Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Semichastny, were instrumental in the coup that

overthrew Khrushchev in October 1964. The KGB

enjoyed increased prestige and a further expansion

of extralegal powers under the Brezhnev-led collec-

tive leadership that followed. In conjunction with

high Party leaders, the KGB began the well-known

crackdown on internal dissidents in 1965 with the

arrest of the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli

Daniel and the expulsion of Alexander Solzhenitsyn

in 1974. Under the leadership of Yuri Andropov,

who chaired the KGB from 1967 until 1982, it be-

came a stable and critical part of Brezhnev-era ma-

ture socialism.

The reforms of the Gorbachev era, with their

emphasis on openness and legality, threatened the

central tenets of the security police, as did its loss

of control over the Soviet satellite empire. The dis-

solution of the Soviet Union marked the formal end

of the KGB, which was replaced with several suc-

cessor institutions within Russia, the most impor-

tant of which came to be called the Federal Security

Service (FSB). Nevertheless, despite the changed po-

litical circumstances in post-Soviet Russia, the FSB

has maintained a great deal of authority, as is ev-

idenced by the rise of former FSB chief Vladmir

Putin to the presidency. While critics of the secu-

rity police can now complain about its abuses, the

legacy of centuries of powerful state security or-

gans continues in the early twenty-first century.

See also: AUTOCRACY; OPRICHNINA; NICHOLAS I; PURGES,

THE GREAT; RED TERROR; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARI-

ONOVICH; TERRORISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Conquest, Robert. (1985). Inside Stalin’s Secret Police:

NKVD Politics, 1936–1939. Stanford, CA: Hoover In-

stitution Press.

Daly, Jonathan. (1998). Autocracy under Siege: Security

Police and Opposition in Russia, 1866–1905. DeKalb:

Northern Illinois University Press.

Dziak, John J. (1988). Chekisty: A History of the KGB. Lex-

ington, MA: Lexington Books.

Gerson, Lennard D. (1976). The Secret Police in Lenin’s Rus-

sia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Hingley, Ronald. (1970). The Russian Secret Police: Mus-

covite, Imperial, Russian and Soviet Political Security

Operations, 1565–1970. New York: Simon and

Schuster.

Knight, Amy W. (1988). The KGB: Police and Politics in

the Soviet Union. Winchester, MA: Allen & Unwin.

Leggett, George. (1981). The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Po-

lice: The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for

Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, December

1917 to February 1922. New York: Oxford Univer-

sity Press.

Monas, Sidney. (1961). The Third Section: Police and Soci-

ety under Nicholas I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

Ruud, Charles A., and Stepanov, Sergei A. (1999). Fontanka

16: The Tsars’ Secret Police. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s

University Press.

Squire, Peter S. (1968). The Third Department: The Estab-

lishment and Practices of the Political Police in the Rus-

sia of Nicholas I. New York: Cambridge University

Press.

Waller, J. Michael. (1994). Secret Empire: The KGB in Rus-

sia Today. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Zuckerman, Frederic S. (1996). The Tsarist Secret Police in

Russian Society, 1880–1917. New York: NYU Press.

S

TUART

F

INKEL

STATE STATISTICAL COMMITTEE See GOSKOM-

STAT.

STATUTE OF GRAND PRINCE VLADIMIR

Allegedly authored by Grand Prince Vladimir

(r. 980–1015), who is credited with the conversion

of Kievan Rus to Christianity, the Statute estab-

lished the principle of judicial separation between

secular and clerical courts and forbade any of the

Prince’s heirs from interfering in the church’s busi-

ness. The Statute provided that all church person-

nel would be tried in church courts, no matter what

the subject under litigation. The text scrupulously

lists those who qualified for clerical jurisdiction,

identifying not only monastics and members of

church staffs, but also various social outsiders: pil-

grims, manumitted slaves, and the blind and lame,

for instance. In addition, the Statute granted church

courts exclusive jurisdiction over certain offenses,

even if secular subjects of the prince were involved.

Divorce, fornication, adultery, rape, incest, disputes

over inheritance, witchcraft, sorcery, charm-

making, church theft, and intrafamilial violence

were among the subjects assigned to church courts.

Over and above the income generated by church

courts, the Statute assigned the church a tithe from

all the Rus land and a portion of various fees that

the Prince collected. Finally, the text authorized

bishops to supervise the various weights and mea-

sures employed for trade.

STATUTE OF GRAND PRINCE VLADIMIR

1473

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

More than two hundred copies of the Statute

survive, but none is older than the fourteenth cen-

tury, a relatively late date for a document of such

ostensible importance. In addition, the text includes

some obvious errors that have helped undermine

confidence in the legitimacy of the Statute. For in-

stance, in the opening section the Statute reports

that Grand Prince Vladimir accepted Christian bap-

tism from Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople,

who died almost a century before Vladimir con-

verted to Christianity.

The most recent study of the Statute, however,

has concluded that, if not in Vladimir’s own time,

then very soon thereafter, something like the

Statute must already have existed. Archetypes of

different parts of the Statute probably did originate

in the reign of Vladimir, but the archetype of the

entire Statute seems not to have arisen before the

mid-twelfth century. This document, no longer ex-

tant, fathered two new versions in the late twelfth

or early thirteenth century, and each of these, in

turn, contributed to a host of local reworkings, es-

pecially during the fourteenth and fifteenth cen-

turies. As many as seven basic versions of the

Statute survive, each evidently revised to corre-

spond to local circumstances and changing times.

No later than early in the fifteenth century,

however, the Statute had come to enjoy official

standing in the eyes of both churchmen and secu-

lar officials. In 1402 and again in 1419 Moscow

Grand Prince Basil I (1389–1425) confirmed the ju-

dicial and financial guarantees laid out in the

Statute. As a result, most extant copies survive

along with other texts of secular and canon law in

manuscript books like the Kormchaya kniga (the

chief handbook of canon law) and miscellanies of

canon law. Medieval secular codes, such as the

Novgorod Judicial Charter and Pskov Judicial

Charter, confirm that church courts in Rus did ex-

ercise independent authority, just as the Statute of

Vladimir decreed.

See also: KIEVAN RUS; NOVGOROD JUDICIAL CHARTER;

PSKOV JUDICIAL CHARTER; STATUTE OF GRAND PRINCE

YAROSLAV; VLADIMIR, ST.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kaiser, Daniel H. (1980). The Growth of the Law in Me-

dieval Russia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Kaiser, Daniel H., ed., tr. (1992). The Laws of Rus’: Tenth

to Fifteenth Centuries. Salt Lake City, UT: Charles

Schlacks, Jr.

Shchapov, Yaroslav N. (1993). State and Church in Early

Russia, Tenth–Thirteenth Centuries, tr. Vic Shneierson.

New Rochelle, NY: A. D. Caratzas.

D

ANIEL

H. K

AISER

STATUTE OF GRAND PRINCE YAROSLAV

The Statute is reported to have come from the hand

of Grand Prince Yaroslav (r. 1019–1054), son of

Kievan Grand Prince Vladimir, who is credited with

the conversion of Rus to Christianity and also with

the authorship of the Statute of Grand Prince

Vladimir, which instituted church courts in Kievan

Rus. Inasmuch as no copy of Yaroslav’s Statute

from before the fifteenth century survives, many

historians doubted the authenticity of the docu-

ment, but modern textological study has rehabili-

tated the Statute.

Scholars now know of some one hundred

copies of the Statute, which may be divided into

six separate redactions that reflect changes in the

document’s content as it developed in different

parts of the Rus lands in the medieval and early

modern period. The archetype of the Statute evi-

dently did appear in Rus in the reign of Yaroslav,

and gave birth to the two principal versions that

dominated all later modifications in the text. The

archetype of the Expanded version came into being

in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, then

spawned a host of specially adapted copies in the

fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries. The

Short version seems to have arisen early in the

fourteenth century, also stimulating many further

variations in the document’s content and organi-

zation in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. No

later than early in the fifteenth century the Statute

came to enjoy official standing in the eyes of both

churchmen and secular officials. In 1402 and again

in 1419 Moscow Grand Prince Basil I (1389–1425)

confirmed the judicial and financial guarantees laid

out in the Statute. Most extant copies, conse-

quently, survive along with other texts of secular

and canon law in manuscript books such as the

Kormchaya kniga (the chief handbook of canon law).

According to the statute’s first article, Grand

Prince Yaroslav, in consultation with Metropolitan

Hilarion (1051–1054), used Greek Christian prece-

dent and the example of the prince’s father to give

church courts jurisdiction over divorce and to ex-

tend to the church a portion of fees collected by the

STATUTE OF GRAND PRINCE YAROSLAV

1474

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Grand Prince. The various versions of the statute

contained additional provisions, whose specifics de-

pended upon the place and time that the version

was created. Among other subjects, articles consider

rape, illicit sexual intercourse, infanticide, bigamy,

incest, bestiality, spousal desertion and other issues

of family law and sexual behavior. The Statute also

attempted to regulate Christian interaction with

Muslims, Jews, and those who were faithful to in-

digenous religions. Finally, the Statute confirmed

the precedent articulated in the Statute of Grand

Prince Vladimir, according to which both monas-

tic and church people would be subject exclusively

to the authority of church courts. Later versions

sometimes provided for punishment by secular au-

thorities, but in the main version the Statute relied

upon monetary fines to punish wrongdoers.

No records of litigation that employed the

Statute survive from Kievan Rus, but similar

statutes that arose in Novgorod and Smolensk sug-

gest that something like Yaroslav’s Statute existed

in Kiev. In addition, secular codes such as the Nov-

gorod Judicial Charter and Pskov Judicial Charter

confirm that church courts in Rus did exercise ju-

risdiction independent of secular courts.

See also: BASIL I; KIEVAN RUS; STATUTE OF GRAND PRINCE

VLADIMIR; YAROSLAV VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kaiser, Daniel H. (1980). The Growth of the Law in Me-

dieval Russia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Kaiser, Daniel H., ed., tr. (1992). The Laws of Rus’: Tenth

to Fifteenth Centuries. Salt Lake City, UT: Charles

Schlacks, Jr.

Shchapov, Yaroslav N. (1993). State and Church in Early

Russia, Tenth–Thirteenth Centuries, tr. Vic Shneierson.

New Rochelle, NY: A. D. Caratzas.

D

ANIEL

H. K

AISER

STAVKA

Stavka was the headquarters of the Supreme Com-

mander of the Russian armed forces (SVG,

1914–1918), or of the Supreme High Command of

the Soviet armed forces during World War II.

During World War I, the Imperial Russian ver-

sion of Stavka constituted both the highest in-

stance of the tsarist field command and the location

(successively at Baranovichi, Mogilev, and Orel) of

the Supreme Commander. A succession of incum-

bents, including Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich,

Tsar Nicholas II, and Generals Mikhail Alexeyev,

Alexei Brusilov, and Lavr Kornilov, wielded broad

powers over wartime fronts and adjacent areas.

The scale, scope, and impact of modern wartime

operations demonstrated the need for such a com-

mand instance to direct, organize, and coordinate

strategic actions and support among lesser head-

quarters, functional areas, and supporting rear.

However, for reasons ranging from failed leadership

to inadequate infrastructure and poor communica-

tions, the organizational reality never completely

fulfilled conceptual promise. Between 1914 and

March 1918, when Vladimir Lenin abolished a

toothless version of Stavka upon conclusion of the

Brest-Litovsk agreement, the headquarters grew

from five directorates and a chancery to fifteen di-

rectorates, three chanceries, and two committees. In

1917, before occupation by the Bolsheviks in De-

cember, Stavka also served as an important center

of counterrevolutionary activity.

During World War II, a Soviet version of Stavka

again constituted the highest instance of military-

strategic direction, but with a mixed military-civilian

composition. Known successively as the High Com-

mand, Supreme Command, and Supreme High

Command, Stavka functioned under Josef Stalin’s

immediate direction and in coordination with the

Politburo and the State Defense Committee (GKO).

Stavka’s role was to evaluate military-strategic sit-

uations, to adopt strategic and operational deci-

sions, and to organize, coordinate, and support

actions among field, naval, and partisan commands.

The General Staff functioned as Stavka’s planning

and executive agent, while all-powerful Stavka rep-

resentatives, including Georgy Zhukov and Alexan-

der Vasilevsky, frequently served as intermediaries

between Moscow headquarters and major field

command instances.

See also: MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET; WORLD

WAR I; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jones, David R. (1989). “Imperial Russia’s Forces at

War.” In Military Effectiveness, Vol.1: The First

World War, eds. Allan R. Millett and Williamson

Murray. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Shtemenko, S. M. (1973). The Soviet General Staff at War.

2 vols. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

STAVKA

1475

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

STEFAN YAVORSKY, METROPOLITAN

(1658–1722), metropolitan of Ryazan and first

head of the Holy Synod.

Born to a poor noble family in Poland, Yavorsky

and his family moved to Left-Bank Ukraine to live

in a territory controlled by Orthodox Russia. After

studying in the Petr Mohyla Academy in Kiev, Ya-

vorsky temporarily converted to Byzantine-Rite

Catholicism so he could continue his education in

Catholic Poland. In 1687, he returned to Kiev and

the Orthodox Church and became a monk. As a

teacher in the Kiev Academy, Stefan’s eloquence at-

tracted the favorable attention of Peter I, who made

him metropolitan of Ryazan in 1700. After the

death of Patriarch Adrian I in 1700, Peter made Ste-

fan the locum tenens of the Patriarchal throne.

Initially Stefan supported Peter’s reform pro-

gram. But over time, Peter’s treatment of the Or-

thodox Church elicited Stefan’s criticism and

brought a corresponding decline in his influence.

Stefan quietly objected to the secularization of

church property and new restrictions on monasti-

cism. Tensions between Peter and Stefan were only

exacerbated by Stefan’s zealous prosecution of the

Moscow apothecary Dmitry Tveritinov, whose

heresy trial lasted from 1713 to 1718. Influenced

by Lutheran ideas, Tveritinov rejected icons and

sacraments and claimed that the Bible alone pro-

vided sufficient guidance for salvation. The heresy

trial naturally brought up unpleasant questions

about Western Protestant influence in Peter’s re-

forms. Indeed, Stefan’s attack on Lutheranism, The

Rock of Faith, completed in 1718, could not be pub-

lished until 1728, after Peter’s death. To make mat-

ters worse, Stefan’s political reliability came in to

question after Alexei, Peter’s son, fled abroad; in

one of his sermons shortly before Alexei’s flight,

Stefan called him “Russia’s only hope.”

In the meantime, Peter’s new favorite, Feofan

Prokopovich, authored the Spiritual Regulation, a

radical church reform that replaced the office of Pa-

triarch at the head of the Orthodox Church with a

Holy Synod—a council of bishops and priests. In a

vain attempt to halt the rise of his rival, Stefan ac-

cused Feofan of heresy, but was forced to withdraw

the charge and apologize. In 1721 Peter nevertheless

appointed Stefan to become the first presiding mem-

ber of the new Holy Synod. He died a year later.

A transitional figure between the patriarchal and

the synodal periods of the Orthodox Church, Stefan

embodied the contradictions of early eighteenth-

century Russia. One of several learned Ukrainian

prelates who became prominent under Peter, Ste-

fan both promoted Westernization and sought to

limit it. He was deeply influenced by the thought

of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, and helped to

introduce this theology into Russian Orthodoxy

through his writings.

See also: HOLY SYNOD; PETER I; PROKOPOVICH, FEOFAN;

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cracraft, James. (1971). The Church Reform of Peter the

Great. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

J. E

UGENE

C

LAY

STENKA RAZIN

(c. 1630–1671), leader of a Don Cossack revolt and

hero of folksong and legend.

Stepan Timofeyvich Razin, also known as Stenka

Razin, is the hero of innumerable folksongs, legends

and works of art. The most popular motif is his (leg-

endary) sacrifice of his bride, a Persian princess,

whom he throws into the Volga River for the sake

of Cossack solidarity. Over the past three centuries,

the name of Stepan Razin has been associated in the

Russian popular mind with freedom, social justice,

and heroic and adventurous manhood. The philoso-

pher Nikolai A. Berdyaev, assessing the phenome-

non of communism in Russia, characterized it as a

synthesis of Marx and Stenka Razin.

Stepan Razin, the son of a Don Cossack ataman

(military leader) and, it is said, a captive Turkish

woman, rose to prominence among the Cossacks

at a relatively young age. Thus there was no short-

age of volunteers when he led a series of brigandage

expeditions to the lower Volga in 1667 and the

Caspian Sea in 1668 and again in 1669, especially

from among the many impoverished newcomers

to the Don region, mostly former peasants escap-

ing serfdom. Unlike other Cossack leaders, Razin

welcomed the newcomers and cultivated the spirit

of Cossack brotherhood and equality (obsolete by

his time) among his men. His expeditions were un-

usually successful—Russian and Persian caravans

were plundered, Persian commercial settlements

and towns were devastated, a Persian fleet was de-

feated, and Razin’s warriors won riches and glory.

STEFAN YAVORSKY, METROPOLITAN

1476

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Upon returning to Russia, Razin departed from

tradition by keeping his band intact and not shar-

ing his booty with the established Cossack leaders.

Moreover, as he passed through the lower Volga

cities of Astrakhan and Tsaritsyn, hundreds of

townsmen, fugitive peasants, and even regular sol-

diers flocked to his standard. The commanders of

the Russian garrisons did not dare to stop the pop-

ular hero and let him and his men return to the

Don region unimpeded.

Having raised an army of perhaps seven to ten

thousand, Razin announced a new campaign in

1670, aimed at settling scores with the tsar’s bo-

yars and officials, the “traitors and oppressors of

the poor.” The towns of Saratov and Samara

opened their gates to him; Russian peasants and in-

digenous peoples rose up in revolt by the tens of

thousands throughout the lower and middle Volga

region. The rebels intended to march on Moscow,

although they maintained that they were loyal to

the tsar. They were defeated, however, when they

besieged the next large town, Simbirsk, crushed by

the government’s regular army, which exploited

the lack of coordination between Cossacks and

peasants. Stenka Razin fled to the Don region,

where in 1671 he was captured by the men of his

godfather, Kornilo Yakovlev, a leader of the Don

Cossacks. Stenka Razin and his younger brother

Frol were delivered to Moscow in an iron cage and

executed on June 6, 1671.

See also: COSSACKS; FOLKLORE; PEASANTRY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Field, Cecil. (1947). The Great Cossack: The Rebellion of

Stenka Razin against Alexis Michaelovitch, Tsar of All

the Russias. London: H. Jenkins.

Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (1981). Tsar Alexis: His Reign and

His Russia. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic International

Press.

E

LENA

P

AVLOVA

STEPASHIN, SERGEI VADIMOVICH

(b. 1952), general-lieutenant of the internal troops

of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, member of

Supreme Soviet and chair of the Defense and Secu-

rity Committee, head of the Counter-Intelligence

Service, minister of Internal Affairs, prime minis-

ter, and head of State Audit Commission.

Sergei Stepashin joined the Ministry of Inter-

nal Affairs of the Soviet Union and served there

until 1990. He graduated from the Military Acad-

emy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In his last

years in the Ministry of Internal Affairs he was in-

volved in the Ministry’s response to such “hot

spots” as Baku, the Fergana Valley, Nagorno-

Karabakh, and Sukhumi. In 1990 he was elected

to the RSFSR Supreme Soviet from Leningrad, and

he served as chairman of the Committee on De-

fense and Security. He served in the Russian par-

liament until 1993. A political ally of President

Boris Yeltsin, Stepashin was also appointed deputy

minister of security in 1991 and held that post un-

til 1993. In 1993 Stepashin supported Yeltsin in

his struggle with the Russian parliament; Yeltsin

appointed him deputy minister, then, in March

1994, minister, of the Counter-Intelligence Service.

Stepashin played a leading role in unsuccessful

covert efforts to overthrow the Dudayev govern-

ment in Chechnya in the fall of 1994. In 1995

Yeltsin officially fired Stepashin for the fiasco in

handling the Chechen raid on Budennovsk in Rus-

sia but continued his involvement in counter-in-

telligence activities. In 1997 Yeltsin appointed him

minister of Justice. In the administrative turnover

of the last years of Yeltsin’s second term, Stepashin

moved up rapidly. He was appointed minister

of Internal Affairs in April 1998 and then prime

Minister in May 1999 to replace Yevgeny Pri-

makov. Stepashin directed the government’s initial

response to the raid of Chechen bands into Dages-

tan, but was replaced as prime minister by Vla-

dimir Putin in September 1999. In 2000 Putin

appointed Stepashin to head the State Auditing

Commission.

See also: CHECHNYA AND CHECHENS; MILITARY, SOVIET

AND POST-SOVIET; PUTIN, VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH;

YABLOKO; YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bohlen, Celestine. (1999). “Yeltsin Dismisses Another

Premier: KGB Veteran Is In.” The New York Times (Au-

gust 10, 1999).

Bohlen, Celestine. (2002). “Sergey Vadimovich Stepashin.”

National Politics. <http://lego70.tripod.com/rus/

stepashin.htm>.

Shevtsova, Lilia. (1999). Yeltsin’s Russia: Myths and Re-

ality. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

STEPASHIN, SERGEI VADIMOVICH

1477

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

STEPENNAIA KNIGA See BOOK OF DEGREES.

STEPPE

To the forest-dwelling, inland-looking Eastern Slavs

(Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarus), the steppes of

Central Russia and Eurasia historically were much

like the oceans and seas to maritime civilizations.

In song and verse, these vast grasslands were the

dikiye polya (wild fields) inhabited by the equiva-

lent of untamed, bloodthirsty pirates. Between 700

B

.

C

.

E

. and 1600

C

.

E

., the steppes were the realm

of marauding horse-riding nomads, scions of the

Völkerwanderungen (peoples’ migrations), such as

the Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, Huns, Avars,

Magyars, Pechenegs, Polovtsy, Mongol-Tatars, and

multi-cultural free-booting Cossacks. Indeed, until

the invention of the steel-tipped, moldboard plow

in the nineteenth century, Eastern Slavic farmers

were unable to cultivate the rich black-earths

(chernozems) of the steppes, and they confined

their settlements mainly to the forest zones.

Steppe climates are sub-humid, semiarid con-

tinental types. Summer lasts from four to six

months. Average July temperatures range from 70

to 73.5 degrees Fahrenheit (21 to 23 degrees Cel-

sius). Winter, by Russian standards, is mild, with

January averaging between -4 and 32 degrees

Fahrenheit (-13 and 0 degrees Celsius). It generally

persists for three to five months. There is a dis-

tinctive lack of soil moisture. Average annual pre-

cipitation is 18 inches (46 centimeters) in the north

and 10 inches (26 centimeters) in the south. Most

of it derives from summer thunderstorms. The

depth of snow cover in winter ranges from 4 inches

(10 centimeters) in the south to 20 inches (50 cen-

timeters) in the north.

Steppe ecology exhibits subtle diversity. Herba-

ceous vegetation abounds. The only natural forests

follow the river valleys and ravines, but shelter-

belts, planted since the 1930s, parallel the roads and

farms to trap snow in winter. Salinized soils

(solonets) occasionally interrupt the predominant

chernozems and chestnut soils. Small mammals

typify the steppe, including marmots, hamsters,

social meadow mice, jerboas, and others.

This zone and the wooded-steppe to the north

yield Russia’s best farmland. Between 1928 and

1940, most of the steppe was converted to state

and collective farms. In the 1950s, long-term fal-

low lands (perelog and zalezh) were plowed in Rus-

sia’s Altay Foreland and in northern Kazakhstan

(the “Virgin Lands”); thus most of the natural

steppe is gone. Common crops are wheat, barley,

sunflowers, and maize.

See also: CLIMATE; GEOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, James S. (1968). Russian Land, Soviet People.

New York: Pegasus.

Jackson, W. A. Douglas. (1956). “The Virgin and Idle

Lands of Western Siberia and Northern Kazakhstan.”

The Geographical Review 46:1–19.

Shaw, Denis J. B. (1999). Russia in the Modern World: A

New Geography. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

V

ICTOR

L. M

OTE

STILIAGI

A Soviet youth subculture that emerged in the late

1940s and extended into the early 1960s.

The term stiliagi first appeared in the Soviet

press in 1949 to provide a negative characteriza-

tion of young men who pursued what they be-

lieved to be Western models of behavior, leisure,

clothing, and dance styles. Stil’ (style) was essen-

tial for them and the very first stiliagi—almost ex-

clusively men—sported elaborate haircuts and

colorful suits and ties. In the early 1950s the stil-

iagi clothing style became more subdued as they

adopted a more “American” look and wore narrow

black pants and thick-soled shoes. The stiliagi, dis-

playing a pronounced American orientation, called

themselves shtatniki (United States-niks). They lis-

tened to American jazz, smoked American ciga-

rettes, and used American slang. In the late 1950s

and early 1960s some stiliagi embraced rock cul-

ture as it began to spread in the West. Nightlife

was important for the stiliagi and they regularly

gathered in public and private spaces to listen to

jazz and dance Western dances.

The stiliagi phenomenon is most strongly as-

sociated with the ideological relaxation and the

growing material well-being in the post-Stalin pe-

riod. The predominant majority of the stiliagi were

students of higher educational institutions in ma-

jor urban centers. They came from families of the

Soviet professional, political, and managerial elite,

also known as the nomenklatura. Under Stalin and

later Soviet leaders, the nomenklatura received a

STEPENNAIA KNIGA

1478

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

number of privileges (e.g., access to special stores,

trips abroad, better housing, financial bonuses) in

exchange for political conformity. The stiliagi phe-

nomenon reflected the growing consumerist and

leisure-oriented mentality of the upper crust of So-

viet society.

The stiliagi culture was widely denounced by

the Soviet media. The official Komsomol campaign

targeted their “parasitic” and immoral attitude to-

ward work, lack of political involvement and loy-

alty, and pro-Western spirit. In individual cases,

the stiliagi were forced to change their dress and

hairstyles and were expelled from the Komsomol.

In the mid-1980s, parallel to glasnost and per-

estroika, there was a revival of the stiliagi culture.

The new stiliagi included girls and adopted a dress

code of black suits, white shirts, and narrow ties.

They were fans of the Soviet rock ‘n’ roll bands

“Brigada S” and “Bravo.” This new generation of

stiliagi was part of the growing number of nefor-

maly (non-formal), youth groups that emerged

outside of the official youth culture controlled by

the Komsomol and reflected the growing crisis of

cultural and political identity among Soviet youth.

See also: NOMENKLATURA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edele, Mark. (2002). “Strange Young Men in Stalin’s

Moscow: The Birth and Life of the Stiliagi,

1945–1953.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas

50(1):37–61.

Kassof, Allen. (1965). The Soviet Youth Program: Regimen-

tation and Rebellion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

Pilkington, Hilary. (1994). Russia’s Youth and Its Culture.

A Nation’s Constructors and Constructed. New York:

Routledge.

L

ARISSA

R

UDOVA

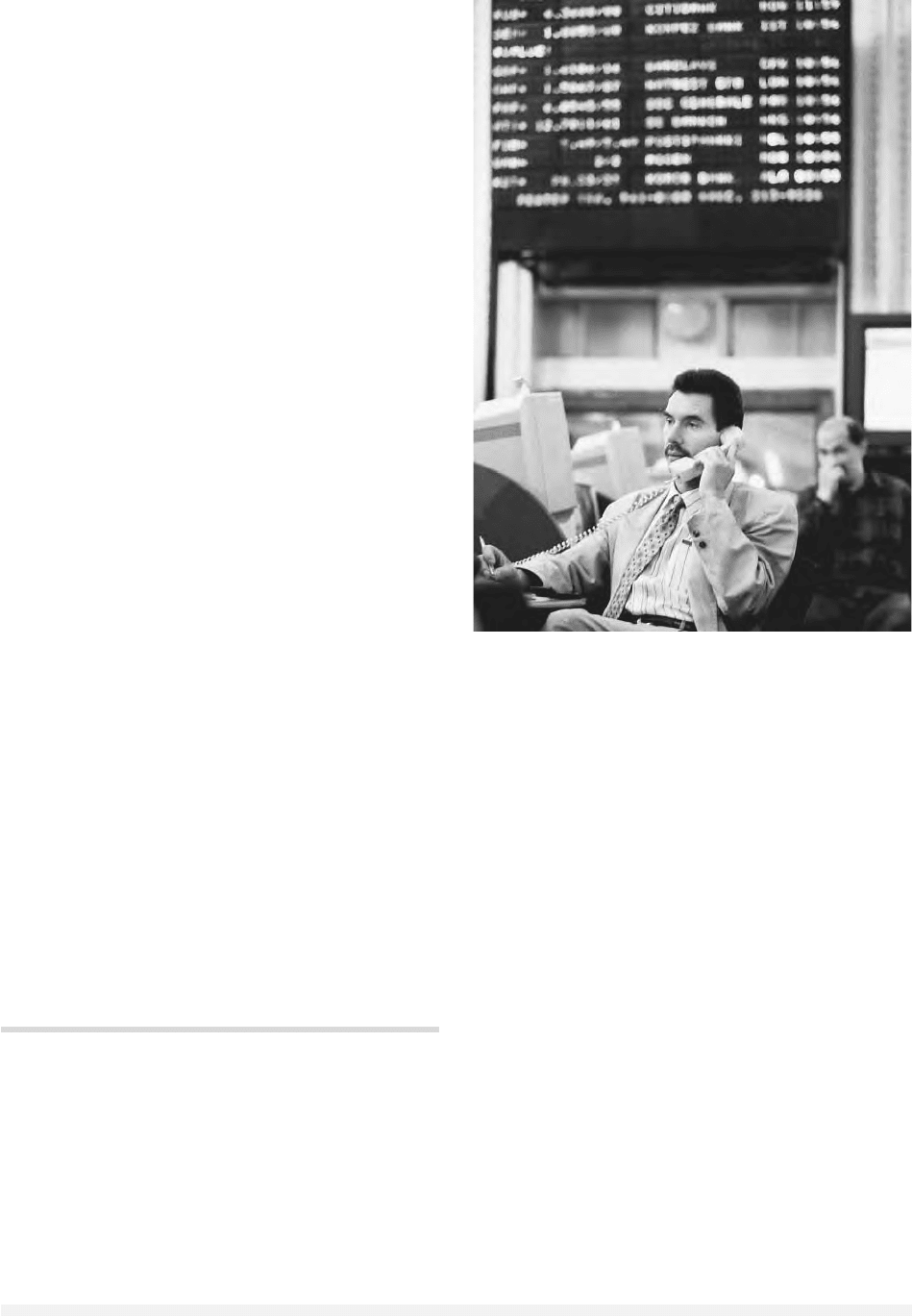

STOCK EXCHANGES

Stock market exchanges are a real or virtual location

for the sale and purchase of private equities. A way

for private enterprises to raise investment funds.

The first stock market exchange in post-Soviet

Russia was primarily trade in privatization vouch-

ers. As privatization proceeded apace, so did the vol-

ume of transactions on Russian exchanges. Shares

in certain Russian enterprises, particularly those of

oil and gas companies, were also increasingly of-

fered on the market, but the stock market or

markets in Russia have yet to offer enterprises sig-

nificant sources of either domestic or foreign in-

vestment funds.

Initially, the Russian stock exchanges were wild

and risky places to venture funds. The early days

witnessed two major boom and bust cycles:

1994–96 and 1996–98. Following the financial cri-

sis of 1989, the Russian stock market almost ceased

to exist. The Russian government sought to regu-

late the market step by step. Prior to 1996 enter-

prises were not required by law to maintain

independent, public registries of stock outstanding,

and both domestic and foreign investors learned to

their dismay that they could be defrauded of their

equity claims. The 1996 Russian Federal Securities

Act required public registries and created the Fed-

eral Securities Commission and charged it with co-

ordinating the various federal agencies that were

STOCK EXCHANGES

1479

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Trade at the Moscow Stock Exchange, August 29, 1998.

© R.P.G./CORBIS SYGMA

responsible for governing the securities market.

Conditions have improved for investors, but much

remains to be done to create a reasonable market

in equities comparable with those in more advanced

capitalist countries. It remains more a site for spec-

ulation than for raising significant amounts of in-

vestment funds.

See also: ECONOMY, POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (2001). Russian

and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure, 7th ed.

New York: Addison Wesley.

Gustavson, Thane. (1999). Capitalism Russian-Style. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

J

AMES

R. M

ILLAR

STOLBOVO, TREATY OF

Signed February 27, 1617 in Stolbovo village, this

treaty terminated Swedish intervention in Russian

affairs after the Time of Troubles. King Gustavus

Adolphus recognized Mikhail Romanov as the le-

gitimate tsar of Russia; withdrew the claim of his

brother Charles Philip to the Russian throne; and

evacuated Novgorod. Russia ceded eastern Karelia

and Ingria to Sweden, foregoing direct access to the

Baltic Sea, and paid an indemnity of twenty thou-

sand rubles.

King Charles IX had initially intervened in 1609

to provide aid against Polish attempts to place a

pretender on the Russian throne. Following the de-

position of Vasily Shuisky in 1610, the boyars’

council agreed to accept Prince Wladyslaw, son of

King Sigismund III, as the next tsar of Russia. Swe-

den declared war and advanced the candidacy of

Charles Philip to the vacant throne. Novgorod was

seized in July 1611.

Sweden found it difficult to control northwest-

ern Russia effectively, and its occupation drained

away military resources needed to protect Swedish

interests in Central Europe. The Stolbovo terms met

Sweden’s primary objective, ensuring that the

Baltic coast—and with it, the primary east-west

trade routes remained in Swedish hands.

Stolbovo marks the high point of Sweden’s

eastward expansion beyond the border first con-

firmed by the 1323 Treaty of Nöteborg. The Swedish

government promoted Lutheran missionary activ-

ity among the Orthodox inhabitants and encour-

aged settlement from other Swedish dominions.

The Stolbovo settlement was reconfirmed by the

1661 Treaty of Kardis, but overturned by the

Treaty of Nystad (1721) that ended the Great

Northern War.

Sir John Merrick, an English merchant, helped

to negotiate the treaty, testifying to Russia’s grow-

ing links with Western Europe. The treaty is also

connected with a famous relic, the Tikhvin Icon of

the Mother of God, a copy of which was brought

to Stolbovo for the negotiations.

See also: NOVGOROD THE GREAT; ROMANOV, MIKHAIL

FYODOROVICH; SHUISKY, VASILY IVANOVICH; SMO-

LENOK WAR; SWEDEN, RELATIONS WITH; TIME OF

TROUBLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Küng, Enn. (2001). “The Swedish Economic Policy in the

Commercial Aspect in Narva in the Second Half of

the 17th Century.” Ph.D. diss. Tartu University, Es-

tonia.

N

IKOLAS

G

VOSDEV

STOLNIK

The highest general sub-Duma rank of military and

court servitors in Muscovy.

Literally meaning “table-attendant,” stolnik first

appears in 1228 and 1230 for episcopal and princely

court officials. As Moscow grew, younger and ju-

nior memoirs of the top families and provincial

serving elites needed a place at court. Accordingly

stolnik lost its earlier meaning and was granted to

many members of these strata. Above it was the

much smaller number of postelniks (chamberlains),

and below a large contingent of striapchis (atten-

dants, servants—a term that appears by 1534), and

Moscow dvorianins. The service land reforms of the

1550s and 1590s assigned Moscow province estates

to these ranks.

From the end of the sixteenth century to 1626,

the numbers of stolniks, striapichis, and Moscow

dvorianins grew respectively from 31–14–174 to

217-82-760, plus another 176 stolniks of Patriarch

Filaret, much of that growth occurring during the

Time of Troubles. After measured growth to 1671,

the numbers of stolniks mushroomed from 443 to

STOLBOVO, TREATY OF

1480

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

1307 in 1682 and 3233 in 1686. By this time an

elite category of chamber stolniks arose, growing

from 18 in 1664 to 173 in 1695. Some stolnik were

always in the tsar’s suite, attending to his needs.

In 1638, the average stolnik land-holding was

seventy-eight peasant households, sufficient to

outfit an elite military servitor and several atten-

dants, as opposed to 24 and 28–29 respectively for

the average striapchiu and Moscow dvorianin, and

520 for the average Duma rank.

The most eminent family names virtually filled

the stolnik rosters in the early seventeenth century.

Among those on the 1610–1611 list were Prince

Dmitry Pozharsky, the military hero of 1612 and

the young “Mikhailo” Romanov, elected tsar in

1613. The percentage of non-aristocratic stolniks

surpassed two-thirds toward the end of the cen-

tury. Under Peter I (the Great) these terms disap-

peared, but former stolniks and their progeny

constituted the critical mass of the upper ranks of

his service-nobility.

See also: BOYAR; DUMA; MUSCOVY; ROMANOV, MIKHAIL

FYODOROVICH; TIME OF TROUBLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1971). Enserfment and Military Change

in Muscovy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

D

AVID

M. G

OLDFRANK

STOLYPIN, PETER ARKADIEVICH

(1862–1911), reformist, chairman of the Council

of Ministers, 1906–1911.

Peter Arkadievich Stolypin, Chairman of the

Council of Ministers from 1906–1911, attempted

the last, and arguably most significant, program

to reform the politics, economy, and culture of the

Russian Empire before the 1917 Revolution. Stolypin

was born into a Russian hereditary noble family

whose pedigree dated to the seventeenth century.

His father was an adjutant to Tsar Alexander II,

and his mother was a niece of Alexander Gor-

chakov, the influential foreign minister of that era.

Spending much of his boyhood and adolescence on

a family estate in the northwestern province of

Kovno, Stolypin came of age in an ethnically and

religiously diverse region where Lithuanian, Polish,

Jewish, German, and other communities rendered

privileged Russians a distinct minority. Stolypin’s

nationalism, a hallmark of his later political career,

cannot be understood apart from this early expe-

rience of imperial Russian life.

As did an increasing number of his noble con-

temporaries, Stolypin attended university, entering

St. Petersburg University in 1881. Unlike many no-

ble sons intent on the civil service and thus the

study of jurisprudence, Stolypin enrolled in the

physics and mathematics faculty, where among the

natural sciences the study of agronomy provided

some grounding for a lifelong interest in agricul-

ture. Married while still a university student to Olga

Borisovna Neidgardt (together the couple would

parent six children), the young Stolypin obtained a

first civil service position in 1883, a rank at the im-

perial court in 1888, but a year later took the un-

usual step of accepting an appointment as a district

marshal of the nobility near his family estate in

Kovno. He spent much of the next fifteen years im-

mersed in provincial public life and politics.

STOLYPIN, PETER ARKADIEVICH

1481

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

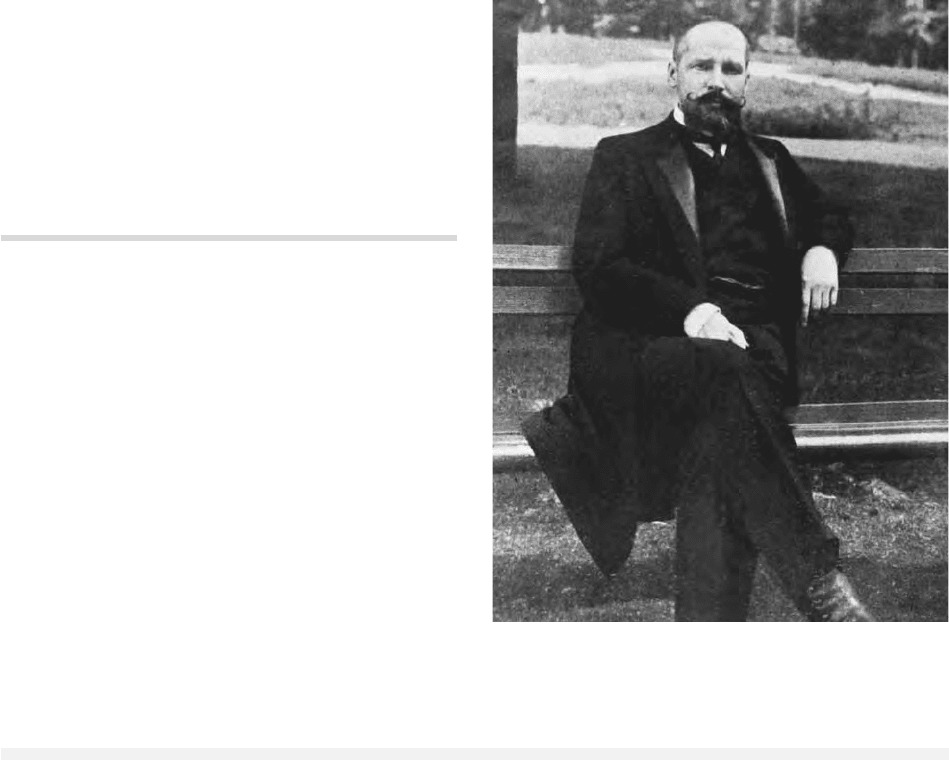

Peter Stolypin introduced key agrarian reforms under Nicholas

II. © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

Scholars generally agree that these years shaped

an understanding of imperial Russia, and the task

of reform that dominated his later political career.

Of primary importance was his experience of rural

life. For much of the 1890s the young district mar-

shal of the nobility also led the life of a provincial

landowning gentleman. Residing on his family es-

tate, Kolnoberzhe, Stolypin took an active interest

in farming, managing income earned from lands

both inherited and purchased. He also experienced

the variety of peasant agriculture, perhaps most

notably the smallholding hereditary tenure in

which peasant families of nearby East Prussia of-

ten held arable land.

Stolypin’s understanding of autocratic politics

also took shape in the provinces. There he first en-

countered its peculiar amalgam of deference, cor-

ruption, bureaucracy, and law. In 1899 an imperial

appointment as provincial marshal of nobility in

Kovno made him its most highly ranked hereditary

nobleman. Within three years, in 1902, the pa-

tronage of Viacheslav von Pleve, the Minister of

Internal Affairs, won him appointment as gover-

nor of neighboring Grodno province. Early 1903

brought a transfer to the governorship of Saratov,

a major agricultural and industrial province astride

the lower reaches of the Volga river valley. An in-

cubator of radical, liberal, and monarchist ideolo-

gies, and the scene of urban and rural discontent in

1904–1905, Saratov honed Stolypin’s political in-

stincts and established his national reputation as an

administrator willing to use force to preserve law

and order. This brought him to the attention of

Nicholas II, and figured in his appointment as Min-

ister of Internal Affairs, on the eve of the opening

of the First State Duma in April 1906. When the

tsar dissolved the assembly that July and ordered

new elections, he also appointed Stolypin to chair

the Council of Ministers, a position that made him

the de facto prime minister of the Russian Empire.

His tenure from 1906 through 1911 was tu-

multuous. Typically, historians have assessed it in

terms of a balance between the conflicting imper-

atives of order and reform. Ironically enough, con-

temporary opponents of Stolypin’s policies, most

notably moderate liberals and social democrats who

pilloried Stolypin for sacrificing the possibilities of

constitutional monarchy and democratic reform to

preserve social order, offered opinions of his poli-

tics that found their way, however circuitously,

into Soviet-era historiography. In this view,

Stolypin favored punitive force, police power, clan-

destine financing of the press, and a general negli-

gence of the law to dominate political opponents

and assert the preeminence of a superficially re-

formed monarchy. Hence, in August 1906, he es-

tablished military field court-martials to suppress

domestic disorder. More drastically, he undertook

the so-called coup d’état of June 3, 1907, dissolv-

ing what was deemed an excessively radical Second

State Duma and, in clear violation of the law, is-

suing a new electoral statute designed to reduce the

representation of peasants, ethnic minorities, and

leftist political parties.

A second view, shared by a minority of his con-

temporaries but a majority of historians, accepted

that Stolypin never entirely could have escaped the

authoritarian impulses widespread in tsarist cul-

ture and especially pronounced among those upon

whom Stolypin’s own influence most depended—

moderate public opinion; the hereditary nobility,

the imperial court; and ultimately the tsar,

Nicholas II. Given such circumstances, without or-

der the far-reaching “renovation” (obnovlenie) of the

economic, cultural, and political institutions of the

Empire envisioned by Stolypin would have been po-

litically impossible. Of central importance to this

interpretation was the Stolypin land reform, first

issued by administrative decree in 1906 and ap-

proved by the State Duma in 1911. This major leg-

islative accomplishment aimed to transform what

was deemed to be an economically unproductive,

politically destabilizing peasant repartitional land

commune (obshchina) and eventually replace it

with family based hereditary smallholdings. Yet,

the reform initiatives of these years were not lim-

ited only to this “wager on the strong,” but ex-

tended into every important arena of national life:

local, rural, and urban government; insurance for

industrial workers; religious toleration; the income

tax; universal primary education; university au-

tonomy; and the conduct of foreign policy.

In September 1911, Stolypin’s career was cut

short when Dmitry Bogrov assassinated him in

Kiev. Once a secret police informant, Bogrov’s back-

ground spawned persistent rumors of right-wing

complicity in the murder of Russia’s last great re-

former, but by all authoritative accounts the as-

sassin acted alone. Some scholars argue that

Stolypin’s political influence, and especially his per-

sonal relationship with Nicholas II, was waning

well before his death, in large measure as a result

of the western zemstvo crisis of March 1911. Yet,

Abraham Ascher, Stolypin’s most authoritative bi-

ographer, credits the claims of Alexander Zenkovsky

that Stoylpin was contemplating further substan-

STOLYPIN, PETER ARKADIEVICH

1482

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY