Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ARGOSYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

109

long run in the comics. He came upon the scene with the full requisite

of essential props—two sympathetic but perplexed parents, a jalopy, a

spinster school teacher in the person of Miss Grundy, and an easily

exasperated principal named Mr. Weatherbee.

Archie Andrews pretty much ignored involvement with sex,

drugs, and delinquency as several generations of kid readers read him

and then outgrew him. His biggest appeal has probably always been

not to teenagers themselves but to the millions of preteens who accept

him as a valid representative of the adolescent world.

Archie quickly began to branch out. He and the gang from

Riverdale High were added to the lineup of Jackpot Comics soon after

his debut in Pep Comics and, in the winter of 1942, MLJ introduced

Archie Comics. An Archie radio show took to the air in 1943, settling

into a Saturday morning slot on NBC. The newspaper strip was

started in 1946, first syndicated by McClure and then King Features.

Bob Montana, returning from the service, drew the strip. In his

absence, several other cartoonists had turned out the increasing

amount of Archie Comics material. Among them were Harry Sahle,

Bill Vigoda, and Al Fagaly.

Archie reached television in the late 1960s as an animated

cartoon character. The first show was called simply The Archie Show,

and that was followed by such variations as Archie’s Funhouse and

Archie’s TV Funnies. Later attempts at a live action version of life in

Riverdale did not prove successful.

Over the years there have been several dozen different comic

book titles devoted exclusively to Archie and his gang. These include

Archie’s Mad House, Archie’s Girls, Betty and Veronica, Archie’s

Joke Book, Archie’s Pal, Jughead, Little Archie, Archie’s Christmas

Stocking, and Archie’s Double Digest. The spin-offs have included

Josie and the Pussycats and George Gladir’s Sabrina the Teenage

Witch. The chief Archie artist for many years was Dan DeCarlo and

his associates have included Tom Moore, George Frese, and

Bob Bolling.

—Ron Goulart

F

URTHER READING:

Goulart, Ron. The Comic Book Reader’s Companion. New York,

HarperCollins, 1993.

Arden, Elizabeth (1878-1966)

Elizabeth Arden symbolizes exorbitance and luxury in the multi-

billion dollar beauty industry. Born Florence Nightingale Graham,

Elizabeth Arden was a self-made woman of steely determination. She

started her business on New York’s Fifth Avenue in 1910. Respond-

ing to women’s desires for both well-being and beauty, she offered

cosmetics and treatments for home application as well as salon

pamperings at her famous Red Door salons and her Maine Chance

retreat. While Arden always respected the laboratory matrix of beauty

treatments—offering a selection of more than 300 varieties of creams

and cosmetics—Arden added essential grace notes to her products.

She replaced medicinal aromas with floral scents; she created elegant,

systematic packaging; and she opened luxurious and artistic treatment

venues, which contrasted strongly with the hospital-like austerity of

other beauty-culture clinics. In the 1960 presidential election, Jacque-

line Kennedy, responding to allegations of her extravagance, retorted

that Pat Nixon shopped at Elizabeth Arden. Arden’s business sold for

$40 million after her death in 1966.

—Richard Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Lewis, Alfred Allan, and Constance Woodworth. Miss Elizabeth

Arden: An Unretouched Portrait. New York, Coward, McCann,

and Geoghegan, 1972.

Argosy

Born as a struggling weekly for adolescents in 1882, Argosy

became the first adult magazine to rely exclusively on fiction for its

content and the first to be printed on rough, pulpwood paper. ‘‘The

story is worth more than the paper it is printed on,’’ it was once said of

Argosy, and thus was born the ‘‘pulp magazine.’’ Between 1896 and

its demise in 1979, Argosy introduced or helped inspire pulp fiction

writers such as Edgar Rice Burroughs, Jack London, Dashiell Hammett,

H. P. Lovecraft, Raymond Chandler, E. E. ‘‘Doc’’ Smith, Mickey

Spillane, Earl Stanley Gardner, Zane Grey, and Elmore Leonard, and

helped familiarize millions of readers with the detective, science

fiction, and western writing genres.

Publisher Frank Munsey arrived in New York from Maine in

1882 with $40 in his pocket. Ten months later, he helped found

Golden Argosy: Freighted with Treasures for Boys and Girls. Among

the publication’s early offerings were stories by the popular self-

success advocate Horatio Alger, Jr., but the diminutive weekly fared

poorly in the face of overwhelming competition from like juvenile

publications ‘‘of high moral tone.’’ Munsey gradually shifted the

content to more adult topics, dropping any reference to children in the

magazine in 1886 and shortening the title to Argosy in 1888. A year

later, Munsey started another publication, what would become the

highly profitable Munsey’s Magazine, and Argosy languished as a

weak imitation.

Munsey made two critical changes to rescue Argosy in 1896.

First, he switched to cheap, smelly, ragged-edged pulpwood paper,

made from and often sporting recovered wood scraps, as a way to

reduce costs. More importantly, he began publishing serial fiction

exclusively, emphasizing adventure, action, mystery, and melodrama

in exotic or dangerous locations. No love stories, no drawings or

photographs for many years, just ‘‘hard-boiled’’ language and coarse,

often gloomy settings that appealed to teenaged boys and men.

Circulation doubled, peaking at around 500,000 in 1907.

Munsey paid only slightly more for his stories than his paper.

One author recalled that $500 was the top price for serial fiction, a

fraction of what authors could make at other publications. Argosy

featured prolific serial fictionists such as Frederick Van Rensselaer

Deay, the creator of the Nick Carter detective series, William MacLeod

Raine, Albert Payson Terhune, Louis Joseph Vance, and Ellis Parker

Butler. It also published the writings of younger, undiscovered

authors such as James Branch Cabell, Charles G. D. Roberts, Susan

Glaspell, Mary Roberts Rinehart, a young Upton Sinclair, and Wil-

liam Sydney Porter (before he became known as O. Henry). Begin-

ning in 1910, Munsey began merging Argosy with a variety of weaker

competitors, a practice Munsey called ‘‘cleaning up the field.’’ The

new combination featured stories by authors such as Frank Condon,

ARIZONA HIGHWAYS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

110

Courtney Ryley, Octavus Roy Cohen, P. G. Wodehouse, Luke Short,

Van Wyck Mason, C. S. Forester, and Max Brand.

Munsey died in 1925 and ordered that his $20,000,000 magazine

empire, including Argosy, be broken up and sold, but not before

Argosy and the pulps had become a dominant force in American

popular culture, making characters such as Tarzan, Zorro, the Shad-

ow, Sam Spade, and the Phantom Detective household names. It was

purchased by William T. Dewart, but the Depression and declining

interest in pulp fiction reduced circulation to 40,000 by 1940. Re-

named New Argosy in 1942, it was temporarily banned from the mails

for ‘‘obscenity.’’ Two months later it was sold to Popular Publica-

tions, Inc. Under the supervision of Henry Steeger, Argosy abandoned

its all-fiction format and began featuring news and war articles.

Influenced by the success of newly founded men’s magazine Esquire,

the renamed Argosy—The Complete Men’s Magazine became a

‘‘slick,’’ with four-color layouts, quality fiction, and adventure,

sports, crime, science, and humor stories.

One of the most popular features was the ‘‘Court of Last

Resort.’’ Written by Erle Stanley Gardner, the creator of attorney

Perry Mason, the ‘‘court’’ presented the cases of men considered

unjustly convicted of crimes. The feature helped free, pardon, com-

mute, or parole at least 15 persons. Gardner was assisted by a

criminologist, lie detector expert, detective, prison psychologist, and

one-time FBI investigator.

The reformulated Argosy succeeded for a time. As Steeger

explained to Newsweek in 1954, ‘‘After the Second World War 15

million veterans were no longer content to accept the whimsy and

phoniness of fiction.’’ By 1953, it had a circulation of 1,250,000 and

charged over $5,000 for a single full-color page advertisement. An

Argosy editor described an average reader to Writer magazine in 1965

as ‘‘factory-bound, desk-bound, work-bound, forced by economics

and society to abandon his innate maleness and individuality to

become a cog in the corporate machine.’’

But more explicit competitors such as Playboy and Penthouse, a

shifting sense of male identity, and the prevalence of television

doomed men’s magazines such as Argosy. Popular Publications, Inc.

was dissolved in 1972 with the retirement of Henry Steeger. Argosy

and other titles were purchased by Joel Frieman and Blazing Publica-

tions, Inc., but Argosy was forced to cease publication in the face of

postal rate increases in 1979 even though it still had a circulation of

over one million. The magazine’s title resurfaced when Blazing

Publications changed its name to Argosy Communications, Inc., in

1988, and Frieman has retained copyrights and republished the

writings of authors such as Burroughs, John Carroll Daly, Gardner,

Rex Stout, and Ray Bradbury. In addition, the spirit of pulp maga-

zines like Argosy survives in the twentieth-century invention of the

comic book, with fewer words and more images but still printed on

cheap, pulpwood paper.

—Richard Digby-Junger

F

URTHER READING:

Britt, George. Forty Years—Forty Millions: The Career of Frank A.

Munsey. Port Washington, N.Y., Kennikat Press, 1935, 1972.

Cassiday, Bruce. ‘‘When Argosy Looks for Stories.’’ Writer. August

1965, 25.

Moonan, Williard. ‘‘Argosy.’’ In American Mass-Market Magazines,

edited by Alan and Barbara Nourie. Westport, Connecticut, Green-

wood Press, 1990, 29-32.

Mott, Frank L. ‘‘The Argosy.’’ A History of American Magazines.

Vol. 4. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1957, 417-23.

‘‘New Argosy Crew.’’ Newsweek. May 17, 1954, 62.

Peterson, Theodore. Magazines in the Twentieth Century. Urbana,

University of Illinois Press, 314-16.

Popular Publications, Inc. Records, c. 1910-95. Center for the Hu-

manities, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public

Library.

Server, Lee. Danger Is My Business: An Illustrated History of the

Fabulous Pulp Magazines, 1896-1953. New York, Chronicle, 1993.

Arizona Highways

Recognized by its splashy color photographs displaying Arizo-

na’s scenic wonders, Arizona Highways is the best known and most

widely circulated state-owned magazine. Founded in 1925 with a

starting circulation of 1,000 issues, Arizona Highways evolved from a

drab engineering pamphlet laced with ugly, black-and-white con-

struction advertisements to a full-color, advertisement-free, photo-

graphic essay promoting Arizona. Today, with subscribers in all fifty

states and 120 foreign countries, it is the state’s visual ambassador

and an international proselytizer of the romanticized Southwest.

Arizona Highways was one of twenty-three state-published

magazines that began with the expressed purpose of promoting the

construction of new and better roads. Arizona, like many Western

states, saw tourism as an important economic resource, but did not

have the roads necessary to take advantage of America’s dependable

new automobiles and increased leisure time. This good-roads move-

ment, which swept the country during the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries, wrested power from the railroads and helped to

democratize travel. The movement reached its peak in Arizona during

the 1930s when the federal government began funding large transpor-

tation projects as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s larger

plan to help steer the country out of the Great Depression. The New

Deal brought Arizona Highways the road construction it requested

and gave the magazine a new cause in tourism.

The Great Depression shrank advertisers’ budgets, forcing sev-

eral Arizona-based travel magazines to either cease publishing or

transform their missions. Arizona Highways, which survived because

it received a regular state subsidy, was then able to aggressively

pursue the wide-open tourist market. In 1939, the magazine’s sixth

editor, Raymond Carlson, stopped selling advertising in order to

improve the magazine’s visual appeal and avoid competition for

advertising dollars with other Arizona-based publications. Carlson,

also the magazine’s philosophical architect, edited the magazine from

1938 to 1971 and is given most of the credit for the magazine’s

success. His folksy demeanor, home-spun superlatives, and zealous

use of scenic color photography transformed the magazine into

Arizona’s postcard to the world.

The invention of Kodachrome in 1936 significantly advanced

color photography and allowed Arizona Highways to better exploit

the state’s scenic wonders. The magazine’s photographically driven

editorial content emphasizes the natural beauty of the Grand Canyon,

saguaro cactus, desert flora, and the state’s other readily recognized

symbols like the monoliths of Monument Valley, made famous by

ARMANIENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

111

many appearances in John Ford’s Western films, and the Painted

Desert. In December 1946, Arizona Highways led the nation in the use

of color photography and published the first all-color issue of a

nationally circulated consumer magazine. The all-color format be-

came standard for all issues starting in January of 1986.

In the 1940s, continuing in the tradition of Charles Lummis’s

California-based Land of Sunshine magazine and the Santa Fe Rail-

road’s turn-of-the-century advertising campaigns, Arizona Highways

began portraying a romanticized view of Arizona’s natural beauty,

climate, open land, Native American cultures, and Old West history.

The Anglo-American pioneers—cowboys, ranchers, miners, and

military figures—were portrayed as strong and fiercely independent,

Hispanics were descendants of gallant explorers and brave frontier

settlers, and Native Americans represented nobility, simplicity, and

freedom. In addition to these sympathetic and sentimental portrayals,

the magazine included the masterpieces of Western artists Ted

DeGrazia, Frederic Remington, and Lon Megargee; the writing of

Joseph Wood Krutch, Frank Waters, and Tony Hillerman; the photog-

raphy of Ansel Adams, Joseph and David Muench, and Barry

Goldwater; the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, Mary Colter, and

Paolo Soleri; and the creations of Native American artists Fred

Kabotie, Harrison Begay, and Allan Houser.

Undoubtedly the magazine’s romanticization of the Southwest

also benefited from the popularity of Western films, television and

radio network programs, and pulp fiction. In fact, the mass media’s

portrayal of the West blurred the distinction between the mythic West

and the real West in the American mind. Carlson’s agrarian philoso-

phy worked well with this blurred West because it enabled the

increasingly industrial nation to, in the words of historian Gerald

Nash, ‘‘escape from this new civilization, even while partaking of its

material and other benefits and comforts.’’ Although many readers do

visit Arizona, much of the magazine’s appeal outside the state is the

reassurance it gives readers that the West—a place of opportunity and

open land—still exists. The magazine’s cultural influence as a symbol

of this American identity was so powerful in 1965, during the

height of the Cold War, that Arizona Highways was labeled subver-

sive literature by the Soviet Union and banned there because it

was ‘‘clearly intended to conduct hostile propaganda among the

Soviet people.’’

The magazine’s circulation reached a high of over 600,000 in the

1970s, but increased subscription rates (brought on by higher labor,

postage, and paper costs) and competition from other magazines

caused the circulation to drop to nearly 400,000 by the late 1990s.

Even so, Arizona Highways has become a self-supporting operation

that no longer requires state appropriations. The magazine accom-

plished this by marketing related products—books, calendars, cards,

maps, and clothing—through bi-annual catalogs which account for

approximately 40 percent of total revenue. To remain competitive and

increase circulation, Arizona Highways maintains a delicate balance

between satisfying the editorial appetites of its current subscribers,

most of whom are over sixty, while pursuing a new generation of

younger readers through more active magazine departments and

the internet.

—Brad Melton

F

URTHER READING:

Farrell, Robert J. Arizona Highways: The People Who Shaped a

Southwestern Magazine, 1925 to 1990. Master’s thesis, Prescott,

Arizona, Prescott College, 1997.

Nash, Gerald D. ‘‘The West as Utopia and Myth, 1890-1990.’’ In

Creating the West: Historical Interpretations, 1890-1990. Albu-

querque, University of New Mexico Press, 1990, 197-257.

Pomeroy, Earl. In Search of the Golden West: The Tourist in Western

America. New York, Knopf, 1957.

Topping, Gary. ‘‘Arizona Highways: A Half-Century of Southwest-

ern Journalism.’’ Journal of the West. April 1980, 71-80.

Arledge, Roone (1931—)

Visionary producer Roone Arledge was instrumental in trans-

forming network-televised sports and news into profitable ventures.

Joining ABC Sports in 1960, he revolutionized broadcasts with his use

of instant replay and slow motion, and his humanistic production

sense brought the shows Wide World of Sports, Monday Night

Football, and announcer Howard Cosell to national consciousness. A

widely acclaimed and award winning broadcast of the terrorized 1972

Munich Olympics stirred wider ambitions, and in 1976 Arledge

became president of ABC News. He soon pioneered ratings-savvy

breakthroughs such as Nightline (1980) and the first television news

magazine, 20/20 (1978). News, however, soon moved from being

merely profitable to being profit-driven. Arledge was swallowed by

the corporate establishment. Ted Turner’s 24-hour Cable News

Network (CNN) became the standard for network news coverage, and

soon ABC was bought by Capital Cities Inc., which also owns

the successful 24-hour sports network ESPN. Arledge stepped

down in 1998.

—C. Kenyon Silvey

F

URTHER READING:

Gunther, Marc. The House That Roone Built. New York, Little,

Brown, 1994.

Powers, Ron. Supertube: The Rise Of Television Sports. New York,

Coward-McCann, 1984.

Armani, Giorgio (1934—)

Milanese fashion designer Giorgio Armani did for menswear in

1974 what Chanel did sixty years before for women’s tailoring: he

dramatically softened menswear tailoring, eliminating stuffing and

rigidity. The power of Armani styling comes from a non-traditional

masculinity of soft silhouettes and earth colors in slack elegance. His

1980s ‘‘power suit’’ (padded shoulders, dropped lapels, two buttons,

wide trousers, and low closure) and its 1990s successor (natural

shoulders, three buttons, high closure, narrow trousers, and extended

jacket length) defined prestige menswear. Armani is the first fashion

designer to focus primarily on menswear, though he has designed

womenswear since 1975. In the 1990s, Armani remained chiefly

identified with expensive suits but produced numerous lines. Armani’s

popularity in America can be traced to Richard Gere’s wardrobe in

American Gigolo (1980).

—Richard Martin

ARMED FORCES RADIO SERVICE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

112

FURTHER READING:

Martin, Richard and Harold Koda. Giorgio Armani: Images of Man.

New York, Rizzoli, 1990.

Armed Forces Radio Service

During World War II American radio made three key contribu-

tions to the war effort: news broadcasts supporting U.S. involvement

in the war, propaganda beamed at Nazi-occupied Europe, and enter-

tainment and news broadcasts to American troops around the world

via the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS). Since 1930, the

airwaves had been dominated by the entertainment-oriented program-

ming of the three major American networks, CBS, ABC, and NBC.

With the AFRS a new type of network emerged, one historian Erik

Barnouw describes as ‘‘global and without precedent.’’

In the pre-television era radio was considered such an integral

part of American life that a concentrated effort was made to continue

providing it to American troops in both the European and the Pacific

theatres. Thus the Armed Forces Radio Service was born and com-

menced broadcasting in the first years of America’s intervention in

World War II. At the beginning of 1943 AFRS had 21 outlets, but by

the end of the same year that number had grown to over 300. It was

heard in 47 countries, and every week each outlet received over 40

hours of recorded programming by plane from the United States;

additional material (such as news, sports, and special events cover-

age) was relayed by short-wave. (The very first programs for troops

had actually gone out direct by short-wave in 1942 when AFRS began

broadcasting on a limited scale). First leasing time on foreign (and

mostly government run) stations, AFRS programming moved into

high gear with the creation of its own ‘‘American expeditionary

stations,’’ the first set-up in Casablanca in March of 1943, with

stations in Oran, Tunis, Sicily, and Naples soon following. By 1945

over 800 outlets were getting the weekly shipments of AFRS programs.

The nerve center of Armed Forces Radio was at 6011 Santa

Monica Boulevard in Los Angeles. Its uniformed staff included Army

and Navy personnel as well as civilians. Its commandant, Colonel

Thomas H. A. Lewis, had been vice-president of a Hollywood

advertising agency, and was also married to actress Loretta Young, a

combination which assured AFRS access to major Hollywood talent.

Also on the staff were Sergeants Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee,

who would later co-write Auntie Mame, Inherit the Wind, and other

Broadway successes.

Ultimately the AFRS produced forty-three programs (14 hours)

itself, and aired another thirty-six hours of U.S. network radio shows

with all commercials deleted. The exorcising of commercial advertis-

ing was a particular AFRS innovation. Historian Susan Smulyan

writes in Selling Radio: ‘‘The radio industry had worked since the

1920s to make broadcast advertising seem natural and reassuringly

’American,’ but the stark contrast between wartime realities and radio

merchandising appeals revealed that advertising was neither wholly

accepted yet nor considered particularly patriotic.’’ While dependent

on the major networks for its most popular programs, the AFRS

nonetheless still deleted all commercial references and advertising

from its broadcasts. Programs such as the ‘‘Camel Caravan’’ became

‘‘Comedy Caravan,’’ and the ‘‘Chase and Sanborn Hour’’ became

simply ‘‘Charlie McCarthy.’’

A technical innovation pioneered by the AFRS was pre-recorded

programming. During its early history radio had prided itself on its

live broadcasts and shied away from developing recorded shows. But

the ability to pre-record had obvious advantages, among them the

capacity to select the best performances and ‘‘takes,’’ and to delete

controversial and time-sensitive material. Recorded shows were also

cheaper to produce and gave everyone involved a flexibility and

control impossible in live broadcasting.

Because recording tape had not yet been developed, the process

involved the manipulation of a series of vinyl and glass discs similar

to very large 78 rpm records. The final vinylite discs (which were the

copies of the shows then shipped around the world) were pressed from

a master disc which in turn had been edited from two duplicate glass

disc copies of shows recorded off of live network radio. As Barnouw

comments: ‘‘The process involved new techniques’’ requiring con-

siderable skill on the part of the engineer/editor since it necessitated

‘‘dropping a playing needle into the right spot on the right groove at

the right moment. Editing-on-disc, scarcely tried before the war,

became a highly developed specialty at AFRS.’’

The AFRS show ‘‘Command Performance’’ was the first to be

pre-recorded, and it proved that the technology existed to edit

programs and re-broadcast them from disc copies. Smulyan speculat-

ed that it may have been Bing Crosby’s experience on ‘‘Command

Performance’’ that motivated him to demand a transcription clause in

his 1946 contact with ABC, enabling him to record his shows in Los

Angeles and ship them to ABC in New York for later broadcasting. In

the late 1940s and early 1950s the phrase ‘‘Brought to you by

transcription’’ became a familiar tag line at the conclusion of many

network radio shows, the by-then standard procedure having been

developed and perfected by AFRS. To this day some of the large and

unwieldy 16-inch vinylite transcription discs from the World War II

Armed Forces Radio Service occasionally turn up in the flea markets

of southern California.

Today called Armed Forces Radio and Television Service, the

AFRS continued to air pre-recorded radio shows in years following

World War II. But by the early 1960s conventional radio had changed

with the times, and the AFRS changed as well, both now emphasing

recorded popular music of the day aired by disc-jockey personalities.

The story of one of the more off-beat army DJs, Adrian Cronauer, and

his controversial AFRS programming in Southeast Asia during the

Vietnam conflict is portrayed in the 1987 film Good Morning Vietnam.

—Ross Care

F

URTHER READING:

Barnouw, Erik. The Golden Web: A History of Broadcasting in

the United States, 1933-1953. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1968.

Smulyan, Susan. Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American

Broadcasting, 1920-1934. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Insti-

tution Press, 1994.

Armory Show

In 1913, the International Exhibition of Modern Art of 1913,

popularly known as the Armory Show, brought modern art to Ameri-

ca. The most highly publicized American cultural event of all time,

ARMSTRONGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

113

the exhibition changed the face of art in the United States. As the

media rained scorn, derision, fear, praise, hope, and simple curiosity

on the Armory Show, the American public looked on modernism for

the first time and went home to think about what they had seen.

America would never be the same.

In 1911, sixteen young New York artists who had studied in

Europe formed the Association of American Painters and Sculptors

(AAPS). Their goal was to challenge the stranglehold of such

mainstream art organizations as the National Academy of Design, a

conservative group who held the first and last word on American art

and American taste. Having been exposed to the avant-garde art being

produced in Europe by the Impressionists, the Post-Impressionists,

the Fauves, the Expressionists, the Cubists, and the Futurists, the

members of the AAPS were fed up with the stodginess of the

American art world. They hoped to foment artistic revolution, and

their means of accomplishing this was to show the New York art

world what modern art was all about.

To this end, they conceived the idea of putting on an exhibit of

modern art and decided to rent out the 69th Regimental Headquarters

of the New York National Guard, an armory built in case of worker

unrest. They brought in some 1,300 pieces of art, arranged chrono-

logically, beginning with a miniature by Goya, two small drawings by

Ingres, and a Delacroix. But these were sedate compared to the

Cézannes, Van Goghs, Picassos, Matisses, and Duchamps, which

would spark public outcry when the show opened.

Indeed, the show succeeded beyond the wildest dreams of its

organizers. As Robert Hughes has written in American Visions: The

Epic History of Art in America, ‘‘No single exhibition before or since

has had such a traumatic, stimulating, and disorienting effect on

American art and its public. It shook the bag, reshuffled the deck, and

changed the visual culture in ways that its American organizers could

not have been expected to predict.’’

When the Armory Show opened on February 17, 1913, four

thousand people lined up to get in. There was a media frenzy in which

the exhibit was both decried as ‘‘the harbinger of universal anarchy’’

as well as praised for turning the New York art world on its ear and

drawing record crowds for a cultural event. The detractors focused

mainly on Matisse and the Cubists. Marcel Duchamps’ Nude De-

scending a Staircase drew particular umbrage. As Hughes has writ-

ten, ‘‘It became the star freak of the Armory Show—its bearded lady,

its dog-faced boy. People compared it to an explosion in a shingle

factory, an earthquake on the subway.... As a picture, Nude De-

scending a Staircase is neither poor nor great.... Its fame today is the

fossil of the huge notoriety it acquired as a puzzle picture in 1913. It is,

quite literally, famous for being famous—an icon of a now desiccated

scandal. It is lodged in history because it embodied the belief that the

new work of art, the revolutionary work of art, has to be scorned and

stoned like a prophet by the uncomprehending crowd.’’

The Armory Show shook the New York, and thus the American,

art world to its very foundation. Some saw modern art as pathological

and deranged and resolutely held out against change. But for many,

particularly young artists and collectors who had not seen anything

other than academic European art, it opened their eyes to the possibili-

ties of the modern. Many cite the Armory Show as the beginning of

the Modern Age in America. After a six-week run in New York, the

show traveled to Chicago and Boston. In total, about three hundred

thousand people bought tickets to the show, three hundred thousand

people who then slowly began to turn their sights toward Europe,

toward modernism, and toward the inevitable change that would

transform popular culture in America during the twentieth century.

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

Brown, M.W. The Story of the Armory Show. New York, The

Hirshhorn Foundation, 1963.

Hughes, Robert. American Visions: The Epic History of Art in

America. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

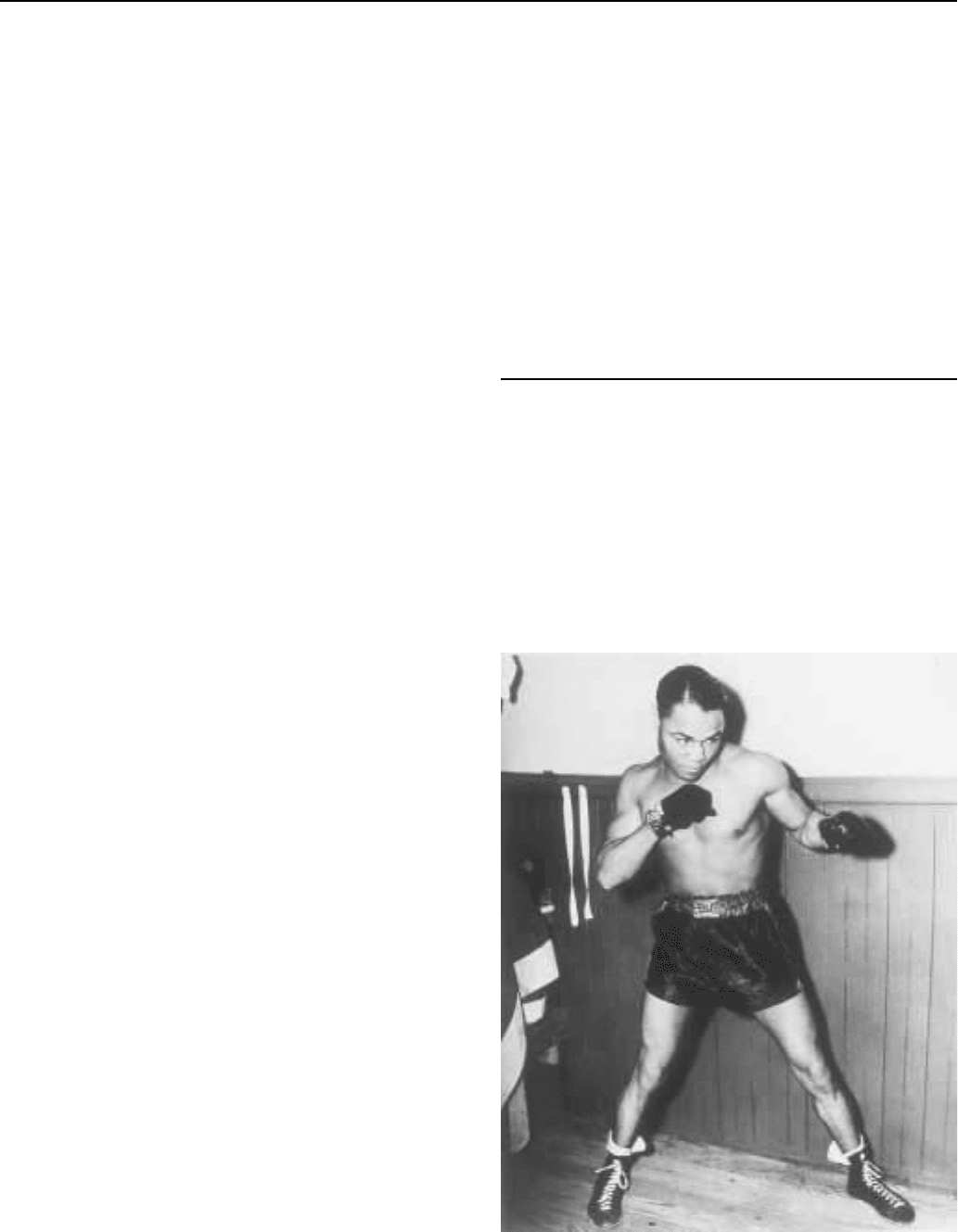

Armstrong, Henry (1912-1988)

One of the best boxers in the history of the ring, Henry Arm-

strong was the first fighter to hold world titles in three weight classes

simultaneously. Born Henry Jackson in Columbus, Mississippi, Arm-

strong began fighting in 1929. Eight years later he won the world

featherweight title from Petey Sarron. A year later he won the

lightweight and welterweight titles. Also known as ‘‘Hammerin’

Hank’’ because of his many knockouts, Armstrong was considered

one of the best fighters in the world during this period. He successful-

ly defended his welterweight title 19 times (still a record) and is fourth

on the list for consecutive defenses of a title. After he retired in 1945

Henry Armstrong

ARMSTRONG ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

114

he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. His

career included 150 wins (100 KOs), 21 losses, and 9 draws.

—Lloyd Chiasson, Jr.

F

URTHER READING:

Andre, Sam, and Nat Fleischer. A Pictorial History of Boxing. New

York, Random House, 1975.

Heller, Peter. In This Corner: Former World Champions Tell Their

Stories. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1973.

Armstrong, Louis (1901-1971)

Daniel Louis Armstrong—trumpeter and singer—was one of the

most important musicians in jazz and in twentieth-century music,

achieving seemingly insurmountable odds given his humble origins.

Armstrong proved himself as the first vital jazz soloist and one of

jazz’s most creative innovators, winning worldwide appeal and

achieving commercial success. Armstrong helped to transform the

traditional New Orleans jazz style—based on collective improvisa-

tion—to jazz featuring a star solo, thereby elevating jazz to a

Louis Armstrong

sophisticated form of music. Clearly a versatile musician, he was an

active participant in a number of jazz styles, including the New

Orleans style of the 1910s, the Chicago style of the 1920s, the New

York style in the 1930s, and the jazz of the wider world in the 1950s.

Armstrong was one of the first blacks seen in feature-length films; in

total he appeared in nearly 50. In addition to a sponsored radio show,

the United States State Department and private organizations spon-

sored international tours of his music and performances, earning him

the nickname ‘‘Ambassador Satch.’’

For many years, July 4, 1900 was cited as Armstrong’s birth

date, but the discovery of his baptismal records confirm that his real

birth date was August 4, 1901. His birthplace of New Orleans was a

haven for all kinds of music, from French Opera to the blues. He grew

up in the ‘‘Back o’ Town’’ section near the red-light district, and

therefore heard and absorbed the rags, marches, and blues that were

the precursors to early jazz. Because his family was so impover-

ished—he barely had enough to eat and wore rags as a child—

Armstrong often sang on the street as a kid. His father, a laborer,

abandoned the family when he was young and his mother was, at best,

an irresponsible single parent who left the young Armstrong and his

sister in the care of relatives. In addition to singing on the streets,

Armstrong sang in a Barbershop quartet, providing an excellent

opportunity for him to train his ear.

ARMSTRONGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

115

As a teenager, Armstrong found himself in trouble for general

delinquency and had to spend more than two years at the Home for

Colored Waifs. He eventually found an outlet in the school band, first

taking up the tambourine and later the cornet under his teacher Peter

Davis. Armstrong mastered the school’s repertoire of marches and

rags, and eventually became the leader of the Home’s brass band that

frequently played for picnics and parades. Upon his release, Arm-

strong decided that he wanted to become a musician. Not owning a

horn did not deter him. He played his first job at a honky-tonk in

Storyville’s red-light district; he used a borrowed horn and performed

blues and other songs from his limited repertoire. When not playing

his regular job, Armstrong would frequent clubs and listen to various

musicians playing the blues.

Cornetist and bandleader Joe ‘‘King’’ Oliver was impressed

with Armstrong and took him under his wing. When Oliver left for

Chicago in 1918, Armstrong took his place as cornetist in the band led

by Kid Ory. In the same year, he married a prostitute, but the

relationship soon ending in divorce. He continued to work in clubs

with established bands, and on the side formed his own group. Pianist

and bandleader Fate Marable then hired Armstrong to work on the

riverboats, and the job provided him with the opportunity to improve

his musicianship. During this period, a melophone player named

David Jones taught Armstrong to read music. By 1922, he was invited

to join King Oliver as second cornetist in Chicago at the Lincoln

Gardens. The Oliver job showcased the young Armstrong’s prowess

as a virtuoso improvisor who would ‘‘swing’’ at the slightest provo-

cation. In 1924, Armstrong married pianist Lil Hardin and, upon her

insistence, moved to New York where he joined the Fletcher Hender-

son Orchestra. His solos and improvisation drew the attention of New

York musicians, but by 1925 he returned to Chicago where he joined

the Erskine Tate ‘‘symphonic jazz’’ Orchestra and, subsequently,

Carroll Dickerson’s Orchestra. He was now billed as ‘‘Louis Arm-

strong, world’s greatest trumpet player.’’ With his popularity soaring,

in 1929 Armstrong joined the hit show Hot Chocolates, where he sang

‘‘Ain’t Misbehavin’.’’ Significantly, Armstrong had become a sensa-

tion appreciated by both black and white audiences. It was a pivotal

point in his career.

Armstrong could have easily chosen to pursue a career leading a

jazz group, but instead, he opted for broadening his commercial

appeal by singing popular tunes and becoming a showman. His

decision was, perhaps, influenced by his childhood, but managers

Tommy Rockwell and Joe Glaser also played an important role in the

direction of his career. Many critics assert that Armstrong’s musical

legacy stopped in the year 1936, when, as the noted jazz critic

Leonard Feather observed: ‘‘The greater his impact on the public, the

less important were his musical settings and the less durable his

musical contributions.’’

In 1925, Armstrong began to record under the name Louis

Armstrong and His Hot Five. These recordings, which can be placed

into four categories, had a profound influence on jazz, and are

regarded as one of the most momentous recordings in the music of the

twentieth century. The first category of the Hot Five recordings are in

the New Orleans style, but Armstrong’s scatting on ‘‘Heebie Jee-

bies’’ set a precedent for the scat style of singing. The second

category was recorded with the enlargement of the quintet to include a

tuba and drums, issued under the name of Louis Armstrong and His

Hot Seven; ‘‘Potato Head Blues’’ is considered stellar in this group.

The third category consisted of the group returning to the original Hot

Five band with the extraordinary ‘‘Struttin’ with some Barbecue,’’

and the highly regarded ‘‘Hotter than that.’’ The fourth category

included Earl Hines as pianist. The recordings in this category are

considered by many critics as Armstrong’s greatest. Including gems

such as ‘‘Weather Bird,’’ ‘‘West End Blues,’’ and ‘‘Don’t Jive Me,’’

they were made in 1928 and reflect Armstrong’s break with the New

Orleans style. Hines possessed a facile technique and an inventive

mind, the result of which were improvisations where the right hand of

the piano mimicked the trumpet in octaves; the trademark gave rise to

the term ‘‘trumpet style’’ piano. Armstrong and Hines complimented

each other, feeding, inspiring, and spurring one another to create

sheer musical excellence.

Armstrong’s big band group of recordings represent him as a

bandleader, solo variety attraction, and jester. In this format, he

largely abandoned the jazz repertoire in favor of popular songs vis à

vis the blues and original compositions. A majority of the bands he

fronted, including Luis Russell and Les Hite, fell short of his

musical genius.

Armstrong signaled his return to the New Orleans style with the

All Stars in 1947. The sextet made their debut in August 1947 after his

appearance in the mediocre film New Orleans. The music was superb

and seemed to placate the critics. The All Stars featured trombonist

Jack Teagarden, clarinetist Barney Bigard, pianist Dick Cary, drum-

mer Sid Catlett, and bassist Arvell Shaw, although the group’s

personnel continually changed. This smaller group was an instant

success and became the permanent format that Armstrong guid-

ed until his death; together they recorded the highly acclaimed

Autobiography sessions.

As early as 1932 Armstrong toured Europe, playing at the

London Palladium. This was the first of many trips taken for concerts

and television appearances. The transformation from musician to

entertainer had taken full effect. ‘‘You Rascal You,’’ among other

novelty songs, were audience favorites. Ella Fitzgerald, Oscar Peterson,

and the Dukes of Dixieland were among the diverse stylists who

recorded with Armstrong.

The excruciating touring demands that began in the 1930s would

eventually take their toll on Armstrong. He had already experienced

intermittent problems with his health and shortly after playing a date

with the All Stars at the Waldorf Astoria in New York, Armstrong

suffered a heart attack. He remained in intensive care for more than a

month and returned home, where he died in his sleep on May 6, 1971.

A musical legend, Armstrong’s style was characterized by a

terminal vibrato, an exceptional ability to swing playing notes around

the beat, and an uncanny appreciation for pauses and stops which

showcased his virtuoso technique. He used dramatic devices to

capture the attention of audiences, including sliding or ripping into

notes, either ending a phrase or tune on a high note. His ebullient

personality showed through his music, and his style was dictated by a

savoir faire that was embraced by his fans throughout the world.

—Willie Collins

F

URTHER READING:

Armstrong, Louis; edited by Thomas Brothers. Louis Armstrong, In

His Own Words: Selected Writings. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1999.

———. Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. New York, Prentice-

Hall, 1954.

Berrett, Joshua, editor. The Louis Armstrong Companion: Eight

Decades of Commentary. New York, Schirmer Books, 1999.

Boujut, Michel. Louis Armstrong. New York, Rizzoli, 1998.

ARMY-McCARTHY HEARINGS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

116

Chilton, John, and Max Jones. Louis: The Louis Armstrong Story

1900-1971. Boston, Little, Brown and Company. 1971.

Giddins, Gary. Satchmo. New York, Anchor Books, 1992.

Army-McCarthy Hearings

In the 1950s Joseph McCarthy, a Republican senator from

Appleton, Wisconsin, waged a years-long battle against subversive

conduct in the United States and against the Communists whom he

believed to be hiding in all walks of American life—particularly in

government, Hollywood, and academia. McCarthy’s unsubstantiated

claims led to upheaval, the destruction of careers, and to a concentrat-

ed attack on the freedoms guaranteed to Americans in the First

Amendment of the Constitution. Despite attempts by conservative

scholars to reinstate McCarthy’s tarnished reputation, no one has

proved that he ever identified an actual subversive. Nowhere were his

bullying tactics more obvious than when he accused the United States

Army of harboring Communists. The hearings on these activities and

McCarthy’s belligerent behavior were broadcast on network televi-

sion in 1957.

Specifically, McCarthy targeted an army dentist who was in the

process of being voluntarily discharged due to the illness of his wife

and daughter. Irving Peress, who had been drafted under the McCar-

thy-supported Doctors and Dentists Draft Act, had checked ‘‘Federal

Constitutional Privilege’’ instead of ‘‘Yes’’ or ‘‘No’’ when he signed

the required Loyalty Oath. This was all that McCarthy needed to

launch an attack against the dentist and the United States Army.

In a broader sense, McCarthy was responding to information in a

letter that was later proved to be false. The letter named 34 scientists,

engineers, and technicians at Fort Monmouth as subversives. In his

history of the hearings, John G. Adams, a major player in the debacle

and lawyer for the army, maintains that McCarthy was mad at the

army for refusing to give special treatment to David Schine, a wealthy

member of McCarthy’s staff who had been drafted. At any rate, 26 of

the 34 accused subversives were cleared by a loyalty board, and the

other eight convictions were ultimately overturned by the courts. The

Loyalty Board, made up of high-ranking officers and well-respected

civilians, quickly became the target of McCarthy’s ire. He demanded

the right to question them. The army, determined to protect the

Board’s identity and its own reputation, refused. While President

Dwight Eisenhower had been elected on the wave of anti-Commu-

nism fueled by McCarthy, the two were poles apart ideologically.

When McCarthy went after the army, Eisenhower refused to remain

on the sidelines.

Backed by the White House, the army belatedly stood up to

McCarthy and refused to offer their officers as lambs to McCarthy’s

slaughter. Robert T. Stevens, Secretary of the Army, issued a press

release stating that he had advised Brigadier General Ralph W.

Zwicker of Camp Kilmer not to appear before the senator’s commit-

tee. As part of the attack on the army, McCarthy, with his typical

outrageousness, had accused Zwicker of being unfit to wear the army

uniform and of having the brains of a five year-old, and he demanded

his immediate dismissal. McCarthy ignored the fact that it was

Zwicker who reported the allegedly subversive Peress. When a

transcript from the closed hearings was leaked to the press and

published by the New York Times, McCarthy’s supporters—including

several prestigious newspapers—began to back away.

Eisenhower used the diary of army lawyer John G. Adams to

illuminate the extent of McCarthy’s out-of-control behavior, includ-

ing the fact that Roy Cohn, McCarthy’s committee counsel, was being

subsidized by the wealthy Schine. Reporter Joseph Alsop, who had

secretly seen the diary in its entirety before it was commandeered by

the White House, joined his brother in releasing additional informa-

tion indicating that McCarthy was very much under the influence of

Cohn, who had promised to end the attack on the army if Schine were

given the requested special treatment. McCarthy then counterat-

tacked, providing additional information to challenge the integrity of

the army.

McCarthy’s nemesis proved to be Joseph Nye, Chief Counsel for

the army. With admirable skill, Nye led McCarthy into exhibiting his

true arrogance and vindictiveness. Beforehand, McCarthy had agreed

not to attack Fred Fisher, a young lawyer who had withdrawn from

working with Nye on the case because he had once belonged to a

Communist-front group known as the ‘‘Lawyer’s Guild.’’ When

McCarthy reneged, Nye counterattacked: ‘‘Little did I dream you

could be so reckless and so cruel as to do an injury to that lad . . . Let

us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You have done enough.

Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense

of decency?’’

It was a fitting epitaph for the horror that was the political career

of Senator Joseph McCarthy. His lack of decency was evident, and he

was subsequently censured by the United States Senate. In 1998,

Godfrey Sperling, a reporter who dogged McCarthy’s footsteps

during the 1950s, responded to the newly developed efforts to

reinstate McCarthy’s reputation: ‘‘The Joe McCarthy I covered was a

man who, at best, had overreached his capacity, he simply wasn’t all

that bright. At worst, he was a shifty politician who didn’t mind using

lies or guesses to try to destroy others.’’ While the individuals

attacked by McCarthy were often weak, the institution of the United

States Army was not—it survived his attacks. Yet the Army-McCar-

thy hearings demonstrated the dangers inherent in politicians with too

much power, too few controls, and the ability to manipulate a

gullible public.

—Elizabeth Purdy

F

URTHER READING:

Adams, John G. Without Precedent: The Story of the Death of

McCarthyism. New York and London, W.W. Norton and Compa-

ny, 1983.

Merry, Robert W. ‘‘McCarthyism’s Self-Destruction.’’ Congression-

al Quarterly. Vol. 54, No. 11, 1995, 923-26.

Sperling, Godfrey. ‘‘It’s Wrong to Rehabilitate McCarthy—Even if

He Was Right.’’ Christian Science Monitor. November 17, 1998, 9.

Wannal, Ray. ‘‘The Red Road to McCarthyism.’’ Human Events.

Vol. 52, No. 5, 1996, 5-7.

Arnaz, Desi (1917-1986)

A famed Afro-Cuban music band leader and minor movie star,

Desi Arnaz rose from nightclub performer to television magnate

during the golden years of black-and-white television. Born Desiderio

Alberto Arnaz y de Acha III on March 2, 1917, in Santiago, Cuba, to a

ARNAZENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

117

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz.

wealthy family. Arnaz accompanied his father into political exile in

Miami when the family’s fortune was destroyed and his father

became persona non grata under the Fulgencia Batista regime. At the

age of seventeen, Arnaz’s musical talent was discovered by renowned

band leader Xavier Cugat, and by 1937 he was leading his own band

in Miami Beach. Arnaz began to make a name for himself as a band

leader, drummer, and singer in New York City and Miami Beach

nightclubs when Afro-Cuban music was making its first and largest

impact on American popular music of the late 1930s and early 1940s.

It was in 1940 that he married the love of his life, Lucille Ball,

who would later be cast as his on-screen wife in I Love Lucy. Ball had

served as his co-star in the movie Too Many Girls, which was Arnaz’s

screen debut; the movie was the screen version of the Lorenz Hart and

Richard Rogers Broadway hit of the same name, in which Arnaz had

made his stage acting debut. His skyrocketing career was temporarily

delayed by service in the Army during World War II. When he

returned to Hollywood after his discharge from the service, Arnaz

found that his heavy accent and Hispanic looks not only limited his

opportunities but kept him type cast.

It was Arnaz’s particular genius that converted the typecasting

into an asset, and he was able to construct a television persona based

not only on a comic version of the Latin Lover, but also on his success

as a singer and rumba band leader. Mass popularity was finally

achieved when, in 1952, Arnaz became the first Hispanic star on

television with his pioneering what became the longest running

sitcom in history: I Love Lucy. Eventually lasting nine years, Arnaz

and Lucille Ball modified the Latin Lover and Dumb Blonde stereo-

types to capture the attention of television audiences, who were also

engaged by the slightly titillating undercurrent of a mixed marriage

between an Anglo and an Hispanic who played and sang Afro-Cuban

music, while banging on an African-derived conga drum and backed

up by musicians of mixed racial features. The formula of pairing a

Wasp and a minority or outcast has since been duplicated repeatedly

on television to this date through such programs as Chico and the

Man, Who’s the Boss?, and The Nanny, and others.

His business acumen had already been revealed when in 1948 he

and Ball founded Desilu Productions to consolidate their various

stage, screen, and radio activities. Under Arnaz’s direction Desilu

ARROW COLLAR MAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

118

Productions grew into a major television studio. In 1960, Arnaz and

Ball divorced; their son and daughter followed in their parents’ acting

footsteps, but never achieved the success of their parents. Included

among Desi Arnaz’s films are Too Many Girls (1940), Father Takes a

Wife (1941), The Navy Comes Through (1942), Bataan (1943),

Cuban Pete (1946), Holiday in Havana (1949), The Long Trailer

(1954), and Forever Darling (1956). I Love Lucy can still be seen in

black-and-white re-runs in many parts of the United States. In 1976,

Arnaz published his own rather picaresque and acerbic autobiogra-

phy, A Book, detailing his rise to fame and riches and proclaiming his

undying love for Lucille Ball. Arnaz died on December 2, 1986.

—Nicolás Kanellos

F

URTHER READING:

Kanellos, Nicolás. The Hispanic American Almanac. Detroit, Gale

Research, 1997.

Pérez-Firmat, Gustavo. Life on the Hyphen: The Cuban American

Way. Austin, University of Texas Press, 1993.

Tardiff, Joseph T., and L. Mpho Mabunda, editors. Dictionary of

Hispanic Biography. Detroit, Gale Research, 1996.

Arrow Collar Man

The advertising icon of the Cluett, Peabody & Company’s line of

Arrow shirts from 1905 to 1930 was the era’s symbol for the ideal

athletic, austere, confident American man. He was the somewhat

eroticized male counterpart to Charles Dana Gibson’s equally em-

blematic and elegant all-American woman. No less a cultural spokes-

man than Theodore Roosevelt considered him to be a superb portrait

of ‘‘the common man,’’ although admittedly an Anglo-Saxon version

of it that suited the times. This Arrow Collar Man was the inspiration

of J(oseph) C(hristian) Leyendecker (1874-1951), the foremost Ameri-

can magazine illustrator of the first four decades of the twentieth century.

Born in Germany but emigrating at age eight with his parents,

Leyendecker was trained at the Art Institute of Chicago and in Paris.

He worked on advertising campaigns for Kuppenheimer suits as well

as other products and did cover art for Collier’s and the Saturday

Evening Post. In that last role, he was the direct predecessor and a

major influence on a near-contemporary illustrator, Norman Rockwell,

who idolized his work.

The Arrow Man ads sold more than 400 styles of detachable shirt

collars with images of an insouciant, aquiline-nosed young man, often

depicted in vigorous stances or with the jaunty prop of a pipe.

Leyendecker’s figures were characterized by their glistening, pol-

ished appearance, indicating a healthy athletic glow. After World War

I, when soldiers learned the practicality of attached collars, Leyendecker

switched to doing ads for Arrow’s new line of shirts.

The generic Arrow Collar Man received more fan mail in the

1920s (sent to corporate headquarters) than Rudolph Valentino or any

other male film star of the era. In 1920, approximately seventeen

thousand love letters arrived a week, and there was a Broadway play

about him as well as a surfeit of popular songs and poems.

Leyendecker sometimes used future film stars such as John

Barrymore, Fredric March, Brian Donlevy, Jack Mulhall, and his

good friend Neil Hamilton as models. A perfectionist in his craft,

Leyendecker always preferred to work from live figures rather than

from photographs, as Rockwell and others sometimes did. But the

illustrator’s first, most important, and enduring muse for the Arrow

ads was Charles Beach. After a meeting in 1901, Beach became

Leyendecker’s companion, housemate, and business manager for

close to fifty years, a personal and professional relationship ended

only by Leyendecker’s death at his estate in New Rochelle, New York.

The Arrow contract, as well as those with other clothiers, ended

soon after the onset of the Great Depression. The image of the ruddy-

complexioned, sophisticated young man, however, did not soon fade

in the popular mind. A teasing ad in the Saturday Evening Post on

February 18, 1939, queried, ‘‘Whatever Became of the ‘Arrow Collar

Man’?. . . Though he passed from our advertising some years ago, he

is still very much with us.... [Today’s man dressed in an Arrow

shirt] is just as much an embodiment of smartness as that gleaming

Adonis was in his heyday.’’

Perhaps his era had passed, for the Arrow Man had reflected the

education, position, breeding, and even ennui that figured so promi-

nently in the novels of F. Scott Fitzgerald during the previous decade.

Leyendecker continued with his magazine illustrations, but a change

in the editorial board at the Saturday Evening Post in the late 1930s

resulted in his gradual fall from grace. Leyendecker’s last cover for

that publication appeared on January 2, 1943. The mantle then rested

permanently upon Norman Rockwell, who fittingly served as one of

the pallbearers at Leyendecker’s funeral fewer than ten years later.

—Frederick J. Augustyn, Jr.

F

URTHER READING:

Rockwell, Norman. Norman Rockwell: My Adventures as an Illustra-

tor. New York, Curtis Publishing, 1979.

Schau, Michael. J. C. Leyendecker. New York, Watson-Guptill

Publications, 1974.

Arthur, Bea (1923—)

With her tall, rangy frame and distinctive, husky voice, actress

Bea Arthur has never been anyone’s idea of a starlet. However, using

her dry humor and impeccable comic timing coupled with an excep-

tional comfort with her body, she has created some of the most

memorable strong female characters on television, in film, and on the

musical stage.

Arthur was born Bernice Frankel in New York City and grew up,

the daughter of department store owners, in Cambridge, Massachu-

setts. Her first attempts on the stage as a torch singer failed when, as

she said, ‘‘Audiences laughed when I sang about throwing myself in

the river because my man got away.’’ Her imposing height and deep

voice suited her better for comedy, she decided, and she honed her

skills doing sketch comedy at resorts in the Poconos. In 1954 she got

her first big break when she landed a role off-Broadway playing

opposite Lotte Lenya in The Threepenny Opera. Audiences loved her,

and throughout her career she has looked back fondly on the role that

started her successful career: ‘‘Of everything I’ve done, that was the

most meaningful. Which is like the first time I felt, I’m here, I

can do it.’’

Arthur continued to ‘‘do it,’’ wowing audiences with her come-

dic skill as well as song and dance. She originated the role of Yente

the matchmaker in Fiddler on the Roof on Broadway, and she won a