Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

speaking peoples, and so the connection with a peo-

ple speaking a vastly different language is difficult

to make.

See also: CAUCASUS; DAGESTAN DARGINS; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ethnologue <www.ethnologue.com>

Hill, Fiona. (1995). Russia’s Tinderbox: Conflict in the North

Caucasus and its Implication for the Future of the Russ-

ian Federation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Karny, Yoav. (2000). Highlanders: A Journey to the Cau-

casus in Quest of Memory. New York: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux.

P

AUL

C

REGO

AVIATION

Defined as the science and practice of powered,

heavier-than-air flight, aviation made its first great

strides in the early twentieth century, after decades

of flights in lighter-than-air gliders and balloons

had been achieved in several countries. As ac-

knowledged in reference books worldwide, includ-

ing those of Soviet Russia, the first successful flight

of an airplane was performed one hundred years

ago by Orville and Wilbur Wright on December 17,

1903. Throughout the nineteenth century, how-

ever, designers and engineers in many countries

were working on plans for powered human flight.

In Russia, Sergi Alexeyevich Chaplygin

(1869–1942) and Nikolai Yegorovich Zhukovsky

(1847–1921) made major contributions in their

study of aerodynamics, founding a world-famous

school in St. Petersburg, Russia. In 1881, Alexander

Fyodorovich Mozhaisky (1823–1890) received a

patent for a propeller-driven, table-shaped airplane

powered by a steam engine, which crashed on take-

off in 1885. From 1909 to 1914, however, Russia

made significant strides in airplane design. Progress

included several successful test flights of innovative

aircraft. For instance, the Russian aircraft designer

Yakov M. Gakkel (1874–1945) achieved worldwide

attention among aviation experts for developing a

single-seat, motor-powered biplane that attracted

world attention among aviation experts. In 1910,

Boris N. Yuriev (1889–1957) designed one of the

world’s first helicopters, which were known in avi-

ation’s earlier days as autogyros.

A major breakthrough in world aviation oc-

curred in 1913, with the development of the four-

motored heavy Russian aircraft, the Ilya Muromets.

This huge airplane far outstripped all other planes

of its time for its size, range, and load-carrying ca-

pability. Russian ice- and hydroplane development

was also outstanding in the years 1915 and 1916.

One of the world famous Russian aircraft designers

of this period, and the one who built the Muromets,

was Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky (1889–1972), who

emigrated to the United States in 1919 and estab-

lished a well-known aircraft factory there in 1923.

Before and during World War I, Russian mili-

tary aircraft technical schools and aviation clubs

blossomed. In the war, the Russians deployed thirty-

nine air squadrons totaling 263 aircraft, all bear-

ing a distinctive circular white, blue, and red

insignia on their wings. With the coming to power

of the Communists in late 1917, Lenin and Stalin,

who stressed the importance of military produc-

tion and an offensive strategy, strongly supported

the development of the Red Air Force. Civilian

planes, too, were built, for what became the world’s

largest airline, Aeroflot.

By the time of World War II, the Soviets had

made significant strides in the development of all

types of military aircraft, including fighters and

bombers, gliders and transport planes, for both the

Red Army and Red Navy. By the time of the Ger-

man invasion of the USSR in June 1941, various

types of Soviet aircraft possessed equal or superior

specifications compared to the planes available to

their Nazi German counterparts. This achievement

was possible not only because of the long, pre-

revolutionary Russian and postrevolutionary So-

viet experience in designing and building aircraft

and participating in international air shows.

Progress in this field also stemmed from Soviet

strategic planning, which called for offensive

air–ground support in land battle.

During World War II, such aircraft as the

Shturmoviks, Ilyushins, and Polikarpovs became

world famous in the war, as did a number of male

and female Soviet war aces. With the coming of

jet-powered and supersonic aircraft in the 1950s

and beyond, the Soviets continued their quest for

air supremacy, and again showed their prowess in

aviation.

See also: SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY; WORLD WAR

I; WORLD WAR II

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

AVIATION

103

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

AVVAKUM PETROVICH

(1620–1682), one of the founders of what came to

be called Old Belief.

Avvakum was a leading figure in the opposi-

tion to Patriarch Nikon and the program of church

reform he directed. Nikon’s removal from his post

did not placate Avvakum. He continued to agitate

against the program of church reform and its sup-

porters until his execution.

Avvakum was born on November 20, 1620, to

a priest and his wife in the village of Grigorovo in

the Nizhny Novgorod district. In 1638 he married

Anastasia Markovna, the daughter of a local black-

smith. She was a devoted wife and true compan-

ion to Avvakum until his death. Following in the

footsteps of his father, Avvakum entered the secu-

lar clergy. In 1642 he was made a deacon at a vil-

lage church in the Nizhny Novgorod district. Two

years later he was ordained a priest.

Avvakum was appalled by the ignorance, dis-

orderliness, and impiety of popular religious prac-

tices and early in his career manifested a zeal for

reform. By 1647 Avvakum was associated with the

Zealots of Piety, a Moscow-based group led by Tsar

Alexis Mikhailovich’s confessor, the archpriest of

the Annunciation Cathedral, Stefan Vonifatiev. Av-

vakum’s enthusiasm for religious and moral re-

form was not matched by that of his provincial

parishioners and soon brought him into conflict

with the local authorities. His house was burned,

and he was compelled to flee with his family to

Moscow. There he found refuge with Stefan Voni-

fatiev. Avvakum returned to his parish in the

Nizhny Novgorod district to continue his work, but

by 1652 was obliged to flee to Moscow again. Av-

vakum soon was assigned to Yurevets-Povolsky

and elevated to archpriest, but by the end of 1652

he was back in Moscow, serving at the Kazan

Cathedral with Ivan Neronov, a man Avvakum rec-

ognized as his mentor.

Avvakum was an ardent supporter of religious

and spiritual reform, but not of the liturgical re-

forms advocated by other members of the Zealots

of Piety. In early 1653 Avvakum joined Neronov

and others in protest against some changes and

simplifications made in the Psalter, recently printed

under the direction of Patriarch Nikon. Vocal and

adamant in opposition, Ivan Neronov was arrested

on August 4, 1653. The arrest of Avvakum and

other supporters followed on August 13. Thanks

to the personal intervention of the tsar, Avvakum

escaped defrocking and exile to a monastery. In-

stead he and his family were transferred to the dis-

tant and less desirable post of Tobolsk in Siberia,

where he served as archpriest until the end of July

1655. In Tobolsk, despite the support and protec-

tion of Governor Vasily Ivanovich Khilkov and

Archbishop Simeon, Avvakum’s abrasive approach

ignited conflict and contention. In 1656, to remove

him from the scene of contention, the tsar ordered

Avvakum to accompany an expeditionary force led

by Commander Afanasy Pashkov, intended to

pacify and bring Christianity to the native tribes of

northern Siberia. The assignment was not a suc-

cess. Avvakum’s religious zeal alienated many of

the soldiers and enraged the commander. In his Life,

Avvakum vividly recounted the multiple humilia-

tions and torments inflicted upon him by Pashkov.

In 1657 Pashkov sent a petition to Moscow, os-

tensibly written by several of the soldiers, accus-

ing Avvakum and his supporters of fomenting

rebellion and requesting that the archpriest be con-

demned to death. Once again, Avvakum’s friends

in high places came to his aid. Archbishop Simeon

of Tobolsk intervened, and in 1658 Pashkov was

replaced as commander of the expedition.

In the spring of 1661 Avvakum was directed

to return to Moscow with his family. Difficulties

along the way and a stop in Ustiug Veliky slowed

the journey. The family did not arrive in Moscow

until the beginning of 1664. Much had changed.

In 1658 Patriarch Nikon had quarreled with the

tsar and abandoned the patriarchal throne. The un-

precedented act caused consternation and confu-

sion, but it did not shake the commitment to

church reform, including liturgical reform. The tsar

and his closest associates received Avvakum gra-

ciously. The zealous archpriest met and conversed

with the leading figures behind the continuing re-

form program, including Simeon Polotsky and Epi-

fany Slavinetsky. He debated changes introduced

into the rituals by the new liturgical books with

Fyodor Rtishchev, arguing that, among other

things, the sign of the cross must be made with

three fingers, rather than two. The three-fingered

sign of the cross would become a visible symbol

for those who opposed the so-called Nikonian re-

forms. Further, Avvakum challenged the assertions

of Rtishchev and others that “rhetoric, dialectic, and

philosophy” had a role to play in religious under-

standing. In this period, Avvakum was even offered

a post as corrector (spravshchik) at the Printing Of-

fice, the center of activity for the revision and print-

ing of the new church service books and other

religious works.

AVVAKUM PETROVICH

104

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

If such efforts were intended to mollify Av-

vakum, bring him back into the circle of reform-

ers, and gain his talents for the ongoing process of

church reform, they failed. Avvakum remained in-

transigent in his opposition to all changes intro-

duced in the religious rituals and in the printed

service books, petitioning the tsar to intervene and

preaching his dissident views publicly. In this same

period he became the confessor to the noblewoman

Feodosia Morozova and her sister, Princess Yev-

dokia Urusova, convincing them of the correctness

of his position. Both sisters accepted Avvakum’s

views and in 1675 suffered martyrdom rather than

recant.

In August 1664 Avvakum and his family once

again were dispatched into exile in Siberia, arriving

in Mezen at the end of the year. A year later, Av-

vakum was recalled to Moscow to appear before a

church council (1666). At this important council

Nikon officially was removed as patriarch, but the

reform program itself was affirmed. Those who ac-

tively opposed the reforms, including the revised

service books, were tried. Some, such as Ivan

Neronov, recanted. Others, led by Avvakum, stood

firm. Following the council, Avvakum was de-

frocked, placed under church ban, and imprisoned

in chains in a monastery. Subsequent attempts to

persuade him to repent failed. In August 1667, Av-

vakum and his supporters were sentenced to exile

in Pustozersk in the remote north. Two of Av-

vakum’s friends and supporters, Lazar and Epifany,

also exiled, had their tongues cut out; Avvakum

was spared this punishment. By the end of the year

the prisoners reached their destination.

Exile and prison did not deter Avvakum from

indefatigably petitioning the tsar and communi-

cating with his followers. In the 1670s repression

of religious dissidents increased. Avvakum, his

family, and the small band of prisoner-exiles in

Pustozersk were subjected to new afflictions.

Moreover, the colony increased with the addition

of those seized after the suppression in 1676 of

a rebellion at the Solovetsky monastery, ostensi-

bly against the new service books. In the mean-

time, religious dissenters incited disturbances in

Moscow and other towns and villages. Frustrated

in all attempts to silence the dissidents, in 1682

the church council transferred jurisdiction to the

secular authorities. An investigation was ordered,

and on April 14, 1682, Avvakum was burned at

the stake, “for great slander against the tsar’s

household.”

Avvakum is remembered primarily as a found-

ing father of the movement known in English as

Old Belief, a schismatic movement that assumed a

coherent shape and a growing following from the

beginning of the eighteenth century. In Avvakum’s

lifetime, however, he was engaged in a relatively

esoteric dispute with other educated members of

the clerical and lay elites. He attracted a circle of

devoted disciples and supporters, but not a mass

following. His position as one of the founding fa-

thers of Old Belief rests on the lasting influence of

his writings, which were collected, copied, and dis-

seminated. Avvakum was a prolific writer of peti-

tions to the tsar, letters of advice and exhortation

to his acquaintances, sermons, polemical tracts,

and pamphlets. All contributed to the shape of Old

Belief as an evolving movement. An important ex-

ample of Avvakum’s dogmatic and polemical work

is The Book of Denunciation, or the Eternal Gospels (c.

1676). Written by Avvakum as part of a dispute

with one of his disciples, this tract clarified his posi-

tion on several dogmatic issues. This work contin-

ued to be a focal point of criticism for spokesmen of

the official church into the early eighteenth century.

In addition to their religious significance, Av-

vakum’s writings are of considerable interest to lin-

guists and literary historians. His writing style was

forceful and dramatic. He juxtaposed great erudi-

tion with penetrating direct observation and mixed

the tonalities and phraseology of the popular spo-

ken Russian of his day with the traditional ornate

and formal rhetorical style. Perhaps Avvakum’s

best-known work is his autobiographical Life.

Three versions were written between 1672 and

1676. Of the two later versions, the copies written

by Avvakum himself, along with numerous oth-

ers, are preserved. Building on traditional genres

such as hagiography, sermons, chronicles, folk-

tales, and others, Avvakum created not only a new

genre, but a new mentality that, according to some

scholars, manifests the seeds of modern individual

self-consciousness.

See also: NIKON, PATRIARCH; OLD BELIEVERS; ORTHO-

DOXY; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avvakum Petrovich. (1979). Archpriest Avvakum: The Life

Written by Himself, with the Study of V. V. Vinogradov,

tr. Kenneth N. Brostrom (Michigan Slavic Publica-

tions). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Lupinin, Nickolas. (1984). Religious revolt in the Eighteenth

century: The Schism of the Russian Church. Princeton,

NJ: Kingston Press.

AVVAKUM PETROVICH

105

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Michels, Georg B. (1999). At War with the Church: Reli-

gious Dissent in Seventeenth-Century Russia. Stanford,

CA: Stanford University Press.

Zenkovski, S. A. (1956). “The Old Believer Avvakum: His

Role in Russian Literature,” Indiana Slavic Studies,

5:1–51.

Ziolkowski, Margaret, comp., tr. (2000). Tale of Boiary-

nia Morozova: A Seventeenth-Century Religious Life.

Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

C

ATHY

J. P

OTTER

AZERBAIJAN AND AZERIS

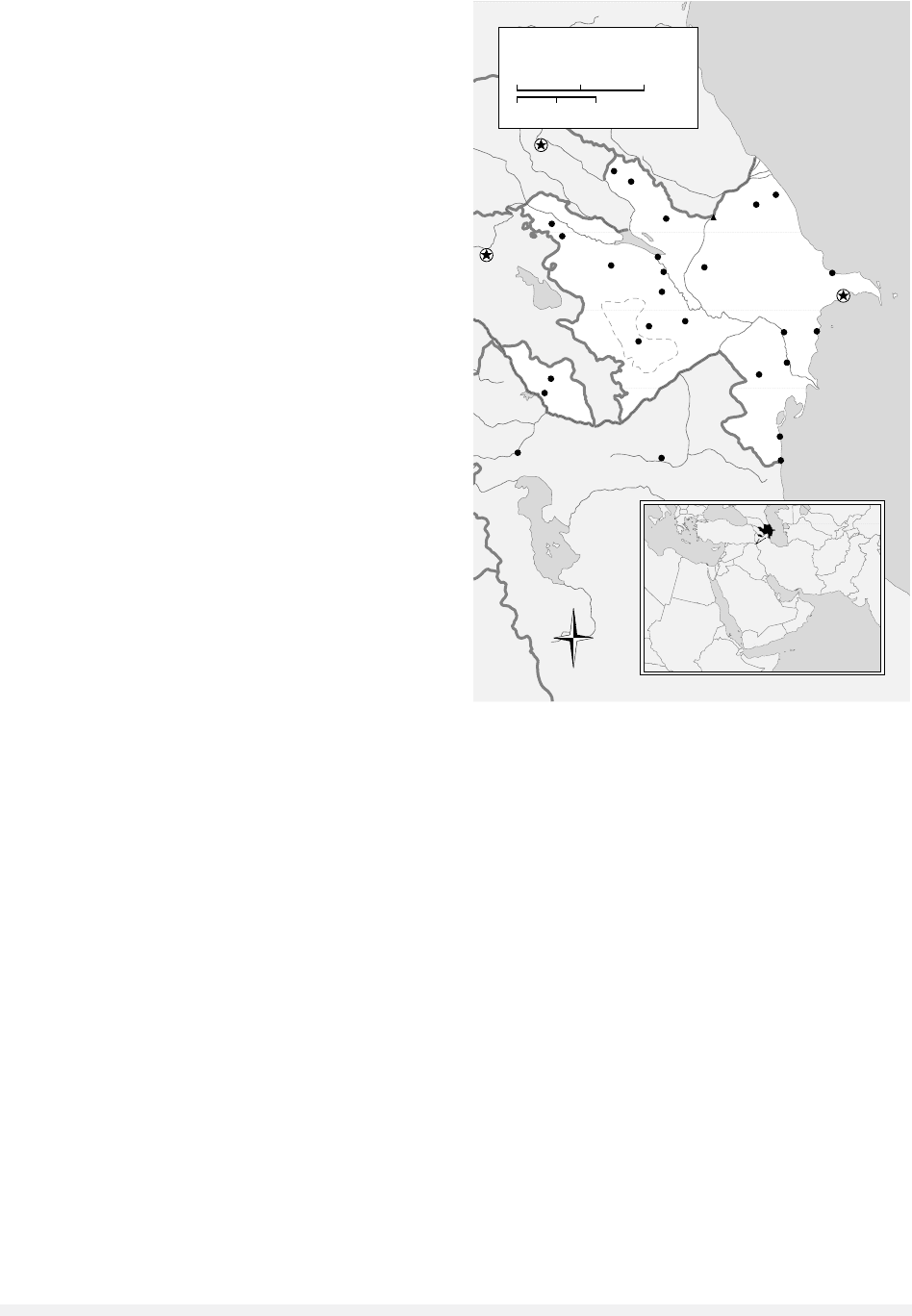

The Republic of Azerbaijan is a country located in

the Caucasus region of west Asia. Azerbaijan has a

total area of 86,600 square kilometers and shares

borders with the Russian Federation in the north

(284 kilometers), Georgia to the northwest (322

kilometers), Armenia on the west (566 kilometers),

Iran to the south (432 kilometers), and the Caspian

Sea on the east (800 kilometers). Geographically,

Azerbaijan is considered part of the Middle East.

However, it is a border country and not part of the

heartland. This borderland quality has had a pro-

found impact on the country’s history.

From the time of ancient Media (eighth to sev-

enth century

B

.

C

.

E

.) and the Achaemenid (Persian)

period, Azerbaijan has mainly shared its history

with Iran. In 300

B

.

C

.

E

., Alexander the Great con-

quered the Achaemenid Kingdom, retaining Persian

satraps to govern as his forces advanced eastward.

According to one account, the name Azerbaijan is

derived from the name of Alexander’s original

satrap, Atropatanes. Another explanation traces the

origin of the name to the Persian word for fire keep-

ers, “Azerbaycan.” This is in reference to the fires

burning in local Zoroastrian temples, fed by abun-

dant sources of crude oil.

Azerbaijan maintained its Iranian character

even after its subjugation by the Arabs in the mid-

seventh century and the conversion to Islam. Dur-

ing the eleventh century, the migrations of Oghuz

tribes under the Seljuk Turks settled into the re-

gion. These Turkic-speaking newcomers merged

with the original population so that over time, the

Persian language was supplanted by a Turkic di-

alect that eventually developed into a distinct

Azeri–Turkish language.

Under Shah Ismail (1501–1524), first among

the Safavid line of rule, the Shiasect of Islam be-

came the “official and compulsory religion of the

state ”(Cleveland, p. 58), and remains the majority

faith in Azerbaijan in the early twenty-first cen-

tury. When the two hundred-year Safavid Dynasty

ended in 1722, indigenous tribal chieftains filled the

void. Their independent territories took the form of

khanates (principalities). The tribal nature of these

khanates brought political fragmentation and even-

tually facilitated conquest by Russia. Russia’s in-

terest in the region was primarily driven by the

strategic value of the Caucasian isthmus. Russian

military activities have been recorded as early as

Peter the Great’s abortive Persian expedition to se-

cure a route to the Indian Ocean (1722). However,

penetrations into Persian territory were more suc-

cessful under Catherine II (1763–1796).

Russo-Iranian warfare continued into the nine-

teenth century, ending with the Treaty of Turk-

manchai (February 10, 1828). As a result,

Azerbaijan was split along the Araxes (Aras) River

with the majority of the population remaining in

Iran. This frontier across Iran was laid for strate-

gic purposes, providing Russia with a military av-

enue of approach into Iran while outflanking rival

Ottoman Turkey.

The Turkmanchai settlement also had far-

reaching economic consequences. With Russia as

the established hegemon, exploitation of Azerbai-

jan’s substantial petroleum resources increased

rapidly after 1859.

Over time, haphazard drilling and extraction

led to a decline in oil production. By 1905 Azer-

baijan ceased to be a major supplier to world en-

ergy markets. In 1918, with the great powers

preoccupied by World War I and Russia in the

throes of revolution, Azerbaijan proclaimed its in-

dependence on May 28, 1918. However, the inde-

pendent Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan lasted

only two years before Bolshevik forces invaded and

overthrew the nascent government.

With its new status as a Soviet republic, Azer-

baijan experienced the same transition as other

parts of the Soviet Union that included an indus-

trialization process focused on the needs of the

state, collectivization of agriculture, political re-

pression, and the Great Purges.

During World War II, Azerbaijan’s strategic

importance was again underscored when the Trans-

caucasian isthmus became an objective of Nazi

Germany’s offensive. Hitler hoped to cut Allied sup-

ply lines from their sources in the Persian Gulf.

AZERBAIJAN AND AZERIS

106

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Azerbaijan was also coveted as a valuable fuel

source for the German military. This operation was

thwarted by the battle of Stalingrad.

Azerbaijan was also the scene of an early Cold

War confrontation. On March 4, 1946, Soviet Army

brigades deployed into Azerbaijan. The United States

perceived this provocation as the first step in a So-

viet strategy to penetrate the Middle East. In the

face of shrewd Iranian diplomacy backed by West-

ern resolve, the Soviet forces withdrew, averting an

international crisis.

The limitations of the Soviet command econ-

omy coupled with the Western strategy of con-

tainment contributed to political and economic

stagnation, especially in the last decades of the So-

viet regime. A rekindled nationalism ignited by an

outbreak of ethnic violence occurred in 1988 when

neighboring Armenia voiced its claim to the district

of Karabakh. As violence escalated, a national emer-

gency ensued and new political groups, such as the

People’s Front of Azerbaijan emerged to challenge

the predominant Communist Party of Azerbaijan

(CPAz) upon the dissolution of the USSR. On Au-

gust 30, 1991, Azerbaijan, once again became an

independent republic.

However, the early years of independence were

marred by political instability, exacerbated by the

ongoing Karabakh conflict. The hostilities con-

tributed to the fall of several administrations in the

fledgling government with a favorable solution to

the conflict taking precedence over the achievement

of key political and economic reforms. On October

3, 1993, Heidar Aliyev, a former Communist Party

secretary, filled the power vacuum. Signing a ten-

tative cease-fire agreement with Armenia over the

Karabakh conflict allowed him to concentrate re-

form efforts in Azerbaijan’s government and econ-

omy.

In the early twenty-first century, the Republic

of Azerbaijan is a secular democracy with a gov-

ernment based on a separation of powers among

its three branches. The executive power is vested

with the president, who serves as head of state,

bearing ultimate responsibilities for domestic and

foreign matters. The president of the republic also

serves as the commander in chief of the armed

forces and is elected for a term of five years with

the provision to serve a maximum of two consec-

utive terms. The legislative power is executed by

the National Parliament (Milli Majlis), a unicam-

eral body consisting of 125 members. The Parlia-

ment holds two regular sessions—the spring ses-

sion (February 10–May 31) and the fall session

(September 30–December 30).

The judicial branch includes a Supreme Court,

an economic court, and a constitutional court. The

president, subject to approval by the parliament,

nominates the judges in these three courts.

Azerbaijan’s economy has been slow to emerge

from its Soviet era structuring and decay. The CIA

World Fact Book (2002) indicates that the agricul-

tural sector employs the largest segment of the

working population at 41 percent. Recognizing the

significance of the petroleum industry in stimulat-

ing the economy, the Azerbaijani government has

promoted investment from abroad to modernize its

deteriorated energy sector. A main export pipeline

AZERBAIJAN AND AZERIS

107

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Mt. Bazar Dyuzi

14,652 ft.

4466 m.

K

U

R

A

L

O

W

L

A

N

D

S

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

T

S

.

T

A

L

I

S

H

M

T

S

.

S

E

R

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

T

S

.

Caspian

Sea

A

r

a

s

K

u

r

a

K

u

r

a

Mingachevir

Reservoir

Sevana

Lich

Gyanja

(Kirovabad)

Yerevan

T'Bilisi

Mingachevir

Sumqayyt

Nakhichevan

Balakän

Zakataly

Khachmaz

Quba

Shäki

Akstafa

Tovuz

Yevlakh

Göychay

Alyat

Bärdä

Ahar

Khvoy

Agdam

Aghjabädi

Pushkin

Ali Bayramly

Salyan

Shakhbus

Länkäran

Astara

Stepanakert

Baku

GEORGIA

IRAN

RUSSIA

ARMENIA

Azerbaijan

W

S

N

E

AZERBAIJAN

100 Miles

0

0

100 Kilometers

50

50

Nagorno-

Karabakh

Apsheron

Peninsula

Azerbaijan, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH

PERMISSION

from the capital, Baku, to the Turkish port of Cey-

han will facilitate transport of oil to Western mar-

kets.

See also: ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS; ISLAM; NATIONALI-

TIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alstadt, Audrey. (1992) The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and

Identity under Russian Rule. Stanford, CA: Hoover In-

stitution Press.

CIA. (2002). The World Factbook—Azerbaijan. <www.cia

.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/aj.html>.

Cleveland, William L. (1999). A History of the Modern

Middle East. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Swietockhowski, Tadeusz. (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan:

A Borderland in Transition. NY: Columbia University

Press.

G

REGORY

T

WYMAN

AZERBAIJAN AND AZERIS

108

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BABEL, ISAAC EMMANUYELOVICH

(1894–1940), regarded as one of the finest writers

of fiction of the twentieth century.

Babel was born to a middle-class Jewish fam-

ily in Odessa. Though nonobservant, he remained

interested in Jewish culture—he translated Shalom

Aleichem—and Jewish identity became a central in-

terest of his art. Odessa was a vibrant port city,

without a heritage of serfdom, more cosmopolitan

than was the custom in Russia. Babel saw it as

fertile ground for a southern school of Russian

literature—sunny, muscular, centered on sensuous

experience, free of the metaphysical yearnings and

somber seriousness of the Russian tradition. French

literature attracted him. He had a Flaubertian ded-

ication to his craft; Maupassant’s skill in depicting

the surface of things was a model. Babel’s playful

side is most evident in his first cycle of short sto-

ries, The Odessa Tales (1921–1924). But an age of

war, revolution, and terror demanded sterner stuff.

Babel responded with his tragic Red Cavalry

(1923–1925) and his study of the complexities

of growing up Jewish, The Story of My Dovecot

(1925–1931).

Babel was sympathetic to the aims of the Russ-

ian Revolution and served it in several capacities,

including a stint as translator for the secret police

(Cheka). For a long time he enjoyed the benefits and

celebrity of a Soviet writer, though he eventually

became a victim of Soviet terror. In 1920 he signed

on as correspondent with the First Cavalry Army,

a leading unit of the Reds in the civil war, at the

time engaged in battle with Poland. His summer

with this largely Cossack army gave him the ma-

terial for his great book of revolution and war.

Success brought pressures to conform. With

the ascendancy of Josef Stalin and the mobilization

of society commencing with the First Five-Year

Plan (1928–1932), writers could no longer feel safe

pursuing their private visions as long as they

avoided criticism of communist rule. They were

now expected to produce work useful to the state.

Babel made abortive attempts to conform but

mostly sought the safety of seclusion and silence.

As he said at the First Congress of Soviet Writers:

“I have so much respect for [the reader] that I am

struck dumb.” Nevertheless, he produced some out-

standing work in the thirties, including “Guy

de Maupassant” (1932) and “Di Grasso” (1937)—

two parables of the life of the artist. He was ar-

rested as a spy on May 15, 1939. Like millions of

B

109

innocent men and women, he fell victim to Soviet

tyranny; he was shot on January 27 of the fol-

lowing year.

Babel wrote many fine stories and several in-

teresting plays. Among his best work are his cy-

cles. The Odessa Tales treat a crew of Damon

Runyon–like gangsters and their cohorts of the

Jewish ghetto of Moldavanka. They are not clothed

in realism’s ordinary dress but in the colorful gar-

ments of romance or the crazy garb of comedy.

The stories are designed to charm, not move the

reader, though their rejection of Jewish resignation

to suffering is a common theme for Babel. The four

tales comprising The Story of My Dovecot have

greater depth. They tell of the breaking away of a

Jewish boy from his highly pressured home—the

father is compensating for the indignities wrought

by anti-Semitism. Red Cavalry is a masterpiece. It

weaves its complex ways between irreconcilable an-

tagonisms—of constancy and change, action and

culture, revolution and tradition—to offer an im-

age of the tragic character of human life.

See also: PURGES, THE GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carden, Patricia. (1972). The Art of Isaac Babel. Ithaca,

NY: Cornell University Press.

Ehre, Milton. (1986). Isaac Babel. Boston: Twayne.

Poggioli, Renato. (1957). “Isaac Babel in Retrospect.” In

The Phoenix and the Spider. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Trilling, Lionel. (1955). Introduction to The Collected Sto-

ries, by Isaac Babel. New York: New American Li-

brary.

M

ILTON

E

HRE

BABI BUNTY

A set of actions used by peasant women to resist

collectivization between 1928 and 1932.

It derives from the words baba, a pejorative

term describing uncultured peasant women, and

bunt, a spontaneous demonstration or protest. Babi

bunty encompassed a range of actions intended to

disrupt collectivization, including interrupting vil-

lage meetings, harassing Soviet officials, and re-

claiming seed, livestock, or household goods that

previously had been seized by the collective farm.

These actions were among the more effective means

used by the peasants to oppose state policy, and

sometimes led to the temporary dissolution of

newly formed collective farms. Their frequent use

in the winter of 1929–1930 likely played a role in

the party leadership’s decision to slow the pace of

collectivization in March 1930.

The gendered aspect of babi bunty was very

important. The Bolsheviks considered peasant

women to be an especially backward social group,

one incapable of organized political action. They be-

lieved that babi bunty were incited by kulaks and

other anti-Soviet elements, who were manipulat-

ing the women. Because of this belief, the Bolshe-

viks responded with propaganda instead of force.

Peasant men who resisted Soviet policies during this

period, on the other hand, were treated with great

violence. The peasants’ recognition that partici-

pants in babi bunty would be treated leniently

made these actions a favored form of resistance to

collectivization. Although babi bunty only slowed

the collectivization process, their frequency likely

played a role in the state’s decision eventually to

grant peasants some concessions, such as the right

for each family to retain one cow.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICUL-

TURE; KULAKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Viola, Lynne. (1992). “Bab’i bunty and Peasant Women’s

Protest during Collectivization.” In Russian Peasant

Women, eds. Beatrice Farnsworth and Lynne Viola.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Viola, Lynne. (1996). Peasant Rebels Under Stalin: Collec-

tivization and the Culture of Peasant Resistance. Ox-

ford: Oxford University Press.

B

RIAN

K

ASSOF

BABI YAR MASSACRE See WORLD WAR II.

BAIKAL-AMUR MAGISTRAL RAILWAY

Traversing eastern Siberia and the Russian Far East,

the Baikal-Amur Magistral Railway (BAM) runs

north of and parallel to the Trans-Siberian Railway.

The “BAM Zone,” the term used to describe the ter-

ritory crossed by the railroad, includes regions

within the watersheds of Lake Baikal and the Amur

River, the latter of which forms a major part of the

Russian border with China. An area crisscrossed by

BABI BUNTY

110

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

a number of formidable rivers, the BAM Zone pre-

sented seismic, climatic, and epidemiological chal-

lenges to builders from the 1930s until the early

1990s.

The Soviet government conceived of BAM as a

second railway link (the Trans-Siberian Railway be-

ing the first) to the Pacific Ocean that would im-

prove transportation and communications between

the European and Asian sectors of the USSR. The

initial BAM project was built from Komsomolsk on

the Amur River to Sovetskaya (now known as Im-

peratorskaya) Gavan on the Pacific coast by labor

camp and prisoner-of-war labor from 1932 to

1941 and again from 1945 to 1953, when it was

abandoned in March of that year after Stalin’s death.

In March 1974, Soviet General Secretary Leonid

Brezhnev proclaimed that the construction of a new

and much longer BAM project would fall to the

Young Communist League, known as the Komso-

mol. In Brezhnev’s mind, experience on what the

state heralded as the “Path to the Future” would

instill a sense of inclusion among the Soviet Union’s

younger generations. In addition, the USSR under-

took the new BAM to bolster Soviet trade with the

dynamic economies of East Asia and to secure an

alternative route between the nation’s European

and Asian sectors in the event that the Trans-

Siberian Railway was seized by China. At its height,

BAM involved more than 500,000 Komsomol

members who severely damaged the ecology of the

BAM Zone while expending some 15 to 20 billion

dollars in a highly wasteful and inefficient endeavor

that reinforced the inadequacies of Soviet-style

state socialism among BAM’s young constructors.

In October 1984, a golden spike was hammered

into place in a ceremony that marked the official

completion of the “Project of the Century.” In re-

ality, however, only one-third of BAM’s 2,305-

mile-long track was fully operational by the early

1990s, although the railroad was declared complete

in 1991. BAM remains one of the Russian Federa-

tion’s least profitable railways.

See also: COMMUNIST YOUTH ORGANIZATIONS; RAIL-

WAYS; TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Asia Trade Hub. (2001). “Russia Watch.” <http://www

.asiatradehub.com/russia/railway.asp>.

Josephson, Paul R. (1992). “Science and Technology as

Panacea in Gorbachev’s Russia.” In Technology, Cul-

ture, and Development: The Experience of the Soviet

Model, ed. James P. Scanlan. Armonk, NY: M. E.

Sharpe.

Mote, Victor L. (1977). “The Baykal-Amur Mainline.” In

Gateway to Siberian Resources (The BAM), ed. Theodore

Shabad and Victor L. Mote. New York: Scripta.

C

HRISTOPHER

J. W

ARD

BAKATIN, VADIM VIKTOROVICH

(b. 1937), Russian and Soviet political and Commu-

nist Party figure, Soviet Minister of Internal Affairs,

1988–1990; last chairman of KGB, 1991; first chair-

man of Inter-Republic Security Service from 1991.

Vadim Bakatin was born in Kemerovo Oblast.

Educated at the Novosibirsk Construction Engi-

neering Institute, he worked as an engineer in con-

struction in Kemerovo from the early 1960s until

the early 1970s. He joined the Communist Party in

1964 and in the mid-1970s served as a local party

official, rising to the position of Secretary of the

Kemerovo Oblast Committee in 1977. Bakatin at-

tended the High Party School and in 1985 joined

the Inspectorate of the Central Committee of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). In

1986 he served on the Central Committee. After

brief service as First Secretary of the Kemerovo

Oblast Committee, Bakatin was appointed Minister

of Internal Affairs in 1988, and he served in that

post until 1990. In 1991 he was an unsuccessful

candidate for the presidency of Russia, warning

about the dangers of overly rapid reform. Cam-

paigning in May 1991 he stated that “Making cap-

italism out of socialism is like making eggs out of

an omelette.” Bakatin opposed the August 1991

coup attempt and then was appointed director of

the KGB. He undertook the purge of the KGB senior

leadership that had supported Vladimir Kryuchkov,

the former director and coup plotter. With the col-

lapse of Soviet power in the fall of 1991, Bakatin

oversaw the breakup of the KGB and then briefly

served as the first chairman of the Inter-Republic

Security Service. In 1992 he published a personal

memoir of his role in the break-up of the KGB un-

der the title, Izbavlenie ot KGB: Vremya - sobytiya -

lyudi (Deliverance from the KGB: The time, the

events, the people). Later he went into business and

became the director of the Baring Vostok Capital

Partners, a direct investment company. He re-

mained loyal to Mikhail Gorbachev and has spo-

ken favorably of his efforts at reform.

See also: STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

BAKATIN, VADIM VIKTOROVICH

111

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gevorkian, Natalia. (1993). “The KGB: ‘They Still Need

Us’.” The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists 49(1):36–38.

Knight, Amy. (1996). Spies without Cloaks: The KGB’s Suc-

cessors. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Waller, J. Michael, and Yasmann, Viktor J. (1995). “Rus-

sia’s Great Criminal Revolution: The Role of the Se-

curity Services,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal

Justice 11(4): 276–297.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

BAKHTIN, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH

(1895–1975), considered to be Russia’s greatest lit-

erary theoreticians, whose work has had an im-

portant influence, in Russia and abroad, on several

other fields in the social sciences and humanities.

Born in Orel into a cultured bourgeois family,

Bakhtin earned a degree in classics and philology.

During the Civil War, he moved to Nevel, where

he worked as a schoolteacher and participated in

study circles, and later moved to Vitebsk. In 1924

Bakhtin and his wife moved back to Leningrad, but

he found it difficult to obtain steady employment.

He was arrested in 1929 and charged with partic-

ipation in the underground Russian church, but

managed nevertheless to live most of the 1930s and

1940s in productive obscurity, publishing regu-

larly. He and his work were rediscovered during

the 1950s, and over the years his writings have

continued to influence the development of philol-

ogy, linguistics, sociology, and social anthropol-

ogy, to name just a few related disciplines.

Many of Bakhtin’s contemporary systematiz-

ers of Russian thought sought to discover laws of

society or history and to formulate models designed

to explain everything. Bakhtin, however, sought to

show that there could be no such comprehensive

system. In this sense he set himself against the main

currents of European social thought since the sev-

enteenth century, and especially against the tradi-

tional Russian intelligentsia. Drawing upon literary

sources, he tried to create pictures of self and soci-

ety that contained, as an intrinsic element, what

he called surprisingness. In his view, no matter how

much one knows of a person, one does not know

everything and cannot unfailingly predict the fu-

ture (even in theory). Instead, he argued, there is

always a surplus of humanness, and this is what

makes each person unique. Like Fyodor Dostoyevsky,

Leo Tolstoy before 1880, and Anton Chekhov,

Bakhtin belongs to the great anti-tradition of Rus-

sian thought that, unlike the dominant groups of

the intelligentsia, denied that any system could ex-

plain, much less redeem, reality.

In his earliest work, Bakhtin developed various

models of self and the other, and attempted to de-

velop an approach to ethics. He believed that ethics

could not be a matter of applying abstract rules to

particular situations, but comes instead from care-

ful observation and direct participation in ulti-

mately unrepeatable circumstances. He argued that

through a reliance on rules and ideology, rather

than really engaging oneself with a given situation,

one is using an alibi and, thus, abdicating respon-

sibility. He countered this approach by saying that,

in life, there is no alibi.

As an enemy of all comprehensive theories,

Bakhtin opposed formalism and structuralism, al-

though he learned a good deal from them. Basi-

cally, he accepted the usefulness of certain formal

approaches and methods employed by these theo-

retical schools, but insisted that human purpose-

fulness and intentionality lay behind these formal

models. Unlike the formalists and structuralists, he

developed a theory of language and the psyche that

was based on the concrete utterance (what people

actually say), and on open-ended dialogue. This lat-

ter is perhaps the most famous of the concepts he

introduced.

Bakhtin developed a theory of polyphony,

which he elaborated in his book on Dostoyevsky

(1929). With this theory, he tries to show how an

author deliberately creates without knowing what

his or her characters will do next, and, in so do-

ing, the author also creates a palpable image of true

freedom. Bakhtin equated that freedom to that

which is enjoyed by God, who did not foresee the

outcome of the creatures made by God. In taking

this stance, he argued against the determinists or

predestinarians, for he believed that people are truly

free and ever-surprising, if they are as the poly-

phonic novel represents them.

Bakhtin’s work on the novel during the 1930s

and 1940s is justly renowned. It is certainly his

most durable contribution to semiotics. He identi-

fies how novelistic language works; how the self

and plot are tied to concepts of time and becom-

ing; and how elements of a parodic (or carnivalis-

tic) spirit have infused the novel’s essence. This

theory, as well as in theories of culture that he de-

veloped during the 1950s, emphasized dialogue,

BAKHTIN, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH

112

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY