Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Mawdsley, Evan, and White, Stephan. (2000). The Soviet

Elite from Lenin to Gorbachev: The Central Committee

and its Members, 1917–1991. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

McNeal, Robert H., ed. (1974). Resolutions and Decisions

of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. 4 vols.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Meissner, Boris. (1975). The Communist Party of the So-

viet Union: Party Leadership, Organization, and Ideol-

ogy. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Ponomaryov, Boris N., et al. (1960). History of the Com-

munist Party of the Soviet Union. Moscow: Foreign

Languages Publishing House.

Rigby, T. H. (1990). The Changing Soviet System: Mono-

Organizational Society from Its Origins to Gorbachev’s

Restructuring. Aldershot, UK: E. Elgar.

Schapiro, Leonard B. (1960). The Communist Party of the

Soviet Union. New York: Random House.

Schapiro, Leonard B. (1977). Origin of the Communist Au-

tocracy: Political Opposition in the Soviet State, First

Phase, 1917–1922, 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Stalin, Joseph V. (1947). Problems of Leninism. Moscow:

Foreign Languages Publishing House.

R

OBERT

V. D

ANIELS

PARTY OF RUSSIAN UNITY AND ACCORD

The Party of Russian Unity and Accord (Partiya

Rossiyskogo Yedinstva i Soglasiya, or PRES) was

founded for the 1993 elections as a regional vari-

ant of the ruling party. Its founder, a visible politi-

cian of the early Boris Yeltsin period, deputy prime

minister Sergei Shakhrai, was at the time the head

of the State Committee on Federal and Nationalist

Issues, whose apparatus was used in the provinces

as a base for party construction. Even the con-

stituent assembly of the PRES in October 1993 took

place not in Moscow but in Novgorod. The party

proclaimed as its goal the preservation of Russia’s

unity through securing equal rights of the subjects

of the Russian Federation. The PRES list at the

1993 elections was headed by Shakhrai; Alexander

Shokhin, deputy prime minister and an economist;

and Konstantin Zatulin, chair of the association En-

trepreneurs for a New Russia. Two federal minis-

ters were included on it as well: Yuri Kalmykov

and Gennady Melikian, and also the future public

figures Valery Kirpichnikov (minister of regional

politics in 1998–1999), Vladimir Tumanov (chair

of the Constitutional Court in 1995–1996), and

others. The list received 3.6 million votes (6.7%,

seventh place), mainly in the national republics, and

eighteen mandates; four PRES candidates in single-

mandate districts were elected. The PRES fraction

started out with thirty Duma delegates and ended

with twelve, due to disagreement over the Chech-

nya question as well as interfractional maneuver-

ing. During the 1995 campaign, PRES first joined

with Our Home Is Russia (NDR), but then made its

own list with Shakhrai at the head and registered

twenty-three candidates in the districts. However,

Shakhrai’s political stardom was already on the de-

cline, and when he left the State Committee on Fed-

eral and Nationalist Issues, he lost his base in the

provinces. The list received 246,000 votes (0.4%),

and in the majority districts only Shakhrai won,

joining with the group Russian Regions. In the

1999 elections, the PRES did not participate inde-

pendently. Shakhrai, joining with Yuri Luzhkov,

was included in the original version of the Father-

land—All Russia (OVR) list, but excluded at the

bloc’s congress. In May 2000 the PRES merged into

Unity when the latter was restructured from a

movement into a party.

See also: SHAKHRAI, SERGEI MIKHAILOVICH; UNITY

(MEDVED) PARTY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University.

McFaul, Michael, and Markov, Sergei. (1993). The Trou-

bled Birth of Russian Democracy: Parties, Personalities,

and Programs. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution

Press.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism Against Democ-

racy. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

N

IKOLAI

P

ETROV

PASSPORT SYSTEM

For the first time since the revolution, the Soviet

regime introduced an internal passport system in

December 1932. Most rural residents were not

given passports, and peasants acquired the auto-

matic right to a passport only during the 1970s.

The OGPU/NKVD (Soviet military intelligence ser-

vice and secret police), which administered the pass-

port system, initially issued these documents to

PASSPORT SYSTEM

1143

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

persons over sixteen years of age who lived in

towns, workers’ settlements, state farms, and con-

struction sites. They were required to obtain and

register their passport with the police, who would

then issue the necessary residence permit.

People who did not qualify for a passport were

evicted from their apartments and denied the right

to live and work within city limits. The categories

of people who were denied a passport and urban

residence permit included: the disenfranchised, ku-

laks or the dekulakized, all persons with a crimi-

nal record, persons not engaged in socially useful

work, and family members of the aforementioned

categories. The stated purpose of the new passport

system was to relieve the urban population of per-

sons not engaged in socially useful labor, as well

as hidden kulak, criminal, and other antisocietal el-

ements.

Some scholars note that the passport law

emerged in response to the massive urban migra-

tion that followed the 1932 famine. The resulting

movement of peasants from the countryside into

the cities strained the urban rationing and supply

systems. The selective distribution of passports of-

fered a solution to this crisis by restricting urban

residency and limiting access to city services and

goods. Other scholars emphasize that the passport

system was established to manage the urban pop-

ulation. Passports emerged as an instrument of re-

pression and police control. By issuing passports,

the state could more precisely identify, order, and

purge the urban population. Nonetheless, scholars

agree that the system of internal passports and ur-

ban residence permits sought to remove unreliable

elements from strategic cities, limit the flow of peo-

ple into these cities, and relieve the pressure on the

urban rationing and supply systems.

Passports categorized the Soviet population

into distinct groups with varying rights and priv-

ileges. The internal passport recorded citizens’ so-

cial position or class, occupation, nationality, age,

sex, and place of residence. The identity fixed on a

person’s passport determined where that individ-

ual could work, travel, and live. Only those with

certain social, ethnic, and occupational identities

were allowed residency in privileged cities, indus-

trial sites, and strategic border and military areas.

The passport also tied individuals to geographic ar-

eas and restricted their movements.

In the process of assigning passports, Soviet po-

lice removed dangerous, marginal, and anti-Soviet

elements from the major cities. Many people fled

the cities as passports were being introduced, fear-

ful that they would arrested by the police as so-

cially harmful elements. Passportization operations

were also used to purge the western borderlands

of Polish, German, Finnish, and other anti-Soviet

groups.

In the initial phases, the internal passport and

urban registration system often functioned in an

irregular and erratic manner. Many people cir-

cumvented the system by forging passports, and

others lived in towns without a valid passport.

See also: FAMINE OF 1932-1933; KULAKS; MIGRATION;

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexopoulos, Golfo. (1998). “Portrait of a Con Artist as

a Soviet Man.” Slavic Review 57:774–790.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1994). Stalin’s Peasants. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1999). Everyday Stalinism. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Kessler, Gijs. (2001). “The Passport System and State

Control over Population Flows in the Soviet Union,

1932–1940.” Cahiers du monde Russe 42:477–504.

G

OLFO

A

LEXOPOULOS

PASTERNAK, BORIS LEONIDOVICH

(1890–1960), poet, writer, translator.

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak was the most

prominent figure of his literary generation, a great

poet deeply connected with his age. His work un-

folded during a period of fundamental changes in

Russian cultural, social, and political history. It is

therefore no wonder that many of his works, and

most notably his novel, Doctor Zhivago, are imbued

with the spirit of history and relate its effect on the

lives, thoughts, and preoccupations of his contem-

poraries. In 1958 he was awarded the Nobel Prize

for his achievements in lyrical poetry and the great

Russian epic tradition.

Pasternak was born in Moscow into a highly

cultured Jewish family. His father, Leonid Paster-

nak, was a well-known impressionist painter and

professor at the Moscow School of Painting; his

mother was an accomplished pianist. During his

formative years, Pasternak studied music and phi-

losophy but abandoned them for literature. At the

PASTERNAK, BORIS LEONIDOVICH

1144

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

beginning of his literary career, he was associated

with the artistic avant-garde, and his modern sen-

sibility was strongly expressed in his first two vol-

umes of poetry, Twin in the Clouds (1914) and Above

the Barriers (1916), and in his early experiments in

fiction (1911–1913). Most of Pasternak’s works

written between 1911 and 1931 explore possibili-

ties far beyond realism and are characterized by

dazzling metaphorical imagery and complex syn-

tax reminiscent of Cubo-Futurist poetry, associated

especially with Vladimir Mayakovsky. Pasternak’s

cycle, My Sister-Life, published in 1922, is recog-

nized as his most outstanding poetic achievement.

Pasternak’s initial support of the Bolshevik

Revolution of 1917 vanished when the new regime

revealed its authoritarian and ruthless features.

Like many other Soviet writers during the 1920s,

Pasternak felt pressured by the authorities, who

were in the process of establishing control over lit-

erature, to portray the revolutionary age in epic

form. Despite his contempt for the party’s promo-

tion of the epic, and his disappointment over the

decline of lyrical poetry, Pasternak realized that, in

order to survive as a poet, he had to adjust to the

new cultural-political climate and try the epic

genre. During the course of the 1920s, therefore,

Pasternak wrote four epics: Sublime Malady (1924),

The Year Nineteen Five (1927), Lieutenant Schmidt

(1926), and Spektorsky (published in installments

between 1924 and 1930). There is a perceptible

stylistic and thematic difference between Paster-

nak’s previous works and his epic poems.

During the early 1930s, Pasternak was lifted

into the first rank of Soviet writers. He was the

only poet of his generation who was allowed to

publish. Osip Mandelstam was out of favor with

the government, Anna Akhmatova was not pub-

lishing, Mayakovsky and Sergei Yesenin commit-

ted suicide, and Marina Tsvetaeva was living

abroad. Pasternak was the sole poet whom the gov-

ernment was initially willing to tolerate. During

this period, he completed only one cycle of poetry,

Second Birth (1932), a book whose optimistic title

and tone Pasternak himself soon came to dislike as

a collection for which he had compromised his po-

etic standards, and in which he had simplified the

language for the sake of a mass readership.

Starting in 1932, the Central Committee of the

Communist Party abolished all literary schools and

associations and moved decisively toward consoli-

dating its control over all writers’ activities and

their artistic production. In 1934 the Party estab-

lished the Union of Soviet Writers and implemented

the official new artistic method of “socialist real-

ism” that demanded from the artist “truthfulness”

and “an historically concrete portrayal of reality in

its revolutionary development.” Writers were now

treated as builders of a new life and “engineers of

human souls.” Pasternak’s modernist autobiogra-

phy Safe Conduct was banned in 1933 and not pub-

lished again until the 1980s.

The most oppressive period in Soviet history

began in 1936, and a reign of terror marked the

next few years. Many of Pasternak’s friends be-

came victims of the Great Terror. The poet himself

fell from grace and survived by mere chance. He

nearly abandoned creative writing, devoting him-

self almost exclusively to translations. While this

relieved him from the pressure of having to write

pro-Stalinist poetry during the worst years of the

Great Terror, it also pushed him into an increas-

ingly peripheral position. Translating became a

means of material survival for him during the

darkest years of Soviet history, and his translations

from this period alone would assure Pasternak a

notable place in the history of Russian literature.

PASTERNAK, BORIS LEONIDOVICH

1145

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

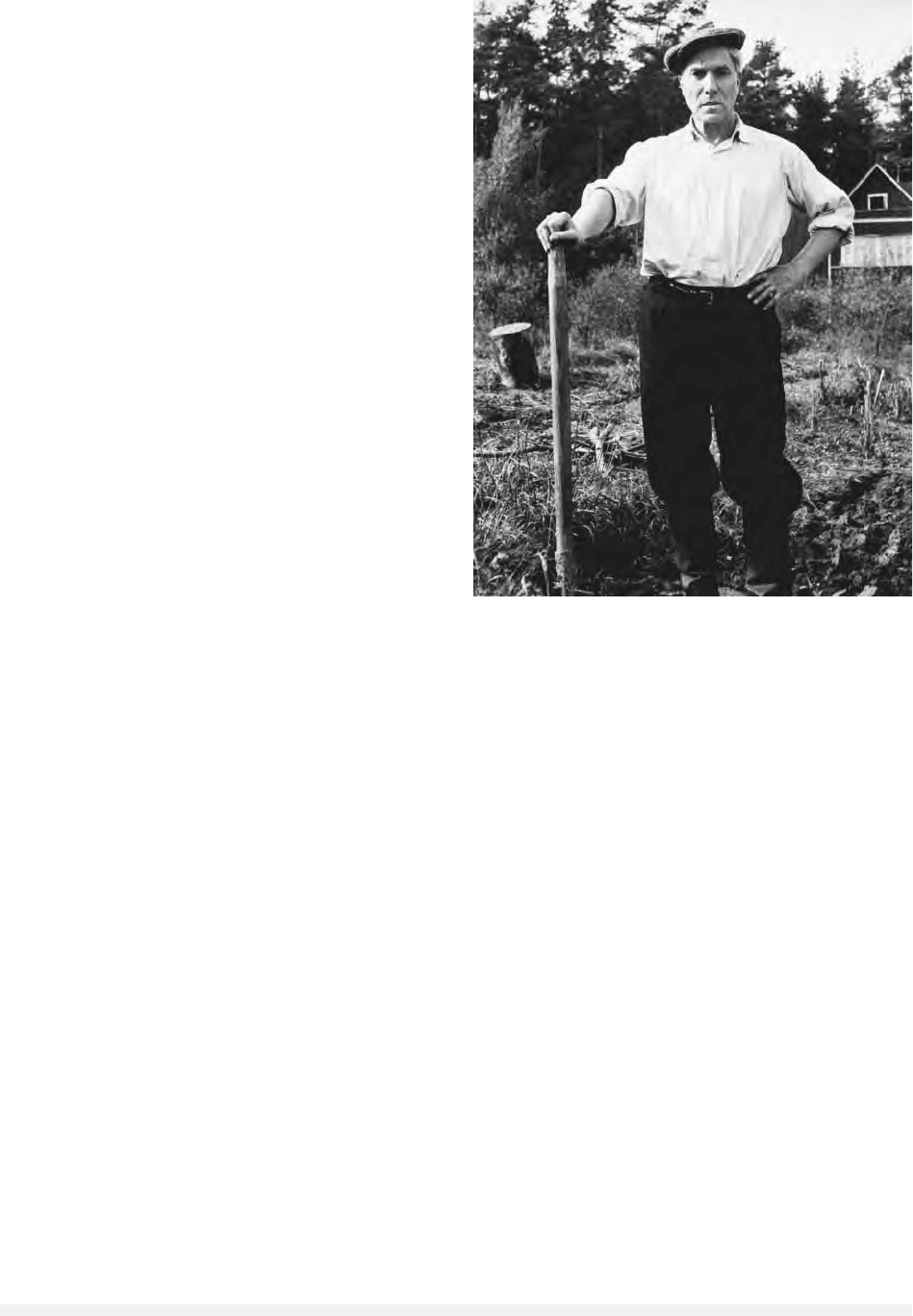

Author and poet Boris Pasternak. © J

ERRY

C

OOKE

/CORBIS

During World War II Pasternak published only

two collections of poetry, On Early Trains (1943),

and Earth’s Vastness (1945). Both collections were

written in the vein of socialist realism, with all traces

of Pasternak’s early avant-garde poetics obliterated.

The official critical reception of On Early Trains was

warm, but Pasternak himself found it embarrass-

ing and repeatedly apologized for the small num-

ber and eclectic selection of poems.

After the war, Stalin launched a campaign

against antipatriotic and cosmopolitan elements in

Soviet society. This campaign came to be known

as zhdanovshchina, after Andrei Zhdanov, the sec-

retary of the Central Committee, who obligingly

unleashed a slanderous campaign against some

major cultural figures. Zhdanov’s scapegoats in lit-

erature became the satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko and

the poet Akhmatova. Pasternak’s work came un-

der attack too, and he ended up writing almost

nothing during zhdanovshchina. Translations pro-

vided his major creative outlet.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Soviet culture ex-

perienced a period of liberalization known as the

Thaw. It was precipitated by the so-called Secret

Speech delivered by the new first secretary of

the Communist Party, Nikita Khrushchev, at the

Twentieth Party Congress in 1956. In this speech,

Khrushchev exposed Stalin’s crimes and denounced

his personality cult. It was at that time that Paster-

nak attempted to publish his novel Doctor Zhivago

(written between 1945 and 1955). No Soviet pub-

lisher, however, was willing to publish this work,

because of its controversial portrayal of the Revo-

lution. Pasternak sent the manuscript to an Italian

publisher, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who offered to

publish it. Doctor Zhivago thus first appeared in Ital-

ian, without official Soviet approval, in November

1957 and became an overwhelming success. Over

the next two years the novel was translated into

twenty-four languages.

In 1958 Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize

in literature. This honor played a double role in

Pasternak’s literary career: on the one hand, it es-

tablished his international literary stature, while on

the other it made him the target of a vicious ideo-

logical campaign unleashed against him by the So-

viet authorities. The fact that the poet had been

nominated previously for the Nobel Prize for his

poetry—specifically in 1947 and again in 1953—

did not seem to bear any significance for the cul-

tural bureaucrats. Pasternak was expelled from the

Union of Soviet Writers and accused of betraying

his country and negatively portraying the Social-

ist revolution and Soviet society—by people who,

for the most part, never even read Doctor Zhivago.

Under enormous psychological pressure and the

threat of deportation to the West, Pasternak was

forced to decline the Nobel Prize. But the attacks

against him never stopped. Doctor Zhivago was pub-

lished in the Soviet Union only posthumously, in

1988. During the last decade of his life, Pasternak’s

most distinct poetic achievement was When the

Weather Clears, a collection of poetry from 1959. It

shows him moving toward an increasingly con-

templative mood and linguistic simplicity. Paster-

nak died in his dacha in Peredelkino in 1960.

Pasternak was the only great literary figure of

his generation whose works continued to be pub-

lished throughout his career. Although he had to

pay a price, both artistic and personal, for his po-

etic freedom, he generally managed to preserve his

moral and artistic integrity. Pasternak’s work con-

tinues the best traditions of Russian literature and

is permeated with devotion to individual freedom,

moral and spiritual values, intolerance of oppres-

sive governments, and a concern with the present

and future of Russia. What distinguishes Paster-

nak’s contribution to Russian literature is the life-

affirming and resilient nature of his work and its

remarkable power to present everyday reality in a

unique and vibrant vision.

See also: CENSORSHIP; UNION OF SOVIET WRITERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barnes, Christopher. (1989). Boris Pasternak: A Literary

Biography, Vol. 1, 1860–1928. Cambridge, MA: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Barnes, Christopher. (1998). Boris Pasternak: A Literary

Biography, Vol. 2, 1928–1960. Cambridge, MA: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Conquest, Robert. (1966). Courage of Genius: The Paster-

nak Affair. London: Collins and Harvill.

Fleishman, Lazar. (1990). Boris Pasternak: The Poet and

His Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gifford, Henry. (1977). Pasternak: A Critical Study. Lon-

don: Cambridge University Press.

Livingstone, Angela. (1989). Boris Pasternak: Doctor

Zhivago. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mallac, Guy de. (1981). Boris Pasternak: His Life and Art.

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Rudova, Larissa. (1997). Understanding Boris Pasternak.

Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

L

ARISSA

R

UDOVA

PASTERNAK, BORIS LEONIDOVICH

1146

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

PATRIARCHATE

In 1589 the metropolitan of Moscow, head of the

Orthodox Church in Russia, received the new and

higher title of patriarch. This title made him equal

in rank to the four other patriarchs of the Eastern

Church: those of Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria,

and Constantinople. Patriarch Jeremias II of Con-

stantinople bestowed the new title on Metropolitan

Job, who had been metropolitan since 1586.

The establishment of the Moscow patriarchate

was the result of a complex arrangement between

Boris Godunov, de facto regent of Russia in the time

of Tsar Fyodor (r. 1584–1598), and the Greeks. The

new title implied the acceptance by the Greek

church of the autocephaly (autonomy) of the Russ-

ian church and considerably reinforced the prestige

of the Russian church and state. In return the

Greeks found a protector for the Orthodox peoples

of the Ottoman Empire and a strong source of fi-

nancial support for their church. Building on the

powers and position of the earlier metropolitans,

the patriarchs of Moscow were the leading figures

in the church in Russia until the abolition of the

office after the death of the last patriarch in 1700.

The power of the patriarch came not only from his

authority over the church, but also from his great

wealth in land and serfs in central Russia. As the

Russian church, like the other Orthodox churches,

was a conciliar church, the power of the patriarchs

was limited by the power of the tsar as well as by

the requirement that, when making important de-

cisions, a patriarch call a council of the bishops and

most influential abbots.

Job, the first patriarch, supported Boris Go-

dunov as regent and later as tsar. The defeat of

Boris by the first False Dmitry at the beginning of

the Time of Troubles led to the ouster of Job in

1605. The Greek bishop Ignaty replaced him that

year, only to be expelled in turn after the Moscow

populace turned against the False Dmitry. The new

patriarch Germogen (1606–1612) was one of the

leaders of Russian resistance to Polish occupation

during the later years of the Troubles. Only after

the final end of the Troubles and the election of

Mikhail Romanov as tsar was the situation calm

enough to permit the choosing of a new patriarch.

This was tsar Mikhail’s father, Patriarch Filaret

(1619–1633). An important boyar during the 1590s,

he had been exiled by Boris Godunov and forced to

enter a monastery. Imprisoned in Poland during the

Troubles, in 1619 he was allowed to return home,

where the Greek patriarch of Jerusalem, Theo-

phanes; the Russian clergy; and tsar Mikhail chose

him to lead the church. Filaret quickly settled sev-

eral disputed points of liturgy and began to rebuild

the Russian church after the desolation of the Time

of Troubles. Much of the time during his patriar-

chate was occupied with matters having to do with

relations with the Orthodox of the Ukraine and Be-

lorussia under Polish Catholic rule. Filaret also

played a major role in Russian politics.

Under patriarchs Joseph I (1634–1640) and

Joseph (1640–1652) the church was quiet. Only in

the last years of Joseph’s patriarchate did new cur-

rents arise, the Zealots of Piety under the leader-

ship of Stefan Vonifatev, spiritual father to Tsar

Alexei (r. 1645–1676). The Zealots wanted reform

of the liturgy and more preaching, with the aim of

bringing the Christian message closer to the laity.

Iosif was skeptical of their efforts, and their tri-

umph came only after his death under the new

patriarch Nikon (1652–1666, d. 1681). Nikon ac-

cepted the Zealots’ program, but his liturgical re-

forms led to a schism in the church and the

formation of groups known as Old Ritualists or Old

Believers. Conflict with tsar Alexei led Nikon to ab-

dicate in 1658, and he was formally deposed at a

church council in 1666, which also condemned the

Old Ritualists. The short patriarchates of Joseph II

(1667–1672) and Pitirim (1672–1673) were largely

devoted to efforts to defeat the Old Ritualists

and restore order after the eight-year gap in

church authority. Their successor Patriarch Joakim

(1674–1690) was a powerful figure reminiscent in

some ways of Nikon. He attempted to reorganize

the diocesan system of the church, found schools,

and suppress the Old Ritualists, an increasingly

fruitless effort. Russia’s first European-type school,

the Slavo-Greco-Latin Academy, was set up with

his patronage in 1685. He supported the young Pe-

ter the Great in overthrowing his half-sister, the

regent Sophia, in 1689. The last patriarch, Adrian

(1690–1700), usually considered a cultural con-

servative, was actually a complex figure who sup-

ported some of the new currents in Russian culture

coming from Poland and the Ukraine. His relations

with Peter the Great were never warm, and, when

he died, Peter did not permit the church to replace

him, and placed the Ukrainian Metropolitan of

Ryazan, Stefan Yavorsky, as administrator of the

church without the patriarchal title. Ultimately,

Peter abolished the position and organized the Holy

Synod in 1719, a committee of clergy and laymen

and under a layman, to take the place of the pa-

triarch. The Synod headed the Orthodox church in

Russia until 1917.

PATRIARCHATE

1147

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Beginning at the end of the nineteenth century,

voices within the Orthodox Church called for the

reestablishment of the patriarchate. Such a move

would mean the lessening of state control over the

church and the beginning of separation of church

and state, so both the government and many con-

servative churchmen opposed it. The collapse of the

tsarist regime in March 1917 made such a radical

change not only possible but necessary. Conse-

quently, the Synod organized a council of the Russ-

ian church, which opened in August 1917. Its work

continued after the Bolshevik seizure of power, and

elected Tikhon, the metropolitan of Moscow, to the

dignity of patriarch on November 21, 1917. Patri-

arch Tikhon’s fate was to head the church during

the Russian Civil War and the early years of Soviet

power. Tikhon was sympathetic to the White anti-

Bolshevik cause and was faced with a radically anti-

clerical and explicitly atheist revolutionary regime.

He suffered imprisonment and harassment from

the state, as well as internal dissent in the church.

Upon his death in 1925, the church was in no po-

sition to replace him. The ensuing decades saw

fierce antireligious propaganda by the Soviet au-

thorities and massive persecution. Most churches

in the USSR were closed, and thousands of priests

and monks were imprisoned and executed.

In 1943 Josef Stalin suddenly decided to once

again legalize the existence of the Orthodox church.

He met with the few remaining members of the hi-

erarchy to explain the new policy and permitted a

council of the church to choose a new patriarch.

The choice was Sergei, metropolitan of Moscow, se-

nior living bishop and erstwhile prerevolutionary

rector of the St. Petersburg Spiritual Academy. The

elderly Patriarch Sergei died early in 1944, and in

1945 Alexei, metropolitan of Leningrad, replaced

him, continuing to lead the church until his death

in 1970. In these years the Soviet state permitted a

modest revival of worship and religious life, but also

placed the church under the watchful eye of the

state Council on the Russian Orthodox Church,

headed in 1943–1957 by Major General Georgy

Karpov of the KGB. Patriarch Alexei endured the last

major attack on the church under Nikita

Khrushchev as well as the modus vivendi of the later

Soviet years. His successors were patriarchs Pimen

(1970–1990) and Alexei II (beginning in 1990).

See also: ALEXEI I, PATRIARCH; ALEXEI II, PATRIARCH; FI-

LARET ROMANOV, PATRIARCH; HOLY SYNOD; JOAKIM,

PATRIARCH; JOB, PATRIARCH; METROPOLITAN; NIKON,

PATRIARCH; PIMEN, PATRIARCH; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX

CHURCH; SERGEI, PATRIARCH; TIKHON, PATRIARCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bushkovitch, Paul. (1992). Religion and Society in Russia:

the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Pospielovsky, Dmitry. (1984). The Russian Church under

the Soviet Regime, 1917–1982. 2 vols. Crestwood, NY:

St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

P

AUL

A. B

USHKOVITCH

PAUL I

(1754–1801), tsar of Russia 1796–1801.

Tsar Paul I (Paul Petrovitch) was born on Sep-

tember 20, 1754. He was officially the son of Tsare-

vitch Peter and his wife Catherine, but more

probably the son of Sergei Saltykov—chamberlain

at the court and lover of Catherine since 1752. At

his birth, the child was taken away from his par-

ents by his great-aunt, ruling Empress Elizabeth,

who brought him to her court, supervised his ed-

ucation, and surrounded him with several tutors

such as the old count Nikita Panin. He was eight

in July 1762 when, six months after Elizabeth’s

death and his father’s coronation as Peter III, his

mother acceded to the throne as Catherine II by a

coup that first led to the deposition of the tsar and

then to his assassination, intended or not, by Alexei

Orlov, one of the main leaders of the conspiracy.

From that time on Catherine II, who feared his pop-

ularity, kept the child far away from power; Paul

Petrovitch grew up in relative loneliness that con-

tributed to make him distrustful. In September

1773, he married Princess Wilhelmine of Hesse-

Darmstadt who died in April 1776 while deliver-

ing her first baby. In September of that same year,

pushed by his mother who wanted an heir, he mar-

ried Princess Sophia Dorothea of Württemberg

(Maria Fiodorovna), who would give birth to ten

children. Empress Catherine took away the first

two boys, Alexander (born in December 1777) and

Constantin (born in April 1779); she personally

took care of their education and later intended to

appoint Alexander as her heir, instead of Paul.

From September 1781 to August 1782, Paul and

his wife made an eleven-month tour that brought

them to all the European courts and allowed the

future tsar to discover European political models

and ways of life.

After returning to Russia, still deprived of their

older sons and of any power, Paul and Maria Fiodor-

PAUL I

1148

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ovna lived at Gatchina, a large estate given to them

by Catherine. At Gatchina, the tsarevitch had his

own court and a personal small army, composed

of 2,400 soldiers and 140 officers. Isolated, fasci-

nated by the Prussian model, Paul began to show

an abnormal obsession for military parades and

processions and started to tyrannize his soldiers.

But at the same time, he established a hospital

where peasants could receive free medical care,

founded a school for the children of his serfs, and

was tolerant of the Lutheran faith of his Finnish

serfs.

On November 5, 1796, the death of Catherine

made him tsar at the age of forty-two. He made

many decisions—more than two thousand ukases

in five years—that revealed the rejection of his

mother’s heritage, but they were not always con-

sistent. In domestic policy, he first issued on April

1797 a decree establishing the principle of male pri-

mogeniture for succession to the throne, so as to

eliminate any political turmoil. He proclaimed a

general amnesty, freed all of Catherine’s political

prisoners, including the thinker Nikolai Novikov,

and liberated the twelve thousand Poles kept in

Russian jails since the last Polish war of indepen-

dence led by Tadeusz Kociuszko. His hate for

Catherine’s immoral behavior and way of govern-

ing brought him to exile his mother’s lovers and

to cut down court expenses. His piety led him to

forbid landowners from forcing serfs to work on

Sundays and on religious feasts, while his mistrust

of the nobility led him to impose a new tax on no-

bles’ estates. All these measures, as well as the

reorganization of the Russian military service ac-

cording to the Prussian model and the reintroduc-

tion of corporal punishment for nobles, made him

very unpopular quickly among the aristocracy.

At the same time, deeply hostile to the French

Revolution and anxious about its potential impact

on the Russian Empire, he heavily censored intel-

lectual and political productions, rejecting the sym-

bols of a French liberal influence in all spheres, even

in the more superficial ones such as fashion. Rely-

ing on a growing bureaucracy, he reinforced the

autocratic regime, condemning random innocents

to Siberia or jail to show his unlimited power. He

also systematically repressed peasant riots and ex-

tended serfdom to the Southern colonies. His do-

mestic policy was therefore a mixture of generous

and tyrannical measures.

In foreign policy, his choices were much more

consistent. He pursued his mother’s policy of ex-

pansionism in the Far East and Caucasus: in 1799,

he chartered a Russian-American Company to fa-

vor Russian economic and commercial expansion

in the North Pacific; and in December 1800 he an-

nexed the kingdom of Georgia. As to war in Eu-

rope, he first chose to abstain but finally decided in

1798–1799 to join the Second Coalition against

Napoleon I, together with Great Britain, Naples,

Portugal, Austria, and the Ottoman Empire. Russ-

ian troops obtained brilliant successes: in winter

1798–1799, Admiral Fyodor Ushakov took the

Ionian Islands from the French armies and estab-

lished a republic occupied by the Russians. Mean-

while, General Alexander Suvarov won impressive

battles in Italy (Cassano and Novi) and Switzerland

in 1798–1800. And in November 1798, opposing

Napoleon’s claim to the Island of Malta, Paul agreed

to become the protector and Great-Master of the

Order of Malta. But in 1800, irritated by the sus-

picious behavior of his Austrian and British allies

and convinced that an alliance with Napoleon could

favor the Russian national interests, Paul abruptly

PAUL I

1149

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

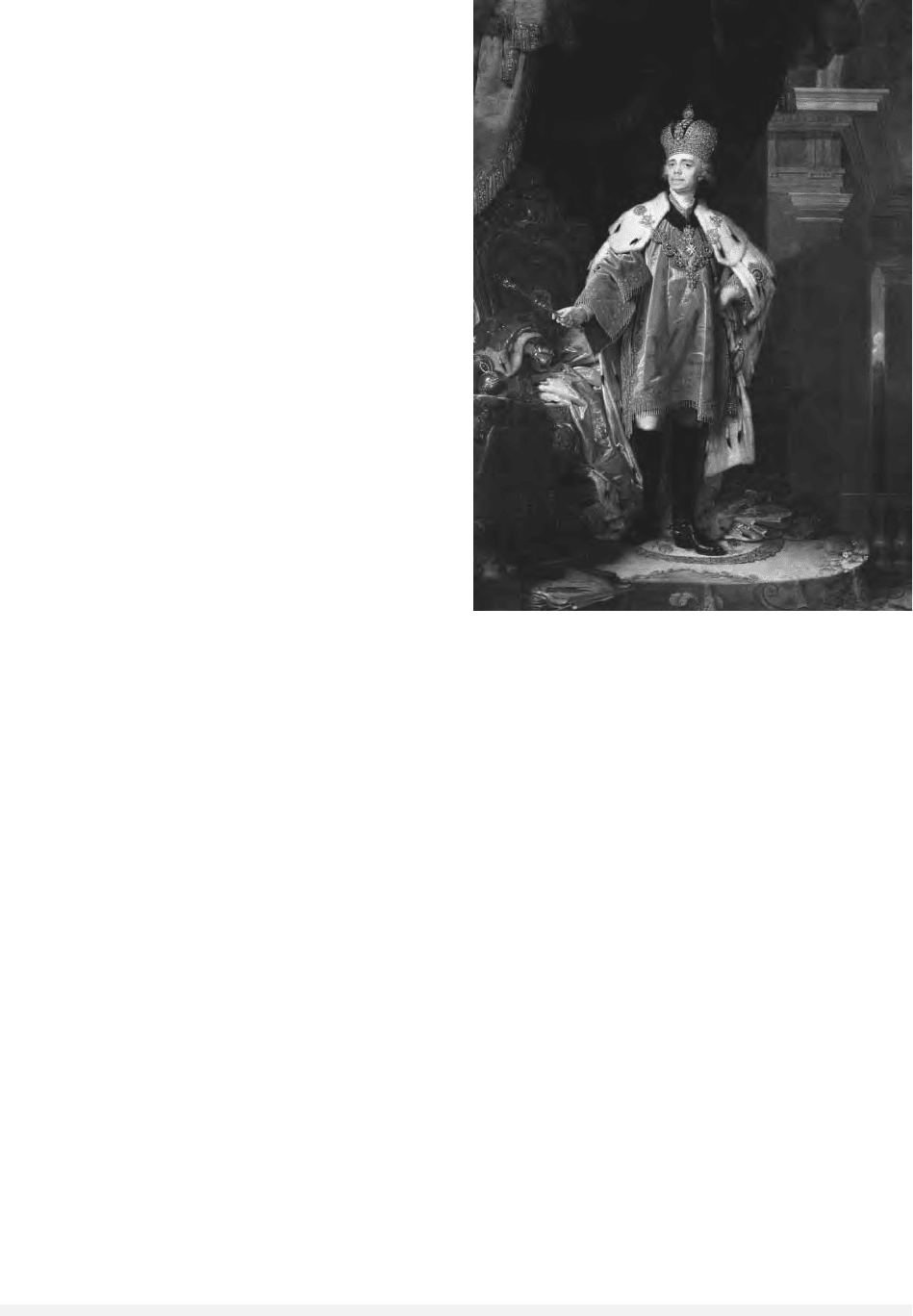

Emperor Paul I by Vladimir Lukic Borovikovsky. © T

HE

S

TATE

R

USSIAN

M

USEUM

/CORBIS

changed his mind. He led Russia into a rapproche-

ment with France and a war against Britain; to this

end, in January 1801 he launched a military ex-

pedition toward India. These last decisions were

perceived as dangerous and even foolish by a fac-

tion of the court. Encouraged by Charles Whit-

worth, the British ambassador in St. Petersburg,

and with the passive complicity of Tsarevitch

Alexander, several figures close to the tsar, such as

Nikita Panin the young, Count Peter von Pahlen,

general governor of St. Petersburg, and Leontii Ben-

nigsen, led a conspiracy that culminated with

Paul’s brutal assassination in March 1801.

See also: CATHERINE II; NOVIKOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McGrew, Roderick Erle. (1992). Paul I of Russia, 1754–1801.

Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

Ragsdale, Hugh. (1998). Tsar Paul and the Question of

Madness: An Essay in History and Psychology. New

York: Greenwood Press.

M

ARIE

-P

IERRE

R

EY

PAVLIUCHENKO, LYUDMILA

MIKHAILOVNA

(1916–1974), soldier, historian, and journalist.

A World War II heroine who a became cham-

pion sniper with 309 kills to her credit, including

thirty-six enemy snipers, Pavlyuchenko was the

first Soviet citizen received at the White House. She

retired at the rank of major after serving in the

No. 2 Company, Second Battalion, 54th Razin Reg-

iment, 25th “V.I. Chapayev” Division of the Inde-

pendent Maritime Army, and was awarded the

status of Hero of the Soviet Union on 25 October

1943.

Born in Belaya Tserkov, Pavliuchenko com-

pleted high school while working in the Arsenal

factory in Kiev, where she mastered small arms in

a military club. She also trained as a sniper at the

paramilitary Osoaviakhim (loosely translated as

“Society for the Promotion of Aviation and Chem-

ical Defense”) and took up hang-gliding and para-

chuting. After enrolling at the State University of

Kiev, she successfully defended her master’s thesis

on Bohdan Khmelnitsky.

Pavliuchenko volunteered for military service

during the summer of 1941 and became an expert

sniper for the Independent Maritime Army in

Odessa and Sevastopol. Invited by Eleanor Roo-

sevelt, she toured North America in August 1942

and was presented with a Winchester rifle in

Toronto. In 1943 she completed the Vystrel

Courses for Officers. On graduating from Kiev Uni-

versity in 1945, she became a military historian

and journalist. Affected with a concussion and

wounded four times, Pavliuchenko died prema-

turely and was buried at the prestigious Novode-

vichye Cemetery in Moscow.

See also: AVIATION; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cottam, Kazimiera J. (1998). Women in War and Resis-

tance: Selected Biographies. Nepean, Canada: New Mil-

itary Publishing.

Pavlichenko, Liudmila Mikhailovna. (1977). “I was a

sniper.” In The Road of Battle and Glory, ed. I.M. Dan-

ishevsky, tr. David Skvirsky. Moscow: Politizdat.

K

AZIMIERA

J. C

OTTAM

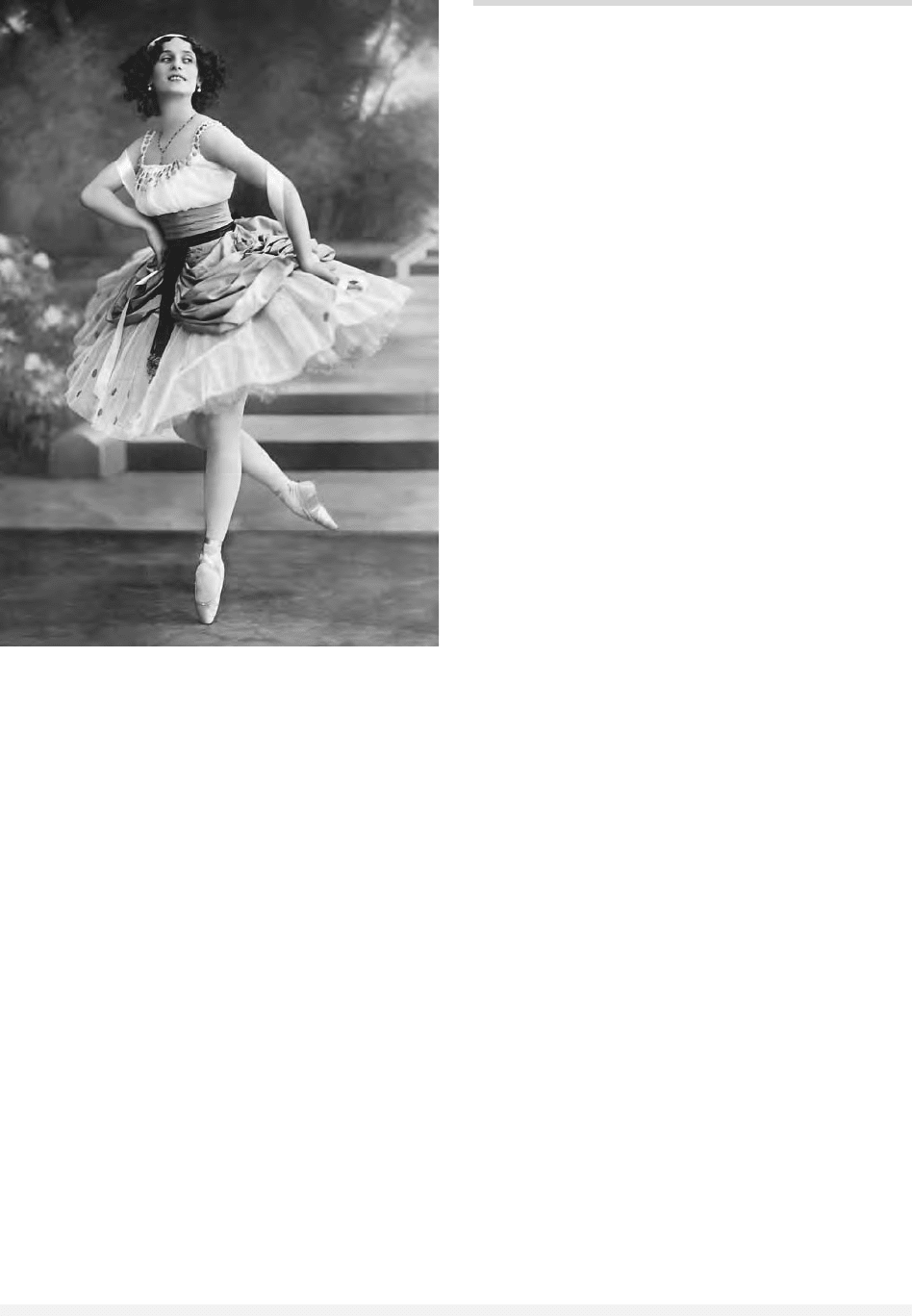

PAVLOVA, ANNA MATVEYEVNA

(1881–1931), the most famous of Russian balleri-

nas.

Anna Matveyevna Pavlova (patronymic later

changed to Pavlovna) began her career in the St.

Petersburg Imperial Theaters in 1898, which ended

amidst her usual flurry of performing in 1930,

only weeks before her death. Pavlova’s rise to the

rank of ballerina in the Imperial Theaters (by 1906)

was rapid, though her artistic breakthrough came

the following year, when she appeared in several

short works choreographed by Michel Fokine. Two

of these works (Les Sylphides and Le Pavillon

d’Armide) would join the roster of Serge Diagilev’s

Ballets Russes (as would their star performers,

Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky). Both the ballets and

dancers achieved unprecedented fame in that com-

pany’s Paris season of 1909. Pavlova debuted an-

other Fokine composition in St. Petersburg in 1908,

a solo that would become her signature work and

that remains strongly identified with her: The Swan,

to music of Camille Saint-Saëns. Popularly known

as the dying swan, this evanescent figure suited

Pavlova’s physical type and stage temperament.

Pavlova excelled in ethereal, romantic roles such as

PAVLIUCHENKO, LYUDMILA MIKHAILOVNA

1150

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

“Giselle,” and would later create for herself a mul-

titude of roles in which she portrayed butterflies,

roses, snowflakes, dragonflies, poppies, leaves, and

various other delicate creatures. After achieving in-

ternational stardom with Diagilev’s Ballets Russes,

Pavlova struck out on her own, first negotiating

an enviable contract with the Imperial Theaters,

and subsequently abandoning the Russian stage to

settle in London. In twenty years of touring the

globe, Pavlova came to personify the peripatetic

Russian ballerina, the touring star whose only

home was the stage.

See also: BALLET; NIJINKSY, VASLAV FOMICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Money, Keith. (1982). Pavlova: Her Art and Life. New

York: Knopf.

T

IM

S

CHOLL

PAVLOV, IVAN PETROVICH

(1849–1936), Russian physiologist and Nobel Prize

winner.

Ivan Pavlov was born in Ryazan. His father,

a local priest, wanted him to attend the theolog-

ical seminary, but Pavlov’s interest in natural

sciences led him to enroll in St. Petersburg Uni-

versity in 1870. In 1883 he completed his doc-

toral dissertation and in 1890 became professor

and head of the physiology division of the St. Pe-

tersburg Institute of Experimental Medicine,

where he remained until 1925. Pavlov’s work on

the functioning of the digestive system earned

him the Nobel Prize in 1904. His originality lay

in his approach to physiology, which considered

the coordinated functioning of the organism as a

whole, as well as his innovative surgical tech-

nique, which allowed him to observe digestion in

live animals.

Pavlov’s most well known research involved

the study of conditioned reflexes. In his famous ex-

periment, he placed a dog in a room free of all dis-

tractions. He found that the dog, accustomed to

hearing a bell ring when being fed, would eventu-

ally salivate at the sound of the bell alone. Pavlov

also applied his findings to the human nervous

system. His work advanced the understanding of

physiology and influenced international develop-

ments in medicine, psychology, and pedagogy.

Pavlov did not support the Bolshevik Revolu-

tion and in 1920 asked for permission to leave with

his family. Vladimir Lenin, aware of the interna-

tional prestige Pavlov brought to science in the So-

viet Union, personally intervened to guarantee the

resources for Pavlov to continue his research. In

1935, the International Congress of Physiologists

awarded Pavlov the distinction of world senior

physiologist. He died of pneumonia in Leningrad at

the age of eighty-seven.

See also: EDUCATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Joravsky, David. (1989). Russian Psychology: A Critical

History. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Porter, Roy, ed. (1994). The Biographical Dictionary of Sci-

entists, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

S

HARON

A. K

OWALSKY

PAVLOV, IVAN PETROVICH

1151

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Prima ballerina Anna Pavlova is considered one of the premier

dancers of the twentieth century. © CORBIS. R

EPRODUCED BY

PERMISSION

.

PAVLOV, VALENTIN SERGEYEVICH

(1937–2003), prime minister.

Valentin Sergeyevich Pavlov was Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev’s minister of finance when per-

estroika was in full swing during the 1980s and

the last prime minister of the Union of Soviet So-

cialist Republics before its collapse. Discharged on

August 22, 1991 by President Gorbachev’s decree

for his role in the coup attempt that month, Pavlov

was arrested a week later, imprisoned for sixteen

months, and finally amnestied in May 1994. He

died on March 30, 2003, at the age of sixty-five.

For most of his career, Pavlov occupied posi-

tions in the Russian SFSR and USSR related to fi-

nance. Having joined the Communist Party in

1962, he headed the Finance Department in the

State Planning Committee (Gosplan) in 1979. Af-

ter working briefly as first deputy finance minis-

ter in Nikolai Ryzhkov’s government in 1986,

Pavlov became chairman of the State Committee

for Prices from August 1986 to June 1989. With

approval of the party leadership, Pavlov reformed

prices, withdrawing high-denomination notes from

circulation overnight. This act caused a financial

crisis and a great measure of unpopularity for him.

Frustrated by his inability to maintain a grip on

the ruble’s value, while allowing the Soviet econ-

omy some small exposure to the free market,

Pavlov blamed a plot by western banks for his de-

cision to withdraw the bank notes. As the Soviet

economy grew increasingly unstable and inflation

skyrocketed, Pavlov tried other unpopular eco-

nomic measures, but soon realized that the politi-

cal and economic crisis was out of his control. The

contradictions between Gorbachev’s desire to re-

form the Soviet Union and keep it intact came to

a head in August 1991. While the president was

resting on the Black Sea, KGB chief Vladimir

Kryuchkov formed the “State Committee for the

State of Emergency” and placed Gorbachev under

house arrest.

Along with eleven other men, Pavlov joined the

emergency committee on August 19, 1991. This

was no doubt Pavlov’s least distinguished moment.

Rather than conducting himself as a viable substi-

tute for the supposedly ill president, Pavlov stayed

in bed, claiming that he was too sick. His co-

conspirators later said that he spent much of the

three days of the attempted coup drunk.

See also: AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; PERESTROIKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Copson, Raymond W. (1991). Soviet Coup Attempt: Back-

ground and Implications. Washington, DC: Congres-

sional Research Service.

Goldman, Marshall I. (1987). Gorbachev’s Challenge: Eco-

nomic Reform in the Age of High Technology. New York:

Norton.

Matlock, Jack F. (1995). Autopsy on an Empire: the Amer-

ican Ambassador’s Account of the Collapse of the Soviet

Union. New York: Random House.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

PEASANT ECONOMY

The term peasant economy refers to modes of rural

economic activity with certain defined characteris-

tics. The first characteristic is that the basic unit of

production is the household; therefore, the demo-

graphic composition of the household was of para-

mount importance in determining the volume of

output, the percentage of output consumed by the

household, and, thus, the net remainder to be used

for investment or savings. Second, the majority of

household income is derived from agricultural pro-

duction, that is, the household is dependent upon

its own labor. Third, because the household de-

pended upon agricultural production for survival,

peasant households were assumed to be conserva-

tive and resistant to changes that would threaten

their survival. In particular, a school of thought

called the “moral economy” arose, which argued

that peasant households would resist the commer-

cialization of agriculture because it violated their

values and beliefs—their moral economy—and at-

tempted to replace the patterns of interaction

among personal networks in the villages with im-

personal transactions based on market principles.

Perhaps the greatest theorist of the peasant

economy was a Russian economist named Alexan-

der Chayanov, who lived from 1888 to 1939.

Chayanov published a book entitled Peasant Farm

Organization, which postulated a theory of peasant

economy with application for peasant economies

beyond Russia. He argued that the laws of classi-

cal economics do not fit the peasant economy; in

other words, production in a household was not

based upon the profit motive or the ownership of

the means of production, but rather by calculations

made by households as consumers and workers. In

modern terminology, the family satisfied rather

than maximized profit.

PAVLOV, VALENTIN SERGEYEVICH

1152

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY