Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

stitution guaranteed the right to private ownership

of land. This right was reaffirmed in the Civil Code,

adopted in 1994.

Starting in 1994, a rudimentary land market

arose, involving the buying and selling of land, in-

cluding agricultural land. The land market was

somewhat restricted in that agricultural land was

to be used only for agricultural purposes. But the

decree was an important first step and had the de-

sired effect: By the end of the 1990s, millions of

land transactions were being registered annually

(although most were lease transactions).

After seven years of heated political disagree-

ment, a post-Soviet Land Code was passed and

signed into law by President Vladimir Putin in Oc-

tober 2001. For the first time since 1917, a Land

Code existed that allowed Russian citizens to pos-

sess, buy, and sell land. The most contentious is-

sue, the right to buy and sell agricultural land, was

omitted from the new Land Code.

Following the passage of the Land Code, the

Putin administration moved quickly to enact a law

regulating agricultural land sales. By June 2002, a

government-sponsored bill on the turnover of agri-

cultural land passed three readings in the State

Duma and was sent to the upper chamber, the Fed-

eration Council, where it was approved in July

2002. Near the end of July 2002, President Putin

signed the bill into law, the first law since 1917 to

regulate agricultural land sales in Russia.

The law that was signed into force was very

conservative, requiring that agricultural land be

used for agricultural purposes. With the exception

of small plots of land, such as household subsidiary

plots, if the owner of privately owned land wished

to sell his land, he was required to offer it to local

governmental bodies, who had one month to ex-

ercise their right of first refusal before the land

could be offered to third parties. If the land was of-

fered to a third party, it could not be at a price

lower than was originally offered to the local

government. Owners of land shares were required

to offer their shares first to other members of the

collective, then to the local government, both of

which had one month to exercise their right of first

refusal. Only if this right was not used could the

shares be sold to a third party, but not at a price

lower than was originally offered to the local gov-

ernment. If the owner changed the price of his land

(or his land shares), then the local government had

to be given the right of first refusal again at the

new price. The law established minimum size lim-

its on land transactions and maximum size limits

on land ownership. Finally, the law provided for

land confiscation (as did the Land Code) if the land

was not used, or was not used for its intended

purpose, or if use resulted in environmental degra-

dation.

See also: AGRICULTURE; COLLECTIVE FARMS; LAND

TENURE, IMPERIAL ERA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Danilov, Viktor P. (1988). Rural Russia under the New

Regime. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Medvedev, Zhores A. (1987). Soviet Agriculture. New

York: Norton.

Wadekin, Karl-Eugen. (1973). The Private Sector in Soviet

Agriculture. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of Califor-

nia Press.

Wegren, Stephen K. (1998). Agriculture and the State in

Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. Pittsburgh, PA: Uni-

versity of Pittsburgh Press.

S

TEPHEN

K. W

EGREN

LANGUAGE LAWS

The issue of language question has been the sub-

ject of recurring political, social, and ideological

controversy in Russia since the fifteenth century.

Both the intellectual elite and the state were in-

volved in discussions of the issue. Until the 1820s

they were primarily concerned with the formation

and functions of the Russian literary language.

EIGHTEENTH AND EARLY

NINETEENTH CENTURIES

Peter the Great’s educational and cultural reforms

were the first direct state involvement in the lan-

guage question in Russia. During the early eigh-

teenth century, governmental orders systematically

regulated and resolved the language system, which

at this time was characterized by the progressive

penetration of original Russian elements into the

established Church Slavonic literary norm and by

a significant increase in the influence of foreign lan-

guages. Peter’s program envisioned the creation of

a civil idiom based on various genres of the

spoken language, and the modernization and sec-

ularization of elevated Church Slavonic, whose re-

sources were insufficient for adequate description

LANGUAGE LAWS

823

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of the vast new areas of knowledge. At the same

time, the language of the epoch was oriented to-

ward Western European languages as sources of

novel information and terminology, and thus there

were many foreign borrowings. The tsar tackled

this problem personally, requiring that official doc-

uments were to be written in plain Russian that

avoided the use of obscure foreign words and terms.

Peter’s nationalization of language culminated in

the 1707 orthography reform. He decreed the cre-

ation of the so-called civil alphabet and removed

eight obsolete letters from Church Slavonic script.

However, in 1710, partly in response to criticism

from the church, Peter reintroduced certain letters

and diacritic signs into the civil alphabet. In spite

of its limitations, Peter’s orthographic reform was

a first step toward the creation of a truly secular,

civil Russian writing system. It paved the way for

three consecutive reforms by the Imperial Academy

of Sciences in 1735, 1738, and 1758 that further

simplified the alphabet.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the lan-

guage question dominated intellectual debate in

Russia. During the first decades of the nineteenth

century, linguistic polemics intensified with the

emergence of Nikolai Karamzin’s modernizing pro-

gram aimed at creating an ideal literary norm for

Russian on the basis of the refined language of high

society. Karamzin’s plan met with a heated re-

sponse from conservatives who wanted to retain

Church Slavonic as a literary language. His oppo-

nents were led by Admiral Alexander Shishkov. In

December 1812, Emperor Alexander I encouraged

the Imperial Russian Bible Society to translate and

publish the scriptures in the empire’s many lan-

guages to promote morality and religious peace be-

tween its peoples. The society distributed tens of

thousands of Bibles in Church Slavonic, French,

German, Finnish, Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian,

Polish, Armenian, Georgian, Kalmyk, and Tatar in

the first year of its existence. The publication of the

scriptures in Russian, however, aroused strong op-

position from the conventional Orthodox clergy,

who eventually persuaded Alexander to change his

position. In 1824 he appointed Admiral Shishkov

to head the Ministry of Education. Shishkov ter-

minated the publication of the Russian Bible and

reestablished Church Slavonic as the sole language

of scripture for Russians.

1860s TO 1917

Starting in the second half of the nineteenth cen-

tury, imperial policy promoted Russian national

values among the non-Russian population of the

empire and established Russian as the official lan-

guage of the state. The government exercised ad-

ministrative control over the empire’s non-Russian

languages through a series of laws that consider-

ably, if not completely, restricted their functions

and spheres of usage.

These laws primarily concerned the Polish and

Ukrainian languages, which were feared as sources

and instruments of nationalism. Russification had

been adopted as the government’s official policy in

Poland in response to the first Polish uprising. Af-

ter the second uprising, in 1863, Polish was ban-

ished from education and official usage. Russian

became the language of instruction. Harsh censor-

ship ensured that most of the classics of Polish lit-

erature could be published only abroad; thus, for

instance, the dramas of the national poet, Adam

Mickiewicz, were not staged in Warsaw.

The suppression of Ukrainian culture and lan-

guage was also a consequence of the 1863 upris-

ing. Ukrainian cultural organizations were accused

of promoting separatism and Polish propaganda,

and in July 1863 Peter Valuev, the minister of in-

ternal affairs, banned the publication of scholarly,

religious, and pedagogical materials in Ukrainian.

Only belles–lettres were to be published in the “Lit-

tle Russian” dialect. In 1875, renewed Ukrainophile

activity again aroused official suspicion. An impe-

rial special commission recommended that the gov-

ernment punish Ukrainian activists and ban the

publication and importation of Ukrainian books,

the use of Ukrainian in the theater and as a lan-

guage of instruction in elementary schools, and the

publication of Ukrainian newspapers. Alexander II

accepted these ruthless recommendations and en-

coded them in the Ems Decree, signed in the Ger-

man town of Ems on May 18, 1876.

Belorusian was also regarded as a dialect of

Russian, but was not officially prohibited because

of the limited scope of its literature. Georgian was

subjected to a number of severe restrictions. Impe-

rial language policy was not liberalized until after

the Revolution of 1905, and then only under enor-

mous public pressure. From 1904 there had also

been democratic projects for alphabet reform,

championed by such famous scholars as Jan Bau-

douin de Courtenay and Filipp Fortunatov. In 1912

the orthography commission submitted its propo-

sitions to the government, but they were never ap-

proved, due to strong opposition in intellectual and

clerical circles. The implementation of the orthog-

LANGUAGE LAWS

824

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

raphy reform, which again removed certain su-

perfluous letters from the alphabet, came only in

October 1918, when the Bolshevik government

adopted the commission’s recommendations.

REVOLUTIONARY AND SOVIET

LANGUAGE POLICY

The language question had always been high on

the Bolshevik political and cultural agenda. Soon

after the Revolution, the Bolshevik government de-

clared a new language policy guaranteeing the

complete equality of nationalities and their lan-

guages. Formulated in a resolution of the Tenth

Communist Party Congress in March 1921, this

policy emphasized that the Soviet state had no of-

ficial language: everyone was granted the right to

use a mother tongue in private and public affairs,

and non-Russian peoples were encouraged to de-

velop educational, administrative, cultural, and

other institutions in their own languages. In prac-

tice, this meant that the more than one hundred

languages of the non-Russian population, of which

only twenty had a written form, had to be made

as complete and functional as possible. The revo-

lutionary language policy was indisputably demo-

cratic in stance, but some observers argue that its

real driving force was the new government’s need

to establish its power and ideology in ethnically and

linguistically diverse parts of the country. In any

case, the language reform of the 1920s and early

1930s was unprecedented in scale. More than forty

unlettered languages received a writing system, and

about forty–five had their writing systems entirely

transformed. During the 1920s a Latinization cam-

paign created new alphabets and transformed old

ones onto a Latin (as opposed to a Cyrillic or Ara-

bic) basis. In February 1926 the First Turcological

Congress in Baku adopted the Latin alphabet as a

basis for the Turkic languages. Despite a few in-

stances of resistance, the language reform was re-

markably successful, and during the early 1930s

education and publishing were available in all the

national languages of the USSR. Between 1936 and

1937 a sharp change in Soviet nationalities policy

led to a sudden decision to transform all of the

country’s alphabets onto a Cyrillic basis. Complete

Cyrillization was implemented much faster than

the previous alphabet reforms. From the late 1930s

until the late 1980s, Soviet language policy in-

creasingly promoted russification. National lan-

guages remained equal in declarations, but in

practice Russian became the dominant language of

the state, culture, and education for all the peoples

of the USSR. It was only at the end of the 1980s,

when a measure of political and cultural self–

determination was restored, that the various Soviet

nations and their languages acquired a higher

status.

THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION

Article 68 of the 1993 constitution of the Russian

Federation declares that Russian is the state lan-

guage. Federal subunits of Russia have the consti-

tutional right to establish their own state languages

along with Russian. The state guarantees protec-

tion and support to all the national languages, with

emphasis on the vernaculars of small ethnic

groups. On December 11, 2002, however, President

Vladimir Putin introduced amendments to the Law

on Languages of the Russian Federation that es-

tablished the Cyrillic alphabet as a compulsory

norm for all of the country’s state languages. Sup-

ported by both chambers of the Russian parliament,

this amendment was strongly opposed by local of-

ficials in Karelia and Tatarstan. Russian lawmak-

ers are also concerned about the purity of the

Russian language. In February 2003 a draft law

prohibiting the use of jargon, slang, and vulgar

words, as well as the use of foreign borrowings in-

stead of existing Russian equivalents, was adopted

by the lower chamber of the Duma but was re-

jected by the Senate. The language issue clearly re-

mains as topical as ever in Russia, and state

language policy may be entering a new phase.

See also: CYRILLIC ALPHABET; EDUCATION; KARAMZIN,

NIKOLAI MIKAILOVICH; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SO-

VIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buck, Christopher D. (1984). “The Russian Language

Question in the Imperial Academy of Sciences.” In

Aspects of the Slavic Language Question, Vol. 2: East

Slavic, ed. Riccardo Picchio and Harvey Goldblatt.

New Haven, CT: Yale Concilium on International

and Area Studies.

Comrie, Bernard. (1981). The Languages of the Soviet

Union. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gasparov, Boris M. (1984). “The Language Situation and

the Linguistic Polemic in Mid–Nineteenth–Century

Russia.” In Aspects of the Slavic Language Question.

Vol. 2: East Slavic, ed. Riccardo Picchio and Harvey

Goldblatt. New Haven, CT: Yale Concilium on In-

ternational and Area Studies.

Hosking, Geoffrey. (2001). Russia and the Russians: A His-

tory. London: Allen Lane.

LANGUAGE LAWS

825

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Kirkwood, Michael, ed. (1989). Language Planning in the

Soviet Union. London: Macmillan.

Kreindler, Isabelle. (1982). “The Changing Status of Russ-

ian in the Soviet Union.” International Journal of the

Sociology of Language 33:7–41.

Kreindler, Isabelle, ed. (1985). Sociolinguistic Perspectives

on Soviet National Languages: Their Past, Present and

Future. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Uspenskij, Boris A. (1984). “The Language Program of

N. M. Karamzin and Its Historical Antecedents.” In

Aspects of the Slavic Language Question. Vol. 2: East

Slavic, ed. Riccardo Picchio and Harvey Goldblatt.

New Haven, CT: Yale Concilium on International

and Area Studies.

V

LADISLAVA

R

EZNIK

LAPPS See SAMI.

LATVIA AND LATVIANS

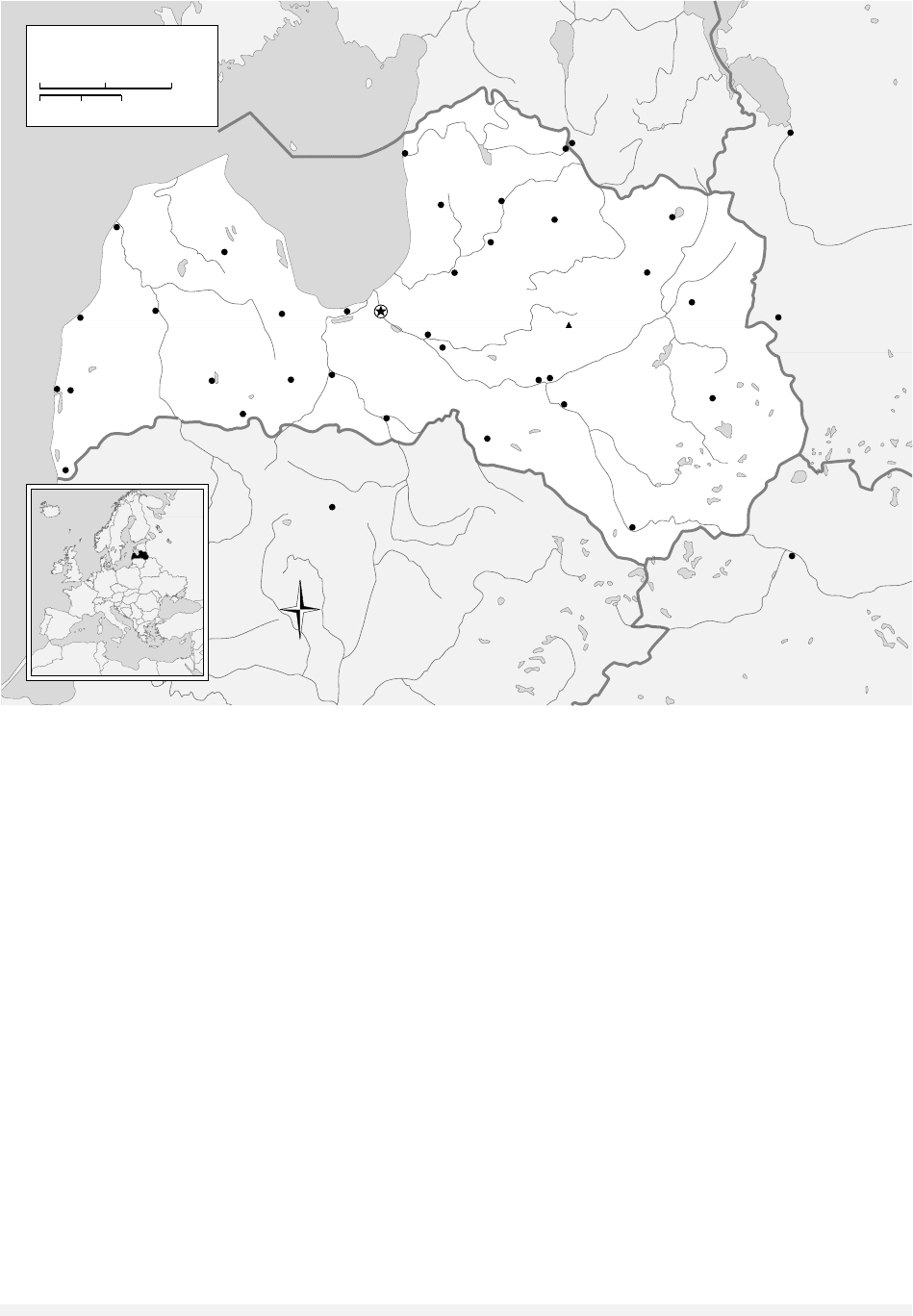

The Republic of Latvia is located on the eastern lit-

toral of the Baltic Sea, and the vast majority of the

world’s Latvians (est. 1.5 million in 2000) live in

the state that bears their name. They occupy this

coastal territory together with the the other two

Baltic peoples with states of their own, the Estoni-

ans and the Lithuanians, as well as a substantial

number of other nationality groups, including Rus-

sians. The complex relationship between this region

and the Russian state goes back to medieval times.

The modern history of this relationship, however,

can be dated to the late eighteenth century, when

the Russian Empire, under Catherine the Great, con-

cluded the process (begun by Peter the Great) of ab-

sorbing the entire region. From then until World

War I, the Latvian population of the region was

subject to the Russian tsar. The disintegration of

the empire during the war led to the emergence of

the three independent Baltic republics in 1918

(Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania), which, however, were

annexed by the USSR in 1940. They were formally

Soviet Socialist Republics until the collapse of the

USSR in 1991. Since then, Latvia and the other

two Baltic republics have been independent coun-

tries, with strong expectations of future member-

ship in both NATO and the European Community.

The notion among political leaders in Russia that

the Baltic territories, among others, were the Russ-

ian “near abroad,” however, remained strong dur-

ing the 1990s.

Before they were united into a single state in

1918, the Latvian-speaking populations of the

Baltic region lived for many centuries in different

though adjacent political entities, each of which had

its own distinct cultural history. The Latvians in

Livonia (Ger. Livland) shared living space with a

substantial Estonian population in the northern

part of the province. Those in the easternmost

reaches of the Latvian-language territory were, un-

til the eighteenth century, under the control of the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and afterward

part of Vitebsk province of the Russian Empire. The

Latvians of Courland (Ger. Kurland), until 1795,

were residents of the semi-independent duchy of

Courland and Semigallia, the dukes owing their

loyalty to the Polish king until the duchy became

part of the Russian Empire. The final acquisition of

all these territories by the Russian Empire was not

accompanied by an internal consolidation of the re-

gion, however, and most of the eighteenth-century

administrative boundaries remained largely un-

changed. Also remaining unchaged throughout the

nineteenth century was the cultural and linguistic

layering of the region. In the Latvian-language ter-

ritories, social and cultural dominance remained in

the hands of the so-called Baltic Germans, a sub-

population that had arrived in the Baltic littoral as

political and religious crusaders in the thirteenth

century and since then had formed seemingly un-

changing upper orders of society. The powerful

Baltic German nobility (Ger. Ritterschaften) and ur-

ban patriciates (especially in the main regional city

of Riga) continued to mediate relations between the

provincial lower orders and the Russian govern-

ment in St. Petersburg.

Most historians hold that a national conscious-

ness that transcended the provincial borders was

starting to develop among the Latvian-speakers of

these provinces during the eighteenth century. The

main national awakening of the Latvians, however,

took place from the mid-1800s onward, and by the

time of World War I had produced a strong sense

of cultural commonality that manifested itself in a

thriving Latvian-language literature, a large num-

ber of cultural and social organizations, and a

highly literate population. Challenging provincial

Baltic German control, some Latvian nationalists

sought help in the Russian slavophile movement;

this search for friends ended, however, with the

systematic russification policies under Alexander III

in the late 1880s, which restricted the use of the

LAPPS

826

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Latvian language in the educational and judicial

systems and thus affected everyday life. Hence-

forth, both the Baltic German political elite and the

Russian government seemed to many Latvian na-

tionalists to be forces inimical to Latvian aspira-

tions for independence.

The main events in the region during the twen-

tieth century changed the nature of the inherited

antagonisms of the Latvian area, but did not solve

them. The emergence of a Latvian state capped the

growth of Latvian nationalism, but created in the

new state the need to resolve the problems of eco-

nomic development, national security, and minor-

ity nationalities. The Russian population in Latvia

in the interwar years remained in the range of 7 to

10 percent. In the fall of 1939 virtually the entire

Baltic German population of Latvia emigrated to

the lands of the Third Reich. World War II, how-

ever, brought annexation by the Soviet Union in

1940, occupation by the Third Reich from 1941 to

1945, and from 1945 the continued sovietization

of the Latvian state that had begun in 1940 and

1941. As a constituent republic of the USSR, the

Latvian SSR from the mid-1940s onward experi-

enced, over the next four decades, an influx of Rus-

sians and Russian-speakers that entirely changed

its nationality structure. Simultaneously, the Lat-

vian language was downgraded in most spheres of

public life and education, and resistance to these

trends was attacked by the Latvian Communist

Party as bourgeois nationalism. The Latvian capi-

tal, Riga, became the headquarters of the Baltic Mil-

itary District, vastly enlarging the presence of the

Soviet military. For many Latvians all these devel-

opments seemed to endanger their language, na-

tional culture, and even national autonomy. Thus

LATVIA AND LATVIANS

827

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Gaizina

1,020 ft.

311 m.

Kolkas Rags

Lubanas

Ezers

¯

Reznas

Ezers

Pskovskoye

Ozero

Usmas

Ezers

Burtnieku

Ezers

Gulf

of

Riga

Baltic

Sea

I

r

v

e

s

ˇ

S

a

u

r

u

m

s

G

a

u

j

a

S

t

e

n

d

e

D

a

u

g

a

v

a

A

i

v

i

e

k

s

t

e

V

e

l

i

k

a

y

a

M

a

l

t

a

D

a

u

g

a

v

a

M

e

m

e

l

e

L

i

e

l

u

p

e

V

e

n

t

a

¯

Valka

Valmiera

Smiltene

Zalve

Cesis¯

Gulbene

Balvi

Ostrov

Pskov

Valga

Ventspils

Talsi

Tukums

Jurmala

¯

Ogre

Kegums

Costini

Plavinas

Jelgava

Dobele

Saldus

Auce

Rucava

Jekabpils

¯

Rezekne

Grobina

Bauska

Navapolatsk

ˇ

Siauliai

Aluksne¯

Salacgriva

Limbazi

Sigulda

Pavilosta

¯

Kuldiga

¯

Liepaja

¯

Daugavpils

Riga

¯

¸

¸¸

¸

LITHUANIA

BELARUS

RUSSIA

ESTONIA

W

S

N

E

Latvia

LATVIA

50 Miles

0

0

50 Kilometers

25

25

ˆ

Latvia, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

the large-scale participation of Latvians (even Com-

munist Party members) in the Latvian Popular

Front in the Gorbachev period was not surprising,

and the view that Latvia should reclaim its inde-

pendence became a powerful political force from

1989 onward.

The collapse of the USSR and the return of Lat-

vian independence left the country with a popula-

tion of about 52 percent ethnic Latvians and 48

percent Russians, Ukrainians, Belorussians, and

others. In 2001 the proportion of Latvians stood at

57.9 percent, the other nationalties having been re-

duced by emigration and low fertility rates. About

40 percent of the Slavic minority populations were

Latvian citizens, leaving the social and political in-

tegration of other members of these populations as

one of the principal problems as the country be-

came integrated into Western economic, social, and

security organizations.

See also: CATHERINE I; ESTONIA AND ESTONIANS; NA-

TIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLI-

CIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Misiunas, Romuald, and Taagepera, Rein. (1993). The

Baltic States: Years of Dependence, 1940–1990. Berke-

ley: University of California Press.

Plakans, Andrejs. (1995). The Latvians: A Short History.

Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1995.

Plakans, Andrejs. (1997). Historical Dictionary of Latvia.

Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Rauch, Georg von. (1974). The Baltic States: The Years of

Independence, 1917–1940. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

A

NDREJS

P

LAKANS

LAW CODE OF 1649

The Russian/Muscovite law code of 1649, formally

known as the sobornoye ulozhenie (or Ulozhenie, the

name of the code, which will be used in the arti-

cle), was one of the great legal monuments of all

time. Historically, in Russia, it is probably the sec-

ond most important literary monument composed

LAW CODE OF 1649

828

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

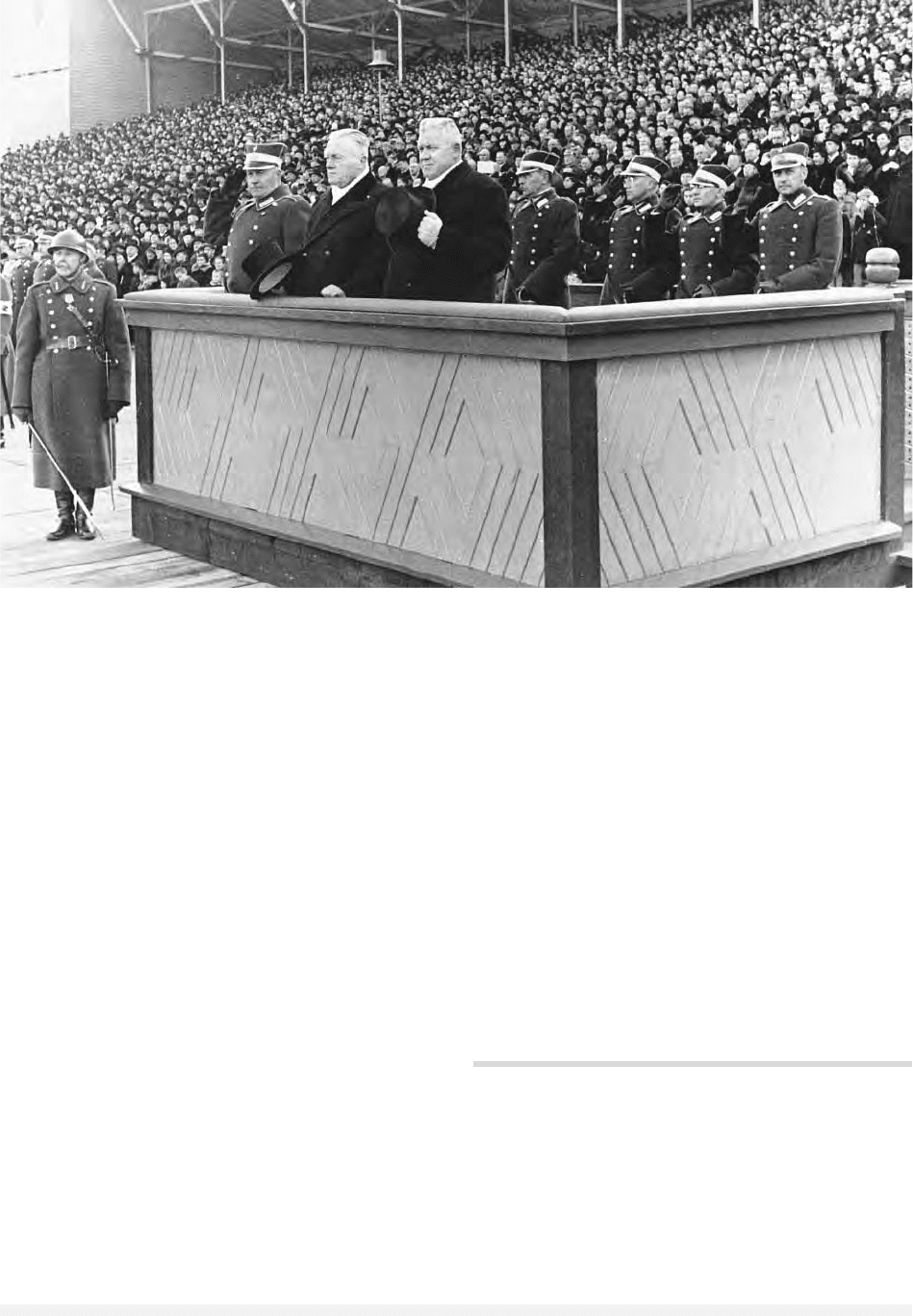

President Karlis Ulmanis reviews troops at an Independence Day parade (c. 1935). His great-nephew Guntis Ulmanis was the first

president of post-Soviet Latvia. © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

between 882 and at least 1800, outranked only by

the various redactions of the Russian chronicle.

Like some other major legal monuments in

Russian history, the Law Code of 1649 was the

product of civil disorder. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich

had come to the throne at age 16 in 1645. His for-

mer tutor, Boris Morozov, was ruling in his name.

Morozov and his clique, at the pinnacle of corrup-

tion, aroused great popular discontent. A crowd

formed in Moscow on June 2, 1648, and presented

a petition to Tsar Alexei, whose accompanying

bodyguards tore it up and flung it back into the

faces of the petitioners, who, joined by others, then

went on a looting and burning rampage. The re-

bellion soon spread to a dozen other Russian towns.

Inter alia, the petitioners cited judicial abuses by the

Morozov clique, mentioned that great rulers in

Byzantium had compiled law codes, and demanded

that Alexei follow suit.

To calm the mob, Alexei agreed that a new law

code should be compiled and on July 16 appointed

one of the leading figures of the seventeenth cen-

tury, Nikita Odoyevsky, to head a commission of

five to compile it. Three of them were experienced

bureaucrats who together had decades of experi-

ence working in the Moscow central governmen-

tal chancellery system (the prikazy). The Odoyevsky

Commission set to work immediately, and the pre-

amble to the Law Code explains how they worked.

They asked the major chancelleries (about ten of

the existing forty) for their statute books (us-

tavnye/ukaznye knigi), the decisions of the chancel-

leries on scrolls. The scrolls summarized the cases

and contained the resolutions for each case. The

Odoyevsky Commission selected the most impor-

tant resolutions and tried to generalize them by re-

moving the particulars of each case as well as put

them in logical order (on the scrolls they were in

chronological order). Depending on how frequently

the resolutions had been used and how old they

were, the fact that many of the Law Code’s arti-

cles were summaries from the statute books is more

or less apparent. When seeking precedents to re-

solve a case, the chancelleries frequently wrote to

each other asking for guidance, with the result that

similar resolutions sometimes can be found in sev-

eral statute books. Fires during the Time of Trou-

bles had destroyed most of the chancellery records;

the chancelleries restored some of these by writing

to the provinces requesting legal materials sent

from Moscow before 1613. The same approach was

used after a fire in 1626 again had destroyed many

of the chancellery records.

The chancelleries had other sources of prece-

dents, some of which are mentioned in the Law

Code itself (in the preamble and rather often in mar-

ginalia on the still-extant original scroll copy of the

Law Code) and others that can be found by com-

paring the chancellery scrolls and other laws with

the Law Code. Major sources were Byzantine law,

which circulated in Russia in the Church Statute

Book (the Kormchaya kniga, a Russian version of

the Byzantine Nomocanon) and the Lithuanian

Statute of 1588 (which had been translated from

West Russian into Muscovite Middle Russian

around 1630). In addition to the chancellery

records, the Sudebnik (Court Handbook) of 1550

was a source for the chancelleries and for the 1649

monument.

By October 3, 1648, the Odoyevsky Commis-

sion had prepared a preliminary draft of half of the

new code. In response to the June riots, Tsar Alexei

changed the personnel of his government and sum-

moned an Assembly of the Land to consider the

new law code. The Odoyevsky Commission draft

was read to the delegates to the Assembly of the

Land, who apparently voted up or down each ar-

ticle. In addition, the delegates brought their own

demands, which were incorporated into the new

code and comprised about eighty-three articles of

all the 968 articles in the code. From 77 to 102 ar-

ticles originated in Byzantium, 170 to 180 in the

Lithuanian Statute of 1588. From 52 to 118 came

from the Sudebnik of 1550, and 358 can be traced

to post-1550 (primarily post-1613) practice.

The code’s 968 articles are grouped into twenty-

five chapters. The Sudebniki of 1497, 1550, and

1589 had been arranged one article after another,

but the Composite Sudebnik of 1606 was grouped

into chapters (twenty-five of them), as was the

Lithuanian Statute of 1588. The architecture of the

code is also interesting, from “the highest, the sub-

lime” (the church, religion: chapter 1; the tsar and

his court: chapters 2 and 3) to “the lowest, the

gross” (musketeers: chapter 23; cossacks: chapter

24; and illicit taverns: chapter 25). Although there

are a handful of codification defects in the code,

they are few in number and trivial. The entire doc-

ument was considered by the Assembly of the Land

and signed by most of the delegates on January 29,

1649. Those who withheld their signatures were

primarily churchmen who objected to the code’s

semi-secularization of the church (see below). Al-

most immediately the scroll copy was sent to the

printer, and twelve hundred copies were manufac-

tured between April and May 20. The Ulozhenie was

LAW CODE OF 1649

829

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the second lay book published in Muscovy. (The

first was Smotritsky’s Grammar, published in

1619.) The price was high (one ruble; the median

daily wage was four kopeks), but the book sold out

almost immediately, and another twelve hundred

copies were printed, with some minor changes, be-

tween August 27 and December 21, 1649. They

also sold out quickly. The Ulozhenie was subse-

quently reprinted eight times as an active law code,

and it served as the starting point for the famous

forty-five-volume Speransky codification of the

laws in 1830. It has been republished eight times

after 1830 because of its enormous historical in-

terest. In 1663 it was translated into Latin and

subsequently into French, German, Danish, and

English.

Commentators have marveled that the Odoyev-

sky Commission was able to produce such a re-

markable monument at all, let alone in so short a

time. Until 1830, other codification attempts were

made, but they all failed. Certainly the success of

the code can be attributed largely to the prepara-

tion on the part of the Odoyevsky Commission:

They brought a nearly finished document to the

Assembly of the Land for approval and amend-

ment. In contrast, Catherine II’s Legislative Com-

mission of 1767 failed miserably because it had no

draft to work from, but started instead from ab-

stract principles and went nowhere. The speed of

the Odoyevsky Commission is also easy to account

for: Each chapter is based primarily on an extrac-

tion of the laws from a specific chancellery’s statute

book or demands made at the Assembly of the

Land. The Odoyevsky Commission made no at-

tempt to write law itself or to fill lacunae in exist-

ing legislation.

The Law Code of 1649 is a fairly detailed record

of its times, practices, and major concerns. Most

noteworthy are the additions insisted on by the del-

egates to the Assembly of the Land, amendments

which the government was too weak and fright-

ened to oppose. Three areas are especially signifi-

cant: the completion of the enserfment of the

peasantry (chapter 11), the completion of the legal

stratification of the townsmen (chapter 19), and

the semi-secularization of the church (chapters 13,

14, and 19).

While the peasants were enserfed primarily at

the demands of others (the middle service class

provincial cavalry), the townsmen were stratified

into a caste at their own insistence. Urban strati-

fication and enserfment proceeded in parallel from

the early 1590s on, but the resolutions in the

Ulozhenie were different. Serfs could be returned to

any place of which there was record of their hav-

ing lived in the past, but townsmen were enjoined

to remain where they were in January 1649 and

could be returned only if they moved after that

time. Enserfment was motivated by provincial cav-

alry rent demands, while townsmen stratification

was motivated by state demands for taxes, which

were assessed collectively and were hard to collect

when those registered in a census (taken most re-

cently in 1646–1647) moved away. The townsmen

got monopolies on trade and manufacturing, as

well as on the ownership of urban property (this

primarily dispossessed the church). Roughly the

same rules applied to fugitive townsmen as fugi-

tive serfs, especially when they married.

If one thinks in terms of victimization, the pri-

mary “victim” of the Law Code of 1649 (after the

serfs) was the Orthodox Church. As mentioned,

much of its urban property was secularized. Its ca-

pacity to engage in trade and manufacturing was

compromised. The state laid down provisions for

protecting the church in chapter 1, but this in and

of itself states which party is superior and limits

the “harmony” (from the Byzantine Greek Epanogoge)

of the two. Chapter 12 discusses the head of the

church, the patriarch, thus obviously making him

subordinate to the state. Worst of all for the church

was chapter 13, which created the Monastery

Chancellery, a state office which in theory ran all

of the church except the patriarchate. This measure

especially secularized much of the church, and

though it was repealed on Alexei’s death in 1676,

it was revitalized with a vengeance by Peter the

Great’s creation of the Holy Synod in 1721, when

all of the church became a department of the state.

The Ulozhenie also forbade the church from ac-

quiring additional landed property, the culmination

of a process which had begun with the confisca-

tion of all of Novgorod’s church property after its

annexation by Moscow in 1478.

The Law Code of 1649 is a comprehensive doc-

ument, the product of an activist, interventionist,

maximalist state that believed it could control

many aspects of Russian life and the economy (es-

pecially the primary factors, land and labor). Chap-

ters 2 and 3 protected the tsar and regulated life at

his court. The longest chapter, 10, is quite detailed

on procedure. The major forms of landholding, ser-

vice lands (pomestye) and hereditary estate lands,

are discussed in chapters 16 and 17, respectively.

Slavery is the subject of the code’s second longest

chapter, 20. Criminal law is covered in two chap-

LAW CODE OF 1649

830

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ters, 21 (mostly of Russian origin) and 22 (mostly

of Lithuanian and Byzantine origin), which were

combined in the 1669 Felony Statute and repre-

sented the peak of barbarous punishments in Russia.

Other subjects covered are forgers and counterfeit-

ers (chapters 4 and 5), travel abroad (typically for-

bidden, chapter 6), military service (chapter 7), the

redemption of Russians from foreign military cap-

tivity (chapter 8), various travel fees (chapter 9)

and seal fees (chapter 18), the oath (chapter 14),

and the issue of reopening resolved cases (chapter

15). Codes as comprehensive and activist as this

one did not appear in Austria, Prussia, or France

until more than a century later.

See also: ALEXEI MIKHAILOVICH; ASSEMBLY OF THE LAND;

KORMCHAYA KNIGA; MOROZOV, BORIS IVANOVICH;

PEASANTRY; SERFDOM; SUDEBNIK OF 1497; SUDEBNIK

OF 1550; SUDEBNIK OF 1589

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1965). “Muscovite Law and Society: The

Ulozhenie of 1649 as a Reflection of the Political and

Social Development of Russia since the Sudebnik of

1589.” Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago.

Hellie, Richard. (1979). “The Stratification of Muscovite

Society: The Townsmen.” Russian History 6(2):

119–175.

Hellie, Richard. (1988–1991). “Early Modern Russian

Law: The Ulozhenie of 1649.” Russian History 2(4):

115–224.

Hellie, Richard. (1989–1990). “Patterns of Instability in

Russian and Soviet History.” Chicago Review of Inter-

national Affairs, 1(3):3–34; 2(1):3–15.

Hellie, Richard. (1992). “Russian Law from Oleg to Peter

the Great.” Foreword to The Laws of Rus’: Tenth to

Fifteenth Centuries, tr. and ed. Daniel H. Kaiser. Salt

Lake City, UT: Charles Schlacks.

Hellie, Richard, ed. and tr. (1967, 1970). Muscovite Soci-

ety: Readings for Introduction to Russian Civilization.

Chicago: University of Chicago.

Hellie, Richard, ed. and tr. (1988). The Muscovite Law Code

(Ulozhenie) of 1649. Irvine, CA: Charles Schlacks.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

LAY OF IGOR’S CAMPAIGN

A twelfth-century literary masterpiece, the Lay of

Igor’s Campaign was probably composed soon af-

ter the unsuccessful 1185 campaign of Prince Igor

of Novgorod–Seversk and his brother Vsevolod of

Kursk against the Cumans (Polovtsians) of the

steppe. The Lay (Slovo o polku Igoreve), by an anony-

mous author, minimizes narrative of facts (which

were presumably fresh in the minds of the audi-

ence, and which are known to scholars from the

Hypatian Chronicle and others) and instead evokes

the heroic spirit of the time and the need for unity

among the princes. Hence its title, Slovo, meaning

a speech or discourse, not a story and not verse

(the English translation “Lay” is misleading).

Though the text was heavily influenced by East

Slavic folklore, it is nonetheless a sophisticated lit-

erary work. Its rhythmical prose approaches po-

etry in the density of its imagery and the beauty

of its sound patterns. The images are taken mainly

from nature and Slavic mythology. A solar eclipse,

the calls of birds of omen, and creatures of myth

(the Div) foreshadow Igor’s defeat on the third day

of battle. Trees and grass droop in sorrow for hu-

man disaster.

The technique is that of mosaic, of sparkling

pieces juxtaposed to create a brilliant whole. Scenes

and speeches shift with hardly any explicit transi-

tions. To understand the message requires paying

strict attention to juxtaposition. For example, the

magic of Vseslav followed immediately by the

magic of Yaroslavna and the apparent sorcery of

Igor.

Very few Christian motifs appear; those that

do are primarily toward the close. Instead, there are

the frequent mentions of pagan gods and

pre–Christian mythology. Even so, the Lay should

not be considered a neo–pagan work; rather its bard

seems to use this imagery to create an aura of olden

times, the time of the grandfathers and their bard,

Boyan. The principle of two historical levels, re-

peatedly invoked, serve the purpose of creating the

necessary epic distance impossible for recent events

by themselves, and also sets up a central theme:

The princes of today should emulate the great deeds

of their forefathers while avoiding the mistakes. Ex-

tolling Igor and his companions as heroes, the bard,

mostly through the central speech of Grand Prince

Svyatoslav, also calls for replacing their drive for

personal glory with a new ethic of common de-

fense.

The Lay was first published in 1800, report-

edly from a sole surviving North Russian copy of

the fifteenth or sixteenth century acquired by

Count Alexei Musin–Pushkin. The supposed loss of

the manuscript in the fire of Moscow in 1812 has

made it possible for some skeptics over the years

LAY OF IGOR’S CAMPAIGN

831

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

to challenge the work’s authenticity, speculating

that it was a fabrication of the sixteenth century

(Alexander Zimin) or even the 1790s (Andrÿea Ma-

zon). Up to a point, this has been a classic con-

frontation of historians and philologists, each

group claiming priority for its own method and

viewpoint. Much depends on how one views its re-

lationship with Zadonshchina, which clearly bears

some genetic connection to it, almost certainly as

a later imitation of the Lay.

Despite the unproven doubts and suspicions of

a few, the Slovo o polku Igoreve, in its language, im-

agery, style, and themes, is perfectly compatible

with the late twelfth century, as was demonstrated

by leading scholars such as Roman Jakobson,

Dmitry Likhachev, Varvara Adrianova–Peretts, and

many others. It remains one of the masterpieces of

all East Slavic literature.

See also: FOLKLORE; ZADONSHCHINA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zenkovsky, Serge A., tr. and ed. (1974). Medieval Rus-

sia’s Epics, Chronicles, and Tales, 2nd ed. rev. New

York: Dutton.

N

ORMAN

W. I

NGHAM

LAZAREV INSTITUTE

The Lazarev Institute (Lazarevskii institut vos-

tochnykh iazykov) was founded in Moscow in 1815

by the wealthy Armenian Lazarev (Lazarian) fam-

ily primarily as a school for their children. In 1827

the school was named the Lazarev Institute of

Oriental Languages (Oriental in the nineteenth-

century sense, including the Middle East and North-

ern Africa) by the State and placed under the su-

pervision of the Ministry of Public Education. For

the next twenty years the Lazarev Institute func-

tioned as a special gymnasium that offered lan-

guage courses in Armenian, Persian, Turkish, and

Arabic, in addition to its regular curriculum in

Russian. The student body was composed mostly

of Armenian and Russian boys aged ten to four-

teen. In 1844 there were 105 students: seventy-

three Armenians, thirty Russians, and two others.

In 1848 the Institute was upgraded to a lyceum

and offered classes in the aforementioned languages

for the upper grades. The Institute trained teachers

for Armenian schools, Armenian priests, and, most

importantly, Russian civil servants and inter-

preters. The government, responding to the im-

portance of the Institute’s role in preparing men to

administer the diverse peoples of the Caucasus,

funded and expanded the program. Many Armen-

ian professionals and Russian scholars specializing

in Transcaucasia received their education at the

Lazarev Institute. In 1851 Armenians, Georgians,

and even a few Muslims from Transcaucasia were

permitted to enroll in the preparatory division,

where, in addition to various subjects taught in

Russian, they also studied their native tongues. The

Russian conquest of Daghestan and plans to ex-

pand further into Central Asia made the Lazarev

Institute even more necessary. In 1872, following

the Three-Emperors’ League, Russia was once again

free to pursue an aggressive policy involving the

Eastern Question. The State divided the institution

into two educational sections. The first served as a

gymnasium, while the second devoted itself to a

three-year course in the languages (Armenian, Per-

sian, Arabic, Turkish, Georgian), history, and cul-

ture of Transcaucasia.

The Lazarev Institute had its own printing press

and, beginning in 1833, published important works

in thirteen languages. It also published two jour-

nals, Papers in Oriental Studies (1899–1917) and the

Emin Ethnographical Anthology (six issues). Its li-

brary had some forty thousand books in 1913.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution, on March

14, 1919, the Council of the People’s Commissars

of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic

(RSFSR) renamed the Institute the Armenian Insti-

tute and, soon after, the Southwest Asian Institute.

In 1920 it was renamed the Central Institute of Liv-

ing Oriental Languages. A year later it was renamed

the Moscow Oriental Institute. In October 1921, a

section of the Institute was administered by Soviet

Armenia and became a showcase devoted to Ar-

menian workers and peasants. By the 1930s the

Institute lost its students to the more prestigious

foreign language divisions in Moscow and Lenin-

grad. Its library collection was transferred to the

Lenin Library of Moscow. In the last four decades

of the USSR, the building of the Institute was home

to the permanent delegation of Soviet Armenia to

the Supreme Soviet. Following the demise of the

USSR, the building of the Institute became the Ar-

menian embassy in Russia.

See also: ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS; EDUCATION; NA-

TIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

LAZAREV INSTITUTE

832

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY