Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Landscape ecology

vegetation, and designing and building various kinds of ’fur-

niture’ and other artifacts on site. The British Landscape

Institute and the British Ecological Society held a joint

meeting in 1983, recognizing “that the time for ecology to

be harnessed for the service of landscape design has arrived.”

The meeting produced the twenty-fourth symposium of the

British Ecological Society titled Ecology and Design in Land-

scape.

Landscape planning can also to some degree be consid-

ered landscape ecology, especially in the ecological approach

to landscape planning developed by Ian McHarg and his

students and colleagues, and the LANDEP, or Landscape

Ecological Planning, approach designed by Ladislav Miklos

and Milan Ruzicka. Both of these ecological planning ap-

proaches are complex syntheses of spatial patterns, ecological

processes, and human needs and wants.

Building on all of these traditions, yet slowly finding

its own identity, landscape ecology is considered by some

as a sub-domain of biological ecology and by others as a

discipline in its own right. In Europe, landscape ecology

continues to be an extension of the geographical tradition

that is preoccupied with human-landscape interactions. In

North America, landscape ecology has emerged as a branch

of biological ecology, more concerned with landscapes as

clusters of interrelated natural ecosystems. The European

form of landscape ecology is applied to land and resource

conservation

, while in North America it focuses on funda-

mental questions of spatial pattern and exchange. Both tradi-

tions can address major environmental problems, especially

the

extinction

of

species

and the maintenance of biological

diversity.

The term landscape, despite the varied traditions and

emerging disciplines described above, remains somewhat in-

determinate, depending on the criteria set by individual re-

searchers to establish boundaries. Some consensus exists on

its general definition in the new landscape ecology, as de-

scribed in the composite form attempted here: a terrestrial

landscape is miles- or kilometers-wide in area; it contains a

cluster of interacting ecosystems repeated in somewhat simi-

lar form; and it is a heterogeneous mosaic of interconnected

land forms, vegetation types, and land uses. As Risser and

his colleagues emphasize, this interdisciplinary area focuses

explicitly on spatial patterns: “Specifically, landscape ecology

considers the development and dynamics of spatial hetereo-

geneity, spatial and temporal interactions and exchanges

across heterogeneous landscapes, influences of spatial heter-

ogeneity on biotic and abiotic processes, and management

of spatial heterogeneity.” Instead of trying to identify homo-

geneous ecosystems, landscape ecology focuses particularly

on the heterogeneous patches and mosaics created by human

disruption of natural systems, by the intermixing of cultural

and natural landscape patterns. The real rationale for a land-

817

scape ecology perhaps should be this acknowledgment of

the heterogeneity of contemporary landscape patterns, and

the need to deal with the patchwork mosaics and intricate

matrices that result from long-term human disturbance,

modification, and utilization of natural systems.

Typical questions asked by landscape ecologists in-

clude these formulated by Risser and his colleagues: “What

formative processes, both historical and present, are respon-

sible for the existing pattern in a landscape?” “How are fluxes

of organisms, of material, and of energy related to landscape

heterogeneity?” “How does landscape heterogeneity affect

the spread of disturbances?” While the first question is simi-

lar to ones long asked in geography, the other two are ques-

tions traditional to ecology, but distinguished here by the

focus on heterogeneity.

Richard Forman, a prominent figure in the evolving

field of landscape ecology, thinks the field has matured

enough for general principles to have emerged; not ecological

laws as such, but principles backed by enough evidence and

examples to be true for 95 percent of landscape analyses.

His 12 principles are organized by four categories: landscapes

and regions; patches and corridors; mosaics; and applica-

tions. The principles outline expected or desirable spatial

patterns and relationships, and how those patterns and rela-

tionships affect system functions and flows, organismic

movements and extinctions, resource protection, and optimal

environmental conditions. Forman claims the principles

“should be applicable for any environmental or societal land-

use objective,” and that they are useful in more effectively

“growing wood, protecting species, locating houses, pro-

tecting

soil

, enhancing game, protecting

water resources

,

providing

recreation

, locating roads, and creating sustain-

able environments.”

Perhaps Andre Corboz provided the best description

when he wrote of “the land as palimpsest:” landscape ecology

recognizes that humans have written large on the land, and

that behind the current writing visible to the eye, there is

earlier writing as well, which also tells us about the patterns

we see. Landscape ecology also deals with gaps in the text and

tries to write a more complete accounting of the landscapes in

which we live and on which we all depend.

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Farina, Almo. Landscape Ecology in Action. New York: Kluwer, 2000.

Forman, R. T. T., and M. G. Landscape Ecology. New York: Wiley, 1986.

Risser, P. G., J. R. Karr, and R. T. T. Forman. Landscape Ecology: Directions

and Approaches. Champaign: Illinois Natural History Survey, 1983.

Tjallingii, S. P., and A. A. de Veer, eds. Perspectives in Landscape Ecology:

Contributions to Research, Planning and Management of Our Environment.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Landslide

Troll, C. Landscape Ecology. Delft, The Netherlands: The ITC-UNESCO

Centre for Integrated Surveys, 1966.

Turner, Monica, R. H. Gardner, and R. V. O’Neill. Landscape Ecology in

Theory and Practice: Patterns and Processes. New York: Springer Verlag, 2001.

Wageningen, The Netherlands: Pudoc, 1982. (Proceedings of the Interna-

tional Congress Organized by the Netherlands Society for Landscape Ecol-

ogy, Veldhoven, The Netherlands, 6-11 April, 1981).

Zonneveld, I. S., and R. T. T. Forman, eds. Changing Landscapes: An

Ecological Perspective. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1990.

P

ERIODICALS

Forman, R. T. T. “Some General Principles of Landscape and Regional

Ecology.” Landscape Ecology (June 1995): 133–142.

Golley, F.B. “Introducing Landscape Ecology.” Landscape Ecology 1, no. 1

(1987): 1–3.

Naveh, Z. “Landscape Ecology as an Emerging Branch of Human Ecosys-

tem Science.” Advances in Ecological Research 12 (1982): 189–237.

Landslide

A general term for the discrete downslope movement of

rock and

soil

masses under gravitational influence along a

failure zone. The term “landslide” can refer to the resulting

land form, as well as to the process of movement. Many

types of landslides occur, and they are classified by several

schemes, according to a variety of criteria. Landslides are

categorized most commonly on basis of geometric form, but

also by size, shape, rate of movement, and water content

or fluidity. Translational, or planar, failures, such as debris

avalanches and earth flows, slide along a fairly straight failure

surface which runs approximately parallel to the ground

surface. Rotational failures, such as rotational slumps, slide

along a spoon shaped failure surface, leaving a hummocky

appearance on the landscape. Rotational slumps commonly

transform into earthflows as they continue down slope.

Landslides are usually triggered by heavy rain or melting

snow, but major earthquakes can also cause landslides.

Land-use control

Land-use control is a relatively new concept. For most of hu-

man history, it was assumed that people could do whatever

they wished with their own property. However, societies have

usually recognized that the way an individual uses private

property can sometimes have harmful affects on neighbors.

Land-use planning has reached a new level of sophisti-

cation in developed countries over the last century. One of

the first restrictions on

land use

in the United States, for

example, was a 1916 New York City law limiting the size

of skyscrapers because of the shadows they might cast on

adjacent property. Within a decade, the federal government

began to act aggressively on land control measures. It passed

the

Mineral Leasing Act

of 1920 in an attempt to control

the exploitation of oil,

natural gas

, phosphate, and potash.

818

It adopted the Standard State Zoning Act of 1922 and the

Standard City Planning Enabling Act of 1928 to promote

the concept of zoning at state and local levels. Since the

1920s, every state and most cities have adopted zoning laws

modeled on these two federal acts.

Often detailed, exhaustive, and complex zoning regu-

lations now control the way land is used in nearly every

governmental unit. They specify, for example, whether land

can be used for single-dwelling construction, multiple-dwell-

ing construction, farming, industrial (heavy or light) devel-

opment, commercial use,

recreation

or some other purpose.

Requests to use land for purposes other than that for which

it is zoned requires a variance or conditional use permit, a

process that is often long, tedious, and confrontational.

Many types of land require special types of zoning.

For example, coastal areas are environmentally vulnerable to

storms, high tides,

flooding

, and strong winds. The federal

government passed laws in 1972 and 1980, the National

Coastal Zone Management Acts, to help states deal with

the special problem of protecting coastal areas. Although

initially slow to make use of these laws, states are becoming

more aggressive about restricting the kinds of construction

permitted along seashore areas.

Areas with special scenic, historic, or recreational value

have long been protected in the United States. The nation’s

first

national park

,

Yellowstone National Park

, was cre-

ated in 1872. Not until 44 years later, however, was the

National Park Service

created to administer Yellowstone

and other parks established since 1872. Today, the National

Park Service and other governmental agencies are responsible

for a wide variety of national areas such as forests, wild

and scenic rivers, historic monuments, trails, battlefields,

memorials, seashores and lakeshores, parkways, recreational

areas, and other areas of special value.

Land-use control does not necessarily restrict usage.

Individuals and organizations can be encouraged to use land

in certain desirable ways. An enterprise zone, for example,

is a specifically designated area in which certain types of

business activities are encouraged. The tax rate might be

reduced for businesses locating in the area or the government

might relax certain regulations there.

Successful land-use control can result in new towns

or planned communities, designed and built from the ground

up to meet certain pre-determined land-use objectives. One

of the most famous examples of a planned community is

Brasilia, the capital of Brazil. The site for a new capital—

an undeveloped region of the country—was selected and a

totally new city was built in the 1950s. The federal govern-

ment moved to the new city in 1960, and it now has a

population of more than 1.5 million. See also Bureau of Land

Management; Riparian rights

[David E. Newton]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Lawn treatment

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Becker, Barbara, Eric D. Kelly, and Frank So. Community Planning: An

Introduction to the Comprehensive Plan. Washington, DC: Milldale Press,

2000.

Newton, D. E. Land Use, A–Z. Hillside, NJ: Enslow Press, 1991.

Platt, Rutherford H. Land Use and Society: Geography, Law, and Public

Policy. Washington, DC: Island Press, 1996.

Latency

Latency refers to the period of time it takes for a disease to

manifest itself within the human body. It is the state of

seeming inactivity that occurs between the instant of stimula-

tion or initiating event and the beginning of response. The

latency period differs dramatically for each stimulation and

as a result, each disease has its unique time period before

symptoms occur.

When pathogens gain entry into a potential host, the

body may fail to maintain adequate immunity and thus per-

mits progressive viral or bacterial multiplication. This time

lapse is also known as the incubation period. Each disease

has definite, characteristic limits for a given host. During

the incubation period, dissemination of the

pathogen

takes

place and leads to the inoculation of a preferred or target

organ. Proliferation of the pathogen, either in a target organ

or throughout the body, then creates an infectious disease.

Botulism, tetanus, gonorrhea, diphtheria, staphylococ-

cal and streptococcal disease, pneumonia, and tuberculosis

are among the diseases that take varied periods of time before

the symptoms are evident. In the case of the childhood

diseases—measles, mumps, and chicken pox—the incuba-

tion period is 14–21 days.

In the case of

cancer

, the latency period for a small

group of transformed cells to result in a tumor large enough

to be detected is usually 10–20 years. One theory postulates

that every cancer begins with a single cell or small group of

cells. The cells are transformed and begin to divide. Twenty

years of cell division ultimately results in a detectible tumor.

It is theorized that very low doses of a

carcinogen

could

be sufficient to transform one cell into a cancerous tumor.

In the case of

AIDS

, an eight- to eleven-year latency

period passes before the symptoms appear in adults. The

length of this latency period depends upon the strength of

the person’s immune system. If a person suspects he or she

has been infected, early blood tests showing HIV antibodies

or antigens can indicate the infection within three months

of the stimulation. The three-month period before the ap-

pearance of HIV antibodies or antigens is called the “window

period.”

In many cases, doctors may fail to diagnose the disease

at first, since AIDS symptoms are so general they may be

819

confused with the symptoms of other, similar diseases.

Childhood AIDS symptoms appear more quickly since

young children have immune systems that are less fully de-

veloped.

[Liane Clorfene Casten]

Lawn treatment

Lawn treatment in the form of pesticides and inorganic

fertilizers poses a substantial threat to the

environment

.

Homeowners in the United States use approximately three

times more pesticides per acre than the average farmer, add-

ing up to some 136 million pounds (61.7 kg)annually. Home

lawns occupy more acreage in the United States than any

agricultural crop, and a majority of the

wildlife pesticide

poisonings tracked by the

Environmental Protection

Agency

(EPA) annually are attributed to

chemicals

used

in lawn care. The use of grass

fertilizer

is also problematic

when it runs off into nearby waterways. Lawn grass in almost

all climates in the United States requires watering in the

summer, accounting for some 40 to 60 percent of the average

homeowner’s water use annually. Much of the water sprin-

kled on lawns is lost as

runoff

. When this runoff carries

fertilizer, it can cause excess growth of algae in downstream

waterways, clogging the surface of the water and depleting

the water of oxygen for other plants and animals. Herbicides

and pesticides are also carried into downstream water, and

some of these are toxic to fish, birds, and other wildlife.

Turf grass lawns are ubiquitous in all parts of the

United States, regardless of the local

climate

. From Alaska

to Arizona to Maine, homeowners surround their houses

with grassy lawns, ideally clipped short, brilliantly green,

and free of weeds. In almost all cases, the grass used is a

hybrid of several

species

of grass from Northern Europe.

These grasses thrive in cool, moist summers. In general,

the United States experiences hotter, dryer summers than

Northern Europe. Moving from east to west across the coun-

try, the climate becomes less and less like that the common

turf grass evolved in. The ideal American lawn is based

primarily on English landscaping principals, and it does not

look like an English lawn unless it is heavily supported with

water.

The prevalence of lawns is a relatively recent phenome-

non in the United States, dating to the late nineteenth

century. When European settlers first came to this country,

they found indigenous grasses that were not as nutritious

for livestock and died under the trampling feet of sheep

and cows. Settlers replaced native grasses with English and

European grasses as fodder for grazing animals. In the late

eighteenth century, American landowners began sur-

rounding their estates with lawn grass, a style made popular

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Lawn treatment

earlier in England. The English lawn fad was fueled by

eighteenth century landscaper Lancelot “Capability” Brown,

who removed whole villages and stands of mature trees and

used sunken fences to achieve uninterrupted sweeps of green

parkland. Both in England and the United States, such lawns

and parks were mowed by hand, requiring many laborers,

or they were kept cropped by sheep or even deer. Small

landowners meanwhile used the land in front of their houses

differently. The yard might be of stamped earth, which could

be kept neatly swept, or it may have been devoted to a small

garden, usually enclosed behind a fence. The trend for houses

set back from the street behind a stretch of unfenced lawn

took hold in the mid-nineteenth century with the growth

of suburbs. Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of New

York City’s Central Park, was a notable suburban planner,

and he fueled the vision of the English manor for the subur-

ban home. The unfenced lawns were supposed to flow from

house to house, creating a common park for the suburb’s

residents. These lawns became easier to maintain with the

invention of the lawn mower. This machine debuted in

England as early as 1830, but became popular in the United

States after the Civil War. The first patent for a lawn sprin-

kler was granted in the United States in 1871. These devel-

opments made it possible for middle class home owners to

maintain lush lawns themselves.

Chemicals for lawn treatment came into common use

after World War II. Herbicides such as

2,4-D

were used

against broadleaf weeds. The now-banned DDT was used

against insect pests. Homeowners had previously fertilized

their lawns with commercially available organic formulations

like dried manure, but after World War II inorganic, chemi-

cal-based fertilizers became popular for both agriculture and

lawns and gardens. Lawn care companies such as Chemlawn

and Lawn Doctor originated in the 1960s, an era when

homeowners were confronted with a bewildering array of

chemicals deemed essential to a healthy lawn. Rachel Car-

son’s 1962 book Silent Spring raised an alarm about the

prevalence of lawn chemicals and their environmental costs.

Carson explained how the insecticide DDT builds up in the

food chain, passing from insects and worms to fish and

small birds that feed on them, ultimately endangering large

predators like the eagle. DDT was banned in 1972, and

some lawn care chemicals were restricted. Nevertheless, the

lawn care industry continued to prosper, offering services

such as combined seeding,

herbicide

, and fertilizer at several

intervals throughout the growing season. Lawn care had

grown to a $25 billion industry in the United States by the

1990s. Even as the perils of particular lawn chemicals became

clearer, it was difficult for homeowners to give them up.

Statistics

from the United States National

Cancer

Institute

show that the incidence of childhood

leukemia

is 6.5%

greater in familes that use lawn pesticides than in those who

820

do not. In addition, 32 of the 34 most widely used lawn care

pesticides have not been tested for health and environmental

issues. Because some species of lawn grasses grow poorly in

some areas of the United States, it does not thrive without

extra water and fertilizer. It is vulnerable to insect pests,

which can be controlled with pesticides, and if a weed-free

lawn is the aim, herbicides are less labor-intensive than

digging out dandelions one by one.

Some common pesticides used on lawns are acephate,

bendiocarb, and

diazinon

. Acephate is an

organophos-

phate

insecticide which works by damaging the insect’s

nervous system. Bendiocarb is called a carbamate insecticide,

sold under several brand names, which works in the same

way. Both were first developed in the 1940s. These will kill

many insects, not only pests such as leafminers, thrips, and

cinch bugs, but also beneficial insects, such as bees. Bendio-

carb is also toxic to earthworms, a major food source for

some birds. Birds too can die from direct exposure to bendio-

carb, as can fish. Both these chemicals can persist in the

soil

for weeks. Diazinon is another common pesticide used

by homeowners on lawns and gardens. It is toxic to humans,

birds, and other wildlife, and it has been banned for use on

golf courses

and turf farms. Nevertheless, homeowners may

use it to kill

pest

insects such as

fire ants

. Harmful levels

of diazinon and were found in metropolitan storm water

systems in California in the early 1990s, leached there from

orchard run-off. Diazinon is responsible for about half of

all reported wildlife poisonings involving lawn and garden

chemicals.

Common lawn and garden herbicides appear to be

much less toxic to humans and animals than pesticides. The

herbicide 2,4-D, one of the earliest herbicides used in this

country, can cause skin and eye irritation to people who

apply it, and it is somewhat toxic to birds. It can be toxic

to fish in some formulations. Although contamination with

2,4-D has been found in some urban waterways, it has only

been in trace amounts not thought to be harmful to humans.

Glyphosate is another common herbicide, sold under several

brand names, including the well-known Roundup. It is con-

sidered non-toxic to humans and other animals. Unike 2,4-

D, which kills broadleaf plants, glyphosate is a broad spec-

trum herbicide used to control control a great variety of

annual, biennial, and perennial grasses, sedges, broad leafed

weeds and woody shrubs.

Common lawn and garden fertilizers are generally not

toxic unless ingested in sufficient doses, yet they can have

serious environmental effects. Run-off from lawns can carry

fertilizer into nearby waterways. The

nitrogen

and

phos-

phorus

in the fertilizer stimulates plant growth, principally

algae and microscopic plants. These tiny plants bloom, die,

and decay. Bacteria that feed off plant decay then also un-

dergo a surge in population. The overabundant bacteria con-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

LD

50

sume oxygen, leading to oxygen-depleted water. This condi-

tion is called hypoxia. In some areas, fertilized run-off from

lawns is as big a problem as run-off from agricultural fields.

Lawn fertilizer is thought to be a major culprit in

pollution

of the

Everglades

in Florida. In 2001 the Minnesota legisla-

ture debated a bill to limit homeowners’ use of phosphorus

in fertilizers because of problems with algae blooms on the

state’s lakes.

There are several viable alternatives to the use of

chemicals for lawn care. Lawn care companies often recom-

mend multiple applications of pesticides, herbicides, and

fertilizers, but an individual lawn may need such treatment

on a reduced schedule. Some insects such as thrips and

mites are suceptible to insecticidal soaps and oils, which

are not long-lasting in the environment. These could be

used in place of diazinon, acephate and other pesticides.

Weeds can be pulled by hand, or left alone. Homeowners

can have their lawn evaluated and their soil tested to

determine how much fertilizer is needed. Slow-release

fertilizers or organic fertilizers such as compost or seaweed

emulsion do not give off such a large concentration of

nutrients at once, so these are gentler on the environment.

Another way to cut back on the excess water and chemicals

used on lawns is to reduce the size of the lawn. The

lawn can be bordered with shrubbery and perennial plants,

leaving just enough open grass as needed for

recreation

.

Another alternative is to replace non-native turf grass with

a native grass. Some native grasses stay green all summer,

can be mown short, and look very much like a typical

lawn. Native buffalo grass (Buchloe dactyloides) has been

used successfully for lawns in the South and Southwest.

Other native grass species are adapted to other regions.

Another example is blue grama grass (Bouteloua gracilis),

native to the Great Plains. This grass is tolerant of extreme

temperatures and very little rainfall. Some native grasses

are best left unmowed, and in some regions homeowners

have replaced their lawns with native grass prairies or

meadows. In some cases, homeowners have done away

with their lawns altogether, using stone or bark

mulch

in its place, or planting a groundcover plant like ivy or

wild ginger. These plants might grow between trees, shrubs

and perennials, creating a very different look than the

traditional green carpet.

For areas with water shortages, or for those who are

concerned about conserving

natural resources

, xeriscape

landscaping should be considered. Xeriscape comes from the

Greek word xeros, meaning dry. Xeriscaping takes advantage

of using plants, such as cacti and grasses, such as Mexican

feather grass and blue oat grass that thrive in

desert

condi-

tions. Xeriscaping can also include rock gardening as part

of the overall landscape plan.

[Angela Woodward]

821

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bormann, F. Herbert, Diana Balmori, and Gordon T. Geballe. Redesigning

the American Lawn. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993.

Jenkins, Virginia Scott. The Lawn: A History of an American Obsession.Wash-

ington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press: 1994.

Stein, Sara. Planting Noah’s Garden: Further Adventures in Backyard Ecology.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1997.

Wasowski, Andy, and Sally Wasowski. The Landscaping Revolution. Chi-

cago: Contemporary Books, 2000.

P

ERIODICALS

Bourne, Joel. “The Killer in Your Yard.” Audobon (May-June 2000): 108.

“Easy Lawns.” Brooklyn Botanic Garden Handbook 160 (Fall 1999).

Simpson, Sarah. “Shrinking the Dead Zone.” Scientific American (July

2001): 18.

Stewart, Doug. “Our Love Affair with Lawns.” Smithsonian (April

1999): 94.

Xeriscaping Tips Page. 2002 [cited June 18, 2002]. <http://ct.essortment.-

com/xeroscaping_rksh.htm>.

LDC

see

Less developed countries

LD

50

LD

50

is the dose of a chemical that is lethal to 50 percent

of a test population. It is therefore a measure of a particular

median response which, in this case, is death. The term is

most frequently used to characterize the response of animals

such as rats and mice in acute toxicity tests. The term is

generally not used in connection with aquatic or inhalation

toxicity tests. It is difficult, if not impossible, to determine

the dosage of an animal in such tests; results are most com-

monly represented in terms of lethal concentrations (LC),

which refer to the concentration of the substance in the air

or water surrounding an animal.

In LD testing, dosages are generally administered by

means of injection, food, water, or forced feeding. Injections

are used when an animal is to receive only one or a few

dosages. Greater numbers of injections would disturb the

animal and perhaps generate some false-positive types of

responses. Food or water may serve as a good medium for

administering a chemical, but the amount of food or water

wasted must be carefully noted. Developing a healthy diet

for an animal which is compatible with the chemical to be

tested can be as much art as science. The chemical may

interact with the foods and become more or less toxic, or it

may be objectionable to the animal due to taste or odor.

Rats are often used in toxicity tests because they do not have

the ability to vomit. The investigator therefore has the option

of gavage, a way to force-feed rats with a stomach tube or

other device when a chemical smells or tastes bad.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Leaching

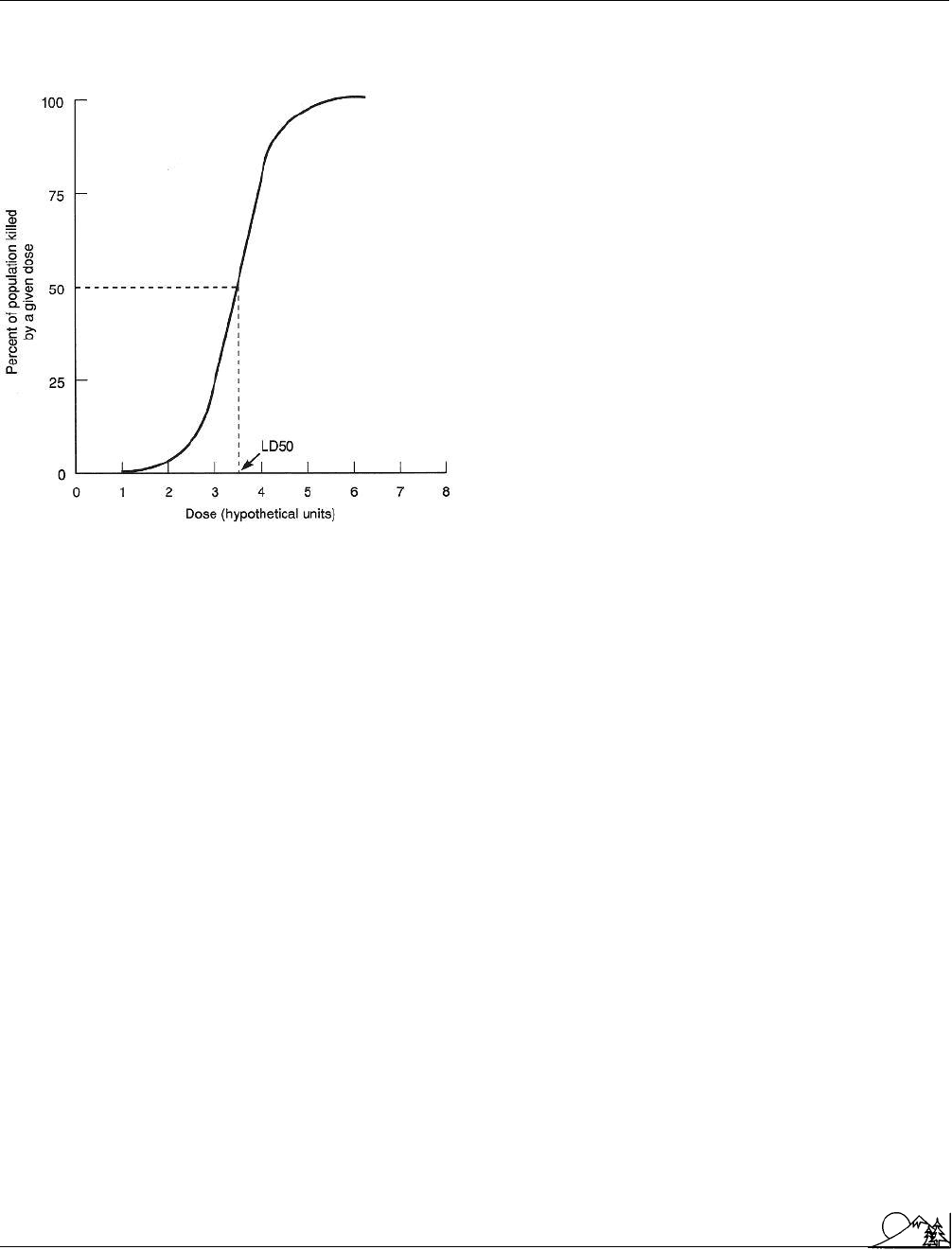

A chart showing the increased dose of LD

50

.

(McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

Toxicity and LD

50

are inversely proportional, which

means that high toxicity is indicated by a low LD

50

and vice

versa. LD

50

is a particular type of effective dose (ED) for

50 percent of a population (ED

50

). The midpoint (or effect

on half of the population) is generally used because some

individuals in a population may be highly resistant to a

particular toxicant, making the dosage at which all individu-

als respond a misleading data point. Effects other than death,

such as headaches or dizziness, might be examined in some

tests, so EDs would be reported instead of LDs. One might

also wish to report the response of some other percent of

the test population, such as the 20 percent response (LD

20

or ED

20

) or 80 percent response (LD

80

or ED

80

).

The LD is expressed in terms of the mass of test

chemical per unit mass of the test animals. In this way, dose

is normalized so that the results of tests can be analyzed

consistently and perhaps extrapolated to predict the response

of animals that are heavier or lighter. Extrapolation of such

data is always questionable, especially when extrapolating

from animal response to human response, but the system

appears to be serving us well. However, it is important to

note that sometimes better dose-response relations and ex-

trapolations can be derived through normalizing dosages

based on surface area or the weight of target organs. See also

822

Bioassay; Dose response; Ecotoxicology; Hazardous mate-

rial; Toxic substance

[Gregory D. Boardman]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Casarett, L. J., J. Doull, and C. D. Klaassen, eds. Casarett and Doull’s

Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons. 6th ed. New York: McGraw

Hill, 2001.

Hodgson, E., R. B. Mailman, and J. E. Chambers. Dictionary of Toxicology.

2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1997.

Lu, F. C. Basic Toxicology: Fundamentals, Target Organs, and Risk Assessment.

3rd ed. Hebron, KY: Taylor & Francis, 1996.

Rand, G. M., ed. Fundamentals of Aquatic Toxicology: Effects, Environmental

Fate, and Risk Assessment. 2nd ed. Hebron, KY: Taylor & Francis, 1995.

Leachate

see

Contaminated soil; Landfill

Leaching

The process by which soluble substances are dissolved out

of a material. When rain falls on farmlands, for example, it

dissolves weatherable minerals, pesticides, and fertilizers as

it soaks into the ground. If enough water is added to the

soil

to fill all the pores, then water carrying these dissolved

materials moves to the groundwater—the soil becomes

leached. In soil chemistry, leaching refers to the process by

which nutrients in the upper layers of soil are dissolved out

and carried into lower layers, where they can be a valuable

nutrient

for plant roots. Leaching also has a number of

environmental applications. For example, toxic

chemicals

and radioactive materials stored in sealed containers under-

ground may leach out if the containers break open over time.

See also Landfill; Leaking underground storage tank

Lead

One of the oldest metals known to humans, lead compounds

were used by Egyptians to glaze pottery as far back as 7000

B.C.

The toxic effects of lead also have been known for many

centuries. In fact, the Romans limited the amount of time

slaves could work in lead mines because of the element’s

harmful effects. Some consequences of lead

poisoning

are

anemia

, headaches, convulsions, and damage to the kidneys

and central nervous system. The widespread use of lead in

plumbing,

gasoline

, and lead-acid batteries, for example,

has made it a serious

environmental health

problem. Bans

on the use of lead in motor fuels and paints attempt to deal

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Lead management

with this problem. See also Heavy metals and heavy metal

poisoning; Lead shot

Lead management

Lead

, a naturally occurring bluish gray metal, is extensively

used throughout the world in the manufacture of storage

batteries,

chemicals

including paint and

gasoline

, and vari-

ous metal products including sheet lead, solder, pipes, and

ammunition. Due to its widespread use, large amounts of

lead exist in the

environment

, and substantial quantities of

lead continue to be deposited into air, land, and water. Lead

is a poison that has many adverse effects, and children are

especially susceptible. At present, the production, use, and

disposal of lead are regulated with demonstrably effective

results. However, because of its previous widespread use and

persistence in the environment, lead exposure is a pervasive

problem that affects many populations. Effective manage-

ment of lead requires an understanding of its effects, blood

action levels, sources of exposure, and policy responses, topics

reviewed in that order.

Effects of Lead

Lead is a strong toxicant that adversely affects many

systems in the body. Severe lead exposures can cause brain

and kidney damage to adults and children, coma, convul-

sions, and death. Lower levels, e.g., lead concentrations in

blood (PbB) below 50 g/dL, may impair hemoglobin syn-

thesis, alter the central and peripheral nervous systems, cause

hypertension, affect male and female reproductive systems,

and damage the developing fetus. These effects depend on

the level and duration of exposure and on the distribution

and kinetics of lead in the body. Most lead is deposited in

bone, and some of this stored lead may be released long

after exposure due to a serious illness, pregnancy, or other

physiological event. Lead has not been shown to cause

can-

cer

in humans, however, tumors have developed in rats and

mice given large doses of lead and thus several United States

agencies consider lead acetate and lead phosphate as human

carcinogens.

Children are particularly susceptible to lead

poison-

ing

. PbB levels as low as 10 g/dL are associated with

decreased intelligence and slowed neurological development.

Low PbB levels also have been associated with deficits in

growth, vitamin

metabolism

, and effects on hearing. The

neurological effects of lead on children are profound and

are likely persistent. Unfortunately, childhood exposures to

chronic but low lead levels may not produce clinical symp-

toms, and many cases go undiagnosed and untreated. In

recent years, the number of children with elevated blood

lead levels has declined substantially. For example, the aver-

age PbB level has decreased from over 15 g/dL in the

823

1970s to about 5 g/dL in the 1990s. As described later,

these decreases can be attributed to the reduction or elimina-

tion of lead in gasoline, food can and plumbing solder, and

residential paint. Still, childhood lead poisoning remains the

most widespread and preventable childhood health problem

associated with environmental exposures, and childhood lead

exposure remains a public health concern since blood levels

approach or exceed levels believed to cause effects. Though

widely perceived as a problem of inner city minority children,

lead poisoning affects children from all areas and from all

socioeconomic groups.

The definition of a PbB level that defines a level of

concern for lead in children continues to be an important

issue in the United States. The childhood PbB concentration

of concern has been steadily lowered by the Centers for

Disease Control (CDC) from 40 g/dL in 1970 to 10 g/

dL in 1991. The

Environmental Protection Agency

low-

ered the level of concern to 10 g/dL ("10-15 and possibly

lower") in 1986, and the

Agency for Toxic Substances and

Disease Registry

(ATSDR) also identified 10 g/dL in its

1988 Report to Congress on childhood lead poisoning.

In the workplace, the medical removal PbB concentra-

tion is 50 g/dL for three consecutive checks and 60 g/

dL for any single check. Blood level monitoring is triggered

by an air lead concentration above 30 g/m

3

. A worker is

permitted to return to work when his blood lead level falls

below 40 g/dL. In 1991, the National Institute for Occupa-

tional Safety and Health (NIOSH) set a goal of eliminating

occupational exposures that result in workers having PbB

levels greater than 25 g/dL.

Exposure and Sources

Lead is a persistent and ubiquitous pollutant. Since it

is an elemental pollutant, it does not dissipate, biodegrade,

or decay. Thus, the total amount of lead pollutants resulting

from human activity increases over time, no matter how

little additional lead is added to the environment. Lead is

a multi-media pollutant, i.e., many sources contribute to the

overall problem, and exposures from air, water,

soil

, dust,

and food pathways may be important.

For children, an important source of lead exposure is

from swallowing nonfood items, an activity known as pica

(an abnormal eating habit e.g., chips of lead-containing

paint), most prevalent in 2 and 3 year-olds. Children who

put toys or other items in their mouths may also swallow

lead if lead-containing dust and dirt are on these items.

Touching dust and dirt containing lead is commonplace,

but relatively little lead passes through the skin. The most

important source of high-level lead exposure in the United

States is household dust derived from deteriorated lead-

based paint. Numerous homes contain lead-based paint and

continue to be occupied by families with small children,

including 21 million pre-1940 homes and rental units which,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Lead management

over time, are rented to different families. Thus, a single

house with deteriorated lead-based paint can be the source

of exposure for many children.

In addition to lead-based paint in houses, other impor-

tant sources of lead exposure include (1)

contaminated

soil

and dust from deteriorated paints originally applied to

buildings, bridges, and water tanks; (2) drinking water into

which lead has leached from lead, bronze, or brass pipes

and fixtures (including lead-soldered pipe joints) in houses,

schools, and public buildings; (3) occupational exposures in

smelting and refining industries, steel welding and cutting

operations, battery manufacturing plants, gasoline stations,

and radiator repair shops; (4) airborne lead from smelters

and other point sources of

air pollution

, including vehicles

burning leaded fuels; (5)

hazardous waste

sites which

contaminate soil and water; (6) food cans made with lead-

containing solder and pottery made with lead-containing

glaze; and (7) food consumption if crops are grown using

fertilizers that contain sewage

sludge

or if much lead-con-

taining dust is deposited onto crops. In the

atmosphere

,

the use of leaded gasoline has been the single largest source

of lead (90%) since the 1920s, although the use of leaded

fuel has been greatly curtailed and gasoline contributions are

now greatly reduced (35%). As discussed below, leaded fuel

and many other sources have been greatly reduced in the

United States, although drinking water and other sources

remain important in some areas. A number of other coun-

tries, however, continue to use leaded fuel and other lead-

containing products.

Government Responses

Many agencies are concerned with lead management.

Lead agencies in the United States include the Environmen-

tal Protection Agency, the Centers for Disease Control,

the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

, the

Department of Housing and Urban Development, the

Food

and Drug Administration

, the Consumer Product Safety

Commission, the National Institute for Occupational Safety

and Health, and the

Occupational Safety and Health Ad-

ministration

. These agencies have taken many actions to

reduce lead exposures, several of which have been very suc-

cessful. General types of actions include: (1) restrictions or

bans on the use of many products containing lead where

risks from these products are high and where substitute

products are available, e.g., interior paints, gasoline fuels, and

solder; (2)

recycling

and safer ultimate disposal strategies for

products where risks are lower, or for which technically and

economically feasible substitutes are not available, e.g., lead-

acid automotive batteries, lead-containing wastes, pigments

and used oil; (3)

emission

controls for lead smelters, primary

metal industries, and other industrial point sources, includ-

ing the use of the best practicable control technology

(BPCT) for new lead smelting and processing facilities and

824

reasonable available control technologies (RACT) for ex-

isting facilities, and; (4) education and abatement programs

where exposure is based on past uses of lead.

The current goals of the Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA) strategy are to reduce lead exposures to the

fullest extent practicable, to significantly reduce the inci-

dence of PbB levels above 10 g/dL in children, and to

reduce lead exposures that are anticipated to pose risks to

children, the general public, or the environment. Several

specific actions of this and other agencies are discussed

below.

The Residential Lead-based Paint Hazard Reduction

Act of 1992 (Title X) provides the framework to reduce

hazards from lead-based paint exposure, primarily in hous-

ing. It establishes a national infrastructure of trained workers,

training programs and proficient laboratories, and a public

education program to reduce hazards from lead exposure in

paint in the nation’s housing stock. Earlier, to help protect

small children who might swallow chips of paint, the Con-

sumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) restricted the

amount of lead in most paints to 0.06 percent by weight.

CDC further suggests that inside and outside paint used in

buildings where people live be tested for lead. If the level

of lead is high, the paint should be removed and replaced

with a paint that contains an allowable level of lead. CPSC

published a consumer safety alert/brochure on lead paint in

the home in 1990, and has evaluated lead test kits for safety,

efficacy, and consumer-friendliness. These kits are potential

screening devices that may be used by the consumer to detect

lead in paint and other materials. Title X also requires EPA

to promulgate regulations that ensure personnel engaged in

abatement activities are trained, to certify training programs,

to establish standards for abatement activities, to promulgate

model state programs, to establish a laboratory accreditation

program, to establish a information clearinghouse, and to

disclose lead hazards at property transfer.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD) has begun activities that include updating regula-

tions dealing with lead-based paint in HUD programs and

federal property; providing support for local screening pro-

grams; increasing public education; supporting research to

reduce the cost and improve the reliability of testing and

abatement; increasing state and local support; and providing

more money to support abatement in low and moderate

income households. HUD estimated that the total cost of

testing and abatement in high-priority hazard homes will

be $8 to 10 billion annually over 10 years, although costs

could be substantially lowered by integrating abatement with

other renovation activities.

CPSC, EPA, and states are required by the Lead

Contamination Control Act of 1988 to test drinking water

in schools for lead and to remove lead if levels are too high.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Leafy spurge

Drinking water coolers must also be lead-free and any that

contain lead must be removed. EPA regulations limit lead

in drinking water to 0.015 mg/L.

To manage environmental exposures resulting from

inhalation, EPA regulations limit lead to 0.1 and 0.05 g/

gal (0.38 and 0.19 g/L) in leaded and unleaded gasoline,

respectively. Also, the National Ambient Air Quality Stan-

dards set a maximum lead concentrations of 1.5 g/m

3

using

a three month average, although typical levels are far lower,

0.1 or 0.2 g/m

3

.

To identify and mitigate sources of lead in the diet,

the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has undertaken

efforts that include voluntary discontinuation of lead solder

in food cans by the domestic food industry, and elimination

of lead in glazing on ceramic ware. Regulatory measures are

being introduced for wine, dietary supplements, crystal ware,

food additives

, and bottled water.

For workers in lead-using industries, the Occupational

Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has established

environmental and biological standards that include maxi-

mum air and blood levels. This monitoring must be con-

ducted by the employer, and elevated PbB levels may require

the removal of an individual from the work place (levels

discussed previously). The Permissible Exposure Level

(PEL) limits air concentrations of lead to 50 g/m

3

, and,

if 30 g/m

3

is exceeded, employers must implement a pro-

gram that includes medical surveillance, exposure monitor-

ing, training, regulated areas, respiratory protection, protec-

tive work clothing and equipment, housekeeping, hygiene

facilities and practices, signs and labels, and record keeping.

In the construction industry, the PEL is 200 g/m

3

. The

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NI-

OSH) recommends that workers not be exposed to levels

of more than 100 g/m

3

for up to 10 hours, and NIOSH

has issued a health alert to construction workers regarding

possible adverse health effects from long-term and low-level

exposure. NIOSH has also published alerts and recommen-

dations for preventing lead poisoning during blasting, sand-

ing, cutting, burning, or welding of bridges and other steel

structures coated with lead paint.

Finally, lead screening for children has recently in-

creased. The CDC recommends that screening (testing) for

lead poisoning be included in health care programs for chil-

dren under 72 months of age, especially those under 36

months of age. For a community with a significant number

of children having PbB levels between 10-14 g/dL, com-

munity-wide lead poisoning prevention activities should be

initiated. For individual children with PbB levels between

15-19 g/dL, nutritional and educational interventions are

recommended. PbB levels exceeding 20 g/dL should trig-

ger investigations of the affected individual’s environment

and medical evaluations. The highest levels, above 45 g/

825

dL, require both medical and environmental interventions,

including chelation therapy. CDC also conducts studies to

determine the impact of interventions on children’s blood

lead levels.

These regulatory activities have resulted in significant

reductions in average levels of lead exposure. Nevertheless,

lead management remains an important public health

problem.

[Stuart Batterman]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Breen, J. J., and C. R. Stroup, eds. Lead Poisoning: Exposure, Abatement,

Regulation. Lewis Publishers, 1995.

Kessel, I., J. T. O’Connor, and J. W. Graef. Getting the Lead Out: The

Complete Resource for Preventing and Coping with Lead Poisoning. Rev. ed.

Cambridge, MA: Fisher Books, 2001.

Pueschel, S. M., J. G. Linakis, and A. C. Anderson. Lead Poisoning in

Childhood. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., 1996.

O

THER

Farley, Dixie. “Dangers of Lead Still Linger.” FDA Consumer January-

February 1998 [cited July 2002]. <http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/fda-

lead.html>.

Lead shot

Lead

shot refers to the small pellets that are fired by shotguns

while

hunting

waterfowl or upland fowl, or while skeet

shooting. Most lead shots miss their target and are dissipated

into the

environment

. Because the shot is within the parti-

cle-size range that is favored by medium-sized birds as grit,

it is often ingested and retained in the gizzard to aid in the

mechanical abrasion of plant seeds, the first step in avian

digestion. However, the shot also abrades during this pro-

cess, releasing toxic lead that can poison the bird. It has

been estimated that as much as 2–3 percent of the North

American waterfowl population, or several million birds,

may die from shot-caused lead

poisoning

each year. This

problem will decrease in intensity, however, because lead

shot is now being substantially replaced by steel shot in North

America. See also Heavy metals and heavy metal poisoning

Leafy spurge

Leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula L.), a perennial plant from

Europe and Asia, was introduced to North America through

imported grain products by 1827. It is 12 in (30.5 cm) to

3 ft (1 m) in height. Stems, leaves, and roots contain milky

white latex which contains toxic cardiac glycosides that is

distasteful to cattle, who will not eat it. Considered a noxious,

or destructive, weed in southern Canada and the northern

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

League of Conservation Voters

Great Plains of the United States, it crowds out native range-

land grasses, reducing the number of cattle that can graze

the land. It is responsible for losses of approximately 35–45

million dollars per year to the United States cattle and hay

industries. Its aggressive root system makes controlling

spread difficult. Roots spread vertically to 15 ft (5 m) with

up to 300 root buds, and horizontally to nearly 30 ft (9 m).

It regenerates from small portions of root. Tilling, burning,

and

herbicide

use are ineffective control methods as roots

are not damaged and may prevent immediate regrowth of

the desired

species

. The introduction of specific herbivores

of the leafy spurge from its native range, including certain

species of beetles and moths, may be an effective means of

control, as may be certain pathogenic

fungi

. Studies also

indicate sheep and Angora goats will eat it. To control this

plant’s rampant spread in North America, a combination of

methods seems most effective.

[Monica Anderson]

League of Conservation Voters

In 1970 Marion Edey, a House committee staffer, founded

the League of Conservation Voters (LCV) as the non-parti-

san political action arm of the United States’ environmental

movement. LCV works to establish a pro-environment—or

“green”—majority in Congress and to elect environmentally

conscious candidates throughout the country. Through cam-

paign donations, volunteers, and endorsements, pro-envi-

ronment advertisements, and annual publications such as

the National Environmental Scorecard, the League raises voter

awareness of the environmental positions of candidates and

elected officials.

Technically it has no formal membership, but the

League’s supporters—who make donations and purchase its

publications—number 100,000. The board of directors is

comprised of 24 important environmentalists associated with

such organizations as the

Sierra Club

, the

Environmental

Defense

Fund, and

Friends of the Earth

. Because these

organizations would endanger their charitable tax status if

they participated directly in the electoral process, environ-

mentalists developed the League. Since 1970 LCV has influ-

enced many elections.

From its first effort in 1970—wherein LCV success-

fully prevented Rep. Wayne Aspinall of Colorado from ob-

taining a democratic nomination—the League has grown to

be a significant force in American politics. In the 1989–90

elections LCV supported 120 pro-environment candidates

and spent approximately $250,000 on their campaigns. In

1990 the League developed new endorsement tactics. First

826

it invented the term “greenscam” to identify candidates who

only appear green. Next LCV produced two generic televi-

sion advertisements for candidates. One advertisement, enti-

tled “Greenscam,” attacked the aforementioned candidates;

the other, entitled “Decisions,” was an award-winning, posi-

tive advertisement in support of pro-environment candi-

dates. By the 2000 campaign the League had attained an

unprecedented degree of influence in the electoral process.

That year LCV raised and donated 4.1 million dollars in

support of both Democratic and Republican candidates in

a variety of ways.

In endorsing a candidate the League no longer simply

contributes money to a campaign. It provides “in-kind” as-

sistance—for example, it places a trained field organizer on a

staff, creates radio and television advertisements, or develops

grassroots outreach programs and campaign literature. In

addition to supporting specific candidates, LCV holds all

elected officials accountable for their track records on envi-

ronmental issues. The League’s annual publication National

Environmental Scorecard lists the voting records of House

and Senate members on environmental legislation. Likewise,

the Presidential Scorecard identifies the positions that presi-

dential candidates have taken. Through these publications

and direct endorsement strategies, the League continues to

apply pressure in the political process and elicit support for

the

environment

[Andrea Gacki]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

League of Conservation Voters, 1920 L Street, NW, Suite 800,

Washington, D.C. USA 20036 (202) 785-8683, Fax: (202) 835-0491,

<http://www.lcv.org>

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (1903 –

1972)

African-born English paleontologist and anthropologist

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey was born on August 7, 1903,

in Kabete, Kenya. His parents, Mary Bazett (d. 1948) and

Harry Leakey (1868–1940) were Church of England mis-

sionaries at the Church Missionary Society, Kabete, Kenya.

Louis spent his childhood in the mission, where he learned

the Kikuyu language and customs (he later compiled a Ki-

kuyu grammar book). As a child, while pursuing his interest

in ornithology—the study of birds—he often found stone

tools washed out of the

soil

by the heavy rains, which Leakey

believed were of prehistoric origin. Stone tools were primary

evidence of the presence of humans at a particular site, as

toolmaking was believed at the time to be practiced only by