Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ity and conscientiousness . . . a person of the rarest

erudition and generous spirit, who educated a

whole galaxy of worthy students” (Kultura No. 36,

7–13 October, 1999, 1). Another said, “[He] took

the helm of the ship of Russian culture and steered

it to a hopefully better world.” He was a greatly

talented historian and many of his more than one

thousand publications were known throughout the

world’s academic community. By his life’s end he

had been granted honorary titles by sixteen na-

tional academies and European universities, as well

as several high honors from his native land, in-

cluding Hero of Soviet Labor. He served as a re-

searcher in various Soviet academic institutions of

renown, gained the title of university professor,

and for his seminal work on the Russian classic,

Lay of Igor’s Campaign, was received into the Soviet

Academy of Sciences. His very active life also led

him to membership in the Russian Duma after the

fall of the Soviet Union.

See also: ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; HISTORIOGRAPHY; LAY

OF IGOR’S CAMPAIGN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Likhachev, Dmitry S. (2000). Reflections on the Russian

Soul: A Memoir. Budapest, Hungary: Central Euro-

pean University Press.

J

OHN

P

ATRICK

F

ARRELL

LISHENTSY See DISENFRANCHIZED PERSONS.

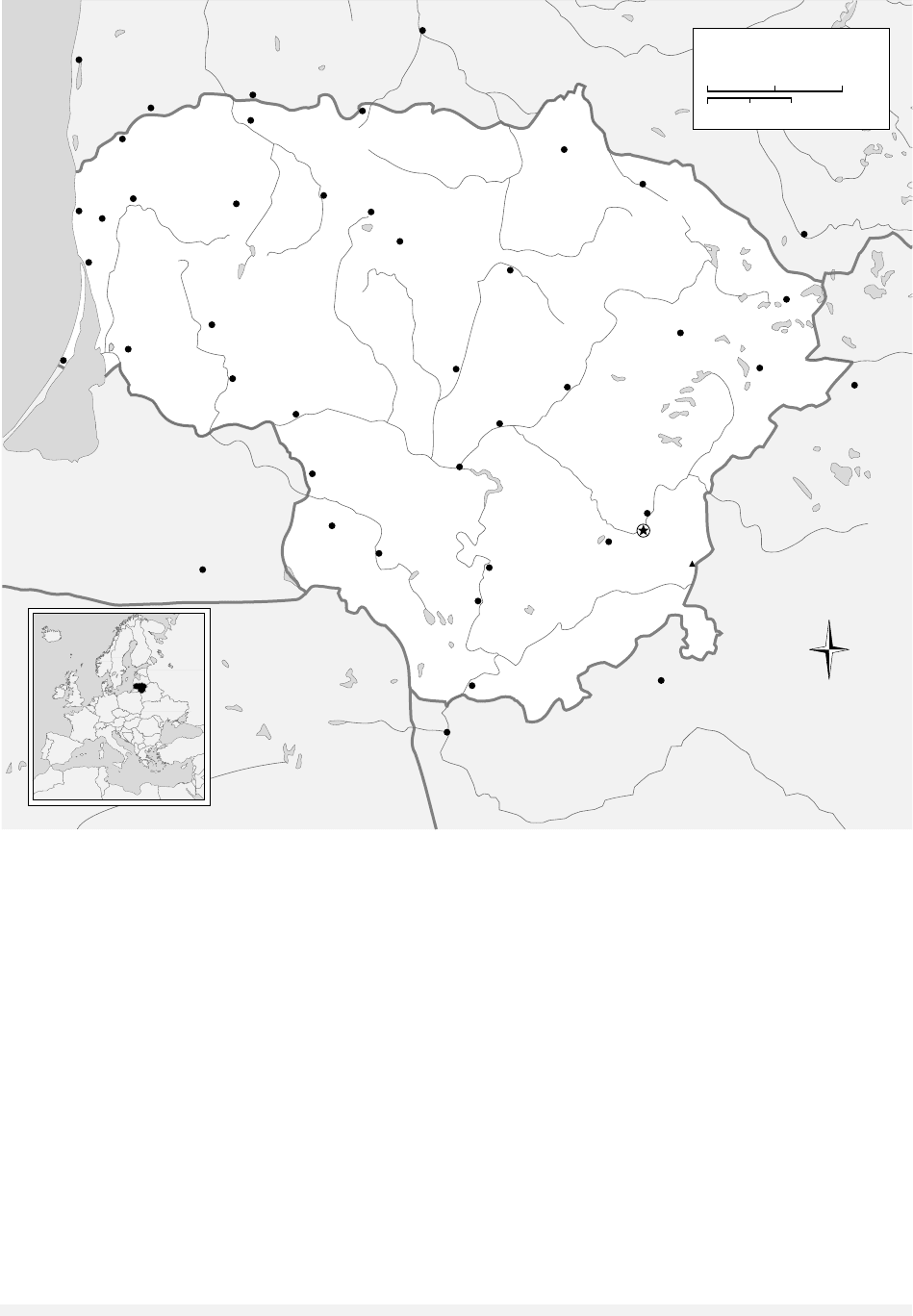

LITHUANIA AND LITHUANIANS

Located on the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea,

Lithuania has been an independent republic since

1991. Encompassing 66,200 square kilometers, it

has a population (2001) of 3,491,000 inhabitants,

of whom 67.2 percent live in cities and 32.8 per-

cent in rural areas. Over 80 percent of the popula-

tion is Lithuanian, about 9 percent Russian, and 7

percent Polish.

Lithuanians first established a government in

the thirteenth century to resist the Teutonic

Knights attacking from the West. In 1251 the

Lithuanian ruler Mindaugas accepted Latin Chris-

tianity, and in 1253 received the title of king, but

his successors were known as Grand Dukes. When

Tatars overran the Russian principalities to the East,

the Grand Duchy expanded into the territory that

today makes up Belarus and Ukraine. At its height,

at the end of the fourteenth century, although the

Lithuanians are a Baltic and not a Slavic people,

Lithuania had a majority of East Slavs in its pop-

ulation, and for a time it challenged the Grand

Duchy of Moscow as the “collector of the Russian

lands.”

Faced by Moscow’s growing strength, Lithu-

anian leaders turned to Poland for help, and

through a series of agreements made between 1385

and 1387, the two states formed a union, solidi-

fied by the marriage of the two rulers, Jagiello and

Jadwiga, and by the reintroduction of Latin Chris-

tianity through the Polish structure of the Roman

Catholic church. (Lithuania had reverted to pagan-

ism after Mindaugas’s abdication in 1261.) Rein-

forced by the Union of Lublin in 1569, the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth continued until

the Partitions of Poland at the end of the eighteenth

century. In 1795 the Third Partition of Poland

brought Russian rule to most of what today con-

stitutes Lithuania.

Russian authorities attempted to wean the

Lithuanians from the Polish influences that had

dominated during the period of the Common-

wealth. The Russians banned the use of the name

“Lithuania” (Litva) and administered the territory

as part of the “Northwest Region.” After the Pol-

ish uprisings of 1831 and 1863, the authorities

helped Lithuanians in some ways but also tried to

force them to adopt the Cyrillic alphabet. At the

same time, the authorities limited the economic

development of the region, which lay on the

Russian-German border. Under these conditions, a

Lithuanian national consciousness emerged, and

with it the goal of cultural independence from the

Poles and eventual political independence from

Russia.

The Lithuanians received their opportunity in

the course of World War I. On February 16, 1918,

after almost three years of German occupation, the

Lithuanian Council (Taryba) declared the country’s

independence, but a provisional government began

to function only after the German defeat in No-

vember 1918. Russian efforts in 1919 to reclaim

the region in the form of a Lithuanian Soviet So-

cialist Republic failed, and in May 1920 a Con-

stituent Assembly met and formalized the state

structure.

The First Republic’s foreign policy focused on

Lithuania’s claim to the city of Vilnius as its his-

toric capitol. The Poles had seized the city in 1920,

and as a result, Lithuania tended to align itself with

LITHUANIA AND LITHUANIANS

863

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Germany and the Soviet Union as part of an anti-

Versailles camp. In 1939, by the terms of the Nazi-

Soviet Non-Aggression pact, Germany and the

Soviet Union were to divide Eastern Europe, and

Lithuania fell into the Soviet orbit. In 1940 Soviet

forces overthrew the authoritarian regime that had

ruled Lithuania since 1926, and Moscow directed

the country’s incorporation into the Soviet Union

as a constituent republic.

The 1940s brought destruction and havoc to

Lithuania. In 1940 and 1941, Soviet authorities de-

ported thousands of Lithuanian citizens of all na-

tionalities into the interior of the USSR. When the

Germans invaded in 1941, some local people joined

with the Nazi forces in the massacre of the vast

majority of the Jewish population of Lithuania. (In

1940 and 1941 Jews had constituted almost 10

percent of Lithuania’s population.) When the So-

viet army returned in 1944 and 1945, Lithuanian

resistance erupted and continued into the early

1950s. Thousands died in the fighting, and Soviet

authorities deported at least 150,000 persons to

Siberia. (The exact number of killings and deporta-

tions is subject to considerable dispute.)

Under Soviet rule the Lithuanian social struc-

ture changed significantly. Before World War II,

LITHUANIA AND LITHUANIANS

864

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Juozapines

985 ft.

292 m.

Kurshskiy

Zaliv

Baltic

Sea

¯

N

e

m

u

n

a

s

J

u

r

a

D

u

b

y

s

a

N

e

v

e

z

i

s

ˇ

S

v

e

n

t

o

j

i

N

e

r

i

s

N

e

m

u

n

a

s

M

e

r

k

y

s

M

i

n

i

j

a

V

e

n

t

a

M

u

ˇs

a

Lukastas

¯

.

¯

Druskininkai

Hrodna

Lida

Pastavy

Alytus

Punia

Lentvaris

Naujoji

Vilnia

Marijampole

·

Jonava

Kedainiai

·

Jurbarkas

Sintautai

Chernyakhovsk

Taurage

·

ˇ

Silute

·

Utena

Ignalina

Snieckus

Panemunis

Ukmerge

·

Radviliˇskis

Birzai

Zagare

Gramzda

Ezere

Skoudas

Daugavpils

Jelgava

Leipaja¯

Kurˇsenai

·

Mazeikiai

Palanga

Kartena

Kretinga

Nida

Telˇsiai

ˇ

Silale

Vilkaviˇskis

Klaipeda

·

ˇ

Siauliai

Panevezys

Vilnius

Kaunas

.

RUSSIA

POLAND

LATVIA

BELARUS

W

S

N

E

Lithuania

LITHUANIA

40 Miles

0

0

40 Kilometers

20

20

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

Lithuania, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

the majority of Lithuanians were peasants, and

even at the beginning of the twenty-first century,

many urban dwellers still maintained some sort of

psychological link with the land. The Soviet gov-

ernment, however, collectivized agriculture and

pushed industrialization, moving large numbers of

people into the cities and developing new industrial

centers. By the 1960s, after the violent resistance

had failed, more Lithuanians began to enter the So-

viet system, becoming intellectuals, economic lead-

ers, and party members. Emigré Lithuanian

scholars often estimated that only 5 to 10 percent

of Lithuanian party members were “believers,”

while the majority had joined out of necessity.

In 1988, after Mikhail Gorbachev had loosened

Moscow’s controls throughout the Soviet Union,

the Lithuanians became a focus of the process of

ethno-regional decentralization of the Soviet state.

Gorbachev’s program of reform encouraged local

initiative that, in the Lithuanian case, quickly took

on national coloration. The Lithuanian Movement

for Perestroika, now remembered as Sajudis, mobi-

lized the nation first around cultural and ecologi-

cal issues, and later, in a political campaign, around

the goal of reestablishment of independence.

Gorbachev quickly lost control of Lithuania,

and he successively resorted to persuasion, eco-

nomic pressure, and finally violence to restrain the

Lithuanians. After the Lithuanian Communist

Party declared its independence of the Soviet party

in December 1989, worldwide media watched Gor-

bachev travel to Lithuania in January to persuade

the Lithuanians to relent. He failed, and after

Sajudis led the Lithuanian parliament on March 11,

1990, to declare the reconstitution of the Lithuan-

ian state, Gorbachev imposed an economic block-

ade on the republic. This, too, failed, and in January

1991, world media again watched as Soviet troops

attacked key buildings in Vilnius and the Lithua-

nians passively resisted Moscow’s efforts to

reestablish its authority. The result was a stale-

mate. Finally, after surviving the so-called “August

Putsch” in Moscow, Gorbachev, under Western

pressure, recognized the reestablishment of inde-

pendent Lithuania.

See also: BRAZAUSKAS, ALGIRDAS; LANDSBERGIS, VYTAU-

TAS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST; POLAND; VILNIUS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Eidintas, Alfonsas, and Zalys, Vytautas. (1997). Lithua-

nia in European Politics: The Years of the First Repub-

lic, 1918–1940. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Misiunas, Romuald, and Taagepera, Rein. (1992). The

Baltic States: Years of Dependence, 1940–1990, ex-

panded and updated ed. Berkeley: University of Cal-

ifornia Press.

Senn, Alfred Erich. (1959). The Emergence of Modern

Lithuania. New York: Columbia University Press.

Senn, Alfred Erich. (1990). Lithuania Awakening. Berke-

ley: University of California Press.

Senn, Alfred Erich. (1995). Gorbachev’s Failure in Lithua-

nia. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Vardys, V. Stanley. (1978). The Catholic Church, Dissent,

and Nationality in Soviet Lithuania. Boulder, CO: East

European Quarterly.

A

LFRED

E

RICH

S

ENN

LITVINOV, MAXIM MAXIMOVICH

(1876–1951), old Bolshevik, leading Soviet diplo-

mat, and commissar for foreign affairs.

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov was born Meer

Genokh Moisevich Vallakh in Bialystok, a small

city in what is now Poland. He joined the socialist

movement in the 1890s and sided with Vladimir

Lenin when the Social Democratic Party split into

Bolshevik and Menshevik factions. From 1898 to

1908, he smuggled guns and propaganda into the

empire, but having achieved little, he emigrated to

Britain. There he married an English woman and

led a quiet, conventional life, even becoming a

British subject. During the October Revolution, he

served briefly as the Soviet representative to Lon-

don but was expelled from Britain for “revolution-

ary activities” in October 1918. In Moscow he

became a deputy commissar for foreign affairs and

frequently negotiated with the Western powers for

normal diplomatic relations, to little success. How-

ever, Litvinov did conclude a 1929 nonaggression

pact with the USSR’s western neighbors, including

Poland and the Baltic states.

From 1930 to 1939 Litvinov served as com-

missar for foreign affairs. In 1931 he negotiated a

nonaggression treaty with France, an extremely

anti-Soviet state that had become worried about an

increasingly unstable Germany. Soon after Adolf

Hitler came to power, Litvinov initiated alliance

talks with France, finding a partner in Louis Bar-

thou, the foreign minister. In December 1933, the

Soviet Communist Party leadership formally ap-

proved Litvinov’s proposal both for a military al-

liance with France and for the Soviet Union’s

LITVINOV, MAXIM MAXIMOVICH

865

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

entrance into the League of Nations. Talks took a

tortuous course, but in June 1934, Barthou and

Litvinov agreed on a eastern pact of mutual assis-

tance that would be guaranteed by a separate

Franco-Soviet treaty of mutual assistance.

For several reasons, however, these treaties

proved ineffectual. First of all, Barthou was assas-

sinated in October 1934, and Pierre Laval, an ad-

vocate of good relations with Germany, replaced

him. Moreover, the British were hostile to close re-

lations with Moscow, and France was generally

unwilling to act without London’s support. Finally,

in 1937, Stalin ordered the decimation of the Red

Army’s leadership at the same time he was terror-

izing the entire nation. To the already suspicious

West, it seemed clear that the USSR could not pos-

sibly be a reliable ally. Litvinov realized the dam-

age the Great Terror wrought on Soviet foreign

policy but was powerless in domestic politics. Ig-

nored and rebuffed at virtually every turn by the

West, Litvinov was replaced by Stalin’s close asso-

ciate, Vyacheslav Molotov, in May 1939, four

months before the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

With the German invasion of the USSR in June

1941, Stalin appointed Litvinov ambassador to the

United States. For the next two years, Litvinov con-

stantly urged the West to open a second front in

France. Angered at Litvinov’s lack of success, Stalin

recalled him in 1943. He served as a deputy com-

missar for foreign affairs, making many proposals

to Stalin advocating Great Power cooperation after

the war. This effort failed, and Litvinov eventually

understood that Stalin saw security not in terms

of cooperation with the West, but in the building

of a bulwark of satellite states on the USSR’s west-

ern border. Two months before his final dismissal

in August 1946, Litvinov told the American jour-

nalist Richard C. Hottelet that it was pointless for

the West to hope for good relations with Stalin.

Perhaps the most remarkable and mysterious fact

of Litvinov’s long career is that he died a natural

death.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; FRANCE, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Phillips, Hugh. (1992). Between the Revolution and the

West: A Political Biography of Maxim M. Litvinov.

Boulder, CO: Westview.

Sheinis, Zinovii. (1990). Maxim Litvinov. Moscow: Progress

Publishers.

H

UGH

P

HILLIPS

LIVING CHURCH MOVEMENT

Also known as the Renovationist Movement, the

Living Church Movement, a coalition of clergy and

laity, sought to combine Orthodox Christianity

with the social and political goals of the Soviet gov-

ernment between 1922 and 1946. The movement’s

names reflected fears that Orthodoxy faced extinc-

tion after the Bolshevik Revolution. Renovationists

hoped to renew their church through reforms in

liturgy, practice, and the rules on clergy marriage.

The movement began in response to the revo-

lutions of 1905 and 1917. Parish priests in Petro-

grad formed the Group of Thirty-Two in 1905 and

proposed a liberal program for church administra-

tion that would allow married parish priests, not

just celibate monastic priests, to become bishops.

This group joined advocates of Christian socialism

in a Union for Church Regeneration that advocated

the separation of church and state, greater democ-

racy within the church, and the use of modern

Russian instead of medieval Old Church Slavonic in

the Divine Liturgy. Repressed after 1905, the re-

form movement reappeared in 1917 only to wither

from lack of widespread Orthodox support.

The Living Church Movement appeared during

the famine of 1921–1922, thanks in large part to

Bolshevik suspicions that Orthodox bishops were

plotting counterrevolution. The Politburo approved

a plan for splitting the church through a public

campaign to seize church treasures for famine re-

lief. Bolshevik leaders secretly wanted to strip the

church of valuables that might be used to finance

political opposition. Patriarch Tikhon Bellavin and

other bishops opposed the government’s plan to

seize sacred icons, chalices, and patens. A small

group of clergy led by Alexander Vvedensky,

Vladimir Krasnitsky, and Antonin Granovsky used

covert government aid to set up a rival national

Orthodox organization that supported confiscation

of church valuables, expressed loyalty to the So-

viet regime, and promoted internal church reforms.

When Patriarch Tikhon unexpectedly abdicated

in May 1922, Living Church leaders formed a

Supreme Church Administration and pushed for

revolution in the church by imitating the success-

ful tactics of the Bolsheviks. Renovationists tried to

force the church to accept radical reforms in

liturgy, administration, leadership, and doctrine.

Parish clergy responded favorably to proposed

changes; bishops and laity overwhelmingly rejected

them. Government authorities threatened, arrested,

LIVING CHURCH MOVEMENT

866

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and exiled opponents to the Living Church, thereby

further eroding popular support for reform.

Internal divisions within the Supreme Church

Administration also weakened the movement.

Three competing renovationist parties emerged.

The Living Church Group of Archpriest Krasnitsky

promoted church revolution led by parish priests.

This group was more interested in giving greater

power to parish priests by allowing them to re-

marry and to become bishops than in changing

canons and dogma. Bishop Granovskii organized a

League for Church Regeneration that espoused

democracy in the church. The league appealed to

conservative lay believers because it promised them

a greater voice in church affairs and defended tra-

ditional Orthodox beliefs and practices. A third ren-

ovationist party, the League of Communities of the

Ancient Apostolic Church led by Archpriest Vve-

densky, combined Granovsky’s democratic princi-

ples and Krasnitsky’s reform proposals with

Vvedensky’s passion for Christian socialism.

Infighting among renovationist groups threat-

ened to destroy the movement, so the Soviet gov-

ernment forced them to reconcile. The reunified

Living Church gained control over nearly 70 per-

cent of Russian Orthodox parish churches by the

time their national church council convened in May

1923. The council defrocked Patriarch Tikhon and

condemned his anti-Soviet activity. It also approved

limited church reforms, including the abolition of

the patriarchate and the ordination of married bish-

ops, and proclaimed the church’s loyalty to the

regime.

By June 1923 the Soviet government became

worried over the strength of renovationism. The

Politburo decided to release Tikhon from jail after

he agreed in writing to acknowledge his crimes and

to promise loyalty to the government. Orthodox

believers and clergy immediately rallied to him. The

reformers reorganized in order to stop defections to

the patriarchate. All renovationist parties were

banned, most reforms were abandoned, and the

Supreme Church Administration became the Holy

Synod led by monastic bishops. Granovsky and

Krasnitsky refused to accept these changes and were

pushed aside. Vvedensky joined the Holy Synod in

a reduced role.

The Renovationist Movement lost support

throughout the 1920s, despite this reorganization

and an attempt to reunite the church by calling a

second renovationist national church council in Oc-

tober 1925. Most Orthodox believers saw everyone

in the Living Church Movement as traitors who

had sold out to the Communists. The movement

declined dramatically throughout the 1930s as did

the Orthodox church in general. The Living Church

Movement experienced a short lived revival during

the first years of World War II, when Soviet per-

secution of religion eased and Vvedensky became

leader of the movement. In September 1943 Josef

Stalin permitted senior patriarchal bishops to rein-

state a national church administration. A month

later, he approved a plan to merge renovationist

parishes with the Moscow patriarchate. Vvedensky

opposed this decision, but his death in July 1946

officially ended the Living Church Movement. For

decades afterward, however, Orthodox believers

used “Living Church” and “Renovationist” as syn-

onyms for religious traitors.

See also: FAMINE OF 1921–1922; ORTHODOXY; RUSSIAN

ORTHODOX CHURCH; TIKHON, PATRIARCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Curtiss, John S. (1952). The Russian Church and the So-

viet State, 1917–1950. Boston: Little, Brown.

Freeze, Gregory L. (1995). “Counter-reformation in

Russian Orthodoxy: Popular Response to Religious

Innovation, 1922–1925.” Slavic Review 54:305–339.

Roslof, Edward E. (2002). Red Priests: Renovationism,

Russian Orthodoxy, and Revolution, 1905–1946.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Walters, Philip. (1991). “The Renovationist Coup: Per-

sonalities and Programmes.” In Church, Nation and

State in Russia and Ukraine, ed. Geoffrey A. Hosking.

London: MacMillan.

E

DWARD

E. R

OSLOF

LIVONIAN WAR

The Livonian War (1558–1583), for the possession

of Livonia (historic region that became Latvia and

Estonia) was first between Russia and the knightly

Order of Livonia, and then between Russia and Swe-

den and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The outbreak of war was preceded by Russ-

ian–Livonian negotiations resulting in the 1554

treaty on a fifteen–year armistice. According to this

treaty, Livonians were to pay annual tribute to

the Russian tsar for the city of Dorpat (now Tartu),

on grounds that the city (originally known as

“Yuriev”) belonged formerly to Russian princes, an-

cestors of Ivan IV. Using the overdue payment of

LIVONIAN WAR

867

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

this Yuriev tribute as a pretext, the tsar declared

war on Livonia in January 1558.

As for Ivan IV’s true reasons for beginning the

war, two possibilities have been suggested. The first

was offered in the 1850s by Russian historian

Sergei Soloviev, who presented Ivan the Terrible as

a precursor of Peter the Great in his efforts to gain

harbors on the Baltic Sea and thus to establish di-

rect economic relations with European countries.

Until 1991 this explanation remained predominant

in Russian and Soviet historiography; it was also

shared by some Swedish and Danish scholars.

However, from the 1960s on, the thesis of eco-

nomic (trade) interests underlying Ivan IV’s deci-

sion to make war on Livonia has been subjected to

sharp criticism. The critics pointed out that the tsar,

justifying his military actions in Livonia, never re-

ferred to the need for direct trade with Europe; in-

stead he referred to his hereditary rights, calling

Livonia his patrimony (votchina). The alternative

explanation proposed by Norbert Angermann

(1972) and supported by Erik Tiberg (1984) and,

in the 1990s, by some Russian scholars (Filyushkin,

2001), emphasizes the tsar’s ambition for expand-

ing his power and might.

It is most likely that Ivan IV started the war

with no strategic plan in mind: He just wanted to

punish the Livonians and force them to pay the

contribution and fulfil all the conditions of the pre-

vious treaty. The initial success gave the tsar hope

of conquering all Livonia, but here his interests

clashed with the interests of Poland–Lithuania and

Sweden, and thus a local conflict grew into a long

and exhaustive war between the greatest powers of

the Baltic region.

As the war progressed, Ivan IV changed allies

and enemies; the scene of operations also changed.

So, in the course of the war one can distinguish

four different periods: 1) from 1558 to 1561, the

period of initial Russian success in Livonia; 2) the

1560s, the period of confrontation with Lithuania

and peaceful relations with Sweden; 3) from 1570

to 1577, the last efforts of Ivan IV in Livonia; and

4) from 1578 to 1582, when severe blows from

Poland–Lithuania and Sweden forced Ivan IV to give

up all his acquisitions in Livonia and start peace

negotiations.

During the campaign of 1558, Russian armies,

encountering no serious resistance, took the im-

portant harbor of Narva (May 11) and the city of

Dorpat (July 19). After a long pause (an armistice

from March through November 1559), in 1560

Russian troops undertook a new offensive in Livo-

nia. On August 2 the main forces of the Order were

defeated near Ermes (now Ergeme); on August 30

an army led by prince Andrei Kurbsky captured the

castle of Fellin (now Vilyandy).

As the collapse of the enfeebled Livonian Order

became evident, the knighthood and cities of Livo-

nia began to seek the protection of Baltic powers:

Lithuania, Sweden, and Denmark. In 1561 the

country was divided: The last master of the Order,

Gottard Kettler, became vassal of Sigismund II Au-

gustus, the king of Poland and grand duke of

Lithuania, and acknowledged sovereignty of the

latter over the territory of the abolished Order; si-

multaneously the northern part of Livonia, in-

cluding Reval (now Tallinn), was occupied by the

Swedish troops.

Regarding Sigismund II as his principal rival in

Livonia and trying to ally with Erik XIV of Swe-

den, Ivan IV declared war on Lithuania in 1562. A

large Russian army, led by the tsar himself, be-

sieged the city of Polotsk on the eastern frontier of

the Lithuanian duchy and seized it on February 15,

1563. In the following years Lithuanians managed

to avenge this failure, winning two battles in 1564

and capturing two minor fortresses in 1568, but

no decisive success was achieved.

By the beginning of the 1570s the international

situation had changed again: A coup d’état in Swe-

den (Erik XIV was dethroned by his brother John

III) put an end to the Russian–Swedish alliance;

Poland and Lithuania (in 1569 the two states united

into one, Rzecz Pospolita), on the contrary, adhered

to a peaceful policy during the sickness of King

Sigismund II Augustus (d. 1572) and periods of in-

terregnum (1572–1573, 1574–1575). Under these

circumstances Ivan IV tried to drive Swedish forces

out of northern Livonia: Russian troops and the

tsar’s vassal, Danish duke Magnus (brother of Fred-

erick II of Denmark), besieged Revel for thirty weeks

(August 21, 1570–March 16, 1571), but in vain.

The alliance with the Danish king proved its inef-

ficiency, and the raids of Crimean Tartars (for

instance, the burning of Moscow by Khan Devlet–

Girey on May 24, 1571) made the tsar postpone

further actions in Livonia for several years.

In 1577 Ivan IV made his last effort to conquer

Livonia; his troops occupied almost the entire coun-

try (except for Reval and Riga). Next year the war

entered its final phase, fatal to the Russian cause in

Livonia.

LIVONIAN WAR

868

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

In 1578 Russian troops in Livonia were defeated

by combined Polish–Lithuanian and Swedish forces

near the fortress Venden (now Tsesis), and the

tsar’s vassal, duke Magnus, joined the Polish side.

In 1579 the Polish king, Stephen Bathory, a tal-

ented general, recaptured Polotsk; the following

year, he invaded Russia and devastated the Pskov

region, having taken the fortresses of Velizh and

Usvyat and having burned Velikiye Luky. During

his third Russian campaign in August 1581,

Bathory besieged Pskov; the garrison led by prince

Ivan Shuisky repulsed thirty–one assaults. At the

same time the Swedish troops seized Narva. With-

out allies, Ivan IV sought peace. On January 15,

1582, the treaty concluded in Yam Zapolsky put

an end to the war with Rzecz Pospolita: Ivan IV

gave up Livonia, Polotsk, and Velizh (Velikiye Luky

was returned to Russia). In 1583 the armistice with

Sweden was concluded, yielding Russian towns

Yam, Koporye, and Ivangorod to the Swedish side.

The failure of the Livonian war spelled disaster

for Ivan IV’s foreign policy; it weakened the posi-

tion of Russia towards its neighbors in the west

and north, and the war was calamitous for the

northwestern regions of the country.

See also: IVAN IV

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Esper, Thomas. (1966). “Russia and the Baltic, 1494-

1558.” Slavic Review 25:458-474.

Kirchner, Walter. (1954). The Rise of Baltic Question.

Newark: University of Delaware Press.

M

IKHAIL

M. K

ROM

LOBACHEVSKY, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

(1792–1856), mathematician; creator of the first

non-Euclidean geometry.

Nikolai Lobachevsky was born in Nizhny Nov-

gorod to the family of a minor government offi-

cial. In 1809 he enrolled in Kazan University,

selecting mathematics as his major field. From

Martin Bartels and Franz Bronner, German immi-

grant professors, he learned the fundamentals of

trigonometry, analytical geometry, celestial me-

chanics, differential calculus, the history of math-

ematics, and astronomy. Bronner also introduced

him to the current controversies in the philosophy

of science.

In 1811 Lobachevsky was granted a magister-

ial degree, and three years later he was appointed

instructor in mathematics at Kazan University. His

first teaching assignment was trigonometry and

number theory as advanced by Carl Friedrich

Gauss. In 1816 he was promoted to the rank of

associate professor. In 1823 he published a gym-

nasium textbook in geometry and, in 1824, a text-

book in algebra.

Lobachevsky’s strong interest in geometry was

first manifested in 1817 when, in one of his teach-

ing courses, he dwelt in detail on his effort to ad-

duce proofs for Euclid’s fifth (parallel) postulate. In

1826, at a faculty meeting, he presented a paper

that showed that he had abandoned the idea of

searching for proofs for the fifth postulate; in con-

trast to Euclid’s claim, he stated that more than

one parallel could be drawn through a point out-

side a line. On the basis of his postulate, Lobachevsky

constructed a new geometry including, in some

opinions, Euclid’s creation as a special case. Al-

though the text of Lobachevsky’s report was not

preserved, it can be safely assumed that its con-

tents were repeated in his “Elements of Geometry,”

published in the Kazan Herald in 1829–1830. In the

meantime, Lobachevsky was elected the rector of

the university, a position he held until 1846.

In order to inform Western scientists about his

new ideas, in 1837 Lobachevsky published an ar-

ticle in French (“Geometrie imaginaire”) and in

1840 a small book in German (Geometrische Unter-

suchungen zur Theorie der Parallellinien). His article

“Pangeometry” appeared in Russian in 1855 and in

French in 1856, the year of his death. At no time

did Lobachevsky try to invalidate Euclid’s geome-

try; he only wanted to show that there was room

and necessity for more than one geometry. After

becoming familiar with the new geometry, Carl

Friedrich Gauss was instrumental in Lobachevsky’s

election as an honorary member of the Gottingen

Scientific Society.

After the mid-nineteenth century, Lobachevsky’s

revolutionary ideas in geometry began to attract

serious attention in the West. Eugenio Beltrami in

Italy, Henri Poincare in France, and Felix Klein in

Germany contributed to the integration of non-

Euclidean geometry into the mainstream of mod-

ern mathematics. The English mathematician

William Kingdon Clifford attributed Copernican

significance to Lobachevsky’s ideas.

On the initiative of Alexander Vasiliev, profes-

sor of mathematics, in 1893 Kazan University

LOBACHEVSKY, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

869

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

celebrated the centennial of Lobechevsky’s birth. On

this occasion, Vasiliev presented a lengthy paper

explaining not only the scientific and philosophical

messages of the first non-Euclidean geometry but

also their growing acceptance in the West. At this

time, Kazan University established the Lobachevsky

Prize, to be given annually to a selected mathe-

matician whose work was related to the Lobachevsky

legacy. Among the early recipients of the prize were

Sophus Lie and Henri Poincaré.

In 1926 Kazan University celebrated the cen-

tennial of Lobachevsky’s non-Euclidean geometry.

All speakers placed emphasis on Lobachevsky’s in-

fluence on modern scientific thought. Alexander

Kotelnikov advanced important arguments in fa-

vor of close relations of Lobachevsky’s geometrical

propositions to Einstein’s general theory of relativ-

ity. Lobachevsky also received credit for a major

contribution to modern axiomatics and for prov-

ing that entire sciences could be created by logical

deductions from assumed propositions.

See also: ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kagan, V. N. (1952). N. I. Lobachevsky and His Contribu-

tions to Science. Moscow: Foreign Languages Pub-

lishing House.

Vucinich, Alexander. (1962). “Nikolai Ivanovich

Lobachevskii: The Man Behind the First Non-Euclid-

ean Geometry.” ISIS 53:465–481

A

LEXANDER

V

UCINICH

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

AND ADMINISTRATION

The history of local government in Russia and So-

viet Union can be characterized as a story of grand

plans and the inability to fully implement these

plans. The first serious attempt to establish this

branch of government in Russia came during the

reign of Peter I. Between 1708 and 1719 Peter in-

troduced provincial reforms, in which the country

was divided into fifty guberniiu (provinces). Each of

the provinces was then subdivided into uyezdy (dis-

tricts). Appointed administrators governed the

provinces, while district administrators and coun-

cils assisting provincial administrators were elected

among local gentry. Provincial and district gov-

ernment was to be responsible for local health, ed-

ucation, and economic development. In 1720–1721

Peter introduced his municipal reform. This was

the continuation of the earlier, 1699 effort to

reorganize municipal finances. Municipal adminis-

tration was to be elected from among the towns-

people, and it was to be responsible for day-to-day

running of a town or city.

The results of Peter’s reforms of local and mu-

nicipal government were uneven. The basic subdi-

visions for the country (provinces and districts)

survived the imperial period and were successfully

adopted by Soviet authorities. The substance of the

reforms—the elective principle and local responsi-

bility—fell victim to local apathy and inability to

find suitable officials.

Another attempt to reform local government

in Russia took place during the reign of Catherine

II. Catherine followed the policy of strengthening

of gentry as a class, and under her Charter of No-

bility of 1785, the gentry of each province was

given a status of legal body with wide-ranging le-

gal and property rights. The gentry, together with

the centrally appointed governor, constituted local

government in Russia under Catherine. In the same

year, Catherine II granted a charter to towns, which

provided for limited municipal government, con-

trolled by wealthy merchants.

The truly wide-ranging local and municipal

reforms were instituted during the reign of Alexan-

der II. The 1864 local government reform estab-

lished local (zemstvo) assemblies and boards on

provincial and district levels. Representation in dis-

trict Zemstvos was proportional to land owner-

ship, with allowances for real estate ownership in

towns. Members of district Zemstvos elected,

among themselves, a provincial assembly. Assem-

blies met once per year to discuss basic policy and

budget. They also elected Zemstvo boards, which,

together with professional staff, dealt with every-

day administrative matters. The Zemstvo system

was authorized to deal with education, medical and

veterinary services, insurance, roads, emergency

food supplies, local statistics, and other matters.

Wide-ranging municipal reforms started in the

early 1860s, when several cities were granted, on

a trial basis, the right to draft their own munici-

pal charter and elect a city council. The result of

these experiments was the 1870 Municipal Char-

ter. Under its provision, a town council was elected

by all property owners or taxpayers. The council

elected an administrative board, which ran a town

between the elections.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION

870

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The local government reforms of 1860s and

1870s were wide-ranging and significant. How-

ever, they still left significant inequalities in the

system. Electoral rights were based on property

ownership, and largest property owners—the gen-

try in the rural areas and the wealthy merchants

in the cities—had the greatest representation in the

local government. These inequalities increased un-

der the successors of Alexander II—Alexander III

and Nicholas II—when peasants and the non-Or-

thodox religious minorities were denied rights to

elect and be elected.

The February Revolution of 1917 brought lo-

cal and municipal government reforms of 1860s

and 1870s to their widest possible extent. The lift-

ing of all class-, nationality-, and religion-based re-

strictions on citizens’ participation in government

considerably widened local government electorate.

The temporary municipal administration law of

June 9 formulated accountability, conflicts of in-

terest, and appeal mechanisms. As central govern-

ment weakened between February and October

Revolutions, the role of local government in pro-

viding services and basic security to the citizens in-

creased. At the same time, the soviets, the locally

based umbrella bodies of socialist organizations,

came into existence. The soviets and old local ad-

ministrations coexisted throughout the Russian

Civil War. As Bolsheviks consolidated power, how-

ever, the old local administrations were dissolved,

and local soviets assumed their responsibilities.

Throughout early 1920s the local soviets were

purged of non-Bolshevik representatives and, by

the time of Lenin’s death, they lost their practical

importance as a seat of power in the Soviet Union.

The structure of local soviets was similar to that

of the provincial and district Zemstvos. They con-

sisted of standing and plenary committees, which

discussed matters before them and elected presid-

ium and the chair of the soviet. Local soviets were

tightly intertwined with local Communist Party

structures and representatives of central govern-

ment. This, together with their inability to raise

taxes and tight central control, severely curtailed

their effectiveness in such areas as public housing,

municipal transport, retail trade, health, and wel-

fare. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union,

there was a move away from soviets and toward

Western models of local government. However, the

shape of this branch of government is yet to be de-

cided in the post-Communist Russian Federation.

See also: ASSEMBLY OF THE LAND; GUBERNIYA; SOVIET;

TERRITORIAL-ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS; ZEMSTVO

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kenez, Peter. (1999). A History of the Soviet Union from the

Beginning to the End. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (2000). A History of Russia.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Sakwa, Richard. (1998). Soviet Politics in Perspective, 2nd

ed. London; New York: Routledge.

I

GOR

Y

EYKELIS

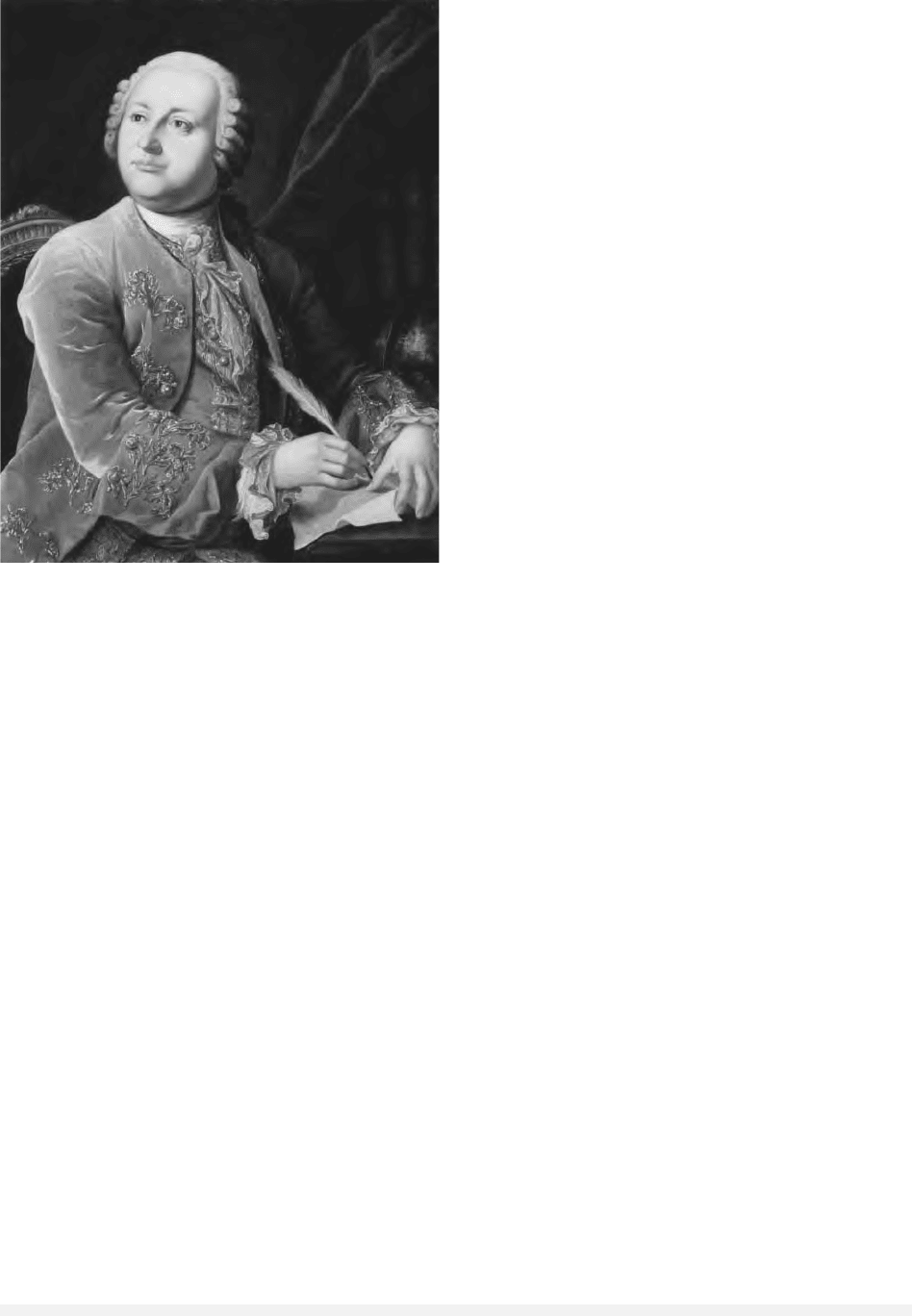

LOMONOSOV, MIKHAIL VASILIEVICH

(1711–1765), chemist, physicist, poet.

Mikhail Lomonosov was born in a small coastal

village near Arkhangelsk. His father was a pros-

perous fisherman and trader. At age nineteen

Lomonosov enrolled in the Slavic-Greek-Latin

Academy in Moscow, a religious institution where

he learned Latin and was exposed to Aristotelian

philosophy and logic. In 1736 he was one of six-

teen students selected to continue their studies at

the newly established secular university at the St.

Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Immediately the

Academy sent him to Marburg University in Ger-

many to study the physical sciences under the

guidance of Christian Wolff, famous for his versa-

tile interest in the links between physics and phi-

losophy. He also spent some time in Freiberg, where

he studied mining techniques. He sent several sci-

entific papers to St. Petersburg. After five years in

Germany, he returned to St. Petersburg and began

immediately to present papers on physical and

chemical themes. In 1745 he was elected full pro-

fessor at the Academy.

Lomonosov drew admiring attention not only

as “the father of Russian science” but also as a ma-

jor modernizer of national poetry. He introduced

the living word as the vehicle of poetic expression.

According to Vissarion Belinsky, who wrote in the

middle of the nineteenth century: “His language is

pure and noble, his style is precise and powerful,

and his verse is full of glitter and soaring spirit.”

According to Evelyn Bristol: “Lomonosov created a

body of verse whose excellence was unprecedented

in his own language.”

Lomonosov’s work in science was of an ency-

clopedic scope; he was actively engaged in physics,

chemistry, astronomy, geology, meteorology, and

navigation. He also contributed to population stud-

ies, political economy, Russian history, rhetoric, and

LOMONOSOV, MIKHAIL VASILIEVICH

871

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

grammar. He brought the most advanced scientific

theories to Russia, commented on their strengths and

weaknesses, and advanced original ideas. He sided

with Newton’s atomistic views on the structure of

matter; questioned the existence of the heat-

generating caloric, a popular crutch of eighteenth-

century science; and endorsed and commented on

Huygens’s clearly manifested inclination toward the

wave theory of light. He raised the question of the

scientific validity of the notion of instantaneous ac-

tion at a distance that was built into Newton’s no-

tion of universal gravitation, conducted experimental

research in atmospheric electricity, made the first

steps toward the formulation of conservation laws,

suggested a historical orientation in the study of the

terrestrial strata, and claimed the presence of at-

mosphere at the planet Venus. In the judgment of

Henry M. Leicester, Lomonosov’s scientific papers re-

vealed “a remarkable originality and . . . ability to

follow his theories to their logical ends, even though

his conclusions were sometimes erroneous.”

In a series of odes, Lomonosov combined his

poetic gifts with his scientific engagement to pro-

duce scientific poetry. These odes dealt with scien-

tific themes and were dedicated to the populariza-

tion of rationalist methods in obtaining socially

valuable knowledge. “A Letter on the Uses of

Glass,” one such ode, relied on rich and poignant

metaphors to portray the invincible power of sci-

entific ideas of the kind advanced by Kepler, Huy-

gens, and Newton. This poem, an ode in praise of

the scientific world outlook, is the first Russian lit-

erary work to hail Copernicus’s heliocentrism.

The appearance of Lomonosov’s papers on

physical and chemical themes in the St. Petersburg

Academy of Sciences journal Novy Kommentary

(New Commentary) during the 1750s marked the be-

ginning of a new epoch in Russia’s cultural his-

tory. They were the first publications of scientific

papers by a native Russian scholar to appear in the

same journal with contributions by established

naturalists and mathematicians of Western origin

and training. The papers, presented in Latin, dealt

with major scientific problems of the day and were

noticed by reviewers in Western scholarly journals.

Few of his Russian contemporaries understood

the intellectual and social significance of Lomonosov’s

achievements in science and of his enthusiastic ad-

vocacy of Baconian views on science as the com-

manding source of social progress. His relations

with the members of the St. Petersburg Academy

and with distinguished members of the literary

community were punctuated by stormy conflicts,

personal and professional. He showed a tendency

to magnify the animosity, overt or latent, of Ger-

man academicians toward Russian personnel and

Russia’s cultural environment. Particularly noted

were his outbursts against G. F. Müller, A. L.

Schlozer, and G. Z. Bayer, the founders of the Nor-

man theory of the origin of the Russian state. On

one occasion, he was sent to jail as a result of com-

plaints by foreign colleagues regarding his abusive

language at scientific sessions of the Academy. In

the face of mounting complaints about his behav-

ior, Catherine II signed a decree in 1763 forcing

Lomonosov to retire; however, before the Senate

could ratify the decree, the empress changed her

mind. Part of Lomonosov’s obstinacy stemmed

from his desire to see increased Russian represen-

tation in the administration of the Academy. In

fairness to Lomonosov, it must be noted that he

had high respect for and maintained cordial rela-

tions with most German members of the Academy.

Lomonosov went through a series of skir-

mishes with theologians who protected the irrevo-

LOMONOSOV, MIKHAIL VASILIEVICH

872

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Portrait of poet and scientist Mikhail Lomonosov from the State

Hermitage Museum collection. © R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION OF THE

S

TATE

H

ERMITAGE

M

USEUM

, S

T

. P

ETERSBURG

, R

USSIA

/CORBIS