Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

For each of the famous anti–reformists, thou-

sands more pious Russians simply paid no heed to

the calls for reform and continued to pray accord-

ing to the old style. Their existence underlined the

limit of Nikon’s other goal, which was to limit the

expansion of central control of religious affairs to

the patriarch alone, taking away local prerogatives.

The vast majority of Old Believers simply refused

to accept either the reforms or the centralization

that Nikon imposed on his flock. The traditional-

ists, of course, perceived themselves as true Ortho-

dox, and called followers of the reformed ritual

“new believers” or “Nikonians.” Much of this early

history, however, is still poorly understood. Recent

scholarship has shown that the Old Belief did not

coalesce into a movement until perhaps a genera-

tion after the schism. Because local concerns tended

to override any broader organization of Old Be-

lievers, the leadership of the Old Belief probably had

only limited authority over a small core of sup-

porters.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

For the Old Believers, the possible loss of sacra-

mental life splintered the movement shortly after

the 1666 schism. Since no bishops consecrated new

hierarchs according to the old ritual, Old Believers

quickly found themselves bereft of canonical

clergy. Old Believer communities solidified into a

number of soglasiya, translatable as “concords.”

The differences among the concords lay not so

much in doctrinal issues as in sacramental proce-

dures and interaction with the state.

Old Believers developed a spectrum of views on

the sacraments. Half–Old Believers, for example, ac-

cepted some Russian Orthodox sacramental life but

prayed regularly only with other half–Old Believ-

ers. Many such half–Old Believers never openly

aligned themselves with any specific concord but

instead maintained a secret allegiance to the Old

Belief. Although scores of small, locally formed

groups sprang up, they tended to wither and die,

leaving few traces of their history.

The priestly Old Believers (popovtsy), on the

other hand, at some point in their history came to

accept clergy from new-rite sources. These priestly

Old Believers included the Belokrinitsy and the be-

glopopovtsy (fugitive-priestly), the latter accepting

clergy consecrated in the state-sponsored church.

Furthest from the church were the priestless Old

Ritualists—the Pomortsy, Fedoseyevtsy, Filippovtsy,

and Spasovtsy—all of whom firmly believed that

the sacramental life had been taken up into heaven,

just as Elijah had ridden his fiery chariot away from

a sinful world, only to return in the last days.

Priestless Old Believers were more likely to reject

accommodation with the state than their priestly

coreligionists, sometimes even eschewing the use of

money or building permanent homes. While some

Old Believers lived openly in their communities,

others traveled from place to place, preaching and

living off alms.

In broad terms, Old Believer communities on

the local level were organized according to similar

patterns, regardless of concord. Clergy (priests, pre-

ceptors, and abbots) usually came from within the

community or from one nearby, and all members

of the concord elected the group’s clerical leader-

ship. Democratic management of religious affairs

found precedent in both the autonomous organi-

zation of pre-Nikon parishes and in the monastic

rule maintained at the Solovki Monastery in Rus-

sia’s extreme north. This monastery, a dramatic

holdout against the Russian Orthodox church, saw

its continued expression in the Vyg and Leksa

monastic settlements that, in turn, established the

Pomortsy concord.

LEGAL AND SOCIAL STATUS IN

IMPERIAL RUSSIA

Reaction against Old Believers emanated from both

the Russian Orthodox Church and the secular state.

In pushing through his ritual and textual changes,

Patriarch Nikon relied heavily on his relationship

with Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich to suppress popular

opposition. The history of the Old Belief’s early

years tells of numerous confrontations between

agents of the state and Old Believers. At times, they

were subjected to corporal punishment such as

having a tongue cut out, being burnt at the stake,

or even being smoked alive “like bacon.” Some-

times, however, death came at the hands of Old Be-

lievers themselves. On some occasions, Old Believers

burned themselves alive in their churches rather

than accept the ritual changes of the revised Russ-

ian Orthodox Church. Although this was the most

extreme form of resistance and did not happen of-

ten, it did provide an effective and surprisingly fre-

quent deterrent to state seizure of Old Believer

groups. Self-immolation continued even into the

period of Peter I, a whole generation after the first

reforms.

Peter I’s position regarding the Old Believers

was mixed. Old Believers were not tolerated as po-

litical opponents of the state, especially of Peter’s

OLD BELIEVERS

1103

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

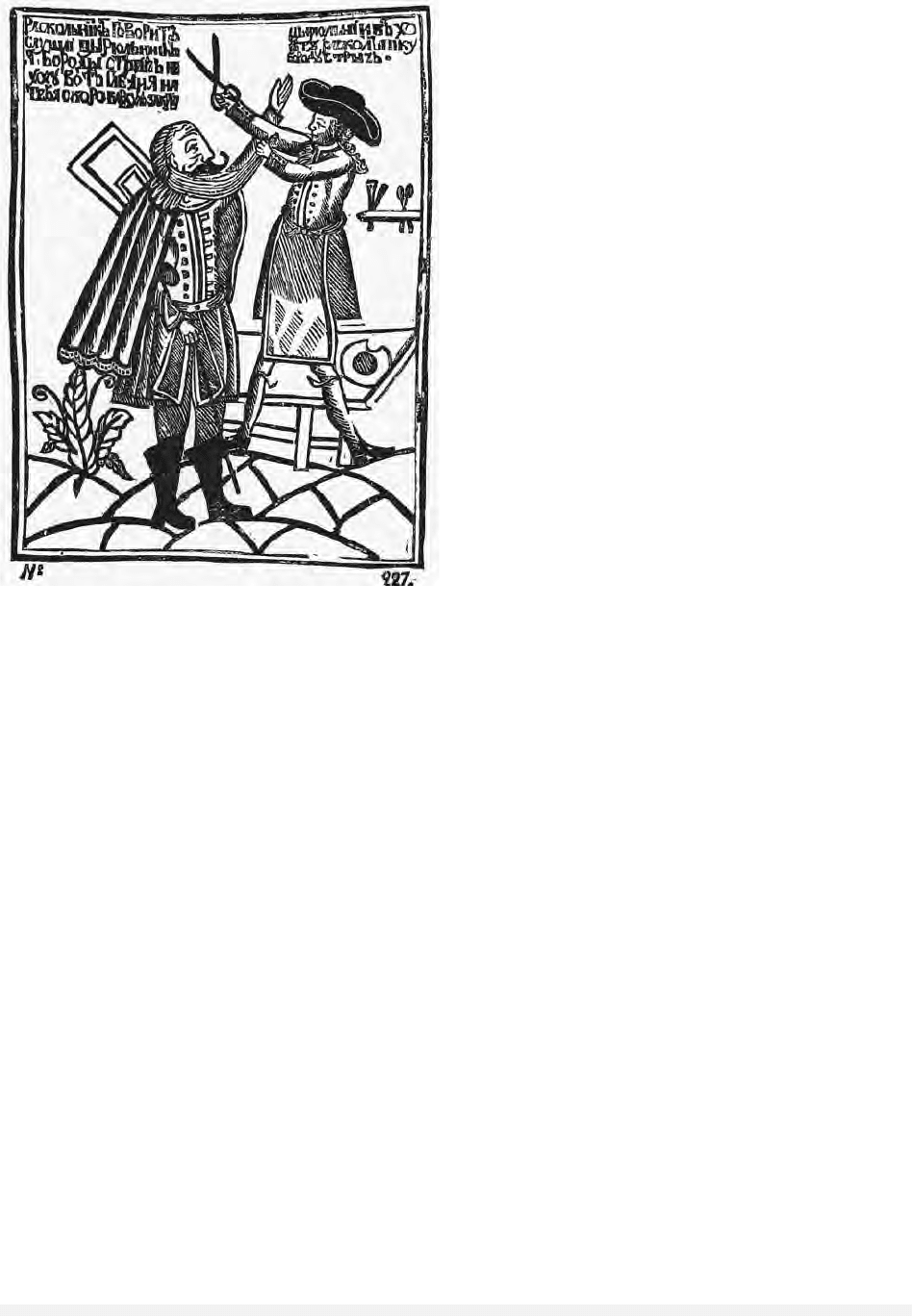

Woodcut ordered by Peter I to encourage men to shave their

beards and to ridicule Old Believers who refuse to shave.

© H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

Western-looking reforms. He implemented a dou-

ble poll tax on Old Believers and even imposed a

tax on the beards that Old Believers refused to

shave, as well as the traditional clothing that they

would not exchange for Western European dress.

In matters advantageous to the state, however, Pe-

ter I allowed Old Believers to live as they wished.

For example, he refused to persecute Old Believers

in the Vyg community while they were producing

ore.

Even when allowed to exist, Old Believers of-

ten suffered under separate laws and governmen-

tal decrees, some of which were secret and therefore

not published. The situation of the Old Believers

improved dramatically, however, during the reign

of Peter III, who tolerated them. During the rule of

Catherine II, the great Old Believer centers of Pre-

obrazhenskoe and Rogozhskoe were founded. In

these centers, curiously known only as “cemeter-

ies,” Old Believers created large complexes of

chapels, churches, bell towers, and charitable insti-

tutions, such as hospitals and almshouses. Pre-

obrazhenskoe and Rogozhskoe became the focus of

Old Believer merchant and industrial development

for succeeding generations.

Meanwhile, the church itself had softened its

attitude about the Old Ritual. In 1800, it created

the edinoverie, an arm of the official church that

continued to use the old rite. Although initially suc-

cessful, the edinoverie never swayed the majority

of priestly Old Believers, and even fewer of the

priestless Old Believers, who had become convinced

that priesthood would be lost until the Second

Coming of Christ.

With the succession of Nicholas I to the throne,

Old Believers once more found their legal status

eroded. Even by the end of Alexander’s reign, the

state had already begun again to refer to Old Be-

lievers as raskolniki (schismatics). This name had

earlier been dropped as too judgmental. As Nicholas

worked out a new relationship between church and

state, he began to close the Old Believers’ places of

worship, seize their property, and harrass the faith-

ful. By 1834, the gains made by Old Believers be-

fore 1822 had been completely lost.

The policy of the next tsar, Alexander II, to-

ward Old Believers proved much more liberal than

that of his father. Although laws from Tsar

Nicholas’s period curtailing Old Believer freedom

stayed on the books, the state generally stopped en-

forcing them. Old Believers again flourished both

in Moscow and in the far reaches of the empire.

The Russian Orthodox Church remained an

adamant opponent of the schism but began to pur-

sue expanded missionary activity to the Old Be-

lievers, rather than engage in direct persecution.

The succession of Alexander III further revised

the Old Believers legal status. Study of the Old Rit-

ualist question increased during the early years of

Alexander III’s administration and culminated in

the law on Old Believers of May 1883. This new

law served as the capstone to imperial policy on

the Old Belief until the revolutionary changes of

1905. At that time, against the wishes of the Rus-

sian Orthodox Church, the emperor granted full

toleration of all religious groups through his edict

of April 17, 1905. In the late imperial period, this

date would be celebrated by Old Believers as the be-

ginning of a silver age of growth and wide public

acceptance.

No one knows how many Old Believers lived

in Russia. The first census of the empire had con-

vinced Old Believers that to be counted was tanta-

mount to being enrolled in the books of Antichrist.

OLD BELIEVERS

1104

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Moreover, Old Believers realized that being counted

made them more easily subject to the double poll

tax. Thus, Old Believers rarely cooperated with im-

perial authorities during enumerations. The Old Be-

lievers could hide from the authorities simply by

calling themselves members of the Russian Ortho-

dox Church, especially if they had bribed the local

priest to enroll them on parish registers. The ques-

tion of numerical strength in relation to gender re-

mains sketchy at best. The figure of ten percent of

the total population, however, has been regarded

as authoritative for the imperial period.

Old Believers tended to live either in Moscow

or on the outskirts of European Russia. Often far

from imperial power, Old Believer communities

tended to include active roles for women and de-

vised self-help programs to insure economic sur-

vival. The wealth of Old Believer merchants and

industrialists has been noted many times, but even

the most modest Old Believer communities usually

made provisions for mutual aid, rendering their set-

tlements more prosperous-looking than other

Russian villages. Old Believer industrialists were

also widely reported to give preferential treatment,

good benefits, and high pay for co–religionists

working at their factories. Russian Orthodox au-

thorities even claimed that the Old Believers lured

poor adherents of the established church, including

impoverished pastors, into the arms of the schism.

OLD BELIEVERS IN THE SOVIET AND

POST–SOVIET PERIOD

The situation for Old Believers in post-1917 Rus-

sia has not been thoroughly studied, though some

generalizations can be made. In many cases,

churches were closed and their believers persecuted,

especially in the period of the cultural revolution.

Activists were jailed or sent to the Gulag camps, as

were many other religious believers. In other cases,

Old Believers followed a path of partial accommo-

dation with the state, much like the practices of

some Russian Orthodox. Taking advantage of So-

viet laws, some Old Believer communities used their

previous history of persecution and tradition of

communal organization to appeal for churches to

stay open. This strategy had mixed results. A few

major centers were allowed to exist in Moscow, for

example, and, after World War II, in Riga, but oth-

ers were closed or destroyed.

Old Belief was weakened significantly during

the communist period. Ritual life regularly became

covert, rather than public. After having been bap-

tized as children, Old Believers often ceased to take

part in church rituals as they grew older. Some,

especially in the urban centers, became Communist

Party members, perhaps to revive their religious life

in retirement. Older women, with little to lose po-

litically or economically, attended churches more

openly and frequently than working men and

women.

Many Old Believers, however, retreated into

their old practices of secrecy in worship, use of

homes instead of officially sanctioned churches,

and even flight into the wilderness. Rural Old Be-

lievers continued to be skeptical of outsiders, espe-

cially communists, and tried to retain ritual distance

between the faithful and the unbelievers. Some-

times, illegal or informal conferences debated the

problems of secular education, military service, and

intermarriage. In the most extreme cases, Old Be-

liever families moved ever farther into Siberia,

sometimes even crossing into China. Notably, Old

Believers also emigrated to Australia, Turkey, the

United States, and elsewhere, continuing a trend

that that had begun in the late nineteenth century.

The period of glasnost and perestroika created

significant international scholarly and popular in-

terest in the Old Believers, though that has waned

during the years of economic difficulty following

the breakup of the USSR. In post-communist Rus-

sia, Old Believers have become bolder and more pub-

lic, reviving publications, building churches, and

reconstituting community life. They have fought to

have the Old Belief recognized by the government as

one of Russia’s historical faiths, hoping to put the

Old Belief on par with the Russian Orthodox Church

as a pillar of traditional (i.e., noncommunist) val-

ues. Old Believers have continued to struggle with

the demands of tradition in a rapidly changing po-

litical, social, cultural, and economic environment.

See also: ALEXANDER MIKHAILOVICH; AVVAKUM PETRO-

VICH; CHURCH COUNCIL, HUNDRED CHAPTERS; NIKON,

PATRIARCH; OLD BELIEVER COMMITTEE; ORTHODOXY;

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cherniavsky, Michael. (1996). “The Old Believers and the

New Religion.” Slavic Review 25:1–39.

Crummey, Robert O. (1970). The Old Believers and the

World of Antichrist: The Vyg Community and the Rus-

sian State, 1694–1855. Madison: University of Wis-

consin Press.

Michels, Georg Bernhard. (1999). At War with the Church:

Religious Dissent in Seventeenth–Century Russia. Stan-

ford, CA: Stanford University Press.

OLD BELIEVERS

1105

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Peskov, Vasily. (1994). Lost in the Taiga: One Russian

Family’s Fifty-Year Struggle for Survival and Religious

Freedom in the Siberian Wilderness, tr. Marian

Schwartz. New York: Doubleday.

Robson, Roy R. (1995). Old Believers in Modern Russia.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Scheffel, David Z. (1991). In the Shadow of Antichrist: The

Old Believers of Alberta. Lewiston, NY: Broadview Press.

R

OY

R. R

OBSON

OLD STYLE

Until January 31, 1918, Russia used the Julian cal-

endar, while Western Europe had gradually changed

to the Gregorian calendar after its introduction by

Pope Gregory XIII in 1582. Orthodox Russia, asso-

ciating the Gregorian calendar with Catholicism,

had resisted the change. As a result, Russian dates

lagged behind contemporary events. In the nine-

teenth century, Russia was twelve days behind the

West; in the twentieth century it was thirteen days

behind. Because of the difference in calendars, the

revolution of October 25, 1917, was commemo-

rated on November 7. To minimize confusion, Russ-

ian writers would indicate their dating system by

adding the abbreviation “O.S.” (Old Style) or “N.S.”

(New Style) to their letters, documents, and diary

entries. The Russian Orthodox Church continues to

use the Julian system, making Russian Christmas

fall on January 7.

See also: CALENDAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gerhart, Genevra. (1974). The Russian’s World: Life and

Language. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the

Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

A

NN

E. R

OBERTSON

OLEG

(died c. 912), first grand prince of Kiev, asserted his

rule over the East Slavic tribes in the middle Dnieper

region and concluded treaties with Constantinople.

When Rurik was on his deathbed in 879 he

gave his kinsman Oleg “the Sage” control over his

domains in northern Russia and placed his young

son Igor into Oleg’s care. It is not known whether

Oleg succeeded Rurik in his own right or as the re-

gent for Igor. In 882 he assembled an army of

Varangians and East Slavs and traveled south from

Novgorod, capturing Smolensk and Lyubech. At

Kiev, he tricked the boyars Askold and Dir into

coming out to greet him. Accusing them of hav-

ing no right to rule the town because they were

not of princely stock as he and Igor were, he had

them killed. Oleg became the prince of Kiev and pro-

claimed that it would be “the mother of all Rus

towns.” He waged war against the neighbouring

East Slavic tribes, made them Kiev’s tributaries, and

deprived the Khazars of their jurisdiction over the

middle Dnieper. Oleg thus became the founder of

Rus, the state centered on Kiev.

In 907 Oleg attacked Constantinople. Although

some scholars question the authenticity of this in-

formation, most accept it as true. His army, con-

stituting Varangians and Slavs, failed to breach the

city walls but forced the Greeks to negotiate a

treaty. One of Oleg’s main objectives was to obtain

the best possible terms for Rus merchants trading

in Constantinople. He was thus the first prince to

formalize trade relations between the Rus and the

Greeks. In 911 (or 912) he sent envoys to Con-

stantinople to conclude another more juridical

treaty. The two agreements were among Oleg’s

greatest achievements. According to folk tradition,

he died in 912 after a viper bit him when he kicked

his dead horse’s skull. Another account says he died

in 922 at Staraya Ladoga.

See also: KIEVAN RUS; RURIKID DYNASTY; VIKINGS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Franklin, Simon, and Shepard, Jonathan. (1996). The

Emergence of Rus, 750–1200. London: Longman.

Vernadsky, George. (1948). Kievan Russia. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

OLGA

(d. 969), Kievan grand princess and regent for her

son Svyatoslav.

Under the year 903, the Primary Chronicle re-

ports that Oleg, Rurik’s kinsman and guardian to

his son Igor, obtained a wife for Igor from Pskov

by the name of Olga. It is unclear whether Igor was

OLD STYLE

1106

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

actually the son of Rurik, the semi-legendary

founder of the Kievan state, but, as Igor and Olga’s

son Svyatoslav was born in 942, it is very likely

that the chronology in the text is faulty and that

the marriage did not take place in 903. Legend has

it that Olga was of Slavic origin, but evidence is

again lacking.

On a trip to collect tribute from an East Slavic

tribe called the Derevlians (forest dwellers) in 945,

Igor was killed, and the Derevlians decided that Mal,

their prince, should marry Olga, who was serving

as regent for her minor son. Olga pretended to go

along with the plan, but then violently put down

their uprising by means of three well-planned acts

of revenge, after which she destroyed the Derevlian

capital Iskoresten. The chronicle account of Olga’s

revenge is formulaic, based on folklore-like riddles

that the opponent must comprehend in order to es-

cape death. The tales are clearly intended to demon-

strate Olga’s wisdom. From 945 to 947, after her

defeat of the Derevlians, Olga established adminis-

trative centers for taxation, which eliminated the

need for collecting tribute. During her regency she

significantly expanded the land holdings of the

Kievan grand princely house.

Olga was the first member of the Rus ruling

dynasty to accept Christianity. Scholars have de-

bated when and where she was converted, as the

sources give conflicting accounts, but there is some

evidence that she became a Christian in Constan-

tinople in 954 or 955 and was hosted by Con-

stantine Porphyrogenitus as a Christian ruler

during a subsequent visit in 957. According to the

Primary Chronicle account, which is likely intended

to mirror her rejection of Mal, Olga eludes a mar-

riage proposal from Constantine by resorting once

again to cunning, although this time her actions

are nonviolent and motivated by Christian chastity

rather than revenge.

Despite considerable effort, Olga was unable to

establish Christianity in Rus, and failed to secure

help to that end either from Byzantium or the

West. In 959 after her Byzantine efforts had yielded

no results, she requested a bishop and priest from

the German king, Otto I. Although a mission un-

der Bishop Adalbert was sent after much delay, it

was not well received and departed soon after-

wards. When her regency ended, Olga continued to

play an influential role, as Svyatoslav was fre-

quently away on military campaigns.

Olga died in 969 and was eventually canonized

by the Orthodox Church. The Primary Chronicle

does not report where she was buried, but Jakov

the Monk writes in his Memorial and Encomium to

Vladimir that her remains later lay in the Church

of the Holy Theotokos (built in 996) and that their

uncorrupted state indicated that God glorified her

body because she glorified Him. One of the most

enduring images associated with Olga is first en-

countered in the Sermon on Law and Grace (mid-

eleventh century) by Metropolitan Hilarion, but

repeated often in later works. In praising Olga and

Vladimir, Hilarion compares them to the first

Christian Roman emperor, Constantine, and his

mother Helen, who discovered the Holy Cross.

See also: KIEVAN RUS; PRIMARY CHRONICLE; RURIKID DY-

NASTY; SVYATOSLAV I; VLADIMIR, ST.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Franklin, Simon, and Shepard, Jonathan. (1996). The

Emergence of Rus, 750–1200. London: Longman.

Hollingsworth, Paul. (1992). The Hagiography of Kievan

Rus’. Cambridge, MA: Ukrainian Research Institute

of Harvard University.

Poppe, Andrzej. (1997). “The Christianization and Eccle-

siatical Structure of Kyivan Rus’ to 1300.” Harvard

Ukrainian Studies 21:311–392.

Cross, Samuel Hazzard, and Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd

P., ed and tr. (1953). The Russian Primary Chronicle:

Laurentian Text. Cambridge, MA: The Mediaeval

Academy of America.

D

AVID

K. P

RESTEL

OPERA

Opera reached Russia in 1731, when an Italian

troupe from Dresden visited Moscow. In 1736 it

was established at the tsarist court in St. Peters-

burg. Early Russian opera was mostly in Italian

and French. Works in Russian were usually set in

Russia, but representations of Russian history on

the operatic stage began only in 1790 with The

Early Reign of Oleg, a collaboration of the court com-

posers Vasily Pashkevich (a Russian), Carlo Canob-

bio, and Giuseppe Sarti (both Italians) on a Russian

libretto written by Catherine II.

The popularity of the court theaters in the early

nineteenth century made their stages a possible

venue of propaganda. This potential was fully re-

alized in Mikhail Glinka’s first opera (1836), with

a libretto written by Baron Rosen, secretary of the

OPERA

1107

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

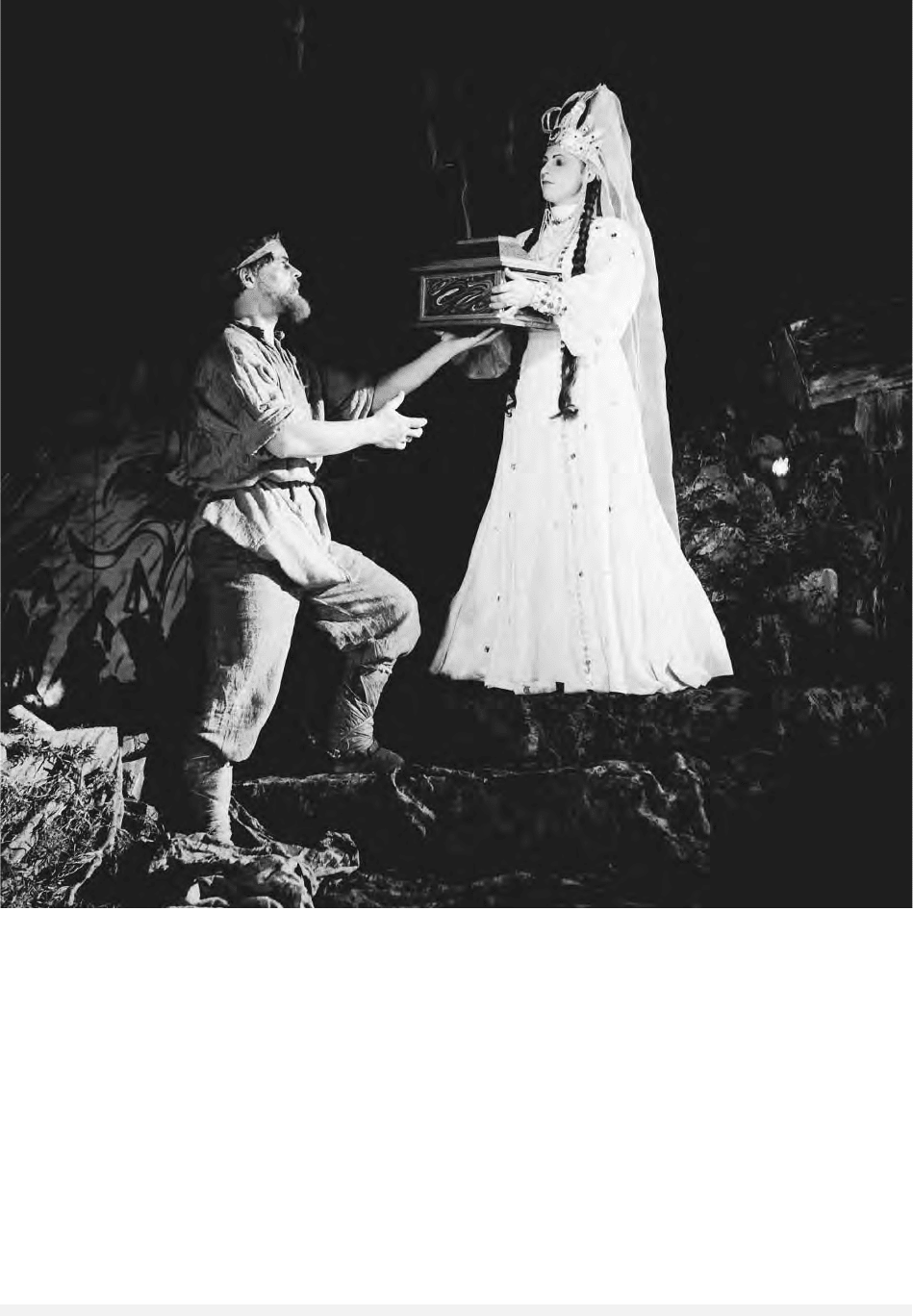

Soviet opera singers perform

Rock Flower

in 1950. © Y

EVGENY

K

HALDEI

/CORBIS

successor to the throne. Initially named for its pro-

tagonist, Ivan Susanin, the opera was renamed A

Life for the Tsar when Glinka dedicated it to Nicholas

I (Soviet legend had it that the new title was im-

posed against Glinka’s will). In its wholesale affir-

mation of the doctrine of “official nationality” as

proclaimed by Nicholas, the opera became a sym-

bol of Russian autocracy.

Opera was now the most popular form of en-

tertainment in Russia, but apart from Glinka there

were no notable domestic composers. To satisfy the

demand, a new Italian troupe was established in

St. Petersburg in 1843. Its repertory was the same

as that of other Italian enterprises abroad; except

for censorial changes to libretti, there was nothing

Russian about it. This artistic showcase, cherished

not only by the aristocracy but also by the radical

intelligentsia, slowed down the development of

Russian opera (and Russian music in general). Rus-

sian musicians, then mostly amateurs (composers

and performers alike), even suffered from legal dis-

OPERA

1108

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

crimination: Until 1860, “musician” was not a rec-

ognized profession; moreover, for a long time a

limit was imposed on the yearly income of Rus-

sians (but not of foreigners) in the performing arts,

and Russian composers were expressly forbidden to

write for the Italian company. Only after the es-

tablishment of conservatories in the 1860s did

Russian opera become really competitive; perfor-

mance standards rose, and gradually a Russian

repertory accumulated.

The first successful Russian opera after Glinka

was Alexander Serov’s Rogneda (1865). Its fictional

plot unfolds against the background of the “bap-

tism of Russia” in 988. As affirmative of the offi-

cial view on Russian history as A Life for the Tsar,

it earned its creator a lifelong pension from Alexan-

der II. Soon after, three composers from the

“Mighty Handful” embarked on operas based on

Russian history: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s The

Maid of Pskov (based on Ivan IV, after Lev Mey,

1873), Modest Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov (after

Alexander Pushkin’s play, 1874), and Alexander

Borodin’s Prince Igor (premiered posthumously,

1890). While Prince Igor affirmed autocracy, the

other two works did not; furthermore, their pro-

tagonists were Russian tsars, whose representation

on the operatic stage was forbidden. The ban was

partly lifted, which made the production of the two

operas possible. It remained in force for members

of the House of Romanov, however, and that is

why, in Musorgsky’s second historical opera, Kho-

vanshchina (unfinished; produced posthumously in

1886), the curtain falls before an announced ap-

pearance of Peter I; the same happens with Cather-

ine II in Peter Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades

(1891). The representation of Orthodox clergy was

also forbidden; while the Jesuits in Boris Godunov

presented no problem, the Orthodox monks had to

be recast as “hermits,” and a scene set in a monas-

tery was omitted. But before 1917 no Russian com-

poser ever withdrew an opera instead of complying

with the censor’s demands, nor did anyone try to

circumvent the censorship by having a banned

Russian opera performed abroad.

After the accession of Alexander III, the crown’s

monopoly of theaters was revoked (1882), and pri-

vate opera companies emerged; Savva Mamontov’s

in Moscow became the most famous. In 1885 the

Italian troupe was disbanded. Russian opera took

over its representative and social functions as well

as its repertory. While opera continued to be a fa-

vorite of the public, leading Russian composers

gradually lost interest in it, turning to ballet and

instrumental genres instead. Fairy-tale operas were

favored over depictions of Russian history, but

Rimsky-Korsakov’s last opera, The Golden Cockerel

(after Pushkin, Moscow 1909), is often seen as a

satire on Russian autocracy.

Censorship was restored after the 1917 revolu-

tion, although it took a different turn. A Life for the

Tsar was banned until revised as Ivan Susanin with

a new libretto by Sergei Gorodetsky (Moscow 1939).

Other pre-1917 operas underwent minor modifica-

tions. There were also new operas interpreting his-

tory in Soviet terms and even “topical” operas

intended to educate the public. Ivan Dzerzhinsky’s

“song opera” Quiet Flows the Don (Moscow 1934, af-

ter Mikhail Sholokhov’s novel) was held up as a

model against Dmitry Shostakovich’s anarchic Lady

Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1934; not based on

history, but in a realistic historical setting), which

was banned in 1936. Josef Stalin’s megalomania

shows through Sergei Prokofiev’s War and Peace (af-

ter Leo Tolstoy’s novel). Composed in response to

the German invasion of 1941, this most ambitious

of Soviet operas was revised several times and was

staged uncut only after the deaths of Stalin and

Prokofiev (Moscow 1959).

During the Stalinist era an effort was made to

establish national operatic traditions in the various

Soviet republics. Russian composers were sent to

the republics to collaborate with local composers

on operas based on local folklore (and sometimes

on local history) that generally sound like Rimsky-

Korsakov.

In the post-Stalinist decades, major composers

rarely tried their hand at opera. In the late 1980s

Alfred Schnittke wrote Life with an Idiot, a surre-

alist lampoon on Vladimir Lenin after a story by

Viktor Yerofeyev. It was premiered abroad (Ams-

terdam 1992), but in Russian and with a cast in-

cluding “People’s Artists of the USSR.” Since the fall

of the Soviet Union the musical has superseded

opera as the leading theatrical genre. It even serves

as a medium for patriotic representations of Rus-

sian history, such as Nord-Ost, the show staged in

Moscow whose performers and audience were

taken hostage by Chechen terrorists in 2002.

Outside Russia, Russian history has rarely

served as the subject matter for opera. The earliest

example is Johann Mattheson’s Boris Goudenow (sic,

Hamburg 1710), while the best-known is Albert

Lortzing’s Tsar and Carpenter (Leipzig 1837). Lortz-

ing’s comic opera exploits the sojourn of Peter I in

the Netherlands disguised as a carpenter’s appren-

OPERA

1109

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tice. Because of its depiction of a tsar from the Ro-

manov dynasty, it did not reach the Russian stage

until 1908.

See also: GLINKA, MIKHAIL IVANOVICH; MIGHTY HAND-

FUL; MUSIC; NATIONALISM IN THE ARTS; RIMSKY-

KORSAKOV, NIKOLAI ANDREYEVICH; TCHAIKOVSKY,

PETER ILYICH; THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buckler, Julie A. (2000). The Literary Lorgnette: Attending

Opera in Imperial Russia. Stanford, CA: Stanford Uni-

versity Press.

Campbell, Stuart, ed. (1994). Russians on Russian Music,

1830–1880: An Anthology. Cambridge, UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Campbell, Stuart, ed. (2003). Russians on Russian Music,

1880–1917: An Anthology. Cambridge, UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Morrison, Simon Alexander. (2002). Russian Opera and

the Symbolist Movement. Berkeley: University of Cal-

ifornia Press.

Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1992). The New Grove Dictionary of

Opera. London: Macmillan.

Taruskin, Richard. (1993). Opera and Drama in Russia: As

Preached and Practiced in the 1860s, 2nd ed. Rochester,

NY: University of Rochester Press.

Taruskin, Richard. (1997). Defining Russia Musically.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

A

LBRECHT

G

AUB

OPERATION BARBAROSSA

“Operation Barbarossa” was the name given by the

Germans to their invasion of the Soviet Union,

starting June 22, 1941. The operation was named

after the medieval Holy Roman emperor Frederick

Barbarossa, whom legend claimed would return to

restore Germany’s greatness.

In the last half of 1941 Germany and its allies

conquered the Baltic states, Belarus, almost all of

Ukraine, and western Russia. They surrounded

Leningrad and advanced to the gates of Moscow.

The Red Army lost millions of soldiers and thou-

sands of tanks and aircraft as it reeled back from

the German onslaught. Nevertheless the Soviet gov-

ernment was able to evacuate entire factories from

threatened areas to Siberia and Central Asia. It was

able to raise and arm new armies to face the Ger-

mans and finally halt their advance. Helped by

Germany’s ruthless policy in conquered Slavic ar-

eas, the Soviet government was able to rally the

population against the invader. By December 1941

the Red Army was able to mount a successful coun-

teroffensive against the overextended Germans.

The initial German attack in 1941 involved

three million troops and three thousand tanks but

nevertheless achieved strategic surprise, catching

the Soviet air force on the ground and most troops

far from their operational areas. In spite of the un-

mistakable signs of a military build-up along the

border, German reconnaissance flights over the

western Soviet Union, and warnings from sources

as diverse as communist spies and the British gov-

ernment, the Soviet government refused to mobi-

lize for war. It preferred to avoid any action that

might spark an accidental conflict, and this inac-

tion proved disastrous once the war began.

In the first months of the war German armored

spearheads sliced through the unprepared, disorga-

nized Red Army, encircling entire armies near

Minsk, Kiev, and Viazma. The German success

came at a great price, though. Casualties mounted,

and supply lines became more tenuous as they

lengthened. Soviet resistance stiffened as the Red

Army deployed new tanks (T-34 and KV-1) and

artillery (Katyusha rockets) that were technically

much better than their German counterparts. So-

viet reinforcements also poured in from the Far East

after the Soviet spy Richard Sorge reported that

Japan planned to move south against the United

States and Great Britain rather than attack Siberia.

A final factor in the USSR’s survival was the

weather. Optimistic German planners expected to

complete the conquest of Russia before the onset of

the autumn rains. The delay in the start of the in-

vasion due to the Balkans campaign, the unknown

depth of the Red Army’s reserves, and its unex-

pectedly strong resistance meant that the German

army faced winter in the field without suitable

clothing or equipment.

It also faced a Soviet population mobilized for

resistance. Soviet propaganda publicized German

atrocities against the civil population and lauded

the suicidal bravery of pilots who crashed their

planes into German bombers and of foot soldiers

who died blowing up enemy tanks. Restrictions

against the Orthodox Church were loosened, and

church leaders joined party leaders in defiantly call-

ing for a Holy War (the name of a popular song)

against the foe. While the Soviet Union suffered

enormous damage in 1941, it was not defeated.

OPERATION BARBAROSSA

1110

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: GERMANY, RELATIONS WITH; SORGE, RICHARD;

WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erickson, John. (1999). The Road to Stalingrad. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Glantz, David, and House, Jonathan. (1995). When Ti-

tans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler.

Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

A. D

ELANO

D

U

G

ARM

OPRICHNINA

Tsar Ivan IV’s personal domain between 1565 and

1572, and by extension the domestic policy of that

period.

The term oprichnina (from oprich, “separate”)

denoted a part of something, usually specific land-

holdings of a prince or a prince’s widow. Ivan IV

(the Terrible, or Grozny) established his Oprichnina

after he unexpectedly left Moscow in December

1564. He settled at Alexandrovskaya sloboda, a

hunting lodge northeast of Moscow, which became

the Oprichnina’s capital. Ivan IV accused his old

court of treason and demanded the right to punish

his enemies. He divided the territory of his realm,

his court, and the administration into two: the

Oprichnina under the tsar’s personal control; and

the Zemshchina (from zemlya, “land”), officially un-

der the rule of those boyars who stayed in Moscow.

The servitors were divided between the Zem-

shchina and the Oprichnina courts on the basis of

personal loyalty to the tsar, but the courts were

largely drawn from the same elite clans. The

Oprichnina court was headed by Alexei and

Fyodor Basmanov-Pleshcheev, Prince Afanasy

Vyazemsky, and the Caucasian Prince Mikhail

Cherkassky, brother-in-law of Ivan IV. They were

succeeded in around 1570 by the high-ranking cav-

alrymen Malyuta Skuratov-Belsky and Vasily

Gryaznoy. The Oprichnina army initially consisted

of one thousand men; later its numbers increased

five- to sixfold. Most of them came from the cen-

tral part of the country, although there were also

many non-Muscovites (Western mercenaries, Tatar

and Caucasian servitors) in the Oprichnina. Both

the leading Muscovite merchants (the Stroganovs)

and the English Muscovy Company also sought ad-

mission to the Oprichnina.

To maintain the Oprichnina army, the tsar in-

cluded in his domain prosperous peasant and ur-

ban communities in the north, household lands in

various parts of the country (mostly in its central

districts), mid-sized and small districts with nu-

merous conditional landholdings, and some quar-

ters of Moscow. The northern lands produced

revenues and marketable commodities (furs, salt),

the household lands provided the Oprichnina with

various supplies, and the regions with conditional

landholdings supplied servitors for the Oprichnina

army. The territory of the Oprichnina was never

stable, and eventually included sections of Nov-

gorod. The authorities deported non-Oprichnina

servitors from the Oprichnina lands and granted

their estates to the oprichniki (members of the

Oprichnina), but the extent of these forced reset-

tlements remains unclear.

The Oprichnina affected various local communi-

ties in different ways. The Zemshchina territories

bore the heavy financial burden of funding the or-

ganization and actions of the Oprichnina; some

Zemshchina communities were pillaged and devas-

tated. In early 1570, the tsar and his oprichniki

sacked Novgorod, where they slaughtered from three

thousand to fifteen thousand people. At the same

time, the lower-ranking inhabitants of Moscow es-

caped Ivan’s disgrace and forced resettlements. For

taxpayers in the remote north, the establishment of

the Oprichnina mostly meant a change of payee.

The tsar sought to maintain a close relation-

ship with the clergy by expanding the tax privi-

leges of important dioceses and monasteries and

including some of them in the Oprichnina. In ex-

change, he demanded that the metropolitan not in-

tervene in the Oprichnina and abolished the

metropolitan’s traditional right to intercede on be-

half of the disgraced. The Oprichnina’s victims in-

cluded Metropolitan Philip Kolychev, who openly

criticized the Oprichnina (deposed 1568, killed

1569) and Archbishop Pimen of Novgorod, the

tsar’s former close ally (deposed and exiled 1570).

The Oprichnina policy was a peculiar combi-

nation of bloody terror and acts of public reconcil-

iation. The social background of its victims ranged

from members of the royal family and prominent

courtiers, including some leaders of the Oprichnina

court, to rank-and-file servitors, townsmen, and

clergy. Indictments and repressions, however, were

often followed by amnesties. The mass exile of

around 180 princes and cavalrymen to Kazan and

the confiscation of their lands (1565) were coun-

terbalanced when they were pardoned and their

OPRICHNINA

1111

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

property partially restored. As a gesture of spiri-

tual reconciliation with the executed, the tsar or-

dered memorial services in monasteries for more

than three thousand victims. The Oprichnina in-

volved the ritualization of executions and peculiar

symbolism that alluded to the tsar and his oprich-

niki as punitive instruments of divine wrath. The

oprichniki dressed in black, acted like a pseudo-

monastic order, and carried dog’s heads and brooms

to show they were the “dogs” of the tsar who

would sweep treason from the land.

The tsar abolished the Oprichnina in 1572 af-

ter its troops proved ineffective during a raid of

Tatars on Moscow. Together with the Livonian

War, famines, and epidemics, the Oprichnina led to

the country’s economic decline. During the Oprich-

nina, Ivan IV thought to strengthen his personal

security by taking to extremes such Muscovite

political traditions as disgraces, persecution of sus-

pects, and forced resettlements. The Oprichnina re-

vealed the vulnerability of the social and legal

mechanisms for personal protection when con-

fronted by authorities exceeding the political sys-

tem’s normal level of violence. Transgressions and

sudden changes in policy contributed to the image

of the tsar as an autocratic ruler accountable only

to God. The court system, however, survived the

turmoil of the Oprichnina. Despite the division of

the realm and purges, members of established clans

maintained their positions in the court hierarchy

and participated in running the polity throughout

the period of the Oprichnina.

Some historians believe that the main force be-

hind the Oprichnina was Ivan IV’s personality,

including a possible mental disorder. Such inter-

pretations prevailed in the Romantic historical

writings of Nikolai Karamzin (early nineteenth cen-

tury) and in the works of Vasily Klyuchevsky,

foremost Russian historian of the early twentieth

century. The American historians Richard Hellie

and Robert Crummey offered psychoanalytical ex-

planations for the Oprichnina, surmising that Ivan

IV suffered from paranoia. Priscilla Hunt and An-

drei Yurganov saw the Oprichnina as an actual-

ization of the cultural myth of the divine nature

of the tsar’s power and eschatological expectations

in Muscovy. According to other historians, the

Oprichnina was a conscious struggle among cer-

tain social groups. In his classic nineteenth-century

Hegelian history of Russia, Sergei Solovyov inter-

preted the Oprichnina as a political conflict between

the tsar acting in the name of the state and the bo-

yars, who guarded their hereditary privileges. In

the late nineteenth century, Sergei Platonov took

those views further by arguing that the Oprich-

nina promoted service people of lower origin and

eliminated the hereditary landowning of the aris-

tocracy. In the mid-twentieth century, Platonov’s

conception was questioned by Stepan Veselovsky

and Vladimir Kobrin, who reexamined the ge-

nealogical background of the Oprichnina court and

the redistribution of land during the Oprichnina.

According to Alexander Zimin, the Oprichnina was

aimed at the main separatist forces in Muscovy:

the church, the appanage princes, and Novgorod.

Ruslan Skrynnikov accepted a modified multi-

phase version of Platonov’s views.

See also: AUTOCRACY; IVAN IV

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1987). “What Happened? How Did He

Get Away with It? Ivan Groznyi’s Paranoia and the

Problem of Institutional Restraints.” Russian History

14(1–4):199–224.

Hunt, Priscilla. (1993). “Ivan IV’s Personal Mythology

of Kingship.” Slavic Review 52:769–809.

Platonov, Sergei F. (1986). Ivan the Terrible, ed. and tr.

Joseph L. Wieczynski, with “In Search of Ivan the

Terrible,” by Richard Hellie. Gulf Breeze, FL: Acade-

mic International Press.

Skrynnikov, Ruslan G. (1981). Ivan the Terrible, ed. and

tr. Hugh F. Graham. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic In-

ternational Press.

Zimin, A. A. (2001). Oprichnina, 2nd ed. Moscow: Ter-

ritorriya.

S

ERGEI

B

OGATYREV

ORDIN-NASHCHOKIN, AFANASY

LAVRENTIEVICH

(c. 1605–1680), military officer, governor, diplo-

mat, boyar.

Afanasy Lavrentievich Ordin-Nashchokin was

born to a gentry family near Pskov in the first

quarter of the seventeenth century, probably around

1605. He received an unusually good education for

a Russian of the time, learning mathematics and

several languages, and entered military service at

fifteen. Exposed at a young age to foreign customs,

he put his insights and ideas to good use through-

out his life. In 1642 he helped settle a border dis-

pute with Sweden, honing his talents for careful

ORDIN-NASHCHOKIN, AFANASY LAVRENTIEVICH

1112

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY