Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Jasny, Naum. (1972). Soviet Economists of the Twenties.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

V

INCENT

B

ARNETT

BEARD TAX

The beard tax is the best known of a series of mea-

sures enacted by Tsar Peter I to transform and reg-

ulate the appearance of his subjects. As early as

1698 the tsar ordered many of his prominent

courtiers to shave their beards, and in 1699 he be-

gan to mandate the wearing of European fashions

at court functions. In subsequent years a series of

regulations ordered various groups to adopt Ger-

man (i.e., European) dress. In 1705 decrees were is-

sued prohibiting the buying, selling, and wearing

of Russian dress by courtiers, state servitors, and

townspeople. In the same year the wearing of

beards, which was favored by Orthodox doctrine,

was prohibited and the beard tax was instituted.

With the exception of the Orthodox clergy, anyone

who wanted to wear a beard was ordered to pay a

special tax and obtain a token (znak) from gov-

ernment officials. Although no extensive studies

have examined the implementation of the beard tax

and related decrees, the fact that they had to be re-

peated upon subsequent occasions would indicate

that compliance was far from universal. Old Be-

lievers (Orthodox Church members who rejected

reforms in ritual and practice) were disproportion-

ately affected by the beard tax and they alone were

ordered by law to wear old-style Russian dress (to

separate them from the mainstream of society). The

beard tax was never a major component of state

revenue, and by the reign of Catherine II even the

regulations on Old Believers began to be relaxed.

See also: OLD BELIEVERS; PETER I; TAXES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hughes, Lindsey. (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the

Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

B

RIAN

B

OECK

BEDNYAKI

A traditional Russian term denoting a poor peas-

ant household, one without enough land or capi-

tal to support itself without hiring out family

members to work on neighbors’ fields.

During the Black Repartition, which occurred

during the revolutionary events of 1917 and 1918,

Russian peasants seized land owned by noble and

absentee landlords and the more substantial peas-

ants, some of whom had consolidated holdings

during the Stolypin reforms of 1906–1914. Thus

the number of peasant holdings increased markedly,

and the size of the average plot declined. Many vil-

lages returned to the scattered strips and primitive

tools characteristic of tsarist times. Use of the

wooden plow, sickle, or scythe were common

among the poorer peasants. These subsistence agri-

culturists typically had one cow or draft animal,

along with a small wooden house and naturally

had little or nothing to sell in the market. Many

poor peasants had been proletarian otkhodniki (mi-

grants) or soldiers before and during the war, but

the economic collapse forced them to return to their

ancestral villages. The village community (ob-

shchina or mir) resumed its authority over the tim-

ing of agricultural tasks and occasional repartition.

Hence the Bolshevik Revolution constituted a social

and economic retrogression in the countryside.

Considering their economic plight, the bed-

nyaki, along with the landless batraki, were ex-

pected to be rural allies of the proletariat. According

to Bolshevik thinking in the period of War Com-

munism and the New Economic Policy, these lower

classes would support the government’s policy and

would eventually be absorbed into collective or

communal farms. Those middle peasants (sered-

nyaki) with slightly more land and productive cap-

ital were expected to tolerate Bolshevik policy only,

while the so-called kulaks would oppose it. In re-

ality the various peasant strata lacked any strong

class lines or reliable political orientation.

See also: BLACK REPARTITION; KULAKS; NEW ECONOMIC

POLICY; PEASANTRY; SEREDNYAKI; WAR COMMUNISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lewin, Moshe. (1968). Russian Peasants and Soviet Power:

A Study of Collectivization, tr. Irene Nove and John

Biggart. London: Allen and Unwin.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

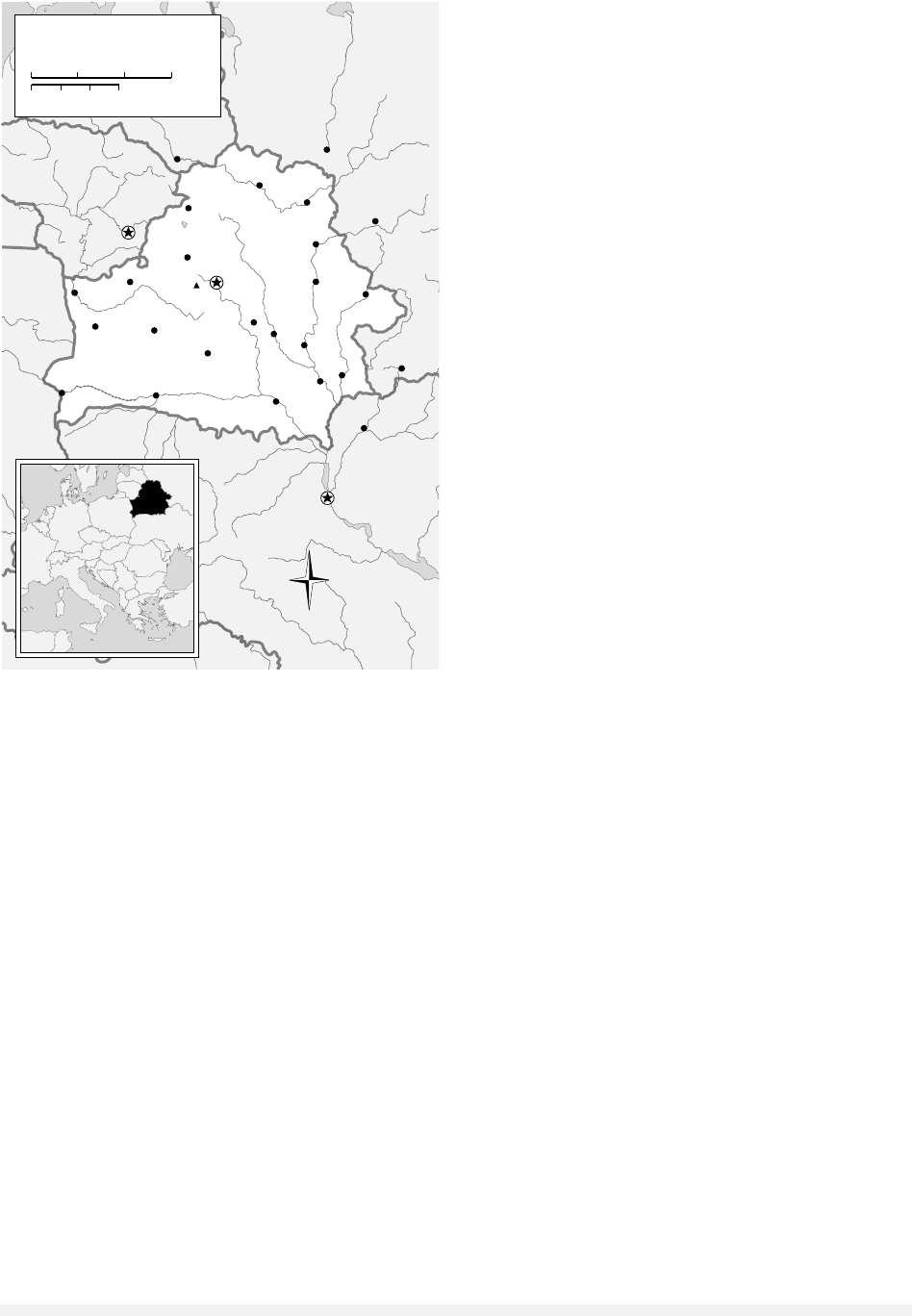

BELARUS AND BELARUSIANS

Bounded by Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Russia, and

Ukraine, Belarus is an independent country of

about the size of Kansas. In 2000 its population

was about 10.5 million. Over the course of its

BELARUS AND BELARUSIANS

133

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

history, this territory has been of part of Kievan

Rus, the Grand Principality of Lithuania, Poland-

Lithuania, the Russian Empire, interwar Poland

(western Belarus only), and the Soviet Union.

The origin of the name Belarus is obscure. Its

territory, encompassing much of the drainage sys-

tems of the Pripyat River and upper reaches of the

Nieman, Western Dvina, and Dnieper Rivers, com-

prises the medieval Polotsk and Turov principali-

ties, with the addition of the western lands of

Smolensk and Chernigov around Mogilev and

Gomel, but minus the territory south of Pinsk.

Some specialists consider the forests and

swamps of southwestern Belarus part of the orig-

inal homeland of Slavic speakers and possibly the

Indo-Europeans. Baltic speakers inhabited much of

Belarus before Slavic speakers migrated there after

500 C.E. Around 900 the Slavic Dregovichi and

Radmichi inhabited the eastern half of Belarus,

while Baltic Iatvingians dwelled in the northwest.

Specialists’ opinions differ as to when and where a

distinct Belarusian language and people formed and

the degree to which they represent a Baltic and east-

ern Slavic mixture.

Around 980 Polotsk was under a separate

Varangian prince, the non-Riurikid Rogvolod, whom

Vladimir of Novgorod slew en route to seizing Kiev.

Vladimir’s son Iziaslav, by Rogvolod’s daughter

Ragneda, founded there the first lasting Rus terri-

torial subdynasty, and the latter’s son and grand-

son, Briachislav and Vseslav Briachislavich (d.

1101), built up Polotsk. Vseslav’s granddaughter

St. Evfrosynia founded a noted convent there.

In the 1100s Polotsk split into subprincipalities

and by 1200 Volhynia controlled the Brest region,

while Germans were eliminating Polotsk’s tradi-

tional loose overlordship over the tribes of modern

Latvia. In the early 1200s the Smolensk princes

spearheaded commercial agreements with the Baltic

Germans and Gotland Swedes, which included

Vitebsk and Polotsk.

By the mid-1200s, Lithuanian princes—some

Orthodox Christians, some pagans controlled—

Polotsk, Novogrudok, and nearby towns. With the

pagan Lithuanian absorption of all the former

Polotsk and Turov lands in the 1300s, the surviv-

ing local Rus princes transformed into territorial

aristocrats. Rus institutions spread into ethnic

Lithuania, and Rus became the domestic chancery

language of the ethnically mixed realm. For about

half of the fourteenth century, a separate Western

Rus metropolitanate was located in Novogrudok.

Minsk grew in importance at this time near the di-

vide between the Nieman and Dnieper watersheds.

The Orthodox Lithuanian prince Andrei of Polotsk

(d. 1399) fought at Kulikovo against Mamai in

1380.

The 1385 Polish-Lithuanian dynastic Union of

Krevo (in western Belarus) privileged nobles who

converted to Catholicism. After a civil war in the

1430s, the local Orthodox Rus nobility obtained

these same, Polish-inspired rights, but Orthodox

prelates never acquired the same political privileges

as their Catholic counterparts. Starting with Brest

in 1390, several Rus towns obtained a form of

Neumarkt-Magdeburg, the most prevalent form of

medieval autonomous city law to spread into east-

central Europe. After the misfired Church Union of

Florence of 1439, Moscow’s authority split with

the metropolitanate of Kiev, which retained the dio-

ceses in Belarus.

BELARUS AND BELARUSIANS

134

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Dzerzhinskaya Gora

1,135 ft.

346 m.

Pinsk Marsh

B

E

L

O

R

U

S

S

K

Y

A

G

R

Y

A

D

A

P

r

i

p

y

a

t

s

'

B

u

g

N

y

o

m

a

n

.

P

t

s

i

c

h

D

n

i

e

p

e

r

B

y

a

r

e

z

i

n

a

S

o

z

h

Z

a

c

h

D

v

i

n

a

D

y

n

a

p

r

o

w

s

k

a

-

B

u

h

s

k

i

K

a

n

a

l

Pinsk

Mazyr

Rechitsa

Bryansk

Chernihiv

Krychaw

Smolensk

Zhlobin

Babruysk

Salihorsk

Asipovichy

Baranavichy

Lida

Vawkavysk

Maladzyechna

Polatsk

Orsha

Velikye Luki

Pastavy

Daugavpils

Brest

Homyel'

Mahilyow

Vitsyebsk

Hrodna

Minsk

Vilnius

Kiev

LITHUANIA

RUSSIA

UKRAINE

POLAND

LATVIA

Belarus

W

S

N

E

BELARUS

150 Miles

0

0

150 Kilometers

10050

50 100

Belarus, 1992. © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH

PERMISSION

With the dynastic union, some Rus acquired a

genuine Western education, and Rus writers cre-

ated a set of Lithuanian chronicles with a legendary

foundation of the leading families and the realm.

Jewish culture flourished, and some holy scripture

and other Jewish books were translated directly

from Hebrew into the local Rus dialect. In 1517

Frantishek Skoryna of Polotsk initiated systematic

Kirillic and Slavic printing with his Gospels.

During the 1500s, with growing estate agri-

culture, a form of serfdom binding peasants to the

land with about two days of labor dues per week

became the dominant peasant status, but the Rus-

language First Lithuanian Statute of 1529 was one

of the most advanced law codes in Europe at that

time. Moscow’s occupation of Polotsk in 1563 led

to the stronger Polish-Lithuanian Union of Lublin

in 1569, whereby Lithuania transferred its Ukrain-

ian lands to Poland, but retained the Belarusian ter-

ritories. The brilliant, Orthodox-turned-Catholic

Leo Sapieha (Leu Sapega) compiled the Rus-

language Third Lithuanian Statute in 1588, which

remained in use for more than two centuries. He

also organized the renowned state archive or

Metrika.

Under the impact of the Protestant Reforma-

tion, the Lithuanian Radvilas (Radzivil) family

turned their central Belarusian fortress town of

Nesvizh into a center of Calvinist learning and

printing, but with the arrival of the Counter Re-

formation, Nesvizh became a Roman Catholic

stronghold. Jesuits founded schools there and in six

other Belarusian towns and helped cause the polo-

nization of the local Rus nobility.

In 1596 the Polish crown, but not the Sejm

(parliament), tried to force the Church Union of

Brest on the Orthodox in 1596, creating at first an

Eastern Rite Uniate hierarchy without many faith-

ful, and leaving most of the faithful without a hi-

erarchy. Over the course of time, however, the

Uniate Church grew and a Catholic-influenced Uni-

ate Basilian Order of monks took over the great

monasteries in Belarus. In 1623 angry Vitebsk Or-

thodox murdered their fanatic Uniate bishop Iosafat

Kunchvich, who had confiscated their churches and

monasteries, and the crown responded with mass

executions. In 1634 the Orthodox Church regained

its legality but not much property. Some talented

Orthodox clerics, such as Simeon Polotsky

(1629–1680), made splendid careers in Moscow. A

1697 decree banned the use of Rus in official state

documents. By the late eighteenth century, the Uni-

ate Church was far stronger than the Orthodox in

Belarus and in the western regions many com-

moners had become Roman Catholic.

Belarusians constituted perhaps one-eighth of

the insurgents in the mid-seventeenth century who

rebelled against the serfdom and Catholic-Uniate

privileges in Poland-Lithuania, but then suffered

heavily from the Muscovite invasions in 1654–1655

and 1659. Ethnic Belarus urban life declined, and

Jews, despite some heavy losses in the uprisings,

became more prominent in many towns. Brest,

however, lost its regional cultural preeminence

among the Litvak Jews to Vilnius in Lithuania.

The Belarus lands suffered again during the

Great Northern War, especially during the period

from 1706 to 1708, due to the Swedish-Russian

fighting there. Later in the eighteenth century the

economy recovered, stimulated by domestic and in-

ternational markets and led by enlightened estate

management and manufactures.

Polish-language serf theaters appeared in 1745,

and Poland’s educational reforms of 1773 estab-

lished an ascending network, with divisional

schools in Brest, Grodno, and Novogrudok, and a

university in Vilnius. Several Belarusians were ac-

tive in the Polish Enlightenment.

The three-stage annexation of Belarus by Rus-

sia during the partitions of Poland (1772, 1793,

1795) had profound effects. The emperors respected

Polish culture and educational and religious insti-

tutions only until the Polish uprising of 1830–1831.

Subsequently, cooperative Belarusians played a

major role in weakening Catholicism, suppressing

the Uniate Church, restoring Orthodoxy and Rus-

sianizing education, as well as publishing histori-

cal documents and doing normal administrative

work.

Though not a main center of heavy industry,

Belarus shared in the Russian Empire’s social and

economic development in the nineteenth century

and had many small enterprises.

Belarusian national consciousness developed

relatively late. Polish and Polish-language intellec-

tuals promoted the idea of a separate, non-Russian,

Belarusian (or White Ruthenian) folk. After Belaru-

sians did not support Poles in the 1863–1864

uprising, interested Russians became more sympa-

thetic to the notion of Belarusians as a distinct

provincial group and started to collect local folk-

lore. Genuine Belarusian-language literature started

only in the 1880s. Circles of Belarusian students

and intellectuals in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Dor-

pat, and other university cities sprung up in the

BELARUS AND BELARUSIANS

135

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

1890s. Only after the Revolution of 1905 was pub-

lication in Belarusian legalized. Hramada, the so-

cialist and largest Belarusian political organization,

could not compete with the more developed Russ-

ian, Polish, and Jewish parties or elect a delegate to

any of the four Dumas.

The German advances and defeat in World War

I and the Russian Revolution and Civil War stim-

ulated a dozen competing projects for reorganizing

Belarus, including a restoration of a federated

prepartition Lithuania and/or Poland. The revived

Poland and Communist Russia divided Belarus in

1921, the eastern portion becoming the Belarusian

Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) of the USSR in

1923–1924. In western Belarus, Polish authorities

favored polonization, suppressing a variety of na-

tional and autonomist strivings. The BSSR author-

ities, including Russians there, at first promoted

belarusianization of domestic life, and national,

cultural, and educational institutions grew apace,

including a university and academy of sciences in

the capital Minsk. However, the rhythms of inter-

war Soviet development—New Economic Policy,

collectivization, five-year plans, bloody purges, and

reorientation to a Russian-language—dominated

all-union patriotism—affected the BSSR.

The Soviet-German Pact of 1939 and World

War II brought a quick unification of an expanded

BSSR, a harsh Nazi occupation and requisition of

labor, the extermination of most Belarusian Jews,

widespread partisan activity, and the total death of

maybe a million inhabitants—about one eighth of

the population. Allied diplomacy resulted in the

BSSR (and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic)

acquiring a separate seat in the United Nations Gen-

eral Assembly in 1945.

The BSSR also followed the rhythm of postwar

Soviet developments, becoming heavily industrial-

ized with its own specialty tractors and heavy-duty

trucks, as well as a variety of other basic goods.

The country achieved virtual universal literacy, but

the Russian language and culture predominated in

the cities and in higher education. Due to prevail-

ing winds, Belarus suffered heavily from the Cher-

nobyl explosion in 1986.

The BSSR played a secondary role in reform and

national movements leading to the end of the USSR

and an independent Belarus. Its first leader, Stanislav

Shushkevich tried to balance between Russia and the

West, but lost the 1994 presidential election to the

Alexander Lukashenko, who proved adept in using

referendum tactics and police measures to establish

an authoritarian regime with a neo-Soviet orienta-

tion, and perpetuate his power. Dependence on

Russian energy resources and markets have ce-

mented close ties, but plans for a state union with

Russia have faltered over Russian demands that Be-

larus liberalize its economy and Lukashenko’s in-

sistence that Belarus be an equal partner.

See also: CHERNOBYL; JEWS; LITHUANIA AND LITHUANI-

ANS; NAZI-SOVIET PACT OF 1939; ORTHODOXY;

POLAND; POLISH REBELLION OF 1863; UNIATE CHURCH;

UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Marples, David R. (1999). Belarus. A Denationalized Na-

tion. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic.

Vakar, Jan. (1956). Belorussia. The Making of a Nation, a

Case Study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Zaprudnik, Jan. (1993). Belarus: At a Crossroads in His-

tory. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

D

AVID

M. G

OLDFRANK

BELINSKY, VISSARION GRIGORIEVICH

(1811–1848), Russian literary critic whose frame-

work of aesthetic judgment influenced Russian and

Soviet critical standards for almost two centuries;

he established a symbiotic relationship between the

writer and the critic whose creative interaction he

considered a tool of societal self-exploration.

Belinsky’s father was a navy physician, his

mother a sailor’s daughter, making the future critic

a raznochinets (person of mixed class background).

He was born in the fortress of Sveaborg (today

Suomenlinna, Finland) and spent his childhood in

the town of Chembar (Penza region), where his fa-

ther worked as a district doctor. Belinsky enrolled

at Moscow University in 1829 but was expelled in

1832 due to frail health and a reputation as a trou-

blemaker. Often on the verge of poverty and de-

pendent on the support of devoted friends, Belinsky

became a critic for Nikolai Ivanovich Nadezhdin’s

journals, Telescope and Molva, in 1834. His exten-

sive debut, Literaturnye mechtaniya: Elegiya v proze

(Literary Daydreams: An Elegy in Prose), consisted

of ten chapters. At this stage, Belinsky’s under-

standing of literature featured a lofty idealism in-

spired by Friedrich Schiller, as well as the notion of

popular spirit (narodnost), which signified the ne-

cessity of the “idea of the people” in any work of

art. This concept was adopted from the German

BELINSKY, VISSARION GRIGORIEVICH

136

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Volkstuemlichkeit that was developed by Johann

Gottfried Herder and Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling.

Belinsky’s participation, since 1833, in Nikolai

Vladimirovich Stankevich’s Moscow Hegelian cir-

cle, as well as his close friendship with Mikhail

Alexandrovich Bakunin, had by 1837 caused him

to make a radical move toward an unconditional

acceptance of all reality as reasonable. However, Be-

linsky’s habitual tendency toward extremes turned

his interpretation of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich

Hegel’s dialectic rationalism into a passive accep-

tance of everything that exists, even serfdom and

the tsarist system. Such fatalism became evident in

Belinsky’s surveys and reviews for Andrei Alexan-

drovich Kraevsky’s journal Otechestvennye zapiski

(Notes of the fatherland), the criticism department

of which he headed since 1839. Subsequently, in

the early 1840s, a more balanced synthesis of

utopian aspirations and realistic norms emerged in

Belinsky’s views, as evidenced by his contributions

for Nikolai Alexeyevich Nekrasov’s and Ivan

Ivanovich Panaev’s Sovremennik (Contemporary), a

journal that had hired him in 1846.

Belinsky met all leading Russian authors of his

day, from Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin and

Mikhail Yurievich Lermontov to Ivan Andreyevich

Krylov and Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev, befriending

and deeply influencing many of them. In 1846, he

coined the critical term Natural School, thereby pro-

viding a group of writers with direction and a plat-

form for self-identification. Even those who did not

share his strong liberal persuasions were in awe

of his personal integrity, honesty, and selflessness.

Belinsky’s passionate, uncompromising nature

caused clashes that gave rise to major intellectual

debates. For example, in his famous letter to Niko-

lai Vasilievich Gogol, written on July 15, 1847, the

critic took this once so admired writer to task for

his mysticism and conservatism; the letter then cir-

culated widely, in hundreds of illegal copies.

In his last years, Belinsky attempted to create

a theory of literary genres and general philosoph-

ical definitions of the essence and function of art.

After his early death from tuberculosis, his name

became synonymous with dogmatism and anti-

aesthetic utilitarianism. Yet this reputation is

largely undeserved; for it resulted from the critic’s

canonization by liberal and Marxist ideologues.

Still, from his earliest works Belinsky did betray a

certain disposition toward simplification and sys-

tematization at any cost, often reducing complex

entities to binary concepts (e.g., the classic opposi-

tion of form versus content). Indeed, Belinsky de-

voted little time to matters of literary language,

rarely engaging in detailed textual analysis. How-

ever, his theories and their evolution, too, were

simplified, both by his Soviet epigones and their

Western antagonists.

Belinsky has undoubtedly shaped many views

of Russian literature that remain prevalent, in-

cluding a canon of authors and masterpieces. For

example, it was he who defended Lermontov’s 1840

novel, Geroi nashego vremeni (Hero of Our Time), as

a daringly innovative work and who recognized

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s supreme talent. (At the same

time, he ranked Walter Scott and George Sand

higher than Pushkin). Belinsky, the first major

professional Russian literary critic, stood at the cra-

dle of Russia’s literary-centric culture, with its

supreme social and ethical demands. His ascetic per-

sona and quest for martyrdom became archetypal

for the Russian intelligentsia’s sense of mission.

Lastly, Belinsky defined the ideal image of the Russ-

ian writer as secular prophet, whose duty is to re-

spond to the people’s aspirations and point them

toward a better future.

See also: DOSTOYEVSKY, FYODOR MIKHAILOVICH; GOGOL,

NIKOLAI VASILIEVICH; INTELLIGENTSIA; KRYLOV, IVAN

ANDREYEVICH; LERMONTOV, MIKHAIL YURIEVICH;

PUSHKIN, ALEXANDER SERGEYEVICH; TURGENEV, IVAN

SERGEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bowman, Herbert. (1969). Vissarion Belinski: A Study in

the Origins of Social Criticism in Russia. New York:

Russell and Russell.

Terras, Victor. (1974). Belinskij and Russian Literary Crit-

icism: The Heritage of Organic Aesthetics. Madison:

University of Wisconsin Press.

P

ETER

R

OLLBERG

BELOVEZH ACCORDS

This treaty, also known as the Minsk Agreement,

brought about the end of the Soviet Union. It was

concluded on December 8, 1991, by President Boris

Yeltsin of Russia, President Leonid Kravchuk of

Ukraine, and Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of

Belarus Stanislav Shushkevich, who met secretly in

a resort in Belovezhska Pushcha, just outside of

Brest, Belarus. According to most reports, the three

leaders had no common consensus on the future

of the Soviet Union prior to the meeting, but, once

BELOVEZH ACCORDS

137

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

they assembled, they decided to shelve plans to

preserve some sort of reformed Soviet state, as

preferred by Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev,

and instead pressed for its dissolution. In the days

that followed, Gorbachev would try in vain to pre-

serve the USSR, but there was little mass or elite

support for its continued existence, at least in these

three republics.

The treaty noted that “the USSR has ceased to

exist as a subject of international law and a geopo-

litical reality” and stated that the activities of bod-

ies of the former USSR would be henceforth

discontinued. Its drafters asserted the authority to

do this by noting that Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus

were the three surviving original founders of the

Soviet state in 1922. In its stead, these three re-

publics agreed to form a new organization, the

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which

was designed to foster a variety of forms of eco-

nomic, political, social, and military cooperation.

Specifically, the accords guaranteed equal rights

and freedoms to all residing in those states, pro-

vided for the protection of ethnic and linguistic

minorities, recognized each state’s borders, empha-

sized the need for arms control, preserved a united

military command and common military-strategic

space, and pledged cooperation on the Chernobyl

disaster. Later that December, eight more former

Soviet republics would join the CIS, and by De-

cember 25, 1991, the Soviet flag was at last re-

moved from the top of the Kremlin.

No participant has produced a definitive and

detailed account of the meeting in Belovezhska

Pushcha, and the accords remain the subject of

some controversy, particularly in Russia. At the

time of its signing, the agreement was widely cel-

ebrated, with only five deputies in the Russian leg-

islature voting against its ratification, and Ukraine

adding twelve reservations to its ratification, di-

rected toward weakening any sort of new union or

commonwealth. However, over the course of time,

many, especially in Russia and Belarus, have dis-

puted the right of the three leaders to conclude this

treaty and have lamented the lack of open debate

and popular input into its conclusion. In March

1996, the Russian Duma voted overwhelmingly to

annul it, and this action led many to fear possible

Russian attempts to reestablish the Soviet Union or

some other form of authority over other republics.

Moreover, in the 1990s the accord began to lose

popularity among the Russian population, which,

public opinion polls repeatedly revealed, began to

regret the breakup of the Soviet Union.

See also: COMMONWEALTH OF INDEPENDENT STATES;

UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Library of Congress. “The Minsk Agreement.” (n.d.)

<http://memory.loc.gov/frd/cs/belarus/by_appnb

.html>.

Norwegian Institute of International Affairs–Centre

for Russian Studies. (n.d.). “Belovezh Agreement,

Creating the CIS.” <http://www.nupi.no/cgi-win/

Russland/krono.exe?895>.

Norwegian Institute of International Affairs–Centre

for Russian Studies. (n.d.). “Reactions to Creation

of CIS.” <http://www.nupi.no/cgi-win/Russland/

krono.exe?2149>.

Olcott, Martha Brill. (1999). Getting It Wrong: Regional

Cooperation and the Commonwealth of Independent

States. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace.

P

AUL

J. K

UBICEK

BELY, ANDREI

(1880–1934), symbolist poet, novelist, essayist.

Andrei Bely was born Boris Nikolayevich

Bugayev on October 26, 1880, in Moscow. His fa-

ther, Nikolai Bugayev, was a professor of mathe-

matics at Moscow University and a renowned

scholar; his mother, Alexandra, was dedicated to

music, poetry, and theater. This dichotomy was to

influence and torment Boris throughout his life: He

would resist both parents’ influences while contin-

ually seeking syntheses of disparate subjects.

At age fifteen, Boris met the intellectually gifted

Soloviev family. Vladimir Soloviev was a philoso-

pher, poet, theologian, and historian whose con-

cept of the “Eternal Feminine” in the form of

“Sophia, the Divine Wisdom” became central to

Symbolist thought. Vladimir’s younger brother

Mikhail took Boris under his wing, encouraging

him as a writer and introducing him to Vladimir

Soloviev’s metaphysical system.

From 1899 to 1906 Boris studied science, then

philosophy at Moscow University. However, his

absorption in his writing and independent research

interfered with his formal studies. Restless and er-

ratic, he took interest in all subjects and confined

himself to none. His idiosyncratic writing style de-

rives in part from his passionate, undisciplined ap-

proach to knowledge, a quality that would later

BELY, ANDREI

138

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

be deemed decadent by socialist critics, including

Leon Trotsky.

Mikhail Soloviev applauded Boris’s early liter-

ary endeavors and suggested the pseudonym An-

drei Bely (“Andrew the White”). Bely’s four

Symphonies (1902–1908) combine poetry, music,

and prose. Bely’s first poetry collection, Gold in

Azure (Zoloto v lazuri, 1904), uses rhythms of folk

poetry and metrical innovations. Like Alexander

Blok and other Symbolists, Bely saw himself as a

herald of a new era. The poems of Gold in Azure

are rapturous in mood and rich in magical, myth-

ical imagery. Bely’s next poetry collections move

into murkier territory: Ashes (Pepel, 1909) expresses

disillusionment with the 1905 revolution, while

Urn (Urna, 1909) reflects his affair with Blok’s wife,

Lyubov, which caused hostility, even threats of du-

els, between the two poets.

Bely followed his first novel, The Silver Dove

(Serebryany golub, 1909), with Petersburg (1916),

which Vladimir Nabokov considered one of the four

greatest novels of the twentieth century (Strong

Opinions, 1973). It concerns a terrorist plot to be

performed by Nikolai Apollonovich against his fa-

ther, Senator Apollon Apollonovich Ableukhov. The

novel’s nonsensical dialogue, ellipses, exclamations,

and surprising twists of plot, while influenced by

Nikolai Gogol and akin to the work of the Futur-

ists, take Russian prose in an unprecedented direc-

tion. The novel’s main character is Petersburg itself,

which “proclaims forcefully that it exists.”

While writing Petersburg, Bely found a new

spiritual guide in Rudolf Steiner, whose theory of

anthroposophy—the idea that each individual,

through training, may access his subconscious

knowledge of a spiritual realm—would inform

Bely’s next novel, the autobiographical Kitten

Letayev (Kotik Letayev, 1917–1918).

Like other Symbolists, Bely welcomed the Oc-

tober Revolution of 1917. He moved to Berlin in

1921, but returned in 1923 to a hostile literary cli-

mate. Bely tried to make room for himself in the

new era by combining Marxism with anthroposo-

phy, but to no avail.

A prolific and influential critic, Bely wrote more

than three hundred essays, four volumes of mem-

oirs, and numerous critical works, including his

famous Symbolism (1910), which paved the way

for Formalism, and The Art of Gogol (Masterstvo

Gogolya, 1934). He died of arterial sclerosis on Au-

gust 1, 1934.

See also: BLOK, ALEXANDER ALEXANDROVICH; SILVER AGE;

SOLOVIEV, VLADIMIR SERGEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexandrov, Vladimir. (1985). Andrei Bely: The Major

Symbolist Fiction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press.

Elsworth, J. D. (1983). Andrey Bely: A Critical Study of

the Novels. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Maslenikov, Oleg A. (1952). The Frenzied Poets: Andrey

Biely and the Russian Symbolists. Berkeley: Univer-

sity of California Press.

Mochulsky, Konstantin. (1977). Andrei Bely: His Life and

Works, tr. Nora Szalavitz. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

D

IANA

S

ENECHAL

BERDYAYEV, NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH

(1874–1948), philosopher.

Nikolai Berdyayev, a scion of the landed gen-

try, was born on an estate near Kiev. The Russian

philosopher best known in the West, he moved

from Marxism to Kantian Idealism to a Christian

existentialism meshed with leftist political views. A

lifelong opponent of bourgeois society and bour-

geois values, in emigration he called capitalism and

communism equally unchristian.

As a leader in the religious and philosophical

renaissance of the early twentieth century, he de-

cried the atheism and dogmatism of the revolu-

tionary intelligentsia, while also polemicizing

against the otherworldliness and passivity enjoined

by historical Christianity. He believed that a Third

Testament would supersede the Old and the New

Testaments.

Expelled from Russia by the Bolshevik govern-

ment in late 1922, in 1924 he settled near Paris and

played an active role in émigré and French intellec-

tual and cultural life. His books were translated into

many languages. His critique of the revolutionary

intelligentsia and his articulation of the Russian idea

had a profound impact on late Soviet and post-

Soviet thought.

Berdyayev’s philosophy is anthroposophic,

personalistic, subjective, and eschatological. He em-

phasized the supreme value of the person, opposed

all forms of objectification, and exalted a freedom

BERDYAYEV, NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH

139

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

unconstrained by norms or laws, including the

laws of nature. Rejecting all dogmas, orthodoxies,

systems, and institutions, and all forms of deter-

minism, he linked freedom with creativity, which

he considered man’s true vocation, and taught that

man is a co-creator with God. By “man” he meant

men; he regarded “woman” as “generative but not

creative.” He interpreted the Bolshevik Revolution

as part of a pan-European crisis, the imminent end

of the civilization that began in the Renaissance,

and looked forward to a period he called the new

middle ages.

The literature on Berdyayev is extensive and

varied. Some authors exalt him as a philosopher of

freedom, others emphasize his utopianism, and still

others consider him a heretic.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berdiaev, Nicolas. (1955). The Meaning of the Creative Act,

tr. Donald Lowrie. New York: Harper.

Lowrie, Donald. (1960). Rebellious Prophet: A Life of Niko-

lai Berdiaev. New York: Harper.

Zenkovsky, V. V. (1953). A History of Russian Philoso-

phy, tr. George L. Kline. 2 vols. New York: Colum-

bia University Press.

B

ERNICE

G

LATZER

R

OSENTHAL

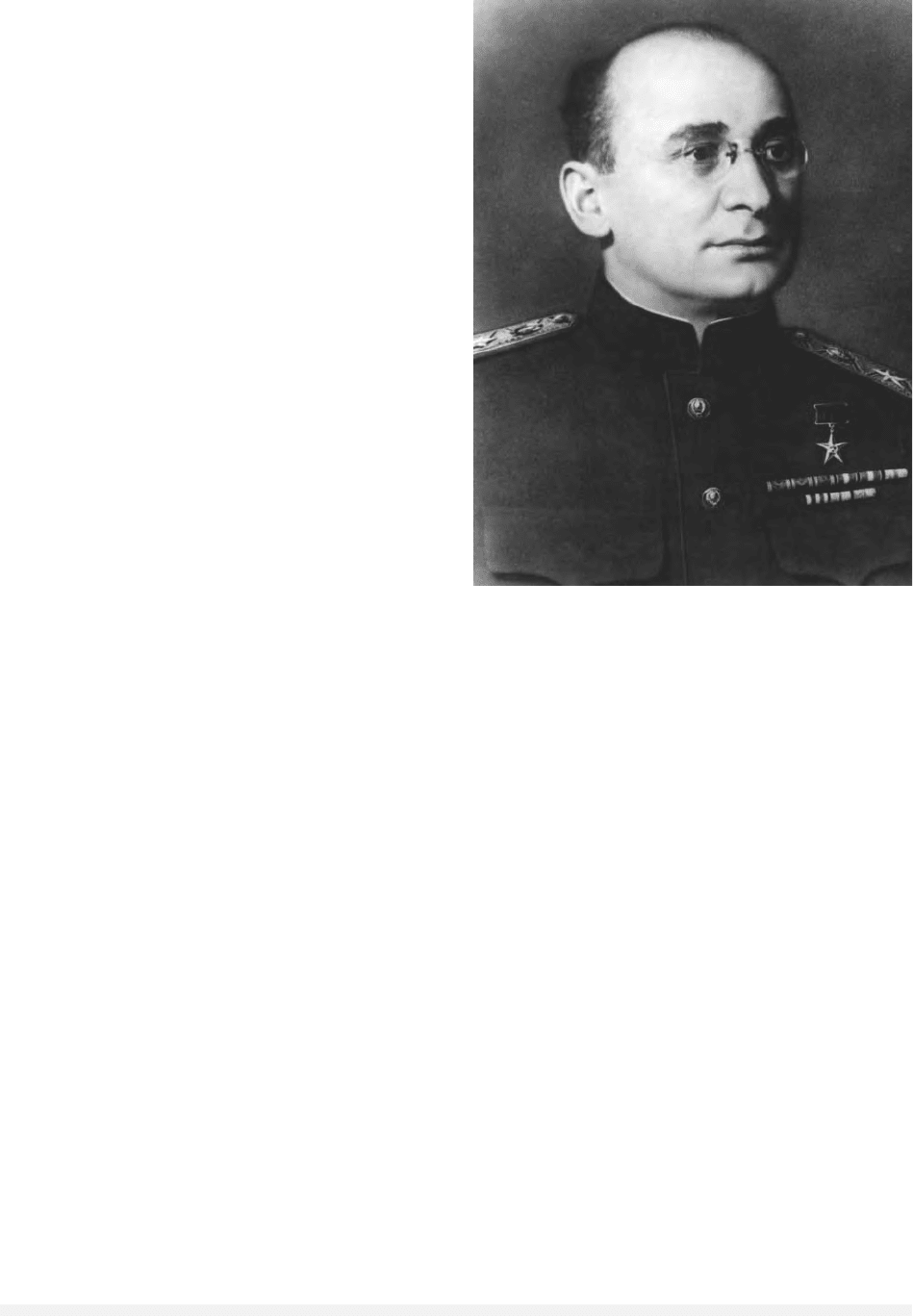

BERIA, LAVRENTI PAVLOVICH

(1899–1953), Soviet politician and police official,

chief of the NKVD 1938–1946.

Born in Merkheuli, a village in the Georgian Re-

public, Lavrenti Beria enrolled in the Baku Polytech-

nic for Mechanical Construction in 1915 and

graduated four years later. Meanwhile, after joining

the Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social Democra-

tic Labor Party in March 1917, he participated in

the Russian Revolution as an underground soldier

and counterintelligence agent in the Caucasus. Be-

ria’s career with the Soviet secret police began in

early 1921, when the ruling Bolsheviks assigned him

to the notorious Cheka (Extraordinary Commission

for Fighting Revolution and Sabotage) in the Soviet

Republic of Azerbaijan. As a deputy to the ruthless

Cheka chief in that republic, Mir Dzhafar Bagirov,

Beria engaged in bloody reprisals against the oppo-

nents of Bolshevik rule, even drawing criticism from

some Caucasian Bolshevik leaders for the vio-

lent methods he used. By late 1922, with the anti-

Bolshevik rebels in Azerbaijan subdued, Beria was

transferred to Georgia, where there were still seri-

ous challenges to the Soviet regime. He assumed the

post of deputy chairman of the Georgian Cheka,

throwing himself into the job of fighting political

dissent among his fellow Georgians. Beria’s influ-

ence grew as the political police played an increasing

role in Georgian politics. His career was successful

because he helped to engineer the defeat of the na-

tional communists, who wanted Georgia to retain

some form of independence from Moscow, and the

consequent victory of those who favored strong cen-

tralized control by the Bolsheviks.

By 1926 Beria had risen to the post of chair-

man of the Georgian GPU (State Political Adminis-

tration, the successor organization to the Cheka).

Beria was the consumate Soviet politician. His po-

litical fortunes were furthered not only by his ef-

fectiveness in using the secret police to enforce

Soviet rule, but also by his ability to win favor

with Soviet party leader Josef Stalin, a Georgian by

nationality, by playing on Stalin’s suspicions of the

native Georgian party leadership. Having extended

his influence into the party apparatus, Beria was

elected in 1931 to the post of first secretary of the

Georgian party apparatus, a remarkable achieve-

ment for a man of only thirty-two years. Hence-

forth Beria would continue to ingratiate himself

with Stalin by furthering Stalin’s personality cult

in Georgia. In 1935 Beria published a lengthy trea-

tise, On the History of Bolshevik Organizations in

Transcaucasia, which greatly exaggerated Stalin’s

role in the revolutionary movement in the Cauca-

sus before 1917. The book was serialized in the ma-

jor party newspaper, Pravda, and made Beria a

figure of national stature.

When Stalin embarked on his policy of terror-

izing the party and the country through his bloody

purges of the Communist Party apparatus from

1936 through 1938, Beria was a willing accom-

plice. In Georgia alone, thousands perished at the

hands of the secret police, and thousands more were

condemned to prisons and labor camps, as part of

a nationwide Stalinist vendetta against the Soviet

people. Although many party leaders perished in

the purges, Beria emerged unscathed, and in 1938

Stalin rewarded him with the post of head of the

NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs,

as the secret police was then called) in Moscow. Af-

ter carrying out a full-scale purge of the NKVD

leadership, Beria brought in his associates from the

party and police in Georgia to fill the top NKVD

posts, thereby creating an extensive power base in

BERIA, LAVRENTI PAVLOVICH

140

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the NKVD and increasing his political influence in

the Kremlin.

After the German attack on the Soviet Union in

June 1941, Beria, as a deputy Soviet premier, over-

saw the enormous job of evacuating defense indus-

tries from western regions and converting peacetime

industry to war production. He drew upon the

NKVD’s vast forced labor empire, under the Main

Administration of Corrective Labor Colonies, or gu-

lag, to produce weapons and ammunition for the

Red Army, as well as to mine coal and metals and

construct railway lines. The NKVD was also re-

sponsible for internal security, foreign intelligence,

and counterintelligence, and its thousands of bor-

der and internal troops performed rear security

functions. Under Beria’s direct supervision, NKVD

troops deported to Siberia hundreds of thousands of

non-Russian nationals within the Soviet Union who

were suspected of disloyalty to the regime.

By the war’s end, Beria had earned a reputa-

tion as a ruthless but highly effective administra-

tor. Stalin made him a full member of the party’s

ruling Politburo in 1946 and placed him in charge

of developing the Soviet atomic bomb in 1945. Al-

though Beria relinquished his post as head of the

NKVD in early 1946, his protégés were still in

charge, and he continued to oversee the police and

intelligence apparatus as a deputy chairman of the

Council of Ministers. Beria threw himself into work

on the bomb, enlisting top Soviet scientists, ensur-

ing the availability of raw materials like uranium,

and using secret intelligence on atomic bomb pro-

duction in the West. As a result of his efforts, the

Soviets surprised the West by successfully produc-

ing and testing their first atomic bomb (plutonium)

in August 1949.

Although Beria was one of Stalin’s closest ad-

visors, he nonetheless fell victim to Stalin’s intense

paranoia in the early 1950s and suffered a series

of attacks on his fiefdom in Georgia and in the se-

cret police. Had it not been for Stalin’s sudden death

in March 1953, Beria might have been removed

from power altogether. Instead Beria formed an al-

liance with Georgy Malenkov, who became party

first secretary, and took direct control of the police

and intelligence apparatus (known at this time as

the MVD). He also embarked on a series of liberal

initiatives aimed at reversing many of Stalin’s poli-

cies. The changes he introduced were so bold and

far-reaching that they alarmed his colleagues, in

particular Nikita Khrushchev, who aspired to be-

come the Soviet leader. A bitter power struggle en-

sued, and Beria was outmaneuvered by Khrushchev,

who managed to have Beria arrested in June 1953.

Charged with high treason, Beria was executed in

December 1953, along with six others. Although

Beria was best known for being a ruthless police

administrator and a loyal follower of Stalin, archival

materials released in 1990s have made it clear that

Beria’s role went far beyond this and that he was

one of the most influential politicians of the Soviet

period.

See also: GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS; GULAG; PURGES, THE

GREAT; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; STATE SECU-

RITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beria, Sergo. (2001). Beria My Father: Inside Stalin’s Krem-

lin. London: Duckworth.

Knight, Amy. (1993). Beria: Stalin’s First Lieutenant.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

A

MY

K

NIGHT

BERIA, LAVRENTI PAVLOVICH

141

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Lavrenti Beria led Stalin’s purges until Nikita Khrushchev

ordered his execution in 1953. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/

CORBIS

BERING, VITUS JONASSEN

(1681–1741), Russian explorer of Danish descent.

Vitus Bering was the captain-commander of

two expeditions exploring the relative positions of

the coasts of Siberia and North America. Bringing

back the valuable sea otter and other pelts from the

islands of the North Pacific to Siberia, the second

of these expeditions sparked the fur rush that re-

sulted in the Russian conquest of the Commander

and Aleutian Islands and, eventually, all of Alaska,

which was claimed by the Russian Empire until it

was sold to the United States in 1867.

On the first expedition, which sailed in 1728

from the coast of Kamchatka northward well into

the Arctic Ocean, passed through what is now

known as the Bering Strait, and discovered St.

Lawrence Island and the Diomede Islands, Bering

did not sight the coast of North America; but he

was convinced that Asia and North America were

not joined by land. However, when Bering arrived

in St. Petersburg, his critics at the Admiralty found

the results of his exploration inconclusive, and a

second expedition was ordered.

On the second expedition, Bering, commanding

the St. Peter, and his second officer, Alexei Chirikov,

commanding the St. Paul, left the Kamchatka coast

together; but their ships lost sight of each other in

the Pacific Ocean. Consequently, Chirikov’s party

sighted the coast of southeast Alaska (apparently

anchoring off of Cape Addington, around latitude

58º28´), and Bering’s party sighted Mt. St. Elias

several days later, both in July 1741. On the re-

turn voyage the two ships separately sighted and

explored a few of the Aleutian Islands. Chirikov’s

party returned successfully to the Siberian shore,

but Bering’s wrecked on what today is known as

Bering Island, where Bering and nineteen of his men

died. The survivors built a small boat out of the

wreckage and sailed successfully for Kamchatka the

following year.

See also: ALASKA; CHIRIKOV, ALEXEI ILICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fisher, Raymond H. (1977). Bering’s Voyages: Whither and

Why. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Frost, O. W., ed. (1992). Bering and Chirikov: The Ameri-

can Voyages and Their Impact. Anchorage: Alaska His-

torical Society.

I

LYA

V

INKOVETSKY

BERLIN, BATTLE OF See WORLD WAR II.

BERLIN BLOCKADE

In 1945 the victorious World War II allies—the

United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet

Union divided Germany into four occupation

zones, an arrangement that was reflected in the di-

vision of Berlin, as the national capital, into four

sectors. Despite these divisions, the country was

supposed to be treated as a single economic unit by

the Allied Control Council, and an Allied Kom-

mandatura (governing council) was likewise sup-

posed to manage affairs in Berlin.

For a variety of political and economic reasons,

these aims never came close to realization. In Jan-

uary 1948 the Soviets bitterly criticized Anglo-

American moves to combat the economic paralysis

of the country by integrating the Western zones of

Germany into the Western Bloc, and in March the

Soviet delegation walked out of the control coun-

cil, which was never to meet again. This meant that

any chance of a four-power agreement on a des-

perately needed currency reform had vanished. On

March 31 the Soviet military government an-

nounced that for so-called administrative reasons

Soviet officials would henceforth inspect passengers

and baggage on trains from the West bound for

Berlin, which was wholly surrounded by what

would become East Germany—which was at this

point occupied by the Soviet Union—and the Rus-

sians went on to clamp restrictions on freight ser-

vice and river traffic.

On June 18, matters took a new turn when,

abandoning attempts to reach agreement with the

Russians on steps to combat the soaring German

inflation, the Western powers introduced their new

deutsche mark into their zones. Fearing the impact

of the D-mark on their Eastern-zone currency, the

Soviets introduced their own new mark, and on the

same day (June 23) they cut off electricity to the

Western zones and stopped all deliveries of coal,

food, milk, and other supplies. The next day all

traffic, land and water, between West Berlin and

the West came to a stop—the blockade was now

complete—and the Soviets declared that the West-

ern powers no longer had any rights in the ad-

ministration of Berlin.

Rejecting a proposal by General Lucius D. Clay,

the U.S. commander in Germany, to send an armed

BERING, VITUS JONASSEN

142

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY