Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Hughes, Lindsey, ed. (2000). Peter the Great and the West:

New Perspectives. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Hughes, Lindsey. (2002). Peter the Great: A Biography.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kliuchevsky, Vasily. (1958). Peter the Great, tr. L.

Archibald. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Pososhkov, Ivan. (1987). The Book of Poverty and Wealth,

ed., tr. A. P. Vlasto, L. R. Lewitter. London: The

Athlone Press.

Raeff, Marc. ed. (1972). Peter the Great Changes Russia.

Lexington, MA: Heath.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas. (1984). The Image of Peter the

Great in Russian History and Thought. Oxford: Ox-

ford University Press.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

PETER II

(1715–1730), emperor of Russia, May 1727 to Jan-

uary 1730.

Son of Tsarevich Alexis Petrovich and Princess

Charlotte of Wolfenbüttel, and grandson of Peter I,

the future Peter II had an unfortunate start in life.

His German mother died soon after his birth, and

in 1718 his father died in prison after being tor-

tured and condemned to death for treason. Peter I

did not mistreat his grandson, but feared him as a

possible rallying point for conservatives. He did not

groom him as his heir, and a new Law on Succes-

sion (1722) rejected primogeniture and made it pos-

sible for the ruler to nominate his successor. During

the reign of his step-grandmother, Catherine I

(1725–1727), young Peter found himself under the

protection of Prince Alexander Menshikov, who be-

trothed him to his daughter Maria and persuaded

Catherine to name him as her successor, in the hope

of stealing ground from the old nobility and gain-

ing popularity by restoring the male line. On the

day of Catherine’s death, Peter was proclaimed em-

peror.

For the rest of Peter’s short life it was a ques-

tion of who could manipulate him before he de-

veloped a mind of his own. At first Menshikov kept

the emperor under his wing, but, following a bout

of illness in the summer of 1727, Menshikov was

marginalized then banished by members of the

powerful Dolgoruky clan, backed by the emperor’s

grandmother, Peter I’s ex-wife Yevdokia. Peter II

was crowned in Moscow on March 8 (February 25

O.S.), 1728. His chief adviser was now Prince Alexis

Grigorevich Dolgoruky, but the power behind the

government was Heinrich Osterman. Both men

were members of the Supreme Privy Council. Af-

ter his coronation Peter stayed in Moscow, where

he devoted much of his time to hunting. Portraits

show a handsome boy dressed in the latest West-

ern fashion. His short reign has sometimes been as-

sociated with a move to reject many of Peter’s

reforms, but there is no evidence that Peter II or his

circle planned to return to the old ways, even if

magnates welcomed the opportunity to spend more

time on their Moscow estates. According to one

source, young Peter wished to “follow in the steps

of his grandfather.” He did not get the chance. In

fall 1729 he was betrothed to Prince Dolgoruky’s

daughter Catherine, but the wedding never took

place. On January 29 (January 18 O.S.), 1730, he

died from smallpox, without nominating a succes-

sor. The last of the Romanov male line, he was

buried in the Archangel Cathedral in Moscow.

See also: CATHERINE I; MENSHIKOV, ALEXANDER

DANILOVICH; ROMANOV DYNASTY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Raleigh, D. J. (1996). The Emperors and Empresses of Rus-

sia: Rediscovering the Romanovs. Armonk, NY: M. E.

Sharpe.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

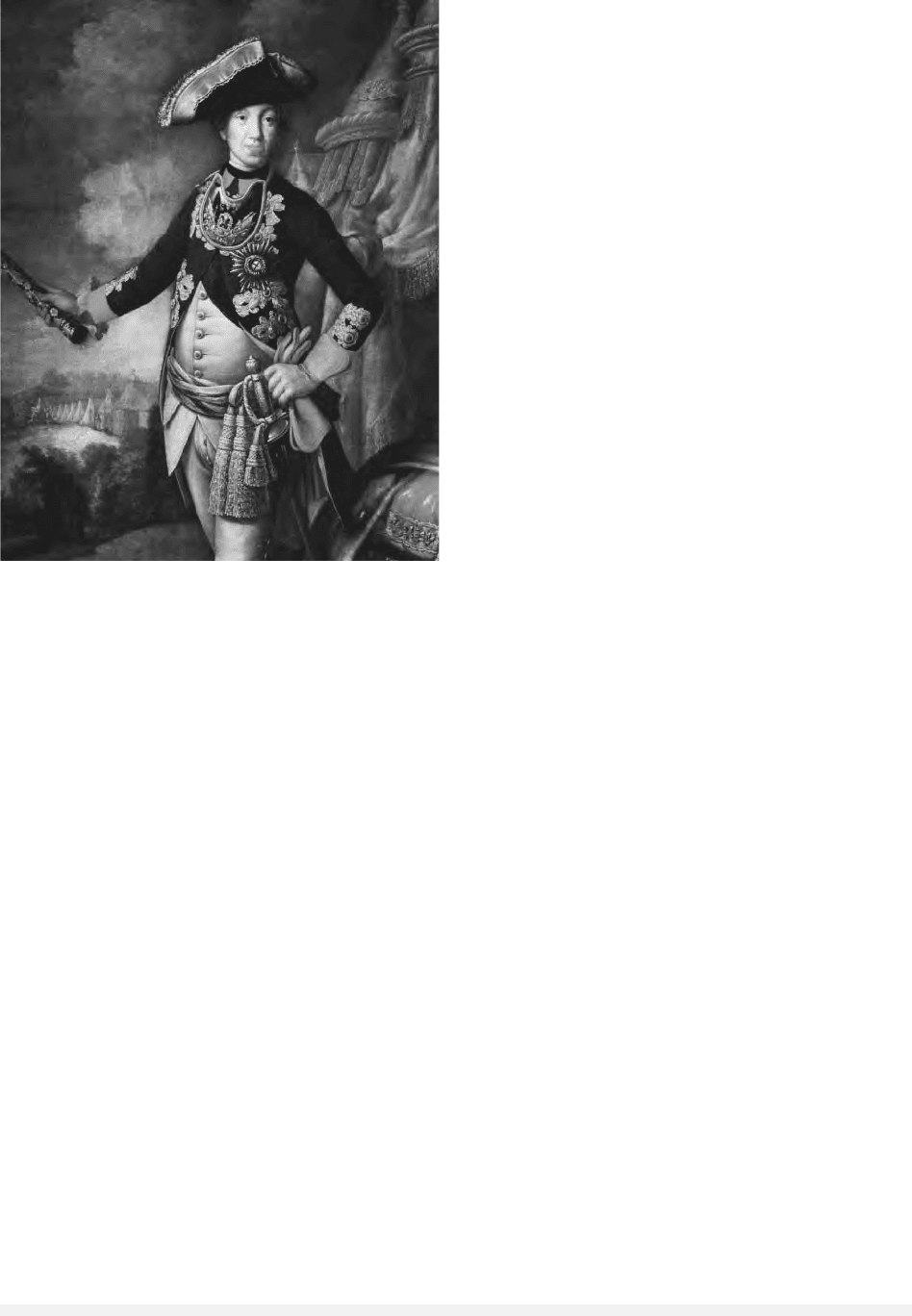

PETER III

(1728–1762), emperor of Russia, January 5, 1762,

to July 9, 1762.

The future Peter III was born Karl Peter Ulrich

in Kiel, Germany, in February 1728, the son of the

duke of Holstein and Peter I’s daughter Anna Petro-

vna, who died shortly after his birth. His paternal

grandmother was a sister of Charles XII of Swe-

den; this relation gave him a claim to the Swedish

throne. In 1742 his aunt, the Empress Elizabeth

(reigned 1741–1762 [1761 O.S.]), brought him to

Russia to be groomed as her heir. Raised a Lutheran

with German as his first language, he received in-

struction in Russian and the Orthodox religion, to

which he converted. In 1745 he was married to the

fifteen-year-old German Princess Sophia of Anhalt

Zerbst, the future Catherine II (“the Great”). On

Christmas Day 1761 (O.S.), Elizabeth died, and Pe-

ter succeeded her.

PETER III

1173

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Catherine II’s Memoirs drew a bleak picture of

her marriage, recording bizarre details of Peter

court-martialing rats, bringing hunting dogs to

bed, and spying on Empress Elizabeth through a

hole in the wall. Moreover, she hinted strongly that

the marriage was never consummated and that her

first child, the future Emperor Paul (born 1754),

was in fact the son of her lover. Peter was an “ab-

surd husband,” in fact, not a husband at all. Con-

temporary accounts corroborate the essence, if not

all the details, of Catherine’s portrait of her hus-

band. Peter seems to have been immature, impul-

sive, and unpredictable. He had a keen interest in

military affairs, particularly drill and fortification,

and played the violin quite well, but he also loved

dolls and puppets and enjoyed crude practical jokes

and drinking. Surviving portraits indicate an un-

prepossessing appearance.

But a ruler has never been denied his rightful

throne merely on account of being “absurd,” child-

like, and plain. On the contrary, powerful courtiers

could easily accommodate and even welcomed such

monarchs. Although Peter brought a number of Ger-

mans from Holstein into his council, influential fig-

ures from Elizabeth’s regime such as D. V. Volkov,

A. I. Glebov, and members of the Vorontsov clan

remained powerful. There was even some support

for Peter’s controversial personal decision to make

peace with Prussia, “out of compassion for suffer-

ing humanity and personal friendship toward the

King of Prussia.” The treaty of May 5 (April 24

O.S.) 1762 restored all the territories taken by Rus-

sia during the Seven Years War. Peace triggered

Peter’s most famous edict, the manifesto releasing

the Russian nobility from compulsory state service,

issued on February 29 (February 8 O.S.), 1762,

which Peter himself probably played little part in

drafting. With the prospect of many officers re-

turning from active service, it suited the govern-

ment to save salaries and re-deploy personnel. The

manifesto declared that compulsory service was

no longed needed, because “useful knowledge and

assiduity in service have increased the number of

skillful and brave generals in military affairs, and

have put informed and suitable people in civil and

political affairs.” But this was not an invitation to

wholesale desertion. There were restrictions on im-

mediate release: Nobles must educate their sons

and, on receipt of the monarch’s personal decree,

rally to service. Those who had never served were

to be “despised and scorned” at court.

Other measures issued during Peter’s short

reign included a reduction in the salt tax, a tem-

porary ban on the purchase of serfs for factories,

and some easing of restrictions on peasants enter-

ing and trading in towns. Sanctions were lifted on

Old Believers who had fled into Poland. The Secret

Chancery was abolished and some of its functions

transferred to the Senate. In fulfillment of a deci-

sion already made under Elizabeth, the two million

peasants on church estates were transferred to the

jurisdiction of the state College of Economy, a mea-

sure that did not constitute liberation but was re-

garded as an improvement in the peasants’ status.

In conjunction with the emancipation of the no-

bility, this measure increased speculation that Pe-

ter might have been planning to liberate the serfs.

None of these measures saved Peter III. He de-

moted the Senate, thereby alienating some top of-

ficials. Confiscating its peasants alienated the church.

The decision to end the war with Prussia suited

some influential men, but most opposed Peter’s

further plans to win back Schleswig, formerly the

possession of his Holstein ancestors, with Prussian

support. He disbanded the imperial bodyguard, and

there were rumors that he intended to replace the

PETER III

1174

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Emperor Peter III, husband of Catherine the Great. © A

RCHIVO

I

CONOGRAFICO

, S.A./CORBIS

existing guards, now required to wear Prussian uni-

forms, with men from Holstein. His fate was fur-

ther sealed by his alleged contempt for Orthodoxy.

It was rumored that he did not observe fasts and

that he intended to convert Russia to Lutheranism.

Such accusations were exaggerated by Peter’s op-

ponents, who now focused on replacing him with

his more popular wife, who was beginning to fear

for her own safety. On July 5 (June 28 O.S.), 1762,

Catherine seized power with the support of guards

regiments led by her lover Grigory Orlov. “All

unanimously agree that Grand Duke Peter Fyo-

dorovich is incompetent and Russia has nothing to

expect but calamity,” she declared. After vain ef-

forts to rally support, Peter abdicated and was

taken to a residence not far from Peterhof palace.

On July 16 (July 5 O.S.) he died, officially of colic

brought on by hemorrhoids, although rumors

hinted at murder by poison, strangulation, suffo-

cation, beating, or shooting. His escort later ad-

mitted that an “unfortunate scuffle” had occurred,

but nothing was proven and no one charged. Even

if Peter was not killed on Catherine’s explicit or-

ders, his death, while not arousing her regret, of-

ten came back to haunt her.

The somewhat mysterious circumstances of

Peter III’s death and the promising nature of some

of his edicts later made his a popular identity for

a series of pretenders to the throne, culminating in

the Pugachev revolt in 1773 and 1774. Following

Catherine II’s death in 1796, Emperor Paul I, who

never doubted that Peter was his father, had his

parents buried side by side in the Peter and Paul

Cathedral.

See also: CATHERINE II; ELIZABETH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hughes, Lindsey. (1982). “Peter III.” Modern Encyclopedia

of Russian and Soviet History 27:238–244. Gulf

Breeze, FL: Academic International Press.

Jones, Robert, E. (1973). The Emancipation of the Russian

Nobility, 1782–1785. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

Leonard, Carol. (1993). Reform and Regicide: The Reign of

Peter III of Russia. Bloomington: University of Indi-

ana Press.

Madariaga, Isabel de. (1981). Russia in the Age of Cather-

ine the Great. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Raeff, Marc. (1970). “The Domestic Policies of Peter III

and His Overthrow.” American Historical Review

75:1289–1310.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

PETER AND PAUL FORTRESS

The Peter and Paul Fortress was established in May

1703, the third year of the Great Northern War

with Sweden, which would last until 1721. Hav-

ing reduced Swedish positions along the Neva River

from Lake Ladoga, Peter I needed a fortified point

in the Neva estuary to protect Russia’s position on

the Gulf of Finland. Some twenty thousand men

were conscripted to surround the island with

earthen walls and bastions, and by November the

fortress of Sankt Piter Burkh—“Saint Peter’s Burg”—

was essentially completed. It was named in honor

of the Russian Orthodox feast day of Saints Peter

and Paul (June 29).

Peter intended the fortress at the center of his

city to serve not only a military function, but also

as a symbol of his union of state and religious in-

stitutions within a new political order in Russia. To

implement this reformation in the architecture

of Saint Petersburg and its fortress, Dominico

Trezzini, the most productive of the Petrine archi-

tects, capably served Peter. After the completion of

the earthen fortress, Peter ordered a phased re-

building with masonry walls. In May 1706, the

tsar assisted with laying the foundation stone of

the Menshikov Bastion, and for the rest of

Trezzini’s life (until 1734) the design and building

of the Peter-Paul fortress, with its six bastions,

would remain one of his primary duties. The major

sections of the fortress, including the six bastions—

were named either for a leading participant in Pe-

ter’s reign, such as Alexander Menshikov, or for a

member of the imperial house, not excluding Peter

himself.

Within the fortress the dominant feature is the

Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul, designed by

Trezzini in a radical departure from traditional

Russian church architecture. Trezzini created an

elongated structure, whose baroque dome on the

eastern end is subordinate to the tower and spire

over the west entrance. The tower was the focus

of Peter’s interest and had priority over the rest of

the structure, which was not completed until 1732.

By 1723, the spire, gilded and surmounted with an

angel holding a cross, reached a height of 367 feet

(112 meters), which exceeded the bell tower of Ivan

the Great by 105 feet (32 meters).

On the interior, the large windows that mark

the length of the building provide ample illumi-

nation for the banners and other imperial regalia.

It is not clear whether this great hall was origi-

PETER AND PAUL FORTRESS

1175

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

nally intended to serve as a burial place for the

Romanov tsars; but with the death of Peter the Great,

this function was assumed from the Archangel

Cathedral in the Kremlin. The centerpiece of the

interior is the gilded icon screen, designed by Ivan

Zarudnyi and resembling the triumphal arches

erected to celebrate Peter’s victories. The frame

was carved between 1722 and 1726 by craftsmen

in Moscow and assembled in the cathedral in

1727. Some of the cathedral’s ornamentation

was lost after a lightning strike and fire in 1756,

although prompt response by the garrison pre-

served the icon screen and much of the interior

work.

The eighteenth century witnessed the con-

struction of many other administrative and garri-

son buildings within the fortress, including an

enclosed pavilion for Peter’s small boat and the state

Mint. At the turn of the nineteenth century the

fortress became the main political prison of Russia.

Famous cultural and political figures detained there

include Alexander Radishchev, Fyodor Dostoevsky,

and Nikolai Chernyshevsky. In 1917, the garrison

sided with the Bolsheviks and played a role in the

shelling of the Winter Palace. During the early

twenty-first century the fortress serves primarily

as a museum.

See also: MENSHIKOV, ALEXANDER DANILOVICH; PETER I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, William Craft. (1993). A History of Russian

Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hamilton, George Heard. (1975). The Art and Architecture

of Russia. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books.

W

ILLIAM

C

RAFT

B

RUMFIELD

PETER THE GREAT See PETER I.

PETRASHEVSKY, MIKHAIL See BUTASHEVICH-

PETRASHEVSKY, MIKHAIL VASILIEVICH.

PETRASHEVTSY

Given the oppressive power of the state under

Nicholas I and the weakness of civil society in Rus-

sia, the political ferment that rocked Europe dur-

ing the 1840s took the relatively subdued form

of discussion groups meeting secretly in private

homes. The most important of such groups met on

Friday evenings in the St. Petersburg home of a

young official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

Mikhail Butashevich-Petrashevsky, from late 1845

until the group was disbanded by the police in a

wave of repression following the revolutions that

erupted in Western Europe in 1848. More than one

hundred members of the group were arrested and

interrogated, and twenty-one of the leading figures

were condemned to death. In an infamous instance

of psychological torture, on December 22, 1849,

the condemned men were led to the scaffold and

hooded, and the firing squad ordered to shoulder

arms, before an imperial adjutant rode up with a

last-minute reprieve commuting the sentences to

imprisonment or banishment. Among those sent to

Siberia was the novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who

later depicted the members of the group in his novel

The Possessed.

The meetings of the Petrashevtsy, as the police

labeled the men who met in Petrashevsky’s home,

were open to invited guests as well as regular mem-

bers. Thus, over the course of the group’s existence,

several hundred men took part in the discussions.

Some attendees were wealthy landowners or emi-

nent writers or professors, such as the poets Alexei

Pleshcheyev and Apollon Maikov and the econo-

mist V. A. Milyutin. The majority, however, were

of modest means and held middle- or low-ranking

positions in state service or were students or small-

scale merchants. Serious about political ideas, they

amassed a large collection of works in several lan-

guages on political philosophy and economics.

While Petrashevsky himself was committed to the

utopian socialism of Charles Fourier, and socialist

thought was the dominant theme of the discus-

sions, members of the group held a range of ideo-

logical and tactical approaches to the problem of

transforming Russian society. Their most impor-

tant project was the publication in 1845 and 1846

of A Pocket Dictionary of Foreign Terms, an effort to

propagate their ideas through political articles dis-

guised as dictionary entries. The censors eventually

realized the subversive nature of the dictionary and

ordered it confiscated, but not in time to prevent

the sale of part of the second, more radical, edition.

The Petrashevtsy were not opposed in princi-

ple to a violent overthrow of the tsar’s government,

but in practice most saw little hope of a successful

revolution in Russia and therefore advocated par-

tial reforms such as freedom of speech, freedom of

PETER THE GREAT

1176

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

press, and reform of the judicial system. The more

radical members, led by Nikolai Speshnev, hoped to

transform the group into a revolutionary organi-

zation that would prepare the ground for an armed

revolt. Through subsidiary discussion circles that

branched off from the original group, such as the

one to which the novelist Nikolai Chernyshevsky

belonged while a university student, the Petra-

shevtsy played an important role in propagating

socialist ideas in Russia.

See also: CHERNYSHEVSKY, NIKOLAI GAVRILOVICH; DOS-

TOYEVSKY, FYODOR MIKHAILOVICH; NICHOLAS I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Seddon, J. H. (1985). The Petrashevtsy: A Study of the Russ-

ian Revolutionaries of 1848. Manchester, UK: Man-

chester University Press.

Walicki, Andrzej. (1979). A History of Russian Thought:

From the Enlightenment to Marxism. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

K

ATHRYN

W

EATHERSBY

PETROV, GRIGORY SPIRIDONOVICH

(1868–1925), Orthodox priest and a leading pro-

ponent of Christian social activism.

Grigory Petrov was born in Iamburg, St. Pe-

tersburg province. He was educated at the diocesan

seminary and the St. Petersburg Ecclesiastical Acad-

emy (1887–1891), and on graduating became a

priest in a St. Petersburg church.

Petrov was also active as a writer. In his most

successful work, The Gospel as the Foundation of Life

(1898), he argued that Christian believers were re-

quired to apply the literal teachings of Jesus to

every aspect of their lives in order to begin build-

ing the Kingdom of God here on earth. Petrov knew

of the American Social Gospel movement, but his

ideas were shaped by his encounters with new con-

ceptions of pastorship and Christian activism then

developing among the clergy of St. Petersburg.

Petrov’s writings found a ready audience and

made him famous. In 1903, however, conserva-

tives began to attack his ideas in the ecclesiastical

press, and as a result in 1904 the church dismissed

Petrov from his pulpit and banned him from pub-

lic speaking. Nevertheless, Petrov continued to write.

He became interested in Christian politics and was

an activist during the Revolution of 1905. He es-

tablished the newspaper God’s Truth in Moscow in

1906 and was elected to the first Duma as a Con-

stitutional Democrat.

Petrov never served in the Duma, however, be-

cause he was charged before an ecclesiastical court

with false teaching. Although exonerated, he was

confined to a monastery under church discipline.

Despite popular sympathy for Petrov, the church

defrocked him in 1908 and banned him from the

capital and from public employment. He then be-

came a journalist for a liberal newspaper, The Word.

After the revolutions of 1917 he emigrated to Ser-

bia, and then in 1922 to France. He died in Paris in

1925.

Petrov’s main importance was in his contribu-

tion to the development of a modern, liberal un-

derstanding of Christianity in the Russian Orthodox

context.

See also: ORTHODOXY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Valliere, Paul. (1977). “Modes of Social Action in Russ-

ian Orthodoxy: The Case of Father Petrov’s Zateinik.”

Russian History 4(2):142–158.

J

ENNIFER

H

EDDA

PETRUSHKA

Petrushka was a Russian puppet theater spectacle

and also the name of its main character (cf. the

English Punch).

The play Petrushka seems to derive from a na-

tive older Russian buffoon and minstrel tradition

and the Western European puppet theater tradition

with its roots in the Italian commedia dell’arte. Pos-

sible evidence of the Petrushka play in Russia is

found as early as 1637 in an engraving and de-

scription by a Dutch traveler, Adam Olearius. From

around the 1840s to the 1930s, the Petrushka show

was one of the most popular kinds of improvisa-

tional theater in Russia, often performed at fairs

and carnivals and on the streets on a temporary

wooden stage (balagan). The show was presented

by two performers, one of whom manipulated the

puppets, while the other played a barrel-organ.

Recorded textual variants from the nineteenth

PETRUSHKA

1177

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and twentieth centuries depict the adventures of

Petrushka, a dauntless prankster and joker, who

uses his wit as well as a vigorously wielded club

to get the better of his adversaries, who often rep-

resent established authority. The themes tend to be

sexist and violent. Petrushka is usually dressed in

a red caftan and pointed red cap, and has a hunch-

back, a large hooked nose, and a prominent chin.

The most popular scenes involve Petrushka and a

handful of characters, among them his fiancée or

wife, a gypsy horse trader, a doctor or apothecary,

an army corporal, a policeman, the devil, and a

large fluffy dog. Igor Stravinsky’s ballet Petrushka

(1911) is probably the most famous adaptation of

this puppet theater show.

See also: FOLKLORE; FOLK MUSIC; STRAVINSKY, IGOR FYO-

DOROVICH.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kelly, Catriona. (1990). Petrushka: The Russian Carnival

Puppet Theatre. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Zguta, Russell. (1978). Russian Minstrels: A History of the

Skomorokhi. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press.

P

ATRICIA

A

RANT

PETTY TUTELAGE

Petty tutelage in the Soviet economy meant that

the day-to-day operations of enterprises could be

(and frequently were) directly influenced or con-

trolled by decisions or actions of the industrial min-

istry to which the enterprise was subordinate.

While Soviet enterprise managers ultimately were

responsible for producing the goods identified by

planners, industrial ministry officials exercised

control over the firm in a number of ways. First,

the industrial ministry annually allocated the plan

targets among the enterprises subordinate to it,

thereby defining changes in output requirements

by firm over time. That is, ministry officials were

responsible for disaggregating the targets they re-

ceived from Gosplan, the State Planning Commit-

tee, and preparing the annual enterprise plan, the

techpromfinplan. Second, industrial ministry offi-

cials distributed the financial resources provided to

them by state committees to individual firms. Fi-

nancial resources included funds for wages and in-

vestment purposes. Third, each industrial ministry

redistributed profits earned by firms subordinate to

them among these same firms. Finally, ministry

officials responded to requests from enterprise

managers to change or “correct” output plan tar-

gets or input allocations over the course of the plan-

ning period if circumstances precluded successful

plan fulfillment.

During perestroika, numerous policies were

adopted to reduce petty tutelage by industrial min-

istry officials over Soviet enterprise operations.

Some view the reduction of ministerial tutelage and

the corresponding increase in decision-making au-

thority by enterprises as a cornerstone of pere-

stroika. Ministry officials were to cease exercising

routine daily control over enterprises and focus

instead on long-term issues such as promoting

investment and technological advance. However,

performance measures applied to the industrial

ministry remained linked to the performance of

their firms, and the ministry retained control over

funds and resources to be allocated to Soviet en-

terprises. Consequently, in practice, it is unlikely

that petty tutelage declined.

See also: GOSPLAN; TECHPROMFINPLAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berliner, Joseph S. (1957). Factory and Manager in the

USSR. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gregory, Paul R. (1990). Restructuring the Soviet Economic

Bureaucracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

PHOTOGRAPHY

The development of photography in Russia during

the nineteenth century followed a history similar

to that of other European countries. After Louis-

Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and William Henry Fox

Talbot made public their methods for capturing im-

ages on light-sensitized surfaces in 1839, I. Kh.

Gammel, corresponding member to the Russian

Academy of Sciences, visited both inventors to learn

more about their work and collected samples of

daguerreotypes and calotypes for study by Russ-

ian scientists. The Academy subsequently commis-

sioned Russian scientists to further investigate both

PETTY TUTELAGE

1178

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

processes. As elsewhere, Russian experimenters

quickly introduced a variety of refinements to the

initial processes.

Photography found immediate popular success

in Russia with the establishment of daguerreotype

portrait studios in the 1840s. The similarity of the

photograph to the Orthodox icon (an image that

is believed to be a direct and truthful record of a

physical being) heightened the early reception of

photography and resulted in the persistence of por-

traiture as a major genre in Russia. While the first

generation of photographers was largely foreign,

native practitioners soon appeared. Some, such as

Sergei Levitsky, achieved international recognition

for their role in the development of photography.

A personal acquaintance of Daguerre, Levitsky es-

tablished studios in both France and Russia, serv-

ing as court photographer for the Romanovs and

Napoleon III. During the later nineteenth century,

Russian photography became institutionalized with

the establishment of journals, professional societies,

and exhibitions.

While photography was initially largely re-

jected as an art, it became widely accepted with the

emergence of Realism. Russian photographers used

the camera to capture the changing social land-

scape that accompanied the liberation of the serfs

and growing urbanization. Simultaneously, ethno-

graphic photography became an important genre

with the expansion of the Russian Empire and the

opening of Central Asia. Numerous photographic

albums and research projects documented the peo-

ples, customs, landscape, and buildings of diverse

parts of the Russian Empire. With the rise of Sym-

bolism, a younger generation of pictorialist pho-

tographers rejected the photograph as document

in pursuit of more aestheticizing manipulated im-

ages.

At the turn of the century, technological de-

velopments led to the appearance of popular illus-

trated publications and the emergence of modern

press photography. The Bulla family established

the first Russian photo agency; they documented

such events as the Russo-Japanese War, World War

I, and the 1917 Revolutions. The growing com-

mercial availability of inexpensive cameras and

products rendered photography more pervasive in

Russia. However, with the commercialization of

photography, Russian practitioners became in-

creasingly dependent upon foreign equipment and

materials. With the outbreak of World War I, pho-

tographers were largely cut off from their supplies,

and the ensuing crisis severely limited photographic

activity until the mid-1920s.

After the October Revolution, Russian photog-

raphy followed a unique path due to the ideologi-

cal imperatives of the Soviet regime. The Bolsheviks

quickly recognized the propaganda potential of

photography and nationalized the photographic in-

dustry. During the civil war, special committees

collected historical photographs, documented con-

temporary events, and produced photopropaganda.

In the early 1920s, Russian modernist artists, such

as Alexander Rodchenko, experimented with the

technique of photomontage, the assembly of pho-

tographic fragments into larger compositions.

With the growing politicization of art, photomon-

tage and photography soon became important me-

dia for the creation of ideological images. The 1920s

also witnessed the foundation of the Soviet illus-

trated mass press. Despite a shortage of experienced

photojournalists, the development of the illustrated

press cultivated a new generation of Soviet pho-

tographers. Mikhail Koltsov, editor of the popular

magazine Ogonek, laid the groundwork for modern

photojournalism in the Soviet Union by establish-

ing national and international mechanisms for the

production, distribution, and preservation of pho-

tographic material. Koltsov actively promoted pho-

tographic education and the further development

of both amateur and professional Soviet photogra-

phy through the magazine Sovetskoye foto.

During the First Five-Year Plan, creative de-

bates emerged between modernist photographers

and professional Soviet photojournalists. While

both groups shunned aestheticizing pictorialist ap-

proaches and were ideologically committed to the

development of uniquely Soviet photography, dif-

ferences arose concerning creative methods, espe-

cially the relative priority to be given to the form

versus content of the Soviet photograph. These

debates stimulated the further development of So-

viet documentary photography. The illustrated

magazine USSR in Construction (SSSR na stroike;

1930–1941, 1949) was an important venue for So-

viet documentary photography. Published in Russ-

ian, English, French, and German editions, it

featured the work of top photographers and pho-

tomontage artists. Like the nineteenth-century

ethnographic albums, USSR in Construction pre-

sented the impact of Soviet industrialization and

modernization in diverse parts of the USSR in film-

like photographic essays. As the 1930s progressed,

official Soviet photography became increasingly

lackluster and formulaic. Published photographs

PHOTOGRAPHY

1179

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

were subjected to extensive retouching and

manipulation—not for creative ends, but for the

falsification of reality and history. An abrupt

change took place during World War II, when So-

viet photojournalists equipped with 35-millimeter

cameras produced spontaneous images that cap-

tured the terrors and triumphs of war.

Soviet amateur photography flourished in the

late 1920s with numerous worker photography

circles. Amateur activity was stimulated by the de-

velopment of the Soviet photography industry and

the introduction of the first domestic camera in

1930. Later that decade, however, government reg-

ulations increasingly restricted the activity of am-

ateur photographers, and the number of circles

quickly diminished. The material hardships of the

war years further compounded this situation, prac-

tically bringing amateur photographic activity to

a standstill. With independent activity severely cir-

cumscribed, Soviet photography was essentially

limited to the carefully controlled area of profes-

sional photojournalism.

During the Thaw of the late 1950s, the appear-

ance of new amateur groups led to the cultivation

of a new generation of photographers engaged in

social photography that captured everyday life.

Their activity, however, was largely underground.

By the 1970s, photography played an important

role in Soviet nonconformist and conceptual art.

Artists such as Boris Mikhailov appropriated and

manipulated photographic imagery in a radical cri-

tique of photography’s claims to truth. After the

collapse of the Soviet Union, many photographic

publications and industrial enterprises gradually dis-

appeared. While professional practitioners quickly

adapted to the new market system and creative pho-

tographers achieved international renown, the main

area of activity was consumer snapshot photogra-

phy, which flourished in Russia with the return of

foreign photographic firms.

See also: CENSORSHIP; NATIONALISM IN THE ARTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Elliott, David, ed. (1992). Photography in Russia,

1840–1940. London: Thames and Hudson.

King, David. (1997). The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsi-

fication of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia. New

York: Metropolitan Books.

Sartori, Rosalind. (1987). “The Soviet Union.” In A His-

tory of Photography: Social and Cultural Perspectives,

ed. Jean-Claude Lemagny and André Rouillé. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Shudakov, Grigory (1983). Pioneers of Soviet Photography.

New York: Thames and Hudson.

USSR in Construction. (1930–1941, 1949). Moscow: Go-

sizdat.

Walker, Joseph, et al. (1991). Photo Manifesto: Contem-

porary Photography in the USSR. New York: Stewart,

Tabori & Chang.

E

RIKA

W

OLF

PIMEN, PATRIARCH

(1910–1990), patriarch of the Russian Orthodox

Church from June 2, 1971, to May 3, 1990.

Sergei Mikhailovich Izvekov took monastic

vows in 1927 and worked with church choirs in

Moscow. Later, as Patriarch Pimen, his excellent

musical sense led him to forbid singers to embell-

ish the liturgy with operatic flourishes.

During World War II Pimen allegedly concealed

his monastic vows and served as an army officer

in communications or intelligence. When discov-

ered, he was incarcerated, and his political vulner-

ability was said to have figured in the Soviet

authorities’ decision that he could be controlled as

patriarch. More friendly sources recount his hero-

ism in protecting his men with his own body un-

der bombardment. His official biography omits his

military service.

Judgments of Pimen as patriarch are mixed. He

was accused of being withdrawn, passive, and in-

creasingly infirm. On the other hand, he was a

gifted poet, radiated spirituality, and was said to

have defended the integrity of the Church against

corrupting modernism and reckless innovation. Pi-

men’s moment came when Communist General

Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev decided to greet the

millennium of Russia’s conversion to Christianity

by improving relations with the Church. Gorbachev

received Pimen on April 29, 1988, and more than

eight hundred new parishes were permitted to open

that year. Sunday schools, charitable works, new

seminaries and convents, and other concessions to

church needs followed. Whether these tangible ben-

efits justified Pimen’s political collaboration with the

Soviet regime is a controversial question.

See also: RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH; RUSSIFICATION

PIMEN, PATRIARCH

1180

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Pospielovsky, Dimitry. (1984). The Russian Church Under

the Soviet Regime 1917–1982. 2 vols. Crestwood, NY:

St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

N

ATHANIEL

D

AVIS

PIROGOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

(1810–1881), scientist, physician, proponent of ed-

ucational reform.

Nikolai Pirogov was born in Moscow where his

father managed a military commissary. After grad-

uating from the medical school of Moscow Uni-

versity, he enrolled at the Professors’ Institute at

Dorpat University to prepare for teaching in insti-

tutions of higher education. In Dorpat he special-

ized in surgical techniques and in pathological

anatomy and physiology. After five years at Dor-

pat, he went to Berlin University in search of the

latest knowledge in anatomy and surgical tech-

niques. While in Berlin he was appointed a pro-

fessor at Dorpat, where he quickly acquired a

reputation as a successful contributor to anatomy

and an innovator in surgery. In 1837–1839 he pub-

lished Surgical Anatomy of Arterial Trunks and Fas-

ciae in Latin and German.

In 1841 Pirogov accepted a teaching position at

the Medical and Surgical Academy in St. Peters-

burg, the most advanced school of its kind in Rus-

sia. He lectured on clinical service in hospitals and

pathological and surgical anatomy. His major work

published under the auspices of the Medical and

Surgical Academy was the four-volume Anatomia

Topographica (1851–1854) describing the spatial re-

lations of organs and tissues in various planes. He

was also the author of General Military Field Surgery

(1864), relying heavily on his experience in the

Crimean War (1853–1855). In recognition of his

scholarly achievement, the St. Petersburg Academy

of Sciences elected him a corresponding member.

Tired of petty academic quarrels and intrigues,

Pirogov resigned from his professorial position in

1856. In the same year he published “The Questions

of Life,” an essay emphasizing the need for a reori-

entation of the country’s educational system. The

article touched on many pedagogical problems of

broader social significance, but the emphasis was

on an educational philosophy that placed equal em-

phasis on the transmission of specialized knowledge

and the acquisition of general education fortified by

increased command of foreign languages. He also

pointed out that, because of the low salaries, Russ-

ian teachers were compelled to look for additional

employment, which limited their active involve-

ment in the educational process. In his opinion, one

of the most pressing tasks of the Russian govern-

ment was to make the entire school system acces-

sible to all social strata and ethnic groups.

The government not only listened to Pirogov’s

plea for a broader humanistic base of the educa-

tional system, but in the same year appointed him

superintendent of the Odessa school district. Two

years later, he became the superintendent of the

Kiev school district. In his numerous circulars and

published reports he advocated a greater participa-

tion of teachers’ councils in decisions on all aspects

of the educational process.

Apprehensive of the long list of his liberal re-

forms, the Ministry of Public Education decided in

1861 to ask Pirogov to resign from his high post

in education administration. His dismissal pro-

voked a series of rebellious demonstrations by Kiev

University students.

Pirogov’s government service, however, did not

come to an end. In 1862 he was assigned the chal-

lenging task of organizing and supervising the ed-

ucation of Russian students enrolled in Western

universities. In 1866 the government again retired

him; the current minister of public education thought

that the supervision of foreign education could be

done more effectively by a “philologist” than by a

“surgeon.”

In 1881 a large group of scholars gathered in

Moscow to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of

Pirogov’s engagement in science. Four years later,

an even larger group founded the Pirogov Society

of Russian Physicians with a strong interest in so-

cial medicine. It was not unusual for the periodic

conventions of the Society to be attended by close

to two thousand persons.

See also: EDUCATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frieden, Nancy M. (1981). Russian Physicians in an Era

of Reform and Revolution, 1856–1905. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Vucinich, Alexander. (1963–1970). Science in Russian Cul-

ture, vols. 1–2. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press.

A

LEXANDER

V

UCINICH

PIROGOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

1181

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

PISAREV, DMITRY IVANOVICH

(1840–1868), noted literary critic, radical social

thinker, and proponent of “rational egoism” and

nihilism.

Born into the landed aristocracy, Dmitry

Ivanovich Pisarev studied at both Moscow Univer-

sity and St. Petersburg University, concentrating

on philology and history. From 1862 to 1866, Pis-

arev served as the chief voice of the journal The

Russian Word (Russkoye slovo), a journal somewhat

akin to The Contemporary (Sovremennik), which was

published and edited by the poet Nikolai Nekrasov

(1821–1878). In 1862 Pisarev was imprisoned in

the Petropavlovsk Fortress for writing an article

criticizing the tsarist government and defending the

social critic Alexander Herzen, editor of the London-

based émigré journal The Bell (Kolokol). Ironically,

Pisarev’s arrest marked his own rise to prominence,

coinciding with the death of Nikolai Dobrolyubov

in 1861 and arrest of Nikolai Chernyshevsky in

1862. During his incarceration for the next four

and one-half years, Pisarev continued to write for

the The Russian Word, including several influential

articles exhibiting his literary panache: “Notes on

the History of Labor” (1863), “Realists” (1864),

“The Historical Ideas of Auguste Comte” (1865),

and “Pushkin and Belinsky” (1865). His articles on

Plato and Prince Metternich, and especially the ar-

ticle “Scholasticism of the Nineteenth Century”

brought him fame as a literary critic.

Pisarev differed from other, more liberal, social

reformers of the first half of the decade, since he

stressed individual-ethical aspects of socioeconomic

reforms, such as family problems and the difficult

position of women in society. When Cherny-

shevsky’s novel What is to Be Done (Chto delat?)

came out in 1863, Pisarev praised it as a utilitar-

ian tract focusing on the positive aspects of nihilism

(generally, the view that no absolute values exist).

At the same time, Pisarev criticized Chernyshevsky

for his intellectual timidity and failure to develop

his ideas far enough. According to Pisarev, a func-

tional society did not need literature (“art for art’s

sake”), and literature, therefore, should simply

merge with journalism and scholarly investigation

as descriptions of reality. He even assaulted the rep-

utation of Alexander Pushkin, claiming that the

poet’s work hindered social progress and should be

consigned to the dustbin of history.

Rather than scorn Ivan Turgenev’s novel Fa-

thers and Sons (Otsy i deti), written in 1862, as

Chernyshevsky did, claiming it castigated the rad-

ical youth, Pisarev strongly identified with the

novel’s hero Bazarov—a nihilist who believes in

reason and has a scientific understanding of soci-

ety’s needs, but rejects traditional religious beliefs

and moral values. “Bazarov,” Pisarev wrote, “is a

representative of our younger generation; in his

person are gathered together all those traits scat-

tered among the mass to a lesser degree.” To Pis-

arev, Bazarov’s “realism” and “empiricism” reduced

all matters of principle to individual preference.

Turgenev’s hero is governed only by personal

caprice or calculation. Neither over him, nor out-

side him, nor inside him does he recognize any reg-

ulator, any moral law. Far above feeling any moral

compunction against committing crimes, the new

hero of the younger generation would hardly sub-

ordinate his will to any such antiquated prejudice.

Pisarev’s readers gleaned in the author him-

self some of these same extremist, nihilist ten-

dencies. However, while Pisarev was an extremist

intellectual, he was an honest one. He eloquently

advocated such practical social types as Bazarov—

activists for the intelligentsia, that is, people who

could play the role of a “thinking proletariat.” Yet

Pisarev himself did not advocate a political revo-

lution. He believed society, and above all the mass

of the people, could be transformed through so-

cioeconomic change. He simply denounced what-

ever stood in the way of such peaceful change

more trenchantly than any of his predecessors

had. Thus this urging to attack anything that

seemed socially useless sounded more revolution-

ary than it really was.

Upon his release from prison, Pisarev con-

tributed articles to the journals The Task (Delo) and

Notes of the Fatherland (Otechestvennye zapiski). Al-

though he drowned in the Gulf of Riga in 1868,

at the age of twenty-eight, his ideas continued to

influence other writers, notably Fyodor Dos-

toyevsky. In Crime and Punishment (Prestuplenie i

nakazanie) Dostoyevsky’s hero Raskolnikov (from

the word raskol or “split”) shows what occurs

when one flaunts moral principles and takes a hu-

man life. In The Possessed (Besy) Dostoyevsky

shows his reader the worst ways in which human

beings can abuse their freedom. Several characters

in this novel act on horrifying beliefs, leaving nu-

merous dead bodies in their wake. Raskolnikov’s

views pale next to the shocking behavior of the

“demons” whom Dostoyevsky feared most: hu-

man beings who lose their perspective and let the

worst side of their natures predominate.

PISAREV, DMITRY IVANOVICH

1182

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY