Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

alarmed by the threats to Soviet unity posed by the

non-Russian republics. In August 1991, Kryuchkov

and his hard-line colleagues in the government de-

clared a state of emergency in the country, hoping

that Gorbachev, who was vacationing in the Crimea,

would support them. When Gorbachev refused,

they backed down and were arrested. Kryuchkov

was released from prison in 1993 and in 1996 pub-

lished his memoirs, A Personal File (Lichnoye delo),

where he defended his attempt to keep the Soviet

Union together and accused Gorbachev of weakness

and duplicity.

See also: ANDROPOV, YURI VLADIMIROVICH; AUGUST

1991 PUTSCH; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEEVICH; IN-

TELLIGENCE SERVICES; STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Knight, Amy. (1988). The KGB: Police and Politics in the

Soviet Union. Boston: Allen and Unwin.

Knight, Amy. (1996). Spies Without Cloaks: The KGB’s Suc-

cessors. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

A

MY

K

NIGHT

KUCHUK KAINARJI, TREATY OF

The first war between Russia and Turkey during the

reign of Catherine the Great began in 1768. After

the Russians won a series of victories and advanced

beyond the Danube River deep into Ottoman terri-

tory in the Balkans, Field Marshal Peter Rumyant-

sev and Turkish plenipotentiaries met in an obscure

Bulgarian village and signed a peace treaty on July

10, 1774. The war was a major victory for Cather-

ine’s expansionist policy and a realization of the

goals of Peter the Great in the south. The Russian

Empire gained permanent control of all the fortress-

ports on the Sea of Azov and around the Dneiper-

Bug estuary, the right of free navigation on the Black

Sea, including the right to maintain a fleet, and the

right of passage through the Bosphorus and the Dar-

danelles for merchant vessels. The Tatar khanate of

the Crimean Peninsula was recognized as indepen-

dent, thus removing the Ottoman presence from the

northern shore of the Black Sea and essentially

bringing the area under Russia control (it was peace-

fully annexed in 1783), and the Turks paid an in-

demnity of 4.5 million rubles, which covered much

of the Russian costs of the war.

The treaty also gave Russia the right to main-

tain consulates throughout the Ottoman Empire and

to represent the interests of the Orthodox Church in

the Holy Land. Because Russia no longer needed an

alliance with an independent Zaporozhian Cossack

host, this military and diplomatic success led to its

destruction and the end of any notion of an au-

tonomous Ukraine for more than a hundred years.

The treaty symbolized the consolidation of Russian

control of the southern steppe, the rise of Russia as

a great European and Middle Eastern power, and the

beginning of the end of Turkish supremacy in the

area. No wonder there were great celebrations in

Moscow a year later, during which the foremost

Russian military heroes were lavishly rewarded and

Rumyantsev was given the honorific Zadunyasky

(“beyond the Danube”). More than any other event,

the treaty established Catherine II as “the Great” in

terms of Russian expansion. The Ottoman loss,

however, left a vacuum in the eastern Mediterranean

open for the ambitions of Napoleon I twenty-five

years later, and many more battles in the eastern

Mediterranean would result. Perhaps the shattering

international impact of the treaty is the ghost be-

hind the Middle Eastern and Balkan problems of the

twentieth century and beyond.

See also: CATHERINE II; RUMYANTSEV, PETER ALEXAN-

DROVICH; RUSSO-TURKISH WARS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, John T. (1989). Catherine the Great: Life and

Legend. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Madariaga, Isabel de. (1981). Russia in the Age of Cather-

ine the Great. New Haven: Yale University Press.

N

ORMAN

S

AUL

KULAKS

The term kulak came into use after emancipa-

tion in 1861, describing peasants who profited from

their peers. While kulak connotes the power of the

fist, the nearly synonymous term miroyed means

“mir-eater.” At first the term “kulak” did not refer

to the newly prosperous peasants, but rather to vil-

lage extortioners who consume the commune, men

of special rapacity, their wealth derived from usury

or trading rather than from agriculture. The term

never acquired precise scientific or economic defin-

ition. Peasants had a different understanding of the

kulaks than outsiders; however, both definitions

focused on social and moral aspects. During the

KULAKS

793

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

twentieth century Lenin and Stalin defined the ku-

laks in economic and political terms as the capital-

ist strata of a polarized peasantry. Exploitation was

the central element in the peasants’ definition of the

miroyed as well as in outsiders’ definition of the ku-

lak. Peasants, by contrast, attributed power to the

kulak and limited their condemnation to peasants

who exploited members of their own community.

The kulaks also played an important political role

in self-government of the peasant community. In

the communal gathering they controlled decision

making and had great influence on the opinion of

the rest of the peasants.

The meaning of the term changed after the Oc-

tober Revolution, as the prerevolutionary type of

kulak seldom survived in the village. In the 1920s

the kulaks were in most instances simply wealth-

ier peasants who, unlike their predecessors, were

incontestably devoted to agriculture. They often

were only slightly distinguishable from the middle

peasants. Thus many Bolshevik leaders denied the

existence of kulaks in the Soviet countryside. When

in the mid-1920s the question of differentiation of

the peasantry became part of the political debate,

the statisticians had to provide a picture based on

Lenin’s assumption of class division. As social dif-

ferentiation was still quite weak, it was impossible

to define a clear class of capitalist peasants. The use

of hired laborers and the leasing of land was un-

der control of the rural soviets. Traditional forms

of exploitation in the countryside, such as usury

and trading, had lost their significance due to the

growing cooperative organization of the peas-

antry. Since the use of hired laborers—a sign of

capitalist exploitation—made it difficult to find a

significant number of peasant capitalists for sta-

tistical purposes, a mixture of signs of wealth and

obscure indicators of exploitation came into use in

definition of the kulak: for example, ownership of

at least three draught animals, sown area of more

than eleven hectares, ownership of a trading es-

tablishment even without hired help, ownership of

a complex and costly agricultural machine or of a

considerable quantity of good quality implements,

and hiring out of means of production. In general,

the existence of one criterion was enough to de-

fine the peasant household as kulak. The statisti-

cians thus determined that 3.9 percent of the

peasantry consisted of kulaks.

It was exactly its indefiniteness that allowed

the Bolsheviks to use the term kulak to initiate class

war in the Soviet countryside toward the end of

the 1920s. In order to force the peasants into the

kolkhoz, the Politburo declared the almost nonex-

istent group of kulaks to be class enemies. Every

peasant who was unwilling to join the kolkhoz had

to fear being classified as kulak and subjected to ex-

propriation and deportation. The justification lay

in the political role the stronger peasants played in

the communal assemblies. Together with the bulk

of the peasants they were skeptical of any ideas of

collective farming. The sheer existence of success-

ful individual peasants ran counter to the Bolshe-

vik aim of collectivization.

Due to the political pressure of new regulations

for disenfranchisement in the 1927 election cam-

paign and expropriation by the introduction of an

excessive and prohibitive individual taxation in

1928, the number of kulaks started to decrease.

This process was called self-dekulakization, mean-

ing the selling of means of production, reducing

the rent of land, and the leasing of implements to

poorer farms. It was easy for the kulak to bring

himself socially and economically down to the sit-

uation of a middle peasant. He only had to sell his

agricultural machine, dismiss his batrak (hired la-

borer), or close his enterprise for there to be noth-

ing left of the kulak as defined by the law. Several

kulaks sought to escape the blows by flight to the

towns, to other villages, or even into the kolkhozy

if they were admitted.

On December 27, 1929, Stalin announced the

liquidation of the kulaks as a class, that is, their

expropriation and deportation. For the sake of the

general collectivization the kulaks were divided into

three different groups. The first category, the so-

called “counterrevolutionary kulak-activists, fight-

ing against collectivization” should be either

arrested or shot on the spot; their families were to

be deported. The second category, “the richest ku-

laks,” were to be deported together with their fam-

ilies into remote areas. The rest of the kulaks were

to be resettled locally. The Politburo not only

planned the deportation of kulaks, ordering be-

tween 3 to 5 percent of the peasant farms to be liq-

uidated and their means of production to be given

to the kolkhoz, but also fixed the exact number of

deportees and determined their destinations. The

kulaks were clearly needed as class enemies to drive

the collectivization process forward: After the liq-

uidation of the kulaks in early 1930, and during

the second major wave of collectivization in 1931,

the Politburo ordered a certain percentage of the

remaining peasant farms to be defined as kulaks

and liquidated. Even if a peasant was obviously not

wealthy, the term podkulak (walking alongside the

KULAKS

794

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

kulaks) enabled the worker brigades to expropriate

and arrest him.

Between 1930 and 1933, some 600,000 to

800,000 peasant households consisting of 3.5 to 5

million people, were declared to be kulaks, expro-

priated, and turned out of their houses. As local re-

settlement proved difficult, deportation hit more

families than originally planned. By the end of

1931, about 380,000 to 390,000 kulak households

consisting of about two million people were de-

ported and brought to special settlements in remote

areas, mostly in northern Russia or Siberia. Be-

tween 1933 and 1939, another 500,000 people

reached the special settlements, mostly deportees

from the North Caucasus during the famine of

1933. About one-fourth of the deportees did not

survive the transport or the first years in the spe-

cial settlements. After the new constitution of

1936, the term kulak fell out of use. At the begin-

ning of 1941, 930,000 people were still registered

in the special settlements. They were finally rein-

stated with their civilian rights during or shortly

after World War II.

See also: CLASS SYSTEM; COLLECTIVE FARM; COLLEC-

TIVIZATION OF AGRICULTURE; COOPERATIVE SOCI-

ETIES; EMANCIPATION ACT; PEASANTRY; STALIN,

JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frierson, Cathy Anne. (1992). From Narod to Kulak: Peas-

ant Images in Russia, 1870–1885. Ph.D. diss., Uni-

versity of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Lewin, Moshe. (1966/1967). “Who was the Soviet Ku-

lak?” Soviet Studies 18:189–212.

Merl, Stephan. (1990). “Socio-economic Differentiation

of the Peasantry.” In From Tsarism to the New Eco-

nomic Policy: Continuity and Change in the Economy of

the USSR, ed. Robert W. Davies. London: Macmillan

Press.

Viola, Lynne. (1996). Peasant Rebels under Stalin: Collec-

tivization and the Culture of Peasant Resistance. New

York: Oxford University Press.

S

TEPHAN

M

ERL

KULESHOV, LEV VLADIMIROVICH

(1899–1970), film director and theorist.

Along with Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pu-

dovkin, and Dziga Vertov, Lev Kuleshov revolu-

tionized the art of filmmaking in the 1920s. One

of the few Young Turks to have had significant

prerevolutionary experience in cinema, Kuleshov

was employed by the Khanzhonkov studio as an

art director in 1916 and worked with the great

Russian director Yevgeny Bauer until Bauer’s death

in 1917. Kuleshov’s first movie as a director was

Engineer Prite’s Project (1918). During the Russian

Civil War he organized newsreel production at the

front.

In 1919 he founded a filmmaking workshop in

Moscow that came to be known as the Kuleshov

collective. Because of the shortage of film stock dur-

ing the civil war, the collective shot “films without

film,” which is to say that they staged rehearsals.

Several important directors and actors emerged

from the collective, including Boris Barnet, Vsevolod

Pudovkin, Alexandra Khokhlova, Sergei Komarov,

and Vladimir Fogel.

Kuleshov also became known as the leading ex-

perimentalist and theorist among the Soviet

Union’s future cinema artists, and published his

ideas extensively. His most famous was known as

the “Kuleshov effect.” By juxtaposing different im-

ages with the same shot of the actor Ivan Moz-

zhukhin, Kuleshov demonstrated the relationship

between editing and the spectator’s perception. Al-

though there is some debate about the validity of

the experiment in the early twenty-first century,

at the time it was widely reported that viewers in-

sisted that Mozzhukhin’s expression changed ac-

cording to the montage. His published his film

theories in 1929 as The Art of the Cinema.

Kuleshov made a series of brilliant but highly

criticized movies in the 1920s, most important

among them The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr.

West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) and By the

Law (1926). Even before the Cultural Revolution

(1928–1931), Kuleshov had been attacked as a “for-

malist,” and his career as a director essentially

ended in 1933 with The Great Consoler. In 1939

Kuleshov joined the faculty of the All-Union State

Institute of Cinematography and taught directing

to a new generation of Soviet filmmakers.

See also: BAUER, YEVGENY FRANTSEVICH; CULTURAL REV-

OLUTION; EISENSTEIN, SERGEI MIKHAILOVICH; MO-

TION PICTURES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kuleshov, Lev.(1974). Kuleshov on Film: Writings. Berke-

ley: University of California Press.

KULESHOV, LEV VLADIMIROVICH

795

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Youngblood, Denise J. (1991). Soviet Cinema in the Silent

Era, 1918–1935. Austin: University of Texas Press.

D

ENISE

J. Y

OUNGBLOOD

KULIKOVO FIELD, BATTLE OF

On September 8, 1380, Rus forces led by Grand

Prince Dmitry Ivanovich fought and defeated a

mixed (including Tatar, Alan, Circassian, Genoese,

and Rus) army led by the Emir Mamai on Kulikovo

Pole (Snipe’s Field) at the Nepryadva River, a trib-

utary of the Don. As a result of the victory, Dmitry

received the sobriquet “Donskoy.” Estimates of

numbers who fought in the battle vary widely. Ac-

cording to Rus chronicles, between 150,000 and

400,000 fought on Dmitry’s side. One late chron-

icle places the number fighting on Mamai’s side at

900,030. Historians have tended to downgrade

these numbers, with estimates ranging from

30,000 to 240,000 for Dmitry and 200,000 to

300,000 for Mamai.

The circumstances of the battle involved poli-

tics within the Qipchaq Khanate. Mamai attempted

to oust Khan Tokhtamish, who had established

himself in Sarai in 1378. In order to raise revenue,

Mamai intended to require tribute payments from

the Rus princes. Dmitry organized the Rus princes

to resist Mamai and, in effect, to support Tokhtamish.

As part of his strategy, Mamai had attempted to

coordinate his forces with those of Jagailo, the

grand duke of Lithuania, but the battle occurred be-

fore the Lithuanian forces arrived. After fighting

most of the day, Mamai’s forces left the field, pre-

sumably because he was defeated, although some

historians think he intended to conserve his army

to confront Tokhtamish. Dmitry’s forces remained

at the scene of the battle for several days, and on

the way back to Rus were set upon by the Lithua-

nia forces under Jagailo, which, too late to join up

with Mamai’s army, nonetheless managed to wreak

havoc on the Rus troops.

Although the numbers involved in the battle

were immense, and although the battle led to the

weakening of Mamai’s army and its eventual de-

feat by Tokhtamish, the battle did not change the

vassal status of the Rus princes toward the Qipchaq

khan. A cycle of literary works, including Zadon-

shchinai (Battle beyond the Don) and Skazanie o Ma-

maevom poboishche (Tale of the Rout of Mamai),

devoted to ever-more elaborate embroidering of the

bravery of the Rus forces, has created a legendary

aura about the battle.

See also: DONSKOY, DMITRY IVANOVICH; GOLDEN HORDE;

KIEVAN RUS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Halperin, Charles J. (1986). The Tatar Yoke. Columbus,

OH: Slavica Publishers.

D

ONALD

O

STROWSKI

KULTURNOST

The term kulturnost (“culturedness”) originates

from the Russian kultura (culture) and can be trans-

lated as “cultured behavior,” “educatedness,” or

simply “culture.”

Kulturnost is a concept used to determine the

level of a person’s or a group’s education and cul-

ture, which can be purposefully transferred and in-

dividually adopted. It first appeared in the 1870s

when the narodniki (group of liberals and intellec-

tuals) tried to bring education and enlightenment

to the working and peasant masses. A “cultured

person” (kulturnyi chelovek) was one who mastered

culture.

The meanings of kulturnost can differ with

time, place, and context. It became a strategy of the

Soviet regime in the 1930s, when millions of peas-

ants poured into the cities and new construction

sites, and their nekulturnost (uncultured behavior)

seemed to endanger public order. Cultural policy

aimed to transform them into disciplined Soviet cit-

izens by propagandizing kulturnost, which in this

context demanded good manners, personal hygiene

(e.g. cleaning teeth), dressing properly, but also a

certain educational background, level of literacy,

and basic knowledge of communist ideology.

Kulturnost was thus part of a broader Soviet

civilizing mission addressing the Russian peasants,

but also native “backward” peoples. In the creation

of a new Soviet middle class, kulturnost centered

on individual consumption. Values and practices

that were formerly scorned as bourgeois could be

reestablished on the basis of kulturnost in the

1930s.

As an integration strategy used by the regime

and as a reference point for various parts of the

KULIKOVO FIELD, BATTLE OF

796

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

population, kulturnost gained significance in the

formation of Russian and Soviet identities.

See also: NATIONALITIES POLICY, SOVIET; PEASANTRY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1992). The Cultural Front. Power and

Culture in Revolutionary Russia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University Press.

Volkov, Vadim. (2000). “The Concept of Kul’turnost’.

Notes on the Stalinist Civilizing Process.” In Stalin-

ism. New Directions, ed. Sheila Fitzpatrick. London

and New York: Routledge.

J

ULIA

O

BERTREIS

KUNAYEV, DINMUKHAMMED

AKHMEDOVICH

(1912–1993), second ethnic Kazakh to lead the

Kazakh Communist Party, member of the Soviet

Politburo.

Born in Alma-Ata, Dinmukhammed Kunayev

became a mining engineer after graduating from

Moscow’s Kalinin Metals Institute in 1936. He

joined the Communist Party in 1939 and soon

became chief engineer, and then director, of the

Kounrad Mine of the Balkhash Copper-Smelting

Combine. Between 1941 and 1945 he was deputy

chief engineer and head of the technical section of

the Altaipolimetall Combine, director of the Ridder

Mine, and then director of the extensive Lenino-

gorsk Mining Administration. From 1942 to 1952

he also was deputy chairman of the Kazakh Coun-

cil of People’s Commissars. Having obtained a

candidate’s degree in technical sciences in 1948, he

became a full member of the Kazakh Academy of

Sciences in 1952 and served as its president until

1955 and as chairman of the Kazakh SSR’s Coun-

cil of Ministers from 1955 to 1960.

By now a regular delegate to both the Kazakh

and Soviet Party Congresses and Supreme Soviets,

Kunayev progressed within the Communist hierar-

chy as well. In 1949 he became a candidate, and in

1951 a full member, of the Kazakh Central Com-

mittee, and in 1956 a member of the Central Com-

mittee of the CPSU. A member of the Kazakh Party’s

Bureau, he first served as the powerful first secre-

tary from 1960 to 1962 and, after chairing the min-

isterial council from 1962 to 1964, served again as

first secretary from 1964 to 1986. In 1966 he also

became a candidate member of the Soviet Central

Committee’s Politburo, in 1971 he was promoted

to full membership, and he was twice named a Hero

of Socialist Labor (1972, 1976). Much of his suc-

cess was due to the patronage of the Soviet leader

Leonid Brezhnev, who himself earlier had been the

Kazakh Party’s first secretary. Critics charged that

Kunayev showered Brezhnev with gifts and cash,

but left politics to Party officials while he focused

on the interests of his large and corrupt Kazakh

clan. Even so, he did promote the concept of Kaza-

khstani citizenship and, in December 1986, his dis-

missal for corruption and replacement by the

Russian Gennady Kolbin sparked the Alma-Ata ri-

ots. Despite Kunayev’s ejection from the Politburo

in January 1987, in 1989 his supporters secured

his election to the Kazakh parliament, and he re-

mained a deputy until he died near Alma-Ata in

1993. In late 1992 his clan and former Kazakh

officials honored him by establishing a Kunayev In-

ternational Fund in Alma-Ata. It had the proclaimed

goals of strengthening the Kazakh Republic’s sov-

ereignty, improving its living standards, and reviv-

ing the Kazakh cultural heritage.

See also: CENTRAL COMMITTEE; COMMUNIST PARTY OF

THE SOVIET UNION; KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Olcott, Martha Brill. (1995). The Kazakhs, 2nd ed. Stan-

ford, CA: Hoover Institution.

D

AVID

R. J

ONES

KURBSKY, ANDREI MIKHAILOVICH

(1528–1583), prince, boyar, military commander,

emigré, writer, and translator.

A scion of Yaroslav’s ruling line, Kurbsky be-

gan his career at Ivan IV’s court in 1547. From

1550 on, Kurbsky participated in military cam-

paigns, including the capture of Kazan (1552). In

1550 he was listed among the thousand elite mil-

itary servitors in Muscovy. In 1556 Kurbsky re-

ceived the highest court rank, that of boyar. During

the Livonian war, Kurbsky became a high-ranking

commander (1560). In 1564 Kurbsky fled to Sigis-

mund II Augustus, ruler of Poland and Lithuania,

fearing persecution in Muscovy. Kurbsky’s defec-

KURBSKY, ANDREI MIKHAILOVICH

797

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tion resulted in the confiscation of his lands and

the repression of his relatives in Muscovy.

Receiving large estates from Sigismund II, Kurb-

sky served his new lord in a military capacity, even

taking part in campaigns against Muscovy (1564,

1579, 1581). Kurbsky tried to integrate himself

into Lithuanian society through two marriages to

local women and participation in the work of lo-

cal elective bodies. At the same time, he was in-

volved in numerous legal and armed conflicts with

his neighbors.

A number of literary works and translations

are credited to Kurbsky. Among them are three let-

ters to Ivan IV, in which Kurbsky justified his flight

and accused the tsar of tyranny and moral cor-

ruption. His “History of the Grand Prince of

Moscow” glorifies Kurbsky’s military activities and

condemns the terror of Ivan IV. Kurbsky is some-

times seen as the first Russian dissident, though in

fact he never questioned the political foundations

of Muscovite autocracy. Continuing study of Kurb-

sky’s works has overturned traditional descriptions

of him as a conservative representative of the Mus-

covite aristocracy. Together with his associates,

Kurbsky compiled and translated in exile works

from various Christian and classical authors. Kurb-

sky’s literary activities in the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth are a striking example of contacts

between Renaissance and Eastern Orthodox cul-

tures in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Kurbsky’s interest in theological and classical writ-

ings, however, did not make him part of Renais-

sance culture or alter his Muscovite cultural stance.

Edward L. Keenan argues that the texts attrib-

uted to Kurbsky were in fact produced in the sev-

enteenth century and that Kurbsky was functionally

illiterate in Slavonic. Keenan’s hypothesis is based on

the dating and distribution of the surviving manu-

scripts, on textual similarities between works cred-

ited to Kurbsky and those by other authors of later

origin, and on his idea that members of the six-

teenth-century secular elite, including Kurbsky, re-

mained outside the tradition of church Slavonic

religious writing. Most experts reject Keenan’s ideas.

His opponents offer an alternative textual analysis

and detect circumstantial references to Kurbsky’s

letters to Ivan IV in sixteenth-century sources.

Scholars have discovered an earlier manuscript of

Kurbsky’s first letter to Ivan IV and have provided

considerable information on Kurbsky’s life in exile,

on his political importance as an opponent of Ivan

IV, and on the cultural interaction between the

church and secular elites in Muscovy. Though Kurb-

sky claimed he could not write Cyrillic, this state-

ment is open to different interpretations. Other Mus-

covites, whose ability to write is well documented,

also made similar declarations. Kurbsky’s major

works were translated into English by J. L. I. Fen-

nell: The Correspondence between Prince Kurbsky and

Tsar Ivan IV of Russia (1955); Prince A. M. Kurbsky’s

History of Ivan IV (1963).

See also: IVAN IV; LIVONIAN WAR; YAROSLAV VLADIMIRO-

VICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Auerbach, Inge. (1997). “Identity in Exile: Andrei Mikhailo-

vich Kurbskii and National Consciousness in the Six-

teenth Century.” In Culture and Identity in Muscovy,

1359–1584 / Moskovskaya Rus (1359–1584): Kultura

i istoricheskoe soznanie (UCLA Slavic Studies. New Se-

ries, vol. 3), ed. Ann M. Kleimola and Gail L. Lenhoff.

Moscow: ITZ-Garant.

Filyushkin, A. I. (1999). “Andrey Mikhaylovich Kurb-

sky.” Voprosy istorii 1:82–96.

Halperin, Charles J. (1998). “Edward Keenan and the

Kurbskii-Groznyi Correspondence in Hindsight.”

Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 46:376–403.

Keenan, Edward L. (1971). The Kurbskii-Groznyi Apoc-

rypha: The Seventeenth-Century Genesis of the “Corre-

spondence” Attributed to Prince A. M. Kurbskii and Tsar

Ivan IV, with an appendix by Daniel C. Waugh. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

S

ERGEI

B

OGATYREV

KURDS

The Kurds (or kurmandzh, as they call themselves)

are a people of Indo-European origin who claim as

their homeland (Kurdistan) the region encompass-

ing the intersection of the borders of Turkey, Iran,

Iraq, and Syria. The name “Kurd” has been offi-

cially used only in the Soviet Union; the Turks call

them Turkish Highlanders, while Iranians call them

Persian Highlanders. Although the Kurdish dias-

pora throughout the world numbers 30 to 40 mil-

lion, most Kurds live in the mountains and uplands

of the above mentioned countries and number be-

tween 10 and 12 million.

The Kurds have never had their own sovereign

country, but for a short period in the early 1920s

a Kurdish autonomous region existed in Azerbai-

jan. Although most Kurds live in Turkey, Iran, Iraq,

KURDS

798

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and Syria, two types of Kurdish peoples lived in the

Soviet Union before its collapse: the Balkano-Cau-

casian Caspian type of the European race akin to

the Azerbaijanis, Tats, and Talysh (living in Tran-

scaucasia), and the Central-Asian Kurds such as the

Baluchis (living in Tajikistan). Most Muslims of the

former Soviet Union resided in Central Asia, but

some also lived on the USSR’s western borders, as

well as in Siberia and near the Chinese border. Eth-

nically Soviet Muslims included Turkic, Caucasian,

and Iranian people. The Kurds, along with the Tats,

Talysh, and Baluchis, are Iranian people. In Tran-

scaucasia the Kurds live in enclaves among the main

population: in Azerbaijan (in Lyaki, Kelbadjar, Ku-

batly, and Zangelan); in Armenia (in Aparan, Talin,

and Echmiadzin); and in Georgia (scattered in the

eastern parts). In Central Asia they lived in Kaza-

khstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan (along the

Iranian border, as well as in Ashkhabad).

The Kurds of Caucasia and Central Asia were

isolated for so long from their brethren in the Mid-

dle East that their development in the Soviet Union

has diverged enough that some consider the Soviet

Kurds to be a separate ethnic group. Kurdish is an

Indo-European language belonging to the North-

western Iranian branch and is divided into several

dialects. The Kurds of Caucasia and Central Asia

speak the kurmandzh dialect. Younger generations

of Soviet Kurds in larger cities grew up bilingual,

speaking Russian as well. In the main, the Kurds

are followers of Islam. The Armenian Kurds are

Sunnites, while the Central Asian and Azerbaijani

Kurds are Shiite.

In the Russian Federation in the twenty-first

century, Kurds are frequently the targets of ethnic

violence. Skinheads, incited by Eduard Limonov (a

right-wing author and journalist) and Alexander

Barkashov (former head of the Russian National

Unity Party who openly espouses Nazi beliefs) have

assaulted Kurds, Yezids, Meskheti Turks, and other

non-Russians, particularly those from the Cauca-

sus. Racism has prevailed even among Russian of-

ficials, who have stated that non-Russian ethnic

groups such as the Kurds can only be guests in the

Krasnodar territory (in the Russian southwest), but

not for long.

KURDS

799

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

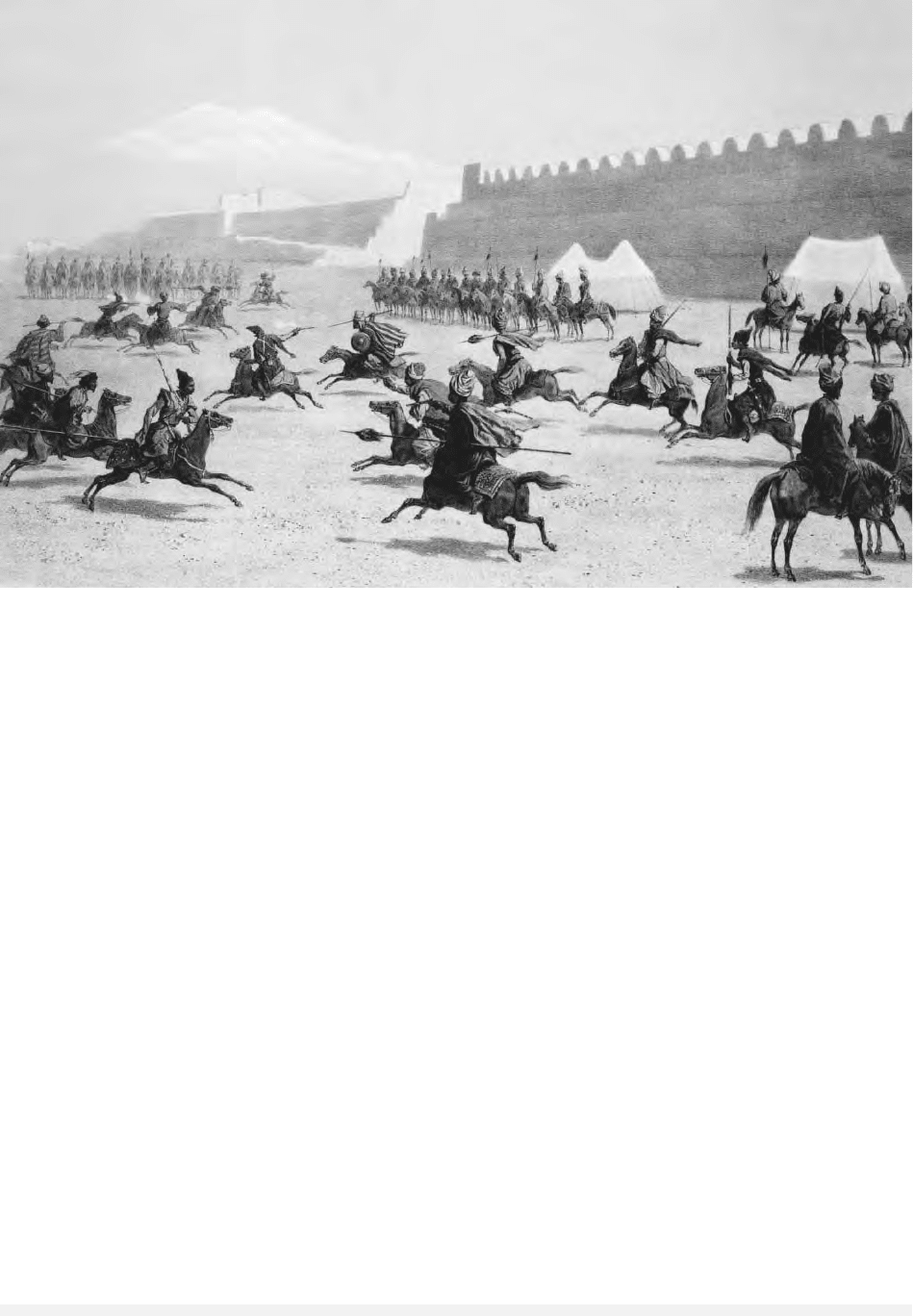

Lithograph depicting Kurds fighting Tatars, c. 1849. © H

ISTORICAL

P

ICTURE

A

RCHIVE

/CORBIS

See also: CAUCASUS; CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bulloch, John, and Harvey Morris. (1992). No Friends but

the Mountains: The Tragic History of the Kurds. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Chaliand, Gerard. (1993). A People without a Country: The

Kurds and Kurdistan. New York: Olive Branch Press.

Izady, Mehrdad R. (1992). The Kurds: A Concise Handbook.

Washington DC: Crane Russak.

Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary

Overview. London: Routledge.

Randal, Jonathan C. (1997). After Such Knowledge, What

Forgiveness? My Encounters with Kurdistan. New

York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

KURIL ISLANDS

The Kurils form an archipelago of more than thirty

mountainous islands situated in a curving line run-

ning north from Japanese Hokkaido to Russia’s

Kamchatka peninsula, enclosing the Sea of Okhotsk

and occupying an area of 15,600 square kilome-

ters. The Kurils have numerous lakes and rivers,

with a harsh monsoon climate, and are highly seis-

mic, with some thirty-five active volcanoes. Rus-

sians in search of furs first moved into the islands

from Kamchatka early in the eighteenth century,

thus coming into contact with the native Ainu and

eventually with the Japanese, who were expand-

ing northward. The 1855 Treaty of Shimoda di-

vided the islands; those north of Iturup were ceded

to Russia, while Japan controlled the four south-

ern islands. In the 1875 Treaty of St. Petersburg,

Japan ceded Sakhalin to Russia in exchange for the

eighteen central and northern islands; the 1905

Treaty of Portsmouth granted Japan sovereignty

over southern Sakhalin and all neighboring islands.

The USSR reoccupied the Kurils after World War II,

and in 1948 expelled 17,000 Japanese inhabitants.

Since then the southern four islands (Kunashiri,

Shikotan, Iturup, and the Habomais group) have

been disputed territory.

The Kuril islands are administered by Russian

Sakhalin. Never large, the population declined to

about 16,000 following a major earthquake in

1994. Some 3,500 border troops, far fewer than in

Soviet times, remain to guard the territory. Dur-

ing the Soviet period the islands were considered a

vital garrison outpost. The military valued the is-

land chain’s role in protecting the Sea of Okhotsk,

where Soviet strategic submarines were located.

The major industries are fish processing, fishing,

and crabbing, much of which is illegal. Once pam-

pered and highly paid by the Soviet government,

the Kuril islanders were neglected by Moscow af-

ter the collapse of the Soviet Union. Of necessity,

the inhabitants are developing closer ties with

northern Japan.

See also: JAPAN, RELATIONS WITH; RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cobb, Charles E., Jr. (1996). “Storm Watch Over the

Kurils.” National Geographic 190(4):48–67.

Stephan, John J. (1974). The Kuril Islands: Russo-Japan-

ese Frontier in the Pacific. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

C

HARLES

E. Z

IEGLER

KURITSYN, FYODOR VASILEVICH

(died c. 1502), state secretary (diak) and accused

heretic under Ivan III.

From an unknown family, but recognized for

his linguistic, literary, and administrative talents,

Fyodor Vasilevich Kuritsyn was one of Ivan III’s

chief diplomats in the 1480s and 1490s. Kuritsyn’s

most important mission was to Matthias Corvinas

of Hungary and Stefan the Great of Moldavia from

1482 to 1484 to arrange an alliance against Poland-

Lithuania. Kuritsyn then became one of the sover-

eign’s top privy advisors and handled several affairs

with Crimea and European states, including secret

matters. Fixer of the first official Russian document

with the two-headed eagle, Kuritsyn was also in-

volved in Muscovy’s initial land cadastres. The dis-

appearance of his name from the written sources

after 1500 may have been connected with the fall

of Ivan III’s half-Moldavian grandson and crowned

co-ruler Dmitry.

The traces of Kuritsyn’s intellectual life are in-

triguing. According to testimony obtained from a

Novgorod priest’s son under torture, Kuritsyn

returned from Hungary and formed a circle of

clerics and scribes that “studied anti-Orthodox

material.” Other “heretics” found refuge at his

home, so Archbishop Gennady concluded that Ku-

KURIL ISLANDS

800

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ritsyn was the “protector . . . and . . . leader of

all those scoundrels.” According to Joseph of

Volotsk’s exaggerated Account, the Novgorodian

heresiarch-archpriest Alexei and Kuritsyn “stud-

ied astronomy, lots of literature, astrology, sor-

cery, and secret knowledge, and therefore many

people inclined toward them and were mired in

the depths of apostasy.” Kuritsyn’s milieu proba-

bly did have access to some philosophical and as-

tronomical treatises.

The only work with Kuritsyn’s name as con-

veyor or translator-copyist is a brief poem with an

attached table of letters and coded alphabet, shar-

ing the deceptive, New Testament-Apocryphal ti-

tle, “Laodician Epistle.” The poem is of the chain

type, on the theme of the sovereign soul enclosed

in faith, linking wisdom, knowledge, the prophets,

fear of God, and virtue. The table gives phonetic

and, where appropriate, grammatical characteris-

tics of the letter symbols in their dual function as

letters and numbers. It uses both Greek and Slavic

terms—the latter having the metaphorical symme-

try of vowel-soul and consonant-body—and may

contain some hidden meanings or utility for div-

ination. An anonymous explanatory introduction

is close to the likewise anonymous “Outline of

Grammar,” both possibly by Kuritsyn. They pro-

mote the sovereignty of the literate mind and treat

letters as God’s redemptive gift to humanity and

the source of wisdom, science, memory, and pre-

dictive powers. Not strictly heretical, but akin to

Jewish wisdom literature, these works sat on the

humanist fringe of the acceptable in Muscovy.

Kuritsyn also may have composed, redacted, or

simply conveyed from Moldavia the underlying

text of the Slavic “Tale of Dracula.” This string of

semi-folklorish anecdotes about the “evil genius”

Wallachian voevoda Vlad the Impaler recounts the

just and unjust beastly reprisals of this self-styled

“great sovereign” without moral commentary—

except in the description of his purported apostasy

to Catholicism. Implicitly “Dracula” teaches that

despots must be humored and envoys trained and

smart.

Kuritsyn probably died around 1501. In 1502

or 1503 Ivan III reportedly knew “which heresy

Fyodor Kuritsyn held,” and in 1504 allowed Fyo-

dor’s brother, the diplomat-jurist state secretary

Ivan Volk, to be burned as a heretic or apostate.

Fyodor’s son Afanasy was also a state secretary.

See also: IVAN III; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Taube, Moshe. (1995). “The ‘Poem on the Soul’ in the

Laodicean Epistle and the Literature of the Judaizers.”

Harvard Ukrainian Studies 19:671–685.

D

AVID

M. G

OLDFRANK

KUROPATKIN, ALEXEI NIKOLAYEVICH

(1848–1925), adjutant general, minister of war,

commander during the Russo-Japanese War, colo-

nial administrator, and author.

Born in Sheshurino, Pskov Province, in 1848 to

a retired officer with liberal inclinations, Alexei

Kuropatkin received a superb military education,

graduating from the Paul Junker Academy in 1866

and the Nicholas Academy of the General Staff in

1874. Much of Kuropatkin’s career was linked to

the empire’s eastern frontier. Beginning as an in-

fantry subaltern in Central Asia, he saw active duty

during the conquest of Turkestan (1866–1871,

1875–1877, 1879–1883) and the Russo-Turkish

War (1877–1878). Kuropatkin’s close association

with the flamboyant White General Mikhail Dim-

itriyevich Skobelev, earned him a misleading repu-

tation as a decisive commander in combat (a

deception Kuropatkin actively promoted by writing

popular campaign histories). Kuropatkin was best

suited for administration and intelligence, and he

enjoyed a rapid rise in the military bureaucracy, in-

cluding posts in the army’s Main Staff (1878–1879,

1883–1890), head of the Trans-Caspian Oblast

(1890–1898), and minister of war (1898–1904).

Kuropatkin assumed command of the ministry

in a climate of strategic vulnerability, as growing

German military power combined with a weaken-

ing economy. Accordingly, his top priority was to

strengthen the empire’s western defenses against

the Central Powers. However, Nicholas II’s adven-

tures on the Pacific drew him back to the East, al-

beit reluctantly. Well aware of the threat posed by

Japan’s modern armed forces, Kuropatkin opposed

the Russian emperor’s increasingly aggressive

course in Manchuria. Nevertheless, he loyally re-

signed his post as minister to command Russia’s

land forces in East Asia when Japan attacked in

1904. Insecurity and indecision hobbled his per-

formance in the field. Reluctant to risk his troops

in a decisive contest, Kuropatkin chose instead to

order retreats whenever the outcome of a clash

seemed in doubt. As a result, while he never lost a

KUROPATKIN, ALEXEI NIKOLAYEVICH

801

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

major battle, his repeated pullbacks fatally corroded

Russian morale, and constituted one of the leading

reasons for tsarist defeat in 1905.

After the war, Kuropatkin published prolifi-

cally in an effort to restore his tarnished reputa-

tion. During World War I, he returned to the colors

on the northwestern front in 1915, but his leader-

ship proved to be equally undistinguished. In July

1916 Nicholas II reassigned him as Turkestan’s

governor-general, where he suppressed a major na-

tionalist rebellion later that year. Although he was

relieved of his post and even briefly arrested by the

Provisional Government in early 1917, Kuropatkin

avoided the postrevolutionary fate of many other

prominent servants of the autocracy. He spent his

remaining years as a schoolteacher in his native

Sheshurino until his death of natural causes on

January 26, 1925. Kuropatkin does not figure

prominently in the pantheon of great Russian gen-

erals, but his many published and unpublished

writings reveal one of the more perceptive minds

of the tsarist military.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR; RUSSO-

TURKISH WARS; SKOBELEV, MIKHAIL DIMITRIYEVICH;

TURKESTAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kuropatkin, Aleksei N. (1909). The Russian Army and the

Japanese War, tr. A. B. Lindsay. 2 vols. New York:

E. P. Dutton.

Romanov, Boris A. (1952). Russia in Manchuria, tr. Su-

san Wilbur Jones. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Press.

Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David H. (2001). To-

ward the Rising Sun: Russian Ideologies of Empire and

the Path to War with Japan. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illi-

nois University Press.

D

AVID

S

CHIMMELPENNINCK VAN DER

O

YE

KURSK, BATTLE OF

The Battle of Kursk (July 5–August 23, 1943) re-

sulted in the Soviet defeat of the German Army’s

last major offensive in the East and initiated an un-

broken series of Red Army victories culminating in

the destruction of Hitler’s Third Reich. The battle

consisted of Operation Zitadelle, (Citadel), the Ger-

man Army’s summer offensive to destroy Red

Army forces defending the Kursk salient, and the

Red Army’s Operations Kutuzov and Rumyantsev

against German forces defending along the flanks

of the Kursk salient. More than seven thousand So-

viet and three thousand German tanks and self-

propelled guns took part in this titanic battle,

making it the largest armored engagement in the

war.

The defensive phase of the battle began on July

5, 1943, when the 9th Army of Field Marshal

Guenther von Kluge’s Army Group Center and the

4th Panzer Army and Army Detachment Kempf of

Field Marshal Erich von Manstein’s Army Group

South launched concentric assaults against the

northern and southern flanks of the Kursk salient.

In seven days of heavy fighting, the 13th and 70th

Armies and 2nd Tank Army of General K. K.

Rokossovsky’s Central Front fought three German

panzer corps to a virtual standstill in the Ponyri

and Samodurovka regions, seven miles deep into

the Soviet defenses. To the south, during the same

period, three panzer corps penetrated ten to twenty

miles through the defenses of the Voronezh Front’s

6th and 7th Guards and 69th Armies, as well as

the dug in 1st Tank Army, before engaging the

Steppe Front’s counterattacking 5th Guards Army

and 5th Guard Tank Armies in the Prokhorovka

region. Worn down by constant Soviet assaults

against their flanks, the German assault faltered on

the plains west of Prokhorovka. Concerned about

the deteriorating situation in Italy and a new Red

Army offensive to the north, Hitler ended the of-

fensive on July 13.

The day before, the Red Army commenced its

summer offensive by launching Operation Kutu-

zov, massive assaults by five Western and Bryansk

Front armies against German Second Panzer Army

defending the Orel salient. Red Army forces, soon

joined by the 3rd Guards and 4th Tank Armies and

most of the Central Front, penetrated German

defenses around Orel within days and began a

steady advance, which compelled German forces

to abandon the Orel salient by August 23. On Au-

gust 5, three weeks after halting German forces at

Prokhorovka, the Voronezh and Steppe Fronts

commenced Operation Rumyantsev, a massive of-

fensive by ten armies toward Belgorod and

Kharkov. Spearheaded by the 1st and 5th Guards

Tank Armies and soon reinforced by three addi-

tional armies, for the first time in the war the ad-

vancing forces defeated counterattacks by German

operational reserves, and captured Kharkov on Au-

gust 23.

The defeat of Hitler’s last summer offensive at

Kursk marked the beginning of the Red Army sum-

KURSK, BATTLE OF

802

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY