Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

founded the independent Association of Traveling

Art Exhibits. Commonly known as the peredvizh-

niki (wanderers or itinerants), these artists painted

Russian landscape, social genre, or historical scenes

that were literally read by both Stasov and the pub-

lic as critical commentary on current events. Stasov

was very closely associated with Ilya Repin, the

foremost painter of the school.

In the 1890s, as aestheticism began to supplant

national realism, Stasov’s renown and influence

waned. Prior to World War I and during the first

decade of the Soviet regime, Stasov’s views were

not respected, and were even derided, by the cre-

ative intelligentsia. His standing was restored by

the Communist Party after the imposition of so-

cialist realism as the guiding ideology for literature

and the arts in 1932. But Stasov’s views were in-

creasingly distorted to legitimate a narrow politi-

cization of the arts and cultural isolationism that

bore little resemblance to his original position in his

creative period from 1860 to 1890. The pedestal on

which Stasov stood as the preeminent art and mu-

sic critic was toppled during the period of glasnost.

See also: ACADEMY OF ARTS; MIGHTY HANDFUL; MUSIC;

OPERA; SOCIALIST REALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Curran, M. W. (1965). “Vladimir Stasov and the Devel-

opment of Russian National Art, 1850–1906.” Ph.D.

diss., University of Wisconsin.

Olkhovsky, Vladimir. (1983). Stasov and Russian Na-

tional Culture. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

Stasov, Vladimir Vasilievich. (1968). Selected Essays on

Music, tr. Florence Jonas. New York: Praeger.

E

LIZABETH

K. V

ALKENIER

STATE CAPITALISM

The term state capitalism was coined by political

economists to describe market economies heavily

regulated or controlled by the state, on behalf of

property owners. Unlike stateless capitalism, where

markets function without governmental assis-

tance, commonly called “free enterprise,” political

authorities play a powerful role in state capitalist

systems. The government is the agent of property

holders, and functions as the executive committee

of the capitalist class, even though it usually claims

to rule in the interests of all the people. Social de-

mocratic regimes such as those of France and Ger-

many, and big-government systems such as the

United States that rely on Keynesian and other

macromanagement methods, are often classified as

state capitalist. Post-Soviet Russia, which describes

itself as a mixed social economy, combining state

and private ownership of the means of production

with an autocratic state, can also be listed under

this heading.

Even states dominated by administration and

planning, with restricted markets such as the So-

viet Union during the era of the New Economic Pol-

icy (NEP) 1921–1929, have been accused of being

state capitalist by alleging that self-serving bu-

reaucrats, or capitalist roaders had subverted and

co-opted the state. Post-Maoist China provides a

good example of how a socialist society governed

by a Communist Party can serve the interests of

property holders from the perspective of Marxist-

Leninism.

These distinctions are devoid of any rigorous

economic content. They may serve some useful

purpose for ideologues, but the classification re-

veals nothing about the productive potential, eco-

nomic efficiency, or welfare characteristics of any

particular state capitalist regime, or even whether

the system relies primarily on markets or plans.

The burden of the term is to place most economies

outside the hallowed pale of Marxist socialism.

Only North Korea and Cuba appear to be mostly

directive regimes, with strong states and a social-

ist credo, in the twenty-first century.

See also: CAPITALISM; COMMAND ADMINISTRATIVE ECON-

OMY; ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; MARKET SOCIAL-

ISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bettelheim, Charles. (1975). The Transition to Socialist

Economy. Hassocks: Harvester Press.

Buick, Adam, and Crump, John. (1986). State Capital-

ism: The Wages under New Management. Houndmills,

UK: Macmillan.

Cliff, Tony. (1974). State Capitalism in Russia. London:

Pluto Press.

Coleman, Kenneth M., and Nelson, Daniel N. (1984).

State Capitalism, State Socialism and the Politicization

of Workers. Pittsburgh: Russian and East European

Studies Program, University of Pittsburgh.

Crosser, Paul K. (1960). State Capitalism in the Economy

of the United States. New York: Bookman Associates.

Dunayevskaya, Raya. (1992). The Marxist-Humanist The-

ory of State-Capitalism: Selected Writings. Chicago:

News and Letters.

STATE CAPITALISM

1463

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Gallik, Dmitri; Kostinsky, Barry; and Treml, Vladimir.

(1983). Input-Output Structure of the Soviet Economy.

Washington DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau

of the Census.

James, Cyril Lionel Robert. (1969). State Capitalism and

World Revolution. Detroit: Facing Reality.

Raiklin, Ernest. (1989). After Gorbachev: A Mechanism for

the Transformation of Totalitarian State Capitalism

Into Authoritarian Mixed Capitalism. Washington,

DC: Council for Social and Economic Studies.

S

TEVEN

R

OSEFIELDE

STATE COMMITTEES

The first state committees in the USSR, STO (Sovet

truda i oborony, the Council of Labor and Defense)

and Gosplan (State Planning Committee) were stand-

ing commissions of Sovnarkom (Council of People’s

Commissars). Their number grew during the 1930s,

and the 1936 constitution granted Sovnarkom

membership to the chairpersons of the All-Union

Committee for the Arts (Komiskusstv or Vsesoy-

uzny komitet po delam iskusstv) and the All-Union

Committee for Higher Education (Komvysshshkol or

Vsesoyuzny komitet po delam vysshei shkoly).

Chairpersons of other committees, such as the All-

Union Committee for Physical Culture and Sport

(Komfizkult or Vsesoyuzny komitet po delam fiz-

kultury i sporta), were not granted this status. Dur-

ing World War II, the State Defense Committee (GKO

or Gosudarstvenny komitet oborony), chaired by

Josef Stalin, was created as the extraordinary su-

preme state body to direct military and civilian

resources and the economy, in order to achieve vic-

tory. This body was very significant during the war,

and was the most powerful of all state committees

during the USSR’s existence.

In the 1950s and 1960s, with the increasing

complexity of the economy of the USSR, and the

increased importance of science and technology, the

system of state committees developed rapidly as

central interdepartmental agencies that coordinated

and supervised the work of ministries and other

state departments in their areas of responsibility.

Although the state committees were formed theo-

retically by the Supreme Soviet, and their structure

was approved by the Council of Ministers, the real

decisions concerning their existence and structure

lay with the Politburo. State committees were al-

located administrative powers to organize, coordi-

nate, and supervise the state departments with

which they were concerned, their instructions hav-

ing the force of law within the area of their juris-

diction. Like ministries, they could be either

all-Union, with plenipotentiaries in the republics,

or union-republic, functioning through parallel ap-

paratuses in the republics.

The State Committee of the USSR on Defence

Technology (GKOT or Gosudarstvenny komitet

SSSR po oboronu tekhnike) was created in 1957

but incorporated into a newly created Ministry of

General Machine Building in 1965. The committee

was responsible for all strategic ballistic missiles,

spacecraft, and satellites developed in the USSR. By

1973 the following state committees existed:

State Planning Committee (Gosplan or Gosu-

darstvenny planovy komitet).

State Committee of the Council of Ministers of

the USSR for Construction (Gosstroi or Go-

sudarstvenny komitet soveta ministrov

SSR po delam stroitelstva). Formed in 1950

to secure increased efficiency in construc-

tion.

State Committee on Labor and Wages (Gosu-

darstvenny komitet po voprosam truda i

zarabotnoi platy). Formed in 1955 to over-

see wages and working conditions.

Committee for State Security (KGB or Komitet

Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti.) Formed in

1954 when the police apparatus was reor-

ganized. The much feared secret police acted

with more autonomy than most other gov-

ernment bodies and with a large degree of

independence from the Council of Ministers.

State Committee on Foreign Economic Relations

(Gosudarstvenny komitet po vneshnim

ekonomicheskim svyazam). Formed in

1957 to develop economic cooperation with

foreign countries and ensure the fulfilment

of obligations. It was also responsible for

overseeing organizations responsible for

exporting equipment to socialist and de-

veloping countries.

State Committee of the Council of Ministers of

the USSR for the Supervision of Work

Safety in Industry and for Mining Supervi-

sion (Gosgortekhnadzor or Gosudarst-

venny komitet po nadzoru za bezopasnym

vedeniem raboty promyshlennosti i gor-

nomu nadzoru). Established in 1958.

State Committee for Vocational and Techni-

cal Education (Gosudarstvenny komitet po

professionalno-tekhnicheskomu obraziva-

niyu). Formed in 1959 to implement and

STATE COMMITTEES

1464

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

supervize policy for training skilled work-

ers both in vocational and technical insti-

tutions and in the workplace, to develop a

system of educational institutions in this

area, and to watch over students in these

institutions.

State Committee for Science and Technology

(Gosudarstvenny komitet po nauke i

tekhnike). Formed in 1965 to coordinate

policy to maximize the development and

utilization of science and technology for

economic purposes.

State Committee for Material and Technical

Supply (Gossnab or Gosudarstvenny ko-

mitet po materialno-tekhnicheskomu snab-

zheniyu). Formed in 1965 to supervise

distribution to consumers, coordinate co-

operation in delivery, and ensure fulfilment

of plans for supply of output.

State Price Committee (Gosudarstvenny ko-

mitet tsen). Formed in 1965 as a subcom-

mittee of Gosplan, it became a full state

committee in 1969. Its tasks included price

regulation, pricing policy, and the use of

prices to stimulate production.

State Forestry Committee (Gosudarstvenny

komitet lesnogo khozyaistva). Formed in

1966 to manage state forests and coordi-

nate the activities of forest agencies.

State Committee for Television and Radio (Go-

sudarstvenny komitet po televideniyu i ra-

dioveshchaniyu). Formed in 1970.

State Committee on Standards (Gossstandart or

Gosudarstvenny komitet standartov). Es-

tablished in 1970 to encourage standard-

ization and ensure standards in the quality

of output.

State Committee of the USSR Council of Min-

isters on Cinematography (Gosudarst-

venny komitet po kinematografii). Created

in 1972, its main task was to supervise the

activities of film studios in the USSR.

State Committee of the USSR Council of Min-

isters on Publishing, Printing, and the Book

Trade (Gosudarstvenny komitet po pe-

chati). Established in 1972 to supervise

publishing and the content of literature in

the USSR.

State Committee for Inventions and Discover-

ies (Gosudarstvenny komitet po delam izo-

breteny i otkryty). Established in 1973.

A law of 1978 granted membership in the

Council of Ministers to all chairpersons of state

committees.

After the fall of the USSR, the RSFSR contin-

ued the use of state committees, forming the State

Committee of the Russian Federation on Commu-

nications and Informatization (Goskomsvyaz or

Gosudarstvenny Komitet Rossisskoi Federatsii po

Svyazi i Informatizatsii) in 1997 from its Ministry

of Communications. It was responsible for state

management of communications and the develop-

ment of many forms of telecommunications and

postal services, including space communication in

conjunction with the Federal Space Program of

Russia.

See also: CONSTITUTION OF 1936; GOSPLAN; POLITBURO;

SOVNARKOM; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Prokhorev, A. M., ed. (1975). Great Soviet Encyclopedia:

A Translation of the Third Edition, vol. 7. New York:

Macmillan.

Unger, Aryeh. (1981). Constitutional Development in the

USSR: A Guide to the Soviet Constitutions. London:

Methuen.

Watson, Derek. (1996). Molotov and Soviet Government:

Sovnarkom, 1930–41. Basingstoke, UK: CREES-

Macmillan.

D

EREK

W

ATSON

STATE COUNCIL

The State Council was founded by Alexander I in

1810. It was the highest consultative institution of

the Russian Empire. The tsar appointed its mem-

bership that consisted of ministers and other high

dignitaries. While no legislative project could be

presented to the tsar without its approval, it had

no prerogatives to initiate legislation. Ministers sent

bills to the State Council on the tsar’s command,

reflecting the Council’s ultimate dependence on the

tsar for its institutional standing and activity. Since

the right of legislation belonged to the autocratic

tsar, the State Council could only make recom-

mendations on bills sent to it that the tsar could

accept or reject. Additionally the State Council ex-

amined administrative disputes between the differ-

ent governmental organs.

After the Revolution of 1905 and the October

Manifesto the State Council’s role changed: It be-

came the upper house of Russia’s new parlia-

mentary system. Every legislative bill needed the

STATE COUNCIL

1465

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Council’s approval before becoming law. It also had

the right to review internal policy of the Council

of Ministers, the state’s budget, declarations of war

and making of peace, and ministerial reports. Sev-

eral departments under the State Council’s juris-

diction prepared briefs and more importantly

analyzed legislation proposed by the Council of

Ministers.

The State Council, like all upper houses in Eu-

rope at the time, served as a check on the lower

house, the Duma. The tsar appointed half of the

Council’s members, while the other half were

elected on a restricted franchise from the zemstvos,

noble societies, and various other sections of the

elite, making it by nature more conservative. In the

period 1906–1914 the State Council, with the sup-

port of Nicholas II, played a large role in checking

the authority and activities of the Duma, which led

to general discontent with the post-1905 system.

Following the failed coup of August 1991, So-

viet President Mikhail Gorbachev created a State

Council consisting of himself and the leaders of the

remaining Union Republics. Gorbachev hoped the

State Council could craft a reconfigured USSR, but

republic representatives increasingly failed to attend

Council meetings. By the end of 1991, the State

Council—and the USSR—had petered out.

Russian President Vladimir Putin created his

own State Council in 2000, consisting of the lead-

ers of Russia’s eighty-nine administrative compo-

nents.

See also: ALEXANDER I; DUMA; FUNDAMENTAL LAWS OF

1906; PUTIN, VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Seton-Watson, Hugh. (1991). The Russian Empire

1801–1917. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yaney, George. (1973). The Systemization of Russian Gov-

ernment. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Z

HAND

P. S

HAKIBI

STATE DEFENSE COMMITTEE

With the intent of more effectively coordinating de-

cision-making for the war effort, on June 30, 1941,

Josef Stalin created the State Defense Council (also

known as State Defense Committee or GKO). Ac-

cording to his speech in which he announced this

body “all the power and authority of the state are

vested in it.” Its decisions and resolutions had the

force of law. The initial membership was composed

of Stalin as Chairman, Vyacheslav Molotov as

Deputy Chairman, Kliment Voroshilov, Georgy

Malenkov, and Lavrenti Beria. Stalin added Nikolai

Voznesensky, Lazar Kaganovich, and Anastas

Mikoyan in February, 1942.

The GKO met frequently, but informally, some-

times on short notice and often without a prepared

agenda but acted on issues that were foremost on

Stalin’s mind. Meetings always included people ad-

ditional to the GKO, usually some Politburo mem-

bers, members of the Central Committee, officers

of the High Command, and various others with

special knowledge requested to help address specific

issues. The GKO did not develop its own adminis-

trative apparatus, but primarily implemented its

decisions through the existing government bu-

reaucracy, especially the Council of Peoples’ Com-

missars (Sovnarkom), the individual commissariats,

and the State Planning Commission (Gosplan). Em-

ulating Vladimir Lenin and his use of the Defense

Council during the crisis years of the civil war,

Stalin and the GKO often relied on plenipotentiaries

endowed with broad powers to handle critical

tasks. Decision-making bodies of the Communist

Party and government were no longer asked for in-

put and were seldom called upon to ratify the

GKO’s decisions.

Each GKO member had specific areas of respon-

sibility to supervise and obtain results. Molotov

was to oversee tank production; Malenkov aircraft

engine production and the forming of aviation reg-

iments; Beria armaments, ammunition, and mor-

tars, Voznesensky heavy and light metals, oil, and

chemicals; Mikoyan supplying the Red Army with

food, gasoline, pay, and artillery. Rather less spe-

cific was the requirement that each member of the

GKO assist in inspecting fulfillment of decisions of

Peoples’ Commissars in the course of their work.

The chief strengths of the GKO were that it pro-

vided for quick decision-making on critical issues

and speedily disseminated vital information to those

at the top who needed to use it. The weaknesses of

the GKO were that a few men were burdened with

a multitude of tasks without a supporting admin-

istrative structure to distribute authority rationally

and evenly, or to allow initiative. By relying on the

existing Party and government structures, which

had proven inefficient and prone to parochialism in

defending their bureaucratic turf, the GKO was

unable to capitalize fully on the unity at the top.

STATE DEFENSE COMMITTEE

1466

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Furthermore, the commissariats other government

offices through which the GKO implemented its de-

cisions had been evacuated to the interior of the

USSR while the GKO remained in Moscow. The

physical distance between the GKO and the com-

missariats hindered communication and efficient

supervision. The government apparatus did not be-

gin returning to the capital until 1943. With the

end of the war, the GKO was formally dissolved on

September 4,1945.

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION;

STALIN, JOSEPH VISSARIONOVICH; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barber, John, and Harrison, Mark. (1991). The Soviet

Home Front 1941–1945. London: Longman.

Werth, Alexander.(1964). Russia at War. New York: Car-

rol and Graf.

R

OGER

R. R

EESE

STATE DEFENSE COUNCIL See STATE DEFENSE

COMMITTEE; WORLD WAR II.

STATE ENTERPRISE, LAW OF THE

Of the many pieces of legislation passed during the

period of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, the Law

of the State Enterprise (enacted 1987) was perhaps

the most important. It represented yet another ef-

fort to separate long-term perspective planning

from day-to-day operational control of enterprises.

The latter function was to be the exclusive respon-

sibility of the management, without the petty tute-

lage characteristic of the Soviet system. Enterprises

could now enter into contracts (direct links), make

quality improvements, and sell over-plan output

without the approval of superior agencies. Local

party organs would be banned from using enter-

prise personnel and materials for their own pur-

poses. The centralized system of supply would

control only the essential minimum necessary

through orders (zakazy) from customers, rather

than plan targets, as before. Accordingly, legal en-

forcement of contracts through arbitrazh (civil

arbitration) courts and other legal institutions

would be enhanced. A new agency was instituted,

Gospriyemka (State Acceptance), independent of en-

terprise management along the military model,

with the duty to check whether quality met state

standards. Along with enhanced managerial ac-

countability, these provisions were designed to as-

sure that enterprises produced what the public re-

ally wanted to buy.

But, perhaps inevitably, the centralized supply

organs would still have to check whether the cor-

rect volumes, assortments, and qualities of goods

had been delivered on time to essential operations,

such as the military-industrial complex. Ministries

would retain some influence through norms and

other indirect instruments, if not direct orders.

Aside from some minor products, the State Stan-

dards Committee would still set minimum quality

requirements. Moreover, party control of person-

nel and promotions remained untouched until the

end of Soviet rule.

See also: GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH; PERE-

STROIKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (1998). Russian

and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure,

6th ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Spechler, Martin C. (1989). “Gorbachev’s Economic Re-

forms: Early Assessments.” Problems of Communism

47(5):116–120.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

STATE ORDERS

The introduction of state orders, as a part of per-

estroika, was an attempt to move from a total state

control over the economy toward introduction of

some market elements. During the mid-1980s, the

Soviet communist leadership realized that the

country was losing the economic competition to

the West. The last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev,

introduced cautious policies designed to set up some

market elements. One such change was the intro-

duction of state orders.

Prior to perestroika, state enterprises were sup-

posed to produce goods according to the state plan

and deliver them to the state for distribution. Gor-

bachev’s idea was to replace the state plan with state

orders. Enterprises first had to produce and sell to

the state production to fulfill their state orders.

However, the state order should be for only part of

their production. After enterprises fulfilled the state

order—a guaranteed quantity of products that

would be purchased by the state and production for

which the state provided necessary resources—they

STATE ORDERS

1467

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

could sell the remainder to customers at negotiated

prices. The state order was supposed to constitute

only a portion of a plant’s potential output. It was

included in the state plan, and the resources for its

implementation were supposed to be allocated by

Gosplan. The percentage of state orders of total out-

put was supposed to decline, giving way to a mar-

ketlike economy.

See also: GOSPLAN; MARKET SOCIALISM; PERESTROIKA.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (2001). Russian

and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure.

Boston, MA: Addison Wesley.

P

AUL

R. G

REGORY

STATE PRINCIPLE

State principle is the leading principle of writing

and explaining Russian history in nineteenth-

century and, with some modifications, twentieth-

century national historiography.

Professor Johann Philipp Georg Ewers (1781–

1830) was the first to apply to the study of an-

cient Russian law the Hegelian theory of peoples’

evolution from family or kin phase to that of a

state. This idea was adopted and further elaborated

by the founders of the so-called state (or juridical)

school in Russian historiography, Konstantin

Kavelin (1818–1885) and Sergei Soloviev (1820–

1879). According to Soloviev, the transition from

kin relations as the dominant system to the strong

state organization in Russia took about four hun-

dred years, from the end of the twelfth century till

the reign of Ivan IV. Only after that, having en-

dured severe experience in the Time of Troubles,

the young Russian state found its place among

other European powers. Thus the whole course of

Russian history was presented as a progressive and

logically necessary movement toward the modern

centralized and autocratic state.

Though Soviet scholars, unlike Soloviev, con-

sidered Kievan Rus to be a feudal state, and thus

found state organization even in the ninth century,

they remained loyal to the state principle in their

own way. Thus, disunity of the Rus lands in the

twelfth through fourteenth centuries was regarded

as a negative phenomenon, and historians explic-

itly sympathized with the process of gathering Rus’

by Muscovite princes, dating the beginning of this

process as early as possible, in the early fourteenth

century (e.g., Cherepnin, 1960). Since the 1950s,

well into the 1980s, it was much debated who had

been allies and enemies of Muscovite centralization,

but “centralization” itself was still perceived as an

absolute good.

In spite of its teleological and nationalistic im-

plications, the state principle can be detected in

post-Soviet Russian historiography as well.

See also: HISTORIOGRAPHY; KIEVAN RUS; MUSCOVY;

SOLOVREV, VLADIMIR SERGEYEVICH; TIME OF TROU-

BLES

M

IKHAIL

M. K

ROM

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

The political police and other organs of state secu-

rity have played a prominent role in Russian and

Soviet history. For almost two hundred years they

have served a variety of state interests, including

among their functions the surveillance of the pop-

ulation; censorship; the quashing of political and

intellectual dissent; foreign and domestic espionage;

and the guarding of borders. At times they have

shared duties or been subsumed within the Min-

istry (or Commissariat) of Internal Affairs, and at

other times they have been self-standing organs,

often operating in parallel with the regular police

or militia.

Although the political police in the modern un-

derstanding of the term originated in Russia in the

early nineteenth century, various forms of special

security forces existed well before this. The first

such organ to play a prominent role was Ivan IV’s

(the Terrible) infamous oprichniki, who terrorized

the Russian aristocracy in the late sixteenth cen-

tury in order to root out Ivan’s real and imagined

foes. In the mid-seventeenth century Tsar Alexei

Mikhailovich (r. 1645–1676) made use of a “Secret

Department” (tainy prikaz) to keep him informed

of events in the capital and to confirm the accounts

of his foreign embassies. Crimes of “word and

deed,” that is, either speech or action deemed in-

imical to the tsar, were vigorously investigated.

Alexei’s successors continued to keep private se-

curity forces. Peter I (the Great) (r. 1682–1725)

maintained the “Preobrazhensky Department” and

later a “Secret Investigative Chancellery” staffed with

STATE PRINCIPLE

1468

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

close friends and trusted allies to maintain his per-

sonal power and to guard against insurrection.

These institutions were preserved in various forms

throughout the century, despite occasional gestures

toward limiting their power; their agents became

powerful instruments of the throne and were often

feared and loathed among court circles. Despite reaf-

firming her ill-fated husband Peter III’s (r. 1761–

1762) abolition of the Secret Chancellery, Catherine

II (the Great, r. 1762–1796) made much use of an

agency called the “Secret Expedition” to root out

opposition. Its leader, Stepan Sheshkovsky, was par-

ticularly noted for his brutal methods of interroga-

tion, especially in the latter years of Catherine’s

reign, when the French Revolution prompted an in-

tensification of repression.

These institutions (in general) had a narrower

focus and scope than would the genuine political

police that originated in the nineteenth century.

This had its root not only in the ideals of the En-

lightenment-era “well-ordered police state,” but

also, ironically, in the French Revolution, which at-

tempted to protect itself through institutions such

as the Committee for Public Safety. Hence the or-

gans of state security in Imperial Russia were con-

cerned not only with the possibility of immediate

rebellion within court circles, but with dissent in a

more general sense.

The early reforming efforts of Alexander I (r.

1801–1825) included the aspiration to establish a

more rational government system. Of course this

did not appear all at once, but it did involve the

creation of a ministry system, including the Min-

istry of Internal Affairs, which soon acquired com-

petence over all policing matters. In the latter years

of Alexander’s reign, several different groups func-

tioned as secret police forces, including the Secret

Chancellery within the Ministry of the Interior.

The true consolidation of a secret police force

came early in the reign of Nicholas I (r. 1825–

1855). Nicholas’s accession had been met with a re-

volt of military officers known to history as the

Decembrist uprising, and Nicholas became adamant

that such an occurrence not repeat itself. As part

of his efforts to strengthen his own autocratic pow-

ers vis-à-vis the ministerial system erected by his

brother Alexander, he had formed a set of agencies

under his own personal dominion, known collec-

tively as His Majesty’s Own Chancery. The infa-

mous “Third Section” of His Majesty’s Own

Chancery formed the first modern secret police force

in Russia. It was originally headed by General

Alexander Benckendorff and included much of the

staff of Alexander’s Secret Chancery. The Third Sec-

tion vastly expanded the range of surveillance func-

tions and incorporated other government officials

in its scope, using army gendarme units to spy on

the populace; the censors within the Ministry of

Education to detect subversive writings; and the

postal service to begin the practice of perlustration,

or examining the contents of letters. Benckendorff

also served as the head of the Corps of Gendarmes,

an army unit that came to serve as the Third Sec-

tion’s information-gathering apparatus.

The power of Nicholas’s secret police grew dur-

ing a time when political opposition in Russia was

relatively muted. It concentrated therefore on root-

ing out intellectual dissidents. During the European

Revolutions of 1848, the Gendarmes rounded up

members of the so-called Petrashevsky circle, in-

cluding the young Fyodor Dostoyevsky. It was un-

der Alexander II (r. 1855–1881), the Tsar-Liberator

who at last emancipated the serfs, that revolution-

ary opposition began truly to appear. In the early

1860s, student riots broke out at St. Petersburg

University, and in 1866 a demented ex-student at-

tempted to assassinate the tsar. From this time the

Third Section under Count Peter Shuvalov was

given immense powers to eradicate subversives. It

soon became involved in a number of high-profile

prosecutions, including the notorious Nechayev Af-

fair. Despite the judicial reforms of 1864, Shuvalov

continued to use extralegal means whenever secu-

rity and expediency required it. Through the 1870s,

however, public sympathy increasingly rested with

the defendants in a series of celebrated trials pros-

ecuting revolutionary terrorists and other radicals.

This culminated in the scandalous acquittal in 1878

of the man who had shot and wounded the much-

loathed St. Petersburg police chief General Trepov.

Political crimes were soon transferred to military

courts to better control the outcome. In 1880, in

an effort to better consolidate control, Alexander II

transferred the responsibilities of the Third Section

to a newly created Department of State Police

within the Ministry of Interior, then headed by the

moderate Count Mikhail Loris-Melikov.

On March 1, 1881, Alexander II was assassi-

nated by a conspiracy of the People’s Will terror-

ist organization led by Andrei Zhelyabov and Sofia

Perovskaya. His son and successor, Alexander III

(1881–1894), and his chief advisor Konstantin

Pobednostsev demanded a firm accounting. The

remnants of People’s Will and other terrorist

groups of the late 1870s were ruthlessly sought

out and expunged. Loris-Melikov was replaced by

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

1469

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Nikolai Ignatiev, who soon promulgated a set of

temporary measures providing for greater emer-

gency policing powers. Establishing a system of

quasi-martial law, these measures were renewed

periodically until 1917, and they were used by the

government when necessary to circumvent its own

legal institutions.

Henceforth the minister of the Interior would

have broad powers to quell real and potential dis-

turbances and dissent to maintain public order.

Within the Interior Ministry’s Police Department

was formed a new section in charge of political

crimes, called the Division for the Protection of

Order and Public Security, better known as the

Okhrana. During the 1880s, political proceedings

were much less publicized than they had been, and

the authorities began to expand the practice of ad-

ministrative exile of political prisoners—that is, de-

portation with no trial at all.

The Okhrana expanded the business of state

surveillance further than it had ever been before,

using undercover agents to infiltrate revolutionary

organizations. It also established a Foreign Agency

to operate among emigré groups conspiring against

the Russian government. From the assassination of

Alexander II to the fall of the Romanov dynasty,

the regime and its opponents were thus locked in

a bitter struggle replete with murder and intrigue.

Revolutionary terrorists, and in particular the

Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR), carried out sev-

eral spectacular assassinations, including several

ministers of the interior—Dmitry Sipiagin in 1902

and the much-loathed Vyacheslav von Plehve in

1904. In response, the Okhrana increasingly used

double agents to gather information on and con-

trol subversive groups, especially with the explo-

sion of terrorist activity during and after the

Revolution of 1905. The most infamous of the

agent provocateurs was Evno Azev, who served the

Okhrana while heading the SR’s Combat Organi-

zation, completely unbeknownst to his comrades,

until his dramatic exposure by the rabble-rousing

journalist Vladimir Burtsev. After 1908, there were

increasingly fewer assassinations of top tsarist of-

ficials, with the major exception of the assassina-

tion of Prime Minister Peter Stolypin in 1911.

Despite the Okhrana’s successful efforts at in-

filtrating revolutionary groups and the awe and

fear it inspired among the public, security officials

faced several important obstacles. There was divi-

sion over how to deal with the vigilante violence

of radical nationalists, aimed at Jews, revolution-

aries, and intellectuals. Many officials sympathized

with the politics of right-wing organizations, which

after all were bent on defending the monarchy, and

the Okhrana became involved in the printing of

anti-Semitic materials and condoned pogroms; but

others were leery of permitting popular disorder.

There was also disagreement over to what degree

the police could circumvent the rule of law in its

efforts to disrupt revolutionary activities.

In the end, the tsarist organs of state security

were unable to prevent the overthrow of the impe-

rial regime, despite a marked increase in surveillance

during World War I. The growing unpopularity of

the tsar and his government was greatly exacer-

bated by the quixotic influence of Grigory Rasputin,

whose rise to prominence concerned leaders of the

Okhrana proved powerless to prevent. After the Feb-

ruary Revolution in 1917, the Provisional Govern-

ment abolished the Okhrana and Gendarmes and

sponsored a series of hearings into the abuses of

power that had occurred during the previous regime.

The Council of People’s Commissars established

the first Soviet organ of state security in December

1917, creating the All-Russian Extraordinary Com-

mission for Combating Counter-Revolution and

Sabotage, better known by its Russian acronym as

the Cheka. It was headed by the inimitable Felix

Dzerzhinsky, recognized as the founder of the So-

viet secret police. Under Dzerzhinsky’s leadership

the Cheka, headquartered in the Lubyanka in cen-

tral Moscow, quickly became a critical part of the

Bolshevik efforts to stamp out all opposition in the

difficult early days of power.

Opponents of Soviet power were targeted start-

ing soon after it was founded. The Red Terror be-

gan after the assassination of the Petrograd Cheka

chief M. S. Uritsky and an unsuccessful attempt

on Lenin’s life, both on August 30, 1918. Hundreds

of real and imagined enemies were shot in an ef-

fort to quell all opposition, including Socialist Rev-

olutionaries, landlords, capitalists, and other people

associated with the old regime. Both the Bolsheviks

and the various counterrevolutionary governments

that formed during the civil war established intel-

ligence services and made ample use of terror in at-

tempting to win the struggle.

At the end of the civil war, some voices from

within the Bolshevik leadership began to press for

the establishment of revolutionary legality and a

reduction in the extralegal methods of the Cheka.

With Vladimir Lenin’s support, the Cheka was

abolished in February 1922 and replaced with the

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

1470

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

State Political Administration, or GPU. The GPU

was to be made nominally subordinate to the Peo-

ple’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, or NKVD,

and subject to the laws of Soviet Russia. However,

from the start this proved more illusion than real-

ity. Dzerzhinsky remained both commissar of in-

ternal affairs and head of the GPU, and within a

year and a half the GPU had reacquired most of its

former powers and been removed from NKVD

oversight (and renamed the OGPU). The transfor-

mation from Cheka to OGPU, from civil war

extraordinary to ordinary organ, marked the in-

stitutionalization of the security police in the So-

viet system.

During the 1920s the OGPU competed with

several other Soviet institutions for control of po-

litical policing operations. The system of adminis-

trative exile was reestablished along with a growing

system of forced labor camps known as gulags. Po-

litical prisoners soon populated these destinations

as they had under the old regime, and many indi-

viduals who had been exiled under the tsars found

themselves once again in prison. In addition, the

OGPU and the other organs of state security cre-

ated a system of surveillance that would soon

dwarf that of its tsarist predecessors. State censor-

ship was unified in 1922 under a new organ, called

Glavlit, which also worked closely with the secret

police. At the same time, infiltration of Russian

emigré groups and external espionage commenced.

A dramatic intensification of secret police activ-

ity marked the end of the 1920s, when Josef Stalin

solidified his hold on power. Dzerzhinsky and his

successors as head of the OGPU, Vyacheslav Men-

zhinsky and Genrikh Yagoda, allied themselves with

Stalin and were instrumental in helping purge the

opposition centering on Leon Trotsky. At the end of

the decade, a series of show trials were orchestrated

with OGPU support in which purported opponents

of Soviet power were exposed and eliminated. This

period ushered in the rapid intensification of Soviet

industrialization campaigns and the collectivization

of agriculture. It also featured the expansion of the

system of administrative exile and prison camps,

most notably through the campaign against the

wealthier peasants, or kulaks, who were thought to

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

1471

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

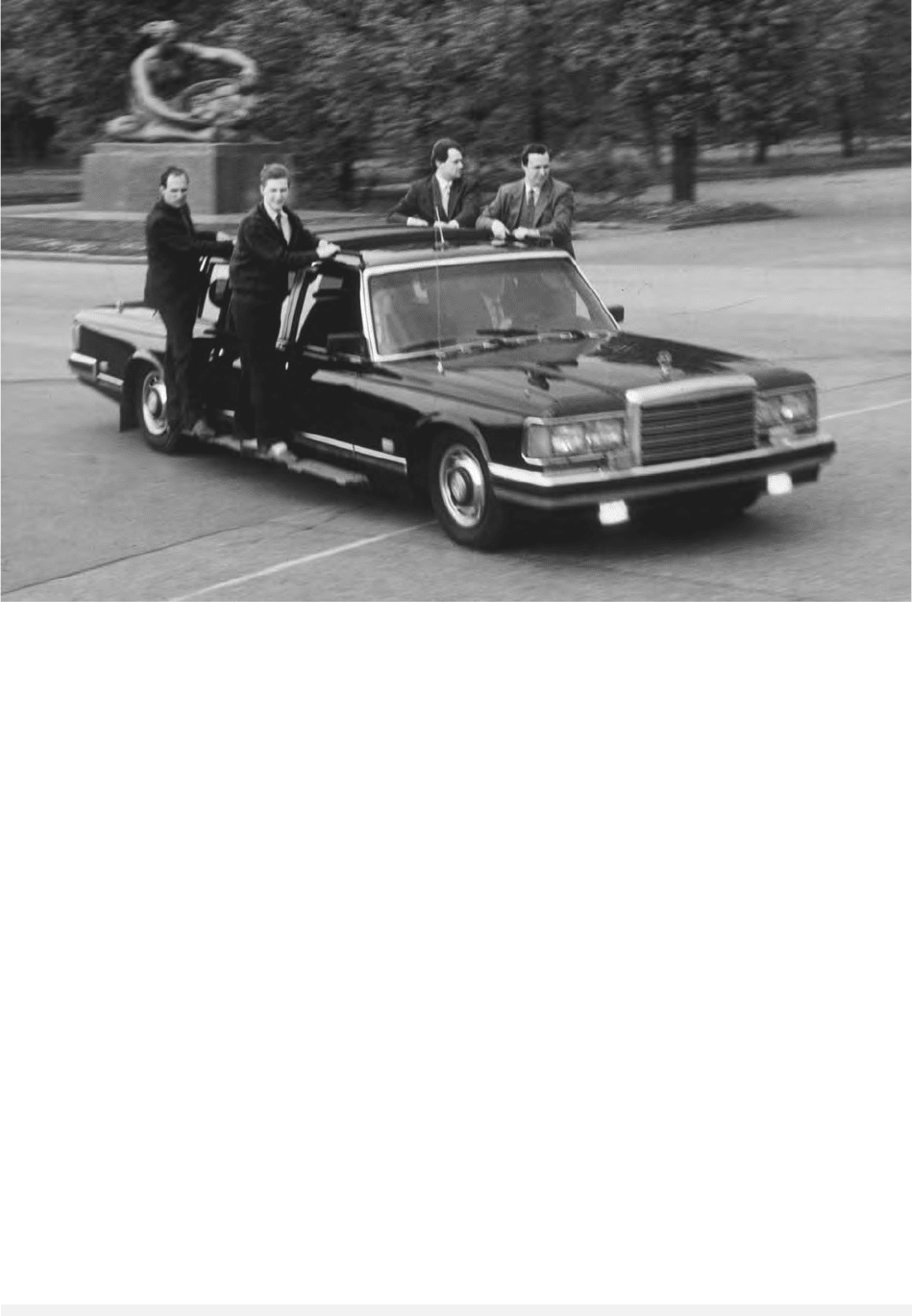

KGB bodyguards ride on a ZIL government car through the streets of Moscow. © TASS/S

OVFOTO

be congenitally resistant to collectivization. The

OGPU conducted a campaign of rooting out and de-

porting several hundred thousand kulaks and their

families in the early 1930s in order to eliminate op-

position to the collectivization of agriculture.

By 1931–1932 the OGPU had vastly expanded

its extralegal authority and had gained primary

competence over the rapidly growing penal appa-

ratus. Its ability to control and observe the popu-

lation was augmented through the introduction of

an internal passport system in 1932. The 1930s

and in particular the latter half of the decade are

the period in which the punitive functions of the

Soviet organs of state security reached their noto-

rious zenith. Driven by a desire to purge the coun-

try of all real and imagined enemies, Stalin and his

henchman in the secret police unleashed a wave of

arrests, deportations, and executions, later known

as the Great Terror.

In 1934 the OGPU was transformed once again

into the Main Administration of State Security

(GUGB) within a reconstituted Commissariat of In-

ternal Affairs (NKVD), under the leadership of Gen-

rikh Yagoda. The first wave of purges focused on

Stalin’s former colleagues in the Politburo who had

been part of the several oppositions in the previous

decade. The pretext for these purges was the De-

cember 1934 murder of the Leningrad Party chief

Sergei Kirov, an event that, according to some his-

torians, was actually ordered by Stalin himself. In

any event, the increasingly militant atmosphere fol-

lowing Kirov’s death, in which accusations against

loyal Leninists reached infamously absurd propor-

tions, culminated in the show trials of 1936–1938.

Such well-known old Bolsheviks as Lev Kamenev,

Grigory Zinoviev, and Nikolai Bukharin were ac-

cused of plotting against the Soviet state and exe-

cuted. Yagoda himself was caught up in the wave

of purges; he was replaced as NKVD chief by Niko-

lai Yezhov in September 1936 and arrested along

with a number of his colleagues the following year.

Toward the end of the decade, the NKVD-led

purges changed dramatically in tone and scope.

Starting in 1935, mass deportations of particular

ethnic groups deemed potentially unreliable had be-

gun, and in 1937–1938 Stalin and Yezhov un-

leashed the most concentrated wave of the Terror.

Hundreds of thousands of Party officials, former

oppositionists, intellectuals, military officers, and

ordinary citizens were arrested and imprisoned, de-

ported, or summarily executed under Article 58 of

the criminal code. Arrest numbers were approved

a priori from the center but consistently increased

based on requests from the localities. The Gulags

were expanded dramatically. The exact number of

victims has been a measure of some dispute and is

still being debated by scholars more than a decade

after the fall of the Soviet Union.

The start of World War II exacerbated the felt

need to remove potential fifth columns and inten-

sified the deportation of ethnic groups, including

Koreans, Poles, Germans, the Baltic peoples,

Chechens, and Tatars. Yezhov had been removed

and been replaced with the powerful Central Com-

mittee member Lavrenti Beria, marking yet another

purge of leading NKVD cadres. Under the leader-

ship of Beria and his equally notorious lieutenants,

the organs of state security changed names several

times, eventually reconstituting as the People’s

Commissariat for State Security (NKGB), which

was renamed the Ministry of State Security (MGB)

in 1946, functioning alongside and sharing some

duties with the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD).

In 1953, soon after Stalin’s death, the two min-

istries were fused, and a separate Committee for

State Security (KGB) was established the following

year. Beria was arrested by his anxious colleagues

and executed toward the end of the year. Thus the

three most notorious heads of the state security ap-

paratus during the height of repression, Yagoda,

Yezhov, and Beria, were all eventually removed by

the system they had turned into an instrument of

mass terror. The collective leadership that emerged

took careful steps to reestablish Party control over

the state security apparatus, and the security and

regular police were now separate organs.

The period of de-Stalinization under Nikita

Khrushchev brought with it the gradual end of the

terror and camp system that had characterized the

Stalin period, and Khrushchev’s exposure of the ex-

cesses of Stalin’s rule changed the nature of the se-

curity organs. At the same time, the transition did

not by any means diminish the authority of the

KGB under the leadership of Ivan Serov, Alexander

Shelepin, and their successors. While the abuses of

the previous period were decried, and socialist

legality once again stressed, the infiltration and

surveillance of society by the security organs con-

tinued to intensify. In addition, the foreign coun-

terespionage apparatus now reached a position of

supreme importance in the tense atmosphere of the

Cold War and the establishment of Soviet client

states in Eastern Europe and around the world.

That the KGB had emerged again as a power-

ful force in Kremlin politics is evidenced by the fact

that Shelepin and his handpicked successor, Vladimir

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

1472

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY