Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

trained secondary school teachers. His early inter-

est in chemistry focused on isomorphism—the

groups of chemical elements with similar crystalline

forms and chemical properties. In 1856 he earned

a magisterial degree from St. Petersburg University

and was appointed a private docent at the same in-

stitution. In 1859 a state stipend took him to the

University of Heidelberg for advanced studies in

chemistry. In 1861 he returned to St. Petersburg

University and wrote Organic Chemistry, the first

volume of its kind to be published in Russian. He

offered courses in analytical, technical, and organic

chemistry. In 1865 he defended his doctoral disser-

tation and was appointed professor of chemistry, a

position he held until his retirement in 1890.

In 1868, with solid experience in chemical re-

search , he undertook the writing of The Principles

of Chemistry, a large study offering a synthesis of

contemporary advances in general chemistry. It

was during the writing of this book that he dis-

covered the periodic law of elements, one of the

greatest achievements of nineteenth-century chem-

istry. In quality this study surpassed all existing

studies of its kind. It was translated into English,

French, and German. In 1888 the English journal

Nature recognized it as “one of the classics of chem-

istry” whose place “in the history of science is as

well-assured as the ever-memorable work of [Eng-

lish chemist John] Dalton.”

An international gathering of chemists in Karl-

sruhe in 1860 had agreed in establishing atomic

weights as the essential features of chemical ele-

ments. Several leading chemists immediately began

work on establishing a full sequence of the sixty-

four elements known at the time. Mendeleyev took

an additional step: he presented what he labeled the

periodic table of elements, in which horizontal lines

presented elements in sequences of ascending

atomic weights, and vertical lines brought together

elements with similar chemical properties. He

showed that in addition to the emphasis on the di-

versity of elements, the time had also come to rec-

ognize the patterns of unity.

Beginning in the 1870s, Mendeleyev wrote on

a wide variety of themes reaching far beyond chem-

istry. He was most concerned with the organiza-

tional aspects of Russian industry, the critical

problems of agriculture, and the dynamics of edu-

cation. He tackled demographic questions, develop-

ment of the petroleum industry, exploration of the

Arctic Sea, the agricultural value of artificial fertil-

izers, and the development of a merchant navy in

Russia. In chemistry, he elaborated on specific as-

pects of the periodic law of elements, and wrote a

large study on chemical solutions in which he

advanced a hydrate theory, critical of Svante

Arrhenius’s and Jacobus Hendricus van’t Hoff’s

electrolytic dissociation theory. At the end of his

life, he was engaged in advancing an integrated

view of the chemical unity of nature. Mendeleyev

saw the future of Russia in science and in a phi-

losophy avoiding the rigidities of both idealism and

materialism.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mendeleev, Dmitry. (1901). The Principles of Chemistry, 4

vols. New York: Collier.

Rutherford, Ernest. (1934). “The Periodic Law and its In-

terpretation: Mendeleev Centenary Lecture,” Journal

of the Chemical Society 1934(1):635–642.

Vucinich, Alexander. (1967). “Mendeleev’s Views on Sci-

ence and Society.” ISIS 58:342–351.

A

LEXANDER

V

UCINICH

MENSHEVIKS

The Menshevik Party was a moderate Marxist

group within the Russian revolutionary move-

ment. The Mensheviks originated as a faction of

the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party

(RSDWP). In 1903, at the Second Party Congress,

Yuli O. Martov proposed a less restrictive definition

of party membership than Vladimir I. Lenin. Based

on the voting at the congress, Lenin’s faction of the

party subsequently took the name Bolshevik, or

“majority,” and Martov’s faction assumed the

name Menshevik, or “minority.” The party was

funded by dues and donations. Its strength can be

measured by proportionate representation at party

meetings, but membership figures are largely spec-

ulative because the party was illegal during most

of its existence.

Russian revolutionaries had embraced Marxism

in the 1880s, and the Mensheviks retained Georgy

Plekhanov’s belief that Russia would first experi-

ence a bourgeois revolution to establish capitalism

before advancing to socialism, as Karl Marx’s model

implied. They opposed any premature advance to

socialism. A leading Menshevik theorist, Pavel

Borisovich Akselrod, stressed the necessity of es-

tablishing a mass party of workers in order to as-

sure the triumph of social democracy.

MENSHEVIKS

913

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

During the 1905 Revolution, which established

civil liberties in Russia, Akselrod called for a “work-

ers’ congress,” and many Mensheviks argued for

cooperation with liberals to end the autocracy.

Their Leninist rivals vested the hope for revolution

in a collaboration of peasants and workers. Despite

these differences, Bolsheviks and Mensheviks par-

ticipated in a Unification Congress at Stockholm in

1906. The Menshevik delegates voted to participate

in elections to Russia’s new legislature, the Duma.

Lenin initially opposed cooperation but later

changed his mind. Before cooperation could be fully

established, the Fifth Party Congress in London

(May 1907) presented a Bolshevik majority. Ak-

selrod’s call for a workers’ congress was con-

demned. Soon afterward the tsarist government

ended civil liberties, repressed the revolutionary

parties, and dissolved the Duma.

From 1907 to1914 the two factions continued

to grow apart. Arguing that the illegal under-

ground party had ceased to exist, Alexander

Potresov called for open legal work in mass orga-

nizations rather than a return to illegal activity.

Fedor Dan supported a combination of legal and il-

legal work. Lenin and the Bolsheviks labeled the

Mensheviks “liquidationists.” In 1912 rival con-

gresses produced a permanent split between the

two factions.

During World War I many Mensheviks were

active in war industries committees and other or-

ganizations that directly affected the workers’

movement. Menshevik internationalists, such as

Martov, refused to cooperate with the tsarist war

effort. The economic and political failure of the

Russian government coupled with continued action

by revolutionary parties led to the overthrow of

the tsar in February (March) 1917. The Menshe-

viks and another revolutionary party, the Socialist

Revolutionaries, had a majority in the workers’

movement and ensured the establishment of de-

mocratic institutions in the early months of the

revolution. Since the Mensheviks opposed an im-

mediate advance to socialism, the party supported

the concept of dual power, which established the

Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet.

In response to a political crisis that threatened the

collapse of the Provisional Government, Menshe-

viks who wanted to defend the revolution, labeled

defensists, decided to join a coalition government

in April 1917. Another crisis in July did not per-

suade the Menshevik internationalists to join.

Thereafter, the Mensheviks were divided on the

Revolution. The Provisional Government failed to

fulfill the hopes of peasants, workers, and soldiers.

Because the Mensheviks had joined the Provi-

sional Government and the Bolsheviks were not

identified with its failure, the seizure of power by

the Soviets in November brought the Bolshevik

Party to power. Martov’s attempts to negotiate the

formation of an all-socialist coalition failed. Men-

sheviks opposed the Bolshevik seizure of power, the

dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, and the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk signed by the Bolsheviks,

who now called themselves the Communist Party.

Marginally legal, the Mensheviks opposed Allied ef-

forts to crush the Soviet state during the civil war

and, though repressed by the communists, also

feared that counterrevolutionary forces might gain

control of the government. Mensheviks established

a republic in Georgia from1918 to 1921. At the end

of the civil war, some workers adopted Menshevik

criticisms of Soviet policy, leading to mass arrests

of party leaders. In 1922 ten leaders were allowed

to emigrate. Others joined the Communist Party

and were active in economic planning and indus-

trial development. Though Mensheviks operated il-

legally in the 1930s, a trial of Mensheviks in 1931

signaled the end of the possibility of even marginal

opposition inside Russia. A Menshevik party abroad

operated in Berlin, publishing the journal Sotsialis-

tichesky Vestnik under the leadership of Martov.

Dan emerged as the leader of this group after Mar-

tov’s death in 1923. To escape the Nazis the Men-

sheviks migrated to Paris and then to the United

States in 1940, where they continued publication

of their journal until 1965.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY; MAR-

TOV, YURI OSIPOVICH; MARXISM; PROVISIONAL GOV-

ERNMENT; SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; SOVIET

MARXISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ascher, Abraham, ed. (1976). The Mensheviks in the Russ-

ian Revolution. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Brovkin, Vladimir. (1987). The Mensheviks After October:

Socialist Opposition and the Rise of the Bolshevik Dic-

tatorship. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Galili, Ziva. (1989). Menshevik Leaders in the Russian Rev-

olution: Social Realities and Political Strategies. Prince-

ton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Haimson, Leopold. ed. (1974). Mensheviks: From the Rev-

olution of 1917 to the Second World War. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

A

LICE

K. P

ATE

MENSHEVIKS

914

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

MENSHIKOV, ALEXANDER DANILOVICH

(c. 1672–1729), soldier and statesman; favorite of

Peter I.

Menshikov rose from humble origins to be-

come the most powerful man in Russia after the

tsar. Anecdotes suggest that his father was a

pastry cook, although in fact he served as a non-

commissioned officer in the Semenovsky guards.

Alexander served in Peter’s own Preobrazhensky

guards, and by the time of the Azov campaigns

(1695–1696) he and Peter were inseparable. Men-

shikov accompanied Peter on the Grand Embassy

(1697–1698) and served with him in the Great

Northern War (1700–1721), rising through the

ranks to become general field marshal and vice ad-

miral. His military exploits included the battles of

Kalisz (1706) and Poltava (1709), the sacking of

Baturin (1708), and campaigns in north Germany

in the 1710s. At home he was governor-general of

St. Petersburg and president of the College of War.

The upstart Menshikov had to create his own

networks, making many enemies among the tra-

ditional elite. He acquired a genealogy which traced

his ancestry back to the princes of Kievan Rus and

a dazzling portfolio of Russian and foreign titles

and orders, including Prince of the Holy Roman

Empire, Prince of Russia and Izhora, and Knight of

the Orders of St. Andrew and St. Alexander Nevsky.

Menshikov had no formal education and was only

semi-literate, but this did not prevent him from be-

coming a role model in Peter’s cultural reforms. His

St. Petersburg palace had a large library and its own

resident orchestra and singers, and he also built a

grand palace at Oranienbaum on the Gulf of Finland.

In 1706 he married Daria Arsenieva (1682–1727),

who was also thoroughly Westernized.

Menshikov was versatile and energetic, loyal

but capable of acting on his own initiative. He was

a devout Orthodox Christian who often visited

shrines and monasteries. He was also ambitious

and corrupt, amassing a vast personal fortune in

lands, serfs, factories, and possessions. On several

occasions, only his close ties with Peter saved him

from being convicted of embezzlement. In 1725 he

promoted Peter’s wife Catherine as Peter’s succes-

sor, heading her government in the newly created

Supreme Privy Council and betrothing his own

daughter to Tsarevich Peter, her nominated heir.

After Peter’s accession in 1727, Menshikov’s rivals

in the Council, among them members of the aris-

tocratic Dolgoruky clan, alienated the emperor

from Menshikov. In September 1727 they had

Menshikov arrested and banished to Berezov in

Siberia, where he died in wretched circumstances

in November 1729.

See also: CATHERINE I; GREAT NORTHERN WAR; PETER I;

PETER II; PREOBRAZHENSKY GUARDS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bushkovitch, Paul. (2001). Peter the Great: The Struggle

for Power, 1671–1725. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the

Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

MERCANTILISM

Mercantilism is the doctrine that economic activity,

especially foreign trade, should be directed to uni-

fying and strengthening state power. Though some

mercantilist writers emphasized the accumulation

of gold and silver by artificial trade surpluses, this

“bullionist” version was not dominant in Russia.

The greatest of the Russian enlightened despots,

Peter the Great, was eager to borrow the best of

Western practice in order to modernize his vast

country and to expand its power north and south.

Toward this end, the tsar emulated successful

Swedish reforms by establishing a regular bureau-

cracy and unifying measures. Peter brought in

Western artisans to help design his new capital at

St. Petersburg. He granted monopolies for fiscal

purposes on salt, vodka, and metals, while devel-

oping workshops for luxury products. Skeptical of

private entrepreneurs, he set up state-owned ship-

yards, arsenals, foundries, mines, and factories.

Serfs were assigned to some of these. Like the state-

sponsored enterprises of Prussia, however, most of

these failed within a few decades.

Tsar Peter instituted many new taxes, raising

revenues some five times, not counting the servile

labor impressed to build the northern capital,

canals, and roads. Like Henry VIII of England, he

confiscated church lands and treasure for secular

purposes. He also tried to unify internal tolls, some-

thing accomplished only in 1753.

Foreign trade was a small, and rather late, con-

cern of Peter’s. That function remained mostly in

MERCANTILISM

915

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the hands of foreigners. To protect the industries

in his domains, he forbade the import of woolen

textiles and needles. In addition, he forbade the ex-

port of gold and insisted that increased import du-

ties be paid in specie (coin).

See also: ECONOMY, TSARIST; FOREIGN TRADE; PETER I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gerschenkron, Alexander. (1970). Europe in the Russian

Mirror. London: Cambridge University Press.

Spechler, Martin C. (2001). “Nationalism and Economic

History.” In Encyclopedia of Nationalism, vol. 1, ed.

Alexander Motyl. New York: Academic Press, pp.

219-235.

Spechler, Martin C. (1990). Perspectives in Economic

Thought. New York: McGraw-Hill.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

MERCHANTS

Kievan Russia supplied raw materials of the for-

est—furs, honey, wax, and slaves—to the Byzan-

tine Empire. This trade had a primarily military

character, as the grand prince and his retinue ex-

torted forest products from Russian and Finnish

tribes and transported them through hostile terri-

tory via the Dnieper River and the Black Sea. In the

self-governing republic of Novgorod, wealthy mer-

chants shared power with the landowning elite.

Novgorod exported impressive amounts of furs,

fish, and other raw materials with the aid of the

German Hansa, which maintained a permanent set-

tlement in Novgorod—the Peterhof—as it did on

Wisby Island and in London and Bergen.

Grand Prince Ivan III of Muscovy extinguished

Novgorod’s autonomy and expelled the Germans.

Under the Muscovite autocracy, prominent mer-

chants acted as the tsar’s agents in exploiting his

monopoly rights over commerce in high-value

goods such as vodka and salt. The merchant estate

(soslovie) emerged as a separate social stratum in

the Law Code (Ulozhenie) of 1649, with the exclu-

sive right to engage in handicrafts and commerce

in cities.

Peter I’s campaign to build an industrial com-

plex to supply his army and navy opened up new

opportunities for Russian merchants, but his gov-

ernment maintained the merchants’ traditional

obligations to provide fiscal and administrative ser-

vices to the state without remuneration. From the

early eighteenth century to the end of the imper-

ial period, the merchant estate included not only

wholesale and retail traders but also persons whose

membership in a merchant guild entitled them to

perform other economic functions as well, such as

mining, manufacturing, shipping, and banking.

Various liabilities imposed by the state, in-

cluding a ban on serf ownership by merchants and

the abolition of their previous monopoly over trade

and industry, kept the merchant estate small and

weak during the eighteenth and nineteenth cen-

turies. Elements of a genuine bourgeoisie did not

emerge until the early twentieth century.

Ethnic diversity contributed to the lack of unity

within the merchant estate. Each major city saw

the emergence of a distinctive merchant culture,

whether mostly European (German and English) in

St. Petersburg; German in the Baltic seaports of Riga

and Reval; Polish and Jewish in Warsaw and Kiev;

Italian, Greek, and Jewish in Odessa; or Armenian

in the Caucasus region, to name a few examples.

Moreover, importers in port cities generally favored

free trade, while manufacturers in the Central In-

dustrial Region, around Moscow, demanded high

import tariffs to protect their factories from Euro-

pean competition. These economic conflicts rein-

forced hostilities based on ethnic differences. The

Moscow merchant elite remained xenophobic and

antiliberal until the Revolution of 1905.

The many negative stereotypes of merchants in

Russian literature reflected the contemptuous atti-

tudes of the gentry, bureaucracy, intelligentsia, and

peasantry toward commercial and industrial activ-

ity. The weakness of the Russian middle class con-

stituted an important element in the collapse of the

liberal movement and the victory of the Bolshevik

party in the Russian Revolution of 1917.

See also: CAPITALISM; ECONOMY, TSARIST; FOREIGN

TRADE; GUILDS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Freeze, Gregory L. (1986). “The Soslovie (Estate) Paradigm

and Russian Social History.” American Historical Re-

view 91:11–36.

Owen, Thomas C. (1981). Capitalism and Politics in Rus-

sia: A Social History of the Moscow Merchants, 1855-

1905. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Owen, Thomas C. (1991). “Impediments to a Bourgeois

Consciousness in Russia, 1880–1905: The Estate

Structure, Ethnic Diversity, and Economic Regional-

MERCHANTS

916

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ism.” In Between Tsar and People: Educated Society and

the Quest for Public Identity in Late Imperial Russia,

ed. Edith W. Clowes, Samuel D. Kassow, and James

L. West. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rieber, Alfred J. (1982). Merchants and Entrepreneurs in

Imperial Russia. Chapel Hill: University of North Car-

olina Press.

T

HOMAS

C. O

WEN

MESKHETIAN TURKS

The Meskhetian Turks are a Muslim people who

originally inhabited what is today southwestern

Georgia. They speak a Turkic language very simi-

lar to Turkish. Deported from their homeland by

Josef V. Stalin in 1944, the Meskhetian Turks

are scattered in many parts of the former Soviet

Union. Estimates of their number range as high as

250,000. Their attempts to return to their home-

land in Georgia have been mostly unsuccessful.

While other groups deported from the Cauca-

sus region at roughly the same time were accused

of collaborating with the Nazis, Meskhetian Turk

survivors report that different reasons were given

for their deportation. Some say they were accused

of collaborating, others say they were told that the

deportation was for their own safety, and still oth-

ers were given no reason whatsoever. The depor-

tation itself was brutal, with numerous fatalities

resulting from both the long journey on crammed

railroad cars and the primitive conditions in Cen-

tral Asia where they were forced to live. Estimates

of the number of deaths range from thirty to fifty

thousand.

In the late 1950s Premier Nikita Khrushchev

allowed the Meskhetian Turks and other deported

peoples to leave their camps in Central Asia. Un-

like most of the other deported peoples, however,

the Meskhetian Turks were not allowed to return

to their ancestral homeland. The Georgian SSR was

considered a sensitive border region and as such

was off limits. The Meskhetian Turks began to dis-

perse throughout the Soviet Union, with many

ending up in the Kazakh, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz SSRs

and others in Soviet Azerbaijan and southern Eu-

ropean Russia. They were further dispersed in

1989 when several thousand Meskhetian Turks

fled deadly ethnic riots directed at them in Uzbek-

istan.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the

Meskhetian Turks have tried to return to their an-

cestral homeland in newly independent Georgia,

but they face strong opposition. Georgia already

has a severe refugee crisis, with hundreds of thou-

sands of people displaced by conflicts in Abkhazia

and South Ossetia. In addition, the substantial Ar-

menian population of the Meskhetian Turks’ tra-

ditional homeland does not want them back. The

Georgians view the Meskhetian Turks as ethnic

Georgians who adopted a Turkic language and the

Muslim religion. They insist that any Meskhetian

Turks who wish to return must officially declare

themselves Georgian, adding Georgian suffixes to

their names and educating their children in the

Georgian language.

The Meskhetian Turks are scattered across the

former Soviet Union, with the largest populations

in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Russia. In southern

European Russia’s Krasnodar Krai, the local popu-

lation of Meskhetian Turks, most of whom fled

the riots in Uzbekistan, have received particularly

rough treatment. The Meskhetian Turks of this re-

gion are denied citizenship and, according to Russ-

ian and international human rights organizations,

frequently suffer bureaucratic hassles and physical

assaults from local officials intent on driving them

away. In 1999, as a condition of membership in

the Council of Europe, the Georgian government

announced that it would allow for the return of

the Meskhetian Turks within twelve years, but de-

spite international pressure it has taken little con-

crete action in this direction.

See also: DEPORTATIONS; GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS; IS-

LAM; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALI-

TIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blandy, Charles. (1998). The Meskhetians: Turks or Geor-

gians? A People Without a Homeland. Camberley, Sur-

rey, UK: Conflict Studies Research Centre, Royal

Military Academy.

Open Society Institute. (1998). “Meskhetian Turks: So-

lutions and Human Security.” <http://www.soros

.org/fmp2/html/meskpreface.html/>.

Sheehy, Ann, and Nahaylo, Bohdan. (1980). The Crimean

Tatars, Volga Germans and Meskhetians: Soviet Treat-

ment of Some National Minorities. London: Minority

Rights Group.

J

USTIN

O

DUM

MESKHETIAN TURKS

917

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

MESTNICHESTVO

The practice of appointing men from eminent fam-

ilies to high positions in the military or govern-

ment according to social status and service record.

Mestnichestvo or “precedence” refers to a legal

practice in Muscovy whereby a military officer

sued to avoid serving in a rank, or “place” (mesto),

below a man whose family he regarded as inferior.

The practice was open only to men in the most em-

inent families and arose in the second quarter of

the sixteenth century as a result of rapid social

change in the elite. Eminent princely families join-

ing the grand prince’s service from the Grand

Duchy of Lithuania, the Khanate of Kazan, and Rus

principalities challenged the status of the estab-

lished Muscovite boyar clans. Thus mestnichestvo

arose in the process of the definition of a more com-

plex elite and was inextricably connected with the

compilation of genealogical and military service

records (rodoslovnye and razryadnye knigi).

Relative place was reckoned on the basis of fam-

ily heritage and the eminence of one’s own and

one’s ancestors’ military service. A complicated for-

mula also assigned ranks to members of large clans

so that individuals could be compared across clans.

Litigants presented their own clan genealogies and

service precedents in comparison with those of their

rival and their rival’s kinsmen, often using records

that differed from official ones. Judges were then

called upon to adjudicate cases of immense com-

plexity.

In practice few precedence disputes came to

such detailed exposition in court because the state

acted in two ways to waylay them. From the late

sixteenth century the tsar regularly declared ser-

vice assignments in a particular campaign “with-

out place,” that is, not counting against a person’s

or his clan’s dignity. Secondly, the tsar, or judges

acting in his name, peremptorily resolved suits on

the spot. Some were dismissed on the basis of ev-

ident disparity of clans (“your family has always

served below that family”), while other plaintiffs

were reassigned or their assignments declared with-

out place. Tsars themselves took an active role in

these disputes. Sources cite tsars Ivan IV, Mikhail

Fyodorovich, and Alexei Mikhailovich, among oth-

ers, castigating their men for frivolous suits. Sig-

nificantly, only a tiny number of mestnichestvo

suits were won by plaintiffs. Most resolved cases

affirmed the hierarchy established in the initial as-

signment.

Some scholars have argued that precedence al-

lowed the Muscovite elite to protect its status

against the tsars, while others suggest that it ben-

efited the state by keeping the elite preoccupied

with petty squabbling. Source evidence, however,

suggests that precedence rarely impinged on mil-

itary preparedness or tsarist authority. If any-

thing, the regularity with which status hierarchy

among clans was reaffirmed suggests that prece-

dence exerted a stabilizing affirmation of the sta-

tus quo.

In the seventeenth century the bases on which

precedence functioned were eroded. The elite had

expanded immensely to include new families of

lesser heritage, lowly families were litigating for

place, and many service opportunities were avail-

able outside of the system of place. Mestnichestvo

as a system of litigation was abolished in 1682,

while at the same time the principle of hereditary

elite status was affirmed by the creation of new ge-

nealogical books for the new elite.

See also: LEGAL SYSTEMS; MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kollmann, Nancy Shields. (1999). By Honor Bound: State

and Society in Early Modern Russia. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press.

N

ANCY

S

HIELDS

K

OLLMANN

METROPOLITAN

A metropolitan is the chief prelate in an ecclesias-

tical territory that usually coincided with a civil

province.

The metropolitan ranks just below a patriarch

and just above an archbishop, except in the con-

temporary Greek Orthodox Church, where since

the 1850s the archbishop ranks above the metro-

politan. The term derives from the Greek word for

the capital of a province where the head of the epis-

copate resides. The first evidence of its use to des-

ignate a Churchman’s rank was in the Council of

Nicaea (325

C

.

E

.) decision, which declared (canon 4;

cf. canon 6) the right of the metropolitan to con-

firm episcopal appointments within his jurisdic-

tion.

A metropolitan was first appointed to head the

Rus Church in 992. Subsequent metropolitans of

Kiev and All Rus resided in Kiev until 1299 when

MESTNICHESTVO

918

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Metropolitan Maxim (1283–1305) moved his

residence to Vladimir-on-the-Klyazma. His succes-

sor, Peter (1308–1326), began residing unofficially

in Moscow. The next metropolitan, Feognost

(1328–1353), made the move to Moscow official.

A rival metropolitan was proposed by the grand

duke of Lithuania, Olgerd, in 1354, and from then

until the 1680s there was a metropolitan residing

in western Rus with a rival claim to heading the

metropoly of Kiev and all Rus.

Until 1441, the metropolitans of Rus were ap-

pointed in Constantinople. From 1448 until 1589,

the grand prince or tsar appointed the metropoli-

tan of Moscow and all Rus following nomination

by the council of bishops. When the metropolitan

of Moscow and all Rus was raised to the status of

patriarch in 1589, the existing archbishops—those

of Novgorod, Rostov, Kazan, and Sarai—were ele-

vated to metropolitans. The Council of 1667 ele-

vated four other archbishops—those of Astrakhan,

Ryazan, Tobolsk, and Belgorod—to metropolitan

status. After the abolition of the patriarchate in

1721 by Peter I, no metropolitans were appointed

until the reign of Elizabeth, when metropolitans

were appointed for Kiev (1747) and Moscow

(1757). Under Catherine II, a third metropolitan—

for St. Petersburg—was appointed (1783). In 1917,

the patriarchate of Moscow was reestablished and

various new metropolitanates created so that by

the 1980s there were twelve metropolitans in the

area encompassed by the Soviet Union.

See also: PATRIARCHATE; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ellis, Jane. (1986). The Russian Orthodox Church: A Con-

temporary History. London: Croom Helm.

Fennell, John. (1995). History of the Russian Church to

1448. London: Longman.

Preobrazhensky, Alexander, ed. (1998). The Russian Or-

thodox Church: Tenth to Twentieth Centuries. Moscow:

Progress.

D

ONALD

O

STROWSKI

MEYERHOLD, VSEVOLOD YEMILIEVICH

(1874–1940), born Karl-Theodor Kazimir Meyer-

hold, stage director.

Among the most influential twentieth-century

stage directors, Vsevolod Meyerhold utilized ab-

stract design and rhythmic performances. His ac-

tor training system, “biomechanics,” merges acro-

batics with industrial studies of motion. Never hes-

itating to adapt texts to suit directorial concepts,

Meyerhold saw theatrical production as an art in-

dependent from drama. Born in Penza, Meyerhold

studied acting at the Moscow Philharmonic Soci-

ety (1896–1897) with theatrical reformer Vladimir

Nemirovich-Danchenko. When Nemirovich co-

founded the Moscow Art Theater with Konstantin

Stanislavsky (1897), Meyerhold joined. He excelled

as Treplev in Anton Chekhov’s Seagull (1898). Like

Treplev, Meyerhold sought new artistic forms and

left the company in 1902. He directed symbolist

plays at Stanislavsky’s Theater-Studio (1905) and

for actress Vera Kommissarzhevskaya (1906–1907).

From 1908 to 1918, Meyerhold led a double

life. As director for the imperial theaters, he created

sumptuous operas and classic plays. As experi-

mental director, under the pseudonym Dr. Daper-

tutto, he explored avant-garde directions. Meyerhold

greeted 1917 by vowing “to put the October rev-

olution into the theatre.” He headed the Narkom-

pros Theater Department from 1920 to 1921 and

staged agitprop (pro-communist propaganda). His

Soviet work developed along two trajectories: He

reinterpreted classics to reflect political issues and

premiered contemporary satires. His most famous

production, Fernand Crommelynck’s Magnificent

Cuckold (1922), used a constructivist set and bio-

mechanics. When Soviet control hardened, Meyer-

hold was labeled “formalist” and his theater

liquidated (1938). The internationally acclaimed

Stanislavsky sprang to Meyerhold’s defense, but

shortly after Stanislavsky’s death, Meyerhold was

arrested (1939). Following seven months of tor-

ture, he confessed to “counterrevolutionary slan-

der” and was executed on February 2, 1940.

See also: AGITPROP; MOSCOW ART THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Braun, Edward. (1995). Meyerhold: A Revolution in the

Theatre. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Rudnitsky, Konstantin. (1981). Meyerhold the Director, tr.

George Petrov. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

S

HARON

M

ARIE

C

ARNICKE

MIGHTY HANDFUL

Group of nationally oriented Russian composers

during the nineteenth century; the name was

MIGHTY HANDFUL

919

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

coined unintentionally by the music and art critic

Vladimir Stasov.

The “Mighty Handful” (moguchaya kuchka), also

known as the New Russian School, Balakirev

Circle, or the Five, is a group of nationalist, nine-

teenth century composers. At the end of the 1850s

the brilliant amateur musician Mily Balakirev

(1837–1920) gathered a circle of like-minded

followers in St. Petersburg with the intention of

continuing the work of Mikhail Glinka. His closest

comrades became the engineer Cesar Cui (1835–1918;

member of the group beginning in 1856), the offi-

cers Modest Mussorgsky (1839–1881, member be-

ginning in 1857), and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

(1844–1908, member beginning in 1861), and the

chemist Alexander Borodin (1833–1887, member

beginning in 1862). The spiritual mentor of the

young composers, who shared their lack of pro-

fessional musical training, was the music and art

critic Vladimir Stasov, who publicly and vehe-

mently promoted the cause of a Russian national

music separate from Western traditions, in a some-

what polarizing and polemic manner. When Stasov,

in an article for the Sankt-Peterburgskie vedomosti

(St. Petersburg News) about a “Slavic concert of

Mr. Balakirev” on the occasion of the Slavic Con-

gress in 1867, praised the “small, but already

mighty handful of Russians musicians,” he had

Glinka and Alexander Dargomyzhsky in mind as

well as the group, but the label stuck to Balakirev

and his followers. They can be considered a unit

not only because of their constant exchange of

ideas, but also because of their common aesthetic

convictions. Strictly speaking, this unity of com-

position lasted only until the beginning of the

1870s, when it began to dissolve with the grow-

ing individuation of its members.

The enthusiastic music amateurs sought to cre-

ate an independent national Russian music by tak-

ing up Russian themes, literature, and folklore and

integrating Middle-Asian and Caucasian influences,

thereby distancing it from West European musical

language and ending the supremacy of the latter in

the musical life of Russian cities. Balakirev, who had

known Glinka personally, was the most advanced

musically; his authority was undisputed among the

five musicians. He rejected classical training in mu-

sic as being only rigid routine and recommended his

own method to his followers instead: composing

should not be learned through academic courses,

but through the direct analysis of masterpieces (es-

pecially those created by Glinka, Hector Berlioz,

Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, or Ludwig van

Beethoven, the composers most venerated by the

Five). The St. Petersburg conservatory, founded in

1862 by Anton Rubinstein as a new central music

training center with predominantly German staff

was heavily criticized, especially by Balakirev and

Stasov. Instead, a Free School of Music (Bezplatnaya

muzykalnaya shkola) was founded in the same year,

and differed from the conservatory in its low tu-

ition fees and its decidedly national Russian orien-

tation. Balakirev advised his own disciples of the

Mighty Handful to go about composing great

works of music without false fear.

In spite of comparatively low productivity and

long production periods, due in part to the lack of

professional qualifications and the consequent cre-

ative crises, in part to Balakirev’s willful and metic-

ulous criticisms, and in part to the members’

preoccupation with their regular occupations, the

composers of the Mighty Handful became after

Glinka and beside Peter Tchaikovsky the founders

of Russian national art music during the nineteenth

century. An exception was Cui, whose composi-

tions, oriented towards Western models and themes,

formed a sharp contrast to what he publicly pos-

tulated for Russian music. The other members of

the Balakirev circle successfully developed specific

Russian musical modes of expression. The music

dramas Boris Godunov (1868–1872) and Khovan-

shchina (1872–1881) by Mussorgsky and Prince

Igor (1869–1887) by Borodin, in spite of their un-

finished quality, are considered among the greatest

historical operas of Russian music, whereas Rim-

sky-Korsakov achieved renown by his masterly ac-

complishment of the Russian fairy-tale and magic

opera. The symphonies, symphonic poems, and

overtures of Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Bal-

akirev stand for the beginnings and first highlights

of a Russian orchestral school. Understandably,

many of the composers’ most important works

were created when the Mighty Handful as a com-

munity had already dissolved. The personal crises

of Balakirev and Mussorgsky contributed to the cir-

cle’s dissolution, as did the increasing emancipation

of the disciples from their master, which was

clearly exemplified by Rimsky-Korsakov. He ad-

vanced to the status of professional musician,

became professor at the St. Petersburg conserva-

tory (1871), and diverged from the others increas-

ingly over time in his creative approaches. In sum,

the Mighty Handful played a crucial role in the for-

mation of Russian musical culture at the crossroads

of West European influences and strivings for na-

tional independence. Through the intentional use of

MIGHTY HANDFUL

920

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

historical and mythical Russian themes, the works

of the Mighty Handful have made a lasting con-

tribution to the national culture of recollection in

Russia far beyond the nineteenth century.

See also: MUSIC; NATIONALISM IN THE ARTS; RIMSKY-

KORSAKOV, NIKOLAI ANDREYEVICH; STASOV, VLADIMIR

VASILIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, David; Abraham, Gerald; Lloyd-Jones, David;

Garden, Edward. (1986). Russian Masters, Vol. I:

Glinka, Borodin, Balakirev, Musorgsky, Tchaikovsky.

New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Garden, Edward. (1967). Balakirev: A Critical Study of His

Life and Music. London: Faber & Faber.

M

ATTHIAS

S

TADELMANN

MIGRATION

Across time and cultures individuals migrate to im-

prove their lives, seek better opportunities, or flee

unbearable conditions. In Russian history, migra-

tion highlights social stratification, underscores the

importance of social management, and provides in-

sight into post-Soviet population change. Migra-

tion motivations in Russia were historically

influenced by direct governmental control, provid-

ing a unique case for assessing barriers to migra-

tion and a window into state and society relations.

The earliest inhabitants of the region now

known as Russia were overrun by the in-migration

of several conquering populations, with Cimmeri-

ans, Scythians (700

B

.

C

.

E

.), Samartians (300

B

.

C

.

E

.),

Goths (200

C

.

E

.), Huns (370

C

.

E

.), Avars, and Khaz-

ars moving into the territory to rule the region.

Mongol control (1222) focused on manipulating

elites and extracting taxes, but not in-migration.

When Moscow later emerged as an urban settle-

ment, eastern Slavs spread across the European

plain. Ivan III (1462–1505) pushed expansion south

and west, while Ivan IV (1530–1584) pushed east

towards Siberia. Restrictions on peasant mobility

made migration difficult, yet some risked every-

thing to illegally flee to the southern borderlands

and Siberia.

The legal code of 1649 eradicated legal migration.

Solidifying serfdom, peasants were now owned by

the gentry. Restrictions on mobility could be cir-

cumvented. Ambitious peasants could become illegal

or seasonal migrants, marginalized socially and eco-

nomically. By 1787 between 100,000 and 150,000

peasants resided seasonally in Moscow, unable to ac-

quire legal residency, forming an underclass unable

to assimilate into city life. Restricted mobility hin-

dered the development of urban labor forces for in-

dustrialization in this period, also marked by the use

of forced migration and exile by the state.

The emancipation of serfs (1861) increased mo-

bility, but state ability to control migration re-

mained. Urbanization increased rapidly—according

to the 1898 census, nearly half of all urbanites were

migrants. The Stolypin reforms (1906) further

spurred migration to cities and frontiers by en-

abling withdrawal from rural communes. Over

500,000 peasants moved into Siberia yearly in the

early 1900s. Over seven million refugees moved

into Russia by 1916, challenging ideas of national

identity, highlighting the limitations of state, and

crystallizing Russian nationalism. During the Rev-

olution and civil war enforcement of migration re-

strictions were thwarted, adding to displacement,

settlement shifts, and urban growth in the 1920s.

The Soviet passport system reintroduced state

control over migration in 1932. Passports con-

tained residency permits, or propiskas, required for

legal residence. The passport system set the stage

for increased social control and ideological empha-

sis on the scientific management of population.

Limiting rural mobility (collective farmers did not

receive passports until 1974), restricting urban

growth, the exile of specific ethnic groups (Ger-

mans, Crimean Tatars, and others), and directing

migration through incentives for movements into

new territories (the Far East, Far North, and north-

ern Kazakhstan) in the Soviet period echoed previ-

ous patterns of state control. As demographers

debated scientific population management, by the

late Soviet period factors such as housing, wages,

and access to goods exerted strong influences on

migration decision making. Attempts to control

migration in the Soviet period met some success in

stemming urbanization, successfully attracting

migrants to inhospitable locations, increasing re-

gional mixing of ethnic and linguistic groups across

the Soviet Union, and blocking many wishing to

immigrate.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991,

migration restrictions were initially minimized, but

migration trends and security concerns increased

interest in restrictions by the end of the twentieth

century. Decreased emigration control led to over

MIGRATION

921

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

100,000 people leaving Russia yearly between 1991

and 1996, dampened only by restrictions on im-

migration from Western countries. Russia’s popu-

lation loss has been offset by immigration from the

near abroad, where 25 million ethnic Russians

resided in 1991. Legal, illegal, and seasonal mi-

grants were attracted from the near abroad by the

relative political and economic stability in Russia,

in addition to ethnic and linguistic ties. Yet, the

flow of immigrants declined in the late 1990s.

Refugees registered in Russia numbered nearly one

million in 1998. Internally, migration patterns fol-

low wages and employment levels, and people left

the far eastern and northern regions. Internal dis-

placement emerged in the south during the 1990s,

from Chechnya. By the late 1990s, the challenges

of migrant assimilation and integration were key

public issues, and interest in restricting migration

rose. While market forces had begun to replace di-

rect administrative control over migration in Rus-

sia by the end of the 1990s, concerns over migration

and increasing calls for administrative interven-

tions drew upon a long history of state manage-

ment of population migration.

See also: DEMOGRAPHY; IMMIGRATION AND EMIGRATION;

LAW CODE OF 1649; PASSPORT SYSTEM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bradley, J. (1985). Muzhik and Muscovite: Urbanization

in Late Imperial Russia. Los Angeles: University of

California Press.

Brubaker, Rodgers. (1995). “Aftermaths of Empire and

the Unmixing of Peoples: Historical and Compara-

tive Perspectives” Ethnic and Racial Studies 18

(2):189–218.

Buckley, Cynthia J. (1995). “The Myth of Managed Mi-

gration.” Slavic Review 54 (4):896–916.

Gatrell, Peter. (1999). A Whole Empire Walking: Refugees

in Russia During World War I. Bloomington: Indiana

University Press.

Lewis, Robert and Rowlands, Richard. (1979). Population

Redistribution in the USSR: Its Impact on Society

1897–1977. New York: Praeger Press.

Zaionchkovskaya, Zhanna A. (1996). “Migration Pat-

terns in the Former Soviet Union” In Cooperation and

Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Implications for Mi-

gration, eds. Jeremy R. Azrael, Emil A. Payin, Kevin

MIGRATION

922

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

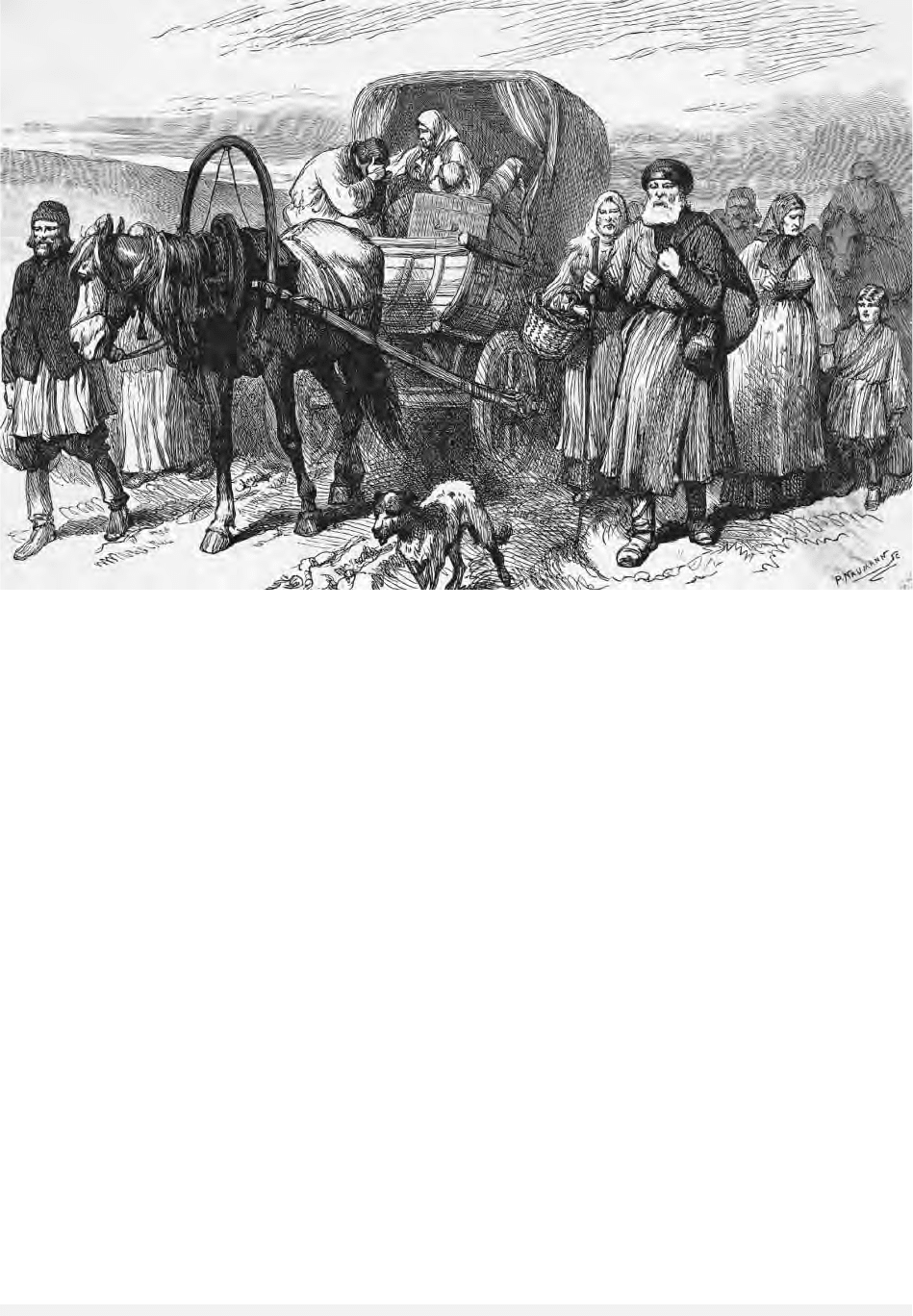

Nineteenth-century engraving shows a caravan of Russian peasants migrating. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS