Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

own exile in 1984. In December 1986, Mikhail Gor-

bachev invited the couple to return to Moscow.

Since Sakharov’s death in 1989, Bonner has

emerged as an outspoken and admired advocate of

democracy in Russia. She joined the defenders of

the Russian parliament during the attempted coup

of August 1991. She withdrew her support of Boris

Yeltsin to protest the war in Chechnya, which she

condemned as a return to totalitarianism. Accept-

ing the 2000 Hannah Arendt Award, Bonner de-

nounced President Vladimir Putin’s unlimited

power, the state’s expanding control over the mass

media, its anti-Semitism, and “the de facto geno-

cide of the Chechen people.”

See also: DISSIDENT MOVEMENT; SAKHAROV, ANDREI

DMITRIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bonner, Elena. (1993). Mothers and Daughters, tr. An-

tonina W. Bouis. New York: Vintage Books.

Bonner, Elena. (2001). “The Remains of Totalitarianism,”

tr. Antonina W. Bouis. New York Review of Books

(March 8, 2001):4–5.

L

ISA

A. K

IRSCHENBAUM

BOOK OF DEGREES

The Book of Degrees of the Royal Genealogy is the first

narrative history of the Russian land. The massive

text filling some 780 manuscript leaves composed

between 1556 and 1563 is one among various am-

bitious literary projects initiated by Metropolitan

Macarius, archbishop of Moscow and head of the

Russian church during the reign of Ivan the Terri-

ble as tsar (1547–1584). Ivan, whose Moscow-

based ancestors had ruthlessly appropriated vast

tracts of territory for their domain, encouraged

writers to craft defenses of his legitimacy. Church-

men responded with a version of the dynasty’s his-

tory conveying their own perspective on the

country’s future course. Conflating chronicles,

saints’ lives, and legends, the book traces the an-

cestry of the Moscow princes in seventeen steps or

degrees from Augustus Caesar and highlights the

noble deeds of each ruler from Grand Prince

Vladimir I (980–1015) to Tsar Ivan. The book’s

purpose was not just to praise the tsar. The larger

aim of its writers was to portray the Muscovite

state as a divinely protected empire whose rulers

would flourish as long as they obeyed God’s com-

mandments, listened to the metropolitans, and sup-

ported the interests of the church.

The Book of Degrees is a work of both historio-

graphical and literary significance. As an exercise

in historiography, its scope and ideology are com-

parable to ninth-century compilations of Frankish

history glorifying the line of the Carolingian rulers.

Like the Carolingian historians, its authors define

their country as the “new Israel.” By so doing, they

legitimize members of a lesser princely clan whose

founders had neither political nor dynastic claims

to power, but who wished to be treated as the

equals of the Byzantine emperors. Elite political cir-

cles accepted the book’s representations as author-

itative proof of the rulers’ imperial descent. The

portraits of the Moscow princes as champions of

their faith commanded no less authority for the

church. Lives, newly composed for the book, de-

picting rulers as saints equal to the apostles or as

wonder-workers, served as testimony for the can-

onization of some Moscow princes and members

of their families.

As a literary work, the Book of Degrees marks a

critical turning point between the predominantly

monastic, fragmentary medieval writings and early

modern narrative prose. Entries culled from annal-

istic compilations (primarily the Nikon, Voskre-

sensk, and Sophia chronicles) and saints’ lives

supplied its building blocks, but the book tran-

scends traditional generic categories and has no sin-

gle literary model. Guided by the priest Andrei

(Metropolitan Afanasy), writers unified their ma-

terials in a systematic way, fashioning fragments

into expansive tales and integrating each tale into

a progressively unfolding story of a tsardom whose

course was steered by divine providence. A preface

sets forth the book’s theological premises in terms

of metaphors serving as figures or types for Rus-

sia’s historical course: the tree (linking the ge-

nealogical tree of the rulers, the Jesse Tree, and the

tree in King Nebuchadnezzar’s prophetic dream);

the ladder (a conflation of Jacob’s ladder and St.

John Climacus’s divine ladder of perfection); and

water (baptism). Readers are directed to a detailed

table of contents, the first of its kind, which sets

forth the book’s unique design and permits indi-

vidual chapters to be swiftly located. Comparison

of the three earliest surviving copies of the text (the

Chudov, Tomsk, and Volkov copies, all dated in the

1560s), shows how original entries were altered,

supplemented, and sometimes shifted from their

initial textual positions by the editors to support

their ideological interests.

BOOK OF DEGREES

163

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The book’s value as an authoritative source and

a statement of the nation’s identity was recognized

by Peter the Great, who in 1716 ordered a synop-

sis to be used for his own planned, but never exe-

cuted, history of Russia. Because of the book’s

importance for the canon, the Russian Academy

commissioned a printed edition in 1771. As the first

cohesive narrative of national history, the Book of

Degrees served as a model for subsequent histories

of Russia and as a sourcebook for mythological and

artistic reconstructions of an idealized past.

See also: CHRONICLES; IVAN IV; MAKARY; MUSCOVY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lenhoff, Gail. (2001). “How the Bones of Plato and Two

Kievan Princes Were Baptized: Notes on the Political

Theology of the‘Stepennaia kniga.’” Welt der Slaven

46:313–330.

Miller, David. (1979). “The Velikie Minei Chetii and the

Stepennaia Kniga of Metropolitan Makarii and

the Origins of Russian National Consciousness.”

Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte 26:

263–282.

G

AIL

L

ENHOFF

BORETSKAYA, MARFA IVANOVNA

Charismatic leader of the Novgorodian resistance

to Muscovite domination in the 1470s.

Marfa Boretskaya (“Marfa Posadnitsa”) was

born into the politically prominent Loshinsky fam-

ily, and married Isaac Andreyevich Boretsky, a

wealthy boyar, who served as mayor (posadnik) of

Novgorod from 1438 to 1439 and in 1453. She

bore two sons, Dmitry and Fyodor. Marfa was

widowed in the 1460s but remained one of the

wealthiest individuals in Novgorod who owned

slaves and sizable estates. Peasants on her lands to

the north of Novgorod engaged in fishing, fur

hunting, livestock raising, and salt boiling. Her

southern estates produced edible grains and flax.

By the middle of the fifteenth century, the re-

lations between the principalities of Moscow and

Novgorod, long strained by chronic disputes over

trade, taxes, and legal jurisdiction, intensified into

overt hostilities. The campaign of 1471 was pur-

portedly undertaken by Ivan III as a response to the

efforts of a party of Novgorodian boyars to ally

themselves with King Casimir of Lithuania. Marfa

is accused in an anonymous essay, preserved in a

single copy of the Sophia First Chronicle, of plot-

ting to marry the Lithuanian nobleman Michael

Olelkovich and rule Novgorod with him under the

sovereignty of the Lithuanian king. The Cathedral

of St. Sophia, seat of the archbishops and emblem

of Novgorodian independence, would have thereby

come under Catholic jurisdiction. No other sources

corroborate these charges against Marfa, although

her son Dmitry, who served as mayor during 1470

and 1471, fought against Moscow in the decisive

Battle of Shelon (July 14, 1471) and was executed

at the order of Ivan III on July 24, 1471. Her other

son Fyodor has also been identified with the pro-

Lithuanian faction in Novgorod. The evidence for

his activity is ambiguous. Nevertheless, he was ar-

rested in 1476 and exiled to Murom, where he died

that same year. Following the final campaign of

1478, Ivan III ordered that Muscovite governors be

introduced into Novgorod and that the landown-

ing elite be evicted and resettled. On February 7,

1478, Marfa was arrested. Her property was con-

fiscated, and she was exiled. The date of her death

is not known.

See also: CATHEDRAL OF ST. SOPHIA, NOVGOROD; IVAN

III; MUSCOVY; NOVGOROD THE GREAT; POSADNIK

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lenhoff, Gail, and Martin, Janet. (2000). “Marfa Boret-

skaia, Posadnitsa of Novgorod: A Reconsideration of

Her Legend and Her Life.” Slavic Review 59(2):

343–368.

G

AIL

L

ENHOFF

BORODINO, BATTLE OF

Borodino was the climactic battle of the Campaign

of 1812, which took place on September 7. Napoleon

had invaded Russia hoping to force a battle near

the frontier, but he pursued when the Russian

armies retreated. His efforts to force a decisive bat-

tle at Smolensk having failed, Napoleon decided to

advance toward Moscow, hoping to force the Russ-

ian army, now under the command of Field Mar-

shal Mikhail Kutuzov, to stand and fight. Pressed

hard by Tsar Alexander to do so, Kutuzov selected

the field near the small village of Borodino, some

seventy miles west of Moscow, for the battle. He

concentrated his force, divided into two armies un-

der the command of Generals Peter Bagration and

BORETSKAYA, MARFA IVANOVNA

164

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, and constructed field for-

tifications in preparation for the fight.

Napoleon eagerly seized upon Kutuzov’s stand

and prepared for battle. Napoleon’s normal prac-

tice would have been to try to turn one of the flanks

of the Russian army, which Kutuzov had fortified.

Mindful of the Russians’ retreat from Smolensk

when he had tried a similar maneuver, Napoleon

rejected this approach in favor of a frontal assault.

The extremely bloody battle that ensued centered

around French attempts to seize and hold Kutu-

zov’s field fortifications, especially the Rayevsky

Redoubt. The battle was a stalemate militarily, al-

though Kutuzov decided to abandon the field dur-

ing the night, continuing his retreat to Moscow.

Borodino was effectively a victory for the Rus-

sians and a turning point in the campaign.

Napoleon sought to destroy the Russian army on

the battlefield and failed. Kutuzov had aimed only

to preserve his army as an effective fighting force,

and he succeeded. Napoleon’s subsequent seizure of

Moscow turned out to be insufficient to overcome

the devastating attrition his army had suffered.

Russia’s losses were, nevertheless, very high, and

included Bagration, wounded on the field, who died

from an infection two weeks later.

See also: FRENCH WAR OF 1812; KUTUZOV, MIKHAIL ILAR-

IONOVICH; NAPOLEON I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Duffy, Christopher. (1973). Borodino and the War of 1812.

New York: Scribner.

F

REDERICK

W. K

AGAN

BOROTBISTY

“Fighters” (full name: Ukrainian Party of Socialist

Revolutionaries, or Communist-Borotbisty), a

short-lived Ukrainian radical socialist party, which

played an important role in the revolutionary

events in Ukraine from 1918 to 1920.

Originally the left wing of the Ukrainian Party

of Socialist Revolutionaries, the Borotbisty, who de-

rived their name from the party’s weekly, Borotba

(Struggle), took control of the Central Committee

in May 1918 and formally dissolved their parent

party. While supporting the Soviet political order,

the Borotbisty advocated Ukrainian autonomy and

the existence of an independent Ukrainian army.

Although the Borotbisty never had a well-developed

organizational structure, the party enjoyed popu-

larity among the poor Ukrainian peasantry. After

Bolshevik troops took control of Ukraine in early

1919, Vladimir Lenin sought to quell peasant dis-

content by including some Borotbisty in the

Ukrainian Soviet government. However, as the

White and Ukrainian nationalist armies forced

the Bolsheviks to retreat, in August 1919 the

Borotbisty, together with the Ukrainian Social

Democratic Party (Independentists), formed the

Ukrainian Communist Party (Borotbisty) and re-

quested admission to the Communist International

as a separate party, without success. Although the

Bolsheviks were uneasy about the Borotbist na-

tional communist stance, the two parties collabo-

rated again during the Red Army offensive in

Ukraine in early 1920. At its height, the Borotbist

membership may have reached fifteen thousand. In

March 1920 the Kremlin pressured the Borotbisty

into dissolving their party and joining the Com-

munist Party of Ukraine, which was the Ukrain-

ian branch of the Bolshevik party. The Borotbist

leadership agreed to the dissolution with the un-

derstanding that this was the only way to preserve

a separate Ukrainian Soviet republic. During the

early 1920s some former Borotbisty, such as Hry-

hory Hrynko and Olexandr Shumsky, occupied im-

portant positions in the Soviet Ukrainian party

leadership and government. Shumsky rose to

prominence after 1923 as a leader of the Ukrainiza-

tion drive, although by the end of the decade he

was criticized for his national deviation. During the

1930s most former Borotbisty, including Panas

Lyubchenko, who had risen to the position of the

head of the republican government, fell victim to

the Stalinist terror. Among the very few survivors

was the celebrated filmmaker Olexandr (Alexander)

Dovzhenko.

See also: UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Borys, Juriij. (1980). The Sovietization of Ukraine,

1917–1923, 2nd ed. Edmonton: Canadian Institute

of Ukrainian Studies Press.

Maistrenko, Ivan. (1954). Borotbism: A Chapter in the His-

tory of Ukrainian Communism, tr. George S. N. Luckyj

with the assistance of Ivan L. Rudnytsky. New York:

Research Program on the USSR.

S

ERHY

Y

EKELCHYK

BOROTBISTY

165

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BOYAR

In the broadest sense, every privileged landowner

could be called a boyar; in a narrower sense, the

term refers to a senior member of a prince’s ret-

inue during the tenth through thirteenth centuries,

and marked the highest court rank during the four-

teenth to seventeenth centuries. The word boyar

probably stems from a Turkic word meaning “rich”

or “distinguished.” Coming from a mixed social and

ethnic background, boyars served a prince, but they

had the right to change their master, and enjoyed

full authority over their private lands.

The relationship between a prince and his bo-

yars varied across the regions. In the twelfth to fif-

teenth centuries, boyars acquired considerable

political power in some principalities ruled by

members of the Ryurikid dynasty and in Novgorod,

where they formed the governing elite. In the

Moscow and Tver principalities, boyars acknowl-

edged the sovereignty of the prince and cultivated

hereditary service relations with him. In the six-

teenth and seventeenth centuries, the rank of bo-

yar became the highest rung in the Muscovite court

hierarchy. It was reserved for members of elite fam-

ilies and was linked with responsible political, mil-

itary, and administrative appointments.

During the seventeenth century, the rank of

boyar became open to more courtiers, due to the

growing size of the court, and it gradually disap-

peared under Peter the Great. It is often assumed

that all boyars were members of the tsar’s coun-

cil, the so-called Boyar Duma, and thereby directed

the political process. This assumption led some his-

torians to assume that Muscovy was a boyar oli-

garchy, where boyars as a social group effectively

ran the state. However, there was always a hier-

archy among the boyars: A few boyars were close

advisors to the tsar, while most acted as high-

ranking servitors of the sovereign.

See also: BOYAR DUMA; MUSCOVY; OKOLNICHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kollmann, Nancy Shields. (1987). Kinship and Politics:

The Making of the Muscovite Political System,

1345–1547. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Poe, Marshall T. (2003). The Russian Elite in the Seven-

teenth Century. 2 vols. Helsinki: Finnish Academy of

Science and Letters.

S

ERGEI

B

OGATYREV

BOYAR DUMA

Boyar Duma is a scholarly term used to describe the

royal council or the upper strata of the ruling elite

in the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries. The

term duma often appears in the sources with the

meaning “advice,” “counsel,” or “a council.” The

influential Romantic historian Nikolai Mikhailovich

Karamzin first used the combination “boyar duma”

(boyarskaya duma), which is never encountered in

the sources.

East Slavic medieval political culture, which re-

lied heavily on scripture, morally obligated every

worthy prince to discuss all weighty matters with

his advisers. In the tenth through fifteenth cen-

turies, princes often discussed political, military,

and administrative issues with other members of

the ruling family, senior members of their armed

retinue, household officials, church leaders, and lo-

cal community leaders. The balance of power be-

tween the ruler and his counselors, as well as the

format and place of their meetings, varied depend-

ing on the circumstances. The Muscovite tsars

adopted the tradition of consulting with their clos-

est entourage, continuing to do so even during pe-

riods of political turmoil, like the Oprichnina and

the Time of Troubles. The 1550 Legal Code refers

to the tradition of consultation, but there were no

written laws regulating the practice of such con-

sultations or limiting the authority of the ruler in

favor of his advisers in judicial terms.

The growing social and administrative com-

plexity of the Muscovite state during the sixteenth

century resulted in the increasing inclusion of dis-

tinguished foreign servitors, high-ranking cavalry-

men, and top-level officials at meetings with the

tsar. The sources describe the practice of consulta-

tions by inconsistently using various terms, in-

cluding duma. From the mid-sixteenth century, the

term blizhnyaya duma (privy duma) appears in the

documents more regularly.

The state school of nineteenth-century Russian

historiography interpreted the tradition of consul-

tations between the ruler and his advisers in for-

mal, legal terms. Historians linked the appearance

of a clearly structured council, which they termed

the boyar duma, with the formation of the court

rank system during the fifteenth and sixteenth cen-

turies. It was assumed that the boyar duma in-

cluded all people holding the upper court ranks of

boyar, okolnichy, counselor cavalryman (dumny

dvoryanin), and counselor secretary (dumny dyak).

BOYAR

166

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Students of law treated the boyar duma as a state

institution by focusing on its functions and com-

petence.

The artificial concept of the boyar duma as a

group of people entitled to sit on the council be-

cause of their status became a basis for various in-

terpretations of the character of the pre-Petrine

state and its politics. Vasily Osipovich Klyuchevsky

pioneered this trend by describing the boyar duma

as “the fly-wheel that set in motion the entire

mechanism of government.” Klyuchevsky’s con-

cept of the boyar duma was developed in the nu-

merous prosopographical and anthropological

studies of the Muscovite elite. Vasily Ivanovich

Sergeyevich questioned the concept of the boyar

duma, observing that there is no documentary ev-

idence of participation of all holders of the upper

court ranks in consultations with the ruler. In line

with this approach, other scholars shift their em-

phasis in the study of the practice of consultations

from the court ranks of the sovereign’s advisers to

the cultural background of this practice.

See also: BOYAR; MUSCOVY; OPRICHNINA; TIME OF TROU-

BLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alef, Gustave. (1967). “Reflections on the Boyar Duma

in the Reign of Ivan III.” The Slavonic and East Euro-

pean Review. 45:76–123.

Bogatyrev, Sergei. (2000). The Sovereign and His Counsel-

lors: Ritualised Consultations in Muscovite Political

Culture, 1350s–1570s. Helsinki: Finnish Academy of

Science and Letters. Also available at <http://ethesis

.helsinki.fi/julkaisut/hum/histo/v/bogatyrev/>.

Kleimola, Ann M. (1985). “Patterns of Duma Recruit-

ment, 1505–1550.” In Essays in Honor of A. A. Zimin,

ed. Daniel Clarke Waugh. Columbus, OH: Slavica

Publishers.

S

ERGEI

B

OGATYREV

BRAZAUSKAS, ALGIRDAS

(b. 1932), Lithuanian political leader.

Algirdas Mykolas Brazauskas emerged as a ma-

jor public figure in the Soviet Union in 1988. A

member of the Central Committee of the Lithuan-

ian Communist Party (LCP) since 1976, a member

of the party’s biuro (equivalent of Politburo) since

1977, and by training an engineer, he had been a

specialist in construction and economic planning.

In 1988 he won note as a party leader who dared

to appear on a public platform with the leaders of

the reformist Movement for Perestroika (Sajudis) in

Lithuania. He became a popular figure, and in Oc-

tober, with the approval of both Moscow and

Sajudis leaders, he replaced Ringaudas Songaila as

the party’s First Secretary.

In his work as First Secretary of the LCP from

1988 to 1990, Brazauskas became a model for re-

formers in other republics throughout the Soviet

Union. He pursued a moderate program for decen-

tralizing the Soviet system, attempting to loosen

Moscow’s control of Lithuania step by step. In this

he had to strike a balance between party leaders in

Moscow who demanded tighter controls in Lithua-

nia and rival Lithuanians who demanded a sharp

BRAZAUSKAS, ALGIRDAS

167

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

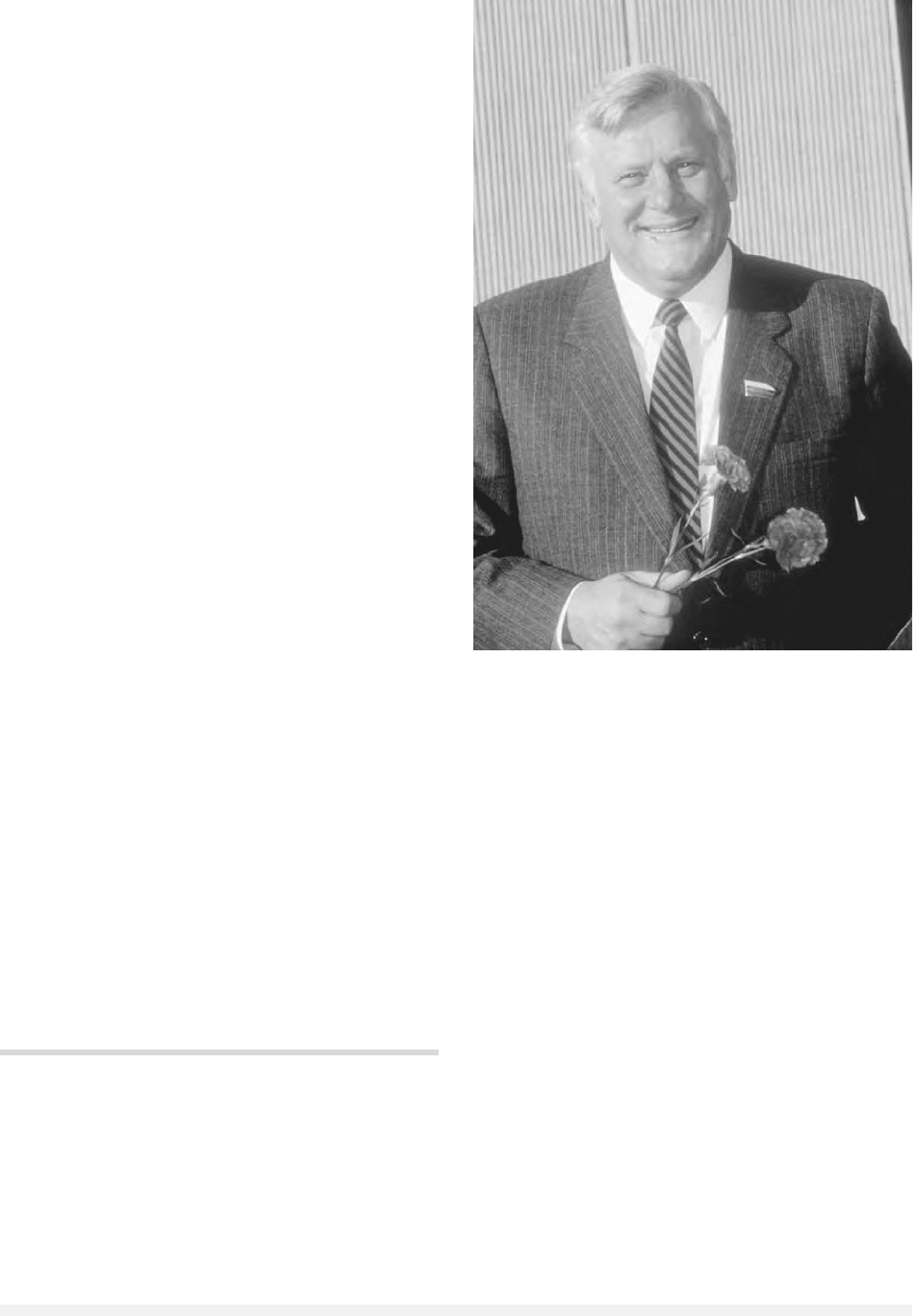

Lithuanian Communist Party leader Algirdas Brazauskas led his

republic’s break from Moscow in 1991. © S

TEPHAN

F

ERRY

/L

IAISON

.

G

ETTY

I

MAGES

.

break with Moscow. He experienced sharp criticism

from both sides for being too lenient toward the

other, yet he remained a popular figure within

Lithuania.

Brazauskas presided over the dismantling of the

Soviet system in Lithuania. In 1988 and 1989, as

First Secretary of the LCP, he held the highest reins

of political power in the republic, although he held

no post in the republic’s government. In December

1989, the Lithuanian parliament ended the Com-

munist Party’s supraconstitutional authority in

the republic. Then the LCP separated itself from the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In January

1990 Brazauskas took the post of president of the

Lithuanian Supreme Council, Lithuania’s parlia-

ment. After new elections in February and March

1990 returned a noncommunist majority, Vytau-

tas Landsbergis became the president of the parlia-

ment, and Brazauskas lost the reins of power,

although he still led the LCP and became deputy

prime minister. The Lithuanian government had

replaced the party as the seat of power in the re-

public.

During the Soviet blockade of Lithuania in

1990, Brazauskas headed a special commission that

planned the most efficient use of Lithuania’s lim-

ited energy resources. In January 1991 he resigned

as deputy prime minister and remained in the op-

position until the Lithuanian Democratic Labor

Party (LDLP), the successor to the LCP in indepen-

dent Lithuania, won the parliamentary elections in

the fall of 1992. After serving briefly as president

of the parliament, in February 1993, he was elected

president of the Republic. As president he could have

no party affiliation, and he accordingly withdrew

from the LDLP. At the conclusion of his five-year

presidential term in 1998, he retired from politics,

but in 2000, still a popular figure, he returned, or-

ganizing a coalition of leftist parties that won a

plurality of seats in parliamentary elections. In

2001 he assumed the post of Lithuanian prime

minister.

See also: LITHUANIA AND LITHUANIANS; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Senn, Alfred Erich. (1995). Gorbachev’s Failure in Lithua-

nia. New York: St. Martin’s.

Vardys, V. Stanley, and Sedaitis, Judith B. (1997).

Lithuania: The Rebel Nation. Boulder, CO: Westview.

A

LFRED

E

RICH

S

ENN

BREST-LITOVSK PEACE

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Soviet Russian

and Imperial Russia, signed in March of 1918, ended

Russia’s involvement in World War I.

In the brief eight months of its existence, the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was labeled an obscene,

shameful, and dictated peace by various members

of the Soviet government that signed it. Since then,

it has been condemned by Western and Soviet his-

torians alike. Under threat of a renewed German

military advance, Russia agreed to give up 780,000

square kilometers of territory, fifty-six million peo-

ple, one-third of its railway network, 73 percent

of its iron ore production, and 89 percent of its coal

supply. What remained of the former Russian

empire now approximated the boundaries of

sixteenth-century Muscovy.

An onerous separate peace with an imperialist

power was far from what the Soviet regime had

hoped to achieve by promulgating Vladimir Lenin’s

Decree on Peace within hours of the October Rev-

olution. This decree, which appealed to all the peo-

ples and governments at war to lay down their

arms in an immediate general peace without an-

nexations or indemnities, was to the Bolsheviks

both a political and a practical necessity. Not only

had Bolshevik promises of peace to war-weary

workers, peasants, and soldiers enabled the party

to come to power—but the Russian army was on

the verge of collapse after years of defeat by Ger-

many. The Allies’ refusal to acknowledge this ap-

peal for a general peace forced the Bolsheviks and

their partners in the new Soviet government, the

Left Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs), to begin nego-

tiations with the Central Powers.

The German-Soviet armistice signed at German

divisional headquarters in Brest-Litovsk in mid-De-

cember was only a short-term triumph for the Bol-

shevik-Left SR government. When negotiations for

a formal treaty commenced at the end of the month,

the German representatives shocked the inexperi-

enced Russians by demanding the cession of areas

already occupied by the German army: Poland,

Lithuania, and western Latvia. Debates raged within

the Bolshevik Party and the government over a suit-

able response. Many Left SRs and a minority of Bol-

sheviks (the Left Communists) argued that Russia

should reject these terms and fight a revolutionary

war against German imperialism. Leon Trotsky

proposed a solution of “neither war nor peace,”

whereas Lenin insisted that the government accept

the German terms to gain a “breathing space” for

BREST-LITOVSK PEACE

168

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

exhausted Russia. Trotsky’s formula prevailed in

Petrograd, but after Trotsky announced it at Brest-

Litovsk, the Germans resumed the war and ad-

vanced toward Petrograd. With Lenin threatening

to resign, the Soviet government reluctantly bowed

to Germany’s demands, which now became even

more punitive, adding the cession of Ukraine, Fin-

land, and all of the Baltic provinces. Soviet repre-

sentatives signed the treaty while demonstratively

refusing to read it; the fourth Soviet Congress of

workers’, soldiers’, and peasants’ deputies ratified

it, signifying the immense popular opposition to

continuing the war. The Left SRs, however, with-

drew from the government in protest.

The Brest-Litovsk peace exacerbated the civil war

that had begun when the Bolshevik Party came to

power in Petrograd in October 1917. The SRs, the

dominant party in the Constituent Assembly dis-

solved by the Soviet government in December 1917,

declared an armed struggle against Germany and the

Bolsheviks in May 1918. In July 1918 the Left SRs

attempted to break the treaty and reignite the war

with Germany by assassinating the German am-

bassador. Various Russian liberal, conservative, and

militarist groups received Allied support for their on-

going war against the Bolshevik regime. Thus the

effects of the Brest-Litovsk peace continued long past

its abrogation by the Soviet government when Ger-

many surrendered to the Allies in November 1918.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; GERMANY, RELATIONS

WITH; WORLD WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Debo, Richard K. (1979). Revolution and Survival: The For-

eign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1917–18. Toronto: Uni-

versity of Toronto Press.

Mawdsley, Evan. (1996). The Russian Civil War. Boston:

Allen and Unwin.

Swain, Geoffrey. (1996) The Origins of the Russian Civil

War. London: Longman.

S

ALLY

A. B

ONIECE

BREZHNEV CONSTITUTION See CONSTITUTION

OF 1977.

BREZHNEV DOCTRINE

Although in its immediate sense a riposte to the

international condemnation of the invasion of

Czechoslovakia in August 1968, the “Brezhnev

Doctrine” was the culmination of the long evolu-

tion of a conception of sovereignty in Soviet ideol-

ogy. At its core was the restatement of a

long-standing insistence on the right of the USSR

to intervene in a satellite’s internal political devel-

opments should there be any reason to fear for the

future of communist rule in that state.

Linked to the name of General Secretary of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),

Leonid Brezhnev, because of its encapsulation in a

speech he read in Warsaw on November 13, 1968,

the doctrine had already been expounded by ideo-

logue Sergei Kovalev in Pravda on September 26,

1968, and, before the invasion, by Soviet com-

mentators critical of the Czechoslovak reforms. It

resembled in most respects the defense of the inva-

sion of Hungary in 1956, and included aspects of

earlier justifications of hegemony dating to the im-

mediate postwar period and the 1930s.

Sovereignty continued to be interpreted in two

regards: first, as the right to demand that the non-

communist world, including organizations such as

the United Nations, respect Soviet hegemony in

Eastern Europe, and second, as permitting the

USSR’s satellites to determine domestic policy only

within the narrow bounds of orthodox Marxism-

Leninism. Any breach of those parameters would

justify military intervention by members of the

Warsaw Pact and the removal even of leaders who

had come to power in the ways that the Soviet po-

litical model would consider legitimate.

The elements of the Brezhnev Doctrine reflect-

ing the exigencies of the late 1960s were the in-

tensified insistence on ideological uniformity in the

face of a steady drift to revisionism in West Euro-

pean communist organizations as well as factions

of ruling parties, and on bloc unity before ventur-

ing a less confrontational coexistence with the

West. Preoccupied with protecting the Soviet sphere

against external challenges and internal fissures,

the Brezhnev Doctrine lacked the ambitious, more

expansionist tone of earlier conceptions of sover-

eignty.

Although not officially overturned until

Mikhail Gorbachev and Eduard Shevardnadze rad-

ically reconceptualized foreign policy in the late

1980s, the future of the Brezhnev Doctrine was al-

ready in doubt when the USSR decided not to in-

vade Poland in December 1980, after the emergence

of the independent trade union, Solidarity. The de-

bates in the Politburo at that time revealed a shift

BREZHNEV DOCTRINE

169

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

in the thinking of even some of its more hawkish

members toward a discourse of Soviet national in-

terest in place of the traditional socialist interna-

tionalism.

See also: BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH; CZECHOSLOVAKIA, IN-

VASION OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jones, Robert A. (1990). The Soviet Concept of “Limited Sov-

ereignty” from Lenin to Gorbachev: The Brehznev Doc-

trine. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Ouimet, M. J. (2000). “National Interest and the Ques-

tion of Soviet Intervention in Poland, 1980–1981:

Interpreting the Collapse of the ‘Brezhnev Doctrine.’”

Slavonic and East European Review 78:710–734.

K

IERAN

W

ILLIAMS

BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH

(1906–1982), leading political figure since the early

1960s, rising to Chairman of the Presidium of the

Supreme Soviet and leader of the ruling Politburo.

Leonid Illich (“Lyonya”) Brezhnev’s rise in So-

viet politics was slow but sure. He was Secretary

of the Central Committee of the Communist Party

from 1964, and after April 1966 he took the office

of General Secretary. His tenure as Chairman of the

Presidium of the Supreme Soviet spanned 1961 to

1963 and from 1977 to 1982. Brezhnev led the rul-

ing Politburo from October 1964, after organizing

the ouster of Nikita S. Khushchev, until his death.

Although Brezhnev’s ultimate successor, the re-

former Mikhail S. Gorbachev, would accuse him of

presiding over an era of stagnation (zastoi, literally

a standstill) in the Soviet Union’s economic devel-

opment and political progress, many Russians re-

member his era as a “golden age” (zolotoi vek) when

living standards steadily improved. This was the

result of his policy of borrowing from the West,

combined with the twofold doubling of world oil

prices and a deliberate decision after 1971 to real-

locate production in favor of consumer products

and foods. Together with Brezhnev’s policy of

vainly trying to achieve military superiority over

every possible combination of foreign rivals and the

growing corruption that he deliberately encour-

aged, the reallocation from industrial goods to con-

sumption and agriculture did in fact lead to a

slowing of the expansion of output that Soviet

leaders deemed to constitute economic growth. It

was this slowdown that lent credibility to Gor-

bachev’s later charge of stagnation.

EARLY CAREER

Brezhnev was born on December 19, 1906, in the

east Ukrainian steel town of Kamenskoe, later re-

named Dneprodzerzhinsk. His grandfather and fa-

ther had migrated there from an agricultural village

in Kursk province, hoping to find work in the local

steel mill. Unlike some of his later Politburo col-

leagues, who joined the Red Army at age fourteen,

Brezhnev evidently played no role in the civil war.

At the time of collectivization, having trained in

Kursk as a land surveyor, he was working in the

Urals where there were few peasant villages to col-

lectivize. In 1931 he abruptly returned to his home

city, where he enrolled in a metallurgical institute,

joined the Communist Party, and accepted low-level

political assignments. Completing his studies in

1935, he trained as a tank officer for one year in

eastern Siberia, only to return again to Dneprodz-

erzhinsk. Often accounted a member of the gener-

ation whose political careers were launched when

the purges of 1937 and 1938 vacated so many high

posts in the Communist Party, Brezhnev received

only minor appointments. By 1939 he was no more

BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH

170

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Leonid Brezhnev waves to the crowd during his visit to the

White House in June 1973. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

than a provincial official, supervising the press and

party schooling, and he transferred the next year

to oversee conversion of the province’s industry to

armaments production. The German invasion in

June 1941 interrupted that uncompleted task, and

within a month Brezhnev had been reassigned to

the regular army as a political officer. With the rank

of colonel, he was charged with keeping track of

party enrollments and organizing the troops. Many

years later, well into his tenure as General Secre-

tary, efforts were made to glorify him as a war

hero, primarily by praising him for regularly vis-

iting the troops at the front; however, he never ac-

tually took much part in combat.

Following the war he was recommended to

Nikita S. Khrushchev, whom Josef Stalin had as-

signed to administer the Ukraine as Communist

Party chief. Khrushchev presumably approved Brezh-

nev’s assignments, first as Party administrator of

the minor Zaporozhe province and later of the more

important Dnepropetrovsk province. Although

Brezhnev would later claim that Stalin himself had

found fault with his work in Dnepropetrovsk,

Khrushchev seems to have regarded Brezhnev as an

effective troubleshooter and persuaded Stalin to put

Brezhnev in charge of the lagging party orga-

nization in neighboring Moldavia in 1950. Brezh-

nev did well enough that he was chosen for

membership in the Central Committee, and then in-

ducted into its Presidium, as the ruling Politburo

was renamed when Stalin decided to greatly expand

its membership. (This expansion, apparently, was

the first move in a plan to purge its senior mem-

bers). But Stalin’s death in March 1953 canceled

whatever plans he may have harbored. In that same

month, Brezhnev was summarily transferred back

to the armed forces, where he spent another year

supervising political lectures, this time in the navy.

Although his postwar political career was tem-

porarily derailed, he had gained the opportunity to

form bonds with a number of officials who would

take over ranking posts when he became General

Secretary. Moreover, his reassignment to the Min-

istry of Defense enabled him to make additional

connections with top military commanders.

Khrushchev’s success in the power struggle un-

leashed by Stalin’s death enabled the First Secretary

to recall Brezhnev from military duty in 1954.

Brezhnev was sent to Kazakhstan to take charge of

selecting the Communist Party officials who would

execute Khrushchev’s plan to turn the so-called

Virgin Lands into a massive producer of grain

crops. Within eighteen months Brezhnev took the

place of his initial superior and successfully led the

transformation of the Virgin Lands. This record,

combined perhaps with Brezhnev’s previous expe-

rience, moved Khrushchev to return Brezhnev to

Moscow in June 1957 as the Communist Party’s

overseer of the new strategic missile program and

other defense activities. While Brezhnev could claim

some credit for the successful launch of Sputnik in

October 1957, he had supervised only the last

stages of that program. He did not manage to pre-

vent the failure of the initial intercontinental bal-

listic missile program, on which Khrushchev had

placed such high hopes. By 1960 Brezhnev had been

shoved aside from overseer of defense matters to

the ceremonial position of Chairman of the Presid-

ium of the Supreme Soviet, where for the first time

he came into extensive contact with officials of for-

eign governments, particularly in what was then

becoming known as the Third World. A stroke suf-

fered by his rival, Frol R. Kozlov, enabled Brezhnev

to return to the more powerful post of Secretary

of the Central Committee, where Khrushchev re-

garded him as his informal number two man.

LEADER OF THE POLITBURO, 1964–1982

It was Brezhnev who organized the insider coup

against his longtime patron, Khrushchev, spending

some six months calling party officials from his

country seat at Zavidovo and delicately sounding

them out on their attitudes toward the removal of

the First Secretary. Khrushchev quickly learned

about the brewing conspiracy; but the failures of

his strategic rocketry, agricultural, and ambitious

housing programs, as well as dissatisfaction with

his reorganizations of Party and government, had

undermined Khrushchev’s authority among Soviet

officials. The Leningrad official, Kozlov, on whom

Khrushchev had relied as a counterweight to

Brezhnev, did not recover from his illness.

Khrushchev was thus unable to mount any effec-

tive resistance when Brezhnev decided to convene

the Central Committee in October 1964 to endorse

Khrushchev’s removal. Brezhnev did not overplay

his own hand, taking only the post of First Secre-

tary for himself and gaining rival Alexei N. Kosy-

gin’s consent to Khrushchev’s ouster by allowing

him to assume Khrushchev’s post of Chairman of

the Council of Ministers (head of the economy).

The contest between Brezhnev and Kosygin for

ascendancy dominated Soviet politics over the next

period. As a dictatorship, the Soviet regime could

not engender the loyalty of the general populace

by allowing citizens to reject candidates for the

BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH

171

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

exercise of power; in other words, it could not let

them vote meaningfully. Thus, how to sustain

popular allegiance was a recurrent topic of discus-

sion among Soviet leaders, both in public and in

private. In the public discussion, Brezhnev took the

conventional Soviet stance that the Communist

Party could count on the allegiance of workers if

it continued its record of heroic accomplishment

manifested in the past by the overthrow of tsarism,

the industrialization of a backward country, and

victory over Germany. He proposed two new heroic

accomplishments that the leadership under his

guidance should pursue: the transformation of So-

viet agriculture through investment in modern

technology, and the building of a military power

second to none. Kosygin, by contrast, argued that

workers would respond to individual incentives in

the form of rewards for hard work. These incen-

tives were to be made available by an increase in

the production of consumer goods, to be achieved

by economic reforms that would decentralize the

decision-making process from Moscow ministries

to local enterprises, and, not coincidentally, freeing

those enterprises from the control of local party

secretaries assigned to supervise industrial activity,

as Brezhnev had done in his early career.

The contest between these competing visions

took almost four years to resolve. Although Kosy-

gin blundered early by interpreting the outcome of

the 1964 U.S. presidential election as a sign of

American restraint in the Vietnam conflict, Brezh-

nev equally blundered by underestimating the dif-

ficulty, or more likely impossibility, of resolving

the Sino-Soviet split. Kosygin sought to protect eco-

nomic reforms similar to the one he proposed for

the Soviet Union, then in progress in the five East

European states controlled by the Soviet Union. In

Czechoslovakia, economic reforms suddenly brought

about political changes at the top of the Commu-

nist Party, impelling its new leader, Alexander

Dubcek, to begin retreating from the party’s mo-

nopoly of power. Brezhnev took advantage of this

emergency to align himself with military com-

manders pressing for the occupation of Czecho-

slovakia and the restoration of an orthodox

communist dictatorship. Introduction of a large So-

viet army enabled Czechoslovak communists,

working under Brezhnev’s personal direction, to re-

move reformers from power, and the replacement

of leaders in Poland and East Germany ended eco-

nomic reforms there as well. By 1971 proponents

of economic reform in Moscow became discouraged

by the evident signs of Kosygin’s inability to pro-

tect adherents of their views, and Brezhnev emerged

for the first time as the clear victor in the Soviet

power struggle.

According to George Breslauer (1982), Brezh-

nev used his victory not only to assert his own pol-

icy priorities but to incorporate selected variants of

Kosygin’s proposals into his own programs, both

at home and abroad. At home he emerged as a

champion of improving standards of living not

only by increasing food supplies but also by ex-

panding the assortment and availability of con-

sumer goods. Abroad he now emerged as the

architect of U.S.-Soviet cooperation under the name

of relaxation of international tensions, known in

the West as the policy of détente. Yet Brezhnev rep-

resented each of these new initiatives as compati-

ble with sustaining his earlier commitments to a

vast expansion of agricultural output and military

might, as well as to continuing support for Third

World governments hostile to the United States.

His rejection of Kosygin’s decentralization propos-

als did nothing to address the growing complexity

of managing an expanding economy from a single

central office.

Although the policy of détente and the dou-

bling of world oil prices in 1973 and again by the

end of the decade made it financially possible for

Brezhnev to juggle the competing demands of agri-

culture, defense, and the consumer sector, there

was not enough left over to sustain industrial ex-

pansion, which slowed markedly in the last years

of his leadership. As the crucial criterion by which

communist officials had become accustomed to

judging their own success, the slowdown in in-

dustrial expansion undermined the self-confidence

of the Soviet elite. Brezhnev’s policy of cadre sta-

bility—gaining support from Communist Party of-

ficials by securing them in their positions—

developed a gerontocracy that blocked the upward

career mobility by which the loyalty of officials

had been purchased since Stalin instituted this

arrangement in the 1930s. Brezhnev therefore

made opportunities available for corruption, bribe-

taking, and misuse of official position at all levels

of the government, appointing his son-in-law as

chief of the national criminal police to assure that

these activities would not be investigated. His en-

couragement of corruption rewarded officials dur-

ing his lifetime, but it also further sapped their

collective morale, and made some of them respon-

sive to the proposals for change by his ultimate

successor, Mikhail Gorbachev.

In foreign policy his initially successful policy

of détente foundered as his military buildup lent

BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH

172

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY