Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

funding from foreign foundations and appealing to

world opinion rather than cultivating local mem-

berships. Among the most influential of these are

the Center for Russian Environmental Policy under

the direction of Alexei Yablokov (former environ-

mental adviser to Boris Yeltsin), the St. Petersburg

Clean Baltic Coalition, the Baikal Environmental

Wave, the Russian branch of the Worldwide Fund

for Wildlife (WWF), and Green Cross International,

of which Mikhail Gorbachev became president in

1993. A few radical environmental groups emerged

during the early 1990s, notably the Rainbow Keep-

ers and Eco-Defense, which promote more funda-

mental societal change. Beginning during the late

1990s, there was a revival of grassroots activism

on local issues of air and water quality, animal wel-

fare, nature education, and protection of sacred

lands. Such efforts rely on local members and on

the resources of preexisting (i.e., Soviet-era) insti-

tutions and networks, and they tend to cultivate

local bureaucrats and political leaders.

See also: CHERNOBYL; RUSSIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY;

THICK JOURNALS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goldman, Marshall I. (1972). Environmental Pollution in

the Soviet Union: The Spoils of Progress. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

Henry, Laura. (2002). “Two Paths to a Greener Future:

Environmentalism and Civil Society Development in

Russia.” Demokratizatsiya 10(2):184–206.

Komarov, Boris (Ze’ev Wolfson). (1978). The Destruction

of Nature in the Soviet Union. London: Pluto Press.

Pryde, Philip R. (1991). Environmental Management in the

Soviet Union. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Stewart, John Massey, ed. (1992). The Soviet Environment:

Problems, Policies and Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Weiner, Douglas R. (1988). Models of Nature: Ecology,

Conservation, and Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Weiner, Douglas R. (1999). A Little Corner of Freedom:

Russian Nature Protection from Stalin to Gorbachev.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Yanitsky, Oleg. (1999). “The Environmental Movement

in a Hostile Context: The Case of Russia.” Interna-

tional Sociology 14(2):157–172.

Ziegler, Charles E. (1987). Environmental Policy in the

USSR. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

R

ACHEL

M

AY

EPARKHYA See DIOCESE.

EPISCOPATE

The episcopate of the Russian Orthodox Church

(Moscow Patriarchate) encompasses the whole body

of bishops who govern dioceses and supervise

clergy, as well as perform and administer church

sacraments. The episcopate is drawn exclusively

from the ranks of the celibate “black” clergy, al-

though widowers who take monastic vows may

also be recruited. The patriarch of Moscow and All

Russia and the ecclesiastical ranks below him—met-

ropolitans, archbishops, bishops, and hegumens—

comprise the leadership of the church. The patriarch

and metropolitans hold power over the church hi-

erarchy and carry on the debates that produce (or

resist) change within the church.

Eastern Orthodoxy is widely believed to have

been introduced in Kievan Rus in 988

C

.

E

. At first

the Russian church was governed by metropolitans

appointed by the patriarchate of Constantinople

from the Greek clergy active in the Rus lands. When

the Russian church gained its independence from

Constantinople in 1448, Metropolitan Jonas, resi-

dent in the outpost of Moscow, was given the title

of metropolitan of Moscow and All Russia. Metro-

politan Job of Moscow became the first Russian pa-

triarch in 1589, thereby establishing the Russian

church’s independence from Greek Orthodoxy.

The close link between ecclesiastical and tem-

poral authorities in Russia reflected Byzantine cul-

tural influence. The alliance between church and

state ended with the reign of Peter the Great (1682-

1725). Seeing the Russian Orthodox Church as a

conservative body frustrating his attempts to mod-

ernize the empire, he did not appoint a successor

when Patriarch Adrian died in 1700 and in his place

appointed a bishop more open to Westernization.

In 1721 Peter abolished the patriarchate and ap-

pointed a collegial board of bishops, the Holy

Synod, to replace it. This body was subject to civil

authority and similar in both structure and status

to other departments of the state.

The reigns of Peter III (1762-1763) and Cather-

ine II (1762-1796) brought Peter the Great’s re-

forms to their logical conclusion, confiscating the

church’s properties and subjecting it administra-

tively to the state. A (lay) over-procurator was

EPISCOPATE

463

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

empowered to supervise the church, appointing im-

portant officials and directing the activities of the

Holy Synod. The full extent of the over–procurator’s

control was realized under the conservative Kon-

stantin Pobedonostsev (1880–1905), who kept the

episcopate in submission.

The calls for reform during Tsar Nicholas II’s

reign (1894–1917) included demands for an end to

state control of the church. By and large the bish-

ops were dissatisfied with the Holy Synod and the

role played by the over-procurator. Nicholas II re-

sponded by granting the church greater indepen-

dence in 1905 and agreeing to allow a council that

church officials anticipated would result in the lib-

eralization of the church. In 1917, when the coun-

cil was finally convened, it called for the restoration

of the patriarchate and church sovereignty, and de-

centralization of church administration.

The October Revolution brought a radical change

in the status of the episcopate. The Bolsheviks im-

plemented a policy of unequivocal hostility toward

Orthodoxy, fueled by the atheism of Marxist–

Leninist doctrine and also by the church’s legacy as

defender of the imperial government. Bishops were

a special target and, along with priests, monks,

nuns, and laypersons, were persecuted on any pre-

text. Nearly the entire episcopate was executed or

died in labor camps. In 1939 only four bishops re-

mained free. Throughout the Soviet period, the

number of bishops rose and fell according to the

whims of the communist regime’s religious policy.

While initially the episcopate was hostile to the

Bolsheviks, the sustained persecution of believers

made it apparent that if the church wished to sur-

vive as an institution it would have to change its

position. In 1927 Patriarch Sergei, speaking for the

church, issued a “Declaration of Loyalty” to the So-

viet Motherland, “whose joys and successes are our

joys and successes, and whose setbacks are our set-

backs” This capitulation began one of the most con-

troversial chapters in the episcopate’s history. The

Soviet authorities appointed all of the church’s im-

portant officials and unseated any who challenged

their rule. The regime and the church leadership

worked together to root out schismatic groups and

sects. Meanwhile, prelates assured the international

community that accusations of religious persecution

were merely anti-Soviet propaganda.

The reinstitutionalization of the Orthodox

Church during the perestroika years marked the

end of the episcopate’s subordination to the athe-

ist regime. The Orthodox Church figured promi-

nently in discussions about the renewal and re-

generation of Soviet society. In post-communist

Russia, the patriarch and other Orthodox digni-

taries became high-profile public figures. The epis-

copate has influenced political debate, most notably

the deliberations on new religious legislation dur-

ing the mid- and late 1990s. The end of commu-

nism also produced new challenges for the epis-

copate. Schismatic movements, competition from

other faiths, and reformist priests have created di-

visions and threatened the Orthodox Church’s pre-

eminence.

See also: CHRISTIANIZATION; JOB, PATRIARCH; KIEVAN

RUS; ORTHODOXY; PATRIARCHATE RUSSIAN ORTHO-

DOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ellis, Jane. (1986). The Russian Orthodox Church: A Con-

temporary History. London: Routledge.

Gudziak, Borys A. (1998). Crisis and Reform: The Kyivan

Metropolitanate, the Patriarchate of Constantinople,

and the Genesis of the Union of Brest. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Hosking, Geoffrey. (1998). Russia: People and Empire,

1552–1917. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Knox, Zoe. (2003). “The Symphonic Ideal: The Moscow

Patriarchate’s Post-Soviet Leadership.” Europe–Asia

Studies 55:575–596.

Z

OE

K

NOX

ESTATE See SOSLOVIE.

ESTONIA AND ESTONIANS

Estonia covers the area from 57.40° to 59.40° N

and 21.50° to 28.12° E, bordered on the north by

the Gulf of Finland, on the east by Russia, on the

south by Latvia, and on the west by the Baltic Sea.

Its area is 17,462 square miles (45,222 square kilo-

meters), and its capital is Tallinn (population

400,378 in 2000). The estimated population of Es-

tonia in 2003 was 1,356,000, including 351,178

ethnic Russians. Outside the country there are

ESTATE

464

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

approximately 160,000 Estonians, among them

46,390 in the Russian Federation.

The Estonian constitution separates church and

state. According to the census of 2000, there were

152,237 Lutherans (of whom 145,718 were Esto-

nians), 143,557 Orthodox Chrsistians (104,698 of

them Russians), 6,009 Baptists, and 5,745 Roman

Catholics. Non-Christian religions included Islam

(1,387 Muslims), Estonian native religion (1,058),

Buddhism (622), and Judaism (257).

The Estonian language belongs to the Baltic-

Finnic branch of the Finno-Ugric languages of the

Uralic language family. The first book in Estonian

was printed in 1525. According to the 2000 cen-

sus, 99.1 percent of Estonians considered Estonian

their mother tongue.

The Estonian constitution, adopted in 1992,

vests political supremacy in a unicameral parlia-

ment, the Riigikogu, with 101 members elected by

proportional representation for four-year terms.

The Riigikogu makes all major political decisions,

such as enacting legislation, electing the president

and prime minister, during the longevity of gov-

ernments, preparing the state budget, and making

treaties with foreign countries. The head of state

and supreme commander of the armed forces is the

president, who is elected to not more than two con-

secutive five-year terms. The president is elected by

a two-thirds majority of the Riigikogu. If no can-

didate receives two-thirds, the process moves to the

Electoral College, made up of the members of Ri-

igikogu and representatives of local government.

The Estonian economy is mainly industrial.

The dominant branches are the food, timber, tex-

tile, and clothing industries, but transportation,

wholesaling, retailing, and real estate are also sig-

nificant. The importance of agriculture is dimin-

ishing, but historically it was the most important

branch of Estonian economy. The main fields of

agriculture are cattle and pig keeping and raising

of crops and potatoes. In 2001 there were 85,300

agricultural households in Estonia.

The earliest settlements in Estonia date to the

Mesolithic Age (9000

B

.

C

.

E

.). Its Neolithic Age con-

tinued from 4900

B

.

C

.

E

. to 1800

B

.

C

.

E

., its Bronze

Age until 500

B

.

C

.

E

., and the Iron Age until the be-

ginning of the thirteenth century. After a struggle

for independence between 1208 and 1227, Estonia

was conquered by the Danes and Germans. It ter-

ritory was divided between Denmark (Tallinn and

northern Estonia), the Teutonic Knights (south-

western Estonia), and the bishoprics of Saare-Lääne

(western Estonia and the islands) and Tartu (south-

eastern Estonia). In 1346 the Danish crown sold

northern Estonia to the Teutonic Order. During the

Livonian Wars (1558–1583), Ivan the Terrible in-

vaded Old Livonia (now Estonia and Latvia). The

largest of the Estonian islands, Saaremaa, became

the property of the Danish king, northern Estonia

capitulated to Sweden, and the southern part of

present-day Estonia to Poland. By the Truce of Alt-

mark (1629) Poland surrendered southern Estonia

to Sweden. In 1645 Sweden obtained Saaremaa

from Denmark. At the beginning of the eighteenth

century, Peter the Great of Russia defeated Charles

XII of Sweden in the Great Northern War, and, by

the Peace of Nystad (1721), obtained Estonia, which

he had occupied in 1710. Between 1816 and 1819,

serfdom was abolished in Estonia. This led to an

improved economic situation and the cultural de-

velopment of the Estonian people, who constituted

most of the class of peasants by that time. Between

1860 and 1880 there was an Estonian national

awakening, the beginning of a modern Estonian na-

tion. Estonians began to publish national newspa-

pers, organized all-Estonian song festivals, and

developed literature, education, and the arts. In the

late nineteenth century, a wave of Russification,

ESTONIA AND ESTONIANS

465

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Munamagi

1,043 ft.

318 m.

Kolkas Rags

Gulf of Finland

Gulf

of

Riga

I

r

v

e

s

a

u

r

u

m

s

Chudskoye

Ozero

Pskovskoye

Ozero

Võrts

Järv

B

a

l

t

i

c

S

e

a

P

a

r

n

u

V

o

h

a

n

d

u

P

e

d

j

a

N

a

r

v

a

K

u

n

d

a

¯

Ruhnu

Kihnu

Saaremaa

Vilsandi Saar

Hiiumaa

Vormsi

Muhu

Paldiski

Maardu

Keila

Kehra

Tapa

Kunda

Rakvere

Mustvee

Püssi

Sillamäe

Jõhvi

Türi

Paide

Rapla

Haapsalu

Kärdla

Virtsu

Orissaare

Elva

Pskov

Liepaja

Ventspils

Voru

Valga

Tõrva

Tartu

Kohtla-

Järve

Narva

Pärnu

Tallinn

¯

Kotka

RUSSIA

FINLAND

LATVIA

LITHUANIA

Estonia

W

S

N

E

ESTONIA

100 Miles

0

0

100 Kilometers

50

50

Estonia, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

initiated by the tsarist government, reached Esto-

nia. Estonian politicians demanded radical political

changes during the revolution of 1905, but the

Russian authorities responded with repressions. Af-

ter the February Revolution in Russia, the Provi-

sional Government allowed Estonia’s territorial

unification as one province (until then it had been

divided into the Estonia and Livonia guberniyas).

On February 24, 1918, Estonia declared its in-

dependence. Its War of Independence (1918–1920)

concluded with Soviet Russia recognizing its inde-

pendence in the Tartu Peace Treaty signed on Feb-

ruary 2, 1920. In 1939 the Nazi-Soviet Pact (also

known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) assigned

Estonia to the Soviet sphere of influence. Soviet

troops occupied the Estonian Republic in June 1940

and incorporated it into the USSR. During the first

year of the Soviet regime, 2,000 Estonian citizens

were executed and 19,000 deported, more than

half of them in June 1941. During the period

1941–1944, Estonia was occupied by Germany.

At the end of World War II there were nearly

100,000 Estonian refugees in the West. An anti-

Soviet guerilla movement was active from 1944

through the mid-1950s. In March 1949, during the

collectivization campaign, more than 20,000 Esto-

nians were deported to Siberia. Throughout the So-

viet period, a directed migration of population from

Russia was conducted, mainly into Tallinn and the

industrial region of northeastern Estonia. The

1970s and the first half of the 1980s comprised the

most intense period of Russification. At the end of

the 1980s, a new wave of national awakening be-

gan in Estonia, accompanied by political struggle

to regain independence. On August 20, 1991, Es-

tonia proclaimed its independence from the Soviet

Union, and in September 1991 it was admitted to

the United Nations.

See also: GREAT NORTHERN WAR; LATVIA AND LATVIANS;

LIVONIAN WAR; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NA-

TIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clemens, Walter C., Jr. (1991). Baltic Independence and

Russian Empire. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Pettai, Vello A. (1996). “Estonia.” In Estonia, Latvia, and

Lithuania: Country Studies, ed. Walter R. Iwaskiw.

Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library

of Congress.

Raun, Toivo U. (2001). Estonia and the Estonians. Stan-

ford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Taagepera, Rein. (1993). Estonia: Return to Independence.

Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

A

RT

L

EETE

ETHIOPIAN CIVIL WAR

The Ethiopian civil war, between the Ethiopian gov-

ernment and nationalists from Eritrea (an Ethiopian

province along the Red Sea), has raged off and on

and has been tightly interconnected with Ethiopia’s

internal political problems and conflict with neigh-

boring Somalia. In the 1880s Italy captured Eritrea.

By 1952 Ethiopia regained control, but eight years

later, in 1961, Eritrean nationalists demanded in-

dependence from Ethiopia. When the Ethiopian

government rejected this demand, civil war erupted.

The civil war was a symptom of profound

changes within Ethiopia, involving a confrontation

between traditional and modern forces that

changed the nature of the Ethiopian state. The last

fourteen years of Haile Selassie’s reign (1960–1974)

witnessed growing opposition to his regime.

Ethiopians demanded better living conditions for

the poor and an end to government corruption. In

1972 and 1973, severe drought led to famine in the

northeastern part of Ethiopia. Haile Selassie’s crit-

ics claimed that the government ignored victims of

the famine. In 1974 Ethiopian military leaders un-

der Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile-Mariam

seized the government and removed Haile Selassie

from power.

The Ogaden region of southeastern Ethiopia

also became a trouble spot, beginning in the 1960s.

The government of neighboring Somalia claimed

the region, which the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik

had conquered in the 1890s. Many Somali people

had always lived there, and they revolted against

Ethiopian rule. In the 1970s fighting broke out be-

tween Ethiopia and Somalia over the Ogaden re-

gion.

Until then, Ethiopia had enjoyed U.S. support,

while the Soviet Union had sided with its rival, So-

malia. In fact, in the space of just four years

(1974–1978), the USSR concluded a Treaty of

Friendship and Cooperation with Somalia, Ethiopia

experienced a revolution in 1974, and the Soviet

Union dramatically shifted massive support from

Somalia to Ethiopia and then played a key part in

ETHIOPIAN CIVIL WAR

466

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the military defeat of its former ally in the Ogaden

conflict of 1977–1978. During the conflict, about

fifty Soviet ships passed through the Suez Canal to

the port of Assab to unload fighter aircraft, tanks,

artillery, and munitions—an estimated 60,000 tons

of hardware—for delivery to Mengistu’s regime.

After the 1974 revolution, the new military

government under Mengistu adopted socialist poli-

cies and established close relations with the Soviet

Union. The government began large-scale land re-

form, breaking up huge estates of the former no-

bility. The government claimed ownership of this

land and turned it into farmland. But the military

leaders also killed many of their Ethiopian oppo-

nents, further alienating former U.S. supporters

who opposed the human rights abuses.

Eritrean rebels stepped up their separatist ef-

forts after the 1974 revolution. Mengistu’s regime

invaded rebel-held Eritrea several times, but failed

to regain control. Ethiopia’s conflict with Eritrea

also had a strong East-West dimension. The Soviet

Union, along with some Arab states, advocated

complete independence for Eritrea. In a speech to

the United Nations, the Soviet delegate rejected the

federalist compromise solution advocated by the

United States, claiming that the Eritrean people had

not given their consent. Soviet scholars also backed

Ethiopia’s claim to Eritrea on both historical and

economic grounds. They noted that the Soviet

Union had favored Ethiopian access to the Eritrean

port of Assab as early as 1946. Despite an influx

of Soviet military aid after 1977, Mengistu’s coun-

terinsurgency effort in Eritrea progressed slowly.

Talks between the two sides continued well into the

1980s. The war ended in 1991 with Eritrea’s inde-

pendence; however, conflict between the two coun-

tries persisted for more than a decade. In June 2000,

the two countries signed a cessation of hostilities

agreement, and a United Nations peacekeeping

force of more than 4,300 military personnel was

dispatched later that year.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albright, David E. (1980). Communism in Africa. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

Feuchtwanger, E. J., and Nailor, Peter. (1981). The Soviet

Union and the Third World. New York: St. Martin’s-

Press.

Human Rights Watch Organization. (2003). Eritrea and

Ethiopia: The Horn of Africa War: Mass Expulsions and

the Nationality Issue, June 1998–April 2002. New

York: Human Rights Watch.

Korn, David A. (1986). Ethiopia, the United States, and the

Soviet Union. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Univer-

sity Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

ETHNOGRAPHY, RUSSIAN AND SOVIET

Russian ethnography took shape as a distinct field

of scholarship in the mid-nineteenth century, but

the creation of ethnographic knowledge in Russia

dates back at least to Kievan Rus. The Russian Pri-

mary Chronicle abounds with information about

Slavic tribes and neighboring peoples, while later

medieval and early modern Russian writings pro-

vide accounts of the peoples of Siberia and the Far

North. It was only in the period following the re-

forms of Peter the Great (d. 1725), however, that

the population of the empire was studied using ex-

plicitly scientific methods. In the 1730s Vasily

Tatishchev disseminated Russia’s first ethnographic

survey, thereby legitimizing the notion of peoples

and their cultures as objects of systematic scientific

inquiry. From the 1730s to the 1770s the Russian

Academy of Sciences sponsored two major expedi-

tions dedicated to the study of the empire. Led by

Gerhard Friedrich Miller and Peter Pallas, the aca-

demic expeditions covered a vast expanse from

Siberia to the Caucasus to the Far North and, draw-

ing on the talents of numerous dedicated scholars,

amassed an enormous amount of ethnographic in-

formation and physical artifacts. But for all their

achievements as ethnographers, eighteenth-century

scholars viewed the study of cultural diversity as

merely one component of a broadly defined nat-

ural science.

FOLKLORE AND THE SEARCH

FOR NATIONAL IDENTITY

During the last decades of the eighteenth century

Russian scholars began to turn their attention to

folklore. Publishers of folk songs in the 1790s, such

as Mikhail Popov and Nikolai Lvov, claimed that

their collections were of value not only for enter-

tainment but also as relics of ancient times and as

sources of insight into the national spirit. By 1820

several significant folklore collections had appeared,

including the Kirsha Danilov collection of folk epics,

and the first efforts to collect folklore among the

common people had begun under the patronage of

Count Nikolai Rumiantsev. As Russian intellectu-

als struggled in the 1820s to define narodnost, the

ETHNOGRAPHY, RUSSIAN AND SOVIET

467

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

national spirit, they turned increasingly to folklore

for inspiration. Peter Kireyevsky assembled the

largest folk song collection, drawing on an exten-

sive network of contributors, including Alexander

Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, and other prominent writ-

ers. While Kireyevsky’s songs were not published

during his lifetime, other folklorists in the 1830s

and 1840s, such as Ivan Snegarev, Ivan Sakharov,

Vladimir Dal, and Alexander Tereshchenko, put out

collections that enjoyed considerable success with

the reading public despite their often dubious au-

thenticity.

ETHNOGRAPHY AS A DISCIPLINE

Geographic exploration and folklore, the two main

branches of ethnographic research up to this point,

came together in the Ethnographic Division of the

Russian Geographical Society, the founding of

which in 1845 marks the emergence of ethnogra-

phy as a distinct academic field. In its first years

the society considered two well-developed concep-

tions of ethnography as a scholarly discipline. The

eminent scientist Karl Ernst von Baer proposed that

the Ethnographic Division study primarily the

smaller and less-developed populations of the em-

ETHNOGRAPHY, RUSSIAN AND SOVIET

468

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

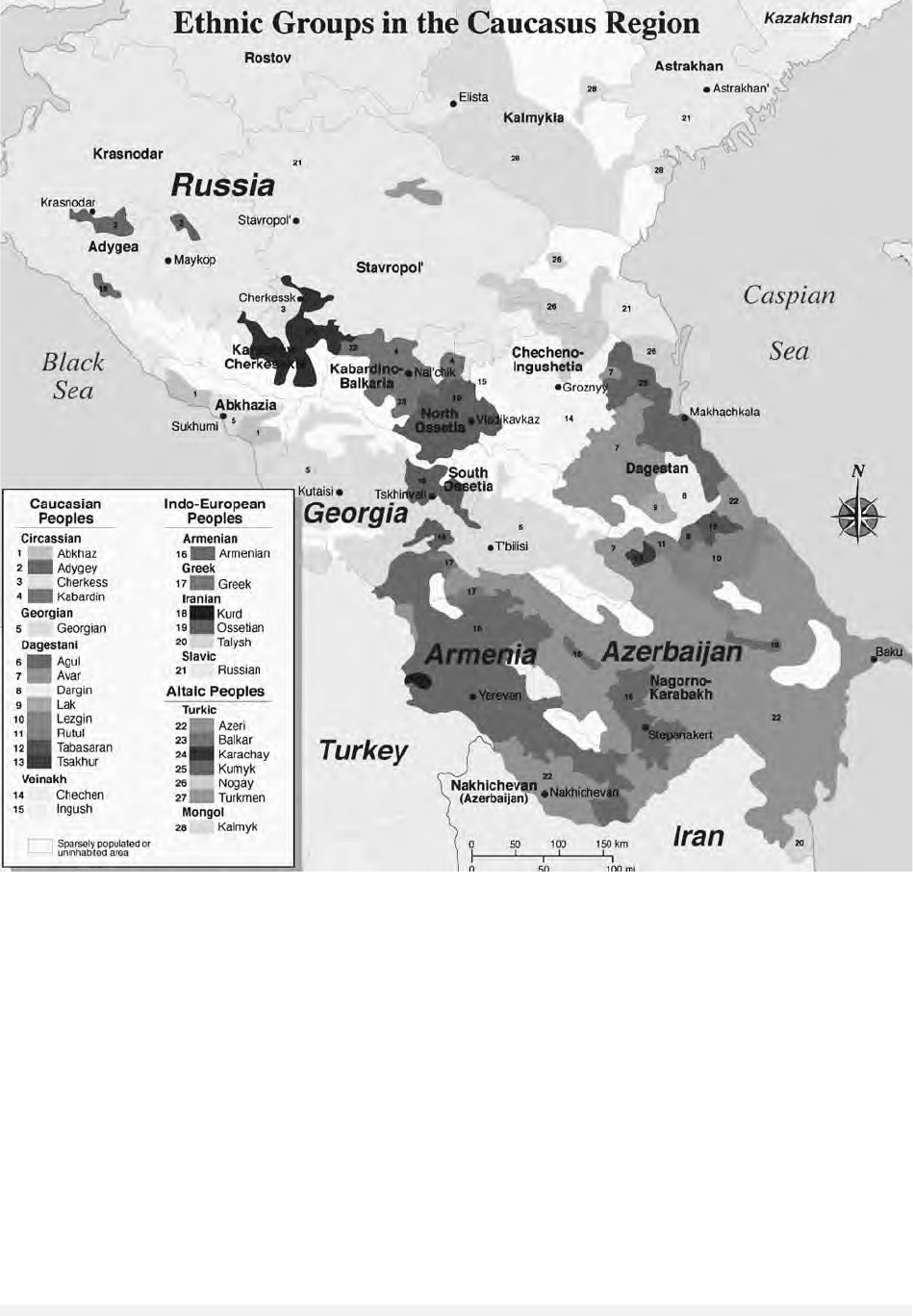

The Caucasus region is one of the most ethnically diverse areas in the former Russian empire. © MAPS.

COM

/CORBIS

pire, paying particular attention to the role of

environment and heredity. In contrast, Nikolai

Nadezhdin, a well-known editor, literary critic, and

historian, advocated a science of nationality dedi-

cated to describing the full range of cultural, intel-

lectual, and physical features that make up national

identity. First priority, he felt, should go to the

study of the Russian people. After replacing Baer

as chair of the Ethnographic Division in 1847,

Nadezhdin launched a major survey of the Rus-

sian provinces based on a specially designed ques-

tionnaire. The materials generated were published

by the Ethnographic Division in its journal Ethno-

graphic Anthology (Etnografichesky sbornik), the first

periodical in Russian specifically devoted to ethnog-

raphy, and were used for several major collections

of Russian folklore.

In the 1860s a second major center of ethno-

graphic study arose in Moscow with the founding

of the Society of Friends of Natural History, An-

thropology, and Ethnography (known by its Russ-

ian initials, OLEAE). Dedicated explicitly to the

popularization of science, the society inaugurated

its ethnographic endeavors in 1867 with a major

exhibition representing most of the peoples of the

Russian Empire as well as neighboring Slavic na-

tionalities.

During the 1860s and 1870s ethnographic

studies in Russia flourished and diversified. The

Russian Geographical Society in St. Petersburg and

OLEAE in Moscow sponsored expeditions, subsi-

dized the work of provincial scholars, and published

major ethnographic works. At the same time re-

gional schools began to take root, particularly in

Siberia and Ukraine. Landmark collections appeared

in folklore studies, such as Alexander Afanasev’s

folktales, Vladimir Dal’s proverbs and dictionary,

Kireevsky’s folksongs, and Pavel Rybnikov’s folk

epics (byliny). As new texts accumulated, scholars

such as Fedor Buslaev, Alexander Veselovsky,

Vsevolod Miller, and Alexander Pypin developed so-

phisticated methods of analysis that drew on Eu-

ropean comparative philology, setting in place a

distinctive tradition of Russian folklore studies.

The abolition of serfdom in 1861 sparked an

upsurge of interest in peasant life and customary

law. Nikolai Kalachov, Peter Efimenko, Alexandra

Efimenko, and S.V. Pakhman undertook major

studies of customary law among Russian and non-

Russian peasants, while the Russian Geographical

Society formed a special commission on the topic

in the 1870s and generated data through the dis-

semination of a large survey. The vast literature on

customary law was cataloged and summarized by

Yevgeny Iakushkin in a three-volume bibliography.

Alongside the study of customary law, ethnogra-

phers probed peasant social organization, with em-

phasis on the redistributional land commune.

THE PROFESSIONALIZATION

OF ETHNOGRAPHY

While ethnographers in the 1860s through the

1880s produced an enormous quantity of impor-

tant work, the boundaries and methods of ethnog-

raphy as a discipline remained fluid and ill-defined.

Not only did ethnography overlap with a number

of other pursuits, such as philology, history, legal

studies, and belle-lettres, but the field itself was dis-

tinctly under-theorized—descriptive studies were

pursued as an end in themselves, with little attempt

to integrate the data generated into broader theo-

retical schemes. During the 1880s and 1890s, how-

ever, ethnography began to establish itself on a

more solid academic footing. New journals ap-

peared, most notably the Ethnographic Review (Etno-

graficheskoe obozrenie) distributed by OLEAE and

the Russian Geographical Society’s Living Antiquity

(Zhivaia starina). Instruction in ethnography, al-

beit rather haphazard, began to appear at the ma-

jor universities. Museum ethnography also moved

forward with the transformation, under the direc-

tion of Vasily Radlov, of the old Kunstkamara in

St. Petersburg into a Museum of Anthropology and

Ethnography, and the founding around the turn of

the twentieth century of the Ethnographic Division

of the Russian Museum.

By the 1890s theoretical influences from West-

ern Europe, particularly anthropological evolu-

tionism, had begun to exert a stronger influence on

Russian scholars. Nikolai Kharuzin, a prominent

young Moscow ethnographer, made evolutionist

theory the centerpiece of his textbook on ethnog-

raphy, the first of its kind in Russia. In the field,

Lev Shternberg, a political exile turned ethnogra-

pher, claimed to find among the Giliak people

(Nivkhi) of Sakhalin Island confirmation of the

practice of group marriage as postulated by the

evolutionist theorist Henry Lewis Morgan and

Friedrich Engels. With the growing theoretical in-

fluence of Western anthropology came increased

contacts. Shternberg and his fellow exiles Vladimir

Bogoraz-Tan and Vladimir Iokhelson participated

in the Jessup North Pacific Expedition sponsored by

the American Museum of Natural History in New

York under the direction of Franz Boas. Upon his

return from exile, Shternberg was hired by Radlov

ETHNOGRAPHY, RUSSIAN AND SOVIET

469

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography

in St. Petersburg, and made use of his friendship

with Boas to cultivate a fruitful collaboration with

the museum in New York.

SOVIET PERIOD

The Russian Revolution presented both opportuni-

ties and dangers for the field of ethnography. On

the eve of the February Revolution of 1917 a Com-

mission for the Study of the Ethnic Composition

of the Borderlands (KIPS) was established under the

auspices of the Academy of Sciences. While initially

established to aid the Russian effort in World War

I, KIPS found a niche under the Bolshevik regime,

which welcomed the collaboration of ethnogra-

phers in coping with the immense ethnic diversity

of the Soviet state. During the 1920s KIPS ethno-

graphers played a major role in defining the ethnic

composition of the Soviet Union. The 1920s also

saw the emergence of the first comprehensive pro-

grams of professional training in ethnography at

Leningrad and Moscow universities.

In the late 1920s, however, “bourgeois” ethnog-

raphy became a target of attack by radical Marx-

ist activists. After a dramatic confrontation in April

1929, key ethnographic institutions were disbanded

and ethnography itself was reclassified as a sub-

field of history devoted exclusively to the study of

prehistoric peoples. Nevertheless ethnographers

such as Sergei Tokarev and Nina Gagin-Torn con-

tinued to produce substantive scholarly works dur-

ing the 1930s, while others collaborated with state

institutions in conducting censuses and resolving

practical issues of nationality policy. Soviet ethno-

graphers and anthropologists were also called upon

to repudiate Nazi racial ideology. Like many other

fields, ethnography was badly shaken by the trials

and purges of the 1930s. By the end of the decade

many leading ethnographers had been executed or

imprisoned in the gulag.

After World War II Soviet ethnography revived.

Sergei Tolstov of the Academy of Sciences in

Moscow was instrumental in drawing together a

cadre of talented scholars, revitalizing professional

training, and regaining for the field the autonomous

status it had previously enjoyed. By the 1960s So-

viet ethnography was a thriving profession whose

central and local institutions produced a wealth of

publications, sponsored numerous expeditions, and

trained large numbers of talented students. Ideo-

logical constraints persisted, however, as ethnog-

raphers were often called upon to document a priori

the successes of soviet nationality policy. As a rule

ethnographers were expected to show a stark con-

trast between a dark past and a present tarnished

in places by lingering survivals but well on the way

toward the bright communist future. Rather than

confront the exigencies of the present day, how-

ever, many ethnographers chose to linger in the

past. Much of the most substantive work produced

in the 1950s and 1960s was historical in nature,

with the topic of ethnogenesis, or the origins of

peoples, enjoying particular popularity. The 1970s,

however, brought a renewed emphasis on contem-

porary ethnic processes. Yuly Bromlei, director of

the Institute of Ethnography in Moscow, put forth

his theory of ethnos, which attempted to show

how ethnicity continued to be a vital force even as

the peoples of the Soviet Union drew together

(sblizhenie) in a process that would ultimately lead

to their merging (slyanie) into a new form of hu-

man collectivity—the Soviet nation. Bromlei’s the-

ory remained the guiding doctrine of the field

through the 1980s as social processes, such as in-

termarriage, geographical mobility, and bilingual-

ism seemed to support the model of the merging

of the peoples. However, much of the practical

work of ethnographers, particularly on the local

level, had the effect of solidifying and reinforcing

the symbolic attributes of ethnic consciousness. The

flowering of ethnic nationalism in the late 1980s

and early 1990s took place on ground well pre-

pared by the work of Soviet ethnographers.

See also: ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; BYLINA; FOLKLORE; FOLK

MUSIC; PRIMARY CHRONICLE; NATION AND NATION-

ALITY; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALI-

TIES POLICIES, TSARIST; RUSSIAN GEOGRAPHICAL

SOCIETY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Grant, Bruce. (1995). In the Soviet House of Culture: A Cen-

tury of Perestroikas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univer-

sity Press.

Hirsch, Francine. (1997). “The Soviet Union as a Work-

in-Progress: Ethnographers and the Category ‘Na-

tionality’ in the 1926, 1937 and 1939 Censuses.”

Slavic Review 52(2):251–278.

Knight, Nathaniel. (1998). “Science, Empire and Nation-

ality: Ethnography in the Russian Geographical So-

ciety, 1845–1855.” In Imperial Russia: New Histories

for the Empire, ed. Jane Burbank and David Ransel.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Knight, Nathaniel. (1999). “Ethnicity, Nationality and

the Masses: Narodnost and Modernity in Imperial

Russia.” In Russian Modernity, ed. David Hoffmann

and Yanni Kotsonis. New York: Macmillan/St. Mar-

tin’s.

ETHNOGRAPHY, RUSSIAN AND SOVIET

470

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Slezkine, Yuri. (1994). Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small

Peoples of the North. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

N

ATHANIEL

K

NIGHT

EVENKI

The Evenki are the most geographically wide-

ranging native people of Russia, occupying a terri-

tory from west of the Yenisey River to the Pacific

Ocean, and from near the Arctic Ocean to north-

ern China. One of Russia’s northern peoples, they

number about thirty thousand. Traditionally

many Evenki pursued hunting, using small herds

of domesticated reindeer mainly for transport and

milk. Some groups focused more on fishing,

whereas in northerly areas larger-scale reindeer

husbandry was pursued. Largely nomadic, Evenki

lived in groups of a few households, gathering an-

nually in larger groups to trade news and goods,

arrange marriages, and so forth.

The Evenki language is part of the Manchu-

Tungus language group. Its four dialects differ sub-

stantially, a fact ignored by the soviets when they

introduced Evenki textbooks based on the central

dialect, which were barely intelligible to those in

the East. Evenki cosmology includes a number of

worlds; and their shamans negotiate between these

worlds. Indeed, the word shaman derives from the

Evenki samanil, their name for such spiritual lead-

ers. Shamans were severely repressed during the

Soviet period; the possibility of revitalizing

shamanism proved a common trope for cultural

revival among Evenki in early post-Soviet years.

Russian traders began to penetrate Evenki home-

lands in the mid-seventeenth century. Prior to this,

southern Evenki had carried on trade relations with

the Chinese. Russians subjected Evenki to a fur tax

(yasak), and held hostages to ensure its payment.

The Soviet government brought new forms of con-

trol, organizing Evenki into collective farms, ar-

resting rich herders, and settling nomads to the ex-

tent possible. Families were often sundered, as

adults remained with the reindeer herds while chil-

dren attended compulsory school. Children were

not taught their own language or how to pursue

traditional activities. Inadequate schooling, racism,

and apathy have hindered their ability to pursue

nontraditional activities. In some areas, mining and

smelting have removed substantial pastures and

hunting grounds through environmental degrada-

tion. Hydropower projects have also challenged

traditional activities by appropriating portions of

Evenki territory.

Since the demise of the Soviet Union, Evenki

reindeer herds have suffered serious decline. At the

same time substantial numbers of families took the

opportunity provided by new laws to leave state-

owned farms and establish small, family based

hunting and herding operations. However, lack of

government support has made the survival of these

enterprises almost impossible. Evenki are battling

this predicament through the establishment of

quasipolitical organizations, mainly at the regional

level, to pursue their rights.

See also: NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST; NORTHERN PEOPLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, David. (2000). “The Evenkis of Central

Siberia.” In Endangered Peoples of the Arctic. Struggles

to Survive and Thrive, ed. Milton M. Freeman. West-

port, CT: Greenwood Press.

Anderson, David. (2000). Identity and Ecology in Arctic

Siberia. The Number One Reindeer Brigade. Oxford: Ox-

ford University Press.

Fondahl, Gail. (1998). Gaining Ground? Evenkis, Land, and

Reform in Southeastern Siberia. Boston, MA: Allyn and

Bacon.

G

AIL

A. F

ONDAHL

EVENKI

471

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

This page intentionally left blank