Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

to escape Marx’s “idiocy of rural life,” but to “sat-

isfise” their lives (in H. Simon’s concept), that is,

to achieve and maintain a satisfactory standard of

living.

See also: MIR; PEASANT ECONOMY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bartlett, R., ed. (1990). Land Commune and Peasant Com-

munity in Russia. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Mironov, Boris, and Eklof, Ben. (2000). A Social History

of Imperial Russia, 1700–1917. Boulder, CO: West-

view.

S

TEVEN

A. G

RANT

OCCULTISM

Occult books of fortune-telling, dreams, spells, as-

trology, and speculative mysticism entered me-

dieval Russia as translations of Greek, Byzantine,

European, Arabic, and Persian “secret books.” Their

prohibition by the Council of a Hundred Chapters

(Stoglav) in 1551 enhanced rather than diminished

their popularity, and many have circulated into our

own day.

The Age of Reason did not extirpate Russia’s

occult interests. During the eighteenth century

more than 100 occult books were printed, mostly

translations of European alchemical, mystical, Ma-

sonic, Rosicrucian, and oriental wisdom texts.

Many were published by the author and Freema-

son Nikolai Novikov.

As the nineteenth century began, Tsar Alexan-

der I encouraged Swedenborgians, Freemasons,

mystical sectarians, and the questionable “Bible So-

ciety,” before suddenly banning occult books and

secret societies in 1822. The autocracy and the

church countered the occultism and supernatural-

ism of German Romanticism with an increasingly

restrictive system of church censorship, viewing

the occult as “spiritual sedition.”

Nevertheless, Spiritualism managed to pene-

trate Russia in the late 1850s, introduced by Count

Grigory Kushelev-Bezborodko, a friend of Daniel

Dunglas Home (1833–1886), the famous medium

who gave seances for the court of Alexander II.

Their coterie included the writers and philosophers

Alexei Tolstoy, Vladimir Soloviev, Vladimir Dal,

Alexander Aksakov, and faculty from Moscow and

St. Petersburg Universities.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Russia,

like Europe, experienced the French “Occult Re-

vival,” a reaction against prevailing scientific pos-

itivism. Spiritualism, theosophy, hermeticism,

mystery cults, and Freemasonry attracted the in-

terest of upper- and middle-class Russian society

and configured decadence and symbolism in the

arts.

Theosophy, founded in New York in 1875

by Russian expatriate Elena Blavatsky (1831–1891),

was a pseudo-religious, neo-Buddhist movement

that claimed to be a “synthesis of Science, Religion,

and Philosophy.” It appealed to the god-seeking

Russian intelligentsia (including, at various times,

Vladimir Soloviev, Max Voloshin, Konstantin Bal-

mont, Alexander Skryabin, Maxim Gorky). A Chris-

tianized, Western form of theosophy, Rudolf

Steiner’s anthroposophy, attracted the intellectuals

Andrey Bely, Nikolai Berdyayev, and Vyacheslav

Ivanov.

Russian Freemasonry revived at the end of the

nineteenth century. Masons, Martinists, and Rosi-

crucians preceded the mystical sectarian Grigory

Rasputin (1872–1916) as “friends” to the court of

Tsar Nicholas II. After the Revolution of 1905–1906,

Russian Freemasonry became increasingly politi-

cized, eventually playing a role in the events of

1916-1917.

The least documented of Russia’s occult move-

ments was the elitist hermeticism (loosely includ-

ing philosophical alchemy, gnosticism, kabbalism,

mystical Freemasonry, and magic), heir of the Oc-

cult Revival. Finally, sensational (or “boulevard”)

mysticism was popular among all classes: magic,

astrology, Tarot, fortune-telling, dream interpreta-

tion, chiromancy, phrenology, witchcraft, hypno-

tism.

More than forty occult journals and papers and

eight hundred books on occultism appeared in Rus-

sia between 1881 and 1922, most of them after the

censorship-easing Manifesto of October 17, 1905.

After the Bolshevik coup, occult societies were pro-

scribed. All were closed by official decree in 1922;

in the 1930s those members who had not emi-

grated or ceased activity were arrested.

In the Soviet Union, occultists and ekstra-sensy

existed underground (and occasionally within in

the Kremlin walls). The post-1991 period saw the

return of theosophy and anthroposophy, shaman-

OCCULTISM

1083

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ism, Buddhism, Hare Krishnas, Roerich cults, neo-

paganism, the White Brotherhood, UFOlogy, and

other occult trends.

See also: FREEMASONRY; PAGANSIM; RELIGION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carlson, Maria. (1993). “No Religion Higher Than Truth”:

A History of the Theosophical Movement in Russia,

1875–1922. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Rosenthal, Bernice Glatzer, ed. (1997). The Occult in Rus-

sian and Soviet Culture. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univer-

sity Press.

M

ARIA

C

ARLSON

OCTOBER 1993 EVENTS

During the October 1993 events, Boris Yeltsin’s

forcible dissolution of parliament took Russia to the

edge of civil war. Seen as decisive and essential by

his supporters, the dissolution was a radically di-

visive action, the consequences of which continued

to reverberate through Russian society in the early

twenty-first century.

In 1992 and 1993 a deep divide developed be-

tween the executive and legislative branches of gov-

ernment. The root cause of this was President

Yeltsin’s decision to adopt a radical economic re-

form strategy, urged on him by the West, for

which he and his government were not able to gen-

erate sustained parliamentary support. Faced with

resistance from the legislators, Yeltsin made only

minimal concessions and on most issues chose to

confront them. This subjected Russia’s new politi-

cal and judicial institutions to strains that they

could not adequately handle. In addition, the con-

frontation became highly personalized, with the

principal figures forcefully manipulating institu-

tions to benefit themselves and their causes.

Apart from Yeltsin, key individuals on the ex-

ecutive side of the confrontation were Yegor Gaidar

and Anatoly Chubais. They were the ministers

most responsible for launching and implementing

the radical economic reforms known as shock ther-

apy. Leading the majority in parliament was its

speaker Ruslan Khasbulatov, a former ally of

Yeltsin and an inexperienced and manipulative

politician of high ambition. Over time, he was in-

creasingly joined by Yeltsin’s similarly ambitious

and inexperienced vice-president, former air force

general Alexander Rutskoi.

On March 20, 1993, Yeltsin made a first at-

tempt to rid himself of parliament’s opposition. De-

claring the imposition of emergency rule, he said

that henceforth no decisions of the legislature that

negated decrees from the executive branch would

have juridical force. However, the Constitutional

Court ruled his action unconstitutional, some of

his ministers declined to back him, and the parlia-

ment came close to impeaching him. Yeltsin backed

off.

At this time, Khasbulatov and the Constitu-

tional Court’s chairman, Valery Zorkin, separately

sought to engage Yeltsin in a compromise resolu-

tion of the “dual power” conflict. The proposed ba-

sis was the so-called zero option. The centerpiece

of this approach was simultaneous early elections

to both the presidency and the parliament. How-

ever, Yeltsin had no desire to share power sub-

stantively, even with a newly elected parliament.

In taking this stance, he sought and obtained

the support of Western governments by repeatedly

inflating the negligible threat of a communist re-

vanche. He also got some qualified backing from

the Russian public, when an April 1993 referen-

dum showed that a small majority of the popula-

tion trusted him, and an even smaller majority

approved of his socioeconomic policies.

On September 21, Yeltsin announced that to re-

solve the grave political crisis he had signed decree

1400, which annulled the powers of the legislature.

Elections would be held on December 12 for a

parliament of a new type. And the same day a ref-

erendum would be held on a completely new con-

stitution.

In response, the Supreme Soviet immediately

voted to impeach Yeltsin and, in accordance with

the constitution, to install Vice President Alexan-

der Rutskoi as acting president. Rutskoi proceeded

to annul decree 1400 (whereupon Yeltsin annulled

Rutskoi’s decree) and precipitously appointed senior

ministers of nationalist and communist views to

his own government, thus alienating many cen-

trists. On September 23, with pro-government

deputies boycotting the proceedings, the congress

confirmed Yeltsin’s impeachment by a vote of 636

to 2.

The next ten days were occupied by a war of

words between the rival governments, as they

OCTOBER 1993 EVENTS

1084

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Pro-Yeltsin soldiers watch the Soviet parliament building as it burns. © P

ETER

T

URNLEY

/CORBIS

sought to build support around Russia, and by of-

ficial acts of harassment, like switching off the elec-

tricity in the parliament’s building, known as “the

White House.” Although most Russians remained

passive, adopting the attitude “a plague on both

your houses,” small groups demonstrated for one

or the other camp, or sent messages. According to

Yeltsin’s government, 70 percent of the regional

soviets supported the parliament. From five loca-

tions around Moscow, Kremlin representatives so-

licited visits from wavering deputies and offered

them—if they would change sides—good jobs, cash

payments equal to nearly $1,000, and immunity

from future prosecution.

On September 27, Yeltsin explicitly rejected the

zero option. Three days later the Orthodox patriarch

suggested that the church should mediate. The two

sides agreed and began talks the next day. However,

on October 3, events moved rapidly to their de-

nouement. The exact sequence of events remains

murky. A march organized by purported support-

ers of parliament was mysteriously allowed through

a cordon around the White House. Then, apparently,

hidden Kremlin snipers fired on it. Then Rutskoi, in-

stead of calling on the crowd to defend the White

House, urged it to storm the city hall, the Kremlin,

and the Ostankino television center. Thereafter, acts

of violence on both sides, and an unexplained episode

of the Kremlin not at first defending Ostankino,

ensured that events got out of control and many

people were killed. Throughout, the Yeltsin team ap-

peared to use cunning methods to create a situation

in which it would appear that parliament’s side, not

its own, had used violence first.

That night, the Kremlin team, not wanting to

order the army in writing to open fire, had great

difficulty persuading key military leaders to go take

action. However, the next day a light tank bom-

bardment of the White House softened up the by

now depleted body of parliamentarians, who soon

surrendered. Twenty-seven leaders were arrested,

only to be amnestied four months later. According

to the Kremlin, a total of 143 people were killed dur-

ing the confrontation. However, an impartial in-

vestigation by the human rights group Memorial

gave an estimate of several hundred.

1085

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

OCTOBER 1993 EVENTS

Over the next three months Yeltsin exercised

virtually dictatorial powers. He shut down the

Constitutional Court; abolished the entire structure

of regional, city, and district legislatures; and

banned certain nationalist and communist parties

and publications. With minimal public debate, he

pushed through a new constitution that was offi-

cially approved by referendum on December 12, al-

though widespread charges of falsified results were

not answered and the relevant evidence was de-

stroyed. He also broke the promise he gave in Sep-

tember to hold a new presidential election in June

1994, and postponed the event by two years.

Although in September 1993 most of the par-

liament’s leaders were no less unpopular than

Yeltsin and his government, and although Russia

would probably have been ruled no better—more

likely worse—if they had won, Yeltsin’s resort in

October to violence instead of compromise seriously

undermined Russia’s infant democracy and the le-

gitimacy of his government.

See also: CHUBAIS, ANATOLY BORISOVICH; GAIDAR, YEGOR

TIMUROVICH; MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET;

RUTSKOI, ALEXANDER VLADIMIROVICH; YELTSIN, BORIS

NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism Against Democ-

racy. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

Shevtsova, Lilia. (1999). Yeltsin’s Russia: Myths and Re-

alities. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace.

P

ETER

R

EDDAWAY

OCTOBER GENERAL STRIKE OF 1905

The general strike of October was the culminating

event of the 1905 Revolution and the most inclu-

sive and consequential of several general strikes

that took place in 1905, resulting in the an-

nouncement of the Manifesto of October 17. It was

initiated first and foremost by workers in larger in-

dustrial enterprises, many of whom nursed unsat-

isfied demands from strikes earlier in the year.

Although the ripeness of workers to strike in many

diverse working situations across the empire was

paramount, the call of the All–Russian Union of

Railroad Workers for a national rail strike on Oc-

tober 4 provided a timely impetus. The railroaders’

strike gave them control of Russia’s means of com-

munication, allowing them to spread word of the

strike throughout the empire, while their immobi-

lization of rail traffic forcibly idled many trades and

industries.

Although workers and the urban public gen-

erally found themselves at different stages of or-

ganizational and political development in October,

a unique synergy arose that stirred them all to

greater effort. The spread of the strikes from the

generally more unified and mobilized factory

workers to artisans, small businesses, and

white–collar workers of the city centers lent the

October strike its general character and explained

its success. In St. Petersburg, the strike’s most im-

portant site in terms of its political outcome, the

participation of tram drivers, shop clerks, phar-

macists, printers, and even insurance, zemstvo, and

bank employees, meant that the center of the cap-

ital closed down, bringing the strike directly into

the lives of most citizens by encompassing the

broadest array of occupations and the broadest so-

cial spectrum of all the strikes in 1905.

Many of the worker strikes supplemented their

factory demands with demands for political rights

and liberties, so that the labor strikes blended seam-

lessly with the broader, ongoing political protests

of the democratic opposition. University students

in particular, but also secondary schoolers and ed-

ucated professionals, promoted the strike with

gusto and imagination, especially in Moscow, St.

Petersburg, and other university towns. Students

opened their lecture halls to public meetings, where

workers met the wider urban public for the first

time and where much support for the strike was

generated. The volume of this protest gave pause

to the police and the government, providing an even

greater margin of de facto freedom of speech and

assembly. Many craft and service workers took the

opportunity to organize their first trade unions.

Several political parties, including the Kadet or Con-

stitutional Democratic Party, were organized in this

interval. Slower moving populations, such as peas-

ants, soldiers, and policemen, drew inspiration

from the widespread protests and began to demand

their rights.

The revolutionary organizations prospered

from the upsurge of labor militancy in October, re-

cruiting new members and becoming better known

among rank–and–file workers. Revolutionary or-

OCTOBER GENERAL STRIKE OF 1905

1086

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ganizers, especially Mensheviks, were indispensable

in the creation and leadership of the Soviets of

Workers’ Deputies, informal bodies of elected fac-

tory delegates organized in about fifty locales dur-

ing 1905, especially in October, to lead and assist

strikers over entire urban and industrial areas. The

Soviet of St. Petersburg, the most celebrated of these

organs of direct democracy, went beyond strike

leadership to pursue a revolutionary agenda in the

capital. Its arrest on December 3 cut short its po-

litical promise, but its brief career and its flam-

boyant second president, Leon Trotsky, inspired

similar organs in later revolutions around the

world.

In response to the January strikes, the tsarist

government had granted an elected assembly to dis-

cuss, but not implement, legislation (the “Bulygin

Duma”). To maintain the integrity of autocratic

rule, several of Emperor Nicholas’s ministers began

to advocate a unified government, headed by a

prime minister. Sensing the country’s mood in

early October and led by the respected Count Sergei

Yu. Witte, they advised Nicholas to grant political

and civil rights, legislative authority, and an ex-

panded electorate. Nicholas hesitated between lib-

eralization and forceful repression of the strikers;

after deliberating several days, he reluctantly

agreed to the former. The Manifesto of October 17

was the most significant political act of the 1905

Revolution. It provoked powerful, euphoric expec-

tations of a total transformation of Russian life.

These expectations remained over the long run,

themselves transforming Russian politics and cul-

ture, though in the short run the promise of a con-

stitutional state divided the opposition and enabled

the government to restore the authority of the au-

tocracy by early 1906 through a bloody repression

not possible in October.

See also: BLOODY SUNDAY; DUMA; NICHOLAS II; REVO-

LUTION OF 1905; WORKERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ascher, Abraham. (1988). The Revolution of 1905, Vol. 1:

Russia in Disarray. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univer-

sity Press.

Engelstein, Laura. (1982). Moscow, 1905: Working Class

Organization and Political Conflict. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Harcave, Sidney. (1964). First Blood: The Russian Revolu-

tion of 1905. New York: Macmillan.

Reichman, Henry. (1987). Railwaymen and Revolution:

Russia, 1905. Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Surh, Gerald D. (1989). 1905 in St. Petersburg: Labor, So-

ciety, and Revolution. Stanford, CA: Stanford Uni-

versity Press.

Trotsky, Leon. (1971). 1905, tr. Anya Bostock. New York:

Random House.

Verner, Andrew M. (1990). The Crisis of Russian Autoc-

racy: Nicholas II and the 1905 Revolution. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

G

ERALD

D. S

URH

OCTOBER MANIFESTO

The October Manifesto was published at the peak

of Revolution of 1905, following the general strike

of October of 1905 in which 2 million people took

to the streets and railroads were blocked. The gov-

ernment considered two possible solutions to the

crisis: a military dictatorship and liberal reforms to

win popular support. Those who supported re-

forms were led by Sergei Witte, who wrote a re-

port urging Tsar Nicholas II to grant a constitution,

a representative assembly, and civil freedoms. On

October 27 (October 14 O.S.) Nicholas ordered that

the main points of the report were to be listed in

the form of a manifesto. The draft was written

overnight by Prince Alexei Obolensky. Nicholas

signed it on October 30 (October 17 O.S.), and the

next day it was published in the newspaper Pravi-

telstvennyi Vestnik (Governmental Courier).

The October Manifesto gave the ruling body

permission to use every means to end disorders,

disobedience, and abuse, and gave the “highest gov-

ernment” the responsibility to act, in accordance

with the tsar’s “unbendable” will, to “Grant the

population the undisputable foundation for civil

freedom on the basis of protection of identity, free-

dom of conscience, speech, assemblies and unions.”

Voting rights were promised, “to some extent, to

those classes of the population that, at present, do

not have the right to vote,” and it was proclaimed

as an “undisputable rule that no law can be passed

without the approval of the Duma and for the pos-

sibility of supervision of the lawfulness of the ac-

tions of the administration to be given to the

national representatives.” The manifesto concluded

by calling upon “all true sons of Russia to end . . .

the unimaginable revolt” and, along with the em-

peror, “to concentrate all forces on restoring peace

and quiet on the homeland.”

The October Manifesto was highly controver-

sial. There were mass meetings and demonstrations

OCTOBER MANIFESTO

1087

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

welcoming its promise of freedom in the regional

capitals and many other cities. Similarly, there were

mass meetings and demonstrations, often violent,

calling for an autocracy of “patriots” and con-

demning the manifesto as perpetrated by revolu-

tionaries and Jews. In the three weeks after the

manifesto was issued, there were outbreaks of vio-

lence in 108 cities, 70 small towns, and 108 villages,

leaving at least 1,622 dead, and 3,544 crippled and

wounded.

The liberal reaction to the manifesto was mixed.

Right-wing liberals saw it as a realization of their

political hopes and united as the Union of October

17. Left-wing liberals, joining together to organize

the Constitutional Democratic Party, believed that

further reforms were needed, and their leader, Paul

Milyukov, stated that nothing changed and the

struggle would continue. Left-wing parties and

leaders saw the manifesto as a sign of the govern-

ment’s weakness; its capitulation under revolu-

tionary pressure showed that the pressure on the

government had to be intensified.

The political program embodied in the mani-

festo began to take effect on October 19, 1905, with

the appointment of a government headed by Witte.

Between October 1905 and March 1906 the gov-

ernment published a series of orders regarding po-

litical amnesties, censorship, modification of the

State Council, and other matters. All of these were

incorporated in the second edition of the Funda-

mental Laws, passed on April 23, 1906.

The most important outcome of the October

Manifesto was the creation of a bicameral repre-

sentative institution and the legalization of political

parties, trade unions and other social organizations,

and a legal oppositionist press.

See also: CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; DUMA;

FUNDAMENTAL LAWS OF 1906; OCTOBER GENERAL

STRIKE OF 1905; REVOLUTION OF 1905; WITTE, SERGEI

YULIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ascher, Abraham. (1988, 1992). The Revolution of 1905.

Vol.1: Russia in Disarray; Vol. 2: Authority Restored.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Harcave, Sidney. (1970). First Blood: The Russian Revolu-

tion of 1905. New York: Macmillan.

Harcave, Sidney, trans. and ed. (1990). The Memoirs of

Count Witte. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Mehlinger, Howard D., and Tompson, John M. (1972).

Count Witte and the Tsarist Government in the 1905

Revolution. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Szeftel, Marc. (1976). The Russian Constitution of April 23,

1906: Political Institutions of the Duma Monarchy.

Brussels: Editions de la Libraire encyclopédique.

O

LEG

B

UDNITSKII

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

During the October 1917 Russian Revolution, the

liberal, western-oriented Provisional Government

headed by Alexander Kerensky, which was estab-

lished following the February 1917 Russian Revo-

lution that overthrew Tsar Nicholas II, was removed

and replaced by the first Soviet government headed

by Vladimir Lenin. The October Revolution began

in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg), then the capital

of Russia, and quickly spread to the rest of the

country. One of the seminal events of the twenti-

eth century in terms of its worldwide historical im-

pact, the October Revolution is also one of the most

controversial and hotly debated historical events in

modern times.

Most western historians, especially at the

height of the Cold War, viewed the October Revolu-

tion as a brilliantly organized military coup d’état

without significant popular support, carried out by

a tightly knit band of professional revolutionaries

brilliantly led by the fanatical Lenin. This interpre-

tation, severely undermined by western “revision-

ist” social history in the 1970s and 1980s, was

rejuvenated after the dissolution of the Soviet

Union at the end of the Gorbachev era, even though

information from newly declassified Soviet archives

reinforced the revisionist view. At the other end of

the political spectrum, for nearly eighty years So-

viet historians, bound by strict historical canons

designed to legitimate the Soviet state and its lead-

ership, depicted the October Revolution as a broadly

popular uprising of the revolutionary Russian

masses. According to them, this social upheaval

was deeply rooted in Imperial Russia’s historical de-

velopment and shaped by universal laws of history

as formulated by Karl Marx and Lenin. There are

kernels of truth and considerable distortion in both

of these interpretations.

WAR AND REVOLUTION

The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 found

Russian politics and society in great flux. To be

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

1088

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

sure, the autocratic tsarist political system had

somehow managed to remain intact throughout

the revolutions of the late eighteenth and early

nineteenth centuries. Even the Revolution of 1905,

which resulted in the creation of a constitutional

monarchy with an elected parliament (the Duma),

had left predominant political authority in the

hands of Tsar Nicholas II. The abolition of serfdom

by Alexander II in 1861 had freed the Russian peas-

antry, the vast bulk of the empire’s population,

from personal bondage. However, the terms of the

emancipation were such that most peasants re-

mained impoverished. Moreover, a fundamental

land reform program initiated by Peter Stolypin in

1906 was so complex that, irrespective of the

long-term prospects, when it was interrupted by

the war in 1914, the Russian countryside was in

particularly great turmoil.

In the late nineteenth century, enlightened

officials such as Sergei Witte had reversed govern-

ment opposition to industrialization and spear-

headed a program of rapid economic development.

However, the pace of this development was too

slow to meet Russia’s needs, and the industrial rev-

olution resulted in the crowding of vast numbers

of immiserated workers into squalid, rat-infested

factory ghettos in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and

other major Russian cities. It is small wonder, then,

that in the opening years of the twentieth century,

the major Russian liberal and socialist political par-

ties that were destined to play key roles in 1917

took shape and began to attract popular follow-

ings. Likewise, it is no surprise that the Russian

government was suddenly faced with a growing,

increasingly ambitious and assertive professional

middle class, waves of peasant rebellions, and bur-

geoning labor unrest.

Framed against these political and social reali-

ties, the significant degree of popular support en-

joyed by the Russian government at the start of

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

1089

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

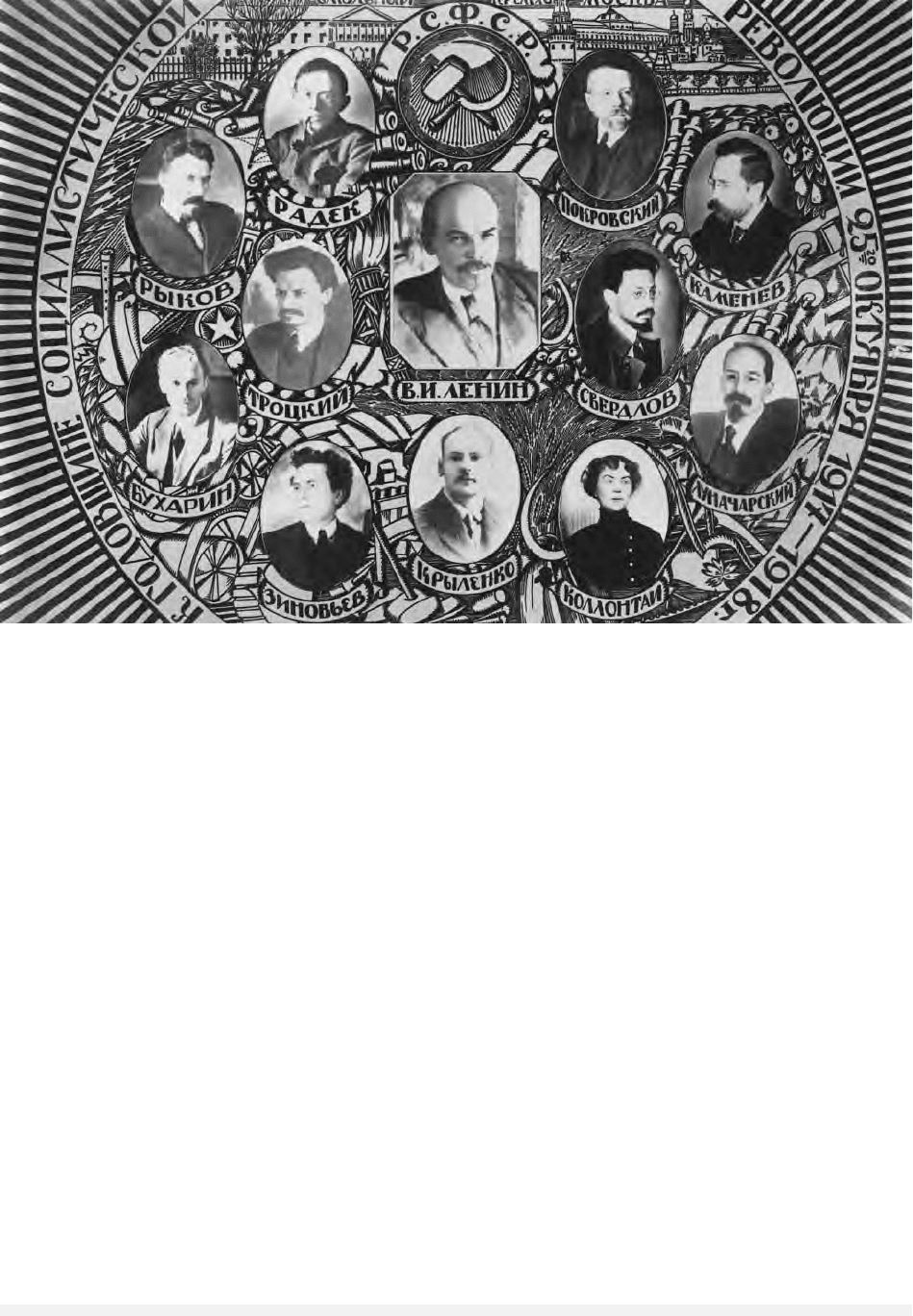

Leaders of the Bolshevik party are pictured around their leader, Vladimir Lenin. Top row (from left): Rykov, Radek, Pokrovsky,

Kamenev; middle row: Trotsky, Lenin, Sverdlov; bottom row: Bukharin, Zinoviev, Krylenko, Kollontai, Lunacharsky. Stalin is not

included in this 1920 collage. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

the war, in so far as it was visible, must have

been heartening to Nicholas II. The Constitutional

Democratic or Kadet Party, Russia’s main liberal

party, officially proclaimed a moratorium on op-

position to the monarchy and pledged its unqual-

ified support for the war effort. Beginning in early

1915, when the government’s extraordinary in-

competence became fully apparent, the Kadets, de-

spite their anguish, made use of the Duma only to

call for the appointment of qualified ministers

(rather than demand fundamental structural

change). With good reason, they calculated that a

political upheaval in the existing circumstances

would be equally damaging to the war effort and

prospects for the eventual creation of a liberal, de-

mocratic government. Members of the populist So-

cialist Revolutionary (SR) Party and the moderate

social democratic Menshevik Party were split be-

tween “defensists,” who supported the war effort,

and “internationalists,” who sought an immediate

cessation of hostilities and a compromise peace

without victors or vanquished. Only Lenin advo-

cated the fomenting of immediate social revolution

in all of the warring countries; however, for the

time being, efforts by underground Bolshevik com-

mittees in Russia to kindle popular opposition to

the war failed.

The February 1917 Revolution, which grew

out of prewar instabilities and technological back-

wardness, along with gross mismanagement of the

war effort, continuing military defeats, domestic

economic dislocation, and outrageous scandals sur-

rounding the monarchy, resulted in the creation of

two potential Russian national governments. One

was the Provisional Government formed by mem-

bers of the Duma to restore order and to provide

leadership pending convocation of a popularly

elected Constituent Assembly based on the French

model. The Constituent Assembly was to design

Russia’s future political system and take responsi-

bility for the promulgation of other fundamental

reforms. The second potential national government

was the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’

Deputies and its moderate socialist-led Executive

Committee. Patterned after similar “worker parlia-

ments” formed during the Revolution of 1905, in

succeeding weeks similar institutions of popular

self-government were established throughout ur-

ban and rural Russia. In early summer 1917, the

First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’

and Soldiers’ Deputies and the First All-Russian

Congress of Peasants’ Deputies formed leadership

bodies, the All-Russian Central Executive Commit-

tee of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies and the

All-Russian Executive Committee of Peasants’

Deputies, to represent soviets around the country

between national congresses. Until the fall of 1917,

when it was taken over by the Bolsheviks, the Ex-

ecutive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet strived

to maintain order and protect the revolution until

the convocation of the Constituent Assembly. This

was also true of the All-Russian Central Executive

Committee of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies and

the All-Russian Executive Committee of Peasants’

Deputies. The Soviet, led by the moderate social-

ists, made no effort to take formal power into its

own hands, although it was potentially stronger

than the Provisional Government because of its

vastly greater support among workers, peasants,

and lower–level military personnel. This support

skyrocketed in tandem with popular disenchant-

ment with the economic results of the February

Revolution, the effort of the Provisional Govern-

ment to continue the war effort, and its procrasti-

nation in convening the Constituent Assembly.

“ALL POWER TO THE SOVIETS!”

At the time of the February Revolution, Lenin was

in Switzerland. He returned to Petrograd in early

April 1917, demanding an immediate second, “so-

cialist” revolution in Russia. Although he backed

off this goal after he acquainted himself with the

realities of the prevailing situation (including little

support for precipitous, radical revolutionary ac-

tion even among Bolsheviks), his great achievement

at this time was to orient the thinking of the Bol-

shevik Party toward preparation for the replace-

ment of the Provisional Government by a leftist

“Soviet” government as soon as the time was ripe.

Nonetheless, in assessing Lenin’s role in the Octo-

ber Revolution, it is important to keep in mind that

he was either away from the country or in hiding

and out of regular touch with his colleagues in

Russia for much of the time between February and

October 1917. In any case, top Bolshevik leaders

tended to be divided into three distinct groups:

Lenin and Leon Trotsky, among others, for whom

the establishment of revolutionary soviet power in

Russia was less an end in itself than the trigger for

immediate worldwide socialist revolution; a highly

influential group of more moderate national party

leaders led by Lev Kamenev for whom transfer of

power to the soviets was primarily a vehicle for

building a strong alliance of left socialist groups

which would form a socialist coalition government

to prepare for fundamental social reform and peace

negotiations by a socialist-friendly Constituent As-

sembly; and a middle group of independent-minded

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

1090

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

leaders whose views on the development of the rev-

olution fluctuated in response to their reading of

existing conditions.

Then too, events often moved so rapidly that

the Bolshevik Central Committee had to develop

policies without consulting Lenin. Beyond this, cir-

cumstances were frequently such that structurally

subordinate party bodies had perforce to develop

responses to evolving realities without guidance or

contrary to directives from the center. Also, in 1917

the doors to membership were opened wide, and

the Bolshevik organization became a genuine mass

political party. In part as a result of such factors,

Bolshevik programs and policies in 1917 tended to

be developed democratically, with strong inputs

from rank-and-file members, and therefore re-

flected popular aspirations.

Meanwhile, the revolution among factory work-

ers, soldiers, sailors, and peasants had a dynamic

of its own. At times, the Bolsheviks followed the

masses rather than vice versa. For example, on July

14 (July 1 O.S.) the Bolshevik Central Committee,

influenced by party moderates, began preparing for

a left–socialist congress aimed at unifying all in-

ternationalist elements of the “Social Democracy”

(e.g., Menshevik-Internationalists and Left SRs)

in support of common revolutionary goals. Yet

only two days later, radical elements of the Bol-

shevik Petersburg Committee and Party Military

Organization (responsive to their ultra-militant

constituencies) helped organize the abortive July

uprising, against the wishes of Lenin and the Cen-

tral Committee, who considered such action pre-

mature.

The July uprising ended in an apparent defeat

for the Bolsheviks. Lenin was forced into hiding,

numerous Bolshevik leaders were jailed, and efforts

to form a united left-socialist front were tem-

porarily ended. Still, in light of the success of the

Bolsheviks in the October Revolution, perhaps the

main significance of the July uprising was that it

reflected the great popular attraction for the Bol-

shevik revolutionary program, as well as the party’s

strong links to Petrograd’s lower classes, links that

would prove valuable over the long term.

What was the Bolsheviks’ program? Contrary

to conventional wisdom, in 1917 the Bolsheviks did

not stand for a one-party dictatorship (neither in

July nor at any time before the October Revolu-

tion). Rather, they stood for democratic “people’s

power,” exercised through an exclusively socialist,

soviet, multiparty government, pending convoca-

tion of the Constituent Assembly. The Bolsheviks

also stood for more land to individual peasants,

“workers’ control” in factories, prompt improve-

ment of food supply, and, most important, an early

end to the war. All of these goals were neatly pack-

aged in the slogans “Peace, Land, and Bread!” “All

Power to the Soviets!” and “Immediate Convoca-

tion of the Constituent Assembly!” The interplay

and political value of these two key factors—the

attractiveness of the Bolshevik platform and the

party’s carefully nurtured links to revolutionary

workers, soldiers, and sailors—were evident in the

fall of 1917, after the left’s quick defeat of an un-

successful rightist putsch led by the commander-

in-chief of the Russian army, General Lavr Kornilov

(the so-called Kornilov affair).

THE BOLSHEVIKS COME TO POWER

Following the ill–fated July uprising, Lenin, alien-

ated by moderate socialist attacks on the Bolsheviks

and by their support of the Provisional Government

and dismissive of the soviets’ revolutionary poten-

tial, tried unsuccessfully to persuade the party lead-

ership to abandon its emphasis on transfer of

power to the soviets and shift its strategy to a uni-

lateral seizure of power. Subsequently, in the af-

termath of the Kornilov affair, during which Lenin

remained in hiding, he briefly reconsidered this po-

sition and allowed for a peaceful transition to so-

viet power. However, this moderation was fleeting.

Isolated from day-to-day developments and deci-

sion making in the Russian capital, and evidently

influenced primarily by clear signs of deepening so-

cial unrest at home and abroad, at the end of Sep-

tember (mid-September O.S.) Lenin decided that the

time had come for another revolution in Russia:

a socialist revolution that would serve as the cat-

alyst for popular rebellions in other European

countries. In two emphatic letters to Bolshevik

committees in Petrograd written from a hideout in

Finland, he now demanded that the party organize

an armed uprising “without losing a single mo-

ment.”

These letters were received in Petrograd at a time

when prospects for peaceful creation of an exclu-

sively socialist government suddenly brightened.

After passage by the Petrograd Soviet of a momen-

tous Bolshevik resolution to this effect proposed by

Kamenev, the Bolsheviks won majority control

of that key body. Trotsky became its chairman.

Around the same time, the Bolsheviks also gained

control of the Moscow Soviet. Moreover, the Bol-

shevik leadership was just then focused on trying

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

1091

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

to persuade the Democratic State Conference, a na-

tional conference of “democratic” organizations

convened to reconsider the government question, to

abjure further coalition with the Cadets and to es-

tablish exclusively socialist rule. A hastily convened

secret emergency meeting of the party Central Com-

mittee unceremoniously rejected Lenin’s directives

within hours of their receipt. For the Bolsheviks,

this was just as well. Not long after the October

Revolution, Lenin himself acknowledged this. The

party was saved from likely disaster by the stub-

born resistance of national and lower-level Bolshe-

viks on the spot who, like Kamenev, were primarily

concerned with building the broadest possible sup-

port for the formation of an exclusively socialist

government or were skeptical of Lenin’s strategy of

mobilizing the masses behind an “immediate bayo-

net charge” independent of the soviets.

In part as a consequence of their continuing in-

teraction with workers, soldiers, and sailors, these

leaders on the scene possessed a more realistic ap-

preciation than Lenin of the limits of the party’s

influence and authority among the Petrograd lower

classes, as well as of their allegiance to soviets as

legitimate democratic organs in which all genuinely

revolutionary groups would work to fulfill the

revolution. They were forced to recognize that by

appearing to usurp the prerogatives of the soviets

they risked losing a good deal of their hard–won

popular support and suffering a defeat as great as,

if not greater than, the one they had suffered in

July. Therefore, after hopes that the Democratic

State Council would initiate fundamental political

change were dashed, they reoriented their tactics

toward the formation of an exclusively socialist

government at another All-Russian Congress of So-

viets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, which at

the insistence of leftist delegates to the Democratic

State Conference was scheduled for early Novem-

ber (late October O.S.). At the same time, the Bol-

shevik Central Committee initiated steps to convene

an emergency party congress just prior to the start

of the soviet congress. This was to be the forum in

which the party’s revolutionary tactics, and the

closely related question of the nature and makeup

of a future government, were to be decided.

Meanwhile, Lenin had moved to the Petrograd

suburbs and intensified pressure for immediate rev-

olutionary action. As a result, on October 23 (Oc-

tober 10 O.S.), the Bolshevik Central Committee,

with Lenin in attendance, resolved to make the

seizure of power “the order of the day.” However,

in the days immediately following, it became clear

that most Petrograd workers and soldiers would

not participate in a unilateral call to arms against

the Provisional Government by the Bolsheviks prior

to the start of the national Congress of Soviets,

scheduled to open on November 7 (October 25

O.S.). Kamenev, the leader of party moderates, was

so alarmed by the possibility that the party would

act precipitously that he virtually disclosed the

Central Committee’s decision in Novaia zhizn (New

Life), the Left Menshevik newspaper edited by the

writer Maxim Gorky.

Consequently, with considerable wavering

caused largely by pressure for bolder direct action

from Lenin, the Bolshevik leadership in Petrograd

pursued a strategy based on the following general

principles: (1) that the soviets (because of their

stature in the eyes of workers and soldiers), and

not party groups, should be employed for the over-

throw of the Provisional Government; (2) that for

the broadest support, any attack on the govern-

ment should be masked as a defensive operation on

behalf of the soviet; (3) that action should there-

fore be delayed until a suitable excuse for giving

battle presented itself; (4) that to undercut poten-

tial resistance and to maximize the possibility of

success, every opportunity should be utilized to

subvert the authority of the Provisional Govern-

ment peacefully; and (5) that the formal removal

of the existing government should be linked with

and legitimized by the decisions of the Second Con-

gress of Soviets. At the time, Lenin mocked this ap-

proach. However, considering the development of

the revolution to that point, as well as the views

of a majority of leading Bolsheviks around the

country, it appeared as a natural, realistic response

to the prevailing correlation of forces and popular

mood.

Between November 3 and 6 (October 21–24

O.S.), a majority of Bolshevik leaders staunchly re-

sisted immediate revolutionary action in favor of

preparing for a decisive struggle against the Provi-

sional Government at the congress. Among other

things, in the party’s press and at huge public ral-

lies they attacked the policies of the Provisional

Government and reinforced popular support for the

removal of the Provisional Government by the Con-

gress of Soviets. Moreover, they reached out to the

Menshevik-Internationalists and Left SRs. Simulta-

neously, using as an excuse the Provisional Gov-

ernment’s announced intention of transferring the

bulk of the Petrograd garrison to the front, and

cloaking every move as a defensive measure against

the counterrevolution, they utilized the Bolshevik-

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

1092

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY