Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

turn in foreign policy, pursuing cooperation with

the United States on issues such as disarmament,

the Middle East, Yugoslavia, and trade and eco-

nomic relations. He was also viewed by many as

one of the most important voices for liberalism and

democracy in post-Communist Russia.

However, the incipient partnership between

Moscow and Washington began to flounder in

1993 over such issues as the war in Yugoslavia and

NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) ex-

pansion. Critics began to push for a more forceful

and aggressive Russian foreign policy, and Kozyrev’s

language also became more bellicose on occasion,

including threats against Russia’s neighbors and an

assertion of special rights for Russia in the former

Soviet space—the Near Abroad. Nonetheless, this

was not enough, and by 1995 Yeltsin let it be

known that he was no longer satisfied with the

course of Russia’s foreign policy. In January 1996

Yevgeny Primakov, a career Soviet diplomat known

for more conservative views, replaced Kozyrev, who

then served as a member of the Russian Duma (par-

liament) until the end of 1999. He has written nu-

merous articles and books on international politics.

See also: NEAR ABROAD; PERESTROIKA; YELTSIN, BORIS

NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kozyrev, Andrei. (1995). “Partnership or Cold Peace?”

Foreign Policy 99: 3–14.

Talbott, Strobe. (2002). The Russia Hand: A Memoir of

Presidential Diplomacy. New York: Random House.

P

AUL

J. K

UBICEK

KRASNOV, PYOTR NIKOLAYEVICH

(1869–1947), Cossack ataman, anti-Bolshevik

leader, and author.

Son of a Cossack general, Pyotr Krasnov was

born in St. Petersburg and educated at Pavlovsk

Military School, graduating in 1888. During World

War I, he rose to the rank of lieutenant-general and

to the command of the Third Cavalry Corps in Au-

gust 1917. After the October Revolution, in uneasy

collaboration with Alexander Kerensky (whom, as

a monarchist, he despised), Krasnov was among the

first to take military action against the Bolsheviks,

attempting to lead Cossack forces from Gatchina

toward Petrograd. However, the Bolsheviks dis-

suaded his Cossacks from becoming involved in

“Russian affairs,” and Krasnov himself was taken

prisoner near Pulkovo. Remarkably, he was re-

leased after swearing not to oppose the Soviet gov-

ernment further. He immediately moved to the Don

territory, was elected ataman of the Don Cossack

Host in May 1918, and, assisted by Germany,

cleared the Don of Red forces over the summer of

that year. After the armistice, his former collabo-

ration with Germany made his position difficult.

Following defeats at the hands of the Reds and

quarrels with the pro-Allied General Denikin, in

early 1919 Krasnov resigned his post and emigrated

to Germany. He subsequently became a prolific

writer of forgettable historical novels but also

worked with various anti-Bolshevik groups in inter-

war Europe, eventually allying himself with the

Nazis and helping them, from 1941 to 1945, to

form anti-Soviet Cossack units from Soviet POWs.

In 1945 he joined the Cossack puppet state that the

Nazis established in the Italian Alps. Surrendering

to the British in May 1945, he was among those

forcibly repatriated to the Soviet Union, in accor-

dance with provisions of the Yalta agreement. In

January 1947, accused of treason, he was hanged,

by order of the Military Collegium of the USSR

Supreme Court.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; COSSACKS; KERENSKY,

ALEXANDER FYODOROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tolstoy, Nikolai. (1977). Victims of Yalta. London: Hod-

der & Stoughton.

J

ONATHAN

D. S

MELE

KRAVCHUK, LEONID MAKAROVICH

(b. 1934), Ukrainian politician and first president

of post-Soviet Ukraine.

Elected president of Ukraine on December 1,

1991—the same date as the historic referendum on

Ukrainian independence—Kravchuk won deci-

sively, garnering 61.6 percent of the popular vote

in a six-way contest. His primary political achieve-

ment was to establish Ukraine’s sovereignty and

maintain peace and social order with a minimum

of violence and almost no ethnic conflict. It is im-

possible to overemphasize the importance of this

accomplishment. However, he appears to have mis-

understood the relationship between state building

KRAVCHUK, LEONID MAKAROVICH

783

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and economic reforms. This failure would cost him

the presidency in early elections in July 1994.

A consummate politician, Kravchuk gained for

himself the nickname “sly fox” because of his abil-

ity to maneuver in predicaments that he himself

had created. His political shrewdness manifested it-

self in the events of 1991 when, as chairman of the

Ukrainian Supreme Soviet, he publicly vacillated

during the Moscow coup attempt of August 19–21.

While other Ukrainian officials supported Russian

President Boris Yeltsin, Kravchuk urged caution.

With the failure of the coup and with public

opinion turning against him, Kravchuk led the

Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU) to join the de-

mocratic opposition on August 24 and to adopt

Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence by a vote of

346 to 1. Kravchuk also redeemed himself by re-

signing from the CPU and the CPSU.

Clearly, the CPU strategy was to retain power

in an independent Ukraine. The democratic oppo-

sition was too weak and disorganized to take power

on its own; for this, they needed the Communists.

It is ironic that, as the former ideology chief of the

CPU, Kravchuk persecuted nationalist groups, such

as the Popular Front for Perestroika in Ukraine

(Rukh), only to appropriate their goals and program

in his 1991 bid for the newly established presi-

dency. As president, however, Kravchuk effectively

postponed economic and political reforms in favor

of nation building. A notable aspect of his leader-

ship was a continuing reliance on officials of the

former Communist apparat in key governmental

positions. Consequently, the simultaneous pursuit

of political stability and economic reform was all

but ruled out.

Confused and contradictory economic policies

emanated from Kravchuk’s government. He pub-

licly supported radical reforms even as he worked

to strengthen the hold of the former nomenklatura

over the state and economy. The saga of Kravchuk’s

management of the economy was the massive

emission of cheap credits and budget subsidies to

industry, coupled with the imposition of adminis-

trative controls over prices and currency exchange

rates. Major price increases in January and July

1992 drove Ukraine from the ruble zone in No-

vember of that year. But Ukrainian authorities

proved no better at controlling inflation, plunging

the nation into hyperinflation throughout 1993,

when prices increased by more than 10,000 per-

cent. Industrial output also plunged precipitously

as the economic crisis widened and deepened.

Throughout 1992 and into 1993, Kravchuk

was locked in a struggle with Prime Minister Leonid

D. Kuchma for authority to reform the economy.

Consequently, Kravchuk dismissed his errant pre-

mier in September 1993. The president made a half-

hearted attempt to renew the command economy

in late 1993, but by then the economic decline se-

verely damaged Kravchuk’s credibility. In response

to pressure from heavily industrialized eastern

Ukraine, Kravchuk agreed to early elections, to be

held in July 1994. Facing his one-time premier,

Leonid Kuchma, Kravchuk was defeated in the sec-

ond round, garnering but 45.1 percent of the pop-

ular vote. The former president did not retire from

politics, however; he was elected a member of par-

liament in a special election in September 1994, re-

placing a people’s deputy who died before taking

office. He was reelected in 1998 and 2002 from the

party lists of the Social Democratic Party of

Ukraine, and from 1998 onward has been a mem-

ber of the parliamentary Committee on Foreign Re-

lations.

See also: PERESTROIKA; UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kravchuk, Robert S. (2002). Ukrainian Political Economy:

The First Ten Years. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kuzio, Taras, and Andrew Wilson. (1994). Ukraine: Per-

estroika to Independence. Edmonton: Canadian Insti-

tute of Ukrainian Studies Press.

Wilson, Andrew. (1997). “Ukraine: Two Presidents and

Their Powers.” In Postcommunist Presidents, ed. Ray

Taras. New York: Cambridge University Press.

R

OBERT

S. K

RAVCHUK

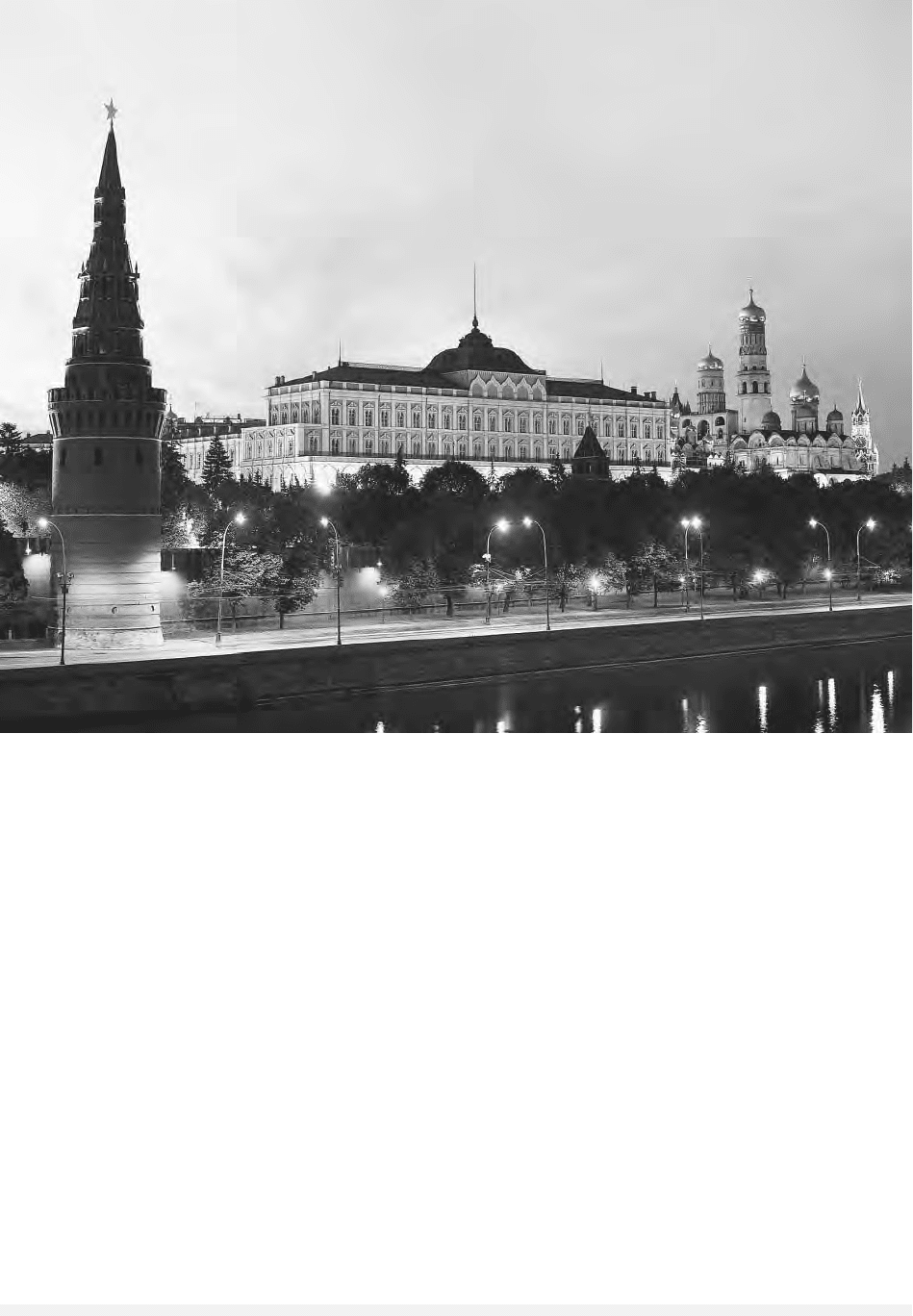

KREMLIN

Few architectural forms have acquired greater res-

onance than the Moscow Kremlin. In actuality

many medieval Russian towns had a “kremlin,” or

fortified citadel, yet no other kremlin acquired the

fame of Moscow’s. The Kremlin structure, a potent

symbol of Russian power and inscrutability, owes

much of its appearance to the Russian imagina-

tion—especially the tower spires added in the sev-

enteenth century by local architects. Yet the main

towers and walls are the product of Italian fortifi-

cation engineering of the quattrocento, already

long outdated in Italy by the time of their con-

struction in Moscow. Nonetheless, the walls proved

KREMLIN

784

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

adequate against Moscow’s traditional enemies

from the steppes, whose cavalry was capable of in-

flicting great damage on unwalled settlements, but

had little or no heavy siege equipment.

In the 1460s the Kremlin’s limestone walls, by

then almost a century old, had reached a danger-

ous state of disrepair. Local contractors were hired

for patchwork; as for reconstruction, Ivan III

turned to Italy for specialists in fortification. Be-

tween 1485 and 1516 the old fortress was replaced

with brick walls and towers extending 2,235 me-

ters and ranging in thickness from 3.5 to 6.5 me-

ters. The height of the walls varied from eight to

nineteen meters, with the distinctive Italian “swal-

lowtail” crenelation. Of the twenty towers, the

most elaborate were placed on the corners or at the

main entrances to the citadel. Among the most im-

posing is the Frolov (later Spassky, or Savior,

Tower), built between 1464 and 1466 by Vasily

Ermolin and rebuilt in 1491 by Pietro Antonio So-

lari, who arrived in Moscow from Milan in 1490.

The decorative crown was added in 1624 and 1625

by Bazhen Ogurtsov and the Englishman Christo-

pher Halloway. At the southeast corner of the

walls, the Beklemishev Tower (1487–1488, with an

octagonal spire from 1680) was constructed by

Marco Friazin, who frequently worked with Solari.

This and similar Kremlin towers suggest compar-

isons with the fortress at Milan. The distinctive

spires were added by local architects in the latter

part of the seventeenth century.

Although he built no cathedrals, Pietro Anto-

nio Solari played a major role in the renovation of

the Kremlin. He is known not only for his four

KREMLIN

785

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The Moscow Kremlin at twilight. © R

OYALTY

-F

REE

/CORBIS

entrance towers—the Borovitsky, the Constantine

and Helen, the Frolov, and the Nikolsky (all

1490–1493)—as well as the magnificent corner Ar-

senal Tower and the Kremlin wall facing the Red

Square, but also for his role in the completion of

the Faceted Chambers (Granovitaya palata), its

name due to the diamond-pointed rustication of its

limestone main facade. Used for banquets and state

receptions within the Kremlin palace complex, the

building was begun in 1487 by Marco Friazin, who

designed the three-storied structure with a great

hall whose vaulting was supported by a central

pier. Much of the ornamental detail, however, was

modified or effaced during a rebuilding of the

Chambers by Osip Startsev in 1682.

The rebuilding of the primary cathedral of

Moscow, the Dormition of the Virgin, began in the

early 1470s with the support of Grand Prince Ivan

III and Metropolitan Philip, leader of the Russian Or-

thodox Church. Local builders proved incapable of

so large and complex a task. Thus when a portion

of the walls collapsed, Ivan obtained the services of

an Italian architect and engineer, Aristotle Fiora-

vanti, who arrived in Moscow in 1475. He was in-

structed to model his structure on the Cathedral of

the Dormition in Vladimir; and while his design in-

corporates certain features of the Russo-Byzantine

style, the architect also introduced a number of tech-

nical innovations. The interior—with round columns

instead of massive piers—is lighter and more spa-

cious than any previous Muscovite church. The

same period also saw the construction of smaller

churches in traditional Russian styles, such as the

Church of the Deposition of the Robe (1484–1488)

and the Annunciation Cathedral (1484–1489).

The ensemble of Kremlin cathedrals commis-

sioned by Ivan III concludes with the Cathedral of

the Archangel Mikhail, built in 1505–1508 by Ale-

viz Novy. The building displays the most extrava-

gantly Italianate features of the Kremlin’s Italian

Period, such as the scallop motif, a Venetian fea-

ture soon to enter the repertoire of Moscovy’s ar-

chitects. The wall paintings on the interior date

from the mid-seventeenth century and contain, in

addition to religious subjects, the portraits of Russ-

ian rulers, including those buried in the cathedral

from the sixteenth to the end of the seventeenth

centuries.

The culminating monument in the rebuilding

of the Kremlin is the Bell Tower of Ivan the Great,

begun in 1505, like the Archangel Cathedral, and

completed in 1508. Virtually nothing is known of

its architect, Bon Friazin, who had no other recorded

structure in Moscow. Yet he was clearly a brilliant

engineer, for his bell tower—60 meters high, in two

tiers—withstood the fires and other disasters that

periodically devastated much of the Kremlin. The

tower, whose height was increased by an additional

21 meters during the reign of Boris Godunov, rests

on solid brick walls that are 5 meters thick at the

base and 2.5 meters on the second tier.

The most significant seventeenth-century ad-

dition to the Kremlin was the Church of the Twelve

Apostles, commissioned by Patriarch Nikon as part

of the Patriarchal Palace in the Kremlin. This large

church was originally dedicated to the Apostle

Philip, in implicit homage to the Metropolitan

Philip, who had achieved martyrdom for his op-

position to the terror of Ivan IV.

During the first part of the eighteenth century,

Russia’s rulers were preoccupied with the building

of St. Petersburg. But in the reign of Catherine the

Great, the Kremlin once again became the object of

autocratic attention. Although little came of

Catherine’s desire to rebuild the Kremlin in a neo-

classical style, she commissioned Matvei Kazakov

to design one of the most important state build-

ings of her reign: the Senate, or high court, in the

Kremlin. To create a triangular four-storied build-

ing, Kazakov masterfully exploited a large but

awkward lot wedged in the northeast corner of the

Kremlin. The great rotunda in its center provided

the main assembly space for the deliberations of the

Senate. To this day the rotunda is visible over the

center of the east Kremlin wall.

During the nineteenth century, Nicholas I ini-

tiated the rebuilding of the Great Kremlin Palace

(1839–1849), which had been severely damaged in

the 1812 occupation. In his design the architect

Konstantin Ton created an imposing facade for the

Kremlin above the Moscow River and provided a

stylistic link with the Terem Palace, the Faceted

Chambers, and the Annunciation Cathedral within

the Kremlin. Ton also designed the adjacent build-

ing of the Armory (1844–1851), whose historicist

style reflected its function as a museum for some

of Russia’s most sacred historical relics.

With the transfer of the Soviet capital to

Moscow in 1918, the Kremlin once again became

the seat of power in Russia. That proved a mixed

blessing, however, as some of its venerable monu-

ments, such as the Church of the Savior in the

Woods, the Ascension Convent, and the Chudov

Monastery, were destroyed in order to clear space

for government buildings. Only after the death of

KREMLIN

786

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Josef Stalin was the Kremlin opened once again to

tourists. The most noticeable Soviet addition to the

ensemble was the Kremlin Palace of Congresses

(1959–1961, designed by Mikhail Posokhin and

others). It has the appearance of a modern concert

hall (one of its uses), whose marble-clad rectangu-

lar outline is marked by narrow pylons and multi-

storied shafts of plate glass. The one virtue of its

bland appearance is the lack of conflict with the

historic buildings of the Kremlin, which remain the

most important cultural shrine in Russia.

See also: ARCHITECTURE; ARMORY; CATHEDRAL OF THE

ARCHANGEL; CATHEDRAL OF THE DORMITION;

MOSCOW; RED SQUARE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, William Craft. (1993). A History of Russian

Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hamilton, George Heard. (1983). The Art and Architecture

of Russia. New York: Penguin Books.

W

ILLIAM

C

RAFT

B

RUMFIELD

KREMLINOLOGY

Close analysis of the tense power struggles among

the Soviet leadership. A term coined during the last

days of the Stalin regime with the onset of the Cold

War.

Usually more than just a study of contending

personalities, or a “who-whom” (who is doing

what to whom), Kremlinology was an indispens-

able analysis of Soviet policy alternatives and their

implications for the West. It also turned out to be

a point of departure for any serious political his-

tory, inevitably connected to the ideas that drove

the Soviet regime and in the end determined its fate.

Western intelligence experts, academics, and jour-

nalists all made contributions to this pursuit. At-

tention was often focused on “protocol evidence,”

such as the order in which leaders’ names might

appear on various official lists, or the way they

were grouped around the leader in photographs.

However, since factional rivalry was usually ex-

pressed in ideological pronouncements and debates,

the most widely respected practitioners of Kremli-

nology were emigré writers who had direct expe-

rience of the ways of the Soviet communists. The

most famous of these was the Menshevik Boris

Nikolayevsky. Initially Kremlinologists centered on

quarrels among Josef Stalin’s subordinates in or-

der to get an idea of his policy alternatives and

turns. After Stalin’s death, Kremlinology mapped

out the succession struggle that occasioned the rise

of Nikita Khrushchev. It was again useful in un-

derstanding the politics of the Gorbachev reform

era and the destruction of Soviet power.

The domestic and foreign policy issues were de-

bated in the ideological language of the first great

Soviet succession struggle in the 1920s that brought

Stalin from obscurity to supreme power. After his

defeat and exile, Leon Trotsky explained Stalin’s rise

to the Western public as the victory of a narrow

insular national Communism, according to the slo-

gan “socialism in one country,” over his own in-

ternationalist idea of “permanent revolution.”

Materials from three Trotsky archives in the West

later showed these extreme positions to have been

less crucial to Stalin’s ascent than his complex ma-

neuvers for a centrist position between right and

left factions. Trotsky continued to analyze Soviet

politics during the Great Purge of 1936–1938 in his

Byulleten oppozitsy (Bulletin of the Opposition). This

was matched by the commentary of the well-con-

nected Moscow correspondents of the Menshevik

Sotsialistichesky vestnik (Socialist Courier).

For various reasons, the émigré writings had to

be read with caution. Often they were employed to

establish a position in the debate over the Russian

Question: What is the nature of the Soviet regime,

and has it betrayed the revolution? In 1936 Niko-

layevsky published the Letter of an Old Bolshevik,

presumably the confessions of Nikolai Bukharin in-

terviewed in Paris. It contained important informa-

tion indicating the origins of Stalin’s purges in a

1932 dispute over the anti-Stalin platform document

of Mikhail Ryutin. However, the Letter was drama-

tized and embellished by Nikolayevsky’s gleanings

from other sources. Some historians later rejected it

as spurious and even denied the existence of a Ryutin

Program. But during Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost

campaign the full text was published, reading quite

as Nikolayevsky had described it.

In Stalin’s last days, Nikolayevsky tried to in-

terpret the antagonism between Leningrad chief An-

drei Zhdanov and Stalin’s protégé Georgy Malenkov

by linking Zhdanov to Tito and the Yugoslav Com-

munists and Malenkov to Mao and the Chinese.

Later studies bore this out. The rise of Khrushchev

as successor to Stalin was charted by Boris Meiss-

ner, Myron Rush, Wolfgang Leonhard, and Robert

Conquest. Michel Tatu described Khrushchev’s fall

in 1964 and the central role played by Mikhail

Suslov, the ideological secretary.

KREMLINOLOGY

787

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Suslov loomed large in Soviet politics from this

point until his death at the end of the Brezhnev

regime in 1982. The ideological post was the cen-

ter of gravity for a regime of collective leadership

under the rubric of “stabilization of cadres.” That

Suslov died a few months before Brezhnev in 1982

meant he could not oversee the succession in the

interests of the Kremlin gerontocracy. The result

was a thorough housecleaning by Yuri Andropov

in his brief tenure. An even more thorough shakeup

by Mikhail Gorbachev followed. This would have

been unlikely had Suslov lived.

In defense of the Suslov pattern of collective

leadership, the Politburo tried its best to shore up

Yegor Ligachev in the ideological post as a limit on

Gorbachev. But Gorbachev managed to destroy all

the party’s fetters on his power by 1989, just as

he lost the East European bloc. After that, he be-

haved like a conscious student of Soviet succession

and proclaimed himself a centrist, balancing be-

tween the radical Boris Yeltsin and the weakened

consolidation faction of the Communist Party of

the Soviet Union (CPSU). The last stand of the lat-

ter was the attempted putsch of August 1991, the

failure of which left Gorbachev alone with a venge-

ful Yeltsin.

Commentary on the Yeltsin leadership of post-

Soviet Russia echoed some themes of Kremlinology,

especially in analysis of the power of the Yeltsin

group (“The Family”) and its relation to well-heeled

post-Soviet tycoons (“The Oligarchs”). However,

power in the Kremlin could no longer be read in

Communist ideological language and had to be

studied as with any other state. Kremlinology, or

analysis of Soviet power struggles, nevertheless re-

tains its value for political historians who can take

note of a recurrent programmatic alternance be-

tween a leftist Leningrad tendency and a rightist

Moscow line. The centrist who defeated the others

by timely turns was able to triumph in the three

great Soviet succession struggles.

See also: HISTORIOGRAPHY; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARI-

ONOVICH; SUSLOV, MIKHAIL ANDREYEVICH; UNITED

STATES, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Conquest, Robert. (1961). Power and Policy in the USSR.

New York: Macmillan.

D’Agostino, Anthony. (1998). Gorbachev’s Revolution,

1985–1991. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Gelman, Harry. (1984). The Brezhnev Politburo and the De-

cline of Détente. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Leonhard, Wolfgang. (1962). The Kremlin Since Stalin, tr.

Elizabeth Wiskemann. New York: Praeger.

Linden, Carl A. (1966). Khrushchev and the Soviet Leader-

ship, 1957–1964. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Nicolaevsky, Boris. (1965). Power and the Soviet Elite. New

York: Praeger..

Rush, Myron. (1974). How Communist States Change Their

Rulers. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

A

NTHONY

D’A

GOSTINO

KRITZMAN, LEV NATANOVICH

(1890–c. 1937), Soviet economist and agrarian ex-

pert.

Born in 1890, Kritzman became a Menshevik in

1905. After a long period in exile, he returned to

Russia in early 1918 when he joined the Bolshevik

Party. An expert in economic policy and a strong

advocate of planning, he held various posts in the

Supreme Council for the National Economy and in

1921 joined the Presidium of Gosplan (State Plan-

ning Agency).

In addition to his professional duties, he pub-

lished numerous works on planning and the econ-

omy in which he argued for introducing a single

economic plan. He was criticized by Lenin for this

position. After the introduction of the New Eco-

nomic Policy in 1921, Kritzman, together with Ya.

Larin, Leon Trotsky, and Yevgeny Preobrazhensky,

continued to advocate an extension of state plan-

ning. During the 1920s, Kritzman produced a num-

ber of important works, including a major study of

war communism, Geroichesky period velikoi russkoi

revolyutsy (The Heroic Period of the Great Russian Rev-

olution), still one of the key analyses of economic

policy in the early Soviet period. As director of the

Agrarian Institute of the Communist Academy

from 1925 and editor of its journal Na Agrarnom

Fronte (On the Agricultural Front), he promoted em-

pirical research into class differentiation among the

peasantry and called for greater state support for

socialized agriculture. He also served during his ca-

reer as assistant director of the Central Statistical

Administration and a member of the editorial boards

of Pravda, Problemy Ekonomiki (Problems of Econom-

ics) and the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Stalin’s launch

of mass collectivisation and dekulakization in late

1929 rendered Kritzman’s work and ideas obsolete

by eradicating the individual household farm. After

KRITZMAN, LEV NATANOVICH

788

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

some years conducting private research, he was ar-

rested and died in prison either in 1937 or 1938.

See also: COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICULTURE; NEW ECO-

NOMIC POLICY; PEASANT ECONOMY; WAR COMMU-

NISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cox, Terry. (1986). Peasants, Class and Capitalism. The

Rural Research of L.N. Kritzman and his School. Ox-

ford: Clarendon Press.

Solomon, Susan Gross. (1977). The Soviet Agrarian De-

bate: A Controversy in Social Science 1923–1929. Boul-

der, CO: Westview Press.

N

ICK

B

ARON

KRONSTADT UPRISING

The Kronstadt Uprising was a well-known revolt

against the Communist government from March 1

to 18, 1921, at Kronstadt, a naval base in the Gulf

of Finland, base of the Russian Baltic Fleet, and a

stronghold of radical support for the Petrograd So-

viet in 1917.

By early 1921 the Bolshevik government had

defeated the armies of its White opponents, but had

also presided over a collapse of the economy and

was threatened by expanding Green rebellions in

the countryside. The Kronstadt garrison was disil-

lusioned by reports from home of the depredations

of the food requisitioning detachments, and by the

corruption and malfeasance of Communist leaders.

In response to strikes and demonstrations in Pet-

rograd in February 1921, a five-man revolution-

ary committee took control of Kronstadt. It purged

local administration, reorganized the trade unions,

and prepared for new elections to the soviet, while

preparing for a Communist assault. It called for an

end to the Communist Party’s privileges; for new,

free elections to soviets; and an for end to forced

grain requisitions in the countryside.

Communist reaction was quick. A first attack

on March 8 resulted only in bloodshed; however,

on March 18 a massive assault across the ice by

50,000 troops, stiffened by Communist detach-

ments and several hundred delegates to the Tenth

Party Congress and led by civil war hero Mikhail

Tukhachevsky, captured the island stronghold.

Thousands of Kronstadt activists died in the assault

or in the repression that followed.

The Kronstadt rebellion, along with the Green

Movement, presented a direct threat to Communist

control. While the rebellions were put down, their

threat led to important policy changes at the Tenth

Party Congress, including the abandonment of War

Communism (the grain monopoly and forced grain

requisitions) and a ban on factions within the Com-

munist Party.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; GREEN MOVEMENT;

SOCIALIST REVOLUTIONARIES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avrich, Paul. (1970). Kronstadt 1921. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Getzler, Israel. (1983). Kronstadt, 1917–1921: The Fate of

a Soviet Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

A. D

ELANO

D

U

G

ARM

KROPOTKIN, PYOTR ALEXEYEVICH

(1842–1921), Russian revolutionary.

Born into a family of the highest nobility,

Kropotkin (the “Anarchist Prince,” according to his

1950 biographer George Woodcock) swam against

the current of convention all his life. He received his

formal education at home and then at the Corps

of Pages in St. Petersburg, graduated in 1862, and,

to the tsar’s astonishment, requested a posting to

Siberia rather than the expected court career. There

he remained until 1867. Siberia was a liberation for

Kropotkin, contrary to the experience of others. He

participated as a geographer and naturalist in expe-

ditions organized by the Imperial Russian Geograph-

ical Society (IRGS). He was also entering his parallel

career as a revolutionary: for him, Russia’s Age of

Great Reforms was that of the discovery of un-

changing corruption among Siberian state officials.

In 1867 Kropotkin returned to St. Petersburg

where he enrolled at the University (he never grad-

uated), supporting himself by working for the

IRGS. His scientific reputation grew and in 1871 he

was offered the post of IRGS secretary, which he

rejected. Events in his own life (the death of his

tyrannical father), in Russia (the growth of a rev-

olutionary student movement), and in the world

(the Paris Commune) strengthened his revolution-

ary feelings. In 1872 he visited Switzerland for the

KROPOTKIN, PYOTR ALEXEYEVICH

789

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

first time to discover more about the International

Workingmen’s Association and on his return to

Russia began to frequent the Chaikovsky Circle.

As his 1976 biographer Martin Miller revealed,

Kropotkin authored the Circle’s principal pamphlet,

“Must We Examine the Ideal of the Future Order?”

(1873).

Kropotkin was by this time (though the title

was yet to be invented) an anarchist-communist—

that is, he advocated the destruction of state

tyranny over society (as anarchist predecessors like

William Godwin, Pierre Proudhon, and Mikhail

Bakunin had done) on one hand, while on the other

he sought a communist, egalitarian transformation

of society (like Karl Marx, only without using the

authority of the state). This paradox required the

dissolution of national government and its post-

revolutionary replacement by a free federation of

small communes, a local government freely ad-

ministered from below rather than national and

imposed from above. Revolutionaries from privi-

leged backgrounds must organize the preceding

popular revolt by propaganda and persuasion only:

Workers and peasants must make the revolution

themselves.

In March 1874 Kropotkin was arrested for his

revolutionary activities and interrogated over a

two-year period. Moved to a military hospital, he

was liberated in a complex, sensational escape or-

ganized by his comrades. Kropotkin continued his

revolutionary career in the Jura Federation, Switzer-

land, comprising the anarchist sections of the In-

ternational, and from early 1877 began for the first

time to take part in public political life: demon-

strating, making speeches, attending congresses,

writing articles. This activity is chronicled in detail

in Caroline Cahm’s 1983 biography. Around 1880,

the issue of terrorism or “propaganda by the deed,”

as was the expression of the time, arose. This was

crystalized by the assassination of Alexander II in

1881. Although not approving assassination as a

political method, Kropotkin was unwilling to con-

demn the assassins, explaining their actions as the

result of impotent desperation. At the end of 1882

he was arrested in France for revolutionary activ-

ity in which, for once, he had not participated. Sen-

tenced to five years’ imprisonment, he was released

following international pressure in early 1886 and

settled in London, England.

For a living and for the cause, Kropotkin now

lectured throughout Britain and wrote for numer-

ous publications. His principal fame during the

British period derived from his books, including In

Russian and French Prisons (1887), Memoirs of a Rev-

olutionist (1899), Fields, Factories, and Workshops

(1899), Mutual Aid (1902), Modern Science and Anar-

chism (1903), Russian Literature (1905), The Terror in

Russia (1909), and The Great French Revolution (1909).

With British comrades, he launched the anarchist

journal Freedom. He wrote frequently for political

publications in several languages. He was greatly en-

couraged by the 1905 revolution in Russia.

Kropotkin’s writings during these years of ex-

ile are parts of an ongoing argument with those

hegemonic Victorian thinkers Thomas Malthus,

Herbert Spencer, and Charles Darwin. He takes is-

sue with Malthus’s bleak vision to argue that hu-

manity’s future is not limited by its reproductive

success, but by science and equality. Nature shows

the role of mutual aid in its evolution, analogous

to the freely cooperating communes of postrevolu-

tionary humanity. Anarchist communism is not

merely desirable, but inevitable. Kropotkin’s opti-

mistic view of science no longer commands respect,

but to many his works beckon us to a wonderful

future.

In 1917, in old age, Kropotkin was able to re-

turn to revolutionary Russia. He worked for a

while on various federalist projects and died in

Dmitrov, a Moscow province. His last major work,

Ethics, was published posthumously and incom-

plete in 1924.

See also: ANARCHISM; BAKUNIN, MIKHAIL ALEXAN-

DROVICH; IMPERIAL RUSSIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cahm, Caroline. (1989). Kropotkin and the Rise of Revolu-

tionary Anarchism 1872–1886. Cambridge, UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Cahm, Caroline, Colin Ward, and Ian Cook. (1992). P. A.

Kropotkin’s Sesquicentennial: A Reassessment and Trib-

ute. Durham: University of Durham, Centre for Eu-

ropean Studies.

Miller, Martin A. (1976). Kropotkin. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.

Slatter, John (ed.). (1984). From the Other Shore: Russian

Political Emigrants in Britain 1880–1917. London:

Frank Cass.

Woodcock, George, and Ivan Avakumovic. (1950). The

Anarchist Prince: A Biographical Study of Peter

Kropotkin. London: Boardman.

J

OHN

S

LATTER

KROPOTKIN, PYOTR ALEXEYEVICH

790

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

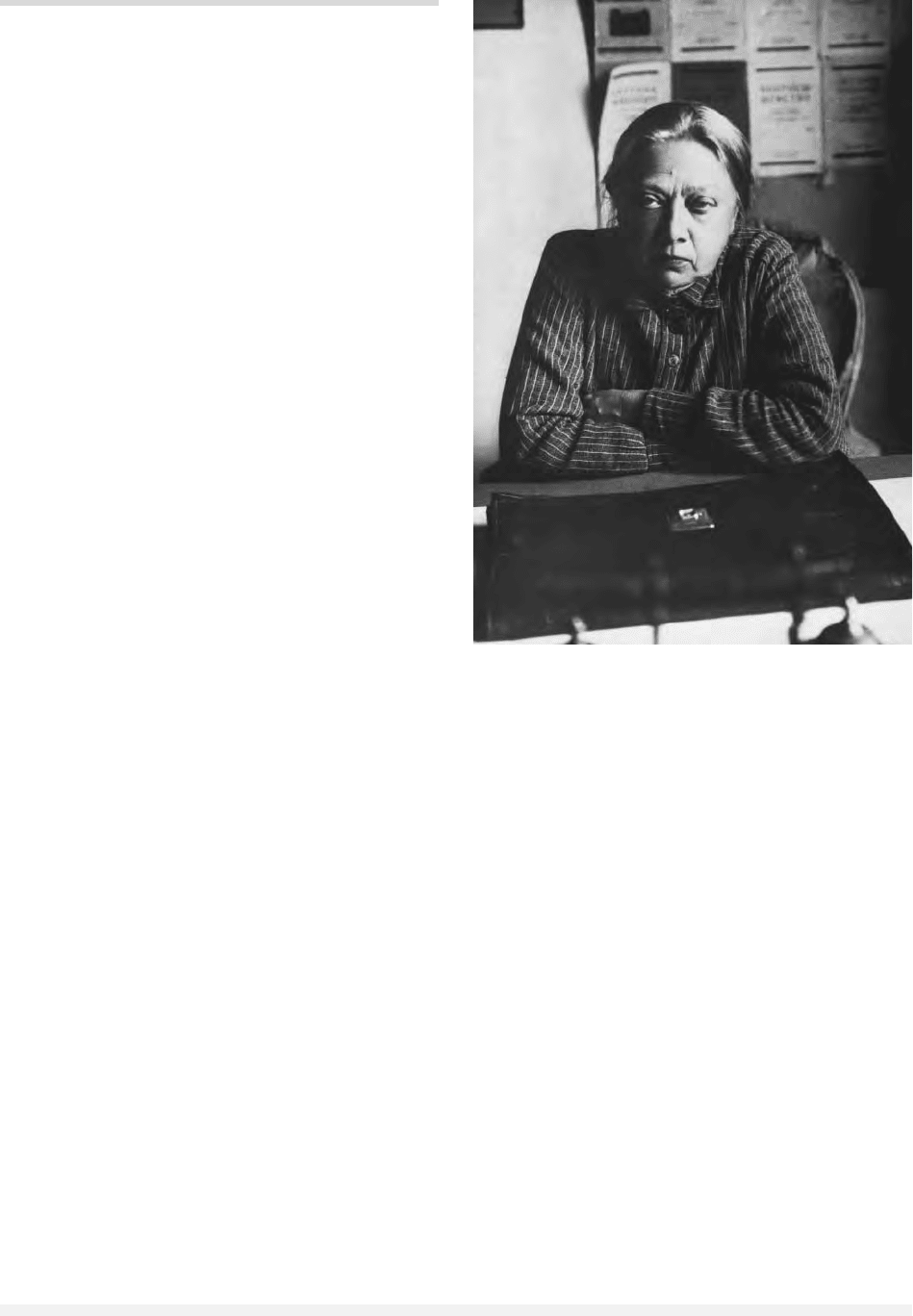

KRUPSKAYA, NADEZHDA

KONSTANTINOVNA

(1869–1939), revolutionary, educator, head of

Glavpolitprosvet (the Chief Committee for Political

Education) and deputy head of the Commissariat

of Enlightenment, full member of the Central Com-

mittee of the Communist Party (1927–1939), wife

of Vladimir Ilich Lenin.

A native of St. Petersburg, Nadezhda Krup-

skaya developed an early and lifelong interest in ed-

ucation, especially that of adults. Beginning in the

1890s, she taught in workers’ evening and adult

education schools. In Marxist circles she met

Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov (Lenin). When she and

Lenin were both arrested in 1895 and 1896, she

followed him to Siberia as his fiancée and later as

his wife. While in exile, Krupskaya wrote her most

famous work, The Woman Worker (first published

in 1901 and 1905). Here she explored the problems

faced by women as workers and mothers.

From 1901 to 1917 Krupskaya shared Lenin’s

life in exile abroad, helping to direct his correspon-

dence and build up the organization of the Party.

She worked on the editorial boards of the journals

Rabotnitsa, Iskra, Proletary, and Sotsial-Demokrat.

She also began writing about theories of progres-

sive American and European education, especially

those of John Dewey. In the 1920s these ideas on

education were to have some impact on Soviet

schooling, though they were then reversed in the

1930s.

After 1917 she headed the newly created Ex-

tra-Curricular Department of the Commissariat of

Education, which was later replaced by the Chief

Committee on Political Education (Glavpolitprosvet).

She also worked in the zhenotdel (the women’s sec-

tion of the Party), editing the journal Kommunistka,

but never heading the section.

In 1922 and 1923, when Lenin was seriously

incapacitated with illness, Krupskaya quarreled

badly with Josef Stalin, whom she found rude and

boorish. When Lenin died in January 1924, Krup-

skaya found herself isolated and increasingly

drawn to side with the Leningrad Opposition led

by Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. By the fall

of 1926, however, she had defected from the Op-

position. From 1927 to 1939 she served as a full

member of the (now much weakened) Central

Committee of the Party. During the height of the

Purges, she tried to save some of Stalin’s victims,

including Yuri Pyatakov, but without success.

Although Stalin gave a eulogy at her funeral in

1939, her works were suppressed until Nikita

Khrushchev’s Thaw.

Historians have tended to minimize Krupskaya’s

importance, viewing her primarily as Lenin’s wife.

Yet she played a crucial role in establishing the

Party, building up the political education appara-

tus that reached millions of people, and keeping

women’s issues on the political agenda.

See also: ARMAND, INESSA; EDUCATION; LENIN, VLADIMIR

ILICH; ZHENOTDEL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McNeal, Robert H. (1972). Bride of the Revolution. Ann

Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Noonan, Norma C. (1991). “Two Solutions to the Zhen-

skii Vopros in Russia and the USSR, Kollontai and

KRUPSKAYA, NADEZHDA KONSTANTINOVNA

791

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Nadezhda Krupskaya, wife of Vladimir Lenin, seated at her

desk. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

Krupskaia: A Comparison.” Women and Politics

2(3):77–100.

Stites, Richard. (1975). “Kollontai, Inessa, and Krupskaia:

A Review of Recent Literature.” Canadian-American

Slavic Studies 9(1):84–92.

Stites, Richard. (1978). The Women’s Liberation Movement in

Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860–1930.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wood, Elizabeth A. (1997). The Baba and the Comrade:

Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

E

LIZABETH

A. W

OOD

KRYLOV, IVAN ANDREYEVICH

(1769–1844), writer, especially of satirical fables,

who is often called the “Russian Aesop.”

The son of a provincial army captain who died

when he was ten, Krylov had little formal educa-

tion but significant artistic ambitions. Entering the

civil service in Tver, Krylov was subsequently

transferred to the imperial capital of St. Petersburg

in 1782, which gave him access to the most promi-

nent of cultural circles. Although he began his lit-

erary career penning comic operas, when he joined

Nikolai Novikov and Alexander Radishchev on the

editorial board of the satirical journal Pochta dukhov

(Mail for Spirits) in 1789, he became recognized as

a leading figure in Russia’s Enlightenment. When

the French Revolution made enlightened principles

particularly dangerous during the last years of the

reign of Catherine the Great, Krylov left St. Peters-

burg to escape the more severe fates suffered by his

coeditors. He spent five years traveling and work-

ing in undistinguished positions.

In 1901, with the assumption of the throne by

Catherine’s liberally minded grandson, Alexander I,

Krylov moved to Moscow and resumed his literary

career. Five years later, he returned to St. Petersburg,

returning also to satire. He began translating the

works of French storyteller Jean La Fontaine, and

in the process discovered his own talents as a fab-

ulist. Moreover, his originality coincided with the

intellectual movement to create a national litera-

ture for Russia. His new circle was as illustrious as

the old, including the poet Alexander Pushkin, who

was the guiding spirit behind the evolution of Russ-

ian into a literary language.

Krylov’s fables, which numbered more than

two hundred, featured anthropomorphized animals

who made political statements about contempo-

rary Russian politics. This satirical style allowed

him to describe repressive aspects of the autocracy

without suffering the wrath of Catherine’s heirs.

He received government sinecure with a position in

the national public library, where he worked for

thirty years. Many of his characters and aphorisms

continue to resonate in Russian popular culture.

See also: CATHERINE II; ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF;

PUSHKIN, ALEXANDER SERGEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Krylov, Ivan. (1977). Krylov’s Fables, tr. with a preface

by Sir Bernard Pares. Westport, CT: Hyperion Press.

Stepanov, N. L. (1973). Ivan Krylov. New York: Twayne.

L

OUISE

M

C

R

EYNOLDS

KRYUCHKOV, VLADIMIR

ALEXANDROVICH

(b. 1924), Soviet police official; head of the KGB

from 1988 to 1991.

Born in Volgograd, Russia, Vladimir Kryuchkov

joined the Communist Party in 1944 and became a

full-time employee of the Communist Youth League

(Komsomol). In 1946 Kryuchkov embarked on a

legal career, working as an investigator for the

prosecutor’s office and studying at the All-Union

Juridical Correspondence Institute, from which he

received a diploma in 1949. Kryuchkov joined the

Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1951 and en-

rolled as a student at the Higher Diplomatic School

in Moscow. He received his first assignment abroad

in 1955, when he was sent to Hungary to serve un-

der Soviet Ambassador Yuri Andropov. Kryuchkov

was in Budapest during the Soviet invasion in 1956

and was an eyewitness to the brutal suppression of

Hungarian nationalists by Soviet troops. After re-

turning to Moscow in 1959, he worked in the Cen-

tral Committee Department for Liaison with

Socialist Countries, which his former supervisor

Andropov now headed. In 1967, when Andropov

was appointed to the leadership of the KGB, the So-

viet police and intelligence apparatus, he brought

Kryuchkov, who rose to the post of chief of the

KGB’s First Chief Directorate (foreign intelligence) in

1977. In 1988 Soviet party leader Mikhail Gor-

bachev appointed Kryuchkov chairman of the KGB.

Although Kryuchkov voiced public support for

Gorbachev’s liberal reforms, he grew increasingly

KRYLOV, IVAN ANDREYEVICH

792

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY