Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

of Soviet goals. In the closing years of the USSR

the symbols of Russian identity, the tsarist tricolor

flag and the double-headed eagle, were commonly

seen, while cities and streets regained their prerev-

olutionary Russian names. For many Russians, a

distinction existed between Russian and Soviet iden-

tity.

COLLAPSE OF THE SOVIET EMPIRE

Debate continues over the causes of the collapse of

the USSR and specifically the extent to which So-

viet handling of its multiethnic empire was re-

sponsible for it. The Soviet federal structure,

although leaving real power in Moscow, neverthe-

less institutionalized and therefore strengthened

national identities, which are lethal to any multi-

national empire. Yet the goal of nationality policy

was the creation of a supranational Soviet identity.

Despite this contradiction, Soviet nationality policy

when compared to that of other imperial polities

enjoyed a relative degree of success. By encourag-

ing dependence on the state and protecting the ed-

ucational and occupational interests of the local

political elite and educated middle class, the central

Soviet leadership blunted aspirations to independent

nationhood and integrated groups within the So-

viet infrastructure. While the use of local elites to

govern the periphery is a traditional imperial prac-

tice, providing a degree of legitimacy to the impe-

rial power, Soviet non-Russian elites achieved

powerful positions within their respective re-

publics, wielding power unattainable by the colo-

nized local populations in the French and British

empires.

Ideological power is as strong as its ability to

deliver what it promises. Disillusionment with the

unfulfilled economic promises of the Soviet ideol-

ogy weakened loyalty to the Soviet identity. Gor-

bachev’s economic policies only worsened the

economic situation. At the same time, Gorbachev

ended the CPSU’s monopoly on power. Faced with

growing popular dissatisfaction with the economic

situation and loss of guarantee of power through

the CPSU, regional and local political figures be-

came nationalists when the national platform

seemed to be the only way for them to retain power

as the imperial center, the CPSU, weakened.

Russia itself led the charge against the Soviet

center, thereby creating a unique situation. The

country that many people inside and outside the

USSR considered to be the imperial power, revolted

against what it regarded to be the imperial power,

the CPSU and central Soviet control over Russia,

leading to the collapse of one of the world’s great

land-based empires.

See also: COLONIAL EXPANSION; COLONIALISM; NATION-

ALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

TSARIST; UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barkey, Karen, and Von Hagen, Mark, eds. (1997). After

Empire. London: Westview Press.

Dawisha, Karen, and Parrott, Bruce, eds. (1997). The End

of Empire? The Transformation of the USSR in Compar-

ative Perspective. London: M. E. Sharpe.

Lieven, Dominic. (2000). Empire. London: John Murray.

Nahaylo, Bohdan, and Swoboda, Victor. (1990). Soviet

Disunion. London: Penguin.

Pipes, Richard. (1964). The Formation of the Soviet Union.

London: Harvard University Press.

Rezun, Miron, ed. (1992). Nationalism and the Breakup of

an Empire: Russia and Its Periphery. Westport, CT:

Praeger.

Rudolph, Richard, and Good, David, eds. (1992). Nation-

alism and Empire: The Habsburg Empire and the Soviet

Union. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Suny, Ronald. (1993). The Revenge of the Past: National-

ism, Revolution, and the Collapse of the Soviet Union.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Szporluk, Roman. (2000). Russia, Ukraine, and the Breakup

of the Soviet Union. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution

Press.

Z

HAND

P. S

HAKIBI

ENGELS, FRIEDRICH

(1820–1895), German socialist theoretician; close

collaborator of Karl Marx.

Friedrich Engels is remembered primarily as the

close friend and intellectual collaborator of Karl

Marx, who was the most important socialist

thinker and arguably the most important social

theorist of the nineteenth century. Engels must be

regarded as a significant intellectual figure in his

own right. Engels’s writings exerted a strong in-

fluence on Soviet Marxist-Leninist ideology. Engels

was born in Barmen in 1820, two and a half years

after Marx. Ironically, Friedrich Engels worked for

decades as the manager of enterprises in his fam-

ily’s firm of Ermen and Engels; this necessitated his

move to Manchester in 1850. Engels contributed

substantially to the financial support of Marx and

ENGELS, FRIEDRICH

453

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

his family. He survived Marx by twelve years, dur-

ing an important period in the growth of the so-

cialist movement when Engels served as the most

respected spokesman for Marxist theory.

In recent decades there has been a lively debate

over the degree of divergence between Marx’s

thought and that of Engels, and therefore over

whether the general scheme of interpretation

known as “historical materialism” or “dialectical

materialism” was primarily constructed by Engels

or accorded with the main thrust of Marx’s intel-

lectual efforts. George Lichtheim and Shlomo

Avineri, distinguished scholars who have written

about Marx, see Engels as having given a rigid cast

to Marxist theory in order to make it seem more

scientific, thus implicitly denying the creative role

of human imagination and labor that had been em-

phasized by Marx. On the other hand, some works,

such as those by J. D. Hunley and Manfred Steger,

emphasize the fundamental points of agreement be-

tween Marx and Engels. The controversy remains

unresolved and facts point to both convergence and

divergence: Marx and Engels coauthored some ma-

jor essays, including The Communist Manifesto, and

Engels made an explicit effort to give Marxism the

character of a set of scientific laws of purportedly

general validity. The well-known laws of the di-

alectic, which became the touchstones of philo-

sophical orthodoxy in Soviet Marxism-Leninism,

were drawn directly from Engels’s writings.

See also: DIALECTICAL MATERIALISM; MARXISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carver, Terrell. (1989). Friedrich Engels: His Life and

Thought. London: Macmillan.

Hunley, J. D. (1991). The Life and Thought of Friedrich En-

gels: A Reinterpretation. New Haven, CT: Yale Uni-

versity Press.

Steger, Manfred B., and Carver, Terrell, eds. (1999). En-

gels after Marx. University Park: Pennsylvania State

University Press.

A

LFRED

B. E

VANS

J

R

.

ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF

The Enlightenment is traditionally defined as an in-

tellectual movement characterized by religious

skepticism, secularism, and liberal values, rooted in

a belief in the power of human reason liberated

from the constraints of blind faith and arbitrary

authority, and opposed by the retrograde anti-

Enlightenment. Originated with the French

philosophes, especially Charles de Secondant Mon-

tesquieu (1689–1755), Denis Diderot (1713–1784),

François Marie Arouet de Voltaire (1684–1778),

and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), the En-

lightenment quickly spread through Europe and

the American colonies. It reached Russia in the

mid–eighteenth century, peaking during the reign

of Catherine II (1762–1796) and becoming one of

the most important components of the country’s

Westernization and modernization.

The impact of the Enlightenment in Russia is

generally described in terms of its reception and ac-

commodation of the ideas of the philosophes. These

ideas spurred new scientific and secular approaches

to culture and government that laid the foundation

of Russia’s modern intellectual and political culture.

In addition to greater intellectual exchange with

Europe, the Enlightenment brought Russia institu-

tions of science and scholarship, arts and theater,

the print revolution, and new forms of sociability,

such as learned and charitable societies, clubs, and

Masonic lodges. The Enlightenment created a new

generation of Russian scientists, scholars, and men

of letters (i.e., Mikhail Lomonosov, Nikolai Novikov,

Alexander Radishchev, and Nikolai Karamzin). The

Enlightenment also brought about an intense secu-

larization that significantly diminished the role of

religion and theology and transformed the monar-

chy into an enlightened absolutism.

The actual impact of the Enlightenment in Rus-

sia was limited and inconsistent, however. While

the writings of the philosophes were widely trans-

lated and read, Russian audiences were more inter-

ested in their novels than in their philosophical or

political treatises. Policy makers preferred German

cameralism and political science. Catherine’s self-

proclaimed adherence to the principles of the

philosophes was rather patchy, which prompted

widespread accusations that she had created the im-

age of philosopher on the throne to dupe the Eu-

ropean public. The progress of science, education,

and literature as well as the formation of the pub-

lic sphere owed more to government tutelage than

independent initiative. Most Russian champions of

Enlightenment were profoundly religious. Thus,

criticism of the Orthodox Church was virtually

nonexistent; anticlerical statements were directed

primarily against Catholicism, the old foe of Russ-

ian Orthodoxy. Some of the new forms of socia-

bility, such as Masonic lodges, served as venues not

only for liberal discussion, but also for the exer-

ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF

454

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

cises in occultism, alchemy, and criticism of the

philosophes. The Enlightenment in Russia was pre-

occupied with superficial cultural forms rather

than content.

The traditional picture outlined above needs to

be revised in light of new studies of the European

Enlightenment since the 1970s. Enlightenment is

no longer identified as a uniform school of thought

dominated by the philosophes. Instead it is under-

stood as a complex phenomenon, a series of debates

at the core of which lay the process of discovery

and proactive and critical involvement of the indi-

vidual in both private and public life. This concept

softens the binary divides between the secular and

the religious, the realms of private initiative and es-

tablished public authority, and, in many cases, the

conventional antithesis between Enlightenment and

anti-Enlightenment.

One may interpret the Enlightenment in Rus-

sia more comprehensively and less exclusively as a

process of discovering contemporary European cul-

ture and adapting it to Russian realities that pro-

duced a uniquely Russian national Enlightenment.

An analysis of enlightened despotism need not be

preoccupied with the balance between Enlighten-

ment and despotism and can focus instead on the

reformer’s own understanding of the best interests

of the nation. For example, it was political, demo-

graphic, and economic considerations rather than

an anticlerical ideology that drove Catherine’s pol-

icy of secularization. There is no need to limit dis-

cussions of the public debate to evaluations of

whether or not it conformed to the standards

of religious skepticism. Contemporary discussions

of the difference between true and false Enlighten-

ment demonstrate that religious education and

faith, along with patriotism, were viewed as the

key elements of true Enlightenment, while religious

toleration was touted as a traditional Orthodox

value. Instead of emphasizing the dichotomy be-

tween adoption of cultural institutions and recep-

tion of ideas, twenty-first century scholarship looks

at institutions as the infrastructure of Enlighten-

ment that created economic, social, and political

mechanisms crucial for the spread of ideas.

See also: CATHERINE II; FREEMASONRY; ORTHODOXY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

De Madariaga, Isabel. (1999). Politics and Culture in

Eighteenth-Century Russia: Collected Essays. New

York: Longman.

Dixon, Simon. (1999). The Modernisation of Russia, 1676-

1825. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gross, Anthony Glenn, ed. (1983). Russia and the West

in the Eighteenth Century. Newtonville, MA: Oriental

Research Partners.

Smith, Douglas. (1999). Working the Rough Stone: Freema-

sonry and Society in Eighteenth-Century Russia.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Wirtschafter, Elise Kimerling. (2003). The Play of Ideas in

Russian Enlightenment Theater. DeKalb: Northern Illi-

nois University Press.

O

LGA

T

SAPINA

ENSERFMENT

Enserfment refers to the broad historical process

that made the free Russian peasantry into serfs,

abasing them further into near-slaves, then eman-

cipating them from their slavelike status and fi-

nally freeing them so that they could move and

conduct their lives with the same rights as other

free men in the Russian Empire. This process took

place over the course of nearly five hundred years,

between the 1450s and 1906. Almost certainly en-

serfment would not have occurred had not 10 per-

cent of the population been slaves. Also, it could

not have reached the depths of human abasement

had not the service state been present to legislate

and enforce it.

The homeland of the Great Russians, the land

between the Volga and the Oka (the so-called Volga-

Oka mesopotamia), is a very poor place. There are

almost no natural resources of any kind (gold,

silver, copper, iron, building stone, coal), the three-

inch-thick podzol soil is not hospitable to agricul-

ture, as is the climate (excessive precipitation and a

short growing season). Until the Slavs moved into

the area in the eleventh through the thirteenth cen-

turies, the indigenous Finns and Balts were sparsely

settled and lived neolithic lives hunting and fishing.

This area could not support a dense population, and

any prolonged catastrophe reduced the population

further, creating the perception of a labor shortage.

The protracted civil war over the Moscow throne

between 1425 and 1453 created a labor shortage

perception.

At the time the population was free (with

the exception of the slaves), with everyone able to

move about as they wished. Because population

ENSERFMENT

455

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

densities were so low and agriculture was exten-

sive (peasants cleared land by the slash-and-burn

process, farmed it for three years, exhausted its fer-

tility, and moved on to another plot), land owner-

ship was not prized. Government officials and

military personnel made their livings by collecting

taxes and fees (which can be levied from a semi-

sedentary population) and looting in warfare, not

by trying to collect rent from lands tilled by set-

tled farmers. Monasteries were different: In about

1350 they had moved out of towns (because of the

Black Death, inter alia) into the countryside and en-

tered the land ownership business, raising and sell-

ing grain. They recruited peasants to work for them

by offering lower tax rates than peasants could get

by living on their own lands. The civil war dis-

rupted this process, and some monasteries, which

had granted some peasants small loans as part of

the recruitment package, found that they had dif-

ficulty collecting those loans. Consequently a few

individual monasteries petitioned the government

to forbid indebted peasants from moving at any

time other than around St. George’s Day (Novem-

ber 26). St. George’s Day was the time of the pre-

Christian, pagan end of the agricultural year, akin

to the U.S. holiday, Thanksgiving. The monaster-

ies believed that they could collect the debts owed

to them at that time before the peasants moved

somewhere else.

This small beginning—involving a handful of

monasteries and only their indebted peasants—ini-

tiated the enserfment process. It is possible that the

government rationalized its action because not pay-

ing a debt was a crime (a tort, in those times); thus,

forbidding peasant debtors from moving was a

crime-prevention measure. Also note that this was

the normal time for peasants to move: The agri-

cultural year was over, and the ground was prob-

ably frozen (the average temperature was -4

degrees Celsius), so that transportation was more

convenient than at any other time of year, when

there might be deep snow, floods, mud, drought,

and so on.

For unknown reasons this fundamentally triv-

ial measure was extended to all peasants in the Law

Code (Sudebnik) of 1497. Similar limitations on

peasant mobility were present in neighboring po-

litical jurisdictions, and there may have been a con-

tagion effect. It also may have been viewed as a

general convenience, for that is when peasants

tended to move anyway. As far as is known, there

were no contemporary protests against the intro-

duction of St. George’s Day, and in the nineteenth

century the peasants had sayings stating that a

reintroduction of St. George’s Day would be tan-

tamount to emancipation. The 1497 language was

repeated in the Sudebnik of 1550, with the addition

of verbiage reflecting the introduction of the three-

field system of agriculture: Peasants who had sown

an autumn field and then moved on St. George’s

Day had the right to return to harvest the grain

when it was ripe.

Chaos with its inherent disruption of labor sup-

plies caused the next major advance in the enserf-

ment process: the introduction of the “forbidden

years.” Ivan IV’s mad oprichnina (1565–1572)

caused up to 85 percent depopulation of certain ar-

eas of old Muscovy. Recent state expansion and an-

nexations encouraged peasants disconcerted by

oprichnina chaos to flee for the first time to areas

north of the Volga, to the newly annexed Kazan

and Astrakhan khanates, and to areas south of the

Oka in the steppe that the government was begin-

ning to secure. In addition to the chaos caused by

oprichnina military actions, Ivan had given lords

control over their peasants, allowing them “to col-

lect as much rent in one year as formerly they had

collected in ten.” His statement ordering peasants

“to obey their lords in everything” also began the

abasement of the serfs by making them subject to

landlord control. Yet other elements entered the pic-

ture. The service state had converted most of the

land fund in the Volga-Oka mesopotamia and in

the Novgorod region into service landholdings (po-

mestie) to support its provincial cavalry, the mid-

dle service class. These servicemen could not render

service without peasants on their pomestie lands to

pay them regular rent. Finding their landholdings

being depopulated, a handful of cavalrymen peti-

tioned that the right of peasants to move on St.

George’s Day be annulled. The government granted

these few requests, and called the times when peas-

ants could not move “forbidden years.” Like St.

George’s Day, the forbidden years initially applied

to only a few situations, but in 1592 (again for

precisely unknown reasons) they were applied tem-

porarily to all peasants.

That should have completed the enserfment

process. However, there were two reservations.

First, it was explicitly stated that the forbidden

years were temporary (although they did not ac-

tually end until 1906). Second, the government im-

posed a five-year statute of limitations on the

enforcement of the forbidden years. Historians as-

sume that this was done to benefit large, privileged

landowners who could conceal peasants for five

ENSERFMENT

456

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

years on various estates so that their legal posses-

sors (typically middle-service-class cavalrymen)

could not find them and file suit for their return.

Moreover, there was the issue of colonial expan-

sion: The government wanted the areas north of

the Volga, south of the Oka in the steppe, and along

the Middle and South Volga eastward into the Urals

and Siberia settled. It even had its own agents to

recruit peasants into these areas, typically with the

promise of half-taxation. Those running the ex-

pansion of the Muscovite state did not want their

sparse frontier populations diminished by the

forcible return of fugitive peasants to Volga-Oka

mesopotamia. Thus they also supported the five-

year statute of limitations on the filing of suits for

the recovery of fugitive serfs.

The Time of Troubles provided a breathing spell

in the enserfment process. Events occurred relevant

to enserfment, but they had no long-term impact—

with the possible exception of Vasily Shuisky’s

near-equation of serfs with slaves in 1607. After

the country had recovered from the Troubles and

from the Smolensk War (1632–1634), the middle-

service class sensed that the new Romanov dynasty

was weak and thus susceptible to pressure. In 1637

the cavalrymen began a remarkable petition cam-

paign for the repeal of the statute of limitations on

the filing of suits for the recovery of fugitive peas-

ants. This in some respects was modeled after a

campaign by townsmen to compel the binding of

their fellows to their places of residence because of

the collective nature of the tax system: When one

family moved away, those remaining had to bear

the burden imposed by the collective tax system

until the next census was taken. For the townsmen

the reference point typically was 1613, the end of

the Time of Troubles. For the cavalrymen petition-

ers, the reference points were two: the statute of

limitations and the documents (censuses, pomestie

land allotments) proving where peasants lived. The

middle-service-class petitioners pointed out that the

powerful (i.e., contumacious) people were recruit-

ing their peasants, concealing them for five years,

and then using the fugitives to recruit others to

flee. The petitioners, who had 5.6 peasant house-

holds apiece, alleged that the solution to their di-

minishing ability to render military service because

of their ongoing losses of labor would be to repeal

the statute of limitations. The government’s re-

sponse was to extend the statute of limitations

from five to nine years. Another petition in 1641

extended it from nine to fifteen years. A petition of

1645 elicited the promise that the statute of limi-

tations would be repealed once a census was taken

to show where the peasants were living.

The census was taken in 1646 and 1647 but no

action was taken. The government was being run

by Boris Morozov, whose extensive estate records

reveal that he was recruiting others lords’ peasants

in these years. Morozov and his corrupt accomplices

got their comeuppance after riots in Moscow, which

spread to a dozen other towns, led to their over-

throw and to demands by the urban mob for

a codification of the law. Tsar Alexis appointed

the Odoyevsky Commission, which drafted the

Law Code of 1649 (ulozhenie). It was debated and

approved with significant amendments by the As-

sembly of the Land of 1648–1649. Part of the

amendments involved the enserfment, especially the

repeal of the forbidden years. Henceforth all peas-

ants were subject to return to wherever they or their

forbears were registered. This measure applied to all

peasants, both those on the lands of private lords

and the church (seignorial peasants) and those on

lands belonging to the tsar, the state, and the peas-

ants themselves (later known as state peasants). The

land cadastre of 1626, the census of 1646–1647, and

pomestie allotment documents were mentioned, but

almost any other official documents would do as

well. Aside from the issue of documentation, the

other major enserfment issue was what to do with

runaways, especially males and females who be-

longed to different lords and got married. The solu-

tions were simple and logical: The Orthodox Church

did not permit the breaking up of marriages, so the

Law Code of 1649 decreed that the lord who had re-

ceived a fugitive lost the couple to the lord from

whom the fugitive had fled. If they wed as fugitives

on “neutral ground,” then the lord-claimants cast

lots; the winner got the couple and paid the loser

for his lost serf.

The Law Code did not resolve the issue of fugi-

tives, because of the intense shortage of labor in

Muscovy. After 1649 the government began to pe-

nalize recipients of fugitives by confiscating an ad-

ditional serf in addition to the fugitive received. This

had no impact, so it was raised to two. This in turn

had no impact, so it was raised to four. At this

point would-be recipients of fugitive serfs began to

turn them away. Peter I took this one step further

by proclaiming the death penalty for those who

received the fugitive serfs, but it is not known

whether anyone was actually executed.

The Law Code of 1649 opened the door to the

next stage of enserfment. Lords wanted the peasants

converted into slaves who could be disposed of as

ENSERFMENT

457

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

they wished (willed, sold, given away, moved).

This contradicted the idea that serfs existed to

support the provincial cavalry. The Law Code per-

mitted landowners to move their serfs around,

whereas landholders had to leave them where they

were so that the next cavalry serviceman would

have rent payers when the pomestie was assigned

to him. The extent to which (or even whether) serfs

were sold like slaves before 1700 is still being de-

bated.

The issue was resolved during the reign of Pe-

ter I by two measures. First, in 1714 the service

landholding and hereditary estate (votchina) were

made equal under the law. Second, the introduc-

tion of the soul tax in 1719 made the lord respon-

sible for his serfs’ taxes and gave him much greater

control over his subjects, especially after the col-

lection of the soul tax commenced in 1724. In the

same year, peasants were required to have a pass

from their owners to travel. This was strengthened

in 1722, and again in 1724. That serfs were be-

coming marketable was reflected in the April 15,

1721, ban on the sale of individual serfs. Whether

the ban was ever enforced is unknown. The fact

that it probably was not was reflected in a law of

1771 forbidding the public sale of serfs (the private

sale of serfs was permitted) and a 1792 decree for-

bidding an auctioneer to use a gavel in serf auc-

tions, indicating that the 1771 law was not

observed either.

After 1725 the descent of seignorial serfs into

slavery accelerated. In 1601 Godunov had required

owners to feed their slaves, and in 1734 Anna ex-

tended this to serfs. In 1760 lords were allowed to

banish serfs to Siberia. This was undoubtedly done

to try to ensure calm in the villages. That this pri-

marily concerned younger serfs (who could have

been sent into the army) is reflected in the fact that

owners received military recruit credit for such ex-

iles.

A tragic date in Russian history was February

18, 1762, when Peter III abolished all service re-

quirements for estate owners. This permitted ser-

fowners to supervise (and abuse) their serfs

personally. Thus it is probably not accidental that

five years later, in 1767, Catherine II forbade serfs

to petition against their owners. Catherine, sup-

posedly enlightened, opposed to serfdom, and in fa-

vor of free labor, gave away 800,000 serfs to

private owners during her reign. The year 1796

was the zenith of serfdom.

Paul tried to undo everything his mother

Catherine had done. This extended to serfdom. In

1797 he forbade lords to force their peasants to

work on Sunday, suggested that peasants could

only be compelled to work three days per week,

and that they should have the other three days to

work for themselves. Paul was assassinated before

he could do more.

His son Alexander I wanted to do something

about serfdom, but became preoccupied with

Napoleon and then went insane. He was informed

by Nikolai Karamzin in 1811 that the Russian Em-

pire rested on two pillars, autocracy and serfdom.

Emancipation increasingly became the topic of pub-

lic discussion. After suppressing the libertarian De-

cembrists in 1725, Nicholas I wanted to do

something about serfdom and appointed ten com-

mittees to study the issue. His successor, Alexan-

der II, took the loss of the Crimean War to mean

that Russia, including the institution of serfdom,

needed reforming. His philosophy was “better from

above than below.” Using Nicholas I’s “enlightened

bureaucrats,” who had studied serfdom for years,

Alexander II proclaimed the emancipation of the

serfs in 1861, but this only freed the serfs from

their slavelike dependence on their masters. They

were then bound to their communes. State serfs

were freed separately, in 1863. The seignorial serfs

had to pay for their freedom, that is, the state was

unwilling to expropriate the serfowners and si-

multaneously feared the consequences of a landless

emancipation.

The serfs were finally freed in 1906, when they

were released from control by their communes, the

redemption dues were cancelled, and corporal pun-

ishment for serfs was abolished. Thus, all peasants

were free for the first time since 1450.

See also: EMANCIPATION ACT; LAW CODE OF 1649; PEAS-

ANTRY; PODZOL; POMESTIE; SUDEBANK OF 1497;

SUDEBANK OF 1550; SERFDOM; SLAVERY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blum, Jerome. (1961). Lord and Peasant in Russia: From

the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Hellie, Richard. (1967, 1970). Muscovite Society. Chicago:

The University of Chicago College Syllabus Division.

Hellie, Richard. (1971). Enserfment and Military Change in

Muscovy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hellie, Richard, tr. and ed. (1988). The Muscovite Law Code

(Ulozhenie) of 1649. Irvine, CA: Charles Schlacks,

Publisher.

ENSERFMENT

458

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Kolchin, Peter. (1987). Unfree Labor. American Slavery and

Russian Serfdom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press.

Robinson, Geroid Tanquery. (1932). Rural Russia under

the Old Regime. New York: Longmans.

Zaionchkovsky, P. A. (1978). The Abolition of Serfdom in

Russia. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic International Press.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

ENTERPRISE, SOVIET

Soviet industrial enterprises (predpryatie), occupy-

ing the lowest level of the economic bureaucracy,

were responsible for producing the goods desired

by planners, as specified in the techpromfinplan

(technical-industrial financial plan) received by the

enterprise each year. Owned by the state, headed

by a director, and governed by the principle of one-

person management (edinonachalie), each Soviet en-

terprise was subordinate to an industrial ministry.

For example, enterprises producing shoes and

clothing were subordinate to the Ministry of Light

Industry; enterprises producing bricks and mortar,

to the Ministry of Construction Materials; enter-

prises producing tractors, to the Ministry of Trac-

tor and Agricultural Machine Building. Enterprises

producing military goods were subordinate to the

Ministry of Defense Industry. In some cases, en-

terprises subordinate to the Ministry of Defense In-

dustry also produced civilian goods—for example,

all products using electronic components were pro-

duced in military production enterprises. Many en-

terprises producing civilian goods and subordinate

to a civilian industrial ministry had a special de-

partment, Department No. 1, responsible for mili-

tary-related production (e.g., chemical producers

making paint for military equipment or buildings,

clothing producers making uniforms and other

military wear, shoe producers making military

footwear). While the enterprise was subordinate to

the civilian industrial ministry, Department No. 1

reported to the appropriate purchasing department

in the Ministry of Defense.

During the 1970s industrial enterprises were

grouped into production associations (obedinenya)

to facilitate planning. The creation of industrial or

production associations was intended to improve

the economic coordination between planners and

producers. By establishing horizontal or vertical

mergers of enterprises working in related activities,

planning officials could focus on long-term or ag-

gregate planning tasks, leaving the management of

the obedinenya to resolve problems related to rou-

tine operations of individual firms. In effect the obe-

dinenya simply added a management layer to the

economic bureaucracy because the industrial en-

terprise remained the basic unit of production in

the Soviet economy.

Soviet industrial enterprises were involved in

formulating and implementing the annual plan.

During plan formulation, enterprises provided in-

formation about the material and technical supplies

needed to fulfill a targeted level and assortment of

production, and updated accounts of productive

capacity. Because planning policy favored taut

plans (i.e., plans with output targets high relative

to input allocations and the firm’s productivity ca-

pacity), output targets based on previous plan ful-

fillment (i.e., the “ratchet effect” or “planning from

the achieved level”), and large monetary bonuses

for managers if output targets were fulfilled, So-

viet enterprise managers were motivated to estab-

lish a safety factor by over-ordering inputs and

under-reporting productive capacity during the

plan formulation process. Similarly, during plan

implementation, they were motivated to sacrifice

quality in order to meet quantity targets or to fal-

sify plan fulfillment documents if quantity targets

were not met. In some instances managers would

petition for a correction in the plan targets that

would reduce the output requirements for a par-

ticular plan period (month, quarter, or year). In

such instances they apparently expected that their

future plan targets would be revised upward. In

the current period, if plan targets were lowered for

one firm, planning officials redistributed the out-

put to other firms in the form of higher output

targets, so that the annual plan targets would be

met for the industrial ministry.

Unlike enterprises in market economies, Soviet

enterprises were not concerned with costs of pro-

duction. The prices firms paid for materials and la-

bor were fixed by central authorities, as were the

prices they received for the goods they produced.

Based on average cost rather than marginal cost of

production, and not including capital charges, the

centrally determined prices did not reflect scarcity,

and were not adjusted to capture changes in sup-

ply or demand. Because prices were fixed, and cost

considerations were less important than fulfilling

quantity targets in the reward structure, Soviet en-

terprises were not concerned about profits. Profits

and profitability norms were specified in the an-

nual enterprise plan, but did not signal the same

ENTERPRISE, SOVIET

459

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

information about the successful operation and

performance of the firm that they do in a market

economy. Typically, failure to earn profits was an

accounting outcome rather than a performance

outcome, and resulted in the planning authorities

providing subsidies to the firm.

The operation and performance of Soviet en-

terprises was monitored by planning authorities

using the financial plan component of the annual

techpromfinplan. The financial plan corresponded

to the input and output plans, documenting the

flow of materials and goods between firms, as well

as wage payments, planned cost reductions, and

the like. Financial accounts for the sending and re-

ceiving firms in any transaction were adjusted by

the state bank (Gosbank) to match the flow of

materials or goods. Furniture manufacturers, for

example, were given output targets for each item

in their assortment of production—tables, chairs,

benches, cabinets, bookshelves. The plan further

specified the input allocations associated with each

item. Gosbank debited the accounts of the furni-

ture manufacturer when the designated inputs

were received and credited the accounts of the sup-

plying firms. Planned transactions did not involve

the exchange of cash between firms. Gosbank pro-

vided cash to the enterprise each month to pay

wages; the maximum amount that an enterprise

could withdraw from Gosbank was based on the

planned number of employees and the centrally

determined wages. Cash disbursements for wage

payments were strictly controlled to preclude en-

terprise directors from acting independently from

planners’ preferences. Financial control was further

exercised by planners in that Gosbank only pro-

vided short-term credit if specified in the annual

enterprise plan. This system of financial supervi-

sion was called ruble control (kontrol rublem).

See also: EDINONACHALIE; GOSBANK; MONETARY SYSTEM,

SOVIET; RUBLE CONTROL; TECHPROMFINPLAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berliner, Joseph S. (1957). Factory and Manager in the

USSR. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Freris, Andrew. (1984). The Soviet Industrial Enterprise.

New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Granick, David. (1954). Management of the Industrial Firm

in the USSR. New York: Columbia University Press.

Linz, Susan J., and Martin, Robert E. (1982). “Soviet En-

terprise Behavior under Uncertainty.” Journal of

Comparative Economics 6:24–36.

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

ENVIRONMENTALISM

Environmental protection in Russia traces its roots

to seventeenth-century hunting preserves and Pe-

ter the Great’s efforts to protect some of the coun-

try’s forests and rivers. But environmentalism, in

the sense of an intellectual or popular movement

in support of conservation or environmental pro-

tection, began during the second half of the nine-

teenth century and scored some important victories

during the late tsarist and early soviet periods. The

movement lost most of its momentum during the

Stalin years but revived during the 1960s and

1970s, peaking during the era of perestroika. Af-

ter a decline during the early 1990s, environmen-

talism showed a resurgence later in the decade.

EARLY HISTORY

Sergei Aksakov’s extremely popular fishing and

hunting guides (1847 and 1851) awakened the

reading public to the extent and importance of cen-

tral Russia’s natural areas and helped popularize

outdoor pursuits. As the membership in hunting

societies grew in subsequent decades, so did aware-

ness of the precipitous decline in populations of

game species. Articles in hunting journals and the

more widely circulated “thick” journals sounded the

alarm about this issue. Provincial observers also

began to note the rapid loss of forest resources. No-

ble landowners, facing straitened financial circum-

stances after the abolition of serfdom, were selling

timber to earn ready cash. Anton Chekhov, among

others, lamented the loss of wildlife habitats and the

damage to rivers that resulted from widespread de-

forestation. By the late 1880s the outcry led to the

enactment of the Forest Code (1888) and hunting

regulations (1892). These laws had little effect, but

their existence testifies to the emergence of a Russ-

ian conservation movement.

In contrast to the environmentalism around the

same time in the United States and England, the

main impetus for the movement in Russia came

from scientists rather than amateur naturalists,

poets, or politicians. Russian scientists were pio-

neers in the fledgling field of ecology, particularly

the study of plant communities and ecosystems.

While they shared with western environmentalists

an aesthetic appreciation for natural beauty, they

were especially keen about the need to preserve

whole landscapes and ecosystems. During the early

twentieth century when the Russian conservation

movement began to press for the creation of na-

ENVIRONMENTALISM

460

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ture preserves, it did not adopt the U.S. model of

national parks designed to preserve places of ex-

traordinary beauty for recreational purposes. In-

stead, Russian scientists sought to preserve large

tracts of representative landscapes and keep them

off limits except to scientists who would use them

as laboratories for ecological observation. They

called these tracts zapovedniks, a word derived from

the religious term for “commandments” and con-

noting something forbidden or inviolate. The Per-

manent Commission on Nature Preservation,

organized in 1912 under the auspices of the Rus-

sian Geographical Society, proposed the creation of

a network of zapovedniks in 1917, shortly before

the Bolshevik Revolution. Its primary author was

the geologist Venyamin Semenov-Tian-Shansky

(1870–1942). His brother, Andrei (1866–1942), a

renowned entomologist, was an important propo-

nent of the project, along with the botanist Ivan

Borodin (1847–1930), head of the Permanent Com-

mission, and the zoologist Grigory Kozhevnikov

(1866–1933), who had first articulated the need for

inviolate nature preserves.

These scientists also sought to popularize a

conservation ethic among the populace, especially

among young people. Despite their many educa-

tional efforts, however, they were unable to build

a mass conservation movement. This was at least

partly because their insistence on keeping the na-

ture preserves off limits to the public prevented

them from capitalizing on the direct experience and

visceral affection that U.S. national parks inspire

in so many visitors.

SOVIET PERIOD

The early Bolshevik regime enacted a number of

conservation measures, including one to establish

zapovedniks in 1921. The politicization of all as-

pects of scientific and public activity during the

1920s, together with war, economic crisis, and lo-

cal anarchy, threatened conservation efforts and

made it difficult to protect nature preserves from

exploitation. In 1924 conservation scientists estab-

lished the All-Russian Society for Conservation

(VOOP) in order to build a broad-based environ-

ENVIRONMENTALISM

461

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

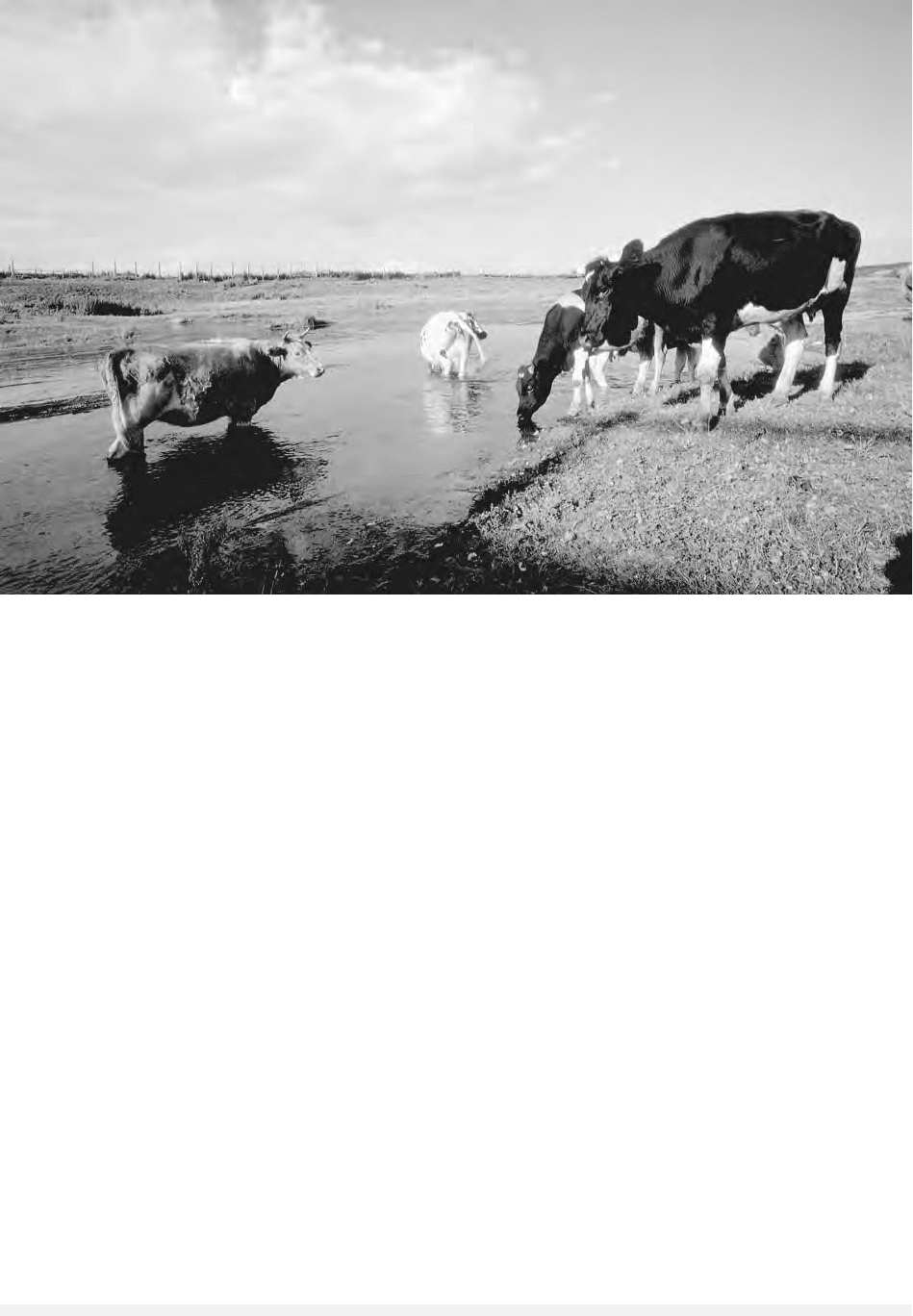

Half of the livestock in Muslumovo have leukemia, but their meat and milk are still consumed. © GYORI ANTOINE/CORBIS SYGMA

mental movement. VOOP organized popular events

such as Arbor Day and Bird Day, which attracted

45,000 young naturalists in 1927, and began pub-

lishing the magazine Conservation (Okhrana prirody)

in 1928, with a circulation of 3,000. An All-Russian

Congress for Conservation was convened in 1929,

and an All-Soviet Congress in 1933. By this time

conservationists had lost their optimism, over-

whelmed by the Stalinist emphasis on conquering

nature in the name of rapid industrial development.

The government whittled away at the idea of in-

violate zapovedniks over the ensuing decades, turn-

ing some into game reserves, others into breeding

grounds for selected species, and opening still oth-

ers to mining, logging, and agriculture. In 1950

the government proposed to turn over more than

85 percent of the protected territories to the agri-

culture and timber ministries.

Environmentalism of a grassroots and broad-

based variety finally began to develop after Stalin’s

death. VOOP had expanded to some nineteen mil-

lion members, but it existed primarily to funnel ex-

torted dues into dubious land-reclamation schemes.

The real impetus for environmentalism came dur-

ing the early 1960s in response to a plan to build

a large pulp and paper combine on Lake Baikal. Sci-

entists once again spearheaded the outcry against

the plan, which soon included journalists, famous

authors, and others who could reach a broad na-

tional and international audience. The combine

opened in 1967, but environmentalists gained a

symbolic victory when the government promised

to take extraordinary measures to protect the lake.

Similar grassroots movements arose during the

1970s and early 1980s to protest pollution in the

Volga River, the drying up of the Aral Sea, river-

diversion projects, and other threats to environ-

mental health.

Under Leonid Brezhnev, environmentalists were

able to air some of their grievances in the press, es-

pecially in letters to the editors of mass-circulation

newspapers. As long as they did not attack the idea

of economic growth or other underpinnings of so-

viet ideology, they were fairly free to voice their

opinions. By and large, the environmentalists called

for improvements in the central planning system

and more Communist Party attention to environ-

mental problems, not systemic changes. Their ar-

guments took the form of cheerleading for beloved

places rather than condemnations of the exploita-

tion of natural resources, and it became difficult to

distinguish environmentalism from local chauvin-

ism. In contrast to its counterpart in the West, en-

vironmentalism in the Soviet Union was often

closely aligned with right-wing nationalist politics.

Furthermore, environmental activism had little im-

pact on economic planners. Although, as official

propagandists boasted, the country had many pro-

gressive environmental laws, few of them were en-

forced. Activists were further hampered by official

secrecy about the extent of environmental prob-

lems. In 1978 a manuscript entitled “The Destruc-

tion of Nature in the Soviet Union” by Boris

Komarov (pseudonym of Ze’ev Wolfson, a special-

ist in environmental policy ) was smuggled out and

published abroad.

Environmentalism left the margins of soviet

society and took center stage in the period of glas-

nost. After the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, every-

one became aware of the threat soviet industry

posed for the environment and public health, and

also of the need for full disclosure of relevant in-

formation. Environmental issues galvanized local

movements against the central government, and

nationalist overtones in the environmental rhetoric

fanned the flames. In Estonia, protests in 1987

against a phosphorite mine grew into a full–blown

independence movement. Environmental issues also

helped initiate general political opposition in Latvia,

Lithuania, Kazakhstan, and elsewhere. Environ-

mentalists began to win real victories, closing or

halting production on some fifty nuclear plants and

many large construction projects. There were thou-

sands of grassroots environmental groups in the

country by 1991, and the Greens were second only

to religious groups in the degree of public trust they

enjoyed.

POST-SOVIET ACTIVISM

After 1991 the influence of Russian environmental

organizations declined. As the central government

consolidated its power, public attention turned to

pressing economic matters, and pollution problems

decreased as a result of the closing of many facto-

ries in the post-Soviet depression. Later in the

decade the government became openly hostile to

environmental activism. It arrested two whistle-

blowers, Alexander Nikitin and Grigory Pasko, who

revealed information about radioactive pollution

from nuclear submarines. President Vladimir Putin

dissolved the State Committee on the Environment

in 2000 and gave its portfolio to the Natural Re-

sources Ministry.

Environmental organizations survived by be-

coming professionalized nongovernmental organi-

zations (NGOs) on the Western model, seeking

ENVIRONMENTALISM

462

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY