Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

days his feat was hailed by Pravda as a world

record. Anxious to celebrate and reward individu-

als’ achievements in production that could serve as

stimuli to other workers, the party launched the

Stakhanovite movement. The title of Stakhanovite,

conferred on workers and peasants who set pro-

duction records or otherwise demonstrated mas-

tery of their assigned tasks, quickly superseded that

of shockworker. Day by day throughout the au-

tumn of 1935, the campaign intensified, culmi-

nating in an All-Union Conference of Stakhanovites

in industry and transportation that met in the

Kremlin in November. At the conference, outstand-

ing Stakhanovites mounted the podium to recount

how, defying their quotas and often the skepticism

of their workmates and bosses, they applied new

techniques of production to achieve stupendous re-

sults for which they were rewarded with wages

that reached dizzying heights. Josef Stalin captured

the upbeat mood of the conference when, by way

of explaining how such records were only possible

in the land of socialism, he uttered the phrase, “Life

has become better, and happier too.” Widely dis-

seminated, and even set to song, Stalin’s words

served as the motto of the movement.

The Stakhanovite movement thus encom-

passed lessons not only about how to work, but

also about how to live. In addition to providing a

model for success on the shop floor, it conjured up

images of the good life. Many of the same quali-

ties Stakhanovites were supposed to exhibit in the

one sphere—cleanliness, neatness, preparedness,

and a keenness for learning—were applicable to the

other. These qualities were associated with kultur-

nost (culturedness), the acquisition of which marked

the individual as a New Soviet Man or Woman.

Advertisements for perfume, articles about Stak-

hanovites on shopping sprees, photographs of

Stakhanovites sharing their happiness with their

families, newsreels showing them driving new

automobiles—presented to them as gifts—and mov-

ing into comfortable apartments all symbolized kul-

turnost. Wives of male Stakhanovites had an

important part to play in the movement as help-

mates preparing nutritious meals, keeping their

apartments clean and comfortable, and otherwise

creating a cultured environment in the home so that

their husbands were well-rested and eager to work

with great energy. It was also important to demon-

strate that Stakhanovites were admired by their com-

rades and considered worthy of holding public office.

Notwithstanding the enormous publicity sur-

rounding Stakhanovites and their achievements,

they were not necessarily popular. Even before the

raising of output norms in early 1936, workers

who had not been favored with the best condi-

tions, and consequently struggled to fulfill their

norms, expressed resentment of Stakhanovites by

verbally and even physically abusing them. Fore-

men and engineers, only too well aware that

record mania and the provision of special condi-

tions for Stakhanovites created disruptions in

production and bottlenecks in supplies, also on oc-

casion sabotaged the movement. At least that was

the accusation made against many who often

served as scapegoats for the failure of the Stak-

hanovite movement to fulfill its promise of un-

leashing the productive forces of the country.

Nevertheless, the Stakhanovite movement contin-

ued into the war and even enjoyed something of

a revival in the postwar years, when it was ex-

ported to Eastern Europe.

See also: INDUSTRIALIZATION, SOVIET; KULTURNOST; SO-

VIET MAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Siegelbaum, Lewis H. (1988). Stakhanovism and the Pol-

itics of Productivity in the USSR, 1935–1941. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Thurston, Robert. (1993). “The Stakhanovite Movement:

The Background to the Great Terror in the Factories,

1935–1938.” In Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives, eds.

J. Arch Getty and Roberta T. Manning. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

L

EWIS

H. S

IEGELBAUM

STALIN CONSTITUTION See CONSTITUTION OF

1936.

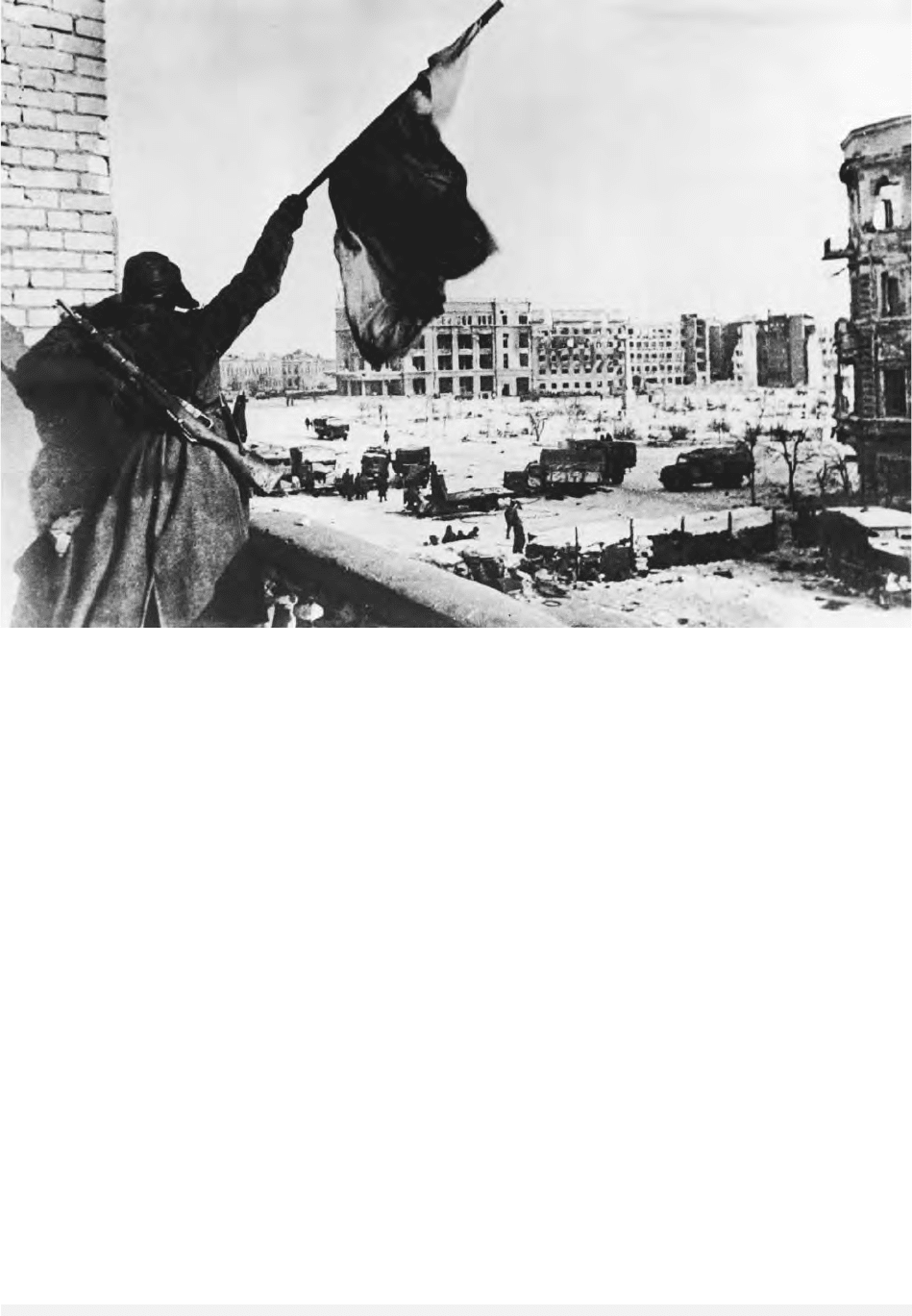

STALINGRAD, BATTLE OF

The Battle of Stalingrad (July 17, 1942–February 2,

1943) was the most significant Red Army victory

during World War II. It included the Red Army’s

defense against Operation “Blau” (Blue), the Ger-

man Army’s summer 1942 advance to Stalingrad,

and offensive operations in the fall of 1942 and

winter of 1943 to defeat German and other Axis

forces in the Stalingrad region.

The defensive phase of the battle began on July

17, after German Army Groups “A” and “B”

smashed the defenses of the Red Army’s Briansk,

STALINGRAD, BATTLE OF

1453

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Southwestern, and Southern Fronts in southern

Russia and advanced to the Don River west of

Stalingrad. Initially, the newly formed Stalingrad

Front, commanded by marshal of the Soviet Union

S. K. Timoshenko, defended the Stalingrad region

with the 21st, 62d, 63d, 64th, and 57th Armies,

the 1st and 4th Tank Armies, and the 8th Air Army,

which opposed the 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army

of Army Group “B.” After overwhelming the 62nd

and 64th Army’s defenses west of the Don River in

late July and defeating a major counterstroke by

the 1st and 4th Tank Armies, in late August Gen-

eral Friedrich Paulus’s Sixth Army broke through

Soviet defenses along the Don River and reached the

Volga River north of Stalingrad, while General Her-

mann Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army reached the city’s

southwestern suburbs. The twin blows isolated the

Soviet 62d and 64th Armies in Stalingrad and ini-

tiated two months of vicious and costly fighting

for possession of the city. The fighting consumed

the bulk of German forces and forced them to de-

ploy weak Italian and Rumanian armies along their

overextended flanks north and south of the city.

While Stalin fed enough forces into Stalingrad to

tie German forces down, the Stavka planned a

counteroffensive, Operation “Uranus,” orchestrated

by General A. M. Vasilevsky, to encircle and de-

stroy Axis forces at Stalingrad.

The offensive phase of the battle commenced

on November 19, 1942, when the forces of General

N. F. Vatutin’s and A. I. Eremenko’s Southwestern

and Stalingrad Fronts pierced Axis defenses north

and south of the city and joined west of Stalingrad

on November 23, encircling more than 300,000

German and Rumanian forces in the city. Offen-

sives by the Southwestern and Stalingrad Fronts

along the Chir, Don, and Aksai Rivers in December

destroyed the Italian 8th Army and frustrated two

German attempts to rescue their forces besieged

in Stalingrad. On February 2, 1943, after Bryansk,

Voronezh, Southwestern, and Southern (former

Stalingrad) Front forces attacked westward from

the Don River and toward Rostov, General K. K.

STALINGRAD, BATTLE OF

1454

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A Red Army soldier waves a flag while trucks gather in the square below during the Battle of Stalingrad. © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

Rokossovsky’s Don Front defeated and captured

Paulus’s 6th Army and almost 100,000 men.

At a cost of more than one million casualties,

including almost 500,000 dead, missing, or cap-

tured, during the battle the Red Army destroyed or

badly damaged five Axis armies, including two

German, totaling more than fifty divisions, and

killed or captured more than 600,000 Axis troops.

The unprecedented German defeat was a turning

point indicative of eventual Red Army victory in

the war.

See also: WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beevor, Antony. (1998). Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege,

1941–1943. New York: Viking

Erickson, John. (1975). The Road to Stalingrad. New

York: Harper & Row.

Glantz, David M. (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the

Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence: University Press

of Kansas.

D

AVID

M. G

LANTZ

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

(1879–1953), general secretary of the Communist

Party, Soviet dictator.

Josef Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, who in rev-

olutionary work was called Koba before adopting

the nom de plume Stalin, was born in Gori, Geor-

gia, to a working-class family; his father was a

cobbler and his mother a domestic servant. Many

of the details of his early life remain in dispute, but

his education was gained at a local church school

and the Tiflis (Tbilisi in Georgian) Orthodox semi-

nary, from which he was expelled in 1899. He

joined the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party

soon after its foundation, and in 1901 was elected

to the Tiflis Social Democratic Committee. Follow-

ing the split in the party in 1903, Stalin became a

Bolshevik. For the following decade and a half, he

was involved in a variety of revolutionary activi-

ties, including the publication of illegal materials,

organizational work among workers and within

the party, and bank raids to garner funds to sus-

tain party work. He met Vladimir Lenin in 1905,

and briefly traveled abroad on party business to

Stockholm, London, Kracow, and Vienna. In 1912

he was elected in his absence onto the party Cen-

tral Committee and became an editor of the party

newspaper, Pravda. In 1913 he wrote his most im-

portant early work, Marxism and the National Ques-

tion. His revolutionary work was interrupted by

arrest in 1902, 1909, 1912, and 1913; he escaped

from the first three bouts of exile and returned to

Petrograd from the last one when the tsar fell in

February 1917. In 1903 he married his first wife,

Yekaterina Svanidze, his son Yakov was born in

1904, and his wife died of tuberculosis in 1907.

When Stalin returned to Petrograd soon after

the tsar’s fall, he was one of the leading Bolsheviks

in the city. He was elected to the newly established

Russian bureau of the party and to the editorial

board of Pravda. Along with Vyacheslav Molotov

and Lev Kamenev, he championed the policy of sup-

port for the Provisional Government and a defen-

sist position on the war, until Vladimir Lenin

returned in April and overturned these in favor of

a more revolutionary stance. Stalin went along

with Lenin’s views. During the revolutionary pe-

riod, Stalin seems to have spent most of his time

on organizational work. He was not a stirring

speaker like Trotsky or someone with the presence

of Lenin, and therefore after the return of Lenin and

the emigrés, he was not seen as one of the leading

lights of the party. Nevertheless, following the

seizure of power in October, Stalin became people’s

commissar for nationalities, a position that from

April 1919 he held jointly with the post of people’s

commissar of state control (from February 1920,

the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate). The lat-

ter post was concerned with the elimination of

corruption and inefficiency in the central state ma-

chine. During the civil war, Stalin was active on a

series of military fronts, and it was at this time

that his first major clash with Leon Trotsky oc-

curred. More importantly, when the Politburo,

Orgburo, and Secretariat of the Central Committee

were established in March 1919, Stalin became a

member of all three. He was the only member si-

multaneously of these bodies and the CC, and was

therefore in a place of significant organizational

power. In April 1922 he was elected general secre-

tary of the party, and therefore the formal head of

the party’s organizational machine. With Lenin’s

illness from May 1922 and his death in January

1924, Stalin was able to make use of this power

to consolidate his control at the top of the party

structure.

Lenin’s death was followed by intensified fac-

tional conflict among his would-be successors.

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

1455

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Between 1923 and 1929, Stalin and his supporters

successively outmaneuvered Trotsky and his sup-

porters, the Left Opposition, the United Opposition,

and the Right Opposition, so that by the end of the

decade, Stalin was primus inter pares. Stalin’s suc-

cess in these factional conflicts has usually been

attributed to the organizational powers stemming

from his ability to use the machinery of the party

to promote his supporters and exclude the sup-

porters of his opponents. This was clearly a signif-

icant factor in his ability to outflank his opponents

at party meetings and use those symbolically to de-

feat them through a party vote. Stalin was the

source of jobs, and therefore someone who was at-

tractive to many with ambitions in Soviet politics.

But Stalin was also a person who espoused the sorts

of policies that would have appealed to many rank-

and-file Bolsheviks: The ability of the USSR to build

socialism in one country rather than having to wait

for international revolution and the need to shift

from the gradualist framework of NEP into a more

revolutionary attempt to build socialism, were two

of the most important of such policies. Thus

through a combination of the weaknesses of his

opponents, the strength of his organizational

power, and the attractiveness of many of the po-

sitions he espoused, Stalin was able to triumph over

his more fancied rivals for leadership; he was even

able to overcome the negative evaluation of him in

Lenin’s so-called Testament.

Stalin’s defeat of his more prominent rivals did

not mean that he was secure in the leadership of

the party in the early 1930s. At the end of 1927,

at Stalin’s behest the party adopted the first of a

series of decisions that led to the abandonment of

the moderation of the New Economic Policy and its

replacement by an increasingly rapid pace of in-

dustrialization and agricultural collectivization.

This produced continuing strains within the party,

even when the most prominent opponents of this

new course—the Right Opposition led by Nikolai

Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, and Mikhail Tomsky—

had been defeated in 1929. In late 1930 the Syrtsov-

Lominadze group and in 1932 the Ryutin Platform

were two important instances of high-ranking

party members criticizing the course of economic

policy, with the latter even calling for Stalin’s re-

moval. For many within the party’s leading ranks,

the gamble on forced pace industrialization and

agricultural collectivization, while justifiable in

terms of the achievement of the ultimate goal of a

socialist society, was in practice proving to be more

costly and disruptive than they had been led to be-

lieve. The reports of widespread popular opposition

to collectivization raised the specter of the increased

isolation of the party within the society; the trials

of so-called saboteurs in 1930 and 1931 only in-

creased this sense. They were not reassured by the

increasing glorification of Stalin personally that be-

gan on his fiftieth birthday in December 1929. The

cult of Stalin that thus emerged was clearly an at-

tempt to shift the basis of political legitimacy away

from the party and onto the person of Stalin.

At this time of political uncertainty, in No-

vember 1932 Stalin’s second wife, Nadezhda

Allilueva who he had married in 1919, died. At the

time it was announced that she had died of a heart

attack, but it was widely believed that she had shot

herself. There have also been rumors that Stalin

himself killed her, but the truth is still not known.

In 1933 a party purge, or chistka, was an-

nounced. This was to be a bloodless affair involv-

ing a check on the performance of all party

members and the expulsion of those whose per-

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

1456

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Josef Stalin in January 1946. A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

. R

EPRODUCED BY

PERMISSION

.

formance was found to be deficient. This was fol-

lowed by similar campaigns in 1935 and 1936.

Against this background of suspicion of the true

beliefs and commitment of some party members,

the seventeenth congress of the party was held in

January–February 1934. This congress, the so-called

Congress of Victors, announced the successful

completion of collectivization, and although there

was a significant level of public glorification of

Stalin, there was also evidence of some high-level

dissatisfaction with him. In December of that year,

Leningrad party boss and close associate of Stalin,

Sergei Kirov, was assassinated. Kirov’s death was

used as an excuse to crack down on various elements

including so-called Trotskyites and Zinovievites.

In January 1935, Kamenev, Grigory Zinoviev, and

seventeen other members of a reputed “center” were

tried and convicted of moral and political respon-

sibility for the death of Kirov, and were sentenced

to imprisonment. This wave of purging tapered off

by the middle of 1935. However, it surged once

again in 1936, paradoxically at the time of the

discussion of the new Stalin state Constitution

adopted in December 1936, lasting unabated until

the end of 1938. The so-called Great Terror, sym-

bolized by the show trials of Old Bolsheviks in

August 1936, January 1937, and March 1938, de-

stroyed all semblance of opposition to Stalin and

left him supreme at the apex of the party. He was

now the unchallenged leader of the country, the

vozhd, untrammelled by considerations of collec-

tive leadership, the absolute arbiter of the futures

of all of those who worked with him in the lead-

ership and in the country as a whole.

The personal primacy of Stalin, symbolically

celebrated in a new peak of adulation at the time

of his sixtieth birthday, occurred at a time of in-

creasing international tension. In August 1939 the

Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact was signed,

an agreement that Stalin had actively sought. The

results of that pact were played out in the follow-

ing two years, with Soviet territorial gains on its

western border. In May 1941 Stalin became chair-

man of the Council of People’s Commissars, or

prime minister, to add to his position as General

secretary. The following month, Germany attacked

the Soviet Union, ushering in a new phase in

Stalin’s leadership, that of the war leader.

From the time of the attack, Stalin was closely

involved in organizing the defense of the Soviet

Union. The long public delay in any announcement

from him following the opening of hostilities led

many to claim that Stalin, who had seemingly ig-

nored all warnings about the likelihood of German

attack, had been mentally paralyzed by the attack

and took no part in the initial Soviet response.

However, it has now become clear that Stalin was

busy in meetings during this time, participating as

he did right through the war in the resolution of

issues not just of civil government but of military

strategy and tactics. Throughout the conflict, Stalin

was closely involved in a practical capacity in di-

recting the Soviet war effort. He was also important

symbolically. By mobilizing Russian nationalism

and presenting himself as its personification, Stalin

became the ultimate symbol of both the Soviet pop-

ulace and its armed forces. His refusal to leave

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

1457

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Josef Stalin attends a meeting commemorating the completion

of the first segment of the Moscow subway system in 1935.

© H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

Moscow, even when German troops were at its

gates, reinforced this image. It is probable that the

war ushered in the highest point of Stalin’s real, as

opposed to cult-presented, popularity. Stalin be-

came known as the Generalissimo.

With the end of the war, the Soviet Union was

clearly one of the leading powers remaining and

Stalin was an international figure, as symbolized

by his presence at the conferences with the British

and U.S. leaders in Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam.

He ruled over not only the Soviet Union, but also

the newly established socialist states in Eastern Eu-

rope. At home, there was a return to orthodoxy as

controls were tightened once again following the

relaxation of the wartime period. Stalin’s personal

control remained undiminished. The leadership

functioned as Stalin demanded; formal party or-

gans were largely replaced by loose groupings of

individual leaders summoned at Stalin’s whim and

carrying out whatever tasks he accorded to them.

Always a suspicious man, Stalin’s sense of para-

noia seems to have grown in the post-war period,

something fueled by the Cold War. Although there

were no purges on the scale of the 1930s, the more

limited use of coercion and terror occurred in the

Leningrad affair of 1949–1950, the Mingrelian case

of 1951–1952, and the Doctors’ Plot of 1952–1953.

As in the 1930s, such purging occurred against a

backdrop of the apogee of the Stalin cult at the time

of his seventieth birthday in 1949. In this period,

Stalin was probably more detached from the daily

process of political life than he had ever been. But

this does not mean that he was any less power-

ful; he still set the tenor of political life, and he

was in a position to be able to decide any issue he

wished to decide, which is the true measure of a

dictator. His colleagues, really subordinates, may

have maneuvered among themselves for increased

power and for particular policy positions, but none

challenged his primacy. Stalin died on March 5,

1953, probably of natural causes; some have ar-

gued that some of his leadership colleagues may

have poisoned him, but there has been no evidence

to sustain this accusation.

Both of Stalin’s wives died at an early age, and

he seems to have had difficult relations with his

children. From his second marriage he had a son,

Vasily (b. 1921) and a daughter Svetlana (b. 1926),

both of whom outlived him. Stalin seems to have

had little personal contact with either of these chil-

dren or with Yakov, his son by his first marriage.

Vasily joined the air force during the war and

through his father’s patronage quickly rose to a

leadership position. He subsequently became an al-

coholic. Yakov was in the army and was captured

by the Germans; reports suggest that Stalin refused

a prisoner swap that would have returned Yakov

to him. After Stalin’s death, Svetlana married a cit-

izen of India, and when he died in 1966 she took

his body to India and decided to remain abroad, re-

turning briefly in 1984.

Stalin was the longest-serving leader of the So-

viet Union and clearly left a major imprint on its

development. He has been described as cruel, secre-

tive, manipulative, opportunistic, doctrinaire, para-

noid, devoid of human feelings and sentiment,

single-minded, and power-hungry. All of these de-

scriptions can find sustenance in different aspects

of Stalin’s biography. Where the balance lies re-

mains a matter of debate. What is clear is that when

he believed it was required, he could be ruthless in

the actions he took against both enemies and sup-

posed friends. In this sense, he was a man of ac-

tion. He was not an intellectual, despite the claims

of the cult. His literary output was moderate in

size and generally both turgid in prose and me-

chanical in its arguments, but it did gain the sta-

tus of orthodoxy within the USSR, a function of

his political dominance rather than the intrinsic

merit of his work.

Stalin’s life remains the subject of debate. Many

aspects are still highly controversial, with scholars

disagreeing widely on them. The following are

among the most important of these.

Why was Stalin victorious? This question has

often been posed in a broader form: Why did the

Stalinist system emerge in the Soviet Union, the

first attempt to create a socialist society on a na-

tional scale? Debate on this question has been vig-

orous precisely because of the implications its

answer was seen to have for socialist aspirations

more generally. Many, particularly on the right of

the political spectrum, argued that such a system

was a logical, even inevitable, result of revolution

and the sort of system that Lenin set in place. Oth-

ers argued that, while the Leninist system may

have made a highly coercive, undemocratic system

more likely, this was neither the necessary nor in-

evitable outcome of either the revolution or Lenin-

ism. Many argued the primacy of organizational

factors, especially the power Stalin was able to gain

and exercise within the party apparatus. Others

emphasized the importance of Stalin’s personality,

skills, and talents, especially in contrast to those of

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

1458

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

his opponents. Another strand of argument focused

upon the regime’s desire to bring about substan-

tial socioeconomic change in an economically and

politically backward society, a situation requiring

a high level of centralization and coercion. Others

noted the role of the party’s isolation in Soviet so-

ciety and the nature of the recruits flowing into its

ranks. This question remains unresolved, but an

answer, most now agree, involves elements of all

of the arguments noted above.

Was Stalin responsible for Kirov’s assassina-

tion? Those supporting the view that Stalin was re-

sponsible argue that Kirov was seen as a possible

challenge to or replacement for Stalin, and accord-

ingly Stalin had him assassinated. Other suggestions

have been that Kirov’s killer was indeed working

for a bloc of oppositionists as Stalin and his sup-

porters claimed, that he was working alone, or that

it was the security apparatus who had planned a

failed assassination attempt to boost their institu-

tional stocks but that this went wrong. Despite re-

search in the archives, no definitive answer has been

forthcoming, and all cases remain circumstantial.

There is now no doubt about Stalin’s respon-

sibility for the terror. This was not a normal party

purge that went off the rails. Given Stalin’s posi-

tion in the party organization and the position oc-

cupied by his supporters, this could not have gone

ahead without his permission. He probably did not

have an exact idea of how many people suffered

during the terror, but he must have had an idea of

the general dimensions, and he certainly knew of

some of the individuals who perished, because he

signed lists of victims submitted to him. Ultimately

Stalin was responsible, even if the primary role in

the direction of it lay with his henchmen.

Was Stalin planning another major purge when

he died? Those who argue in favor of this point to

the buildup of pressure through the Leningrad af-

fair, the Mingrelian case, and the Doctors’ Plot, and

the enlargement of the party Presidium at the nine-

teenth congress of the party in October 1952. This

was seen as preparatory to purging some of the

older established leaders and bringing newer ones

forward. Many of those who accept this logic also

accept that Stalin was poisoned. There is no firm

evidence about Stalin’s intentions either way, and

unless compelling evidence comes from the archives,

this will remain a moot point.

Finally there is the question of the costs and

benefits of Stalin and his regime. Under his rule,

the Soviet Union moved from being a backward,

predominantly agricultural country to one of the

two superpowers on the globe. The living standards

of many of its people rose significantly, as did lit-

eracy and education levels. Urbanization trans-

formed the landscape. And the Soviet Union won

the war against Hitler, something that would have

been highly unlikely without high-level industrial-

ization. But critics point to the costs: millions killed

as a result of famine, terror, and collectivization;

the massive wastage of resources; the establish-

ment of an economic system that ultimately could

not sustain itself; the development of a society

which crushed individual initiative and free think-

ing. This was an ambiguous legacy, and one that

therefore was difficult for the regime to handle. Un-

der Khrushchev, destalinization was a limited pol-

icy that refused to come to grips with the reality

of the Stalin regime. When discussion was again

permitted, under Mikhail Gorbachev, the political

circumstances of the time prevented a balanced

evaluation from emerging. Russia still must broach

this question, but it is likely that this will only hap-

pen in a satisfactory way when the Stalin issue is

not seen to have contemporary political relevance.

That may be some time off.

See also: COLD WAR; COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICUL-

TURE; CULT OF PERSONALITY; DE-STALINIZATION;

ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; INDUSTRIALIZATION,

SOVIET; KIROV, SERGEI MIRONOVICH; NAZI-SOVIET

PACT OF 1939; PURGES, THE GREAT; SHOW TRIALS;

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gill, Graeme. (1990). The Origins of the Stalinist Political

System. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hingley, Ronald. (1974). Joseph Stalin: Man and Legend.

New York: McGraw-Hill.

Tucker, Robert C. (1973). Stalin as Revolutionary

1879–1929: A Study in History and Personality. Lon-

don: Chatto & Windus.

Tucker, Robert C. (1990). Stalin in Power: The Revolution

from Above, 1928–41. New York: Norton.

Ulam, Adam B. (1989). Stalin: The Man and His Era.

Boston: Beacon.

Volkogonov, Dmitri. (1991): Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy.

New York: Grove.

G

RAEME

G

ILL

STALIN REVOLUTION See INDUSTRIALIZATION,

SOVIET.

STALIN REVOLUTION

1459

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

STANISLAVSKY, KONSTANTIN

SERGEYEVICH

(1863–1938), actor, director, acting teacher.

The first creator of a comprehensive guide to ac-

tor training, Stanislavsky emerged as one of the most

influential theater personalities of the twentieth

century. His work continues to shape theatrical dis-

course into the twenty-first century.

Born Konstantin Sergeyevich Alexeyev to the

wealthy Alexeyevs, he first performed in a fully

equipped home theater outside Moscow. Because of

his social class, he limited his theatrical ambitions

to the amateur sphere. In 1888 he founded The

Society of Art and Literature, a critically acclaimed

theater club, where he established himself as an out-

standing actor and emerging director. As his talents

became known, he adopted “Stanislavsky” (1884)

to protect his family name. In 1897 Vladimir Ne-

mirovich-Danchenko, playwright and head of the

only acting school in Moscow, invited Stanislavsky

to cofound The Moscow Art Theater (MAT) as a

professional venture. The two agreed to produce

plays of contemporary import, bring European

stage realism to Russia, and ensure that the work

of directors, designers, and actors would embrace

unified dramatic visions. The theater opened with

an historically researched production of Alexei

Tolstoy’s Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich (1898). Anton Che-

khov’s The Seagull (1898) secured the company’s

fame. Stanislavsky directed and acted in productions

such as premieres of Chekhov’s plays (1898–1904),

Henrick Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People (1902), and

Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths (1902).

In 1906 Stanislavsky lost inspiration as an ac-

tor and retreated to Finland in despair. The crisis

induced his passionate desire to systematize acting.

He devoted the rest of his life to collecting, devel-

oping, and teaching ways to control inspiration.

His “System” went through continuous evolution

incorporating the experience of great actors, be-

haviorist psychology, yoga, and other sources that

illuminate the creative process. Stanislavsky’s ex-

perimental stance caused friction, which ignited in

1909 when he applied his ideas to Ivan Turgenev’s

A Month in the Country. Nemirovich’s hostility

prompted Stanislavsky to transfer his experiments

into a series of studios, adjunct to the main com-

pany, even as he continued to act and direct at

MAT. The First Studio, founded in 1911, became

his most famous laboratory, because it laid the Sys-

tem’s foundation.

With the Bolshevik revolution, Stanislavsky

and MAT were reduced to poverty. From 1922 to

1924, Stanislavsky toured Europe and the United

States with the company’s earliest and most fa-

mous productions in an effort to recoup financial

stability. During this period, he also began to write,

publishing My Life in Art in 1924. This period guar-

anteed his international influence.

Upon returning to Moscow, Stanislavsky faced

growing Soviet control over the arts. His connec-

tions with the West and his production of Mikhail

Bulgakov’s play about White Russians, The Days of

the Turbins (1926), came under attack. From 1934

to 1938, during the Soviet purges, Stanislavsky

was weakened by an enlarged heart and confined

to his home. Stalin simultaneously canonized the

director’s realistic work as the vanguard of Social-

ist Realism. Isolated from the wider world, Stanislav-

sky continued to write, teach, and develop his ideas

in his home until his death in 1938 of a heart at-

tack.

See also: BULGAKOV, MIKHAIL AFANASIEVICH; CHEKHOV,

ANTON PAVLOVICH; MOSCOW ART THEATER; SOCIAL-

IST REALISM; THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benedetti, Jean. (1990). Stanislavski: A Biography. New

York: Routledge.

Carnicke, Sharon Marie. (1998). Stanislavsky in Focus.

London: Harwood/Routledge.

Smeliansky, Anatoly. (1991). “The Last Decade:

Stanislavsky and Stalinism.” Theatre 12(2):7–13.

S

HARON

M

ARIE

C

ARNICKE

STARCHESTVO See SPIRITUAL ELDERS.

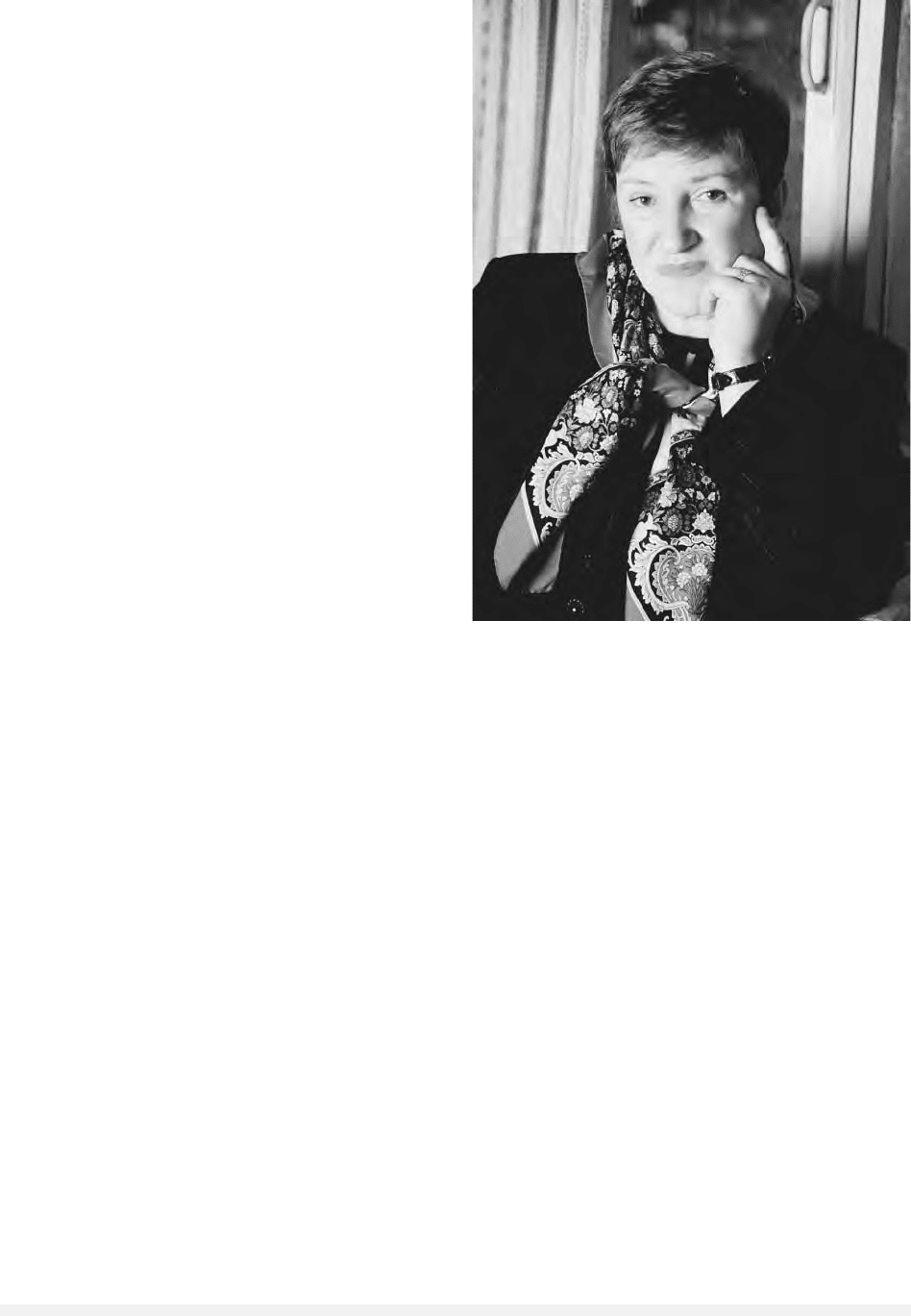

STAROVOITOVA, GALINA VASILIEVNA

(1946–1998), martyred political figure and human

rights activist.

Galina Starovoitova was one of Russia’s lead-

ing human rights advocates and served in the first

post-Soviet Russian government. Murdered by un-

known assailants on November 20, 1998, in St. Pe-

tersburg, she was eulogized as “a symbol of

courage and outspokenness,” “one of the brightest

lights of Russian independence and reform move-

STANISLAVSKY, KONSTANTIN SERGEYEVICH

1460

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ment,” and a leader with an “uncompromising ded-

ication to democracy.”

Starovoitova was born in Chelyabinsk, earned

B.A. and M.A. degrees in social psychology, and in

1980 received a Ph.D. from the Institute of Ethnog-

raphy, USSR Academy of Sciences. She worked as

an ethnographer and psychologist, and published

scientific works in both fields, with a specializa-

tion in inter-ethnic relations and cross-cultural

studies.

Her political activities began in the late 1980s

with the Moscow Helsinki Group, a human rights

organization led by Andrei Sakharov and other

prominent dissident leaders. She joined with

Sakharov to campaign for the rights of Armenians

in the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, and in 1989,

in appreciation, was elected to the USSR Congress

of Peoples’ Deputies from Yerevan, the capital of

Armenia. The Congress elected her to serve in the

Supreme Soviet, where she became one of the co-

founders of the pro-reform Inter-Regional Group

of Deputies. A year later, she was elected to the

Russian parliament from a constituency in St. Pe-

tersburg and became a co-chair of the Democratic

Russia Party.

After the USSR collapsed, Starovoitova became

an adviser to President Boris Yeltsin on inter-

ethnic affairs, but she resigned in 1992 because of

disagreements over policy in the Caucasus region

and frustration with a government still beholden

to elements of the old Soviet system. From 1993

to 1994 she was a fellow at the U.S. Institute of

Peace in Washington, D.C., and the following year

she taught at Brown University.

In 1995 Starovoitova was elected to the Rus-

sian Duma, where she became a prominent spokes-

woman on human rights, the war in Chechnya,

the environment, women’s rights, wage issues,

housing, antisemitism, and religious freedom. In

1996, she ran for the presidency, the first Russian

woman to do so. She talked of running again in

2000, and before her death announced that she

would run for governor of Leningrad oblast. Sta-

rovoitova saw Russia’s communists and national-

ists as standing in the way of democratization, and

they in turn were her main opponents. Shortly be-

fore her death, she spoke out forcefully about po-

litical corruption, and many speculate that her

investigations in this area precipitated her murder.

Millions of Russians mourned Galina Starovoi-

tova’s death, and a kilometer-long line of people

waited in the cold to pay their respects. The inves-

tigation of her murder was turned over to the high-

est authorities, but despite the interrogation of

hundreds of witnesses, the detention of hundreds

of suspects, and pledges to catch those guilty of the

crime, no one was charged. Several Russians view

the murder as a political assassination perpetrated

either by organized crime or corrupt political offi-

cials.

See also: ORGANIZED CRIME; SAKHAROV, ANDREI

DMITRIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Diuk, Nadia. (1999). “Galina Starovoitova.” Journal of

Democracy 10:188–190.

Powell, B. (1998). “Requiem for Reform.” Newsweek.

December 7, 1998, p. 38.

P

AUL

J. K

UBICEK

START See STRATEGIC ARMS REDUCTION TALKS.

START

1461

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Democratic activist Galina Starovoitova was murdered outside

her apartment in St. Petersburg. © ANTONOV/RPG/CORBIS SYGMA

STASOVA, YELENA DMITRIEVNA

(1873–1966), Bolshevik, secretary of the Central

Committee of the Russian Communist Party,

1919–1920.

Yelena Stasova belonged to a prominent St. Pe-

tersburg intelligentsia family. In the early 1900s

she became a secretary of the illegal St. Petersburg

committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor

Party. Stasova was an effective administrator and

conspirator, as well as a staunch supporter of

Vladimir Lenin. Arrested in 1907, she spent the

next ten years in exile, first in the Caucasus and

then in Siberia.

After the revolution, in 1917 and 1918, Stasova

was a secretary of the Petrograd party committee.

She chose to concentrate on the mundane but cru-

cially important work of administration, keeping

records, dispersing funds, and handing out job as-

signments. In 1919, when Central Committee Sec-

retary Yakov Sverdlov died, Lenin tapped Stasova to

replace him. She struggled to improve the organi-

zation of the party’s central administration, but her

efforts did not dispel charges of chronic inefficiency

in the Secretariat. In 1920, Lenin responded by re-

placing Stasova with three male secretaries. She left

the party leadership having played an important

part in building the Communist Party’s apparatus.

For the rest of her long life Stasova took in-

significant assignments. In the 1930s she headed

the International Organization for Aid to Revolu-

tionaries. Her obscurity probably helped her sur-

vive the party purges and aid some of its victims.

In the 1950s and 1960s she published several ver-

sions of her memoirs, all dedicated to restoring the

reputation of the party’s founders. Stasova died of

natural causes.

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION; FEM-

INISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clements, Barbara Evans. (1997). Bolshevik Women. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

B

ARBARA

E

VANS

C

LEMENTS

STASOV, VLADIMIR VASILIEVICH

(1824–1906), music and art critic whose aesthet-

ics of realist and national expression in the arts

served as a model for socialist realism.

Born into a prominent upper-class family (his

father was a noted architect), Vladimir Stasov grad-

uated in 1843 from the elite St. Petersburg School

of Jurisprudence and also studied piano. After a pe-

riod in various undistinguished civil service jobs, he

was appointed secretary to Prince Antaoly N. Demi-

dov in 1851 and spent almost three years in the

West, mostly in Florence. Back in Russia he found

employment in the Imperial Public Library in the

capital, and from 1872 until his death he headed

its arts department.

Stasov’s voluminous writings consist of polem-

ical feuilletons, monographs on individual musicians

and painters, and long overviews of developments

in the arts (both in Russia and the West), as well as

on Russian architecture and archeology. Inspired by

the radical literary critic Vissarion Belinsky, Stasov

promoted realist and national artistic forms that

would engage the public in current social and his-

torical issues. His original, liberal, and open-minded

stance in opposition to the regnant academicism in-

vigorated the cultural scene. But by the 1890s his

aesthetics had turned conservative and chauvinistic,

condemning as decadent the new artistic trends that

were challenging national realism, which had by

then become a new form of academicism.

With the publication of his monograph on

Mikhail Glinka in 1847, which stressed the com-

poser’s originality in using folk motifs, Stasov be-

gan to advocate Russianness in music. Thereafter he

consistently championed young, independent com-

posers—Miliy A. Balakirev, Alexander P. Borodin,

César A. Cui, Modest P. Musorgsky, and Nikolai A.

Rimsky-Korsakov—whom he jointly called “The

Mighty Five” (moguchaya kuchka). They all were

self-taught, opposed the hidebound rules of the con-

servatory, and strove to create, in Glinka’s foot-

steps, a distinctly Russian school of music. Stasov

supported these composers with polemical publica-

tions and contributed significantly to their creative

work, suggesting topics, supplying historical doc-

umentation, and commenting on compositions. He

was especially close to Musorgsky, whose genius

he was the first to recognize.

In the 1860s Stasov began to comment regu-

larly on the situation in the pictorial arts, ques-

tioning the authority of the Imperial Academy of

Arts with its Italianate tastes. Instead, he advocated

art that depicted Russian subjects in a manner that

would instruct the public about the country’s re-

alities. He became closely associated with young

painters who in 1863 had quit the academy in

protest against its outdated routines and in 1871

STASOVA, YELENA DMITRIEVNA

1462

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY