Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

niques to build the metro in the treacherous geol-

ogy of Moscow’s subsoil, which was laced with

underground rivers and quicksand. Builders bored

through layers of Jurassic clay and fissured lime-

stone, soaked with water. Khrushchev recalled that

the builders had only “the vaguest idea of what the

job would entail.” The party mobilized public opin-

ion to gather necessary resources and labor. Days

of voluntary labor became festive occasions as

bands played and able-bodied Muscovites roamed

the shafts looking for work. Prominent officials

picked up shovels and joined Moscow’s masses.

Compared to the construction of the New York

subway system, however, only a handful of Soviet

workers died—and the Soviets trumpeted the suc-

cessful construction as proof of the superiority of

the socialist order. Nonetheless, the Soviets bene-

fited greatly from the long experience of foreign en-

gineers who had helped construct the world’s other

great subway systems. They used the drafts of a

failed 1908 Moscow subway plan, whose backers

were unable to secure financing. Soviet engineers

visited the Berlin subway, studied engineering plans

for the London and Paris subways, and hired Amer-

ican engineers as consultants.

The story of the first Soviet subway was as

much the subject of Soviet propaganda as the ac-

tual metro stations. Soviet memoirs, official histo-

ries, metro architecture, and newspaper accounts

wove the events and personalities of the metro’s

construction into a mythical microcosm of the new

Soviet society. The epic tale of its construction,

which was recounted in two elaborately bound

volumes published in 1935, relayed an ideal con-

ception of socialist engineering and its ability to

conquer and transform nature (human and other-

wise). In this story, successful technological con-

struction did more than fulfill the party plan for

transportation; it proved the inevitable success of

the revolution and the party’s vision of itself as an

instrument of a supposedly scientifically deter-

mined historical destiny.

See also: KAGANOVICH, LAZAR MOYSEYEVICH; KHRUSH-

CHEV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH; SCIENCE AND TECHNOL-

OGY POLICY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bobrick, Benson. (1981). Labyrinths of Iron: A History of

the World’s Subways. New York: Newsweek Books.

Jenks, Andrew. (2000). “A Metro on the Mount: The

Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilization.”

Technology and Culture 41:697-724.

Josephson, Paul. (1995). “‘Projects of the Century’ in So-

viet History: Large-Scale Technologies from Lenin to

Gorbachev.” Technology and Culture 36:519-559.

A

NDREW

J

ENKS

SUCCESSION, LAW ON

Peter I published the Law on Succession, a mani-

festo on the succession to the Russian imperial

throne, on February 16, 1722.

The Law on Succession was the first such writ-

ten law in Russian history. Russia’s rulers in the

fifteenth through seventeenth centuries favored

primogeniture (inheritance by the first-born son),

although this custom could be bypassed for prag-

matic reasons. Peter, prompted by the defection of

his eldest son Alexei (condemned to death for trea-

son in 1718), and by the death of his only surviv-

ing son in 1719, rejected primogeniture and issued

a succession law. The new law required the reign-

ing monarch to nominate his successor with re-

gard to worthiness. It placed no restrictions on age

or gender, but it did not specifically direct the reign-

ing monarch to look beyond the imperial family,

by raising a commoner, for example. The work The

Justice of the Monarch’s Right to Appoint the Heir to

the Throne (1722), attributed to Feofan Prokopovich,

justified the new law with reference to scripture,

history, and natural law. Peter himself died with-

out nominating a successor, but Alexander Men-

shikov claimed to be implementing Peter’s wishes

by choosing his widow Catherine, thereby inau-

gurating a period of female rule. Catherine I, Anna,

Elizabeth, and Catherine II all nominated their own

successors, while Elizabeth and Catherine II took

the throne from legally nominated emperors on the

pretext of protecting the common good. Paul I re-

pealed the law in 1797, replacing it with a new law

based on primogeniture.

See also: PAUL I; PETER I; PROKOPOVICH, FEOFAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lentin, Antony, ed. and tr. (1996). Peter the Great: His

Law on the Imperial Succession: The Official Commen-

tary. Oxford: Headstart History.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

SUCCESSION, LAW ON

1493

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

SUCCESSION OF LEADERSHIP, SOVIET

Like other authoritarian systems, the USSR did not

adopt a formal system of succession. Over time,

the system developed an informal process of suc-

cession, which eventually evolved into a predictable

pattern. In 1922, at the age of 52, Vladimir Lenin,

the first Soviet leader, suffered a major stroke from

which he never fully recovered. After his death in

1924, there was considerable struggle within the

Politburo of the Communist Party before Josef

Stalin emerged as the top leader. Since Lenin had

functioned as chairman of the Council of People’s

Commissars (later called the Council of Ministers),

the emergence of the general secretary as the pre-

eminent leader was not predictable. Lenin’s posi-

tion was equivalent to that of prime minister. The

general secretary initially had been considered an

administrator with little policy responsibility. De-

spite the fact that Stalin led the USSR for almost

thirty years, it was not clear after his death that

the position of general secretary of the CPSU would

remain the preeminent one. Stalin had been prime

minister also since 1941, and it was hard to say

where his power base lay.

After Stalin’s death, Georgy Malenkov chose to

be prime minister when forced to select between the

positions of chairman of the Council of Ministers

or general secretary of the Communist Party. The

less well-known Nikita Khrushchev emerged as the

top leader in the succession struggle that ensued

during the next five years through his role as first

(renamed from general) secretary of the Commu-

nist Party. By 1958 Khrushchev was both prime

minister and first secretary, although not with the

degree of power that Stalin had had before him.

Leonid Brezhnev also used the position of gen-

eral secretary to rise to the top position within the

collective leadership after Khrushchev was deposed.

Although he wanted to be prime minister as well,

the Politburo denied him that title in the interest of

maintaining collective leadership. In 1977 Brezhnev

became president of the USSR (chairman of the Pre-

sidium of the Supreme Soviet), a nominal position

that gave him the position of chief of state in in-

ternational protocol, even though his power base

remained the CPSU.

With the death of Brezhnev (1982), the process

flowed smoothly in the appointment of Yuri An-

dropov as both general secretary and president, and

a short time later both titles passed to Konstantin

Chernenko after Andropov’s death (1984). Within

the Politburo there appeared to be agreement on a

successor and on giving the top leader both a party

and government position.

There was nothing in either the Party Charter

or the Soviet Constitution to guarantee that the

process would remain the same. After the death of

Chernenko in 1985, power passed to a younger

generation. Mikhail Gorbachev became general sec-

retary, after serving as de facto second secretary

under both Andropov and Chernenko. Gorbachev,

however, did not become president. The title went

to an elder statesman, Andrei Gromyko. Only in

1988 did Gorbachev assume the presidency, which

was subsequently restructured as part of pere-

stroika (restructuring) and demokratizatsiya (de-

mocratization). Gorbachev had the real power, not

merely the title, of chief of state and functioned as

president in both domestic and international poli-

tics.

Had the Soviet system continued, it is fair to

say that succession would probably have been in-

stitutionalized in the constitution. Even under Gor-

bachev, however, the Soviet president was not

popularly elected. Gorbachev was selected by the

restructured parliament, the Congress of People’s

Deputies; a new Supreme Soviet, selected from the

Congress, was a working parliament, not merely

a rubber stamp that met once or twice per year.

Even without formal institutionalization, po-

litical succession had become predictable, especially

by the 1980s when the ailing Andropov and Cher-

nenko were successively chosen to lead the USSR.

The selection process was concluded within days of

the leader’s death. The selection of Gorbachev

seemed to be equally smooth, but when one ex-

amines the difficult road that Gorbachev pursued

to undertake reform, one realizes how superficial

consensus was. Gorbachev faced opposition from

the conservatives and liberals within the Politburo

and the CPSU throughout his tenure.

Political succession, although never formalized

in writing, became, nonetheless, a well-established

and even reasonably predictable process in the ma-

ture Soviet Union. The failure to establish a consti-

tutional succession process, even after Gorbachev’s

democratization, was one of many contributing

factors in the rapid demise of the USSR after the

1991 attempted coup.

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION; GEN-

ERAL SECRETARY; POLITBURO; PRIME MINISTER

SUCCESSION OF LEADERSHIP, SOVIET

1494

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bialer, Seweryn. (1980). Stalin’s Successors: Leadership,

Stability, and Change in the Soviet Union. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Breslauer, George W. (1982). Khrushchev and Brezhnev as

Leaders. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Brown, Archie. (1996). The Gorbachev Factor. Oxford: Ox-

ford University Press.

D’Agostino, Anthony. (1988). Soviet Succession Struggles:

Kremlinology and the Russian Question from Lenin to

Gorbachev. Boston: Allen and Unwin.

Hough, Jerry F. (1980). Soviet Leadership in Transition.

Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Hough, Jerry F., and Fainsod, Merle. (1979). How the So-

viet Union Is Governed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

Mitchell, R. Judson. Getting to the Top in the USSR: Cycli-

cal Patterns in the Leadership Succession Process. Stan-

ford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Simmonds, George W., ed. (1967). Soviet Leaders. New

York: Crowell.

N

ORMA

C. N

OONAN

SUDEBNIK OF 1497

The 1497 Sudebnik was Russia’s first national law

code. Unlike earlier immunity charters, which per-

tained only to a private landholder and his land,

and the Dvina Land Charter (1397) and White Lake

Charter (1488), which pertained only to particular

localities, it promulgated rules of general applica-

tion for Muscovite courts. Adopted after Ivan III

had gathered in the lands of Novgorod, Tver, and

other principalities, the Code is usually interpreted

as part of Ivan’s policy of nationbuilding. The short

preamble states that the Code was adopted by

Grand Prince Ivan with his children and boyars.

Thus, unlike some of Muscovy’s other legislation,

it was not associated with an assembly of impor-

tant prelates and servicemen.

A single copy of the Code has come down to

us, which was found and published by Pavel Stroev

in 1817. Most modern editors divide it into sixty-

eight articles, but the original also contains thirty-

seven chapter headings. Articles 1 through 25, in

general, concern courts presided over by boyars and

okolnichy, the two highest service ranks, with some

attention also to the court of the grand prince.

Clerks (dyaki) were to sit with the boyars and okol-

nichy in these courts, and were to prepare not only

a written trial record but also a written judgment.

These courts were to exercise jurisdiction over ma-

jor crimes, such as murder, robbery, and theft, and

the death penalty was provided for certain crimes.

Articles 26 through 36 concern judicial documents

such as summonses, warrants, and default judg-

ments, as well as the duties of judicial officials such

as bailiffs. The bailiffs were charged not only with

serving such judicial documents but also with

interrogating suspected criminals. Articles 37

through 45 concern the courts of the namestniki

and volosteli, the grand prince’s vicegerents in rural

areas. The jurisdiction of these courts depended on

whether the judge was granted full jurisdiction.

Many of the provisions of the first section are re-

peated in the third.

The Code thus either established or confirmed

the previous existence of at least three levels of

courts: that of the grand prince, that of the boyars

and okolnichy, and that of the vicegerents. These

were probably not permanent or standing courts

in the modern sense, because the officials serving

as judges had substantial other administrative and

military duties. All courts used documents at

nearly every stage of judicial proceedings: to initi-

ate the lawsuit, to summon the defendant, to pro-

cure attendance of witness, and to record the

judgment. The first three sections of the code are

largely devoted to the procedural and more specif-

ically the financial side of litigation. No less than

thirty-six articles deal with fees and payments to

be made to the court, and another fifteen concern

damages and payments to private persons. Prohi-

bition of bribery is mentioned several times. Plainly

one of the priorities of the Code was to prevent

bribery and the exaction of excessive fees. There are

also numerous provisions on judicial duels, but ac-

tual court records indicate that such duels were sel-

dom used to resolve litigation. Eyewitnesses and

torture are also prescribed to resolve certain types

of matters. The 1497 Code thus represents the tran-

sition, albeit incomplete, from so-called archaic

law, characterized by composition (bloodwite), no

judicial officials, and irrational modes of proof (trial

by ordeal and combat), to a modern system of

criminal penalties, judges and other judicial offi-

cials, and the use of witnesses and documents as

evidence. The Code was also significant in intro-

ducing or confirming a document-based system of

litigation.

The fourth section, starting at article 46, con-

tains miscellaneous rules of substantive versus

SUDEBNIK OF 1497

1495

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

procedural law, the most famous of which is arti-

cle 57, which requires a peasant to pay his lord a

certain fee in the week before or the week after St.

George’s day if he is to have the right to move

elsewhere. There are also various provisions on

inheritance, manumission of slaves, loans, and

boundaries. The fourth section, however, does not

contain all of the substantive rules of law that

would be necessary to administer justice. For ex-

ample, most of the reported cases of the late fif-

teenth and early sixteenth centuries deal with title

to and ownership of land, but the Code contains vir-

tually no rules or standards for deciding such cases.

Because the Code is primarily a procedural

statute and contains only an incomplete listing of

substantive rules of law, one might ask where the

judges would look to find the substantive rules.

Commentators have suggested that the judges

would look to customary law or to certain Byzan-

tine law manuals. Another possibility is that, in

most cases, judges simply applied their own rough

sense of justice, and that litigation was not gener-

ally conceived as the application of published or

even customary rules.

See also: IVAN III; LAW CODE OF 1649; LEGAL SYSTEMS;

MUSCOVY; OKOLNICHY; SUDEBNIK OF 1550; SUDEBNIK

OF 1589

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dewey, Horace W. (1956). “The 1497 Sudebnik: Mus-

covite Russia’s First National Law Code.” The Amer-

ican Slavic and East European Review 15:325–338.

Dewey, Horace W., ed. (1966). Muscovite Judicial Texts,

1488–1556. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan,

Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literature.

G

EORGE

G. W

EICKHARDT

SUDEBNIK OF 1550

The 1550 Sudebnik was a law code compiled by

Ivan IV (the Terrible) and his boyars. In 1551 it

was submitted for confirmation to the Hundred

Chapters Church Council (Stoglav), on which sat

the highest clerical officials. It proclaims that it is

to govern all criminal and civil litigation. While the

protograph is not extant, forty-three remarkably

consistent copies survive. In all copies the text is

divided into ninety-nine or one hundred articles.

The structure of the text closely follows that

of the 1497 Code: the first section (articles 1–44)

deals with the central courts, held before the grand

prince, his boyars, and his okolnichy; the second (ar-

ticles 45–61) deals with judicial documents and the

duties of bailiffs; the third (articles 62–75) deals

with the provincial and rural courts held before the

tsar’s vicegerents; and the fourth (starting with ar-

ticle 76) contains provisions of substantive law on

such subjects as slavery, disputes over land, inher-

itance, and the sale of chattels and other goods.

Like the 1497 Code, the 1550 Sudebnik is pri-

marily a procedural statute, and a large number of

its provisions deal with the financial side of litiga-

tion: fees, penalties, amounts to be recovered in civil

disputes. The 1550 Code is, however, more than

twice the length of the 1497 Code. Its additional

and different provisions probably reflect what its

draftsmen thought was in need of amendment: that

is, where the previous statute was perceived as not

working or in need of clarification. While the 1497

Code simply prohibits bribery and favoritism, the

1550 Code provides specific penalties for these of-

fenses, including fines and knouting. One new set

of provisions (articles 22–24) deals with bringing

suit in the central courts against vicegerents, which

probably indicates that corruption and misfeasance

by rural officials was perceived as an important

problem. Procedure in the provincial and rural

courts was also regulated in much more detail. One

of the obvious goals of the 1550 amendments was

thus to strengthen the provisions designed to

counter corruption and favoritism. Another provi-

sion prohibits the issuance of new immunity char-

ters, under which landholders, usually monasteries,

had received jurisdiction over all legal cases except

major crimes. The prohibition of further immunity

charters increased the centralization of the admin-

istration of justice and reduced the legal rights of

the monasteries.

Two other new provisions (25–26) provide that

assault without robbery is to be treated as dishonor

(beschestie), an offense that also included defama-

tion. The amount to be recovered by the dishon-

ored party is set forth. Various rational modes of

proof, such as an inquest (obysk) in the commu-

nity, are set forth in greater detail than in the ear-

lier code. Some changes from the 1497 Code are,

however, only as to form and provide additional

detail. For example, articles 8–14 of the 1497 Code,

which deal with prosecuting various crimes, were

expanded and moved, somewhat illogically, to the

second section of the 1550 Code (articles 53–60).

The 1550 Code nevertheless represents a more ad-

vanced and complete transition from archaic law,

SUDEBNIK OF 1550

1496

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

which was characterized by composition, irrational

modes of proof, and the absence of judicial officials,

to a relatively modern system of criminal penal-

ties, rational modes of proof, and the use of judges

to resolve disputes. It nonetheless still contains sev-

eral provisions on judicial duels (although, in fact,

such duels were seldom used).

There were several significant additions to the

provisions on substantive law in the fourth sec-

tion. Six sections on slavery describe in detail how

one becomes a slave, such as by selling oneself to

pay a debt; how a slave can be manumitted; the

documents associated with slavery; and new pro-

visions that create a rule of caveat emptor with re-

spect to purchase of a fugitive slave. Section 85

codified the right to redemption by the seller’s clan

as to land sold by any clan member. Such land

could be redeemed by a clan member within forty

years at the original purchase price. While the pro-

visions of substantive law are set forth in more de-

tail than in the 1497 Code, the 1550 Code still does

not purport to set forth all principles of substan-

tive law. Important rules, such as how to resolve

disputes over the ownership of land, remained sub-

ject to customary rules or to the discretion of the

judge.

In its attempt to deter corruption and its greater

detail as to both procedural and substantive mat-

ters, the 1550 Code demonstrates the progress of

the Muscovite legal systems to a system more pre-

dictable and rational.

See also: CHURCH COUNCIL, HUNDRED CHAPTERS; IVAN

IV; LAW CODE OF 1649; LEGAL SYSTEMS; SUDEBNIK OF

1497; SUDEBNIK OF 1589

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dewey, Horace W. (1962). “The 1550 Sudebnik as an In-

strument of Reform.” Jahrbuecher fuer Geschichte Os-

teuropas 10(2):161–180.

Dewey, Horace W., ed. (1966). Muscovite Judicial Texts,

1488–1556. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan,

Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literature.

G

EORGE

G. W

EICKHARDT

SUDEBNIK OF 1589

The Sudebnik of 1589 was the third in a series of

four Russian legal monuments by that name. They

comprise the core of middle Muscovite jurispru-

dence. The first two Sudebniki were compiled in

1497 and 1550, the last in 1606. This series of le-

gal compilations was crowned by the Ulozhenie of

1649, one of the greatest of all Russian legislative

documents and one of the most impressive in the

entire early modern world.

The codes of 1497, 1550, 1606, and 1649 were

all promulgated by governments in Moscow, but

the Sudebnik of 1589 was compiled anonymously

in the Russian North, the Dvina Land, for unknown

purposes. The 1550 Sudebnik remained the major

operational legal code throughout Muscovy for the

next ninety-nine years—to the extent that there

was one during and after the Time of Troubles. Few

copies of the 1589 document are extant, but it is

known that it was occasionally cited by others—

probably because it contained the 1550 Sudebnik

and its seventy-three supplemental articles, as well

as special laws of interest to the Dvina Land.

The Sudebnik of 1589 has been thoroughly

studied, and it is known which of its 289 articles

originated in which of the sixty-eight articles of the

Sudebnik of 1497 and in which of the one hundred

articles of the Sudebnik of 1550. About 64 percent

of the 1589 code’s articles originated in 1550 (some

of them were expanded), about 9 percent came

from statutes of 1556, and about 27 percent were

new.

By 1589 Russian law had completed the move

from the medieval dyadic legal system to the more

modern triadic system. In the medieval era, state

authority barely existed, and law was as much a

device for raising revenue by officials as it was a

tool for conflict resolution. In the first third of the

sixteenth century, state officials began to play a

much more active, inquisitional role in the judicial

process and tried both to deter and to solve crimes.

Medieval wrongs were treated as torts, but by 1589

they were regarded as crimes. Crimes included

murder, arson, battery, robbery, theft, treason,

bribe-taking, rebellion, recidivism, sacrilege, slan-

der, and perjury. Sanctions included fines, capital

and corporal punishment, mutilation, and incar-

ceration.

Around 1550 the importance of literacy in-

creased dramatically, and Muscovy began its tran-

sition from an oral society to one in which

documents were increasingly important. The evo-

lution was crucial in the laws of evidence, as faith-

based evidence such as oaths, ordeals, and the

casting of lots began to yield to written evidence.

Witnesses, visual confrontations, general investi-

gations, and confessions also grew in importance.

SUKONNAYA SOTNYA

1497

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The law as a revenue instrument for officials re-

mained strong in 1589, and those officials were not

supposed to be corrupt. The 1589 code paid con-

siderable attention to establishing judicial proce-

dures.

There was considerable social legislation in the

1589 Sudebnik. Slaves of various sorts were men-

tioned, as was the fact that the peasants, discussed

frequently, were in the process of being enserfed.

Only perhaps 2 percent of the population were

townsmen, but commerce was important in the

Dvina Land. The collection of interest was permit-

ted, at a maximum of 20 percent per year. Like

most law, the Sudebnik of 1589 was concerned

with cleaning up “social messes” and providing an

infrastructure for the orderly resolution of conflicts

in property and inheritance disputes, especially im-

portant in the Dvina Land where peasants still

owned most of the land. Priority was also given to

the preservation of the social order, particularly

male dominance and other gender distinctions.

See also: LAW CODE OF 1649; LEGAL SYSTEMS; MUSCOVY;

SUDEBNIK OF 1497; SUDEBNIK OF 1550

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1965). “Muscovite Law and Society: The

Ulozhenie of 1649 as a Reflection of the Political and

Social Development of Russia since the Sudebnik of

1589.” Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago.

Hellie, Richard. (1992). “Russian Law From Oleg to Pe-

ter the Great.” Foreword to The Laws of Rus’: Tenth

to Fifteenth Centuries, tr. and ed. Daniel H. Kaiser. Salt

Lake City, UT: Charles Schlacks.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

SUKONNAYA SOTNYA

A privileged corporation of merchants.

Sukonnaya sotnya (Cloth[iers’] Hundred) was a

privileged corporation of merchants who were

ranked third in importance and wealth below the

gosti and members of the Gostinaya sotnya. Sukon-

naya sotnya was formed in the late sixteenth cen-

tury and based on previously extant corporations

of clothiers in Moscow and elsewhere.

The legal status of Sukonnaya sotnya mem-

bers was defined by a charter issued to them at the

turn of the seventeenth century. Members were ex-

empt from direct taxation. They were not subject

to local authorities and received higher compensa-

tion when dishonored. However, Sukonnaya sot-

nya members were not allowed to purchase estates

of patrimonial land or to travel abroad.

Less prosperous than their counterparts in the

other two corporations, Sukonnaya sotnya mem-

bers tended to assist other government merchants

and administer smaller enterprises. However, they

were held responsible for shortfalls in revenue col-

lection.

In the early seventeenth century, there were

250 members of the Sukonnaya sotnya This fig-

ure declined to 130 in 1630 and to 116 by 1649,

despite the appointment of 156 members between

1635 and 1646. In spite of the government’s de-

mands, not all members of the Sukonnaya sotnya

had houses in Moscow.

Sukonnaya sotnya steadily declined in impor-

tance in the second half of the seventeenth century.

By 1678 there were only fifty-one houses belong-

ing to Sukonnaya sotnya members in the capital.

Apparently, the corporation was effectively dis-

banded in the 1680s, and many of its members

joined the Gostinaya sotnya.

By the early eighteenth century, all members

of the Sukonnaya sotnya were registered in guilds,

in 1724 in Moscow and four years later in the rest

of the country.

See also: GOSTI; GOSTINAYA SOTNYA; MERCHANTS

J

ARMO

T. K

OTILAINE

SULTAN-GALIEV, MIRZA

KHAIDARGALIEVICH

(1892–1940), prominent Tatar Bolshevik and Soviet

activist during the Russian Revolution and civil war.

Mirza Khaidargalievich Sultan-Galiev’s rapid

rise to prominence, sudden fall from grace, and sub-

sequent vilification in Stalin’s Russia has provided

several generations with a metaphor for the promise

and frustrations of early Soviet nationality policy.

Born in Ufa province in 1892, Sultan-Galiev had

brief careers as a schoolteacher, librarian, and jour-

nalist, turning to revolutionary activities around

1913. In July 1917 he joined the Bolshevik party

in Kazan, but maintained ties to many intellectuals

and moderate socialists in the Muslim community.

SUKONNAYA SOTNYA

1498

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Sultan-Galiev played a major role in the establish-

ment of Soviet power in Kazan and helped suppress

an anti-Bolshevik Tatar nationalist revolt there in

the first part of 1918. He was an early advocate of

the ill-fated Tatar-Bashkir Soviet Republic, promul-

gated in March 1918 but never implemented, and

of the Tatar Autonomous Republic founded in 1920

(today the Republic of Tatarstan). An able organizer

and public speaker, Sultan-Galiev served the Soviet

state during the civil war as chairman of the Cen-

tral Muslim Military Collegium, chairman of the

Central Bureau of Communist Organizations of

Peoples of the East, and member of the collegium

of the People’s Commissariat of Nationality Affairs.

This last position made him the highest-ranking

member of a Muslim nationality in Soviet Russia.

Sultan-Galiev’s numerous newspaper articles

and speeches outlined a messianic role for Russia’s

Muslim peoples, who would bring socialist revolu-

tion to the subject peoples of Asia and help them

overthrow the chains of European empires. Chief the-

orist of the so-called right wing among the Tatar in-

telligentsia, he hoped to reconcile communism with

nationalism. Although personally an atheist, he ad-

vocated a cautious approach toward anti-religious

propaganda among Russia’s Muslim population.

These views cause some emigré and foreign scholars

to characterize Sultan-Galiev as a prophet of the na-

tional liberation struggle against colonial rule.

By the end of 1922 Sultan-Galiev had come into

direct conflict with Josef Stalin’s nationality policy,

which he openly attacked in party meetings. He was

particularly concerned with two issues, (1) plans for

the new federal government (USSR), which would

disadvantage Tatars and other Muslim groups that

were not granted union republic status, and (2) the

persistence of Russian chauvinism and of a domi-

nant Russian role in governing Muslim republics. In

an effort to silence this criticism, officials acting on

Stalin’s initiative arrested Sultan-Galiev in May

1923 and charged him with conspiring to under-

mine Soviet nationality policy and with illegally con-

tacting Basmachi rebels. Although Sultan-Galiev

was soon released—stripped of his party member-

ship and all positions—a major conference on the

nationality question in June 1923 emphasized that

Stalin’s policies in this area were not to be challenged.

By the end of the 1920s, Sultan-Galievism (sul-

tangalievshchina) had become a common charge

leveled against Tatars and other Muslims and was

later deployed widely during the purges. Sultan-

Galiev was rearrested in 1928 and tried with

seventy-six others as part of a “Sultan-Galievist

counterrevolutionary organization” in 1930. His

death penalty was soon commuted, and he was re-

leased in 1934 and permitted to live in Saratov

province. However, his third arrest in 1937 was

followed by execution in January 1940. The case

of Sultan-Galiev was reviewed by the Central Com-

mittee in 1990, leading to his complete rehabilita-

tion and emergence as a new and old national hero

in post-Soviet Tatarstan.

See also: ISLAM; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; PEOPLE’S

COMMISSARIAT OF NATIONALITIES; TATARSTAN AND

TATARS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bennigsen, Alexandre A., and Wimbush, S. Enders.

(1979). Muslim National Communism in the Soviet

Union: A Revolutionary Strategy for the Colonial World.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

D

ANIEL

E. S

CHAFER

SUMAROKOV, ALEXANDER PETROVICH

(1717–1777), playwright and poet.

Ranked with Racine and Voltaire during his day,

Alexander Petrovich Sumarokov was a founder of

modern Russian literature, and arguably one of

Russia’s first professional writers. Together with

Mikhail Lomonosov and Vasily Tredyakovsky,

Sumarokov helped introduce syllabotonic versifica-

tion, created norms for the new literary language,

and established many literary genres and tastes of

the day. Sumarokov created the first Russian

tragedies, comedies, operas, ballet, and model poetic

genres including the fable, romance, sonnet, and

others. He established the national theater in 1756,

with the help of Fyodor Volkov’s Yaroslav troupe

(it became a court theater in 1759, and lay the foun-

dation for the Imperial Theaters). Sumarokov

published the first private literary journal, Tru-

dolyubivaya pchela (The Industrious Bee, 1759), in-

spiration for the “satirical journals” of the late

1760s and 1770s. An early supporter of Catherine

II, after her ascension to power (or coup) he was

given the right to publish at her expense, of which

he made prolific use. Despite poetic admonitions to

fellow noblemen to treat their serfs humanely,

when Catherine asked his opinion of freeing the

serfs at the time of the Nakaz, Sumarokov was dis-

missive. Gukovsky (1936) and others have tried to

link Sumarokov to a so-called noble “fonde” and to

SUMAROKOV, ALEXANDER PETROVICH

1499

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the “Panin party,” not altogether convincingly.

Sumarokov’s reputation went into total eclipse in

the nineteenth century, when the literary move-

ment he spearheaded was declared merely “pseudo-

Classicism.” It was not until the Soviet period that

his achievement began to be reevaluated.

See also: CATHERINE II; LOMONOSOV, MIKHAIL VASILIEVICH;

THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Levitt, Marcus C. (1995). “Aleksandr Petrovich Sumaro-

kov.” Dictionary of Literary Biography 150: 370–381.

Detroit: Bruccoli Clark Layman and Gale Research.

M

ARCUS

C. L

EVITT

SUPREME SOVIET

The Supreme Soviet was described in the 1936 and

1977 constitutions as the “highest organ of State

power.”

In the USSR, the bicameral Supreme Soviet was

the chief, central legislative organ of the Soviet

state. The constitutions of 1936 and 1977 followed

closely the wording of the two preceding constitu-

tions of 1918 and 1924 in describing the powers

and functions of this body (earlier known as the

Congress of Soviets) and its executive Presidium.

As in preceding years, the deputies to the

Supreme Soviet, elected to four-year terms through-

out the republics, regions, provinces and other po-

litical-administrative subdivisions of authority

throughout the USSR, were said to represent the

interests of the workers, peasants, soldiers, and in-

tellectuals. That the deputies would faithfully serve

those interests, it was claimed in documents ex-

plaining the workings of the central legislature,

was guaranteed by fact that the Communist Party

at all levels played the determining role in selecting

the single-list candidates for election to the legisla-

tive body. By the 1936 and 1977 constitutions,

non-Party deputies could run for election and be

elected. These deputies, too, were carefully vetted

by the Party “aktivs.” Polling places for election of

deputies seldom provided voting booths.

The USSR Supreme Soviet was divided into two

chambers, called the Soviet of the Union and the

Soviet of Nationalities. The former was based on

representation by geographic, political-administra-

tive territorial units nationwide; the latter was

based on national, or ethnic, territorial units. The

rationale given for this in official documents was

that in this way the Soviet people would be repre-

sented both by geographic location as well as by

ethnicity.

Representation was based on one deputy per

every 300,000 of the population. There was no class

restriction as found in the first, 1918, constitution.

The numbers of deputies in each body tended

to increase over the years. This reflected the growth

in population. No officially recognized cap was put

on the total number of deputies, yet a limit never-

theless seemed to be in effect. The Soviet authori-

ties apparently preferred to keep both bodies at

approximately equal and manageable size. In that

sense, the Communist Party leadership exercised

control over the size of the legislative bodies as well

as the texts of the bills submitted to it for enact-

ment—always enacted unanimously by a show of

hands.

From 1937 to the 1960s, the Soviet of the

Union increased from 569 to 791 deputies. The

members of the second, or lower, chamber during

the same period climbed from 574 to 750. The in-

crease in the latter came from the addition of sev-

eral new Union Republics to the USSR. These were

the result of territorial annexations made before

and during World War II.

Both chambers met either separately or in joint

session in the Supreme Soviet building within the

Kremlin. They would meet jointly especially when

the powerful executive Presidium of the Supreme

Soviet was elected (every four years) along with

elections of the USSR Supreme Court and of the

Council of Ministers (formerly, Council of People’s

Commissars), or government and cabinet. The

chairman of the Presidium was considered to be, as

head of state, the Soviet President. By the consti-

tution the chambers were to meet twice per year

in which the closely regulated sessions lasted only

about a week. Prior to the 1950s, the two Soviets

sometimes met more than twice per year.

Besides effecting indirect Communist Party

control over the legislative proceedings, each cham-

ber of the Supreme Soviet established a Council of

Elders. This body, though unmentioned in the con-

stitution, served as a further conduit for Party con-

trol. Each council numbered approximately 150

elders. It consisted of leading figures from the re-

publics, territories, and provinces. Besides proposing

legislation, the councils supervised the formation

of legislative committees, known as commissions,

SUPREME SOVIET

1500

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

within both houses. The committees oversaw af-

fairs concerned with the State budget, legislation,

the courts, foreign affairs, credentials, and so forth.

The work of the committees was closely regu-

lated. Often a leading member of the Communist

Party Central Committee would chair a committee,

such as that concerned with foreign affairs.

Soviet propaganda aimed at a foreign audience

boasted of the heterogeneous, democratic makeup

of the USSR Supreme Soviet. One such document,

Andrei Vyshinsky’s Law of the Soviet State (Gosu-

darstvo i pravo), noted that in the 1930s and 1940s.

the Soviet legislature had a far greater proportion

of women deputies than Western parliaments or

the U.S. Congress. The alleged working-class back-

grounds of the deputies was also touted. Party rep-

resentation in the legislature stood at around 18

percent, or several times that of the percentage

of Party members within the population at large.

Government officials were said to constitute some

15 percent of the deputies.

Soviet juristic writings explicitly denied that the

Soviet Union’s political system recognized the

Western principle of the separation of powers be-

tween the legislative, executive, and judicial organs.

Instead, it was claimed, the Soviet political system

stressed the merging of executive, legislative, and

judicial functions that was further afforded by the

system’s centralized structure. Such unity was fur-

ther enhanced by the parallel Communist Party hi-

erarchy that was likewise structured to emphasize

unity of function at all levels of administration and

political authority.

When the time came for voiced criticism of the

system—beginning to surface within the illegal re-

form movement, or samizdat, of the 1960s, 1970s,

and 1980s—the dissidents, some of whom were put

on trial and served sentences in the labor camps,

called in some instances for retaining the basic

structure of the soviets. Yet they demanded radical

overhaul of the functions of the soviets at all lev-

els of authority as well as elimination of exclusive

Communist Party supervision of soviet elections

and legislative deliberations. Some reformers called

for incorporation of the principle of separation of

powers.

SUPREME SOVIET

1501

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The Yakutsk delegation to the Supreme Soviet in 1938 included secret police chief Nikolai Yezhov, bottom left. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION; CON-

GRESS OF PEOPLE’S DEPUTIES; CONSTITUTION OF 1936;

CONSTITUTION OF 1977; DISSIDENT MOVEMENT; PRE-

SIDIUM OF SUPREME SOVIET; STATE COMMITTEES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Reshetar, John Stephen, Jr. (1978). The Soviet Polity Gov-

ernment and Politics in the USSR, 2nd ed. New York:

Harper & Row.

Towster, Julian. (1948). Political Power in the U.S.S.R.,

1917–1947: The Theory and Structure of Government

in the Soviet State. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Vyshinsky, Andrei Y. (1979). The Law of the Soviet State.

Westport, CT: Greenwood.

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

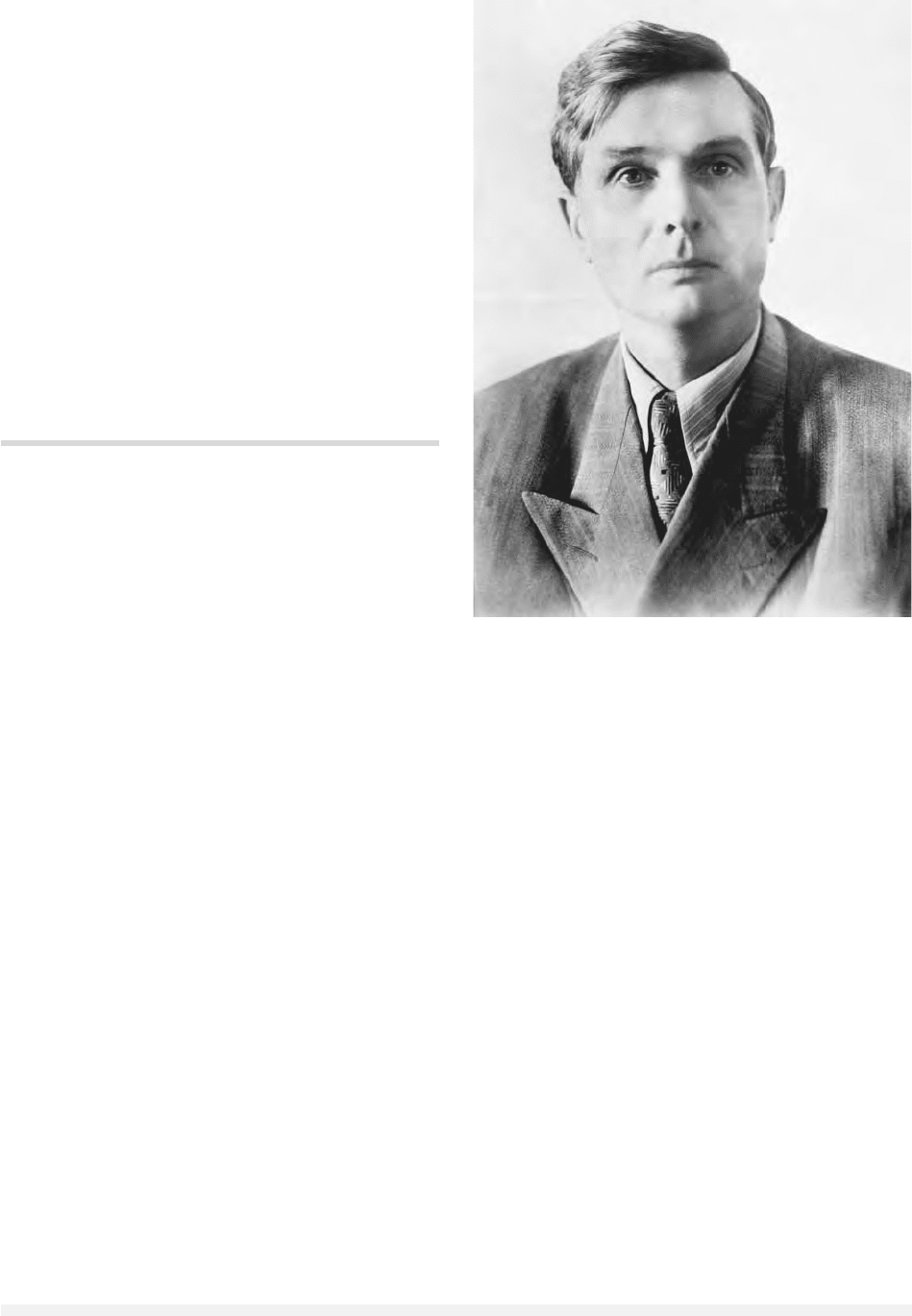

SUSLOV, MIKHAIL ANDREYEVICH

(1902–1982), high-ranking Communist Party leader.

Mikhail Suslov was a member of the Politburo

from 1955 to 1982 and headed the agitation and

propaganda department of the Central Committee

from 1947 to 1982. An ideologist of the Stalinist

school, Suslov was a reactionary and doctrinaire

defender of Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy. Like many

in his generation of party leaders, Suslov had hum-

ble origins. He was born into a peasant family in

1902 in the village of Shakhovskoye, within present-

day Saratov oblast. From 1918 to 1920 he served

as assistant secretary of the Committee of Poor

Peasants (Kombed) and organized a Komsomol

branch in his village. In 1921 he joined the Com-

munist Party and enrolled in a school for workers

in Moscow. He went on to study economics at the

Institute of Red Professors and the Plekhanov Eco-

nomics Institute before entering the party-state ap-

paratus in 1931. Suslov was a ruthless player in

the party purges of the Josef Stalin era and rose

through the ranks by moving into positions opened

up by mass arrests. In 1937 he became a Rostov

oblast party committee secretary. Two years later

he headed the Stavropol regional party committee,

a position he held until 1944. In 1944, as chairman

of the Central Committee’s bureau for Lithuanian

affairs, he supervised the incorporation of Lithua-

nia into the USSR and the subsequent deportation

of thousands of people.

In 1947 Suslov became a secretary of the Cen-

tral Committee in charge of shaping, protecting,

and enforcing official ideology. He also held au-

thoritative positions in foreign affairs and was

noted for his demand for strict adherence to Soviet

foreign policy by foreign communist parties. In

1949, at a Cominform meeting in Budapest, he de-

nounced the Yugoslav Communist Party for its in-

dependent stance and in 1956 went to Hungary

with Anastas Mikoyan and Marshal Grigory

Zhukov to supervise the suppression of the Hun-

garian uprising. Suslov was a shrewd political op-

erator who served three Soviet leaders: Josef Stalin,

Nikita Khrushchev, and Leonid Brezhnev. Very dif-

ferent from Khrushchev in temperament and out-

look, he opposed de-Stalinization and economic

reform, but supported him in 1957 against the an-

tiparty group. In 1964, however, he turned on his

former boss and was instrumental in the removal

of Khrushchev and the installation of Brezhnev as

first secretary of the Communist Party. Eschewing

the limelight, Suslov did not seek the highest party

or state positions for himself, but was content to

remain chief party theoretician and ideologist.

SUSLOV, MIKHAIL ANDREYEVICH

1502

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Mikhail Suslov, shown here in 1956, headed the Communist

Party’s agitation and propaganda department from 1946 until

his death in 1982. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS