Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

temporal openness, surprisingness, the uniqueness

selfhood, and fundamental principles of ethical re-

sponsibility.

See also: CHEKHOV, ANTON PAVLOVICH; DOSTOYEVSKY,

FYODOR MIKHAILOVICH; TOLSTOY, LEO NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bakhtin, Mikhail. (1968). Rabelais and His World, tr.

Hélène Iswolsky. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. (1981). The Dialogic Imagination: Four

Essays by M.M. Bakhtin, ed. Michael Holquist, tr.

Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: Uni-

versity of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. (1984). Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poet-

ics, ed. and tr. Caryl Emerson. Minneapolis: Univer-

sity of Minnesota Press.

Clark, Katerina, and Holquist, Michael. (1984). Mikhail

Bakhtin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Morson, Gary Saul, and Emerson, Caryl. (1990). Mikhail

Bakhtin: Creation of a Prosaics. Stanford: Stanford

University Press.

G

ARY

S

AUL

M

ORSON

BAKU

Baku is the capital of Azerbaijan and a major port

on the Caspian Sea. The city was first taken by Pe-

ter I in the 1710s and held for two decades. The

entire region of Caucasia was conquered by Russ-

ian forces in a war against Iran in the 1800s and

confirmed by the 1813 Treaty of Gulistan.

Baku has meant two things to Russia: oil and

strikes. The former has had the more enduring sig-

nificance. The Baku oil fields were the object of

Russian desire since the occupation by Peter I. Sig-

nificant output began only with drilling in the

1870s. The oil rush of the last third of the nine-

teenth century brought thousands of Russian peas-

ants to the Baku region to work in the oil fields.

By the imperial census of 1897, the Russians were

nearly as numerous as the native Azerbaijani Turks

(approximately 37,400 to 40,000). By the 1903

city census, the Russians outnumbered them

(57,000 to 44,000). Other national groups came to

Baku. Armenians were a small but economically

powerful minority with long-established commu-

nities, mostly involved in trade. Iranian Azerbaija-

nis crossed the border in large numbers. They were

part of the same ethnic and religious group, speak-

ing the same language as did the local residents.

There were also communities of Georgians, Jews,

Germans, and peoples from the Caucasus Moun-

tains. Europeans arrived as investors, engineers,

and skilled technicians. By 1900, Baku had a tele-

phone system, European-style buildings, and an ac-

tive City Council (Duma). It had a relatively high

crime rate and a reputation akin to that of the Wild

West in North America.

In the dangerous conditions of the oil fields, a

labor movement emerged around the turn of the

century. The Russian Social Democrats regarded

Baku’s activity as an alarm bell for the strike move-

ment across the southern part of the empire. Baku

provided a training ground for such future lumi-

naries as Grigory Ordzhonikidze and Josef Stalin.

For a time under Menshevik leadership, the Baku

Committee of the party permitted the formation of

a special party only for the Muslim workers, the

Hummet. Class solidarity usually broke down

along national lines, however, and the violence oc-

casionally led to arson in the oil fields. In 1918 a

Bolshevik-led government, known as the Baku

Commune, ran the city briefly before the city fell

to the invading Turkish army. Baku was the cap-

ital of the independent Republic of Azerbaijan

(1918–1920) and, from April 1920 to 1991, of the

Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan.

Although Baku’s oil was largely depleted by the

1920s, the city was a target of Nazi advances in

World War II. The Soviet Gosplan invested very lit-

tle in the oil industry in Baku after the war and

left its infrastructure to languish.

In the post-Soviet period, offshore drilling has

taken the place of the old wells as a prize for for-

eign investors. Russia has tried, again, to maintain

access to the oil and has fought proposals by Azer-

baijan and foreign oil companies that seek to route

the oil around Russian pipelines and Black Sea

ports.

See also: AZERBAIJAN AND AZERIS; CAUCASUS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Altstadt, Audrey. (1986). “Baku: Transformation of a

Muslim Town.” In The City in Late Imperial Russia,

ed. Michael F. Hamm. Bloomington: Indiana Uni-

versity Press.

A

UDREY

A

LTSTADT

BAKU

113

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BAKUNIN, MIKHAIL ALEXANDROVICH

(1814–1876), world-famous revolutionary and

one of the founders of Russian anarchism and rev-

olutionary populism.

Although born into a nobleman’s family,

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was hostile toward

the tsarist system and the traditional socioeconomic

and political order. An extreme materialist, he was

bitterly antireligious and saw organized religion as

oppressing people.

Despite his revolutionary passion, Bakunin, as

a contemporary Western philosophical encyclope-

dia puts it, “was learned, intelligent, and philo-

sophically reflective.” By contrast, a Soviet-period

philosophical dictionary describes Bakunin as a

“revolutionary-adventurer [who] blindly believed

in the socialist instincts of the masses and in the

inexhaustibility of their spontaneous revolutionary

feeling, especially as found among the peasantry

and lumpen-proletariat.”

The “reign of freedom,” Bakunin insisted,

could come for the masses and for everyone only

after the liquidation of the status quo of traditional

bourgeois society and the state. Bakunin soon fell

out with the Marxists, with whom he had origi-

nally been tenuously allied in the First International

in Geneva. He denounced the Marxist teaching of

the necessity of a dictatorship of the proletariat in

order to usher in the new order of socialism. He

also disagreed with those Russian revolutionists

who advocated terrorism and various forms of

postrevolutionary authoritarianism and dictator-

ship, such as the Russian Jacobins. “Every act of

official authority,” Bakunin once wrote, “necessar-

ily awakens within the masses a rebellious feeling,

a legitimate counterreaction.”

In a letter to the 1860s revolutionary terrorist

Sergei Geradievich Nechayev, Bakunin once wrote:

“You said that all men should follow your revolu-

tionary catechism, that the abandonment of self and

renunciation of personal needs and desires, all feel-

ings, all attachments and links should become a

normal state of affairs, the everyday condition of

all humanity. Out of that cruel renunciation and

extreme fanaticism you now wish to make this a

general principle applicable to the whole commu-

nity. You want crazy things, impossible things, the

total negation of nature, man, and society!” Here

Bakunin seemed to be renouncing his own, earlier

brief leanings toward authoritarianism before

adopting his anarchist philosophy.

For Bakunin, government of any kind, like re-

ligion, is oppressive. The church, he said, is a “heav-

enly tavern in which people try to forget about

their daily grind.” In order for people to gain free-

dom, religion and the state must be swept away

along with all forms of “power over the people.”

Their place will be taken by a “free federation” of

agricultural and industrial cooperative associations

in which science reigns.

Bakunin spent much of his life abroad. He em-

igrated from Russia in 1840 to live in central and

western Europe. There he formed close ties with

other famous Russian émigrés, such as Alexander

Herzen and Nikolai Ogarev.

Bakunin’s relations with the First International

and Karl Marx were stormy. Resenting Marx’s

high-handedness and authoritarian political ideol-

ogy, Bakunin was finally expelled from the com-

munist world organization in 1870. Soon after

this, his The State and Anarchy was published in

several languages. In this work, in quasi-Hegelian

terms, he describes the historical process by which

mankind evolves from “bestiality” to freedom.

See also: ANARCHISM; HERZEN, ALEXANDER IVANOVICH;

NECHAYEV, SERGEI GERADIEVICH; POPULISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Venturi, Franco. (1966). Roots of Revolution: A History of

the Populist and Socialist Movements in Nineteenth Cen-

tury Russia, trans. Francis Haskell. New York: Gros-

set & Dunlap.

Weeks, Albert L. (1968). The First Bolshevik: A Political

Biography of Peter Tkachev. New York: New York

University Press.

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

BALAKLAVA, BATTLE OF

On October 25, 1854, Prince A. S. Menshikov, com-

mander of Russian ground forces in Crimea,

launched an attack on the British supply base at

Balaklava to divert an allied attack on Sevastopol.

The battlefield overlooked the Crimean Uplands,

which dropped steeply onto the Plain of Balaklava.

The plain was divided into two valleys by the

Causeway Heights, occupied by a series of Turkish-

held redoubts.

BAKUNIN, MIKHAIL ALEXANDROVICH

114

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The British cavalry was camped at the foot of

the escarpment. The Russians, led by Prince R. R.

Liprandi, captured four redoubts at dawn on Oc-

tober 25. Although the British Commander, Lord

Raglan, had a commanding view, he was short of

infantry. Russian hussars advancing toward Bal-

aklava were driven off by his only infantry regi-

ment. Another large Russian cavalry force was

driven off by the British Heavy Brigade, leaving the

battle stalled. When the Russians began to remove

captured guns from the redoubts, Raglan, still lack-

ing infantry reinforcements, ordered the cavalry to

stop them.

In error, the 661-strong Light Brigade under

Lord Cardigan advanced down the valley toward

the main Russian batteries. British troopers came

under fire from fifty-four cannons to the front and

on both flanks. Reaching the guns at a charge, the

brigade drove off the Russian cavalry before retir-

ing slowly back to their starting line, having suf-

fered grievous losses: 118 killed, 127 wounded, and

45 taken prisoner. This astonishing display of cool

courage demoralized the Russians. Total battle ca-

sualties included 540 Russians killed and wounded;

360 British, 38 French, and 260 Turks. It was lit-

tle more than a skirmish in the much larger war.

See also: CRIMEAN WAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adkin, Mark. (1996). The Charge. London: Leo Cooper.

Anglesey, Marquis of. (1975). A History of the British Cav-

alry. London: Leo Cooper.

Lambert, Andrew. (1990). The Crimean War: British Grand

Strategy against Russia, 1853–1856. Manchester:

Manchester University Press.

Seaton, Albert. (1977). The Crimean War: A Russian Chron-

icle. New York: St. Martin’s.

A

NDREW

L

AMBERT

BALALAIKA

The balalaika is one of a family of Eurasian mu-

sical instruments with long necks, few strings, and

a playing technique based on rapid strumming

with the index finger. First mentioned in written

records in 1688 in Moscow, the balalaika existed

in various forms with triangular and oval bodies,

differing numbers of strings, and movable tied-on

string frets, and was mainly used for playing

dance tunes.

The traditional balalaika’s popularity may have

peaked in the last decades of the eighteenth cen-

tury, when foreign travelers reported seeing one in

every home, although as numerous references in

the works of Leo Tolstoy, Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor

Dostoyevsky, and others attest, it remained in

widespread if diminishing use during the nine-

teenth century. Most closely associated with the

Russians, the instrument, likely a borrowing from

the Tatars, was used to a lesser extent by Ukraini-

ans, Gypsies, Belarussians, and other ethnic groups.

The modern balalaika originated from the work

of Vasily Andreyev (1861–1918), who in the 1880s

created a standardized, three-string chromatic

triangular-bodied instrument with fixed metal frets

and other innovations. Andreyev went on to de-

velop the concept of the balalaika orchestra con-

sisting of instruments of various sizes, for which

he later reconstructed the long-forgotten domra, a

favorite instrument of the skomorokhi, or minstrels.

The modern balalaika is a hybrid phenomenon

incorporating elements of folk, popular, and art or

classical music and is widely taught from music

school through conservatory. In addition to its use

in traditional-instrument orchestras and ensem-

bles, the balalaika’s repertoire includes pieces with

piano and other chamber works, a number of con-

certos with symphony orchestra, and occasional

appearances in opera. A vanishing contemporary

village folk tradition, while possibly preserving some

pre-Andreyev elements, utilizes mass-produced

balalaikas played with a pick. Throughout much

of its history the instrument has been used as a

symbol of Russian traditional culture.

See also: FOLK MUSIC; MUSIC

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kiszko, Martin. (1995). “The Balalaika: A Reappraisal.”

Galpin Society Journal 48:130–155.

S

ERGE

R

OGOSIN

BALKAN WARS

Following the Bosnian crisis of 1908 to 1909 and

the formal annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina by

Austria-Hungary, Russia abandoned its policy of

reaching a modus vivendi with Vienna on the Balkans.

Weakened by the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 to

1905 and the Revolution of 1905, it now sought a

BALKAN WARS

115

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

defensive alliance with Serbia and Bulgaria as a way

to regain influence in the region. Although the

diplomatic discussions that ensued were not in-

tended to further the already fractious nature of

Balkan rivalries, events soon ran counter to Rus-

sia’s intentions.

The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 had

sought to revitalize the Ottoman Empire but in-

stead hastened its dismemberment. In 1911 the Ital-

ian annexation of Tripoli laid bare the weakness of

the Turks, and the remaining Ottoman holdings in

Europe suddenly became inviting targets for the

states in the region. With Russian encouragement,

Serbia and Bulgaria joined in a pact in March 1912,

the genesis of a new Balkan League. Two months

later Albania revolted and called upon Europe for

support. That same month, May 1912, Bulgaria

and Greece entered into an alliance, and in October,

Montenegro joined the partnership.

What Russian foreign minister Sergei Sazonov

saw as an alliance to counter Austro-Hungarian in-

fluence in the Balkans was now a league bent upon

war. The March pact between Serbia and Bulgaria

had already presaged the conflict by calling for the

partition of Macedonia. Reports of impending war

in the Balkans during the summer and fall of 1912,

and also of a belief that Russia would come to the

aid of its Slavic brethren, led Sazonov to inform

Sofia and Belgrade that theirs was a defensive al-

liance. Nonetheless, by autumn public sentiment in

southeastern Europe left the Balkan allies little

choice.

On October 8, 1912, Montenegro attacked

Turkey. On October 17 Serbia and Bulgaria joined

the conflict, followed two days later by Greece. The

Balkan armies quickly defeated the Turks. Bulgar-

ian forces reached the outskirts of Istanbul, and in

May 1913 the Treaty of London brought the First

Balkan War to a close. The peace did not last long,

however, as the creation of a new Albanian state

and quarrels among the victors over the spoils in

Macedonia led to embitterment, especially on the

part of Sofia, which felt cheated out of its Mace-

donian claims.

On the night of June 29–30, 1913, one month

following the peace treaty, Bulgarian troops moved

into the north-central part of Macedonia. The other

members of the coalition, joined by Romania and,

ironically, the Turks, joined in the counterattack.

Bulgaria was quickly defeated and, by the Treaty

of Bucharest, August 10, 1913, was forced to cede

most of what it had gained in Macedonia during

the First Balkan War. In addition, the Ottoman Em-

pire regained much of eastern Thrace, which it had

lost only months earlier. Romania’s share of the

spoils was the southern Dobrudja.

Serbia was the principal victor in the Balkan

Wars, gaining the lion’s share of Macedonia as well

as Kosovo. Bulgaria was the loser. In many re-

spects, Russia lost as well because the continuing

instability in the Balkans undermined its need for

peace in the region, a situation clearly demonstrated

by the events of the summer of 1914.

See also: ALBANIANS, CAUCASIAN; BUCHAREST, TREATY

OF; BULGARIA, RELATIONS WITH; GREECE, RELATIONS

WITH; MONTENEGRO, RELATIONS WITH; SERBIA, RELA-

TIONS WITH; TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH; YUGOSLAVIA,

RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jelavich, Barbara. (1964). A Century of Russian Foreign

Policy, 1814–1914. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

BALKAN WARS

116

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

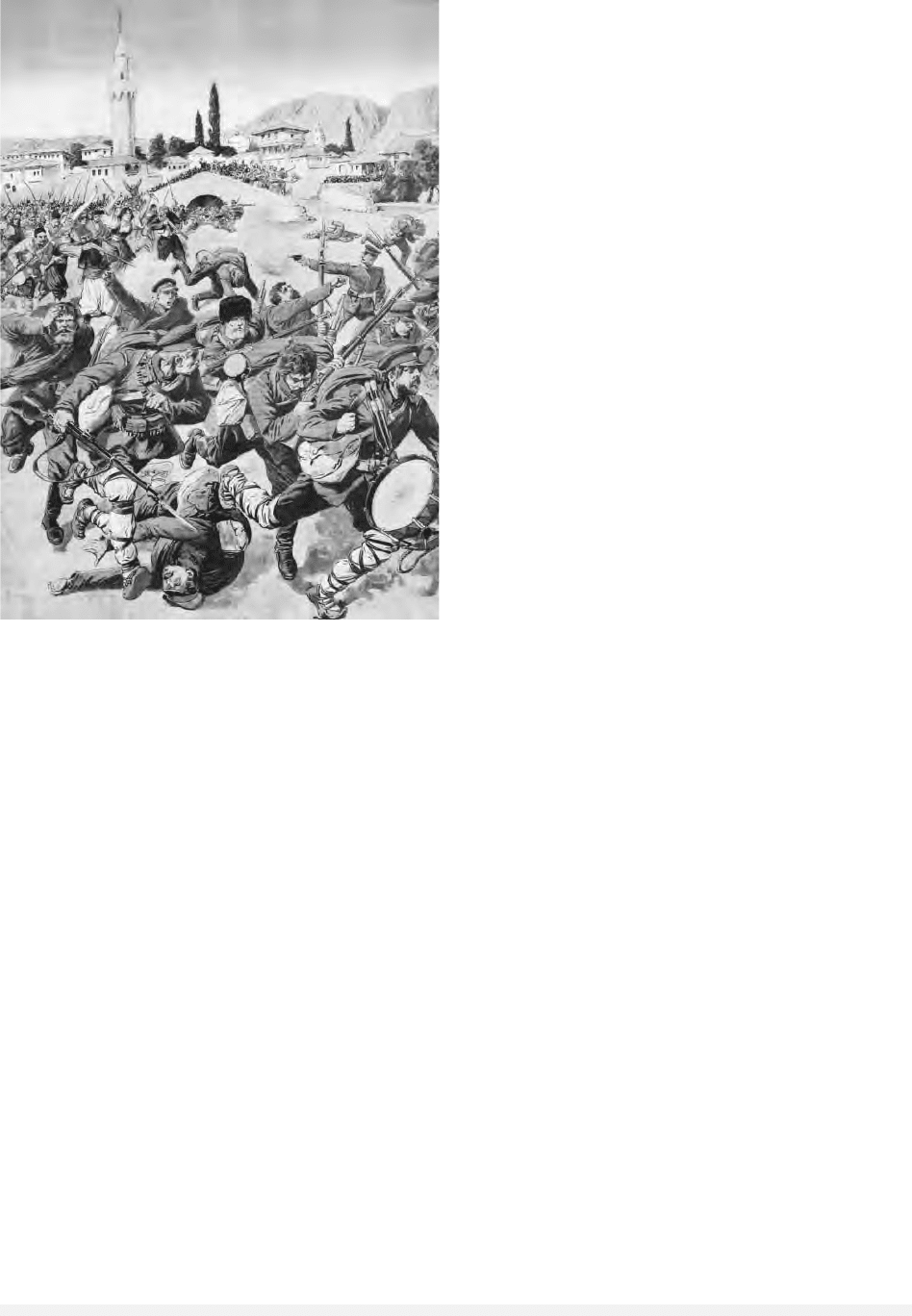

Residents of Gumurdjina, Macedonia, drive away invading

Bulgarians, c. 1913. © M

ARY

E

VANS

P

ICTURE

L

IBRARY

Rossos, Andrew. (1981). Russia and the Balkans: Inter-

Balkan Rivalry and Russian Foreign Policy, 1908–1914.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

R

ICHARD

F

RUCHT

BALKARS

The Balkars are a small ethnic group in the north-

west Caucasus. They are one of the titular nation-

alities of the autonomous Karbardino-Balkar

Republic in the Russian Federation. In the 1989 So-

viet Census, they numbered 85,126. Of that num-

ber, 93 percent considered Balkar to be their native

language, while 78 percent considered themselves

fluent in Russian as a second language. This means

that nearly all adults spoke Russian to some ex-

tent.

The Balkar language is essentially identical to

the Karachay language, spoken in the Karachay-

Cherkess Republic. This split is an example of the

way in which some languages were fractured into

smaller groups for the sake of creating smaller eth-

nic identities. The Karachay-Balkar language itself

is a member of the Ponto-Caspian group of west-

ern Turkic languages. Other languages closely re-

lated are Kumyk in Dagestan, Karaim in Lithuania,

and the Judeo-Crimean Tatar language of Uzbek-

istan.

Following the general pattern of alphabet pol-

itics in the Soviet Union, Balkar was written with

an Arabic script until 1924, from 1924 to 1937

with a Latin alphabet, and finally from 1937 to the

present in a modified Cyrillic. A modest number of

books were published in Balkar during the Soviet

period. From 1984 to 1985, for example, fifty-eight

titles were published. This is a reasonable number

in the Soviet context for the size of their group and

for sharing an ethnic jurisdiction. This number is

higher than some of the Dagestani peoples who had

larger populations, but no jurisdiction of their own.

The Balkar people, as Turks, find themselves

surrounded by Circassians and their close neigh-

bors in the northwest Caucasus. They are linguis-

tically a remnant of Turkish groups who migrated

along the Eurasian steppe. Historically, in addition

to the disruptions of the nineteenth-century Rus-

sian conquest of the Caucasus, the Balkars were

one of the peoples who suffered deportation at the

end of World War II for their alleged collaboration

with the Nazis. They were allowed to return in the

1950s, but only after experiencing a significant

diminution of their population. The alienation of

exile has been compounded by the ongoing diffi-

culty of returning to territory that had, in the

meantime, been occupied by outsiders. Post-Soviet

ethnic conflict has followed along these contours.

See also: CAUCASUS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET;

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ethnologue <www.ethnologue.com>.

Hill, Fiona. (1995). Russia’s Tinderbox: Conflict in the North

Caucasus and Its Implication for the Future of the Russ-

ian Federation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Karny, Yo’av. (2000). Highlanders: A Journey to the Cau-

casus in Quest of Memory. New York: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux.

P

AUL

C

REGO

BALLET

The origins of the Russian ballet, like those of most

other Western art forms, can be traced to eigh-

teenth-century St. Petersburg, where Empress

Anna Ivanovna established the first dancing school

in Russia in 1738. This school, whose descendant

is the present-day Academy of Russian Ballet, was

headed by a series of European dancing masters,

the first of whom was Jean-Baptiste Landé.

By the 1740s, Empress Elizabeth employed three

balletmasters. The continued presence of ballet in

Russia was assured by Catherine II, who established

a Directorate of Imperial Theaters in 1766, saw to

the construction of St. Petersburg’s Bolshoi Theater

in 1783, and incorporated Landé’s school into the

Imperial Theater School she founded in 1779.

The tenure of French balletmaster Charles-Louis

Didelot (1767–1837) in St. Petersburg (1801–1831)

marked the first flowering of the national ballet.

The syllabus of the imperial school began to as-

sume its present-day form under Didelot, and his

use of stage machinery anticipated the exploitation

of stage effects to create atmosphere and build au-

diences for the ballet across Europe in the first half

of the nineteenth century. After Didelot’s depar-

ture, Jules Perrot led the Petersburg ballet from

1848 to 1859. Arthur Saint-Léon succeeded Perrot

and choreographed in St. Petersburg until 1869.

BALLET

117

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian ballet began to assume its familiar

form during the decades of Marius Petipa’s

(1818–1910) work in the Imperial Theaters. Petipa

came to Petersburg as a dancer in 1847, and be-

came balletmaster in 1862. The ballets Petipa

choreographed in Russia functioned as a choreo-

graphic response to nineteenth-century grand

opera; they featured as many as five acts with nu-

merous scene changes. If Perrot is identified pri-

marily with the development of narrative in

Russian ballet, and Saint-Léon could be accused of

overemphasizing the ballet’s divertissement at the

expense of the story line, Petipa combined the two

trends to make a dance spectacle with plots as

complex as their choreography. The ballets Petipa

staged in St. Petersburg still serve as cornerstones

of the classical ballet repertory: Sleeping Beauty

(1890), Swan Lake (1895) (with Lev Ivanov), Ray-

monda (1898), Le Corsaire (1869), Don Quixote

(1869), and La Bayadère (1877).

The distinctive features of nineteenth-century

dance represent developments of the Russian school

of dancing under Petipa’s leadership. The new fo-

cus on the female dancer was the result of recent

developments in point technique, which allowed

the ballerina not only to rise up on the tips of her

toes, but to remain posed there, and eventually to

dance on them. Petipa’s choreography emphasizes

two nearly opposite facets of the new technique

that these technical advances afforded: first, the

long supported adagio, in which the woman is sup-

ported and turned on point by her partner; second,

the brilliant allegro variations (solos) Petipa created

for his ballerinas, to exploit the steel toes of this

new breed of female dancer.

The work of two ballet reformers characterize

the late- and post-Petipa era. Alexander Gorsky be-

came the chief choreographer of Moscow’s Bolshoi

Theater in 1899 and attempted to imbue the ballet

with greater realism along the lines of the dramas

of Konstantin Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art Theater.

Gorsky’s ballets featured greater cohesion of design

elements (sets and costumes) and an unprecedented

attention to detail. In Petersburg, Michel Fokine fell

under the spell of dancer Isadora Duncan and the-

ater director Vsevolod Meyerhold. Influenced by the

free dance of the former, and by the latter’s exper-

iments in stylized symbolist theater, Fokine pio-

neered a new type of ballet: typically a one-act

work without the perceived expressive confines of

nineteenth-century mime and standard ballet steps.

Fokine and his famed collaborators, Vaslav Ni-

jinsky and Anna Pavlova, achieved their greatest

fame in Europe as charter members of Sergei Di-

agilev’s Ballets Russes, which debuted in Paris in

1909. Fokine’s ballets (Les Sylphides, Petrushka,

Spectre de la Rose) were the sensations of the early

Diagilev season. The Diagilev ballet not only an-

nounced the Russian ballet’s arrival to the Euro-

pean avant-garde, but also the beginning of a rift

that would widen during the Soviet period: the rise

of a Russian émigré ballet community that included

many important choreographers, dancers, com-

posers, and visual artists, working outside Russia.

The 1917 revolution posed serious problems

for the former Imperial Theaters, and not least to

the ballet, which was widely perceived as the bauble

of the nation’s theater bureaucracy and former

rulers. Nonetheless, the foment that surrounded at-

tempts to revolutionize Russian theater in the years

following the October Revolution had limited im-

pact on the ballet. With most important Russian

BALLET

118

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

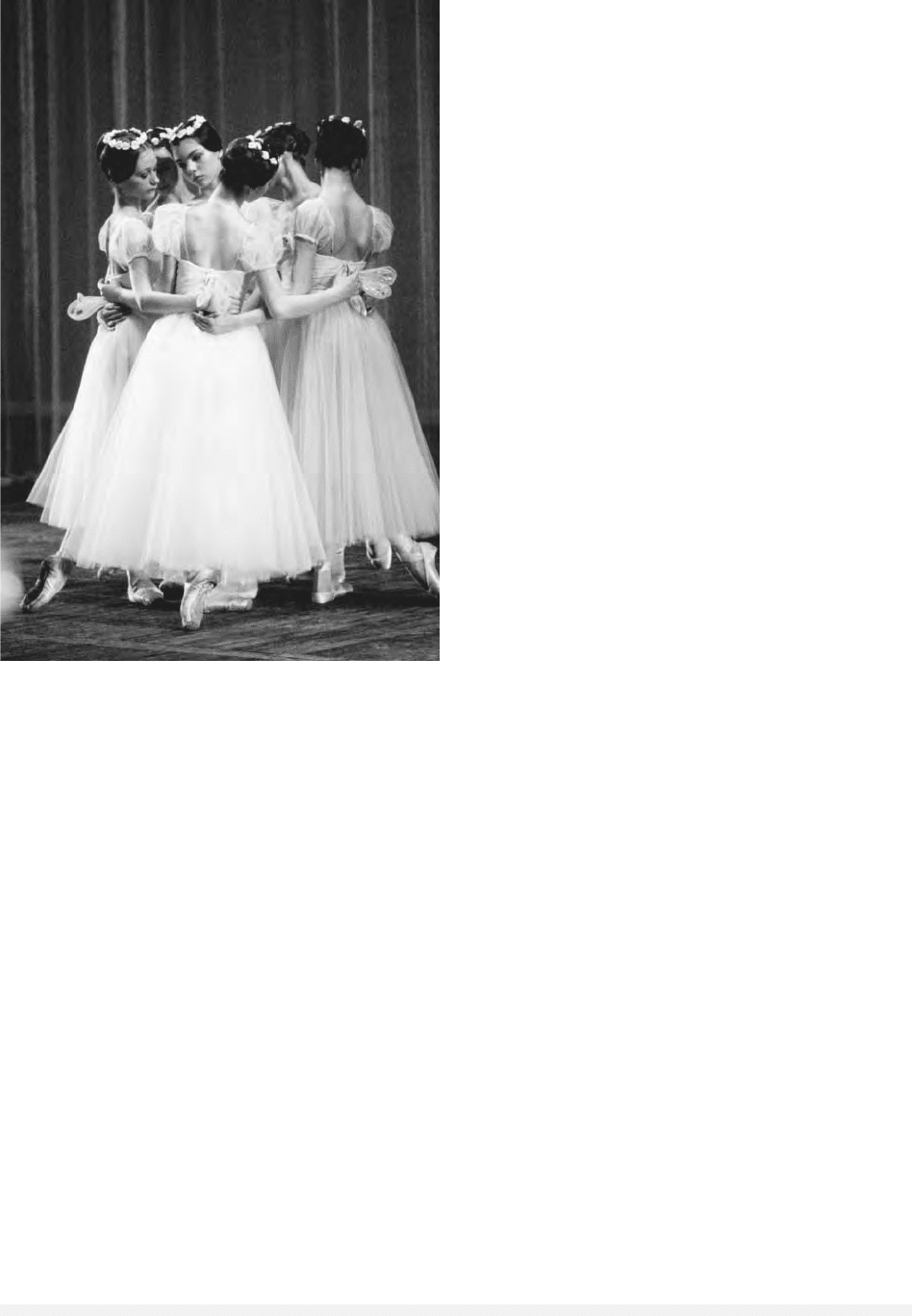

Dancers from the Kirov Ballet in St. Petersburg perform on

stage in the 1990s. © B

OB

K

RIST

/CORBIS

choreographers, dancers, and pedagogues already

working outside of Russia in the 1920s (Fokine,

George Balanchine, Vaslav Nijinsky, Bronislava Ni-

jinska, Anna Pavlova, and Tamara Karsavina, to

name a few), experimentation in the young Soviet

ballet was borne of necessity.

The October Revolution and the subsequent

shift of power, both political and cultural, to

Moscow, led to the emergence of Moscow’s Bolshoi

Ballet. The company that had long occupied a dis-

tinct second place to the Petersburg troupe now

took center stage—a position it would hold until

the breakup of the Soviet Union. The creative lead-

ership of the company had traditionally been im-

ported from Petersburg, but in the Soviet period,

so would many of its star dancers (Marina Semy-

onova, Galina Ulanova).

A new genre of realistic ballets was born in the

Soviet Union in the 1930s, and dominated Soviet

dance theater well into the 1950s. The drambalet,

shorthand for dramatic ballet, reconciled the bal-

let’s tendency to abstraction (and resulting lack of

ideological content) to the new need for easily un-

derstandable narrative. The creative impotence of

Soviet ballet in the post-Stalin era reflected the gen-

eral malaise of the so-called period of stagnation of

the Brezhnev years. When Russian companies dra-

matically increased the pace of moneymaking

Western tours in the 1980s, it became clear that

the treasure-chest of Russian classic ballets had

long ago been plundered, with little new choreog-

raphy of interest to refill it. As the history of the

two companies would suggest, the loss of Soviet

power resulted in the speedy demotion of the

Moscow troupe and the rise of a post-Soviet Pe-

tersburg ballet.

See also: BOLSHOI THEATER; DIAGILEV, SERGEI PAVL-

OVICH; NIJINSKY, VASLAV FOMICH; PAVLOVA, ANNA

MATVEYEVNA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Roslavleva, Natalia. (1956). Era of the Russian Ballet. Lon-

don: Gollancz.

Scholl, Tim. (1994). From Petipa to Balanchine: Classical

Revival and the Modernization of Ballet. London:

Routledge.

Slonimsky, Yuri. (1960). The Bolshoi Ballet: Notes.

Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Souritz, Elizabeth. (1990). Soviet Choreographers in the

1920s, tr. Lynn Visson. Durham, NC: Duke Uni-

versity Press.

Swift, Mary Grace. (1968). The Art of the Dance in the

USSR. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame

Press.

Wiley, Roland John, ed. and tr. (1990). A Century of Russ-

ian Ballet: Documents and Eyewitness Accounts, 1810-

1910. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

T

IM

S

CHOLL

BALTIC FLEET

The Baltic Fleet, which controls the Kronstadt and

Baltiysk naval bases, is headquartered in Kaliningrad

Oblast (formerly called Königsberg), a region that

once formed part of East Prussia. Today Kalin-

ingrad is a Russian enclave completely cut off from

the rest of Russia by Lithuania and Poland (now a

NATO member). Thus, although the fleet is de-

fended by a naval infantry brigade, its location is

potentially the most vulnerable of the major Russ-

ian naval fleets. While the Baltiysk naval base is lo-

cated on Kaliningrad’s Baltic Sea coast to the west,

the Kronstadt base is situated on Kotlin Island in

the Gulf of Finland, about 29 kilometers (18 miles)

northwest of St. Petersburg. The naval base occu-

pies one half of the island, which is about 12 kilo-

meters (7.5 miles) long and 2 kilometers (1.25

miles) wide. Mutinies at Kronstadt took place in

1825 and 1882 and played a part in the revolu-

tions of 1905 and 1917. In March 1921, a revolt

of the sailors, steadfastly loyal to the Bolsheviks

during the revolution, precipitated Vladimir Lenin’s

New Economic Policy. Kronstadt sailors also played

a major role in World War II in the defense of St.

Petersburg (then Leningrad) against the Germans.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, the indepen-

dence of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania deprived the

new Russian state of key bases on the Baltic Sea.

The 15,000-square-kilometer (5,800-square-mile)

Kaliningrad Oblast between Poland and Lithuania

remained as the fleet’s only ice-free naval outlet to

the Baltic Sea. One of the first steps taken in the

late 1990s to reform the Baltic Fleet was to incor-

porate air defense units into the Baltic Fleet struc-

ture. A second step was to restructure ground and

coastal troops on the Baltic Fleet units. As of 2000,

these forces consisted of the Moscow-Minsk Prole-

tarian Division, a Marine Brigade, Coastal Rocket

Units, and a number of bases at which arms and

equipment were kept. The Baltic Fleet did not in-

clude any strategic-missile submarines, but as of

mid-1997 it included thirty-two major surface

BALTIC FLEET

119

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

combatants (three cruisers, three destroyers, and

twenty-six frigates), more than 230 other surface

vessels, roughly two hundred naval aircraft, nine

tactical submarines, and a brigade of naval infantry.

As of mid-2000 the Baltic Fleet included about

one humdred combat ships of various types, and

the fleet’s Sea Aviation Group units were equipped

with a total of 112 aircraft. Operational forces as

of 1996 included nine submarines, twenty-three

principal surface combatants (three cruisers, two

destroyers, and eighteen frigates), and approxi-

mately sixty-five smaller vessels. The Baltic Fleet

included one brigade of naval infantry and two reg-

iments of coastal defense artillery. The air arm of

the Baltic Fleet included 195 combat aircraft orga-

nized into five regiments and a number of other

fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters. Generally,

armed forces comparable in size to the entire Pol-

ish army have been stationed in Kaliningrad Oblast.

In 1993 pressure for autonomy from the Russ-

ian Federation increased. Seventy-eight percent of

the population (about 900,000) is Russian. Some

claimed that, although Königsberg was awarded to

the Soviet Union under the Potsdam Accord in

1945, the Russian Federation held no legal title to

the enclave. Polish critics and others claimed that

the garrison should be reduced to a level of rea-

sonable sufficiency. Since Poland was admitted to

NATO in 1999, however, Russian nationalists have

argued that Kaliningrad is a vital outpost at a time

when Russia is menaced by Poland or even Lithua-

nia, if that country is also admitted to NATO.

See also: KRONSTADT UPRISING; MILITARY, POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Getzler, Israel. (2002). Kronstadt 1917–1921: The Fate of

a Soviet Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Hathaway, Jane. (2001). Rebellion, Repression, Reinven-

tion: Mutiny in Comparative Perspective. Westport, CT:

Praeger.

Hughes, Lindsey. (2001). Peter the Great and the West:

New Perspectives. New York: Palgrave.

Kipp, Jacob W. (1998). Confronting the Revolution in Mil-

itary Affairs in Russia. Fort Leavenworth, KS: For-

eign Military Studies Office.

Saul, Norman E. (1978). Sailors in Revolt: The Russian

Baltic Fleet in 1917. Lawrence: Regents Press of

Kansas.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

BANKING SYSTEM, SOVIET

In the Soviet economy, the role of money was ba-

sically passive: Planning was primarily in physical

quantities. Therefore, the banking system lacked

most of the tasks it has in market economy.

Money circulation was strictly divided into two

separate spheres. Households lived in a cash econ-

omy, facing mostly fixed-price markets for con-

sumer goods and labor. Inside the state sector,

enterprises could legally use only noncash, mone-

tary transfers through a banking system closely

controlled by the planners, for transactions with

other enterprises. Wages were paid out by a bank

representative, and retail outlets were tightly su-

pervised.

The banking system basically consisted of a

single state bank (Gosbank), which combined the

roles of a central bank and a commercial bank. Such

an arrangement is often called a monobank. Gos-

bank had no autonomy, but was basically a fi-

nancial control agency under the Council of

Ministers. As a central bank, Gosbank created nar-

row money (cash in circulation outside the state

sector) by authorizing companies to pay wages in

accordance with accepted wage bills. If government

expenditure exceeded government revenue, and suf-

ficient household savings were not available to

cover the budget deficit, state sector wage bills still

had to be paid, which would contribute to imbal-

ance in the consumer goods markets. This was

probably the case at least toward the end of the So-

viet period, though the relation between the state

budget, Gosbank, and money supply was among

the best-kept secrets in the USSR. Gosbank also

managed the currency reserves of the country.

As a commercial bank, Gosbank issued short-

term credit to enterprises for working capital.

Household savings were first kept by a formally

separate Savings Bank, which was incorporated

into the Gosbank in 1963. Household savings were

an important source of finance for the state. Gos-

bank also controlled Stroibank, the bank for fi-

nancing state investment, and Vneshekonombank,

the bank for foreign trade. There were also several

Soviet-owned banks abroad. In the perestroika pe-

riod, the number of specialized formally indepen-

dent banks increased, but no competition between

them was allowed. The emergence of cooperative

banks in 1988 and afterward had a key role in the

informal privatization of the Soviet economy and

the emergence of a market-based banking system.

BANKING SYSTEM, SOVIET

120

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The key role of the Soviet banking system was

in controlling plan fulfillment. The financial plan

was an essential component of enterprise planning.

All legal inter-enterprise payments had to go through

Gosbank, which only authorized payments that

were supported by a relevant plan document. Thus

the banking system was primarily a control

agency. This also meant that money was not a

binding constraint on enterprises: Any plan-based

transactions were authorized by Gosbank. The

banking system thus facilitated a soft budget con-

straint to enterprises: The availability of finance did

not constrain production or investment.

See also: GOSBANK; STROIBANK

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Garvy, George. (1977). Money, Financial Flows, and Credit

in the USSR. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Johnson, Juliet. (2000). A Fistful of Rubles: The Rise and

Fall of the Russian Banking System. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press.

Zwass, Adam. (1979). Money, Banking, and Credit in the

Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. White Plains, NY:

M. E. Sharpe.

P

EKKA

S

UTELA

BANKING SYSTEM, TSARIST

From the time of Emancipation onward, Russian

banks developed into the most important financial

intermediaries of the empire. They performed the

classic banking functions of collecting savings from

the population and allocating loans to creditwor-

thy borrowers. Initially Russian banks reflected the

backwardness of the economy and society in many

ways. The economy was still predominantly rural,

and mining and manufacturing enterprises com-

peted for resources with the government’s needs

for war finance and infrastructure and the nobil-

ity’s hunger for loans. Commercial honesty was

often unreliable, and therefore bankers had to be

cautious in making loans to strangers, even for the

short term.

Russian banks were more specialized than

banks elsewhere. At the center was the State Bank

(Gosudarstvenny Bank), established in 1860 to re-

place the more primitive State Commercial Bank

(founded in 1817) and informal arrangements

among merchants and industrialists. It stabilized

the ruble’s foreign exchange value, issued paper

currency, and accepted deposits from the treasury,

whose tax sources were mostly seasonal. Because

the government remained in deficit through the

1880s, in spite of the efforts of Finance Minister

Mikhail von Reutern, the State Bank also accom-

modated the treasury with loans of cash. The State

Bank helped further Russian interests in China and

Persia. As time went on, it served as lender of last

resort of the emerging private banks. When they

experienced illiquidity as a result of unexpected

withdrawals, the State Bank discounted their notes

and securities so the private bankers could pay de-

positors. Such episodes were common during the

recession of 1900–1902. Besides these central bank-

ing functions, the State Bank did some ordinary

lending, discreetly favoring government projects

such as railroad lines, ports, and grain elevators,

as well as some private engineering, textile, and

sugar ventures. For instance, the State Bank bought

shares of the Baltic Ironworks on the premise that

such firms, albeit private, had state significance.

The tsar’s government also sponsored Savings

Banks, which were frequently attached to post of-

fices. These institutions expanded their urban

branches during the 1860s and their rural outposts

two decades later. They accepted interest-bearing

accounts from small savers and invested in mort-

gages or government loans, notably for railroads.

Most Russian lending up to 1914 was backed

by land mortgages, the most secure collateral at this

time of rising land prices. Both the Peasants’ Land

Bank (founded 1882–1883) and the Nobility Bank

(1885) made such loans to the rural classes by is-

suing bonds to the public with government guar-

antees of their interest payments. In addition to

these banks, a large number of credit cooperatives

made small loans to peasants and artisans.

Private commercial banks were the last to

emerge in Russia. The founders of the main

Moscow banks were textile manufacturers, while

the directors of the St. Petersburg banks were of-

ten retired officials, financiers, or rich landowners.

By 1875 there were thirty banks in St. Petersburg

and Moscow; by 1914 the capital had 567 banks

and Moscow had 153. In 1875 the five major banks

had total assets of only 247 million rubles; by 1914

they would increase that figure nearly tenfold. Like

all other Russian banks, private and joint-stock

banks were subject to strict regulation by the Min-

istry of Finance, but after 1894 statutes were lib-

eralized, and state funds were put at their disposal.

Dealing at first with short-term commercial paper

BANKING SYSTEM, TSARIST

121

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

for business working capital, they gradually began

to lend for mortgages on urban land and industrial

projects. They also offered checking accounts to

business customers, thereby reducing transaction

costs over this vast empire. With interregional de-

liveries to make over long distances in difficult con-

ditions, manufacturers might have to wait months

for payments from merchants, who themselves

had widely separated customers. For all of them

short-term credit was crucial, as cash payments

were inconvenient.

Instead of the British-type commercial banks

typical of Moscow, which continued to deal in

short-term loans, St. Petersburg’s banks increas-

ingly resembled the universal bank model typical

of Germany. They helped float securities for urban

improvements, mines, and other private enterprises

against bonds and other securities as collateral

without government guarantees. They also opened

accounts secured by preferred shares with first call

on dividends for investors who formerly might

have demanded only fixed-interest obligations for

their portfolios. The largest of the joint-stock banks

attracted foreign capital, particularly from France

and Belgium, as well as from the State Bank. Some

of the larger heavy industrial projects so financed

were profitable, like the South Russian Dniepr Met-

allurgical Company, but many others were over-

promoted. According to Olga Crisp’s calculation,

based on data from Pavel Vasilievich Ol’, foreign-

ers held 45 percent of the total capital of the ten

largest joint-stock banks by 1916.

As in central Europe, each large bank had spe-

cial client companies on whose managing boards

the bankers sat. They facilitated discounting of the

affiliates’ bills and marketing of their common

stock. For example, Alexander Putilov, chairman of

the famous Russo-Asiatic Bank, was also head of

the Putilov engineering company, the historically

famous Lena Goldfields Company, the Nikolayev

Shipbuilding Company, and the Moscow-Kazan

railways, and director of at least three petroleum

companies. About 80 percent of the Russo-Asiatic

Bank’s equity capital was French-owned. The

Azov-Don Bank, based in St. Petersburg after 1903,

was heavily involved in coal, sugar, cement, and

steel enterprises. The International Bank, heavily

involved in shipbuilding, was 40 percent German-

owned. Occasionally these banks helped reorganize

and recapitalize failing enterprises, thus extending

their ownership control.

While demand for credit from private busi-

nessmen increased during the 1890s, the great ef-

florescence of tsarist banking came with the boom

following the war and revolutions of 1904 to 1906.

By 1913 there were more than one thousand pri-

vate and joint-stock banks in the country, still

mostly in the capitals, Warsaw, Odessa, and Baku.

Securities held by the Russian public more than

tripled between 1907 and World War I. Lending

was increasingly for heavy industry and the highly

profitable consumer goods industries, although the

latter could often rely on retained profits. The role

of the government thus declined as the main or-

gan of capital accumulation to be replaced by the

banks, as Alexander Gerschenkron has remarked.

As happened elsewhere, the Russian banks be-

came somewhat more concentrated. In 1900 the six

biggest commercial banks controlled 47 percent of

deposits and other liabilities. By 1913 that share

had risen to 55 percent. Marxists such as Vladimir

Lenin believed concentration of finance capital, and

these big capitalists’ underwriting of the cartels,

would bring on revolution. It seems highly doubt-

ful that this would have happened in absence of

war, however. In any case, all the tsarist banks

were nationalized by the Bolsheviks in 1917.

See also: ECONOMY, TSARIST; FOREIGN TRADE; INDUSTRI-

ALIZATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Crisp, Olga. (1976). Studies in the Russian Economy before

1914. London: Macmillan.

Falkus, M. E. (1972). The Industrialization of Russia,

1700–1914. London: Papermac.

Gatrell, Peter. (1986). The Tsarist Economy, 1850–1917.

New York: St. Martin’s.

Gerschenkron, Alexander. (1962). Economic Backwardness

in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Kahan, Arcadius. (1989). Russian Economic History, ed.

Roger Weiss. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kaser, Michael C. (1978). “Russian Entrepreneurship.” In

The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, vol. VII: The

Industrial Economies, Capital, Labour, and Enterprise,

Part 2, The United States, Japan, and Russia, eds. Pe-

ter Mathias and M. M. Postan. London: Cambridge

University Press.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

BANYA

A Russian steam sauna or bathhouse, which served

as the primary form of hygiene and was consid-

BANYA

122

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY