Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

OSORINA, YULIANYA USTINOVNA

(d. 1604), noblewoman, local saint of Murom.

Yulianya Osorina is known through the Life [or

Tale] of Yulianya Lazarevskaya, a remarkable docu-

ment of the seventeenth century. Written by the

saint’s son Druzhina Osorin in the 1620s or 1630s,

it stands out among vitae (lives of saints) in that

it is tied to precise historical time and events. Most

striking is its subject: an ordinary laywoman, the

only Russian saint who was not a martyr, ruler,

or nun.

Yulianya was born into a family of the upper

ranks of the service nobility. Her father, Ustin

Nedyurev, was a cellarer of Ivan IV; her mother

was Stefanida Lukina from Murom. Orphaned at

the age of six, Yulianya was brought up by female

relatives and proved to be a serious, obedient, and

God-loving child. At the age of sixteen she was

married to the wealthy servitor Georgy Osorin. The

Life throws some light on the wide scope of duties

expected of a noblewoman of that time. Osorina’s

parents-in-law passed on to her the supervision of

all household affairs; in the frequent absence of her

husband she ran the estate and managed family af-

fairs: for instance, giving an adequate burial and

commemoration to her mother- and father-in-law.

The Life shows no trace of the alleged seclusion that

has been usually postulated for Muscovite women

of some status.

Yulianya began helping widows and orphans

in her youth and continued the commitment after

marriage. During her widowhood she intensified

the charity work, giving away all but the most

basic material necessities. Having donated all her

belongings in the years of the terrible famine

(1601–1603), she died in poverty on January 2,

1604.

The genre of the Life has been disputed widely.

In 1871 Vasily Osipovich Klyuchevsky was the

first to describe it as a secular biography. The So-

viet scholar Mikhail Osipovich Skripil shared this

view and chose for his 1948 edition the title Tale

of Ulianya Osorina, abolishing traditional headings

such as Life of Yulianya Lazarevskaya. On the other

hand, Western scholars T. A. Greenan and Julia

Alissandratos, as well as the Russian philolologist

T. R. Rudi, insist on the hagiographic character of

the work. Different signs of saintliness can be found

in the Life: For instance, when Yulianya died,

“everyone saw around her head a golden circle just

like the one that is painted around the heads of

saints on icons.” When in 1615 her son was buried

and her coffin opened, “they saw it was full of

sweet-smelling myrrh,” which turned out to be

healing. According to Greenan, the Life is firmly

rooted in Russian religious tradition, especially in

the popular fourteenth-century collection Iz-

maragd, which emphasizes the possibility of salva-

tion in the world, a central theme in the Life.

The Life was meant both to edify and to ad-

vance the cause of Yulianya. Though there is no

indication of an official sanctification, she has been

worshipped as a saint since the latter half of the

seventeenth century in and around the village of

Lazarevo, near Yulianya’s burial site in Murom.

She is commemorated on October 15 and January

2. Her relics are preserved in the Murom City Mu-

seum.

See also: HAGIOGRAPHY; RELIGION; SAINTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Greenan, T. A. (1982). “Iulianiya Lazarevskaya.” Oxford

Slavonic Papers 15:28–45.

Howlett, Jana, tr. (2002). “The Tale of Uliania Osor’ina.”

Available at <http://www.cus.cam.ac.uk/~jrh11/

uliania.html>.

N

ADA

B

OSKOVSKA

OSTARBEITER PROGRAM See WORLD WAR II.

OSTROMIR GOSPEL

The Ostromil Gospel is an eleventh-century Gospel

book, and the earliest dated Slavic manuscript.

According to its postscript, the Ostromir Gospel

was copied by the scribe Gregory for the governor

(posadnik) of Novgorod, Ostromir, in 1056 and 1057.

The manuscript contains 294 folios, and each folio

is divided into two columns. Gospels or evangeliaries

were books of Gospel readings arranged for use in

specific church services. In the Slavic tradition they

were called aprakos Gospel, which derives from the

Greek for “holy day.” Because of their important

function in the celebration of the liturgy, they were

very frequently copied. There are two types of evan-

geliaries. Short evangeliaries contain readings for all

days of the cycle from Palm Sunday until Pentecost

and for Saturday and Sunday for the remainder of

OSTROMIR GOSPEL

1123

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the year. Full evangeliaries have Saturday and Sun-

day readings for Lent as well as for all days of the

week for the rest of the year. The Ostromir Gospel

is the oldest of the short evangeliaries. It is notable

for its East Slavic dialect features, its remarkable

miniatures depicting three of the Gospel writers, and

its dignified uncial writing, which was often used in

copying biblical texts. Some scholars have main-

tained that the Ostromir Gospel goes back to an East

Bulgarian reworking of an earlier Macedonian

Glagolitic text, while others deny a Glagolitic con-

nection. The pioneering Russian philologist Alexan-

der. Vostokov produced an influential edition of the

Ostromir Gospel in 1843 (reprint 1964). Facsimile

editions were published in St. Petersburg/Leningrad

in 1883 and 1988. First preserved in the St. Sophia

cathedral in Novgorod and then in one of the Krem-

lin churches in Moscow, the Ostromir Gospel is now

located in the Russian National Library in St. Peters-

burg (formerly the State Public Library).

See also: KIEVAN RUS; RELIGION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Schenker, Alexander, M. (1995). The Dawn of Slavic: An

Introduction to Slavic Philology. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press.

D

AVID

K. P

RESTEL

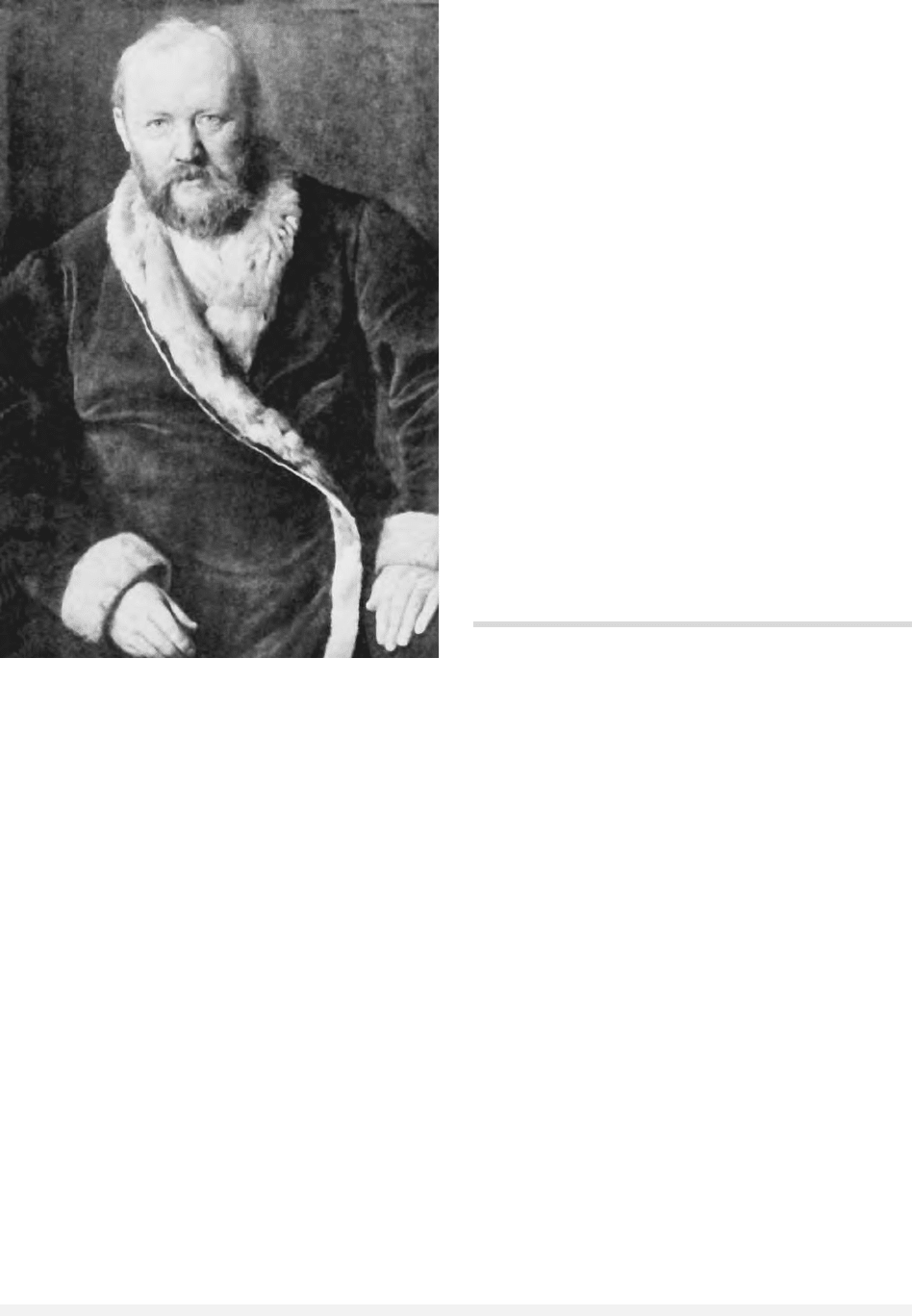

OSTROVSKY, ALEXANDER NIKOLAYEVICH

(1823–1886), playwright and advocate of drama-

tists’ rights.

Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky wrote and

coauthored some fifty plays, translated foreign

plays into Russian, and worked tirelessly to im-

prove conditions for actors, dramatists, and com-

posers. Half a dozen of his works form the core

repertory for the popular theater movement, a se-

ries of initiatives to advance enlightenment and

acculturation that steadily expanded theater pro-

duction and attendance in Russia from the 1860s

to World War I.

Young Ostrovsky studied languages, ancient

and modern, with tutors and his stepmother, a

Swedish baroness. While a student at Moscow Uni-

versity, he regularly attended performances at the

Maly Theater. A civil service position, as clerk in

the Commercial Court, acquainted him with the

subculture of the Russian merchantry in the “Over-

the-River” district south of the Kremlin in the

1840s. Merchants then seemed exotic to educated

Russians because, like the peasants, they had re-

sisted Westernization, maintained the patriarchal

family life and customs prevalent from the six-

teenth century, and held a strictly formal attitude

toward legality. Ostrovsky’s first published work,

revised as It’s a Family Affair—We’ll Settle It Our-

selves (1849) brought him to the attention of the

publisher of the journal The Muscovite, and he be-

came its editor in 1850. In his “Slavophile period”

Ostrovsky set out to explore with a circle of friends

what was good and unique about Russians. They

studied and sang folk songs and frequented tav-

erns, especially at festival times, to savor the witty

repartee between factory hands and performers.

Ostrovsky would go on to write historical plays

that let him exploit the pithy Russian of the six-

teenth and seventeenth centuries that predated the

language’s syntactical remodeling and massive bor-

rowing of foreign words. In this way, and by fo-

cusing on cultural enclaves that had survived into

the modern period, Ostrovsky mined the equivalent

of an Elizabethan linguistic vein for dramatic pur-

poses. A new regime in politics brought him an un-

paralleled opportunity to steep himself in the living

residue of Old Russian. After the Crimean War,

Alexander II’s Naval Ministry commissioned pro-

fessional writers to go to various river ports and

describe the local people and manners. Ostrovsky,

assigned a section of the Volga, traveled there in

1856 and 1857. He noted on index cards hundreds

of unfamiliar words and expressions with examples

of usage. As he traveled, he observed how the

steamship and other innovations were undercutting

ancient patterns of courtship and family organiza-

tion and overturning assumptions about the world.

His best-known play, The Storm (1859), which

drew on this experience, won the prestigious

Uvarov prize for literature. It shows the old ways—

at their harmonious best and despotic worst—

compromised by a transportation revolution that

was shrinking space and accelerating time, and ur-

banization that promoted civic life as a value while

redefining public and private space. Commercial

prosperity and a scientific outlook increasingly

sanctioned individual autonomy and rights.

From the beginning, Ostrovsky wrote in a re-

alist style, freely depicting the rude manners and

behavior observable in actual life. For a time this

caused censors to deny permission to perform his

plays. But as cultural nationalism advanced, his

OSTROVSKY, ALEXANDER NIKOLAYEVICH

1124

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Playwright Alexander Ostrovsky.

portrayal of strengths set in relief by flaws and

crudeness became irresistible. His true-to-life situ-

ations made his plays enormously accessible. He

seemed to define “Russianness” by showing indi-

viduals confronting concrete social and ethical

dilemmas as they moved beyond the traditional

culture, where custom dictated behavior.

In 1881 he drafted a proposal for a Russian na-

tional theater, which appealed to Alexander III’s

Great Russian chauvinism by arguing that the ex-

istence of a Russian school of painting and Rus-

sian music gave reason to hope for a Russian school

of dramatic art. He claimed that an already extant

body of Russian plays demonstrated the ability to

teach the “powerful but coarse peasant multitude

that there is good in the Russian person, that one

must look after and nurture it in oneself.”

When Ostrovsky died at Shchelykova, his

country estate located between the Volga towns of

Kostroma and Kineshma, he was at his desk trans-

lating one of Shakespeare’s plays into Russian. In

the Soviet period a community for retired actors

would be built on the property. His plays continue

to be performed in Russia to enthusiastic audiences.

The richness of their language and the deft incor-

poration of folk songs and dances in the works of

his Slavophile period ensure their survival, even as

the historical nuances of authority and status that

motivate much of the action recede from living

memory.

See also: SLAVOPHILES; THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hoover, Marjorie L. (1981). Alexander Ostrovsky. Boston:

Twayne Publishers.

Thurston, Gary. (1998). The Popular Theatre Movement in

Russia, 1862–1919. Evanston, IL: Northwestern Uni-

versity Press.

Wettlin, Margaret. (1974). “Alexander Ostrovsky and the

Russian Theatre before Stanislavsky.” In Alexander

Ostrovsky: Plays. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

G

ARY

T

HURSTON

OTREPEV, GRIGORY

(c. 1580–1606), Russian monk who supposedly be-

came the false Tsar Dmitry.

Yuri Bogdanovich Otrepev, the son of an in-

fantry officer, became the monk Grigory as a

teenager and eventually entered the prestigious

Miracles Monastery in the Moscow Kremlin. There

he became a deacon, and his intelligence and good

handwriting soon brought him to the attention

of Patriarch Job (head of the Russian Orthodox

Church), who employed Grigory as a secretary.

In 1602 a group of monks, including Grigory

and the future Tsar Dmitry, fled to Poland-

Lithuania. Their departure greatly upset Tsar Boris

Godunov and Patriarch Job. When one of the run-

aways identified himself as Dmitry of Uglich (the

youngest son of Tsar Ivan IV who supposedly died

as a child), the Godunov regime launched a propa-

ganda campaign identifying “False Dmitry” as

Grigory Otrepev. Stories were fabricated that Grig-

ory had become a sorcerer and tool of Satan or that

he had committed crimes while in the service of the

Romanov family (opponents of Tsar Boris). Al-

though no credible witnesses ever came forward to

verify that Grigory and “False Dmitry” were the

OTREPEV, GRIGORY

1125

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

same person, Tsar Dmitry’s enemies never tired of

claiming that he was really Otrepev.

The sensational image of the evil, debauched,

and bloodthirsty monk Grigory pretending to be

Tsar Dmitry continues to haunt modern scholar-

ship. Many historians have accepted at face value

the most lurid propaganda manufactured by

Dmitry’s enemies, but careful study of the evidence

reveals that it is impossible to merge the biogra-

phies of Grigory and “False Dmitry.” Grigory

Otrepev was last seen by an English merchant

shortly after the assassination of Tsar Dmitry in

1606; then he disappeared.

See also: DMITRY, FALSE; GODUNOV, BORIS FYODOR-

OVICH; TIME OF TROUBLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunning, Chester. (2001). Russia’s First Civil War: The

Time of Troubles and the Founding of the Romanov Dy-

nasty. University Park: Pennsylvania State Univer-

sity Press.

Perrie, Maureen. (1995). Pretenders and Popular Monar-

chism in Early Modern Russia: The False Tsars of the

Time of Troubles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

C

HESTER

D

UNNING

OUR HOME IS RUSSIA PARTY

Our Home Is Russia (Nash Dom—Rossiya, or NDR)

was a sociopolitical movement and a ruling party

from 1996 to 1998. Formed in the spring of 1995

according to a plan of the president’s administration

as one of two ruling parties—the party of the “right

hand,” with the prime minister at the head—it im-

mediately launched forward. The NDR movement’s

council, founded in May 1995 with Victor Cher-

nomyrdin at the head, included thirty-seven heads

of regions, a few ministers, and heads of large in-

dustrial enterprises and banks. The federal NDR

list for the Duma elections was headed by Cher-

nomyrdin, the famous film director Nikita Mikhal-

kov, and General Lev Rokhlin, a Chechnya war hero.

Subsequently both the prime minister and the film

director renounced the mandates, and Rokhlin, en-

tering the Duma, soon came into opposition against

Boris Yeltsin and he then left the NDR fraction; and

founded the Movement in Support of the Army. The

NDR list received seven million votes (10.1%, third

place) and forty-five Duma seats; this was taken as

defeat of the ruling party. In the single-mandate dis-

tricts, out of 108 proposed candidates, ten were

elected. In the 1996 presidential elections, NDR backed

Yeltsin.

With Chernomyrdin leaving the prime minis-

tership in the spring of 1998, NDR entered a period

of crisis. The effort on the part of the young ambi-

tious leader of the NDR fraction in the Duma,

Vladimir Ryzhkov, to turn NDR from a party of

heads into a neoconservative political party of “val-

ues” proved unsuccessful. Discussions of merging

with the blocs A Just Cause and Voice of Russia and

the movement New Force were fruitless as well. Al-

lies of NDR in the elections amounted to the weak

Forward, Russia of Boris Fyodorov and the Muslim

movement Medzhlis. The programmatic positions of

NDR amount to moderate-reformist ideas and a de-

claration of conservative-liberal values. The federal

list was headed by Chernomyrdin and the Saratov

governor Dmitry Ayatskov. NDR did not make it

into the Duma, as it received 0.8 million votes (1.2

percent). Nine NDR candidates from single-mandate

districts, including Chernomyrdin and Ryzhkov, en-

tered the pro-government fraction Unity and the

group People’s Deputy. In May 2000, the eighth and

last congress of NDR, which at the time had 125,000

members, decided to form part of the party Unity,

created on the foundation of the movements Unity,

All Russia, and NDR.

See also: CHERNOMYRDIN, VIKTOR STEPANOVICH; MOVE-

MENT IN SUPPORT OF THE ARMY; UNITY (MEDVED)

PARTY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

McFaul, Michael, and Markov, Sergei. (1993). The Trou-

bled Birth of Russian Democracy: Parties, Personalities,

and Programs. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism against Democ-

racry. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

N

IKOLAI

P

ETROV

OUR HOME IS RUSSIA PARTY

1126

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

PACIFIC FLEET

The Pacific Fleet is headquartered in Vladivostok,

capital of the Maritime (Primorsky) Territory. Not

surprisingly, given Russia’s status as a Pacific na-

tion with vital interests in the Asia-Pacific region,

the Pacific Fleet is one of Russia’s most powerful

naval forces. The city of Vladivostok, established in

1860, occupies most of Muraviev-Amursky Penin-

sula, named after the governor general of Eastern

Russia during the mid-nineteenth century. Two

bays, Amursky and Ussurysky, wrap the penin-

sula, mirroring with their names two great rivers

of the Russian Far East, the Amur, and the Ussury,

its tributary.

Beginning in the 1600s, Russian explorers first

reached Siberia’s eastern coastline and founded the

city of Okhotsk (1647). Until the mid-1800s, how-

ever, China’s dominance of the southern regions of

eastern Siberia restricted Russian naval activities.

The construction of the port city of Vladivostok in-

tensified Russia’s need for adequate transportation

links. Tsar Alexander III drew up plans for the

Trans-Siberian Railway and began building it in

1891. Despite the enormity of the project, a con-

tinuous route was completed in 1905, stimulated

by the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War a year

earlier. Vladivostok became Russia’s main naval

base in the east after Port Arthur (located in Chi-

nese territory and ceded to Russia in 1898) fell in

January 1905 during the war. After World War I,

Japan seized Vladivostok and held the key port for

four years, initially as a member of the Allied in-

terventionist forces that occupied parts of Russia

after the new Bolshevik government proclaimed

neutrality and withdrew from the war. At the end

of World War II, Stalin broke the neutrality pact

that had existed throughout the war in order to

occupy vast areas of East Asia formerly held by

Japan. It was through Vladivostok, moreover, that

some of the Lend-Lease aid, the most visible sign

of U.S.-Soviet cooperation during World War II,

passed on its way to Murmansk.

The Pacific Fleet includes eighteen nuclear sub-

marines that are operationally subordinate to the

Ministry of Defense and based at Pavlovsk and Ry-

bachy. The blue-water striking power of the Pacific

Fleet lies in thirty-four nonnuclear submarines and

forty-nine principal surface combatants. The Zvezda

Far Eastern Shipyard in Bolshoi Kamen, a couple of

hours north of Vladivostok, serves as the chief re-

cycling facility for the Fleet, although it is in dis-

repair. The Pacific Fleet’s additional home ports

P

1127

include Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Magadan, and

Sovetskaya Gavan. As far as air power is concerned,

the Pacific Fleet consisted during the mid-1990s of

250 land-based combat aircraft and helicopters.

Two bomber regiments stationed at Alekseyevka

constituted its most powerful strike force. Each

regiment consisted of thirty supersonic Tu-22M

Backfire aircraft. The land power of the Pacific Fleet

consisted of one naval infantry division and a

coastal defense division. The naval infantry divi-

sion included more than half of the total manpower

in the Russian naval infantry. During the mid-

1990s, the Pacific Fleet infantry was reorganized

into brigades.

During the late 1990s, a joint headquarters was

established commanding the land, naval, and air

units stationed on the Kamchatka Peninsula. De-

spite funding shortfalls during the early twenty-

first century, the Russian Pacific Fleet continues to

demonstrate its resolve to increase combat readi-

ness. Russian Pacific Fleet submarines carry out

missions of regional security, strategic deterrence,

protection of strategic assets, and training for anti-

surface warfare.

See also: BALTIC FLEET; BLACK SEA FLEET; MILITARY, IM-

PERIAL ERA; MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET;

NORTHERN FLEET; TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Busmann, Gerd, and Meier, Oliver. (1997). The Nuclear

Legacy of the Former Soviet Union: Implications for

Security and Ecology. Berlin: Berliner Information-

szentrum für Transatlantische Sicherheit (BITS) in

cooperation with Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.

Da Cunha, Derek. (1990). Soviet Naval Power in the Pa-

cific. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Morris, Eric. (1977). The Russian Navy: Myth and Real-

ity. New York: Stein and Day.

Stephan, John J. (1994). The Russian Far East: A History.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

PAGANISM

Due to the concerted efforts of both the eastern and

western churches, Christianity largely replaced

Slavic paganism during the course of the ninth and

tenth centuries. There are primarily three sources

for information about Slavic paganism: written

accounts, archaeological discoveries, and ethno-

graphic evidence. As literacy was introduced to the

East Slavs only with their conversion to Christian-

ity in 988

C

.

E

., and the written sources were most

often compiled by Christian monks or missionar-

ies, much of what is known about East Slavic pa-

ganism from written accounts is of questionable

accuracy. The sources begin with the Byzantine

historian Procopius (sixth century) and include

Arab travel accounts, reports of Christian mission-

ary activity, and references in the Primary Chroni-

cle and the First Novgorod Chronicle. Archaeological

evidence has provided some information on pagan

temples, particularly among the West Slavs on the

island of Rügen in the Baltic Sea. In addition, what

may have been a temple to Perun, god of thunder,

was excavated near Peryn, south of Novgorod in

1951, and several sites that were likely associated

with cult practices have been found at Pskov, in

the Smolensk region, and Belarus. Generally, how-

ever, archaeological sites are able to provide more

information about material culture than about the

spiritual life of a preliterate people. Ethnographic

material was not systematically collected until the

nineteenth century, which makes it difficult to sep-

arate genuine information from later accretions.

One can summarize, based on evidence from all

these sources, however, that early Slavic religion

was animistic, in that it personified natural ele-

ments. It also deified heavenly bodies and recog-

nized the existence of various spirits of the forest,

water, and household. Ritual sacrifice was likely

used to appease the pagan deities, and amulets were

used to ward off evil. In accordance with wide-

spread Indo-European practice, the early Slavs

likely cremated their dead, but even before the

Christian era burial was also practiced. Chernaya

Mogila, a burial site in Chernigov that dates from

the tenth century provides strong evidence for a be-

lief in the afterlife, as three members of a princely

family were interred with the horses, weapons, and

utensils that they would need for existence in the

next world.

Procopius makes reference to a Slavic god who

is the ruler of everything, but evidence for a larger

pantheon comes much later. The twelfth-century

Primary Chronicle relates how Prince Vladimir set

up idols in the hills of Kiev to Perun, “made of wood

with a head of silver and a mustache of gold,” as

well as to Khors, Dazhbog, Stribog, Simargl, and

Mokosh. In the entries for 907 and 971

C

.

E

., the

chronicle reports that the Rus swore by their gods

Perun and Volos, the god of the flocks. Perun is

PAGANISM

1128

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

associated with thunder and the oak tree, thought

to be a favorite target of the lightning bolts un-

leashed by the thunder god. Much less is known

about the other gods mentioned in the chronicle.

Khors seems to refer to the sun and, as Jakobson

points out, is closely connected with Dazhbog, the

“giver of wealth,” and Stribog, “the apportioner of

wealth.” Simargl appears to be a form of Simorg,

the Iranian winged monster, who is at times de-

picted as a winged dog. The only female in the pan-

theon is Mokosh, whose name is probably derived

from moist, and who is likely a personification of

Moist Mother Earth. Some scholars view Mokosh

as a remnant of the Great Goddess cult, which

struggled against the patriarchal religion of the

Varangians (Vikings). The god Volos, identified in

the peace treaties as the god of cattle, may be

connected with death and the underworld. The as-

sociation with cattle possibly comes from the ef-

forts of Christian writers to connect him with St.

Blasius, a martyred Cappadocian bishop who be-

came the protector of flocks. Although not listed

in Vladimir’s pantheon, the god Rod, with his con-

sort Rozhanitsa, is mentioned in other East Slavic

sources as a type of primordial progenitor.

After the conversion of Rus, elements of pa-

ganism continued in combination with Christian

beliefs, a phenomenon that has been called “dvoev-

erie” or “dual belief” in the Slavic tradition. Refer-

ences to pagan deities occasionally occur in Christian

era texts, most notably as rhetorical ornamenta-

tion in such works as the Slovo o polku Igoreve. Syn-

cretism is also apparent in the transformation of

Perun into the Old Testament Elijah, who was taken

to heaven in a fiery chariot.

See also: DVOEVERIE; KIEVAN RUS; OCCULTISM; VIKINGS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barford, Paul M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and So-

ciety in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

Gimbutas, Marija. (1971). The Slavs. London: Thames

and Hudson.

Hubbs, Joanna. (1989). Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth

in Russian Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press.

Jakobson, Roman. (1950) “Slavic Mythology.” Funk and

Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology

and Legend. Vol. 2. New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text. (1953).

Ed. and tr. Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P.

Sherbowitz-Wetzor. Cambridge, MA: The Mediaeval

Academy of America.

D

AVID

K. P

RESTEL

PAKISTAN, RELATIONS WITH

An affinity between Pakistan and the Soviet Union

would have seemed natural, given the Pakistan’s

status as a British colony (until 1947) and the

Soviet Union’s role as supporter of nations op-

pressed by capitalist imperialists. However, in 1959

Pakistan—along with Turkey and Iran—joined the

Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), which was

engineered by President Dwight Eisenhower’s ener-

getic secretary of state, John Foster Dulles. The se-

curity treaty replaced the Baghdad Pact and was

intended to provide a southern bulwark to Soviet

expansion toward the Indian Ocean and the oil

fields of the Persian Gulf. CENTO also enabled the

United States to aid Pakistan and cement a close se-

curity relationship with the country that has thus

become the cornerstone of U.S. policy in South Asia

for more than three decades. This relationship re-

inforced Moscow’s efforts to maintain close rela-

tions with Pakistan’s rival, India. Beginning in June

1955 with Indian prime minister Jawaharlal

Nehru’s visit to Moscow, and First Secretary Nikita

Khrushchev’s return trip to India during the fall of

1955, the foundations were laid for cordial Soviet-

Indian relations. While in India, Khrushchev an-

nounced Moscow’s support for Indian sovereignty

over the Kashmir region. Leading to the eventual

partition of British India in 1947, contention be-

tween Hindus and Muslims has focused on Kash-

mir for centuries. Pakistan asserts Kashmiris’ right

to self-determination through a plebiscite in accor-

dance with an earlier Indian pledge and a United

Nations resolution. This dispute triggered wars be-

tween the two countries, not only in 1947 but also

in 1965 (Moscow maintained neutrality in 1965).

In December 1971, Pakistan and India again went

to war, following a political crisis in what was then

East Pakistan and the flight of millions of Bengali

refugees to India. The two armies reached an im-

passe, but a decisive Indian victory in the east re-

sulted in the creation of Bangladesh.

New strains appeared both in Soviet-Pakistani

relations after the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghani-

stan. Pakistan supported the Afghan resistance,

while India implicitly supported Soviet occupation.

Pakistan accommodated an influx of refugees (more

PAKISTAN, RELATIONS WITH

1129

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

than 3.2 million people) resulting from the Soviet

occupation (December 1979–February 1989). In the

following eight years, the USSR and India voiced

increasing concern over Pakistani arms purchases,

U.S. military aid to Pakistan, and Pakistan’s nu-

clear weapons program. In May 1998 India, and

then Pakistan, conducted nuclear tests.

After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks,

Pakistan’s relations with Washington grew strained,

while its relations with Moscow improved. Al-

though Pakistan’s military ruler, General Pervez

Musharraf, agreed to provide the United States

with bases in Pakistan for launching military op-

erations against Pakistan’s erstwhile ally—the

Taliban—in Afghanistan, his actions fueled elec-

toral successes of Islamic fundamentalists in Pak-

istan who opposed his pro-U.S. stance. Meanwhile,

Russian President Vladimir Putin played a key me-

diation role in the Indo-Pakistani conflict. In Feb-

ruary 2003, Musharraf met with Putin in Moscow

to discuss trade and defense ties. This was the first

official state visit by a Pakistani leader to Moscow

since Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s. Pakistan and

India massed about a million troops along the UN-

drawn Line of Control that divides their sectors of

the state officially called Jammu and Kashmir—

raising international fears of a possible nuclear war.

See also: AFGHANISTAN, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hershberg, Eric, and Moore, Kevin W. (2002). Critical

Views of September 11: Analyses from Around the

World. New York: New Press.

Jones, Owen Bennett. (2002). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Weaver, Mary Anne. (2002). Pakistan: in the Shadow of

Jihad and Afghanistan. New York: Farrar, Straus and

Giroux.

Wirsing, Robert. (1994). India, Pakistan, and the Kashmir

Dispute: On Regional Conflict and Its Resolution. New

York: St. Martin’s Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

PALEKH PAINTING

Palekh painted lacquer boxes, popularly thought to

be a traditional Russian folk art, were actually a

product of the Soviet period. Palekh painting, a del-

icate and elegant miniature style, is done on the lids

of lacquered, papier-mâché black boxes with crim-

son interiors. The subjects depict Russian fairy tales,

legends, and folk heroes, and during the Soviet pe-

riod also included scenes of rural life, industrial-

ization, and Soviet leaders and heroes. Palekh boxes,

originally created for Soviet citizens, developed a

worldwide reputation after being sold at interna-

tional arts and crafts fairs.

The term palekh comes from the most famous

of the three villages (Kholui, Mstera, and Palekh) in

which Palekh painting originated. Ivan Golikov, a

Palekh icon painter, derived the inspiration for this

style from lacquered boxes he saw at the Kustar

Museum in 1921. Golikov and others applied egg

tempera, rather than oil, to papier-mâché boxes

and, employing techniques used in icon painting,

created objects that resembled traditional folk art.

The Artel of Early Painting, a craft collective for

Palekh painters founded by Golikov and his col-

leagues, was established in Palekh in 1924 (artels

also existed in Khuloi and Mstera). Palekh painting

became an integral part of Soviet applied arts with

the establishment of a four-year training program.

Exhibitions dedicated to Palekh boxes were held

throughout the 1930s. Academic articles on this

medium, and artistic debates discussing the appro-

priate style and content of Palekh painting, con-

tinued from the 1930s to the 1960s. Since the

1970s, Palekh painted boxes and brooches have

been viewed as the quintessential tourist souvenir

from Russia.

See also: FOLKLORE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hilton, Alison. (1995). Russian Folk Art. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press.

K. A

NDREA

R

USNOCK

PALE OF SETTLEMENT

As a result of the Napoleonic Wars and the acqui-

sition of the central and eastern provinces of Poland

by the Russian Empire during the late eighteenth

century, the area extending from the Baltic to the

Black Sea became known as the Russian “Pale of

Settlement.” Originally established by Catherine the

Great in 1791, the Pale (meaning “border”) even-

tually covered roughly 286,000 square miles

(740,700 square kilometers) of territory and grew

PALEKH PAINTING

1130

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

to include twenty-five provinces (fifteen Russian

and ten Polish), including Kiev, Grodno, Minsk,

Lublin, Bessarabia, and Mogilev. Along with the fa-

vorable acquisition of Polish land, the Russian gov-

ernment was faced with a population of ethnic

groups that came with the various territories. Al-

though the territories consisted of various groups,

including Byzantine Catholics, Germans, Armeni-

ans, Tartars, Scots, and Dutchmen, it was the large

number of Jews (10% of the Polish population) that

was most troubling to the tsars.

In 1804, intending to protect the Russian pop-

ulation from the Jewish people, Alexander I issued

a decree that prevented Jews from living outside the

territories of the Pale, the first of many statutes de-

signed to limit the freedoms of Russia’s new Jewry.

With more than five million Jews eventually living

and working within its borders, Russian lawmak-

ers used the confines of the Pale as an opportunity

to limit Jewish participation in most facets of so-

cial, economic, and political life. With few excep-

tions, Jews were forced to reside within the Pale’s

overcrowded cities and small towns called shtetls,

restricted from traveling, prevented from entering

various professions (including agriculture), levied

with extra taxation, forbidden to receive higher ed-

ucation, and kept from engaging in various forms

of trade to subsidize their livelihood. Although Jews

in the Pale were destined to a endure a life of poverty

and restriction, most managed to make their way

into the local economies by working as tailors, cob-

blers, peddlers, and small shopkeepers. Others, who

were less fortunate, survived only by committed

mutual aid efforts and strong local networks of

support.

As the Russian Empire started experiencing the

early stages of industrialization during the 1880s,

the Pale began to witness a steady decline in its

agricultural, artisanal, and petty entrepreneurial

economies. Because of this transition, many inde-

pendent producers of goods and services could no

longer subsist and were forced to find jobs in fac-

tories. Very few, especially the Jewish artisans and

tailors, were able to continue producing indepen-

dently or as middlemen to larger manufacturing

plants. By the start of the twentieth century, the

manufacturing sector was increasingly becoming

the primary source of employment in the Pale, with

wage laborers producing cigarettes, cigars, knit

goods, gloves, textiles, artificial flowers, buttons,

glass, bricks, soap, candy, and various other goods.

It was ultimately the deteriorating economy within

the Pale, coupled with years of anti-Semitism, that

served as catalyst for more than two million Jews

to emigrate to America between 1881 and 1914.

Not long after this exodus, the Pale of Settlement

was abolished with the overthrow of the tsarist

regime in 1917.

See also: ALEXANDER I; BESSARABIA; CATHERINE II; JEWS;

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Klier, John. (1986). Russia Gathers Her Jews: The Origins

of the “Jewish Question” in Russia, 1772–1825. DeKalb:

Northern Illinois University Press.

Ro’i, Yaacov, ed. (1995). Jews and Jewish Life in Russia

and the Soviet Union. Portland, OR: Frank Cass.

D

IANA

F

ISHER

PALEOLOGUE, SOPHIA

(d. 1503) niece of the last two Byzantine emperors

and the second wife of Grand Prince Ivan III of

Moscow.

Sophia Paleologue (Zoe) improved the Russian

Grand Prince’s international standing through her

dynastic status and promoted Byzantine symbol-

ism and ceremony at the Russian court.

Zoe Paleologue was the daughter of Despot

Thomas of Morea, the younger brother of the Byzan-

tine emperors John VIII and Constantine IX, and

Catherine, daughter of Prince Centurione Zaccaria

of Achaea. After the conquest of Morea by the Ot-

toman Turks in 1460 and her parents’ subsequent

death, Paleologue became a ward of the Uniate car-

dinal Bessarion, who gave her a Catholic education

in Rome as a dependent of Pope Sixtus IV.

After protracted negotiations with the Russian

Grand Prince, who saw an opportunity to increase

his prestige in a marital union with a Byzantine

princess, the Vatican offered Paleologue in a be-

trothal ceremony to one of Ivan III’s representa-

tives on June 1, 1472. During Paleologue’s trip to

Russia, the Byzantine princess assured the Russian

populace in Pskov of her Orthodox disposition by

abjuring Latin religious ritual and dress and by ven-

erating icons. Paleologue married Ivan III on No-

vember 12, 1472, in an Orthodox wedding ceremony

in the Moscow Kremlin and took the name Sophia.

Paleologue gave birth to ten children, one of

which was the future heir to the Russian throne,

PALEOLOGUE, SOPHIA

1131

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Basil III. The existence of Ivan Molodoy, the sur-

viving son of Ivan III’s union with his first wife,

Maria of Tver, and natural successor to the throne,

caused friction between the grand prince and Pale-

ologue. According to contemporary Russian chron-

icles, Paleologue intrigued against Ivan Molodoy

and his wife, Elena Voloshanka. Paleologue’s situ-

ation at court deteriorated even more after Volo-

shanka gave birth to a son, Dmitry Ivanovich. The

untimely death of Ivan Molodoy in 1490 inspired

rumors that Paleologue had poisoned him. The fo-

cus of Paleologue’s and Voloshanka’s dynastic

struggle shifted to Dmitry Ivanovich. Ivan III’s de-

cision to make Dmitry his heir in 1497 caused Pa-

leologue and her son Basil to revolt. Although Ivan

III disgraced Sophia and crowned Dmitry as his suc-

cessor in the following year, the Byzantine princess

emerged victorious in 1499, when Basil was made

Grand Prince of Novgorod and Pskov. Conspiring

with the Lithuanians, Paleologue put pressure on

her husband to imprison Voloshanka and her son

Dmitry and to proclaim Basil Grand Prince of

Vladimir and Moscow in 1502.

In pursuing her political and dynastic goals, Pa-

leologue exploited traditional Byzantine methods to

advertise her claims. In a liturgical tapestry she

donated to the Monastery of Saint Sergius of

Radonezh in 1498, she proclaimed her superior her-

itage by juxtaposing her position as Tsarevna of

Constantinople with the grand princely title of her

husband. By exploiting Byzantine religious sym-

bolism, in the same embroidery she expressed her

claim that Basil III was the divinely chosen heir to

the Russian throne. While there has been no sub-

stantiation for the claim of some scholars that Pa-

leologue was responsible for the introduction of

wide-ranging Byzantine ideas and practices at the

Russian court, the Byzantine princess’s knack for

political messages draped in religious language and

imagery undoubtedly left a lasting mark on me-

dieval Russian culture.

See also: BASIL III; IVAN III

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fennell, J. L. I. (1961). Ivan the Great of Moscow. London:

Macmillan.

Fine, John V. A., Jr. (1966). “The Muscovite Dynastic

Crisis of 1497–1502.” Canadian Slavonic Papers

8:198–215.

Kollmann, Nancy Shields. (1986). “Consensus Politics:

the Dynastic Crisis of the 1490s Reconsidered.” Rus-

sian Review 45(3):235–267.

Miller, David. (1993). “The Cult of Saint Sergius of

Radonezh and Its Political Uses.” Slavic Review 52(4):

680–699.

Thyrêt, Isolde. (2001). Between God and Tsar: Religious

Symbolism and the Royal Women of Muscovite Russia.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

I

SOLDE

T

HYRÊT

PALLAS, PETER-SIMON

(1741–1811), explorer, geologist, botanist.

Peter-Simon Pallas was born in Berlin, where

he received his formal education. He also spent

some time in Holland and England working in mu-

seums with rich collections in natural history. One

of his early studies dealing with polyps and sponges

was published in the Hague in 1761 and immedi-

ately attracted wide professional attention, not

only because of the richness and originality of the

presented empirical data, but also with its precisely

stated general theoretical propositions. In 1763

Pallas became a member of the St. Petersburg Acad-

emy of Sciences, and a year later he led an ex-

ploratory expedition to the Caspian and Baikal

areas, concentrating on both natural history and

ethnography. Published in three volumes between

1771 and 1778, under the title Travels through Var-

ious Provinces in the Russian Empire, and written in

German, the study was immediately translated into

Russian, and then into French, Italian, and English.

Pallas guided several other exploratory expeditions;

the trip to Southern Russia, with a heavy concen-

tration on Crimea, proved especially enlightening.

All these studies manifested not only Pallas’s ob-

servational talents but also his profound familiar-

ity with contemporary geology, botany, zoology,

mineralogy and linguistics. His Flora Rossica pro-

vided a systematic botanical survey of the coun-

try’s trees.

Pallas’s studies extended beyond the limits of

traditional natural history. He pondered the gen-

eral processes and laws related to geology: For ex-

ample, he presented a theory of the origin of

mountains in intraterrestrial explosions. He also

made a technically advanced study of regional vari-

ations in the Mongolian language, articulated a

transformist view of the living forms, which he

later abandoned, and, responding to a suggestion

made by Catherine II, worked on a comparative dic-

tionary. He also made a historical survey of land

tracts discovered by the Russians in the stretches

PALLAS, PETER-SIMON

1132

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY