein B-100 where a

glutamine-for-arginine substitution in the amino acid

3500 codon in apoB produces an abnormal truncated

apoB with impaired binding to the LDL receptor.

Like classical FH, it is also an autosomal dominant,

affecting about one in 600 of the population.

Familial Combined Hyperlipidemia (FCH)

0029FCH was first described in 1973 in families of hyper-

lipidemic patients surviving a myocardial infarction.

Less clearly defined than FH, it affects perhaps 1–2%

of the population. It is heterogeneous, the etiology

remaining uncertain without a single gene defect

having been found. Diagnosis requires multiple

affected family members and is complicated by

variation in time of lipid levels that on occasion may

be normal. Cholesterol, triglycerides, or both may be

raised with type IIa, IIb, or IV phenotypes.

0030FCH predisposes to premature atherosclerosis and

may be present in 10% of patients with CHD before

age 60. Elevated apoB levels are frequently found that

may have a central role in atherogenesis in FCH, and

apoB concentrations can be a better predictor of

CHD than LDL cholesterol. LDL and VLDL each

contain one apoB100 molecule, so when apoB is

raised, there are increased plasma particle numbers.

As LDL numbers increase, the apoB:LDL cholesterol

ratio rises, as each particle is relatively cholesterol-

poor. LDL particles in FCH are smaller, denser, and

more atherogenic (see hyperlipidemia and the origins

of clinical atheroma). LDL

3

synthesis is enhanced by

the presence of hypertriglyceridemia.

0031In FCH, no mutations have been found in the apoB

structural locus on chromosome 2, but an apoB-

raising allele of uncertain location may occur in

fig0006 Figure 6 Xanthomata in the extensor tendons of the hands in

familial hypercholesterolemia. Reproduced from Hyperlipid-

aemia, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutri-

tion, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993,

Academic Press.

HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA) 3189

some FCH patients. Families heterozygous for LPL or

apoC-II deficiency (see Severe hypertriglyceridemia

below) may exhibit a phenotype similar to FCH.

Further work is needed to characterize the FCH gen-

etic background. Hyperapobetalipoproteinemia is a

related condition characterized by raised apoB with

normal LDL associated with premature CHD.

Hypertriglyceridemia

0032 Hypertriglyceridemia results from overproduction

of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and/or a catabolic

defect, due to either a primary lipoprotein disorder

or secondary to associated diseases.

Severe hypertriglyceridemia

0033 Severe hypertriglyceridemia (triglycerides > 11 mmol

l

1

) usually results from secondary factors (e.g., un-

controlled diabetes mellitus, obesity with insulin re-

sistance, and excess alcohol) acting upon a less severe

hyperlipidemia. Usually, treatment of the underlying

problem will partly correct the hypertriglyceridemia.

Inherited abnormalities of lipoprotein metabolism,

producing severe hypertriglyceridemia, cause accu-

mulation of chylomicrons with or without VLDL.

This gives a pancreatitic, and rarely a CHD, risk.

0034 Lipoprotein lipase deficiency A recessively inherited

condition affecting one per million population, this

deficiency is caused by mutations in the LPL gene on

chromosome 22 resulting in defective function and

chylomicron accumulation. Recurrent pancreatitis

usually occurs in early adulthood. Eruptive xantho-

mata are characteristic, and hepatosplenomegaly

and lipemia retinalis may occur, with triglycerides

100 mmol l

1

.

0035 Apolipoprotein C-II deficiency ApoC-II activates

LPL, and deficiency therefore presents similarly to

LPL deficiency, although it is rarer.

Moderate hypertriglyceridemia

0036 Moderate hypertriglyceridemia is often polygenic

exacerbated by secondary causes. It is seen frequently

with type 2 diabetes and obesity and is an independ-

ent CHD risk factor, particularly when associated

with a low HDL cholesterol. High triglycerides result

in reduced synthesis of HDL, more of which will be

HDL

3

, increased plasma levels of LDL

3

, and a

consequent increased risk of atheroma.

0037 The Insulin Resistance Syndrome (see Table 3) This

term was coined in 1988 to describe a cluster of

abnormalities that frequently occur together in type

2 diabetes. These people are often hypertensive and

obese with associated insulin resistance and hyper-

insulinemia. A consequence of insulin resistance is

increased catabolism of adipose tissue triglyceride

with release of nonesterified fatty acids. In the liver,

these are reformed into triglycerides and packaged as

VLDL, with larger VLDL numbers and size, a lower

HDL, and proportionately more LDL

3

. This partly

explains the threefold CHD increase seen in men with

type 2 diabetes and the three- to fivefold increase in

women.

Mixed Hyperlipidemia

0038Mixed hyperlipidemia with elevated triglycerides and

cholesterol is most commonly caused by polygenic

elevation of VLDL exacerbated by lifestyle or

environmental factors. It can manifest in FCH or FH.

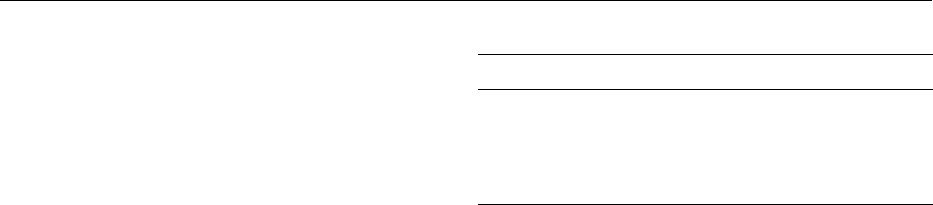

Remnant Hyperlipidemia

0039Remnant hyperlipidemia is also known as dysbeta-

lipoproteinemia, broad beta disease, or type III

hyperlipidemia, and has been recognized as a distinct

disease for 40 years. Remnant particles (IDL or b-

VLDL) of partial chylomicron or VLDL degradation

accumulate in about one in 5000 individuals, although

the gene defect affects about 1% of the population.

The diagnostic features are palmar crease and tuber-

ous xanthomata (Figure 7). Important complications

are premature CHD and peripheral vascular disease,

the predisposition to the latter being more than with

other dyslipidemias. It is more prevalent in men than

women, manifesting at age 25–40. The clinical dis-

order is brought out by factors such as obesity, dia-

betes, and untreated hypothyroidism.

0040Apolipoprotein E(apoE) is a 299-amino-acid glyco-

protein on all lipoproteins except LDL, serving as a

high-affinity ligand with the LDL, LRP, and apoE

receptors. A single gene controls ApoE expression,

with three common alleles, e2, e3, and e4, giving

rise to the major isoforms, E2, E3, and E4. Six differ-

ent phenotypes result: E2/E2, E2/E3, E2/E4, E3/E3,

E3/E4, and E4/E4. E3/E3 is the most common,

being found in 50–70% of populations. Isoforms

differ in amino acid composition, apoE2 having a

tbl0003Table 3 Features of the Insulin Resistance Syndrome

SyndromeX (The InsulinResistance Syndrome)

Hyperinsulinemia

Impaired glucose tolerance

Hypertension

Increased triglyceride

Decreased HDL cholesterol

3190 HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA)

cysteine-for-arginine substitution at amino acid 158.

This reduces binding to the apoE receptor to *1% of

normal. Homozygosity for apoE2 is the commonest

genotype in remnant hyperlipidemia. However, the

abnormality does not usually lead to hyperlipidemia,

but rather to marginally lower LDL cholesterol levels,

for it is only with secondary factors or an additional

primary lipemia that the syndrome is clinically ex-

pressed.

Dietary Effects

Body weight

0041 Obesity is an often ignored factor in hyperlipidemia,

but it is important, not least because it is linked

to other CHD risk factors such as blood, diabetes,

and glucose intolerance. Weight control is important

in treating hyperlipidemia, coupled with increased

exercise.

Fatty Acids and Cholesterol

0042 In Western societies, reducing saturated fat intake as

a percentage of total food energy is associated with a

reduction in total cholesterol and, to a lesser extent,

triglycerides. Levels of LDL fall, possibly as a result of

a direct reduction of cholesterol synthesis in the liver,

or increased excretion as bile acids. If saturated fatty

acids, such as palmitic acid, are replaced by mono- or

polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic or linoleic

acids, similar falls in serum cholesterol occur.

0043 Polyunsaturated fats of the n-6 series are primarily

of plant origin. In addition to the above, they help

reduce cholesterol by taking the place in the diet of

saturated fats, which tend to be of animal origin and

high in cholesterol. The n-3 series of fatty acids come

mainly from oily fish. These fatty acids may also have

beneficial effects on hemostatic variables of benefit in

thrombosis prevention. They can lower triglyceride

levels in some moderately hypertriglyceridemic indi-

viduals, but may have the disadvantage of increasing

LDL cholesterol. Plant sterols and stanols may also

reduce LDL by 10%.

0044The assumption that the amount of cholesterol in

the diet is the major factor causing hyperlipidemia is

false. It is the total fat intake as a percentage of the

total energy intake, and also whether or not the fat is

saturated, that matters most. Only a proportion of

cholesterol in the diet is absorbed, and for each

100 mg eaten, the serum cholesterol will rise by only

approximately 0.1 mmol l

1

. This response to dietary

cholesterol shows a considerable variation between

individuals.

Carbohydrate and Fiber

0045A high carbohydrate intake (particularly refined

carbohydrate and simple sugars) may induce hyper-

triglyceridemia. Substantial amounts of soluble or

mucilaginous fiber in the diet can lower LDL choles-

terol, possibly by increasing the fecal loss of sterols.

Individuals who eat a high-fiber diet also tend to eat

less saturated fat, and less total fat.

Alcohol

0046Alcohol, a rich source of energy, can contribute to

obesity and hypertriglyceridemia, and increase hep-

atic triglyceride synthesis and VLDL secretion. Sub-

strates that undergo oxidation in the liver have to

compete with alcohol, and therefore tend to be avail-

able for increased triglyceride synthesis. The tendency

to develop severe hypertriglyceridemia secondary to

alcohol is variable, but the risk of acute pancreatitis is

also increased.

See also: Bile; Cholecalciferol: Physiology; Cholesterol:

Role of Cholesterol in Heart Disease; Choline: Properties

and Determination; Essential Fatty Acids; Fats:

Classification; Occurrence; Fatty Acids: Properties;

Metabolism; Gamma-linolenic Acid; Fish Oils: Dietary

Importance; Hormones: Steroid Hormones;

Lipoproteins; Phospholipids: Properties and

Occurrence; Triglycerides: Structures and Properties

Further Reading

Barter PJ and Rye K (ed.) (1999) Plasma lipids and their role

in disease. In: Advances in Vascular Biology, vol. 5.

Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers.

fig0007 Figure 7 Palmar crease xanthomata of dysbetalipoprotein-

emia (remnant hyperlipidemia). Reproduced from Hyperlipid-

aemia, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and

Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993,

Academic Press.

HYPERLIPIDEMIA (HYPERLIPIDAEMIA) 3191

Betteridge DJ (ed.) (1990) Lipid and lipoprotein disorders.

In: Ballie

`

re’s Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism,

vol. 4, no. 4. London: Ballie

`

re Tindall.

Betteridge DJ, Illingworth DR and Shepherd J (ed.) (1999)

Lipoproteins in Health and Disease. London: Arnold.

Durrington PN (1989) Hyperlipidaemia: Diagnosis and

Management. Oxford: Wright Butterworth.

Packard C and Caslake M (1996) Mixed hyperlipidaemia

and the lipid shuttle. Issues in Hyperlipidaemia 13: 1–6.

Reaven GM (1988) Banting Lecture 1988. Role of insulin

resistance in human disease. Diabetes 37(12):

1595–1607.

Syvanne M and Taskinen M (1997) Lipids and lipoproteins

as coronary risk factors in non-insulin dependent dia-

betes mellitus. The Lancet 350(supplement 1): 20–23.

Thompson GR (1999) The proving of the lipid hypothesis.

Current Opinion in Lipidology 10: 201–205.

HYPERTENSION

Contents

Physiology

Hypertension and Diet

Nutrition in the Diabetic Hypertensive

Physiology

J J Klawe and M Tafil-Klawe, The Ludwik-Rydygier

Medical University, Bydgoszcz, Poland

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 An elevated blood arterial blood pressure is one of

the more important public health problems, being

asymptomatic, easily detectable, and often leading

to lethal complications.

Definition

0002 In adults a diastolic pressure below 85 mmHg is nor-

mal, between 85 and 89 mmHg is high normal, 90–

104 mmHg is mild hypertension, 105–114 mmHg

moderate hypertension, and 115 mmHg or greater is

severe hypertension. When the diastolic pressure is

below 90 mmHg, a systolic pressure below 140 mmHg

indicates normal blood pressure, between 140 and

159 mmHg is borderline isolated systolic hyperten-

sion, 160 mmHg or higher is isolated systolic hyper-

tension. Patients with arterial hypertension and no

definable cause are said to have primary, essential,

or idiopathic hypertension. More than 90% of all

patients with arterial hypertension are considered to

have essential or primary hypertension.

0003 The various forms of arterial hypertension are

listed below as a simplified classification of arterial

hypertension:

1.

0004Systolic hypertension with wide pulse pressure

a.

0005Decreased compliance of aorta

b.

0006Increased stroke volume

2.

0007Systolic and diastolic hypertension (increased

peripheral vascular resistance)

a.

0008Renal

b.

0009Endocrine

c.

0010Neurogenic

d.

0011Miscellaneous

e.

0012Unknown etiology

Individuals with a specific organ defect which is

responsible for hypertension are defined as having a

secondary form of hypertension.

0013The following information relates to the primary

form of arterial hypertension. Cardiac output and

peripheral vascular resistance are two basic hemody-

namic parameters regulating mean arterial pressure.

Cardiac output is usually normal in patients with

essential hypertension. Elevated blood pressure

appears to be associated with increased peripheral

vascular resistance. Some investigators have specu-

lated that the increased resistance may be due to

lack of nitric oxide, the locally produced vasodilator

that is produced by endothelial cells.

Genetic Factors in Hypertension

0014Animal studies and human investigations have indi-

cated an important role of genetic factors in essential

hypertension. Most studies support the concept that

inheritance is probably multifactorial or that a

number of different genetic defects each have elevated

blood pressure as one of their phenotypic expressions.

3192 HYPERTENSION/Physiology

Three monogene defects – glucocorticoid-remediable

aldosteronism (GRA), syndrome of apparent mineral-

ocorticoid excess (AME), and Liddle’s syndrome –

and susceptibility genes such as angiotensinogen gene

(AGT), renin gene (RN), pseudohipoaldosteronism

type II, and a-adducin gene (ADDI) have been

reported which have as one of their consequences

increased arterial pressure.

Environmental Factors

0015 A number of environmental factors are involved in the

development of hypertension. These include: obesity,

salt intake, alcohol intake, family size, and occupa-

tion. The influence of these factors increases with the

age of patients.

Salt Sensitivity

0016 In hypertensive population the blood pressure in

about 60% is responsive to level of sodium intake.

The cause of this special sensitivity to salt varies, and

includes primary aldosteronism, bilateral renal artery

stenosis, and other factors.

Renin and its Importance in Hypertension

0017 Renin is an enzyme secreted by the juxtaglomerular

cells of the kidney. It interacts with aldosterone in a

negative-feedback loop. Some hypertensive patients

are defined as having low-renin and high-renin

essential hypertension. About 20% of hypertensive

patients have suppressed plasma renin activity.

Approximately 15% of patients with essential hyper-

tension have plasma renin activity levels above the

normal range, which suggests that in these patients

plasma renin plays a significant role in the pathogen-

esis of arterial hypertension, activating the renin–

angiotensin–aldosterone axis. However other findings

have led some investigators to postulate that the

elevation of blood pressure and elevated renin levels

may be secondary to an increase in adrenergic system

activity.

Cell Membrane Defect

0018 The hypothesis about the role of a generalized cell

membrane defect in the pathogenesis of salt-sensitive

hypertension is derived from data from studies on red

blood cells, in which abnormalities in the transport

of sodium across the cell membrane have been

documented. This abnormality in sodium transport

reflects an alteration in cell membrane, and this defect

may occur in all cells of the body. An abnormal

accumulation of calcium in vascular smooth muscle

results in an increase in vascular responsiveness to

vasoconstrictor agents.

Reflex Mechanisms in Regulation of Blood

Pressure in Arterial Hypertension

0019The reflex mechanisms regulating blood pressure

include: arterial baroreceptors, cardiopulmonary

mechanoreceptors, arterial chemoreceptors, and

visceral receptors localized in the kidney, liver, and

intestine.

0020The baroreceptor reflex and from cardiopul-

monary mechanoreceptors are primary homeostatic

controls for blood pressure. Stretch-sensitive

mechanoreceptors are tonically active and thereby

tonically decrease a sympathetic activity. Addition-

ally, local release of NO from vascular epithelium

after each increase in blood pressure counteracts

blood pressure elevation. The cardiac response to

baroreceptor activation is vagal activation and a

decrease in heart rate. Several studies have shown

the impairment of baroreceptor function in arterial

hypertension.

0021The carotid chemoreceptors, activated by partial

pressure of oxygen in arterial blood and its

decrease, showed an augmented resting drive in

arterial hypertension. The pressor response to hyp-

oxic stimulation is also augmented in young

patients with essential hypertension. Reflex from

arterial chemoreceptors is probably involved in

the pathogenesis of arterial hypertension in ob-

structive sleep apnea syndrome. The episodes of

nocturnal hypoxia during sleep seem to be respon-

sible for an increase in sympathetic activity and

blood pressure.

0022The kidney–kidney reflex inhibits sympathetic

activity, increasing natriuresis and diuresis.

0023The osmoreceptors in the liver and in the digestive

system increase natriuresis and diuresis, decreasing

blood pressure.

0024The disturbance of interaction between the reflex

regulatory mechanisms is discussed as a factor which

may be involved in the pathogenesis of essential

arterial hypertension.

0025Hypertension is a risk factor for atherosclerosis

because high pressure in arteries damages the endo-

thelial lining of the vessels and promotes the forma-

tion of atherosclerotic plaques. Additionally, elevated

arterial pressure increases cardiac afterload.

See also: Atherosclerosis; Enzymes: Functions and

Characteristics; Hypertension: Hypertension and Diet;

Nutrition in the Diabetic Hypertensive; Renal Function

and Disorders: Kidney: Structure and Function

HYPERTENSION/Physiology 3193

Further Reading

Klawe JJ, Tafil-Klawe M, Peter JH and Smietanowski M

(1999) Cardiac response study towards activation and

inactivation of the carotid baroreceptor in obstructive

sleep apnea patients. Medical Science Monitoring 5(3):

449–451.

Narkiewicz K and Somers VK (1997) The sympathetic

nervous system and obstructive sleep apnea: implica-

tions for hypertension. Journal of Hypertension 15:

163–1619.

Person PB (1996) Modulation of cardiovascular control

mechanisms and their interaction. Physiological Review

76: 193–244.

Przybylski J (1981) Do arterial chemoreceptors play a

role in the pathogenesis of hypertension? Medical

Hypotheses 20: 173–177.

Tafil-Klawe M, Raschke F and Hildebrandt G (1990)

Functional asymetry in carotid sinus cardiac reflexes in

humans. European Journal of Applied Physiology and

Occupational Physiology 60: 402–405.

Tafil-Klawe M, Raschke F, Becker H et al. (1991) Investi-

gations of arterial baro- and chemoreflexes in patients

with arterial hypertension. In: Peter JH, Penzel T,

Podszus T and v Wichert P (eds) Sleep and Health

Risk, pp. 319–334. Springer Verlag.

Trzebski A (1992) Arterial chemoreceptor reflex and hyper-

tension. Hypertension 19: 562–566.

Trzebski A, Tafil M, Zoltowski M and Przybylski J (1982)

Increased sensitivity of the arterial chemoreceptor drive

in young men with mild hypertension. Cardiovascular

Research 16: 162–172.

Williams GH (2001) Hypertensive vascular disease. In: Har-

rison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, pp. 1380–1394.

New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Hypertension and Diet

B M Y Cheung and T C Lam, University of Hong Kong,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Nutrition as a Cause of Hypertension

0001 Hypertension is a common condition that affects

more than one-tenth of the adult population. The

complications of untreated hypertension include

stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiac and renal fail-

ure. Its etiology is complex and probably involves the

interaction of genetic predisposition and the environ-

ment in the widest sense. There is familial clustering

of hypertension, which can be a reflection of both

shared genes and shared environment or both. As a

person’s genes is probably not open to modification,

especially when the disease-causing gene(s) have not

been identified, prevention and treatment of hyper-

tension should be targeted at altering the environ-

mental factors. Results from many population and

migrant studies show that environmental factors

play an important role in the occurrence of hyperten-

sion. One such factor determining the development of

hypertension is undoubtedly nutrition. Poor nutri-

tional habits, alcohol consumption, excessive sodium

and insufficient potassium intake are some of the

nutritional factors leading to hypertension. These,

together with socioeconomic status, physical inactiv-

ity, psychological stress, and obesity, influence blood

pressure in an individual.

Fetal Origin of Hypertension

0002Barker and colleagues have put forward the ‘fetal

origins hypothesis’ that links cardiovascular disease

manifested in adulthood to poor nutrition in utero

and infancy. Fetal undernutrition in middle to late

gestation is thought to result in adaptive changes in

fetal growth that predispose to coronary heart dis-

ease. The evidence comes from a longitudinal study of

25 000 middle-aged Britons. Those who were small at

birth and not premature had relatively high rates of

coronary heart disease, hypertension, hypercholester-

olemia, and diabetes. Postnatal nutrition also appears

to influence blood pressure in later life. Premature

babies randomized in a study to breast milk had

lower blood pressure in adolescence than those ran-

domized to formula milk. If the fetal origins hypoth-

esis, which is difficult to prove prospectively, is

correct, optimizing prenatal care may prevent hyper-

tension and other cardiovascular diseases in adult-

hood.

Dietary Pattern and Hypertension

0003There are striking differences in the blood pressure of

populations worldwide. Blood pressure is higher and

rises more steeply with age in industrialized than

in nonindustrialized societies. A predominantly vege-

tarian dietary pattern is generally present in those

populations that have low average blood pressure.

In industrialized countries, vegetarians have lower

blood pressures than nonvegetarians (Figure 1).

0004Epidemiological and intervention studies including

the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT)

suggest a multitude of dietary changes that may

reduce blood pressure. The Dietary Approaches to

Stop Hypertension (DASH) Trial tested three diet-

ary patterns: (1) a control diet that resembled the

average US diet; (2) a combination diet high in fruit,

3194 HYPERTENSION/Hypertension and Diet

vegetables, whole-grain cereal products, low-fat dairy

products, fish, chicken, and lean meats but low in fat

and cholesterol; and (3) a fruit and vegetables diet

that tested the effects of fruit and vegetables alone

and was similar in other nutrients to the control diet.

Sodium content was the same in all the diets and the

subjects maintained their prestudy body weight

throughout the trial. The combination diet was

found to reduce the systolic pressure by 11 mmHg

and the diastolic pressure by 6 mmHg (Figure 2).

The fruit and vegetables diet reduced blood

pressure by half this amount. Remarkably, the effect

of the combination diet in the hypertensives

approaches the effect of treatment with a single

antihypertensive drug.

Sodium

0005 Sodium is tightly regulated through a variety of

coordinated homeostatic mechanisms involving the

sympathetic nervous system, the renin–angiotensin

system, and natriuretic peptides. A minute rise in

blood pressure is sufficient to augment sodium excre-

tion to achieve sodium balance in normal kidneys. In

salt-sensitive hypertension, there is an exaggerated

blood pressure response to increased sodium intake.

Older patients, overweight type 2 diabetics, or those

of African descent tend to have hypertension of this

type. They have low renin levels and a lesser pressor

response to sodium deprivation. In such hyper-

tensive individuals, sodium restriction is effective

and beneficial. The controversy surrounding salt and

hypertension stems from the fact that not everyone is

salt-sensitive and it has been argued that reducing

the salt intake in the general population is neither

practical nor effective, and may even be harmful to

some people. However, the relationship between salt

and blood pressure is now well established (Figure 3),

and the higher the salt intake of the population, the

steeper the rise in blood pressure with age. Interest-

ingly, in primitive communities, blood pressure does

not rise with age.

0006In many western countries, daily sodium intake

is between 150 and 200 mmol. The Trial Of

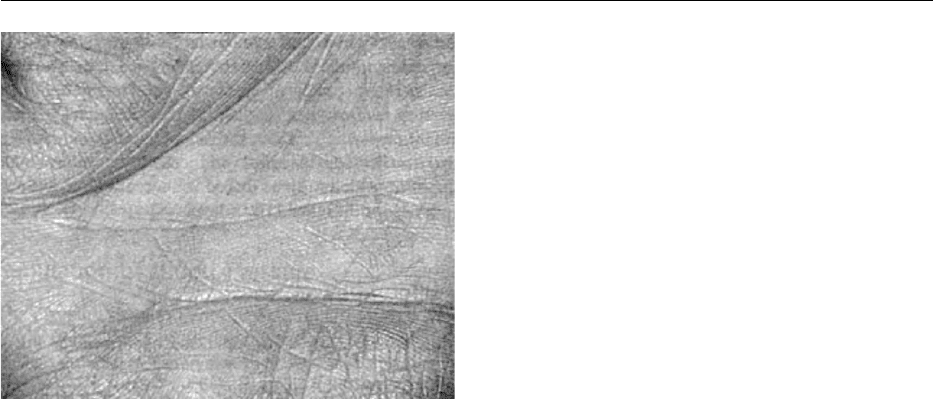

16−29

50

60

70

80

90

Strict vegetarian

Systolic

BP

Diastolic

Strict vegetarian

Nonvegetarian

Nonvegetarian

Framingham

Framingham

East Boston

East Boston

100

110

120

130

30−39

Age (years)

40−65

fig0001 Figure 1 Blood pressure (BP) in a strict vegetarian population

in Boston and in nonvegetarian populations in East Boston and

Framingham, MA. Adapted from Sacks FM and Kass EH. Low

blood pressure in vegetarians: effects of specific food and nutri-

ents. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 48: 795–800, with

permission.

−12

−5.5

−2.8

−4.5

−3.1

−11.4

−7.2

−6.8

−3.6

−10

−8

Change

in

systolic

BP

Clinic

Overall

Hypertensives

clinic

Minority-group

clinicABP

−6

−4

−2

0

fig0002Figure 2 Effect of dietary patterns on blood pressure (BP) in the

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) study. ABP,

ambulatory blood pressure. Open columns, combination diet;

filled columns, fruit and vegetable diet. Adapted from Appel LJ,

Moore TJ, Obarzanek E et al. (1997) A clinical trial of the effects

of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative

Research Group. New England Journal of Medicine 336(16): 1117–

1124, with permission.

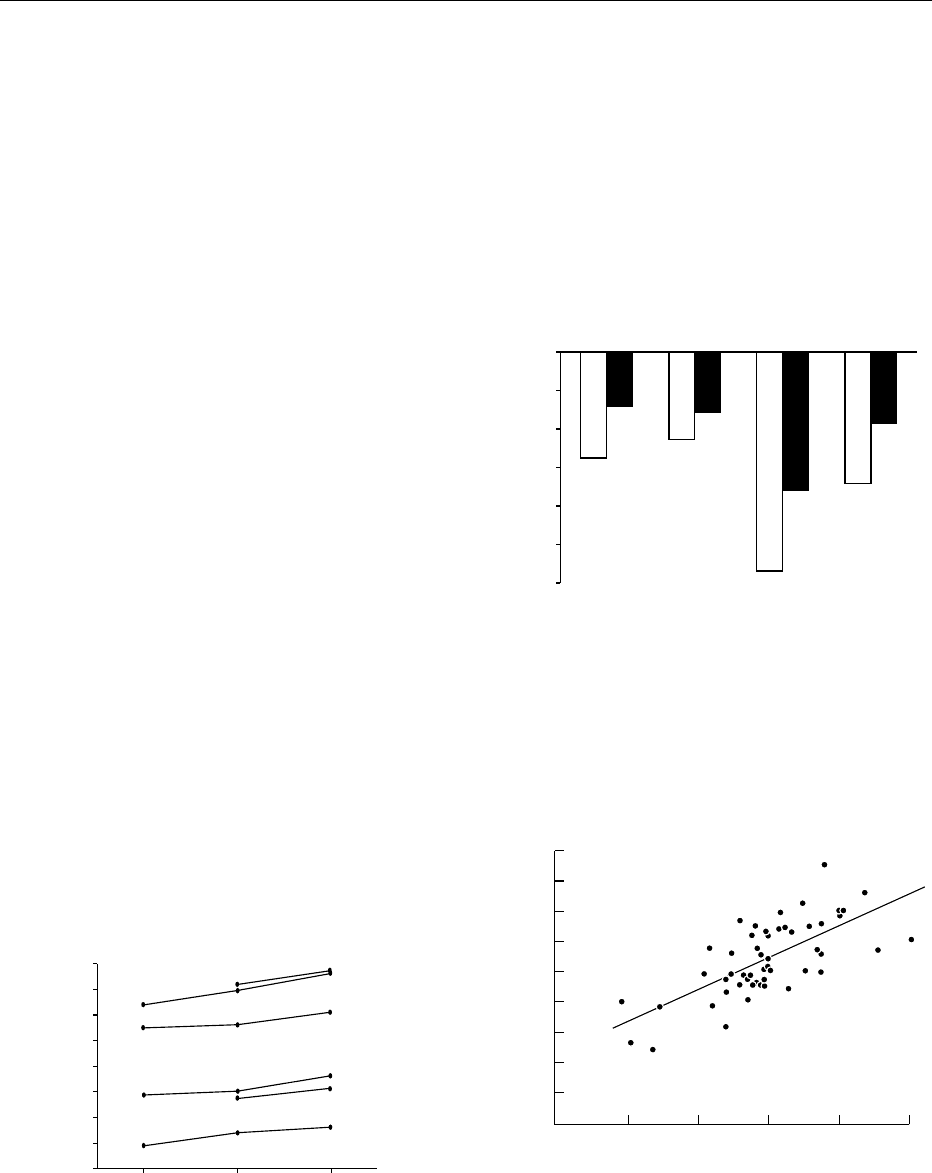

0

Adjusted diastolic blood pressure slope with age

(mmHg year

−1

)

Adjusted sodium excretion (mmol 24 h

−1

)

52 centers: b = 0.0021

(SE 0.0003) mmHg year

−1

mmol

−1

sodium*

−0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

50 100 150 200 250

fig0003Figure 3 Cross-center plots of diastolic pressure slope with

age and median sodium excretion and fitted regression lines

for 52 centers, also adjusted for body mass index and alcohol

intake. *P < 0.001. Reproduced from Intersalt Cooperative Re-

search Group (1988). Intersalt: an international study of electro-

lyte excretion and blood pressure: results for 24-hour urinary

sodium and potassium excretion. British Medical Journal 297:

319–328, with permission.

HYPERTENSION/Hypertension and Diet 3195

Nonpharmacological Intervention in the Elderly

(TONE) showed that a 40 mmol day

1

reduction is

accompanied by significant reductions in blood

pressure (5.3/3.4 mmHg). This modest salt restric-

tion can be achieved by not adding salt at the table

and avoiding foods that are high in sodium content

(e.g., preserved food). Saltiness is a rather crude

taste and is used by the industry to enhance the

palatability of food cheaply and to boost the sale

of beverages. Historically, salt was needed to pre-

serve food for the winter months but nowadays,

refrigeration renders this unnecessary. Fresh food is

usually low in salt content and its flavors are better

appreciated when not too much salt has been added

in cooking.

0007 Carefully controlled clinical studies have demon-

strated a dose-dependent relationship between

dietary salt intake and blood pressure, although trials

of salt restriction do not always show a useful re-

duction in blood pressure due to their various trial

designs. Salt restriction is particularly important

when the patient is treated with an angiotensin-

converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or an angiotensin

II antagonist (sartan). The efficacy of these drugs is

diminished in the presence of high salt intake that

suppress the renin–angiotensin system.

Potassium

0008 In contrast to sodium, potassium is less tightly regu-

lated physiologically. In diuretic therapy, the renal

tubules will conserve sodium at the expense of

potassium. Plasma potassium concentration is also

linked to acid–base balance. Nevertheless, potassium

is also closely associated with blood pressure. Cross-

sectional studies in many countries worldwide had

identified an inverse relationship between blood pres-

sure and various measures of serum, urine, total body

and dietary potassium. Low potassium intake may

also underlie the high incidence and prevalence of

hypertension in blacks and the elderly. Potassium

supplementation alone will decrease blood pressure

slightly. The effect is more pronounced in hyperten-

sives than normotensives, in blacks than in whites,

and in those with high sodium intake. In reality,

higher potassium intake is usually associated with a

diet rich in fruit and vegetables. Such a diet will in

itself be conducive to a lower blood pressure, so one

cannot always disentangle the components of a

‘healthy diet’ which are actively antihypertensive.

High sodium intake and low potassium intake is a

common scenario amongst hypertensive patients.

Therefore, sodium and potassium should be con-

sidered jointly in our dietary recommendations.

For example, using a salt substitute that contains

potassium chloride increases potassium intake whilst

reducing sodium intake.

Calcium

0009The relationship between calcium and hypertension

is controversial. Dietary intake of calcium tends

to be lower in hypertensives and calcium supple-

mentation is associated with a modest reduction in

blood pressure. A metaanalysis of 23 observational

studies showed an inverse association between

blood pressure and dietary calcium intake. The effect

size was however small and heterogeneous across

studies. Metaanalysis of randomized trials of calcium

supplementation showed that systolic blood

pressure is reduced by around 1 mmHg. Although it

is possible that certain subgroups may be more sensi-

tive to the effects of calcium, it is certainly not the

major factor in the pathogenesis of hypertension,

despite the recent identification of a parathyroid

hypertensive factor. Therefore, calcium supplementa-

tion, though desirable for other reasons, is not

currently recommended as an efficacious means of

treating hypertension.

Fat

0010The relationship between lipids and coronary heart

disease is now proven beyond doubt by epidemi-

ological studies and large-scale trials of lipid-

lowering drugs (statins) that reduce coronary events.

Reduction in cholesterol by pharmacological means

may not lower blood pressure, but should be viewed

in the context of the overall reduction of cardiovas-

cular risk and the reduction of complications of

hypertension such as myocardial infarction. Hyper-

tension and dyslipidemia are independent cardio-

vascular risk factors and, when they are both present

in the same person, the cardiovascular risk is aug-

mented. Therefore, it makes sense to address both

risk factors. Nonpharmacological means of lipid

lowering through diet and exercise is likely to have

a beneficial effect on blood pressure in addition to

improving the cardiovascular risk profile. The

DASH study suggested that a healthy diet based on

less fat and more fruit and vegetables reduces blood

pressure, although precisely which component of the

DASH diet lowers blood pressure remains to be

elucidated.

0011The effects of saturated, monosaturated, and poly-

unsaturated fatty acids and carbohydrates have been

studied in many clinical trials. Omega-3 unsaturated

fatty acids (fish oils) reduce blood pressure but a large

intake is needed, so this is not a practical treatment

for hypertension.

3196 HYPERTENSION/Hypertension and Diet

Obesity

0012 It has become clear in recent years that obesity is one

of the major determinants of blood pressure. Our

own observations in relatives of hypertensive patients

suggest that the occurrence of hypertension is related

to whether the relative is obese or not. It therefore

appears that those who may be genetically predis-

posed to hypertension will develop the condition if

they become obese.

0013 Recently, two genes involved in the control of body

weight, the OB gene and the OB receptor gene, which

code for the hormone leptin and its receptor respect-

ively, have been described in the mouse. Deletions in

the OB gene or the OB receptor lead to profound

obesity of early onset with excessive food intake,

decreased energy expenditure, and insulin resistance.

In humans, mutations in the corresponding genes

have been reported. A high level of circulating leptin

is found in the majority of obese people, suggesting

that they have leptin resistance. Transgenic mice over-

expressing leptin develop hypertension. However, the

association of high leptin levels and hypertension

has not been firmly established in humans, so the

relevance of these genes to the pathogenesis of essen-

tial hypertension remains to be elucidated.

0014 Obesity, especially abdominal adiposity, is more

closely related to blood pressure than body weight.

Moreover, obesity can lead to insulin resistance

and ultimately overt type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lean,

normoglycemic untreated hypertensive subjects are

more insulin-resistant than comparable normo-

tensive subjects. The relationship between insulin

resistance and hypertension may involve a variety of

mechanisms, including increased sympathetic ner-

vous system activity, proliferation of vascular

smooth-muscle cells, altered cation transport, and

increased sodium retention. It is worth noting than

one-third of diabetics have hypertension and a signifi-

cant proportion of hypertensives have diabetes. The

two conditions overlap to a large extent as compon-

ents of the ‘metabolic syndrome’ or ‘syndrome X.’

0015 Measurement of blood pressure in those who are

obese and have large arms is prone to overestimation

if the cuff is not large enough. Nevertheless, the rela-

tionship between obesity and blood pressure is well

established and indeed, for the overweight hyperten-

sive, losing weight, if it can be achieved, is the most

efficacious means of reducing blood pressure amongst

the various nonpharmacological treatment options.

Our own data and those of other investigators suggest

that for each kilogram of body weight lost, there is

approximately a 1 mmHg reduction in diastolic blood

pressure and a 2 mmHg reduction in systolic blood

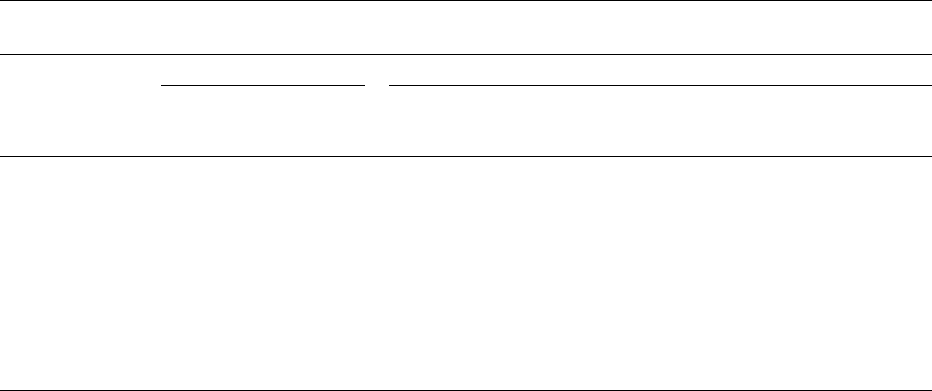

pressure (Figure 4). Unfortunately, outside clinical

trials, this is easier said than done. A coordinated

approach involving a physician, nurse, and dietitian

and attendance of classes is probably more effective

than advice from a single professional. As with

other nonpharmacological measures, weight control

through diet and exercise will lead to benefits in

addition to blood pressure control, such as a better

lipid profile, better cardiovascular fitness, less stress

on the joints, and so on.

Alcohol

0016The effect of alcohol on health in general and cardio-

vascular diseases in particular is dose-dependent. A

modest regular intake is probably beneficial because

of the increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

(HDL-C) and the relief of stress whilst a high intake is

definitely harmful. With increasing levels of alcohol

intake, more than 50 epidemiological studies from a

variety of cultures have reported an increase in blood

pressure or a higher prevalence of hypertension. An

excessive alcohol intake raises blood pressure and

moderation of alcohol intake leads to reduction in

blood pressure (Table 1). In practice, hypertensive

patients who do not drink alcohol should not be

encouraged to start doing so whilst those who do

drink large quantities must be encouraged to reduce

Wei

g

ht (k

g

)

DBP (mmHg)

50

70

60 70 80 90 100

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

fig0004Figure 4 The effect of weight reduction on diastolic blood pres-

sure (DBP). (^) MacMahon et al. (1985) Lancet 1: 1233–1236; (&)

Gordon et al. (1997) American Journal of Cardiology 79: 763–767;

(m) Singh et al. (1995) Journal of Human Hypertension 9: 355–362;

() Jalkanen et al. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine 19: 66–

71; (

*

) Singh et al. (1990) Nutrition 6: 297–302; () Wassertheil-

Smoller S et al. (1992) The Trial of Antihypertensive Interventions

and Management (TAIM) study. Archives of Internal Medicine

152(1): 131–136; (|) Darne et al. (1993) Blood Pressure 2: 130–135;

(s) Haynes et al. (1984) Journal of Hypertension 2: 535–539; (n)

Fagerberg et al. (1989) British Medical Journal 299: 480–485; (^)

Andersson et al. (1991) Hypertension 18: 783–789.

HYPERTENSION/Hypertension and Diet 3197

their intake to the recommended levels. Currently, it

is believed that men should not drink more than 21

units per week and women should not drink more

than 14 units per week. Approximately one unit of

alcohol, or 14 g ethanol, is contained in one glass

of table wine.

Dietary Approach to Prevent or Treat

Hypertension

0017 Alteration of the diet to bring about a lower

blood pressure is not only beneficial in those who

are hypertensive, but is prudent in those who are not

yet hypertensive and even in those who are normo-

tensive. A shift in the distribution of the blood pres-

sures to a lower mean for the population is expected

to lead to a massive reduction in the incidence of

coronary heart disease and stroke. Achieving a

healthier diet will delay or even prevent the onset of

hypertension. This may be especially relevant in

young people who have a strong family history of

hypertension or cardiovascular diseases. In those

who have newly diagnosed hypertension, dietary

intervention may obviate the need for drug therapy.

In patients with mild hypertension who respond to

diet and the nonpharmacological approach, cessation

of therapy may be possible. In those hypertensive

patients who still require drug therapy, an appropri-

ate diet will reduce the intensity of treatment and

facilitate blood pressure control.

0018 There is no single diet that will fit everyone’s

needs. The elderly might be more responsive to salt

restriction whilst the young obese hypertensive

should have a diet low in fat and calories. Clinicians

rarely have the time or the training to go through a

diet with the patient so the help of dietitians and other

health care professionals is crucial for successful

implementation of dietary intervention.

0019Although most of the dietary recommendations are

well accepted by health care professionals and the

community, their implementation is a major problem

since a change in behavior is needed. Eating and alco-

hol drinking are normally pleasurable experiences

and many do not find regular exercise enjoyable, so

diet, abstinence, and exercise require determination

and commitment. There is a limit as to how much

health care professionals can do in this regard. It is

therefore important that the doctor, nurse, and

dietitian complement each other and reinforce the

message in a team approach.

0020There is another obstacle to a healthy diet: food

sold in fast-food outlets is convenient, inexpensive,

and therefore popular. Such food is high in salt and fat

content and is generally not fresh. Tinned and other

preserved food has a high salt content; McGregor has

argued that reducing the salt intake in the general

population requires the cooperation of the food

industry to reduce the salt content in its products.

Health care professionals need to be aware of the

economical and social aspects in order to give advice

that can feasibly be followed. In developing countries,

the highest incidence of hypertension is found in

people with high socioeconomic status. As countries

become more affluent, hypertension becomes more

prevalent in the lower socioeconomic classes. In

developed countries, there is an inverse relationship

between socioeconomic status and blood pressure.

Proposed mechanisms include differences in diet

(sodium, potassium, calories), physical activity, body

mass, alcohol intake, psychosocial stress, and access

tbl0001 Table 1 Randomized controlled trials of the effects of alcohol reduction on blood pressure (BP)

Study, year Studypopulation Studyresults

n Age (years)

(mean + SD or range)

Duration

(weeks)

Baseline

BP

(mm Hg)

Alcoholintake

difference

(drinks

a

perday)

BP difference

(mm Hg)

P

Puddey, 1985 46 35+8 6 133/76 3.7 3.8/1.4 <0.001/<0.05

Howes, 1985 10 25–41 0.6 120/66 5.7 8/6 <0.025/<0.001

Puddey, 1987 44 53+16 6 142/84 4.0 5/3 <0.001/<0.001

Ueshima, 1987 50 46+7 2 148/93 2.6 5.2/2.2 <0.005/NS

Wallace, 1988 641 42+20 52 136/82 1.0 2.1/? <0.05/NS

Parker, 1990 59 52+11 4 138/85 3.8 5.4/3.2 <0.01/0.01

Cox, 1990 72 20–45 4 132/73 3.4 4.1/1.6 <0.05/<0.05

Maheswaran, 1992 41 40s 8 144/90 3.1 Not reported NS

Puddey, 1992 86 44 18 137/85 3.0 4.8/3.3 <0.01/<0.01

Ueshima, 1993 54 44+8 3 144/96 1.7 3.6/1.9 <0.05/NS

PATHS, 1998 641 57+11 104 140/86 1.3 0.9/0.6 0.16/0.10

a

A standard drink is defined as 14 g ethanol and is contained in a 12-oz/350 ml glass of beer, a 5-oz/146 ml glass of table wine, or 1.5/44 ml oz of distilled

spirits.

3198 HYPERTENSION/Hypertension and Diet