Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

shock battalions from the suburbs were called to

the Winter Palace, the seat of the government, and

the main Bolshevik newspaper, Rabochii put (Work-

ers’ Path), was shut down. Not until these steps

had been taken, and even then only after Lenin’s

personal direct intervention in the party’s head-

quarters at Smolny, did the military action against

the Provisional Government begin, action that

Lenin had been demanding for a month. This oc-

curred before dawn on November 7 (October 25

O.S.). At that time, all pretense that the MRC was

simply defending the revolution and attempting

primarily to maintain the status quo pending ex-

pression of the congress’s will was abruptly dropped.

Rather, an open, all-out effort was launched to con-

front congress delegates with the overthrow of the

Provisional Government prior to the start of their

deliberations.

During the morning of November 7, military

detachments supporting the MRC seized strategi-

cally important bridges, key government buildings,

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

1093

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

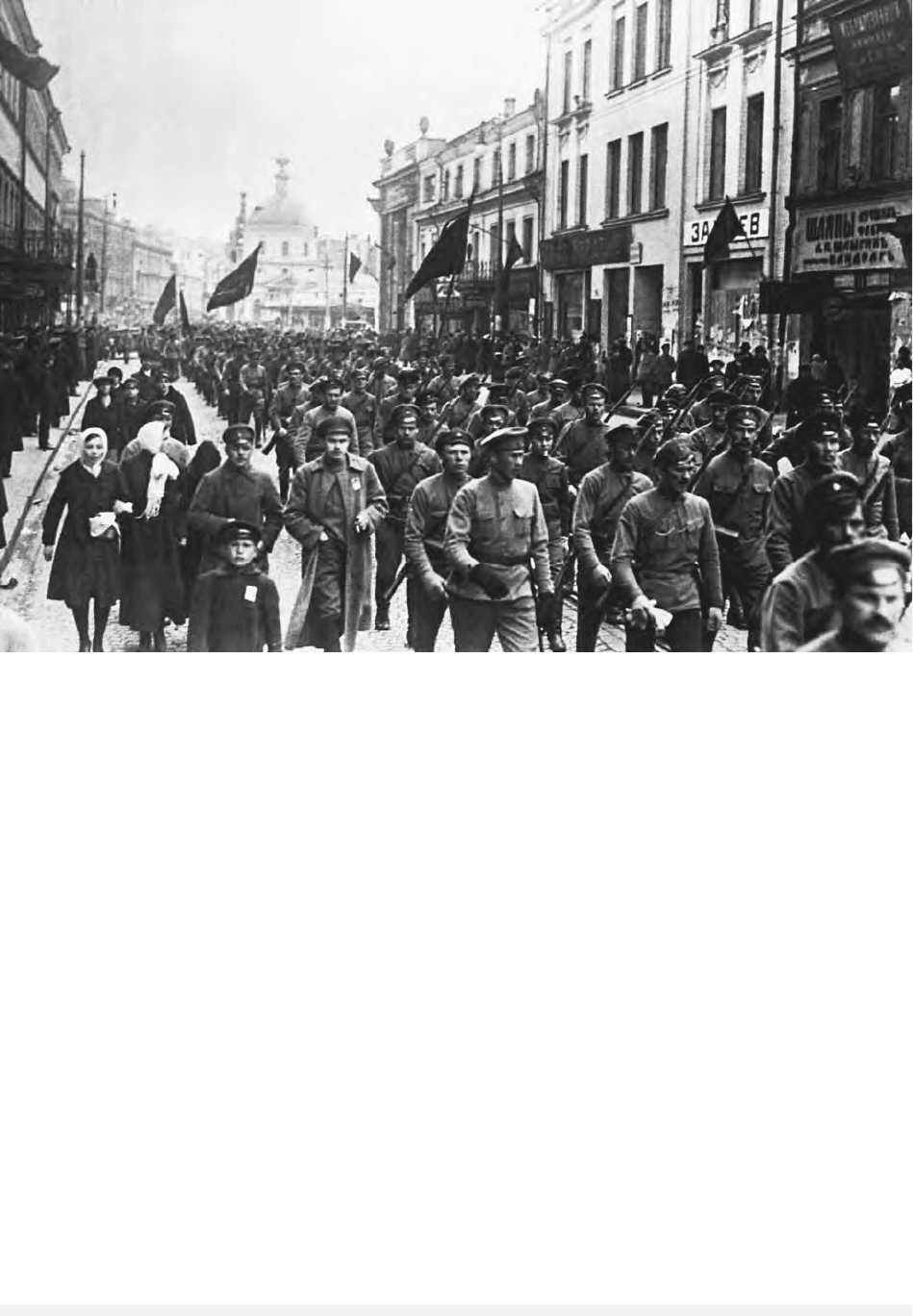

Red Guards marching through the streets of Moscow in 1917. © CORBIS

dominated Military Revolutionary Committee of

the Petrograd Soviet (MRC), established to monitor

the government’s troop dispositions, to take con-

trol of most Petrograd-based military units.

Weapons and ammunition from the city’s main ar-

senals were distributed to supporters. Although the

MRC did not cross the boundary between moves

that could be justified as defensive and moves that

might infringe on the prerogatives of the congress,

for practical purposes the Provisional Government

was disarmed without a shot being fired.

In response, early on the morning of Novem-

ber 6 (October 24 O.S.), only hours before the

scheduled opening of the Second All-Russian Con-

gress of Soviets, a majority of which was poised to

vote in favor of forming an exclusively socialist,

Soviet government, Kerensky took steps to sup-

press the left. Orders were issued for the rearrest

of leading Bolsheviks who had been detained after

the July uprising and released at the time of the

Kornilov Affair. Loyalist military school cadets and

rail and power stations, communication facilities,

and the State bank without bloodshed. They also

laid siege to the Winter Palace, defended by only

meager, demoralized, and constantly dwindling

forces. Kerensky managed to flee to the front in

search of troops before the ring was closed. The

“storming of the Winter Palace,” dramatically de-

picted in an Eisenstein film, was a Soviet myth. Af-

ter nightfall, the historic building was briefly

bombarded by cannon from the Fortress of Peter

and Paul and occupied with little difficulty, after

which remaining members of the government were

arrested.

The Soviet Congress was faced with a fait ac-

compli. Lenin proclaimed the demise of the Provi-

sional Government even before the congress opened

that night. The thunder of cannon punctuated

its first sessions. The effect was precisely what

Lenin hoped for and what Bolshevik moderates,

Menshevik-Internationalists, and Left SRs feared.

The Mensheviks, SRs, and even the Menshevik-

Internationalists responded to Bolshevik violence by

walking out of the congress. Lenin now superin-

tended passage of the revolutionary Bolshevik pro-

gram by the rump congress and the appointment

of an interim Soviet national government (the So-

viet of People’s Commissars or Sovnarkom) made up

exclusively of Bolsheviks.

Still, as delegates departed Smolny at the close

of the Second Congress on the morning of No-

vember 9 (October 27 O.S.), the vast majority of

them, most Bolsheviks included, expected that all

genuine revolutionary groups would unite behind

the interim government they had created and that

it would quickly be reconstructed according to the

Bolshevik pre-October platform: that is, as an ex-

clusively socialist, Soviet coalition government re-

flecting the relative strength of the various socialist

parties originally in the congress and supportive of

its revolutionary decrees. Important exceptions to

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

1094

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soldiers fire rifles in Palace Square outside the Winter Palace. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

Bolshevik leaders holding this views included Lenin

and Trotsky who, having successfully engineered

the overthrow of the Provisional Government be-

fore the start of the Congress of Soviets, were now

most concerned to retain complete freedom of ac-

tion at virtually any price. Most departing dele-

gates also believed that the new government would

in any case yield its authority to the Constituent

Assembly, scheduled to be elected at the end of No-

vember.

Among political parties seeking to restore a

broad socialist alliance and to restructure the Sov-

narkom in the immediate aftermath of the Second

Congress, most prominent were the Menshevik-

Internationalists and the Left SRs; the latter were

especially important to the success of the revolu-

tion because of their growing strength among peas-

ants in the countryside, where Bolshevik influence

was critically weak. Among labor organizations

seeking to play a similar role was the All-Russian

Executive Committee of the Union of Railway

Workers (Vikzhel). Vikzhel announced that it would

declare an immediate nationwide rail stoppage if

the Bolsheviks did not participate in negotiations to

create a homogeneous socialist government re-

sponsible to the soviets and including all socialist

groups.

Under Vikzhel’s aegis, intensive talks were

held in Petrograd November 11–18 (October 29–

November 5 O.S.). With Kamenev in charge of

negotiations for the Bolsheviks, they began auspi-

ciously. Indeed, on November 2 even the Bolshevik

press reported that the discussions were on

the verge of success. However, they ultimately

foundered, primarily because of such factors as the

impossibly high demands made by the moderate

socialists (essentially requiring repudiation of So-

viet power and most of the accomplishments of the

Second Congress, as well as the exclusion of Lenin

and Trotsky from any future government), the de-

feat by Soviet forces of an internal insurrection and

of loyalist Cossack units outside Petrograd, and the

consolidation of Soviet power in Moscow. These

factors immeasurably strengthened Lenin’s and

Trotsky’s hands, enabling them to torpedo the

Vikzhel talks. During the run–up to the Constituent

Assembly in December, Bolshevik moderates made

a valiant bid to steer the party’s delegation toward

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

1095

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Revolutionaries unfurl the red flag in Moscow in 1918. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

support of its right to define Russia’s future polit-

ical system. However, by then the moderates had

been squeezed out of the party leadership, and this

effort also failed. All of this made a long and bit-

ter civil war inevitable.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

The October Revolution cannot be adequately char-

acterized as either a military coup d’état or a pop-

ular uprising (although it contained elements of

both). Its roots are to be found in the peculiarities

of prerevolutionary Russia’s political, social, and

economic development, as well as in Russia’s

wartime crisis. At one level, it was the culminat-

ing event in a drawn-out battle between leftists and

moderates: on the one hand, an expanding spec-

trum of left socialist groups supported by the vast

majority of Petrograd workers, soldiers, and sailors

dissatisfied by the results of the February revolu-

tion; and on the other, the increasingly isolated lib-

eral–moderate socialist alliance that had taken

control of the Provisional Government and national

Soviet leadership during the February days. By the

time the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets

convened on November 7 (October 25 O.S.), the rel-

atively peaceful victory of the former was all but

assured. At another level, the October Revolution

was a struggle, initially primarily within the Bol-

shevik leadership, between proponents of a multi-

party, exclusively socialist government that would

lead Russia to a Constituent Assembly in which so-

cialists would have a dominating voice, and Lenin-

ists, who ultimately favored violent revolutionary

action as the best means of striking out on an

ultra-radical, independent revolutionary course in

Russia and triggering decisive socialist revolutions

abroad.

Muted for much of 1917, this conflict erupted

with greatest force in the wake of the February

Revolution, in the immediate aftermath of the July

uprising, and during the periods immediately pre-

ceding and following the October Revolution. Such

factors as the walkout of Mensheviks and SRs

from the Second All–Russian Congress of Soviets,

prompted by the belated military operations pressed

by Lenin and precipitated by Kerensky; the adop-

tion of the Bolshevik program at the Second

All-Russian Congress of Soviets; the intransigence

of the moderate socialists at the Vikzhel talks; and

the Bolsheviks’ first military victories over loyalist

forces decisively undermined the efforts of moder-

ate Bolsheviks to achieve a multiparty, socialist

democracy and facilitated the rapid ascendancy of

Leninist authoritarianism. In this sense, the Octo-

ber Revolution extinguished prospects for the de-

velopment of a Western-style democracy in Russia

for the better part of a century. Also, in the im-

mediate post-revolutionary years, it led to the cat-

astrophic Russian civil war. Finally, it laid the

foundation for Stalinism and the Cold War. How-

ever, despite these outcomes, the October revolu-

tion was in large measure a valid expression of

popular aspirations.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; FEBRU-

ARY REVOLUTION; JULY DAYS; LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH;

REVOLUTION OF 1905; TROTSKY, LEON DAVIDOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Acton, Edward. (1990). Rethinking the Russian Revolution.

London: Edward Arnold.

Acton, Edward; Cherniaev,Vladimir Iu.; and Rosenberg,

William G., eds. (1997). Critical Companion to the

Russian Revolution, 1914–1921. Bloomington: Indi-

ana University Press.

Figes, Orlando. (1989). A People’s Tragedy: The Russian

Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Melgunov, S. P. (1972). Bolshevik Seizure of Power, tr.

James S. Beaver. Santa Barbara, CA: Clio.

Pipes, Richard. (1990). The Russian Revolution. New York:

Knopf.

Rabinowitch, Alexander. (1976). The Bolsheviks Come to

Power: The Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd. New York:

Norton.

Raleigh, Donald J. (1986). Revolution on the Volga: 1917

in Saratov. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bone, Ann, tr. (1974). The Bolsheviks and the October Rev-

olution: Minutes of the Central Committee of the Russ-

ian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) August

1917–February 1918. London: Pluto Press.

Sukhanov, N. N. (1962). The Russian Revolution, 1917,

tr. and ed. Joel Carmichael. New York: Harper.

Wildman, Allan. (1987). The End of the Russian Imperial

Army, Vol. 2: The Road to Soviet Power and Peace.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

A

LEXANDER

R

ABINOWITCH

OCTOBRIST PARTY

The Octobrist Party was founded in 1906 by Rus-

sian moderate liberals, taking its name from the

October Manifesto. Unequivocal support for the new

constitutional system and rejection of compulsory

OCTOBRIST PARTY

1096

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

land expropriation except in extreme state need dis-

tinguished it from the major left party, the Con-

stitutional Democratic Party (Cadets), which

represented more radical liberal opinion.

In the elections to the First and Second Dumas

(1906–1907), the Octobrist Party fared relatively

poorly while parties to its left had strong show-

ings. The government, finding itself unable to work

with the first two Dumas, dissolved them. Alexan-

der Guchkov, the Octobrists’ first leader, during the

Second Duma softened some of the party’s posi-

tions, thus enabling cooperation with the govern-

ment. Loyalty to the new constitutional system

and willingness to work with the government to

achieve its full implementation and accompanying

social reform were now the broad guiding princi-

ples of the party. Dissolving the Second Duma, Pe-

ter Stolypin, chairman of the Council of Ministers

(1906–1911), restricted the voting franchise which

lessened the voting power of the peasants and

working classes. His goal was to limit the number

of radical left deputies and increase Octobrist Party

representation so that it could provide a solid base

of support for the government in the Duma.

Stolypin found himself in a difficult position in the

Duma, stuck between the right with its hatred for

the new system and the radical left. In the 1907

elections to the Third Duma the Octobrist Party

more than tripled its representation, receiving 153

seats.

The party’s unity and its relationship with the

government depended on the latter’s dedication to

the spirit of the constitutional system and policy

of reform. The great increase in the party’s num-

bers made maintenance of unity between its left

and right wings problematic.

Initially the Stolypin-Octobrist alliance worked

relatively well, especially in regard to peasant re-

form. However, by 1909 conservatives fearful of

the institutionalization of the new system by the

Stolypin–Octobrist partnership worked to break it.

The Naval General Staff crisis was the first step in

this direction. The Octobrists regarded Nicholas II’s

rejection, with the urging of conservatives, of a bill

concerning the Naval General Staff that had already

been passed by both houses of parliament, as a

violation of the spirit of the October Manifesto.

Conservative attacks on Stolypin and increased

fragmentation within the party forced Stolypin to

turn increasingly to the right, thereby placing his

relationship with the Octobrists and their unity un-

der additional strain.

In 1911 the conservatives in the State Council,

with the help of Nicholas II, rejected the Western

Zemstvo Bill already passed by the Duma. Stolypin,

infuriated by constant conservative attempts to

block his policies, forced Nicholas II to disband the

parliament provisionally, as allowed by Article 87

of the Fundamental Laws, and make the bill law

by decree. The Octobrists, although they had sup-

ported this bill, considered Stolypin’s step to be a

betrayal and undermining of the constitutional

system. They went into opposition.

In elections to the Fourth Duma (1912), the Oc-

tobrists, while remaining the largest party, saw their

share of the vote collapse to ninety-five. Morale in

the party was at an all-time low, reflecting the over-

all disappointment with the gradual but successful

emasculation of the constitutional system by con-

servatives and Nicholas II.

Octobrist unity cracked in 1913 when Guchkov,

admitting that attempts to cooperate with the gov-

ernment to achieve needed reform had failed, urged

adoption of a more aggressive stance toward the

government, which since the assassination of

Stolypin in 1911 had showed few signs of contin-

uing reform. While the Central Committee sup-

ported this step, the larger body of deputies split

on this issue. Disappointed with lack of party back-

ing for such a move, some twenty-two deputies

formed the Left Octobrists. The majority formed

the Zemtsvo Octobrists under the leadership of

M.V. Rodzyanko, the party’s leader. Some ten to

fifteen remained uncommitted to either side. The

party ceased to have any real power.

The weakening and fragmentation of the Oc-

tobrist Party mirrored the collapse of Russia’s ex-

periment with constitutional monarchy.

See also: CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; NICHOLAS

II; OCTOBER MANIFESTO; STOLYPIN, PETER ARKADIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hosking, Geoffrey. (1973). The Russian Constitutional Ex-

periment: Government and Duma, 1907–1914. London:

Cambridge University Press.

Seton-Watson, Hugh. (1991). The Russian Empire,

1801–1917. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Waldron, Peter. (1998). Between Two Revolutions: Stolypin

and the Politics of Renewal in Russia. London: UCL

Press.

Z

HAND

P. S

HAKIBI

OCTOBRIST PARTY

1097

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ODOYEVSKY, VLADIMIR FYODOROVICH

(1804–1869), romantic and gothic fiction writer,

pedagogue, musicologist, amateur scientist, and

public servant.

A Russian thinker with encyclopedic knowledge

whom contemporaries dubbed “the Russian Faust”

(a character in one of his novels), Vladimir

Odoyevsky was mentioned in his day in the same

breath as Alexander Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol. He

is perhaps best known for the philosophical fan-

tasy Russian Nights (Russkie nochi), published in

1844. In 1824–1825 he edited, with Wilhelm

Küchelbecker, four issues of the influential period-

ical Mnemosyne. Its purpose was to champion Russ-

ian literature and German philosophy at a time

when everyone else seemed fascinated with French

ideas. Odoyevsky contributed works such as “The

City Without a Name” (1839) to Nekrasov’s in-

fluential magazine Sovremennik (Contemporary). In

1823 he founded a group called “Lovers of Wis-

dom” (Lyubomudry, a literal translation of the Greek

word “philosophy”). Propounding ideas of philo-

sophic realism, the group was dissolved soon after

the Decembrist uprising in 1825, even though the

group’s pursuits truly were only philosophical, not

political. The failed rebellion deeply affected

Odoyevsky, because—like the poet Pushkin—he

had many friends among the Decembrists, includ-

ing his cousin, the poet and guards’ officer, Alexan-

der Odoyevsky (1802–1839), and the writer

Wilhelm Küchelbecker (1797–1846), both of whom

were imprisoned and exiled after the uprising.

A Slavophile of sorts, Odoyevsky believed in the

decline of the West and the future greatness of Rus-

sia. He met regularly with other Slavophile thinkers,

such as Ivan Kireyevsky, Alexander Koshelev, Mel-

gunov, Stepan Shevyrev, Mikhail Pogodin (the last

two were professors at Moscow State University),

and the young poet Dmitry Venevitinov.

In the 1830s Odoyevsky was preoccupied with

political questions, antislavery, anti-Americanism,

Russian messianism, the innate superiority of

Russia over the West, and criticisms of Malthus,

Bentham, and the Utilitarians. The novel Russian

Nights contains a mixture of these ideas.

Odoyevsky proposed a revealing subtitle, which his

editor later rejected: “Russian Nights, or the Indis-

pensability of a New Science and a New Art.”

Throughout the novel the main characters grapple

with topics such as the meaning of science and art,

logic, the sense of human existence, atheism and

belief, education, government rule, the function of

individual sciences, madness and sanity, poetic cre-

ation, Slavophilism, Europe and Russia, and mer-

cantilism.

Odoyevsky also cherished music and musi-

cians, composing chamber music as early as his

teens and writing critical appraisals of composers

such as Mikhail Glinka. He was devoted to the his-

tory and structure of church singing and collected

notational manuscripts to preserve them for future

generations. As he wrote in one of his letters: “I

discovered the definite theory of our melodies and

harmony, which is similar to the theory of me-

dieval Western tunes, but has its own peculiari-

ties.”

Odoyevsky excelled the most in the genre of

the short story, particularly ones geared toward

children. Two stories rank among the best in chil-

dren’s fare: “Johnny Frost” and “The Town in a

Snuff Box.” Generally, Odoyevsky’s fiction reflects

two main tendencies. First, he expresses his philo-

sophical convictions imaginatively and often fan-

tastically. His stories typically move from a

recognizable setting to a mystical realm. Secondly,

he injects commentary on the shortcomings of so-

cial life in Russia, usually in a satiric mode.

See also: GOLDEN AGE OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE; LOVERS

OF WISDOM, THE; SLAVOPHILES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cornwell, Neil. (1998). Vladimir Odoevsky and Romantic

Poetics: Collected Essays. Providence, RI: Berghahn

Books.

Minto, Marilyn. (1994). Russian Tales of the Fantastic.

London: Bristol Classical Press.

Rydel, Christine. (1999). Russian Literature in the Age of

Pushkin and Gogol. Detroit: Gale Group.

Smith, Andrew. (2003). Empire and the Gothic: the Poli-

tics of Genre. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

OFFICIAL NATIONALITY

In 1833, Sergei Uvarov, in his first published cir-

cular as the new minister of education, coined the

tripartite formula “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nation-

ality” as the motto for the development of the Russ-

ian Empire. The three terms also became the main

ingredients of the doctrine that dominated the era

ODOYEVSKY, VLADIMIR FYODOROVICH

1098

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of Emperor Nicholas I, who reigned from 1825 to

1855, and that came to be called “official nation-

ality.” About two dozen periodicals, scores of

books, and the entire school system propagated the

ideas and made them the foundation for guiding

Russia to modernity without succumbing to ma-

terialism, revolutionary movements, and blind im-

itation of foreign concepts.

The meaning of Orthodoxy and autocracy were

clear. The Orthodox faith had formed the founda-

tion of Russian spiritual, ethical, and cultural life

since the tenth century, and had always acted as a

unifying factor in the nation. It also proved useful

in preaching obedience to authority. Autocracy, or

absolute monarchy, involved the conviction that

Russia would avoid revolution through the en-

lightened leadership of a tsar, who would provide

political stability but put forth timely and enlight-

ened reforms so that Russia could make constant

progress in all spheres of national life. Political the-

ory had long argued, and Russia’s historical lessons

seemed to demonstrate, that a single ruler was

needed to maintain unity in a vast territory with

varied populations.

The third term in the tripartite formula was the

most original and the most mysterious. The broad

idea of nationality (narodnost) had just become fash-

ionable among the educated public, but there was

no set definition for the concept. In 1834, Peter Plet-

nev, a literary critic and professor of Russian liter-

ature at St. Petersburg University, noted: “The idea

of nationality is the major characteristic that con-

temporaries demand from literary works . . . ,” but,

he went on, “one does not know exactly what it

means.” A variety of schools of thought on the sub-

ject arose in the 1830s and 1840s.

The romantic nationalists, led by Michael

Pogodin and Stephen Shevyrev of Moscow Univer-

sity and the journal The Muscovite, celebrated

Russia’s absolutist form of government, its unique-

ness, its poetic richness, the peace-loving virtues of

its denizens, and the notion of the Slavs as a

chosen people, all of which supposedly bestowed

upon Russia a glorious mission to save humanity

and made it superior to a “decaying” West. The

Slavophiles, led by Moscow-based landowners in-

cluding the Aksakov and Kireyevsky brothers, op-

posed such western concepts as individualism,

legalism, and majority rule, in favor of the notion

of sobornost: a community, much like a church

council (sobor), should engage in discussion, with

the aim of achieving a “chorus” of unanimous de-

cision and thus preserving a spirit of harmony, and

brotherhood. The people then would advise the tsar,

through some type of land council (zemsky sobor),

a system, the Slavophiles believed, that was the

“true” Russian way in all things. The Westerniz-

ers, in contrast, sympathized with the values of

other Europeans and assumed that Russian devel-

opment, while traveling by a different path, would

occur in the context of the liberal tradition that val-

ued the individual over the state. All three groups,

however, agreed on the necessity for emancipation,

legal reform, and freedom of speech and press.

The doctrine of official nationality represented

the government’s response to these intellectual cur-

rents, as well as to the wave of revolutions that

had spread through much of the rest of Europe be-

yond Russia’s borders. The proponents of this doc-

trine, however, did not speak with one voice. For

instance, because of their support for the existing

state, the romantic nationalists are often defined as

proponents of official nationality. However, the

most influential group, sometimes called dynastic

nationalists, included Emperor Nicholas I and the

court, and their views were propagandized in the

far-flung journalistic enterprises of Fadei Bulgarin,

Nicholas Grech, and Osip Senkovsky. Their under-

standing of narodnost was based on patriotism, a

defensive doctrine used to support the status quo

and Russia’s great-power status. For them, “Rus-

sianness,” even for Baltic Germans or Poles, re-

volved around a subject’s loyalty to the autocrat.

In other words, they equated the nation with the

state as governed by the dynasty, which was seen

as both the repository and the emblem of the na-

tional culture.

Sergei Semenovich Uvarov’s own views of na-

tionality straddled the many schools of thought.

He shared the bulk of the opinions of the dynastic

nationalists, patronized the romantic nationalists

and their journal, praised the Slavophiles for their

Orthodox spirit, and accepted some Westernizing

tendencies in Russia’s historical development. But

this architect of official nationality espoused a doc-

trine that lacked appeal and vitality. Instead of re-

garding the people as actively informing the

content of nationality, Uvarov believed that the

state should define, guide, and impose “true” na-

tional values upon a passive population. In a word,

his concept of narodnost excluded the creative ac-

tivity of the narod and made it synonymous with

loyalty to throne and altar. The doctrine, while it

achieved the stability which was its aim, proved

anachronistic and did not survive Nicholas I and

Uvarov, both of whom died in 1855.

OFFICIAL NATIONALITY

1099

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: NATIONALISM IN TSARIST EMPIRE; NATIONALI-

TIES POLICIES, TSARIST; NATION AND NATIONALITY

NICHOLAS I; SLAVOPHILES; UVAROV, SERGEI SEMEN-

OVICH; WESTERNIZERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1978). Nicholas I: Emperor and Auto-

crat of All the Russias. Bloomington: Indiana Uni-

versity Press.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas. (1967). Nicholas I and Official Na-

tionality in Russia, 1825–1855. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

Whittaker, Cynthia H. (1984). The Origins of Modern

Russian Education: An Intellectual Biography of Count

Sergei Uvarov, 1786–1855. DeKalb: Northern Illinois

University Press.

C

YNTHIA

H

YLA

W

HITTAKER

OGARKOV, NIKOLAI VASILEVICH

(1917–1994), marshal, chief of the Soviet General

Staff, Hero of the Soviet Union, (1917–1944).

Nikolai Ogarkov was one of the outstanding

military leaders of the Soviet General Staff, who

combined technical knowledge with a mastery of

combined arms operations. He was born on Octo-

ber 30, 1917, in the village of Molokovo in Tver

oblast and graduated from an engineering night

school in 1937. In 1938 he joined the Red Army

and graduated from the Kuybyshev Military Engi-

neering Academy in 1941. Ogarkov served as com-

bat engineer with a wide range of units on various

fronts throughout World War II. After the war he

completed the advanced military engineering course

at the Kuybyshev Military Engineering Academy.

Ogarkov advanced rapidly in command and staff

assignments and graduated in 1959 from the

Voroshilov Academy of the General Staff. There-

after he commanded a motorized rifle division in

East Germany and held command and staff post-

ings in various military districts. In 1968 he as-

sumed the post of deputy chief of the General Staff

and head of the Operations Directorate, where he

was involved in planning the military intervention

in Czechoslovakia. In 1974 he assumed the post of

first deputy chief of the General Staff, and then

chief of the General Staff in 1977. Ogarkov held

that post until 1984. During his tenure he over-

saw the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan and was

the voice of the Soviet government in the aftermath

of the shooting down of the Korean airliner, KAL

007. He was an articulate advocate of the Revolu-

tion in Military Affairs, which he believed was

about to transform military art. He stressed the

impact of new technologies associated with auto-

mated command and control, electronic warfare,

precision strike, and weapons based on new phys-

ical principles upon the conduct of war. His advo-

cacy of increased defense spending contributed to

his removal from office in 1984. Ogarkov died on

January 23, 1994.

See also: AFGHANISTAN, RELATIONS WITH; MILITARY, SO-

VIET AND POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kokoshin, Andrei A. (1998). Soviet Strategic Thought,

1917–91. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Odom, William E. (1998). The Collapse of the Soviet Mil-

itary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Zisk, Kimberly Marten. (1993). Engaging the Enemy: Or-

ganization Theory and Soviet Military Innovation,

1955–1991. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

OGHUZ See TORKY.

OKOLNICHY

Court rank used in pre-Petrine Russia.

The term okolnichy (pl. okolnichie) meaning

“someone close to the ruler,” is derived from the

word okolo (near, by). The sources first mention an

okolnichy at the court of the prince of Smolensk

in 1284. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries,

okolnichie acted as administrators, judges, and

military commanders, and as witnesses during

compilation of a prince’s legal documents. When a

prince was on campaign, okolnichie prepared

bridges, fords, and lodging for him. Okolnichie

usually came from local elite families. By the end

of the fifteenth century, the rank of okolnichy be-

came part of the hierarchy of the Gosudarev Dvor

(Sovereign’s Court), second after the rank of

boyar. Unlike boyars, who usually performed mil-

itary service, okolnichie carried out various ad-

ministrative assignments in the first half of the

sixteenth century. Later, the okolnichie conceded

their administrative functions to the secretaries.

OGARKOV, NIKOLAI VASILEVICH

1100

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Under Ivan IV, the majority of okolnichie belonged

to the boyar families who had long connections

with Moscow. For most elite courtiers, with the

exception of the most distinguished princely fam-

ilies, service as okolnichie was a prerequisite for re-

ceiving the rank of boyar. The rank of okolnichy

also served as a means of integrating families of

lesser status into the elite. By the end of the six-

teenth century, the distinction between boyars and

okolnichie was based largely on genealogical origin

and seniority in service. From the middle of the sev-

enteenth century, the number of okolnichie in-

creased because of the growing size of the court.

Many historians believe that all okolnichie were ad-

mitted to the royal council, the Boyar Duma,

though in fact only a few of them attended meet-

ings with the tsar.

See also: BOYAR; BOYAR DUMA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kleimola, Ann M. (1985). “Patterns of Duma Recruit-

ment, 1505–1550.” In Essays in Honor of A. A. Zimin,

ed. Daniel Clarke Waugh. Columbus, OH: Slavica.

Poe, Marshall T. (2003). The Russian Elite in the Seven-

teenth Century. 2 vols. Helsinki: The Finnish Acad-

emy of Science and Letters.

S

ERGEI

B

OGATYREV

OKUDZHAVA, BULAT SHALOVICH

(1924–1997), Russian poet, singer, and novelist.

Bulat Okudhava’s parents were both profes-

sional Party workers. In 1937 they were arrested;

the father was executed and the mother impris-

oned in the Gulag until 1955. At age seventeen

Okudzhava volunteered for the army, saw active

service, and was wounded. After the war he grad-

uated from Tbilisi University, then became a

schoolteacher in Kaluga. In 1956 he joined the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and

moved to Moscow. He worked as a literary jour-

nalist, and joined the Union of Writers in 1961. He

made his name as a prose writer with the contro-

versially unheroic war story “Goodbye, School-

boy,” and followed this with a series of historical

novels depicting various episodes from nineteenth-

century gentry life.

In the late 1950s Okudzhava pioneered “guitar

poetry” songs performed by the author to his own

guitar accompaniment. This genre drew on long-

established traditions of Russian drawing-room art

song (“romance”), student song, and gypsy song,

as well as that of the French chansonniers, who be-

came well known in Russian intellectual circles in

the late 1950s (Okudzhava’s favorite was Georges

Brassens). Okudzhava cultivated an amateur-

sounding performance manner. In actual fact,

he was an extremely gifted natural melodist, cre-

ating dozens of original and unforgettable tunes.

Okudzhava’s songs are suffused with nostalgic,

agnostic sadness. They deal with three principal

themes: love, war, and the streets of Moscow. In

his treatment of love he is an unrepentant roman-

tic, idealizing women and portraying men as sub-

ordinate and flawed. In his treatment of war he is

anti-heroic, emphasizing fear, loss, and mankind’s

seeming inability to find a more humane way of

settling disputes. In his treatment of Moscow he

looks back to a time before the city became a So-

viet metropolis, when it offered refuge for the vul-

nerable and sensitive in its courtyards and

neighborhoods, especially the Arbat district. His

treatment of war and Moscow were particularly at

odds with official notions about these matters. At

about the time that Okudzhava created his basic

corpus of songs, the tape recorder became available

to private citizens in the USSR, and the songs were

duplicated in immense numbers, completely by-

passing official controls.

By the mid-1960s Okudzhava had become, af-

ter Vladimir Vysotsky, the most genuinely popu-

lar figure in the literary arts in Russia. He was

unique in that, while he remained a member of the

Party and the Union of Writers, his work was pub-

lished abroad (without permission) and circulated

unofficially in Russia, while continuing to be pub-

lished officially in the USSR. Shielded by his popu-

larity and his fundamental patriotism, he was

never subjected to severe repression. From the mid-

1980s until his death he was something of a Grand

Old Man of Russian literature, the doyen of the

“men of the 1960s.” In 1994, his novel The Closed

Theatre, a barely fictionalized account of his par-

ents’ life and fate through the eyes of their son,

won the Russian Booker Prize.

See also: JOURNALISM; MUSIC; UNION OF SOVIET WRITERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Smith, Gerald Stanton. (1984). Songs to Seven Strings:

Russian Guitar Poetry and Soviet “Mass Song.” Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

OKUDZHAVA, BULAT SHALOVICH

1101

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Makarov, Dmitriy; Vardenga, Maria; and Zubtsova,

Yana. (2003). “Boulat Shalvovich Okoudjava.” <http://

www.russia-in-us.com/Music/Artists/Okoudjava>.

G

ERALD

S

MITH

OLD BELIEVER COMMITTEE

In 1820, Emperor Alexander I convened a secret

committee to guide him in policies regarding the

Old Believers (also known as Old Ritualists or

raskolniki—schismatics). The secret committee in-

cluded some of the most important churchmen and

ministers in Russia, including the minister of reli-

gion and education (Prince Vasily Golitsyn) and

Archbishop Filaret Drozdov, later to become met-

ropolitan of Moscow and the preeminent prelate of

mid–nineteenth–century Russia. Originally given

the task of finding an appropriate form of tolera-

tion within the Russian legal system, the commit-

tee quickly broke into liberal and conservative

factions. Internal politics of the committee, added

to the emperor’s own vacillating desire for a “spir-

itual revolution” in Russia, weakened its ability to

make significant changes. Ascendance of conserv-

ative members pushed the committee’s views from

tolerance of the Old Belief to more stringent en-

forcement of punitive laws against them. After the

death of Emperor Alexander, the secret committee

became mostly a forum for discussion of anti-Old

Believer policies in the Russian government. It con-

tinued to exist into the reign of Alexander III, whose

landmark law of 1883 finally revised the legal sta-

tus of Old Believers in the Russian empire.

See also: ALEXANDER I; FILARET DROZDOV, METROPOLI-

TAN; OLD BELIEVERS; ORTHODOXY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nichols, Robert L. (2004). “The Old Belief under Surveil-

lance during the Reign of Alexander I.” In Russia’s

Dissenting Old Believers, ed. Georg Michels and Robert

L. Nichols. Minneapolis: Minnesota Mediterranenean

and East European Monographs.

R

OY

R. R

OBSON

OLD BELIEVERS

The term Old Believers (or Old Ritualists) includes

a number of groups that arose as a result of Rus-

sian church reforms initiated between 1654 and

1666. Old Believers desired to maintain the tradi-

tions, rites, and prerogatives of Russian Orthodoxy,

whereas Nikon, patriarch of the Russian Orthodox

Church, wanted to make Russian practices conform

to those of the contemporary Greek Orthodox

Church. Nikon’s opponents, conscious of both a de-

parture from tradition and an encroachment of

central control over local autonomy, refused to

change practices.

ORIGINS OF THE MOVEMENT

The reforms took two general forms—textual and

ritual. In the first, a group of editors changed all

Russian liturgical books to conform with their con-

temporary Greek counterparts, rather than old

Russian or old Greek versions. The most famous of

these was the change in spelling of “Jesus” from

“Isus” to “Iisus.” While the Old Believers rejected all

innovation, the symbolic centerpiece of resistance

was the sign of the cross. Traditionally, Russians

put together their thumb, fourth, and fifth fingers

in a symbol of the Trinity. The second finger was

held upright, to confirm Jesus’ form as perfect

man; the middle finger was bent to the level of the

second, symbolizing Jesus’ Godly form that bent

down to become human. These two fingers touched

the body during the sign of the cross, showing that

both natures of Jesus (human and divine) existed

on the cross. In Greek practice, the fingers were re-

versed—thumb, second, and third fingers were held

together and touched the body, while the fourth

and fifth fingers were held down toward the palm.

When Nikon obliged his flock to change their

hands, it seemed that he wanted them to discount

the icons in their churches and the instructions in

their psalm books, which explicitly showed the old

Russian style of the sign. In fact, the Stoglav Coun-

cil, convened exactly a century earlier, had con-

demned anything but the “two–fingered sign.”

The implementation of reforms were dracon-

ian. Ivan Neronov and Avvakum Petrovich, who

had been part of Nikon’s circle, challenged the pa-

triarch. Sometimes left alone, at other times perse-

cuted, Nikon’s opponents included some of the

most respected churchmen in Muscovy. In an un-

usual move, Neronov was finally allowed to con-

tinue using the old books for his services, but

Avvakum was exiled to Siberia and finally burned

at the stake for his extreme anti–reform posture.

Even women were not spared—the boyarina Feo-

dosia Morozova was carried out of Moscow to the

Borovsk Monastery, where she perished in jail.

OLD BELIEVER COMMITTEE

1102

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY