Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

tive reforms of the empire’s administrative and ter-

ritorial structures in the last months of his life.

Stolypin’s historical reputation continues to be the

subject of scholarly debate, the character and con-

sequences of his policies intertwined with larger de-

bates about the stability and longevity of the tsarist

regime.

See also: AGRARIAN REFORMS; DUMA; ECONOMY, TSARIST;

NICHOLAS II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ascher, Abraham. (2001). P. A. Stolypin: The Search for

Stability in Late Imperial Russia. Stanford, CA: Stan-

ford University Press.

Conroy, Mary Schaeffer. (1976). Peter Arkad’evich

Stolypin: Practical Politics in Late Imperial Russia.

Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Macey, David A. J. (1987). Government and Peasant in

Russia, 1881–1906: The Prehistory of the Stolypin Re-

forms. De Kalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Von Bock, Maria Petrovna. (1970). Reminiscences of My

Father Peter A. Stolypin, tr. and ed. Margaret Patoski.

Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press.

Waldron, Peter. (1998). Between Two Revolutions: Stolypin

and the Politics of Renewal in Russia. London: UCL.

Wcislo, Francis W. (1990). Reforming Rural Russia. State,

Local Society, and National Politics, 1855–1914.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Zenkovsky, Alexander. (1986). Stolypin: Russia’s Last

Great Reformer, tr. Margaret Patoski. Princeton, NJ:

Kingston Press.

F

RANCIS

W. W

CISLO

ST. PETERSBURG

From 1712 until 1918, St. Petersburg was the cap-

ital of the Russian Empire. Peter I (the Great) be-

gan the construction of the city as his “Window

on the West” in 1703. During the subsequent three

centuries, St. Petersburg was identified with the

three major forces shaping Russian history: West-

ernization, industrialization, and revolution. The

city was renamed Petrograd in 1914, at the begin-

ning of World War I, because it sounded less Ger-

man, was then named Leningrad after the death of

Vladimir Lenin in 1924, and again became St. Pe-

tersburg in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed.

Confusingly, the surrounding region (oblast) is still

known as Leningrad.

In the early twenty-first century, with a met-

ropolitan population of 4.8 million people, St. Pe-

tersburg is the second-largest city in Russia and the

fourth-largest in Europe (behind Moscow, London,

and Berlin). It is also Russia’s second-most impor-

tant industrial center, having benefited from Soviet

investment in heavy industry, research and devel-

opment, military-industrial production, and military

basing and training. The city is a major interna-

tional port and tourist destination, with tourists

flocking there in May and June for the legendary

“White Nights,” during which the sun seems to

never set.

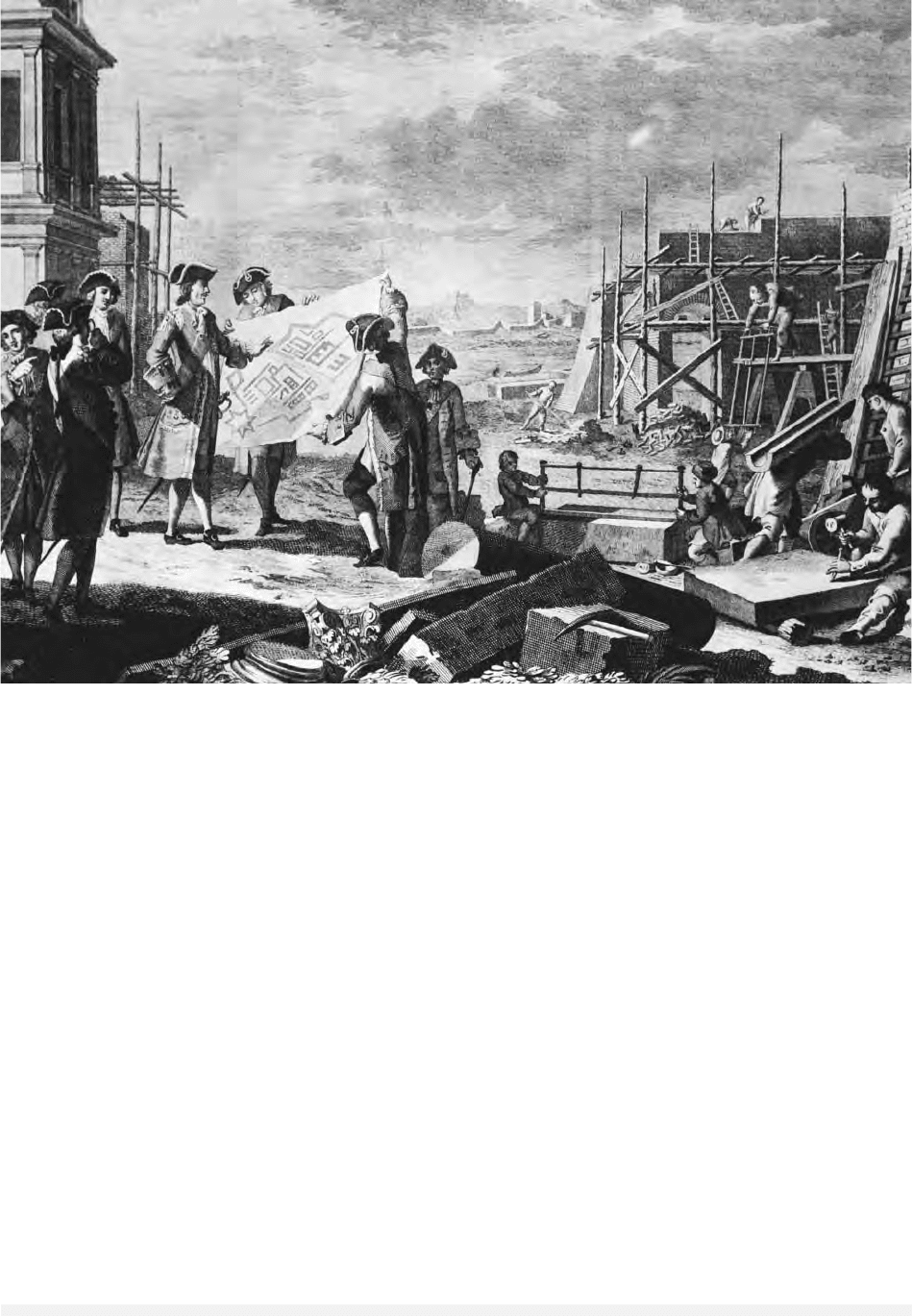

CAPITAL OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE

Peter the Great seized control over the confluence

of the Neva River and the Gulf of Finland from Swe-

den in 1703. Inspired by a visit to Amsterdam, he

decided to build a major city on this barren marsh-

land to better integrate Russia into Western Europe

and secure a Baltic port. Thousands of peasants and

prisoners-of-war were pressed into service to build

the city’s numerous canals and palaces. When the

harsh climate combined with malaria to kill tens

of thousands of them, their bodies were dumped

into the construction sites, leading to St. Peters-

burg’s nickname as the “city built on bones.” Con-

struction was hampered by floods, which also

ravaged the city in 1777, 1824, 1924, and 1955.

Empress Elizabeth, Peter’s daughter, improved

upon her father’s vision by commissioning Euro-

pean architects such as Bartolomeo Rastrelli to con-

struct baroque landmarks, including Winter Palace,

the Smolny Institute, and the palaces of Tsarskoe

Selo. Catherine II (the Great) subsequently pur-

chased the paintings, drawings, and other priceless

artworks that are now the core of the Hermitage

Museum’s holdings. She also established the Rus-

sian Academy of Arts to further aesthetic produc-

tion, and she commissioned the Pavlovsk Palace,

the Hermitage, and the Tauride Palace, later the

meeting place of the first Duma and the Provisional

Government.

The city’s remarkable transformation from

swamp to showcase paralleled the emergence of

Russia as a major European power, from Peter’s

1709 victory over the Swedes at Poltava to Alexan-

der I’s 1814 arrival in Paris. The city came to rep-

resent precisely this change from isolation to

European integration. Petersburg’s growing sym-

bolic dominance preoccupied the country’s intelli-

gentsia and nobility alike, with Tsar Nicholas I

ST. PETERSBURG

1483

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

complaining that “Petersburg is Russian but it is

not Russia.”

During the imperial era, Russia’s leading politi-

cians, intellectuals, and cultural figures were

brought together by the major institutions based

in St. Petersburg to generate events that vitally af-

fected the life of every member of Russian society.

The Decembrist uprising of 1825 culminated in

Senate (now Decembrist) Square. In January 1905,

Father Gapon led a peaceful march of workers and

their families to the Winter Palace to petition the

tsar; the resulting slaughter is remembered as

Bloody Sunday. Following that tragedy, the work-

ers of St. Petersburg became increasingly militant.

Forced to live and work in squalor due to Russia’s

rapid forced industrialization, they began to protest

and strike for improved conditions.

By the dawn of the twentieth century, the city

was the fifth-largest in Europe, behind London,

Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, and was widely viewed

as representative of imperial Russia’s new military

and industrial might. But with industrialization

there also emerged a surging revolutionary move-

ment, and “Red Petrograd” soon became the “cra-

dle of the Revolution.”

UNDER THE SOVIETS

With the outbreak of World War I in August 1914,

Nicholas II russified the capital city’s name to Pet-

rograd. In the early days of the war, the streets of

Petrograd were filled with young men volunteer-

ing for military service. But as Russian losses

mounted and the economy declined still further,

Petrograd became the focus of anti-tsarist senti-

ment. The Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Sol-

diers’ Deputies, founded in 1917 and modeled on a

1905 organization, was the most active. In March

(February O.S.) 1917, workers struck and soldiers

mutinied, leading to the eventual abdication of

Nicholas II. A Provisional Government was in-

ST. PETERSBURG

1484

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

An eighteenth-century engraving of Peter the Great supervising the construction of St. Petersburg. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

stalled, but constantly battled the Petrograd Soviet

for control of the city. During the “July Days,” the

Soviet nearly succeeded in gaining power. On No-

vember 7 (October 25, O.S.), members of Trotsky’s

Red Guards stormed the Winter Palace, and the Pro-

visional Government fled. For the next seventy-

four years, the communists would control Russia.

The Soviet regime’s shift of its seat of govern-

ment to Moscow in March 1918 stripped Petrograd

of many of its most creative and powerful institu-

tions and prominent individuals. The city was re-

named Leningrad after the death of Lenin in 1924.

Its standing was further undermined by the De-

cember 1934 assassination of Leningrad Party

leader Sergei Kirov in his office at the Smolny In-

stitute, which precipitated Josef Stalin’s mass purges.

Mass graves containing the victims were still be-

ing discovered outside the city as recently as 2002.

World War II took a particularly heavy toll on

Leningrad. For nine hundred days the Germans laid

siege to the city, and there were anywhere from

700,000 to more than 1 million civilian deaths from

attack and starvation. Although the Nazis never

entered the city proper, they looted and burned

many of the palaces in the environs, including Pe-

terhof and the Catherine Palace.

During the post-Stalin era Leningrad was an

important economic and intellectual center, though

still trailing Moscow. Aside from Kirov, one of

Leningrad’s best-known political leaders was the

rather ironically named Grigory Romanov. As first

secretary of the Leningrad Oblast Party Committee

from 1970 to 1983, Romanov encouraged produc-

tion and scientific associations, as well as links

among such groups to innovate and implement

new technologies. As a result, Leningrad achieved

enviable production levels. Romanov also made use

of the city’s extensive scientific establishment, link-

ing the research and production sectors to improve

production.

THE POST-SOVIET ERA

Although Romanov eschewed Mikhail Gorbachev’s

reforms, other Leningrad leaders embraced the

changes. Anatoly Sobchak was elected to the first

USSR Congress of People’s Deputies in 1989 and in

1991 became the city’s first elected mayor. A major

figure in Russia’s democratic movement, Sobchak

oversaw a difficult transition in his city. His resis-

tance to the hardline August 1991 putsch was crit-

ical to its defeat. Following the coup’s collapse,

Sobchak immediately renamed the city St. Peters-

burg. As the city’s economy suffered under the na-

tional shift to capitalism, St. Petersburg experienced

a severe rise in organized crime. Sobchak was un-

able to eradicate corruption, and in 1996 lost his

bid for reelection to Vladmir Yakovlev.

St. Petersburg is the cultural capital of Russia.

Among its most famous residents were the painters

Marc Chagall and Ilya Repin; the writers Nikolai

Gogol, Alexander Pushkin, Anna Akhmatova, and

Fyodor Dostoevsky; the composers Peter Tchaikov-

sky and Dmitry Shoshtakovich; and the choreog-

raphers Marius Petipa and Sergei Diaghilev. Among

its many art galleries, the Hermitage, the Russian

Museum, and the Stieglitz boast collections unpar-

alleled in the world. St. Petersburg is the home of

the renowned Mariinsky ballet company (known

as the Kirov in Soviet times). Shostakovich named

his Seventh Symphony Leningrad. Falconet’s Bronze

Horseman sculpture of Peter the Great, located in

Decembrist Square, was commissioned by Cather-

ine the Great and immortalized by Pushkin in a

poem of the same name. Many palaces and Or-

thodox churches have been restored, including the

Romanovs’ Winter Palace, St. Isaac’s Cathedral, and

the Kazan Cathedral. On the north bank of the

Neva, the Peter and Paul Fortress has a long his-

tory as both a prison and, in the Cathedral of Saints

Peter and Paul, the burial site of all the Romanov

tsars from Peter I to Nicholas II.

St. Petersburg had begun to recapture some its

lost splendor by 2003. UNESCO designated the city

a World Heritage site. Extensive renovation, funded

in part by a $31 million loan from the World Bank,

took place in preparation for the city’s tercenten-

nial celebration in May 2003. Partly contributing

to the city’s renaissance was the fact that President

Vladimir Putin was born in St. Petersburg. In addi-

tion to promoting the tercentennial commemora-

tion, Putin oversaw the renovation of the Peterhof

Palace into a world-class conference center. There

was also talk of creating a presidential residence in

St. Petersburg and even some sentiment to move the

capital from Moscow. Whether or not St. Peters-

burg regains the political eminence of a century ago,

it remains a vibrant, culturally rich European city,

much as Peter envisioned.

See also: ACADEMY OF ARTS; ADMIRALTY; BLOODY SUN-

DAY; CATHERINE II; DECEMBRIST MOVEMENT AND RE-

BELLION; ELIZABETH; MUSEUM, HERMITAGE; PETER I;

PETER AND PAUL FORTRESS; WINTER PALACE

ST. PETERSBURG

1485

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Glantz, David M. (2002). The Battle for Leningrad,

1941–1944. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

McAuley, Mary. (1991). Bread and Justice: State and So-

ciety in Petrograd, 1917–1922. New York: Oxford

University Press.

McKean, Robert B. (1990). St. Petersburg between the Rev-

olutions, June 1907–February 1917. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.

Ruble, Blair A. (1989). Leningrad: Shaping a Soviet City.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sablinsky, Walter. (1976). The Road to Bloody Sunday: Fa-

ther Gapon and the St. Petersburg Massacre of 1905.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Salisbury, Harrison E. (1969). The 900 Days: The Siege of

Leningrad. New York: Harper & Row.

A

NN

E. R

OBERTSON

B

LAIR

A. R

UBLE

STRATEGIC ARMS LIMITATION TREATIES

Coming on the heels of the 1968 nuclear Non-Pro-

liferation Treaty (NPT), the two components of the

Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT) repre-

sented a willingness by the United States and the

Soviet Union to constrain an arms race that both

recognized was costly and potentially destabilizing.

Soviet nuclear advantage in the early 1970s con-

cerned the United States, and the Soviets recognized

that American fears would likely translate into a

massive weapons program aimed at regaining nu-

clear superiority. Thus the Soviet Union chose to

forsake short-term advantage in favor of guaran-

teed parity over the long term. Both sides agreed

that strategic parity would significantly contribute

to stability.

The chief products of SALT I were the Anti-Bal-

listic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 1972, and an interim

agreement which set limits on the total number of

offensive missiles allowable (further addressed in

SALT II). The ABM Treaty limited the number of

defensive weapons, indicating that both the United

States and the Soviet Union accepted the idea that

mutual vulnerability would increase stability—

thereby institutionalizing mutual assured destruc-

tion (MAD). SALT II limited the total number of all

types of strategic nuclear weapons. However, al-

though agreed upon by both countries, SALT II was

never ratified because American President Jimmy

Carter withdrew his support after the Soviet inva-

sion of Afghanistan in December 1979.

While the SALT agreements represent important

progress in terms of quantitative arms limitation,

a significant flaw was that they failed to address

the issue of qualitative advancements in weapons

systems—which threatened the utility of the MAD

regime. This qualitative problem was addressed in

the subsequent Strategic Arms Reduction Talks.

See also: ANTI-BALLISTIC MISSILE TREATY; ARMS CON-

TROL; DÉTENTE; STRATEGIC ARMS REDUCTION TALKS;

STRATEGIC DEFENSE INITIATIVE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Payne, Samuel B., Jr. (1980). The Soviet Union and SALT.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wolfe, Thomas W. (1979). The SALT Experience. Cam-

bridge, MA: Ballinger.

M

ATTHEW

O’G

ARA

STRATEGIC ARMS REDUCTION TALKS

The Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) were

predicated on the concept of “minimum deter-

rence”—a regime in which both the United States

and the Soviet Union would reduce nuclear arse-

nals to the minimum level needed to deter the other

from attempting a first strike. As with previous bi-

lateral nuclear weapons treaties between the United

States and the USSR, the goal of START was to re-

duce the costs associated with a gratuitous arms

buildup, while simultaneously increasing system

stability by ensuring mutual vulnerability.

Prior agreements limited the number of weapons

each nation possessed, but advancements in tech-

nology made these previously agreed upon levels

untenable to the United States; in the early 1980s

it was perceived that the Soviet Union was close to

a first strike capability—the ability to attack

enough targets in the United States so as to pre-

vent a retaliatory strike.

This perception of a “window of vulnerability”

prompted the Reagan Administration to undertake

a massive weapons modernization program, in ad-

dition to pursuing the proposed Strategic Defense

Initiative (SDI). The Soviets believed that SDI was

destabilizing and therefore were willing to make

cuts in offensive nuclear arms in exchange for re-

STRATEGIC ARMS LIMITATION TREATIES

1486

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

strictions on American research and development

of space-based defensive systems. As with the

Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT), the So-

viet Union was once again forsaking short-term

superiority in favor of long-term stability.

START mandated cuts in the number of nu-

clear delivery systems by about 40 percent, reduced

the number of warheads by roughly 30 percent,

and also established more complete verification pro-

cedures.

The treaty was signed by President George Bush

and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev on July 31,

1991 in Moscow.

See also: ANTI-BALLISTIC MISSILE TREATY; ARMS CON-

TROL; DÉTENTE; STRATEGIC DEFENSE INITIATIVE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kartchner, Kerry M. (1992). Negotiating START: Strategic

Arms Reduction Talks and the Quest for Strategic Sta-

bility. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Mazarr, Michael J. (1991). START and the Future of De-

terrence. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

M

ATTHEW

O’G

ARA

STRATEGIC DEFENSE INITIATIVE

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was a United

States military research program that President

Ronald Reagan first proposed in March 1983,

shortly after branding the USSR an “evil empire.”

Its goal was to intercept incoming missiles in mid-

course, high above the earth, hence making nuclear

weapons “impotent and obsolete.” Nicknamed “Star

Wars” by the media, the program entailed the use

of space- and ground-based nuclear X-ray lasers,

subatomic particle beams, and computer-guided

projectiles fired by electromagnetic rail guns—all

under the central control of a supercomputer sys-

tem.

The Reagan administration peddled the pro-

gram energetically within the United States and

among NATO allies. In April 1984 a Strategic De-

fense Initiative Organization (SDIO) was established

within the Department of Defense. The program’s

futuristic weapons technologies, several of which

were only in a preliminary research stage in the

mid-1980s, were projected to cost anywhere from

$100 billion to $1 trillion.

After Reagan’s SDI speech, General Secretary

Yuri Andropov denounced the program, telling a

Pravda reporter that if Washington implemented

SDI, the “floodgates of a runaway race of all types

of strategic arms, both offensive and defensive”

would open. Painfully aware of U.S. scientific and

engineering skills, the Soviet leadership sought to

eschew a costly technological arms race in which

the United States was stronger.

With the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and

USSR, signing of the START I and II treaties, and

the 1992 presidential election of Bill Clinton, the

SDI received lower budgetary priority (like many

other weapons programs). In 1993 Defense Secre-

tary Les Aspin announced the abandonment of SDI

and its replacement by a less costly program that

would make use of ground-based antimissile sys-

tems. The SDIO was then replaced by the Ballistic

Missile Defense Organization (BMDO).

In contrast to the actual expenditures on SDI

(about $30 billion), spending on BMDO programs

exceeded $4 billion annually in the late 1990s.

See also: ANTI-BALLISTIC MISSILE TREATY; ARMS CON-

TROL; DÉTENTE; STRATEGIC ARMS REDUCTION TALKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anzovin, Steven. (1986). The Star Wars Debate. New

York: Wilson.

Boffey, Philip M. (1988). Claiming the Heavens: The New

York Times Complete Guide to the Star Wars Debate.

New York: Times Books.

FitzGerald, Frances. (2000). Way Out There in the Blue:

Reagan, Star Wars, and the End of the Cold War. New

York: Simon & Schuster.

FitzGerald, Mary C. (1987). Soviet Views on SDI. Pitts-

burgh, PA: Center for Russian and East European

Studies, University of Pittsburgh.

Teller, Edward. (1987). Better a Shield than a Sword: Per-

spectives on Defense and Technology. New York: Free

Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

STRAVINSKY, IGOR FYODOROVICH

(1882–1971), Russian composer.

Among the most influential composers of the

twentieth century, Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky

epitomized the new prominence of Russian emigré

STRAVINSKY, IGOR FYODOROVICH

1487

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

creative artists and their presence on the interna-

tional scene in the years following the 1917 Revo-

lution. Like the contributions of his emigré

colleague writer Vladimir Nabokov and choreogra-

pher George Balanchine-Stravinsky’s enormous

contribution to his art significantly altered the

course of twentieth-century music. Stravinsky’s

compositions encompass every important musical

trend of the period (neonationalism, neoclassicism,

and serialism, to name a few) and include exam-

ples of all the major Western concert genres (opera,

ballet, symphony, choral works, solo works, and

numerous incidental works, including a polka for

circus elephants).

The son of a St. Petersburg opera singer, Stra-

vinsky attained international fame with his early

ballet, The Firebird (1910), composed for Sergei Di-

agilev’s Ballets Russes (with choreography by

Michel Fokine). Several important ballets followed,

including Petrushka (1911, also with Fokine) and

the seminal Rite of Spring (1913, choreography by

Vaslav Nijinsky), among the most famous works

of art of the twentieth century. Stravinsky’s com-

positions for the theater continued to trace a path

through the most significant musical and theatri-

cal idioms of his century, and include Les Noces

(1923, choreography by Bronislava Nijinska), Apol-

lon musagète (1928), and Agon (1957, both chore-

ographed by Balanchine). Although Stravinsky was

a supremely cosmopolitan figure, his music

nonetheless retained traces of its Russian origins

throughout his long career.

See also: DIAGILEV, SERGEI PAVLOVICH; FIREBIRD; MUSIC;

PETRUSHKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Stravinsky, Vera, and Craft, Robert. (1978). Stravinsky

in Pictures and Documents. New York: Simon and

Schuster.

Taruskin, R. (1996). Stravinsky and the Russian Tradi-

tions. Berkeley: University of California Press.

White, Eric Walter. (1979). Stravinsky: the Composer and

His Works. Berkeley: University of California Press.

T

IM

S

CHOLL

STRELTSY

The musketeers, or streltsy (literally “shooters”),

were organized as part of Ivan IV’s effort to reform

Russia’s military during the sixteenth century. In

1550 he recruited six companies of foot soldiers

armed with firearms, organized into tactical units

of five hundred, commanded and trained by offi-

cers from the nobility. These units were based from

the beginning in towns, and eventually took on the

character of garrison forces. Over time their num-

bers grew from three thousand in 1550 to fifty

thousand in 1680.

Militarily, they were ineffectual, mainly be-

cause of their economic character. The musketeers

were a hereditary class not subject to taxation, but

to state service requirements, including battlefield

service, escort, and guard duties. During the sev-

enteenth century, the state provided them with

grain and cash, but economic privileges, including

permission to act as merchants, artisans, or farm-

ers, became their principal support. One particular

plum was permission to produce alcoholic bever-

ages for their own consumption. They also bore

civic duties (fire fighting and police) in the towns

where they lived. Pursuing economic interests re-

duced their fighting edge.

Throughout the seventeenth century the mus-

keteers proved to be fractious, regularly threaten-

ing, even killing, officers who mistreated them or

represented modernizing elements within the mil-

itary. By 1648 it was apparent that they were un-

reliable, especially when compared with the

new-formation regiments appearing prior to the

Thirteen Years War (1654–1667) under leadership

of European mercenary officers. Rather than dis-

band the musketeers entirely, the state made at-

tempts to westernize them. Many units were placed

under the command of foreigners and retrained.

Administrative changes were made during and af-

ter the war, including placing certain units under

the jurisdiction of the tsar’s Privy Chancery, which

appointed officers and collected operations reports.

The Privy Chancery, and by extension, the tsar,

was at the center of the attempt to transform the

musketeers into more thoroughly trained western-

style infantry.

Further pressure to reform included official ne-

glect, even to the point of refusing to give the mus-

keteers weapons. Later decrees (1681, 1682)

replaced cash payments with grants of unsettled

lands as compensation for service. This change in

support reduced their status, without improving

their overall military effectiveness, and the muske-

teers vehemently opposed it. By 1680, many regi-

ments had been retrained and officered by foreigners,

but the conservative musketeers were anxious to

be rid of the hated foreigners and regain their eroded

STRELTSY

1488

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

prestige. Thus, in 1682, they were willing to be-

lieve rumors that Tsar Fyodor Alexeyevich had been

poisoned, and were anxious to punish those re-

sponsible with death.

Peter I’s (the Great) reign was marred by an

uprising in 1698 of military units stationed in

Moscow called musketeers or streltsy (literally,

“shooters”). The musketeers disliked the tsar’s

westernizing policies and governing style. Peter re-

jected traditional behaviors and practices, including

standards of dress, grooming, comportment, and

faith, but more importantly, he sought to reform

Russia’s military institutions, which threatened the

musketeers’ historical prerogatives.

Peter crushed the rebellion with great severity,

executing nearly twelve hundred musketeers, and

flogging and exiling another six hundred. The

Moscow regiments were abolished and survivors

sent to serve in provincial units, losing privileges,

homes, and lands. They carried with them seeds of

defiance that eventually bore fruit in Astrakhan in

1705–1706, and among the Cossacks in 1707–

1708. Although the last Moscow regiments of

musketeers disappeared before 1713, the muske-

teers continued to exist in the provinces until after

Peter’s death.

Peter’s response to the 1698–1699 uprising

may have arisen from his memories of the 1682

musketeer revolt. The musketeers suspected the

Naryshkins (Peter’s mother, Natalia’s family) of

having poisoned Tsar Fyodor and of planning to

kill the Tsarevich Ivan, both sons of Tsar Alexei’s

first wife, Maria Miloslavskaya. The Miloslavskys

encouraged these suspicions in order to use their

regiments against the Naryshkins. On May 25,

1682, the musketeers attacked the Kremlin. Natalia

Naryshkina showed Ivan and Peter to the rioting

musketeers to prove they were still alive. Nonethe-

less, the rebellion was bloody, and the government

was powerless because it had no forces capable of

stopping the musketeers. From this rebellion came

the joint reign of Ivan and Peter with their sister

and half-sister, Sophia, who issued decrees in their

names, and who was a favorite of the musketeers.

In 1698 the streltsy were unable to see that Pe-

ter I was implacable in his rejection of conservatism

and that the musketeers represented for him a dan-

gerous and disloyal element. In the final clash, the

musketeers were unable to reshape their world, and

eventually disappeared.

See also: FYODOR ALEXEYEVICH; IVAN IV; PETER I; SOPHIA;

WESTERNIZERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1971). Enserfment and Military Change in

Muscovy. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1990). Sophia, Regent of Russia

1657–1704. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the

Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

W. M. R

EGER

IV

STRIKES See WORKERS.

STROIBANK

Stroibank USSR (the All-Union Bank for Invest-

ment Financing) managed and financed govern-

ment investment in the Soviet period. Founded as

Prombank (the Industrial Bank) in October 1922,

it merged with several smaller banks and became

Stroibank during the April 1959 banking reform.

The USSR Council of Ministers appointed its board

of directors, and it was officially part of the Gos-

bank (State Bank of the USSR) network. It sup-

ported government investment both through direct

(nonrepayable) financing and through short- and

long-term credits. In 1972 Stroibank had over 1,200

subsidiary components throughout the USSR.

In 1988 a series of economic reforms created a

two-tiered banking system in Russia. Gosbank be-

came a central bank, while three specialized banks

split from Gosbank. During this process, Stroibank

USSR became Promstroibank USSR (the Industrial-

Construction Bank). During the battle for sover-

eignty between Russian and Soviet leaders in 1990

and 1991, Promstroibank USSR was commercial-

ized and individual branches given the opportunity

to strike out on their own or form smaller net-

works with other Promstroibank branches. The

largest remnant of the Promstroibank network,

Promstroibank Russia, remained under the control

of former Promstroibank USSR director Yakov

Dubnetsky. Promstroibank Russia remained a large

and powerful bank throughout the 1990s, while

many reorganized Promstroibank USSR branches

retained strong positions in Russia’s regions and

continued to serve their traditional clients. In the

late 1990s, the state-owned energy giant Gazprom

acquired a controlling interest in Promstroibank

Russia.

See also: BANKING SYSTEM, SOVIET; ECONOMY, POST-

SOVIET; GOSBANK; SBERBANK

STROIBANK

1489

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Johnson, Juliet. (2000). A Fistful of Rubles: The Rise and

Fall of the Russian Banking System. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press.

Kuschpèta, Olga. (1978). The Banking and Credit System

of the USSR. Leiden, Netherlands: Nijhoff Social Sci-

ences Division.

J

ULIET

J

OHNSON

STRUMILIN, STANISLAV GUSTAVOVICH

(1877–1974), economist, statistician, and demog-

rapher.

Stanislav Gustavovich Strumilo-Petrashkevich

was a Social Democrat (Menshevik) before 1917.

Involved in revolutionary activities, he was arrested

several times.

In the Soviet period, Strumilin held various

high positions in the State Planning Board Gosplan

(deputy chairman several times, chairman of the

economic-statistical section during the 1920s) and

in the Academy of Sciences of the USSR (1931 full

membership and doctor of economics honoris

causa). For decades he also worked as a professor.

Strumilin published on economic planning,

the economics of labor, industrial statistics, and

economic history, and he took sides in all impor-

tant economic debates. He combined theoretical ar-

gumentation with empirical statistics and also

incorporated sociological perspectives (e.g., in his

pioneering time-budget studies). During the politi-

cized economic debates of the 1920s, he was a

radical advocate of a planned economy and re-

sponsible for the drawing up of the First Five-

Year-Plan. He opted for the teleological method of

planning, which takes the final (production) tar-

gets as a starting point. His demographic works,

among them a prediction regarding the number

and age–sex composition of the population of Rus-

sia for 1921–1941, were influential in the Soviet

Union and gained international attention.

Strumilin managed to survive the purges of the

Josef Stalin period and benefited from the rehabil-

itation of the economists after World War II. He

then concentrated on labor issues and the impact

of education on wage differentials, participated ac-

tively in the economic debates of the 1950s and

1960s, and published until 1973. He represented

the first generation of Soviet Marxist economists.

See also: FIVE-YEAR PLANS; GOSPLAN; MENSHEVIKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nove, Alec. (1969). The Soviet Economy. An Introduction,

2nd ed. New York: Praeger.

J

ULIA

O

BERTREIS

STRUVE, PETER BERNARDOVICH

(1870–1944), liberal political leader, economist,

and author.

As a young man Peter Bernardovich Struve rose

to prominence on the liberal left. In the 1890s he

joined the Social Democratic party and authored its

manifesto. He was then a proponent of a moder-

ate legal Marxism. Struve, however, was not a doc-

trinaire. He was dedicated to learning and loved

literature and poetry. By contrast, the Russian mil-

itants saw such a pursuit as a distraction from the

task of revolution.

As Russia moved toward revolution Struve

moved toward a liberal conservatism. From 1902

to 1905 he edited the journal Osvobozhdenie (Liber-

ation), a liberal publication. He eventually joined the

Constitutional Democratic party (Cadet). In 1906

he won election as a deputy to the second Duma.

In 1909 he contributed to Vekhi (Landmarks) as one

of a group of prominent intellectuals who broke

sharply with the militant leftists, seeing them as a

threat to Russia’s liberation from despotism and its

transformation into a liberal and democratic con-

stitutional state. He was deeply patriotic as well as

liberal in orientation. In 1911 he wrote a series en-

titled Patriotica. From 1907 to 1917 he engaged in

scholarship as well as politics as a professor at the

St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute. After the 1917

October Revolution Struve briefly joined an anti-

Bolshevik government in southern Russia and then

was forced to emigrate to the West where he spent

the remainder of his life as a scholar and writer on

economics and politics.

See also: CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; SOCIAL

DEMOCRATIC WORKERS PARTY; VEKHI

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Pipes, Richard. (1970). Struve: Liberal on the Left, 1870–

1905. Russian Research Center Studies, no. 64. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pipes, Richard. (1980). Struve: Liberal on the Right,

1905–1944. Russian Research Center Studies, no. 80.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

C

ARL

A. L

INDEN

STRUMILIN, STANISLAV GUSTAVOVICH

1490

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

STUKACH

From the common slang word stukachestvo, stukach

was widely used in the Soviet period to describe

“squealing,” or informing on people to the gov-

ernment authorities. The word is evidently derived

from stuk, Russian for the sound of a hammer

blow.

The government, and especially the security

police, in all communist-ruled or authoritarian

countries, depended on informers in order to keep

tabs on the loyalty of the populace. In the Politics,

Aristotle had observed that tyrannical regimes

must employ informers hidden within the popula-

tion in order to keep their hold on absolute power.

In such countries as the USSR, Nazi Germany,

Maoist China, Cuba, and so forth, informers were

sometimes made heroes by the regime. Thus, in the

Soviet Union, Pavlik Morozov, a twelve-year-old

boy living in the Don farming region when Stalin

was enforcing collectivization of the peasants’ farms

in the early 1930s, became a stukach. He informed

on his parents when they allegedly concealed grain

and other produce from the authorities. The boy

was killed by vengeful farmers. He was thereupon

iconized as a martyr by the communist authori-

ties. Statues of Pavlik sprang up throughout the

country.

The Soviet writer Maxim Gorky urged fellow

writers to glorify the boy who had exposed his fa-

ther as a kulak and who “had overcome blood kin-

ship in discovering spiritual kinship.” Another

well-known Soviet novelist, Leonid Leonov, de-

picted a fictitious scientist of the old generation who

as a stukach had nobly betrayed his son to the au-

thorities.

Stukachestvo was expected of any and all fam-

ily members, schoolchildren, concentration-camp

prisoners, factory workers—in short, every Soviet

citizen, all of whom were expected to place loyalty

to the State above all other linkages.

See also: GORKY, MAXIM; MOROZOV, PAVEL TROFIMOVICH;

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Galler, Meyer. (1977). Soviet Prison Camp Speech: A Sur-

vivor’s Glossary: Supplement. Hayward, CA: Soviet

Studies.

Heller, Mikhail, and Nekrich, Aleksandr. (1986). Utopia

in Power: The History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to

the Present, tr. Phillis B. Carlos. London: Hutchinson.

Preobrazhensky, A. G. (1951). Etymological Dictionary of

the Russian Language. New York: Columbia Univer-

sity Press.

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

STÜRMER, BORIS VLADIMIROVICH

(1848–1917), government official who reached the

rank of president of the State Council, or premier,

of the Russian Empire.

Boris Stürmer studied law at St. Petersburg

University and then entered the Ministry of Jus-

tice. He was appointed governor of Novgorod

Province in 1894 and of Yaroslav Province in 1896.

In 1902 he became director of the Department of

General Affairs of the Ministry of the Interior and

in 1904 was appointed to the Council of State.

From January to November 1916 he was president

of the Council of State, serving simultaneously as

minister of the interior (March–July) and minister

of foreign affairs (July–November). Nicholas II dis-

missed Stürmer after Paul Milyukov’s famous “Is

this stupidity or is it treason?” speech in the Duma,

in which Milyukov accused Stürmer of being a Ger-

man agent. In fact, he was not. Arrested after the

February Revolution of 1917 and placed in the Pe-

ter and Paul Fortress, Stürmer died there in August

1917.

Stürmer owed his rise to his arch-conservatism

and friends in high places, including the Empress

Alexandra Fyodorovna and Grigory Rasputin, who

reputedly referred to Stürmer as “a little man on a

leash” and to whom Stürmer reported weekly and

received instructions. Stürmer has received univer-

sal scorn. Contemporaries called him a “nonentity”

(Vasily Shulgin), “totally ignorant of everything he

undertook” (Milyukov), “a man of extremely lim-

ited mental gifts” (Nikolai Pokrovsky, his succes-

sor as minister of foreign affairs), “a man who had

left a bad memory wherever he occupied an ad-

ministrative post” (Sergei Sazonov), and “an utter

nonentity” (Mikhail Rodzianko). Historians have

seen Stürmer as “an instrument of the personal rule

of the Empress [and Rasputin]” (Mikhail Florinsky),

“a reactionary [who] brought discredit on the

extreme Right” (Marc Ferro), and “an obscure and

dismal product of the professional Russian bu-

reaucracy” (Robert Massie).

See also: ALEXANDRA FEDOROVNA; RASPUTIN, GRIGORY

YEFIMOVICH

STÜRMER, BORIS VLADIMIROVICH

1491

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Florinsky, Mikhail. (1931). The End of the Russian Empire.

Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for Interna-

tional Peace.

Fulop-Muller, Renee. (1929). Rasputin: The Holy Devil.

New York: Viking Books.

Miliukov, Paul. (1967). Political Memoirs. Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Press.

S

AMUEL

A. O

PPENHEIM

SUBBOTNIK

Communist subbotniki (Communist Volunteer Sat-

urday Workers) were shockworkers who volun-

teered their free Saturdays for the Bolshevik cause.

Subbotniki were lauded as heroes of socialist

labor, as prototypes of the new unselfish man, and

role models for the working class. Their actions

may have reflected spontaneous enthusiasm among

some workers, but they were also encouraged by

the Communist Party to mobilize effort. The phe-

nomenon was a mixture of socialist idealism and

coercion.

The KS (Communist subbotniki) movement is

said to have started by the communists on April

12, 1919 at the Moscow-Kazan railway depot, and

was praised by Vladimir Lenin in an article entitled

“Velikii pochin,” July 28, 1919. During the sum-

mer and autumn of 1919, KS mobilized to defeat

Denikin, and surmount the “fuel crisis.”

During World War II, the KS and voskresniki

(Sunday volunteers) are said to have inspired the

war effort. Celebrations commemorating their

achievements and encouraging the movement’s

continuation were held frequently during the sev-

enties.

See also: SOVIET MAN; STAKHANOVITE MOVEMENT

S

TEVEN

R

OSEFIELDE

SUBWAY SYSTEMS

The original line of the Moscow metro, completed

in May 1935, laid the foundation for one of the

world’s most impressive subway systems. In its

first fifty years, the Moscow metro grew from thir-

teen stations to more than 120, and the average

number of passengers carried daily increased from

177,000 to more than six million, making the

Moscow system the world’s busiest. The Moscow

metro organization also reproduced its various

structures in similar metro systems across the for-

mer Soviet Union and behind the Iron Curtain. It

became, in the words of one official, “the mother

of all socialist metros.” Symbols of Soviet power

accompanied riders in the metros of Leningrad,

Kiev, Kharkov, Baku, Tiflis, Tashkent, Minsk,

Gorky, Erevan, Novosibirsk, Sverdlovsk, and Vol-

gograd—not to mention those systems built partly

by Moscow engineers and architects in Poland and

Czechoslovakia.

For Soviet leaders, Soviet subways were more

than transportation systems. The metro provided

what one Soviet propagandist called “a majestic

school in the formation of the new man.” For the

1935 inaugural line of the Moscow metro, the So-

viets constructed each of the stations on different

themes of socialist life. Stations celebrated Soviet

leaders, the Communist Party, Soviet achievements

in education, and the supposed superiority of the

Soviet system. The Soviets lavished scarce resources

on the first thirteen stations, including 23,000

square meters of marble facing, chandeliers, and

crystal. Metro builders boasted that they used more

marble in the first line of the Moscow metro than

had been used in the entire Tsarist period. Through

the end of the Stalin era, stations became more or-

nate and monumental as the metro grew. Like a

mirror held up to Soviet self-perceptions, an elab-

orate political iconography reflected a sense of ap-

proaching perfection in Soviet society. To convey

this message, architects calculated that a passenger

would spend roughly five minutes per station. In

the words of one: “Within that time the architec-

ture, emblems, and entire artistic image should ac-

tively influence him.” Soviet subway systems thus

celebrated Soviet socialism, provided a pulpit for

preaching its values, and offered an effective way

to get to work in the morning.

Lazar Kaganovich, a ruthless Bolshevik leader

of working-class origin, assumed managerial re-

sponsibility for construction of the original metro

line. His chief deputy on the project was Nikita

Khrushchev, who later became general secretary of

the Communist Party. Kaganovich believed that the

metro “went far beyond . . . the typical under-

standing of a technological construction. Our met-

ropolitan is a symbol of the new socialist society

being built.” Under his management, the Soviets

deployed a variety of improvised Western tech-

SUBBOTNIK

1492

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY