Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

rived in Moscow in 1685. There they established

the first formal educational institution in Russian

history, the Slavo-Greco-Latin Academy, and par-

ticipated in a heated debate known as the Eucharist

conflict, principally against Sylvester Medvedev.

They taught in the Academy until 1694, when they

were removed for attempted flight after a scandal

involving one of their relatives. After a brief stint

as translators in the Muscovite Printing Office and

as tutors of Italian, they were accused of heresy by

one of their former students. Between 1698 and

1706, they were transferred to various monaster-

ies, both in Moscow and in other towns, where

they continued their authorial activities. In 1706

they were sent to Novgorod and established a

school under the supervision of Metropolitan Iov.

In 1707 Sophronios was recalled to Moscow to

work in a Greek school there. Ioannikios taught in

Novgorod until 1716, when he joined his brother

in Moscow. After his brother’s death, Sophronios

continued his teaching activities until 1723, when

he became archimandrite of the Solotsinsky

monastery in Ryazan until his death. The two

brothers authored or coauthored many polemical

(anti-Catholic and anti-Protestant), philosophical,

and theological works, sermons, panegyrics, ora-

tions, and, most important, textbooks for their

students. A large part of these textbooks were adap-

tations of those used in Jesuit colleges. Through

their educational activities, the Leichoudes, though

Orthodox, imparted to their students the Jesuit in-

terpretation of Aristotelian philosophy, and the

Baroque culture of contemporary Europe. As such,

they contributed to the Russian elite’s westerniza-

tion and its preparedness to accept Peter the Great’s

own westernizing reforms.

See also: ORTHODOXY; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH;

SLAVO-GRECO-LATIN ACADEMY; WESTERNIZERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chrissidis, Nikolaos A. (2000). “Creating the New

Educated Elite: Learning and Faith in Moscow’s

Slavo-Greco-Latin Academy, 1685–1694.” Ph.D.

dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

N

IKOLAOS

A. C

HRISSIDIS

LEIPZIG, BATTLE OF

The “Battle of Nations” near Leipzig between allied

Russian, Prussian, Austrian, and Swedish armies

against Napoleon’s army from October 16 to 19,

1813.

Napoleon’s army (approximately 200,000

troops, 747 field guns), concentrated near Leipzig,

faced four allied armies, totaling 305,000 troops—

125,000 of them Russian, 90,000 Austrian, 72,000

Prussians, 18,000 Swedes—and 1,385 field guns.

The battle took place on a plain near Leipzig on Oc-

tober 16, mainly on the grounds of the Bohemian

army (133,000 men, commanded by the Austrian

field marshal Karl Schwarzenberg), which ap-

proached the city from the south. Napoleon tried

to defeat the coalition armies one by one. He con-

centrated 122,000 men against the Bohemian

army, and 50,000 under the command of marshal

Michel Ney against the Silesian army (60,000 men,

commanded by the Prussian general Gebhardt

Blücher), attacking from the north.

The opposing sides’ positions did not suffer

much change by the end of the day. Casualties

turned out to be relatively even (30,000 each), but

the allies’ casualties were compensated with the ar-

rival of the North army (58,000 men, commanded

by Karl–Juhan Bernadotte) and the Polish army

(54,000 men, commanded by Russian general

Leonty Bennigsen) on October 17. Meanwhile,

Napoleon’s army received a mere 25,000 men as a

reinforcement.

On the morning of October 18, the allies at-

tacked Napoleon’s positions. As a result of a fierce

battle, they gained no significant territorial advan-

tage. The allies, however, sent only 200,000 men

to battle, while 100,000 more were kept in reserve.

The French, meanwhile, had nearly exhausted their

ammunition. On the night of October 18,

Napoleon’s armies were drawn back to Leipzig, and

began their retreat in the morning. In the middle

of the day on October 19, the allies entered Leipzig.

Napoleon’s losses at Leipzig amounted to

100,000 men killed, wounded, and taken captive,

and 325 field guns. The allies lost approximately

80,000 men, of them 38,000 Russians. The allied

victory at Leipzig led to the cleansing of the terri-

tories of Germany and Holland of Napoleon’s

forces.

See also: NAPOLEON I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nafziger, George F. (1996). Napoleon at Leipzig: the Bat-

tle of Nations, 1813. Chicago, IL: Emperor’s Press.

LEIPZIG, BATTLE OF

843

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Smith, Digby George. (2001). 1813, Leipzig: Napoleon and

the Battle of the Nations. London: Greenhill Books;

Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

O

LEG

B

UDNITSKII

LENA GOLDFIELDS MASSACRE

The Lena Goldfields Massacre of April 4, 1912,

shook Russian society and rekindled the revo-

lutionary and workers’ movements after the

post–1905 repression. The shooting occurred dur-

ing a strike at the gold fields on the upper branches

of the Lena River to the northeast of Lake Baikal.

The Lena Goldfields Company, owned by promi-

nent Russian and British investors, had recently es-

tablished a monopoly of the region’s mines, which

produced most of Russia’s gold. Individuals of the

highest government rank held managerial positions

in the company. The fact that Russia’s currency

was on the gold standard further enhanced the

company’s significance. Especially after the joint

shocks of the Russo–Japanese War and the Revo-

lution of 1905, the ruble’s health in association

with renewed economic expansion vitally con-

cerned the imperial government. When the strike

broke out during late February 1912 in protest of

generally poor conditions, the government and

company officials in St. Petersburg naturally

wished to limit the strike. These hopes were frus-

trated by a group of employees and workers,

political exiles with past socialist and strike expe-

rience, who provided careful advice to the strikers.

Consequently, the workers avoided overstepping

the boundaries of legal strike activity. Company of-

ficials refused to meet the main strike demands, in-

cluding a shorter workday and higher pay.

Workers, whose patience had been tried by repeated

company violations of the work contract and ex-

isting labor laws, as confirmed by the chief min-

ing inspector and the governor of Irkutsk province,

refused to end the strike without real concessions.

Working closely with company officials, the

government sent a company of soldiers to join the

small contingent already on duty near the mines

and finally, after all negotiations failed, decided to

break the five–week impasse by arresting the strike

leaders. This ill–advised action carried out on April

3 only strengthened the workers’ resolve. On April

4, a large crowd of unarmed miners headed for the

administration building to petition for the release

of the leaders. Alarmed by the sudden appearance

of four thousand workers, police and army offi-

cers ordered the soldiers to open fire. Roughly five

hundred workers were shot, about half mortally.

Subsequently, the official government investigative

commission under Senator Sergei Manukhin

blamed the company and high government officials

both for the conditions that underlay the strike and

for the shooting.

The shooting unleashed a firestorm of protest

against the government and the company, includ-

ing in the press and in the State Duma. Especially

damaging were accusations of collusion between

state and company officials aimed at using force to

end the peaceful strike. Even groups normally sup-

portive of the government levied a barrage of crit-

icism. On a scale not seen since 1905, strikes broke

out all over Russia and did not cease until the out-

break of World War I. The revolutionary parties

also swung into action with leaflets and demon-

strations. The oppositionist movement found its

cause inadvertently aided when Minister of the In-

terior Nikolai Makarov asserted to the State Duma

about the shooting: “Thus it has always been and

thus it will always be.” This phrase, which caused

an additional firestorm of protest, seemed to sym-

bolize the government’s stance toward laboring

Russia. Spurred by the shooting and the govern-

ment’s attitude, revolutionary activities again

plagued the tsarist regime, now permanently

stamped as perpetrator of the Lena Goldfields Mas-

sacre.

See also: OCTOBER REVOLUTION; REVOLUTION OF 1905;

WORKERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Melancon, Michael. (1993). “The Ninth Circle: The Lena

Goldfield Workers and the Massacre of 4 April

1912.” Slavic Review 53(3):766-795.

Melancon, Michael. (2002). “Unexpected Consensus:

Russian Society and the Lena Massacre, April 1912.”

Revolutionary Russia 15(2):1-52.

M

ICHAEL

M

ELANCON

LEND LEASE

Lend-lease was a system of U.S. assistance to the

Allies in World War II. It was based on a bill of

March, 11, 1941, that gave the president of the

United States the right to sell, transfer into prop-

erty, lease, and rent various kinds of weapons or

LENA GOLDFIELDS MASSACRE

844

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

materials to those countries whose defense the pres-

ident deemed vital to the defense of the United

States itself. According to the system, the materi-

als destroyed, lost, or consumed during the war

should not be subject to payment after the war.

The materials that were not used during the war

and that were suitable for civilian consumption

should be paid in full or in part, while weapons

and war materials could be demanded back. After

the United States entered the war, the concept of

lend lease, originally a system of unidirectional U.S.

aid, was transformed into a system of mutual aid,

which involved pooling the resources of the coun-

tries in the anti-Hitler coalition (known as the con-

cept of “pool”). Initially authorized for the purpose

of aiding Great Britain, in April 1941 the Lend-Lease

Act was extended to Greece, Yugoslavia, and China,

and, after September 1941, to the Soviet Union. By

September, 20, 1945, the date of cancellation of the

Lend-Lease Act, American aid had been received by

nearly forty countries.

During World War II, the U.S. spent a total of

$49.1 billion on the Lend-Lease Act. This included

$13.8 billion in aid to Great Britain and $9.5 bil-

lion to the USSR. Repayment in kind—called “re-

verse lend-lease”—was estimated at $7.8 billion, of

which $2.2 million was the contribution of the

USSR in the form of a discount for transport ser-

vices.

The Soviet Union received aid on lend-lease

principles not only from the United States, but also

from the states of the British Commonwealth, pri-

marily Great Britain and Canada. Economic rela-

tions between them were adjusted by mutual aid

agreements and legalized by special Allies’ proto-

cols, renewable annually. The First Protocol was

signed in Moscow on October, 1, 1941; the second

in Washington (October 6, 1942); the third in Lon-

don (September 1, 1943); and the fourth in Ottawa

(April, 17, 1945). The Fourth Protocol was added

by a special agreement between the USSR and the

United States called the “Program of October 17,

1944” (or “Milepost”), intended for supplies for use

by the Soviet Union in the war against Japan.

On the basis of those documents, the Soviet

Union received 18,763 aircraft, 11,567 tanks and

self-propelled guns, 7,340 armored vehicles and ar-

mored troop-carriers, more than 435,000 trucks

and jeeps, 9,641 guns, 2,626 radar, 43,298 radio

stations, 548 fighting ships and boats, and 62 cargo

ships. The remaining 75 percent of cargoes im-

ported into the USSR consisted of industrial equip-

ment, raw material, and foodstuffs. A significant

portion (up to seven percent) of supplies was lost

during transportation.

Most of the cargoes sent to the USSR were de-

livered by three main routes: via Iran, the Far East,

and the northern ports Arkhangelsk and Mur-

mansk. The last route was the shortest but also the

most dangerous.

After the war the United State cancelled all

lend-lease debts except that of the USSR. In 1972

the USSR and the United States signed an agree-

ment that the USSR would pay $722 million of its

debt by July 1, 2001.

See also: FOREIGN DEBT; WORLD WAR II; UNITED STATES,

RELATIONS WITH, NORTHERN CONVOYS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beaumont, Joan. (1980). Comrades in Arms: British Aid

to Russia, 1941–1945. London: Davis-Poynter.

Hall, H. Duncan; Scott, J. D., and Wrigley, C. C. (1956).

Studies of Overseas Supply. London: H. M. Stationery

Off.

Herring, George C. (1973). Aid to Russia, 1941–1946:

Strategy, Diplomacy, the Origins of the Cold War. New

York: Columbia University Press.

Jones, Robert Huhn. (1969). The Roads to Russia: United

States Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union. Norman: Uni-

versity of Oklahoma Press.

Van Tuyll, Hubert P. (1989). Feeding the Bear: American

Aid to the Soviet Union, 1941–1945. New York: Green-

wood Press.

M

IKHAIL

S

UPRUN

LENIN ENROLLMENT See COMMUNIST PARTY OF

THE SOVIET UNION.

LENINGRAD AFFAIR

The “Leningrad Affair” refers to a purge between

1949 and 1951 of the city’s political elite and of

nationally prominent communists who had come

from Leningrad. More than two hundred Lenin-

graders, including many family members of those

directly accused, were convicted on fabricated po-

litical charges, and twenty-three were executed.

Over two thousand city officials were fired from

their jobs. Hundreds from many other cities were

jailed during this purge.

LENINGRAD AFFAIR

845

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The “Leningrad Affair” derived largely from a

power struggle between Soviet leader Josef Stalin’s

two leading potential successors: Andrei Zhdanov,

Leningrad’s party chief during the city’s lengthy

wartime siege, and Georgy Malenkov, supported by

the head of the political police, Lavrenti Beria. Zh-

danov’s sudden death of apparent natural causes

in the late summer of 1948 left his protégés from

Leningrad vulnerable. In early 1949 Malenkov

charged that the Leningraders were trying to cre-

ate a rival Communist Party of Russia in conspir-

acy with another former Leningrad party chief,

Alexei Kuznetsov. Malenkov used as pretexts a

wholesale trade market that had been set up in

Leningrad without Moscow’s permission, as well

as alleged voting irregularities in a Leningrad party

conference. The Leningrad party members were

also charged with treason.

Aside from Kuznetsov, the most prominent vic-

tims of the “Leningrad Affair” were Politburo mem-

ber and Gosplan chairman Nikolai Voznesensky

and first secretary of the Leningrad party commit-

tee Pyotr Popkov. The three were shot along with

others on October 1, 1950. The purge signaled a

return to the violent and conspiratorial politics of

the 1930s. It eliminated the Leningraders as con-

tenders for national power and downgraded

Leningrad essentially to the status of a provincial

city within the USSR.

See also: BERIA; LAVRENTI PAVLOVICH; MALENKOV,

GEORGY MAKSIMILYANOVICH; ZHDANOV, ANDREI

ALEXANDROVICH; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Knight, Amy. (1993). Beria: Stalin’s First Lieutenant.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Volkogonov, Dmitri. (1991). Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy,

ed. and tr. Harold Shukman. New York: Grove Wei-

denfeld.

Zubkova, Elena. (1998). Russia After the War: Hopes, Il-

lusions, and Disappointments, 1945-1957, tr. and ed.

Hugh Ragsdale. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

R

ICHARD

B

IDLACK

LENINGRAD, SIEGE OF

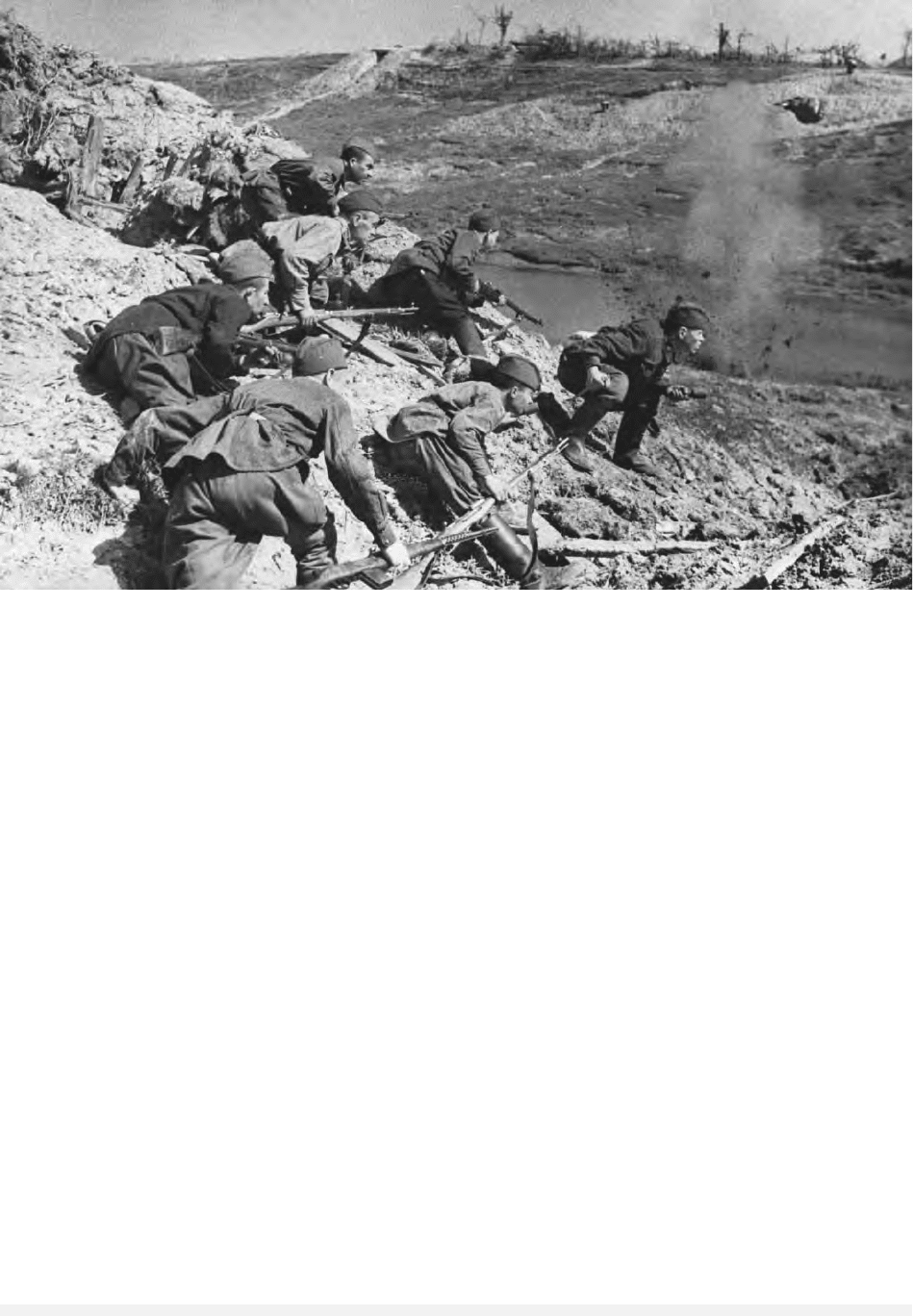

For 872 days during World War II, German and

Finnish armies besieged Leningrad, the Soviet

Union’s second largest city and important center

for armaments production. According to recent es-

timates, close to two million Soviet citizens died in

Leningrad or along nearby military fronts between

1941 and 1944. Of that total, roughly one million

civilians perished within the city itself.

The destruction of Leningrad was one of Adolf

Hitler’s strategic objectives in attacking the Soviet

Union on June 22, 1941. On September 8, 1941,

German Army Group North sealed off Leningrad.

It advanced to within a few miles of its southern

districts and then took the town of Schlisselburg

along the southern shore of Lake Ladoga. That

same day, Germany launched its first massive aer-

ial attack on the city. Germany’s ally, Finland,

completed the blockade by retaking territory north

of Leningrad that the Soviet Union had seized from

Finland during the winter war of 1939–1940.

About 2.5 million people were trapped within the

city. The only connection that Leningrad main-

tained with the rest of the Soviet Union was across

Lake Ladoga, which German aircraft patrolled. Fin-

land refused German entreaties to continue its ad-

vance southward along Ladoga’s eastern coast to

link up with German forces.

Hitler’s plan was to subdue Leningrad through

blockade, bombardment, and starvation prior to

seizing the city. German artillery gunners, together

with the Luftwaffe, killed approximately 17,000

Leningraders during the siege. Although supplies of

raw materials, fuel, and food dwindled rapidly

within Leningrad, war plants within the city lim-

its produced large numbers of tanks, artillery guns,

and other weapons during the fall of 1941 and con-

tinued to manufacture vast quantities of ammuni-

tion throughout the rest of the siege.

Most civilian deaths occurred during the win-

ter of 1941–1942. Bread was the only food that

was regularly available, and between November 20

and December 25, 1941, the daily bread ration for

most Leningraders dropped to its lowest level of

125 grams, or about 4.5 ounces. To give the ap-

pearance of larger rations, inedible materials, such

as saw dust, were baked into the bread. To make

matters worse, generation of electrical current was

sharply curtailed in early December because only

one city power plant operated at reduced capacity.

Most Leningraders thus lived in the dark; they

lacked running water because water pipes froze and

burst. Temperatures during that especially cold

winter plummeted to -40 degrees Farenheit in late

January. Residents had to fetch water from central

mains, canals, and the Neva River. The frigid

LENINGRAD, SIEGE OF

846

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

winter, however, brought one advantage: Lake

Ladoga froze solid enough to become the “Road of

Life” over which food was trucked into the city,

and some 600,000 emaciated Leningraders were

evacuated.

During the spring and summer of 1942, those

remaining in Leningrad cleaned up debris and filth

from the previous winter, buried corpses, and

planted vegetable gardens in practically every open

space they could find. A fuel pipeline and electrical

cable were laid under Ladoga, and firewood and

peat stockpiled in anticipation of a second siege

winter. The evacuation over Ladoga continued, and

by the end of 1942 the city’s population was pared

down to 637,000. Repeated attempts were made in

1942 to lift the siege; yet it was not until January

1943 that the Red Army pierced the blockade by

retaking a narrow corridor along Ladoga’s south-

ern coast. A rail line was extended into the city,

and the first train arrived from “the mainland” on

February 7. Nevertheless, the siege would endure

for almost another year as German guns contin-

ued to pound Leningrad and its tenuous rail link

from close range. On January 27, 1944, the block-

ade finally ended as German troops retreated all

along the Soviet front.

Leningrad’s defense held strategic importance

for the Soviet Union. Had the city fallen in the au-

tumn of 1941, Germany could have redeployed

larger forces toward Moscow and thereby increased

the chances of taking the Soviet capital. Lenin-

graders who endured the horrific ordeal were mo-

tivated by love of their native city and country,

fear of what German occupation might bring, and

the intimidating presence of Soviet security forces.

In just the first fifteen months of the war, 5,360

Leningraders were executed for a variety of alleged

crimes, including political ones.

Relations between Leningrad’s leadership and

the Kremlin were tempestuous during the siege or-

deal. The city’s isolation gave it a measure of au-

tonomy from Moscow, and the suffering Leningrad

endured promoted the growth of a heroic reputa-

tion for the city. From 1949 to 1951 many of

Leningrad’s political, governmental, industrial, and

LENINGRAD, SIEGE OF

847

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet troops launch a counterattack during the Nazi siege of Leningrad. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

cultural leaders were fired, and some executed, on

orders from the Kremlin during the notorious

Leningrad Affair.

See also: LENINGRAD AFFAIR; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Glantz, David M. (2002). The Battle for Leningrad,

1941–1944. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

Goure, Leon. (1962). The Siege of Leningrad. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Petrovskaya Wayne, Kyra. (2000). Shurik: A Story of the

Siege of Leningrad. New York: The Lyons Press.

Salisbury, Harrison. (1969). The 900 Days: The Siege of

Leningrad. New York: Harper & Row.

Simmons, Cynthia and Perlina, Nina, eds. (2002). Writ-

ing the Siege of Leningrad: Women’s Diaries, Memoirs,

and Documentary Prose. Pittsburgh, PA: University of

Pittsburgh Press.

Skrjabina, Elena. (1971). Siege and Survival: The Odyssey

of a Leningrader. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Uni-

versity Press.

R

ICHARD

B

IDLACK

LENIN LIBRARY See RUSSIAN STATE LIBRARY.

LENIN’S TESTAMENT

Lenin’s so-called Political Testament was actually a

letter dictated secretly by Vladimir Ilich Lenin in

late December 1922, which he intended to discuss

at the Twelfth Party Congress in April 1923. The

letter was initially known only to Lenin’s wife

Nadezhda Krupskaya and the two secretaries who

took down its contents. Unfortunately, on March

10, 1923, Lenin suffered a stroke, which put an

end to his active role in Soviet politics. It is widely

believed that Krupskaya, fearing that its contents

might cause further Party disunity, kept the testa-

ment under lock and key, until Lenin’s death in

January 1924. She then felt it safe enough to be

read to delegates at the Thirteenth Congress. All

those attending this Congress were sworn to keep

the contents of the letter a secret. It was then sup-

pressed in the Soviet Union, and so the document

did not appear in English until 1926.

A number of versions are currently in circula-

tion, each of which has been manipulated for po-

litical purposes, especially by those who wish to

criticize Josef Stalin or show how positively Leon

Trotsky was viewed by Lenin. Nevertheless it is

clear that Lenin was concerned in the Testament

with potential successors and that most of all he

favored Trotsky rather than his actual successor

Stalin. The Testament of December 29 indicates it

clear that Lenin wanted to avoid an irreversible split

in the Party and provides a balanced assessment of

all prospective candidates. With regard to Trotsky,

Lenin notes that “[as] his struggle against the CC

[Central Committee] on the question of the People’s

Commissariat has already proved, [he] is distin-

guished not only by outstanding ability. He is per-

sonally perhaps the most capable man in the

present CC, but he has displayed excessive self-

assurance and shown preoccupation with the

purely administrative side of the work.” Concern-

ing Stalin, by contrast, Lenin points out that he “is

too rude, and this defect, although quite tolerable

in our midst and in dealings among us Commu-

nists, becomes intolerable in a general secretary.

That is why I suggest that the comrades think

about a way of removing Stalin from that post and

appointing (sic) another man in his stead who in

all other respects differs from Comrade Stalin in

having only one advantage, namely, that of being

more tolerant, more loyal, less capricious, and so

forth.” In a postscript dated March 5, 1923, Lenin

criticizes Stalin for insulting Lenin’s wife and adds

that unless they receive a retraction and apology

then “relations between us should be broken off.”

In relation to other members of the CC, Lenin points

to the October episode in which Zinoviev and

Kamenev objected to the idea of an immediate

armed insurrection against the Provisional Gov-

ernment and also to Trotsky’s Menshevik past, but

he adds that neither should suffer any blame or

personal consequence.

Lenin was therefore extremely worried about

the degree of power Stalin had attained and thought

this was dangerous for the future of the Party and

Russia insofar as he was capable of abusing this

power. He advocated that Stalin be removed from

the post of general secretary. It is generally agreed

by historians that Trotsky’s failure to use the Tes-

tament was a major political mistake and an error

that allowed Stalin to rise to power. But it is also

conceded that Trotsky, in agreeing not to use it in

this manner, was abiding by Lenin’s wishes to

avoid a split. Trotsky therefore put Party unity be-

fore his own ambitions.

See also: LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARI-

ONOVICH; TROTSKY, LEON DAVIDOVICH

LENIN LIBRARY

848

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buranov, Yuri. (1994). Lenin’s Will: Falsified and Forbid-

den. Amherst, NY: Prometheus.

Volkogonov, Dmitri. (1994). Lenin: A New Biography.

New York: Free Press.

Wolfe, Bertram D. (1984). Three Who Made a Revolution:

A Biographical History. New York: Stein and Day.

C

HRISTOPHER

W

ILLIAMS

LENIN’S TOMB

Shortly after the death of Vladimir Ilich Lenin in

1924, and despite the opposition of his wife,

Nadezhda Krupskaya, Soviet leaders built a mau-

soleum on Moscow’s Red Square to display his em-

balmed body. The architect Alexei V. Shchusev

designed two temporary cube-shaped wooden struc-

tures and then a permanent red granite pyramid-

like building that was completed in 1929. The top

of the mausoleum held a tribune from which Soviet

leaders addressed the public. This site became the cer-

emonial center of the Bolshevik state as Stalin and

subsequent leaders appeared on the tribune to view

parades on November 7, May 1, and other Soviet

ceremonial occasions. When Josef V. Stalin died in

1953, his body was placed in the mausoleum next

to Lenin’s. In 1961, as Nikita Khrushchev’s attack

on Stalin’s cult of personality intensified, Stalin’s

body was removed from the mausoleum and buried

near the Kremlin wall. Lenin and his tomb, how-

ever, remained the quintessential symbols of Soviet

legitimacy.

Because of Lenin’s status as unrivaled leader of

the Bolshevik Party, and because of Russian tradi-

tions of personifying political power, a personality

cult glorifying Lenin began to develop even before

his death. The Soviet leadership mobilized the

legacy of Lenin after 1924 to establish its own le-

gitimacy and gain support for the Communist

Party. Recent scholarship has disproved the idea

that it was Stalin who masterminded the idea of

embalming Lenin, instead crediting such figures as

Felix Dzerzhinsky, Leonid Krasin, Vladimir Bonch-

Bruevich, and Anatoly Lunacharsky. It has also

been suggested that the cult grew out of popular

Orthodox religious traditions and the philosophical

belief of certain Bolshevik leaders in the deification

of man and the resurrection of the dead through

science. The archival sources underscore the con-

tingency of the creation of the Lenin cult. They

show that Dzerzhinsky and other Bolshevik lead-

ers consciously manipulated popular sentiment

about Lenin for utilitarian political goals. Yet this

would not have created such a powerful political

symbol if it had not been rooted in the spiritual,

philosophical, and political culture of Soviet lead-

ers and the Soviet people. More than a decade af-

ter the fall of communism, Lenin’s Tomb continued

to stand on Red Square even though there were pe-

riodic calls for his burial.

See also: CULT OF PERSONALITY; KREMLIN; KRUPSKAYA,

NADEZHDA KONSTANTINOVNA; LENIN, VLADIMIR

ILICH; RED SQUARE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tucker, Robert C. (1973). Stalin as Revolutionary,

1879–1929. New York: Norton.

Tumarkin, Nina. (1983). Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in So-

viet Russia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

K

AREN

P

ETRONE

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

(1870–1924), revolutionary publicist, theoretician,

and activist; founder of and leading figure in the

Bolshevik Party (1903–1924); chairman of the So-

viet of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR/USSR

(1917–1924).

The reputation of Vladimir Ilich Lenin (pseu-

donym of V.I. Ulyanov) has suffered at the hands

of both his supporters and his detractors. The for-

mer turned him into an idol; the latter into a de-

mon. Lenin was neither. He was born on April 22,

1870, into the family of a successful school in-

spector from Simbirsk. For his first sixteen years,

Lenin lived the life of a child of a conventional, mod-

erately prosperous, middle-class, intellectual fam-

ily. The ordinariness of Lenin’s upbringing was first

disturbed by the death of his father, in January

1886 at the age of 54. This event haunted Lenin,

who feared he might also die prematurely, and in

fact died at almost exactly the same age as his fa-

ther. Then, in March 1887, Lenin’s older brother

was arrested for terrorism; he was executed the fol-

lowing May. The event aroused Lenin’s curiosity

about what had led his brother to sacrifice his life.

It also put obstacles in his path: As the brother of

a convicted terrorist, Lenin was excluded from

Kazan University. He eventually took a law degree,

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

849

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

with distinction, by correspondence from St Pe-

tersburg University in January 1892. However, his

real interests had already turned to serving the op-

pressed through revolution rather than at the bar.

All the indications suggest that Lenin was ini-

tially attracted to populism, and only later came

under the sway of Marxism. He joined a number

of provincial Marxist study circles, but first began

to attract attention when he moved to the capital,

St. Petersburg, and engaged in illegal political ac-

tivities among workers and intellectuals. In Febru-

ary 1894, he met fellow conspirator Nadezhda

Konstantinovna Krupskaya, who became his life-

long companion. After his first visit to Western Eu-

rope, in 1895, to meet the exiled leaders of Russian

Marxism, Lenin returned to St. Petersburg and

helped set up the League of Struggle for the Eman-

cipation of the Working Class. He was arrested in

December 1896 and, after prison interrogation in

St. Petersburg, was exiled to the village of Shushen-

skoe, in Siberia. Krupskaya, who was exiled sepa-

rately, offered to share banishment with him. The

authorities agreed, providing they married, which

they did in July 1898. Siberian exile, though rig-

orous in many respects, was an interlude of rela-

tive personal happiness in Lenin’s life. His lifelong

love of nature asserted itself in long walks, obser-

vation of social and animal life of the area, and fre-

quent hunting expeditions. He read a great deal,

communicated widely by letter with other social-

ists, and undertook research and writing. Direct po-

litical activity was not possible, and Lenin played

no part in the formation, in 1898, of the Russian

Social Democratic Workers’ Party (RSDLP), to

which he at first adhered to but from which he

later split. His term of exile ended in February,

1900. In July of that same year, he left Russia for

five years.

Up until that point much of Lenin’s political

writing, from his earliest known articles to his first

major treatise, The Development of Capitalism in

Russia, written while he was in Siberia, revolved

around the dispute between Marxists and populists.

The populists had proposed that Russia, given its

commune-based peasant class and underdeveloped

industry, could pass from its current condition of

“backwardness” to socialism without having to

first undergo the rigors of capitalist industrializa-

tion. Such a notion was an anathema to Lenin, who

believed the Marxist axiom that socialist revolution

could only follow from the overdevelopment of

capitalism, which would bring about its own col-

lapse. Lenin attacked the populist thesis in several

articles and pamphlets. The main theme of his trea-

tise on The Development of Capitalism in Russia was

that, in fact, capitalism was already well-entrenched

in Russia, and therefore the question of whether it

could be avoided was meaningless. Nonetheless, it

remained obvious that Russia had only a small

working class, and much of the rest of Lenin’s life

could be seen as an attempt to reconcile the actual

weakness of proletarian forces in Russia with the

country’s undoubted potential for some kind of

popular revolution, and to ensure Marxist and pro-

letarian dominance in any such revolution.

THE EMERGENCE OF

BOLSHEVISM (1902–1914)

Lenin worked to develop theoretical and practical

means to accomplish these closely related tasks. The

core of Lenin’s activity revolved around the orga-

nization and production of a series of journals. He

frequently described himself on official papers as a

journalist, and he did, in fact, write a prodigious

number of articles, as well as many longer works.

In 1902, Lenin produced one of his most widely

read and, arguably most misunderstood, pam-

phlets, What Is to Be Done?, which has been widely

taken to be the founding text of a distinctive Lenin-

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

850

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin sitting alone at his desk.

© B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

ist understanding of how to construct a revolu-

tionary party on the basis of what he called “pro-

fessional revolutionaries.” When it was first

published, however, it was read as a statement of

Marxist orthodoxy. Lenin asserted the primacy of

political struggle, opposing the ideas of the econo-

mists, who argued that trade union struggle would

serve the workers’ cause better than political rev-

olution.

It was only in the following year, 1903, that

Lenin began to break with the majority of the social-

democratic movement. Again, received opinion,

which claims Lenin split the party at the 1903

social-democratic party congress, oversimplifies the

nature of the break. Lenin’s key resolution at the

congress, in which he attempted to narrow the de-

finition of party membership, was voted down.

Later, by means many have judged foul, he gar-

nered a majority vote on the issue of electing mem-

bers to the editorial board of the party journal,

Iskra, on which Lenin and his supporters predom-

inated. It was from this victory that the terms Bol-

shevik (majoritarians) and Menshevik (minoritarians)

began to slowly come into vogue. However, the split

of the party was only fully completed over the next

few months, even years, of arid but fierce party

controversies. Lenin’s bitter polemic One Step For-

ward, Two Steps Back: The Crisis in Our Party, pub-

lished in Geneva in February 1904, marks a clearer

division and catalog of contentious issues than did

What Is to Be Done. It was criticized not only by its

target, Yuli Osipovich Martov, but also by Georgy

Valentinovich Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Vera Za-

sulich, Karl Kautsky, and Rosa Luxemburg. Lenin’s

remaining allies of the time included Alexander

Bogdanov, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Grigory Zinoviev,

and Lev Kamenev.

So much energy was involved in the dispute

that the development of an actual revolutionary

situation in Russia went almost unnoticed by the

squabbling exiles. Even after Bloody Sunday (Jan-

uary 22, 1905) Lenin’s attention remained divided

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

851

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

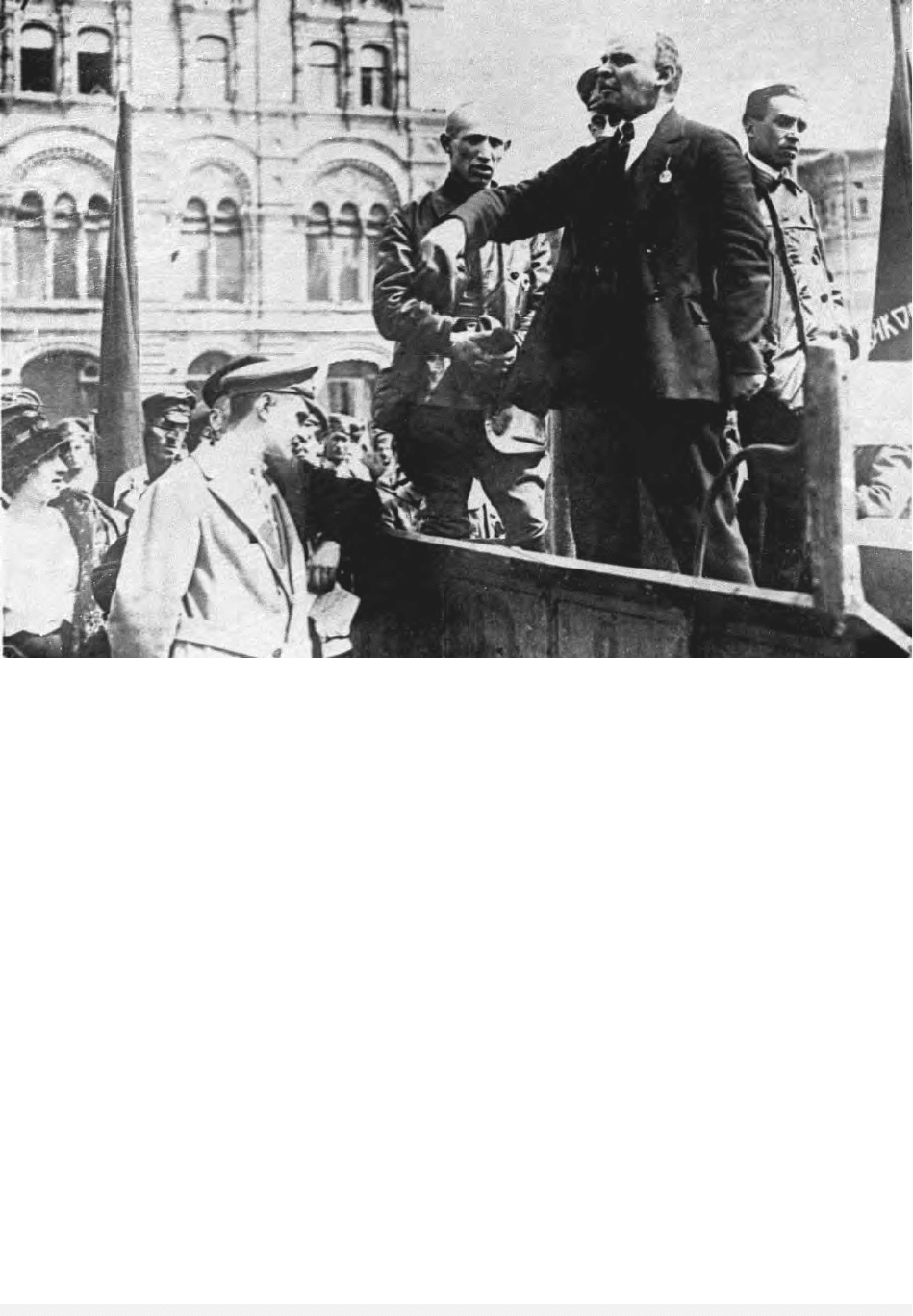

Lenin rallies the masses in this 1921 photo. A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

between the revolution and the task of splitting the

social democrats. With the latter aim in view, he

convened a Third Party Congress (London, April 25

to May 10) consisting entirely of Bolsheviks. Only

in August did Lenin’s main pamphlet on revolu-

tionary strategy, Two Tactics of Social Democracy in

the Russian Revolution, appear. Inevitably, the wrong

tactic—the identification of the revolution as bour-

geois—was attributed to the Mensheviks. The cor-

rect, Bolshevik, tactic, was the recognition of “a

democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the

peasantry,” which put less reliance on Russia’s

weak bourgeoisie. It also marked a significant ef-

fort by Lenin to incorporate the peasantry into the

revolutionary equation. This was another way in

which Lenin strove to compensate for the weak-

ness of the working class itself, and the peasantry

remained part of his strategy, in a variety of forms,

for the rest of his life.

In the atmosphere of greater freedom prevail-

ing after the issuing of the October Manifesto,

which was squeezed out of the tsarist authorities

under extreme duress and appeared to promise ba-

sic constitutional rights and liberties, Lenin re-

turned to Russia legally on November 21, 1905.

Even so, by December 17, police surveillance had

driven him underground. He supported the heroic

but catastrophically premature workers’ armed

uprising in Moscow in December. As conditions

worsened he retreated to Finland and then, in De-

cember 1907, left the Russian Empire for another

prolonged west European sojourn that lasted until

April 1917. Even before the failure of the 1905 rev-

olution, the party split continued to attract an in-

ordinate amount of Lenin’s attention. The break

with Leon Trotsky in 1906 and Bogdanov in 1908

removed the last significant thinkers from the Bol-

shevik movement, apart from Lenin himself, who

seemed constitutionally incapable of collaborating

with people of his own intellectual stature. The

break with Bogdanov was consummated in Lenin’s

worst book, Materialism and Empiriocriticism

(1909), a naïve and crudely propagandistic blun-

der into the realm of philosophy.

Politically, Lenin had wandered into the wilder-

ness as leader of a small faction that was situated

on the fringe of Russian radical politics and distin-

guished largely by its dependence on Lenin and its

refusal to contemplate a compromise that might

reunite the party. Lenin was also distinguished by

a ruthless morality of only doing that which was

good for the revolution. In its name friendships

were broken, and re-made, at a moment’s notice.

Later, when in power, he urged occasional episodes

of violence and terror to secure the revolution as

he understood it, although, like a sensitive war

leader, he did so reluctantly and only when he

thought it absolutely necessary.

For the next few years Lenin was at his least

influential. Had it not been for the backing of the

novelist Maxim Gorky, it is unlikely the Bolsheviks

could have continued to function. He had close sup-

port from Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, Lev

Borisovich Kamenev, Inessa Armand (with whom

he may have had a brief sexual liaison), and from

his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya. He also remained

close to his family. When possible, he vacationed

with them by the beaches of Brittany and Arca-

chon, or in the Swiss mountains. Lenin’s love of

nature, of walking and cycling, frequently coun-

teracted the immense nervous stresses occasioned

by his political battles. He was prone to a variety

of illnesses, which acted as reminders of his father’s

early death, convincing him that he had to do

things in a hurry. However, the second European

exile was characterized by frustration rather than

achievement.

FROM OBSCURITY TO POWER

(1914–1921)

The onset of the First World War began the trans-

formation of political fortune which was to bring

Lenin to power. His attitude to the war was char-

acteristically bold. Despite the collapse of the Sec-

ond International Socialist Movement and the

apparent wave of universal patriotism of August

1914, Lenin saw the war as a revolutionary op-

portunity and declared, as early as September 1914,

that socialists should aim to turn it into a Europe-

wide civil war. He believed that the basic class logic

of the situation, that the war was fought by the

masses to serve the interests of the imperialist bour-

geoisie, would eventually become clear to the

troops who, being trained in arms, would then turn

on their oppressors. He also wrote a major pam-

phlet, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism.

A Popular Outline (1916). Returning to the theme

of justifying a Marxist revolution in “backward”

Russia, he argued that Russia was a component

part of world capitalism and therefore the initial

assault on capital, though not its decisive battles,

could be conducted in Russia. Within months, just

such an opportunity arose.

Lenin’s transition from radical outcast to rev-

olutionary leader began after the fall of tsarism in

February 1917. A key moment was his declaration,

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

852

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY