Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Gershkovich, Alexander. (1989). The Theater of Yuri Lyu-

bimov: Art and Politics at the Taganka Theatre in

Moscow. New York: Paragon House.

M

AIA

K

IPP

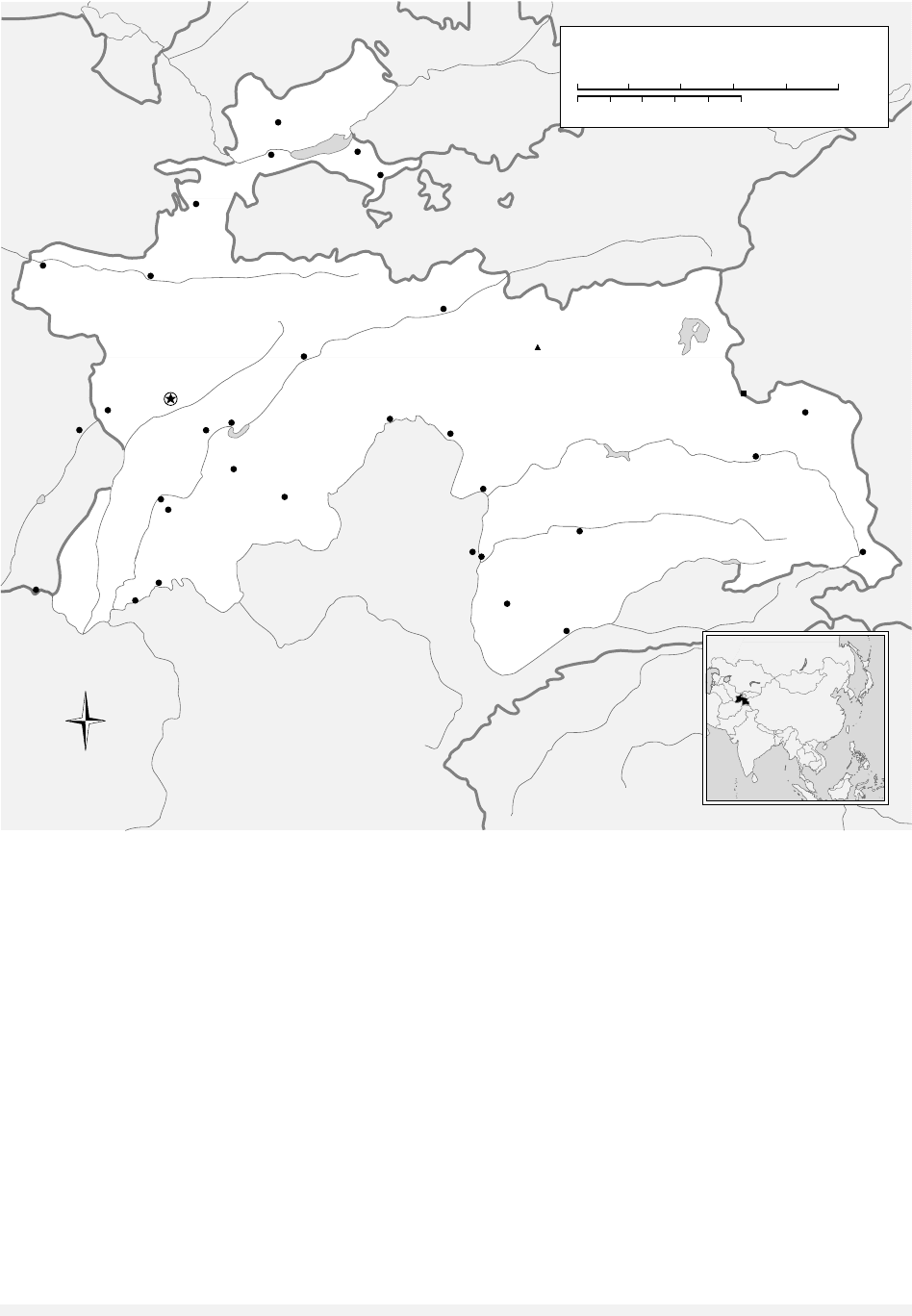

TAJIKISTAN AND TAJIKS

The Tajiks are the most prominent indigenous non-

Turkic population in Central Asia. They are of Per-

sian/Iranian ethnic descent, although their exact

origin is subject to debate. Legends link the Tajiks

with Alexander the Great and his campaign in the

region north of Afghanistan and west of China—

what is today Tajikistan. More likely, contempo-

rary Tajiks are descendants of the Persian-speaking

population that resided in the sedentary regions of

what is now Central Asia, particularly in the coun-

try of Tajikistan.

Tajikistan had a population of 6,719,567 in

2002, of which approximately 4,361,000 were eth-

nic Tajik (64.9%). However, if one adds to that the

million or so Tajiks that live in Uzbekistan and

Afghanistan, respectively, the number increases to

well above six million Tajiks in Central Asia. What

makes these calculations difficult is the fact that

defining oneself as a Tajik is a construct of the So-

viet era. Prior to the early twentieth century, peo-

ple in the region defined themselves more on tribal

and clan affiliations or by their adherence to Islam

than to an ethnic identity. In neighboring Uzbek-

istan, for example, ethnic Tajiks claim that they are

actually more prominent than the official statistics

of that country suggest. Within the Republic of

Tajikistan, other significant minorities include

Uzbeks (25.0%) and Russians (3.5%). Many Rus-

sians emigrated from Tajikistan immediately after

the break-up of the Soviet Union, particularly dur-

ing the period of the civil war (1992–1997). Most

of the Uzbeks live in the northern region of Sogd,

previously known as Leninobod (Leninabad). The

remaining Russians live in the capital city of

Dushanbe, which in 2002 had an overall popula-

tion of 590,000, although that figure undoubtedly

was an underestimation.

The Tajiks speak an eastern dialect of Farsi, the

language of Iran. The languages are mutually in-

telligible; although as modern Tajik is written in

the Cyrillic script and not in the Arabic script, there

can be difficulties between the two. Indeed,

throughout the past century, Tajik has been writ-

ten in Arabic, Latin, and Cyrillic scripts. It is the

intention of the current government to return to

the Arabic script, although the practical difficulties

of such a move have slowed any such effort.

In contrast to the Iranians, the Tajiks are Sunni

Muslims of the Hanafi School, not Shi’a Muslims

like Iranians. This is the result of the history of re-

ligious centers in the region, such as Bukhara and

Samarkand in Uzbekistan, where a number of eth-

nic Tajiks live. More importantly, the Safavid dy-

nasty that made Shi’a Islam the official religion of

Persia did not control the traditional Tajik territo-

ries. There is a small sect of Isma’ili Shi’a in the

Badakhshon area of eastern Tajikistan that is loyal

to the spiritual leader of the Aga Khan. In addition,

the non-Tajiks in the country practice a range of

religions.

Tajiks point to the Sassanid dynasty of the

early tenth century as a founding moment in their

history. Traditionally, the Tajiks—or Tajik speakers—

occupied urban areas of Central Asia, especially the

key trading cities of Samarkand and Bukhara.

TAJIKISTAN AND TAJIKS

1513

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

An elderly Tajik man drinks tea as another plays a traditional

musical instrument at a Dushanbe street market. © AFP/CORBIS

Indeed, many were the economic and political elite

of the Bukharan Emirate, which was prominent in

the sixteenth to the early twentieth centuries. The

Emirate eventually became a Protectorate of the

Russian Empire in the 1870s and until 1917 was

closely associated with the tsarist regime. After the

Bolshevik Revolution and Russian Civil War, which

brought about the Uzbek S.S.R., the Tajik Au-

tonomous S.S.R was established. On October 5,

1929, the Soviet government officially declared it

a full-fledged Union Republic. At 143,000 square

kilometers, Tajikistan is one of the smaller coun-

tries in the region. It is largely mountainous, with

the Pamirs dominating the eastern part of the coun-

try (the region known as the Badakhshon Au-

tonomous Region).

Within a year of independence from the USSR,

the Tajik government collapsed due to infighting

among rival groups and a five-year civil war en-

sued (1992–1997). The war was largely seen as a

struggle between regional rivals. In 1997, the op-

posing sides agreed to form a National Reconcilia-

tion Committee (NRC) that set the stage for a

peaceful resolution to the conflict. President Imo-

mali Rakhmonov successfully consolidated his

authority in the postwar era and in the early

twenty-first century has a firm control of the coun-

TAJIKISTAN AND TAJIKS

1514

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Z

E

R

A

V

S

H

A

N

S

K

I

Y

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

P

A

M

I

R

S

A

L

A

Y

S

K

I

Y

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

(

A

L

A

Y

M

T

S

.

)

Pik Kommunizma .

24,590 ft.

7495 m.

Uzbel

Shankou

S

y

r

d

a

r

'

y

a

Z

e

r

a

v

s

h

a

n

S

u

r

k

h

o

b

D

a

r

'

y

a

K

a

f

i

r

n

i

g

a

n

P

a

n

j

M

u

r

g

a

b

O

k

s

u

P

a

m

i

r

V

a

k

h

s

h

Ozero

Karakul'

A

m

u

G

u

n

t

Dushanbe

Kansay

Kanibadam

Isfara

Ura

Tyube

Pendzhikent

Ayni

Novabad

Dzhirgatal'

Kalai Khumb

Yavan

Tursunzade

Denau

Vanch

Vrang

Qal'eh-ye

Bar Panj

Murgab

Shaymak

Rangkul'

Khorugh

Vir

Roshtkala

Rushan

Dangara

Nurek

Pyandzh

Termez

Kuybyshevskiy

Nizhniy

Pyandzh

Kulob

(Kulyab)

Qurghonteppa

Khudzhand

CHINA

KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN

PAKISTAN

UZBEKISTAN

W

S

N

E

Tajikistan

TAJIKISTAN

125 Miles

0

0

125 Kilometers

5025 10075

50 75 10025

˘

˘

Tajikistan, 1992. © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

try, which continues to be dominated by regional

and clan rivalries.

Tajikistan is an overwhelmingly mountainous

country that has few natural resources other than

mineral wealth. Tajikistan was the source of strate-

gic minerals for the Soviet nuclear program and

continues to be a supplier of other minerals for ex-

port. In particular, aluminum is deemed important

and is the foundation for one of the region’s largest

aluminum processing plants in Tursun-Zade. There

are modest oil and gas deposits, but these are used

exclusively for domestic consumption. Cotton is

also a product traditionally exported.

Because of the civil war, economic development

in the country has been abysmally low. It is esti-

mated that the production levels of the country are

less than half of the 1991 figures. Since 2001, in-

ternational financial institutions have increased

their commitments to Tajikistan to begin the

process of rebuilding the economy. Of particular

interest are the possibilities in hydroelectric energy

and continued development of mineral reserves.

The total gross national product (GNP) for 2001

was $7.5 billion, giving an estimated purchasing

power parity (PPP) at $1,140 per capita. Per capita

income is actually less than $600, with many earn-

ing as little as $10 per month in actual salary.

Because it is a landlocked country that requires

open access to outside trade routes, Tajikistan is de-

pendent upon building strong relations with its

neighbors—China, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and

the Kyrgyz Republic. Of particular importance is

the fact that Tajiks are prominent in neighboring

Uzbekistan, especially in the historic cities of

Bukhara and Samarkand. Another key issue for

Tajikistan is the fact that Iran feels some affinity

toward the country. Iran played a key role in fa-

cilitating the peace talks in the mid-1990s and, at

least at that time, felt it could be a more signifi-

cant player in the country.

Finally, Tajik support of the U.S.-led campaign

in Afghanistan has paid modest returns. There is

currently a small U.S.-base facility in Dushanbe

and strategic assistance from the United States to

Tajikistan has increased substantially. Tajikistan is

now part of the NATO Partnership for Peace pro-

gram. The Tajik government hopes that these in-

creased external relations will eventually translate

into increased economic assistance. In turn, this aid

will help stabilize a very precarious domestic situ-

ation.

See also: ISLAM; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NA-

TIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abdullaev, Kamoludin and Barnes, Catherine, eds.

(2001). Politics of Compromise: The Tajikistan Peace

Process, Accord No. 10. London: Conciliation Re-

sources.

Akiner, Shirin. (2002). Tajikistan: Disintegration or Rec-

onciliation? London: Royal Institute of International

Affairs.

Allworth, Edward, ed. (1994). Central Asia: 130 Years of

Russia Dominance, A Historical Overview. Durham,

NC: Duke University Press.

Atkin, Muriel. (1989). The Subtlest Battle: Islam in Soviet

Tajikistan. Philadelphia: The Foreign Policy Research

Institute.

Atkin, Muriel. (1997). “Thwarted Democratization in

Tajikistan.” In Conflict, Cleavage, and Change in Cen-

tral Asia and the Caucasus, ed. Karen Dawisha and

Bruce Parrott. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Bennigsen, Alexandre and Wimbush, S. Enders. (1985).

Muslims of the Soviet Empire: A Guide. London: C.

Hurst.

Cummings, Sally, ed. (2002). Power and Change in Cen-

tral Asia. London: Routledge.

Rakowska–Harmstone, Teresa. (1970). Russia and Na-

tionalism in Central Asia: The Case of Tadzhikistan.

Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press.

R

OGER

K

ANGAS

TALE OF AVRAAMY PALITSYN

The Tale of Avraamy Palitsyn is one of the earli-

est, most popular and widely diffused (over 200

manuscript copies are known to exist) narratives

about the Time of Troubles. Although the author

was a monk, he took part in many important

events of the period such as the negotiations with

the Poles in 1610. He used eyewitness accounts and

official documentation to compose the tale some

time around 1617. The first six chapters, which

some scholars attribute to another author, narrate

the onset of the Troubles from the time of Ivan IV

to the reign of Vasily I. Shuisky. The core of the

tale (in chapters seven through fifty-two) is com-

prised of an epic, eyewitness description of the siege

of the Trinity St. Sergius monastery between

1608–1610 by Polish forces. The last chapters are

TALE OF AVRAAMY PALITSYN

1515

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

devoted to the liberation of Moscow, the process of

electing Mikhail Fyodorovich Romanov, and the end

of the conflict with the Poles. The text emphasizes

the important role played by the Trinity monastery

in stopping the Polish advance and organizing re-

sistance. Avraamy also stresses the role he played

in inspiring the liberation movement and assisting

it with his deeds and prayers. The tale exists in sev-

eral versions, but scholars disagree over the extent

to which variations represent authorial interven-

tions. Like other works of the period, the tale dis-

plays both stylistic and structural innovations. It

has long been appreciated by scholars for its range

of linguistic registers, use of direct speech, rhyth-

mic prose, and rhetorical skill.

See also: IVAN IV; ROMANOV, MIKHAIL FYODOROVICH;

SHUISKY, VASILY IVANOVICH; TIME OF TROUBLES;

TRINITY ST. SERGIUS MONASTERY

B

RIAN

B

OECK

TAMBOV UPRISING See ANTONOV UPRISING.

TANNENBERG, BATTLE OF

The Battle of Tannenberg, in August 1914, was the

consequence of Russia’s commitment to an imme-

diate offensive during World War I. On the grand

strategic level, the tsarist empire’s major problem

involved making sure its major continental ally,

France, was not forced out of the war before Rus-

sia could bring its full strength to bear. That in

turn justified taking strategic risks. The principal

question was whether the attack should concen-

trate on Germany or Austria, and the Russian army

seemed to have ample strength to pursue both op-

tions.

Russia’s war plan against Germany involved

sending two armies against the exposed province

of East Prussia, defended by what seemed little more

than a token force. The First Army, under General

Pavel Rennenkampf, advanced west across the

Niemen River; the Second Army, under General

Alexander Samsonov, moved northwest from

Russian Poland. Both initially achieved local suc-

cesses against indecisive opposition. The Russian

commanders, however, failed to coordinate their

movements and to press their advantage. Poor lo-

gistics and intelligence further slowed the advance,

particularly in the Second Army’s sector. That gave

a new German command team of Paul von Hin-

denburg and Erich Ludendorff time to develop plans

already outlined by staff officers on the ground—

to concentrate their entire force against the Second

Army.

After five days of hard fighting, between Au-

gust 26 and August 30, there were 50,000 Russian

casualties, and 90,000 prisoners. Samsonov com-

mitted suicide and the Germans turned on Ren-

nenkampf, driving the First Army back over the

frontier between September 7 and 14, in the Battle

of the Masurian Lakes.

The Russians came closer to victory in East

Prussia than is generally realized. Their failure was

primarily a consequence of attempting a campaign

of maneuver arguably beyond the capacity of any

army under the tactical conditions of 1914. But

while the losses in men and material were replaced,

the blow Tannenberg inflicted on Russian national

morale was never restored throughout the war.

See also: WORLD WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Golovine, N. N. (1934). The Russian Campaign of 1914,

tr. A. G. S. Muntz. Ft. Leavenworth, KS: The Com-

mand and General Staff School Press.

Showalter, Dennis. (1991). Tannenberg: Clash of Empires.

Hamden, CT: Archon.

D

ENNIS

S

HOWALTER

TARKOVSKY, ANDREI ARSENIEVICH

(1932–1986), Russian film director.

Tarkovsky was born in the village of Za-

vrazhye on the Volga river in the Ivanovo province,

northeast of Moscow. His father, Arseny Alexan-

drovich (1907–1989), was a poet, at that time

working as a translator before achieving acclaim in

later years. His mother, Maria Ivanovna (Vish-

nyakova), had studied with Arseny at the Moscow

Institute for Literature but was working as a proof-

reader for First State Publishing House in Moscow.

Soon after the family moved to Moscow in 1935,

Tarkovsky’s parents separated and later divorced.

Tarkovsky remained with his mother and sister,

but his father continued to play an important role

in his intellectual and emotional development.

Tarkovsky started school in Moscow in 1939,

but after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union was

TAMBOV UPRISING

1516

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

evacuated in 1941 to relatives in the town of

Yuryevets, near his birthplace. In 1951 Tarkovsky

entered the Institute for Oriental Studies but soon

abandoned his academic life. In 1953 he joined a

geological expedition to Siberia. On returning, he

enrolled the following year at the All-Union State

Institute of Cinematography, where he studied un-

der the supervision of the renowned Soviet direc-

tor Mikhail Romm. Fellow students included Andrei

Konchalovsky, who also later achieved interna-

tional fame as a director, and Vadim Yusev, who

worked as director of photography on several of

Tarkovsky’s early films.

In 1957 Tarkovsky married classmate Irma

Rausch. In 1960 he graduated from film school

with honors. For his diploma work, he wrote and

directed a fifty-minute feature film called The Steam-

roller and the Violin, which treats several themes—

childhood, innocence and loss, male friendship, and

the redemptive power of art—which later become

central to his work. In 1961 Tarkovsky started

work on a Mosfilm commission, released the fol-

lowing year under the title Ivan’s Childhood. This

film, which explores the relationship between a

young boy and two adult soldiers experiencing the

physical and psychological dislocations of war, im-

mediately won international acclaim. Tarkovsky’s

next film, Andrei Rublev, is considered by many to

be his masterpiece. This long, complex account of

the life of the early fifteenth-century Russian icon

painter took five years to complete (1961–1966)

and, because of its unconventional treatment of na-

tional history, its vivid depiction of medieval cru-

elties, and its central concern with the relationship

between spirituality and artistic creation, encoun-

tered the hostility of the Soviet authorities, who

delayed its release by another three years. During

this period, Tarkovsky left his first wife and, in

1970, married the actress Larisa Pavlovna (Yegork-

ina), who worked in many of his later films.

During the next decade, Tarkovsky directed

three more films in the Soviet Union, each intel-

lectually challenging and stylistically innovative:

Solaris (1972), a profound reflection, in a science-

fiction setting, on human relationships, mortality,

and the nature of existence; Mirror (1975), a kalei-

doscope of autobiographical episodes exploring

themes of childhood, maternal love and marriage,

time, memory, and loss, which provoked official

disapproval for its subjective nature but won wide-

spread critical acclaim; and Stalker (1979), a grim

allegory of the human quest for moral salvation.

Tarkovsky’s next film, Nostalghia (1983) was a

joint Soviet-Italian production. Following its com-

pletion, the director decided to remain in Western

Europe. He finished his final film, Sacrifice (1986),

while already suffering from lung cancer. He died

in Paris at the end of the year. In the late 1980s

Mikhail Gorbachev’s new cultural policy inaugu-

rated a posthumous celebration of Tarkovsky’s

work in the Soviet Union. Since 1991 his reputa-

tion, both in Russia and internationally, as one of

cinema’s great artists has not diminished.

See also: MOTION PICTURES; RUBLEV, ANDREI

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Green, Peter. (1993). Andrei Tarkovsky: The Winding Quest.

Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Johnson, Vida T., and Graham Petrie. (1994). The Films

of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue. Bloomington: In-

diana University Press.

Tarkovsky, Andrey. (1986). Sculpting in Time: Reflections

on the Cinema. London: The Bodley Head.

Turovskaya, Maya. (1989). Tarkovsky: Cinema as Poetry.

London: Faber.

N

ICK

B

ARON

TASHKENT

Tashkent is the capital city of the Republic of

Uzbekistan, a country located in the region of Cen-

tral Asia between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya

rivers. The city itself is located on the Zarafshan

River, just to the west of the Ferghana Valley. The

history of Tashkent goes back more than 2,500

years, to a time when there was evidence of habi-

tation in the region. The name itself means “city

of stone,” perhaps indicative of the stones used in

its construction. It grew to be a significant stop on

the great silk road in the eleventh and twelfth cen-

turies, yet remained in the shadows of the more

important city of Samarkand, which is approxi-

mately 300 kilometers (185 miles) to the south.

The city’s fall to Russian forces in 1865 sig-

naled the beginning of Imperial Russian rule over

the region. It was designated as the capital city of

the Turkestan Governor-Generalship and was the

Russian capital of Central Asia. Indeed, as the city

grew in the late nineteenth and early twentieth cen-

turies, distinct districts were formed, for both in-

digenous peoples and for the European colonizers.

Tashkent was the scene of some of the bitterest

TASHKENT

1517

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

fighting during the Russian Revolutions of 1917

and the subsequent civil war. For much of this pe-

riod, Tashkent was a Red bastion, surrounded by

anti-Bolshevik forces.

The political importance of Tashkent continued

through the Soviet period. While Samarkand was

initially designated as the capital of the Uzbek So-

viet Socialist Republic (UzSSR), in 1929 the honor

was given to Tashkent. During World War II, nu-

merous factories and industries were moved to

Tashkent from areas within Russia and Ukraine

that were threatened by invading German forces.

Consequently, Tashkent became industrialized

from the 1940s onward, giving the city a strong

economic importance to Central Asia and the So-

viet Union as a whole.

In 1966 Tashkent experienced a devastating

earthquake that left significant portions of the city

in ruins. The Soviet government made the city’s re-

construction a national effort, and citizens from all

parts of the country moved to Tashkent to help in

the rebuilding, with a number staying afterward.

As a result, the population of the city quickly ex-

ceeded one million, and by the late 1980s was more

than 2.5 million. As of 2002 the official popula-

tion of the city was 2.6 million residents, although

some estimates are closer to 3.0-3.5 million, or

12–14 percent of Uzbekistan’s total population.

While Samarkand and Bukhara make claims to be

the cultural centers of Uzbekistan, Tashkent re-

mains the political and economic power of the

country. Moreover, it is a major transportation and

trade hub for Central Asia.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; UZBEKISTAN AND UZBEKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allworth, Edward, ed. (1994). Central Asia: 130 Years of

Russia Dominance, A Historical Overview. Durham,

NC: Duke University Press.

Bennigsen, Alexandre, and Wimbush, S. Enders. (1985).

Muslims of the Soviet Empire: A Guide. London: C.

Hurst and Company.

Bulatov, M. (1979). Tashkent. New York: Smithmark

Publishing.

TASHKENT

1518

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Boy selling musical instruments at a Tashkent market. © N

EVADA

W

IER

/CORBIS

MacLeod, Calum, and Mayhew, Bradley. (1999). Uzbek-

istan: The Golden Road to Samarkand. London: Odyssey.

Sahadeo, Jeff. (2000). “Creating a Russian Colonial Com-

munity: City, Nation, Empire in Tashkent,

1865–1923.” Ph.D. diss., University of Illinois at Ur-

bana–Champaign.

R

OGER

K

ANGAS

TASS

TASS, the Telegraph Agency of the USSR, was

founded in July 1925 with the goal of centralizing

control over the distribution of foreign news in the

Soviet Union under the oversight of the Commis-

sariat of Foreign Affairs and the Soviet of Peoples’

Commissars (Sovnarkom). Until the collapse of the

USSR, TASS remained the single most important

supplier of foreign news to the Soviet mass media,

a major producer of domestic news, and a key in-

strument for conveying information and propa-

ganda from the Soviet government to foreign

governments and populations. After 1991 TASS be-

came ITAR-TASS (Information Telegraph Agency of

Russia), the central information distributor for the

Russian Federation.

TASS’s predecessor, the Russian Telegraph

Agency, or ROSTA, was founded by the Bolsheviks

in September 1918 and charged with an array of

functions including provision of news reports to

the Soviet press, instruction of journalists in train-

ing, and supervision of provincial newspapers.

ROSTA staff and financial resources were clearly

not adequate to these huge tasks and, in fact, the

provincial press was run by local initiatives during

the civil war. In the winter of 1921 to 1922 the

newly created Press Section of the Party Central

Committee’s Agitprop Department took over su-

pervision of the provincial press and ROSTA was

restricted to wire service functions.

TASS never had a monopoly on the collection

and distribution of either foreign or domestic news.

Until the late 1920s RATAU, the Ukrainian Repub-

lic’s official wire service, maintained correspondents

abroad and engaged in a series of turf wars with

ROSTA/TASS over distribution of foreign news in

Ukraine. Major newspapers such as Pravda, Izves-

tia, and Trud (the central labor union newspaper)

generally posted several correspondents abroad.

In addition to its public news distribution func-

tions, TASS supplied “Not for Press” information

bulletins to Soviet leaders during the late 1920s and

most likely for most of Soviet history.

See also: JOURNALISM; SOVNARKOM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hopkins, Mark W. (1970). Mass Media in the Soviet Union.

New York: Pegasus Publishing.

Mueller, Julie Kay. (1992). “A New Kind of Newspaper:

The Origins and Development of a Soviet Institution,

1921–1928.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cali-

fornia-Berkeley.

M

ATTHEW

E. L

ENOE

TATARSTAN AND TATARS

Tatarstan is a constituent republic of the Russian

Federation, located at the confluence of the Volga

and Kama rivers, with its capital at Kazan. Origi-

nally formed as the Tatar Autonomous Soviet So-

cialist Republic in 1920, it was renamed the

Republic of Tatarstan in 1990. Tatars, sometimes

referred to as the Volga Tatars or Kazan Tatars,

form the indigenous population of Tatarstan. They

form the second largest nationality in Russia (5.5

million in 1989) and one of the largest in the for-

mer Soviet Union. As of 1989, about one quarter

of Tatars lived in Tatarstan (1.8 million), with large

communities in Bashkortostan (1.1 million) and

other republics and provinces of the Volga-Ural re-

gion and Siberia. Additionally, about one million

Tatars lived in other republics of the former Soviet

Union, primarily in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and

elsewhere in Central Asia. The Tatar language be-

longs to the Kipchak branch of the Turkic language

family and has several dialects. Most Tatars are

Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi legal school, with

smaller numbers of Kriashen, or Christianized

Tatars.

Finno-Ugric tribes, the earliest known inhabi-

tants of Tatarstan, were joined by Turkic-speaking

settlers after the third century

C

.

E

. Most important

were the Volga Bulgars, who arrived in the sev-

enth century and by the 900s had established a

state that soon dominated the entire Middle Volga.

Bulgar economic life combined agriculture, pas-

toralism, and commerce, making the Bulgar state

one of the most important trading partners of

Kievan Rus. The Volga Bulgars officially adopted

Islam in 922 during the visit of Ibn Fadlan, an emis-

TATARSTAN AND TATARS

1519

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

sary of the Caliph. In 1236 their capital at Great

Bulgar was captured and destroyed during the

Mongol invasion, and Bulgars subsequently be-

came a subject people of the Mongol empire and

the Golden Horde.

Russians and Europeans often referred to these

invaders as Tatars, a term that originated with a

Turkic tribe in the Mongol army but by the nine-

teenth and early twentieth century was applied by

Russians to several different Turkic Muslim groups,

including ancestors of today’s Kazan or Volga

Tatars, Crimean Tatars, and Azerbaijans. The im-

plication that these peoples are descended from the

Mongol invaders was long commonplace. While

scholars agree that Mongols and their allied tribes

may have played some part in the formation of to-

day’s Tatar people, most also assert that contem-

porary Tatars owe a much larger debt both

genetically and culturally to the Volga Bulgars,

with an admixture of local Finno-Ugric peoples and

several Turkic tribes that migrated to the region

over ensuing centuries.

In the 1440s, as the Golden Horde disintegrated,

a separate khanate emerged at Kazan, in what some

scholars see as a restoration of Bulgar statehood.

In 1552 the Kazan Khanate was conquered and de-

stroyed by Muscovy, marking the first Russian in-

corporation of large Muslim populations into their

expanding empire. Under Russian rule, intense

Christianization campaigns alternated with periods

of greater toleration. In the late eighteenth century,

Catherine II granted the Tatars the right to trade

with the Muslims of Central Asia and allowed them

to form a spiritual board at Ufa to regulate the reli-

gious affairs of Muslims in European Russia. With

their superior knowledge of Turkic language and

customs, Tatar merchants quickly established a

virtual monopoly over trade between Russia and

Central Asia. This contributed to the formation of

Tatar commercial and industrial classes, urbaniza-

tion, formation of a small industrial working class,

and emergence of a secular national intelligentsia.

These factors made the Tatars, like the Azerbaijans

in the Caucasus, one of the most economically in-

tegrated Muslim groups in the empire.

The nineteenth century saw important intel-

lectual and cultural changes, most importantly the

Jadid movement to reform Islamic education by in-

troducing the secular subjects taught in Russian

schools, and the emergence of Western forms of

culture such as novels, plays, theater, and news-

papers. The development of national identity and

cultural nationalism proceeded as well with the cre-

ation of a standard Tatar literary language. How-

ever, the broader questions of national language

and the parameters of the nation remained contro-

versial. Intellectuals who imagined all or most Tur-

kic-speakers as belonging to a single nation of

Turks quarreled with those who defined a narrower

Tatar nationality, while others emphasized the

larger Islamic community. Nevertheless, as Russia

drifted toward revolution in the early twentieth

century, most members of the educated elite shared

a belief that their community formed the natural

leadership of Russia’s Muslim Turkic population.

Tatars were divided by the same social and po-

litical conflicts as Russians during the revolution-

ary period. The question of national autonomy was

intertwined with these conflicts, with a serious di-

vision emerging in 1917 between supporters of ex-

traterritorial cultural autonomy and those favoring

the autonomy of a large territorial Idel-Ural

(Volga-Ural) state within a Russian federation. Lo-

cal Bolsheviks and Left SRs (Socialist Revolutionar-

ies), both Russian and Tatar, secured Soviet power

TATARSTAN AND TATARS

1520

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

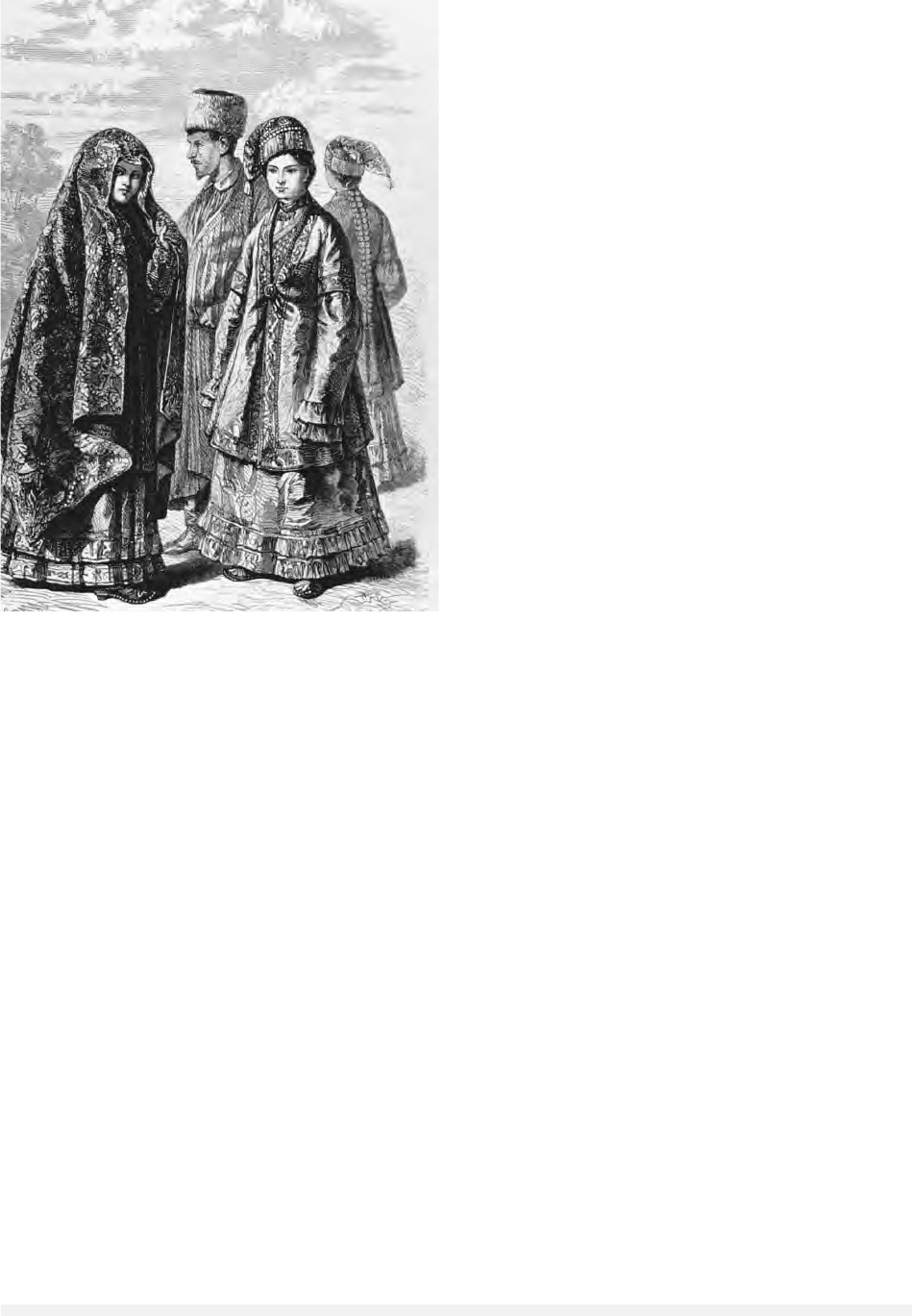

Tatars of Kazan. © J

AMIE

A

BECASIS

/S

UPER

S

TOCK

through Moscow’s proclamation of a Tatar-Bashkir

Soviet Republic in March 1918 and suppression of

anti-Bolshevik Tatar factions. Throughout the civil

war, Tatar leftists such as Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev

supported Soviet power in part because of its pos-

itive attitude toward ethnic federalism, though

many other prominent Tatar leaders, such as the

writer Ayaz Iskhakov, sympathized with the

Whites. Moscow’s decision to create a Bashkir re-

public in 1919 lead to abrogation of the Tatar-

Bashkir republic and promulgation of a separate

Tatar republic in 1920.

Tatarstan experienced all the economic trials of

the Soviet period, including famine in 1921 and

1922 and the collectivization of agriculture, but

also notable industrial development with the emer-

gence of an oil industry since the 1940s, construc-

tion of the immense Kama automobile factory

(KAMAZ) in Naberezhnye Chelny (1970s), and sig-

nificant urban growth. Cultural policies were sim-

ilarly inconsistent: The Tatar language was shifted

from the Arabic alphabet to the Latin in the 1920s

but then Cyrillicized in 1938; and elements of Tatar

history and culture that were celebrated in the

1920s were vilified under Stalin’s rule, only to be

carefully rehabilitated in Tatar journals in the

1960s and 1970s.

During the Gorbachev years, new Tatar polit-

ical organizations raised concerns about the sur-

vival and perpetuation of Tatar national culture,

both within Tatarstan and in the extensive Tatar

diaspora, where assimilation was more common.

The governing circles of Tatarstan responded by de-

claring the republic’s sovereignty and unilaterally

raising its status to union republic (1990), writing

a new authoritative constitution (1992), and sign-

ing a treaty (1994) and other agreements with the

Russian federal government that delineated division

of powers, responsibilities, and resources in a form

widely studied as the Tatarstan model. There was

relatively little interethnic violence in the republic,

in part because Russian residents (43.3% of the

population in 1989, compared to 48.5% Tatar)

benefited from many of these steps as well.

TATARSTAN AND TATARS

1521

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

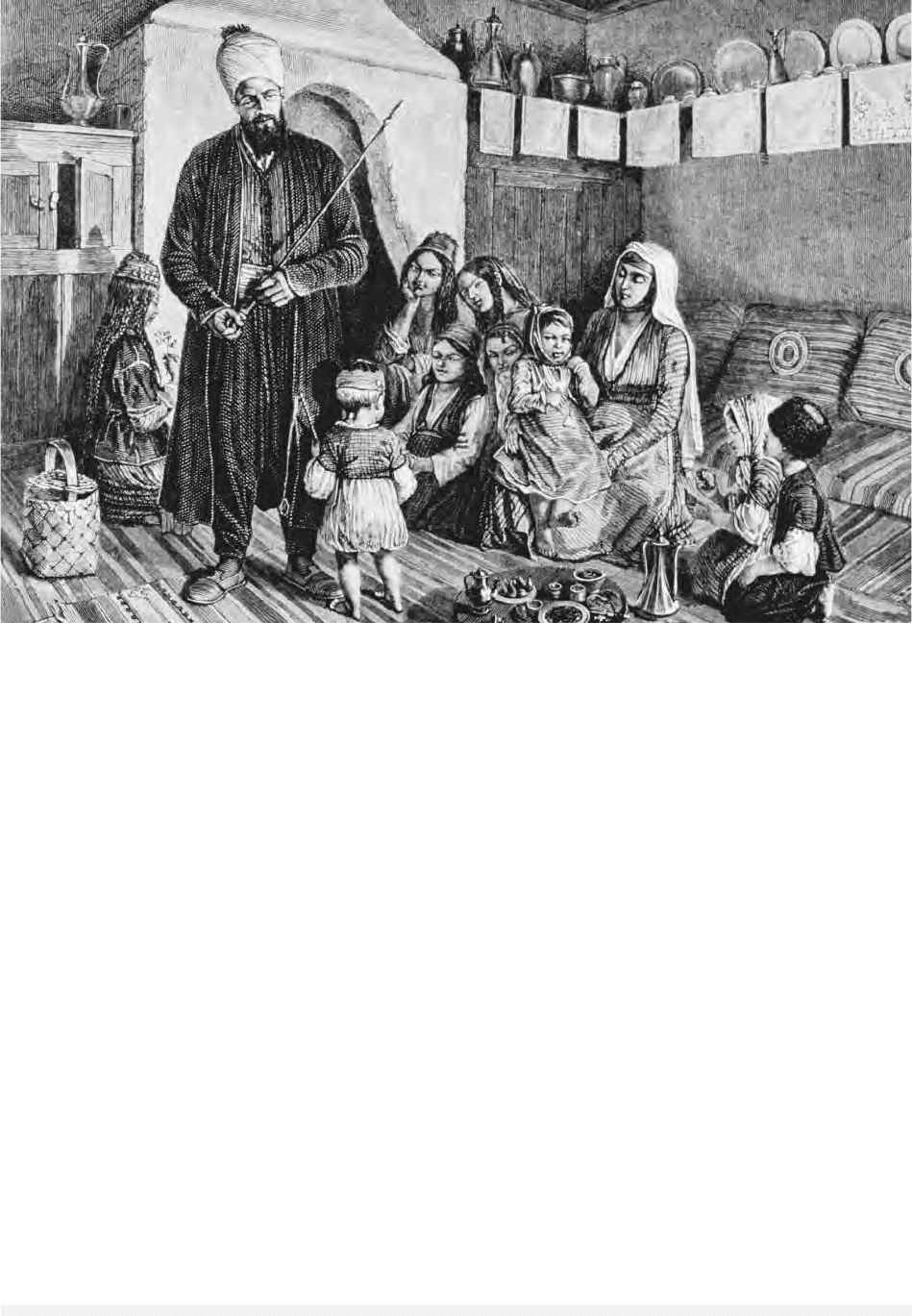

Engraving of a Tatar family in their home. © J

AIME

A

BECASIS

/S

UPER

S

TOCK

One continuing political problem in the 1990s was

concern over the status of Tatars living in neigh-

boring Bashkortostan.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; KAZAN; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bennigsen, Alexandre, and Lemercier-Quelquejay, Chan-

tal. (1967). Islam in the Soviet Union. New York:

Praeger.

Broxup, Marie Bennigsen. (1996). “Tatarstan and the

Tatars.” In The Nationalities Question in the Post-So-

viet States, 2nd ed., ed. Graham Smith. London:

Longman.

Bukharaev, Ravil. (1999). The Model of Tatarstan: Under

President Mintimer Shaimiev. New York: St. Martin’s

Press.

Bukharaev, Ravil. (2000). Islam in Russia: The Four Sea-

sons. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Frank, Allen J. (1998). Islamic Historiography and “Bul-

ghar” Identity Among the Tatars and Bashkirs of Rus-

sia. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Rorlich, Azade-Ayse. (1994). “One or More Tatar Na-

tions?” In Muslim Communities Reemerge: Historical

Perspectives on Nationality, Politics, and Opposition in

the Former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, ed. Edward

Allworth. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rorlich, Azade-Ayse. (1986). The Volga Tatars: A Profile

in National Resilience. Stanford: Hoover Institution

Press.

Zenkovsky, Serge A. (1960). Pan-Turkism and Islam in

Russia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

D

ANIEL

E. S

CHAFER

TAXES

Taxation of the population is the basic way gov-

ernments raise the revenue necessary to carry out

their functions, including administration of justice,

defense, and construction of infrastructure, such as

canals, roads, and public buildings. When taxes are

inadequate, as they often were in Russia, they were

supplemented by domestic and foreign borrowing

(possible after the 1770s), confiscations, or disposal

of state property. The various modes and objects

of taxation also clearly demonstrate the level of eco-

nomic development of Russia through the cen-

turies, as well as the shifting class basis of state

power.

Prior to the establishment of the Russian Em-

pire, most taxation came from the revenues of the

tsar’s estates. As a major serf owner, he collected

rent from them. Following the reduction of the in-

dependent boyar class, the Russian state demanded

service from pomeschiki, nobles and gentry, in ex-

change for their property in land and serfs. The

state also monopolized the export of certain com-

modities, such as grain, farmed out the sale of al-

cohol, and minted silver and copper coins. Where

deficits persisted, the Muscovite princes simply de-

faulted on state obligation. Quantitative estimates

are, however, nearly unavailable until the eigh-

teenth century, when some quantitative studies of

the state budgets were written, most notably those

by Paul N. Milyukov and S. M. Troitsky.

The main taxes in the 1700s were the fixed poll

(soul) tax, excise taxes on alcohol and salt, revenues

from the export monopoly of certain commodities,

tax on iron and copper, customs tariffs, and mint

revenues. During emergencies these were supple-

mented by special taxes (such as on beards of reli-

gious dissenters), debasement of the coinage, or

printing paper money (assignats). The last two,

which caused an inflation tax on holders of cash,

occurred mostly during the frequent wars of those

times. All peasants paid the poll tax according to

population estimates, except during periods of nat-

ural hardship or on the accession of a new ruler,

when rates were temporarily reduced. Throughout

the century the government increased the rate of

indirect taxes on alcohol, as well as demanding cus-

toms duties in hard currency. On the other hand,

burdens on miners and iron-masters appeared to

slacken in the post-Petrine period.

To collect net fiscal revenue the Russian state

employed either tax farmers, agents who paid for

the privilege of collecting levies, or direct distribu-

tion of salt and alcohol. For these monopolized

commodities the tax was simply the difference be-

tween the retail price and the cost of production.

In 1754 the state granted gentry and members of

the aristocracy its former monopoly in the sale of

alcohol, from which incomes increased steadily,

unlike those on salt, a prime necessity. The salt tax

was actually abolished in 1881. Despite these mea-

sures, tax payments were frequently in arrears

(nedoimki), particularly during wars or famine.

Peasants would try to avoid taxes by emigrating

to the frontier areas of Siberia and the southern

steppes, but the system of joint responsibility

meant that fellow villagers would try to prevent

their leaving. Little seemed to change in the tsarist

TAXES

1522

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY