Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

of vested interests like the American military-

industrial complex; it has a formal legal status, a

well-developed administrative mechanism, and its

own Web site. The Genshtab and the VPK have far

more power than the American Joint Chiefs of

Staff, the secretary of defense, or the patchwork of

other defense-related organizations.

The OPK consists of seventeen hundred enter-

prises and organizations located in seventy-two re-

gions, officially employing more than 2 million

workers (more nearly 3.5 million), producing 27

percent of the nation’s machinery, and absorbing 25

percent of its imports. Nineteen of these entities are

“city building enterprises,” defense industrial towns

where the OPK is the sole employer. The total num-

ber of OPK enterprises and organizations has been

constant for a decade, but some liberalization has

been achieved in ownership and managerial auton-

omy. At the start of the post-communist epoch, the

VPK was wholly state-owned. As of 2003, 43 per-

cent of its holdings remains government-owned, 29

percent comprises mixed state-private stock compa-

nies, and 29 percent is fully privately owned. All

serve the market in varying degrees, but retain a col-

lective interest in promoting government patronage

and can be quickly commandeered if state procure-

ment orders revive.

Boris Yeltsin’s government tried repeatedly to

reform the VPK, as has Vladimir Putin’s. The most

recent proposal, vetted and signed by Prime Min-

ister Mikhail Kasyanov in October 2001, calls for

civilianizing some twelve hundred enterprises and

institutions, stripping them of their military assets,

including intellectual property, and transferring

this capital to five hundred amalgamated entities

called “system-building integrated structures.” This

rearrangement will increase the military focus of

the OPK by divesting its civilian activities, benefi-

cially reducing structural militarization, but will

strengthen the defense lobby and augment state

ownership. The program calls for the government

to have controlling stock of the lead companies (de-

sign bureaus) of the “system-building integrated

structures.” This will be accomplished by arbitrar-

ily valuing the state’s intellectual property at 100

percent of the lead company’s stock, a tactic that

will terminate the traditional Soviet separation of

design from production and create integrated enti-

ties capable of designing, producing, marketing (ex-

porting), and servicing OPK products. State shares

in non-lead companies will be put in trust with the

design bureaus. The Kremlin intends to use own-

ership as its primary control instrument, keeping

its requisitioning powers in the background, and

minimizing budgetary subsidies at a time when

state weapons-procurement programs are but a

small fraction what they were in the Soviet past.

Ilya Klebanov, former deputy prime minister, and

now minister for industry, science, and technol-

ogy, the architect of the OPK reform program,

hopes in this way to reestablish state administra-

tive governance over domestic military industrial

activities, while creating new entities that can seize

a larger share of the global arms market. It is pre-

mature to judge the outcome of this initiative, but

history suggests that even if the VPK modernizes,

it does not intend to fade away.

See also: KASYANOV, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH; MILITARY-

ECONOMIC PLANNING; MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-

SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Epstein, David. (1990). “The Economic Cost of Soviet Se-

curity and Empire.” In The Impoverished Superpower:

Perestroika and the Soviet Military, ed. Henry Rowen

and Charles Wolf, Jr. San Francisco: Institute for

Contemporary Studies.

Gaddy, Clifford. (1966). The Price of the Past: Russia’s

Struggle with the Legacy of a Militarized Economy.

Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Hill, Christopher. (2003). “Russia’s Defense Spending.”

In Russia’s Uncertain Future. Washington, DC: Joint

Economic Committee.

Izyumov, Alexei; Kosals, Leonid; and Ryvkina, Rosalina.

(2001). “Privatization of the Russian Defense Indus-

try: Ownership and Control Issues.” Post-Communist

Economies 12:485–496.

Rosefielde, Steven. (2004). Progidal Superpower: Russia’s

Re-emerging Future. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Shlykov, Vitaly. (2002). “Russian Defense Industrial

Complex After 9-11.” Paper presented at the con-

ference on “Russian Security Policy and the War on

Terrorism,” U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, Mon-

terey, CA, June 4–5, 2002.

S

TEVEN

R

OSEFIELDE

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE

Although the means have grown more sophisticated,

the basic function of military intelligence (voyennaya

razvedka) has remained unchanged: collecting, ana-

lyzing and disseminating information about the en-

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE

933

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

emy’s intentions and its ability to carry them out.

Since the Soviet era, military intelligence has been

classified according to three categories: strategic, op-

erational, and tactical. Strategic intelligence entails an

understanding of actual and potential foes at the

broadest level, including the organization and capa-

bilities of their armed forces as well as the economy,

population, and geography of the national base. Op-

erational intelligence refers to knowledge of military

value more directly tied to the theater, and is typi-

cally conducted by the staffs of front and army for-

mations, while tactical intelligence is carried out by

commanders at all levels to gather battlefield data di-

rectly relevant to their current mission.

Before the Great Reforms (1860s–1870s), Russ-

ian generals had three basic means of learning

about their foes: spies, prisoners of war, and re-

connaissance. Thus, at the Battle of Kulikovo

(1381) Prince Dmitry Donskoy dispatched a reli-

able diplomat to the enemy’s camp to study the

latter’s intentions, questioned captives, and per-

sonally assessed the terrain, all of which played a

role in his famous victory over the Mongols. While

capable commanders had always understood the

need for good intelligence, until the early eighteenth

century the Russian army had neither systematic

procedures nor personnel designated to carry them

out. Peter I’s introduction of a quartermaster ser-

vice (kvartirmeisterskaya chast) in 1711 (renamed

the general staff, or generalny shtab, by Catherine

II in 1763) laid the institutional groundwork. The

interception of diplomatic correspondence, a vital

element of strategic intelligence, was carried out by

the foreign office’s Cabinet Noir (Black Chamber,

also known as the shifrovalny otdel), beginning

under Empress Elizabeth I (r. 1741–1762). Inter-

ministerial rivalry often hampered effective dis-

semination of such data to the War Ministry.

It would take another century for military in-

telligence properly to be systematized with the cre-

ation of a Main Staff (glavny shtab) by the reformist

War Minister Dmitry Milyutin in 1865. Roughly

analogous to the Prussian Great General Staff, the

Main Staff’s responsibilities included central ad-

ministration, training, and intelligence. Two de-

partments of the Main Staff were responsible for

strategic intelligence: the Military Scientific De-

partment (Voyenny ucheny komitet, which dealt with

European powers) and the Asian Department (Azi-

atskaya chast). Milyutin also regularized proce-

dures for operational and combat intelligence in

1868 with new regulations to establish an intelli-

gence section (razvedivatelnoye otdelenie) attached to

field commanders’ staffs, and he formalized the

training and functions of military attachés (voen-

nye agenty). The Admiralty’s Main Staff established

analogous procedural organizations for naval in-

telligence.

In 1903, the Army’s Military Scientific Depart-

ment was renamed Section Seven of the First Mili-

tary Statistical Department in the Main Staff. Dismal

performance during the Russo-Japanese War in-

evitably led to another series of reforms, which saw

the creation in June 1905 of an independent Main

Directorate of the General Staff (Glavnoye Upravlenie

Generalnago Shtaba, or GUGSh), whose first over

quartermaster general was now tasked with intelli-

gence, among other duties. Resubordinated to the

war minister in 1909, GUGSh would retain its re-

sponsibility for intelligence through World War I.

After the Bolshevik Revolution, Vladimir Lenin

established a Registration Directorate (Registupravle-

nie, RU) in October 1918 to coordinate intelligence

for his nascent Red Army. At the conclusion of the

Civil War, in 1921, the RU was refashioned into

the Second Directorate of the Red Army Staff (also

known as the Intelligence Directorate, Razvedupr,

or RU). A reorganization of the Red Army in 1925

saw the entity transformed into the Red Army

Staff’s Fourth Directorate, and after World War II

it would be the Main Intelligence Directorate

(Glavnoye Razvedivatelnoye Upravlenie, GRU).

Because of the presence of many former Impe-

rial Army officers in the Bolshevik military, the RU

bore more than a passing resemblance to its tsarist

predecessor. However, it would soon branch out

into much more comprehensive collection, espe-

cially through human intelligence (i.e., military

attachés and illegal spies) and intercepting com-

munications. Despite often intense rivalry with the

state security services, beginning with Felix Dz-

erzhinsky’s Cheka, the RU and its successors also

became much more active in rooting out political

threats, whether real or imagined.

Both tsarist and Soviet military intelligence

were respected if not feared by other powers. Like

all military intelligence services, its record was nev-

ertheless marred by some serious blunders, includ-

ing fatally underestimating the capabilities of the

Japanese armed forces in 1904 and miscalculating

the size of German deployments in East Prussia in

1914. Yet even the best intelligence could not com-

pensate for the shortcomings of the supreme com-

mander, most famously when Josef Stalin refused

to heed repeated and often accurate assessments of

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE

934

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Nazi intentions to invade the Soviet Union in June

1941.

See also: ADMINISTRATION, MILITARY; MILITARY, IMPER-

IAL ERA; MILITARY, SPECIAL PURPOSE FORCES; SOVIET

AND POST-SOVIET; STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fuller, William C. (1984). “The Russian Empire.” In

Knowing One’s Enemies: Intelligence Assessment before

the Two World Wars, ed. Ernest R. May. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Garthoff, Raymond L. (1956). “The Soviet Intelligence

Services.” In The Soviet Army, ed. Basil Liddell Hart.

London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Leonard, Raymond W. (1999). Secret Soldiers of the Rev-

olution: Soviet Military Intelligence, 1918–1933. West-

port, CT: Greenwood Press.

Pozniakov, Vladimir. (2000). “The Enemy at the Gates:

Soviet Military Intelligence in the Inter–war Period

and its Forecasts of Future War.” In Russia at the

Age of Wars, ed. Silvio Pons and Romano Giangia-

como. Milan: Fetrinellli.

Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David. (2003). “Re-

forming Russian Military Intelligence.” In Reforming

the Tsar’s Army, ed. David Schimmelpenninck van

der Oye and Bruce Menning. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David. (1996). “Russ-

ian Military Intelligence on the Manchurian Front.”

Intelligence and National Security 11(1):22–31.

D

AVID

S

CHIMMELPENNINCK VAN DER

O

YE

MILITARY REFORMS

Military reform has been one of the central aspects

of Russia’s drive to modernize and become a leading

European military, political, and economic power.

Ivan IV (d. 1584) gave away pomestie lands to cre-

ate a permanent military service class, and Tsar

Alexei Mikhailovich (d. 1676) enserfed Russia’s peas-

ants to guarantee the political support of these mil-

itary servitors. In the same period, Alexei, seeking

to modernize his realm, invited Westerners to Rus-

sia to introduce advanced technical capabilities. But

as the eighteenth century dawned, Russia found it-

self surrounded and outmatched by hostile enemies

to its north, south, west, and, to a lessor extent, to

its east. At the same time, perhaps Russia’s most

energetic tsar, Peter the Great (d. 1725), adopted a

grand strategy based on the goal of conquering ad-

versaries in all directions. Such ambitions required

the complete overhaul of the Russian nation. As a

result, the reforms of Peter the Great represent the

beginning of the modern era of Russian history.

Military reform, designed to create a powerful

permanently standing army and navy, was the

central goal of all of Peter the Great’s monumen-

tal reforms. His most notable military reforms in-

cluded the creation of a navy that he used to great

effect against the Ottomans in the sea of Azov and

the Swedes in the Baltic during the Great Northern

War; the creation of the Guard’s Officer Corps that

became the basis of the standing professional offi-

cer corps until they became superannuated and re-

placed by officers with General Staff training

during the nineteenth century; a twenty-five year

service requirement for peasants selected by lot to

be soldiers; and his codifying military’s existence

by personally writing a set of instructions in 1716

for the army and 1720 for the navy. While these

reforms transformed the operational capabilities of

the Russian military, Peter the Great also sought to

create the social and administrative basis for main-

taining this newly generated power. In 1720 he cre-

ated administrative colleges specifically to furnish

the army and navy with a higher administrative

apparatus to oversee the acquisition of equipment,

supplies, and recruits. Peter’s final seminal reform,

however, was the 1722 creation of the Table of

Ranks, which linked social and political mobility to

the idea of merit, not only in the military but

throughout Russia.

The irony of Peter’s culminating reform was

that the nobility did not accept the Table of Ranks

because it forced them to work to maintain what

they viewed as their inherited birthright to power,

privilege, and status. While no major military re-

forms occurred until after the 1853–1856 Crimean

War, the work of Catherine II’s (d. 1796) “Great

Captains,” Peter Rumyanstev, Grigory Potemkin,

and Alexander Suvorov, combined with the re-

forming efforts of Paul I (d. 1801), created a sys-

tem for educating and training officers and defined

everything from uniforms to operational doctrine.

None of these efforts amounted in scope to the re-

forms that preceded or followed, but together they

provided Russia with a military establishment pow-

erful enough to defeat adversaries ranging from the

powerful French to the declining Ottomans. Realiz-

ing that the army was too large and too wasteful,

Nicholas I (d. 1855) spent the balance of the 1830s

and 1840s introducing administrative reforms to

MILITARY REFORMS

935

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

streamline and enhance performance but, as events

in the Crimea demonstrated, without success.

Alexander II’s (d. 1881) 1861 peasant emanci-

pation launched his Great Reforms and set the stage

for the enlightened War Minister Dmitry Milyutin

to reorganize Russia’s military establishment in

every aspect imaginable. His most enduring reform

was the 1862–1864 establishment of the fifteen

military districts that imposed a centralized and

manageable administrative and command system

over the entire army. Then, to reintroduce the con-

cept of meritocracy into the officer training sys-

tem, he reorganized the Cadet Corps Academies into

Junker schools in 1864 to provide an education to

all qualified candidates regardless of social status.

In addition, in 1868 he oversaw the recasting of

the army’s standing wartime orders. The result of

these three reforms centralized all power within the

army into the war minister’s hands. But Milyutin’s

most important reform was the Universal Con-

scription Act of 1874 that required all Russian men

to serve first in the active army and then in the

reserves. Modeled after the system recently imple-

mented by the Prussians in their stunningly suc-

cessful unification, Russia now had the basis for a

modern conscript army that utilized the Empire’s

superiority in manpower without maintaining a

costly standing army.

Milyutin’s reforms completely overhauled Rus-

sia’s military system. But a difficult victory in the

1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War and the debacle of

the Russo-Japanese War demonstrated that Rus-

sia’s military establishment was in need of further

and immediate reform in the post-1905 period. In

the war’s aftermath, the army and the navy were

overrun with reforming schemes and undertakings

that ranged from the creation of the Supreme De-

fense Council to unify all military policy, to the

emergence of an autonomous General Staff (some-

thing Milyutin intentionally avoided), to the 1906

appointment of a Higher Attestation Commission

charged with the task of purging the officer corps

of dead weight. By 1910, the reaction to military

defeat had calmed down, and War Minister

Vladimir Sukhomlinov sought to address future

concerns with a series of reforms that simplified

the organization of army corps and sought to ra-

tionalize the deployment of troops throughout the

Empire. These reforms demonstrated the future

needs of the army well, resulting in the 1914 pas-

sage of a bill (The Large Program) through the

Duma designed to finance the strengthening of the

entire military establishment.

After the imperial army disintegrated in the

wake of World War I and the 1917 Revolution, and

once the Bolsheviks won the Civil War, the process

of creating the permanent Red Army began with

the 1924–1925 Frunze Reforms. Mikhail Frunze,

largely using the organizational schema of Mi-

lyutin’s military districts, oversaw a series of re-

forms designed to provide the Red Army with a

sufficiently trained cadre to maintain a militia

army. Besides training soldiers as warriors, one of

the central goals of these reforms was to provide

recruits with Communist Party indoctrination,

making military training a vital experience in the

education of Soviet citizens. In the meantime, and

despite the tragic consequences of the purges of the

1930s, Mikhail Tukhachevsky created a military

doctrine that culminated with the Red Army’s vic-

torious deep battle combined operations of World

War II.

See also: FRUNZE, MIKHAIL VASILIEVICH; GREAT REFORMS;

MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA; MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-

SOVIET; MILYUTIN, DMITRY ALEXEYEVICH; PETER I;

TABLE OF RANK; TUKHACHEVSKY, MIKHAIL NIKO-

LAYEVICH

J

OHN

W. S

TEINBERG

MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

The Bolshevik Party, led by Vladimir Lenin and

Leon Trotsky, seized power in November 1917. It

immediately began peace negotiations with the

Central Powers and took control of the armed

forces. Once peace was concluded in March 1918

by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the demobilization

of the old Russian imperial army began.

THE RED ARMY

Adhering to Marxist doctrine, which viewed stand-

ing armies as tools of state and class oppression, the

Bolsheviks did not plan to replace the imperial army

and intended instead to rely on a citizens’ militia of

class-conscious workers for defense. The emergence

of widespread opposition to the Bolshevik seizure of

power convinced Lenin of the need for a regular

army after all, and he ordered Trotsky to create a

Red Army, the birthday of which was recognized

as February 23, 1918. As the number of workers

willing to serve on a voluntary basis proved to be

insufficient for the needs of the time, conscription

of workers and peasants was soon introduced. By

1921 the Red Army had swelled to nearly five mil-

MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

936

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

937

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

lion men and women; the majority, however, were

engaged full-time in food requisitioning and other

economic activities designed to keep the army fed

and equipped as Russia’s beleaguered economy be-

gan to collapse. Because they lacked trained leader-

ship to fight the civil war that erupted in the spring

of 1918, the Bolsheviks recruited and impressed for-

mer officers of the old army and assigned political

commissars to validate their orders and maintain

political reliability of the units.

The civil war raged until 1922, when the last

elements of anticommunist resistance were wiped

out in Siberia. In the meantime Poland attacked So-

viet Russia in April 1920 in a bid to establish its

borders deep in western Ukraine. The Soviet coun-

teroffensive took the Red Army to the gates of War-

saw before it was repelled and pushed back into

Ukraine in August. The Red Army forces combat-

ing the Poles virtually disintegrated during their re-

treat, and the Cossacks of the elite First Cavalry

Army, led by Josef Stalin’s cronies Kliment

Voroshilov and Semen Budenny, staged a bloody

anti-Bolshevik mutiny and pogrom in the process.

The subsequent peace treaty gave Poland very fa-

vorable boundaries eastward into Ukraine.

The onset of peace saw the demobilization of

the regular armed forces to a mere half million

men. Some party officials wanted to abolish the

army totally and replace it with a citizens’ militia.

As a compromise, a mixed system consisting of a

small standing army and a large territorial militia

was established. Regular soldiers would serve for

two years, but territorial soldiers would serve for

five, one weekend per month and several weeks in

the summer. Until it was absorbed into the regu-

lar army beginning in 1936, the territorial army

outnumbered the regular army by about three to

one. For the rest of the decade the armed forces

were underfunded, undersupplied, and ill-equipped

with old, outdated weaponry.

During the 1920s most former tsarist officers

were dismissed and a new cadre of Soviet officers

began to form. Party membership was strongly en-

couraged among the officers, and throughout the

Soviet period at least eighty percent of the officers

were party members. At and above the rank of

colonel virtually all officers held party membership.

A unique feature of the Soviet armed forces was

the imposition on it of the Political Administration

of the Red Army (PURKKA, later renamed GlavPUR).

This was the Communist Party organization for

which the military commissars worked. Initially

every commander from battalion level on up to the

Army High Command had a commissar as a part-

ner. After the civil war, commanders no longer had

to have their orders countersigned by the commis-

sar to be valid, and commissars’ duties were rele-

gated to discipline, morale, and political education.

During the 1930s political officers were added

at the company and platoon levels, and during

the purges and at the outset of World War II com-

manders once again had to have commissars

countersign their orders. Commissars shared re-

sponsibility for the success of the unit and were

praised or punished alongside the commanders, but

they answered to the political authorities, not to

the military chain of command. Commissars were

required to evaluate officers’ political reliability on

their annual attestations and during promotion

proceedings, thus giving them some leverage over

the officers with whom they served.

THE 1930S

The First Five-Year Plan, from 1928 to1932, ex-

panded the USSR’s industrial base, which then be-

gan producing modern equipment, including tanks,

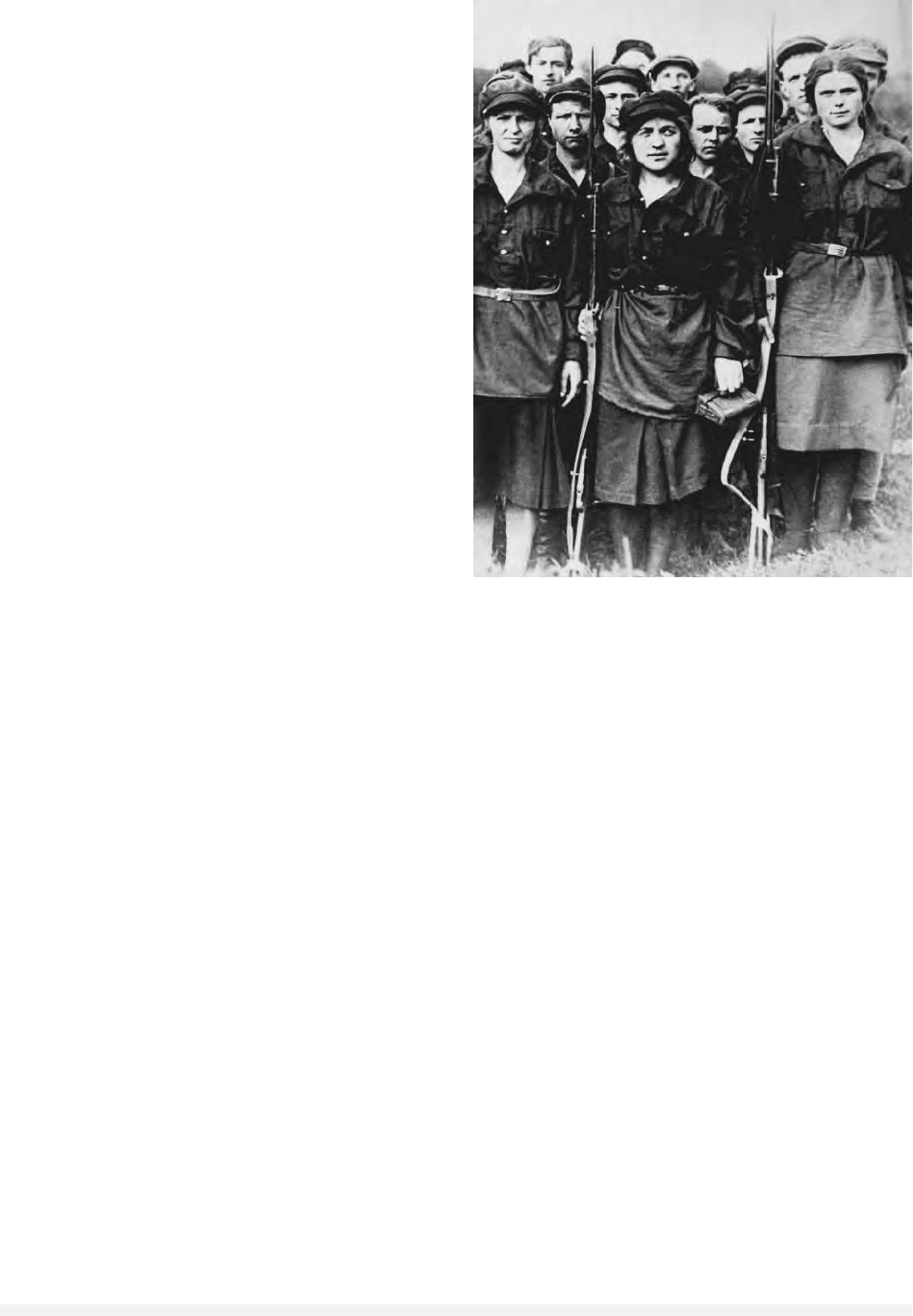

A group of young women Russian soldiers train for military

service following the Bolshevik revolution. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

fighter aircraft and bombers, and new warships. The

size of the armed forces rapidly increased to about

1.5 million between 1932 and 1937. The rapid ex-

pansion of the armed forces led to insurmountable

difficulties in recruiting officers. As a stopgap mea-

sure, party members were required to serve as offi-

cers for two- or three-year stints, and privates and

sergeants were promoted to officer rank. The train-

ing of officer candidates in military schools was ab-

breviated from four years to two or less to get more

officers into newly created units. As a result the

competence and cohesion of the leadership suffered.

In the 1930s Soviet strategists such as Vladimir

K. Triandifilov and Mikhail Tukhachevsky devised

innovative tactics for utilizing tanks and aircraft in

offensive operations. The Soviets created the first

large tank units, and experimented with paratroops

and airborne tactics. During the Spanish Civil War

(1936–39) Soviet officers and men advised the Re-

publican forces and engaged in armored and air

combat testing the USSR’s latest tanks and aircraft

against the fascists.

The terror purge of the officer corps instituted

by Josef Stalin in 1937–1939 took a heavy toll of

the top leadership. Stalin’s motives for the purge

will never be known for certain, but most plausi-

bly he was concerned about a possible military

coup. Although it is very unlikely that the mili-

tary planned or hoped to seize power, three of its

five marshals were executed, as were fifteen of six-

teen army commanders of the first and second

rank, sixty of sixty-seven corps commanders, and

136 of 199 division commanders. Forty-two of the

top forty-six military commissars also were ar-

rested and executed. When the process of denunci-

ation, arrest, investigation, and rehabilitation had

run its course in 1940, about 23,000 military and

political officers had either been executed or were

in prison camps. It was long believed that perhaps

as many as fifty percent of the officer corps was

purged, but archival evidence subsequently indi-

cated that when the reinstatements of thousands

of arrested officers during World War II are taken

into account, fewer than ten percent of the officer

corps was permanently purged, which does not di-

minish the loss of talented men. Simultaneous with

the purge was the rapid expansion of the armed

forces in response to the growth of militarism in

Germany and Japan. By June 1941 the Soviet

armed forces had grown to 4.5 million men, but

were terribly short of officers because of difficul-

ties in recruiting and the time needed for training.

Tens of thousands of civilian party members,

sergeants, and enlisted men were forced to serve as

officers with little training for their responsibilities.

Despite the USSR’s rapid industrialization, the

army found itself underequipped because men were

being conscripted faster than weapons, equipment,

and even boots and uniforms could be made for

them.

The end of the decade saw the Soviet Union in-

volved in several armed conflicts. From May to Sep-

tember 1939, Soviet forces under General Georgy

Zhukov battled the Japanese Kwantung Army and

drove it out of Mongolia. In September 1939 the

Soviet army and air force invaded eastern Poland

after the German army had nearly finished con-

quering the western half. In November 1939 the

Soviet armed forces attacked Finland but failed to

conquer it and in the process suffered nearly

400,000 casualties. Stalin’s government was forced

to accept a negotiated peace in March 1940 in

which it gained some territory north of Leningrad

and naval bases in the Gulf of Finland. Anticipat-

ing war with Nazi Germany, the USSR increased

the pace of rearmament in the years 1939–1941,

and prodigious numbers of modern tanks, artillery,

and aircraft were delivered to the armed forces.

WORLD WAR II

In violation of the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact

signed in 1939, Germany invaded the USSR on June

22, 1941. Much of the forward-based Soviet air

force was destroyed on the ground on the first day

of the onslaught. All along the front the Axis forces

rolled up the Soviet defenses, hoping to destroy the

entire Red Army in the western regions before

marching on Moscow and Leningrad. By Decem-

ber 1941 the Germans had put Leningrad under

siege, came within sight of Moscow, and, in great

battles of encirclement, had inflicted about 4.5 mil-

lion casualties on the Soviet armed forces, yet they

had been unable to destroy the army and the coun-

try’s will and ability to resist. Nearly 5.3 million

Soviet citizens were mobilized for the armed forces

in the first eight days of the war. They were used

to create new formations or to fill existing units,

which were reconstituted and rearmed and sent

back into the fray. To rally the USSR, Stalin de-

clared the struggle to be the Great Patriotic War of

the Soviet Union, comparable to the war against

Napoleon 130 years earlier.

At the outset of the war, Stalin appointed him-

self supreme commander and dominated Soviet

military operations, ignoring the advice of his gen-

erals. Stalin’s disastrous decisions culminated in

MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

938

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

939

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet tank regiment passes the Kremlin during the 1988 parade marking the anniversary of the October Revolution.

© N

OVOSTI

/S

OVFOTO

the debacle at Kiev in September 1941, in which

600,000 Soviet troops were lost because he refused

to allow them to retreat. As a result, Stalin pro-

moted Marshal Georgy Zhukov to second in com-

mand and from then on usually heeded the advice

of his military commanders.

The Soviet Army once again lost ground dur-

ing the summer of 1942, when a new German

offensive completed the conquest of Ukraine and

reached the Volga River at Stalingrad. In the fall of

1942 the Soviet Army began a counteroffensive,

and by the end of February 1943 it had eliminated

the German forces in Stalingrad and pushed the

front several hundred miles back from the Volga.

July 1943 saw the largest tank battle in history at

Kursk, ending in a decisive German defeat. From

then on the initiative passed to the Soviet side. The

major campaign of 1944 was Operation Bagration,

which liberated Belarus and carried the Red Army

to the gates of Warsaw by July, in the process de-

stroying German Army Group Center, a Soviet goal

since January 1942. The final assault on Berlin be-

gan in April 1945 and culminated on May 3. The

war in Europe ended that month, but a short cam-

paign in China against Japan followed, beginning

in August and ending in September 1945 with the

Japanese surrender to the Allies.

THE COLD WAR

After the war, the armed forces demobilized to their

prewar strength of about four million and were as-

signed to the occupation of Eastern Europe. Con-

scription remained in force. During the late 1950s,

under Nikita Khrushchev, who stressed nuclear

rather than conventional military power, the army’s

strength was cut to around three million. Leonid

Brezhnev restored the size of the armed force to

more than four million. During the Cold War, pride

of place in the Soviet military shifted to the newly

created Strategic Rocket Forces (SRF), which con-

trolled the ground-based nuclear missile forces. In

addition to the SRF, the air force had bomber-

delivered nuclear weapons and the navy had

missile-equipped submarines. The army, with the

exception of the airborne forces, became an almost

exclusively motorized and mechanized force.

The Soviet army’s last war was fought in

Afghanistan from December 1979 to February

1989. Brought in to save the fledgling Afghan com-

munist government, which had provoked a civil

war through its use of coercion and class conflict

to create a socialist state, the Soviet army expected

to defeat the rebels in a short campaign and then

withdraw. Instead, the conflict degenerated into a

guerilla war against disparate Afghan tribes that

had declared a holy war, or jihad, against the So-

viet army, which was unable to bring its strength

in armor, artillery, or nuclear weapons to bear. The

Afghan rebels, or mujahideen, with safe havens in

neighboring Iran and Pakistan, received arms and

ammunition from the United States, enabling them

to prolong the struggle indefinitely. The Soviet high

command capped the commitment of troops to the

war at 150,000, for the most part treating it as a

sideshow while keeping its main focus on a possi-

ble war with NATO. The conflict was finally

brought to a negotiated end after the ascension of

Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985, with nearly 15,000

men killed in vain.

Gorbachev’s policy of rapprochement with the

West had a major impact on the Soviet armed

forces. Between 1989 and 1991 their numbers were

slashed by one million, with more cuts projected

for the coming years. The defense budget was cut,

the army and air force were withdrawn from East-

ern Europe, naval ship building virtually ceased,

and the number of nuclear missiles and warheads

was reduced—all over the objections of the military

high command. Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, or

openness, exposed the horrible conditions of service

for soldiers, particularly the extent and severity of

hazing, which contributed to a dramatic increase

in desertions and avoidance of conscription. The

prestige of the military dropped precipitously, lead-

ing to serious morale problems in the officer corps.

Motivated in part by a desire to restore the power,

prestige, and influence of the military in politics

and society, the minister of defense, Dmitry Iazov,

aided and abetted the coup against Gorbachev in

August 1991. The coup failed when the comman-

ders of the armored and airborne divisions ordered

into Moscow refused to support it.

THE POST-SOVIET ARMY

The formal dissolution of the USSR in December

1991 led to the dismemberment of the Soviet armed

forces and the creation of numerous national armies

and navies. Conventional weapons, aircraft, and sur-

face ships were shared out among the new nations,

but the Russian Federation took all of the nuclear

weapons. The army of the Russian Federation sees

itself as heir to the traditions and heritage of the

tsarist and Soviet armies. Although there are advo-

cates of a professional force, the Russian army re-

mains dependent on conscription to fill its ranks.

Thousands of officers resigned from the armed forces

MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

940

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and thousands of non-Russians transferred their loy-

alty and services to the emerging armies of the newly

independent states. The political administration was

promptly abolished after the coup. During the 1990s,

the new Russian army fought two small, bloody,

and inconclusive wars in Chechnya, a former Soviet

republic that sought independence from Moscow.

See also: ADMINISTRATION, MILITARY; AFGHANISTAN, RE-

LATIONS WITH; CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; COLD WAR;

MILITARY DOCTRINE; MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COM-

PLEX; OPERATION BARBAROSSA; PURGES, THE GREAT;

SOVIET-FINNISH WAR; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexiev, Alexander. (1988). Inside the Soviet Army in

Afghanistan. Santa Monica, CA: Rand.

Erickson, John. (1975). The Road to Stalingrad: Stalin’s

War with Germany. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Erickson, John. (1983). The Road to Berlin: Continuing the

History of Stalin’s War With Germany. Boulder, CO:

Westview Press.

Erickson, John. (2001). The Soviet High Command: A Mil-

itary-Political History, 1918–1941, 3rd ed. London:

Frank Cass.

Jones, Ellen. (1975). Red Army and Society: A Sociology of

the Soviet Military. Boston: Allen & Unwin.

Reese, Roger R. (2000). The Soviet Military Experience: A

History of the Soviet Army, 1917–1991. London: Rout-

ledge.

Scott, Harriet F., and Scott, William F. (1981). The Armed

Forces of the USSR, 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview

Press.

Von Hagen, Mark.(1990). Soldier in the Proletarian Dic-

tatorship: The Red Army and the Soviet Socialist State,

1917–1930. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

White, D. Fedotoff. (1944). The Growth of the Red Army.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

R

OGER

R. R

EESE

MILYUKOV, PAUL NIKOLAYEVICH

(1859–1943), Russian historian and publicist; Rus-

sian liberal leader.

Milyukov was born in Moscow. He studied at

the First Gymnasium of Moscow and the depart-

ment of history and philology at Moscow Uni-

versity (1877-1882). His tutors were Vassily

Kliuchevsky and Paul Vinogradov. After graduat-

ing from the university, Milyukov remained in the

department of Russian history in order to prepare

to become a professor. From 1886 to 1895, he held

the position of assistant professor in the depart-

ment of Russian history at Moscow University. In

1892 he defended his master’s thesis based on the

book State Economy and the Reform of Peter the Great

(St. Petersburg, 1892). In the area of historical

methodology Milyukov shared the views of posi-

tivists. The most important of Milyukov’s historical

works was Essays on the History of Russian Culture

(St. Petersburg, 1896-1903). Milyukov suggested

that Russia is following the same path as Western

Europe, but its development is characterized by slow-

ness. In contrast to the West, Russia’s social and eco-

nomic development was generally initiated by the

government, going from the top down. Milyukov

is the author of o ne of the first courses of Russian

historiography: Main Currents in Russian Historical

Thought (Moscow, 1897). In 1895, he was fired

from the Moscow University for his public lectures

on the social movement in Russia and sent to Ri-

azan, and then for two years (1897–1899) abroad.

In 1900 he was arrested for attending the meet-

ing honoring the late revolutionary Petr Lavrov in

St. Petersburg. He was sentenced to six months of

incarceration, but was released early at the petition

of Kliuchevsky before emperor Nicholas II. In 1902,

Milyukov published a program article “From Rus-

sian Constitutionalists in the Osvobozhdenie” (“Lib-

eration”), magazine of Russian liberals, issued

abroad. Between 1902 and 1905, Milyukov spent

a large amount of time abroad, traveling, and lec-

turing in the United States at the invitation of

Charles Crane. Milyukov’s lectures were published

as Russia and Its Crisis (Chicago, 1905).

In 1905 Milyukov returned to Russia and took

part in the liberation movement as one of the or-

ganizers and chairman of the Union of Unions. On

August, 1905, he was arrested, but after a month-

long incarceration was released without having

been charged. In October of 1905 Milyukov became

one of the organizers of the Constitutional Demo-

cratic (Kadet) Party. His reaction towards the Octo-

ber Manifesto was skeptical and he believed it

necessary to continue to battle the government. Due

to formal issues, he could not run for a place in the

First and Second Dumas, but he was basically the

head of the Kadet Faction. From 1906, Milyukov

was the editor of the Rech (Speech) newspaper, the

central organ of the Cadet Party. From 1907, he

was the chairman of the Party’s central committee.

From 1907 to 1912, he was a member of the third

Duma, elected in St. Petersburg. He favored the tac-

MILYUKOV, PAUL NIKOLAYEVICH

941

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tics of “the preservation of the Duma,” fearing its

dissolution by the tsar. He became a renowned ex-

pert in the matters of foreign policy. In the Duma,

he gave seventy-three speeches, which total ap-

proximately seven hundred large pages. In 1912

Milyukov was reelected to the Duma, once again

from St. Petersburg.

After the beginning of World War I, Milyukov

assumed a patriotic position and put forth the

motto of a “holy union” with the government for

the period of the war. He believed it necessary for

Russia to acquire, as a result of the war, Bosporus

and the Dardanelles. In August of 1915, Milyukov,

was one of the organizers and leaders of the oppo-

sitionist interparty Progressive Bloc, created with

the aim of pressuring the government in the inter-

ests of a more effective war strategy. On Novem-

ber 1, 1916, Milyukov made a speech in the Duma

that contained direct accusations of the royal fam-

ily members of treason and harshly criticized the

government. Every part of Milyukov’s speech ended

with “What Is This: Stupidity or Treason?” The

speech was denied publication, but became popular

through many private copies and later received the

name of “The Attacking Sign.”

After the February revolution Milyukov served

as the foreign minister in the Provisional Govern-

ment. Milyukov’s note of April, 1917, declaring

support for fulfilling obligations to the allies pro-

voked antigovernmental demonstrations and caused

him to retire. Milyukov attacked the Bolsheviks, de-

manding Lenin’s arrest, and criticized the Provi-

sional Government for its inability to restore order.

After the October Revolution, Milyukov left for the

Don, and wrote, at the request of general Mikhail

Alexeyev, the Declaration of the Volunteer Army.

In the summer of 1918, while in Kiev, he tried to

contact German command, hoping to receive aid in

the struggle against Bolshevism. Milyukov’s “Ger-

man orientation,” unsupported by a majority of the

Cadet Party, led to the downfall of his authority

and caused him to retire as chairman of the party.

In November of 1918, Milyukov went abroad, liv-

ing in London, where he participated in the Russian

Liberation Committee. From 1920, he lived in Paris.

After the defeat of White armies, he proposed a set

of “new tactics,” the point of which was to defeat

Bolshevism from within. Milyukov’s “new tactics”

received no support among most emigré Cadets and

in 1921 he formed the Paris Democratic Group of

the Party, which caused a split within the Cadets.

In 1924 the group was modified into a Republican-

Democrat Union. From 1921 to 1940 Milyukov

edited the most popular emigré newspaper The Lat-

est News (Poslednie Novosti). He became one of the

first historians of the revolution and the civil war,

publishing History of the Second Russian Revolution

(Sofia, 1921-1923), and Russia at the Turning-point

(in two volumes, Paris, 1927).

In 1940, escaping the Nazi invasion, Milyukov

fled to the south of France, where he worked on his

memoirs, published posthumously. He welcomed

the victories of the Soviet army and accepted the ac-

complishments of the Stalinist regime in fortifying

Russian Statehood in his article “The Truth of Bol-

shevism” (1942). Milyukov died in Aix-les-Bains on

March 31, 1943.

See also: CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; FEBRU-

ARY REVOLUTION HISTORIOGRAPHY; LIBERALISM; OC-

TOBER REVOLUTION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Emmons, Terence. (1999). “On the Problem of Russia’s

‘Separate Path’ in Late Imperial Historiography.” In

Historiography of Imperial Russia, ed Tomas Sanders.

Armonk, NY: M. E.Sharpe.

Miliukov, Pavel Nikolaevich. (1942). Outlines of Russian

Culture. 3 vols., ed. Michael Karpovich; tr. Valentine

Ughet and Eleanor Davis. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press.

Miliukov, Pavel Nikolaevich. (1967). Political memoirs,

1905–1917, ed. Arthur P. Mendel, tr. Carl Goldberg.

Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Miliukov, Pavel Nikolaevich. (1978–1987). The Russian

Revolution. 3 vols., ed. Richard Stites; tr. Tatyana and

Richard Stites. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic Interna-

tional Press.

Miliukov, Pavel Nikolaevich; Seignobos, Charles; and

Eisenmann, L. (1968). History of Russia. New York:

Funk & Wagnalls.

Riha, Thomas. (1969). A Russian European: Paul Miliukov

in Russian Politics. Notre Dame, IN: University of

Notre Dame Press.

Stockdale, Melissa K. (1996). Paul Miliukov and the Quest

for a Liberal Russia, 1880-1918. Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University Press.

O

LEG

B

UDNITSKII

MILYUTIN, DMITRY ALEXEYEVICH

(1816–1912), count (1878), political and military

figure, military historian, and Imperial Russian war

minister (1861–1881).

MILYUTIN, DMITRY ALEXEYEVICH

942

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY