Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

cability of canonized belief from the challenges

launched by science, and even wrote a hymn lam-

pooning the theologians who stood in the way of

scientific progress. While attacking theological

zealots, he never deviated from a candid respect for

religion—and he never alienated himself from the

church. Small wonder, then, that two archiman-

drites and a long line of priests officiated at his bur-

ial rites. After his death, the church recognized him

as one of Russia’s premier citizens, and many

learned theologians took an active part in building

the symbolism of the Lomonosov legend.

In his time, and shortly after his death, Lomono-

sov was known almost exclusively as a poet; only

isolated contemporaries grasped the intellectual and

social significance of his achievements in science. A

good part of his main scientific manuscripts lan-

guished in the archives of the St. Petersburg Acad-

emy until the beginning of the twentieth century.

Lomonosov was known for having made little ef-

fort to communicate with Russian scientists in and

outside the Academy. On his death, a commemo-

rative session was attended by eight members of

the Academy, who heard a short encomium deliv-

ered by Nicholas Gabriel de Clerc, a French doctor

of medicine, writer on Russian history, newly

elected honorary member of the Academy, and per-

sonal physician of Kirill Razumovsky, president of

the Academy. While de Clerc praised Lomonosov

effusively, he barely mentioned his work in science.

See also: ACADEMY OF ARTS; ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; ED-

UCATION; ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF; SLAVIC-

GREEK-LATIN ACADEMY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Leicester, Henry M. (1976). Lomonosov and the Corpuscu-

lar Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Menshutkin, B. N. (1952). Russia’s Lomonosov, Chemist,

Courtier, Physicist, Poet, tr. I. E. Thal and E. J. Web-

ster, Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Pavlova, G. E., and Fedorov, A. S. (1984). Mikhail Vasil’e-

vich Lomonasov: His Life and Work, Moscow: Mir.

A

LEXANDER

V

UCINICH

LORIS-MELIKOV, MIKHAIL TARIELOVICH

(1825–1888), Russian general and minister, head

of Supreme Executive Commission in 1880–1881.

Mikhail Loris-Melikov was born in Tiflis into

a noble family. He studied at the Lazarev Institute

of Oriental Languages in Moscow and at the mili-

tary school in St. Petersburg (1839–1843). In 1843

he started his military service as a minor officer in

a guard hussar regiment. In 1847 he asked to be

transferred to the Caucasus, where he took part in

the war with highlanders in Chechnya and Dages-

tan. He later fought in the Crimean War from 1853

to 1856. From 1855 to 1875 he served as the su-

perintendent of the different districts beyond the

Caucasus and proved a gifted administrator. In

1875 Loris-Melikov was promoted to cavalry gen-

eral. From 1876 he served as the commander of the

Separate Caucasus Corps. During the war with

Turkey of 1877–1878 Loris-Melikov commanded

Russian armies beyond the Caucasus, and distin-

guished himself in the sieges of Ardagan and Kars.

In 1878 he was awarded the title of a count.

In April of 1879, after Alexander Soloviev’s as-

sault on emperor Alexander II, Loris–Melikov was

appointed temporary governor–general of Kharkov.

He tried to gain the support of the liberal commu-

nity and was the only one of the six governor–

generals with emergency powers who did not

approve a single death penalty. A week after the ex-

plosion of February 5, 1880, in the Winter Palace,

he was appointed head of the Supreme Executive

Commission and assumed almost dictator-like

power. He continued his policy of cooperation with

liberals, seeing it as a way of restoring order in the

country. At the same time, he was strict in his tac-

tics of dealing with revolutionaries. In the under-

ground press, these tactics were called “the wolf’s

jaws and the fox’s tail.” In April 1880 Loris-Me-

likov presented to Alexander II a report containing

a program of reforms, including a tax reform, a lo-

cal governing reform, a passport system reform,

and others. The project encouraged the inclusion of

elected representatives of the nobility, of zemstvos,

and of city government institutions in the discus-

sions of the drafts of some State orders.

In August 1880 the Supreme Executive Com-

mission was dismissed at the order of Loris-Melikov,

who believed that the commission had done its job.

At the same time, the Ministry of Interior and the

Political Police were reinstated. The third division

of the Emperor’s personal chancellery (the secret

police) was dismissed, and its functions were given

to the Department of State Police of the Ministry

of the Interior. Loris-Melikov was appointed min-

ister of the interior. In September 1880, at the ini-

tiative of Loris-Melikov, senators’ inspections were

LORIS-MELIKOV, MIKHAIL TARIELOVICH

873

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

undertaken in various regions of Russia. The re-

sults were to be taken into consideration during the

preparation of reforms. In January 1880 Loris-

Melikov presented a report to the emperor in which

he suggested the institution of committees for an-

alyzing and implementing the results of the sena-

tors’ inspections. The committees were to consist

of State officials and elected representatives of zem-

stvos and city governments. The project later be-

came known under the inaccurate name of

“Loris-Melikov’s Constitution.” On the morning of

March 13, 1881, Alexander II signed the report pre-

sented by Loris-Melikov and called for a meeting of

the Council of Ministers to discuss the document.

The same day the emperor was killed by the mem-

bers of People’s Will.

At the meeting of the Council of Ministers on

March 20, 1881, Loris-Melikov’s project was

harshly criticized by Konstantin Pobedonostsev and

other conservators, who saw this document as a

first step toward the creation of a constitution. The

new emperor, Alexander III, accepted the conserva-

tors’ position, and on May 11 he issued the man-

ifesto of the “unquestionability of autocracy,”

which meant the end of the reformist policy. The

next day, Loris-Melikov and two other reformist

ministers, Alexander Abaza and Dmitry Miliutin,

resigned, provoking the first ministry crisis in

Russian history.

Having resigned, but remaining a member of

the State Council, Loris-Melikov lived mainly

abroad in Germany and France. He died in Nice.

See also: ALEXANDER II; AUTOCRACY; LOCAL GOVERN-

MENT AND ADMINISTRATION; ZEMSTVO

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zaionchkovskii, Petr Andreevich. (1976). The Russian Au-

tocracy under Alexander III. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic

International Press.

Zaionchkovskii, Petr Andreevich. (1979). The Russian Au-

tocracy in Crisis, 1878-1882. Gulf Breeze, FL: Acade-

mic International Press.

O

LEG

B

UDNITSKII

LOTMAN, YURI MIKHAILOVICH

(1922–1993), scholar, founder of the Tartu-

Moscow Semiotic School.

Yuri Lotman was a widely cited scholar of So-

viet literary semiotics and structuralism. He estab-

lished the Tartu-Moscow Semiotic School at Tartu

University in Estonia. This school is famous for its

Works on Sign Systems (published in Russian as Trudy

po znakovym systemam). Unusually prolific, he pub-

lished some eight hundred works on a high schol-

arly level. He is sometimes compared to Mikhail

Bakhtin, another well-known Russian scholar.

Lotman began teaching at the University of

Tartu in 1954. Starting as a historian of Russian

literature, Lotman focused on the work of

Radishchev, Karamzin, and Vyazemsky and the

writers linked to the Decembrist movement. His

later books covered all major literary works, from

the Lay of Igor’s Campaign to the classic nineteenth-

century authors such as Pushkin and Gogol, to Bul-

gakov, Pasternak, and Brodsky. From traditional

philology Lotman shifted in the early sixties to cul-

tural semiotics. His first key publication of that

time, Lectures on Structural Poetics (1964), intro-

duced the abovementioned series Trudy po znakovym

sistemam, which was one of the main initiatives of

the Tartu-Moscow school.

Lotman’s theory of literature rests upon two

closely related sets of fundamental concepts—those

of semiotics and structuralism. Semiotics is the sci-

ence of signs and sign systems, which studies the

basic characteristics of all signs and their combi-

nations: the words and word combinations of nat-

ural and artificial languages, the metaphors of

poetic language, and chemical and mathematical

symbols. It also treats systems of signs such as

those of artificial logical and machine languages,

the languages of various poetic schools, codes, an-

imal communication systems, and so on. Each sign

contains: a) the signifying material (perceived by

the sense organs), and b) the signified aspect (mean-

ing). For words of natural (ordinary) language,

pronunciation or writing is the signifying aspect

while content is the signified aspect. The signs of

one system (for example, the words of a language)

can be the signifying aspect for complex signs of

another system (such as that of poetic language)

superimposed on them.

Lotman defined structuralism as “the idea of a

system: a complete, self-regulating entity that

adapts to new conditions by transforming its fea-

tures while retaining its systematic structure.” He

argued that any chosen object of investigation must

be viewed as an interrelated, interdependent system

composed of units and rules for their possible com-

binations. He defined culture itself as “the whole of

uninherited information and the ways of its orga-

nization and storage.” From the point of view of

LOTMAN, YURI MIKHAILOVICH

874

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

semiotics, anything linked with meaning in fact

belongs to culture. Since natural language is the

central operator of culture, Lotman and the Tartu-

Moscow school deemed natural language to be a

primary modeling system containing a general pic-

ture of the world. Language was the most devel-

oped, universal means of communication—the

“system of systems.” Lotman took keen interest in

the way philosophical ideas, world views, and so-

cial values of a given period are enacted in its lit-

erature (via language). For Lotman, a period’s

literary and ideological consciousness and the aes-

thetics of its trends and currents have a systemic

quality. These categories are not a hodgepodge of

convictions about the world and literature, but a

hierarchic group of cognitive, ethical, and aesthetic

values.

Critics might object to perceived “scientific op-

timism,” reductionism, and polemics of the Tartu-

Moscow School. The ideological pressures within

the USSR with which the school coped probably

discouraged internal debates and explicit criticism

of its own views.

See also: BAKHTIN, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH; EDUCATION;

ESTONIA AND ESTONIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lotman, Iu. M.; Ginzburg, Lidiia; et al. (1985). The Semi-

otics of Russian Cultural History: Essays. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

Lotman, Iu. M. (2001). Universe of the Mind: A Semiotic

Theory of Culture (The Second World), tr. Ann Shuk-

man. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Staton, Shirley F. (1987). Literary Theories in Praxis.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

LOVERS OF WISDOM, THE

The Lovers of Wisdom (Liubomudry), writers based

in Moscow during the 1820s, were strongly influ-

enced by Romanticism and set out to explore the

philosophical, religious, aesthetic and cultural im-

plications of German Idealist philosophy. The So-

ciety for the Love of Wisdom met secretly in the

apartment of its president, Vladimir Odoyevsky

(ca. 1803–1869) from 1823 to 1825. While the So-

ciety formally disbanded following the Decembrist

uprising, its members’ works continued to display

unity of interest and purpose through the late

1820s. The group’s core consisted of Odoyevsky,

Dmitry Venevitinov (1805–1827), Ivan Kireyevsky

(1806–1856), Alexander Koshelev (1806–1883),

and Nikolai Rozhalin (1805–1834). But the num-

ber of people generally considered Lovers of Wis-

dom is much broader, including Alexei Khomyakov

(1804–1860), Stepan Shevyrev (1806–1864),

Vladimir Titov (1807–1891), Dmitry Struisky

(1806–1856), Nikolai Melgunov (1804–1867), and

Mikhail Pogodin (1800–1875).

In secondary literature, the Lovers of Wisdom

have long been overshadowed by the Decembrists.

While the Decembrists pursued political and mili-

tary careers in St. Petersburg and allegedly con-

spired to force political reform, the Lovers of

Wisdom bided their time at comfortably unde-

manding jobs at the Moscow Archive of the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. They indulged in spec-

ulation on the most abstract issues, with a bent to-

ward mysticism. Even their choice of name, “Lovers

of Wisdom” as opposed to “philosophers”, or

philosophes, is thought to have marked their oppo-

sition to the progressive tradition of the radical En-

lightenment.

Yet the Lovers of Wisdom thought of themselves

as enlighteners in the broader sense. They aimed to

reinvigorate Russian high culture by attacking the

moral corruption of the nobility and promoting

creativity and the pursuit of knowledge. They con-

trasted the superstition and petty-mindedness of

the nobility to the moral purity of the “lover of

wisdom,” who often appeared in their satires and

oriental tales in the guise of a magus, dervish, brah-

min, Greek philosopher, or sculptor, or a misun-

derstood Russian writer. Whether in short stories,

metaphysical poetry, or quasi-philosophical prose

works, Odoyevsky, Venevitinov, Khomyakov and

Shevyrev emphasized the great spiritual and even

religious importance of the young, creative indi-

vidual, or genius. The special status of such indi-

viduals was only highlighted by their apparent

moral fragility and vulnerability in a hostile envi-

ronment.

The group was heavily indebted to Romanti-

cism and to German Idealist philosophy. Admittedly,

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling’s philosophy

seems to have appealed in part because it was dif-

ficult to understand. As Koyré (1929) remarked,

their Romanticism was characterized by a “slightly

puerile desire to feel ‘isolated from the crowd,’ the

desire for the esoteric, which is complemented by

the possession of a secret, even if that secret con-

sists only in the fact that one possesses one.”

(p. 37). But their works also display a genuine

LOVERS OF WISDOM, THE

875

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

commitment to principles such as the fundamen-

tal unity of matter and ideas, and the notion that

these achieve higher synthesis in the absolute, the

spirit that guides the world. To them, creating a

work of art, or striving for any kind of knowledge,

brought the individual into contact with the ab-

solute, lending the artist or intellectual special re-

ligious status.

Such views did not accord with Orthodox

Christianity. The political authorities did not wel-

come them either. Yet the Lovers of Wisdom found

ways of promoting their views in poetry and prose

they published in journals and almanacs, especially

in Mnemozina (1824–1825), edited by Odoyevsky

with the Decembrist Wilgelm Kyukhelbeker, and

Moskovsky vestnik (1827–1830), edited by Pogodin.

They also published translations from leading

voices of Romanticism such as Goethe, Byron, Tieck

and Wackenroder.

The closure of Moskovsky vestnik in 1830

marked the end of the Lovers of Wisdom as a

group. But the death of Venevitinov, often consid-

ered their most talented member, in 1827, had al-

ready dealt them a blow, as did the departure of

many key members from Moscow in the late

1820s. In the early 1830s, the group’s members

developed in new directions. Some of them, such

as Kireyevsky and Khomyakov, eventually became

leaders of the Slavophile movement, arguably the

most coherent and original strain in nineteenth-

century Russian thought.

See also: DECEMBRIST MOVEMENT AND REBELLION;

KHOMYAKOV, ALEXEI STEPANOVICH; KIREYEVSKY,

IVAN VASILIEVICH; ODOYEVSKY, VLADIMIR FYODOR-

OVICH; POGODIN, MIKHAIL PETROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gleason, Abott. (1972). European and Muscovite: Ivan

Kireevsky and the Origins of Slavophilism. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Koyré, Alexandre. (1929). La philosophie et le problème na-

tional en Russie au début du XIXe siècle. Paris: Librairie

Ancienne Honoré Champion.

V

ICTORIA

F

REDE

LUBOK

Broadsides or broadsheet prints (pl. lubki).

Broadsides first appeared in Russia in the sev-

enteenth century, probably inspired by German

woodcuts. Subjects were depicted in a native style.

Captions complemented the printed images. The

earliest lubki represented saints and other religious

figures, but humorous illustrations also circulated

that captured the parody spirit of skomorok (min-

strel) performances of the era—especially the

wacky wordplay of the theatrical entr’actes.

In the 1760s prints began to be made from

metal plates, facilitating production of longer texts.

Lithographic stone supplanted copper plates, but in

turn gave way to cheaper and lighter zinc plates in

the second half of the nineteenth century. Pedlars

bought the pictures in bulk at fairs or in Moscow

and sold them in the countryside. Originally ac-

quired by nobles, the images were taken up by the

merchantry, officials, and tradesmen before be-

coming the province of the peasantry in the nine-

teenth century, at which point lubok, in its

adjectival form, came to mean “shoddy.” It was

also in the nineteenth century that the term came

to refer to cheap printed booklets aimed at popu-

lar audiences.

Lubki depicted historical figures, characters

from folklore, contemporary members of the rul-

ing family, festival pastimes, battle scenes, judicial

punishments, and hunting and other aspects of

everyday life, along with religious subjects. The

prints decorated peasant huts, taverns, and the in-

sides of lids of trunks used by peasants when they

moved to cities or factories to work. The native

style of the prints was adapted by Old Believers in

the nineteenth century in their manuscript print-

ing. Avant-garde artists in the early twentieth cen-

tury drew inspiration from the style in their

neo-primitivist phase. An “Exhibition of Icons and

Lubki” was held in Moscow in 1913.

See also: CHAPBOOK LITERATURE; OLD BELIEVERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bowlt, John E. (1998). “Art.” In The Cambridge Compan-

ion to Modern Russian Literature, ed. Nicholas

Rzhevsky. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Brooks, Jeffrey. (1985). When Russia Learned to Read: Lit-

eracy and Popular Literature, 1861–1917. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Farrell, Dianne E. (1991). “Medieval Popular Humor in

Russian Eighteenth Century Lubki.” Slavic Review

50:551–565.

G

ARY

T

HURSTON

LUBOK

876

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

LUBYANKA

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission on the

Struggle Against Counter-Revolution, Sabotage, and

Speculation (VCHk, or Cheka) was founded by the

Bolsheviks in December 1917. Headed by Felix Dz-

erzhinsky, it was responsible for liquidating coun-

terrevolutionary elements and remanding saboteurs

and counter-revolutionaries to be tried by the revo-

lutionary-military tribunal. In February 1918 it was

authorized to shoot active enemies of the revolution

rather than turn them over to the tribunal.

In March 1918 the Cheka established its head-

quarters in the buildings at 11 and 13 Great Lub-

yanka Street in Moscow. Between the 1930s and

the beginning of the 1980s, a complex of buildings

belonging to the security establishment grew up

along Great Lubyanka Street. The building at No.

20 was constructed in 1982 as the headquarters of

the KGB (Committee of State Security), now the

FSB (Federal Security Bureau), for Moscow and the

Moscow area.

The famous Lubyanka Internal Prison was sit-

uated in the courtyard of what is now the main

building of the FSB on Lubyanka Street. Closed

in the 1960s, it is at present the site of a dining

room, offices, and a warehouse. All its prisoners

were transferred to Lefortovo. In the time of mass

reprisals, prisoners were regularly shot in the

courtyard of the Lubyanka Prison. Automobile en-

gines were run to drown out the noise. Suspects

were brutally interrogated in the prison’s base-

ment.

In addition to the FSB headquarters, the build-

ings on Lubyanka Street also include a museum of

the history of the state security agencies. The of-

fice of Lavrenty Beria, long-time chief of the So-

viet security apparatus, has been kept unchanged

and is open to visitors.

See also: BERIA, LAVRENTI PAVLOVICH; DZERZHINSKY, FE-

LIX EDMUNDOVICH; GULAG; LEFORTOVO; MINISTRY

OF THE INTERIOR; PRISONS; STATE SECURITY, ORGANS

OF

LUBYANKA

877

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky—the first head of the Soviet secret police—looms over Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. Following the

failed August 1991 coup attempt by Communist Party hard-liners, this statue was torn down. © N

OVOSTI

/S

OVFOTO

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Burch, James. (1983). Lubyanka: A Novel. New York:

Atheneum.

G

EORG

W

URZER

LUKASHENKO, ALEXANDER

GRIGORIEVICH

(b. 1954), president of Belarus.

Alexander Grigorievich Lukashenko became

president of Belarus on July 10, 1994, when he

defeated Prime Minister Vyachaslav Kebich in the

country’s first presidential election, running on a

platform of anti-corruption and closer relations

with Russia. He established a harsh dictatorship as

president, amending the constitution to consolidate

his authority.

Lukashenko was born in August 1954 in the

village of Kopys (Orshanske Rayon, Vitebsk Oblast),

but most of his early career was spent in Mahileu

region, where he graduated from the Mahileu

Teaching Institute (his speciality was history) and

the Belarusian Agricultural Academy. From 1975

to 1977, he was a border guard in the Brest area.

He then spent five years in the army before re-

turning to Mahileu, and the town of Shklau, where

he worked as manager of state and collective farms,

and also in a construction materials combine. He

was elected to the Belarusian Supreme Soviet in

1990, where he founded a faction called Commu-

nists for Democracy. In the early 1990s he chaired

a commission investigating corruption.

In April 1995, several months into his presi-

dency, Lukashenko organized a referendum that re-

placed the country’s state symbols and national

flag with others very similar to the Soviet ones and

elevated Russian to a state language. A second ref-

erendum in November 1996 considerably enhanced

the authority of the presidency by reducing the

parliament to a rump body of 120 seats (formerly

there were 260 deputies), establishing an upper

house closely attached to the presidency, and cur-

tailing the authority of the Constitutional Court.

Lukashenko then dated his presidency from late

1996 rather than the original election date of July

1994.

By April 1995, Lukashenko had established a

community relationship with Boris Yeltsin’s Rus-

sia, which went through several stages before be-

ing formalized as a Union state in late 1999. Un-

der Vladimir Putin, however, Russia distanced it-

self from the agreement and in the summer of 2002

threatened to incorporate Belarus into the Russian

Federation.

Lukashenko clamped down on opposition move-

ments and imposed tight censorship over the

media. His contraventions of human rights in the

republic have elicited international concern.

See also: BELARUS AND BELARUSIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Marples, David R. (1999). Belarus: A Denationalized Na-

tion. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Zaprudnik, Jan. (1995). Belarus: At a Crossroads in His-

tory. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

D

AVID

R. M

ARPLES

LUKYANOV, ANATOLY IVANOVICH

(b. 1930), chair of the USSR Supreme Soviet dur-

ing the August 1991 coup attempt.

Anatoly Lukyanov studied law at Moscow

State University, graduating in 1953. While at the

university, he chaired the University Komsomol

branch, and Mikhail Gorbachev was deputy chair.

Lukyanov joined the Party in 1955 and began a ca-

reer within the Party apparatus. He was appointed

to the Central Committee Secretariat in 1987. By

1988, Lukyanov was named a candidate member

of the Politburo and first deputy chair of the Pre-

sidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet.

The first USSR Congress of People’s Deputies

elected Lukyanov chairman of the newly reconfig-

ured Supreme Soviet in 1990. This post allowed

him to control the parliamentary agenda. He was

repeatedly accused of stonewalling legislation he did

not like and putting bills he supported to vote mul-

tiple times if they were voted down.

Despite his close personal links with Gorbachev,

Lukyanov sided with opponents of Gorbachev’s

policies. The hard-line Soyuz faction particularly

favored Lukyanov over Gorbachev. During his De-

cember 1990 resignation speech to the Congress,

Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze specifically

criticized Lukyanov for interfering in Soviet-

German relations and for his desire for a dictator-

ship.

LUKASHENKO, ALEXANDER GRIGORIEVICH

878

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

As Gorbachev’s new Union Treaty neared rat-

ification in summer 1991, hard-line members of

the Soviet leadership hierarchy staged a coup to

overthrow Gorbachev and prevent adoption of the

treaty. Though Lukyanov was not a member of

the State Committee for the State of Emergency

that briefly seized power August 19–21, 1991, he

supported their efforts. Lukyanov was arrested fol-

lowing the coup’s collapse, then amnestied in Feb-

ruary 1994 and elected to the Russian Duma in

1995 and 1999, where he chaired the parliamen-

tary committee on government reform.

See also: AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Wishnevsky, Julia. (1991). “Anatolii Luk’yanov: Gor-

bachev’s Conservative Rival?” RFE/RL Report on the

USSR 3(23):8–14.

A

NN

E. R

OBERTSON

LUNACHARSKY, ANATOLY VASILIEVICH

(1875–1933), Bolshevik intellectual and early So-

viet leader.

Born the son of a state councilor, Anatoly Lu-

nacharsky joined the Social Democratic movement

in 1898 and was soon arrested. As an exile in

Vologda, he met Alexander Bogdanov. In Paris in

1904 both men joined the Bolshevik faction, but

they left it again in 1911 after clashes with Lenin

over philosophy. Bogdanov advocated empiriocrit-

icism, claiming that only direct experience could be

relied on as a basis for knowledge. Lunacharsky

promoted God–building, an anthropocentric reli-

gion striving toward the moral unity of mankind.

Lunacharsky rejoined the Bolshevik Party in Au-

gust 1917 and became the first People’s Commis-

sar of Enlightenment (Narkom prosveshcheniya, or

Narkompros), serving from October 1917 to 1929.

A prolific writer on literature and the arts and an

important patron of the intelligentsia, Lunacharsky

was often regarded within the party as too “soft”

for a Bolshevik. From the mid–1920s he was in-

creasingly marginalized, and his last years at

Narkompros were marked by fierce battles over ed-

ucation and culture as his soft line in policy was

discredited with the onset of the Cultural Revolu-

tion. After his resignation from Narkompros, he

held various second–rank positions in cultural ad-

ministration and spent much time abroad, partly

for health reasons. In 1933 he was appointed am-

bassador to Spain, but died before assuming the po-

sition. His reputation plummeted after his death,

but from the 1960s to the 1980s, thanks partly to

the untiring work of his daughter, Irina Luna-

charskaya, he became a symbol of a (pre–Stalinist)

humanistic Bolshevism protective of the intelli-

gentsia and committed to the advancement of high

culture.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; CULTURAL REVOLUTION; EDUCA-

TION; PROLETKULT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1970). The Commissariat of Enlight-

enment: Soviet Organization of Education and the Arts

under Lunacharsky, October 1917-1921. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

O’Connor, Timothy Edward. (1983). The Politics of Soviet

Culture: Anatolii Lunacharskii. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI

Research Press.

S

HEILA

F

ITZPATRICK

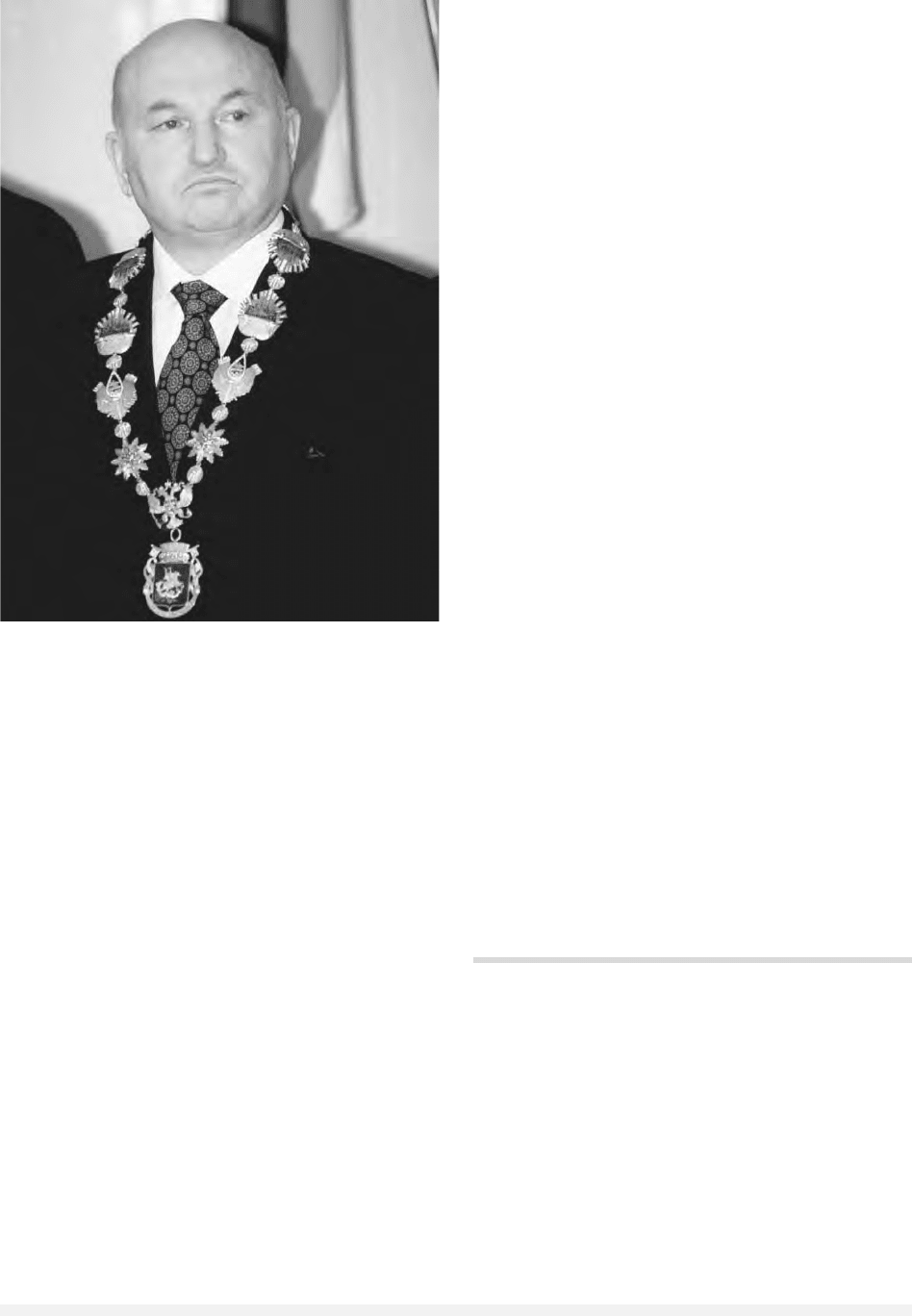

LUZHKOV, YURI MIKHAILOVICH

(b. 1936), Russian politician and mayor of Moscow.

Yuri Luzhkov became a member of the Com-

munist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1968

and remained a member until the party was out-

lawed in the wake of the failed coup of August

1991. He left a management career in the chemi-

cal industry to become a deputy to the Moscow

City Council (Soviet) in 1977. In 1987, his politi-

cal career took a great stride forward when Boris

Yeltsin became First Secretary of the Moscow Com-

munist Party organization. In keeping with the So-

viet practice of assigning party members to

multiple responsibilities, Luzhkov was appointed

deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet

Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and first

deputy to the chair of the Moscow City Executive

Committee.

Luzhkov was appointed chair of the City Ex-

ecutive Committee following Gavriil Popov’s elec-

tion as mayor of Moscow in 1990. The following

year he was elected Popov’s vice mayor. During the

August 1991 coup, he helped organize the defense

LUZHKOV, YURI MIKHAILOVICH

879

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of the White House, the parliament building of the

Russian Federation from which Boris Yeltsin orga-

nized the resistance to the efforts of conservatives

within the CPSU to undo the Gorbachev reforms.

Following the collapse of the coup and the sub-

sequent dissolution of the Soviet Union, a struggle

emerged between Russian President Boris Yeltsin

and the legislature over the course of reform.

Luzhkov, owing to his strong support for Yeltsin

in the conflict, was made mayor by presidential de-

cree when Popov was forced to resign. The decree

was met with opposition within the Moscow City

Council, which tried unsuccessfully on two occa-

sions to unseat Luzhkov.

As his predecessor had done, Luzhkov threw

his support behind Yeltsin in the confrontation

with the Russian parliament. At the height of the

conflict following Yeltsin’s September 1993 decree

dissolving the legislature, which resulted in an

armed standoff, the mayor cut off utilities and

services to the parliament and deployed the city’s

police to forcibly disband meetings and demon-

strations organized in support of the legislature.

Luzhkov remained mayor of Moscow, but his

regime has not been without controversy. He has

come under particular criticism for the manner in

which privatization of municipal property has been

carried out. On several occasions the press has

charged the mayor with corruption, favoritism,

and using his position for personal gain. Despite

this, the city’s relatively good economic situation

in comparison with the rest of the country has

made Luzhkov enormously popular with Mus-

covites. He was reelected with 88 percent of the

vote in 1996.

However, the mayor’s efforts to rid the city of

those without residency permits has undermined

his popularity with the rest of the country. When

Luzhkov announced his candidacy to the 2000 pres-

idential elections and formed the bloc Fatherland-

All Russia, supporters of Vladimir Putin were able

to organize a negative ad campaign, which quickly

marginalized the mayor’s bloc. Following Putin’s

electoral victory, Luzhkov moved to defend his po-

litical position by declaring his loyalty to the new

president.

See also: AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; FATHERLAND-ALL RUS-

SIA; MOSCOW; YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Luzhkov, Yuri M. (1996). Moscow Does Not Believe in

Tears: Reflections of Moscow’s Mayor. Chicago: James

M. Martin.

T

ERRY

D. C

LARK

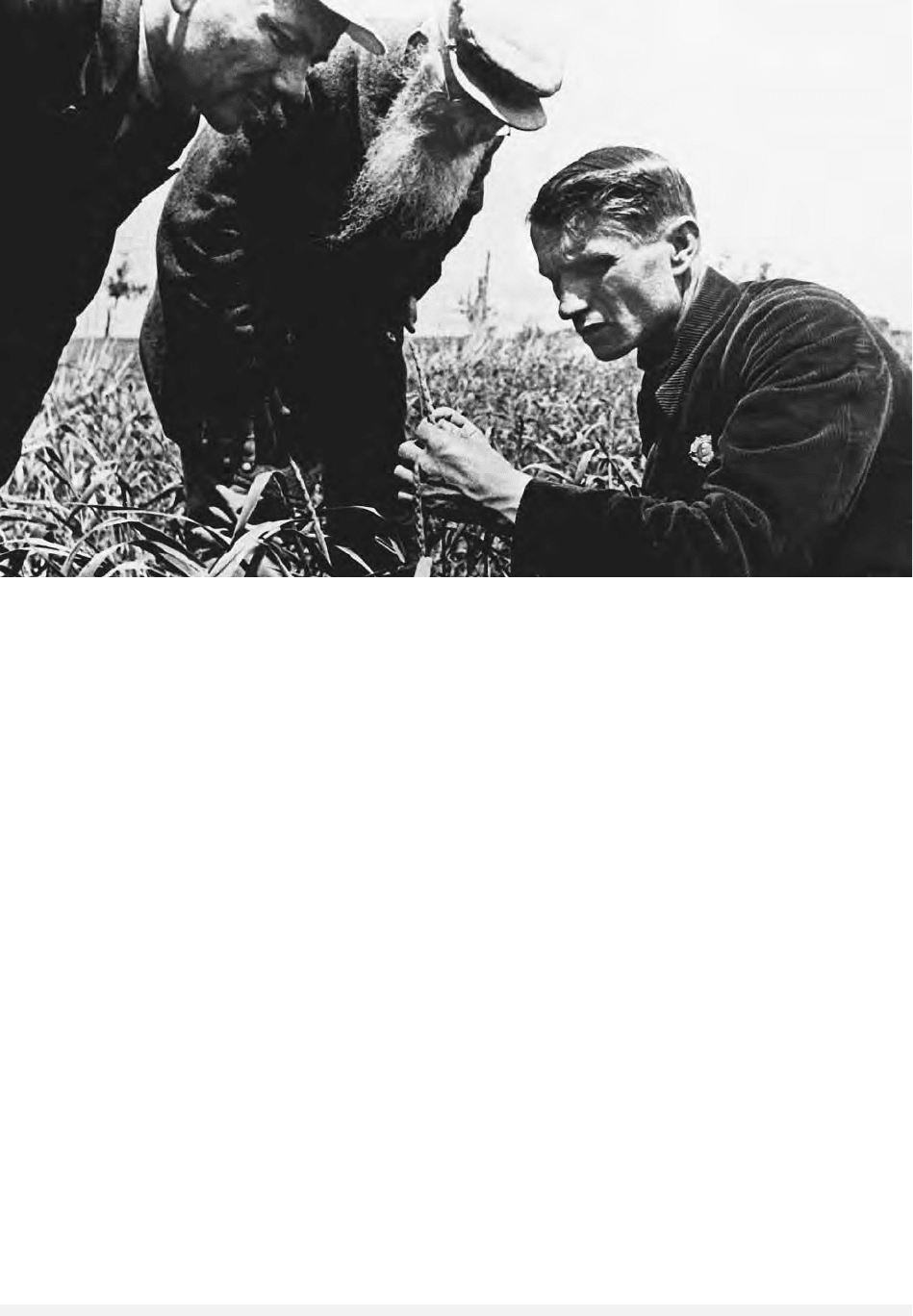

LYSENKO, TROFIM DENISOVICH

(1898–1976), agronomist and biologist.

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko was born in

Karlovka, Ukraine, to a peasant family. He attended

the Kiev Agricultural Institute as an extramural

student and graduated as doctor of agricultural sci-

ence in 1925. A disciple of horticulturist Ivan

Michurin’s work, Lysenko worked at the Gyandzha

Experimental Station between 1925 and 1929 and

coined his theory of vernalization in the late 1920s.

His vernalization theory described a process where

LYSENKO, TROFIM DENISOVICH

880

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Yuri Luzhkov is sworn in for his second term as mayor of

Moscow, December 29, 1996. © R

EUTERS

N

EW

M

EDIA

I

NC

./CORBIS

winter habit was transformed into spring habit by

moistening and chilling the seed.

During the agricultural crisis of the 1930s, So-

viet authorities started supporting Lysenko’s theo-

ries. By the mid-1930s Lysenko’s dominance in

agricultural sciences was clearly established as he

founded agrobiology, a pseudoscience that promised

to increase yields rapidly and cheaply. He became

president of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agri-

cultural Sciences in 1938 and director of the Insti-

tute of Genetics at the Academy of Sciences in 1940.

Lysenko and his followers, Lysenkoites, have long

been thought to have had a direct line to the Stal-

inist terror apparatus as they targeted geneticists

that they thought opposed Lysenkoism, most fa-

mously noted scientist Nikolai Vavilov.

As Lysenko’s political influence increased, he

expressed his views more forcefully. His view of

genetics was irrational and based neither on reason

nor scientific experimentation. His theory of hered-

ity rejected established principles of genetics, and he

believed that he could change the genetic constitu-

tion of strains of wheat by controlling the envi-

ronment. For example, he claimed that wheat

plants raised in the appropriate environment pro-

duced seeds of rye.

By 1948 education and research in traditional

genetics had been completely outlawed in the So-

viet Union. The 1948 August Session of the Lenin

Academy of Agricultural Sciences gave the Ly-

senkoites official endorsement for these views,

which were said to correspond to Marxist theory.

From that moment, and until Josef Stalin’s death,

Lysenko was the total autocrat of Soviet biology.

His position as Stalin’s henchman in Soviet science

has been compared to Andrei Zhdanov’s role in cul-

ture during this time of high Stalinism.

In April 1952 the Ministry of Agriculture with-

drew its support of Lysenko’s cluster method of

planting trees, but Lysenko was not publicly re-

buked until after Stalin’s death in 1953. Nikita

Khrushchev tolerated criticism of Lysenkoism,

LYSENKO, TROFIM DENISOVICH

881

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet geneticist Trofim Lysenko measures the growth of wheat in a collective farm near Odessa, Ukraine. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

but it took eleven years to completely confirm

the uselessness of agrobiology. It was only with

Khrushchev’s ousting from power in 1964 that

Lysenko was fully discredited and research in tra-

ditional genetics accepted. He resigned as president

of the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences

in 1956, and his removal from the position of di-

rector of the Institute of Genetics in 1965 signified

the full return of scientific professionalism in So-

viet science. Lysenko kept the title of academician

and held the position of chairman for science at the

Academy of Science’s Agricultural Experimental

Station, located not far from Moscow, until he died

in November 20, 1976.

See also: AGRICULTURE; SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POL-

ICY; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; VAVILOV, NIKO-

LAI IVANOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Joravsky, David. (1970). The Lysenko Affair. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Medvedev, Zhores A. (1969). The Rise and Fall of T. D.

Lysenko. New York: Columbia University Press.

Medvedev, Zhores A. (1978). Soviet Science. New York:

Norton.

R

ÓSA

M

AGNÚSDÓTTIR

LYSENKO, TROFIM DENISOVICH

882

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY