Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

F. McCarthy, and Georges Vernez. Santa Monica,

CA: Rand.

C

YNTHIA

J. B

UCKLEY

MIKHAILOVSKY, NIKOLAI

KONSTANTINOVICH

(1842–1904), journalist, sociologist, and a revolu-

tionary democrat; leading theorist of agrarian Pop-

ulism.

Born in the Kaluga region to an impoverished

gentry family, and an early orphan, Nikolai

Mikhailovsky studied at the St. Petersburg Mining

Institute, which he was forced to quit in 1863 af-

ter taking part in activities in support of Polish

rebels. From 1860 he published in radical periodi-

cals, held a string of editorial jobs, and experimented

at cooperative profit-sharing entrepreneurship. His

early thought was influenced by Pierre-Joseph

Proudhon, whose work he translated into Russian.

In 1868 he joined the team of Otechestvennye za-

piski (Fatherland Notes), a leading literary journal

headed by Nikolai Nekrasov, where he established

himself with his essay, “What Is Progress?” at-

tacking Social Darwinism, with his work against

the utilitarians, “What Is Happiness?” and other

publications, including “Advocacy of the Emanci-

pation of Women.” After Nekrasov’s death (1877)

Mikhailovsky became one of three coeditors, and

the de facto head of the journal.

Mikhailovsky was the foremost thinker and

author of the mature, or critical stage of populism

(narodnichestvo). While early populists envisioned

Russia bypassing the capitalist stage of develop-

ment and building a just and equitable economic

and societal order on the basis of the peasant com-

mune, Mikhailovsky viewed this scenario as a de-

sirable but increasingly problematic alternative to

capitalist or state-led industrialization. The ethical

thrust of Russian populism found its utmost ex-

pression in his doctrine of binding relationship be-

tween factual truth and normative (moral) truth,

viewed as justice (in Russian, both ideas are ex-

pressed by the word pravda), thus essentially ty-

ing knowledge to ethics.

Together with Pyotr Lavrov, Mikhailovsky laid

the groundwork for Russia’s distinct sociological

tradition by developing the subjective sociology

that was also emphatically normative and ethical

in its basis. His most famous statement read that

“every sociological theory has to start with some

kind of a utopian ideal.” In this vein, he developed

a systematic critique of the positivist philosophy of

knowledge, including the natural science approach

to social studies, while working to familiarize the

Russian audience with Western social and political

thinkers of his age, including John Stuart Mill, Au-

guste Comte, Herbert Spencer, Emile Durkheim,

and Karl Marx. In “What Is Progress?” he argued

for the “struggle for individuality” as a central el-

ement to social action and the indicator of genuine

progress of humanity, as opposed to the Darwin-

ian struggle for survival. According to Mikhailovsky,

in society, unlike in biological nature, it is the en-

vironment that should be adapted to individuals,

not vice versa. On this basis, he attacked the divi-

sion of labor in capitalist societies as a dehuman-

izing social pathology leading to unidimensional

and regressive rather than harmonious develop-

ment of humans and, eventually, to the suppres-

sion of individuality (in contrast to the animal

world, where functional differentiation is a pro-

gressive phenomenon). Thus he introduced a strong

individualist (and, arguably, a libertarian) element

to Russian populist thought, which had tradition-

ally emphasized collectivism. He sought an alter-

native to the division of labor in the patterns of

simple cooperation among peasants. He also

worked toward a distinct theory of social change,

questioning Eurocentric linear views of progress,

and elaborated a dual gradation of types and

levels of development (that is, Russia for him rep-

resented a higher type but a lower level of devel-

opment than industrialized capitalist countries, and

he thought it necessary to preserve this higher, or

communal, type while striving to move to a higher

level). In “Heroes and the Crowd” (1882), he pro-

vided important insights into mass psychology and

the nature of leadership.

Under the impact of growing political repres-

sion, Mikhailovsky evolved from liberal critique of

the government during the 1860s through short-

lived hopes for a pan-Slav liberation movement

(1875–1876) to clandestine cooperation with the

People’s Will Party, thus broadening the purely so-

cial goals of the original populism to embrace a po-

litical revolution (while at the same time distancing

himself from the morally unscrupulous figures

connected to populism, such as Sergei Nechayev).

He authored articles for underground publications,

and after the assassination of Alexander II (1881)

took part in compiling the address of the People’s

Will’s Executive Committee to Alexander III, an at-

tempt to position the organization as a negotiating

MIKHAILOVSKY, NIKOLAI KONSTANTINOVICH

923

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

partner of the authorities. In the subsequent crack-

down on the movement, Mikhailovsky was banned

from St. Petersburg (1882), and Otechestvennye za-

piski was shut down (1884). Only in 1884 was he

able to return to an editorial position by informally

taking over the journal Russkoye bogatstvo (Russian

Wealth). He then emerged as an influential critic of

the increasingly popular Marxism, which he saw

as converging with top-down industrialization

policies of the government in its disdain for and ex-

ploitative approach to the peasantry. Simultane-

ously, he polemicized against Tolstovian anarchism

and anti-intellectualism. In spite of the ideological

hegemony of Marxists at the turn of the century,

Mikhailovsky’s writings were highly popular

among the democratic intelligentsia and provided

the conceptual basis for the neo-populist revival,

represented by the Socialist Revolutionary and the

People’s Socialist parties in the 1905 and 1917 rev-

olutions. Moreover, his work resonates with sub-

sequent Western studies in the peasant-centered

“moral economy” of peripheral countries.

See also: INTELLIGENTSIA; JOURNALISM; MARXISM;

NEKRASOV, NIKOLAI ALEXEYEVICH; POPULISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Billington, J.H. (1958). Mikhailovsky and Russian Pop-

ulism. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Edie, James M.; Scanlan, James P.; and Zeldin, M.B., eds.

(1965). Russian Philosophy, vol. 2. Chicago, IL:

Quadrangle Books.

Ivanov-Razumnik, R.I. (1997). Istoria russkoi obshch-

estvennoi mysli. Vol. 2. Moscow: Respublika, Terra.

pp. 228-302.

Ulam, Adam B. (1977). In the Name of the People: Prophets

and Conspirators in Prerevolutionary Russia. New

York: Putnam.

Venturi, Franco. (2001). Roots of Revolution, revised ed.,

tr. Francis Haskell. London: Phoenix Press.

Walicki, A. (1969). The Controversy Over Capitalism: Stud-

ies in the Social Philosophy of the Russian Populists.

Oxford: Clarendon Press.

D

MITRI

G

LINSKI

MIKHALKOV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH

(b. 1945), film director, actor.

Nikita Mikhalkov is the best-known Russian

director of the late-Soviet and post-Soviet period.

Mikhalkov was born in Moscow to a family

of accomplished painters, writers, and arts ad-

ministrators. His father was chief of the Soviet

Writers’ Union, and his brother, Andrei Mikhalkov-

Konchalovsky, is also a successful director. Mikhal-

kov first came to national and international

attention with his film Slave of Love (1976), which

depicts the last days of prerevolutionary popular

filmmaking. He made several more films about

late-nineteenth-century elite culture, including Un-

finished Piece for Player Piano (1977), Oblomov

(1980), and Dark Eyes (1987). Five Evenings (1978)

is a beautifully photographed, finely etched treat-

ment of love and loss set just after World War II.

Urga (aka Close to Eden, 1992) is a powerful por-

trait of economic transformation and cultural en-

counter on the Russian-Mongolian border. Anna,

6–18 (1993) is a series of interviews with the di-

rector’s daughter, which highlights the difficulties

of growing up in late-communist society. Burnt by

the Sun (1994), which won a U.S. Academy Award

for best foreign language film, treats the compli-

cated personal politics of the Stalinist period. The

Barber of Siberia (1999) is a sprawling romantic epic

with Russians and Americans in Siberia—an ex-

pensive multinational production which failed to

win an audience. All of Mikhalkov’s films are vi-

sually rich; he has a deft touch for lightening his

dramas with comedy, and his characterizations can

be subtle and complex.

Mikhalkov has also had a successful career as

an actor. Physically imposing, he often plays char-

acters who combine authority and power with

poignancy or sentimentality. During the late

1990s, Mikhalkov became the president of the

Russian Culture Fund and the chair of the Union

of Russian Filmmakers.

See also: MOTION PICTURES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beumers, Bergit. (2000). Burnt By the Sun. London: I.B.

Tauris.

Horton, Andrew, and Brashinsky, Michael. (1992). The

Zero Hour. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lawton, Anna. (1992). Kinoglasnost: Soviet Cinema in Our

Time. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shalin, Dmitri N., ed. Russian Culture at the Crossroads:

Paradoxes of Postcommunist Consciousness. Boulder,

CO: Westview.

J

OAN

N

EUBERGER

MIKHALKOV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH

924

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

MIKOYAN, ANASTAS IVANOVICH

(1895–1978), Communist Party leader and gov-

ernment official.

Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan occupied the sum-

mits of Soviet political and governmental life for

more than five decades. One of Stalin’s comrades,

he was a political survivor. Armenian by birth,

Mikoyan joined the Bolsheviks in 1915, playing a

leading role in the Caucasus during the civil war

(1918–1920). In 1922 he was elected to the Com-

munist Party’s Central Committee, by which time

he was already working confidentially for Josef

Stalin. After Vladimir Lenin’s death (1924) he

staunchly supported Stalin’s struggle against the

Left Opposition. His loyalty was rewarded in 1926

when he became the youngest commissar and

Politburo member. Appointed commissar of food

production in 1934, he introduced major innova-

tions in this area. By 1935 he was a full member

of the Politburo. While not an aggressive advocate

of the Great Terror (1937–1938), Mikoyan was re-

sponsible for purges in his native Armenia. In 1942,

after the German invasion, he was appointed to the

State Defense Committee, with responsibility for

military supplies. After Stalin’s death (1953) he

proved a loyal ally of Nikita Khrushchev, the only

member of Stalin’s original Politburo to support

him in his confrontation with the Stalinist Anti-

Party Group (1957). Mikoyan went on to play a

crucial role in the Cuban missile crisis (1962), me-

diating between Khrushchev, U.S. president John

F. Kennedy, and Cuban leader Fidel Castro, whom

he persuaded to accept the withdrawal of Soviet

missiles from Cuba. He was appointed head of gov-

ernment in July 1964, three months before sign-

ing the decree dismissing Khrushchev as party first

secretary. Under Leonid Brezhnev he gradually re-

linquished his roles in party and government in fa-

vor of writing his memoirs, finally retiring in 1975.

See also: ANTI-PARTY GROUP; ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS;

CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS; LEFT OPPOSITION; PURGES, THE

GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Medvedev, Roy. (1984). All Stalin’s Men. (1984). Garden

City, NY: Anchor Press.

Taubman, William; Khrushchev, Sergei; and Gleason,

Abbott, eds. (2000). Nikita Khrushchev. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press.

R

OGER

D. M

ARKWICK

MILITARY ART

Military art is the theory and practice of preparing

and conducting military actions on land, at sea, and

within the global aerospace envelope.

Historically, Russian military theorists held

that the primary function of military art was at-

tainment of victory over an adversary with the

least expenditure of forces, resources, and time.

This postulation stressed a well-developed sense of

intent that would link the logic of strategy with

the purposeful design and execution of complex

military actions. By the end of the nineteenth cen-

tury, Russian military theorists accepted the con-

viction that military art was an expression of

military science, which they viewed as a branch of

the social sciences with its own laws and discipli-

nary integrity. Further, they subscribed to the idea,

exemplified by Napoleon, that military art con-

sisted of two primary components, strategy and

tactics. Strategy described movements of main

military forces within a theater of war, while

tactics described what occurred on the battlefield.

However, following the Russo-Japanese War of

1904–1905, theorists gradually modified their

views to accommodate the conduct of operations

in themselves, or operatika, as a logical third com-

ponent lying between—and linking—strategy and

tactics. This proposition further evolved during the

1920s and 1930s, thanks primarily to Alexander

Svechin, who lent currency to the term “opera-

tional art” (operativnoye iskusstvou) as a replacement

for operatika, and to Vladimir Triandafillov, who

analyzed the nature of modern military operations

on the basis of recent historical precedent. Subse-

quently, the contributions of other theorists, in-

cluding Mikhail Tukhachevsky, Alexander Yegorov,

and Georgy Isserson, along with mechanization

of the Red Army and the bitter experience of the

Great Patriotic War, contributed further to the

Soviet understanding of modern military art. How-

ever, the theoretical development of strategy lan-

guished under Josef Stalin, while the advent of

nuclear weapons at the end of World War II called

into question the efficacy of operational art. Dur-

ing much of the Nikita Khrushchev era, a nuclear-

dominated version of strategy held near-complete

sway in the realm of military art. Only in the mid-

1960s did Soviet military commentators begin to

resurrect their understanding of operational art to

correspond with the theoretical necessity for con-

ducting large-scale conventional operations under

conditions of nuclear threat. During the 1970s and

MILITARY ART

925

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

1980s emphasis on new reconnaissance systems

and precision-guided weaponry as parts of an on-

going revolution in military affairs further chal-

lenged long-held convictions about traditional

boundaries and linkages among strategy, opera-

tional art, and tactics. Further, U.S. combat expe-

rience during the Gulf War in 1990–1991 and again

in Afghanistan during 2001 clearly challenged con-

ventional notions about the relationships in con-

temporary war between time and space, mass and

firepower, and offense and defense. Some theorists

even began to envision a new era of remotely

fought or no-contact war (bezkontaknaya voynau)

that would dominate the future development of all

facets of military art.

See also: MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA; MILITARY, SOVIET AND

POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Menning, Bruce W. (1997). “Operational Art’s Origins.”

Military Review 76(5):32-47.

Svechin, Aleksandr A. (1992). Strategy, ed. Kent D. Lee.

Minneapolis: East View Publications.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

MILITARY DOCTRINE

In late Imperial Russia, a common basis for joint

military action; in the Soviet Union and the Russ-

ian Federation, an assertion of military posture and

policy.

The Soviet and Russian understanding of mil-

itary doctrine is often a source of confusion because

other societies usually subscribe to a narrower de-

finition. For most Western military and naval es-

tablishments, doctrine typically consists of the

distilled wisdom that governs the actual employ-

ment of armed forces in combat. At its best, this

wisdom constitutes a constantly evolving intellec-

tual construct that owes its origins and develop-

ment to a balanced understanding of the complex

interplay among changing technology, structure,

theory, and combat experience.

In contrast, doctrine in its Soviet and Russian

variants evolved early to reflect a common under-

standing of the state’s larger defense requirements.

The issue first surfaced after 1905, when Russian

military intellectuals debated the necessity for a

“unified military doctrine” that would impart ef-

fective overall structure and direction to war prepa-

rations. In a more restrictive perspective, the same

doctrine would also define the common intellectual

foundations of field service regulations and the

terms of cooperation between Imperial Russia’s

army and navy. In 1912, Tsar Nicholas II himself

silenced discussion, proclaiming, “Military doctrine

consists of doing everything that I order.”

A different version of the debate resurfaced

soon after the Bolshevik triumph in the civil war.

Discussion ostensibly turned on a doctrinal vision

for the future of the Soviet military establishment,

but positions hardened and quickly assumed polit-

ical overtones. War Commissar Leon Trotsky held

that any understanding of doctrine must flow from

future requirements for world revolution. Others,

including Mikhail V. Frunze, held that doctrine

must flow from the civil war experience, the na-

ture of the new Soviet state, and the needs and

character of the Red Army. Frunze essentially en-

visioned a concept of preparation for future war

shaped by class relations, external threat, and the

state’s economic development.

Frunze’s victory in the debate laid the founda-

tions for a subsequent definition of Soviet and later

Russian military doctrine that has remained rela-

tively constant. Military doctrine came to be un-

derstood as “a system of views adopted by a given

state at a given time on the goals and nature of

possible future war and the preparation of the

armed forces and the country for it, and also the

methods of waging it.” Because of explicit linkages

between politics and war, this version of military

doctrine always retained two aspects, the political

(or sociopolitical) and the military-technical. Thanks

to rapid advances in military technology, the lat-

ter aspect sometimes witnessed abrupt change.

However, until the advent of Mikhail S. Gorbachev

and perestroika, the political aspect, which defined

the threat and relations among states, remained rel-

atively static.

The disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991

led to a recurring redefinition of the twin doctrinal

aspects that emphasized both Russia’s diminished

great-power status and the changing nature of the

threat. Nuclear war became less imminent, mili-

tary operations more complex, and the threat both

internal and external. Whatever the calculus, the

terms of expression and discussion continued to re-

flect the unique legacy that shaped Imperial Russ-

ian and Soviet notions of military doctrine.

MILITARY DOCTRINE

926

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: FRUNZE, MIKHAIL VASILIEVICH; MILITARY, IMPE-

RIAL ERA; MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET; TROT-

SKY, LEON DAVIDOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frank, Willard C., and Gillette, Phillip S., eds. (1992). So-

viet Military Doctrine from Lenin to Gorbachev,

1915–1991. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Garthoff, Raymond L. (1953). Soviet Military Doctrine.

Glencoe, IL: Free Press..

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

MILITARY-ECONOMIC PLANNING

In the world wars of the twentieth century, it was

as important to mobilize the economy to supply

soldiers’ rations and equipment as it was to enlist

the population as soldiers. Military-economic plan-

ning took root in the Soviet Union, as elsewhere,

after World War I. The scope of the plans that pre-

pared the Soviet economy for war continues to be

debated. Some argue that war preparation was a

fundamental objective influencing every aspect of

Soviet peacetime economic policy; there were no

purely civilian plans, and everything was milita-

rized to some degree. Others see military-economic

planning more narrowly as the specialized activity

of planning and budgeting for rearmament, which

had to share priority with civilian economic goals.

The framework for military-economic plan-

ning was fixed by a succession of high-level gov-

ernment committees: the Council for Labor and

Defense (STO), the Defense Committee, and, in the

postwar period, the Military-Industrial Commis-

sion (VPK). The armed forces general staff carried

on military-economic planning in coordination

with the defense sector of the State Planning Com-

mission (Gosplan). Gosplan’s defense sector was

established on the initiative of the Red Army com-

mander, Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who pioneered the

study of future war and offensive operations as-

sociated with the concept of deep battle. To sup-

port this he advocated ambitious plans for the

large-scale production of combat aircraft and mo-

torized armor. Tukhachevsky crossed swords at

various times with Josef V. Stalin, Vyacheslav

Molotov, and Kliment Voroshilov. The military-

economic plans were less ambitious than he hoped,

and also less coherent: Industry did not reconcile

its production plans beforehand with the army’s

procurement plan, and their interests often diverged

over the terms of plans and contracts to supply

equipment. To overcome this Tukhachevsky

pressed to bring the management of defense pro-

duction under military control, but he was frus-

trated in this too. His efforts ended with his arrest

and execution in 1937.

Military-economic plans required every min-

istry and workplace to adopt a mobilization plan

to be implemented in the event of war. How effec-

tive this was is difficult to evaluate, and the mobi-

lization plans adopted before World War II appear

to have been highly unrealistic by comparison with

wartime outcomes. Despite this, the Soviet transi-

tion to a war economy was successful; the fact that

contingency planning and trial mobilizations were

practiced at each level of the prewar command sys-

tem may have contributed more to this than their

detailed faults might suggest.

During World War II the task was no longer

to prepare for war but to fight it, and so the dis-

tinction between military-economic planning and

economic planning in general disappeared for a

time. It reemerged after the war when Stalin began

bringing his generals back into line, and the secu-

rity organs, not the military, took the leading role

in organizing the acquisition of new atomic and

aerospace technologies. Stalin’s death and the de-

motion of the organs allowed a new equilibrium

to emerge under Dmitry Ustinov, minister of the

armament industry since June 1941; Ustinov went

on to coordinate the armed forces and industry

from a unique position of influence and privilege

under successive Soviet leaders until his own death

in 1984. It symbolized his coordinating role that

he assumed the military rank of marshal in 1976.

See also: GOSPLAN; TUKHACHEVSKY, MIKHAIL NIKOLAYE-

VICH; USTINOV, DMITRY FEDOROVICH; WAR ECON-

OMY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barber, John, and Harrison, Mark, eds. (2000). The Soviet

Defence-Industry Complex from Stalin to Khrushchev.

Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Harrison, Mark (2001). “Providing for Defense.” In Be-

hind the Façade of Stalin’s Command Economy: Evidence

from the Soviet State and Party Archives, ed. Paul R.

Gregory. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Samuelson, Lennart. (2000). Plans for Stalin’s War Ma-

chine: Tukhachevskii and Military-Economic Planning,

1925–1941. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

M

ARK

H

ARRISON

MILITARY-ECONOMIC PLANNING

927

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA

Measured by large outcomes, the Imperial Russian

military establishment evolved through two dis-

tinct stages. From the era of Peter the Great through

the reign of Alexander III, the Russian army and

navy fought, borrowed, and innovated their way

to more successes than failures. With the major ex-

ception of the Crimean War, Russian ground and

naval forces largely overcame the challenges and

contradictions inherent in diverse circumstances

and multiple foes to extend and defend the limits

of empire. However, by the time of Nicholas II, sig-

nificant lapses in leadership and adaptation spawned

the kinds of repetitive disaster and fundamental dis-

affection that exceeded the military’s ability to re-

cuperate.

THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ARMY

The Imperial Russian Army and Navy owed their

origins to Peter I, although less so for the army

than the navy. The army’s deeper roots clearly lay

with Muscovite precedent, especially with Tsar

Alexei Mikhailovich’s European-inspired new regi-

ments of foreign formation. The Great Reformer

breathed transforming energy and intensity into

these and other precedents to fashion a standing

regular army that by 1725 counted 112,000 troops

in two guards, two grenadier, forty-two infantry,

and thirty-three dragoon regiments, with sup-

porting artillery and auxiliaries. To serve this es-

tablishment, he also fashioned administrative,

financial, and logistical mechanisms, along with a

rational rank structure and systematic officer and

soldier recruitment. With an admixture of foreign-

ers, the officer corps came primarily from the Russ-

ian nobility, while soldiers came from recruit levies

against the peasant population.

Although Peter’s standing force owed much to

European precedent, his military diverged from

conventional patterns to incorporate irregular cav-

alry levies, especially Cossacks, and to evolve a mil-

itary art that emphasized flexibility and practicality

for combating both conventional northern Euro-

pean foes and less conventional steppe adversaries.

After mixed success against the Tatars and Turks

at Azov in 1695–1696, and after a severe reverse

at Narva (1700) against the Swedes at the outset

of the Great Northern War, Peter’s army notched

important victories at Dorpat (1704), Lesnaya

(1708), and Poltava (1709). After an abrupt loss in

1711 to the Turks on the Pruth River, Peter dogged

his Swedish adversaries until they came to terms

at Nystadt in 1721. Subsequently, Peter took to the

Caspian basin, where during the early 1720s his

Lower (or Southern) Corps campaigned as far south

as Persia.

After Peter’s death, the army’s fortunes waned

and waxed, with much of its development charac-

terized by which aspect of the Petrine legacy seemed

most politic and appropriate for time and circum-

stance. Under Empress Anna Ioannovna, the army

came to reflect a strong European, especially Pruss-

ian, bias in organization and tactics, a bias that

during the 1730s contributed to defeat and indeci-

sion against the Tatars and Turks. Under Empress

Elizabeth Petrovna, the army reverted partially to

Petrine precedent, but retained a sufficiently strong

European character to give good account for itself

in the Seven Years’ War. Although in 1761 the mil-

itary-organizational pendulum under Peter III again

swung briefly and decisively in favor of Prussian-

inspired models, a palace coup in favor of his wife,

who became Empress Catherine II, ushered in a

lengthy period of renewed military development.

During Catherine’s reign, the army fought two

major wars against Turkey and its steppe allies to

emerge as the largest ground force in Europe. Three

commanders were especially responsible for bring-

ing Russian military power to bear against elusive

southern adversaries. Two, Peter Alexandrovich

Rumyantsev and Alexander Vasilievich Suvorov,

were veterans of the Seven Years War, while the

third, Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin, was a

commander and administrator of great intellect, in-

fluence, and organizational talent. During Cather-

ine’s First Turkish War (1768–1774), Rumyantsev

successfully employed flexible tactics and simpli-

fied Russian military organization to win signifi-

cant victories at Larga and Kagul (both 1770).

Suvorov, meanwhile, defeated the Polish Confeder-

ation of Bar, then after 1774 campaigned in the

Crimea and the Nogai steppe. At the same time,

regular army formations played an important role

in suppressing the Pugachev rebellion (1773–1775).

During Catherine’s Second Turkish War

(1787–1792), Potemkin emerged as the impresario

of final victory over the Porte for hegemony over

the northern Black Sea littoral, while Suvorov

emerged as perhaps the most talented Russian field

commander of all time. Potemkin inherently un-

derstood the value of irregular cavalry forces in the

south, and he took measures to regularize Cossack

service and bring them more fully under Russian

military authority, or failing that, to abolish re-

MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA

928

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

calcitrant Cossack hosts. Following Rumyantsev’s

precedent, he also lightened and multiplied the

number of light infantry and light cavalry forma-

tions, while emphasizing utility and practicality in

drill and items of equipment. In the field, Suvorov

further refined Rumyantsev’s tactical innovations

to emphasize “speed, assessment, attack.” Su-

vorov’s battlefield successes, together with the con-

quest of Ochakov (1788) and Izmail (1790) and

important sallies across the Danube, brought Rus-

sia favorable terms at Jassy (1792). Even as war

raged in the south, the army in the north once

again defeated Sweden (1788–1790), then in

1793–1794 overran a rebellious Poland, setting the

stage for its third partition.

Under Paul I, the army chaffed under the im-

position of direct monarchical authority, the more

so because it brought another brief dalliance with

Prussian military models. Suvorov was temporar-

ily banished, but was later recalled to lead Russian

forces in northern Italy as part of the Second Coali-

tion against revolutionary France. In 1799, despite

Austrian interference, Suvorov drove the French

from the field, then brilliantly extricated his forces

from Italy across the Alps. The eighteenth century

closed with the army a strongly entrenched feature

of Russian imperial might, a force to be reckoned

with on both the plains of Europe and the steppes

of Eurasia.

THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY NAVY

In contrast with the army, Muscovite precedent af-

forded scant inspiration for the Imperial Russian

Navy, the origins of which clearly lay with Peter the

Great. Enamored with the sea and sailing ships, Pe-

ter borrowed from foreign technology and expertise

initially to create naval forces on both the Azov and

Baltic Seas. Although the Russian navy would al-

ways remain “the second arm” for an essentially

continental power, sea-going forces figured promi-

nently in Peter’s military successes. In both the south

and north, his galley fleets supported the army in

riverine and coastal operations, then went on to win

important Baltic victories over the Swedes, most no-

tably at Gangut/Hanko (1714). Peter also developed

an open-water sailing capability, so that by 1724

his Baltic Fleet numbered 34 ships-of-the-line, in ad-

dition to numerous galleys and auxiliaries. Smaller

flotillas sailed the White and Caspian Seas.

More dependent than the army on rigorous and

regular sustenance and maintenance, the Imperial

Russian Navy after Peter languished until the era

of Catherine II. She appointed her son general ad-

miral, revitalized the Baltic Fleet, and later estab-

lished Sevastopol as a base for the emerging Black

Sea Fleet. In 1770, during the Empress’ First Turk-

ish War, a squadron under Admiral Alexei Grig-

orievich Orlov defeated the Turks decisively at

Chesme. During the Second Turkish War, a rudi-

mentary Black Sea Fleet under Admiral Fyedor

Fyedorovich Ushakov frequently operated both in-

dependently and in direct support of ground forces.

The same ground–sea cooperation held true in the

Baltic, where Vasily Yakovlevich Chichagov’s fleet

also ended Swedish naval pretensions. Meanwhile,

in 1799 Admiral Ushakov scored a series of

Mediterranean victories over the French, before the

Russians withdrew from the Second Coalition.

THE ARMY AND NAVY IN THE FIRST

HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

At the outset of the century, Alexander I inherited

a sizeable and unaffordable army, many of whose

commanders were seasoned veterans. After insti-

tuting a series of modest administrative reforms for

efficiency and economy, including the creation of

a true War Ministry, the Tsar in 1805 plunged into

the wars of the Third Coalition. For all their expe-

rience and flexibility, the Russians with or without

the benefit of allies against Napoleon suffered a se-

ries of reverses or stalemates, including Austerlitz

(1805), Eylau (1807), and Friedland (1807). After

the ensuing Tilsit Peace granted five years’ respite,

Napoleon’s Grand Armée invaded Russia in 1812.

Following a fighting Russian withdrawal into the

interior, Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov in Septem-

ber gave indecisive battle at Borodino, followed by

another withdrawal to the southeast that uncov-

ered Moscow. When the French quit Moscow in

October, Kutuzov pursued, reinforced by swarms

of partisans and Cossacks, who, together with star-

vation and severe cold, harassed the Grand Armée

to destruction. In 1813, the Russian army fought

in Germany, and in 1814 participated in the coali-

tion victory at Leipzig, followed by a fighting en-

try into France and the occupation of Paris.

The successful termination of the Napoleonic

wars still left Alexander I with an outsized and un-

affordable military establishment, but now with

the addition of disaffected elements within the of-

ficer corps. While some gentry officers formed se-

cret societies to espouse revolutionary causes, the

tsar experimented with the establishment of set-

tled troops, or military colonies, to reduce mainte-

nance costs. Although these colonies were in many

ways only an extension of the previous century’s

MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA

929

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

experience with military settlers on the frontier,

their widespread application spawned much dis-

content. After Alexander I’s death, unrest and con-

spiracy led to an attempted military coup in

December 1825.

Tsar Nicholas I energetically suppressed the so-

called Decembrist rebellion, then imposed parade-

ground order. His standing army grew to number

one million troops, but its outdated recruitment

system and traditional support infrastructure

eventually proved incapable of meeting the chal-

lenges of military modernization. Superficially, the

army was a model of predictable routine and harsh

discipline, but its inherent shortcomings, including

outmoded weaponry, incapacity for rapid expan-

sion, and lack of strategic mobility, led inexorably

to Crimean defeat. The army was able to subdue

Polish military insurrectionists (1830–1831) and

Hungarian revolutionaries (1848), and successfully

fight Persians and Turks (1826–1828, 1828–1829),

but in the field it lagged behind its more modern

European counterparts. Fighting from 1854 to

1856 against an allied coalition in the Crimea, the

Russians suffered defeat at Alma, heavy losses at

Balaklava and Inkerman, and the humiliation of

surrender at Sevastopol. Only the experience of ex-

tended warfare in the Caucasus (1801–1864) af-

forded unconventional antidote to the conventional

“paradomania” of St. Petersburg that had so thor-

oughly inspired Crimean defeat. Thus, the moun-

tains replaced the steppe as the southern pole in an

updated version of the previous century’s north-

south dialectic.

During the first half of the nineteenth century,

the navy, too, experienced its own version of the

same dialectic. For a brief period, the Russian navy

under Admiral Dmity Nikolayevich Senyavin ha-

rassed Turkish forces in the Aegean, but following

Tilsit, the British Royal Navy ruled in both the Baltic

and the Mediterranean. In 1827, the Russians joined

with the British and French to pound the Turks at

Navarino, but in the north, the Baltic Fleet, like the

St. Petersburg military establishment, soon degen-

erated into an imperial parading force. Only on the

Black Sea, where units regularly supported Russian

ground forces in the Caucasus, did the Navy reveal

any sustained tactical and operational acumen.

However, this attainment soon proved counterpro-

ductive, for Russian naval victory in 1853 over the

Turks at Sinope drew the British and French to the

Turkish cause, thus setting the stage for allied in-

tervention in the Crimea. During the Crimean War,

steam and screw-driven allied vessels attacked at will

in both the north and south, thereby revealing the

essentially backwardness of Russia’s sailing navy.

THE ARMY AND NAVY DURING

THE SECOND HALF OF THE

NINETEENTH CENTURY

Alexander II’s era of the Great Reforms marked an

important watershed for both services. In a series

of reforms between 1861 and 1874, War Minister

Dmitry Alexeyevich Milyutin created the founda-

tions for a genuine cadre- and reserve-based ground

force. He facilitated introduction of a universal ser-

vice obligation, and he rearmed, reequipped, and re-

deployed the army to contend with the gradually

emerging German and Austro-Hungarian threat

along the Empire’s western frontier. In 1863–1864

the army once again suppressed a Polish rebellion,

while in the 1860s and 1870s small mobile forces

figured in extensive military conquests in Central

Asia. War also flared with Turkey in 1877–1878,

during which the army, despite a ragged beginning,

inconsistent field leadership, and inadequacies in lo-

gistics and medical support, acquitted itself well,

especially in a decisive campaign in the European

theater south of the Balkan ridge. Similar circum-

stances governed in the Transcausus theater, where

the army overcame initial setbacks to seize Kars and

carry the campaign into Asia Minor.

Following the war of 1877–1878, planning and

deployment priorities wedded the army more

closely to the western military frontier and espe-

cially to peacetime deployments in Russian Poland.

With considerable difficulty, Alexander III presided

over a limited force modernization that witnessed

the adoption of smokeless powder weaponry and

changes in size and force structure that kept the

army on nearly equal terms with its two more sig-

nificant potential adversaries, Imperial Germany

and Austria-Hungary. At the same time, the end

of the century brought extensive new military

commitments to the Far East, both to protect ex-

panding imperial interests and to participate in

suppression of the Boxer Rebellion (1900).

The same challenges of force modernization

and diverse responsibilities bedeviled the navy, per-

haps more so than the army. During the 1860s

and 1870s, the navy made the difficult transition

from sail to steam, but thereafter had to deal with

increasingly diverse geostrategic requirements that

mandated retention of naval forces in at least four

theaters (Baltic, Northern, Black Sea, and Pacific),

none of which were mutually supporting. Simul-

taneously, the Russian Admiralty grappled with is-

MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA

930

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

sues of role and identity, pondering whether the

navy’s primary mission in war lay either with

coastal defense and commerce raiding or with at-

tainment of true “blue water” supremacy in the

tradition of Alfred Thayer Mahan and his Russian

navalist disciples. Rationale notwithstanding, by

1898 Russia possessed Europe’s third largest navy

(nineteen capital ships and more than fifty cruis-

ers), thanks primarily to the ship-building pro-

grams of Alexander III.

THE ARMY AND NAVY OF NICHOLAS II

Under Russia’s last tsar, the army went from defeat

to disaster and despair. Initially overcommitted and

split by a new dichotomy between the Far East and

the European military frontier, the army fared

poorly in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905.

Poor strategic vision and even worse battlefield ex-

ecution in a Far Eastern littoral war brought defeat

because Russia failed to bring its overwhelming re-

sources to bear. While the navy early ceded the ini-

tiative and command of the sea to the Japanese,

Russian ground force buildups across vast distances

were slow. General Adjutant Alexei Nikolayevich

Kuropatkin and his subordinates lacked the capac-

ity either to fight expert delaying actions or to mas-

ter the complexities of meeting engagements that

evolved into main battles and operations. Tethered

to an 8-thousand-kilometer-long line of commu-

nications, the army marched through a series of

reverses from the banks of the Yalu (May 1904) to

the environs of Mukden (February–March 1905).

Although the garrison at Port Arthur retained the

capacity to resist, premature surrender of the

fortress in early 1905 merely added to Russian hu-

miliation.

The Imperial Russian Navy fared even worse.

Except for Stepan Osipovich Makarov, who was

killed early, Russian admirals in the Far East pre-

sented a picture of indolence and incompetence. The

Russian Pacific Squadron at Port Arthur made sev-

eral half-hearted sorties, then was bottled up at its

base by Admiral Togo, until late in 1904 when

Japanese siege artillery pounded the Squadron

to pieces. When the tsar sent his Baltic Fleet (re-

christened the Second Pacific Squadron) to the Far

East, it fell prey to the Japanese at Tsushima (May

1905) in a naval battle of annihilation. In all, the

tsar lost fifteen capital ships in the Far East, the

backbone of two battle fleets.

The years between 1905 and 1914 witnessed

renewal and reconstruction, neither of which suf-

ficed to prepare the tsar’s army and navy for World

War I. Far Eastern defeat fueled the fires of the Rev-

olution of 1905, and both services witnessed mu-

tinies within their ranks. Once the dissidents were

weeded out, standing army troops were employed

liberally until 1907 to suppress popular disorder.

By 1910, stability and improved economic condi-

tions permitted General Adjutant Vladimir Alexan-

drovich Sukhomlinov’s War Ministry to undertake

limited reforms in the army’s recruitment, organi-

zation, deployment, armament, and supply struc-

ture. More could have been done, but the navy

siphoned off precious funds for ambitious ship-

building programs to restore the second arm’s

power and prestige. The overall objective was to

prepare Russia for war with the Triple Alliance. Ob-

session with the threat opposite the western military

frontier gradually eliminated earlier dichotomies

and subsumed all other strategic priorities.

The outbreak of hostilities in 1914 came too

soon for various reform and reconstruction pro-

jects to bear full fruit. Again, the Russians suffered

from strategic overreach and stretched their mili-

tary and naval resources too thin. Moreover, mil-

itary leaders failed to build sound linkages between

design and application, between means and objec-

tives, and between troops and their command in-

stances. These and other shortcomings, including

MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA

931

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

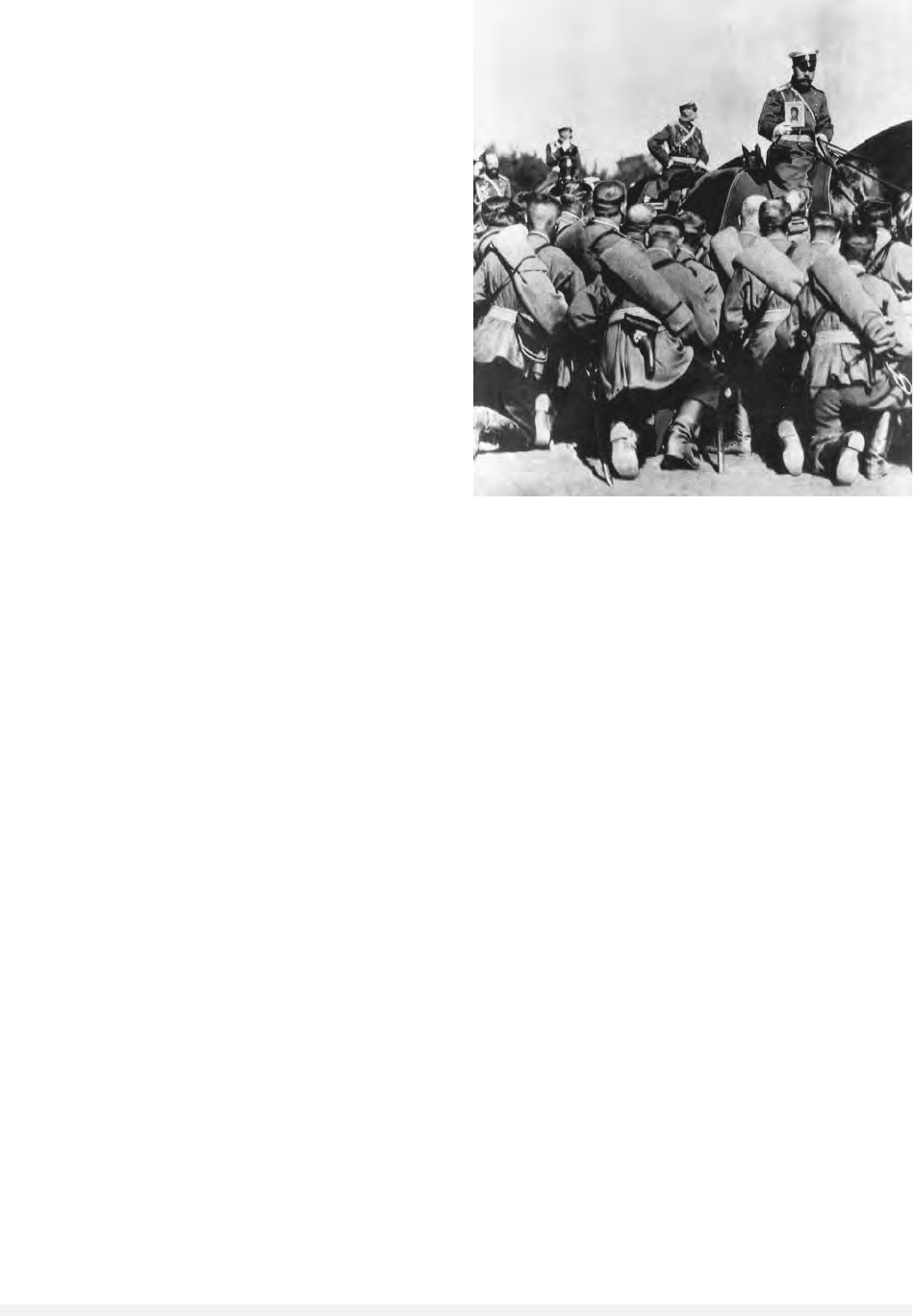

Nicholas II presents an icon to his troops as they depart for

World War I. © SOVFOTO

an inadequate logistics system and the regime’s in-

ability fully to mobilize the home front to support

the fighting front, proved disastrous. Thus, the

Russians successfully mobilized 3.9 million troops

for a short war of military annihilation, but early

disasters in East Prussia at Tannenberg and the Ma-

surian Lakes, along with a stalled offensive in Gali-

cia, inexorably led to a protracted war of attrition

and exhaustion. In 1915, when German offensive

pressure caused the Russian Supreme Command to

shorten its front in Russian Poland, withdrawal

turned into a costly rout. One of the few positive

notes came in 1916, when the Russian Southwest

Front under General Alexei Alexeyevich Brusilov

launched perhaps the most successful offensive of

the entire war on all its fronts. Meanwhile, a navy

still not fully recovered from 1904–1905 generally

discharged its required supporting functions. In the

Baltic, it laid mine fields and protected approaches

to Petrograd. In the Black Sea, after initial difficul-

ties with German units serving under Turkish col-

ors, the fleet performed well in a series of support

and amphibious operations.

Ultimately, a combination of seemingly end-

less bloodletting, war-weariness, governmental in-

efficiency, and the regime’s political ineptness

facilitated the spread of pacifist and revolutionary

sentiment in both the army and navy. By the be-

ginning of 1917, sufficient malaise had set in to

render both services incapable either of consistent

loyalty or of sustained and effective combat oper-

ations. In the end, neither the army nor the navy

offered proof against the tsar’s internal and exter-

nal enemies.

See also: ADMINISTRATION, MILITARY; BALKAN WARS;

BALTIC FLEET; CAUCASIAN WARS; COSSACKS; CRIMEAN

WAR; DECEMBRIST MOVEMENT AND REBELLION; GREAT

REFORMS; NAPOLEON I; NORTHERN FLEET; PACIFIC FLEET;

RUSSO-TURKISH WARS; SEVEN YEARS’ WAR; STRELTSY;

WORLD WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baumann, Robert F. (1993). Russian-Soviet Unconven-

tional Wars in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and

Afghanistan. Ft. Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies

Institute.

Curtiss, John S. (1965). The Russian Army of Nicholas I,

1825–1855. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Duffy, Christopher. (1981). Russia’s Military Way to the

West: Origins and Nature of Russian Military Power

1700–1800. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Fuller, William C., Jr. (1992). Strategy and Power in Rus-

sia, 1600–1914. New York: The Free Press.

Kagan, Frederick W. (1999). The Military Reforms of

Nicholas I: The Origins of the Modern Russian Army.

New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Kagan, Frederick W., and Higham, Robin, eds. (2002).

The Military History of Tsarist Russia. New York: Pal-

grave.

Keep, John L.H. (1985). Soldiers of the Tsar: Army and So-

ciety in Russia, 1462–1874. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

LeDonne, John P. (2003). The Grand Strategy of the Russ-

ian Empire, 1650–1831. New York: Oxford Univer-

sity Press.

Menning, Bruce W. (2000). Bayonets before Bullets: The

Imperial Russian Army, 1861–1914. Bloomington: In-

diana University Press.

Mitchell, Donald W. (1974). A History of Russian and So-

viet Sea Power. New York: Macmillan.

Reddel, Carl F., ed. (1990). Transformation in Russian and

Soviet Military History. Washington, DC: U. S. Air

Force Academy and Office of Air Force History.

Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David, and Menning,

Bruce W., eds. (2003). Reforming the Tsar’s Army:

Military Innovation in Imperial Russia from Peter the

Great to the Revolution. New York: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Stone, Norman. (1975). The Eastern Front 1914–1917.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Westwood, J.N. (1986). Russia against Japan, 1904–1905.

Albany: State University of New York Press.

Woodward, David. (1965). The Russians at Sea: A History

of the Russian Navy. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

The Russian military industrial complex (voenno-

promyshlennyi kompleks, or VPK), recently renamed

the defense industrial complex (oboronno-promysh-

lennyi kompleks, or OPK), encompasses the panoply

of activities overseen by the Genshtab (General

Staff), including the Ministry of Defense, uni-

formed military personnel, FSB (Federal Security

Bureau) troops, border and paramilitary troops, the

space program, defense research and regulatory

agencies, infrastructural support affiliates, defense

industrial organizations and production facilities,

strategic material reserves, and an array of troop

reserve, civil defense, espionage, and paramilitary

activities. The complex is not a loose coalition

MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

932

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY