Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Lake Tahoe

O

THER

“Zebra Mussels and Other Nonindigenous Species.” Sea Grant Great Lakes

Network. August 15, 2001 [June 19, 2002]. <http://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/

greatlakes/glnetwork/exotics.html>.

Lake Tahoe

A beautiful lake 6,200 ft (1,891 m) high in the Sierra Nevada,

straddling the California-Nevada state line, Lake Tahoe is

a jewel to both nature-lovers and developers. It is the tenth

deepest lake in the world, with a maximum depth of 1,600

ft (488 m) and a total volume of 37 trillion gallons. At the

south end of the lake sits a dam that supplies up to six feet

of Lake Tahoe’s water flow into the outlet of the Truckee

River. The U.S.

Bureau of Reclamation

controls water

diversion into the Truckee, which is used for

irrigation

,

power, and recreational purposes throughout Nevada.

Tahoe and Crater Lake are the only two large alpine

lakes remaining in the United States. Visitors have expressed

their awe of the lake’s beauty since it was discovered by

General John Fre

´

mont in 1844. Mark Twain wrote that it

was “the fairest sight the whole Earth affords.”

The arrival of Europeans in the Tahoe area was quickly

followed by environmental devastation. Between 1870 and

1900, forests around the lake were heavily logged to provide

timber for the mine shafts of the Comstock Lode. While

this

logging

dramatically altered the area’s appearance for

years, the natural

environment

eventually recovered and no

long-term logging-related damage to the lake can now be

detected.

The same can not be said for a later assault on the

lake’s environment. Shortly after World War II, people be-

gan moving into the area to take advantage of the region’s

natural wonders—the lake itself and superb snow skiing—

as well as the young casino business on the Nevada side of

the lake. The 1960 Winter Olympics, held at Squaw Valley,

placed Tahoe’s recreational assets in the international spot-

light. Lakeside population grew from about 20,000 in 1960

to more than 65,000 today, with an estimated tourist popula-

tion of 22 million annually.

The impact of this rapid

population growth

soon

became apparent in the lake itself. Early records showed

that the lake was once clear enough to allow

visibility

to a

depth of about 130 ft (40 m). By the late 1960s, that figure

had dropped to about 100 ft (30 m).

Tahoe is now undergoing eutrophication at a fairly

rapid rate. Algal growth is being encouraged by sewage and

fertilizer

produced by human activities. Much of the area’s

natural

pollution

controls, such as trees and plants, have

been removed to make room for residential and commercial

development. The lack of significant flow into and out of

807

the lake also contributes to a favorable environment for algal

growth.

Efforts to protect the pristine beauty of Lake Tahoe

go back at least to 1912. Three efforts were made during

that decade to have the lake declared a

national park

, but

all failed. By 1958, concerned conservationists had formed

the Lake Tahoe Area Council to “promote the preservation

and long-range development of the Lake Tahoe basin.” The

Council was followed by other organizations with similar

objectives, the League to Save Lake Tahoe among them.

An important step in resolving the conflict between

preservationists and developers occurred in 1969 with the

creation of the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA).

The agency was the first and only

land use

commission

with authority in more than one state. It consisted of fourteen

members, seven appointed by each of the governors of the

two states involved, California and Nevada. For more than

a decade, the agency attempted to write a land-use plan that

would be acceptable to both sides of the dispute. The conflict

became more complex when the California Attorney Gen-

eral, John Van de Kamp, filed suit in 1985 to prevent TRPA

from granting any further permits for development. Devel-

opers were outraged but lost all of their court appeals.

By 2000, the strain of tourism, development, and non-

point

automobile

pollution was having a visible impact on

Lake Tahoe’s legendary deep blue surface. A study released

by the University of California—Davis and the University

of Nevada—Reno reported that visibility in the lake had

decreased to 70 ft (21 m), an average decline of a foot a year

since the 1960s. As part of a renewed effort to reverse Tahoe’s

environmental decline, President Clinton signed the Lake

Tahoe Restoration Act into law in late 2000, authorizing

$300 million towards restoration of

water quality

in Lake

Tahoe over a period of 10 years. See also Algal bloom; Cul-

tural eutrophication; Environmental degradation; Fish kills;

Sierra Club; Water pollution

[David E. Newton and Paula Anne Ford-Martin]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Strong, Douglas. Tahoe: From Timber Barons to Ecologists.Lincoln, NE:

Bison Books, 1999.

O

THER

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service. Lake

Tahoe Basin Management Unit. [cited July 8, 2002]. <http://

www.r5.fs.fed.us/ltbmu>.

University of California-Davis. Tahoe Research Group. [cited July 8, 2002].

<http://trg.ucdavis.edu/default.html>.

United States Geological Survey (USGS) Lake Tahoe Data Clearinghouse.

Lake Tahoe Data Clearinghouse. [cited July 8, 2002]. <http://tahoe.usgs.gov/

intro.html>.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Lake Washington

Lake Washington

One of the great messages to come out of the environmental

movement of the 1960s and 1970s is that, while humans

can cause

pollution

, they can also clean it up. Few success

stories illustrate this point as clearly as that of Lake Washing-

ton. Lake Washington lies along the state of Washington’s

west coastline, near the city of Seattle. It is 24 miles (39

km) from north to south and its width varies from 2–4 miles

(3–6 km).

For the first half of this century, Lake Washington

was clear and pristine, a beautiful example of the Northwest’s

spectacular natural scenery. Its shores were occupied by ex-

tensive wooded areas and a few small towns with populations

of no more than 10,000. The lake’s purity was not threatened

by Seattle, which dumped most of its wastes into Elliot Bay,

an arm of Puget Sound. This situation changed rapidly

during and after World War II. In 1940, the spectacular

Lake Washington Bridge was built across the lake, joining

its two facing shores with each other and with Seattle. Popu-

lation along the lake began to boom, reaching more than

50,000 by 1950.

The consequence of these changes for the lake are easy

to imagine. Many of the growing communities dumped their

raw sewage directly into the lake or, at best, passed their

wastes though only preliminary treatment stages. By one

estimate, 20 million gallons (76 million liters) of wastes were

being dumped into the lake each day. On average these

wastes still contained about half of their pollutants when

they reached the lake. In less than a decade, the effect of

these practices on lake

water quality

were easy to observe.

Water clarity was reduced from at least 15 ft (4.6 m) to 2.5

ft (0.8 m) and levels of

dissolved oxygen

were so low

that some

species

of fish disappeared. In 1956, W. T.

Edmonson, a zoologist and pollution authority, and two

colleagues reported their studies of the lake. They found

that eutrophication of the lake was taking place very rapidly

as a result of the dumping of domestic wastes into its water.

Solving this problem was especially difficult because

water pollution

is a regional issue over which each individ-

ual community had relatively little control. The solution

appeared to be the creation of a new governmental body that

would encompass all of the Lake Washington communities,

including Seattle. In 1958, a ballot measure establishing

such an agency, known as Metro, was passed in Seattle but

defeated in its suburbs. Six months later, the Metro concept

was redefined to include the issue of sewage disposal only.

This time it passed in all communities.

Metro’s approach to the Lake Washington problem

was to construct a network of sewer lines and

sewage

treatment

plants that directed all sewage away from the

lake and delivered it instead to Puget Sound. The lake’s

808

pollution problems were solved within a few years. By 1975

the lake was back to normal, water clarity returned to 15 ft

and levels of potassium and

nitrogen

in the lake decreased by

more than 60 percent. Lake Washington’s biological oxygen

demand (BOD), a critical measure of water purity, decreased

by 90 percent and fish species that had disappeared were

once again found in the lake. See also Aquatic chemistry;

Cultural eutrophication; Waste management; Water quality

standards

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Edmonson, W. T. “Lake Washington.” In Environmental Quality and

Water Development, edited by C. R. Goodman, et al. San Francisco: W.

H. Freeman, 1973.

———. The Uses of Ecology: Lake Washington and Beyond. Seattle: University

of Washington Press, 1991.

O

THER

Li, Kevin. “The Lake Washington Story.” King County Web Site. May 2,

2001 [June 19,2002]. <http://dnr.metrokc.gov/wlr/waterres/lakes/biola-

ke.htm>.

Lakes

see

Experimental Lakes Area; Lake

Baikal; Lake Erie; Lake Tahoe; Lake

Washington; Mono Lake; National lakeshore

Land degradation

see

Desertification

Land ethic

Land ethic refers to an approach to issues of

land use

that emphasizes

conservation

and respect for our natural

environment

. Rejecting the belief that all

natural re-

sources

should be available for unchecked human exploita-

tion, a land ethic advocates land use without undue distur-

bances of the complex, delicately balanced ecological systems

of which humans are a part. Land ethic,

environmental

ethics

, and ecological ethics are sometimes used inter-

changeably.

Discussions of land ethic, especially in the United

States, usually begin with a reference of some kind to

Aldo

Leopold

. Many participants in the debate over land and

resource use admire Leopold’s prescient and pioneering quest

and date the beginnings of a land ethic to his A Sand County

Almanac, published in 1949. However, Leopold’s earliest

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Land Institute

formulation of his position may be found in “A Conservation

Ethic,” a benchmark essay on ethics published in 1933.

Even recognizing Leopold’s remarkable early contri-

bution, it is still necessary to place his pioneer work in a

larger context. Land ethic is not a radically new invention

of the twentieth century but has many ancient and modern

antecedents in the Western philosophical tradition. The

Greek philosopher Plato, for example, wrote that morality

is “the effective harmony of the whole"—not a bad statement

of an ecological ethic. Reckless exploitation has at times been

justified as enjoying divine sanction in the Judeo-Christian

tradition (man was made master of the creation, authorized

to do with it as he saw fit). However, most Christian thought

through the ages has interpreted the proper human role as

one of careful husbandry of resources that do not, in fact,

belong to humans. In the nineteenth century, the Huxleys,

Thomas and Julian, worked on relating

evolution

and ethics.

The mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote

that “man is not a solitary animal, and so long as social life

survives, self-realization cannot be the supreme principle of

ethics.”

Albert Schweitzer

became famous—at about the

same time that Leopold formulated a land ethic—for teach-

ing reverence for life, and not just human life. Many non-

western traditions also emphasize harmony and a respect for

all living things. Such a context implies that a land ethic

cannot easily be separated from age-old thinking on ethics

in general. See also Land stewardship

[Gerald L. Young and Marijke Rijsberman]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bormann, F. H., and S. R. Kellert, eds. Ecology, Economics, Ethics: The

Broken Circle. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991.

Kealey, D. A. Revisioning Environmental Ethics. Albany: State University

of New York Press, 1989.

Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1949.

Nash, R. F. The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics. Madi-

son: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

Rolston, H. Environmental Ethics. Philadelphia: Temple University

Press, 1988.

Turner, F. “A New Ecological Ethics.” In Rebirth of Value. Albany: State

University of New York Press, 1991.

O

THER

Callicott, J. Baird. “The Land Ethic: Key Philosophical and Scientific

Challenges.” October 15, 1998 [June 19, 2002]. <http://www.orst.edu/

dept/philosophy/ideas/leopold/presentations/callicott/pres-03.html>.

Land Institute

Founded in 1976 by Wes and Dana Jackson, the Land

Institute is both an independent agricultural research station

809

and a school devoted to exploring and developing alternative

agricultural practices. Located on the Smoky Hill River near

Salina, Kansas, the Institute attempts—in Wes Jackson’s

words—to “make

nature

the measure” of human activities

so that humans “meet the expectations of the land,” rather

than abusing the land for human needs. This requires a

radical rethinking of traditional and modern farming meth-

ods. The aim of the Land Institute is to find “new roots for

agriculture” by reexamining its traditional assumptions.

In traditional tillage farming, furrows are dug into

the

topsoil

and seeds planted. This leaves precious topsoil

exposed to

erosion

by wind and water. Topsoil loss can be

minimized but not eliminated by

contour plowing

, the

use of windbreaks, and other means. Although critical of

traditional tillage agriculture, Jackson is even more critical of

the methods and machinery of modern industrial agriculture,

which in effect trades topsoil for high crop yields (roughly

one bushel of topsoil is lost for every bushel of corn har-

vested). It also relies on plant monocultures—genetically

uniform strains of corn, wheat, soybeans, and other crops.

These crops are especially susceptible to disease and insect

infestations and require extensive use of pesticides and herbi-

cides which, in turn, kill useful creatures (for example, worms

and birds), pollute streams and

groundwater

, and produce

other destructive side effects. Although spectacularly suc-

cessful in the short run, such an agriculture is both non-

sustainable and self-defeating. Its supposed strengths—its

productivity, its efficiency, its economies of scale—are also its

weaknesses. Short-term gains in production do not, Jackson

argues, justify the longer term depletion of topsoil, the dimi-

nution of genetic diversity, and such social side-effects as the

disappearance of small family farms and the abandonment of

rural communities.

If these trends are to be questioned—much less slowed

or reversed—a practical, productive, and feasible alternative

agriculture must be developed. To develop such a workable

alternative is the aim of the Land Institute. The Jacksons

and their associates are attempting to devise an alternative

vision of agricultural possibilities. This begins with the im-

portant but oft-neglected truism that agriculture is not self-

contained but is intertwined with and dependent on nature.

The Institute explores the feasibility of alternative farming

methods that might minimize or even eliminate the planting

and harvesting of annual crops, turning instead to “herba-

ceous perennial seed-producing polycultures” that protect

and bind topsoil. Food grains would be grown in pasture-

like fields and intermingled with other plants that would

replenish lost

nitrogen

and other nutrients, without relying

on chemical fertilizers. Covered by a rooted living net of

diverse plant life, the

soil

would at no time be exposed to

erosion and would be aerated and rejuvenated by natural

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Land reform

means. And the farmer, in symbiotic partnership, would

take nature as the measure of his methods and results.

The experiments at the Land Institute are intended

to make this vision into a workable reality. It is as yet too

early to tell exactly what these continuing experiments might

yield. But the re-visioning of agriculture has already begun

and continues at the Land Institute.

[Terence Ball]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

The Land Institute, 2440 E. Water Well Road, Salina, KS USA 67401

(785) 823-5376, Fax: (785) 823-8728, Email: thelandweb@

landinstitute.org, <http://www.landinstitute.org>

Land reform

Land reform is a social and political restructuring of the

agricultural systems through redistribution of land. Success-

ful land reform policies take into account the political, social,

and economic structure of the area.

In agrarian societies, large landowners typically control

the wealth and the distribution of food. Land reform policies

in such societies allocate land to small landowners, to farm

workers who own no land, to collective farm operations, or

to state farm organizations. The exact nature of the allocation

depends on the motivation of those initiating the changes.

In areas where absentee ownership of farmland is common,

land reform has become a popular method for returning the

land to local ownership. Land reforms generally favor the

family-farm concept, rather than absentee landholding.

Land reform is often undertaken as a means of achiev-

ing greater social equality, but it can also increase agricultural

productivity and benefit the

environment

. A tenant farmer

may have a more emotional and protective relation to the

land he works, and he may be more likely to make agricultural

decisions that benefit the

ecosystem

. Such a farmer might,

for instance, opt for natural

pest

control. An absentee owner

often does not have the same interest in

land stewardship

.

Land reform does have negative connotations and is

often associated with the state collective farms under com-

munism. Most proponents of land reform, however, do not

consider these collective farms good examples, and they ar-

gue that successful land reform balances the factors of pro-

duction so that the full agricultural capabilities of the land

can be realized. Reforms should always be designed to in-

crease the efficiency and economic viability of farming.

Land reform is usually more successful if it is enacted

with agrarian reforms, which may include the use of agricul-

tural extension agents, agricultural cooperatives, favorable

labor legislation, and increased public services for farmers,

810

such as health care and education. Without these measures

land reform usually falls short of redistributing wealth and

power, or fails to maintain or increase production. See also

Agricultural pollution; Sustainable agriculture; Sustainable

development

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Mengisteab, K. Ethiopia: Failure of Land Reform and Agricultural Crisis.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1990.

P

ERIODICALS

Perney, L. “Unquiet on the Brazilian Front.” Audubon 94 (January-February

1992): 26–9.

Land stewardship

Little has been written explicitly on the subject of land

stewardship. Much of the literature that does exist is limited

to a biblical or theological treatment of stewardship. How-

ever, literature on the related ideas of sustainability and the

land ethic

has expanded dramatically in recent years, and

these concepts are at the heart of land stewardship.

Webster’s and the Oxford English Dictionary both de-

fine a “steward” as an official in charge of a household,

church, estate, or governmental unit, or one who makes

social arrangements for various kinds of events; a manager

or administrator. Similarly, stewardship is defined as doing

the job of a steward or, in ecclesiastical terms, as “the respon-

sible use of resources,” meaning especially money, time and

talents, “in the service of God.”

Intrinsic in those restricted definitions is the idea of

responsible caretakers, of persons who take good care of

the resources in their charge, including

natural resources

.

“Caretaking” universally includes caring for the material re-

sources on which people depend, and by extension, the land

or

environment

from which those resources are extracted.

Any concept of steward or stewardship must include the

notion of ensuring the essentials of life, all of which derive

from the land.

While there are few works written specifically on land

stewardship, the concept is embedded implicitly and explic-

itly in the writings of many articulate environmentalists. For

example, Wendell Berry, a poet and essayist, is one of the

foremost contemporary spokespersons for stewardship of the

land. In his books, Farming: A Handbook (1970), The Unset-

tling of America (1977), The Gift of Good Land (1981), and

Home Economics (1987), Berry shares his wisdom on caring

for the land and the necessity of stewardship. He finds a

mandate for good stewardship in religious traditions, includ-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Land Stewardship Project

ing Judaism and Christianity: “The divine mandate to use

the world justly and charitably, then, defines every person’s

moral predicament as that of a steward.” Berry, however,

does not leave stewardship to divine intervention. He de-

scribes stewardship as “hopeless and meaningless unless it

involves long-term courage, perseverance, devotion, and

skill” on the part of individuals, and not just farmers. He

suggests that when we lost the skill to use the land properly,

we lost stewardship.

However, Berry does not limit his notion of steward-

ship to a biblical or religious one. He lays down seven rules

of land stewardship—rules of “living right.” These are:

O

using the land will lead to ruin of the land unless it “is

properly cared for;”

O

if people do not know the land intimately, they cannot

care for it properly;

O

motivation to care for the land cannot be provided by

“general principles or by incentives that are merely eco-

nomic;”

O

motivation to care for the land, to live with it, stems from

an interest in that land that “is direct, dependable, and

permanent;”

O

motivation to care for the land stems from an expectation

that people will spend their entire lives on the land, and

even more so if they expect their children and grandchildren

to also spend their entire lives on that same land;

O

the ability to live carefully on the land is limited; owning

too much acreage, for example, decreases the quality of

attention needed to care for the land;

O

a nation will destroy its land and therefore itself if it does

not foster rural households and communities that maintain

people on the land as outlined in the first six rules.

Stewardship implies at the very least then, an attempt

to reconnect to a piece of land. Reconnecting means getting

to know that land as intimately as possible. This does not

necessarily imply ownership, although enlightened owner-

ship is at the heart of land stewardship. People who own land

have some control of it, and effective stewardship requires

control, if only in the sense of enough power to prevent

abuse. But, ownership obviously does not guarantee steward-

ship—great and widespread abuses of land are perpetrated

by owners. Absentee ownership, for example, often means

a lack of connection, a lack of knowledge, and a lack of

caring. And public ownership too often means non-owner-

ship, leading to the “Tragedy of the Commons.” Land own-

ership patterns are critical to stewardship, but no one type

of ownership guarantees good stewardship.

Berry argues that true land stewardship usually begins

with one small piece of land, used or controlled or owned by

an individual who lives on that land. Stewardship, however,

extends beyond any one particular piece of land. It implies

811

knowledge, and caring for, the entire system of which that

land is a part, a knowledge of a land’s context as well as

its content. It also requires understanding the connections

between landowners or land users and the larger communi-

ties of which they are a part. This means that stewardship

depends on interconnected systems of

ecology

and econom-

ics, of politics and science, of sociology and planning. The

web of life that exists interdependent with a piece of land

mandates attention to a complex matrix of connections.

Stewardship means keeping the web intact and functional,

or at least doing so on enough land over a long-enough

period of time to sustain the populations dependent on

that land.

Berry and many other critics of contemporary land-

use patterns and policies claim that little attention is being

paid to maintaining the complex communities on which

sustenance, human and otherwise, depends. Until holistic,

ecological knowledge becomes more of a basis for economic

and political decision-making, they assert, stewardship of

the critical land-base will not become the norm. See also

Environmental ethics; Holistic approach; Land use; Sustain-

able agriculture; Sustainable biosphere; Sustainable devel-

opment

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Byron, W. J. Toward Stewardship: An Interim Ethic of Poverty, Power and

Pollution. New York: Paulist Press, 1975.

de Jouvenel, B. “The Stewardship of the Earth.” In The Fitness of Man’s

Environment. New York: Harper & Row, 1968.

Knight, Richard L., and Peter B. Landres, eds. Stewardship Across Bound-

aries. Washington, DC: Island Press, 1998.

Paddock, J., N. Paddock, and C. Bly. Soil and Survival: Land Stewardship

and the Future of American Agriculture. San Francisco: Sierra Club

Books, 1986.

Land Stewardship Project

The

Land Stewardship

Project (LSP) is a nonprofit organi-

zation based in Minnesota and committed to promoting an

ethic of environmental and agricultural stewardship. The

group believes that the natural

environment

is not an ex-

ploitable resource but a gift given to each generation for

safekeeping. To preserve and pass on this gift to

future

generations

, for the LSP, is both a moral and a practical

imperative.

Founded in 1982, the LSP is an alliance of farmers

and city-dwellers dedicated both to preserving the small

family farm and practicing

sustainable agriculture

. Like

Wendell Berry and

Wes Jackson

(with whom they are

affiliated), the LSP is critical of conventional agricultural

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Land trusts

practices that emphasize plant monocultures, large acreage,

intensive tillage, extensive use of herbicides and pesticides,

and the economies of scale that these practices make possible.

The group believes that agriculture conducted on such an

industrial scale is bound to be destructive not only of the

natural environment but of family farms and rural communi-

ties as well. The LSP accordingly advocates the sort of

smaller scale agriculture that, in Berry’s words, “depletes

neither

soil

, nor people, nor communities.”

The LSP sponsors legislative initiatives to save farm-

land and

wildlife habitat

, to limit

urban sprawl

and pro-

tect family farms, and to promote sustainable agricultural

practices. It supports educational and outreach programs to

inform farmers, consumers, and citizens about agricultural

and environmental issues. The LSP also publishes a quarterly

Land Stewardship Letter and distributes video tapes about

sustainable agriculture and other environmental concerns.

[Terence Ball]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

The Land Stewardship Project, 2200 4th Street, White Bear Lake, MN

USA 55110 (651) 653-0618, Fax: (651) 653-0589, Email:

lspwbl@landstewardshipproject.org, <http://www.landstewardshipproject.

org>

Land trusts

A land trust is a private, legally incorporated, nonprofit

organization that works with property owners to protect

open land through direct, voluntary land transactions. Land

trusts come in many varieties, but their intent is consistent.

Land trusts are developed for the purpose of holding land

against a development plan until the public interest can be

ascertained and served. Some land trusts hold land open

until public entities can purchase it. Some land trusts pur-

chase land and manage it for the common good. In some

cases land trusts buy development rights to preserve the land

area for

future generations

while leaving the current use

in the hands of private interests with written documentation

as to how the land can be used. This same technique can

be used to adjust

land use

so that some part of a parcel

is preserved while another part of the same parcel can be

developed, all based on land sensitivity.

There is a hierarchy of land trusts. Some trusts protect

areas as small as neighborhoods, forming to address one

land use issue after which they disband. More often, land

trusts are local in nature but have a global perspective with

regard to their goals for future land protection. The big

national trusts are names that we all recognize such as the

Conservation Fund,

The Nature Conservancy

, the

Ameri-

812

can Farmland Trust

, and the Trust for

Public Land

. The

Land Trust Alliance coordinates the activities of many land

trusts. Currently, there are over 1,200 local and regional

land trusts in the United States. Some of these trusts form

as a direct response to citizen concerns about the loss of

open space. Most land trusts evolve out of citizen’s concerns

over the future of their state, town, and neighborhood. Many

are preceded by failures on the part of local governments to

respond to stewardship mandates by the voters.

Land trusts work because they are built by concerned

citizens and funded by private donations with the express

purpose of securing the sustainability of an acceptable quality

of life. Also, land trusts are effective because they purchase

land (or development rights) from local people for local

needs. Transactions are often carried out over a kitchen table

with neighbors discussing priorities. In some cases the trust’s

board of directors might be engaged in helping a citizen to

draw up a will leaving farmland or potential

recreation

land

to the community. This home rule concept is the backbone

of the land trust movement. Additionally, land trusts gain

strength from public/private partnerships that emerge as a

result of shared objectives with governmental agencies. If

the work of the land trust is successful, part of the outcome

is an enhanced ability to cooperate with local government

agencies. Agencies learn to trust the land trust staff and

begin to rely on the special expertise that grows within a

land trust organization. In some cases the land trust gains

both opportunities and resources as a result of its partnership

with governmental agencies. This public/private partnership

benefits citizens as projects come together and land use

options are retained for current and future generations.

Flexibility is an important and essential quality of a

land trust that enables it to be creative. Land trusts can have

revolving accounts, or lines of credit, from banks that allow

them to move quickly to acquire land. Compensation to

landowners who agree to work with the trust may come in

the form of extended land use for the ex-owner, land trades,

tax compensation, and other compensation packages. Often

some mix of protection and compensation packages will be

created that a governmental agency simply does not have

the ability to implement. A land trust’s flexibility is its most

important attribute. Where a land trust can negotiate land

acquisition based on a discussion among the board members,

a governmental agency would go through months or even

years of red tape before an offer to buy land for the public

domain could be made. This quality of land trusts is one

reason why many governmental agencies have built relation-

ships with land trusts in order to protect land that the agency

deems sensitive and important.

There are some limiting factors constraining what land

trusts can do. For the more localized trusts, limited volunteer

staff and extremely limited budgets cause fund raising to

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Land trusts

become a time-consuming activity. Staff turnover can be

frequent so that a knowledge base is difficult to maintain.

In some circumstances influential volunteers can capture a

land trust organization and follow their own agenda rather

than letting the agenda be set by affected stakeholders.

Training is needed for those committed to working

within the legal structure of land trusts. The national Trust for

Public Lands has established training opportunities to better

prepare local land trust staff for the complex negotiations that

are needed to protect public lands. Staff that work with local

citizenry to protect local needs must be aware of the costs and

benefits of land preservation mechanisms. Lease purchase

agreements, limited partnerships, and fee simple transactions

all require knowledge of real estate law. Operating within en-

terprise zones and working with economic development cor-

porations requires knowledge of state and federal programs

that provide money for projects on the urban fringe. In some

cases urban renewal work reveals open space within the urban

core that can be preserved for community gardens or parks if

that land can be secured using HUD funds or other govern-

ment financing mechanisms. A relatively new source of fund-

ing for land acquisition is mitigation funds. These funds are

usually generated as a result of settlements with industry or

governmental agencies as compensation for negative land im-

pacts. Distinguishing among financing mechanisms requires

specialized knowledge that land trust staff need to have avail-

able within their ranks in order to move quickly to preserve

open space and enhance the quality of life for urban dwellers.

On the other hand some landtrusts in rural areas are interested

in conserving farmlands using preserves that allow farmers to

continue to farm while protecting the rural character of the

countryside. Like their urban counterparts, these farmland

preserve programs are complex, and if they are to be effective

the trust needs to employ its solid knowledge of economic

trends and resources.

The work that land trusts do is varied. In some cases

a land trust incorporates as a result of a local threat, such

as a pipeline or railway coming through an area. In some

cases a trust forms to counter an undesirable land use such

as a

landfill

or a

low-level radioactive waste

storage

facility. In other instances, a land trust comes together to

take advantage of a unique opportunity, such as a family

wanting to sell some pristine forest close to town or an

industry deciding to relocate leaving a lovely waterfront loca-

tion with promise as a riverfront recreation area. It is rare

that a land trust forms without a focused need. However,

after the initial project is completed, its success breeds self-

confidence in those who worked on the project and new

opportunities or challenges may sustain the goals of the

fledgling organization.

There are many examples of land trusts and the few

highlighted here may help to enhance understanding of the

813

value of land trust activities and to offer guidance to local

groups wanting to preserve land. One outstanding example

of land trust activity is the Rails to Trails program in Michi-

gan. Under this program, abandoned railroad right of ways

are preserved to create green belts for recreation use through

agreements with the railroad companies. The Trust for Pub-

lic Lands (TPL) has assisted many local land trusts to imple-

ment a wide variety of land acquisition projects. One such

complex agreement took place in Tucson, Arizona. In this

case, the Tucson city government wanted to acquire seven

parcels of land that totaled 40 acres (164 ha). For financial

reasons the city was not able to acquire the land. At that

point the Trust for Public Land was asked to become a

private nonprofit partner and to work with the city to acquire

the land. TPL used its creative expertise to help each of the

landowners make mutually beneficial arrangements with the

city so that a large urban park could become a reality. In

some cases the TPL offered a life tenancy to the current

owners in exchange for a reduced land price. In another case

they offered a five-year tenancy and a job as caretaker, in

exchange for a reduced purchase price. As the community

worked on the future of the park, another landowner who

owned a contiguous parcel stepped forward with an offer to

sell. Each of these transactions was successful because the

land trust was flexible, considerate of the land owners and

up front about the goals of their work, and responsive to

their public partner, the city government.

Our current land trust effort in the United States has

affected the way we protect our sensitive lands, reclaim dam-

aged lands, and respond to local needs. Land trusts conserve

land, guide future planning, educate local citizens and govern-

ment agenciesto a new way of doing business, and do itall with

a minimum amount of confrontation and legal interaction.

These private, non-profit organizations have stepped in and

filled a

niche

in the environmental conservation movement

started in the 1970s and have gotten results through a system

of cooperative and well-informed action.

[Cynthia Fridgen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Diamond, H. L., and P. F. Noonan. Land Use in America: The Report

of the Sustainable Use of Land Project. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy,

Washington, DC: Island Press, 1996.

Endicott, E., ed. Land Conservation Through Public/Private Partnerships.

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Washington DC: Island Press, 1993.

Platt, R. H. Land Use and Society: Geography, Law, and Public Policy.

Washington DC: Island Press, 1996.

O

THER

Land Trust Alliance. 2002 [June 20, 2002]. <http://www.lta.org>.

Trust for Public Land. 2002 [June 20, 2002]. <http://www.tpl.org>.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Land use

Land use

Land is any part of the earth’s surface that can be owned as

property. Land comprises a particular segment of the earth’s

crust and can be defined in specific terms. The location of

the land is extremely important in determining land use and

land value.

Land is limited in supply, and, as our population in-

creases, we have less land to support each person. Land

nurtures the plants and animals that provide our food and

shelter. It is the

watershed

or

reservoir

for our water

supply. Land provides the minerals we utilize, the space on

which we build our homes, and the site of many recreational

activities. Land is also the depository for much of the waste

created by modern society. The growth of human population

only provides a partial explanation for the increased pressure

on land resources. Economic development and a rise in the

standard of living have brought about more demands for the

products of the land. This demand now threatens to erode

the land resource.

We are terrestrial in our activities and as our needs

have diversified, so has land use. Conflicts among the com-

peting land uses have created the need for land-use planning.

Previous generations have used and misused the land as

though the supply was inexhaustible. Today, goals and deci-

sions about land use must take into account and link informa-

tion from the physical and biological sciences with the cur-

rent social values and political realities.

Land characteristics and ownership provide a basis for

the many uses of land. Some land uses are classified as

irreversible, for example, when the application of a particular

land use changes the original character of the land to such

a extent that reversal to its former use is impracticable.

Reversible land uses do not change the

soil

cover or land-

form, and the land manager has many options when oversee-

ing reversible land uses.

A framework for land-use planning requires the recog-

nition that plans, policies, and programs must consider phys-

ical and biological, economical, and institutional factors.

The physical framework of land focuses on the inanimate

resources of soil, rocks and geological features, water, air,

sunlight, and

climate

. The biological framework involves

living things such as plants and animals. A key feature of

the physical and biological framework is the need to maintain

healthy ecological relationships. The land can support many

human activities, but there are limits. Once the resources

are brought to these limits, they can be destroyed and replac-

ing them will be difficult.

The economic framework for land use requires that

operators of land be provided sufficient returns to cover the

cost of production. Surpluses of returns above costs must be

realized by those who make the production decisions and

814

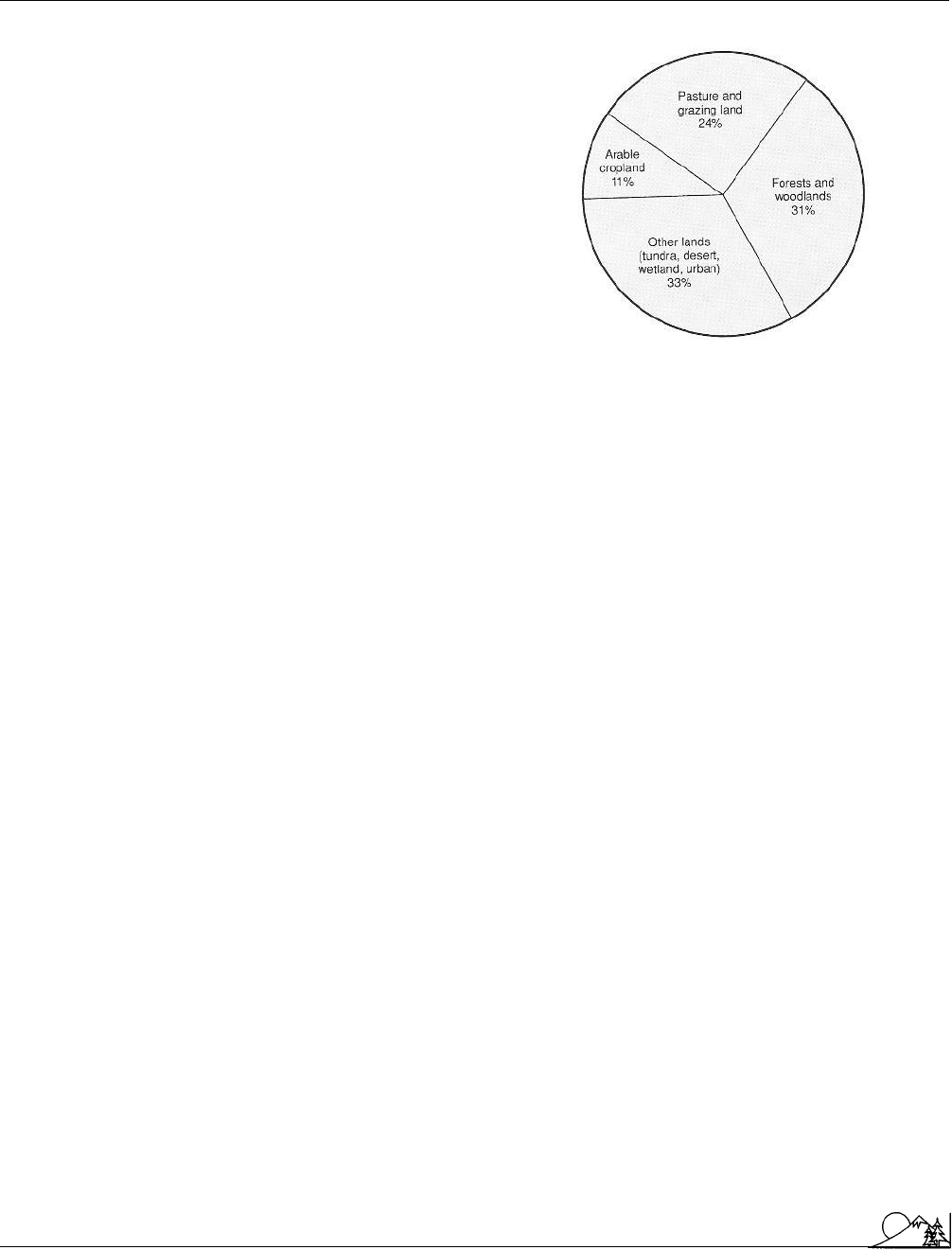

World land use. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

by those who bear the production costs. The economic

framework provides the incentive to use the land in a way

that is economically feasible. The institutional framework

requires that programs and plans be acceptable within the

working rules of society. Plans must also have the support

of current governments. A basic concept of land use is the

right of land—who has the right to decide the use of a given

tract of land. Legal decisions have provided the framework

for land resource protection.

Attitudes play an important role in influencing land

use decisions, and changes in attitudes will often bring

changes in our institutional framework. Recent trends in

land use in the United States show that substantial areas

have shifted to urban and

transportation

uses, state and

national parks, and

wildlife

refuges since 1950. The use of

land has become one of our most serious environmental

concerns. Today’s land use decisions will determine the qual-

ity of our future life styles and

environment

. The land

use planning process is one of the most complex and least

understood domestic concerns facing the nation. Additional

changes in the institutional framework governing land use

are necessary to allow society to protect the most limited

resource on the planet—the land we live on.

[Terence H. Cooper]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Beatty, M. T. Planning the Uses and Management of Land. Series in Agron-

omy, no. 21. Madison, WI: American Standards Association, 1979.

Davis, K. P. Land Use. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976.

Fabos, J. G. Land-Use Planning: From Global to Local Challenge. New York:

Chapman and Hall, 1985.

Lyle, John T., and Joan Woodward. Design for Human Ecosystems: Landscape,

Land Use and Natural Resources. Washington, DC: Island Press, 1999.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Landfill

McHarg, I. L. Design With Nature. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1995.

Silber, Jane, and Chris Maser. Land-Use Planning for Sustainable Develop-

ment. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2000.

Landfill

Surface water, oceans and landfills are traditionally the main

repositories for society’s solid and

hazardous waste

. Land-

fills are located in excavated areas such as sand and gravel

pits or in valleys that are near waste generators. They have

been cited as sources of surface and

groundwater

contami-

nation and are believed to pose a significant health risk

to humans, domestic animals, and

wildlife

. Despite these

adverse effects and the attendant publicity, landfills are likely

to remain a major waste disposal option for the immediate

future.

Among the reasons that landfills remain a popular

alternative are their simplicity and versatility. For example,

they are not sensitive to the shape, size, or weight of a

particular waste material. Since they are constructed of

soil

,

they are rarely affected by the chemical composition of a

particular waste component or by any collective incompati-

bility of co-mingled wastes. By comparison,

composting

and

incineration

require uniformity in the form and chemi-

cal properties of the waste for efficient operation. Landfills

also have been a relatively inexpensive disposal option, but

this situation is rapidly changing. Shipping costs, rising land

prices, and new landfill construction and maintenance re-

quirements contribute to increasing costs.

About 57% of the

solid waste

generated in the United

States still is dumped in landfills. In a sanitary landfill, refuse

is compacted each day and covered with a layer of dirt. This

procedure minimizes odor and litter, and discourages insect

and rodent populations that may spread disease. Although

this method does help control some of the

pollution

gener-

ated by the landfill, the fill dirt also occupies up to 20 percent

of the landfill space, reducing its waste-holding capacity.

Sanitary landfills traditionally have not been enclosed in a

waterproof lining to prevent

leaching

of

chemicals

into

groundwater, and many cases of

groundwater pollution

have been traced to landfills.

Historically landfills were placed in a particular loca-

tion more for convenience of access than for any environ-

mental or geological reason. Now more care is taken in the

siting of new landfills. For example, sites located on faulted

or highly

permeable

rock are passed over in favor of sites

with a less-permeable foundation. Rivers, lakes, floodplains,

and groundwater recharge zones are also avoided. It is be-

lieved that the care taken in the initial siting of a landfill

will reduce the necessity for future clean-up and site

rehabil-

itation

. Due to these and other factors, it is becoming in-

creasingly difficult to find suitable locations for new landfills.

815

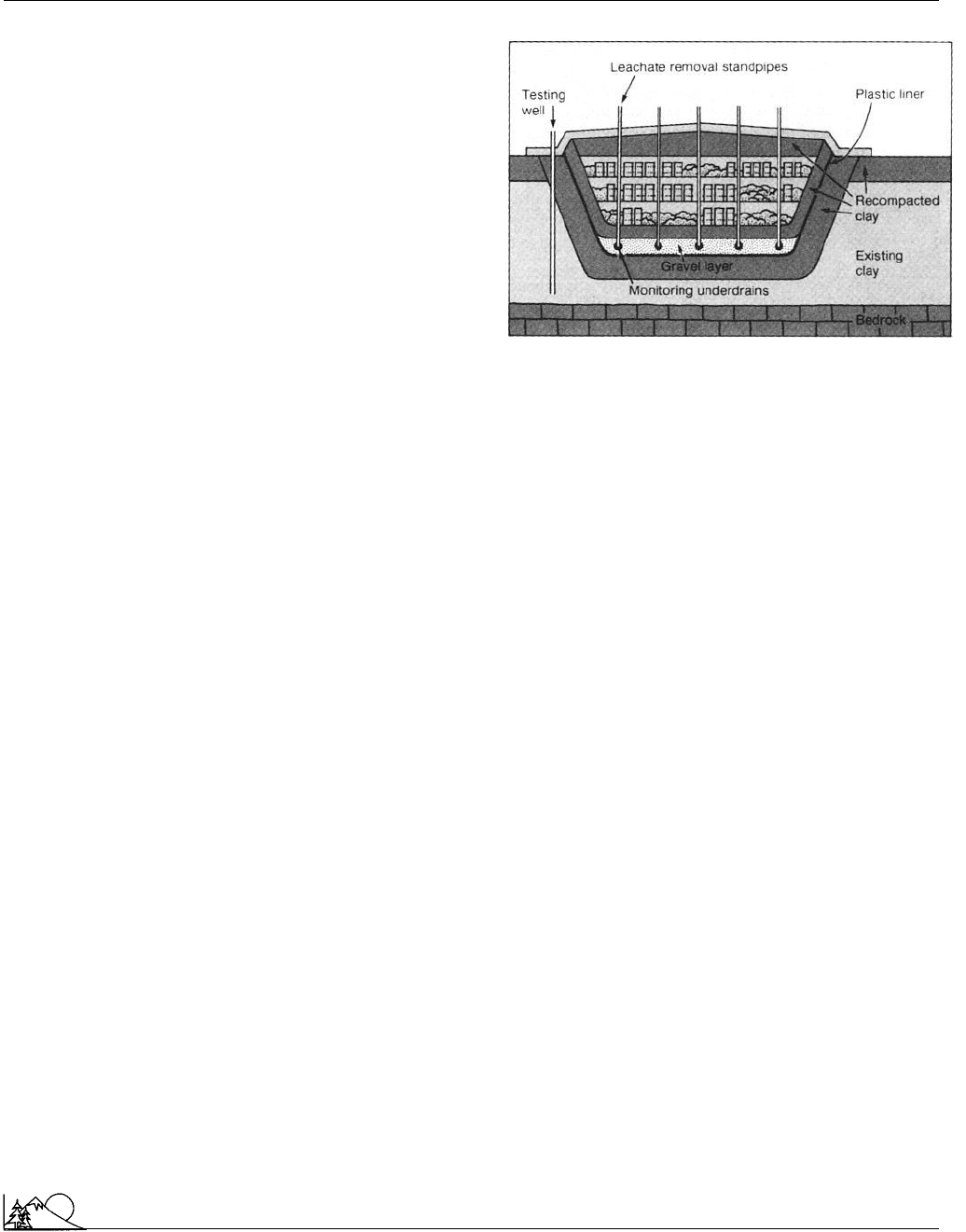

A secure landfill. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by

permission.)

Easily accessible open space is becoming scarce and many

communities are unwilling to accept the siting of a landfill

within their boundaries. Many major cities have already

exhausted their landfill capacity and must export their trash,

at significant expense, to other communities or even to other

states and countries.

Although a number of significant environmental issues

are associated with the disposal of solid waste in landfills,

the disposal of hazardous waste in landfills raises even greater

environmental concerns. A number of urban areas contain

hazardous waste landfills.

Love Canal

is, perhaps, the most

notorious example of the hazards associated with these land-

fills. This Niagara Falls, New York neighborhood was built

over a dump containing 20,000 metric tons of toxic chemical

waste. Increased levels of

cancer

, miscarriages, and

birth

defects

among those living in Love Canal led to the eventual

evacuation of many residents. The events at Love Canal

were also a major impetus behind the passage of the Compre-

hensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Lia-

bility Act in 1980, designed to clean up such sites. The U.

S.

Environmental Protection Agency

estimates that there

may be as many as 2,000 hazardous waste disposal sites in

this country that pose a significant threat to human health

or the

environment

.

Love Canal is only one example of the environmental

consequences that can result from disposing of hazardous

waste in landfills. However, techniques now exist to create

secure landfills that are an acceptable disposal option for

hazardous waste in many cases. The bottom and sides of a

secure landfill contain a cushion of recompacted clay that is

flexible and resistant to cracking if the ground shifts. This

clay layer is impermeable to groundwater and safely contains

the waste. A layer of gravel containing a grid of perforated

drain pipes is laid over the clay. These pipes collect any

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Landscape ecology

seepage

that escapes from the waste stored in the landfill.

Over the gravel bed a thick polyethylene liner is positioned.

A layer of soil or sand covers and cushions this plastic liner,

and the wastes, packed in drums, are placed on top of

this layer.

When the secure landfill reaches capacity it is capped

by a cover of clay, plastic and soil, much like the bottom

layers. Vegetation in planted to stabilize the surface and

make the site more attractive. Sump pumps collect any fluids

that filter through the landfill either from rainwater or from

waste leakage. This liquid is purified before it is released.

Monitoring

wells

around the site ensure that the ground-

water does not become contaminated. In some areas where

the

water table

is particularly high, above-ground storage

may be constructed using similar techniques. Although such

facilities are more conspicuous, they have the advantage of

being easier to monitor for leakage.

Although technical solutions have been found to many

of the problems associated with secure landfills, several non-

technical issues remain. One of these issues concerns the

transportation

of hazardous waste to the site. Some states

do not allow hazardous waste to be shipped across their

territory because they are worried about the possibility of

accidental spills. If hazardous waste disposal is concentrated

in only a few sites, then a few major transportation routes

will carry large volumes of this material. Citizen opposition

to hazardous waste landfills is another issue. Given the past

record of corporate and governmental irresponsibility in

dealing with hazardous waste, it is not surprising that com-

munity residents greet proposals for new landfills with the

NIMBY (

Not In My BackYard

) response. However, the

waste must go somewhere. These and other issues must be

resolved if secure landfills are to be a viable long-term solu-

tion to hazardous waste disposal. See also Groundwater mon-

itoring; International trade in toxic waste; Storage and trans-

portation of hazardous materials

[George M. Fell and Christine B. Jeryan]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bagchi, A. Design, Construction and Monitoring of Landfills. 2nd ed. New

York: Wiley, 1994.

Neal, H. A. Solid Waste Management and the Environment: The Mounting

Garbage and Trash Crisis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1987.

Noble, G. Siting Landfills and Other LULUs. Lancaster, PA: Technomic

Publishing, 1992.

Requirements for Hazardous Waste Landfill Design, Construction and Closure.

Cincinnati: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

“Experimental Landfills Offer Safe Disposal Options.” Journal of Environ-

mental Health 51 (March-April 1989): 217–18.

816

Loupe, D. E. “To Rot or Not; Landfill Designers Argue the Benefits

of Burying Garbage Wet vs. Dry.” Science News 138 (October 6, 1990):

218–19+.

Wingerter, E. J., et al. “Are Landfills and Incinerators Part of the Answer?

Three Viewpoints.” EPA Journal 15 (March-April 1989): 22–26.

Landscape ecology

Landscape

ecology

is an interdisciplinary field that emerged

from several intellectual traditions in Europe and North

America. An identifiable landscape ecology started in central

Europe in the 1960s and in North America in the late

1970s and early 1980s. It became more visible with the

establishment, in 1982, of the International Association of

Landscape Ecology, with the publication of a major text in

the field, Landscape Ecology, by Richard Forman and Michel

Godron in 1984, and with the publication of the first issue

of the association’s journal, Landscape Ecology in 1987.

The phrase ’landscape ecology’ was first used in 1939

by the German geographer, Carl Troll. He suggested that

the “concept of landscape ecology is born from a marriage

of two scientific outlooks, the one geographical (landscape),

the other biological (ecology).” Troll coined the term land-

scape ecology to denote “the analysis of a physico-biological

complex of interrelations, which govern the different area

units of a region.” He believed that “landscape ecology...must

not be confined to the large scale analysis of natural regions.

Ecological factors are also involved in problems of popula-

tion, society, rural settlement,

land use

, transport, etc.”

Landscape has long been a unit of analysis and a con-

ceptual centerpiece of geography, with scholars such as Carl

Sauer and J. B. Jackson adept at “reading the landscape,”

including both the natural landscape of landforms and vege-

tation, and the cultural landscape as marked by human ac-

tions and as perceived by human minds.

Zev Naveh has been working on his own version of

landscape ecology in Israel since the early 1970s. Like Troll,

Naveh includes humans in his conception, in fact enlarges

landscape ecology to a global human

ecosystem

science,

sort of a “bio-cybernetic systems approach to the landscape

and the study of its use by [humans].” He sees landscape

ecology first as a

holistic approach

to biosystems theory,

the centerpiece being “recognition of the total human ecosys-

tem as the highest level of integration,” and, second, as

playing a central role in cultural

evolution

and as a “basis for

interdisciplinary, task-oriented, environmental education.”

Landscape architecture is also to some extent landscape

ecology, since landscape architects design complete vistas,

from their beginnings and at various scales. This concern

with designing and creating complete landscapes from bare

ground can certainly be considered ecological, as it includes

creating or adapting local land forms, planting appropriate