Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Mir, including seven American astronauts between

1995 and 1998. The station, which was initially

scheduled to operate for only five years, supported

human habitation until mid-2000, before making a

controlled atmosphere reentry on March 23, 2001.

The Soviet Union in the 1980s developed a large

space launch vehicle, called Energiya, and a reusable

space plane similar to the U.S. space shuttle, called

Buran. However, the Soviet Union could no longer

afford an expensive space program. Energiya was

launched only twice, in 1987.

To continue its human space flight efforts, Rus-

sia in 1993 joined the United States and fourteen

other countries in the International Space Station

program, the largest ever cooperative technological

project. Two Russian cosmonauts were members

of the first crew to live aboard the station, arriv-

ing in November 2000, and it is intended that at

least one cosmonaut will be aboard the station on

a permanent basis. Russian hardware plays an im-

portant role in the orbiting laboratory. Russia’s role

was increased when the U.S. space plane Challenger

burned up on entry in February 2003. The Soyuz

“lifeboat” became the only way in or out until reg-

ular U.S. flights were resumed.

In addition, the Soviet Union has carried out a

comprehensive program of unmanned space science

and application missions for both civilian and na-

tional security purposes. Spacecraft were sent to

Venus and Mars. Other spacecraft provided intelli-

gence information, early warning of missile attack,

and navigation and positioning data, and were used

for weather forecasting and telecommunications.

In contrast to the United States, the Soviet

Union had no space agency. Various design bu-

reaus had influence within the Soviet system, but

rivalry among them posed an obstacle to a coher-

ent Soviet space program. The Politburo and the

Council of Ministers made policy decisions. After

1965, the government’s Ministry of General Ma-

chine Building managed all Soviet space and mis-

sile programs; the Ministry of Defense also shaped

space efforts. A separate military branch, the

Strategic Missile Forces, was in charge of space

launchers and strategic missiles. Various institutes

of the Soviet Academy of Sciences proposed and

managed scientific missions.

After the dissolution of the USSR, Russia cre-

ated a civilian organization for space activities, the

Russian Space Agency, formed in February 1992.

It quickly took on increasing responsibility for the

management of nonmilitary space activities and, as

an added charge, aviation efforts. It later was re-

named the Russian Aviation and Space Agency.

See also: GAGARIN, YURI ALEXEYEVICH; INTERNATIONAL

SPACE STATION; MIR SPACE STATION; SCIENCE AND

TECHNOLOGY POLICY; SPUTNIK; TSIOLKOVSKY, KON-

STANTIN EDUARDOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dickson, Paul. (2001). Sputnik: The Shock of the Century.

New York: Walker.

Hall, Rex, and Shayler, David J. (2001). The Rocket Men:

Vostok and Voshkod, the First Soviet Manned Space-

flights. New York: Springer Verlag.

Harvey, Brian. (2001). Russia in Space: the Failed Fron-

tier? New York: Springer Verlag.

Oberg, James. (1981). Red Star in Orbit. New York: Ran-

dom House.

Russian Aviation and Space Agency web site. (2002).

<http://www.rosaviakosmos.ru/english/eindex

.htm>.

Siddiqi, Asif. (2000). Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union

and the Space Race, 1945–1974. Washington, DC:

Government Printing Office.

J

OHN

M. L

OGSDON

SPANISH CIVIL WAR

In July 1936, after months of unrest and politi-

cally motivated assassinations, a junta of nation-

alist generals, including Francisco Franco, led an

uprising against the Spanish Republic. When Franco

had difficulty transporting his forces from Africa

to Spain, he appealed for aid from Germany and

Italy. Hitler and Mussolini were only too happy to

oblige. The Republicans also asked for help from

the Western powers and the Soviet Union. Britain,

France, and the United States decided to adopt a

strict policy of nonintervention, but Josef Stalin be-

gan secretly supplying the Republic with the

weapons it needed to survive.

Soviet aid, however, came with a price. Stalin

provided thousands of Red Army, NKVD, and GRU

(secret police) officers who often furthered his aims

while acting as advisers for the Republicans. Mean-

while the Spanish government shipped its vast gold

reserves to Moscow, where the Soviets deducted the

cost of armaments for the war, at exorbitant prices,

from the bullion. Yet without Soviet tanks and

SPANISH CIVIL WAR

1443

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

airplanes it is certain that the Republic would have

fallen much more quickly than it did.

Stalin and the Stalinist Spanish Communist

Party wanted a say over the political future of

Spain. From the start of the war, the Soviets pushed

the Republicans to eliminate anyone who did not

follow the party line. This hunt for Trotskyists was

tolerated by the Republican governments in order

to retain the favor of their only great power sup-

porter. Most Spanish leaders, however, were able

to resist Soviet attempts to interfere in the internal

affairs of their country, and steered their own

course during the war.

The Soviet Union and the Comintern also took

a direct hand in combat. The European Left sent

more than 30,000 enthusiastic volunteers to fight

for the Republicans, some of whom came to Spain

to support a revolution, on the model of the Soviet

Union, while others wanted only to defend democ-

racy. A large number of the commanders for these

International Brigades were regular Red Army of-

ficers, although their origins were disguised and

never acknowledged by the Soviet Union. The In-

ternationals, and armaments sent by the Soviets,

were critical for the Republicans’ successful defense

of Madrid in December 1936. The Republican cause

also benefited from Soviet and International par-

ticipation in other engagements, including the bat-

tle of Jarama in February 1937 and the defeat of

Italian troops at Guadalajara in March 1937, while

Soviet tank operators and pilots were of crucial im-

portance throughout the war.

Of the Soviet soldiers who saw action in the

Spanish arena, dozens were recalled to Moscow and

executed during the military purges of 1937–1939.

At the same time others, such as Konstantin

Rokossovsky, Ivan Konev, Alexander Rodimtsev,

and Nikolai Kuznetsov, had brilliant careers during

World War II and after.

In the end, Soviet aid could not alter the out-

come of the war. As the international climate wors-

ened, Stalin decided to withdraw support for the

Spanish government in 1938 and by the end of the

year could only offer his condolences as the Re-

public faced utter defeat.

See also: COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL; STALIN, JOSEF

VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alpert, Michael. (1994). A New International History of the

Spanish Civil War. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Howson, Gerald. (1998). Arms for Spain: The Untold Story

of the Spanish Civil War. London: J. Murray.

Radosh, Ronald, and Habeck, Mary R., eds. (2001). Spain

Betrayed: The Soviet Union in the Spanish Civil War.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Thomas, Hugh. (1977). The Spanish Civil War. New York:

Harper and Row.

M

ARY

R. H

ABECK

SPECIAL PURPOSE FORCES

The twentieth century saw a great upsurge in the

interest in and use of military special forces, both

in war and for peacekeeping, antiterrorist, and

other missions. The Soviets were ardent advocates

of such forces, and created many, tasked with a

large and varied array of missions. This reflected

three main considerations. First of all, small, highly

motivated and well-trained units were vital to carry

out operations beyond the capabilities of the USSR’s

mass conscript army, which demanded speed, pre-

cision, or finesse. Secondly, the Soviets approached

warfare in an intensely political way, seeing the

aim as being not necessarily to win on the battle-

field, but to destroy the enemy’s will and ability to

fight in the first place. Special forces could play a

key role in this. Thirdly, the Soviets regarded their

armed forces also as integrated elements of their

apparatus of rule, and specialized forces emerged

to meet particular needs that had less to do with

war-fighting but political control. The post-Soviet

regime has upheld this tradition. Indeed, the pro-

portion of special purpose units within the Russian

military actually increased, not least because at a

time when the majority of the armed forces were

virtually unusable, at least these elements retained

the discipline, training, and morale to fight.

Special forces of a fashion had existed during

the civil war (1918–1921), including the elite Lat-

vian Rifles who guarded Vladimir Lenin, but these

units tended to be essentially ad hoc elements of

Bolshevik militants and Cossack horsemen. They

subsequently either dissolved or were incorporated

into the Red Army or police, losing their identity

and élan in the process. The true genesis of Soviet

special purpose forces took place in 1930, when the

USSR became only the second nation in history to

experiment with a military parachute drop. Excited

by the possibilities, the Soviet high command im-

mediately began training paratroop units: The first

battalions were formed a year later.

SPECIAL PURPOSE FORCES

1444

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

This was the genesis of the Air Assault Troops,

this also led to the rise of true special purpose

forces. After all, while the paratroopers and other

formations such as the Naval Infantry (marines)

were a cut above the regular conscript infantry,

they could hardly be considered “special forces” in

the modern sense of the term. As the army began

raising its paratroop forces, so too smaller, more

specialized units began to be created within them,

given the name Special Designation forces (Spet-

sialnogo naznacheniya, Spetsnaz for short). Elite

units were also formed by the NKVD, the political

police force (which had a sizable parallel army of

paramilitaries), that instead called its forces Osnaz,

for Osobennogo naznachneniya, or Specialized Desig-

nation. During World War II, these forces would

see extensive action. Army and navy reconnais-

sance commandos penetrated German lines and,

along with NKVD Osnaz saboteurs and infiltrators,

organized partisan units, targeted collaborators and

attacked supply routes.

This duality continued after the war and into

the post-Soviet era. The armed forces maintain sub-

stantial Spetsnaz forces under the overall command

of the GRU, military intelligence. Their main roles

are to operate behind enemy lines gathering intel-

ligence and launching surprise attacks on strategic

assets such as headquarters and nuclear weapons.

There are eight brigades of regular Spetsnaz and

four of Naval Spetsnaz. However, most of these os-

tensibly elite units are still largely manned by con-

scripts, albeit the pick of the draft. There is thus an

elite within the elite, largely made up of profes-

sional soldiers. Generally a single company within

each brigade is kept at this standard, as well as a

company in each of the paratroop divisions. These

elements include athletes and linguists trained to

pass themselves off as nationals of target nations

and are genuinely comparable to such units as the

U.S. Green Berets or British SAS.

Meanwhile, the security apparatus also retains

its own smaller Osnaz elements. The KGB created

several specialized teams, including Alfa (an anti-

terrorist strike force), Zenit and Vympel (trained for

secret missions abroad), and Kaskad (a covert in-

telligence team). All served during the war in Af-

ghanistan (1979–1989), and all survived the end of

the USSR and the dismemberment of the KGB, be-

ing attached to new, Russian security agencies. The

same is true of the Osnaz elements within the In-

terior Troops and the security arm of the Ministry

of Internal Affairs, as well as the Border Troops. In-

deed, it has become almost a mark of institutional

prestige to have such units, so they have also been

joined by such new units as the Justice Ministry’s

Fakel commando team (which specializes in break-

ing prison sieges). Thus, if anything, special pur-

pose forces are becoming even more important in

the post-Soviet era.

See also: MILITARY INTELLIGENCE; STATE SECURITY, OR-

GANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Galeotti, Mark. (1992). “Special and Intervention Forces

of the Former Soviet Union.” Jane’s Intelligence Re-

view 4:438-440.

Schofield, Carey. (1993). The Russian Elite. London:

Greenhill.

Strekhnin, Yuri. (1996). Commandos from the Sea. An-

napolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

Suvorov, Viktor. (1987). Spetsnaz. London: Hamish

Hamilton.

Zaloga, Steven. (1995). Inside the Blue Berets. Novato, CA:

Presidio.

M

ARK

G

ALEOTTI

SPERANSKY, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH

(1772–1839), Russian statesman, one-time adviser

to Tsar Alexander I.

Mikhail Speransky attempted during the years

1807–1811 to influence the Russian monarch in

the direction of instituting major political reform

in Russia’s government. Only a few of his carefully

drafted plans ever saw the light of day.

Born into a family of a poor Russian Orthodox

clergyman, Speransky, called by one Russian his-

torian a “self-made man,” won the attention of the

tsar and rose to become a count. He was consid-

ered brilliant and well-read in the study of Euro-

pean governmental structures, becoming in effect

Alexander’s unofficial prime minister. Working in

secret (on the tsar’s orders), he drew up a number

of reforms. His idea, which the tsar evidently did

not wholly endorse, was to retain a strong monar-

chy but reform it so that it would be based strictly

on law and legal procedures of the type found in

some European monarchies of the time.

Speransky’s reform plans did not closely re-

semble, say, the English or French governmental

SPERANSKY, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH

1445

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

systems. Yet while Speransky could probably not

be considered a liberal reformer on West European

terms, by Russian standards his reformism bor-

dered on the radical. This made Speransky ex-

tremely unpopular with the tsar’s court, causing

the tsar to keep such plans under wraps lest they

unduly alienate his court.

In 1809 and 1812, Speransky drew up the draft

of a Russian constitution that bore some resem-

blance to those of West European monarchies. In

one of his projects Speransky even proposed sepa-

ration of the powers of legislature (in the Duma),

judiciary, and the governmental administration.

Yet all three were to branch out from the crown.

Suffrage would be based on property, at least in

the beginning. Election of the Duma would be in-

direct and necessitate a cautious, four-stage elec-

toral process. Speransky also supported a program

for future abolition of serfdom in Russia, reform

that he viewed as crucial for any serious top-to-

bottom governmental change.

Historians note that certain measures enacted

in 1810–1811 brought “fundamental change to the

executive departments of government.” Personal re-

sponsibility, it is noted, was to be imposed on min-

isters, while the functions of executive departments

were precisely delimited. Unwarranted interference

with legislative and judicial functions would be

eliminated. Comprehensive rules were actually en-

acted for the administration of the ministries.

Although Speransky’s efforts to reform the an-

tiquated Russian court system failed, his adminis-

trative reforms overall modernized the whole

bureaucratic machine. These structures remained in

effect until the Bolshevik coup d’état, or October

Revolution, of late 1917.

After serving as the tsar’s close adviser for some

five years, Speransky left St. Petersburg as the ap-

pointed Governor-General of the Siberian region. In

that post he continued to author reform plans.

Some of these were adopted and changed the gov-

ernmental structure of that large administrative

area. But it was in the period of his service as the

tsar’s adviser that Speransky made his name in the

annals of Russian history, especially as recounted

by the famous early nineteenth-century Russian

historian, Nikolai M. Karamzin.

In 1821 Speransky returned to the Russian cap-

ital to become a founder of the Siberian Commit-

tee for Russian Affairs Beyond the Urals.

See also: ALEXANDER I; WESTERNIZERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Raeff, Marc. (1956). Siberia and the Reform of 1822. Seat-

tle: University of Washington Press.

Raeff, Marc. (1957). Michael Speransky, Statesman of Im-

perial Russia, 1772–1839. The Hague: M. Nijhoff.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (1963). A History of Russia.

New York: Oxford University Press.

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

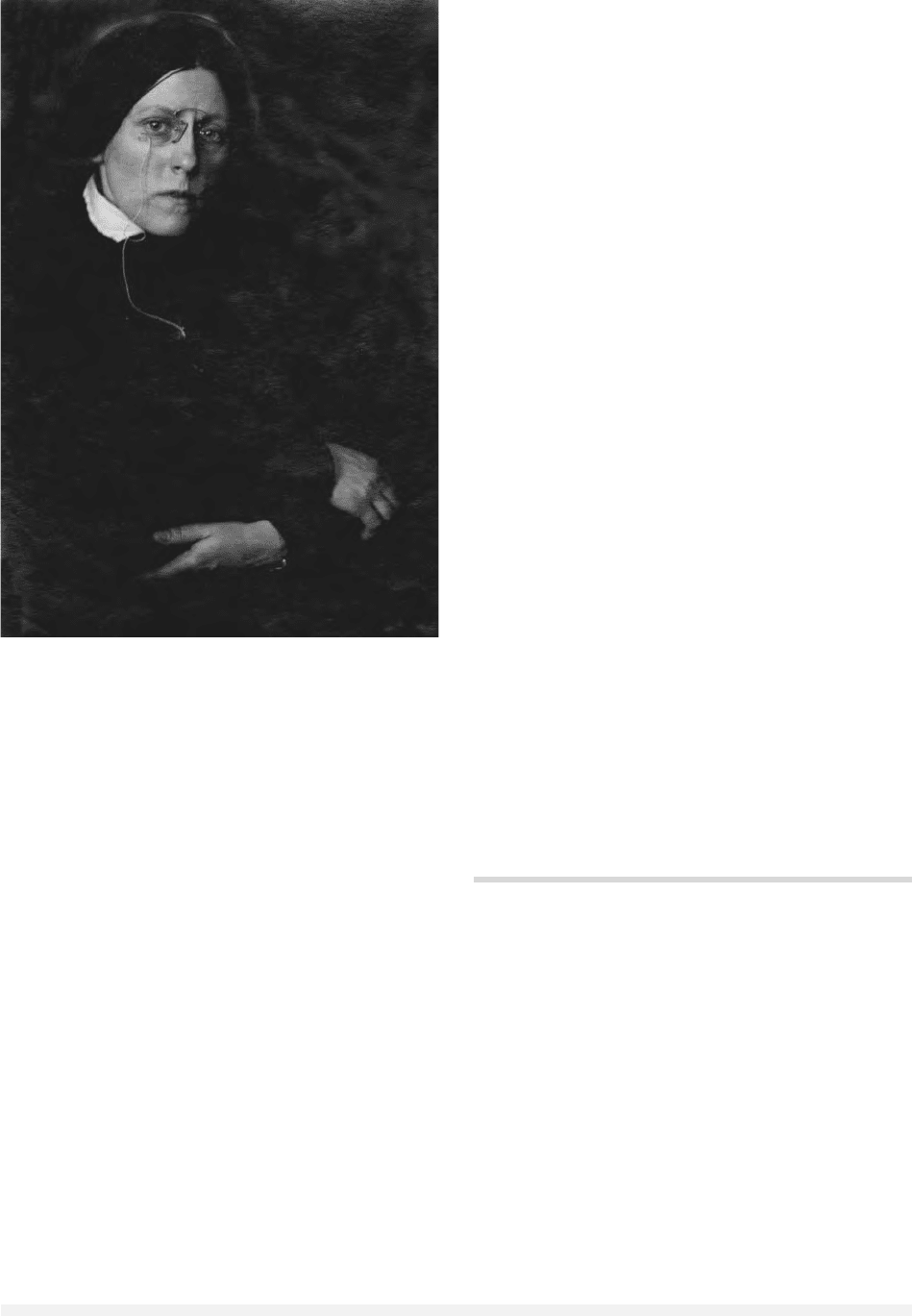

SPIRIDONOVA, MARIA ALEXANDROVNA

(1884–1941), Socialist Revolutionary terrorist and

Left Socialist Revolutionary leader who spent most

of her life in prison or exile because of her popu-

lar appeal as a revolutionary heroine.

Maria Spiridonova, daughter of a non-hereditary

noble in Tambov Province, became a public sym-

bol of heroic martyrdom during the first Russian

revolution of 1905–1907. In January 1906 she

shot provincial councilor G. N. Luzhenovsky at the

Borisoglebsk Railroad Station, carrying out the

death sentence that the Tambov Socialist Revolu-

tionaries (SRs) had passed on Luzhenovsky for his

cruel suppression of peasant unrest in the district.

Spiridonova’s case excited national interest, thus

distinguishing her from the many other SR terror-

ists throughout the empire. A letter Spiridonova

wrote from prison was published in a liberal news-

paper and debated widely in the national press be-

cause it described her torture at the hands of police

officials, hinting as well at sexual abuse. Liberal

newspapers in particular waxed eloquent about the

brutalities inflicted on this beautiful and chaste

young woman of the Russian upper classes who

had killed a sadistic bureaucrat.

In March 1906, however, a court-martial sen-

tenced Spiridonova to hanging, then commuted her

sentence to life imprisonment, the usual practice in

cases of females convicted of political crimes until

mid-1906. Eleven years of incarceration in the

Nerchinsk penal complex in Siberia followed, dur-

ing which Spiridonova suffered from depression,

nervous prostration, and frequent flareups of tu-

berculosis, her chronic illness. The Provisional Gov-

ernment’s amnesty of all political prisoners shortly

after the February Revolution allowed Spiridonova

to return to European Russia in the spring of 1917.

Here she was welcomed, given her reputation as

heroine and martyr, into the highest level of revo-

lutionary politics in Petrograd and Moscow.

SPIRIDONOVA, MARIA ALEXANDROVNA

1446

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

As a leader of the Left SR Party, Spiridonova

employed the aura of her martyrdom, along with

her personal charisma and oratorical skills, to sway

peasants, workers, and soldiers against the Provi-

sional Government and to popularize the October

Revolution. While she did not hold an official post

in the first Soviet government, a Bolshevik-Left SR

coalition, she was elected chairperson of the Peas-

ant Section of the Central Executive Committee

(VTsIK) of the second, third, and fourth Soviet Con-

gresses. Indeed it was her lifelong concern for the

peasants and their welfare that ultimately turned

Spiridonova against the Bolsheviks.

Spiridonova had been an early supporter of

Vladimir Lenin’s push to sign a separate peace with

Germany, however punitive, because the Russian

population was opposed to continuing the war. She

adhered to this position despite her party’s objec-

tions to the “shameful” Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and

withdrawal from the government in protest in

March 1918. But when Russian concessions to

Germany led to a food supply crisis that the

Bolsheviks attempted to resolve with stringent

grain-procurement measures in May, Spiridonova

repudiated the treaty along with Bolshevik policy.

She took a leading role in planning the Left SRs’ as-

sassination of the German ambassador, an attempt

to break the treaty and spark a popular uprising

that was aborted by the Bolsheviks in July. With

her party’s consequent banishment from Soviet

politics, a second martyrdom began for Spiri-

donova. From 1920 on she lived either in prison,

under house arrest, in Central Asian exile, or in

sanatoria, up to her execution on Josef Stalin’s or-

ders during the German invasion in 1941.

See also: BREST-LITOVSK PEACE; LEFT SOCIALIST REVOLU-

TIONARIES; SOCIALIST REVOLUTIONARIES; TERRORISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Rabinowitch, Alexander. (1995). “Maria Spiridonova’s

‘Last Testament.’” Russian Review 54(3):424–446.

Radkey, Oliver H. (1958). The Agrarian Foes of Bolshevism:

Promise and Default of the Russian Socialist Revolu-

tionaries, February to October 1917. New York: Co-

lumbia University Press.

Radkey, Oliver H. (1963). The Sickle under the Hammer:

The Russian Socialist Revolutionaries in the Early

Months of Soviet Rule. New York: Columbia Univer-

sity Press.

Steinberg, Isaac. (1935). Spiridonova: Revolutionary Ter-

rorist. tr. and eds. Gwenda David and Eric Mos-

bacher. London: Methuen.

S

ALLY

A. B

ONIECE

SPIRITUAL ELDERS

The spiritual elder (starets in Russian, geron in Greek)

first appeared in the earliest days of monasticism in

Asia Minor. Some elders had far-ranging reputa-

tions and attracted other monks who emulated their

way of life, sought their counsel, and profited from

their experience in acquiring the Holy Spirit. One of

the signs of the Spirit is the gift of discernment (dio-

rasis), which means, first, knowledge of the mys-

teries of God, and, second, an understanding of the

secrets of the heart. One who has the gift of dis-

cernment can undertake the spiritual direction of

others. In the opinion of some Eastern writers, the

same gift allows the Spirit to work miracles through

the God-bearing practitioners of perfect prayer.

SPIRITUAL ELDERS

1447

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Maria Spiridonova endorsed violence for revolutionary goals

and was a leader of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries. B

ROWN

B

ROTHERS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

In fourteenth-century Byzantium the spiritual

elder became central to the hesychast movement

associated with Gregory Palamas (1296–1359). The

hesychasts combined the practice of the so-called

Jesus Prayer (“Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on

me”) with the doctrine of theosis, or deification.

Mount Athos became their chief center, and from

there eldership spread to the Slavic world, produc-

ing Russia’s most famous medieval spiritual elder,

Nil (Maikov, 1433–1508).

After a long period of decline, eldership revived

first in Ukraine and then in Russia through the ef-

forts of several remarkable elders: Paisy (Velichkov-

sky, 1722–1794), translator of the Philokalia, a

basic collection of texts on pure prayer; Serafim

(Mashnin, 1758–1833) of Sarov, Russia’s most im-

portant modern saint; and Amvrosy (Grenkov,

1812–1891), the hermit model for Elder Zosima in

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov. The pop-

ular impact of eldership is recorded in a remarkable

anonymous work, The Pilgrim’s Tale. By 1900, the

contemplative renaissance had reached its peak, al-

though its creative power could still be seen in the

lives of the parish priest John (Sergiev, 1829–1908)

of Kronstadt and Mother Yekaterina (1850–1925)

of Lesna, who worked among the poor.

See also: BYZANTIUM, INFLUENCE OF; MONASTICISM;

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nichols, Robert L. (1985). “The Orthodox Elders (Startsy)

of Imperial Russia.” Modern Greek Studies Yearbook

1:1–30.

Pentkovsky, Aleksei, ed. (1999). The Pilgrim’s Tale. New

York: Paulist Press.

R

OBERT

L. N

ICHOLS

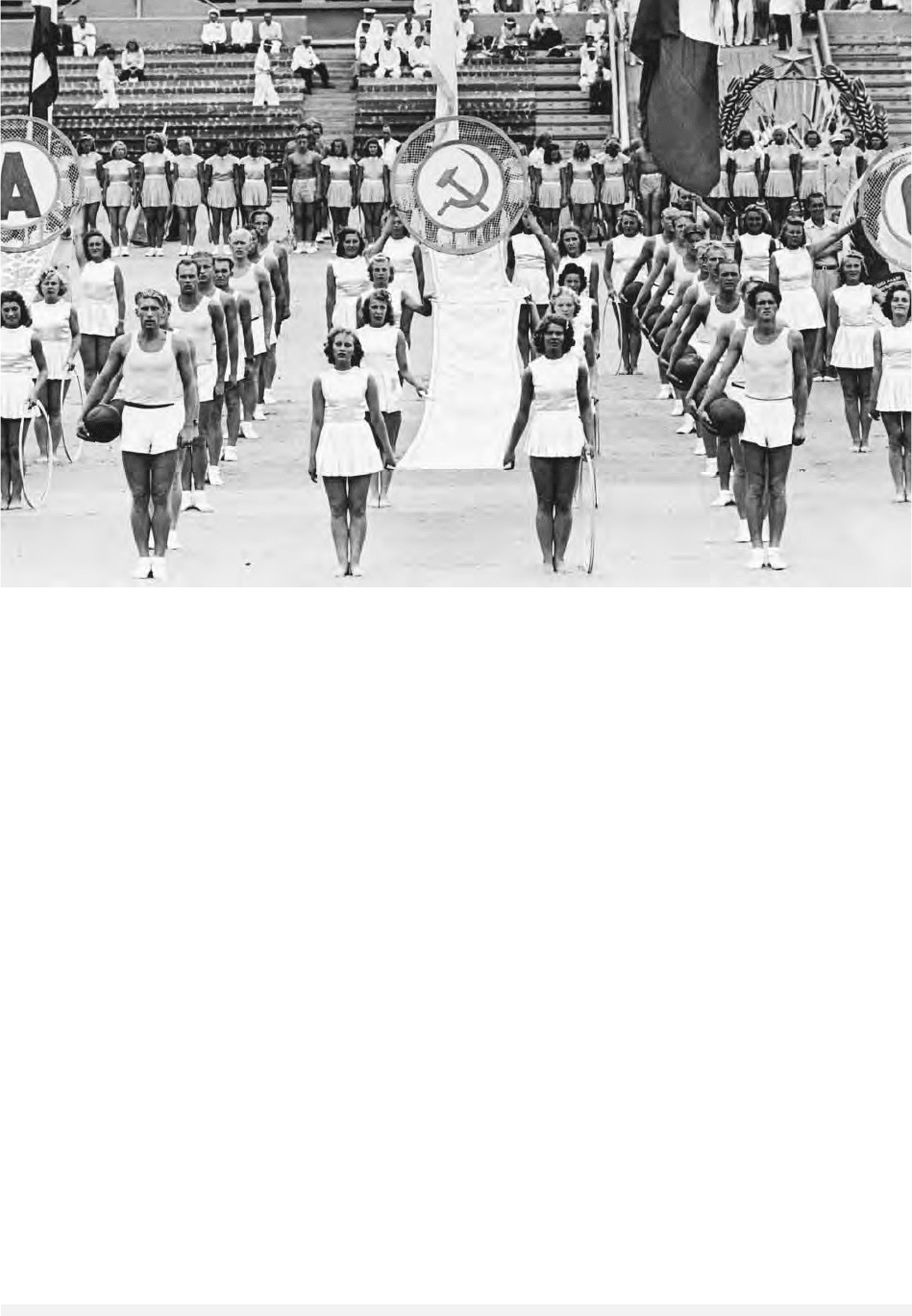

SPORTS POLICY

The Soviet Olympic program, which would pro-

duce more medalists than any other country from

1952 through 1992, got off to a slow start inter-

nationally. Early Soviet contacts with foreign com-

petitors were sparse, as the Soviet Union avoided

international federations in the 1920s and stayed

out of the Olympics, which it regarded as a means

of turning workers’ attention from the class strug-

gle and of preparing them for war. This was par-

alleled domestically by the banning of bourgeois

from sports societies.

In a 1929 resolution, the Communist Party of

the Soviet Union condemned what it called “record

mania.” However, by the 1930s party slogans be-

gan to call for breaking bourgeois sports records.

After World War II, the Soviet Union, perhaps

because it now could compete with the capitalist

countries on an even footing, began an effort to do

so and thereby to demonstrate the virtues of its so-

cial system. Accordingly, beginning in 1946 Soviet

sports associations joined international federations,

including, in 1951, the International Olympic Com-

mittee.

By 1946, weightlifter Grigory Novak became

the first Soviet world champion in any sport, and

in December 1948, the Central Committee explic-

itly stated as a goal the achievement of “world su-

premacy in the major sports in the immediate

future.” At first the Soviet Union participated

mainly in sports in which it had a good chance to

win, but at the 1952 Summer Olympics Soviet ath-

letes competed in all sports except field hockey. The

Soviet Union first participated in the Winter

Olympics in 1956.

The Soviet drive to surpass the capitalist coun-

tries could not always override domestic political

considerations. In the late 1940s, some athletes

who had competed against foreigners before the

war were arrested. Purges, including executions,

occurred in 1950, some as part of the anti-

cosmopolitan campaign carried out by the govern-

ment. Similarly, many officials and athletes had

been victims of the purges of the 1930s.

REASONS FOR SOVIET SUCCESS

One likely reason for the rise of Soviet sports was

the urbanization of the country. As elsewhere,

sport in the Soviet Union was predominantly ur-

ban and remained so even after the Soviet govern-

ment began to push rural sport in 1948. As late as

1972, it was reported that only ten of the 507 So-

viet athletes at the Munich Olympics belonged to

rural sports clubs. This was partly a result of rural

attitudes and partly because of lack of facilities.

Another reason for Soviet successes was the rel-

ative lack of disapproval of women athletes, a phe-

nomenon matched in Soviet society by the presence

of women in heavy labor, both urban and rural.

For example, Soviet domination of bilateral track

and field competitions with the United States—the

Soviets won eleven of thirteen from 1958 to 1975—

was largely due to the superior athleticism of So-

viet women, as they defeated the American women

SPORTS POLICY

1448

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

twelve times while Soviet men won only three

times. Thus it was for practical as well as propa-

ganda reasons that in 1956 and 1960 the Soviet

Union proposed the expansion of the Olympic pro-

gram, especially to include more women. On the

other hand, just as sexism coexisted with celebra-

tion of women’s achievements in Soviet society, for

a long time there was Soviet opposition to female

participation in such allegedly harmful sports as

soccer, judo, and karate.

The Soviets also looked for special opportuni-

ties to excel, as when they made a concerted (and

successful) effort to field an Olympic champion in

team handball when that sport was introduced into

the Olympics.

TRAINING PROGRAMS

Domestically there were a number of programs de-

signed to encourage athletic talent. Perhaps the best

known was GTO (Gotov k Trudu i Oborone—Prepared

for Labor and Defense), which was established in

1931 and granted badges of various kinds to peo-

ple in different age brackets who had achieved cer-

tain government-set athletic goals. As in other areas

of Soviet life, quotas were set for the earning of

badges, and also as in other areas of Soviet life, the

setting of quotas often led to falsification of results,

in this case leading to the granting of unearned

awards.

Stricter, no doubt, were the standards for the

All-Union Sports Classification System established

in 1949 with its five categories. At the top was

Merited (Zasluzhenny) Master of Sport, followed

by Master of Sport, then Classes A, B, and C. Mas-

ters of Sport were expected not only to achieve but

also to serve as political and ideological examples

and to pass on their experience to younger athletes.

On a national scale, elite athletes were show-

cased in the Spartakiads. The first Spartakiad was

held in 1928, to be revived on a regular basis in

1956, then held quadrennially from 1959.

By 1963 the Soviet Union already had fifteen

institutes of physical education and a much larger

number of special secondary schools (tekhnikumy)

as well as departments of physical education at

pedagogical institutes and schools. There were also

scientific research institutes in Moscow, Leningrad,

SPORTS POLICY

1449

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet athletes perform as part of the celebrations for Moscow’s 800th birthday in 1947. © Y

EVGENY

K

HALDEI

/CORBIS

and Tiflis. Despite this, physical education instruc-

tors often complained that their subject was given

insufficient emphasis in schools compared with

academic subjects. Moreover, N. Norman Shneid-

man has described physical education in Soviet

schools as “generally poor,” contrasting this with

the excellent boarding schools, extended day

schools, regular sport schools, clubs, and organi-

zations for the best school-age athletes. The special

schools were introduced in the late 1950s and early

1960s.

Graduate departments of the leading institutes

of higher learning were responsible for developing

methods of training and new equipment and wrote

most of the physical education textbooks and ref-

erence books. In addition, many leaders and coaches

of Soviet national teams had advanced degrees and

authored scholarly publications.

Under Khrushchev, the Soviet Union showed a

renewed willingness to learn from the West after

the extreme xenophobia of the late Stalin years.

Sports was no exception here, as the Soviets invited

the American Olympic weightlifting champion

Tommy Kono to the Soviet Union in order to in-

terview and film him. The Soviets accorded similar

treatment to speed skater Eric Heiden in the late

1970s. In turn, the Soviet Union aided other coun-

tries, furthering propaganda goals in the process,

by providing training, camps, facilities, and equip-

ment to athletes from Africa and Asia, often for

free. Soviet coaches also shared their expertise with

other socialist countries, some of which surpassed

the Soviet Union in certain sports and went on to

send their own coaches to other countries. A no-

table example of this is Bulgaria in weightlifting.

During glasnost there was considerable criti-

cism of the regimentation of child athletes. Special-

ization and rigorous training occurred as early as

age five, and former Olympic weightlifting cham-

pion and future member of Parliament Yuri Vlasov

referred to “inhuman forms of professionalism”

among twelve- and thirteen-year-old gymnasts,

swimmers, and other athletes. Young teenagers of-

ten had to spend considerable time away from their

families and had to choose a specialty at this young

age. However, it should be noted that these phe-

nomena also existed in the United States.

GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIZATION

OF ATHLETES

Soviet government subsidization of elite athletes,

notorious during the era of allegedly pure ama-

teurism, occurred as early as the 1930s. By 1945

the Council of People’s Commissars established a

system that paid cash bonuses for records. In May

1951, in their successful attempt to gain admission

to the International Olympic Committee (IOC), So-

viet delegates to an IOC meeting falsely stated that

bonuses were no longer paid.

Many of the athletes were employed by the

three largest sports organizations, Dinamo (Dy-

namo), run by the security forces; the Soviet Army;

and Spartak, run by the trade unions. As in other

countries, rival sport societies often lured athletes

away from other societies. The best athletes were

freed from military and other duties so that they

could devote full time to their sports. The result

was that Soviet athletes enjoyed a privileged life-

style, at least while they were bringing glory to the

state; after they retired, their standard of living of-

ten declined steeply. Of course it was forbidden for

Soviets, whether journalists, athletes, or anyone

else, to discuss any of this publicly.

Whatever internal politics (e.g., cronyism) may

also have been involved, another phenomenon not

unknown in the United States, selection to inter-

national teams was based primarily on the like-

lihood that the athlete would place highly,

irrespective of recent victories in national champi-

onships. The final selection would be made on the

basis of the athlete’s condition at training camp be-

fore departure for the competition.

Supporting this sporting activity for both prac-

titioners and fans was an extensive Soviet press

dedicated to sport. Sovetsky Sport was the most

prominent among over a dozen Soviet sports news-

papers and periodicals. The publishing house

Fizkultura i sport, founded in 1923, published 40

percent of all Soviet titles on sports. According to

certain unofficial Soviet sources, articles submitted

for publication in scholarly journals were carefully

screened to keep important research findings from

the Soviets’ competitors.

SCARCITY OF RESOURCES

Despite their outstanding success, the Soviets often

lacked resources. As late as 1989 there were only

2,500 swimming pools in the Soviet Union, com-

pared with more than one million in the United

States. There were shortages of gynmasiums and

equipment, and many schools lacked athletic play

areas.

Preference for elites over the masses sometimes

provoked popular resentment alongside national

SPORTS POLICY

1450

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

pride. Even Soviet leaders were sometimes critical

of the neglect of mass physical fitness in favor of

elite athletes, although obviously the latter were

too valuable for propaganda purposes for the sit-

uation to be changed. At the same time, facilities,

equipment, and sports clothing were sometimes

lacking even for elites, leading to relative Soviet

weakness in downhill skiing, for example. More-

over, Soviet athletes often found it necessary to use

foreign equipment in international competition.

Sports historian Robert Edelman has praised the So-

viets for “using limited resources efficiently,” point-

ing out that Soviet Olympic victories were achieved

“on a shoestring.”

POLITICS

In addition to demonstrating their athletic superi-

ority, the Soviets used sports internationally to

make political statements. The Soviet Union was

among the leaders in isolating South Africa from

international sport because of its policy of

apartheid. It also canceled bilateral track and field

meets with the United States from 1966 through

1968, giving the Vietnam War as the reason. The

Soviet boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics,

on the other hand, was almost certainly intended

as retaliation for the American boycott of the 1980

Moscow Olympics, which had protested the Soviet

invasion of Afghanistan.

SPORTS POLICY

1451

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

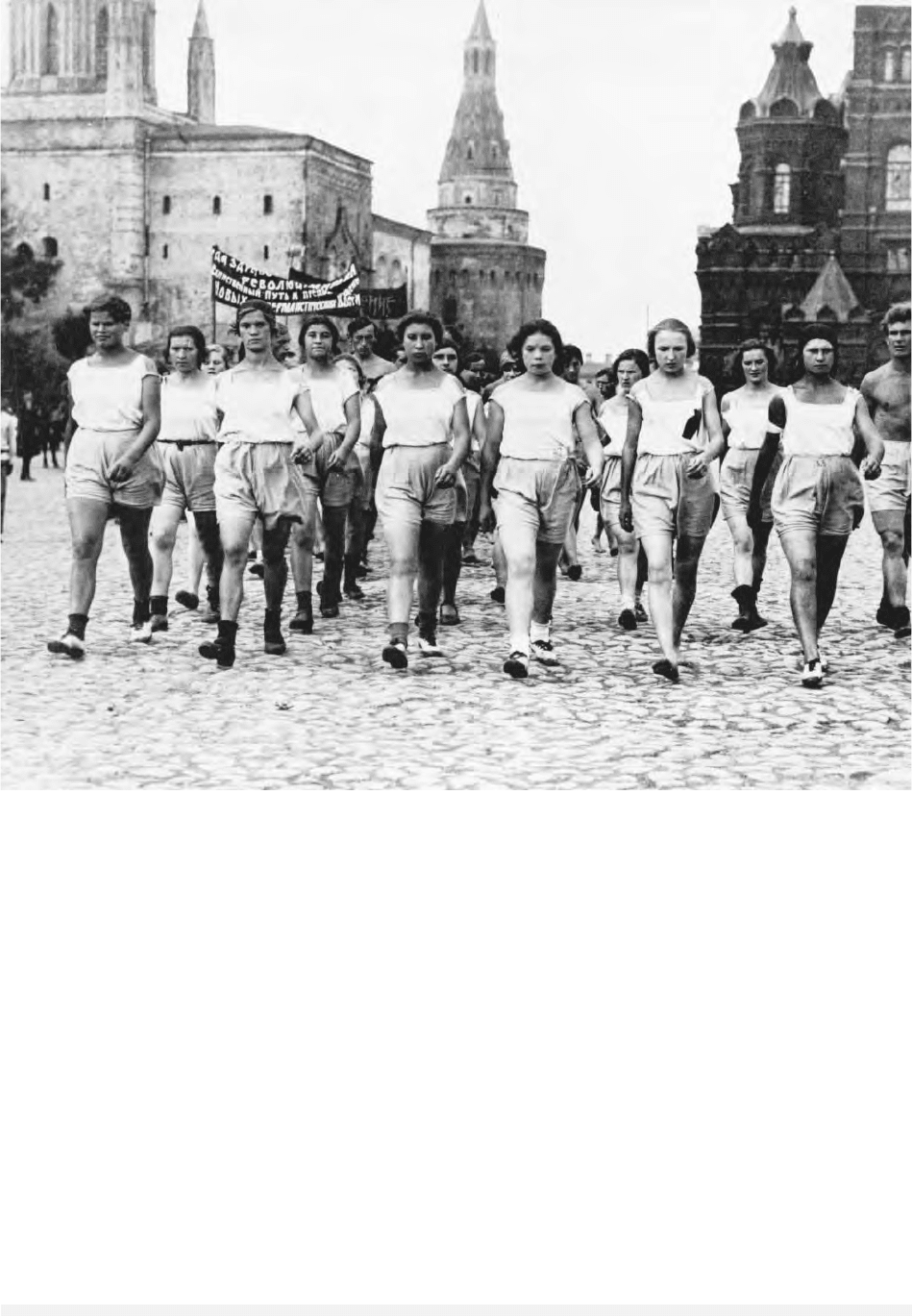

Soviet athletes march through Red Square during the “physical culture” portion of a May Day parade. © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

Even before the American boycott, however,

the Soviet Union had already seen the political im-

plications of hosting the Olympics. For example,

one of the members of the USSR Olympic Orga-

nizing Committee was G. P. Goncharov, the head

of the Communist Party propaganda machine.

Moreover, in the fall of 1979 the government ar-

rested dissidents and warned other people who

complained even mildly about conditions. In Moscow

there was a campaign to remove drunks, the un-

employed, and even teenagers and children from

the city during the Olympics.

CONCLUSION

Soviet sports actually survived the Soviet Union in

a sense, as in the 1992 Olympics athletes from the

former Soviet Union competed together on what

was known as the Unified Team. Although after-

ward the separate independent nations fielded sep-

arate teams, the memory persisted into 1996, as

some Russian newspapers could not resist a brief

mention that, added together, the former Soviet re-

publics combined for the highest number of medals

of any country. Economic problems would persist

for the former Soviet sports programs, sometimes

interfering with athletes’ training, but so would

national pride and excellence, as the Russian Feder-

ation, for example, won 88 medals, second only to

the United States with its larger population, in the

2000 Summer Olympics.

See also: MOSCOW OLYMPICS OF 1980

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Booker, Christopher. (1981). The Games War: A Moscow

Journal. London: Faber and Faber.

Edelman, Robert. (1993). Serious Fun: A History of Spec-

tator Sports in the USSR. New York: Oxford Univer-

sity Press.

Morton, Henry W. (1963). Soviet Sport: Mirror of Soviet

Society. New York: Collier Books.

Peppard, Victor, and Riordan, James. (1993). Playing Pol-

itics: Soviet Sport Diplomacy to 1992. Greenwich, CT:

JAI Press.

Riordan, James. (1977). Sport in Soviet Society: Development

of Sport and Physical Education in Russia and the USSR.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Shneidman, N. Norman. (1978). The Soviet Road to Olym-

pus: Theory and Practice of Soviet Physical Culture and

Sport. Toronto: The Ontario Institute for Studies in

Education.

V

ICTOR

R

OSENBERG

SPUTNIK

On October 4, 1957, Soviet space scientists launched

the first manmade Sputnik, or satellite, to orbit

the earth. Sputnik had great significance on several

counts. It indicated that the USSR was a world

leader in science and engineering. It was a great

propaganda achievement, enabling the nation’s

leaders to claim both scientific preeminence and the

superiority of the Soviet social system. Sputnik also

triggered the space race, as the United States and

the USSR committed to an expansive effort to be

the first in a series of other space firsts. The USSR

followed Sputnik with several other achievements:

the first man in space (Yuri Gargarin); the first

woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova); the first

two-person and three-person orbital flights; the

first space walk; and so on. Sputnik also revealed

that the USSR was or would soon be capable of

launching intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Sputnik was important to the Soviet people as

well. It demonstrated to them that after years of

sacrifice under Stalin the nation was truly on the

road to communism based on the achievements of

science. Tens of thousands of citizens gathered in

the evenings to track Sputnik through the sky, us-

ing binoculars or amateur radios to pick up its sig-

nal. School children sang odes to Sputnik; poets

wrote poems to Sputnik.

Sputnik was only the first Soviet satellite: More

than 2,700 others followed into space. While their

primary purposes were military, they also served

such ends as communication, meteorology, and

global prospecting.

See also: GAGARIN, YURI ALEXEYEVICH; SPACE PROGRAM;

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McDougall, Walter A. (1985). The Heavens and the Earth.

New York: Basic Books.

P

AUL

R. J

OSEPHSON

STAKHANOVITE MOVEMENT

On August 31, 1935, Aleksei Stakhanov, a thirty-

year-old miner in the Donets Basin, hewed 102 tons

of coal during his six-hour shift. This amount rep-

resented fourteen times his quota, and within a few

SPUTNIK

1452

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY