Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

in the so-called April Theses, enunciated immedi-

ately on his return to Russia (April 16–17, 1917),

that the party should not support the provisional

government. By accident or design, this was the

key to Bolshevik success. As other parties were

sucked into supporting the provisional govern-

ment, they each lost public support. After the Ko-

rnilov Affair, when the commander-in-chief, Lavr

Kornilov, appeared to be spearheading a counter-

revolution in August and September of 1917, it was

the Bolsheviks who were the main beneficiaries be-

cause they were not tainted by association with the

discredited provisional government which, popular

opinion believed, was associated with Kornilov’s

apparent coup. Even so, it took immense personal

effort by Lenin to persuade his party to seize their

opportunity. Contrary to much received opinion

and Bolshevik myth, the October Revolution was

not carefully planned but, rather, improvised. Lenin

was in still in hiding in Finland following pro-

scription of the party after the July Days, when

armed groups of sailors had failed in an attempt to

overthrow the provisional government and the au-

thorities took advantage of the situation to move

against the Bolsheviks. He had been vague about

details of the proposed revolution throughout the

crucial weeks leading up to it, suggesting, at dif-

ferent moments, that it might begin in Moscow,

Petrograd, Kronstadt, the Baltic Fleet, or even

Helsinki. Only his own emergence from hiding, on

October 23rd and 29th and during the seizure of

power itself (November 6–7 O.S.) finally brought

his party in line behind his policy. The provisional

government was overthrown, and Lenin became

Chairman of the Soviet of People’s Commissars, a

post he held until his death.

October was far from the end of the story. The

tragic complexity of the seizure of power soon be-

came apparent. The masses wanted what the slo-

gans of October proclaimed: soviet power, peace,

land, bread, and a constituent assembly. Lenin,

however, wanted nothing less than the socialist

transformation not only of Russia but of the world.

Conflict was inevitable. By early 1918, autonomous

workers and peasants organizations, including

their political parties and the soviets themselves,

were losing all authority. Ironically, at this mo-

ment one of Lenin’s most libertarian, almost anar-

chist, writings, State and Revolution, written while

he was in Finland, was published. In it he praised

direct democracy and argued that capitalism had

so organized and routinized the economy that it

resembled the workings of the German post office.

As a result, he wrote, the transition to socialism

would be relatively straightforward.

However, reality was to prove less tractable.

Lenin began to talk of “iron discipline” as an es-

sential for future progress, and in The Immediate

Tasks of the Soviet Government (March–April 1918)

proclaimed the concept of productionism—the

maximization of economic output as the prelimi-

nary to building socialism—to be a main goal of

the Soviet government. Productionism was an ide-

ological response to Russia’s Marxist paradox, a

worker revolution in a “backward” peasant coun-

try. Indeed, the weakness of the proletariat was

vastly accentuated in the first years of Soviet

power, as industry collapsed and major cities lost

up to two-thirds of their population through dis-

ease, hunger, and flight to the countryside.

Like the events of October, early Soviet policy

was also improvised, though within the confines

of Bolshevik ideology. Lenin presided over the na-

tionalization of all major economic institutions and

enterprises in a crude attempt to replace the mar-

ket with allocation of key products. He also over-

saw the emergence of a new Red Army; the setting

up of a new state structure based on Bolshevik-led

soviets; and a system of direct appropriation of

grain from peasants, as well as the revolutionary

transformation of the country. This last entailed

the taking over of land by peasants and the disap-

pearance from Soviet territory of the old elites, in-

cluding the aristocracy, army officers, capitalists,

and bankers. To the chaos of the early months of

revolution was added extensive protest within the

party from its left wing, which saw production-

ism and iron discipline as a betrayal of the liber-

tarian principles of 1917. The survival of Lenin’s

government looked improbable. However, the out-

break of major civil war in July 1918 gave it a new

lease of life, forcing people to choose between im-

perfect revolution, represented by the Bolsheviks,

or out-and-out counter-revolution, represented by

the opposition (called the Whites). Most opted for

the former but, once the Whites were defeated in

1920, tensions re-emerged and a series of uprisings

against the Soviet government took place.

THE FINAL YEARS (1922–1924)

Lenin’s solution to the post–civil war crisis was his

last major intervention in politics, because his

health began to fail from 1922 onwards, exacer-

bated by the bullet wounds left after an assassina-

tion attempt in August 1918. The key problem in

the crisis was peasant disaffection with the grain

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

853

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

appropriation system. Lenin replaced requisitioning

by a tax-in-kind, which in turn necessitated the

partial restoration of market relations. Nonetheless,

the state retained the commanding heights of the

economy, including large factories, transport, tax-

ation, and foreign trade. The result was known as

the New Economic Policy. It was Lenin’s third at-

tempt at a form of transition. The first, outlined in

the April Theses, was based on “Soviet supervision

of production and distribution,” a system that had

collapsed within the first months of Bolshevik

power. The second, later called war communism,

was based on iron discipline, state control of the

economy, and grain requisitioning. Lenin believed

his third solution was the correct one, arrived at

through the test of reality. It was accompanied by

intellectual and political repression and the impo-

sition of a one-party state on the grounds that con-

cession to bourgeois economic interests gave the

revolution’s enemies greater power that had to be

counteracted by greater political and intellectual

control by the party. Lenin remained enthusiastic

about the NEP, and did not live to see the compli-

cations that ensued in the mid-1920s.

In his last writings, produced during his bouts

of convalescence from a series of increasingly se-

vere strokes beginning in May 1922, Lenin laid

down a number of guidelines for his successors.

These included a cultural revolution to modernize

the peasantry (On Co-operation, January 1923) and

a modest reorganization of the bureaucracy to get

it under control (“Better Fewer but Better,” March

1923, his last article). In his “Testament” (Letter to

the Congress, December 1922), Lenin argued that the

party should not, in future, antagonize the peas-

antry. Most controversially, however, he summed

up the candidates for succession without clearly

supporting any one of them. His criticism of

Stalin—that he had accumulated much power and

Lenin was not confident that he would use it

wisely—was strengthened in January of 1923, af-

ter Stalin argued with Krupskaya. Lenin called for

Stalin to be removed as General Secretary, a post

to which Lenin had only promoted him in 1922.

There was no suggestion that Stalin should be re-

moved from the Politburo or Central Committee.

In any case, Lenin was too ill to follow through on

his suggestions, thereby opening up vast specula-

tion as to whether he might have prevented Stalin

from coming to power had he lived longer.

Lenin’s last year was spent at his country res-

idence near Moscow. In the company of Nadezhda

Krupskaya and his sisters, he lived out his last

months being read to and taken on walks in his

wheelchair. In October 1923 he even had enough

energy to return for a last look around his Krem-

lin office, despite the guard’s initial refusal to ad-

mit him because he did not have an up-to-date pass.

However, his health continued to deteriorate, and

he died on the evening of January 21, 1924.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; FEBRUARY REVOLUTION; JULY DAYS

OF 1917; KORNILOV AFFAIR; KRUPSKAYA, NADEZHDA

KONSTANTINOVNA; LENIN’S TESTAMENT; LENIN’S

TOMB; NEW ECONOMIC POLICY; OCTOBER MANIFESTO;

OCTOBER REVOLUTION; POPULISM; WAR COMMUNISM;

WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carrère d’Encausse, Hélène. (1982). Lenin: Revolution and

Power. London: Longman.

Claudin-Urondo, Carmen. (1977). Lenin and the Cultural

Revolution. Sussex and Totowa, New Jersey: Har-

vester Press/Humanities Press.

Harding, Neil. (1981). Lenin’s Political Thought. 2 vols.

London: Macmillan.

Harding, Neil. (1991). Leninism. London: Macmillan.

Krupskaya, Nadezhda. (1970). Memories of Lenin. Lon-

don: Panther.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilich (1960-1980) Collected Works. 47

vols. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilich. (1967). Selected Works. 3 vols.

Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Lewin, Moshe. (1968). Lenin’s Last Struggle. New York:

Random House.

Pipes, Richard. (1996). The Unknown Lenin. New Haven

and London: Yale University Press.

Read, Christopher. (2003). Lenin: A Revolutionary Life.

London: Routledge.

Service, Robert. (1994). Lenin: A Political Life. 3 vols. Lon-

don: Macmillan.

Service, Robert. (2000). Lenin: a Biography. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Shub, David. (1966). Lenin. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Ulam, Adam. (1969). Lenin and the Bolsheviks. London:

Fontana/Collins.

Volkogonov, Dmitril. (1995). Lenin: Life and Legacy, ed.

Harold Shukman. London: Harper Collins.

Weber, Gerda, and Weber, Hermann. (1980). Lenin: Life

and Work. London: Macmillan.

White, James. (2000). Lenin: The Practice and Theory of

Revolution. London: Palgrave.

Williams, Beryl. (2000). Lenin. London: Harlow Long-

man.

C

HRISTOPHER

R

EAD

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

854

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

LEONTIEV, KONSTANTIN NIKOLAYEVICH

(1831–1891), social philosopher, literary critic, and

novelist.

Konstantin Nikolayevich Leontiev occupied a

unique place in the history of nineteenth-century

Russian social thought. He was a nationalist and a

reactionary whose position differed in significant

respects from the thinking of both the Slavophiles

and the Pan-Slavists. Some historians refer to Leon-

tiev’s social philosophy as Byzantinism.

Leontiev led a varied life, in which he was in

turn a surgeon, a diplomat, an editor, a novelist,

and a monk. He was raised on a small family es-

tate in the province of Kaluga. After studying

medicine at the University of Moscow, he served

as a military surgeon during the Crimean War.

Following his military service, he returned to

Moscow to continue the practice of medicine and

to write a series of novels that enjoyed little suc-

cess. He married a young, illiterate Greek woman

in 1861, but continued to engage in a series of

love affairs. His wife gradually descended into

madness.

In 1863 Leontiev entered the Russian diplomatic

service, which led to his assignment to posts in the

Balkans and Greece. While serving in that region,

he developed an admiration for Byzantine Chris-

tianity, which was to remain a dominant theme in

his thinking. He was irresistibly attracted to the

Byzantine monasticism that he observed during a

stay at Mount Athos in 1871 and 1872. Leontiev

arrived at the conviction that aesthetic beauty, not

happiness, was the supreme value in life. He re-

jected all humanitarianism and optimism; the

notion of human kindness as the essence of Chris-

tianity’s social teaching was utterly alien to him.

His stance was anomalous in that he lacked strong

personal religious faith, yet advocated strict adher-

ence to Eastern Orthodox religion. He believed that

the best of Russian culture was rooted in the

Orthodox and autocratic heritage of Byzantium,

and not the Slavic heritage that Russia shared with

Eastern Europeans. He thought that the nations of

the Balkans were determined to imitate the bour-

geois West. He hoped that despotism and obscu-

rantism could save Russia from the adoption of

Western liberalism and constitutionalism, and

could give Russia and the Orthodox Christians of

the Balkans the opportunity to unite on the

basis of their common traditions, drawn from the

Byzantine legacy.

Leontiev accepted Nikolai Danilevsky’s concep-

tion that each civilization develops like an organ-

ism, and argued that each civilization necessarily

passes through three phases of development, from

an initial phase of primary simplicity to a second

phase, a golden era of growth and complexity, fol-

lowed at last by “secondary simplification,” with

decay and disintegration. He despised the rational-

ism, democratization, and egalitarianism of the

West of his day, which he saw as a civilization fully

in the phase of decline, as evident in the domina-

tion of the bourgeoisie, whom he held in contempt

for its crassness and mediocrity. He thought it de-

sirable to delay the growth of similar tendencies in

Russia, but he concluded, with regret, that Russia’s

final phase of dissolution was inevitable, and saw

some signs that it had already begun.

Leontiev did not hesitate to endorse harshly re-

pressive, authoritarian rule for Russia in order to

stave off the influence of the West and slow the de-

cline as long as possible. He saw Tsarist autocracy

and Orthodoxy as the powerful forces protecting

tradition in Russian society from the dangerous

tendencies toward leveling and anarchy. He glori-

fied extreme social inequality as characteristic of a

civilization’s phase of flourishing complexity. Un-

like the Slavophiles, Leontiev had little admiration

for the Russian peasants, who in his view inclined

toward dishonesty, drunkenness, and cruelty, and

he repudiated the heritage of the reforms adopted

by Alexander II. Toward the end of his life, he be-

came increasingly pessimistic about the possibility

of preserving autocracy and aristocracy in Russia.

After leaving the diplomatic service, Leontiev

suffered from constant financial stringency, despite

finding a position as an assistant editor of a provin-

cial newspaper. His stories about life in Greece did

not find a wide audience, although late in his life

he did attract a small circle of devoted admirers. In

1891 he took monastic vows and assumed the

name of Clement. He died in the Trinity Monastery

near Moscow in the same year.

Leontiev was one of the most gifted literary

critics of his time, though he was not widely ap-

preciated as a novelist. In Against the Current: Se-

lections from the Novels, Essays, Notes and Letters of

Konstantin Leontiev (1969), George Ivask says that

in Leontiev’s long novels, “his narration is often

capricious, elliptic, impressionistic, and full of

lyrical digression depicting the vague moods of

his superheroes, who express his own narcissistic

ego.” After Leontiev’s death Vladimir Soloviev

contributed to the recognition of Leontiev’s erratic

LEONTIEV, KONSTANTIN NIKOLAYEVICH

855

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

brilliance, stimulating a revival of interest in Leon-

tiev in the early twentieth century.

See also: BYZANTIUM, INFLUENCE OF; DANILEVSKY, NIKO-

LAI; NATIONALISM IN THE ARTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ivask, George, ed. (1969). Against the Current: Selections

from the Novels, Essays, Notes and Letters of Konstan-

tin Leontiev. New York: Weybright and Talley.

Roberts, Spencer, ed. and tr. (1968). Essays in Russian Lit-

erature: The Conservative View: Leontiev, Rozanov,

Shestov. Athens: Ohio University Press.

Thaden, Edward C. (1964). Conservative Nationalism in

Nineteenth-Century Russia. Seattle: University of

Washington Press.

A

LFRED

B. E

VANS

J

R

.

LERMONTOV, MIKHAIL YURIEVICH

(1814–1841), leading nineteenth-century Russian

poet and prose writer.

Mikhail Yurievich Lermontov became one of

Russia’s most prominent literary figures. Based on

the quality and evolution of his writing, some be-

lieve that if he had lived longer he would have sur-

passed the greatness of Alexander Pushkin.

Lermontov’s reputation is rooted equally in his po-

etry and prose. Fame came to him in 1834 when

he wrote Death of a Poet, in which he accuses the

Imperial Court of complicity in Pushkin’s death in

a duel.

The evolution of Lermontov’s poetry reflected

a change in emphasis from the personal to wider

social and political issues. The Novice (1833) is

known for its tight structure and elegant language.

The Demon (1829–1839) became his most popular

poem. Taking place in the Caucasus, it describes the

love of a fallen angel for a mere mortal. The Cir-

cassian Boy (1833) reflects his strong scepticism in

regard to religion and admiration of premodern life.

The Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov (1837) is his

greatest poem set in Russia. His best-known play

is The Masquerade (1837), a stinging commentary

on St. Petersburg high society.

Lermontov is considered to be the founder of

the Russian realistic psychological novel, further

developed by Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Leo Tolstoy.

A Hero of Our Time, which is partly autobiograph-

ical, is his greatest work in this genre. The main

character, Pechorin, is an example of a disenchanted

and superfluous man, and his story provides a bit-

ter critique of Russian society. In this novel Ler-

montov masterfully and realistically described the

landscape of the Caucasus, the everyday life of the

various tribes there, and a wide range of charac-

ters.

Lermontov was killed in a duel with a former

classmate in 1841.

See also: GOLDEN AGE OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE; PUSHKIN,

ALEXANDER SERGEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Garrard, John. (1982). Mikhail Lermontov. Boston:

Twayne.

Kelly, Laurence. (2003). Tragedy in the Caucasus. London:

Tauris.

Z

HAND

P. S

HAKIBI

LESKOV, NIKOLAI SEMENOVICH

(1831–1895), prose writer with an unmatched

grasp of the Russian popular mentality; supreme

master of nonstandard language whose stories and

novels often contrast societal brutality against the

decency of “righteous men” (pravedniki).

Nikolai Semenovich Leskov spent his youth in

part on his father’s estate and in part in the town

of Orel, interacting with a motley cross–section of

provincial Russia’s population. Although lacking a

completed formal education, he later boasted pro-

fessional experiences ranging from criminal inves-

tigator to army recruiter and sales representative.

His first short stories appeared in 1862.

From the beginning, Leskov’s prose conveyed

deep compassion for the underdog. Aesthetically,

he brought the narrative tool of skaz—relating a

story in colorful, quasi-oral language marked as

that of a personal narrator—to a new degree of per-

fection. Among his best works are the novellas Ledi

Makbet Mtsenskogo uyezda (Lady Macbeth of Mt-

sensk, 1865) and Zapechetlenny angel (The Sealed An-

gel, 1873); the former is a gritty tale of raw

passions leading to cold–blooded murders, includ-

ing infanticide, while the latter is the story

of errant icon painters who encounter a miracle.

Soboryane (Cathedral Folk, 1867-1872), a master-

LERMONTOV, MIKHAIL YURIEVICH

856

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ful novel-chronicle, depicts the Russian clergy in a

respectful manner uncommon for its time; how-

ever, a subsequent spiritual crisis caused Leskov’s

ultimate break with the Orthodox Church. His

fairytale “Levsha” (The Lefthander, 1881) became

an instant popular classic, praising the rich talents

of Russian rank-and-file folk while bemoaning

their pathetic lot at the hands of an indifferent rul-

ing class.

Leskov’s unique, first-hand knowledge of Russ-

ian reality, in combination with uncompromising

ethical standards, alienated him from both the lib-

eral and the conservative mainstream. Throughout

his career, he opposed nihilism and remained a

“gradualist,” insisting that Russia needed steady

evolution rather than an immediate revolution.

Leo Tolstoy aptly called Leskov “the first Russ-

ian idealist of a Christian type.”

See also: SKAZ

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lantz, Kenneth. (1979). Nikolay Leskov. Boston: Twayne.

McLean, Hugh. (1977). Nikolai Leskov: The Man and His

Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

P

ETER

R

OLLBERG

LESNAYA, BATTLE OF

The battle of Lesnaya, fought on October 9, 1708,

between the Russian army of Peter the Great and

a Swedish column under General Adam Ludvig

Lewenhaupt, played an important role in the cam-

paign of that year through its weakening of the

Swedish army. Russia’s aim was to resist the at-

tempt of Charles XII, King of Sweden, to invade

Russia. Charles marched through Poland, reaching

Grodno (now western Belarus) by January 1708,

and resumed the march eastward toward Moscow

the following June. Peter’s army retreated before

him, laying waste the land and offering occasional

resistance. At the Russian-Polish border, Charles re-

alized that he could go no further east, as he was

running out of supplies, so he turned south toward

the Ukraine. At the same time, General Lewenhaupt

was moving southeast from Riga to join his king

with 12,500 men, sixteen guns, and several thou-

sand carts filled with supplies for the Swedish

army. As Lewenhaupt approached the village of

Lesnaya, on the small river Lesyanka southeast of

Mogilev (now southeast Belarus), Peter brought up

a flying corps of 5,000 infantry and 7,000 dra-

goons. Peter divided his forces into two columns,

one commanded by himself, the other by his fa-

vorite, Alexander Menshikov. In a fortified camp

made of the wagons, Lewenhaupt defended himself

from noon on, until the Russian general Reinhold

Bauer came up with another 5,000 dragoons.

Around 7:00

P

.

M

. the fighting stopped, and Lewen-

haupt retreated south toward the main Swedish

army, losing half his force and most of the sup-

plies. Peter estimated the Russian losses at 1,111

killed and 2,856 wounded. The battle played an im-

portant role in sapping the strength of the Swedish

army and provided Russia with an important psy-

chological victory as well. To the end of his life Pe-

ter celebrated the day with major festivities at

court.

See also: GREAT NORTHERN WAR; PETER I

P

AUL

A. B

USHKOVITCH

LEZGINS

The Lezgins are an ethnic group of which half re-

sides in the Dagestani Republic. According to the

1989 census they numbered 240,000 within that

republic, a little more than 11 percent of the pop-

ulation. All told, some 466,006 Lezgins lived in the

Soviet Union, with most of the rest residing in

Azerbaijan. Of the total, 91 percent regarded Lez-

gin as their native language and 53 percent con-

sidered themselves to be fluent in Russian as a

second language. Within Dagestan the Lezgins are

concentrated mainly in the south in the moun-

tainous part of the republic.

The Lezgin language is a member of the Lez-

gin group of the Northeast Caucasian languages.

In Soviet times they were gathered in the larger cat-

egory of the Ibero-Caucasian family of languages.

The languages within this family, while geo-

graphically close together, are not closely related

outside of its four major groupings. This catego-

rization has become understood more as a part of

the Soviet ideology of druzhba narodov (friendship

of peoples). The other Lezgin languages are spoken

in Azerbaijan and Dagestan. They are generally

quite small groups, and the term “Lezgin” as an

ethnic category has sometimes served to cover the

entire group. Ethnic self-identity, calculated with

language and religion, has been a fluid concept.

LEZGINS

857

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The Lezgin language since 1937 has been writ-

ten in a modified Cyrillic alphabet. Following the

pattern of other non-Slavic languages in the Soviet

Union, it had a Latin alphabet from 1928 to 1937.

Before that it would have been written in an Ara-

bic script. A modest number of books have been

published in the Lezgin language. From 1984 to

1985, for example, fifty titles were published. This

compares favorably with other non-jurisdictional

ethnic groups, such as their fellow Dagistanis, the

Avars, but less so with some nationalities that pos-

sessed some level of ethnic jurisdiction, such as the

Abkhazians.

The Lezgins long gained a reputation as moun-

tain raiders among people to their south, particu-

larly the Georgians. Again, precision of identity was

not necessarily a phenomenon in naming raiders

as Lezgins. The Lezgins and the Lezgin languages

were likely a part of the diverse linguistic compo-

sition of the Caucasian Kingdom of Albania. Much

has been said of Udi in this context.

In the post-Soviet world the Lezgins have been

involved in ethnic conflict in both Azerbaijan and

Dagestan. They form a distinct minority in the for-

mer country and experience difficulty in the con-

text of this new nation’s attempt to define its own

national being. In Dagestan the Lezgins, located in

the mountains and constituting only 15 percent of

the population, find themselves generally alienated

from the centers of power. They are also in con-

flict with some of the groups that live more closely

to them.

See also: DAGESTAN; ETHNOGRAPHY, RUSSIAN AND SO-

VIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALI-

TIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Karny, Yo’av. (2000). Highlanders: a Journey to the Cau-

casus in Quest of Memory. New York: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux.

P

AUL

C

REGO

LIBERAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY

The Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR;

known as the LDPSU during the last months of the

Soviet period) was created in the spring of 1990,

with active participation of the authorities and spe-

cial services, as a controllable alternative to the

growing democratic movement. In the 1991 pres-

idential elections, the liberal democratic leader, the

political clown Vladimir Zhirinovsky, won a sur-

prising 6.2 million votes (7.8%) and took third place

after victorious Boris Yeltsin and the main Com-

munist candidate Nikolai Ryzhkov. In the 1993

Duma elections, the victories of the LDPR became

a sensation; Zhirinovsky alone, capitalizing on sen-

timents of protest, secured 12.3 million votes

(22.9%). From there the LDPR was able to advance

five candidates in single-mandate districts. Such re-

sounding success—both on the party list and in the

districts—would not befall the LDPR again, al-

though in 1994 and 1995 Zhirinovsky stirred up

considerable energy for party formation in the

provinces. In the 1995 elections, the LDPR regis-

tered candidates in 187 districts (more than the

Communist Party of the Russian Federation, or

KPRF) but received only one mandate and half its

previous vote: 7.7 million votes (11.2%, second to

the KPRF). In the 1996 presidential elections, Zhiri-

novsky received 4.3 million votes (5.7%, fifth

place). The LDPR held approximately fifty seats in

the Duma from 1996 to 1999 which helped repay,

with interest, the resources invested earlier in the

party’s publicity since, with the domination of the

left in the Duma, these votes were able to tip the

scales in favor of government initiatives. The LDPR

turned into an extremely profitable political busi-

ness project.

In the 1999 elections, the Central Electoral

Commission played a cruel joke on the Liberal De-

mocrats. The LDPR list, consisting of a large

number of commercial positions, filled by quasi-

criminal businessmen, was not registered. On the

very eve of the elections, when Zhirinovsky, hur-

riedly assembling another list and registering as the

“Zhirinovsky Bloc,” launched the advertising cam-

paign “The Zhirinovsky Bloc Is the LDPR,” the Cen-

tral Electoral Commission registered the LDPR, but

without Zhirinovsky. The Liberal Democrats were

saved from this fatal split (LDPR without Zhiri-

novsky as a rival of the Zhirinovsky Bloc) only by

the intervention of the Presidium of the Supreme

Court. In the 1999 elections, the Zhirinovsky Bloc

received 6 percent of the vote and finished fifth;

half a year later, in the 2000 presidential elections,

Zhirinovsky himself finished fourth with 2.7 per-

cent. The LDPR fraction in the Duma from 2000 to

2003 was the smallest; it began with 17 delegates

and ended with 13. It was headed by Zhirinovsky’s

son Igor Lebedev, as the party’s head had become

vice-speaker of the Duma.

LIBERAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY

858

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Actively exploiting the nostalgia for national

greatness (and for the USSR with its powerful army

and special services, but without “Party nomen-

klatura”), “enlightened nationalism,” and anti-

Western sentiments; castigating the “radical

reformers” and denouncing efforts at breaking the

country both from without and within, the LDPR

enjoys significant support from surviving groups

and strata that do not share the communist ideol-

ogy. The populist brightness, spiritedness, and

outstanding political and acting abilities of Zhiri-

novsky play an important role, bringing him into

sharp contrast with ordinary Russian politicians.

The LDRP has especially strong support among the

military and those Russian citizens who lived in

Russia’s national republics and SNG (Union of In-

dependent States) countries among residents of bor-

dering nations. The LDPR had its greatest success

in regional elections from 1996 to 1998, when its

candidates won as governor in Pskov oblast, mayor

in the capital Tuva, parliament in Krasnodar Krai,

and the Novosibirsk city assembly; a LDPR candi-

date came close to victory in the presidential elec-

tions in the Mari Republic as well. The LDPR results

in the 1999–2002 term were significantly weaker,

but with the expansion of NATO, the war in Iraq,

and so forth, the LDPR ratings rose again. At its

reregistration in April 2002, the LDPR declared

nineteen thousand members and fifty-five regional

branches.

See also: CONSTITUTION OF 1993; ZHIRINOVSKY, VLADIMIR

VOLFOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

McFaul, Michael, and Markov, Sergei. (1993). The Trou-

bled Birth of Russian Democracy: Parties, Personalities,

and Programs. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution

Press.

McFaul, Michael and Petrov, Nikolai, eds. (1995). Pre-

viewing Russia’s 1995 Parliamentary Elections. Wash-

ington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International

Peace.

McFaul, Michael; Petrov, Nikolai; and Ryabov, Andrei,

eds. (1999). Primer on Russia’s 1999 Duma Elections.

Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for Interna-

tional Peace.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism Against Democ-

racy. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

N

IKOLAI

P

ETROV

LIBERALISM

Any discussion of Russian liberalism must start with

a general definition of the term. The online Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy emphasizes liberals’ advo-

cacy of individual liberty and freedom from unjus-

tified restraint. In the nineteenth century, liberalism

had a strong economic strain, stressing industrial-

ization and laissez-faire economics. With one no-

table exception, Russia’s first liberals were little

concerned with economic affairs, as the country re-

mained mired in a semi-feudal agrarian economy.

And at all times, the quest for political liberty was

at the heart of Russian liberalism.

While it is impossible to select a starting point

that will satisfy everyone, an early figure in the

quest for freedom was Alexander Radishchev, a

well-educated and widely traveled Russian noble-

man. He is best known for his A Journey from Pe-

tersburg to Moscow (1790) that vividly exposed the

evils of Russian serfdom, an institution little dif-

ferent from slavery in the American south of the

time. An enraged Empress Catherine the Great

(r. 1762–1796) demanded his execution but settled

for Radishchev’s banishment to Siberia. Pardoned

in 1799, he was nonetheless a broken man who

committed suicide in 1802. Yet Radishchev served

as an inspiration to both radicals and liberals for

decades to come.

In particular he inspired the Decembrist move-

ment of 1825. This group of noble military offi-

cers attempted to seize power in an effort so

confusing that they are known simply by the

month of their failed coup. Five of the conspirators

were executed, but many of them advocated the

abolition of serfdom and autocracy, two hallmarks

of early Russian liberalism.

Under Emperor Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855), vir-

tually all talk of real reform earned the attention

of the secret police. Yet some Russians found a way

to express themselves; most important was the his-

torian, Timofei Granovsky, who used his lectern to

express his hostility to serfdom, advocacy of reli-

gious intolerance, and his admiration for parlia-

mentary regimes. His influence was largely limited,

however, to his pupils, including one of Russia’s

most famous liberals, the philosopher and histo-

rian Boris Chicherin.

Chicherin’s political career began under the re-

form-minded Emperor Alexander II (r. 1855–1881)

and included both theoretical and practical pur-

suits. The author of several books and innumer-

LIBERALISM

859

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

able articles and reviews, Chicherin was also a pro-

fessor and an active politician. His liberalism in-

cluded a vigorous defense of personal liberties

protected by law and a consistent rejection of vio-

lence to achieve political change. He was the first

prominent Russian liberal to defend a free market

as a prerequisite for political liberty, squarely

breaking with the emerging socialist movement.

Another important liberal was Ivan Petrunke-

vich. Following two attempts on the life of Em-

peror Alexander II, the government issued an appeal

for public support against terrorism. In response,

Petrunkevich declared in 1878 that the people must

resist not only terror from below, but also terror

from above. That same year, he met with five ter-

rorists in an effort to unite all opponents of the

status quo, an effort that failed because the ter-

rorists rejected Petrunkevich’s demand that they

disavow violence. In an 1879 pamphlet he insisted

upon the convocation of a constituent assembly to

guarantee basic civil liberties. Despite frequent

clashes with the government, Petrunkevich re-

mained active in politics even after his exile fol-

lowing the Bolshevik revolution.

At the turn of the century, Russia was on the

eve of revolution. Rapid industrialization under ap-

palling conditions fostered a radical working class

movement, while a surge in the peasant popula-

tion produced widespread land hunger. At the same

time a middle class of capitalists and professionals

was emerging, and from it came many of Russia’s

leading liberals.

The last emperor, Nicholas II (1894–1917),

proved singularly incapable of handling the Her-

culean task of ruling Russia. He quickly dashed any

hopes liberals may have entertained for reform

when he dismissed notions of diluting his auto-

cratic power as “senseless dreams.” Nonetheless,

the liberals remained active.

In 1901 they established their own journal, Lib-

eration, and two years later an organization, the

Union of Liberation. When Russia exploded in the

Revolution of 1905, the Union coordinated a move-

ment that ranged from strikes to terrorist assassi-

nations. Nicholas made concessions that only

fueled the rebellion and in April, liberals were de-

manding the convocation of a constituent assem-

bly to create a new order. In October, Nicholas

issued the October Manifesto, guaranteeing basic

civil liberties and the election of a national assem-

bly, the Duma, with real political power. By then

the liberals had their own political party, the Con-

stitutional Democrats (Cadets).

It seemed that liberalism’s great opportunity

had arrived. At the very least, several liberals

achieved national prominence in the years after

1905. Pyotr Struve, an economist and political sci-

entist, originally embraced Marxism, but by 1905,

he espoused a radical liberalism that called for full

civil liberties and the establishment of a constitu-

tional monarchy. He was elected to the Second

Duma and supported Russia’s entrance into the

World War I. When the Bolsheviks seized power in

1917, Struve joined the unsuccessful opposition

and soon left Russia for good.

The most prominent liberal of the late imper-

ial period was the historian, Pavel Milyukov.

In 1895 his political views cost him a teaching po-

sition, and he used the time to travel abroad, vis-

iting the United States. His public lectures

emphasized the need to abolish the autocracy and

the right to basic civil liberties. But Milyukov also

realized that liberalism was doomed if it failed to

address the land issue in an overwhelmingly agrar-

ian nation.

Milyukov supported Russia’s participation in

World War I, but by 1916 he was so exasperated

with the catastrophic prosecution of the war that

he publicly implied that treason had penetrated to

the highest levels of the government. When the au-

tocracy collapsed in February 1917, Milyukov be-

came the foreign minister of the provisional

government, the highest office ever reached by a

Russian liberal. It did not last long. Under great

pressure, in May he issued a promise to the allies

that Russia would remain in the war to the bitter

end. Antiwar demonstrations ensued, and Mi-

lyukov was forced to resign. He died in France in

1943.

Despite the efforts of Milyukov, Struve, and

others, Russian liberalism increasingly fell between

two stools. On the one hand were the revolution-

aries who had nothing but contempt for liberals

with their willingness to compromise with the im-

perial system. The regime’s supporters, on the

other hand, saw the liberals as little better than

bomb-throwing revolutionaries. In a society as po-

larized as Russia was in 1914, with a political sys-

tem as archaic as its leader was incompetent, any

form of political moderation was likely doomed.

The Communists thoroughly crushed all op-

position, but some brave individuals continued to

call for human freedom, the most important being

Andrei Sakharov. A physicist by training, he was

a man of extraordinary intelligence and courage.

LIBERALISM

860

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Admitted as a full member of the Soviet Academy

of Sciences at the age of thirty-two, he was de-

prived of the lavish privileges accorded the scien-

tific elite of the USSR on account of his subsequent

advocacy of human rights and civil liberties. Un-

der Mikhail Gorbachev, Sakharov returned to na-

tional prominence; he died almost exactly two

years before the demise of the Soviet Union on

Christmas 1991.

In the Russian Federation of the early twenty-

first century, political terms such as liberal, conser-

vative, radical, and so on are almost meaningless.

But liberalism in its more traditional sense won a

major victory in the 1996 presidential election

when Boris Yeltsin defeated the Communist candi-

date Gennady Zyuganov. Yeltsin’s liberal creden-

tials were later much criticized, but he successfully

defended freedom of speech, the press, and religion,

and he initiated free market reforms. At the very

least, liberalism became more powerful in Russia

than any time in the past.

See also: CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; DECEM-

BRIST MOVEMENT AND REBELLION; MILYUKOV, PAUL

NIKOLAYEVICH; NICHOLAS II; RADISHCHEV, ALEXAN-

DER NIKOLAYEVICH; SAKHAROV, ANDREI DMITRIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fischer, George. (1958). Russian Liberalism: From Gentry

to Intelligentsia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Hamburg, Gary. (1992). Boris Chicherin and Early Russ-

ian Liberalism. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press.

Roosevelt, Patricia. (1986). Apostle of Russian Liberalism:

Timofei Granovsky. Newtonville, MA: Oriental Re-

search Partners.

Stockdale, Melissa K. (1996). Paul Miliukov and the Quest

for a Liberal Russia, 1880–1918. Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University Press.

Timberlake, Charles, ed. (1972). Essays on Russian Liber-

alism. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Walicki, Andrzej. (1986). Legal Philosophies of Russian

Liberalism. Oxford: Clarendon.

H

UGH

P

HILLIPS

LIBERMAN, YEVSEI GRIGOREVICH

(1897–1983), economist who proposed making

profit the main success indicator for Soviet enter-

prises.

Yevsei Grigorevich Liberman’s education and

career were erratic and undistinguished. He grad-

uated from the law faculty at Kiev University in

1920 and then earned a candidate of sciences de-

gree at the Institute of Labor in Kharkov. In 1930

he began to work in the Kharkov Engineering-

Economics Institute. During World War II he was

evacuated to Kyrgyzstan, where he held positions

in the Ministry of Finance and the Scientific Re-

search Institute of Finance. He returned to the

Kharkov Engineering-Economics Institute after the

war and in 1963 became a professor of statistics at

Kharkov University. At various times he was also

the director of a machinery plant and a consultant

to machinery plants.

Liberman’s personal experience in actual enter-

prises helped him to understand the shortcomings

of the Soviet incentive system. As early as his doc-

toral dissertation in 1957, he suggested reducing

the number of planning indicators for firms and

focusing on profit instead. In 1962 he became a

cause célèbre when he published an article in Pravda

that proposed making profit the sole success indi-

cator in evaluating enterprise performance. Since

Liberman was not a significant player in economic

reform circles, it is thought that others, such as

Vasily Sergeyevich Nemchinov, engineered publi-

cation of this article as a trial balloon. Thus he was

more significant as a lightning rod around which

controversy swirled than as a thinker with a so-

phisticated understanding of economics or of the

complex task of transforming the Soviet adminis-

trative command system.

See also: NEMCHINOV, VASILY SERGEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Liberman, E. G. (1971). Economic Methods and the Effec-

tiveness of Production. White Plains, NY: International

Arts and Sciences Press.

Treml, Vladimir G. (1968). “The Politics of Liberman-

ism.” Soviet Studies 29:567–572.

R

OBERT

W. C

AMPBELL

LIGACHEV, YEGOR KUZMICH

(b. 1920), a secretary of the Central Committee of

the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Decem-

ber 1983 to mid-1990), and member of the Polit-

buro (April 1985 to mid-1990).

LIGACHEV, YEGOR KUZMICH

861

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Yegor Ligachev was a leading orthodox critic

of many aspects of General Secretary Mikhail Gor-

bachev’s program of reforms. From 1985 until late

1988 he served as the party’s informal second sec-

retary responsible for the supervision of official ide-

ology and personnel management. During this

period, he clashed with Secretary Alexander Yakovlev

over cultural and ideological policies and openly as-

sailed the cultural liberalization fostered by glas-

nost and the growing public criticism of the USSR’s

past.

While Ligachev publicly endorsed perestroika in

general terms, he opposed Gorbachev’s efforts to

limit party officials’ responsibilities and to expand

the legislative authority of the soviets. He was widely

identified with the orthodox critique of perestroika

provided by Nina Andreyeva in early 1988. At the

Nineteenth Conference of the Communist Party of

the Soviet Union (CPSU) in mid-1988, Ligachev re-

fused to publicly endorse Gorbachev’s reform of the

Secretariat and its subordinate apparat. In Septem-

ber 1988 he lost his position as second secretary and

was named director of the newly created agricul-

tural commission of the Central Committee.

Ligachev was deeply disturbed by the collapse

of Communist power in Eastern Europe and the

flaccid response to those events on the part of the

Gorbachev regime. Nor did he support the general

secretary’s decision to end the CPSU’s monopoly of

power in February 1990. In the spring of 1990 he

moderated his critique of the regime in an appar-

ent effort to win election as deputy general secre-

tary at the Twenty-eighth Party Congress, but he

lost the election by a wide margin. Following the

reform of the Secretariat and Politburo at the con-

gress he retired from both bodies. He did not fully

condemn the attempted coup against Gorbachev in

August 1991, but he vigorously denied charges of

direct involvement in these events.

See also: ANDREYEVA, NINA ALEXANDROVNA; AUGUST

1991 PUTSCH; GLASNOST; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL

SERGEYEVICH; PERESTROIKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Harris, Jonathan. (1989). “Ligachev on Glasnost and Per-

estroika.” In Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East Eu-

ropean Studies, no. 706. Pittsburgh, PA: University

Center for Russian and East European Studies.

Ligachev, Egor. (1993). Inside Gorbachev’s Kremlin. New

York: Pantheon Books.

J

ONATHAN

H

ARRIS

LIKHACHEV, DMITRY SERGEYEVICH

(1906–1999), cultural historian, religious philoso-

pher.

Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachev was known as

a world-renowned academic, literary and cultural

historian, sociologist, religious philosopher, pris-

oner of the gulag, and preservationist of all kinds

of Russian culture. But he was much more. By the

end of his life he had become one of the most

respected citizens of Russia. As an academic,

Likhachev was the preeminent expert of his gener-

ation on medieval Russian culture, and the litera-

ture of the tenth through seventeenth centuries in

particular, perhaps the most prolific writer and re-

searcher on Russian culture in the twentieth cen-

tury. One of his obituaries described him as “one

of the symbols of the twentieth century . . . [whose]

life was devoted to education . . . the energetic ser-

vice of the highest ideals of humanism, spiritual-

ity, genuine patriotism, and citizenship . . .

consistently preaching eternal principles of moral-

LIKHACHEV, DMITRY SERGEYEVICH

862

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

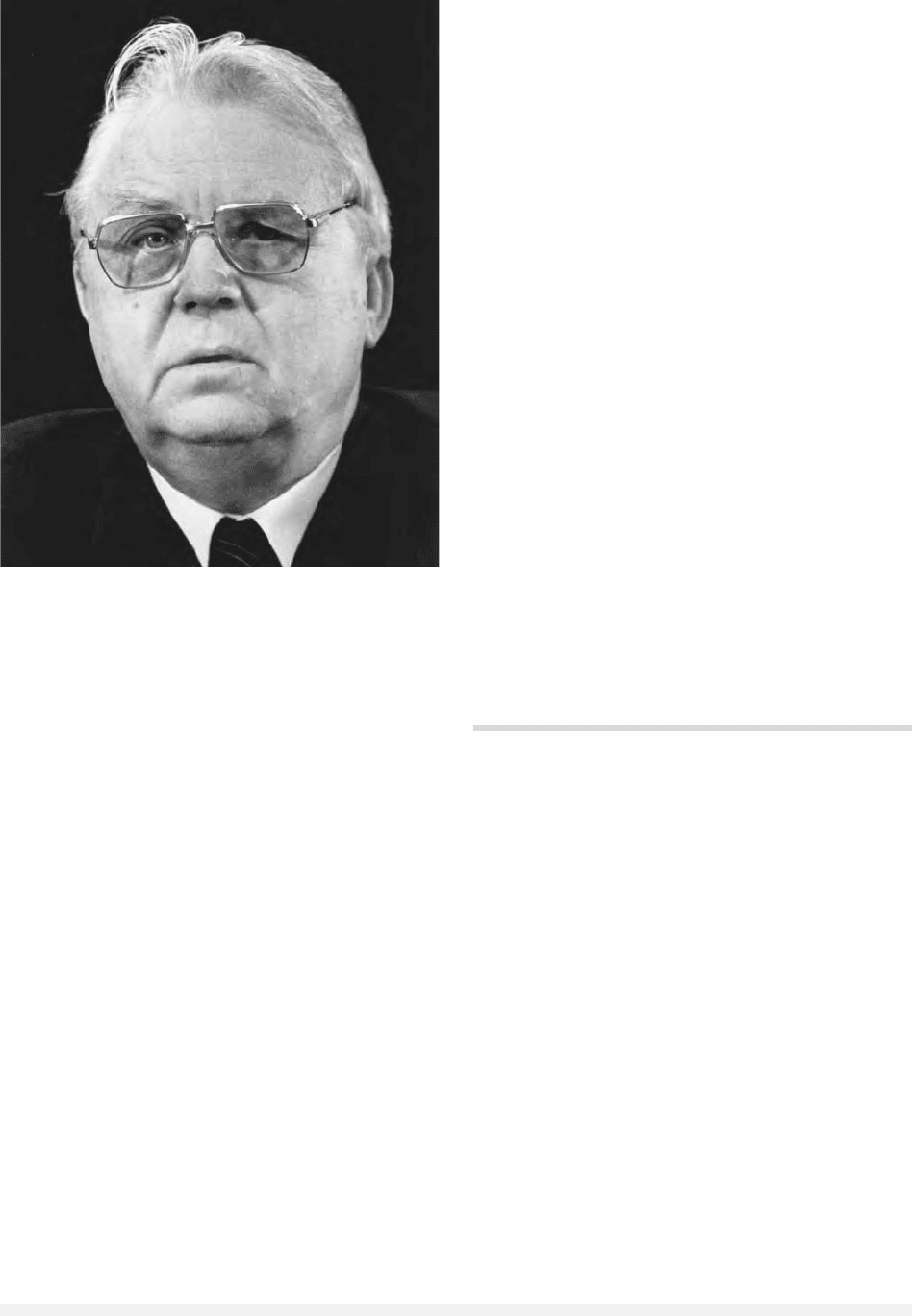

Yegor Ligachev criticized Gorbachev’s reforms and Yeltsin’s

leadership style. P

ACH

/C

ORBIS

-B

ETTMANN

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

..