Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

begun. Moreover, she was determined to repair the

economic–financial ravages of the war that had just

ended. It was one thing to declare a new policy,

however, and something else to institute it. In

preparing the two manifestoes of 1762–1763 the

Senate discovered many partial precedents and sev-

eral concrete impediments to welcoming masses of

immigrants. More than six months elapsed be-

tween the issuance of the two manifestoes, during

which time governments were consulted and insti-

tutions formulated to care for the anticipated new-

comers. It was decided that the manifesto should

list the specific lands available for settlement and

not exclude any groups. Drawing on foreign prece-

dent and the suggestion of Senator Peter Panin, the

manifesto of 1763 established a special government

office with jurisdiction over new settlers, the

Chancery of Guardianship of Foreigners. The first

head, Count Grigory Orlov, Catherine’s common–

law husband and leader of her seizure of the throne,

personified the office’s high status. The new Russ-

ian immigration policy offered generous material

incentives, promised freedom of religion and ex-

emption from military recruitment, and guaran-

teed exemption from enserfment and freedom to

leave. These provisions governed immigration pol-

icy until at least 1804 and for many decades there-

after. The manifesto of 1763 did not specifically

exclude Jews, although Elizabeth’s regime banned

them as “Killers of Christ,” for Catherine highly re-

garded their entrepreneurship and unofficially en-

couraged their entry into New Russia (Ukraine) in

1764.

European immigrants responded eagerly to the

manifesto, some twenty thousand arriving during

Catherine’s reign. Germans settling along the Volga

were the largest group, especially the Herrnhut

(Moravian Brethren) settlement at Sarepta near

Saratov and Mennonite settlements in southern

Ukraine. Because of the empire’s largely agrarian

economy, most settlers were farmers. The expense

of the program was large, however, so its cost–

effectiveness is debatable. A century later many

Volga Germans resettled in the United States, some

still decrying Catherine’s allegedly broken promises.

See also: CATHERINE II; JEWS; ORLOV, GRIGORY GRIG-

ORIEVICH; PALE OF SETTLEMENT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bartlett, Roger P. (1979). Human Capital: The Settlement

of Foreigners in Russia 1762-1804. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Khodarkovsky, Michael. (2002). Russia’s Steppe Frontier:

The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500-1800. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

J

OHN

T. A

LEXANDER

MANSI

The 8,500 Mansi (1989 census), formerly called

Voguls, live predominantly in the Hanti-Mansi Au-

tonomous Region (Okrug), in the swampy basin of

the Ob river. Their language belongs to the Ugric

branch of the Finno-Ugric family. It has little mu-

tual intelligibility with the related Hanti language,

farther northeast, and essentially none with Mag-

yar (Hungarian). Most Mansi have Asian features.

One of the most distinctive features of Mansi (and

Hanti) culture is an elaborate bear funeral cere-

mony, honoring the slain beast.

The Mansi historical homeland straddled the

middle Urals, southwest of their present location

on the Konda River. They offered spirited resistance

to Russian encroachment during the 1400s, high-

lighted by prince Asyka’s counterattack in 1455.

The Russians destroyed the last major Mansi prin-

cipality, Konda, in 1591. Within one generation,

Moscow ignored whatever capitulation treaties had

been signed. As settlers poured into the best Mansi

agricultural lands, the Mansi were soon reduced to

a small hunting and fishing population. By 1750

most were forced to accept the outer trappings of

Greek Orthodoxy, while practicing animism in se-

cret. Russian traders reduced people unfamiliar

with the notion of money and prices to loan slav-

ery that lasted for generations.

When the Ostiako-Vogul National Okrug Dis-

trict—the present Hanti-Mansi Autonomous

Oblast—was created in 1930, the indigenous pop-

ulation was already down to 19 percent of the to-

tal population. By 1989, the population had

dropped to 1.4 percent, due first to a massive in-

flux of deportees and then to free labor, after dis-

covery of oil during the 1950s. The curse of Arctic

oil impacted the natives, who were crudely dispos-

sessed, as well as the fragile ecosystem. Gas torch-

ing and oil spills became routine.

Post-Soviet liberalization enabled the Hanti and

Mansi to organize Spasenie Ugry (Salvation of Yu-

gria, the land of Ugrians) that gave voice to in-

digenous and ecological concerns. Thirty-seven

percent of the Mansi population (and few young

MANSI

893

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

people) spoke Mansi in the early 1990s. A weekly

newspaper, Luima Serikos, had a circulation of 240

in 1995. Novels on Mansi topics by Yuvan Sestalov

(b. 1937) have many readers in Russia.

See also: FINNS AND KARELIANS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; NORTHERN

PEOPLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Forsyth, James. (1992). A History of the Peoples of Siberia:

Russia’s North Asian Colony, 1581–1990. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Taagepera, Rein. (1999). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the

Russian State. London: Hurst.

R

EIN

T

AAGEPERA

MARI EL AND THE MARI

The Mari, or Cheremis, are an indigenous people of

the European Russian interior; their language and

that of the Mordvins compose the Volgaic branch

of the Finno-Ugric language family.

As subjects of the Volga Bolgars and Kazan

Tatars, medieval Mari tribes experienced cultural

and linguistic influences mainly from their Turkic

neighbors. Later on, Slavic contacts became promi-

nent, and the Russian language became the princi-

pal source of lexical and syntactic borrowing. The

early twentieth-century initiatives to create a sin-

gle literary language did not come to fruition. Con-

sequently, there are two written standards of Mari:

Hill and Meadow. The speakers of various western,

or Hill Mari, dialects constitute hardly more than

10 percent of the Mari as a whole.

In the basin of the Middle Volga, the medieval

Mari distribution area stretched from the Volga-

Oka confluence to the mouth of the Kazanka River.

Under Tatar rule, the Mari were active participants

in Kazan’s war efforts. Apparently due to their loy-

alty and peripheral location, Mari tribal communi-

ties were granted home rule. However, the final

struggle between the Kazan Khanate and Moscow

brought an intraethnic cleavage: the Hill Mari sided

with the Russians, whereas the Meadow Mari re-

mained with the Tatars until the fall of Kazan in

1552.

The submission to Moscow was painful: The

second half of the sixteenth century saw a series of

uprisings, known as the Cheremis Wars, which

decimated the Meadow Mari in particular. The

Russian invasions triggered population movements

that also reshaped the Mari settlement area: a part

of the Meadow Mari migrated to the Bashkir lands

and towards the Urals. For about two hundred

years, the resettlement was sustained by land

seizures, fugitive peasant migrations, and Chris-

tianization policies. The outcome of all this was the

formation of the Eastern Mari. In terms of religion,

these Mari have largely kept their traditional “pa-

ganism,” whereas their Middle Volga coethnics are

mostly Orthodox, or in a synchretic way combine

animism with Christianity.

The Mari ethnic awakening took its first steps

with the 1905 and 1917 Revolutions. In 1920 the

Bolsheviks established the Mari autonomous

province. It was elevated to the status of an au-

tonomous republic in 1936—the year of the Stal-

inist purges of the entire ethnic intelligentsia. Since

1992, the republic has been known as the Repub-

lic of Mari El.

At the time of the 1989 census, 324,000 Mari

out of a total of 671,000 were residents of their

titular republic. There the Mari constituted 43.2

percent of the inhabitants, whereas Russians made

up 47.5 percent. Outside Mari El, the largest Mari

populations were found in Bashkortostan (106,000)

as well as in Kirov and Sverdlovsk provinces

(44,000 and 31,000 respectively). Indicative of lin-

guistic assimilation, 17 percent of the Mari con-

sidered Russian their native language during the

1994 microcensus.

In 2000 Mari El was a home for 759,000 peo-

ple. Within Russia, it is an agricultural region, poor

in natural resources and heavily dependent on fed-

eral subsides. Within the republic’s political elite,

the Mari have mainly performed secondary roles,

and this situation has deteriorated further since the

mid-1990s. Because Russians outnumber the Mari,

and because the Mari still lag behind in terms of

urbanity, education, and ethnic consciousness,

Russians dominate the republic’s political life.

See also: FINNS AND KARELIANS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fryer, Paul, and Lallukka, Seppo. (2002). “The Eastern

Mari.” <http://www.rusin.fi/eastmari/home.htm>.

Lallukka, Seppo. (1990). The East Finnic Minorities in the

Soviet Union: An Appraisal of the Erosive Trends. (An-

MARI EL AND THE MARI

894

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

nales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae, Ser. B, vol.

252). Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia.

Taagepera, Rein. (1999). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the

Russian State. London: Hurst.

S

EPPO

L

ALLUKKA

MARKET SOCIALISM

The economic doctrine of market socialism holds

that central planners can make active and efficient

use of “the market” as a mechanism for imple-

menting socially desired goals, which are developed

and elaborated through central planning of eco-

nomic activity. Focusing on the elimination of pri-

vate property and wealth, and on the central

determination and control of all investment and de-

velopment decisions, it posits that the planned de-

termination and adjustment of producers’ and asset

prices could allow markets to implement the de-

sired allocations in a decentralized manner without

sacrificing central or social control over outcomes

or incomes. Thus egalitarian social outcomes and

dynamic economic growth can be achieved simul-

taneously, without the disruptions and suffering

imposed by poorly coordinated private investment

decisions resulting in a wasteful business cycle.

The idea of market socialism arose from the re-

alization that classical socialism, involving the col-

lective provision and distribution of goods and

services in natural form, without the social con-

trivances of property, markets, and prices, was not

feasible, since rational collective control of eco-

nomic activity requires calculations that cannot

rely consistently on “natural unit” variables such

as energy or labor amounts. It also became clear

that the existing computing capabilities were inad-

equate for deriving a consistent economic plan from

a general equilibrium problem. This led, in the So-

cialist Calculation Debate of the 1930s, to the sug-

gestion (most notably by Oskar Lange) that a

Socialist regime, assuming ownership of all means

of production, could use markets to find relevant

consumers’ prices and valuations while maintain-

ing social and state control over production, income

determination, investment, and economic develop-

ment. Managers would be instructed to minimize

costs, while the planning board would adjust pro-

ducers’ prices to eliminate disequilibria in the mar-

kets for final goods. Thus, at a socialist market

equilibrium, the classical marginal conditions of

static efficiency would be maintained, while the

State would ensure equitable distribution of in-

comes through its allocation of the surplus (profit)

from efficient production and investment in so-

cially desirable planned development.

Another version of market socialism arose as a

result of the reform experiences in east-central Eu-

rope, particularly the labor-managed economic

system of Yugoslavia that developed following

Marshal Tito’s break with Josef Stalin in 1950.

This gave rise to a large body of literature on

the “Illyrian Firm” with decentralized, democratic

control of production by workers’ collectives in a

market economy subject to substantial macroeco-

nomic planning and income redistribution through

taxation and subsidies. The economic reforms in

Hungary (1968), Poland (1981), China after 1978,

and Gorbachev’s Russia (1987–1991) involved

varying degrees of decentralization of State Social-

ism and its administrative command economy,

providing partial approximations to the classical

market socialist model of Oskar Lange. This expe-

rience highlighted the difficulties of planning for

and controlling decentralized markets, and revealed

the failure of market socialism to provide incen-

tives for managers to follow the rules necessary for

economic efficiency. Faced with these circum-

stances, proponents of market socialism moved be-

yond state ownership and control of property to

various forms of economic democracy and collec-

tive property, accepting the necessity of real mar-

kets and market prices but maintaining the classical

socialist rejection of fully private productive prop-

erty. The early debates on market socialism are best

seen in Friedrich A. von Hayek (1935), while the

current state of the debate is presented in Pranab

Bardhan and John E. Roemer (1993).

See also: PERESTROIKA; PLANNERS’ PREFERENCE; SOCIAL-

ISM; STATE ORDERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bardhan, Pranab, and Roemer, John E., eds. (1993). Mar-

ket Socialism: The Current Debate. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Granick, David. (1975). Enterprise Guidance in Eastern Eu-

rope: A Comparison of Four Socialist Economies. Prince-

ton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hayek, Friedrich A. von, ed. (1935). Collectivist Economic

Planning: Critical Studies on the Possibilities of Social-

ism. London: Routledge.

Kornai, János. (1992). The Socialist System: The Political

Economy of Communism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

MARKET SOCIALISM

895

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Lange, Oskar, and Taylor, Fred M. (1948). On the Eco-

nomic Theory of Socialism. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

R

ICHARD

E

RICSON

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE

As elsewhere in Europe, marriage and family life in

Russia have varied across time and by social group,

reflecting the complex interplay of competing

ideals, changing patterns of social and economic or-

ganization, differing forms of political organization

and levels of state intrusiveness, and the effects of

cataclysmic events. If in the long run the outcome

of this interplay of forces has been a family struc-

ture and dynamic that conform essentially with

those found in modern European societies, the de-

velopment of marriage and the family in Russia

nevertheless has followed a distinctive path. This

development can be divided into three broad peri-

ods: the centuries preceding the formation of the

Russian Empire during the early eighteenth cen-

tury, the imperial period (1698–1917), and the pe-

riod following the Bolshevik Revolution and

establishment of the Soviet state in October 1917.

While the pace of development and change varied

significantly between different social groups dur-

ing each of these periods, each period nonetheless

was characterized by a distinctive combination

of forces that shaped marital and family life and

family structures. In Russia’s successive empires,

moreover, important differences also often existed

between the many ethno-cultural and religious

groups included in these empires. The discussion

that follows therefore concerns principally the

Slavic Christian population.

PRE-IMPERIAL RUSSIA

Although only limited sources are available for the

reconstruction of marital and family life in me-

dieval Russia, especially for nonelite social groups,

there appears to have been broad continuity in the

structure and functioning of the family through-

out the medieval and early modern periods. Fam-

ily structures and interpersonal relations within

marriage and the family were strongly shaped by

the forms of social organization and patterns of

economic activity evolved to secure survival in a

harsh natural as well as political environment.

Hence, constituting the primary unit of production

and reproduction, and providing the main source

of welfare, personal status, and identity, families

in most instances were multigenerational and

structured hierarchically, with authority and eco-

nomic and familial roles distributed within the

family on the basis of gender and seniority. While

scholars disagree over whether already by 1600 the

nuclear family had begun to displace the multi-

generational family among the urban population,

this development did not affect the patriarchal

character or the social and economic functions of

either marriage or the family. Reflecting and rein-

forcing these structures and functions, the mar-

riage of children was arranged by senior family

members, with the economic, social, and political

interests of the family taking precedence over indi-

vidual preference. Land and other significant assets,

too, generally were considered to belong to the fam-

ily as a whole, with males enjoying preferential

treatment in inheritance. Marriage appears to have

been universal among all social groups, with chil-

dren marrying at a young age, and for married

women, childbirth was frequent.

After the conversion of Grand Prince Vladimir

of Kievan Rus to Christianity in 988, normative

rules governing marriage and the family also were

shaped and enforced by the Orthodox Church, al-

though the effective influence of the Church spread

slowly from urban to rural areas. Granted exten-

sive jurisdiction over marital and family matters

first by Kievan and then by Muscovite grand

princes, the Church used its authority to establish

marriage as a religious institution and to attempt

to bring marital and family life into conformity

with its doctrines and canons. For example, the

Church sought—with varying degrees of success—

to limit the formation of marriages through re-

strictions based on consanguinity and age, to

restrict marital dissolution to the instances defined

by canon law, to limit the possibility of remarriage,

and to confine sexual activity to relations between

spouses within marriage for the purpose of pro-

creation. At the same time, through its teachings,

canonical rules, and ecclesiastical activities, the

Church reinforced the patriarchal order within

marriage and the family, thereby providing a reli-

gious sanction for established social structures and

practices. Hence the extent to which the Church

transformed or merely reinforced existing ideals of

and relationships within marriage and the family

remains disputed.

Although patriarchal attitudes and structures

and a gendered division of labor also prevailed

within elite households, the role of family and lin-

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE

896

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

eage in determining relative status within and

between elite groups, access to beneficial appoint-

ments and the material rewards that followed from

them, and the prospects for forming advantageous

marriage alliances between families imparted dis-

tinctive characteristics to elite family life, especially

after the late fifteenth century. The practice among

the Muscovite elite of secluding women in separate

quarters (the terem), for example, which reached its

greatest intensity during the seventeenth century,

appears to have been due largely to the desire to

protect family honor and ensure the marriage util-

ity of daughters in a context in which the elite was

growing in size and complexity. Seclusion itself,

however, considerably increased the politically im-

portant role of married women in arranging and

maintaining family alliances. Similarly, the devel-

opment of a system of service tenements in land to

support the expansion especially of military servi-

tors after the late fifteenth century led initially to

a deterioration in the property and inheritance

rights of elite women. Yet such women also often

had principal responsibility for managing the es-

tates and other affairs of husbands who frequently

were away on military campaigns or carrying out

other service assignments. Hence within the Mus-

covite elite, and quite likely among other social

groups in pre-Petrine Russia as well, the normative

ideal and legal rules supporting the patriarchal

family often concealed a more complex reality. This

ideal nonetheless provided a powerful metaphor

that helped to legitimize and integrate the familial,

social, and political orders.

IMPERIAL RUSSIA

The history of marriage and the family during the

imperial period was marked both by a complex pat-

tern of continuity and change and by sharp diver-

sity between social groups, as the exposure of

different groups to the forces of change varied sig-

nificantly. Nonetheless, by the early twentieth cen-

tury the long-term trend across the social spectrum

was toward smaller families, the displacement of

the multigenerational family by the nuclear fam-

ily, a higher age at the time of first marriage for

both men and women, declining birth rates, an in-

creased incidence of marital dissolution, and, in ur-

ban areas, a decline in the frequency of marriage.

Within the family, the structure of patriarchal au-

thority was eroding and the ideal itself was under

attack.

The groups that were exposed earliest and most

intensively to the combination of forces lying

behind these trends were the nobility, state offi-

cialdom, the clergy, and a newly emergent intelli-

gentsia and largely urban bourgeoisie. During the

eighteenth century, for example, the nobility rep-

resented the main target and then chief ally of the

state in its efforts to inculcate European cultural

forms and modes of behavior and to promote for-

mal education and literacy. Among the effects of

such efforts was a new public role for women and

the dissemination of ideals of marriage, family, and

the self that eventually came to challenge the pa-

triarchal ideal. By helping to produce by the first

half of the nineteenth century a more profession-

alized, predominantly landless, and largely urban

civil officialdom, as well as a chiefly urban cultural

intelligentsia and professional bourgeoisie, changes

in the terms of state service and the expansion of

secondary and higher education both provided a re-

ceptive audience for new ideals of marriage and the

family and eroded dependency on the extended

family. By expanding the occupational opportuni-

ties not only for men but also for women outside

the home, the development of trade, industry, pub-

lishing, and the professions had similar effects.

Most of these new employment opportunities were

concentrated in Russia’s rapidly growing cities,

where material and physical as well as cultural con-

ditions worked to alter the family’s role, structures,

and demographic characteristics. For this reason,

the marital and demographic behavior and family

structures of urban workers also exhibited early

change.

At least until after the late 1850s, by contrast,

marriage and family life among the peasantry,

poorer urban groups, and the merchantry dis-

played greater continuity with the past. This con-

tinuity resulted in large part from the strength of

custom and the continued economic, social, and

welfare roles of the multigenerational, patriarchal

family among these social groups and, at least

among the peasantry, from the operation of com-

munal institutions and the coincident interests of

family patriarchs (who dominated village assem-

blies), noble landowners, and the state in preserv-

ing existing family structures. Facilitated by the

abolition of serfdom in 1861, however, family

structures and demographic behavior even among

the peasantry began slowly to change, especially

outside of the more heavily agricultural central

black earth region. In particular, the increased fre-

quency of household division occurring after the

emancipation contributed to a noticeable reduction

in family size and a decline in the incidence of the

multigenerational family by the last third of the

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE

897

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

century, although most families still passed

through a cycle of growth and division that in-

cluded a multigenerational stage. While marriage

remained nearly universal, the age at first marriage

also rose for both men and women, with the re-

sult that birth rates declined somewhat. The

growth of income from local and regional wage la-

bor, trade, and craft production and the rapid ex-

pansion of migratory labor contributed to all these

trends, while also helping to weaken patriarchal

structures of authority within the family, a process

given further impetus by the exposure of peasants

to urban culture through migratory labor, mili-

tary service, and rising literacy. Although most

peasant migrants to cities, especially males, re-

tained ties with their native village and household,

and consequently continued to be influenced by

peasant culture, a significant number became per-

manent urban residents, adopting different family

forms and cultural attitudes as a result. With the

rapid growth of Russian cities and the transfor-

mation of the urban environment that took place

after the late 1850s, family forms and demographic

behavior among the poorer urban social groups and

the merchantry also began to change in ways sim-

ilar to other urban groups.

Normative ideals of marriage and the family

likewise exhibited significant diversification and

change during the imperial period, a process that

accelerated after the late 1850s. If closer integra-

tion into European culture exposed Russians to a

wider and shifting variety of ideals of marriage, the

family, and sexual behavior, the development of a

culture of literacy, journalism and a publishing in-

dustry, and an ethos of civic activism and profes-

sionalism based on faith in the rational use of

specialized expertise broadened claims to the au-

thority to define such ideals. These developments

culminated in an intense public debate over reform

of family law—and of the family and society

through law—after the late 1850s. Very broadly,

emphasizing a companionate ideal of marriage, the

need to balance individual rights with collective re-

sponsibilities and limited authority within mar-

riage and the family, and the necessity of adapting

state law and religious doctrines to changing social

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE

898

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

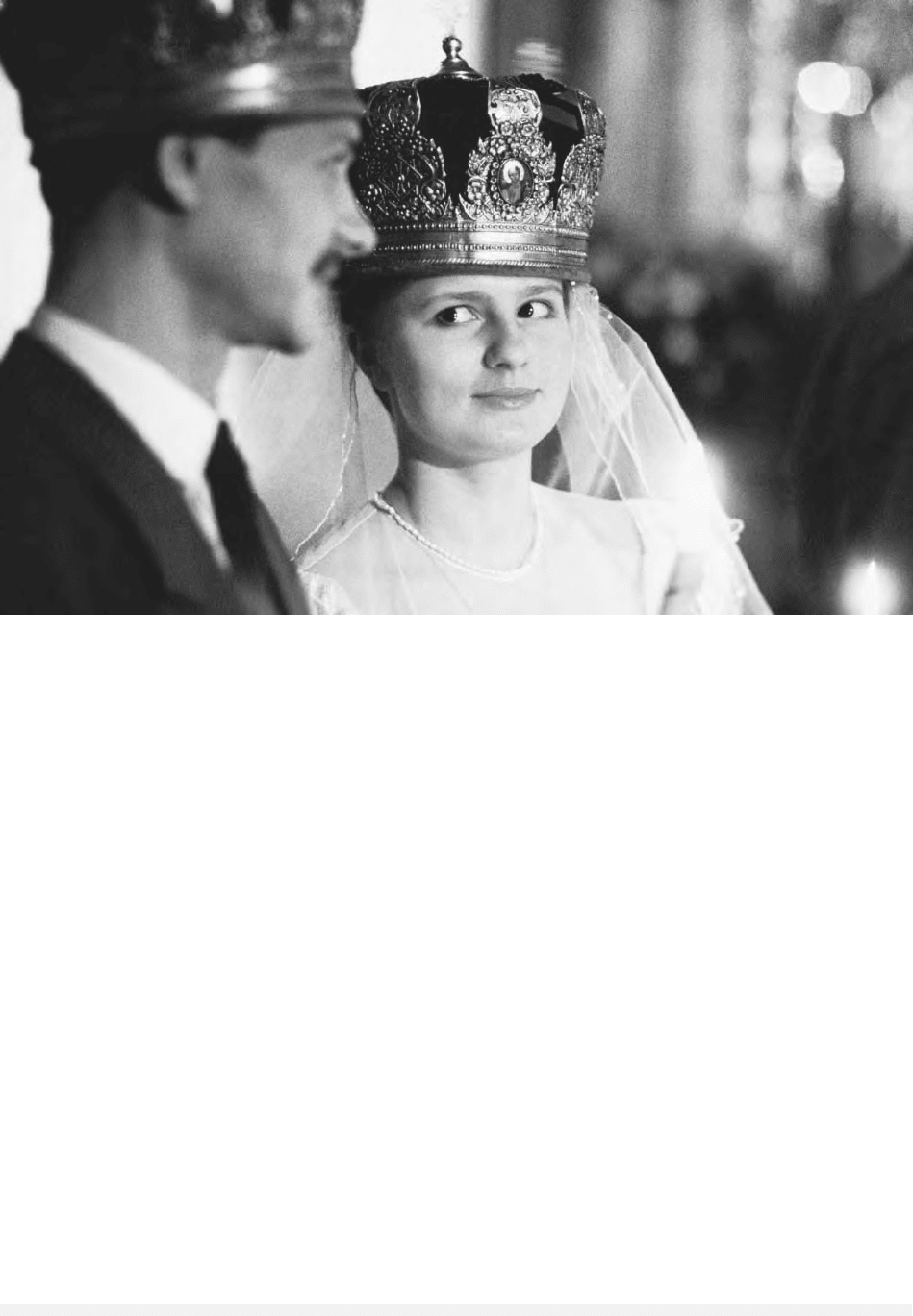

A young couple exchanges their marriage vows during an Orthodox ceremony in Chelyabinsk. © P

ETER

T

URNLEY

/CORBIS

and historical conditions, advocates of reform fa-

vored the facilitation of marital dissolution, equal-

ity between spouses in marriage, greater rights for

children born out of wedlock, the recasting of in-

heritance rights based on sexual equality and the

nuclear family, and the decriminalization of vari-

ous sexual practices as well as of abortion. Many

of these principles in fact were embodied in draft

civil and criminal codes prepared by government

reform commissions between 1883 and 1906, nei-

ther of which was adopted, and proposals to ex-

pand the grounds for divorce made by a series of

committees formed within the Orthodox Church

between 1906 and 1916 proved similarly unsuc-

cessful. Socialist activists adopted an even more

radical position on the reconstitution of marriage

and the family, in some cases advocating the so-

cialization of the latter. Opponents of reform, by

contrast, stressed the social utility, naturalness, and

divine basis of strong patriarchal authority within

marriage and the family, the congruence of this

family structure with Russian cultural traditions,

and the role of the family in upholding the auto-

cratic social and political orders. Although signifi-

cant reforms affecting illegitimate children,

inheritance rights, and marital separation were en-

acted in 1902, 1912, and 1914, respectively, deep

divisions within and between the state, the Ortho-

dox Church, and society ensured that reform of

marriage and the family remained a contentious is-

sue until the very end of the autocracy, and be-

yond.

SOVIET RUSSIA

With respect to marriage and the family, the long-

term effect of the Soviet attempt to create a mod-

ern socialist society was to accelerate trends already

present in the early twentieth century. Hence, by

the end of the Soviet period, among all social groups

family size had declined sharply and the nuclear

family had become nearly universal, the birth rate

had dropped significantly, marriage no longer was

universal, and the incidence of marital dissolution

had risen substantially. But if by the 1980s the

structure and demographic characteristics of the

Russian family had come essentially to resemble

those found in contemporary European societies,

the process of development was shaped by the dis-

tinctive political and economic structures and poli-

cies of Soviet-style socialism.

Soviet policies with respect to marriage and the

family were shaped initially by a combination of

radical ideological beliefs and political considera-

tions. Hence, in a series of decrees and other en-

actments promulgated between October 1917 and

1920, the new Soviet government introduced for-

mal sexual equality in marriage, established divorce

on demand, secularized marriage, drastically cur-

tailed inheritance and recast inheritance rights on

the basis of sexual equality and the nuclear fam-

ily, and legalized abortion. The party-state leader-

ship also proclaimed the long-term goal of the

socialization of the family through the develop-

ment of an extensive network of social services and

communal dining. These measures in part reflected

an ideological commitment to both the liberation

of women and the creation of a socialist society.

But they also were motivated by the political goals

of attracting the support of women for the new

regime and of undermining the sources of opposi-

tion to it believed to lie in patriarchal family struc-

tures and attitudes and in marriage as a religious

institution. In practice, however, the policies added

to the problems of family instability, homelessness,

and child abandonment caused mainly by the harsh

and disruptive effects of several years of war, rev-

olution, civil war, and famine. For this reason,

while welcomed by radical activists and some parts

of the population, Soviet policies with respect to

marriage and the family also provoked consider-

able opposition, especially among women and the

peasantry, who for overlapping but also somewhat

different reasons saw in these policies a threat to

their security and self-identity during a period of

severe dislocation. In important respects, Soviet

propaganda and policies in fact reinforced the self-

image that partly underlay the opposition of

women to its policies by stressing the ideal and du-

ties of motherhood. Yet the direction of Soviet poli-

cies remained consistent through the 1920s, albeit

not without controversy and dissent even within

the party, with these policies being embodied in the

family codes of 1922 and 1926.

The severe social disruptions, strain on re-

sources, and deterioration of already limited social

services caused by the collectivization of agricul-

ture, the rapid development of industry, the aboli-

tion of private trade, and the reconstruction of the

economy between the late 1920s and the outbreak

of war in 1941, however, led to a fundamental shift

in Soviet policies with respect to marriage and the

family. With its priorities now being economic

growth and social stabilization, the Soviet state ide-

alized the socialist family (which in essence closely

resembled the family ideal of prerevolutionary lib-

eral and feminist reformers), which was proclaimed

to be part of the essential foundation of a socialist

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE

899

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

society. A series of laws and new codes enacted be-

tween 1936 and 1944 therefore attempted both to

strengthen marriage and the family and to en-

courage women to give birth more frequently: Di-

vorce was severely restricted, children born out of

wedlock were deprived of any rights with respect

to their father, thus reestablishing illegitimacy of

birth, abortion was outlawed, and a schedule of re-

wards for mothers who bore additional children

was established. Although the goals of women’s

liberation and sexual equality remained official pol-

icy, they were redefined to accommodate a married

woman’s dual burden of employment outside the

home and primary responsibility for domestic

work. Economic necessity in fact compelled most

women to enter the workforce, regardless of their

marital status, with only the wives of the party-

state elite being able to choose not to do so. Despite

the changes in normative ideals and the law, how-

ever, the effects of Soviet social and economic poli-

cies in general and of the difficult material

conditions resulting from them were a further re-

duction in average family size and decline in the

birth rate and the disruption especially of peasant

households, as family members were arrested, mi-

grated to cities in massive numbers, or died as a

result of persecution or famine. The huge losses

sustained by the Soviet population during World

War II gave further impetus to these trends and,

by creating a significant imbalance between men

and women in the marriage-age population, con-

siderably reduced the rate of marriage and compli-

cated the formation of families for several decades

after the war.

The relaxation of political controls on the dis-

cussion of public policy by relevant specialists af-

ter the death of Josef Stalin in 1953 contributed to

another shift in Soviet policies toward marriage and

the family during the mid-1960s. Divorce again be-

came more accessible, fathers could be required to

provide financial support for their children born

out of wedlock, and abortion was re-legalized and,

given the scarcity of reliable alternatives, quickly

became the most common form of birth control

practiced by Russian women. Partly as a result of

these measures, the divorce rate within the Rus-

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE

900

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

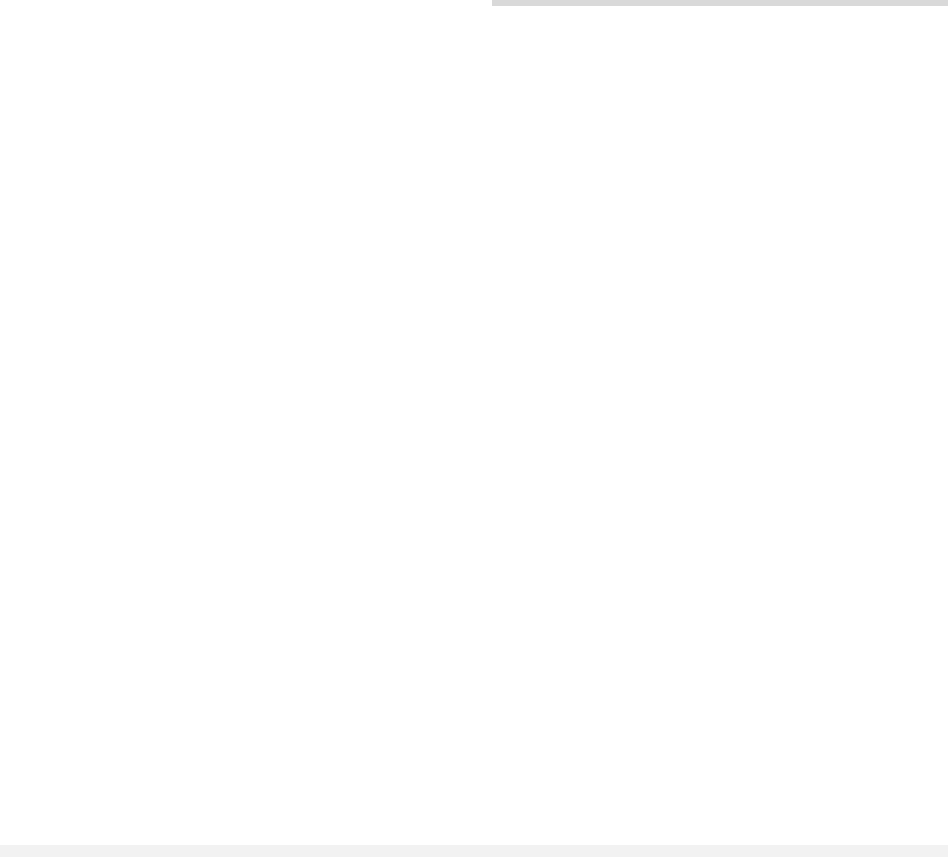

Following Soviet tradition, a wedding party walks to Red Square to have pictures taken. © P

ETER

T

URNLEY

/CORBIS

sian population rose steadily after the mid-1960s,

with more than 40 percent of all marriages ending

in divorce by the 1980s, and the birth rate contin-

ued to decline. But these trends also gained impe-

tus from the growth of the percentage of the

Russian population, women as well as men, re-

ceiving secondary and tertiary education, from the

nearly universal participation of women in the

workforce, from the continued shift of the popu-

lation from the countryside to cities (the Russian

population became predominantly urban only af-

ter the late 1950s), and from the limited availabil-

ity of adequate housing and social services in a

context in which women continued to bear the chief

responsibilities for child-rearing and domestic

work. These latter problems contributed to the

reemergence in the urban population of a modified

form of the multigenerational family, as the prac-

tices of a young couple living with the parents of

one partner while waiting for their own apartment

and of a single parent living especially with his or

usually her mother appear to have increased. In the

countryside, the improvement in the living condi-

tions of the rural population following Stalin’s

death, their inclusion in the social welfare system,

yet the continued out-migration especially of

young males seeking a better life in the city also

led to a decline in family size, as well as to a dis-

proportionately female and aging population,

which affected both the structure of rural families

and the rate of their formation. Nonetheless, the

ideals of the nuclear family, marriage, and natural

motherhood remained firmly in place, both in of-

ficial policy and among the population.

See also: ABORTION POLICY; FAMILY CODE OF 1926; FAM-

ILY CODE ON MARRIAGE, THE FAMILY, AND

GUARDIANSHIP; FAMILY EDICT OF 1944; FAMILY LAWS

OF 1936; FEMINISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clements, Barbara Evans; Engel, Barbara Alpern; and

Worobec, Christine D., eds. (1991). Russia’s Women:

Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Engel, Barbara Alpern. (1994). Between the Fields and the

City: Women, Work, and Family in Russia, 1861–1914.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Freeze, ChaeRan Y. (2002). Jewish Marriage and Divorce

in Imperial Russia. Hanover, NH: Brandeis Univer-

sity Press.

Goldman, Wendy Z. (1993). Women, the State, and Rev-

olution: Soviet Family Policy and Social Life,

1917–1936. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hubbs, Joanna. (1988). Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth

in Russian Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press.

Lapidus, Gail Warshofsky. (1978). Women in Soviet Soci-

ety: Equality, Development, and Social Change. Berke-

ley: University of California Press.

Levin, Eve. (1989). Sex and Society in the World of the Or-

thodox Slavs, 900–1700. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univer-

sity Press.

Marrese, Michelle Lamarche. (2002). A Woman’s King-

dom. Noblewomen and the Control of Property in Rus-

sia, 1700–1861. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Mironov, Boris N., with Eklof, Ben. (2000). The Social

History of Imperial Russia, 1700-1917. 2 vols. Boul-

der, CO: Westview Press.

Pouncy, Carolyn J., ed. and tr. (1994). The “Domostroi”:

Rules for Russian Households in the Time of Ivan the

Terrible. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Ransel, David L., ed. (1978). The Family in Imperial Rus-

sia: New Lines of Historical Research. Urbana: Uni-

versity of Illinois Press.

Ransel, David L. (2000). Village Mothers: Three Generations

of Change in Russia and Tataria. Bloomington: Indi-

ana University Press.

Schlesinger, Rudolf, comp. (1949). Changing Attitudes in

Soviet Russia: The Family in the USSR. London: Rout-

ledge and Paul.

Wagner, William G. (1994). Marriage, Property, and Law

in Late Imperial Russia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Worobec, Christine D. (1991). Peasant Russia: Family and

Community in the Post-Emancipation Period. Prince-

ton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

W

ILLIAM

G. W

AGNER

MARTOV, YULI OSIPOVICH

(1873–1923), founder of Russian social democracy,

later leader of the Menshevik party.

Born Yuli Osipovich Tsederbaum to a middle–

class Jewish family in Constantinople, Yuli Martov

established the St. Petersburg Union of Struggle for

the Liberation of the Working Class with Lenin in

1895. The following year, Martov was sentenced to

three years’ exile in Siberia. After serving his term,

he joined Lenin in Switzerland where they launched

the revolutionary Marxist newspaper Iskra. Martov

broke with Lenin at the Russian Social Democratic

Party’s Second Congress in Brussels in 1903, when

he opposed his erstwhile comrade’s bid for leader-

ship of the party and his demand for a narrow,

MARTOV, YULI OSIPOVICH

901

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

highly centralized party of professional revolution-

aries, instead calling for a broad-based party with

mass membership. Lenin labelled Martov’s sup-

porters the Menshevik (minority) faction; his own

followers constituted the Bolsheviks (majority).

While Lenin proclaimed that socialists should re-

spond to a successful bourgeois revolution by tak-

ing immediate steps to prepare for their own

takeover of government, Martov advocated absten-

tion from power and a strategy of militant oppo-

sition rooted in democratic institutions such as

workers’ soviets, trades unions, cooperatives, or

town and village councils. These “organs of revo-

lutionary self-government” would impel the bour-

geois government to implement political and

economic reform, which would, in time, bring

about conditions favorable to a successful, peaceful,

proletarian revolution. After the outbreak of war,

Martov was a founder of the Zimmerwald move-

ment, which stood for internationalism and “peace

without victory” against both the “defensism” of

some socialist leaders and Lenin’s ambition to trans-

form the imperialist war into a revolutionary civil

war. Martov returned to Russia in mid-May 1917.

His internationalist position and advocacy of mili-

tant opposition to bourgeois government brought

him into open conflict with Menshevik leaders such

as Irakly Tsereteli, who proclaimed “revolutionary

defensism” and had days earlier entered a coalition

with the Provisional Government’s liberal ministers.

The collapse of the first coalition ministry in early

July prompted Martov to declare that the time was

now ripe for the formation of a democratic gov-

ernment of socialist forces. On repeated occasions

in subsequent months, however, his new strategy

was rejected both by coalitionist Mensheviks and by

Bolsheviks intent on seizing power for themselves.

After November 1917, Martov remained a coura-

geous and outspoken opponent of Lenin’s political

leadership and increasingly despotic methods of

rule. Although the Bolsheviks repudiated his efforts

to secure a role for the socialist opposition, Martov

supported the new regime in its struggle against

counterrevolution and foreign intervention. Re-

gardless of this, by 1920 the Menshevik party in

Russia had been destroyed, and most of its leaders

and activists were in prison or exile. In this year

Martov finally left Russia and settled in Berlin. There

he founded and edited the Sotsialistichesky vestnik

(Socialist Courier), a widely influential social de-

mocratic newspaper committed to mobilizing in-

ternational radical opinion against the Bolshevik

dictatorship and halting the spread of Comintern

influence among democratic left-wing movements.

Martov died on April 4, 1923. As his biographer

has written, Martov’s honesty, strong sense of prin-

ciple, and deeply humane nature precluded his suc-

cess as a revolutionary politician, but in opposition

and exile he brilliantly personified social democ-

racy’s moral conscience (Getzler, 1994).

See also: BOLSHEVISM; LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; MENSHE-

VIKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Getzler, Israel. (1994). “Iulii Martov, the Leader Who Lost

His Party in 1917.” Slavonic and East European Re-

view 72:424-439.

Getzler, Israel. (1967). Martov: A Political Biography of a

Russian Social Democrat. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

N

ICK

B

ARON

MARXISM

Karl Marx was born in Trier in Prussia in 1818,

and he died in London in 1883. The general ap-

proach embodied in Marx’s theoretical writings and

his analysis of capitalism may be termed historical

materialism, or the materialist interpretation of

history. Indeed, that approach may well be con-

sidered the cornerstone of Marxism. Marx argued

that the superstructure of society was conditioned

decisively by the productive base of society, so that

the superstructure must always be understood in

relation to the base. The base consists of the mode

of production, in which forces of production (land,

raw materials, capital, and labor) are combined, and

in which relations among people arise, determined

by their relationship to the means of production.

As Marx said in the preface to A Contribution to the

Critique of Political Economy in 1859, “The sum to-

tal of these relations of production constitutes the

economic structure of society, the real foundation,

on which rises a legal and political superstructure

and to which correspond definite forms of social

consciousness. The mode of production of mater-

ial life conditions the social, political, and intellec-

tual life process in general.” Marx considered the

superstructure to include the family, the culture,

the state, philosophy, and religion.

In Marx’s view, all the elements of the super-

structure served the interests of the dominant class

in a society. He saw the class division in any soci-

ety beyond a primitive level of development as re-

MARXISM

902

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY