Gubbins D., Herrero-Bervera E. Encyclopedia of Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Aurorae

In 1716 Halley observed an intense auroral display over London (Hal-

ley, 1716). He collected reports from distant places and plotted the

forms of the auroral arcs. They followed the lines of the Earth’s mag-

netic field and were most intense around the magnetic, not the geo-

graphic, pole. Halley argued that matter circulating around the field

lines produced the aurorae. He thought the matter leaked out of hollow

spaces in the Earth, perhaps between the core and the mantle. He did

not explain the colors. As there were then no instruments to detect

the daily variation of the geomagnetic field or magnetic storms, Halley

could not relate aurorae to events on the Sun.

Halley established entirely new lines of enquiry in his three princi-

pal contributions to geomagnetism. He was buried with his wife in

the churchyard of St Margaret’s Lee, not far from the Royal Observa-

tory where a wall now carries his gravestone with its memorial inscrip-

tion. There is a tablet in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey, and the

observatory at Halley Bay on Antarctica recalls his magnetic and aur-

oral observations and the cruise that went so close to the Antarctic

continent. A recent biography is in Cook (1998).

Sir Alan Cook

Bibliography

Cook, A., 1998. Edmond Halley: Charting the heavens and the seas.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Descartes, René, 1644. Principia Philosophiae. Amsterdam.

Halley, E., 1683. A theory of the variation of the magnetical compass.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 13, 208–221.

Halley, E., 1692. An account of the cause of the change of the varia-

tion of the magnetic needle, with an hypothesis of the structure

of the internal parts of the Earth. Philosophical Transactions of

the Royal Society, 17, 563–578.

Halley, E., 1716. An account of the late surprising appearance of lights

seen in the air, on the sixth of March last, with an attempt to

explain the principal phenomena thereof, as it was laid before the

Royal Society by Edmund Halley, J.V.D., Savilian Professor of

Geometry, Oxon, and Reg. Soc. Secr. Philosophical Transactions

of the Royal Society, 29, 406–428.

Kircher, A., 1643. Magnes, sive de arte magnetica, opus tripartium.

Rome.

Thrower, N.J.W. (ed.), 1981. The three voyages of Edmond Halley in

the “Paramour”, 1698–1701., 2nd series, vol. 156, 157. London:

Hakluyt Society Publications.

Cross-references

Auroral Oval

Bemmelen, Willem van (1868–1941)

Geomagnetism, History of

Gilbert, William (1544–1603)

Hansteen, Christopher (1784–1873)

Humboldt, Alexander von (1759–1859)

Humboldt, Alexander von and magnetic storms

Jesuits, Role in Geomagnetism

Kircher, Athanasius (1602–1680)

Storms and Substorms, Magnetic

Voyages Making Geomagnetic Measurements

Westward Drift

HANSTEEN, CHRISTOPHER (1784–1873)

Christopher Hansteen (1784–1873) was born in Christiania (now

Oslo), Norway. In the years 1816–1861 he was professor of applied

mathematics and astronomy at the institution today denoted as the

University of Oslo. His pioneering achievements in terrestrial magnet-

ism and northern light research are today widely appreciated (Brekke,

1984; Josefowicz, 2002), though it has not always been the case ear-

lier. Hansteen was selected as university teacher because of his suc-

cessful participation in a prize competition, answering the question

posed by the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences in 1811: “Can one

explain all the magnetic peculiarities of the Earth from one single mag-

netic axis or is one forced to assume several?” The prize, a gold medal,

was won by Hansteen. In his treatise he meant to demonstrate the

necessity to assume that the Earth possesses two magnetic axes, imply-

ing our globe to be a magnetic quadrupole. The terrestrial magnetism

became his main scientific interest through the rest of his life. For eco-

nomic reasons Hansteen’s one-volume treatise was not published until

1819, but then in a considerably extended form. The book has the title

Untersuchungen über den Magnetismus der Erde (Hansteen, 1819). It

is still quoted in the literature. This work appeared in print only one

year ahead of the discovery of the connection between electricity

and magnetism by his Danish friend and colleague H.C. Ørsted. With

his well-formulated treatise, Hansteen thus obtained a central position

in the development of the geophysical sciences taking place in that

period (see Figure H2).

A Norwegian expedition under the leadership of Hansteen operated

in Siberia in the years 1828–1830, traveling to the Baikal Sea and

crossing the border into China (Hansteen, 1859). One measured the

numerical values of the total magnetic field strength, the inclination,

and the declination. Hansteen found no evidence of any additional

magnetic pole in Siberia. To him this was an enormous disappoint-

ment. Nevertheless, in a letter to H.C. Ørsted of June 21, 1841, he

proudly relates the written statement of Gauss, that to a large extent,

it was the measurements of Hansteen, that had made Gauss devote

himself to the study of magnetism.

Furthermore, Hansteen also made contributions to the investigation

of northern light phenomena (Hansteen, 1825, 1827) as indicated in

Figure H3. Related to his extensive studies of the Earth’s magnetic

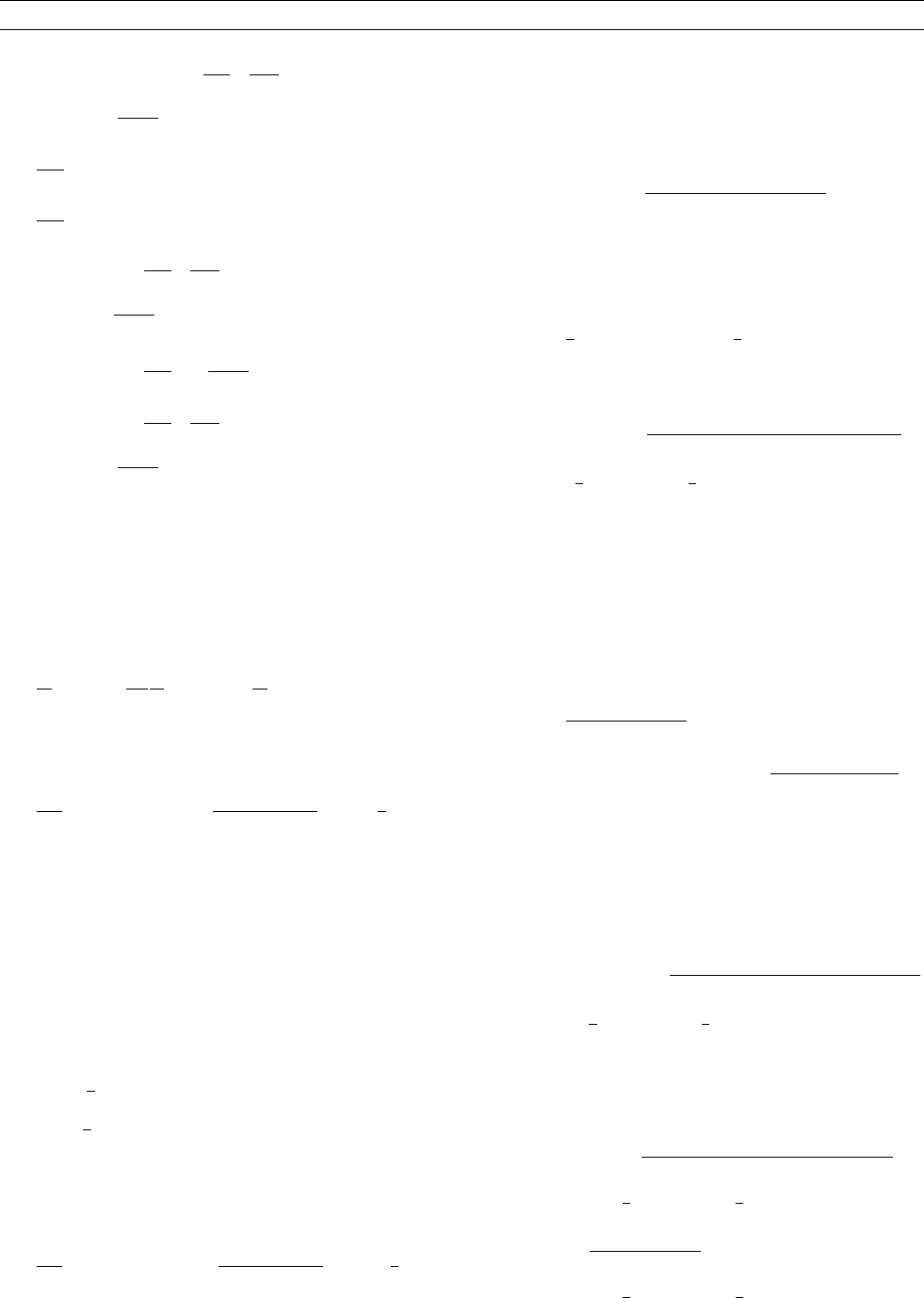

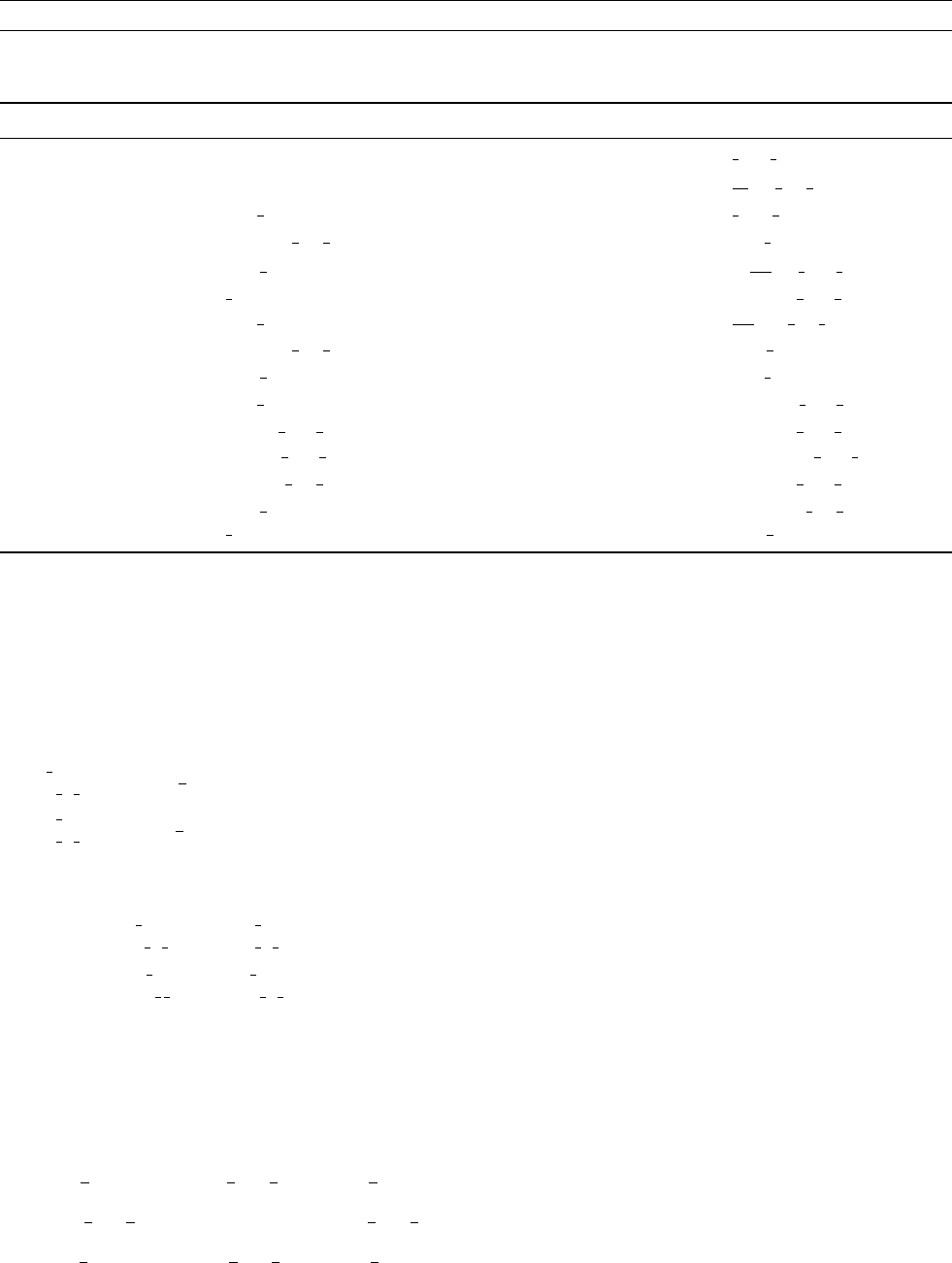

Figure H2 Christopher Hansteen, drawn by C.W. Eckersberg

ca. 1828. Shown is also an instrument constructed by Hansteen

for the determination of the magnetic intensity. It exploits the fact

that a magnetic needle suspended in a magnetic field, when set in

motion; its movement in time will among other factors depend on

the field strength. This device received international acclaim and

was used during the so-called Magnetic Crusade (Cawood, 1979).

376 HANSTEEN, CHRISTOPHER (1784–1873)

field he claimed that the center of the auroral ring to be situated some-

where north of Hudson’ s bay (Brekke, 1984).

At the meeting of the Scandinavian natural scientists in Stockholm

in 1842, Christopher Hansteen gave a talk on the development of the

theory of terrestrial magnetism (Hansteen, 1842). He points to the dis-

covery of Ørsted of the connection between magnetism and electricity

as a possible way to explain the interplay between the processes in

Earth ’s interior and the terrestrial magnetic phenomena. The modern

dynamo theory is a development of this highly intuitive idea.

The scientific results from the Siberian expedition were published as

late as 1863 (Hansteen and Due, 1863). It represents a dignified finish

to Christopher Hansteen ’ s contributions to this part of geoscience.

It deserves attention that Christopher Hansteen was also active as a

nation build er in the first 50 years after 1814 of Norwegian indepen-

dence. Important subjects of his activities were the mapping of the

Norwegian costal area together with inland triangulation, exact time

determination, and many years of almanac edition, to mention just a

few of his undertakings.

Johannes M. Hansteen

Bibliogr aph y

Brekke, A., 1984. On the evolution in history of the concept of the

auroral oval. Eos, Transactions of the American Geophysical

Union , 65 : 705–707.

Cawood, J., 1979. The magnetic crusade: science and politics in the

early Victorian Britain. Isis , 70: pp. 493– 518.

Hansteen, C., 1819. Untersuchungen über den Magnetismus der Erde.

Erster Teil, Christiania: J. Lehman and Chr. Gröndal.

Hansteen, C., 1825. Fors g til et magnetisk Holdningsk art. Mag.

Naturvidensk , 2 : pp. 203–212.

Hansteen, C., 1827. On the polar light, or aurora borealis and australis.

Philos. Mag. Ann. Philos , New Ser., 2 : 333– 334.

Hansteen, C., 1842. Historisk Fremstilling af hvad den fra det

forloebne Seculu ms Begyndelse til vor Tid er udrettet for Jordmag-

netismens Theorie. In Proceedings of the Third Meeting of the

Scandinavian Natural Scientists, Stockholm, pp. 68– 80.

Hansteen, C., 1859. Reiseerindringer,Chr.T nsbergs Forlag, Christiania.

Hansteen, C., and Due, C. 1863. Resultate Magnetischer, Astronom-

ischer und Meteorologischer Beobachtungen auf einer Reise nach

dem Östlichen Sibirien in den Jahren 1828 – 1830. Christiania

Academy of Sciences.

Josefowicz, J.G., 2002. Mitteilungen der Gauss-Gesellschaft 39:

pp. 73– 86.

HARMONICS, SPHERICAL

Intr oduc tion

Spherical harmonics are solutions of Laplace’ s equati on

]

2

V

] x

2

þ

]

2

V

] y

2

þ

]

2

V

] z

2

¼ 0 (Eq. 1)

in three dimensions, and they are collected together as homogeneous

polynomials of degree l , with 2 l þ 1 in each group. The simplest sphe-

rical harmonics are the three Cartesi an coordinates x, y, z , which are

three homogeneous polynomials of degree 1. Inverse distance 1 =r

satisfies Laplace ’s equation everywhere, except at the point r ¼ 0,

forming a spherical harmonic of degree – 1, and the Cartesian deriva-

tives of inverse distance generate spherical harmonics of higher degree

(and order). Because inverse distance is the potential function for grav-

itation, electric, and magnetic fields of force, the theory of spherical

harmonics has many important applications.

It is a simple matter to observe that on taking the gradient of

Laplace ’ s equation (1), that if V is a solution, then so also is the

vector r V , and also the tensor rðr V Þ, showing clearly the need to

consider vector and tensor spherical harmonics. As a simple example,

the gradients of the Cartesian coordinates x; y ; z , lead to i; j; k ; as vec-

tor spherical harmonics, and gradients of x i; x j; x k ; yi;...; lead to

Cartesian tensors ii ; ij ; ik ; ji ;... as tensor spherical harmonics.

With increasing interest in atomic structure and electron spin, the

study of Laplace ’s equation in four dimensions,

]

2

V

]p

2

þ

]

2

V

]q

2

þ

]

2

V

]r

2

þ

]

2

V

]s

2

¼ 0; (Eq. 2)

which is satisfied by 1

ð p

2

þ q

2

þ r

2

þ s

2

Þ and its derivatives,

is important. The solution uses surface spherical harmonics from

Eq. (1), and “spin weighted ” associated Legendre functions.

Spherical polar coordinates

In three dimensions, the spherical polar coordinates of a point P on the

surface of the sphere are r; y; f; where r is the radius of the sphere, y is

the colatitude of the point measured from the point chosen as the north

pole of the coordinate system, and f is the east longitude of the point

measured from the meridian of longitude chosen as the prime meridian,

x ¼ r sin y cos f;

y ¼ r sin y sin f;

z ¼ r cos y: (Eq: 3)

If a spherical harmonic of degree l is denoted V

l

, then in spherical

polars, by virtue of being a homogeneous polynomial of degree l,

we may write

V

l

ðr; y; fÞ¼r

l

S

l

ðy; fÞ (Eq. 4)

and the function S

l

ðy; fÞ is called a surface spherical harmonic of

degree l. From the theory of homogeneous functions,

ðr rÞV

l

¼ r

]V

l

]r

¼ x

]V

l

]x

þ y

]V

l

]y

þ z

]V

l

]z

¼ lV

l

: (Eq. 5)

Conversely, it can be shown that if a function V

l

satisfies Eq. (5), then

it is a homogeneous function of degree l in x; y; z.

The four-dimensional case arises when considering rotations through

and angle w, about an axis of rotation with which is in the direction that

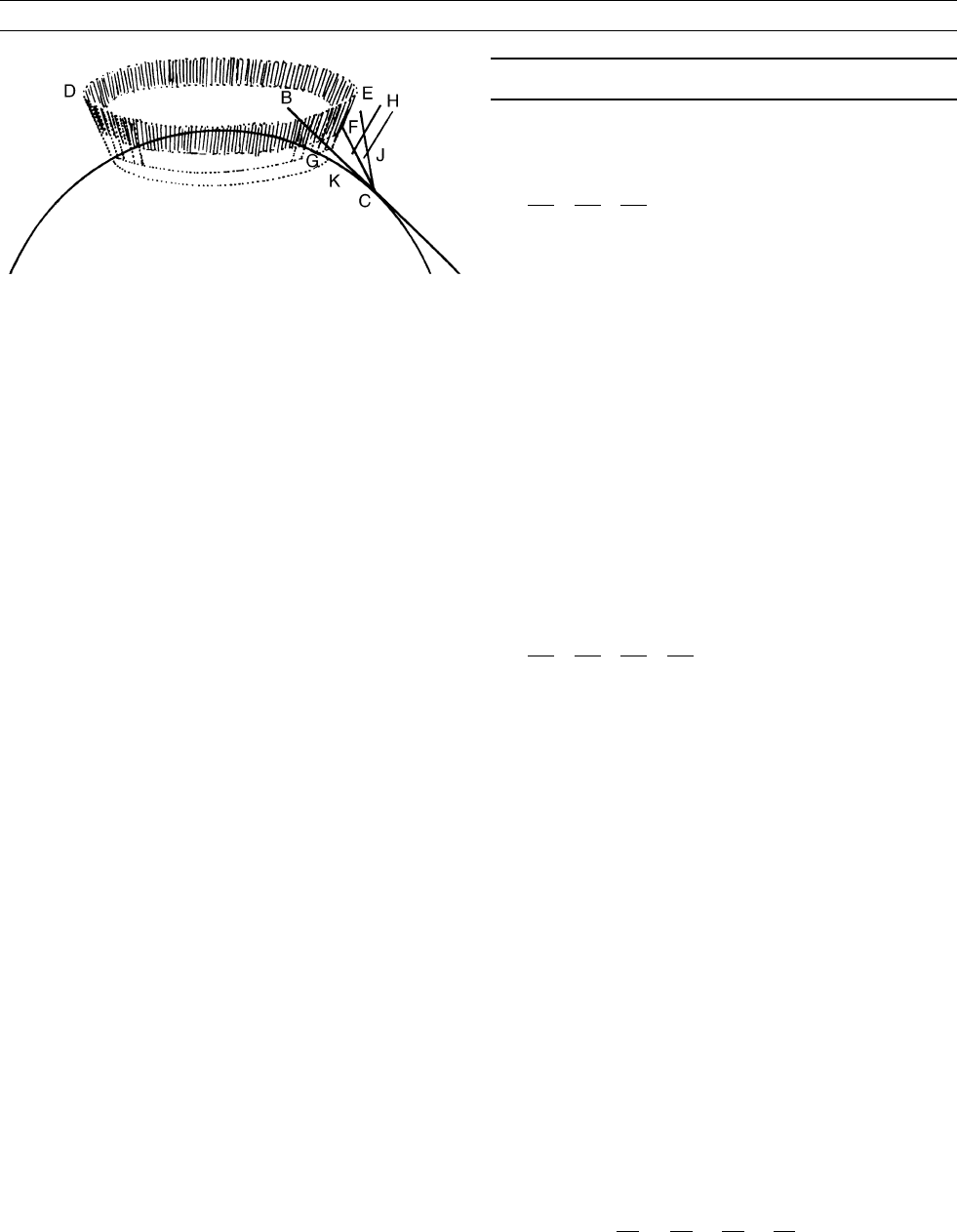

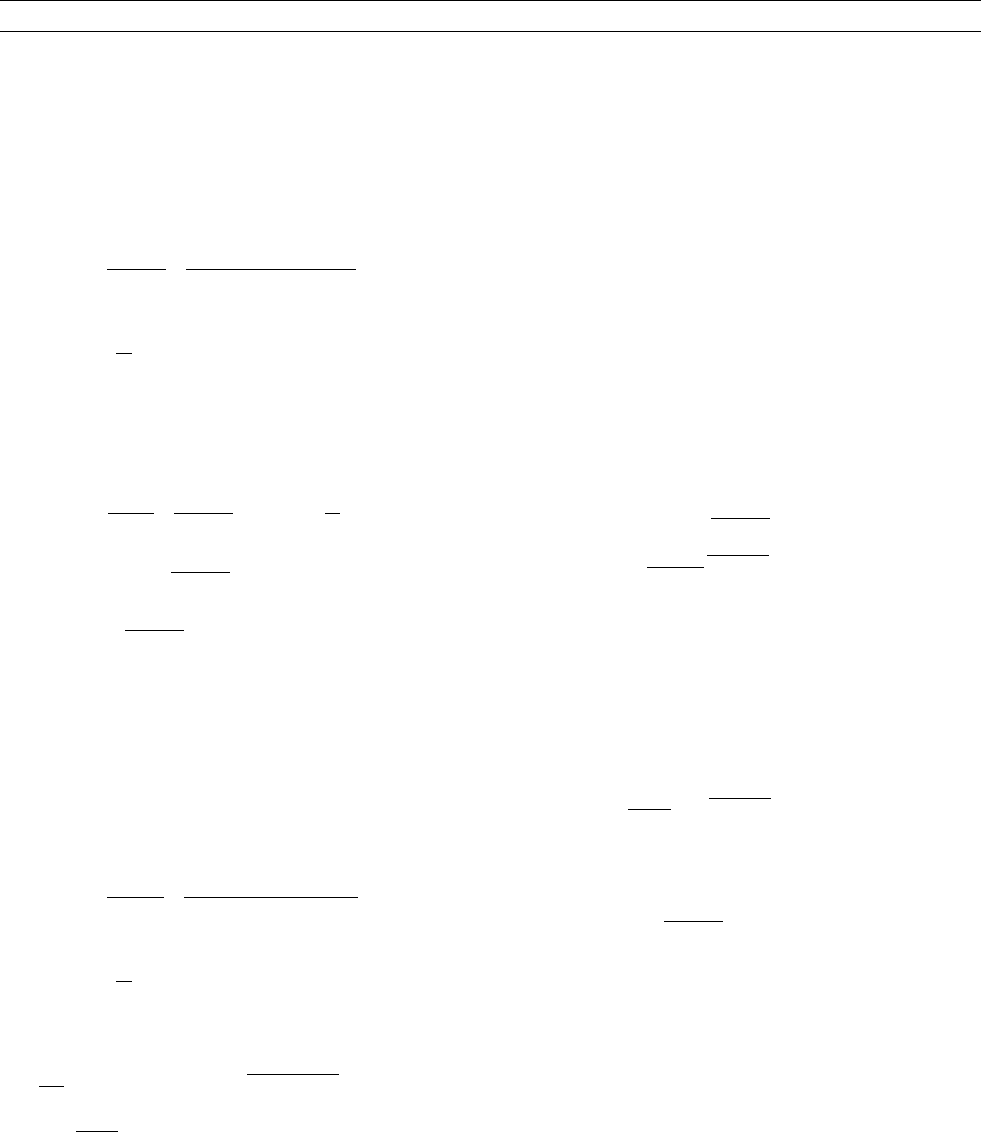

Figure H3 Picture from work of Hansteen (1827) on the concept

of the aurora, showing an auroral ring encircling the polar cap. The

figure is presumably one of the first drawings of the auroral ring.

The illustration also demonstrates how to measure the height of

the aurora from one point only.

HARMONICS, SPHERICAL 377

has colatitude u and east longitude v. For rotations, the hypersphere has

unit radius, for we include a value r here, and the four-dimensional

Cartesian coordinates p ; q ; r ; s; are

p ¼ r sin u cos v sin

1

2

w ;

q ¼ r sin u sin v sin

1

2

w ;

r ¼ r cos u sin

1

2

w ;

s ¼ r cos

1

2

w : (Eq: 6)

With r ¼ 1, the coordinates p ; q ; r ; s ; are better known as quaternions.

Separat ion of varia bles

In spherical polar coordinate s, the Laplacian r

2

V is

r

2

V ¼

1

r

2

]

] r

r

2

] V

] r

þ

1

sin y

]

] y

sin y

] V

] y

þ

1

sin

2

y

]

2

V

] f

2

:

(Eq. 7)

The method of separation of variables is used to solve Laplace ’s equa-

tion in spherical polars. With V ð r ; y; fÞ¼ Rð r ÞS

l

ð y; fÞ; and with

l ð l þ 1 Þ as a constant of separation, then

d

d r

r

2

d R

d r

l ðl þ 1Þ R ¼ 0 ; (Eq. 8)

and

1

sin y

]

] y

sin y

] S

l

] y

þ

1

sin

2

y

]

2

S

l

]f

2

þ l ðl þ 1Þ S

l

¼ 0 : (Eq. 9)

Note that the constant of separation l ð l þ 1 Þ remains unchanged if l is

replaced by l 1.

Radial dependence of the spherical harmonics is given by (8),

R ðr Þ¼ A

l

r

l

þ

B

r

l þ1

: (Eq. 10)

Equation 9 can be solved by further separation of variables, using

S

l

ð y; fÞ¼ Y ð yÞ Fð fÞ , with m

2

as the constant of separat ion,

d

2

F

d f

2

þ m

2

F ¼ 0 ; (Eq. 11)

and

1

sin y

d

d y

sin y

d Y

d y

þ l ð l þ 1 Þ

m

2

sin

2

y

Y ¼ 0 : (Eq. 12)

From Eqs. (7) and (9), the Laplacian of the surface spherical harmonic

S

l

ð y; fÞ is

r

2

S

l

ð y ; f Þ¼

l ð l þ 1Þ

r

2

S

l

ðy ; fÞ (Eq. 13)

Solutions of Eq. (11) are the trigonometric functions cos V and sin V ,

and the complex exponential functions e

iV

and e

iV

. The concept of

“irreducibility ” favors the use of the complex exponential expressions,

because, with the transformation V ! V þ a , the trigonometric func-

tions become mixed,

cos V ! cosð V þ a Þ¼ cos V cos a sin V sin a;

sin V ! sin ð V þ a Þ¼ sin V cos a þ cos V sin a; (Eq: 14)

and are “reducible ” , whereas the complex exponential functions do not

become mixed, and are therefore “irreducible. ”

e

i V

! e

i ðV þ aÞ

¼ e

iV

e

i a

;

e

iV

! e

i ðV þ aÞ

¼ e

i V

e

ia

; (Eq: 15)

Ort hogon ality of surface spherical harmoni cs

A number of properties of spherical harmonics can be established

using only the definition, namely, that they are homogen eous functions

of degree l that satisfy Laplace ’s equation, and specific mathematical

expressions are not required.

Let S

l

ðx ; y; zÞ and S

L

ðx ; y; zÞ be two surface spherical harmonics of

degree l and L respectively. A vector F is defined by

F ¼ðrS

l

ÞS

L

S

l

ðrS

L

Þ; (Eq. 16)

when, by Eq. (13), the divergence of F is

r F ¼

1

r

2

l ð l þ 1Þ S

l

S

L

þ Lð L þ 1 ÞS

l

S

L

;

¼

1

r

2

ðL l ÞðL þ l þ 1 ÞS

l

S

L

: (Eq: 17)

Gauss ’s theorem, applied to a spherical surface and the enclosed sphe-

rical volume, is

ZZZ

spherical

volume

r F d v ¼

ZZ

spherical

surface

F d S ; (Eq. 18)

where, in this case, d S ¼ r

2

e

r

sin y d y df ; and e

r

is the unit radial vec-

tor. The vector F has no radial component, and therefore the spherical

surface integral is zero, and the volume integral, after integrating with

respect to radius, reduces to

Z

r

0

Z

2p

0

Z

p

0

r F d v ¼ðL l Þð L þ l þ 1 Þ

Z

r

0

d r

Z

2p

0

Z

p

0

S

l

ð y; f ÞS

L

ðy ; fÞ sin yd y df ;¼ 0;

and therefo re, when l 6¼ L or when l 6¼L 1, then

Z

2p

0

Z

p

0

S

l

ðy ; f Þ S

L

ðy ; f Þ sin y dy d f ¼ 0 : (Eq. 19)

Le gendre polynom ials

In the case m ¼ 0, the spherical harmonics are independent of longi-

tude f and are said to be “ zonal” . The differential equation is obtained

from Eq. (12) with m ¼ 0, namely

ð1 m

2

Þ

d

2

Y

d m

2

2 m

d Y

d m

þ l ð l þ 1 Þ Y ¼ 0; (Eq. 20)

The factor ð1 m

2

Þ of the second derivative shows that the solution

has singularities at m ¼1, corresponding to colatitudes y ¼ 0

and y ¼ p, at the north and south poles respectively of the chosen

reference frame. The two independent solutions of Eq. (20) are

378 HARMONICS, SPHERICAL

Legendre functions of the first and second kind, P

l

ð mÞ and Q

l

ðm Þ,

respectively, where

P

l

ð mÞ¼

1

2

l

l !

d

d m

l

ðm

2

1 Þ

l

; (Eq. 21)

Q

l

ð mÞ¼ P

l

ðm Þ ln

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1 þ m

1 m

s

2 l 1

1 l

P

l 1

ð mÞ

2 l 5

3ð l 1Þ

P

l 3

ð mÞ

2 l 9

5 ðl 2Þ

P

l 5

ð m Þþ...; m

jj

< 1: (Eq. 22)

Legendre polynomials are orthogonal over the range 1 m 1,

and the normalization of P

l

ð mÞ has been chosen so that

1

2

Z

1

1

P

l

ð m ÞP

L

ðm Þ dm ¼

1

2 l þ 1

d

L

l

; (Eq. 23)

where d

L

l

is the Kronecker delta.

The descending power series expansion for the Legendre polyno-

mials is

P

l

ð mÞ¼

ð 2 l Þ!

2

l

l !l !

m

l

l ð l 1Þ

2 ð2 l 1Þ

m

l 2

þ

l ðl 1 Þðl 2Þðl 3 Þ

2 4 ð 2l 1 Þð2l 3 Þ

m

l 4

...

; (Eq : 24)

and the first few are

P

0

¼ 1; P

1

¼ m ; P

2

¼

1

2

ð 3 m

2

1 Þ;

P

3

¼

1

2

ð 5 m

3

3 mÞ; P

4

¼

1

8

ð35 m

4

30m

2

þ 3 Þ: (Eq : 25)

Note that P

l

ð 1Þ¼ 1 and that P

l

ð 1Þ¼ð1 Þ

l

for all values of l.

A series expansion for Legendre functions of the second kind,

Q

l

ðm Þ is

Q

l

ð mÞ¼

2

l

l !l !

ð2 l þ 1 Þ!

1

m

l þ 1

þ

ðl þ 1Þð l þ 2 Þ

2 ð2 l þ 3Þ

1

m

l þ 3

þ

ð l þ 1 Þðl þ 2Þð l þ 3 Þðl þ 4Þ

2 4 ð 2l þ 3 Þð2l þ 5 Þ

1

m

l þ 5

þ...

:

Neum ann’s fo rmula

Neumann’ s formu la, given by

X

1

l ¼0

ð2 l þ 1Þ P

l

ð zÞ Q

l

ðm Þ¼

1

m z

; m

jj

> z

jj

; (Eq. 26)

can be used to show that the recurrence relations for Q

l

ð m Þ are the

same as those for the Legend re polynomials P

l

ðm Þ. Therefore, round-

ing errors, regarded as proportional to Q

l

ðm Þ, in the generation of

Legendre polynomials using recurrence relations, are likely to become

large at or near the poles. Neumann ’s formula (26) can also be written

in the form

Q

l

ð mÞ¼

1

2

Z

1

1

P

l

ð zÞ

m z

dz ; (Eq. 27)

which can be used to derive the Christoffel formula (22) for Q

l

ð mÞ.

Gener atin g function

The function

V ðr ; m Þ¼

1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1 2 mh þ h

2

p

¼

X

1

l ¼ 0

h

l

P

l

ð cos yÞ (Eq. 28)

is the generating function for the Legendre polynomials.

If a gravitating particle of mass m is moved from the origin a distance

d along the z- axis, regarded as the pole of a coordinate system, then,

using the cosine rule of trigonometry, the gravitational potential of the

particle (in a region free of gravitating material) is

V ðr ; y Þ¼

Gm

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

r

2

2 rd cos y þ d

2

p

;

V ðr ; y Þ¼

Gm

d

X

1

l ¼0

d

r

l þ 1

P

l

ð cos y Þ; when r > d ;

V ðr ; y Þ¼

Gm

d

X

1

l ¼0

r

d

l

P

l

ðcos y Þ; when r < d : (Eq: 29)

If the potential of a distribution of matter is independent of azimuth

or east longitude, it is said to be zonal. In the case where the poten-

tial of the distribution in a source-free region along the z-axis is

known to be

VðzÞ¼

G

d

X

1

l¼0

a

l

d

z

lþ1

for z > d;

and

VðzÞ¼

G

d

X

1

l¼0

a

l

z

d

l

for z < d; (Eq. 30)

then, from the continuity of the potential, the potential in regions away

from the z-axis is

Vðr; yÞ¼

G

d

X

1

l¼0

a

l

d

r

lþ1

P

l

ðcos yÞ for r > d;

and

Vðr; yÞ¼

G

d

X

1

l¼0

a

l

r

d

l

P

l

ðcos yÞ for r < d : (Eq. 31)

Recurrence relations

Differentiation of the generating function (28) and the Rodrigues for-

mula (21) can be used to derive the recurrence relations for Legendre

polynomials. The more important ones are

Bonnet's formula ðl þ 1ÞP

lþ1

ð2l þ 1ÞmP

l

þ lP

l1

¼ 0;

(Eq. 32)

dP

lþ1

dm

¼ m

dP

l

dm

þðl þ 1ÞP

l

; (Eq. 33)

and

ð2l þ 1ÞP

l

¼

dP

lþ1

dm

dP

l1

dm

: (Eq. 34)

HARMONICS, SPHERICAL 379

Multipl e derivativ es of inverse distan ce

Parameters x and are required, and they are defined by

x ¼

1

ffiffiffi

2

p

ð x þ iy Þ¼

1

ffiffiffi

2

p

r sin ye

if

;

¼

1

ffiffiffi

2

p

ð x iyÞ¼

1

ffiffiffi

2

p

r sin y e

if

: (Eq : 35)

Partial derivatives with respect to x and are

] f

] x

¼

1

ffiffiffi

2

p

] f

]x

i

] f

] y

;

] f

]

¼

1

ffiffiffi

2

p

] f

] x

þ i

] f

] y

: (Eq. 36)

The solid spherical harmonic, inverse distance, is

1

r

¼

1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

x

2

þ y

2

þ z

2

p

¼

1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

z

2

2x

p

; (Eq. 37)

with multiple derivatives

]

] x

m

1

r

¼ 1 3 5 ...ð 2 m 1Þ

m

r

2 mþ1

;

]

]

m

1

r

¼ 1 3 5 ...ð2 m 1 Þ

x

m

r

2mþ 1

: (Eq : 38)

The ðl mÞ

th

derivative of 1

r

2mþ 1

with respect to z is

ð 1 Þ

l m

]

] z

l m

1

r

2 mþ 1

¼ð2 m þ 1 Þð2 m þ 3 Þ...ð2 l 1Þ

z

l m

r

2 l þ 1

ð l mÞðl m 1Þ

2 ð2 l 1 Þ

z

l m2

r

2l 1

þ

ð l m Þðl m 1 Þðl m 2Þð l m 3 Þ

2 4 ð2 l 1Þð2 l 3Þ

z

l m 4

r

2l 3

...

(Eq. 39)

The required 2l þ 1 independent spherical harmonics of degree l are

obtained by differentiating (38) partial ly with respect to z some

l m times, for m ¼l ;l þ 1;... 1; 0; 1;...; l 1; l, when, with

the substitutions z ¼ r cos y and m ¼ cos y,

ð 1 Þ

l m

]

]

m

]

] z

l m

1

r

¼

1

r

l þ mþ1

ð l m Þ!

2

l

l !

x

m

ð 2l Þ!

ðl mÞ!

m

l m

l ð 2l 2 Þ!

ðl m 2Þ!

m

l m 2

þ

l ð l 1 Þð2 l 4Þ!

2 ð l m 4 Þ!

m

l m 4

...

: (Eq : 40)

The series in (40) is the ð l þ m Þ

th

derivative of a series which can be

summed by the binomial theorem, and hence

ð 1 Þ

l m

]

] x

þ i

]

] y

m

]

]z

l m

1

r

¼ð1 Þ

m

e

i mf

r

l þ1

ð l m Þ!

2

l

l !

ð1 m

2

Þ

m=2

d

d m

l þm

ð m

2

1 Þ

l

:

(Eq. 41)

Ferrer s normali zed functi ons

Associated Legendre functions are solutions of Eq. (12), and are given

in the first instance as the Ferrers normalized functions P

l ; m

ðm Þ,

(Ferrers, 1897), defined by

P

l ; m

ðm Þ¼ð1 m

2

Þ

m

=

2

d

d m

m

P

l

ðm Þ;

¼

1

2

l

l !

ð 1 m

2

Þ

m=2

d

d m

l þ m

ðm

2

1 Þ

l

; for l m

jj

(Eq. 42)

See Table H1 for a list of these functions.

Applying Leibnitz ’s theorem for multiple derivatives of

ð m 1 Þ

l

ðm þ 1 Þ

l

hi

in the function P

m

l

ð mÞ and then re-arranging

terms, gives the expression in terms of P

m

l

ð m Þ,

P

l ; m

ðm Þ¼

1

2

l

l !

ð 1 m

2

Þ

m

=

2

d

d m

l m

ð m

2

1 Þ

l

¼ð1 Þ

m

ð l mÞ!

ð l þ mÞ!

P

l ;m

ð mÞ: (Eq. 43)

Both Eqs. (42) and (43) can be used with positive or negative values of

m . Caution is needed with definitions based on m

jj

. Equations (42) and

(43) can be used to derive the normalization integral for associated

Legend re functions with Ferrers normalization,

1

2

Z

1

1

P

l ;m

ð mÞ P

L ;m

ð mÞ d m ¼

1

2 l þ 1

ð l þ m Þ!

ð l m Þ!

d

L

l

: (Eq. 44)

Su rface spherical harmoni cs

Surface spherical harmonics Y

m

l

ð y ; f Þ are defined in terms of the

Ferrers normalized functions P

l ;m

ð cos y Þ

Y

m

l

ðy ; f Þ¼ð1 Þ

m

e

imf

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð2l þ 1 Þ

ðl m Þ!

ðl þ m Þ!

s

P

l ;m

ðcos y Þ;

¼ð1Þ

m

e

imf

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð2l þ 1 Þ

ðl m Þ!

ðl þ m Þ!

s

1

2

l

l !

ð1 m

2

Þ

m=2

d

dm

l þm

ðm

2

1 Þ

l

:

(Eq. 45)

The initial factor ð 1Þ

m

is now used following the influential work

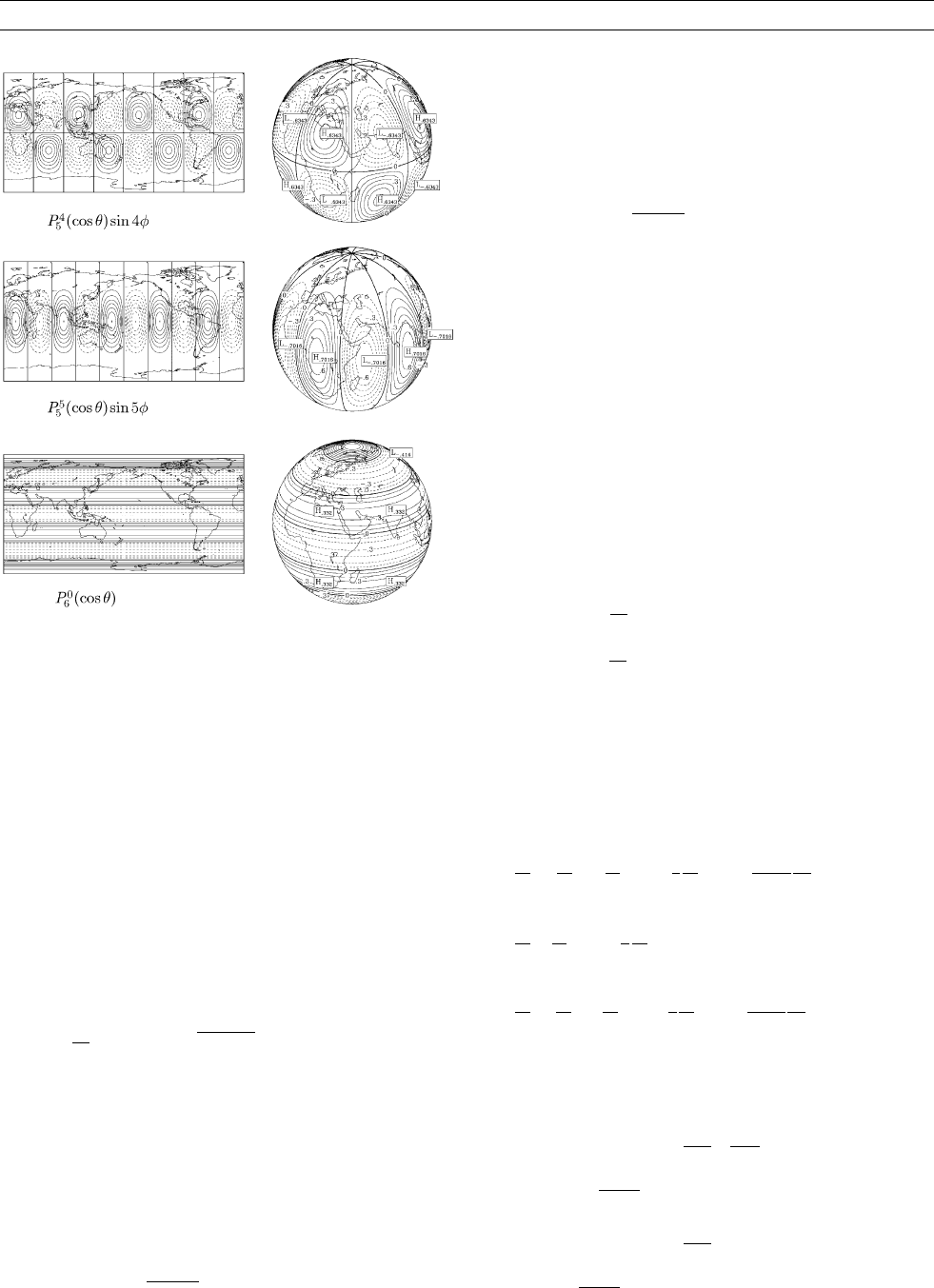

of Condon and Shortley (1935). See Table H1 for a list of the

functions Y

m

l

ðy ; f Þ , and Figure H4 for tesseral, sectorial, and zonal

harmonics.

Therefore, in terms of multiple derivatives of inverse distance, from

Eqs. (41) and (45),

1

r

l þ1

Y

m

l

ð y ; f Þ

¼ð1 Þ

l m

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2 l þ 1

ðl mÞ!ð l þ mÞ!

s

]

] x

þ i

]

] y

m

]

] z

l m

1

r

(Eq. 46)

The series expression for surface spherical harmonics is

Y

m

l

ðy ; f Þ¼

ð2 l Þ!

2

l

l !

e

i mf

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2 l þ1

ðl mÞ!ð l þ m Þ!

s

ð1 m

2

Þ

m

=

2

m

l m

ð l m Þðl m 1 Þ

2 ð 2l 1 Þ

m

l m 2

þ

ðlmÞðlm1Þðlm2Þðl m 3Þ

2 4ð2l 1Þð2l 3Þ

m

nm4

...

:

(Eq. 47)

380 HARMONICS, SPHERICAL

In the special case m ¼ 0 ; from Eq. (45),

Y

0

l

ð y ; f Þ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð2 l þ 1Þ

p

1

2

l

l !

d

d m

l

ðm

2

1 Þ

l

¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð2 l þ 1Þ

p

P

l

ð mÞ;

(Eq. 48)

Changing the sign of m in Eq. (45) and making use of Eq. (43), gives

Y

m

l

ð y; fÞ¼ð1 Þ

m

e

im f

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð2 l þ 1 Þ

ðl þ mÞ!

ðl mÞ!

s

P

l ; m

ð cos y Þ;

¼ e

im f

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð2 l þ 1 Þ

ðl mÞ!

ðl þ mÞ!

s

P

l ;m

ð cos y Þ;

¼ð1 Þ

m

Y

m

l

ð y; fÞ: (Eq. 49)

Note that x; z; are related to the surface spherical harmonics of the

first degree by

Y

1

1

ðy ; f Þ¼

ffiffiffi

6

p

2

sin ye

if

¼

ffiffiffi

3

p

r

x;

Y

0

1

ðy ; f Þ¼

ffiffiffi

3

p

cos y ¼

ffiffiffi

3

p

r

z ;

Y

1

1

ðy ; f Þ¼

ffiffiffi

6

p

2

sin ye

i f

¼

ffiffiffi

3

p

r

: (Eq: 50)

The normalization and orthogonality integral is

1

4p

Z

2p

0

Z

p

0

Y

m

l

ðy ; f ÞY

M

L

ð y ; f Þ sin yd y df ¼ d

L

l

d

M

m

: (Eq. 51)

In theoretical physics texts, it is common practice to replace the initial

factor 1

=

4 p in Eq. (51) by applying a factor

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1

=

4p

p

to the surface

spherical harmonic Y

m

l

ðy; fÞ. This factor is sometimes broken up into

a factor

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1=2p

p

applied to the associated Legendre function and a fac-

tor

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1

=

2

p

applied to the complex exponential part.

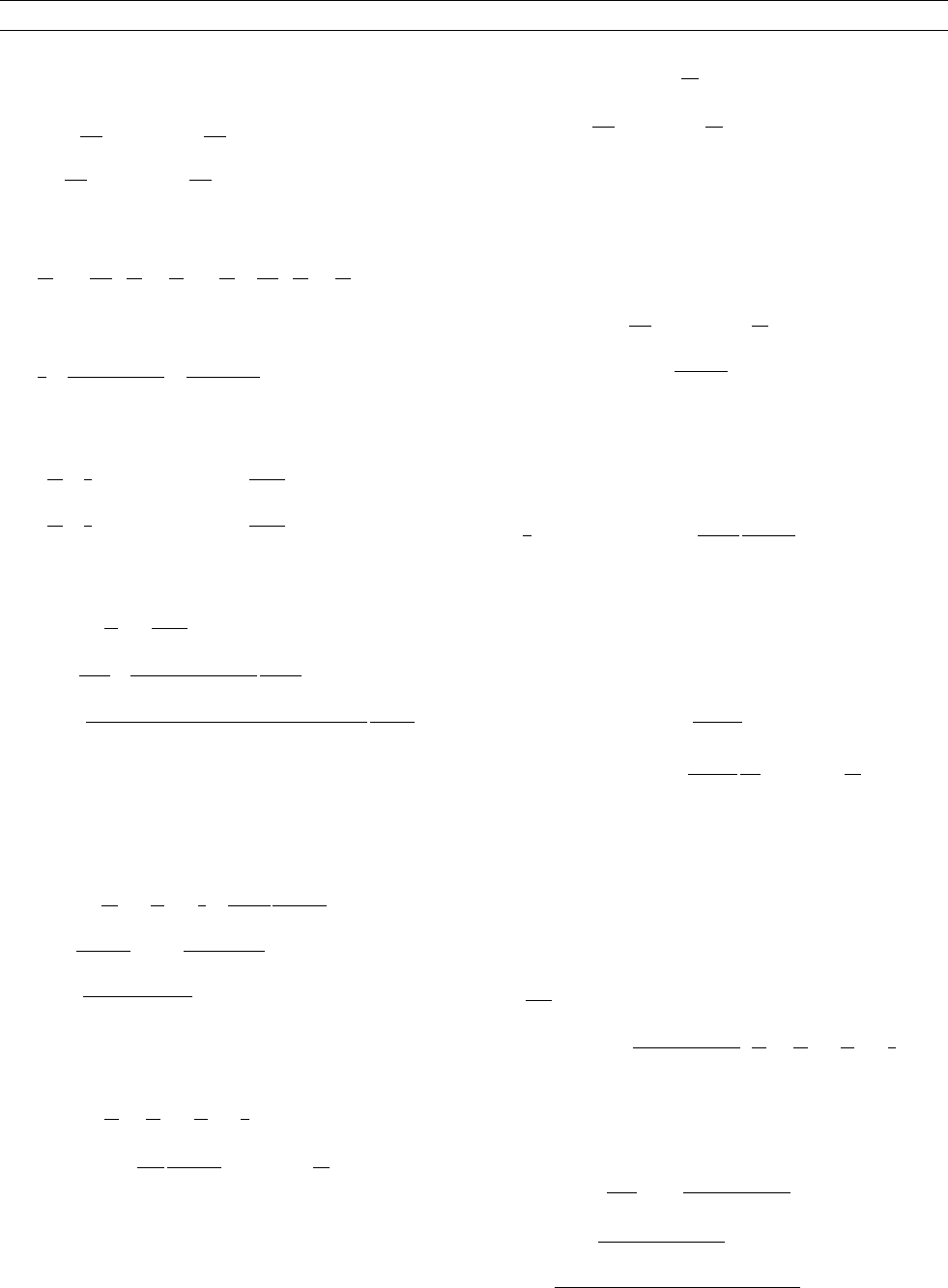

Table H1 List of associated Legendre functions P

m

l

ðcos y Þ in Ferrers normalization and Schmidt normalization to degree and order six,

and the corresponding surface spherical harmonics Y

m

l

ðy; fÞ, normalized after Condon and Shortley

lmFerrers P

l;m

ðcos yÞ Schmidt P

m

l

ðcos yÞ Y

m

l

ðy; fÞ

00 1 1 1

10 c c

ffiffiffi

3

p

c

11 s s

ffiffi

6

p

2

se

if

20

1

2

ð3c

2

1Þ

1

2

ð3c

2

1Þ

ffiffi

5

p

2

ð3c

2

1Þ

21 3sc

ffiffiffi

3

p

sc

ffiffiffiffi

30

p

2

sce

if

22

3s

2

ffiffi

3

p

2

s

2

ffiffiffiffi

30

p

4

s

2

e

2if

30

1

2

ð5c

3

3cÞ

1

2

ð5c

3

3cÞ

ffiffi

7

p

2

ð5c

3

3cÞ

31

3

2

sð5c

2

1Þ

ffiffi

6

p

4

sð5c

2

1Þ

ffiffiffiffi

21

p

4

sð5c

2

1Þe

if

32

15 s

2

c

ffiffiffiffi

15

p

2

s

2

c

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

210

p

4

s

2

c e

2if

33

15 s

3

ffiffiffiffi

10

p

4

s

3

ffiffiffiffi

35

p

4

s

3

e

3if

40

1

8

ð35c

4

30c

2

þ 3Þ

1

8

ð35c

4

30c

2

þ 3Þ

3

8

ð35c

4

30c

2

þ 3Þ

41

5

2

sð7c

3

3cÞ

ffiffiffiffi

10

p

4

sð7c

3

3cÞ

3

ffiffi

5

p

4

sð7c

3

3cÞe

if

42

15

2

s

2

ð7c

2

1Þ

ffiffi

5

p

4

s

2

ð7c

2

1Þ

3

ffiffiffiffi

10

p

8

s

2

ð7c

2

1Þe

2if

43

105 s

3

c

ffiffiffiffi

70

p

4

s

3

c

3

ffiffiffiffi

35

p

4

s

3

ce

3if

44

105 s

4

ffiffiffiffi

35

p

8

s

4

3

ffiffiffiffi

70

p

16

s

4

e

4if

50

1

8

ð63c

5

70c

3

þ 15cÞ

1

8

ð63c

5

70c

3

þ 15cÞ

ffiffiffiffi

11

p

8

ð63c

5

70c

3

þ 15cÞ

51

15

8

sð21c

4

14c

2

þ 1Þ

ffiffiffiffi

15

p

8

sð21c

4

14c

2

þ 1Þ

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

330

p

16

sð21c

4

14c

2

þ 1Þe

if

52

105

2

s

2

ð3c

3

cÞ

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

105

p

4

s

2

ð3c

3

cÞ

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2310

p

8

s

2

ð3c

3

cÞe

2if

53

105

2

s

3

ð9c

2

1Þ

ffiffiffiffi

70

p

16

s

3

ð9c

2

1Þ

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

385

p

16

s

3

ð9c

2

1Þe

3if

54

945 s

4

c

3

ffiffiffiffi

35

p

8

s

4

c

3

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

770

p

16

s

4

ce

4if

55

945 s

5

3

ffiffiffiffi

14

p

16

s

5

3

ffiffiffiffi

77

p

16

s

5

e

5if

60

1

16

ð231c

6

315c

4

þ 105c

2

5Þ

1

16

ð231c

6

315c

4

þ 105c

2

5Þ

ffiffiffiffi

13

p

16

ð231c

6

315c

4

þ 105c

2

5Þ

61

21

8

sð33c

5

30c

3

þ 5cÞ

ffiffiffiffi

21

p

8

sð33c

5

30c

3

þ 5cÞ

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

546

p

16

sð33c

5

30c

3

þ 5cÞe

if

62

105

8

s

2

ð33c

4

18c

2

þ 1Þ

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

210

p

32

s

2

ð33c

4

18c

2

þ 1Þ

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1365

p

32

s

2

ð33c

4

18c

2

þ 1Þe

2if

63

315

2

s

3

ð11c

3

3cÞ

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

210

p

16

s

3

ð11c

3

3cÞ

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1365

p

16

s

3

ð11c

3

3cÞe

3if

64

945

2

s

4

ð11c

2

1Þ

3

ffiffi

7

p

16

s

4

ð11c

2

1Þ

3

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

182

p

32

s

4

ð11c

2

1Þe

4if

65

10395 s

5

c

3

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

154

p

16

s

5

c

3

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1001

p

16

s

5

ce

5if

66

10395 s

6

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

462

p

32

s

6

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

3003

p

32

s

6

e

6if

HARMONICS, SPHERICAL 381

The ð 2l þ 1 Þ independent solutions of degree l of Laplace ’s equa-

tion, with no logarithmic singularity at the poles, are the ð 2 l þ 1 Þ solid

spherical harmonics,

r

l

Y

m

l

ð y ; f Þ; where m ¼l ;l þ 1;... l 1 ; l : (Eq. 52)

Given a sufficient ly differentiable function f ð y ; f Þ over the surface of

a sphere, it can be written as a finite linear combination of surface

spherical harmonics

f ðy ; f Þ¼

X

L

l ¼ 0

X

n

m¼ n

f

lm

Y

m

l

ðy ; f Þ; (Eq. 53)

where the complex constant coefficients f

lm

are determined using

f

lm

¼

1

4 p

Z

2p

0

Z

p

0

f ðy ; f ÞY

m

l

ðy ; f Þ sin y dy d f: (Eq. 54)

Vector spherical harmonics are require d for the representation of vec-

tor fields over the surface of a sphere.

Schmi dt nor malize d functio ns

The Schmidt normalized associ ated Legendre functions P

m

l

ðcos yÞ are

defined by

P

0

l

ðcos y Þ¼P

l ;0

ð cos yÞ;

P

m

l

ðcos yÞ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2

ð l m Þ!

ð l þ m Þ!

s

P

l ;m

ðcos y Þ; m 6¼ 0 : (Eq : 55)

They are normalized to have the same value as the Legendre polyno-

mials and they are widely used in geomagnetism in accordance with

a resolution of the Association of Terrestrial Magnetism and Electricity

of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (Goldie and

Joyce, 1940). Following Schmidt (1899), it is convenient to write the

two formulae of Eq. (55) in the form

P

m

l

ð cos y Þ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

e

m

ð l mÞ!

ð l þ mÞ!

s

P

l ;m

ð cos y Þ (Eq. 56)

in which the parameter e

m

is defined by

e

0

¼ 1; e

1

¼ e

2

¼ e

3

¼...¼ 2; (Eq. 57)

or alternatively, in terms of the Kronecker delta function

e

m

¼ 2 d

0

m

: (Eq. 58)

For expressions f ðy ; f Þ involving real variables only, we may write it

as a linear combination of Schmidt normalized functions,

f ð y ; f Þ¼

X

N

l ¼0

g

m

l

cos m f þ h

m

l

sin mf

P

m

l

ð cos y Þ (Eq. 59)

where the constant coefficient where the constants g

m

n

and h

m

n

are

determined using

g

m

l

¼ð2l þ 1 Þ

1

4 p

Z

2p

0

Z

p

0

f ðy ; f Þ P

m

l

ðcos y Þ cos mf sin y d yd f

h

m

l

¼ð2 l þ 1 Þ

1

4p

Z

2p

0

Z

p

0

f ð y; fÞ P

m

l

ð cos y Þ sin m f sin yd y df :

(Eq. 60)

Re currence relati ons

Recurrence relations for spherical harmonics are derived using deriva-

tives of Eq. (46) and derivatives of the recurrence relations for

Legend re polynomials. The spherical polar components for the deriva-

tives used in Eq. (46) defining Y

m

n

ðy ; f Þ , are

] f

] x

þ i

] f

] y

¼

]f

] r

sin y þ

1

r

] f

] y

cos y þ

i

r sin y

] f

] f

e

if

; (Eq. 61)

] f

] z

¼

] f

] r

cos y

1

r

]f

] y

sin y ; (Eq. 62)

] f

] x

i

] f

] y

¼

] f

] r

sin y þ

1

r

] f

] y

cos y

i

r sin y

] f

] f

e

if

: (Eq. 63)

The basic set of recurrence relations in which the degree n and order

m on the left hand side are changed by – 1, 0, or þ1 on the right-hand

side are

ðl þ 1Þsin yY

m

l

þ cos y

]Y

m

l

]y

m

sin y

Y

m

l

¼ e

if

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2l þ 1

2l þ 3

ðl þ m þ 1Þðl þ m þ 2Þ

r

Y

mþ1

lþ1

; (Eq: 64)

ðl þ 1Þcos yY

m

l

sin y

]Y

m

l

]y

¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2l þ 1

2l þ 3

ðl m þ 1Þðl þ m þ 1Þ

r

Y

m

lþ1

; (Eq: 65)

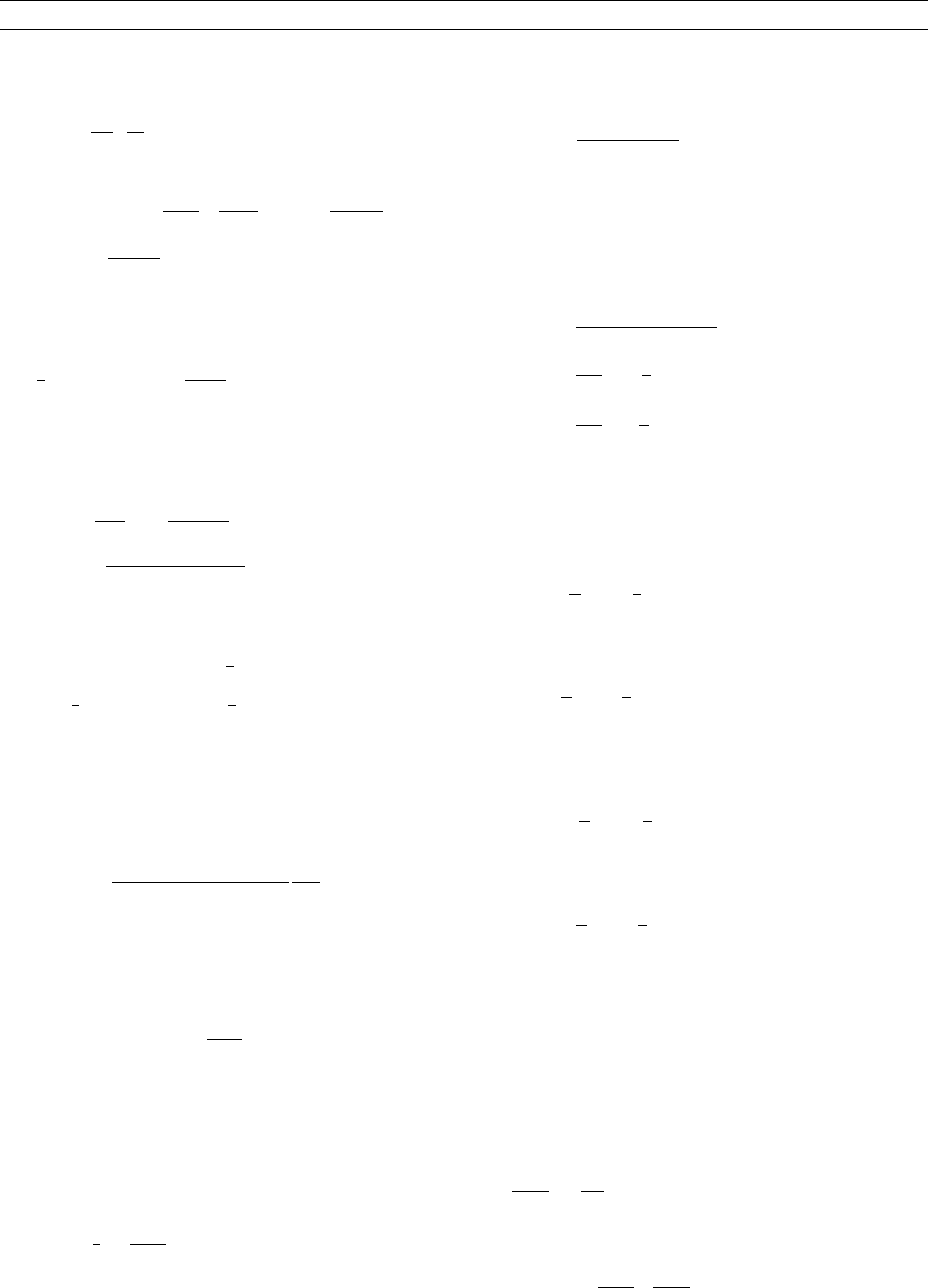

Figure H4 Zonal surface spherical harmonics are of the form

P

0

l

ðcos yÞ; sectorial surface spherical harmonics are of the form

P

l

l

ðcos yÞcos lf and P

l

l

ðcos yÞsin lf. Tesseral surface spherical

harmonics are those that are neither zonal nor sectorial.

382 HARMONICS, SPHERICAL

ðl þ 1 Þ sin y Y

m

l

þ cos y

] Y

m

l

] y

þ

m

sin y

Y

m

l

¼e

i f

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2l þ 1

2l þ 3

ð l m þ 1Þðl m þ 2 Þ

r

Y

m 1

l þ 1

; (Eq : 66)

] Y

m

l

] y

m cot y Y

m

l

¼ e

i f

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð l mÞðl þ m þ 1Þ

p

Y

mþ 1

l

; (Eq. 67)

] Y

m

l

] y

þ m cot y Y

m

l

¼e

if

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð l þ m Þðl m þ 1 Þ

p

Y

m1

l

; (Eq. 68)

l sin y Y

m

l

þ cos y

] Y

m

l

] y

m

sin y

Y

m

l

¼ e

if

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2 l þ 1

2 l 1

ð l m Þðl m 1 Þ

r

Y

mþ1

l 1

; (Eq : 69)

l cos y Y

m

l

sin y

] Y

m

l

] y

¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2 l þ 1

2 l 1

ðl þ mÞðl m Þ

r

Y

m

l 1

; (Eq. 70)

l sin y Y

m

l

þ cos y

] Y

m

l

] y

þ

m

sin y

Y

m

l

¼e

i f

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2l þ 1

2l 1

ð l þ mÞðl þ m 1 Þ

r

Y

m 1

l 1

: (Eq : 71)

Most recurrence relations can be derived from this basic set. Schuster

(1903) gives a list of recurrence relations useful in ionospheric

dynamo theory. Chapman and Bartels (1940) also derive some recur-

rence relations.

Transform ation of spheri cal harmoni cs

On using the spinor forms of derivatives (see Rotations; Eq. (45))

]

] x

¼ l

2

1

;

1

ffiffiffi

2

p

]

] z

¼ l

1

l

2

;

] f

]

¼ l

2

2

;

it follows that solid spherical harmonics can also be written using

spinors, in the more symmetric form

1

r

l þ 1

Y

m

l

ð y; fÞ¼ð1Þ

l m

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2 l þ 1

ðl mÞ!ð l þ m Þ!

s

l

l m

1

l

l þm

2

1

r

:

(Eq. 72)

The transforma tion law for spherical harmonics under rotation of the

reference frame follows from Eq. (72), using the transformation law

(see Rotations; (190))

L

1

¼ u l

1

þ vl

2

;

L

2

¼vl

1

þul

2

: (Eq : 73)

where the Cayley-Klein parameters u and v are given in terms of Euler

angles ð a ; b ; gÞ ,by

u ¼ cos

1

2

b e

i ðg þa Þ=2

;

v ¼ sin

1

2

b e

ið g aÞ

=

2

: (Eq : 74)

If a point P has spherical polar coordinates, colatitude and east longi-

tude ð y; fÞ , and if after a rotation through Euler angles ða ; b ; g Þ the

coordinates are ð Y ; FÞ , then from Eq. (72)

1

r

l þ 1

Y

m

l

ð Y ; FÞ¼ð1Þ

l m

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2 l þ 1

ðl mÞ!ð l þ m Þ!

s

L

l m

1

L

l þ m

2

1

r

:

(Eq. 75)

From the transformation formula for spinors Eq. (73), it follows that

L

l m

1

L

l þ m

2

¼ðu l

1

þ v l

2

Þ

l m

ð

vl

1

þ

ul

2

Þ

l þ m

(Eq. 76)

and after expanding by the binomial theorem

L

l m

1

L

l þ m

2

¼

X

l þ m

j¼ 0

X

l m

k ¼ 0

ð l mÞ!ð l þ m Þ!

ð l m k Þ!k !ð l þ m j Þ! j !

u

k

u

l þm j

v

l m k

v

2l j k

: (Eq. 77)

Replace the summing index k by M, where k ¼ l M j , and with

the substitutions

u ¼ðcos

1

2

b Þe

iðg þ aÞ

=

2

; v ¼ðsin

1

2

b Þe

iðg aÞ

=

2;

(Eq. 78)

we find that

L

l m

1

L

l þ m

2

¼

X

M

X

j

ð1 Þ

j

ðM m þ j Þ!ðl M jÞ!ð l þ m j Þ! j !

ðcos

1

2

b Þ

2 l M þm 2j

ðsin

1

2

b Þ

M mþ 2j

e

ið M aþ mgÞ

l

l M

1

l

l þ M

2

(Eq. 79)

The range of summing indices M and j, is such that none of the

factorial expressions or powers of trigonometrical functions become

negative.

Rot ation mat rix elemen ts

It follows from Eq. (79) that

ð1 Þ

l m

L

l m

1

L

l þ m

2

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð l m Þ!ðl þ mÞ!

p

¼

X

l

M ¼ l

D

l

Mm

ð a ; b ; gÞ

ð 1 Þ

l M

l

l M

1

l

l þm

2

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð L mÞ!ð L þ mÞ!

p

"#

;

where the functions D

l

Mm

ð a; b; gÞ are called “rotation matrix elements ”

and are written

D

l

Mm

ð a; b; gÞ¼ d

l

Mm

ð bÞ e

ið M a þm gÞ

; (Eq. 80)

and the purely real function d

l

Mm

ðb Þ is

d

l

Mm

ðb Þ¼ð1 Þ

M m

X

j

ð 1 Þ

j

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð l M Þ!ðl þ M Þ!ð l mÞ!ðl þ m Þ!

p

ðM m þjÞ!ðl M jÞ!ðl þm jÞ! j !

ðcos

1

2

bÞ

2lM þm2j

ðsin

1

2

bÞ

Mmþ2j

: (Eq. 81)

See Table H2 for a list of these functions. The form often given for

the functions d

l

Mm

ðbÞ is obtained with the substitution j ¼ m M þ t,

when

d

l

Mm

ðbÞ¼

X

t

ð1Þ

t

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ðl MÞ!ðl þ M Þ!ðl mÞ!ðl þ mÞ!

p

ðm M þ tÞ!ðl þ M tÞ!ðl m tÞ!t!

ðcos

1

2

bÞ

2lmþM 2t

ðsin

1

2

bÞ

mMþ2t

;

¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ðl MÞ!ðl þ MÞ!

ðl mÞ!ðl þ mÞ!

s

X

t

ð1Þ

t

l þ m

l þ M t

l m

t

ðcos

1

2

bÞ

2lmþM 2t

ðsin

1

2

bÞ

mMþ2t

; (Eq. 82)

HARMONICS, SPHERICAL 383

The transformation law for spherical harmonics is therefore

Y

m

l

ð Y ; F Þ¼

X

l

M ¼l

D

l

Mm

ð a ; b; gÞ Y

M

l

ð y ; f Þ: (Eq. 83)

Equation (82) is valid for half-odd integer values of the parameters l,

M, and m. In particular,

D

1

2

1

2

;

1

2

ða ; b ; gÞ¼ cos

1

2

b e

i ðg þaÞ

=

2

¼ u ;

D

1

2

1

2

;

1

2

ða ; b ; gÞ¼ sin

1

2

b e

i ðg a Þ=2

¼ v : (Eq : 84)

The transformation law for spinors, Eq. (73), becomes

L

1

L

2

¼

D

1

2

1

2

;

1

2

ða ; b ; g Þ D

1

2

1

2

;

1

2

ða ; b ; g Þ

D

1

2

1

2

;

1

2

ð a; b; g Þ D

1

2

1

2

;

1

2

ð a; b; gÞ

0

B

B

B

@

1

C

C

C

A

l

1

l

2

:

(Eq. 85)

The transformation law for surface spherical harmonics of degree one, is

Y

1

1

ð Y ; F Þ

Y

0

1

ð Y ; F Þ

Y

1

1

ðY ; FÞ

0

B

@

1

C

A

¼

cos

2

1

2

b e

iða þg Þ

ffiffiffi

2

p

sin

1

2

b cos

1

2

b e

ig

sin

2

1

2

b e

i ða þg Þ

ffiffiffi

2

p

sin

1

2

b cos

1

2

b e

ia

cos b

ffiffiffi

2

p

sin

1

2

b cos

1

2

be

i a

sin

2

1

2

b e

i ða g Þ

ffiffiffi

2

p

sin

1

2

b cos

1

2

b e

ig

cos

2

1

2

be

i ðaþ g Þ

0

B

B

B

B

B

@

1

C

C

C

C

C

A

Y

1

1

ð y ; f Þ

Y

0

1

ð y ; f Þ

Y

1

1

ðy ; f Þ

0

B

@

1

C

A

(Eq. 86)

Clo sure

When a rotation through Euler angles ða

1

; b

1

; g

1

Þ is followed by a sec-

ond rotation through Euler angles ð a

2

; b

2

; a

2

Þ, then

Y

m

0

l

ðY ; FÞ¼

X

l

M ¼l

D

l

Mm

0

ða

1

; b

1

; g

1

Þ Y

M

l

ðy ; f Þ;

Y

M

l

ð Y

0

; F

0

Þ¼

X

l

m

0

¼l

D

l

m

0

m

ða

2

; b

2

; g

2

Þ Y

m

0

l

ð Y ; F Þ;

and therefo re,

Y

m

l

ðY

0

; F

0

Þ¼

X

l

M ¼ l

X

l

m

0

¼ l

D

l

Mm

0

ða

1

; b

1

; g

1

Þ D

l

m

0

m

ð a

2

; b

2

; g

2

Þ

"#

Y

M

l

ð y; f Þ:

However, this is equivalent to a rotation through Euler angles ða ; b ; gÞ

where

Y

m

l

ðY

0

; F

0

Þ¼

X

l

M ¼l

D

l

Mm

ða ; b; g Þ Y

M

l

ðy ; fÞ;

from which it follows that

D

l

Mm

ð a; b; gÞ¼

X

l

m

0

¼l

D

l

Mm

0

ða

1

; b

1

; g

1

Þ D

l

m

0

m

ð a

2

; b

2

; g

2

Þ: (Eq. 87)

Equation (87) is an important result, with special cases giving the sum

rule, the addition theorems of trigonometry, and formulae of spherical

trigonometry, including the analogies of Napier and Delambre, as well

as the various haversine formulae. For example, in the special case that

a

1

¼ a

2

¼ a

3

¼ 0 and g

1

¼ g

2

¼ g

3

¼ 0 ; then b

3

¼ b

1

þ b

2

; and

d

l

Mm

ð b

1

þ b

2

Þ¼

X

l

m

0

¼l

d

l

Mm

0

ð b

1

Þ d

l

m

0

m

ðb

2

Þ; (Eq. 88)

which is a generalization of all of the sum formulae of trigonometry.

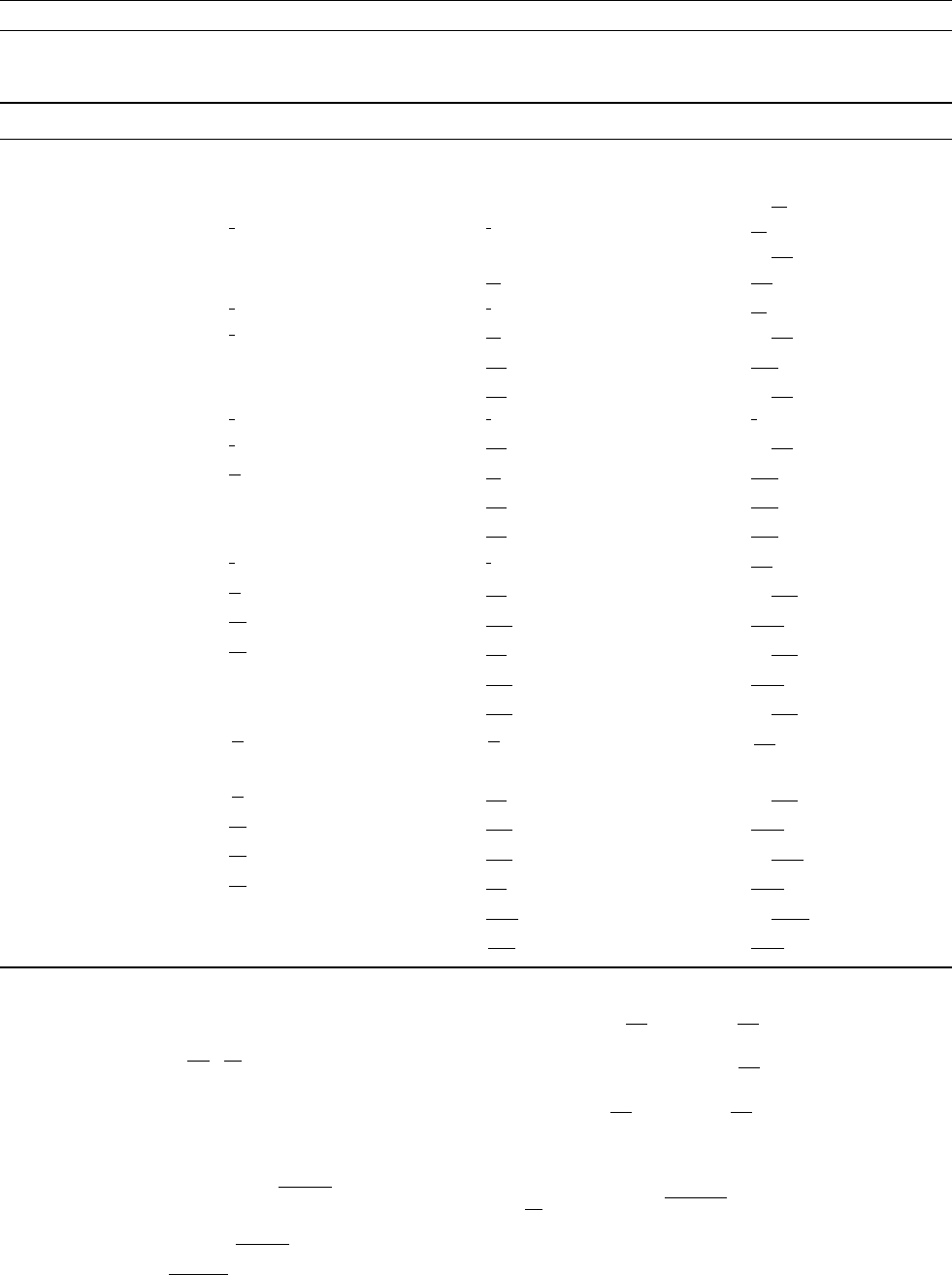

Table H2 List of rotation matrix elements to degree and order 3. Symmetry properties are required to complete the ð2 l þ 1Þð2 l þ 1Þ

table of rotation matrix elements for degree l

lMm Rotation matrix element d

l

M;m

ðbÞ lMm Rotation matrix element d

l

M;m

ðbÞ

00 0 1 31 –1

1

4

sin

2

b

2

ð15 cos

2

b þ 10 cos b 1Þ

1 0 0 cos b 31 0

ffiffi

3

p

2

cos

b

2

sin

b

2

ð1 5 cos

2

bÞ

11 –1 sin

2

b

2

31 1

1

4

cos

2

b

2

ð15 cos

2

b 10 cos b 1Þ

11 0

ffiffiffi

2

p

cos

b

2

sin

b

2

32 –2 sin

4

b

2

ð3 cos b þ 2Þ

1 1 1 cos

2

b

2

32 –1

ffiffiffiffi

10

p

2

cos

b

2

sin

3

b

2

ð1 þ 3 cos bÞ

20 0

1

2

ð3 cos

2

b 1Þ 32 0

ffiffiffiffiffi

30

p

cos

2

b

2

sin

2

b

2

cos b

21 –1 sin

2

b

2

ð2 cos b þ 1Þ 32 1

ffiffiffiffi

10

p

2

cos

3

b

2

sin

b

2

ð1 3 cos bÞ

21 0

ffiffiffi

6

p

cos

b

2

sin

b

2

cos b 3 2 2 cos

4

b

2

ð3 cos b 2Þ

2 1 1 cos

2

b

2

ð2 cos b 1Þ 33 –3 sin

6

b

2

22 –2 sin

4

b

2

33 –2

ffiffiffi

6

p

cos

b

2

sin

5

b

2

22 –1 2 cos

b

2

sin

3

b

2

33 –1

ffiffiffiffiffi

15

p

cos

2

b

2

sin

4

b

2

22 0

ffiffiffi

6

p

cos

2

b

2

sin

2

b

2

33 0 2

ffiffiffi

5

p

cos

3

b

2

sin

3

b

2

22 1 2 cos

3

b

2

sin

b

2

33 1

ffiffiffiffiffi

15

p

cos

4

b

2

sin

2

b

2

2 2 2 cos

4

b

2

33 2

ffiffiffi

6

p

cos

5

b

2

sin

b

2

30 0

1

2

ð5 cos

3

b 3 cos bÞ 3 3 3 cos

6

b

2

384 HARMONICS, SPHERICAL

Rodrigue s formul a

The rotation matrix elements D

l

Mm

ð bÞ have two types of orthogonality.

Firstly, they are orthogonal under integration over the range of the

Euler angles, 0 a < 2 p ; 0 b p , and 0 g < 2 p , and secondly,

for a fixed value of l, regarded as a ð2 l þ 1Þð2 l þ 1 Þ matrix array,

they have matrix orthogonality properties. These properties are most

easily derived using the Rodrigues formula, substituting z ¼ cos b,

when

d

l

Mm

ð zÞ¼

ð 1 Þ

l þM

2

l

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð l M Þ!

ð l þ mÞ!ð l m Þ!ðl þ M Þ!

s

ð1 zÞ

ðM mÞ=2

ð 1 þ z Þ

ð M þmÞ=2

d

d z

l þ M

½ð 1 zÞ

l þ m

ð1 þ zÞ

l m

: (Eq : 89)

The “ symmetry ” , d

l

M ;m

ðb Þ¼ d

l

m; M

ðb Þ, indicates that there are two

other equivalent formulae (Schendel, 1877).

Equation (89), in the case m ¼ 0, using Eq. (43), gives

d

l

M ;0

ð zÞ¼

ð 1 Þ

M

2

l

l !

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð l M Þ!

ð l þ M Þ!

s

ð1 z

2

Þ

M =2

d

d z

l þM

ð z

2

1 Þ

l

;

¼ð1 Þ

M

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð l M Þ!

ð l þ M Þ!

s

P

l ; M

ð zÞ;

¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ðl þ M Þ!

ðl M Þ!

s

P

l ;M

ð zÞ: (Eq. 90)

A full description of the properties of the rotation matrix elements,

including contour integral formulae is given in Vilenkin (1968).

Ortho gonality

The D-functions form unitary matrices, with orthonormal rows and

columns for each fixed degree l. They also have orthogonality proper-

ties under integration over all three Eulerian angles. The derivation

makes use of a second equivalent form for d

l

Mm

ð zÞ, namely

d

l

Mm

ð zÞ¼

ð 1 Þ

l m

2

l

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð L þ M Þ!

ðl þ mÞ!ð l m Þ!ðL M Þ!

s

ð1 zÞ

ð M þmÞ

=

2

ð 1 þ z Þ

ð M mÞ

=

2

d

d z

l M

ð 1 z Þ

l m

ð 1 þ z Þ

l þ m

hi

: (Eq : 91)

The required property is that

1

8 p

2

Z

2 p

0

Z

p

0

Z

2 p

0

D

l

Mm

ð a ; b ; gÞD

l

M

0

m

0

ð a; b; gÞ sin bd a d bd g

¼

1

2 l þ 1

d

l

0

l

d

M

0

M

d

m

0

m

: (Eq. 92)

Specia l values

At the particular values 0 ; p ; 2 p of b , the rotation matrix elements are

d

l

M ;m

ð 0Þ¼d

m

M

;

d

l

M ;m

ð pÞ¼ð1Þ

l þM

d

m

M

¼ð1Þ

l m

d

m

M

;

d

l

M ;m

ð 2p Þ¼ð1 Þ

2l

d

m

M

; (Eq : 93)

with symmetries for general values of b

d

l

M ; m

ðb Þ¼d

l

m; M

ð bÞ;

d

l

m ;M

ðb Þ¼ð1 Þ

m M

d

l

m;M

ðb Þ; (Eq: 94)

and

d

l

M ; m

ð b Þ¼ð1 Þ

m M

d

l

M ; m

ðb Þ¼d

l

m; M

bðÞ;

d

l

M ; m

ð p þ b Þ¼ð1 Þ

l m

d

l

M ; m

ðb Þ;

d

l

M ; m

ð p b Þ¼ð1 Þ

l M

d

b

M ; m

ðb Þ¼ð1 Þ

l þ m

d

l

M ;m

ð bÞ:

(Eq. 95)

The sum rule

An important special case of Eq. (89) is that for which m ¼ 0 ; when,

from Eq. (75) defining Y

m

l

ð y ; f Þ, and with m ¼ cos b , we obtain

D

l

M ;0

ð a ; b ; gÞ¼ d

l

M ;0

ðb Þ e

iM a

;

¼ð1Þ

M

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ð l M Þ!

ð l þ M Þ!

s

P

l ; M

ð m Þe

iM a

;

¼

1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

2 l þ 1

p

Y

M

l

ðb ; a Þ: (Eq: 96)

Therefore, in the special case m ¼ 0, the transformation formula (83)

becomes

Y

0

l

ðY ; FÞ¼

X

l

M ¼l

D

l

M 0

ða ; b ; g Þ Y

M

l

ðy ; f Þ: (Eq. 97)

From Eqs. (48) and (96), Eq. (97) becomes

P

l

ð cos Y Þ¼

1

2 l þ 1

X

l

M ¼l

Y

M

l

ð b; aÞ Y

M

l

ð y ; fÞ: (Eq. 98)

and the sum rule in the form Eq. (98) becomes

P

l

ð cos Y Þ¼

X

l

M ¼l

ðl M Þ!

ðl þ M Þ!

P

l ;M

ð cos b ÞP

l ;M

ð cos y Þe

iM ðf aÞ

:

(Eq. 99)

In terms of Schmidt normalized functions, the sum rule takes the well-

known form,

P

l

ð cos Y Þ¼

X

l

M ¼ 0

P

M

l

ðcos bÞ P

M

l

ðcos y Þ cos mð f a Þ: (Eq. 100)

The case l ¼ 1 of Eq. (100) is the cosine rule of spherical trigonometry,

cos Y ¼ cos b cos y þ sin b sin y cos ðf aÞ; (Eq. 101)

and the case l ¼ 2, is the basic rule in the theory of tides, with the

longitudinal terms showing the dependence on M ¼ 0 long-period

terms, M ¼ 1 lunar diurnal terms and M ¼ 2 lunar semidiurnal terms,

P

2

ð cos y Þ¼P

2

ð cos b Þ P

2

ðcos y Þþ P

1

2

ð cos b ÞP

1

2

ðcos y Þ cos ðf a Þ

þ P

2

2

ðcos bÞP

2

2

ðcos yÞcos 2ðf aÞ: (Eq. 102)

HARMONICS, SPHERICAL 385