Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

of ocean between Siberia and Alaska. In the jour-

nal of the Free Economic Society, established in the

age of Catherine II, he published a series of articles

on relations of geography to agriculture.

Most of Pallas’s studies offered no broad scien-

tific formulations; their strength was in the rich-

ness and novelty of descriptive information. Charles

Darwin referred to Pallas in four of his major

works, always with the intent of adding substance

to his generalizations. Georges Cuvier, by contrast,

credited Pallas with the creation of “a completely

new geology.” Pallas’s writings appealed to a wide

audience not only because, at the time of the En-

lightenment, there was a growing interest in the

geographies and cultures of the world previously

unexplored, but also because they were master-

works of lucid and spirited prose.

Together with the great mathematician Leon-

hard Euler, Pallas was a major contributor to the

elevation of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences

to the level of the leading European scientific insti-

tutions.

See also: ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Pallas, Peter-Simon. (1802–1803). Travels through the

Southern Provinces of the Russian Empire. 2 vols. Lon-

don: Longman and Kees.

Vucinich, Alexander. (1963). Science in Russian Culture.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

A

LEXANDER

V

UCINICH

PAMYAT

The Pamyat (Memory) society was established in

1978 to defend Russian cultural heritage. Pamyat

came to adopt extreme rightist platforms, particu-

larly under the direction of Dmitry Vasilyev from

late 1985. It rose to prominence as the most visi-

ble and controversial Russian nationalist organiza-

tion of the neformaly (informal) movement in the

USSR during the late 1980s. Although not represen-

tative of all strains of Russian nationalist thought,

Pamyat was representative of a broad xenophobic

ideology that gained strength in the perestroika

years.

At the heart of Pamyat’s platform was the de-

fense of Russian traditions. Pamyat ideologues de-

plored both Soviet-style socialism and western

democracy and capitalism. They held tsarist au-

tocracy as the ideal model of statehood. Much of

their ideology drew on the ideas of the Black Hun-

dreds, which organized pogroms against Jews in

Tsarist Russia. This reactionary ideology contained

a strong Orthodox Christian element. Alongside

provisions for the recognition of the place of Or-

thodoxy in Russian history, Pamyat made demands

for the priority of Russian citizens in all fields of

life.

In 1988 Pamyat had an estimated twenty thou-

sand members and forty branches in cities through-

out the Soviet Union. It later splintered into a

number of anti-Semitic and xenophobic groups.

Competing factions emerged, the two most promi-

nent being the Moscow-based National-Patriotic

Front Pamyat and the National-Patriotic Movement

Pamyat. This factional conflict belied an ideological

symmetry; both groups emphasized the impor-

tance of Russian Orthodoxy and blamed a Jewish-

Masonic conspiracy for everything from killing the

tsar to “alcoholizing” the Russian population. The

success of Pamyat’s xenophobic platforms sparked

debates about the negative consequences of glas-

nost and perestroika.

Factional disputes, crude national chauvinism

and contradictory political platforms led many

Russian nationalists to distance themselves from

Pamyat. Pamyat and its many splinter groups were

largely discredited and their influence much reduced

by the time the USSR collapsed in 1991. Neverthe-

less, it is widely recognized that Pamyat was a fore-

runner of post-Soviet Russian national chauvinist

and neo-fascist groups.

See also: NATIONALISM IN THE SOVIET UNION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Garrard, John. (1991). “A Pamyat Manifesto: Introduc-

tory Note and Translation.” Nationalities Papers 19

(2):135–145.

Laqueur, Walter. (1993). Black Hundred: The Rise of the

Extreme Right in Russia. New York: HarperCollins.

Z

OE

K

NOX

PANSLAVISM

Panslavism in a general sense refers to the belief in

a collective destiny for the various Slavic peoples—

PANSLAVISM

1133

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

generally, but far from always, under the leader-

ship of Russia, the largest Slavic group or nation.

Thus the seventeenth-century author of Politika

(Politics), Juraj Krizanic (1618–1683) is often re-

garded as a precursor of Panslavism because he

urged the unification of all Slavs under the leader-

ship of Russia and the Vatican. His writings were

largely unknown until the nineteenth century. The

Czech philologist Pavel Jozef Safarik (1795–1861)

and his friend, poet Jan Kollar, regarded the Slavs

historically as one nation. Safarik believed that they

had once had a common language. However, de-

spite his belief in Slavic unity, he turned against

Russia following the suppression of the Polish re-

bellion in 1830 and 1831. The Ukrainian national

bard, Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861), also hoped

for a federation of the Slavic peoples.

In a narrower and more common usage, how-

ever, Panslavicism refers to a political movement in

nineteenth-century Russia. Politically, Panslavism

would not have taken the shape it did without the

Russian claims of tutelage over the Slavic popula-

tions of the declining Ottoman Empire. Intellectu-

ally, however, Panslavism drew on the nationalist

ideas of people such as Mikhail Pogodin (1800–1875),

the most important representative of “Official

Nationality” and especially of the Slavophiles. Slavo-

philism focused critically on Russia’s internal civi-

lization and its need to return to first principles,

but it bequeathed to Panslavism the idea that Rus-

sia’s civilization was superior to that of all of its

European competitors. Of the early Slavophiles,

Alexei Khomyakov (1804–1860) wrote a number of

poems (“The Eagle”; “To Russia”), which can be con-

sidered broadly Panslav, as well as a “Letter to the

Serbs” in the last year of his life, in which he

demanded that religious faith be “raised to a

social principle.” Ivan Aksakov (1823–1886) actu-

ally evolved from his early Slavophilism to full-

blown Panslavism over the course of his journalis-

tic career.

The advent of Alexander II and the implemen-

tation of the so-called Great Reforms began the long

and complex process of opening up a public arena

and eventually a public opinion in Russia. Ideas

stopped being the privilege of a small number of

cultivated aristocrats, and the 1870s saw a reori-

entation from philosophical to more practical mat-

ters, if not precisely to politics, a shift that affected

both Slavophiles and Westernizers. It is against this

background that one needs to view the eclipse of

classical Slavophilism and the rise of Panslavism.

It is plausible to date the beginning of Panslav-

ism as a movement—albeit a very loose and undis-

ciplined one—to the winter of 1857–1858, when

the Moscow Slavic Benevolent Committee was cre-

ated to support the South Slavs against the Ot-

toman Empire. A number of Slavophiles were

involved, and the Emperor formally recognized the

organization, upon the active recommendation of

Alexander Gorchakov, Minister of Foreign Affairs.

In 1861 Pogodin became president and Ivan Ak-

sakov secretary and treasurer, and for the next fif-

teen years the Committee was active in education,

philanthropy, and a sometimes strident advocacy

journalism.

In 1867 the committee organized a remarkable

Panslav Congress, which went on for months. It

involved a series of lectures, an ethnographic exhi-

bition, and a number of banquets, speeches, and

other demonstrations of welcome to the eighty-one

foreign visitors from the Slavic world—teachers,

politicians, professors, priests, and even a few bish-

ops. But the discussions clearly demonstrated the

suspicions that many non-Russians entertained of

their somewhat overbearing big brother. No Poles

attended, nor did any Ukrainians from the Russian

Empire. Even to the friendly Serbs the Russian de-

mands for hegemony seemed excessive.

Panslav agitation was growing at the turn of

the decade, partly due to the bellicose Opinion on the

Eastern Question (1869) by General Rostislav An-

dreyevich Fadeev (1826–1884). In that same year

appeared a more interesting Panslav product, Rus-

sia and Europe, by Nikolai Yakovlevich Danilevsky

(1822–1885). It charted the maturation and decay

of civilizations and foresaw Russia’s Panslav Em-

pire triumphing over the declining West. The aims

of the Slavic Benevolent Committee seemed closest

to fulfillment during the victorious climax to the

Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, when Con-

stantinople appeared within the grasp of Russian

arms. Yet, despite the imperial patronage that the

Committee had enjoyed for over a decade, the gov-

ernment drew back from the seizure of Constan-

tinople, and then was forced by the European

powers at the Congress of Berlin (1878) to mini-

mize Russian gains. Aksakov’s subsequent tirade

about lost Russian honor resulted in the permanent

adjournment of the Committee. Panslav perspec-

tives lingered, but the movement declined into po-

litical insignificance during the course of the 1880s.

See also: NATIONALISM IN TSARIST EMPIRE; OFFICIAL NA-

TIONALITY; SLAVOPHILES

PANSLAVISM

1134

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fadner, Frank J. (1962). Seventy Years of Pan-Slavism in

Russia: Karazin to Danilevskii, 1800–1870. Washing-

ton, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Geyer, Dietrich. (1987). Russian Imperialism: The Interac-

tion of Domestic and Foreign Policy in Russia, 1860–1914.

New Haven: Yale University Press.

Greenfeld, Liah. (1992). Nationalism: Five Roads to Moder-

nity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kohn, Hans. (1953). Pan-Slavism: Its History and Ideol-

ogy. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame.

Petrovich, Michael Boro. (1956). The Emergence of Russ-

ian Panslavism 1865–1870. New York: Columbia

University Press.

Tuminez, Astrid. (2000). Russian Nationalism Since 1856.

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Walicki, Andrzej. (1975). The Slavophile Controversy: His-

tory of a Conservative Utopia in Nineteenth-Century

Russian Thought. Oxford: Clarendon.

A

BBOTT

G

LEASON

PARIS, CONGRESS AND TREATY OF 1856

Facing an empty treasury, a new French naval ord-

nance that might pierce the Kronstadt walls, and

possible Swedish and Prussian hostilities, Alexan-

der II and a special Imperial Council accepted an

Austrian ultimatum and agreed on January 16,

1856, to make peace on coalition terms and con-

clude the Crimean War. Even before Sevastopol fell

(September 12, 1855), Russia had accepted three of

the Anglo-French-Austrian Four Points of August

1854: guarantee of Ottoman sovereignty and ter-

ritorial integrity; general European (not exclusively

Russian) protection of the Ottoman Christians; and

freeing of the mouth of the Danube. The details of

the third point, as well as reduction of Russian

Black Sea preponderance and additional British par-

ticular conditions, completed the agreement. The

incipient entente with Napoleon III, who all along

had hoped to check Russian prestige without fight-

ing for British imperial interests, was a boon to

Russia.

Russia was ably represented in the Paris con-

gress (February 25–April 14) by the experienced ex-

traordinary ambassador and privy councillor

Count Alexei F. Orlov and the career diplomat and

envoy to London, Filip Brunov. They were joined

at the table by some of the key statesmen in the

diplomatic preliminaries of the war from Turkey,

England, France, and Austria, as well as Camilio

Cavour of Piedmont-Sardinia. Russia’s chief con-

cession was to remove its naval presence from the

Black Sea, but they worked out the details of its

neutralization directly with the Turks, not their

British allies. The affirmation of the 1841 Conven-

tion, which closed the Turkish Straits to warships

in peacetime, was actually more advantageous to

Russia, which lacked a fleet on one side, than to

Britain, which had one on the other. Russia’s sole

territorial loss was the retrocession of the south-

ern part of Bessarabia to Ottoman Moldavia, the

purpose of which was to secure the Russian with-

drawal from the Danubian Delta.

In addition, the Russians agreed to the demili-

tarization of the land Islands in the Baltic, a pro-

vision that held until World War I. The Holy

Places dispute, the diplomatic scrape which had led

directly to the war preliminaries, was settled on the

basis of the compromise effected in Istanbul in

April 1853 by the three extraordinary ambas-

sadors, Alexander Menshikov, Edmond de la Cour,

and Stratford (Canning) de Redcliffe, before Russia’s

diplomatic rupture with Turkey. The Peace Treaty

was signed on March 20, 1856.

The British at first did not treat the Russians

as complying and kept some forces in the Black Sea.

However, the 1857 India Mutiny, due in part to

Russian-supported Persian pressure on Afghanistan,

led to British withdrawal and facilitated the unim-

peded success of Russia’s long-standing campaign

to gain full control of the Caucasus.

As some contemporary observers noted, ad-

herence to the naval and strategic provisions of the

treaty depended upon Russian weakness and coali-

tion resolve. During the Franco-German war of

1870–1871, Alexander Gorchakov announced that

Russia would no longer adhere to the “Black Sea

Clauses” mandating demilitarization, and a London

conference accepted this change. During the Turk-

ish War of 1877–1878, Russia re-annexed South-

ern Bessarabia to the chagrin of its Romanian allies.

See also: CRIMEAN WAR; NICHOLAS I; SEVASTOPOL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baumgart, Winfried. (1981). The Peace of Paris, 1856:

Studies in War, Diplomacy, and Peacemaking. Santa

Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Mosse, Werner. (1963). The Rise and Fall of the Crimean

System, 1855-71: The Story of a Peace Settlement. Lon-

don: The English Universities Press.

D

AVID

M. G

OLDFRANK

PARIS, CONGRESS AND TREATY OF 1856

1135

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

PARIS, FIRST AND SECOND TREATIES OF

After the disastrous military campaigns of 1813

marked in particular by the severe defeat of Leipzig,

Napoleon’s political and military power was on the

decline. The emperor was unable to avoid the en-

try of the Allied powers in Paris on March 31, 1814,

and was forced to abdicate in April 1814. On May

30, 1814, following the restoration of Louis XVIII,

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, the plenipotentiary

of the new king, signed the first Treaty of Paris

with representatives of King George III of England;

of François I, emperor of Austria; of King Frederic-

William III of Prussia; and of Tsar Alexander I. This

treaty, which put an end to the war between France

and the Fourth Coalition and to the French hege-

mony in Europe, covered both territorial and geopo-

litical matters.

France retained its boundaries of January 1,

1792. Thus it was allowed to keep Avignon and

the Comtat-Venaissin, a large part of Savoy, Mont-

beliard, and Mulhouse, but had to surrender Bel-

gium and the left bank of Rhine as well as territories

annexed in Italy, Germany, Holland, and Switzer-

land. No indemnity was requested, and England

gave back all the French colonies except for Malta,

Tobago, St. Lucia in the Antilles, and the Isle of

France in the Indian Ocean. In addition, the Allied

powers had to withdraw from French territory.

Last, the treaty included secret clauses that ceded

the territory of Venetia to Austria and the port of

Genoa to the Kingdom of Sardinia.

On the political level, the treaty called for a gen-

eral congress to be held at Vienna to settle all ques-

tions about boundaries and sovereignty and to con-

firm the decisions taken by the Allied powers:

Switzerland was to be independent, Holland was to

be united under the House of Orange, Germany was

to become a federation of independent states, and

Italy was to be composed of sovereign states.

The relative leniency of the treaty was largely

due to the diplomatic ability of Talleyrand; yet, de-

spite its moderation, the document was badly re-

ceived by the French public opinion and it contributed

to the discredit of the Bourbons.

At the time the treaty was signed, Napoleon I

was prisoner on the island of Elba and separated

from his family. He escaped from the island and

landed on March 1, 1815, at Golfe Juan with nine

hundred faithful soldiers. He tried to take advan-

tage of his strong popularity to drive Louis XVIII

off the throne and restore his own personal power.

But that attempt lasted only one hundred days and

collapsed with the catastrophic defeat at Waterloo

on June 18, 1815. Napoleon had to abdicate again

and was sent to the island of Sainte-Hélène, where

he died on May 5, 1821.

Following this final abdication, a new treaty

was signed in Paris on November 20, 1815. It was

much tougher than the previous one; the cost of

the one hundred days was high. France was con-

fined to its former boundaries of 1790. It was au-

thorized to keep Avignon and the Comtat-Venaissin,

Montbéliard and Mulhouse, but lost the duchy of

Bouillon and the German fortresses of Philippeville

and Marienbourg given to the Netherlands, Sar-

relouis and Sarrebruck attributed to Prussia, Lan-

dau given to Bavaria, the area of Gex attached to

Switzerland, and a large part of Savoy given to the

king of Piedmont. Regarding the colonies, the loss

of Malta, St. Lucia, Tobago, and of the Isle of France

was confirmed. A financial cost was added to this

territorial cost: the French state had to pay an in-

demnity of 700 million francs and to undergo in

its northeast frontier areas a military occupation.

This occupation was limited to five years and

150,000 men but had to be paid by the French

budget.

Despite its severity, the second Treaty of Paris

was faithfully respected by King Louis XVIII; this

respect allowed France to get rid of the foreign oc-

cupation as early as 1818—two years earlier than

expected—and to play again at that date a signifi-

cant role in the international relations.

See also: ALEXANDER I; FRANCE, RELATIONS WITH;

NAPOLEAN I

M

ARIE

-P

IERRE

R

EY

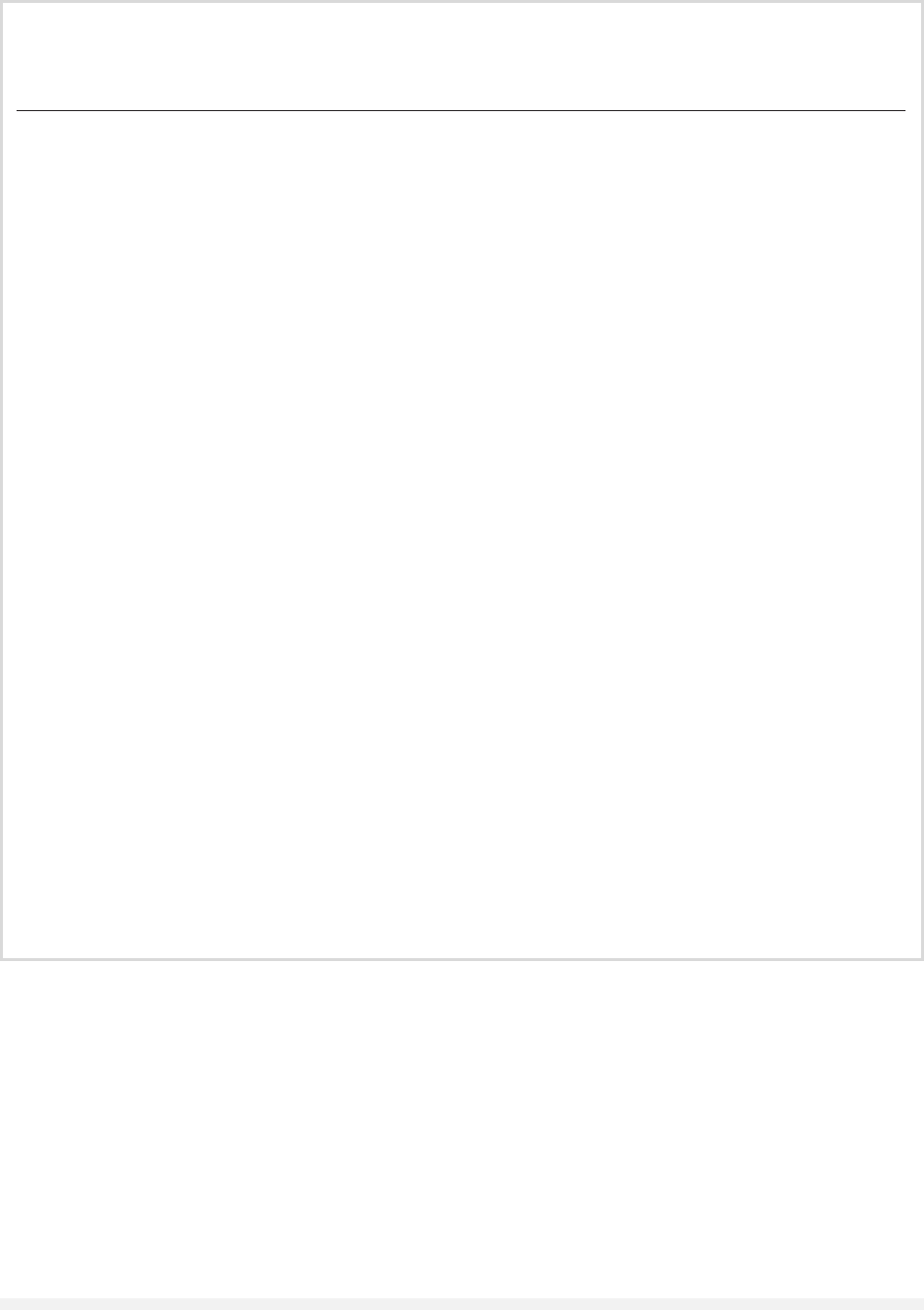

PARTY CONGRESSES AND CONFERENCES

Party congresses, the nominal policy-setting con-

claves of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,

were held at intervals ranging from one to five

years, and extended from the First, in 1898, to the

last, the Twenty-Eighth, in 1990. Made up since

the 1920s of two- to five thousand delegates from

the party’s local organizations, party congresses

were formally empowered to elect the Central Com-

mittee, to determine party rules, and to enact

resolutions that laid down the party’s basic pro-

grammatic guidelines. Party conferences, from the

PARIS, FIRST AND SECOND TREATIES OF

1136

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

first in 1905 to the nineteenth in 1988, were

smaller and less authoritative gatherings, usually

held midway in the interval between congresses.

Like the congresses, they issued policy declarations

in the form of resolutions, but did not conduct elec-

tions to the top party leadership.

Before the Revolution of 1917 and for the first

few years thereafter, party congresses and con-

ferences were marked by lively debate. The tran-

scripts of those proceedings, published at the time

and republished during the 1930s, are important

sources concerning the problems the country

faced and the viewpoints of the various party

leaders and factions. With the ascendancy of Josef

Stalin, however, party congresses and conferences

became creatures of the central party leadership. As

PARTY CONGRESSES AND CONFERENCES

1137

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Communist Party Congresses and Conferences

Delegates

Number Date Locale (Voting) (Non-voting)

1

st

Congress March 1898 Minsk 9

2

nd

Congress July 1903 Brussels and London 43 14

3

rd

Congress April 1905 London 24 14

1

st

Conference December 1905 Tammerfors 41

4

th

Congress April 1906 Stockholm 112 22

2

nd

Conference November 1906 Tammerfors 32 ca. 15

5

th

Congress May–June 1907 London 336

3

rd

Conference July (August) 1907 Kotka (Finland) 26

4

th

Conference November 1907 Helsingfors 27

5

th

Conference January 1909 Paris 16 2

6

th

Conference January 1912 Prague 12 4

“March Conference” March 1917 Petrograd ca. 120

7

th

Conference April 1917 Petrograd 133 18

6

th

Congress August 1917 Petrograd 157 110

7

th

Congress March 1918 Moscow 47 59

8

th

Congress March 1919 Moscow ca. 300 ?

8

th

Conference December 1919 45 73

9

th

Congress March 1920 554 162

9

th

Conference September 1920 116 125

10

th

Congress March 1921 ca. 700 ca. 300

10

th

Conference May 1921 ?

11

th

Conference December 1921 125 116

11

th

Congress March–April 1922 520 154

12

th

Conference August 1922 129 92

12

th

Congress April 1923 408 417

13

th

Conference January 1924 128 222

13

th

Congress May 1924 748 416

14

th

Conference April 1925 178 392

14

th

Congress December 1925 665 641

15

th

Conference

October–November 1925

194 640

15

th

Congress December 1927 898 771

16

th

Conference April 1929 254 679

16

th

Congress June–July 1930 1268 891

17

th

Conference January–February 1932 386 525

17

th

Congress January–February 1934 1225 736

18

th

Congress March 1939 1569 466

18

th

Conference February 1941 456 138

19

th

Congress October 1952 1192 167

20

th

Congress February 1956 1349 81

21

st

“Extraordinary” Congress January–February 1959 1269 106

22

nd

Congress October 1961 4408 405

23

rd

Congress March–April 1966 4620 323

24

th

Congress March–April 1971 4740 223

25

th

Congress February–March 1976 4998 non-voting

26

th

Congress February–March 1981 4994

27

th

Congress February–March 1986 ca. 5000

19

th

Conference June 1988 4976

28

th

Congress July 1990 4863

SOURCE: Courtes

y

of the author.

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

non-voting

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

Moscow

non-voting

non-voting

non-voting

Table 1.

described by the concept of the circular flow of

power, local officials who were de facto appointed

by the center handpicked their delegations to the

national congress, which in turn endorsed the

makeup of the Central Committee and the central

leadership itself, thus closing the circle.

PREREVOLUTIONARY PARTY

CONGRESSES AND CONFERENCES

The meeting that is traditionally considered the

First Party Congress was an ephemeral gathering

in Minsk in March 1898 of nine Marxist under-

grounders who managed to proclaim the estab-

lishment of the Russian Social Democratic Workers

Party (RSDWP) before they were arrested by the

tsarist police. Before the Revolution, there were four

more congresses and numerous conferences, dis-

tinguished by struggles between the Bolshevik and

Menshevik wings of the party that led up to their

ultimate split. The Second Party Congress, con-

vened in Brussels in July 1903 with fifty-seven

participants but forced to move its proceedings to

London under threat of arrest, was the first true

congress of the RSDWP. It saw the outbreak of the

Bolshevik-Menshevik schism when Vladimir Lenin

tried to impose his definition of party membership

as a core of professional revolutionaries rather than

the broad democratic constituency favored by the

Menshevik leader Yuly Martov.

The next congress, later counted by the Com-

munists as the Third, was an all-Bolshevik meet-

ing in London in April 1905, with just twenty-four

voting delegates plus invited guests. The First Party

Conference (as counted by the communists) was a

gathering in December 1905 of forty Bolsheviks

and a lone Menshevik in the city of Tammerfors

(Tampere) in Russian-ruled Finland. They endorsed

reunification with the Mensheviks and supported

boycotting the tsar’s new Duma (over Lenin’s ob-

jections). At this meeting, Stalin made his initial ap-

pearance at the national level and first met Lenin

face-to-face.

Following the abortive revolutionary events of

1905, the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks came to-

gether in Stockholm in April 1906 for the Fourth

Party Congress (by the Bolshevik enumeration),

styled the Unification Congress, with a Menshevik

majority among the 112 voting delegates. The two

factions met together again in London in April and

May 1907; this Fifth Party Congress was the last

embracing both wings, and the last before the Rev-

olution.

Small meetings later considered by the Bolshe-

viks as their Second through Fifth Party Confer-

ences were held between 1906 and 1909, mostly

in Finland, with Bolshevik, Menshevik, and other

Social-Democratic groups represented. These gath-

erings continued to revolve around the questions

of party unity and parliamentary tactics.

In 1912, going their separate ways, the Bol-

sheviks and Mensheviks held separate party con-

ferences. Twelve Bolsheviks plus four nonvoting

delegates (including Lenin) met in Prague in Janu-

ary of that year for what they counted as the Sixth

Party Conference. Excluding not only the Menshe-

viks but also the Left Bolsheviks denounced by

Lenin after the Fifth Party Conference in 1909, this

gathering established an organizational structure

of Lenin’s loyalists (including Grigory Zinoviev), to

whom Stalin was added soon afterwards as a co-

opted member of the Central Committee. The Sixth

Party Conference was the real beginning of the Bol-

shevik Party as an independent entity under Lenin’s

strict control.

FROM THE REVOLUTION

TO WORLD WAR II

Shortly after the fall of the tsarist regime in the

February Revolution of 1917 (March, New Style),

but before Lenin’s return to Russia, the Bolsheviks

convened an All-Russian Meeting of Party Work-

ers of some 120 delegates. Contrary to the stand

Lenin was shortly to take, this March Conference,

of which Stalin was one of the leaders, leaned to-

ward cooperation with the new Provisional Gov-

ernment and reunification with the Mensheviks.

For this reason, the March Conference was ex-

punged from official communist history and was

never counted in the numbering.

A few weeks later the Bolsheviks met more for-

mally in Petrograd, with 133 voting delegates and

eighteen nonvoting, for what was officially

recorded as the Seventh or April Party Conference.

On this occasion, by a bare majority, Lenin per-

suaded the party to reject the Provisional Govern-

ment and to oppose continued Russian participation

in World War I. Unlike postrevolutionary party

conferences, the Seventh elected a new Central

Committee, with nine members, including Lev

Kamenev and Yakov Sverdlov along with Lenin, Zi-

noviev, and Stalin.

The Sixth Party Congress, all-Bolshevik, with

157 voting delegates and 110 nonvoting, was held

in the Vyborg working-class district of Petrograd

PARTY CONGRESSES AND CONFERENCES

1138

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

in August 1917 under semi-clandestine conditions,

after the Provisional Government tried to suppress

the Bolsheviks following the abortive uprising of

the July Days. Lenin and other leaders were in hid-

ing or in jail at the time, and Stalin and Sverdlov

were in charge. The congress welcomed Leon Trot-

sky and other left-wing Mensheviks into the Bol-

shevik Party, and Trotsky was included in the

expanded Central Committee of twenty-one. How-

ever, the gathering could hardly keep up with

events; it made no plans directed toward the Bol-

shevik seizure of power that came soon afterwards.

Four congresses followed the Bolshevik takeover

in quick succession, all facing emergency circum-

stances of civil war and economic collapse. The Sev-

enth, dubbed “special,” was convened in Moscow

in March 1918, with only forty-seven voting del-

egates, to approve the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk end-

ing hostilities with Germany and its allies. Lenin

delivered a political report of the Central Commit-

tee, a function thereafter distinguishing the party’s

chief, while Nikolai Bukharin submitted a minor-

ity report for the Left Communists against the

treaty (a gesture last allowed in 1925). After bit-

ter debate between the Leninists and the Left, the

treaty was approved, and Russia left the war. How-

ever, Bukharin was included in the new Central

Committee of fifteen members. The Seventh Party

Congress also formally changed the party’s name

from Russian Social-Democratic Party (of Bolshe-

viks) to Russian Communist Party (of Bolsheviks).

All subsequent party congresses continued to be

held in Moscow.

The Eighth Party Congress met in March 1919

at the height of the civil war, with around three

hundred voting delegates. It adopted a new revo-

lutionary party program, approved the creation of

the Politburo, Orgburo, and Secretariat, and saw

its Leninist majority beat down opposition from the

Left, who opposed the trend toward top-down au-

thority in both military and political matters. The

first postrevolutionary party conference, the

Eighth, was held in Moscow (like all subsequent

ones) in December 1919. It updated the party’s

rules and heard continued complaints about cen-

tralism in government.

Three months later, at the Ninth Party Congress

in March 1920, Lenin and Trotsky and their sup-

porters again had to fight off the anti-centralizers

of the Left on both political and economic issues.

Such protest was carried much farther at the Ninth

Party Conference, which met in September 1920.

The “Group of Democratic Centralists” denounced

bureaucratic centralism and won a sweeping en-

dorsement of democracy and decentralism, unfor-

tunately undercut by their acquiescence with respect

to organizational efficiency and a new control com-

mission.

This spirit of reform was soon smothered at

the Tenth Party Congress, meeting in March 1921

with approximately seven hundred voting dele-

gates. After some three hundred of its participants

were dispatched to Petrograd to help suppress the

Kronstadt Revolt, the congress voted in several cru-

cial resolutions over the futile opposition of the

small left-wing minority. It condemned the “syn-

dicalist and anarchist deviation” of the Workers’

Opposition, banned organized factions within the

party in the name of unity, and supported the tax

in kind, Lenin’s first step in introducing the New

Economic Policy. The Central Committee was ex-

panded to twenty-five, but Trotsky’s key support-

ers were dropped from this body as well as from

the Politburo, Orgburo, and Secretariat.

Party congresses and conferences during the

1920s marked the transformation from a conten-

tious, policy-setting gathering to an orchestrated

phalanx of disciplined yes-men. This progression

took place as Stalin perfected the circular flow of

power through the party apparatus, guaranteeing

his control of congress and conference proceedings.

The Eleventh Party Congress, which met in March

and April 1922, was the last with Lenin’s parti-

cipation. It focused on consolidating party disci-

pline and strengthening the new Central Control

Commission to keep deviators in line. Immediately

after the Eleventh Party Congress, the Central Com-

mittee designated Stalin to fill the new office of Gen-

eral Secretary.

The Twelfth Party Congress took place in April

1923 during the interregnum between Lenin’s in-

capacitation in December 1922 and his death in

January 1924. Trotsky, Stalin, and Zinoviev were

all jockeying for advantage in the anticipated strug-

gle to succeed the party’s ailing leader. Debate re-

volved particularly around questions of industrial

development and policy toward the minority na-

tionalities, while Stalin maneuvered to cover up

Lenin’s break with him and pack the Central Com-

mittee (expanded from twenty-seven to forty) with

his own supporters.

The Tenth and Eleventh Party Conferences in

1921 and the Twelfth in 1922 were routine affairs,

but the Thirteenth proved to be a decisive milestone.

PARTY CONGRESSES AND CONFERENCES

1139

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

At this gathering just before Lenin’s death, the left

opposition faction supporting Trotsky was con-

demned as a petty-bourgeois deviation. Stalin

demonstrated his mastery of the circular flow of

power by allowing only three oppositionists among

the voting delegates.

By the time of the Thirteenth Party Congress

in May 1924, the Soviet political atmosphere had

changed even more. Lenin was dead; the triumvi-

rate of Stalin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev was trum-

peting the need for discipline and unity; and

opposition had been virtually outlawed. Stalin’s

party apparatus had ensured that among the 748

voting delegates there was not a single voice to rep-

resent the opposition, and Trotsky, merely one of

the 416 nonvoting delegates, temporarily recanted

his criticisms of the party. The Central Committee

was expanded again, to fifty-two, to make room

for even more Stalin loyalists, especially from the

regional apparatus.

The Fourteenth Party Conference, held in April

1925, endorsed Stalin’s theory of socialism in one

country and condemned Trotsky’s theory of per-

manent revolution. It marked the high point of the

New Economic Policy (NEP) by way of liberalizing

policy toward the peasants. However, this empha-

sis contributed to growing tension between the

Stalin-Bukharin group of party leaders and the

Zinoviev-Kamenev group.

At the Fourteenth Party Congress in December

1925 these two groups split openly. The so-called

Leningrad Opposition, led by Zinoviev and Kamenev

and backed by Lenin’s widow Nadezhda Krup-

skaya, rebelled against Stalin’s domination of the

party and took with them the sixty-two Leningrad

delegates. Kamenev openly challenged Stalin’s suit-

ability as party leader, but the opposition was

soundly defeated by the well-disciplined majority.

The NEP, especially as articulated by Bukharin,

was for the time being reaffirmed, although sub-

sequent Stalinist history represented the Four-

teenth Congress as the beginning of the new

industrialization drive. The Central Committee was

expanded again, to sixty-three.

Acrimony between the majority and the newly

allied Zinovievists and Trotskyists was even sharper

at the Fifteenth Party Conference of October–

November 1926. Kamenev now denounced Stalin’s

theory of socialism in one country as a falsification

of Lenin’s views. Nevertheless, the opposition was

unanimously condemned as a “Social-Democratic”

(i.e., Menshevik) deviation.

When the Fifteenth Party Congress met in De-

cember 1927, the left opposition leaders Trotsky,

Zinoviev, and Kamenev had been dropped from the

party’s leadership bodies, and Trotsky had been ex-

pelled from the party altogether. At the congress

itself, the opposition was condemned and its fol-

lowers were expelled from the party as well. At the

same time, the congress adopted resolutions on a

five-year plan and on the peasantry that subse-

quently served as legitimation for Stalin’s indus-

trialization and collectivization drives. Eight more

members were added to the Central Committee, not

counting replacements for the condemned opposi-

tionists, bringing the total to seventy-one (a figure

that held until 1952).

By the time of the Sixteenth Party Conference

in April 1929, the Soviet political scene had changed

sharply again. Stalin had defeated the Right Oppo-

sition led by Bukharin, government chairman

Alexei Rykov, and trade-union chief Mikhail Tom-

sky, and was initiating his five-year plans and

forced collectivization. The main task of the con-

ference was to legitimize the First Five-Year Plan

(already approved by the Central Committee),

backdating its inception to the beginning of the an-

nual economic plan that had already been in force

since October 1928. A new party purge, in the older

sense of weeding out undesirables from the mem-

bership, was also authorized by the conference.

The Sixteenth Party Congress, held in June and

July 1930, could hardly keep up with events.

Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky had been con-

demned and had recanted, although the congress

allowed them to keep their Central Committee seats

for the time being. The congress unanimously ac-

claimed the program of the Stalin Revolution in in-

dustry and agriculture. The industrialization theme

was echoed by the Seventeenth Party Conference of

January–February 1932; it approved the formula-

tion of the Second Five-Year Plan, to commence in

January 1933 (even though by that time the First

Five-Year Plan would have been formally in effect

for only three years and eight months).

When the Seventeenth Party Congress con-

vened in January–February 1934, collectivization

had been substantially accomplished despite the

catastrophic though unacknowledged famine in the

Ukraine and the southern regions of the Russian

Republic. Following the accelerated termination of

the First Five-Year Plan, the Second had begun. The

congress was dubbed “the Congress of Victors,”

while Stalin addressed the body to reject the phi-

losophy of egalitarianism and emphasize the au-

PARTY CONGRESSES AND CONFERENCES

1140

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

thority of individual managers and party leaders.

Yet there was surreptitious opposition over the

harshness of Stalin’s program, and behind-the-

scenes talk of replacing him with Leningrad party

secretary Sergei Kirov. In the end, nearly three hun-

dred delegates out of 1,225 voted against Stalin in

the slate of candidates for the Central Committee.

Stalin got his revenge in the purges of 1936

through 1938, when the party apparatus was dec-

imated and more than half of the people who had

been congress delegates in 1934 were arrested and

executed.

The Eighteenth Party Congress came only af-

ter a lapse of over five years, in March 1939. An

almost entirely new Central Committee was in-

stalled, Nikita Khrushchev achieved membership in

the Politburo, and the Third Five-Year Plan was be-

latedly approved. Stalin further revised Marxist ide-

ology by emphasizing the historical role of the state

and the new intelligentsia. A follow-up party con-

ference, the Eighteenth, was held in February 1941;

it endorsed measures of industrial discipline, but

was mainly significant for the emergence of Georgy

Malenkov into the top leadership. The institution

of the party conference then fell into abeyance, un-

til Mikhail Gorbachev revived it in 1988.

FROM WORLD WAR II TO THE

COLLAPSE OF COMMUNIST PARTY RULE

After the Eighteenth Party Congress, none was held

for thirteen years, during the time of war and post-

war recovery. When the Nineteenth Party Congress

finally convened in October 1952, the question of

succession to the aging Stalin was already im-

pending. Stalin implicitly anointed Malenkov as his

replacement by designating him to deliver the po-

litical report of the Central Committee. At the same

time, the party’s leading organs were overhauled:

the Politburo was renamed the Party Presidium,

with an expanded membership of twenty-five (in-

cluding Leonid Brezhnev), and the Orgburo was

dissolved. The congress also officially changed the

party’s name from All-Union Communist Party (of

Bolsheviks) to Communist Party of the Soviet

Union.

By the time of the Twentieth Party Congress,

convened in February 1956, Stalin was dead,

Khrushchev had prevailed in the contest to succeed

him, and the Thaw, the abatement of Stalinist ter-

ror, was underway. Nevertheless, Khrushchev pro-

ceeded to astound the party and ultimately the

world with his Secret Speech to the congress, de-

nouncing Stalin’s purges and the cult of personal-

ity. To this, he added a call, in his open report to

the congress, for peaceful coexistence with the

noncommunist world. The congress also estab-

lished a special bureau of the Central Committee

to superintend the business of the party in the

Russian Republic, which, unlike the other union re-

publics, had no distinct Communist Party organi-

zation of its own.

In January–February 1959 Khrushchev con-

vened the Extraordinary Twenty-First Party Con-

gress, mainly for the purpose of endorsing his new

seven-year economic plan in lieu of the suspended

Sixth Five-Year Plan. As an extraordinary assem-

bly, the congress did not conduct any elections to

renew the leadership.

At the Twenty-Second Party Congress of Oc-

tober 1961, with its numbers vastly increased to

4,408 voting and 405 nonvoting delegates, Khrush-

chev introduced more sensations. Along with re-

newed denunciation of the Anti-Party Group that

had tried to depose Khrushchev in 1957, and con-

demnation of the ideological errors of communist

China, the congress approved the removal of

Stalin’s body from the Lenin mausoleum on Red

Square. The congress also issued a new party pro-

gram, the first to be formally adopted since 1919,

with emphasis on Khrushchev’s notions of egali-

tarianism and of overtaking capitalism economi-

cally.

Four party congresses were held under Leonid

Brezhnev’s leadership, all routine affairs with little

change in the aging party leadership. The Twenty-

Third Party Congress in March–April 1966 empha-

sized political stabilization. It reversed Khrushchev’s

innovations by changing the name of the party pre-

sidium back to Politburo and by abolishing the

party bureau for the Russian Republic, but took no

new initiatives regarding either Stalinism or the

economy. The Twenty-Fourth Party Congress con-

vened in March–April 1971, a year later than orig-

inally planned; further economic growth was

stressed, but the issue of decentralist reforms was

straddled. The Twenty-Fifth Party Congress in

February–March 1976 was distinguished only by

more blatant glorification of General Secretary

Brezhnev, as the 4,998 delegates (no nonvoting

delegates from this time on) heard him stress

tighter administrative and ideological controls in

the service of further economic growth. Continu-

ity still marked the Twenty-Sixth Party Congress

in February–March 1981: Brezhnev was in his dotage

PARTY CONGRESSES AND CONFERENCES

1141

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and his entourage was dying off, and economic in-

efficiency and inertia, especially in agriculture, re-

mained at the center of attention. The years spanned

by the Twenty-Third through the Twenty-Sixth

Congresses were aptly known afterwards as the era

of stagnation.

With the Twenty-Seventh Party Congress, at-

tended by approximately five thousand delegates in

February–March 1986, the dissolution of the Com-

munist Party dictatorship in the Soviet Union

had begun. Gorbachev had taken over as General

Secretary after Brezhnev’s death and the brief ad-

ministrations of Yury Andropov and Konstantin

Chernenko, and had undertaken a sweeping reno-

vation of the aging leadership. At the congress it-

self, more than three-fourths of the delegates were

participating for the first time, and the new Cen-

tral Committee elected by the congress had more

new members than any since 1961. Gorbachev’s

main themes of socialist self-government and ac-

celeration in the economy were dutifully echoed by

the congress, without intimating the extent of

changes soon to come.

An even more significant meeting was Gor-

bachev’s convocation in June 1988 of the Nine-

teenth Party Conference, the first one since 1941,

and a far larger gathering than under the old prac-

tice, with 4,976 delegates. Faced with growing op-

position by conservatives in the party organization,

Gorbachev could not rely on the circular flow of

power, but had to campaign for the election of pro-

reform delegates—without much success. He had

hoped to give the conference the authority of a

party congress to shake up the Central Committee,

but had to defer this step. Nevertheless, as Gor-

bachev himself noted, debate at the conference was

more frank than anything heard since the 1920s.

The outcome was endorsement of sweeping con-

stitutional changes that shifted real power from the

party organization to the government, with a

strong president (Gorbachev himself) and the

elected Congress of People’s Deputies.

In July 1990, as Gorbachev’s reform program

was peaking, the Twenty-Eighth Party Congress

convened with 4,863 delegates. It proved to be the

last party congress before the collapse of Commu-

nist rule and the breakup of the Soviet Union. In

the freer political space allowed by Gorbachev’s

steps toward democratization, including surrender

of the party’s political monopoly, the party had

broken into factions: the conservatives led by Party

Second Secretary Yegor Ligachev, the radical re-

formers led by the deposed Moscow Party Secretary

Boris Yeltsin, and the center around Gorbachev. At

the congress, the conservatives submitted to Gor-

bachev in the spirit of party discipline, but Yeltsin

demonstratively walked out and quit the party.

Nonetheless, calling for a new civil society in place

of Stalinism, Gorbachev presided over the most

open, no-holds-barred debate since the communists

took power in 1917. He radically shook up the

Communist Party leadership, restaffed the Polit-

buro as a group of union republic leaders, and ter-

minated party control of governmental and

managerial appointments maintained under the old

“nomenklatura” system. For the first time, con-

gress resolutions were confined to the internal or-

ganizational business of the party, and steered clear

of national political issues. Barely more than a year

later, in August 1991, the conservatives’ attempted

coup d’état against Gorbachev discredited what was

left of Communist Party authority and set the stage

for the demise of the Soviet Union.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH; COM-

MUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION; FIVE-YEAR

PLANS; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH; KAMENEV,

LEV BORISOVICH; KHRUSHCHEV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH;

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; MENSHEVIKS; STALIN, JOSEF

VISSARIONOVICH; TROTSKY, LEON; ZINOVIEV, GRIG-

ORY YEVSEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Armstrong, John A. (1961). The Politics of Totalitarian-

ism: The Communist Party of the Soviet Union from

1934 to the Present. New York: Random House.

Brown, Archie. (1996). The Gorbachev Factor. Oxford: Ox-

ford University Press.

Current Soviet Policies: The Documentary Record of the Com-

munist Party, eds. Leo Gruliow et al. 11 vols. Colum-

bus, OH: Current Digest of the Soviet Press.

Dan, Fyodor. (1964). The Origins of Bolshevism. New

York: Harper and Row.

Daniels, Robert V. (1960, 1988). The Conscience of the Rev-

olution: Communist Opposition in Soviet Russia. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press, and Boulder,

CO: Westview.

Daniels, Robert V. (1966). “Stalin’s Rise to Dictatorship.”

In Politics in the Soviet Union: Seven Cases, eds. Alexan-

der Dallin and Alan F. Westin. New York: Harcourt,

Brace, and World.

Daniels, Robert V. (1993). The End of the Communist Rev-

olution. London: Routledge.

Keep, John H. L. (1963). The Rise of Social Democracy in

Russia. Oxford: Clarendon.

PARTY CONGRESSES AND CONFERENCES

1142

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY