Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Pearl, Deborah. (1996). “From Worker to Revolutionary:

The Making of Worker Narodovol’tsy.” Russian His-

tory 23(1–4):11–26.

Venturi, Franco. (1966). Roots of Revolution: A History of

the Populist and Socialist Movements in Nineteenth Cen-

tury Russia, tr. Francis Haskell. New York: Univer-

sal Library.

D

EBORAH

P

EARL

PERESTROIKA

Perestroika was the term given to the reform process

launched in the Soviet Union under the leadership

of Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. Meaning “recon-

struction” or “restructuring,” perestroika was a con-

cept that was both ambiguous and malleable. Its

ambiguity lay in the fact that it might convey no

more than a reorganization of existing Soviet in-

stitutions and thus be a synonym for reform of a

modest kind or, alternatively, it could signify re-

construction of the system from the foundations

up, thus amounting to transformative change. The

vagueness and ambiguity were initially an advan-

tage, for even the term reform had become taboo

during the conservative Leonid Brezhnev years af-

ter the Soviet leadership had been frightened by the

Prague Spring reforms of 1968.

Perestroika had the advantage of coming with-

out political and ideological baggage. Everyone

could—in the first two years, at least, of the Mikhail

Gorbachev era—be in favor of it. Its malleability

meant that under this rubric some urged modest

change that in their view was enough to get the

economy moving again while others who wished

to transform the way the entire system worked

were able to advance more daring arguments, tak-

ing cover under the umbrella of perestroika. Within

Gorbachev’s own top leadership team, both Yegor

Ligachev and Alexander Yakovlev expressed their

commitment to perestroika, but for the latter this

meant much more far-reaching political reform

than for the former. Once political pluralism had

by 1989 become an accepted norm, perestroika as

a concept had largely outlived its political utility.

For Gorbachev himself the term “perestroika”

meant different things at different times. Initially,

it was a euphemism for “reform,” but later it came

to signify systemic change. Gorbachev’s views un-

derwent a major evolution during the period he

held the post of General Secretary of the Central

Committee of the CPSU and that included the

meaning he imparted to perestroika. In an impor-

tant December 1984 speech before he became So-

viet leader, Gorbachev had said that one of the

important things on the agenda was a “perestroika

of the forms and methods of running the econ-

omy.” By 1987 the concept for Gorbachev was

much broader and clearly embraced radical politi-

cal reform and the transformation of Soviet for-

eign policy. Gorbachev’s thinking at that time was

set out in a book, Perestroika: New Thinking for our

Country and the World. While the ideas contained

were far removed from traditional Soviet dogma,

they by no means yet reflected the full evolution

of Gorbachev’s own position (and, with it, his un-

derstanding of perestroika). In 1987 Gorbachev was

talking about radical reform of the existing system.

During the run-up to the Nineteenth Conference of

the Communist Party, held in the summer of 1988,

he came to the conclusion that the system had to

be transformed so comprehensively as to become

something different in kind. In 1987 he still spoke

about “communism,” although he had redefined it

to make freedom and the rule of law among its un-

familiar values; by the end of the 1980s, Gorbachev

had given up speaking about “communism.” The

“socialism,” of which he continued to speak, had

become socialism of a social democratic type.

Perestroika became an overarching conception,

under which a great many new concepts were in-

troduced into Soviet political discourse after 1985.

These included such departures from the Marxist-

Leninist lexicon as glasnost (openness, trans-

parency), pravovoe gosudarstvo (a state based on the

rule of law), checks and balances, and pluralism.

One of the most remarkable innovations was Gor-

bachev’s breaking of the taboo on speaking posi-

tively about pluralism. Initially (in 1987) this was

a “socialist pluralism” or a “pluralism of opinion.”

That, however, opened the way for others in the

Soviet Union to talk positively about “pluralism”

without the socialist qualifier. By early 1990 Gor-

bachev himself had embraced the notion of “polit-

ical pluralism,” doing so at the point at which he

proposed to the Central Committee removing from

the Soviet Constitution the guaranteed “leading

role” of the Communist Party.

Even perestroika as understood in the earliest

years of Gorbachev’s leadership—not least because

of its embrace of glasnost—opened the way for real

political debate and political movement in a system

which had undergone little fundamental political

change for decades. In his 1987 book, Perestroika,

PERESTROIKA

1163

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Gorbachev wrote: “Glasnost, criticism and self-

criticism are not just a new campaign. They have

been proclaimed and must become a norm in the

Soviet way of life . . . . There is no democracy, nor

can there be, without glasnost. And there is no

present-day socialism, nor can there be, without

democracy.” Such exhortation was alarming to

those who wished to preserve the Soviet status quo

or to revert to the status quo ante. It was, though,

music to the ears of people who wished to promote

the more rapid democratization of the Soviet sys-

tem, even to advocate moving further and faster

than Gorbachev at the time was prepared to en-

dorse.

If perestroika is considered as an epoch in So-

viet and Russian history, rather than a concept

(though conceptual change in a hitherto ideocratic

system was crucially important), it can be seen as

one in which a Pandora’s box was opened. The sys-

tem, whatever its failings, had been highly effec-

tive in controlling and suppressing dissent, and it

was far from being on the point of collapse in 1985.

Perestroika produced both intended and unintended

consequences. From the outset Gorbachev’s aims

included a liberalization of the Soviet system and

the ending of the Cold War. Liberalization, in fact,

developed into democratization (the latter term be-

ing one that Gorbachev used from the beginning,

although its meaning, too, developed within the

course of the next several years) and the Cold War

was over by the end of the 1980s. A major aspect

of perestroika in its initial conception was, how-

ever, to inject a new dynamism into the Soviet

economy. In that respect it failed. Indeed, Gor-

bachev came to believe that the Soviet economic

system, just like the political system, needed not

reform but dismantling and to be rebuilt on dif-

ferent foundations.

The ultimate unintended consequence of pere-

stroika was the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Liberalization and democratization turned what

Gorbachev had called “pre-crisis phenomena” (most

PERESTROIKA

1164

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

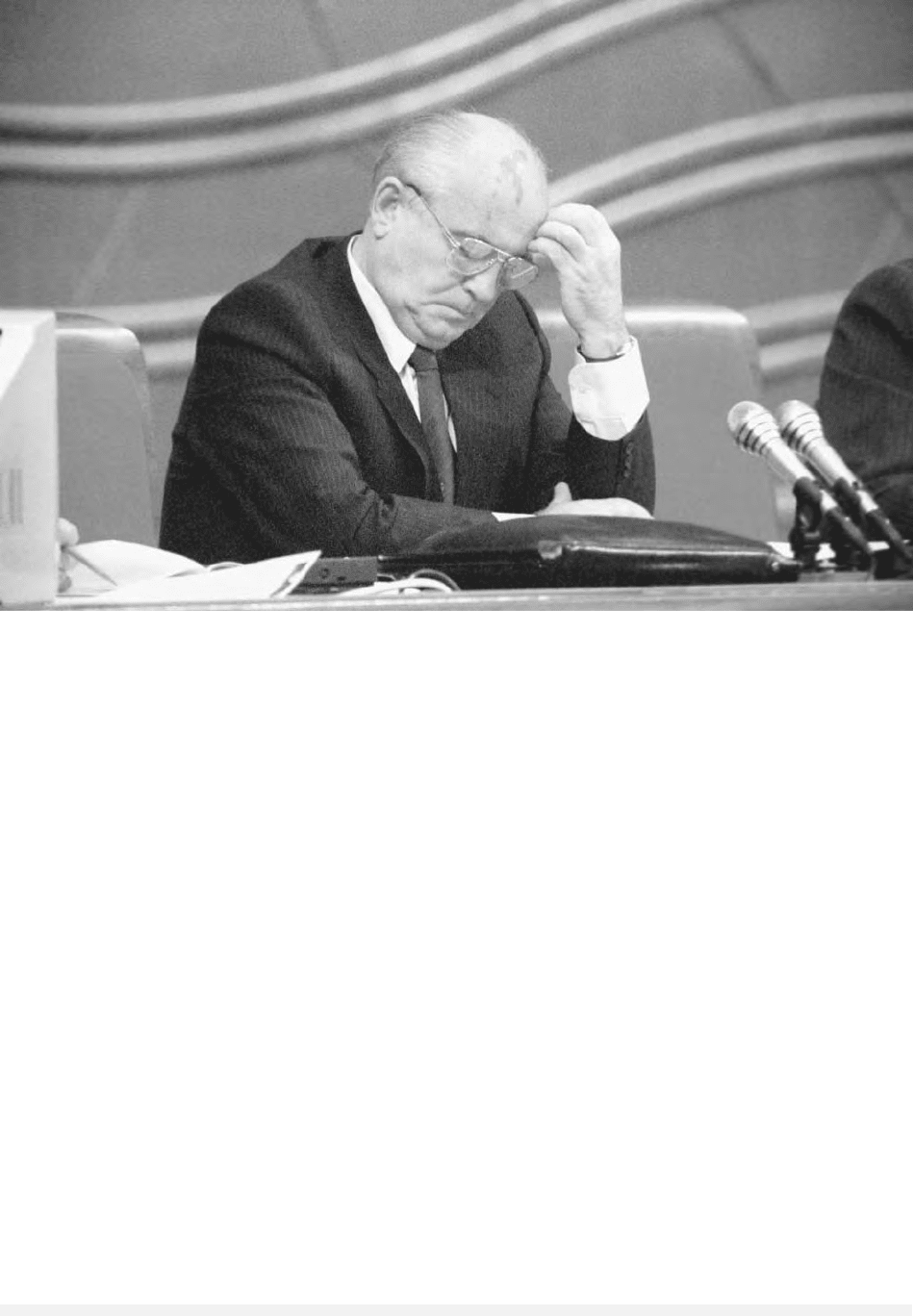

Mikhail Gorbachev reacts to the announcement of foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze’ planned resignation at a Congress of the

People’s Deputies meeting held December 20, 1990. B

ORIS

Y

URCHENKO

/A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

notably, economic stagnation) during the early

1980s into a full-blown crisis of survival of the

state by 1990–1991. Measuring such an outcome

against the initial aims of perestroika suggests its

failure. But the goals of the foremost proponents

of perestroika, and of Mikhail Gorbachev person-

ally, rapidly evolved, and democratization came to

be given a higher priority than economic reform.

At the end of this experiment in the peaceful trans-

formation of a highly authoritarian system, there

were fifteen newly independent states and Russia

itself had become a freer country than at any point

in its previous history. Taken in conjunction with

the benign transformation of East-West relations,

these results constitute major achievements that

more than counterbalance the failures. They point

also to the fact that there could be no blueprint for

the democratization of a state that had been at

worst totalitarian and at best highly authoritarian

for some seven decades. Perestroika became a process

of trial and error, but one that was underpinned

by ideas and values radically different from those

which constituted the ideological foundations of the

unreformed Soviet system.

See also: DEMOCRATIZATION; GLASNOST; GORBACHEV,

MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH; NEW POLITICAL THINKING

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Archie. (1996). The Gorbachev Factor. New York:

Oxford University Press.

English, Robert D. (2000). Russia and the Idea of the West:

Gorbachev, Intellectuals, and the End of the Cold War.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Gorbachev, Mikhail. (1987). Perestroika: New Thinking for

Our Country and the World. London: Collins.

Gorbachev, Mikhail, and Mlynar, Zdenek. (2002). Con-

versations with Gorbachev: On Perestroika, the Prague

Spring, and the Crossroads of Socialism. New York:

Columbia University Press.

Hough, Jerry F. (1997). Democratization and Revolution

in the USSR. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Matlock, Jack F., Jr. (1995). Autopsy of an Empire: The

American Ambassador’s Account of the Collapse of the

Soviet Union. New York: Random House.

A

RCHIE

B

ROWN

PERMANENT REVOLUTION

“Permanent Revolution” was Leon Trotsky’s ex-

planation of how a communist revolution could

occur in an industrially backward Russia. Accord-

ing to classical Marxism, only a society of advanced

capitalism with a large working class was ripe for

communist revolution. Russia met neither prereq-

uisite. Further, Karl Marx conceived of a two-stage

revolution: first the bourgeois revolution, then in

sequence the proletarian revolution establishing a

dictatorship for transition to communism. Trotsky

argued that the two-stage theory did not apply.

Rather, he said, Russia was in a stage of uneven

development where both bourgeois and proletarian

revolutions were developing together under the im-

pact of the advanced West.

Trotsky predicted that once revolution broke

out in Russia it would be in permanence as the

result of an East–West dynamic. The bourgeois ma-

jority revolution would be overthrown by a con-

scious proletarian minority that would carry

forward the torch of revolution. However, a sec-

ond phase was necessary: namely, the proletarian

revolution in Western Europe ignited by the Rus-

sian proletariat’s initiative; the West European pro-

letariat now in power rescues the beleaguered

proletarian minority in Russia; and the path is

opened to the international communist revolution.

Trotsky’s theory seemed corroborated in the

1917 Russian revolution. Tsarism was overthrown

by a bourgeois Provisional Government in Febru-

ary which the Bolsheviks then overthrew in Octo-

ber. However, the second phase posited by Trotsky’s

theory, the West European revolution, did not ma-

terialize. The Bolsheviks faced the dilemma of how

to sustain power where an advanced industrial

economy did not exist. Was not Bolshevik rule

doomed to failure without Western aid?

Usurping power, Josef Stalin answered Trot-

sky’s theory with his “socialism in one country.”

Curiously, his recipe was similar to a strategy Trot-

sky earlier proposed, namely, command economy,

forced industrialization, and collectivization. With

the communist collapse in Russia in 1991 both

Trotsky’s and Stalin’s theories became moot.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; MARXISM; SOCIALISM IN ONE

COUNTRY; TROTSKY, LEON DAVIDOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Trotsky, Leon. (1969). The Permanent Revolution. New

York: Pathfinder Press.

C

ARL

A. L

INDEN

PERMANENT REVOLUTION

1165

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

PEROVSKAYA, SOFIA LVOVNA

(1853–1881), Russian revolutionary populist, a

member of the Executive committee of “Narodnaya

Volya” (“People’s Will”), and a direct supervisor of

the murder of emperor Alexander II.

Sofia Perovskaya was born in St. Petersburg to

a noble family; her father was the governor of

St. Petersburg. In 1869 she attended the Alarchin

Women’s Courses in St. Petersburg, where she

founded the self-education study group. At age sev-

enteen, she left home. From 1871 to 1872 she was

one of the organizers of the Tchaikovsky circle. Her

remarkable organizational skills and willpower

never failed to gain her leading positions in vari-

ous revolutionary societies. To prepare for “going

to the people,” she passed a public teacher’s exam

and completed her studies as a doctor’s assistant.

In January 1874 she was arrested and detained for

several months in the Peter and Paul Fortress and

faced the Trial of 193 (1877–1878), but was proven

innocent. She joined the populist organization Zemlya

i Volya (Land and Freedom) and took part in an un-

successful armed attempt to free Ippolit Myshkin,

who was proven guilty at the Trial of 193. Dur-

ing the summer of 1878 she was once again ar-

rested, and exiled to Olonetskaya province, but on

the way there she fled and assumed an illegal sta-

tus. In June 1879 Perovskaya took part in the

Voronezh assembly of Zemlya i Volya, soon after

which the organization split into Narodnaya Volya

(People’s Will) and Cherny Peredel (The Black Repar-

tition). From the autumn of 1879, she was a mem-

ber of the executive committee of Narodnaya

Volya. In November 1879 she took part in the or-

ganization of the attempt to blow up the tsar’s

train near Moscow. She played the role of the wife

of railroad inspector Sukhorukov (Narodnaya

Volya member Lev Gartman): The underground

tunnel that led to the railroad tracks where the

bomb was planted came from his house. By mis-

take, however, it was the train of the tsar’s en-

tourage that got blown up. During the spring of

1880, Perovskaya took part in another attempt

to kill the tsar in Odessa. In the preparation of

the successful attempt on March 13, 1881, on

the Yekaterininsky channel in St. Petersburg, she

headed a watching squad, and after the party leader

Andrei Zhelyabov (Perovskaya’s lover) was ar-

rested, she headed the operation until it was com-

pleted, having personally drawn the plan of the

positions of the grenade throwers and given the

signal to attack. Hoping to free her arrested com-

rades, after the murder Perovskaya did not leave

St. Petersburg and was herself arrested. At the trial

of pervomartovtsy (participants of the murder of the

tsar), Perovskaya was sentenced to death and

hanged on April 15, 1881, on the Semenovsky pa-

rade ground in St. Petersburg, becoming the first

woman in Russia to be executed for a political

crime.

See also: ALEXANDER II; LAND AND FREEDOM PARTY; PEO-

PLE’S WILL, THE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Figner, Vera. (1927). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. New

York: International Publishers.

Footman, David. (1968). Red Prelude: A Life of A.I.

Zhelyabov. London: Barrie & Rockliff .

Venturi, Franco. (1983). Roots of revolution: A History of

the Populist and Socialist Movements in Nineteenth-

Century Russia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

O

LEG

B

UDNITSKII

PERSIAN GULF WAR

The Persian Gulf War of 1990 and 1991 began as

the high point of Soviet-American cooperation in

the postwar period. However, by late December

1990, a chilling of Soviet-American relations had

set in as Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev sought to

play both sides of the conflict, only to have the

USSR suffer a major political defeat once the war

came to an end.

Following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in Au-

gust 1990, Soviet foreign minister Eduard She-

vardnadze joined U.S. secretary of state James

Baker in severely condemning the Iraqi action, and

the United States and USSR jointly supported nu-

merous U.N. Security Council Resolutions demand-

ing an Iraqi withdrawal and imposing sanctions on

Iraq for its behavior.

Nonetheless, while supporting the United States

(although not committing Soviet forces to battle),

Gorbachev also sought to play a mediating role be-

tween Iraq and the United States, in part to salvage

Moscow’s important economic interests in that

country (oil drilling, oil exploration, hydroelectric

projects, and grain elevator construction, as well as

lucrative arms sales), and in part to bolster his po-

litical flank against those on the right of the Soviet

PEROVSKAYA, SOFIA LVOVNA

1166

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

political spectrum (many of whom were later to

stage an abortive coup against him in August

1991), who were complaining that Moscow had

“sold out” Iraq, a traditional ally of the USSR and

one with which Moscow had been linked by a

Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation since 1972.

Responding to these pressures, Gorbachev twice

sent a senior Soviet Middle East Expert, Yevgeny

Primakov, to Iraq to try to mediate on Iraqi with-

drawal from Kuwait, albeit to no avail. Instead, the

Soviet specialists working in Iraq were swiftly

taken hostage in advance of the January 15, 1991,

United Nations deadline for an Iraqi withdrawal.

In late December 1990, as it became more and

more apparent that the U.S.-led coalition would be-

gin its attack against Iraq on January 15, She-

vardnadze suddenly resigned as Soviet foreign

minister in the face of mounting pressure from So-

viet right-wing forces. His replacement, Alexander

Bessmertnykh, was far less pro-U.S., and his re-

marks utilized the old Soviet jargon of “balance of

power” rather than Gorbachev’s “balance of inter-

ests” terminology. Nonetheless, this did not inhibit

the coalition attack on Iraq that took place on Jan-

uary 15 and that thoroughly defeated Saddam

Hussein’s forces and drove them out of Kuwait by

the end of February 1991. Gorbachev’s behavior

during the fighting, as he sought the best possible

deal for Hussein from the United States, resembled

that of a trial lawyer seeking to plea bargain for

his client under increasingly negative conditions.

This was particularly evident in his peace plan of

February 21, which provided for a lifting of sanc-

tions against Iraq before it had fully withdrawn its

troops from Kuwait. The United States, however,

neither accepted Gorbachev’s entreaties nor paid

much attention to the increasingly hostile warn-

ings of Soviet generals as U.S. troops advanced.

By the time the war ended, Washington had

emerged as the dominant power in the Middle East,

while the USSR lost much of its influence both in

the Middle East and in the world. After the war,

the United States consolidated its military position

in the Persian Gulf and reinforced its relations with

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the other members of

the Gulf Cooperation Council, while Moscow sat

on the diplomatic sidelines.

Given Moscow’s diminished position in the re-

gion and in the world as a whole after the Gulf

War, Gorbachev tried to salvage the USSR’s pres-

tige to the greatest degree possible. Thus, besides

trying to reinforce relations with Iran, he sought

to retain a modicum of influence in Iraq by op-

posing U.N. intervention following the postwar

massacres of Iraqi Shiites and Kurds by Hussein’s

forces. Primakov, whose influence in the Russian

government was rising, stated that he believed Hus-

sein “has sufficient potential to give us hope for a

positive development of relations with him.”

Nonetheless, Gorbachev’s attempts to protect

Hussein availed him little. Less than a year after

the end of the Gulf War, the USSR collapsed, and

Gorbachev fell from power.

See also: IRAQ, RELATIONS WITH; UNITED STATES, RELA-

TIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beschloss, Michael R., and Talbott, Strobe. (1993). At the

Highest Levels: The Inside Story of the End of the Cold

War. Boston: Little, Brown.

Freedman, Robert O. (2001). Russian Policy Toward the

Middle East Since the Collapse of the Soviet Union: The

Yeltsin Legacy and the Challenge for Putin (Donald W.

Treadgold Papers in Russian, East European, and Cen-

tral Asian Studies, no. 33). Seattle: University of

Washington: Henry M. Jackson School of Interna-

tional Studies.

Nizamedden, Talal. (1999). Russia and the Middle East.

New York: St. Martins.

Rumer, Eugene. (2000). Dangerous Drift: Russia’s Middle

East Policy. Washington, DC: Washington Institute

for Near East Policy.

Shaffer, Brenda. (2001). Partners in Need: The Strategic Re-

lationship of Russia and Iran. Washington, DC:

Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Vassiliev, Alexei. (1993). Russian Policy in the Middle East:

From Messianism to Pragmatism. Reading, UK: Ithaca

Press.

R

OBERT

O. F

REEDMAN

PESTEL, PAVEL IVANOVICH

(1793–1826), a leader of the Decembrist movement.

Pavel Ivanovich Pestel, the son of Ivan Boriso-

vich Pestel and Elisaveta Ivanovna von Krok, was

born in Moscow into a family of German and

Lutheran background. He was sent to Dresden at

the age of twelve to be educated, and on his return

four years later he joined the Corps of Pages in St.

Petersburg, where he began to study political sci-

ence. On graduating Pestel entered the army and in

PESTEL, PAVEL IVANOVICH

1167

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

time joined several secret societies. The most im-

portant of these was the Society of Salvation,

founded in 1817 and later renamed the Society of

Welfare. Several of Pestel’s fellow officers had been

in Paris and Western Europe during the war against

Napoleon, and from them he became familiar with

the ideas of the French Revolution. Transferred to

the southern Russia in 1818, Pestel organized a lo-

cal branch of the Society of Welfare, where he and

his friends discussed such ideas as constitutional

monarchy and republican government, as well as

the means by which the imperial family might be

coerced into accepting the former or made to abdi-

cate in favor of the latter.

Pestel left two unfinished works, Russkaia

Pravda (Russian Truth) and Prakticheskie nachala

politicheskoy ekonomy (Practical Principles of Political

Economy). The first outlines a program for political

reform in Russia; the second, a rambling essay on

economics, expresses admiration for the prosperity

made possible by political freedom in the United

States. Pestel’s ideas, especially in their tendency to

favor radical solutions to the problem of Russia’s

political backwardness, relied heavily on the ideas

of the French writer Antoine Louis Claude Destutt

de Tracy, but they had other French and German

sources as well.

When Alexander I died in December 1825 there

was some confusion about the succession. There

was also confusion among those who were plot-

ting a revolt. The more radical revolutionaries were

in the south under Pestel’s leadership. Betrayed by

informants in the Southern Society, Pestel was ar-

rested on December 13, the same day that three

thousand soldiers demonstrated in Senate Square in

St. Petersburg on behalf of Alexander I’s brother,

Constantine, who had already given up his claim

to the throne in favor of his brother, Nicholas. Pes-

tel’s colleague Sergei Muraviev-Apostol attempted

to lead a revolt, but it was crushed by imperial

troops. Pestel was found guilty of treason and ex-

ecuted in 1826 with four of his fellow revolution-

aries, Muraviev-Apostol, Peter Kakhovsky, Mikhail

Bestuzhev-Ryumin, and Kondraty Ryleyev.

See also: DECEMBRIST MOVEMENT AND REBELLION;

RYLEYEV, KONDRATY FYODOROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mazour, Anatole G. (1937). The First Russian Revolution,

1825: The Decembrist Movement: Its Origins, Develop-

ment, and Significance. Stanford, CA: Stanford Uni-

versity Press.

Walsh, Warren B. (1968). Russia and the Soviet Union: A

Modern History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan

Press.

P

AUL

C

REGO

PETER I

(1672–1725), known as Peter the Great, tsar and

emperor of Russia, 1682–1725.

The reign of Peter I is generally regarded as a

watershed in Russian history, during which Rus-

sia expanded westward, became a leading player in

European affairs, and underwent major reforms of

its government, economy, religious affairs, and

culture. Peter is regarded as a “modernizer” or

“westernizer,” who forced changes upon his often

reluctant subjects. In 1846 the Russian historian

Nikolai Pogodin wrote: “The Russia of today, that

is to say, European Russia, diplomatic, political,

military, commercial, industrial, scholastic, literary—

is the creation of Peter the Great. Everywhere we

look, we encounter this colossal figure, who casts

a long shadow over our entire past.” Writers be-

fore and after agreed that Peter made a mark on

the course of Russian history, although there has

always been disagreement about whether his in-

fluence was positive or negative.

CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH

The only son of the second marriage of Tsar Alexei

Mikhailovich of Russia (r. 1645–1676) to Nathalie

Kirillovna Naryshkina, Peter succeeded his half-

brother Tsar Fyodor Alexeyevich (1676–1682) in

May 1682. In June, following the bloody rebellion

of the Moscow musketeers, in which members of

his mother’s family and government officials were

massacred, he was crowned second tsar jointly

with his elder, but severely handicapped, half-

brother Ivan V. Kept out of government during the

regency of his half-sister Sophia Alexeyevna (r.

1682–1689), Peter pursued personal interests that

later fed into his public activities; these included

meeting foreigners, learning to sail, and forming

“play” troops under the command of foreign offi-

cers, which became the Preobrazhensky and Se-

menovsky guards. On Tsar Ivan’s death in 1696,

Peter found himself sole ruler and enjoyed his first

military victory, the capture of the Turkish fortress

at Azov, a success which was facilitated by a newly

created fleet on the Don river. From 1697 to 1698

he made an unprecedented tour of Western Europe

PETER I

1168

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

with the Grand Embassy, the official aim of which

was to revive the Holy League against the Ot-

tomans, which Russia had entered in 1686. Peter

traveled incognito, devoting much of his time to

visiting major sites and institutions in his search

for knowledge. He was particularly impressed with

the Dutch Republic and England, where he studied

shipbuilding. On his return, he forced his boyars

to shave off their beards and adopt Western dress.

In 1700 he discarded the old Byzantine creation cal-

endar in favor of dating years in the Western man-

ner from the birth of Christ. These symbolic acts

set the agenda for cultural change.

THE GREAT NORTHERN

WAR, 1700–1721

After making peace with the Ottoman Empire in

1700, Peter declared war on Sweden with the aim

of regaining a foothold on the Baltic, in alliance

with Denmark and King Augustus II of Poland. Af-

ter some early defeats, notably at Narva in 1700,

and the loss of its allies, Russia eventually gained

the upper hand over the Swedes. After Narva, King

Charles XII abandoned his Russian campaign to

pursue Augustus into Poland and Saxony, allowing

Russia to advance in Ingria and Livonia. When he

eventually invaded Russia via Ukraine in 1707–1708,

Charles found his troops overextended, under-

provisioned, and confronted by a much improved

Russian army. Victory at Poltava in Ukraine in

1709 allowed Peter to stage a successful assault on

Sweden’s eastern Baltic ports, including Viborg,

Riga, and Reval (Tallinn) in 1710. Defeat by the

Turks on the river Pruth in 1711 forced him to re-

turn Azov (ratified in the 1713 Treaty of Adri-

anople), but did not prevent him pursuing the

Swedish war both at the negotiating table and on

campaign, for instance, in Finland in 1713–1714

and against Sweden’s remaining possessions in

northern Germany and the Swedish mainland. The

Treaty of Nystadt (1721) ratified Russian posses-

sion of Livonia, Estonia, and Ingria. During the cel-

ebrations the Senate awarded Peter the titles

Emperor, the Great, and Father of the Fatherland.

In 1722–1723 Peter conducted a campaign against

Persia on the Caspian, capturing the ports of Baku

and Derbent. Russia’s military successes were

achieved chiefly by intensive recruitment, which al-

lowed Peter to keep armies in the field over several

decades; training by foreign officers; home pro-

duction of weapons, especially artillery; and well-

organized provisioning. The task was made easier

by the availability of a servile peasant population

and the obstacles which the Russian terrain and cli-

mate posed for the invading Swedes. The navy,

staffed mainly by foreign officers on both home-

built and purchased ships, provided an auxiliary

force in the latter stages of the Northern War, al-

though Peter’s personal involvement in naval af-

fairs has led some historians to exaggerate the

fleet’s importance. The galley fleet was particularly

effective, as exemplified at Hango in 1714.

DOMESTIC REFORMS

Many historians have argued that the demands of

war were the driving force behind all Peter’s re-

forms. He created the Senate in 1711, for example,

to rule in his absence during the Turkish campaign.

Among the ten new Swedish-inspired government

departments, created between 1717 and 1720 and

known as Colleges or collegiate boards, the Colleges

of War, Admiralty, and Foreign Affairs consumed

the bulk of state revenues, while the Colleges of

PETER I

1169

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

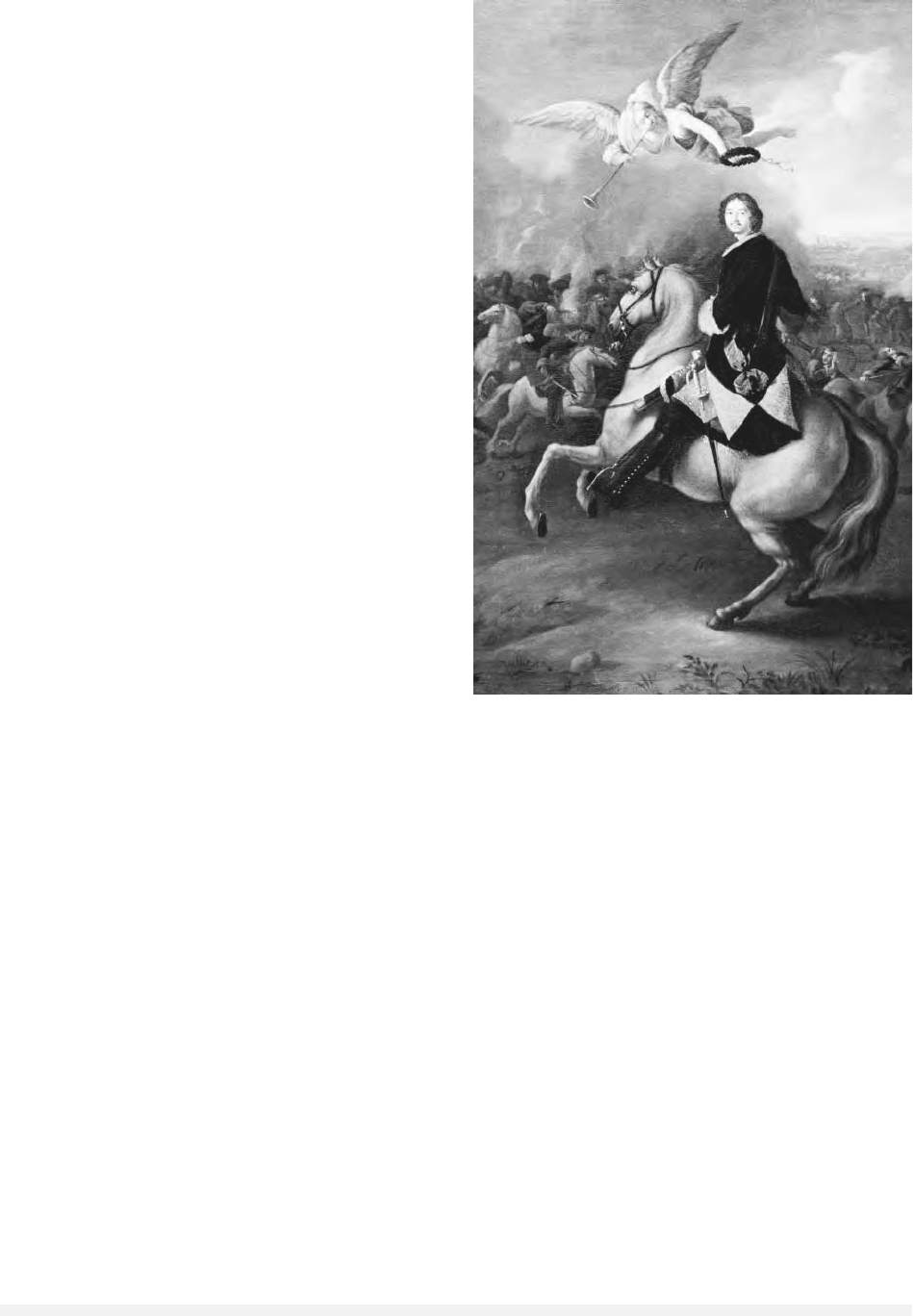

Peter I in battle at Poltava. © T

HE

S

TATE

R

USSIAN

M

USEUM

/CORBIS

Mines and Manufacturing concentrated on pro-

duction for the war effort, operating iron works

and manufacture of weapons, rope, canvas, uni-

forms, powder, and other products. The state re-

mained the chief producer and customer, but Peter

attempted to encourage individual enterprise by of-

fering subsidies and exemptions. Free manpower

was short, however, and in 1721 industrialists

were allowed to purchase serfs for their factories.

New provincial institutions, based on Swedish

models and created in several restructuring pro-

grams, notably in 1708–1709 and 1718–1719, were

intended to rationalize recruitment and tax collec-

tion, but were among the least successful of Peter’s

projects. As he said, money was the “artery of

war.” A number of piecemeal fiscal measures cul-

minated in 1724 with the introduction of the poll

tax (initially 74 kopecks per annum), which re-

placed direct taxation based on households with as-

sessment of individual males. Peter also encouraged

foreign trade and diversified indirect taxes, which

were attached to such items and services as official

paper for contracts, private bathhouses, oak coffins,

and beards (the 1705 beard tax). Duties from liquor,

customs, and salt were profitable.

The Table of Ranks (1722) consolidated earlier

legislation by dividing the service elite—army and

navy officers, government and court officials—into

three columns of fourteen ranks, each containing

a variable number of posts. No post was supposed

to be allocated to any candidate who was unqual-

ified for the duties involved, but birth and marriage

continued to confer privilege at court. The Table

was intended to encourage the existing nobility to

perform more efficiently, while endorsing the con-

cept of nobles as natural leaders of society: Any

commoner who attained the lowest military rank—

grade 14—or civil grade 8 was granted noble sta-

tus, including the right to pass it to his children.

Peter’s educational reforms, too, were utilitar-

ian in focus, as was his publishing program, which

focused on such topics as shipbuilding, navigation,

architecture, warfare, geography, and history. He

introduced a new simplified alphabet, the so-called

civil script, for printing secular works. The best-

known and most successful of Peter’s technical

schools was the Moscow School of Mathematics

and Navigation (1701; from 1715, the St. Peters-

burg Naval Academy), which was run by British

teachers. Its graduates were sent to teach in the so-

called cipher or arithmetic schools (1714), but these

failed to attract pupils. Priests and church schools

continued to be the main suppliers of primary ed-

ucation, and religious books continued to sell bet-

ter than secular ones. The Academy of Sciences is

generally regarded as the major achievement, al-

though it did not open until 1726 and was initially

staffed entirely by foreigners. In Russia, as else-

where, children in rural communities, where child

labor was vital to the economy, remained unedu-

cated.

THE CHURCH

The desire to deploy scarce resources as rationally

as possible guided Peter’s treatment of the Ortho-

dox Church. He abolished the patriarchate, which

was left vacant when the last Patriarch died in

1700, and in 1721 replaced it with the Holy Synod,

which was based on the collegiate principle and

later overseen by a secular official, the Over-

Procurator. The Synod’s rationale and program

were set out in the Spiritual Regulation (1721). Pe-

ter siphoned off church funds as required, but he

stopped short of secularizing church lands. He

slimmed down the priesthood by redeploying su-

perfluous clergymen into state service and restrict-

ing entry into monasteries, which he regarded as

refuges for shirkers. Remaining churchmen accu-

mulated various civic duties, such as keeping reg-

isters of births and deaths, running schools and

hospitals, and publicizing government decrees.

These measures continued seventeenth-century

trends in reducing the church’s independent power,

but Peter went farther by reducing its role in cul-

tural life. Himself a dutiful Orthodox Christian

who attended church regularly, he was happy for

the Church to take responsibility for the saving of

men’s souls, but not for it to rule their lives. His

reforms were supported by educated churchmen

imported from Ukraine.

ST. PETERSBURG AND

THE NEW CULTURE

The city of St. Petersburg began as an island fort

at the mouth of the Neva river on land captured

from the Swedes in 1703. From about 1712 it came

to be regarded as the capital. In Russia’s battle for

international recognition, St. Petersburg was much

more than a useful naval base and port. It was a

clean sheet on which Peter could construct a mi-

crocosm of his New Russia. The Western designs

and decoration of palaces, government buildings,

and churches, built in stone by hired foreign ar-

chitects according to a rational plan, and the Eu-

ropean fashions that all Russian townspeople were

forced to wear, were calculated to make foreigners

PETER I

1170

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

feel that they were in Europe rather than in Asia.

The city became a “great window recently opened

in the north through which Russia looks on Eu-

rope” (Francesco Algarotti, 1739). Peter often re-

ferred to it as his “paradise,” playing on the

associations with St. Peter as well as expressing his

personal delight in a city built on water. The cen-

tral public spaces enjoyed amenities such as street

lighting and paving and public welfare was super-

vised by the Chief of Police, although conditions

were less salubrious in the backstreets. Nobles re-

sented being uprooted from Moscow to this glori-

fied building site. Noblewomen were not exempt.

They were wrenched from their previously shel-

tered lives in the semi-secluded women’s quarters

or terem and ordered to abandon their modest,

loose robes and veils in favor of Western low cut

gowns and corsets and to socialize and drink with

men. Some historians have referred to the “eman-

cipation” of women under Peter, but it is doubtful

whether this was the view of those involved.

PETER’S VISION AND METHODS

Peter was an absolute ruler, whose great height (six

foot seven inches) and explosive temper must have

intimidated those close to him. His portraits, the first

thoroughly Westernized Russian images painted or

sculpted from life, were embellished with Imperial

Roman, allegorical, military, and naval motifs to

underline his power. Yet he sought to deflect his

subjects’ loyalty from himself to the state, exhort-

ing them to work for the common good. A doer

rather than a thinker, he lacked formal education

and the patience for theorizing. Soviet historians

favored the image of the Tsar-Carpenter, empha-

sizing the fourteen trades that Peter mastered, of

which his favorites were shipbuilding and wood

turning. He also occasionally practiced dentistry

and surgery. Ironically, Peter often behaved in a

manner that confirmed foreign prejudices that Rus-

sia was a barbaric country. Abroad he frequently

offended his hosts with his appalling manners,

while Western visitors to Russia were perplexed by

his court, which featured dwarfs, giants, and

human “monsters” (from his Cabinet of Curiosi-

ties), compulsory drinking sessions, which armed

guards prevented guests prevented from leaving,

and weird ceremonies staged by the “All-Mad,

All-Jesting, All-Drunken Assembly,” which, headed

by the Prince-Pope, parodied religious rituals.

Throughout his life Peter maintained a mock court

headed by a mock tsar known as Prince Caesar,

who conferred promotions on “Peter Mikhailov” or

“Peter Alexeyev,” as Peter liked to be known as he

worked his way through the ranks of the army

and navy.

One of the functions of Peter’s mock institu-

tions was to ridicule the old ways. Peter constantly

lamented his subjects’ reluctance to improve them-

selves on their own initiative. As he wrote in an

edict of 1721 to replace sickles with more efficient

scythes: “Even though something may be good, if

it is new our people will not do it.” He therefore

resorted to force. In Russia, where serfdom was

made law as recently as 1649, the idea of a servile

population was not new, but under Peter servitude

was extended and intensified. The army and navy

swallowed up tens of thousands of men. State peas-

ants were increasingly requisitioned to work on

major projects. Previously free persons were trans-

ferred to the status of serfs during the introduc-

tion of the poll tax. Peter also believed in the power

of rules, regulations, and statutes, devised “in or-

der that everyone knows his duties and no one ex-

cuses himself on the grounds of ignorance.” In

1720, for example, he issued the General Regula-

tion, a “regulation of regulations” for the new gov-

ernment apparatus. Not only the peasants, but also

the nobles, found life burdensome. They were

forced to serve for life and to educate their sons for

service.

ASSOCIATES AND OPPONENTS

Despite his harsh methods, Peter was supported by

a number of men, drawn from both the old Mus-

covite elite and from outside it. The most prominent

of the newcomers were his favorite, the talented

and corrupt Alexander Menshikov (1673–1729),

whom he made a prince, and Paul Yaguzhinsky,

who became the first Procurator-General. Top men

from the traditional elite included General Boris

Sheremetev, Chancellor Gavrila Golovkin, Admiral

Fyodor Apraksin and Prince Fyodor Romodanov-

sky. The chief publicist was the Ukrainian church-

man Feofan Prokopovich. It is a misconception that

Peter relied on foreigners and commoners.

Religious traditionalists abhorred Peter, identi-

fying him as the Antichrist. The several revolts of

his reign all included some elements of antagonism

toward foreigners and foreign innovations such as

shaving and Western dress, along with more stan-

dard and substantive complaints about the en-

croachment of central authority, high taxes, poor

conditions of service, and remuneration. The most

serious were the musketeer revolt of 1698, the As-

trakhan revolt of 1705, and the rebellion led by the

PETER I

1171

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Don Cossack Ivan Bulavin in 1707–1708. The dis-

ruption that worried Peter most, however, affected

his inner circle. Peter was married twice: in 1689 to

the noblewoman Yevdokia Lopukhina, whom he

banished to a convent in 1699, and in 1712 to

Catherine, a former servant girl from Livonia whom

he met around 1703. He groomed the surviving son

of his first marriage, Alexei Petrovich (1690–1718),

as his successor, but they had a troubled relation-

ship. In 1716 Alexei fled abroad. Lured back to Rus-

sia in 1718, he was tried and condemned to death

for treason, based on unfounded charges of a plot

to assassinate his father. Many of Alexei’s associ-

ates were executed, and people in leading circles were

suspected of sympathy for him. Peter and Cather-

ine had at least ten children (the precise number is

unknown), but only two girls reached maturity:

Anna and Elizabeth (who reigned as empress from

1741 to 1761). In 1722 Peter issued a new Law of

Succession by which the reigning monarch nomi-

nated his own successor, but he failed to record his

choice before his death (from a bladder infection) in

February (January O.S.) 1725. Immediately after

Peter’s death, Menshikov and some leading courtiers

with guards’ support backed Peter’s widow, who

reigned as Catherine I (1725–1727).

VIEWS OF PETER AND HIS REFORMS

The official view in the eighteenth century and

much of the nineteenth was that Peter had “given

birth” to Russia, transforming it from “non-

existence” into “being.” Poets represented him as

Godlike. The man and his methods were easily ac-

commodated in later eighteenth-century discourses

of Enlightened Absolutism. Even during Peter’s life-

time, however, questions were raised about the

heavy cost of his schemes and the dangers of aban-

doning native culture and institutions. As the Russ-

ian historian Nikolai Karamzin commented in

1810: “Truly, St. Petersburg is founded on tears

and corpses.” He believed that Peter had made Rus-

sians citizens of the world, but prevented them

from being Russians. Hatred of St. Petersburg as a

symbol of alien traditions was an important ele-

ment in the attitude of nineteenth-century Slavo-

philes, who believed that only the peasants had

retained Russian cultural values. To their Western-

izer opponents, however, Peter’s reforms, stopping

short of Western freedoms, had not gone far

enough. In the later nineteenth century, serious

studies of seventeenth-century Muscovy ques-

tioned the revolutionary nature of Peter’s reign,

underlining that many of Peter’s reforms and poli-

cies, such as hiring foreigners, reforming the army,

and borrowing Western culture, originated with

his predecessors. The last tsars, especially Nicholas

II, took a nostalgic view of pre-Petrine Russia, but

Petrine values were revered by the imperial court

until its demise.

Soviet historians generally took a bipolar view

of Peter’s reign. On the one hand, they believed that

Russia had to catch up with the West, whatever the

cost; hence they regarded institutional and cultural

reforms, the new army, navy, factories, and so

on as “progressive.” Territorial expansion was ap-

proved. On the other hand, Soviet historians were

bound to denounce Peter’s exploitation of the peas-

antry and to praise popular rebels such as Bulavin;

moreover, under Stalin, Peter’s cosmopolitanism

was treated with suspicion. Cultural historians in

particular stressed native achievements over foreign

borrowings. In the 1980s–1990s some began to

take a more negative view still, characterizing Pe-

ter as “the creator of the administrative-command

system and the true ancestor of Stalin” (Anisimov,

1993). After the collapse of the USSR, the secession

of parts of the former Empire and Union, and the

decline of the armed forces and navy, many people

looked back to Peter’s reign as a time when Russia

was strong and to Peter as an ideal example of a

strong leader. The debate continues.

See also: ALEXEI PETROVICH; CATHERINE I; ELIZABETH;

FYODOR ALEXEYEVICH; MENSHIKOV, ALEXANDER

DANILOVICH; PATRIARCHATE; PEASANTRY; SERFDOM;

ST. PETERSBURG; TABLE OF RANKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, M. S. (1995). Peter the Great. London: Long-

man.

Anisimov, E. V. (1993). Progress through Coercion: The Re-

forms of Peter the Great. New York: M. E. Sharpe.

Bushkovitch, Paul. (2001). Peter the Great: The Struggle

for Power, 1671–1725. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Canadian American Slavic Studies. 8 (1974). Issue devoted

to Peter’s reign.

Cracraft, James. (1971). The Church Reform of Peter the

Great. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cracraft, James. (1990). The Petrine Revolution in Russian

Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cracraft, James. (1997). The Petrine Revolution in Russian

Imagery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the

Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

PETER I

1172

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY