Gino Moliterno. Encyclopedia of Contemporary Italian Culture

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

classic detective genre with those of the hard-boiled school and the sentimental novel.

The protagonist, Duca Lamberti, who works in a sadistically violent Milan, is a tough

cynic like some of Hammett’s or Chandler’s characters, but the impossibility of changing

the surrounding moral squalor infuriates rather than saddens him. A physician struck off

the register and jailed for three years for practising euthanasia, he has no ethical

attachment to his job but feels sorry for himself and for innocent victims, and

passionately hates all ‘criminals’, who for him include homosexuals, prostitutes, drug

addicts, women who undergo abortion, capelloni (hippies with long hair), corrupt lawyers

and exploiters of all kinds. His job is not to re-educate them but to punish them violently

and to expose the details of their horrible crimes. His Manichaean moralism appealed to

an urban middle-class readership which, in the late 1960s, was demanding law and order.

However, the author added other main characters who came from the society’s lower

ranks, thus expanding his readership.

Scerbanenco’s success has not been repeated in the history of the Italian detective

novel in its true form. In 1972, Carlo Fruttero and Franco Lucentini published La donna

delta domenica (The Sunday Woman), a bestseller which, while remaining within the

convention of a classic detective novel, included references to many other literary genres,

thus becoming a detective novel of manners. The technique of mixing genres and quoting

other books has been fully explored by Umberto Eco in his 1980 international bestseller

Il nome della rosa (The Name of the Rose), a genuinely postmodern combination of

medieval whodunnit, gothic novel, allegory and roman-à-clè.

Italian detective stories by such writers as Massimo Felisatti, Fabio Pittorru, Loriano

Macchiavelli, Nicoletta Bellotti, Luciano Anselmi, Laura Grimaldi and Luciano Secchi

have continued to find a popular audience, and in the late 1990s the novels of Giuseppe

Ferrandino and Andrea Camilleri have become bestsellers. Detective fiction has also had

its high-brow authors, in particular Carlo Emilio Gadda and Leonardo Sciascia. Gadda’s

Quer pasticciaccio brutto de Via Merulana (That Ugly Mess in Merulana Street) is an

experimental avantgarde text of 1946 which uses the detective genre brilliantly in order

to explore language in a way that has drawn frequent comparison with James Joyce. In

Sciascia’s Il giorno della civetta (The Day of the Owl) (1961) and A ciascuno il suo (To

Each His Own) (1966), we also find an original utilization of the traditional structures of

detective fiction for the purposes of social commentary.

Further reading

Carloni, M. (1985) ‘Storia e geografia di un genere letterario: il romanzo poliziesco italiano

contemporaneo’ (History and Geography of a Literary Genre: The Contemporary Italian

Detective Novel), Critica letteraria 13 (46):167–87 (a useful history of the genre with

interesting exploration of the relationship between the novels and their setting).

FRANCO MANAI

Entries A–Z 241

Di Pietro, Antonio

b. 2 October 1950, Montenero di Bisaccia, Campobasso

Magistrate

A relatively unknown magistrate, Antonio Di Pietro found himself thrown abruptly into

the limelight on 17 February 1992 with the arrest of Mario Chiesa, the first move in the

anti-corruption drive codenamed Mani pulite (Clean Hands). Thereafter Di Pietro’s name

was inextricably linked to the campaign whose aim was to dismantle the system of public

corruption, subsequently nicknamed Tangentopoli (Bribesville), and which contributed

significantly to the fall of the First Republic.

Born into a peasant family in the Southern region of Molise, Di Pietro emigrated as a

young man to Germany to find work. In 1974 he enrolled in the Law Faculty in Milan,

graduating in 1979. His first employment was with the police force, and only in 1981 was

he taken on as magistrate in Bergamo. The experience was not a happy one. He was

dismissed as ‘unfit to undertake the work of a magistrate’, and reinstated only after

appeals to the Supreme Council of the Magistracy.

In 1986 he transferred to Milan and began working with a pool of magistrates who

became convinced of the existence of a widespread network of corruption linking the

worlds of business and politics. Di Pietro’s adroit use of computer technology enabled

him to track what he suspected were illegal payments, until a complaint against Mario

Chiesa, who was employed by a philanthropic trust but was closely involved with the

Milanese Socialist Party, gave him the opportunity he needed. Chiesa was caught red-

handed, and after a period of imprisonment provided information which incriminated

other public officials and politicians.

Subsequent suspects were equally willing to talk. Di Pietro revealed himself a

relentless interrogator, but he attracted criticism in some quarters for his willingness to

use preventive detention as a means of persuading suspects to collaborate. Investigations

widened out from Milan, and it came to seem that the entire system of government which

had ruled Italy since the war was on trial. Local and national politicians, cabinet

ministers, civil servants, financiers and businessmen found themselves under

investigation for giving or receiving bribes. The Socialist leader and ex-Prime Minister,

Bettino Craxi, was probably the most celebrated casualty, while the televised trial of the

financier Sergio Cusani in 1993–4 revealed to the nation both the forensic skills of Di

Pietro and the sheer scale of the political-financial intrigue involved. Silvio Berlusconi,

the first Prime Minister of the supposed ‘new’ order, was also incriminated over the

activities of his industrial empire, Fininvest.

Di Pietro was now lionized by ordinary Italians, but was increasingly vilified by the

Berlusconi press and embroiled in the machinations of his many enemies. He resigned

from the magistracy in 1994 in mysterious circumstances, amid allegations that he had

been blackmailed. Having expressed interest in a political career, he was courted by

several parties. His own political allegiances, although unclear, seemed to lie with the

Right, but perhaps because the right-wing coalition was headed by Berlusconi, from

whom he was divided by deep personal antipathy, he refused all Rightist affiliations and

in May 1996 accepted Romano Prodi’s invitation to become Minister for Public Works in

Encyclopedia of contemporary italian culture 242

his centre-left cabinet. His period in office was undistinguished, and he resigned in

November of the same year when under inquiry by Brescia magistrates for alleged receipt

of illegal payments. He was completely exonerated, and in November 1997 was elected

to the Senate as a member of the Olive Tree coalition (see Ulivo).

See also: legal system

JOSEPH FARRELL

Di Venanzo, Gianni

b. 18 December 1920, Teramo; d. 3 January 1966, Rome

Cinematographer

At the time of his premature death at the age of forty-five, Di Venanzo was widely

regarded as Italy’s leading cinematographer. After serving as a young camera assistant

under Otello Martelli and G.R. Aldo on many of the classic neorealist films, including

Visconti’s La Terra Trema (The Earth Trembles) (1948) and Rossellini’s Paisà (Paisan)

(1946), he became director of photography for Lizzani’s Achtung! Banditi! (Halt!

Bandits!) (1951), He subsequently worked on over forty films with most of the major

Italian directors including Monicelli, Fellini, Comencini and Lina Wertmüller. He

developed a particularly strong partnership with Antonioni, for whom he photographed

all of the early films with the exception of L’avventura (The Adventure) (1960), and with

Francesco Rosi, with whom he made all the films up to and including Le mani sulla città

(Hands over the City) (1963). An innovative and creative photographer, he experimented

with lighting and pioneered new techniques, thereby developing a distinctive personal

style which was nevertheless flexible enough to serve both the austerity of Antonioni’s

La notte (The Night) (1961) and the sumptuousness of Fellini’s 8½.

See also: cinematographers

GINO MOLITERNO

Diabolik

A comic book series first appearing in 1962, Diabolik was created by Angela and

Luciana Giussani, who modelled their stories on those of the criminal hero of French

popular literature, Fantomas, and added a touch of romance. Each episode presents the

thief, Diabolik, dressed in a black catsuit and assuming different disguises, performing

the most sensational and atrocious crimes, with no other aim than self-affirmation. He

always escapes the implacable pursuit of his almost as ingenious nemesis, Police

Commissioner Ginko, through his exceptional intelligence, audacity and the

indispensable help of his lover Eva Kant. Diabolik’s victims come from the aristocracy

Entries A–Z 243

and upper middle classes, and are shown as evildoers who hide their own crimes behind

their false morality and respectability.

In direct contrast to the American superheroes who put their powers in the service of

the law, Diabolik appealed to a transgressive and anticonformist teenage and adult

readership. Its format was also attractive, pocket-size like Topolino (Mickey Mouse),

while its cover carried the label ‘For adults only’. Its drawings were suggestively in black

and white, and its narrative was easy to read. Diabolik’s great success generated the

phenomenon of the fumetto new (crime comic), but it also survived the demise of the

latter by adapting to change in public taste while remaining fundamentally faithful to its

original formula.

See also: comics

FRANCO MANAI

dialect usage

Dialects are widely used in Italy. While the percentage of dialect monolinguals is very

low (around 7 per cent), and that of Italian monolinguals is somewhat higher (around 30

per cent), the vast majority of Italians are bilingual and alternate the use of both

languages in a complex and interesting way. Dialects are used more within the home than

outside, more in informal situations than in formal ones, and more in the northeast area,

the South and the islands than in the northwest and the centre of Italy. Older people use

them more than younger people, and men more than women; younger interlocutors, in

particular children, elicit minimal use of dialect, whereas maximal use occurs in

addressing older people. Furthermore, dialects are used more (1) among the lower

classes; (2) by people with lower levels of education but also, interestingly, by graduates

more than by people with high school diplomas; (3) in rural areas; and (4) in smaller

towns, particularly those with less than 2,000 inhabitants. Besides everyday

communication, they are used in other areas such as music and literature.

Use of dialects has been decreasing considerably since the Second World War as a

result of the spreading of the Italian language, and this may raise the question of their

disappearance in the near future. However, although dialects enjoy a lower prestige than

Italian, they are still a vital part of the repertoire of Italians, and today it is not so much a

matter of disappearance as of transformation, as the dialects increasingly become more

similar to Italian.

The changes that have occurred in dialect use at the national level were particularly

rapid in the decades 1950–90, concurrent with the rapid social and economic

transformations of postwar Italy. However, throughout the 1990s the decrease in dialect

usage seems to have slowed down. In 1951 more than 60 per cent of the Italian

population still used only dialect in most circumstances. Subsequent changes in use have

been recorded by a series of surveys conducted by Doxa, a public opinion poll research

institute. These surveys included questions on language use inside and outside the home

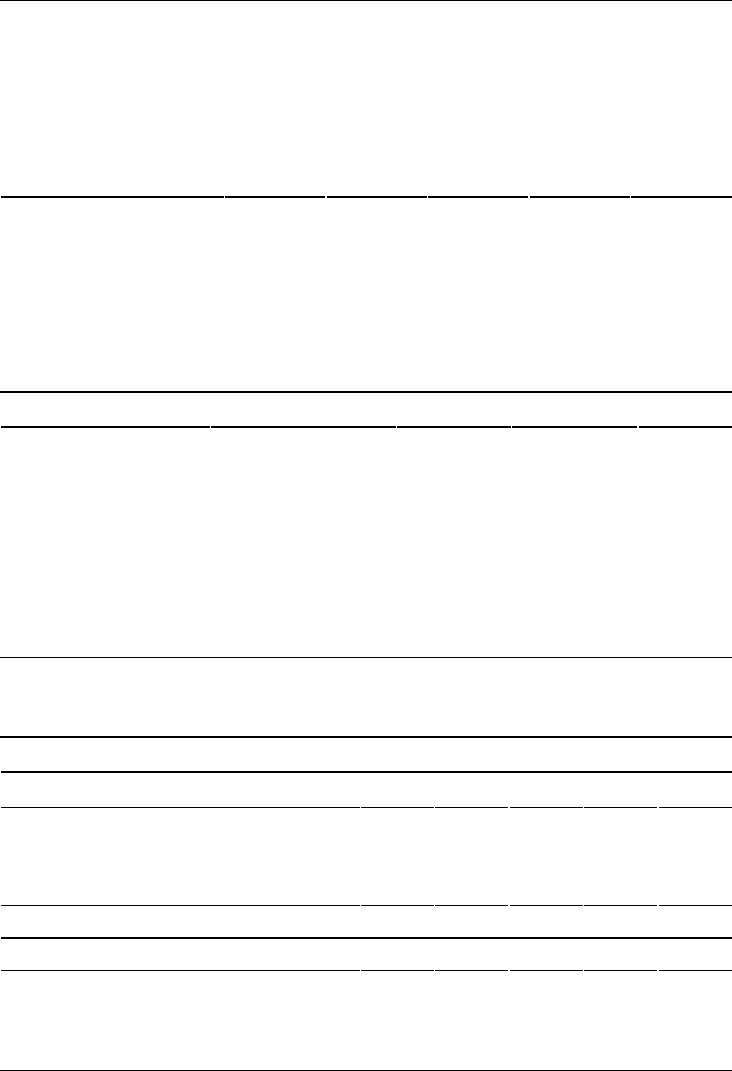

environment (with friends and work mates). Table 1 shows that use of dialect (1) is

constantly higher within the home than outside; (2) is higher among older people, men

Encyclopedia of contemporary italian culture 244

and in the northeast, the South and the islands, within the home but more markedly so

outside; and (3) has constantly decreased from 1974 to 1991 while increasing slightly

outside the home throughout the 1990s.

Table 2 shows the incidence of the interlocutor’s age. Minimal use of dialect occurs in

talking to children, and the more so by young speakers, whereas maximal use occurs in

addressing older people, the more so by speakers of the same age or older.

Table 3 shows that, although the use of Italian only is on the increase, in the Doxa

surveys more

Table 1 Use of dialect in Italy according to age,

gender and geographical area (Doxa surveys)

1974 1982 1988 1991 1996

1

At home

Total Italy 51.3% 46.7% 39.6% 35.9% 33.9%

age

up to 34 yrs 46.0% 37.9% 31.2% 28.6% 24.7%

35–54 yrs 46.7% 46.7% 32.7% 32.9% 27.9%

beyond 54 yrs 64.0% 58.1% 57.1% 48.4% 48.0%

gender

women 49.3% 47.4% 36.2% 32.7% 31.9%

men 53.4% 46.0% 43.4% 39.4% 35.9%

geogr. area

Northwest 39.0% 37.2% 25.0% 20.2% 18.6%

Northeast 61.3% 59.6% 50.5% 51.0% 47.5%

Centre 33.2% 24.7% 24.1% 22.0% 24.0%

South & Islands 66.8% 60.6% 53.7% 48.5% 44.2%

Outside the home

2

Total Italy 42.3% 36.1% 33.2% 22.8% 28.2%

age

up to 34 yrs 31.4% 23.8% 22.3% 11.6% 18.0%

35–54 yrs 42.1% 37.5% 32.1% 24.6% 31.0%

beyond 54 yrs 55.7% 50.3% 48.7% 35.4% 53.0%

gender

women 40.3% 36.6% 29.0% 19.6% 25.6%

Entries A–Z 245

men 44.4% 35.6% 37.8% 26.3% 31.0%

geogr. area

Northwest 34.8% 29.0% 19.2% 12.9% 20.9%

Northeast 55.2% 53.2% 51.0% 37.7% 38.9%

Centre 23.7% 14.7% 19.0% 12.2% 19.2%

South and Islands 52.2% 45.2% 42.2% 29.1% 33.2%

Notes:

1 For 1996, the percentages against the age brackets have been calculated by collapsing the six age

brackets provided by Doxa.

2 These percentages include both the respondents who ‘always use dialect’ and those who ‘use

more dialect than Italian’.

Table 2 Use of dialect outside the home in Italy,

1996 (Doxa survey)

interlocutors

subjects children younger same age older

15–24 years 6.8% 13.1% 17.3% 20.7%

25–34 years 5.6% 9.3% 12.7% 21.9%

35–44 years 10.5% 14.1% 21.2% 29.9%

45–54 years 10.9% 19.6% 32.6% 39.6%

55–64 years 18.6% 26.6% 45.5% 49.2%

beyond 64 years 21.4% 31.6% 58.7% 60.7%

Table 3 Use of dialect and Italian in Italy (Doxa

Survey)

Language use at home

1974 1982 1988 1991 1996

Dialect with all family members 51.3% 46.7% 39.6% 35.9% 33.9%

Italian with all family members 25.0% 29.4% 34.4% 33.6% 33.7%

Dialect with some, Italian with others 23.7% 23.9% 26.0% 30.5% 32.4%

Language use outside the home

1974 1982 1988 1991 1996

Always uses dialect 28.9% 23.0% 23.3% 12.8% 15.3%

Always uses Italian 22.7% 26.7% 31.0% 29.9% 32.6%

Uses both Italian and dialect 22.1% 22.0% 19.5% 29.1% 22.2%

Encyclopedia of contemporary italian culture 246

Uses more dialect than Italian 13.4% 13.1% 9.9% 10.0% 12.9%

Uses more Italian than dialect 12.9% 15.2% 16.3% 18.2% 17.0%

than one quarter of the subjects within the home and more than half outside still declare

they use both the dialect and Italian.

The division in the use of dialect and Italian is not clearcut, as the shift away from

dialect has been occurring not so much in the direction of the exclusive use of Italian, but

more commonly of the alternate use of the two languages also within conversation. The

alternation of dialect and Italian in conversation, or ‘code switching’, has not yet been

researched extensively. It seems however that it occurs more in rural areas than in urban

ones, and more frequently and in a wider range of social situations in some regions (for

example, Veneto and Sicily) than in others. Patterns of switching also seem to vary, as in

rural areas it tends to be from a dialect base into Italian, whereas in urban areas it is often

limited to the insertion of dialect words in Italian-based discourse. The latter is more

evident in the speech of younger generations and may be due to their inadequate

competence of dialect.

Switching between dialect and Italian can also be connected to situational factors,

among which interlocutor and topic tend to play a prominent role. Typically, interlocutors

belonging to the same network and more personal topics elicit switches towards dialect.

However, asymmetrical conversations, where one participant uses dialect and the other

Italian, are also very frequent. Switching can also be linked to (1) the organization of

discourse, for example to reformulate, to add a side comment or to signal a quotation; (2)

the speaker’s language preferences or competence; or (3) specific conversational

functions, such as switches to dialect for special emphasis, for expressive or emotive

reasons, or jokingly. However, the frequent bi-directionality of switching indicates that

often it is the contrastive use of the two languages to be meaningful, rather than the single

switch into either language. Furthermore, dialect-Italian switching generally occurs in a

smooth way, without any signalling to the interlocutor. This has been attributed to the

fact that, since in Italy speaker and interlocutor belong to the same bilingual community,

they do not need to negotiate the linguistic rules of their behaviour.

As extensively used in everyday conversation as switching is dialect-Italian mixing,

where forms from each language alternate within the same utterance in an often

inextricable way: for example, None quedda. Sta ancora questa. Sai ce d-è? quiddu

magglione bianco, quiddu grande che comprai io (Sobrero 1988) (‘Not that one. There is

still this one. You know what is it? That white jumper, the big one that I bought’ (my

translation)). This excerpt shows mixing between dialect and regional Italian, with dialect

affecting Italian in terms of sounds, grammar and word choice. Mixing is favoured by the

structural similarity between dialects and Italian and by the reciprocal interference caused

by their intense contact, whereby dialect forms become Italianized and Italian forms take

on dialectal features. For example, words can be made up by lexical morphemes of one

language and grammatical morphemes of the other, so that it can be difficult to assign

them to either language: for example, Sicilian appizzare with the Sicilian meaning of

perdere, ‘to miss out’, and the Italian verbal ending -are. Due to the structural similarity,

the occurrence of mixed words and the high number of homophones, dialect-Italian

switching and mixing tend to occur freely without any structural restriction.

Entries A–Z 247

Another area where dialect is used is in literature. Interestingly, after the Second

World War, poetry in dialect has developed considerably, possibly as a reaction against

the levelling of the Italian language, and is particularly thriving in some regions like the

Veneto, with such poets as Noventa and Zanzotto. On the other hand, the general decline

of dialects in Italian society seems to have determined also their decline in narrative,

where today they have a rather marginal role. However, many contemporary writers still

make use of some dialect in their works, particularly at the lexical and syntactic levels

(for example, Mastronardi or Sciascia).

Dialect is not much used in the cinema, probably because it would not be understood

by the wider audience. However, Italian-dialect mixing is fairly common, and has

become the distinctive speech style of some actors, such as the Neapolitan of Massimo

Troisi or the Florentine of Roberto Benigni. Some dialect is used in advertising, often to

link the product to past ages and thus underline its high quality. Dialect is also used in

music, by groups that perform traditional folk songs, for example Nuova Compagnia di

Canto Popolare, as well as by other singers or songwriters. A more recent phenomenon

is the formation of rock bands that choose to sing in dialect, such as Pitura Freska in the

Veneto or the 99 Posse in Naples (see rap music).

Dialects are also used outside of Italy, for example in some parts of Switzerland

(Lombard) or of Corsica (Tuscan), and in the numerous communities of Italian migrants.

The secessionist movements such as Lega Nord use dialect as a symbol of their struggle

for autonomy, but they do not seem to have been particularly effective in reversing the

shift away from dialect, particularly among the younger generations. The impact of these

movements, however, has yet to be investigated systematically.

See also: cantautori; dialects; Italian language; Italian outside Italy; Italian and

emigration; language attitudes; language education; language policy; literature in dialect;

varieties of Italian

Further reading

Anonymous (1996) ‘L’uso del dialetto’ (The Use of Dialect), in Bollettino della Doxa 50 (16–17),

17 September.

Alfonzetti, G. (1992) Il discorso bilingue. Italiano e dialetto a Catania, (Bilingual Discourse:

Italian and Dialect in Catania), Milan: Franco Angeli (a study of Italian—Sicilian code

switching in a range of social situations; see chaps 2 and 3).

Giacalone Ramat, A. (1995) ‘Code-Switching in the Context of Dialect/Standard Language

Relations’, in L.Milroy and P.Muysken (eds), One Speaker, Two Languages: Cross-disciplinary

Per-spectives on Code-switching, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (an in-depth

discussion of the issues raised by code switching in the light of the specific Italian situation).

Sobrero, A.A. (1988) ‘Villages and Towns in Salento: The Way Code Switching Switches’, in

N.Dittmar and P.Schlobinski (eds), The Sociolinguistics of Urban Vernaculars: Case Studies

and Their Evaluation, Berlin and New York: de Gruyter.

——(1994) ‘Code Switching in Dialectal Communities in Italy’, Rivista di Linguistica 6 (1):39–55

(an overview of the major sociolinguistic variables of Italian-dialect code switching).

ANTONIA RUBINO

Encyclopedia of contemporary italian culture 248

dialects

Italian dialects are separate languages geographically distributed throughout the

peninsula, which differ from each other to the extent of being mutually unintelligible if

they belong to non-adjacent areas. The reason for such profound diversity is to be found

initially in a different evolution of spoken Latin in the various parts of Italy during the

Middle Ages, and in the following centuries of political fragmentation before final

unification in 1861. In relation to the Italian language—the national language—today

the dialects are ‘low languages’ in the sense that they are used mainly orally in a

narrower geographical area (dialect usage). Although they are still very vital, in the last

decades they have been undergoing a process of Italianization as a result of their intense

contact with Italian and the latter’s increasing use nationwide. Consequently, dialects are

tending to become more uniform throughout their region or province as they are losing

their more local features. At the same time, they also influence the way Italian is used in

the various regions, particularly at the level of pronunciation and vocabulary (see

varieties of Italian).

The formation of dialects dates from the last centuries of the Roman empire, when the

central power started to decline and cultural and linguistic models began to weaken. The

already existing difference between literary and spoken Latin increased remarkably,

particularly when Italy was split into separate areas after the fall of the empire. Political

autonomy favoured linguistic fragmentation, and thus many distinct languages

developed. The first documents which prove the existence in Italy of languages

significantly different from Latin date back to the end of the first millennium. From

approximately the year 1000, these languages developed considerably, particularly as

spoken languages but also in writing. Some of them were especially prestigious in that

they were the languages of important and thriving towns, such as Milan, Bologna,

Florence and Palermo, where the first literary works were also written.

This situation of polycentrism changed from the fourteenth century onwards as a result

of the increasing importance of Florence as the major economic, political, cultural and

literary centre. The fact that three eminent writers—Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca

(Petrarch) and Giovanni Boccaccio—wrote in Florentine gave high prestige to this

language, while Florence’s status as a major commercial centre contributed to promoting

it. Between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Florentine continued to spread as a

written language next to Latin well outside Tuscany, and became the basis of the national

literary language, Italian. From this point onwards Italian was the high language, and all

the others began to be considered dialects.

In the following four centuries, the various dialects were used practically by the whole

population for speaking purposes, while a narrow elite also used Italian (or Latin and

French) for writing. However, on a much smaller scale, some dialects were also used for

literary works (for example, Venetian in Goldoni’s plays). This gap between speech and

writing continued until the country was unified (1861) as well as throughout several

decades after unification, due to the poor socioeconomic conditions of the new state and

continuing high levels of illiteracy. In spite of their widespread use, dialects were

stigmatized as an obstacle to the learning of ‘correct’ Italian, particularly by

schoolchildren, and thus to the spreading of a single national language. The repression of

Entries A–Z 249

dialects reached its climax during Fascism, when they were seen as counter to the

nationalism and centralism that were essential to the Fascist regime. Thus, publications in

dialect were banned (1931) and dialects were excluded from schools (1934). In spite of

the absence of such prohibitions after the fall of Fascism, the use of dialects continued to

decrease in the postwar period.

Geographically, Italian dialects form a continuum, such that those of adjacent areas

differ only minimally while more distant ones differ to a greater extent. The traditional

classification divides them into three main groups: Northern, Central and Southern

dialects, separated by two lines: La Spezia-Rimini and Ancona-Rome.

The La Spezia-Rimini line divides Northern from Central (more specifically, Tuscan)

dialects. Some of the phonetic features distinguishing the two groups are the following:

(1) voiced intervocalic consonants to the north versus voiceless ones to the south of the

line (for example, [d] versus [t], as in [fra’dεl] instead of fratello, ‘brother’); (2) single

intervocalic consonants to the north versus double ones to the south of the line (for

example [‘fato] for fatto, ‘fact’; (3) deletion of unstressed final vowels to the north of the

line (for example, [ka’val] for cavallo, ‘horse’). At the grammatical level, Northern

dialects substitute subject pronouns io (‘I’) and tu (‘you’), with the equivalent object

forms mi (‘me’) and ti (‘you’).

The Ancona-Rome line separates Central from Southern dialects. At the phonetic

level, Southern dialects are distinguished by particular consonant groups: -nd- instead of-

nt- (e.g., quanto, ‘how much’, becomes [‘kwando]); -nn- instead of -nd- (e.g., manda,

‘send’, becomes [‘manna]); and -mm-instead of -mb- (e.g., gamba, ‘leg’, becomes

[‘gamma]). A second important feature of Southern dialects compared with the Central

ones, and Tuscan in particular, is metaphony, that is, a process of assimilation between

non-adjacent vowels in a word; in Southern dialects this is often triggered by final

unstressed [i] and [u] which cause changes in the preceding stressed vowels (e.g.,

Southern Latium niru for the masculine singular nero ‘black’, and niri for the masculine

plural neri, given that [e] becomes [i] under the influence of final [u] and [i] respectively,

versus the feminine singular nera which maintains [e]). At the grammatical level,

Southern dialects are characterized by possessive adjectives postposed and attached to the

nouns they refer to (e.g., matrima for mia madre, ‘my mother’). Further-more, a number

of words distinguish Central from Southern dialects, such as donna versus femmina for

‘woman’, or fratello versus frate for ‘brother’.

Within the three main groups of dialects, some further subdivisions can be identified.

Among the Northern dialects, the so-called Gallo-Italian dialects (in Piedmont,

Lombardy, Liguria and Emilia-Romagna) are distinguished from those of the Veneto

region. Some of the main features of the Gallo-Italian dialects are the following: rounded

vowels [ö] [ü] (e.g., [‘lüm] for lume, ‘lamp’); palatalization of [a] into either [ε] or [e]

(e.g., [’sεl] for sale, ‘salt’); and deletion of unstressed vowels, either in final position or

preceding stressed vowels (e.g., man for mano, ‘hand’, or

fnestra for finestra, ‘window’).

Furthermore, the Latin consonant group -kt- has developed into -jt- in parts of Piedmont

and into [t∫] in Lombardy: for example, Latin ‘noctem’ has become [‘nojt] and [‘not∫]

respectively for the Italian notte, ‘night’. On the other hand, in the dialects from the

Veneto region, the same consonant group -kt- has developed into [t], so that the word is

[‘note].

Encyclopedia of contemporary italian culture 250