Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

mer-fall campaign, which by late September col-

lapsed the entire German front from Velikie Luki

to the Black Sea and propelled Red Army forces for-

ward to the Dnieper River. After Kursk the only

unresolved questions regarded the duration and fi-

nal cost of Red Army victory.

See also: WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erickson, John. (1983). The Road to Berlin. Boulder, CO:

Westview Press .

Glantz, David M., and House, Jonathan M. (1999). The

Battle of Kursk. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Glantz, David M., and Orenstein, Harold S, eds. (1999).

The Battle for Kursk 1943: The Soviet General Staff

Study. London: Frank Cass.

Manstein, Erich von. (1958). Lost Victories. Chicago:

Henry Regnery.

Zetterling Niklas, and Frankson, Anders. (2000). Kursk

1943: A Statistical Analysis. London: Frank Cass.

D

AVID

M. G

LANTZ

KURSK SUBMARINE DISASTER

On Saturday, August 12, 2000, the nuclear-

powered cruise-missile submarine Kursk (K-141),

one of Russia’s most modern submarines, was lost

with all 118 crewmembers during a large-scale ex-

ercise of the Russian Northern Fleet in the Barents

Sea. The Kursk sank just after its commander, Cap-

tain First Rank Gennady Lyachin, informed the ex-

ercise directors that the submarine was about to

execute a mock torpedo attack on a surface target.

Exercise controllers lost contact with the vessel

and fleet radio operators failed to reestablish com-

munication. Shortly after the Kursk’s last com-

munication, Russian and Western acoustic sensors

recorded two underwater explosions, one smaller

and a second larger (the equivalent of five tons of

TNT).

Russian surface and air units began a search

for the submarine and in the early evening located

a target at a depth of 108 meters (354.3 feet) and

about 150 kilometers (93 miles) from the North-

ern Fleet’s base at Murmansk. Russian undersea

rescue units were dispatched to the site. The com-

mand of the Northern Fleet was slow to announce

the possible loss of the submarine or to provide re-

liable information on the event. On August 13

Admiral Vyacheslav Popov, commander of the

Northern Fleet, conducted a press conference on the

success of the exercise but did not mention the pos-

sible loss of the Kursk. A Russian undersea appa-

ratus reached the Kursk on Sunday afternoon and

reported that the submarine’s bow had been se-

verely damaged by an explosion. The rescue crews

suggested three hypotheses to explain the sinking:

an internal explosion connected with the torpedo

firing, a possible collision with another submarine

or surface ship, or the detonation of a mine left

over from World War II.

On Monday, August 14, the Northern Fleet’s

press service began to report its version of the dis-

aster. The reports emphasized the absence of nu-

clear weapons, the stability of the submarine’s

reactors, and the low radioactivity at the site. It

also falsely reported that communications had been

reestablished with the submarine. The Northern

Fleet and the Naval High Command in Moscow re-

ported the probable cause of the disaster as a col-

lision with a foreign submarine. While there were

reports of evidence supporting this thesis, none was

ever presented to confirm the explanation, and both

the United States and Royal navies denied that any

of their submarines had been involved in any col-

lision with the Kursk. The Russian Navy was also

reluctant to publish a list of those on board the

submarine. The list, leaked to the newspaper Kom-

somolskaya pravda (Komsomol Truth), was pub-

lished on August 18. The Russian Navy’s initial

unwillingness to accept foreign assistance in the

rescue operation and failure to get access to the

Kursk undermined its credibility.

When President Vladimir Putin learned of the

crisis while on vacation in Sochi, he created a State

Commission under Deputy Prime Minister Ilya Kle-

banov to investigate the event. Putin invited for-

eign assistance in the rescue operation. British and

Norwegian divers successfully entered the Kursk on

August 21 and found no survivors. Putin had kept

a low profile during the rescue phase and did not

directly address the relatives of the crew until Au-

gust 22. At that time Putin vowed to recover the

crew and vessel. In the fall of 2001 an international

recovery team lifted the Kursk, minus the damaged

bow. The hull was brought back to a dry dock at

Roslyakovo. In December 2001, on the basis of in-

formation regarding the preparation for the exer-

cise in which the Kursk was lost, President Putin

fired fourteen senior naval officials, including Ad-

miral Popov. Preliminary data from the Klebanov

KURSK SUBMARINE DISASTER

803

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

commission seems to confirm that the submarine

sank as a result of a detonation of an ultra high-

speed torpedo, skval-type. On June 18, 2002, Ilya

Klebanov confirmed that the remaining plausible

explanation for the destruction of the submarine

was an internal torpedo explosion.

See also: MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET; PUTIN,

VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Burleson, Clyde. (2002). Kursk Down. New York: Warner

Books.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

KUSTAR

Cottage worker, home worker; a peasant engaged

in cottage industry (kustarnaya promyshlennost) to

earn cash, usually in combination with agricultural

production.

Cottage industry became an important source

of income for rural peasants in some parts of Rus-

sia by the sixteenth century and developed exten-

sively during the nineteenth century, producing a

wide range of wooden, textile, metal, and leather

goods. It was usually a family enterprise, although

some peasants formed producer cooperatives and

worked under the supervision of an elected elder.

Some cottage workers independently produced and

sold their production, while others participated in

a putting-out system in which they worked for a

middleman who furnished them with raw or semi-

finished materials and collected and marketed the

finished products. By the beginning of the twenti-

eth century, the state, zemstvos, and cooperatives

had established schools, credit banks, and ware-

houses to assist cottage workers in producing and

marketing a wide variety of goods.

The socioeconomic position of Russian cottage

workers was the subject of many debates in the

decades preceding the revolution. Populists argued

that most cottage workers remained peasant agri-

culturists and engaged in cottage industry only to

supplement their earnings from agriculture, while

Marxists contended that cottage workers were be-

coming proletarianized and wholly dependent on

the income they earned from selling manufactured

goods to middlemen.

Despite increasing competition from factories,

cottage industry continued to account for a large

share of Russian manufactured goods until the end

of the tsarist regime, and enjoyed a brief revival

in the 1920s under the New Economic Policy.

Notwithstanding the importance of cottage indus-

try in the Russian economy, there is no reliable data

for the number of cottage workers in the country

as a whole. Estimates range from 2.5 million to 15

million peasants engaged in cottage industry at the

end of the nineteenth century.

See also: PEASANT ECONOMY; PEASANTRY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blum, Jerome. (1961). Lord and Peasant in Russia from

the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Crisp, Olga. (1976). Studies in the Russian Economy Before

1914. London: Macmillan.

Gatrell, Peter. (1986). The Tsarist Economy, 1850–1914.

London: Batsford.

Salmond, Wendy R. (1996). Arts and Crafts in Imperial

Russia: Reviving the Kustar Art Industries, 1970–1917.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

E. A

NTHONY

S

WIFT

KUTUZOV, MIKHAIL ILARIONOVICH

(1745–1813), general, renowned for his victory

over Napoleon.

At the age of sixty-seven, Mikhail Kutuzov led

the Russian armies to victory over Napoleon in the

War of 1812 and created the preconditions for their

final victory in the campaigns of 1813 and 1814.

Kutuzov first distinguished himself in extensive

service against the Turks during the reign of

Catherine II. He served in the Russo-Turkish War

of 1768–1774, first on the staff of Petr Rumyant-

sev’s army, and then in line units with Vasily Dol-

gorukov’s Crimean Army. In combat in the Crimea

in 1774 he was shot through the head and lost an

eye. When he returned to service, he took com-

mand of the Bug Light Infantry Corps of Field Mar-

shal Alexander Suvorov’s army. He led his corps

into combat with the Turks once again when war

broke out in 1788. He was wounded again at the

siege of Ochakov in that year, but continued to

command troops throughout the war, serving un-

der Grigory Potemkin and Alexander Suvorov. Fol-

KUSTAR

804

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

lowing the end of hostilities, Kutuzov served in a

number of senior positions, including ambassador

to Turkey, commander of Russian forces in Fin-

land, and military governor of Lithuania. It seemed

that his days as an active commander had passed.

In September 1801 he retired.

The Napoleonic Wars put a quick end to Ku-

tuzov’s ease. When war threatened in 1805,

Alexander I designated Kutuzov, now a field mar-

shal, commander of the leading Russian expedi-

tionary army sent to cooperate with the Austrians.

On the way to the designated rallying point of

Braunau, on the Austrian border with Bavaria, Ku-

tuzov learned of the surrender of the Austrian

army at Ulm on October 20. Now facing French

forces four times stronger than his army, Kutuzov

began a skillful and orderly withdrawal to the east,

hoping to link up with reinforcements on their way

from Russia. Desperate rearguard actions made

possible this retreat, which included even a brief

victory over one of Napoleon’s exposed corps at the

Battle of Dürnstein. Despite Napoleon’s best efforts,

Kutuzov managed to withdraw his army and link

up with reinforcements, headed by the tsar him-

self, at Olmütz in Moravia in late November. Fooled

into thinking that Napoleon was weak, Alexander

overruled the more cautious Kutuzov repeatedly in

the days that followed, ordering the field marshal

to launch an ill-advised attack on the French at

Austerlitz on December 2. Wounded once again

while trying to rally his men to hold a critical po-

sition, Kutuzov helped Alexander salvage what

could be saved from the wreckage, and then com-

manded the army during its retreat back to Russ-

ian Poland.

Blaming Kutuzov for his own mistakes,

Alexander relegated Kutuzov to the post of mili-

tary governor general of Kiev. It was not long be-

fore Kutuzov returned to battle, however, for he

joined the Army of Moldavia in 1808 and com-

manded large units in the war against the Turks

(1806–1812). In 1809 he was relieved once more

and sent to serve as governor general of Lithuania,

but in 1811 Alexander designated Kutuzov as the

commander of the Russian army fighting the

Turks. In the shadow of the impending Franco-

Russian war, Kutuzov waged a skillful campaign

that resulted in the Peace of Bucharest bare weeks

before the French invasion began.

The War of 1812 was Kutuzov’s greatest cam-

paign. Alexander relieved Mikhail Barclay de Tolly

after his retreat from Smolensk and appointed Ku-

tuzov, hoping thereby to see a more active resis-

tance to the French onslaught. Kutuzov, however,

continued Barclay de Tolly’s program of retreating

in the face of superior French numbers, until he

stood to battle at Borodino. Following that com-

bat, Kutuzov continued his withdrawal, eventually

abandoning Moscow and retreating to the south.

He defeated Napoleon’s attempt to break out to the

richer pastures of Ukraine at the Battle of Malo-

yaroslavets, and then harried the retreating French

forces all the way to the Russian frontier and be-

yond. He died on April 28, 1813, a few weeks af-

ter having been relieved of command of the Russian

armies for the last time.

See also: ALEXANDER I; AUSTERLITZ, BATTLE OF;

BORODINO, BATTLE OF; BUCHAREST, TREATY OF;

FRENCH WAR OF 1812; MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA;

NAPOLEON I; RUSSO-TURKISH WARS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Parkinson, Roger. (1976). The Fox of the North: The Life of

Kutuzov, General of War and Peace. London: P. Davies.

F

REDERICK

W. K

AGAN

KUYBYSHEV, VALERIAN VLADIMIROVICH

(1888–1935), Bolshevik, politician, Stalinist, active in

civil war and subsequent industrialization initiatives.

Active in the Social Democratic Party from

1904, Valerian Kuybyshev was an Old Bolshevik

who played a major role in the Russian Civil War

as a political commissar with the Red Army. Hav-

ing fought on the Eastern Front against the forces

of Admiral Kolchak, he was instrumental in con-

solidating Soviet power in Central Asia following

the civil war. Kuybyshev subsequently held several

important political posts: chairman of the Central

Control Commission (1923); chairman of the

Supreme Council of the Soviet Economy (1926);

member of the Politburo (1927); chairman of Gos-

plan (1930); and deputy chairman of both the

Council of People’s Commissars and Council of La-

bor and Defense (1930).

A staunch Stalinist throughout the 1920s,

Kuybyshev advocated rapid industrialization and

supported Stalin in the struggle against the Right

Opposition headed by Nikolai Bukharin. Kuyby-

shev’s organizational skills and boundless energy

were critical in launching the First Five-Year Plan

KUYBYSHEV, VALERIAN VLADIMIROVICH

805

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

in 1928. However, in the early 1930s Kuybyshev

became associated with a moderate bloc in the Polit-

buro who opposed some of Stalin’s more repres-

sive political policies.

Kuybyshev died suddenly on January 26,

1935, ostensibly of a heart attack, but there is some

speculation that he may have been murdered by

willful medical mistreatment on the orders of Gen-

rich Yagoda—an early purge following the assas-

sination of Sergei Kirov. Whatever the actual

circumstances of his death, he was given a state

funeral, and the city of Samara was renamed in his

honor.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; INDUSTRIALIZATION,

RAPID; RED ARMY; RIGHT OPPOSITION; STALIN, JOSEF

VISSARIONOVICH.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Conquest, Robert. (1990). The Great Terror: A Reassess-

ment. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kuibyshev, V. V. (1935). Personal Recollections. Moscow.

K

ATE

T

RANSCHEL

KUZNETSOV, NIKOLAI GERASIMOVICH

(1904–1974), commissar of the navy and admiral

of the fleet of the Soviet Union.

A native of the Vologda area, from a peasant

background, Kuznetsov was born on July 11,

1904. He joined the Red Navy in 1919, served dur-

ing the civil war with North Dvina Flotilia, and

fought against the Allied Expeditionary Force and

the Whites. He served in the Black Sea Fleet begin-

ning in 1921, became a Communist Party member

in 1925, and graduated from the Frunze Naval

School in 1926 and the naval Academy in 1932.

He served as assistant commander of the cruiser

Krasnyi Kavkaz (1932–1934), and as commander

of the cruiser Chervona Ukraina (1934–1936).

Kuznetsov served as naval attaché in Spain and was

the Soviet advisor to the Republican Navy during

the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1937. After

returning from Spain, he served as the first deputy

commander of the Pacific Fleet (commissioned Au-

gust 15, 1937) and as commander of the Pacific

Fleet from 1938 to 1939.

Kuznetsov was recalled to Moscow in March

of 1939 and was appointed as the first deputy.

Days later, on March 12, 1939, he was appointed

commissar of the Navy. He held this position un-

til 1946, leading the Soviet Navy during World War

II with mixed results. The Navy did not perform

well against an enemy whose naval interests were

elsewhere, and it remained in a defensive mode for

most of the war, suffering heavily at the hands of

the Luftwaffe. The Soviet retreat from the Baltics

proved to be a fiasco, but the Navy performed bet-

ter in the evacuation of Odessa and Sevastopol. Two

landings in Kerch in 1942 and 1943 ended in dis-

aster, but the blame was not confined to the Navy.

The Volga Flotilla played a significant part in the

defense of Stalingrad, and the stationary Baltic Fleet

provided artillery support in the Battle of Leningrad.

Throughout 1944 and 1945, a number of landings

took place behind the enemy lines, which resulted

in little gain and heavy losses.

The outspoken Kuznetsov may have offended

Stalin, although he blamed the Navy’s shortcom-

ings on Andrei Alexandrovich Zhdanov, the polit-

ical commissar of the Navy before the war. In

February 1946, Stalin divided the Baltic and Pacific

Fleets into four separate units, a decision Kuznetsov

opposed. The end result was the removal of

Kuznetsov. He was forced to face a Court of Honor,

where several admirals were accused of passing

naval secrets to the Allies during the war.

Kuznetsov was reduced to the rank of rear admi-

ral on February 3, 1948, and was sent to the re-

serves, but was called back and appointed as deputy

commander in chief in the Far East for the Navy

on June 12, 1948. On February 20, 1950, he was

reappointed to his old job of commander of the Pa-

cific Fleet. Stalin, encouraged by Lavrenti Beria

(head of the secret police), also recalled him, and

once again named him commissar of the Navy on

July 20, 1951. He kept this position even after

Stalin’s death.

On the night of October 29, 1955, the Soviet

Navy suffered its greatest peacetime disaster when

the battleship Novorossisk blew up in Sevastopol,

with the loss of 603 lives. Kuznetsov was blamed

for this disaster, and was removed from his posi-

tion. On February 15, 1956, he was once again re-

duced in rank and forcibly retired. Kuznetsov’s

reputation was rehabilitated only in 1988, fourteen

years after his death and after a long campaign by

his widow. During his roller-coaster career, he was

rear admiral twice, vice admiral three times, and

admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union twice. He

was deputy to the Supreme Soviet three times, and

served the Eighteenth Party Congress in 1939. He

was also declared a Hero of the Soviet Union on

KUZNETSOV, NIKOLAI GERASIMOVICH

806

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

September 14, 1945. The Soviet naval policy

changed after Kuznetsov, who was mainly a sur-

face-ship admiral, to emphasize an oceanic navy

that was heavily dependent on a large fleet of sub-

marines, missile cruisers, and even the occasional

aircraft carrier.

See also: BALTIC FLEET; BLACK SEA FLEET; MILITARY, IM-

PERIAL; PACIFIC FLEET

M

ICHAEL

P

ARRISH

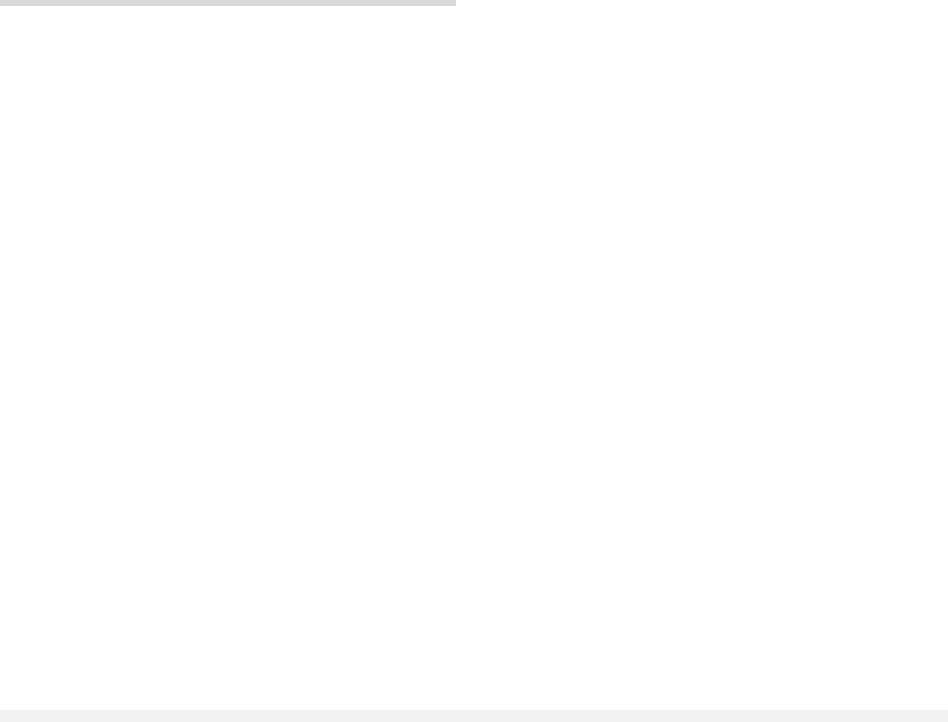

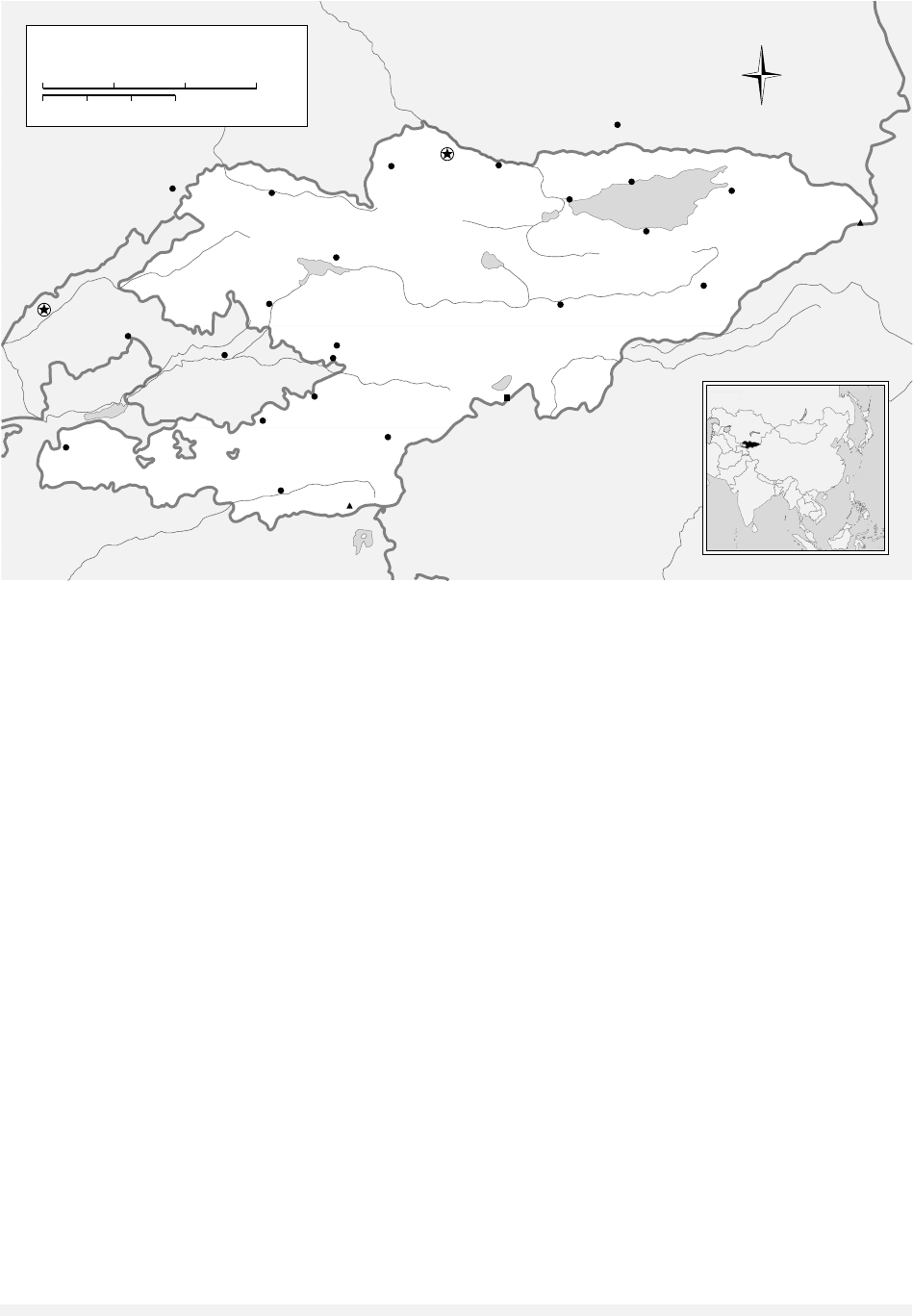

KYRGYZSTAN AND KYRGYZ

The Kyrgyz are a nomadic people of Turkic descent

living in the northern Tien Shan mountain range.

Originally chronicled as living in the region of

what is today eastern Siberia and Mongolia, the

Kyrgyz migrated westward more than a thousand

years ago and settled in the mountains of Central

Asia. At the beginning of the twenty–first century,

ethnic Kyrgyz live in the countries of Kazakhstan,

China, Russia, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. The ma-

jority of the Kyrgyz live in the country of the Kyr-

gyz Republic (known as Kyrgystan), a former

republic of the Soviet Union that received its inde-

pendence in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed.

With an area of 76,000 square miles (198,500

square kilometers), the mountainous, landlocked

republic is nestled between Kazakhstan, China,

Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The Kyrgyz Republic’s

population is 4,822,166, of which 2,526,800

(52.4%) are ethnic Kyrgyz. Significant minority

groups include Russians (18%), Uzbeks (12.9 per-

cent), Ukrainians (2.5%), and Germans (2.4%). The

capital city of Bishkek has an estimated popula-

tion of 824,900, although the number may be

closer to one million if illegal immigrants are con-

sidered.

Sunni Islam of the Hanafi School is the dom-

inant faith among the Kyrgyz. However, when Is-

lam was introduced to the people, many kept their

indigenous beliefs and customs. The force of Is-

lam was further weakened during the Soviet pe-

riod when active religious adherence was

discouraged. During the early twenty-first cen-

tury, the Kyrgyz government espouses strong

support for maintaining a secular state and any

sympathy for radical Islam has been marginalized.

Linguistically, Kyrgyz is a Turkic language that

is mutually intelligible with Kazakh. Throughout

the past several centuries, it has been written in the

Arabic, Latin, and Cyrillic scripts, with the latter

two dominant during the Soviet period. The gov-

ernment is shifting the language back to the Latin

script, with an effort to emulate the Turkish model.

The early history of the Kyrgyz is shrouded in

mythology, particularly the founding legend of the

Manas, an epic poem of more than one million lines

that is still presented orally, through song. Kyrgyz

have had, in the past, their own forms of govern-

ment, although more often they have been under

the rule of outside forces: Mongol, Chinese,

Timurid, and Russian, to name the most signifi-

cant. During the period of the Russian Empire, the

Kyrgyz were often called Kara-Kyrgyz. There is a

common history with the Kazakhs, who were con-

fusingly called the Kyrgyz by Russian ethnogra-

phers for most of the nineteenth century. Although

they were incorporated into the Khanate of Kokand

in the eighteenth century, the Kyrgyz were not al-

ways content with being controlled by others. Kyr-

gyz clans rebelled four times between 1845 and

1873. When the Khanate of Kokand was incorpo-

rated into the Russian province of Semirech’e in

1876, the same ire was directed against the new

overlords.

Through the rest of the nineteenth century and

into the early twentieth century, the region of the

Kyrgyz was firmly entrenched in the Russian Em-

pire. In 1916, there was a large-scale uprising in

the region against the threat of drafting ethnic Kyr-

gyz and other Central Asians into the Russian

Army, to support the effort against Germany and

Austria-Hungary. The regional turmoil only deep-

ened with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the

subsequent civil war, both of which had direct ef-

fects on the Kyrgyz people. Significant fighting

took place on Kyrgyz soil, and the anti-Bolshevik

Basmachi Rebellion was partially based in the re-

gions of southern Kyrgyzstan, around the city of

Osh. By the early 1920s the region was pacified,

but at a high cost: Perhaps a third of all residents

of the region either died in the fighting and in the

famine that plagued Central Asia in those years, or

fled to China.

In the National Delimitation of 1924, the ter-

ritory of the Kyrgyz was incorporated in the

Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic and was dubbed

an Autonomous Republic. The region was elevated

to full Union-Republic status in 1936 and was of-

ficially called the Kirgiz Soviet Socialist Republic

(Kir.S.S.R.). This entity lasted until 1991, when the

KYRGYZSTAN AND KYRGYZ

807

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet Union was officially dissolved. At the time

of independence, the name was changed to the Re-

public of Kyrgyzstan, and later the Kyrgyz Re-

public. With independence, the former president of

the Kirgiz Soviet Socialist Republic, Askar Akayev,

was elected president of the new country. He con-

tinued to hold that position in 2003, and has con-

solidated his authority over the years. The Kyrgyz

Republic has the institutions associated with a

democracy—a legislature, a judiciary, a president,

and a constitution—but the conditions for demo-

cratic development remain weak.

Economically, the Kyrgyz have traditionally

been nomadic herders, and pastoral activity re-

mains important for the Kyrgyz. With more than

80 percent of the territory being mountainous, pas-

toral habits include bringing the herds to high-

elevation fields during the summer and back to the

valleys during the winter months. There are also

mineral deposits in the country, particularly of

gold and some strategic minerals that can be ex-

ploited. Overall, the economy remains poor, with

a gross national product (GDP) of approximately

$13.5 billion dollars. While the purchasing power

parity (PPP) of the country is $2,800 per capita,

typical incomes often fall to less than $100 per

month per person.

Making matters worse is the fact that the coun-

try has borrowed heavily from the international

community during the first decade of independence.

The national budget is actually exceeded by the

amount owed to organizations such as the World

Bank and the International Monetary Fund, totaling

more than $1.6 billion as of 2003. In addition, cor-

ruption is rampant and most international com-

panies and observers view the business conditions

in the country in a negative light. These problems

will continue to plague any effort at economic re-

form that the current government, or its successor,

might try to implement.

While there are ethnic Kyrgyz in neighboring

Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and China, the

respective populations are relatively modest and do

not cause much concern. Regardless, the Kyrgyz feel

it necessary to establish positive relations with these

neighboring states, in large part because of the dif-

ficult borders and the fact that the Kyrgyz Republic

KYRGYZSTAN AND KYRGYZ

808

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Z

E

R

A

V

S

H

A

N

R

A

N

G

E

A

L

A

Y

S

K

I

Y

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

K

Y

R

G

Y

Z

S

K

I

Y

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

T

I

A

N

S

H

A

N

Jengish

Chokusu

24,406 ft.

7439 m.

Pik Lenina

23,406 ft.

7134 m.

Turugart

Pass

K

Ö

K

S

H

A

L

T

A

U

Issy-Kul'

(Ysyk-Köl)

Ozero

Song-Kël'

Ozero

Chatyr-Kël'

K

a

r

a

A

k

s

a

y

N

ary

n

S

h

u

T

a

l

a

s

K

y

z

y

l

C

h

i

r

c

h

i

k

Toxkan

Vakhsh

Ozero

Karakul'

¯

Kara-Balta

Jalal-Abad

Tash Kömür

Tokmak

Przheval'sk

Kara-Say

Sülüktü

Talas

Namangan

Daraut Kurgan

Angren

Kok Yangak

Toktogul

Kyzyl-Kyya

Gul'cha

Naryn

Cholpon-Ata

Issy-Kul'

(Ysyk-Köl)

Kadzhi

Say

Tyul'kubas

Bishkek

Alma-Ata

Tashkent

Osh

KAZAKHSTAN

TAJIKISTAN

UZBEKISTAN

CHINA

W

S

N

E

Kyrgyzstan

KYRGYZSTAN

150 Miles

0

0

150 Kilometers

50 100

50 100

Kyrgyzstan, 1992. © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

is a relatively small neighbor in this region. Thus, it

is not surprising to see the Kyrgyz government par-

ticipate in a number of multilateral security and trade

agreements. It is an active member of the Common-

wealth of Independent States, the Shanghai Cooper-

ation Organization (which includes China, Russia,

Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan), the Collec-

tive Security Agreement (with six CIS states), as well

as a number of regional initiatives. It is also a mem-

ber of the NATO Partnership for Peace Program and,

as a result of the U.S.-led Global War on Terrorism,

agreed to have NATO forces establish a military air-

base outside of the capital city Bishkek in 2001. Dur-

ing 2002, the Kyrgyz government allowed the

Russian Air Force to base jets at a second airbase, and

in 2003 the army of Kyrgyzstan conducted military

exercises with the People’s Liberation Army of China.

Foreign relations ultimately are less of a con-

cern than the day-to-day domestic problems that

plague the country. Economic development, em-

ployment difficulties, crime, corruption, and social

problems continue to exist in the Kyrgyz Republic.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZA-

KHS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST; POLOVTSY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Achylova, Rakhat. (1995). “Political Culture and Foreign

Policy in Kyrgyzstan.” In Political Culture and Civil

Society in Russia and the New States of Eurasia, ed.

Vladimir Tismaneanu. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Allworth, Edward, ed. (1994). Central Asia: 130 Years of

Russia Dominance, A Historical Overview. Durham,

NC: Duke University Press.

Anderson, John. (1999). Kyrgyzstan: Central Asia’s Island

of Democracy. New York: Harwood Academic Pub-

lishers.

Bennigsen, Alexandre and Wimbush, S. Enders. (1985).

Muslims of the Soviet Empire: A Guide. London: C.

Hurst.

Cummings, Sally, ed. (2002). Power and Change in Cen-

tral Asia. London: Routledge.

Huskey, Eugene. (1997). “Kyrgyzstan: The Fate of Polit-

ical Liberalization.” In Conflict, Cleavage, and Change

in Central Asia and the Caucasus, ed. Karen Dawisha

and Bruce Parrott. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Stewart, Rowan and Weldon, Susie. (2002). Kyrgyzstan:

An Illustrated Guide. New York: Odyssey Publica-

tions.

R

OGER

K

ANGAS

KYRGYZSTAN AND KYRGYZ

809

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

This page intentionally left blank

LABOR

Labor commonly refers to the work people do in

the employ of others. In its history, labor in Rus-

sia has taken a wide variety of forms, from slav-

ery to labor freely exchanged for wages, and the

full gamut of possibilities between those extremes.

The fates of both peasants and workers have been

tightly bound together through most of Russian

history.

FROM KIEV THROUGH PETER I

While slavery was common through the reign of

Peter I, perhaps accounting for 10 percent of the

population around 1600, it was never the domi-

nant factor in the economy. In Kievan Rus, labor

was generally free in both the vibrant cities and

the countryside. Although information is scarce,

manufacturing throughout the Kievan and Mus-

covite periods seems to have been generally on a

small-scale, artisanal basis; for a variety of rea-

sons a European-style guild system never devel-

oped. The free-hire basis of labor only began to

become seriously restricted with the centralization

of the Muscovite state. The slow but steady im-

position of serfdom on peasants was matched by

a similar reduction in the urban population’s mo-

bility. Both peasants and city dwellers were per-

manently tied to their locations by the Law Code

of 1649. Constraints on movement became even

more severe when Peter I instituted the poll tax as

a communal obligation, firmly binding all non-

nobles to their communal organization, whether

rural or urban.

Before 1700, urban manufacture was artisanal,

carried out in very small enterprises, which makes

it difficult to speak of an urban working class.

Large-scale manufacturing began in the country-

side, close to natural resources, either on noble-

owned land, with nobles utilizing their own

peasants, or on land granted by the government

for specifically industrial purposes. In the latter

case, although labor was hired at times, the work

force was more usually peasants who had been as-

signed either temporarily or permanently to that

particular enterprise. The binding of the entire pop-

ulation to specific locations after 1649 made freely

hirable labor difficult to find. This problem was

exacerbated after Peter the Great began large-scale

industrialization, most notably in the Urals metal-

lurgical complex.

L

811

FROM PETER TO THE GREAT REFORMS

During the course of the 1700s, however, the role

of hired labor became more important, as the in-

creasing importance of money in the economy

made industrial labor an attractive option for both

cash-starved serf owners and peasant households.

This was true especially in northern Russia, where

the soil was less fertile, the growing season shorter,

and agriculture less viable. These regions would

also experience a new kind of industrial growth, as

peasant entrepreneurs, under the protection of fi-

nancially interested owners, slowly exploited local

craft traditions and began to build industries using

hired labor. The two Sheremetev-owned villages of

Ivanovo and Pavlovo are examples of this trend,

becoming major textile and metalworking centers,

respectively.

The first decades of the nineteenth century wit-

nessed an increased acceleration in the factory and

mining workforce, from 224,882 in 1804 to

860,000 in 1860. Although less than 10 percent of

workers in 1770 were hired as opposed to assigned,

by 1860 well over half were hired. Not all of this

labor was free, however, since it included hiring

contracts forced upon peasants by serf owners or

even village communes. In addition, hired labor was

concentrated in the greatest growth industry of the

period, textiles, especially in the central provinces

of Moscow and Vladimir. Forced labor still com-

prised the great majority of the metallurgical and

mining work forces on the eve of the Great Re-

forms.

PEASANT OR PROLETARIAN?

Although peasants remained tied to their commune

as a result of the emancipation of the serfs, this

hindered the labor market as little as serfdom had.

By 1900, 1.9 million Russians worked in factories

and mines; by 1917, 3.6 million did so. In addi-

tion, the total number of those earning any kind

of wage, either full or part time, increased from 4

million to 20 million between 1860 and 1917. The

bulk of this increase in the factory and mining

work force came from the peasantry. For a cen-

tury, historians have debated whether the Russian

industrial worker was more a peasant or a prole-

tarian, an argument rendered more acute by the

coming to power in 1917 of a regime claiming to

rule in the name of the proletariat. This argument

has never been satisfactorily resolved. Most indus-

trial peasants remained juridical peasants, with fi-

nancial obligations to the village commune. More

than that, they usually identified themselves as

peasants. A few historians have claimed that with

an unceasing influx of peasants into the work force,

the Russian working class was simply the part of

the peasantry who worked in factories, and some see

the Bolshevik Revolution as the successful manipu-

lation by intellectuals of naïve peasant-workers.

Others, on the other hand, have carefully traced the

development of a hereditary work force, as the chil-

dren of migrants themselves went to work in the

factories, lost their ties to the countryside, and

came to identify themselves not as peasants, but as

workers. The archetype of this is the iconic St. Pe-

tersburg skilled metalworker, a second or third-

generation worker, literate, born and raised in the

city, with a sophisticated understanding of politi-

cal matters and consciously supporting a socialist

path in the recasting of Russian society. The truth

is certainly somewhere between these poles, but

there is no consensus on where. Certainly through

the 1930s most of the industrial workforce con-

sisted of first-generation workers. However, on the

eve of the revolution, possibly a third of workers

were hereditary.

What it meant to be a hereditary worker is not

clear. Many workers grew up in the countryside,

worked in a factory for several years, then returned

to the village to take over the family plot. Their

children grew up in the village, might themselves

die in the village, would work in factories for a

decade or so, and could thus be considered both

peasants and hereditary workers. In addition, well

over half of Russia’s factory workers labored in

mills located in the countryside. Thus, although

they worked in a factory, they were still in and of

the village.

LABOR IN REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA

Regardless of whether they were peasant or prole-

tarian, there was a continually increasing quantity

of factory workers, who constituted growing pro-

portions of the two rapidly expanding capitals, St.

Petersburg and Moscow, where workers would

play a political role beyond their numerical weight

in the general population. Throughout the imper-

ial period, working conditions were horrible, with

seventy-hour work-weeks and little concern for

worker health.

Although strikes remained illegal through most

of the imperial period, they are recorded as early

as the 1600s. However, the size of the industrial

sector was not large enough to produce strikes of

major concern to the state until the 1880s, with

larger strike waves occurring in the mid-1890s and

LABOR

812

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY