Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bournoutian, George. (1998). Russia and the Armenians

of Transcaucasia, 1797–1889: A Documentary Record.

Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Press.

Bournoutian, George. (2001). Armenians and Russia,

1626–1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA:

Mazda Press.

G

EORGE

B

OURNOUTIAN

LAZAREVSKAYA, YULIANYA USTINOVNA

See OSORINA, YULIANYA USTINOVNA.

LEAGUE OF ARMED NEUTRALITY

Already annoyed by American privateer interfer-

ence with Anglo-Russian maritime trade in the

1770s, Catherine the Great was even more frus-

trated by British countermeasures that intercepted

and confiscated neutral shipping suspected of aid-

ing the rebellious American colonies. In March

1780 she issued a Declaration of Armed Neutrality

that became the basic doctrine of maritime law re-

garding neutral rights at sea during war. It defined,

simply and clearly, the rights of neutral vessels,

contraband (goods directly supportive of a military

program), and the conditions and restrictions of an

embargo, and overall defended the rights of neu-

trals (the flag covers the cargo) against seizure and

condemnation of nonmilitary goods. Having al-

ready established herself in the forefront of en-

lightened rulers, Catherine invited the other nations

of Europe to join Russia in arming merchant ves-

sels against American or British transgression of

these rights. Because of the crippling of American

commerce, most of the infractions were by the

British.

Coming at this stage in the War for Indepen-

dence, the Russian declaration boosted American

morale and inspired the Continental Congress to dis-

patch Francis Dana to St. Petersburg to secure more

formal recognition and support. Although Russia

had little in the way of naval power to back up the

declaration, it encouraged France and other coun-

tries to aid the American cause. Britain reluctantly

stood by while a few French and Dutch ships un-

der the Russian flag entered American ports, bring-

ing valuable supplies to the hard-pressed colonies.

Even more supplies entered the United States via the

West Indies with the help of a Russian adventurer,

Fyodor Karzhavin. The military effect was minimal,

however, because the neutral European states hes-

itated about making commitments because of fear

of British retaliation. By 1781, however, the United

Provinces (the Netherlands), Denmark, Sweden,

Austria, and Prussia had all joined the league.

The league was remembered in the United

States, somewhat erroneously, as a mark of Russ-

ian friendship and sympathy, and bolstered An-

glophobia in the two countries. More generally, it

affirmed a cardinal principle of maritime law that

continues in effect in the early twenty-first cen-

tury. Indirectly, it also led to a considerable ex-

pansion of Russian-American trade from the 1780s

through the first half of the nineteenth century.

See also: CATHERINE II; ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bolkhovitinov, Nikolai N. (1975). The Beginnings of Russ-

ian-American Relations, 1775–1815. New Haven: Yale

University Press.

Madariaga, Isabel de. (1963).Britain, Russia and the Armed

Neutrality of 1780. London: Macmillan.

Saul, Norman E. (1991). Distant Friends: The United States

and Russia, 1763–1867. Lawrence: University Press

of Kansas.

N

ORMAN

E. S

AUL

LEAGUE OF NATIONS

Formed by the victorious powers in 1919, the

League of Nations was designed to enforce the

Treaty of Versailles and the other peace agreements

that concluded World War I. It was intended to re-

place secret deals and war, as means for settling in-

ternational disputes, with open diplomacy and

peaceful mediation. Its charter also provided a

mechanism for its members to take collective ac-

tion against aggression.

Soviet Russia and Weimar Germany initially

were not members of the League. At the time of

the League’s founding, the Western powers had in-

vaded Russia in support of the anticommunist side

in the Russian civil war. The Bolshevik regime was

hostile to the League, denouncing it as an anti-

Soviet, counterrevolutionary conspiracy of the im-

perialist powers. Throughout the 1920s, Soviet

Commissar of Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin

aligned the USSR with Weimar Germany, the other

outcast power, against Britain, France, and the

LEAGUE OF NATIONS

833

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

League. German adherence to the Locarno Accords

with Britain and France in 1925, and Germany’s

admission to the League in 1926, dealt a blow to

Chicherin’s policy. This Germanophile, Anglo-

phobe, anti-League view was not shared by Deputy

Commissar of Foreign Affairs Maxim Litvinov,

who advocated a more balanced policy, including

cooperation with the League. Moreover, the USSR

participated in the Genoa Conference in 1922 and

several League-sponsored economic and arms con-

trol forums later in the decade.

Chicherin’s retirement because of ill health, his

replacement as foreign commissar by Litvinov, and,

most importantly, the rise to power of Adolf Hitler

in Germany served to reorient Moscow’s policy.

The Third Reich now replaced the British Empire as

the main potential enemy in Soviet thinking. In De-

cember 1933 the Politburo adopted the new Col-

lective Security line in foreign policy, whereby the

USSR sought to build an alliance of anti-Nazi pow-

ers to prevent or, if necessary, defeat German ag-

gression. An important part of this strategy was

the attempt to revive the collective security mech-

anism of the League. To this end, the Soviet Union

joined the League in 1934, and Litvinov became the

most eloquent proponent of League sanctions

against German aggression. Soviet leaders also

hoped that League membership would afford Rus-

sia some protection against Japanese expansionism

in the Far East. Unfortunately, the League had al-

ready failed to take meaningful action against

Japanese aggression in Manchuria in 1931, and it

later failed to act against the Italian attack on

Ethiopia in 1935. Soviet collective security policy

in the League and in bilateral diplomacy faltered

against the resolution of Britain and France to ap-

pease Hitler.

When Stalin could not persuade the Western

powers to ally with the USSR, even in the wake of

the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, he aban-

doned the collective security line and signed the

Nazi-Soviet Pact with Hitler on August 23, 1939.

Subsequent Soviet territorial demands on Finland

led to the Winter War of 1939–1940 and to the ex-

pulsion of the USSR from the League as an ag-

gressor. However, Hitler’s attack on Russia in 1941

accomplished what Litvinov’s diplomacy could not,

creating an alliance with Britain and the United

States. The USSR thus became in 1945 a founding

member of the United Nations, the organization

that replaced the League of Nations after World

War II.

See also: CHICHERIN, GEORGY VASILIEVICH; LITVINOV,

MAXIM MAXIMOVICH; NAZI-SOVIET PACT OF 1939;

UNITED NATIONS; WORLD WAR I; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buzinkai, Donald I. (1967). “The Bolsheviks, the League

of Nations, and the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.”

Soviet Studies 19:257–263.

Haigh, R.H.; Morris, D.S.; and Peters, A.R. (1986). Soviet

Foreign Policy: The League of Nations and Europe,

1917–1939. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes and Noble.

Haslam, Jonathan. (1984). The Soviet Union and the Strug-

gle for Collective Security in Europe, 1933–39. New

York: St. Martin’s Press.

Jacobson, Jan. (1994). When the Soviet Union Entered

World Politics. Berkeley: University of California

Press.

T

EDDY

J. U

LDRICKS

LEAGUE OF THE MILITANT GODLESS

One of the early Soviet regime’s most ambitious

attempts at social engineering, the League of the

Militant Godless (Soyuz voinstvuyushchikh bezbozh-

nikov) was also one of its most dismal failures.

Founded in 1925 as the League of the Godless, it

was one of numerous volunteer groups created in

the 1920s to help extend the regime’s reach into

Russian society. These organizations hoped to at-

tract nonparty members who might be sympa-

thetic to individual elements of the Bolshevik

program. The word “militant” was added in 1929

as Stalin’s Cultural Revolution gathered speed, and

at its peak in the early 1930s, the League claimed

5.5 million dues-paying bezbozhniki (godless).

Organized like the Communist Party, the League

consisted of cells of individual members at facto-

ries, schools, offices, and living complexes. These

cells were managed by local councils subordinated

to regional and provincial bodies. A League Central

Council presided in Moscow. Despite the League’s

nominal independence, it was directed at each level

by the corresponding Communist Party organiza-

tion.

The League’s mandate was to disseminate athe-

ism, and, to achieve this goal, it orchestrated pub-

lic campaigns for the closure of churches and the

prohibition of church bell pealing. It staged demon-

strations against the observance of religious holi-

days and the multitude of daily Orthodox practices.

LEAGUE OF THE MILITANT GODLESS

834

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The League also arranged lectures on themes such

as the existence of God, Biblical miracles, astron-

omy, and so forth. The League’s Central Council

published a raft of antireligious publications in

Russian and in the languages of national minori-

ties. Larger provincial councils issued their own an-

tireligious periodicals.

The League’s rapid organizational rise seemed

to embody the Bolshevik success in transforming

Holy Russia into the atheistic Soviet Union. But ap-

pearances were misleading. In ironic obeisance to

Marxist dialectics, the League reached its organiza-

tional peak in the early 1930s before collapsing ut-

terly a few years later when, consolidation taking

priority over Cultural Revolution, the Party with-

drew the material support that had sustained the

League’s rise. The League’s disintegration cast its

earlier successes as a “Potemkin village” in the Russ-

ian tradition. In the League’s case, the deception

was nearly complete: Only a fraction of the

League’s nominal members actually paid dues.

Many joined the League without their knowledge,

as a name on a list submitted by a local party of-

ficial. Overworked local party officials often viewed

League activities as a last priority. The population

largely ignored the League’s numerous publica-

tions. Local antireligious officials often succeeded in

drawing the ire of the local community in their

ham-handed efforts to counter Orthodoxy. Indeed,

the local versions of debates in the early and mid-

1920s between leading regime propagandists and

clergymen went so poorly that they were prohib-

ited by the late 1920s.

The final irony was that whatever seculariza-

tion occurred in the 1920s and 1930s, little of it

can be attributed to the League. Orthodoxy’s re-

treat in this period was due to the raw exercise of

state power that resulted in the closure of tens of

thousand of churches and the arrest of many

priests. Urbanization and industrialization played

their part, as did the flood of new spaces, images,

and associations that accompanied the creation of

Soviet culture. Only in this final element did the

League play a role, and it was a very minor one.

The League may have been a symbol of secular-

ization but was hardly an agent of it.

After a brief revival in the late 1930s, the

League faded once again into the background as

World War II brought an accommodation with re-

ligion. It was formally disbanded in 1947, four

years after the death of its founder and leader, Emil-

ian Yaroslavsky. Yaroslavsky, an Old Bolshevik,

had been a leading propagandist in the 1920s and

1930s. An ideological chameleon, he survived two

decades of ideological twists and turns and died a

natural death in 1943 at the age of sixty-five.

Despite its ultimate failure, the League put into

clear relief the regime’s fundamental approach to

the task of social transformation. Highlighting Bol-

shevism’s faith in the power of organization and

building on the tradition of Russian bureaucracy,

the regime emphasized the organizational manifes-

tation of a desired sentiment to such an extent that

it eventually superseded the actual sentiment. The

state of atheism in Soviet Russia was essentially the

same as the state of the League, as far as the regime

was concerned. As long as the League was visible,

the regime assumed that it had achieved one of its

ideological goals. Moreover, the atheism promoted

by the League looked a great deal like a secular re-

ligion. Here the regime appeared to be taking the

path of least resistance, by which fundamental cul-

ture was not changed but simply given a new gloss.

This approach boded ill for the long-term success

of the Soviet experiment with culture and for the

Soviet Union itself.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Husband, William. (1998). “Soviet Atheism and Russian

Orthodox Strategies of Resistance, 1917–1932.”

Journal of Modern History 70(1):74–107.

Husband, William. (2000). Godless Communists: Atheism

and Society in Soviet Russia, 1917–1932. DeKalb:

Northern Illinois University Press.

Peris, Daniel. (1995). “Commissars in Red Cassocks: For-

mer Priests in the League of the Militant Godless.”

Slavic Review 54(2):340–364.

Peris, Daniel. (1998). Storming the Heavens: The Soviet

League of the Militant Godless. Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University Press.

D

ANIEL

P

ERIS

LEBED, ALEXANDER IVANOVICH

(1950–2002), Soviet, airborne commander, Afghan

veteran, commander of the Fourteenth Army, Sec-

retary of the Russian security council, and gover-

nor of Krasnoyarsk oblast.

Alexander Lebed graduated from the Ryazan

Airborne School in 1973 and served in the Airborne

LEBED, ALEXANDER IVANOVICH

835

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Forces. From 1981 to 1982 he commanded an air-

borne battalion in Afghanistan, and then attended

the Frunze Military Academy from 1982 to 1985.

In 1988 he assumed command of an airborne di-

vision, which deployed to various ethno-national

hot spots within the USSR, including Tbilisi and

Baku. An associate of General Pavel Grachev, the

Commander of Airborne Forces, Lebed was ap-

pointed Deputy Commander of Airborne Forces in

February 1991. In August, Lebed commanded the

airborne troops sent to secure the Russian White

House during the attempted August coup against

Gorbachev. In a complex double game, Lebed nei-

ther secured the building nor arrested Yeltsin. In

1992 Pavel Grachev appointed him commander of

the Russian Fourteenth Army in Moldova. Lebed

intervened to protect the Russian population in the

self-proclaimed Transdneistr Republic, which was

involved in an armed struggle with the government

of Moldova. Lebed became a hero to Russian na-

tionalists. But in 1993 Lebed refused to support the

Red-Browns opposing Yeltsin. In 1994 he spoke out

against the Yeltsin government’s military inter-

vention in Chechnya, calling it ill prepared and ill

conceived. In 1995 Lebed was retired from the mil-

itary at President Yeltsin’s order. In December 1995

he was elected to the State Duma. He then ran for

president of Russia on the Congress of Russian

Communities ticket with a nationalist and populist

program and finished third (14.7% of the vote) in

the first round of the 1996 election, behind Yeltsin

and Zyuganov. Yeltsin brought Lebed into his ad-

ministration as Secretary of the Security Council

to ensure his own victory in the second round of

voting. But Lebed proved an independent actor,

and in August, when the war in Chechnya re-

erupted, Lebed sought to end the fighting to

save the Army, accepted a cease–fire, and signed

the Khasavyurt accords with rebel leader Aslan

Maskhadov. The accords granted Chechnya auton-

omy but left the issue of independence for resolu-

tion by 2001. Lebed’s actions angered Yeltsin’s close

associates, including Minister of Internal Affairs

Anatoly Kulikov, who engineered Lebed’s removal

from the government in October 1996. Yeltsin

justified the removal on the grounds that Lebed

was a disruptive force within the government. In

1998 Lebed ran successfully for the post of Gover-

nor of Krasnoyarsk Oblast. On April 28, 2002, he

was killed in a helicopter crash outside Krasno-

yarsk.

See also: MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET; TRANS-

DNIESTER REPUBLIC

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kipp, Jacob W. (1996). “The Political Ballet of General

Aleksandr Ivanovich Lebed: Implications for Russia’s

Presidential Elections.” Problems of Post-Communism

43:43–53.

Kipp, Jacob W. (1999). “General-Lieutenant Aleksandr

Ivanovich Lebed: The Man, His Program and Politi-

cal Prospects in 2000.” Problems of Post-Communism

46:55–63.

Lebed, Alexander. (1997). General Alexander Lebed: My Life

and My Country. Washington, DC: Regnery Pub.

Petrov, Nikolai. (1999). Alexander Lebed in Krasnoyarsk

Krai. Moscow: Carnegie Center.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

LEFORTOVO

Lefortovo is a historic area in the eastern part of

Moscow, on the left bank of the Yauzy River,

named for the Lefortovsky infantry regiment,

commanded by Franc Yakovlevicz Lefort, a com-

rade of Peter the Great, which was quartered there

toward the end of the seventeenth century. In the

1770s and 1780s the soldiers occupied sixteen

wooden houses. Nearby were some slaughter-

houses and a public courtyard, where in 1880 the

Lefortovo military prison was constructed (archi-

tect P. N. Kozlov). At the time it was intended for

low-ranking personnel convicted of minor in-

fringements. St. Nikolai’s Church was built just

above the entrance to the prison. Over the next

hundred years several new buildings were added to

the prison complex.

In tsarist times Lefortovo was under the juris-

diction of the Main Prison Administration of the

Ministry of Justice. After the revolution it became

part of the network of prisons run by the Special

Department of the Cheka. In the 1920s Lefortovo

was under the OGPU (United Main Political Ad-

ministration). In the 1930s, together with the

Lubyanka Internal Prison and the Butyrskoi and

Sukhanovskoi prisons, it was under the GUGB

(Central Administrative Board of State Security) of

the NKVD (People`s Commissioner’s Office for In-

ternal Affairs) of the USSR. Suspects were tortured

and shot in the former church of the prison, and

tractor motors were run to drown out the awful

sounds. With the closing of the Lubyanka Internal

Prison in the 1960s, Lefortovo attained its present

status as the main prison of the state security ap-

paratus. In October 1993, Alexander Rutskoi and

LEFORTOVO

836

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Roman Khasbulatov, the organizers of the abortive

putsch against Boris Yeltsin, were held in the Lefor-

tovo detention isolator (solitary confinement) of the

Ministry of Safety (MB) of the Russian Federation.

In December 1993 and January 1994 the Lefortovo

isolator passed from the jurisdiction of the Min-

istry of Safety to the Ministry of Internal Affairs

(MVD). By the end of 1994 the FSB again created

an investigatory administration, and in April 1997,

after an eight-month struggle between the Min-

istry of Internal Affairs and the FSB, the isolator

was again transferred to FSB jurisdiction.

The three-tier complex of the FSB’s Investiga-

tive Administration, unified with the prison, is lo-

cated adjacent to the Lefortovo isolator. According

to the testimony of former inmates, there are fifty

cells on each floor of the four-story cellblock. As

of 2003 there were about two hundred prisoners

in Lefortovo. The exercise area is located on the roof

of the prison. Most of the cells are about 10 me-

ters square and hold two inmates; there are also

some cells for three, and a few for one. Lefortovo

differs from other Russian detention prisons not

only in its relatively good conditions but also for

its austere regime. The inmates held here have been

arrested on matters that concern the FSB, such as

espionage, serious economic offenses, and terror-

ism, rather than ordinary crimes.

See also: GULAG; LUBYANKA; PRISONS; STATE SECURITY,

ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Krakhmalnikova, Zoya. (1993). Listen, Prison! Lefortovo

Notes: Letters from Exile. Redding, CA: Nikodemos Or-

thodox Publication Society.

G

EORG

W

URZER

LEFT OPPOSITION

Headed by Leon Trotsky, the Left Opposition

(1923–1927) rallied against Bolshevik Party disci-

pline on a wide array of issues. It became one of

the last serious manifestations of intra-Party de-

bate before Josef Stalin consolidated power and si-

lenced all opposition.

Following the illness and death of Vladimir

Lenin, the formation of the Left Opposition cen-

tered on Trotsky and the role he played in the

struggle for Party leadership and the debates over

the future course of the Soviet economy. Through-

out 1923, after three strokes left Lenin incapaci-

tated, Stalin actively strengthened his position

within the Party leadership and moved against sev-

eral oppositionist tendencies. In October that same

year, Trotsky struck back with a searing condem-

nation of the ruling triumvirate (Grigory Zinoviev,

Lev Kamenev, and Stalin), publicly charging them

with “secretarial bureaucratism” and demanding a

restoration of Party democracy.

At the same time, proponents of Trotsky’s the-

ory of permanent revolution, including such lu-

minaries as Yevgeny Preobrazhensky, Grigory

Pyatakov, Timofey Sapronov, and V. V. Osinsky,

coalesced around the Platform of the Forty-Six.

Representing the position of the left, they attrib-

uted the Party’s ills to a progressive division of the

Party into functionaries, chosen from above, and

the rank-and-file Party members, who did not par-

ticipate in Party affairs. Further, they accused the

leadership of making economic mistakes and de-

manded that the dictatorship of the Party be re-

placed by a worker’s democracy.

Formulating a more comprehensive platform,

Trotsky published a pamphlet entitled The New

Course in January 1924. By this time, the Left Op-

position had gained enough public support that the

leadership made some concessions in the form of

the Politburo’s adoption of the New Course Reso-

lution in December. Nonetheless, at the Thirteenth

Party Congress in May 1924, the Left Opposition

was condemned for violating the Party’s ban on

factions and for disrupting Party unity.

The Left Opposition’s economic platform fo-

cused on the goals of rapid industrialization and

the struggle against the New Economic Policy

(NEP). Left Oppositionists, also known as Trot-

skyites because of Trotsky’s central role, argued

that encouraging the growth of private and peas-

ant sectors of the economy under the NEP was

dangerous because it would create an investment

crisis in the state’s industrial sector. Moreover, by

favoring trade and private agriculture, the state

would make itself vulnerable to the economic

power of hostile social classes, such as peasants and

private traders. In 1925, Preobrazhensky, the left’s

leading theoretician, proposed an alternative course

of action with his theory of primitive socialist ac-

cumulation. Arguing that the state should shift re-

sources through price manipulations and other

market mechanisms, he believed that peasant pro-

ducers and consumers should bear the burden of

LEFT OPPOSITION

837

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

capital accumulation for the state’s industrializa-

tion drive. According to his plan, the government

could achieve this end by regulating prices and

taxes.

In a polity where loyalty and opposition were

deemed incompatible, the Left Opposition was

doomed from the start. Following the Thirteenth

Party Congress denunciation, Trotsky renewed his

advocacy of permanent revolution as Stalin pro-

moted his theory of socialism in one country. The

result was Trotsky’s removal from the War Com-

missariat in January 1925 and his expulsion from

the Politburo the following year. At the same time,

Kamenev and Zinoviev broke with Stalin over the

issue of socialism in one country and continuation

of the NEP. In mid-1926, in an attempt to subvert

Stalin’s growing influence, Trotsky joined with

Kamenev and Zinoviev in the Platform of the Thir-

teen, forming the United Opposition.

By 1926, however, it was already too late to

mount a strong challenge to Stalin’s growing

power. Through skillful maneuvering, Stalin had

been able increasingly to secure control over the

party apparatus, eroding what little power base the

oppositionists had. In 1927 Trotsky, Kamenev, and

Zinoviev were removed from the Central Commit-

tee. By the end of that year the trio and all of their

prominent followers, including Preobrazhensky

and Pyatakov, were purged from the Party. The

next year, Trotsky and members of the Left Oppo-

sition were exiled to Siberia and Central Asia. In

February 1929 Trotsky was deported from the

country, thus beginning the odyssey that ended

with his murder by an alleged Soviet agent in Mex-

ico City in 1940. Despite recantations and pledges

of loyalty to Stalin, the remaining so-called Trot-

skyites could never free themselves of the stigma

of their past association with the Left Opposition.

Nearly all of them perished in the purges of the

1930s.

See also: RIGHT OPPOSITION; TROTSKY, LEON DAVID-

OVICH; UNITED OPPOSITION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carr, Edward Hallett, and Davies, R. W. (1971). Foun-

dations of a Planned Economy, 1926–1929, 2 vols.,

New York: Macmillan.

Deutscher, Isaac. (1963). The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky,

1921–1929. New York: Oxford University Press.

Erlich, Alexander. (1960). The Soviet Industrialization De-

bate, 1924–1928. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press.

Graziosi, Andrea. (1991). “‘Building the First System of

State Industry in History’: Piatakov’s VSNKh and

the Crisis of NEP, 1923–1926.” Cahiers du monde

russe et sovietique 32:539–581.

Trotsky, Leon. (1975). The Challenge of the Left Opposi-

tion, 1923–1925. New York: Pathfinder Press.

K

ATE

T

RANSCHEL

LEFT SOCIALIST REVOLUTIONARIES

The Left Socialist Revolutionaries (Left SRs) were an

offshoot of the Socialist Revolutionary (SR) Party,

a party that had arisen in 1900 as an outgrowth

of nineteenth-century Russian populism. Both the

SRs and their later Left SR branch espoused a so-

cialist revolution for Russia carried out by and

based upon the radical intelligentsia, the industrial

workers, and the peasantry. After the outbreak

of World War I in August 1914, some party

leaders in the emigration, such as Yekaterina

Breshko-Breshkovskaya, Andrei A. Argunov, and

Nikolai D. Avksentiev, offered conditional, tempo-

rary support for the tsarist government’s war ef-

forts. Meanwhile, under the guidance of Viktor

Chernov and famous populist leader Mark Natan-

son, the Left SRs or SR–Internationalists, as they

were variously called, insisted that the party main-

tain an internationalist opposition to the world

war. These developments, mirrored along Social

Democrats, caused conflicts within and almost split

the party inside Russia. By mid-1915, the antiwar

forces began to predominate among SR organiza-

tions that were just beginning to recover from po-

lice attacks after the war’s outbreak. Much of the

party’s worker, peasant, soldier, and student cadres

turned toward leftist internationalism, whereas

prowar (defensist) support came primarily from

the party’s intelligentsia. By 1916, many SR (in ef-

fect Left SR) organizations poured out antigovern-

ment and antiwar propaganda, took part in strikes,

and agitated in garrisons and at the fronts. In all

these activities, they cooperated closely with Bol-

sheviks, Left Mensheviks, and anarchists of similar

outlook. This coalition and the mass movements it

spurred wore down the incompetent tsarist state

and overthrew it on March 12 (February 27, O.S.),

1917.

As SR leaders returned to the Russian capital,

they reunified leftist and rightist factions and em-

phasized the party’s multi–class approach. Cher-

nov, who in 1914-1915 had helped form the Left

LEFT SOCIALIST REVOLUTIONARIES

838

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

SR movement, now sided with the party moder-

ates by approving SR participation in the Provi-

sional Government and the Russian military

offensive of June 1917. Until midsummer the

party’s inclusive strategy seemed to work, as huge

recruitments occurred everywhere. The SRs seemed

poised to wield power in revolutionary Russia. Si-

multaneously, leftists such as Natanson, Boris

Kamkov, and Maria Spiridonova, noting the grow-

ing worker-soldier uneasiness with the party’s

policies, began to reshape the leftist movement and

cooperated with other leftist parties such as the Bol-

sheviks and Left Mensheviks. In this respect, they

helped recreate the wartime leftist coalition that had

proved so effective against the tsarist regime. By

late summer and fall, the Left SRs, acting as a de

facto separate party within the SR party and work-

ing at odds with it, were doing as much as the Bol-

sheviks to popularize the idea of soviet and socialist

power. During October–November, they opposed

Bolshevik unilateralism in overthrowing the Provi-

sional Government, instead of which they proposed

a multiparty, democratic version of soviet power.

Even after the October Revolution, the Left SRs

hoped for continued coexistence with other SRs

within a single party, bereft, they hoped, only of

the extreme right wing. When the Fourth Congress

of the SR Party (November 1917) dashed those

hopes by refusing any reconciliation with the left-

ists, the Left SRs responded by convening their own

party congress and officially constituting them-

selves as a separate party. In pursuit of multiparty

soviet power, during December 1917 they reaf-

firmed their block with the communists (the Bol-

sheviks used this term after October 1917) and

entered the Soviet government, taking the com-

missariats of justice, land, and communications

and entering the supreme military council and the

secret police (Cheka). They favored the Constituent

Assembly’s dismissal during January 1918 but

sharply opposed other communist policies. Daily

debates between communist and Left SR leaders

characterized the high councils of government.

When Lenin promulgated the Brest–Litovsk Peace

with Germany in March 1918 against heavy op-

position within the soviets and his own party, the

Left SRs resigned from the government but re-

mained as a force in the soviets and the all–

Russian soviet executive committee.

Having failed to moderate communist policies

by working within the government, the Left SRs

now appealed directly to workers and peasants,

combining radical social policy with democratic

outlooks on the exercise of power. Dismayed by

Leninist policy toward the peasantry, the economic

hardships imposed by the German peace treaty, and

blatant communist falsification of elections to the

Fifth Congress of Soviets during early July 1918,

the Left SR leadership decided to assassinate Count

Mirbach, the German representative in Moscow.

Often misinterpreted as an attempt to seize power,

the successful but politically disastrous assassina-

tion had the goal of breaking the peace treaty. The

Left SRs hoped that this act would garner wide

enough support to counter–balance the commu-

nists’ hold on the organs of power. Regardless,

Lenin managed to placate the Germans and prop-

agate the idea that the Left SRs had attempted an

antisoviet coup d’état. Just as SRs and Mensheviks

had already been hounded from the soviets, now

the Left SRs suffered the same fate and, like them,

entered the anticommunist underground. In re-

sponse, some Left SRs formed separate parties (the

Popular Communists and the Revolutionary Com-

munists) with the goal of continuing certain Left

SR policies in cooperation with the communists,

with whom both groups eventually merged.

Throughout the civil war, the Left SRs charted a

course between the Reds and Whites as staunch

supporters of soviet rather than communist power.

They maintained a surprising degree of activism,

inspiring and often leading workers’ strikes, Red

Army and Navy mutinies, and peasant uprisings.

They helped create the conditions responsible for

the introduction of the 1921 New Economic Pol-

icy, some of whose economic compromises they

opposed. During the early 1920s they succumbed

to the concerted attacks of the secret police. The

Left SRs’ chief merit, their reliance on processes of

direct democracy, turned out to be their downfall

in the contest for power with communist leaders

willing to use repressive methods.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; FEBRUARY REVOLU-

TION; OCTOBER REVOLUTION; SOCIALISM; SOCIALIST

REVOLUTIONARIES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Melancon, Michael. (1990). The Socialist Revolutionaries

and the Russian Anti–War Movement, 1914-1917.

Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Mstislavskii, Sergei. (1988). Five Days That Shook the

World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Radkey, Oliver. (1958). The Agrarian Foes of Bolshevism:

Promise and Default of the Russian Socialist Revolu-

tionaries, February-October 1917. New York: Colum-

bia University Press.

LEFT SOCIALIST REVOLUTIONARIES

839

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Radkey, Oliver. (1963). The Sickle under the Hammer: The

Russian Socialist Revolutionaries in the Early Months

of Soviet Rule. New York: Columbia University Press.

Steinberg, I.N. (1935). Spiridonova: Revolutionary Terror-

ist. London: Methuen.

Steinberg, I.N. (1953). In the Workshop of the Revolution.

New York: Rinehart.

M

ICHAEL

M

ELANCON

LEGAL SYSTEMS

The Russian legal system—the judicial institutions

and laws—has been shaped by many different in-

fluences, domestic as well as foreign. It constitutes

just one of several legal systems at work within

Russia. As befits any large, multiethnic society,

many different legal systems have coexisted in

Russia at various points in history. Prior to the

twentieth century especially, many of the non-

Slavic peoples of the Russian empire as well as Russ-

ian peasants relied on their religious or customary

laws and institutions to regulate important aspects

of life (e.g., family, marriage, property, inheri-

tance).

PRINCIPALITIES AND MUSCOVY

As in Western Europe, the early history of Russian

law is marked by an initial reliance on oral cus-

tomary legal norms giving way in time to written

law codes and judicial institutions heavily influ-

enced by religious sources. The oldest documentary

records of Russian customary law are several

treaties concluded by Kievan Rus in the tenth cen-

tury with Byzantium. These treaties included Russ-

ian principles of criminal law that, like their

counterparts in Western Europe, were heavily re-

liant on a system of vengeance and monetary com-

pensation for harm committed against another.

One interesting feature of Russian customary law

was that women enjoyed a higher, more indepen-

dent status under Russian law than under con-

temporary Byzantine law.

The introduction of Christianity to Kievan Rus

exposed the Russians both to the notion of written

law as well as canon law principles imported from

Byzantium. In the eleventh century, Russian cus-

tomary law was set down in writing comprehen-

sively for the first time in the Russkaya Pravda,

which focused on criminal law and procedure and

incorporated principles of blood feud and monetary

compensation for damages. Later versions of the

Russkaya Pravda included elements of civil and

commercial law, which were heavily drawn from

German and Byzantine sources. Courts under the

Russkaya Pravda consisted of tribunals of the elder

members of the local community, rather than gen-

uine state-sponsored courts. While some scholars

maintain that the Russkaya Pravda was in force

over all of ancient Russia, others argue that its ef-

fect was much more limited to only a few princi-

palities. Where it was enforced, the Russkaia Pravda

remained in effect until the seventeenth century.

During the fifteenth through seventeenth cen-

turies, Russian law was modified to support the

emerging Muscovite autocracy. In particular, the

legal status of the peasants was reduced to serf-

dom. During this same period, several important

written collections of law were adopted dealing

with criminal, civil, administrative, and commer-

cial law and procedure. Under the Sudebnik of 1497,

torture was institutionalized as a normal tool of

criminal investigations. The Ulozhenie of 1649,

which remained the principal basis for much of

Russian law for two centuries, consisted of 967 ar-

ticles covering most areas of the law. The criminal

law sections of the Ulozhenie were noted for intro-

ducing more severe punishments into Russian law

(burying alive, burning, mutilation). These docu-

ments were not well-organized, systematized codes

of law, but were merely collections of existing laws,

decrees, and administrative regulations.

RUSSIAN EMPIRE

Beginning with Peter the Great, several tsars at-

tempted to rationalize the Russian legal system by

introducing Western innovations and bolstering

their autocratic rule by improving the efficiency

with which Russian courts went about their busi-

ness. Toward this end, Peter established the Senate

to supervise the courts and punish corrupt or in-

competent judges as well as the office of the procu-

rator-general, which was established in 1722 to

oversee the Senate and to supervise the enforcement

of laws and decrees. The office of the Russian procu-

rator-general continues to this day.

One of the most intractable problems facing

Russian legal reformers was the morass of unor-

ganized and undifferentiated laws and decrees in ef-

fect. The Russian legal system sat on a foundation

of out-of-date or half-forgotten laws, decrees, and

procedures, and judges and government officials

were hard-pressed to know which laws were in ef-

fect at any given moment. In the nineteenth cen-

LEGAL SYSTEMS

840

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tury, Russian specialists under the direction of M.

M. Speransky attempted to rationalize this mater-

ial by collecting and distilling it into a fifteen-vol-

ume digest, the Svod zakonov rossiiskoi imperii,

published in 1832.

The most significant tsarist-era legal reforms

were adopted in 1864, when a modern, Western-

style judicial system was introduced in the after-

math of the emancipation of the serfs. The new

judicial system introduced professional judges and

lawyers, trial by jury, modern evidentiary rules,

justices of the peace, and modern criminal investi-

gation procedures drawn from Continental mod-

els. Reaction to these liberal judicial reforms set in

during the reign of Alexander II after the acquittal

of several famous dissidents, including the assas-

sin Vera Zasulich, and the independence of the

courts in political cases was significantly eroded af-

ter the assassination of Alexander II in 1881. De-

spite this reaction, the institutions established by

the Judicial Reforms of 1864 remained in effect un-

til 1917.

SOVIET REGIME

A decree adopted in late 1917, On the Court, abol-

ished the tsarist judicial institutions, including the

courts, examining magistrates, and bar association.

However, during the first years following the

Bolshevik Revolution, legal nihilists such as E.

Pashukanis, who advocated the rapid withering

away of the courts and other state institutions,

contended with more pragmatic leaders who envi-

sioned the legal system as an important asset in as-

serting and defending Soviet state power. The latter

group prevailed. Vladimir Lenin, during the New

Economic Policy, sought to re-establish laws,

courts, legal profession, and a new concept of so-

cialist legality to provide more stability in society

and central authority for the Party hierarchy. The

debate between the legal nihilists and their oppo-

nents was definitively resolved by Josef Stalin in

the early 1930s. As Stalin asserted control over the

Party and initiated industrialization and collec-

tivization, he also asserted the importance of sta-

bilizing the legal system. This process culminated

in the 1936 constitution, which strengthened law

LEGAL SYSTEMS

841

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

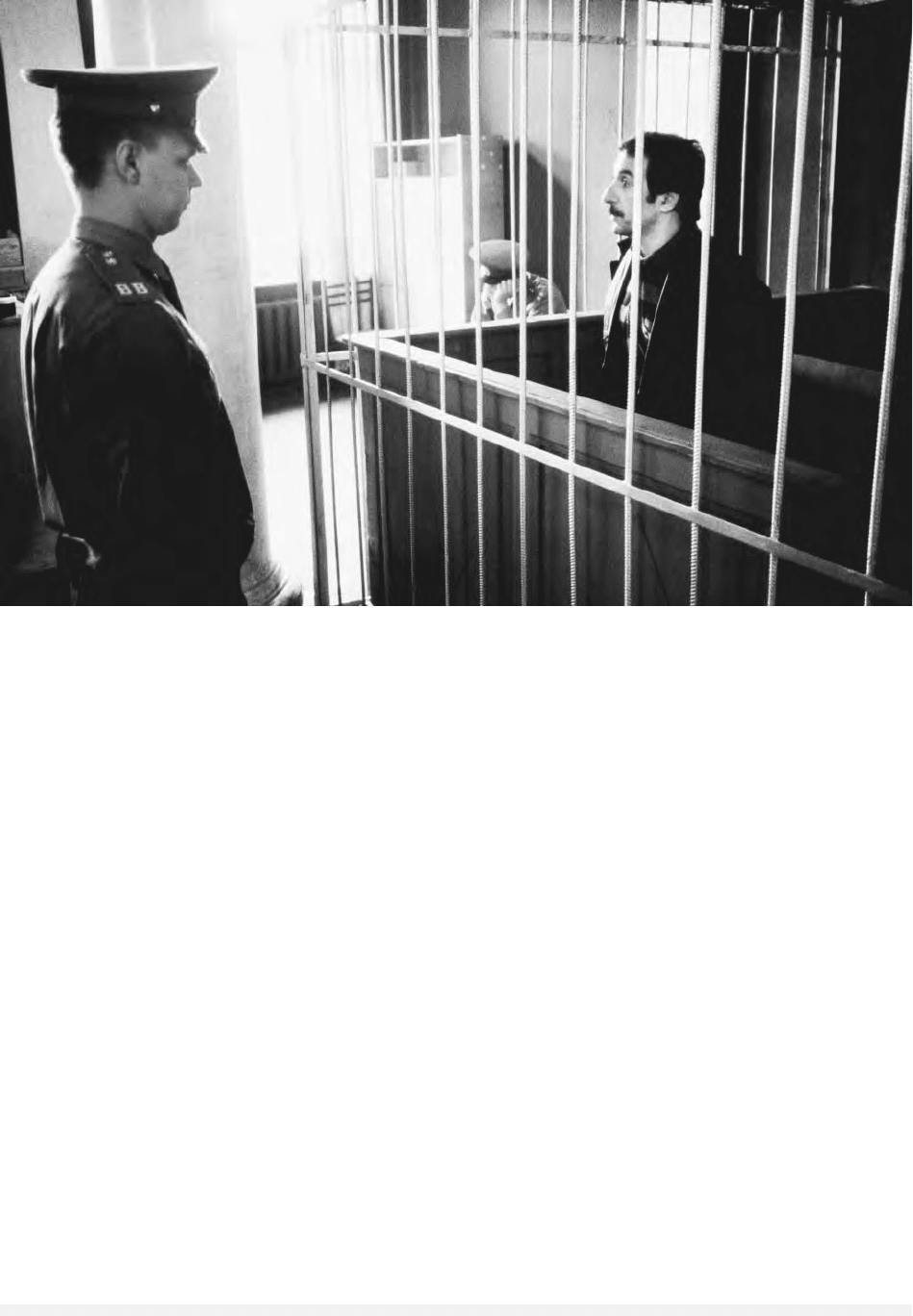

A guard stands by the defendant in a 1992 murder trial in St. Petersburg. The accused is kept in a cage inside the courtroom.

© S

TEVE

R

AYMER

/CORBIS

and legal institutions, especially administrative

law, civil, family, and criminal law.

The broad outlines of the legal system estab-

lished by Stalin in the 1930s remained in effect un-

til the late 1980s. Reforms introduced by Mikhail

Gorbachev in the late 1980s, however, made sig-

nificant changes in the Soviet judicial system. Gor-

bachev sponsored a lengthy public discussion of

how to introduce pravovoe gosudarstvo (law-based

state) in the USSR and introduced legislation to im-

prove the independence and authority of judges and

to establish the Committee for Constitutional Su-

pervision, a constitutional court.

POST-SOVIET REFORMS

In the years since the collapse of the Soviet Union,

Russia has adopted a wide array of legislation

remaking many aspects of its judicial system,

drawing heavily on foreign models. Most of the

legislation that has been adopted was foreshadowed

in the 1993 constitution and includes new laws and

procedure codes for the ordinary courts and the ar-

bitrazh courts, which are courts devoted to mat-

ters arising from business and commerce, new civil

and criminal codes, and a new land code, finally

adopted in 2001.

See also: COOPERATIVES, LAW ON; FAMILY LAW OF 1936;

FUNDAMENTAL LAWS OF 1906; GOVERNING SENATE;

PROCURACY; RUSSIAN JUSTICE; STATE ENTERPRISE,

LAW OF THE; SUCCESSION, LAW ON; SUDEBNIK OF 1497

M

ICHAEL

N

EWCITY

LEGISLATIVE COMMISSION OF 1767–1768

In December 1766, Catherine II called upon the free

“estates” (nobles, townspeople, state peasants, Cos-

sacks) and central government offices to select

deputies to attend a commission to participate in the

preparation of a new code of laws. The purpose of

the commission was therefore consultative; it was

not intended to be a parliament in the modern sense.

The Legislative Commission opened in Moscow in

July 1767, then moved to St. Petersburg in Febru-

ary 1768. Following the outbreak of the Russo-

Turkish War in January 1769, it was prorogued

and never recalled. The selection of deputies was a

haphazard affair. The social composition of the as-

sembly was: nobles, 205; merchants, 167; odnod-

vortsy (descendants of petty servicemen on the

southern frontiers), 42; state peasants, 29; Cossacks,

44; industrialists, 7; chancery clerks, 19; tribesmen,

54. Deputies brought instructions, or nakazy, from

the bodies that selected them. Catherine’s Nakaz

(Great Instruction) was read at the opening sessions

and provided a basis for some of the discussion that

followed. The commission met in 203 sessions and

discussed existing laws on the nobility, on the Baltic

nobility, on the merchant estate, and on justice and

judicial procedure. No decisions were made by the

commission on these matters, and no code of laws

was produced. The Legislative Commission was nev-

ertheless significant: It gave Catherine an important

source of information and insight into concerns and

attitudes of different social groups, through both the

nakazy and the discussions which took place, in-

cluding a discussion on serfdom; it provided an op-

portunity for the discussion and dissemination of

the ideas in Catherine’s Nakaz; it led to the estab-

lishment of several subcommittees, which continued

to meet after the prorogation of the commission,

and which produced draft laws that Catherine uti-

lized for subsequent legislation.

See also: CATHERINE II; INSTRUCTION TO THE LEGISLATIVE

COMMISSION OF CATHERINE II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dukes, Paul. (1967.) Catherine the Great and the Russian

Nobility. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Madariaga, Isabel de. (1981). Russia in the Age of Cather-

ine the Great. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

J

ANET

H

ARTLEY

LEICHOUDES, IOANNIKIOS

AND SOPHRONIOS

Greek hieromonks, Ioannikios (secular name:

Ioannes, 1633–1717) and Sophronios (secular

name: Spyridon, 1652–1730).

The two brothers Leichoudes were born on the

Greek island of Kephallenia. They studied philoso-

phy and theology in Greek-run schools in Venice.

Sophronios received a doctorate in philosophy from

the University of Padua in 1670. Between 1670 and

1683, they worked as preachers and teachers in

Kephallenia and in Greek communities of the Ot-

toman Empire. In 1683 they reached Constantino-

ple, where they preached in the Patriarchal court.

Following a Russian request for teachers, they ar-

LEGISLATIVE COMMISSION OF 1767–1768

842

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY