Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

AUTOMOBILEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

139

market. Ransom Olds produced the first widely popular and inexpen-

sive model, his ‘‘curved dash’’ Oldsmobile, of which he made over

12,000 between 1901 and 1904. His small, lightweight, reliable

runabout took such a hold of the public’s imagination that a composer

commemorated it in a popular song, ‘‘In My Merry Oldsmobile’’:

Come away with me, Lucille,

In my merry Oldsmobile,

Over the road of life we’ll fly,

Autobubbling you and I,

To the church we’ll swiftly steal,

And our wedding bells will peal,

You can go as far as you like with me,

In our merry Oldsmobile.

As much success as the Oldsmobile enjoyed, it took Henry Ford,

a manufacturer from Dearborn, Michigan, to seize the idea of mass

production and use it to change the face of the automobile industry.

The Ford Model T—alternately dubbed the ‘‘Tin Lizzie’’ and the

‘‘flivver’’ by an enthusiastic public—first became available in 1908.

The car coupled a simple, durable design and new manufacturing

methods, which kept it relatively inexpensive at $850. After years of

development, experimentation, and falling prices, the Ford Company

launched the world’s first fully automated assembly line in 1914.

Between 1909 and 1926, the Model T averaged nearly forty-three

percent of the automobile industry’s total output. As a result of its

assembly-line construction, the car’s price dropped steadily to a low

of $290 on the eve of its withdrawal from the market in 1927. The

company also set new standards for the industry by announcing in

1914 that it would more than double its workers’ minimum wages to

an unprecedented five dollars per day. Over the course of the Model

T’s production run, the Ford Company combined assembly-line

manufacturing, high wages, aggressive mass-marketing techniques,

and an innovative branch assembly system to make and sell over

fifteen million cars. As a result, Henry Ford became something of a

folk hero, particularly in grass-roots America, while the car so well-

suited to the poor roads of rural America became the subject of its own

popular genre of jokes and stories. In 1929, the journalist Charles

Merz called the Model T ‘‘the log cabin of the motor age.’’ It was an

apt description, for more first-time buyers bought Model T’s than any

other type, making it the car that ushered most Americans into the

automobile era.

Between 1908 and 1920, as automobiles became affordable to a

greater percentage of Americans, farmers quickly abandoned their

prejudices against the newfangled machines and embraced them as

utilitarian tools that expanded the possibilities of rural life. The

diffusion of cars among rural residents had a significant effect on farm

families, still forty percent of the United States population in 1920.

Because automobiles increased the realistic distance one could travel

in a day—and unlike horses did not get so tired after long trips that

they were unable to work the next day—cars allowed farmers to make

more frequent trips to see neighbors and visit town. In addition, rural

Americans found a number of uses for the versatile, tough machines

on farms themselves, hauling supplies, moving quickly around the

farm, and using the engine to power other farm machinery.

As car sales soared before 1920, the movement for good roads

gained momentum and became a priority for many state legislatures.

Rural roads had fallen into a bad state of neglect since the advent of

the railroads, but early ‘‘Good Roads’’ reformers nevertheless met

stiff opposition to their proposed plans for improvement. Farmers

argued that expensive road improvement programs would cost local

citizens too much in taxes, and that good roads would benefit urban

motorists much more than the rural residents footing the bill. Reform-

ers had to wage fierce political battles to overcome rural opposition,

and succeeded only after convincing state legislatures to finance

improvements entirely with state funds, completely removing road

maintenance from local control. Resistance was not limited to rural

areas, however. Even within cities, many working-class neighbor-

hoods opposed the attempts of Good Roads advocates to convert

streets into arteries for traffic, preferring instead to protect the more

traditional function of neighborhood streets as social spaces for public

gatherings and recreation. In addition, special interest groups such as

street-car monopolies and political machines fought to maintain their

control over the streets. Only after the victory of other Progressive Era

municipal reformers did road engineers succeed in bringing their

values of efficiency and expertise to city street system management.

In the 1920s, car prices dropped, designs improved, roads

became more drivable, and automobiles increasingly seemed to

provide the key to innumerable advantages of modern life. To many

people, cars embodied freedom, progress, and social status all at the

same time. Not only could car owners enjoy the exhilaration of

speeding down open roads, but they also had the power to choose

their own travel routes, departure times, and passengers. Outdoor

‘‘autocamping’’ became a popular family pastime, and an entire

tourist industry designed to feed, house, and entertain motorists

sprang up almost overnight. Even advertising adapted to a public

traveling thirty miles per hour, led by the innovative Burma Shave

campaign that spread its jingles over consecutive roadside billboards.

One set informed motorists that ‘‘IF YOU DON’T KNOW / WHOSE

SIGNS / THESE ARE / YOU CAN’T HAVE / DRIVEN VERY FAR

/ BURMA SHAVE.’’ In a variety of ways, then, automobile engines

provided much of the roar of the Roaring Twenties, and stood next to

the flapper, the flask, and the Charleston as a quintessential symbol of

the time.

As an icon of the New Era, the automobile also symbolized the

negative aspects of modern life to those who lamented the crumbling

of Victorian standards of morality, family, and propriety. Ministers

bewailed the institution of the ‘‘Sunday Drive,’’ the growing tenden-

cy of their flocks to skip church on pretty days to motor across the

countryside. Law enforcement officials and members of the press

expressed frustration over the growing number of criminals who used

getaway cars to flee from the police. Even social critics who tended to

approve of the passing of Victorian values noted that the rapid

diffusion of automobiles in the 1920s created a number of unanticipated

problems. Rather than solving traffic problems, widespread car

ownership increased the number of vehicles on the road—and lining

the curbs—which made traffic worse than ever before. Parking

problems became so acute in many cities that humorist Will Rogers

joked in 1924 that ‘‘Politics ain’t worrying this Country one tenth as

much as Parking Space.’’ Building expensive new roads to alleviate

congestion paradoxically increased it by encouraging people to use

them more frequently. Individual automobiles seemed to be a great

idea, but people increasingly began to see that too many cars could

frustrate their ability to realize the automobile’s promises of freedom,

mobility, and easy escape.

Despite these problems and a small group of naysayers, Ameri-

can popular culture adopted the automobile with alacrity. Tin Pan

Alley artists published hundreds of automobile-related songs, with

titles like ‘‘Get A Horse,’’ ‘‘Otto, You Ought to Take Me in Your

Auto,’’ and ‘‘In Our Little Love Mobile.’’ Broadway and vaudeville

AUTOMOBILE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

140

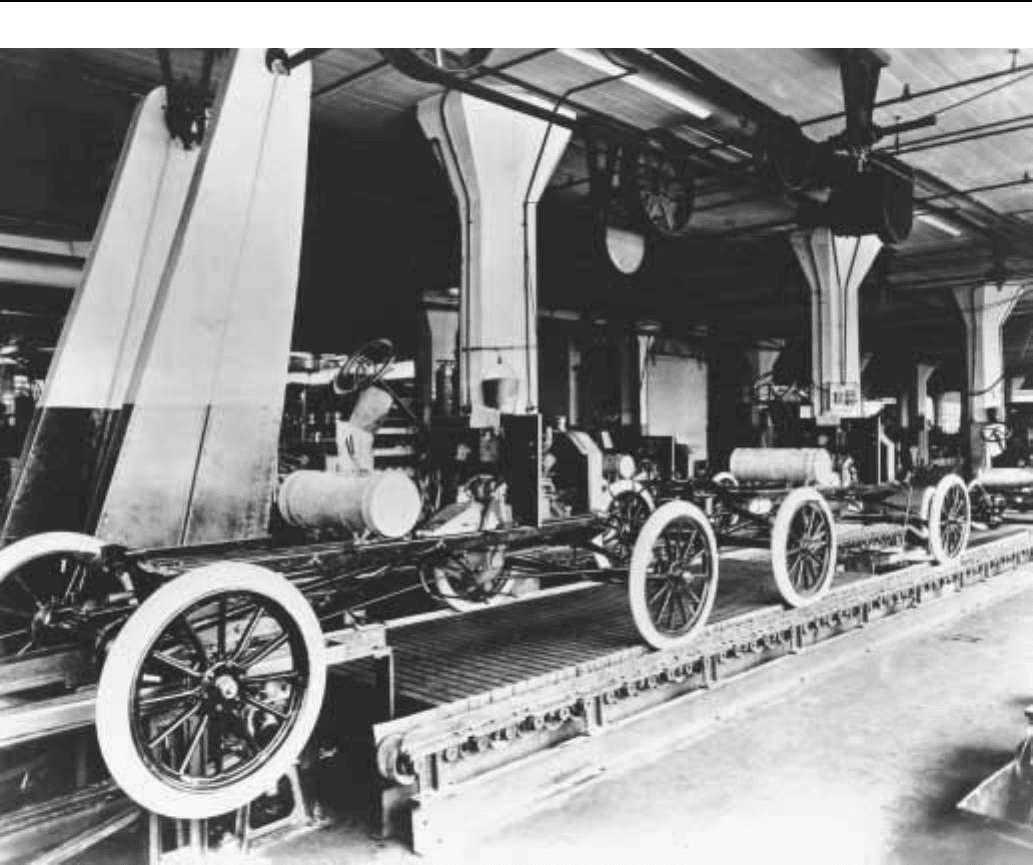

An example of the early automobile assembly line.

shows both adopted cars as comic props, a tradition the Keystone

Kops carried over into the movie industry. Gangster films in particu-

lar relied on cars for high-speed chases and shoot-outs, but even films

without automobile-centered plots used cars as symbols of social

hierarchy: Model T’s immediately signaled humble origins, while

limousines indicated wealth. In Babbitt (1922), Sinclair Lewis noted

that ‘‘a family’s motor indicated its social rank as precisely as the

grades of the peerage determined the rank of an English family,’’ and

in the eyes of Nick Carraway, the narrator of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The

Great Gatsby (1925), Gatsby’s Rolls-Royce represented the ‘‘fresh,

green breast of the new world.’’ Parents worried that teenagers used

automobiles as mobile bedrooms, a growing number of women

declared their independence by taking the wheel, and sociologists

Robert and Helen Lynd declared that automobiles had become ‘‘an

accepted essential of normal living’’ during the 1920s.

After the stock market crashed in 1929, automobiles remained

important cultural symbols. Throughout the Great Depression, cars

reminded people of the prosperity that they had lost. On the other

hand, widespread car ownership among people without homes or jobs

called attention to the country’s comparatively high standard of

living; in the United States, it seemed, poverty did not preclude

automobile ownership. Countless families traveled around the coun-

try by car in search of work, rationing money to pay for gasoline even

before buying food. Dorothea Lange’s photography and John Stein-

beck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939) immortalized these migrants,

who became for many the symbolic essence of the decade’s economic

ills. Automobiles had become such a permanent fixture in American

life when the Depression hit that even in its pit, when the automobile

industry’s production had fallen to below a quarter of its 1929 figures,

car registrations remained at over ninety percent of their 1929

number. Even before the Depression began most Americans had

thoroughly modified their lifestyles to take advantage of what auto-

mobiles had to offer, and they refused to let a weak economy deprive

them of their cars. Tellingly, steady automobile use through the 1930s

provided an uninterrupted flow of income from gasoline taxes, which

the country used to build roads at an unprecedented rate.

The thousands of miles of paved highway built during the

Depression hint at one of the most profound developments of the first

AUTOMOBILEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

141

half of the twentieth century: the extensive modification and rear-

rangement of the country’s built environment to accommodate wide-

spread automobile use. In urban areas, general car ownership under-

mined the centralizing influence of the railroads. Because businesses

could unload railroad freight into motorized trucks instead of horse-

drawn wagons, which significantly reduced their short-haul transpor-

tation costs, proximity to railroad depots became much less impor-

tant. At the same time, growing traffic problems in urban cores along

with a more mobile buying public made relocating to less congested

areas with better parking for their customers an increasingly attractive

option for small-volume businesses.

Although cities continued to expand, Americans used their cars

to move in ever-growing numbers to the suburbs. As early as the

1920s suburban growth had begun to rival that of cities, but only after

World War II did American suburbs come into their own. Beginning

in the mid-1940s, huge real estate developers took advantage of new

technology, federally insured home loans, and low energy costs to

respond to the acute housing shortage that returning GIs, the baby

boom, and pent-up demand from the Depression had created. Devel-

opers purchased large land holdings on the border of cities, bulldozed

everything to facilitate new standardized construction techniques,

and rebuilt the landscape from the ground up. Roads and cars, of

course, were essential components of the suburban developers’

visions. So were large yards (which provided the social spaces for

suburbanites that streets had once supplied for urban residents) and

convenient local shopping centers (with plenty of parking). Even the

design of American houses changed to accommodate automobiles,

with more and more architects including carports or integrated

garages as standard features on new homes.

In rural America, the least direct but most far-reaching effects of

widespread car ownership came as rural institutions underwent a

spatial reorganization in response to the increased mobility and range

of the rural population. In the first decade or so of the century,

religious, educational, commercial, medical, and even mail services

consolidated, enabling them to take advantage of centralized distribu-

tion and economies of scale. For most rural Americans, the centraliza-

tion of institutions meant that by mid-century access to motorized

transportation had become a prerequisite for taking advantage of

many rural services.

At about the same time suburban growth exploded in the mid-

1940s, road engineers began to focus on developing the potential of

automobiles for long-distance travel. For the first several decades of

the century, long-distance travelers by automobile had to rely on

detailed maps and confusing road signs to navigate their courses. In

the 1920s, limited-access roads without stop lights or intersections at

grade became popular in some parts of the country, but most people

judged these scenic, carefully landscaped ‘‘parkways’’ according to

their recreational value rather than their ability to move large numbers

of people quickly and efficiently. By 1939, however, designers like

Norman Bel Geddes began to stress the need for more efficient road

planning, as his ‘‘Futurama’’ exhibit at the New York World’s Fair

demonstrated. Over five million people saw his model city, the most

popular display at the exhibition, which featured elevated freeways

and high-speed traffic coursing through its center. Impressed, many

states followed the lead of Pennsylvania, which in 1940 opened 360

miles of high-speed toll road with gentle grades and no traffic lights.

By 1943, a variety of automobile-related interest groups joined

together to form the American Road Builders Association, which

began lobbying for a comprehensive national system of new super-

highways. Then in 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower appointed a

committee to examine the issue of increasing federal road aid—

headed by a member of the General Motors board of directors. Two

years later, Eisenhower signed the Interstate Highway Act, commit-

ting the federal government to provide ninety percent of the cost of a

41,000-mile highway system, the largest peacetime construction

project in history.

The new interstates transformed the ability of the nation’s road

system to accommodate high-speed long-distance travel. As a result,

the heavy trucking industry’s share of interstate deliveries rose from

about fifteen percent of the national total in 1950 to almost twenty-

five percent by the end of the decade, a trend which accelerated the

decentralization of industry that had started before the war. Suburbs

sprang up even farther away from city limits, and Americans soon

began to travel more miles on interstates than any other type of road.

The new highways also encouraged the development of roadside

businesses that serviced highway travelers. A uniform highway

culture of drive-in restaurants, gas stations, and huge regional shop-

ping malls soon developed, all of it advertised on large roadside

billboards. Industries designed to serve motorists expanded, with the

motel industry in particular growing in lock-step with the interstates,

taking advantage of the same increase in family vacations that caused

visits to national parks to double over the course of the 1950s.

While car designers in the 1950s subordinated all other consid-

erations to style and comfort, engineers focused on boosting accelera-

tion and maximum speed. With eager enthusiasm, Americans em-

braced the large, gas-guzzling, chrome-detailed, tail-finned automobiles

that Detroit produced. Teens in particular developed an entire subcul-

ture with automobiles at the center. Cruising the local strip, hanging

out at drive-in restaurants, drag-racing, and attending drive-in movies

all became standard nationwide pastimes.

Yet trouble brewed beneath the surface of the 1950s car culture,

and in the 1960s and 1970s a number of emerging problems drove

home several negative unanticipated consequences of universal car

ownership. Safety concerns, for example, became increasingly im-

portant in the mid-1960s since annual automobile-related deaths had

increased from roughly 30,000 to 50,000 between 1945 and 1965.

Environmental damage, too, became an issue for many Americans,

who focused on problems like air pollution, oil spills, the tendency of

heavy automobile tourism to destroy scenic areas, and the damaging

effects of new road construction on places ranging from urban

neighborhoods to national wilderness preserves.

In both cases, concerned citizens turned to the government to

regulate the automobile industry after less coercive attempts to

address problems failed. In 1965, Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed

galvanized popular concern over motor vehicle safety. Congress

responded in 1966 with the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle

Safety Act, which required a number of safety features on all models

beginning in 1968, despite auto industry protests that regulations

would be expensive and ineffective. Within two years of the imple-

mentation of the law, the ratio of deaths to miles driven had declined

steeply, injuring Americans’ trust in the good faith efforts of industry

to respond to consumer concerns without active regulation. Similarly,

since repeated requests to manufacturers throughout the 1950s to

reduce emissions had failed, California required all new cars from

1966 on to have emissions-reducing technology. Other states fol-

lowed suit, discounting the car industry’s claims that once again

solutions would be slow to develop, expensive, and difficult

to implement.

AUTRY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

142

The most significant example of cultural backlash against the

problems of widespread dependence on automobiles came during and

after the Arab oil embargo of 1973, when the price of crude oil

increased over 130 percent in less than three months. Around the

country, lines of cars snaked out of gas stations, where pump prices

had doubled nearly overnight. Recriminations and accusations about

why the country had become so dependent on foreign oil flew back

and forth—but the major result was that American manufacturers

steadily lost market share after 1973 to small foreign imports that

provided greater fuel-efficiency, cheaper prices, and lower emissions

than Detroit models. Domestic full- and mid-size automobiles, once

the undisputed champions of the United States, lost a substantial

portion of their market share through the 1970s. By 1980, small cars

comprised over 60 percent of all sales within the country.

The widespread cultural discontent with dependence on cars

lasted only as long as the high gasoline prices. Rather than making

changes that would decrease reliance on automobiles, the country

addressed new problems as they arose with complex technological

and regulatory fixes. Oil prices eventually fell to pre-embargo lows in

the 1980s, and by the late 1990s cheap fuel helped reverse the

decades-long trend toward smaller cars. Large sport utility vehicles

with lower fuel efficiency became increasingly popular, and some-

what ironically relied heavily on ‘‘back-to-nature’’ themes in their

marketing strategies. Despite substantial advances in quality and

responsiveness to consumers, American manufacturers never re-

gained their dominance of the immediate postwar years. At the end of

the twentieth century, however, the American car culture itself

continued to be a central characteristic distinguishing the United

States from most other countries around the world.

—Christopher W. Wells

F

URTHER READING:

Berger, Michael. The Devil Wagon in God’s Country: The Automo-

bile and Social Change in Rural America, 1893-1929. Hamden,

Connecticut, Archon Books, 1979.

Flink, James J. America Adopts the Automobile, 1895-1910. Cam-

bridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press, 1970.

———. The Car Culture. Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press, 1975.

Jennings, Jan, editor. Roadside America: The Automobile in Design

and Culture. Ames, Iowa, Iowa State University Press, 1990.

Lewis, David L., and Laurence Goldstein, editors. The Automobile

and American Culture. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan

Press, 1983.

Rae, John Bell. The American Automobile: A Brief History. Chicago,

University of Chicago Press, 1965.

Rose, Mark H. Interstate: Express Highway Politics, 1939-1989.

Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

Scharff, Virginia. Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the

Motor Age. New York, Free Press, 1991.

Sears, Stephen W. The American Heritage History of the Automobile

in America. New York, American Heritage Publishing Compa-

ny, 1977.

Wik, Reynold M. Henry Ford and Grass-Roots America. Ann Arbor,

University of Michigan Press, 1972.

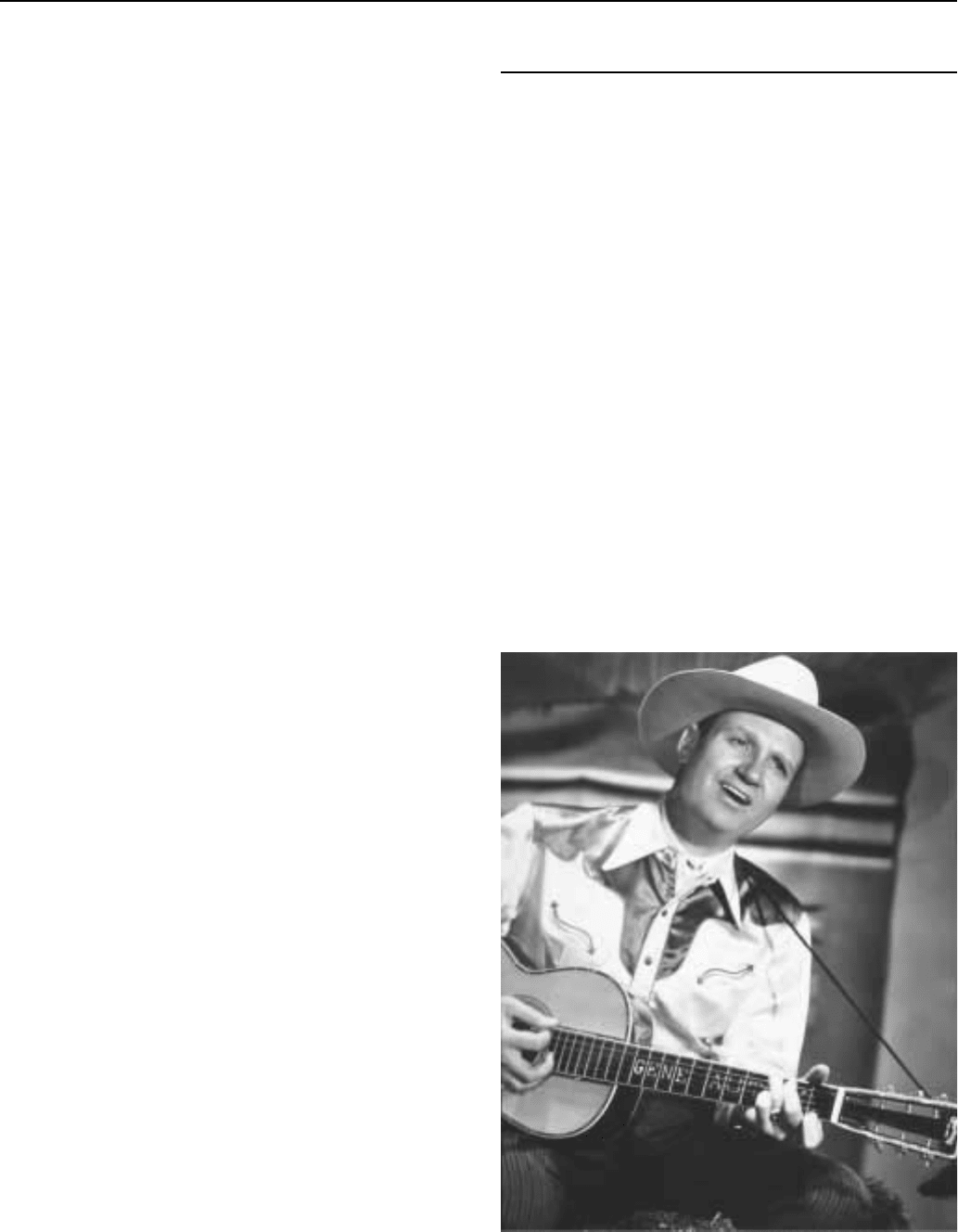

Autry, Gene (1907-1998)

Famous as the original ‘‘Singing Cowboy,’’ Gene Autry rode

the range in the tradition of Tom Mix—clean living, honest, and

innocent. He established the singing cowboy stereotype (continued

by Roy Rogers, who inherited Autry’s sobriquet): that of the heroic

horseman who could handle a guitar or a gun with equal aplomb. A

star of film, radio, and television, Autry was probably best known for

his trademark song, ‘‘Back in the Saddle Again,’’ as well as for many

more of the over 250 songs he wrote in his lifetime.

Born in Texas, Autry moved to Oklahoma as a teenager, and

began working as a telegrapher for the railroad after high school.

While with the railroad, he began composing and performing with

Jimmy Scott, with whom he co-wrote his first hit, ‘‘That Silver-

Haired Daddy of Mine,’’ which sold half a million copies in 1929 (a

record for the period). The same year, he auditioned for the Victor

Recording Company in New York City but was told he needed more

experience. He returned to Tulsa and began singing on a local radio

program, earning the nickname ‘‘Oklahoma’s Yodeling Cowboy.’’

Columbia Records signed him to a contract in 1930 and sent him to

Chicago to sing on various radio programs, including the Farm and

Home Hour and the National Barndance. He recorded a variety of

songs during the 1930s, such as ‘‘A Gangster’s Warning,’’ ‘‘My Old

Pal of Yesterday,’’ and even the labor song ‘‘The Death of

Mother Jones.’’

In 1934, Autry began appearing in films as a ‘‘tuneful cow-

puncher’’ and made numerous highly successful pictures with his

Gene Autry

AVALONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

143

horse, Champion, before he retired from the film industry in the

1950s. His debut film was In Old Santa Fe, in which he made only a

brief singing appearance, but reaction to his performance was favor-

able and it got him a lead role in the 13-part serial Phantom Empire.

His first starring role in a feature film followed with Tumblin’

Tumbleweeds (1935), and he became not only Republic Pictures’

reigning king of ‘‘B’’ Westerns, but the only Western star to be

featured on the list of top ten Hollywood moneymakers between 1938

and 1942. Autry’s pictures are notable for the smooth integration of

the songs into the plots, helping to move the action along. Some of his

films were even built around particular songs, among them Tumblin’

Tumbleweeds, The Singing Cowboy (1937), Melody Ranch (1940)

and Back in the Saddle (1941).

After serving as a technical sergeant in the Army Air Corps

during World War II, Autry returned to Hollywood to make more

films. From film, Autry made the transition into both radio and

television programming. He hosted the Melody Ranch show on radio

(and later on television), and he was involved with numerous success-

ful television series, including The Gene Autry Show (1950-56) and

The Adventures of Champion (1955-56). A masterful merchandiser,

he developed a lucrative and hugely successful lines of clothes, comic

books, children’s books, and toys, while at the same time managing

and touring with his own rodeo company. In addition to his country

songs, Autry wrote numerous other popular songs, including ‘‘Frosty

the Snowman,’’ ‘‘Peter Cottontail,’’ and, most famously, the endur-

ing ‘‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.’’ Thanks to his financial

success, Autry was able to buy the California Angels baseball team

and served as a vice president of the American Baseball League for

many years.

Like Tom Mix before him, Autry’s public image stressed strong

morals and honesty, and fueled the romantic image of the American

cowboy. His ten-point ‘‘Cowboy Code’’ featured such sincere advice

as ‘‘The Cowboy must never shoot first, hit a smaller man, or take

unfair advantage’’; ‘‘He must not advocate or possess racially or

religiously intolerant ideas’’; ‘‘He must neither drink nor smoke’’;

and ‘‘The Cowboy is a patriot.’’ Gene Autry was elected to the

Country Music Hall of Fame 1969, 29 years before his death at the

age of 91.

—Deborah M. Mix

F

URTHER READING:

Autry, Gene. The Essential Gene Autry. Columbia/Legacy Rec-

ords, 1992.

Autry, Gene, with Mickey Herskowitz. Back in the Saddle Again.

Garden City, New York, Doubleday, 1978.

Rothel, David. The Gene Autry Book. Madison, North Carolina,

Empire Publishing, 1988.

Avalon, Frankie (1939—)

During the late 1950s, as record producers and promoters rushed

to capitalize on the potent youth market, they aggressively sought out

clean-cut young males to mold into singing stars. Seeking to fill a void

that had been created in part by the absence of Elvis Presley, who was

then a G.I. stationed in Germany, they purposely toned down the

controversial aspects of the new musical form, rock ’n’ roll. Unlike

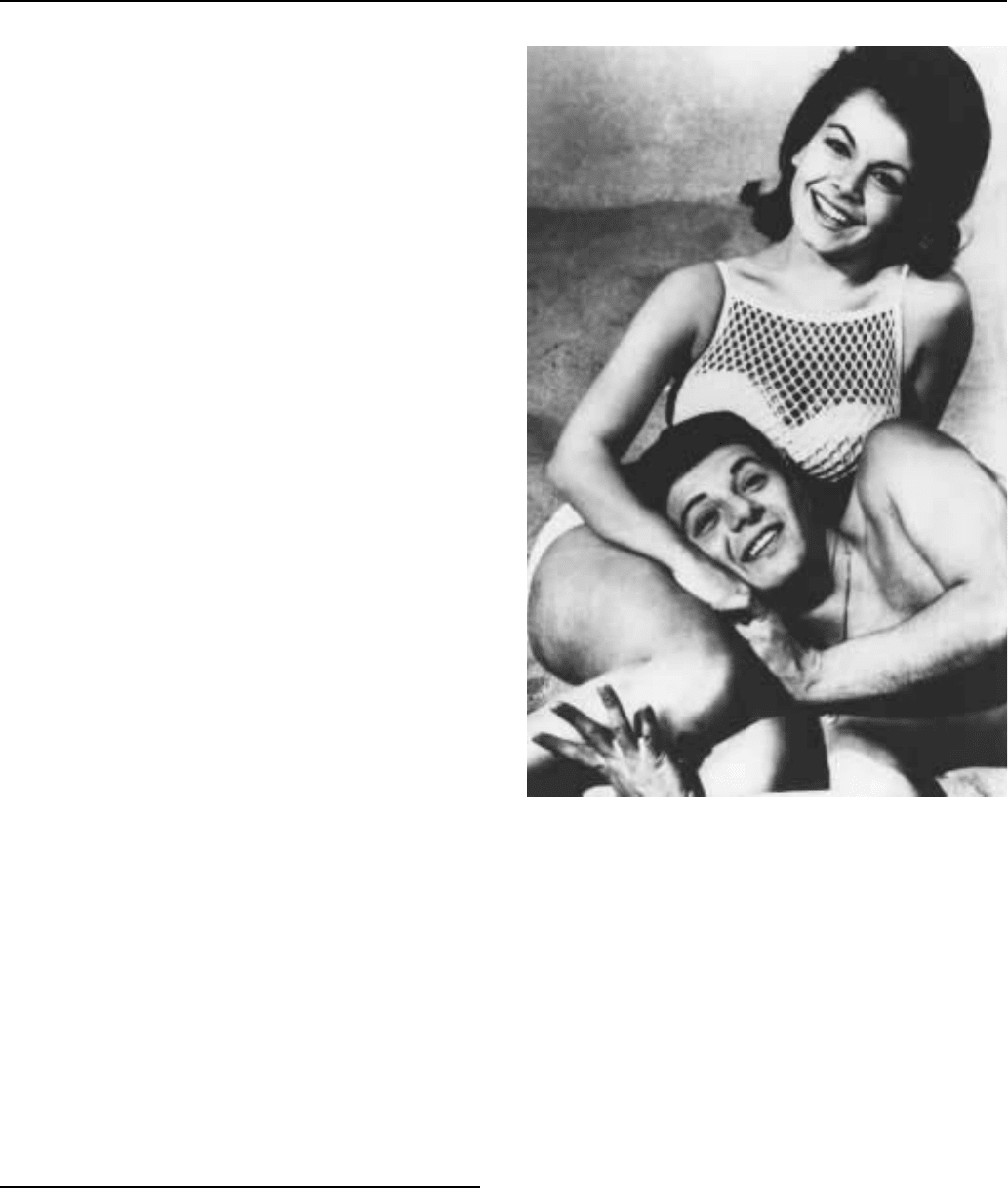

Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello

Presley, who emoted a powerful sexuality, the manufactured teen

idols elicited a friendly, non-threatening demeanor. The engaging

Frankie Avalon, whose skinniness prompted comparisons to an

earlier generation’s teen idol, Frank Sinatra, perfectly filled that bill.

As he once explained, ‘‘I was one of those guys who there was a

possibility of dating . . . I had a certain innocence.’’

A native of South Philadelphia, Francis Thomas Avallone was

just eleven when he talked his father into buying him a thirty-five-

dollar pawn shop trumpet (after seeing the 1950 Kirk Douglas movie,

Young Man with a Horn). Avalon went on to appear in local talent

shows, including the program TV Teen Club. The show’s host, Paul

Whiteman, christened him ‘‘Frankie Avalon.’’

A meeting with singer Al Martino led to an introduction to a New

York talent scout, who in turn arranged an audition with Jackie

Gleason. After appearing on Gleason’s TV show, additional national

shows followed, as did a contract with an RCA subsidiary label. For

his first two records—the instrumentals ‘‘Trumpet Sorrento’’ and

‘‘Trumpet Tarantella’’—the performer was billed as ‘‘11-year-old

Frankie Avalon.’’ He was twelve when he became the trumpet player

for the South Philadelphia group, Rocco and the Saints, which also

included Bobby Rydell on drums. As a member of the Saints, Avalon

AVEDON ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

144

performed at local clubs, on local television, and even toured Atlantic

City. The talented trumpeter also sometimes doubled as the group’s

singer. As a result of one such performance he caught the attention of

Bob Marcucci and Peter De Angelis, owners of Chancellor Records.

In 1958 Avalon signed a contract with their label, and went on to be

managed by Marcucci, who also handled Fabian.

Though his first two Chancellor records were unsuccessful,

Avalon enjoyed a hit with his third effort, ‘‘Dede Dinah,’’ which he

performed while pinching his nose for a nasal inflection. Though the

record went gold, it was with the 1959 ‘‘Venus’’ that Avalon enjoyed

his biggest success. Recorded after nine takes, and released three days

later, it sold more than a million copies in less than one week.

Along with other heartthrobs of the day, Avalon became a

frequent guest artist on American Bandstand. And like his teen idol

brethren, including Philadelphia friends Fabian and Rydell, he headed

to Hollywood where he was given co-starring roles alongside respect-

ed veterans. In Guns of the Timberland he shared the screen with Alan

Ladd; in The Alamo he joined an all-star cast, led by John Wayne.

In the early 1960s, Avalon used his affable, clean-cut image to

clever effect as the star and a producer of the Beach Party movies, in

which he was sometimes romantically teamed with another former

1950s icon and close friend Annette Funicello. Made by the youth-

oriented American International Pictures, the movies were filmed in

less than two weeks, on shoestring budgets, and featured a melange of

robust young performers, musical numbers, surfing, drag racing, and

innocuous comedy. Despite the preponderance of bikini-clad starlets,

the overall effect was one of wholesome, fun-loving youth. But in

fact, the young people of the decade were on the verge of a counter-

culture revolution. When it happened, Avalon, like many others who

got their start in the 1950s, was passé.

He attempted to change his image by appearing in low-budget

exploitation movies such as the 1970 Horror House. But despite his

rebellion at what he once called ‘‘that damn teen idol thing,’’ it was

precisely that reputation that propelled his comeback. In the 1976

movie version of Grease, which celebrates the 1950s, Avalon seem-

ingly emerges from heaven to dispense advice in the stand-out

musical number, ‘‘Beauty School Dropout.’’ Avalon’s cameo ap-

pearance generated so much attention that he went on to record a

disco-version of ‘‘Venus.’’ He further capitalized on his early image

with the 1987 movie, Back to the Beach, in which he was reunited

with Funicello.

Avalon, who is the father of eight and a grandfather, has also

capitalized on his still-youthful looks to market a line of beauty and

health care products on the Home Shopping Nework. In addition, he

performs in the concert tour ‘‘The Golden Boys of Rock ’n’ Roll,’’ in

which he and Fabian and Rydell star.

—Pat H. Broeske

F

URTHER READING:

Bronson, Fred. The Billboard Book of Number One Hits. New York,

Billboard Publications, 1988.

Miller, Jim, editor. The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock &

Roll. New York, Random House, 1980.

Whitney, Dwight. ‘‘Easy Doesn’t Do It—Starring Frankie Avalon.’’

TV Guide. August 21, 1976, 14-17.

Avedon, Richard (1923—)

Richard Avedon added new depth to fashion photography begin-

ning in 1945. His fashion photographs—in Harper’s Bazaar, 1945-

66, and in Vogue, 1966-90—were distinctive in expressing both

motion and emotion. Avedon imparted the animation of streets,

narrative, and energy to the garment. His most famous fashion image,

Dovima with Elephants (1955), is an unabashed beauty-and-the-beast

study in sexuality. By the 1950s, Avedon also made memorable non-

fashion images, including a 1957 portrait of the Duke and Duchess of

Windsor in vacant melancholy, 1960s heroic studies of Rudolf

Nureyev dancing nude, and 1960s epics of the civil rights movement

and mental patients at East Louisiana State Hospital. Although

Avedon’s photographs moved away from fashion toward the topical,

social, and character-revealing, the common theme of all his photog-

raphy has been emotion, always aggressive and frequently shocking.

—Richard Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Avedon, Richard. An Autobiography. New York, Random House, 1993.

Evidence, 1944-1994 (exhibition catalogue). New York, Whitney

Museum of American Art/Random House, 1994.

The Avengers

The Avengers (which appeared on ABC from 1961 to 1969) has

the distinction of being the most popular British television series to

run on an American commercial network, and was the first such series

to do so in prime time. Sophisticated, tongue-in-cheek, but never

camp or silly, The Avengers was also one of the first and best of the

soon-to-be-popular television spy series, and varied in tone from

crime melodrama to outright science fiction. Every episode starred

John Steed (Patrick Macnee), an urbane British intelligence agent

who heads a mysterious elite squad known as the Avengers, so named

for their propensity to right wrongs.

The first four seasons of the show were not run in the United

States, but were videotaped and aired only in Britain. The series began

as a follow-up to Police Surgeon (1960), which starred Ian Hendry as

a doctor who helped the police solve mysteries. Sydney Newman, the

head of programming at ABC-TV in England, wanted to feature

Hendry in a new series that would pair him as Dr. David Keel with a

secret agent, John Steed, in a fight against crime.

Patrick Macnee had had a successful acting career in Canada and

Hollywood, but when he returned to England, he was unable to find

work as an actor. An old friend got him a position as an associate

producer on The Valiant Years (1960-63) about Winston Churchill,

and Macnee soon found himself producing the entire show. He

planned on remaining a producer when he was asked to star in The

Avengers (on which he initially received second billing) and asked for

a ridiculously high salary, expecting the producers to reject it. When

they didn’t, Steed was born.

Though he initially used a gun, Macnee quickly altered the

character, which he saw as a combination of the Scarlet Pimpernel, his

father, Ralph Richardson, and his C.O. in the Navy. As the series went

on, Steed appeared more and more as a well-dressed, upper crust fop

with more than a soupçon of charm, dash, and derring-do. Apart from

AVERYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

145

his fighting skills, with the third season his chief weapon became his

umbrella, which he used variously as a camera, a gas projector, a

sword case, and a tape recorder.

After two seasons, Hendry bowed out and Honor Blackman was

hired to be Steed’s first female sidekick, anthropologist Cathy Gale,

whom Blackman modeled after Life magazine photographer Marga-

ret Bourke-White with a dash of Margaret Mead. Initially, Gale was

given a pistol which could be hidden in her make-up kit or under her

skirt, but it was eventually decided this was too unwieldy. Miniature

swords and daggers were briefly tried when Leonard White urged that

Blackman take up judo seriously and arranged for her to be trained by

Douglas Robinson.

The action-oriented series required that Blackman have at least

one fight scene in every episode, and Blackman soon became adept at

judo. White wanted Cathy to be pure, a woman who fought bad guys

because she cared so much about right and justice, as a contrast to

Steed’s wicked, devilish, and saucy nature. Blackman added to the

character by dressing her in leather simply because she needed clothes

that would not rip during the fight scenes (at the beginning of the

series, she once ripped her trousers in close-up). Because the only

thing that went with leather pants were leather boots, she was given

calf-length black boots and inadvertently started a kinky fashion

trend. (In fact, Macnee and Blackman released a single celebrating

‘‘Kinky Boots’’ on Decca in 1964).

However, after two years, Blackman likewise decided to call it

quits to concentrate on her movie career (she had just been cast as

Pussy Galore in Goldfinger [1964]). The surprised producers searched

frantically for a replacement, at first choosing Elizabeth Shepherd,

but after filming one-and-a-half episodes she was replaced by Diana

Rigg, who played Mrs. Emma Peel (named after the phrase ‘‘M

Appeal’’ for ‘‘Man Appeal,’’ which was something the character was

expected to have). Rigg and Macnee proved to have tremendous

chemistry and charm together, with their sexual relationship largely

left flirtatious and ambiguous. Rigg, like Blackman, played a tough,

capable female fighter who possessed both high intelligence and

tremendous sex appeal. Her outlandish costumes (designed by John

Bates) for the episodes ‘‘A Touch of Brimstome’’ and ‘‘Honey for the

Prince’’ were especially daring (and in fact, ABC refused to air these

and three other episodes of the British series, considering them too

racy, though they later appeared in syndication).

The two years with Diana Rigg are universally considered the

best in the series, which ABC in the United States agreed to pick up

provided the episodes were shot on film. Albert Fennell now pro-

duced the series and served as its guiding light, with writers Brian

Clemens and Philip Levene writing the majority and the best of the

episodes. These new shows became more science-fiction oriented,

with plots about power-mad scientists bent on ruling the world, giant

man-eating plants from outer space, cybermen, androids and robots,

machines that created torrential rains, personalities switching bodies,

people being miniaturized, and brainwashing. The fourth season and

all subsequent episodes were filmed in color.

Commented Clemens about the series, ‘‘We admitted to only

one class—and that was the upper. Because we were a fantasy, we

have not shown policemen or coloured men. And you have not seen

anything as common as blood. We have no social conscience at all.’’

Clemens also emphasized the Britishness of the series rather than

trying to adapt it to American tastes, feeling that helped give the show

a unique distinction.

Rigg called it quits after two seasons, and she also joined the

Bond series, having the distinction of playing Mrs. James Bond in On

Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969). The series limped on for a final

season with Steed’s new partner Tara King (played by Linda Thorson),

also known as Agent 69, who always carried a brick in her purse. The

last season also introduced us to Mother (Patrick Newell), Steed’s

handicapped boss, and his Amazonian secretary Rhonda (Rhonda

Parker). The running gag for the season was that Mother’s office

would continually turn up in the most unlikely of places and the plots

were most often far-fetched, secret-agent style plots.

The series later spawned a stageplay, The Avengers on Stage,

starring Simon Oates and Sue Lloyd in 1971, a South African radio

series, a series of novel adventures, a spin-off series, The New

Avengers (starring Macnee, Gareth Hunt, and Joanna Lumley) in

1976, and finally a 1998 big-budgeted theatrical version starring

Ralph Fiennes as John Steed and Uma Thurman as Emma Peel. The

latter was greeted with universally derisive reviews and was consid-

ered a debacle of the first order as it served to remind everyone how

imitators had failed to capture the charm, wit, escapism, and appeal of

the original series, which has long been regarded as a television classic.

—Dennis Fischer

F

URTHER READING:

Javna, John. Cult TV: A Viewer’s Guide to the Shows America Can’t

Live Without!! New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

Macnee, Patrick, and Marie Cameron. Blind in One Ear: The Avenger

Returns. San Francisco, Mercury House, 1989.

Macnee, Patrick, with Dave Rogers. The Avengers and Me. New

York, TV Books, 1998.

Rogers, Dave. The Complete Avengers. New York, St. Martin’s

Press, 1989.

Avery, Tex (1908-1980)

Tex Avery, one of the most important and influential American

animators, produced dozens of cartoon masterpieces primarily for the

Warner Brothers and Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer (MGM) studios from

the 1930s to the 1950s. Frenetic action, perfect comedic timing, and a

never-ending stream of sight gags characterize his short, animated

films. He is credited with providing the most definitive characteriza-

tion of Bugs Bunny and creating such classic cartoon figures as

Droopy, Chilly Willy, Screwy Squirrel, and Red Hot Riding Hood.

Avery was most intrigued by the limitless possibilities of animation

and filled his work with chase sequences, comic violence, and

unbelievable situations that could not be produced in any other

medium. Avery’s manic style was best described by author Joe

Adamson when he stated, ‘‘Avery’s films will roll along harmlessly

enough, with an interesting situation treated in a more or less funny

way. Then, all of a sudden, one of the characters will lose a leg and

hop all over the place trying to find it again.’’

Born Frederick Bean Avery on February 26, 1908, in Taylor,

Texas, a direct descendant of the infamous Judge Roy Bean, Avery

hoped to turn his boyhood interest in illustration into a profession

when he attended the Chicago Art Institute. After several failed

attempts to launch a syndicated comic strip, he moved to California

and took a job in Walter Lanz’s animation studio. Avery’s talent as an

AVON ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

146

animator led him to join the Warner Brothers studio in 1935. There, he

became a leading member of a unit including now legendary anima-

tors Chuck Jones and Bob Clampett. From their dilapidated headquar-

ters on the studio lot, which they dubbed the Termite Terrace, the

young artists set about creating a new cartoon sensibility which was

more adult, absurd, and filled with slapstick. Avery and his crew’s

characters were more irreverent than those of their Disney competi-

tors and the cartoons themselves were marked by direct addresses to

the audience, split screen effects, and abrupt changes in pacing. Avery

also insisted that their films acquire a more satiric tone so as to

comment on contemporary popular culture. An early example of this

satire is found in I Love to Singa (1936), which features ‘‘Owl

Jolson’’ in a take-off of The Jazz Singer. Avery constantly reminded

his viewers of the illusionary nature of animation. Unlike Disney,

which was known for its spectacle, Avery’s Warner Brothers films

highlight their unreality. This abundant self-reflexivity is considered

an early example of animated postmodernism.

Avery’s talent also extended into the area of characterization.

He, along with Jones and Clampett, refined an existing character

named Porky Pig and transformed him into the first popular Looney

Tunes character of the 1930s. In a 1937 cartoon called Porky’s Duck

Hunt he introduced Daffy Duck, who became so popular that he soon

earned his own cartoon series. Avery’s greatest contribution to

animation, however, was his development of Bugs Bunny. A crazy

rabbit character had appeared in several Warner cartoons beginning in

1938, but with few of the later Bugs personality traits. Animation

historians regard Avery’s 1940 cartoon A Wild Hare as the moment

Bugs Bunny was introduced to America. Avery had eliminated the

earlier rabbit’s cuteness and craziness and, instead, fashioned an

intelligent, streetwise, deliberate character. It was also in this cartoon

that Avery bestowed upon Bugs a line from his Texas childhood—

‘‘What’s up, doc?’’—that would become the character’s catchphrase.

Avery’s style became so important to the studio and imitated by his

colleagues that he became known as the ‘‘Father of Warner

Bros. Cartoons.’’

Despite all his success at Warner Brothers, Avery’s most crea-

tive period is considered to be his time producing MGM cartoons

from 1942 to 1954. In these films he dealt less with characterization

and concentrated on zany gags. This fast-paced humor was developed

to accommodate Avery’s desire to fit as many comic moments as

possible into his animated shorts. The MGM films feature nonde-

script cats and dogs in a surreal world where anything can, and does,

happen. The 1947 cartoon King-Size Canary is regarded as Avery’s

masterpiece and reveals the lunacy of his later work. The film features

a cat, mouse, dog, and canary each swallowing portions of ‘‘Jumbo-

Gro.’’ The animals chase each other and grow to enormous heights.

Finally, the cat and mouse grow to twice the earth’s size and are

unable to continue the cartoon. They announce that the show is over

and simply wave to the audience. Avery once again revealed the

absurdities inherent to the cartoon universe.

In 1954, Avery left MGM and began a career in commercial

animation. He directed cartoon advertisements for Kool-Aid, Pepsodent,

and also produced the controversial Frito Bandito spots. Indeed, his

animation has been enjoyed for more than half a century due to its

unique blend of absurdity, quick humor, and fine characterization. He

inspired his peers and generations of later animators to move their art

form away from the saccharine style embodied by Disney. He

revealed that animation is truly limitless. Because of his ability to

create cartoons with an adult sophistication mixed with intelligent

and outlandish humor, he has often been characterized as a ‘‘Walt

Disney who has read Kafka.’’

—Charles Coletta

F

URTHER READING:

Adamson, Joe. Tex Avery: King of Cartoons. New York, De Capo

Press, 1975.

Schneider, Steve. That’s All Folks!: The Art of Warner Bros. Anima-

tion. New York, Henry Holt & Co., 1988.

Avon

American cosmetic and gift company Avon Products, Inc. is

known for its eye-catching, digest-sized catalogs shimmering with

fresh-faced models wearing reasonably priced makeup and advertis-

ing costume jewelry, colognes, and an array of other items. Their

goods are backed by a satisfaction guarantee and delivered by a

friendly face, usually female, who earns or supplements an income by

the commission received. Avon’s retail concept, symbolized by the

direct-sales ‘‘Avon lady,’’ is a cherished part of American culture,

and now, a recognized addition to countries around the globe as well.

In the 1990s, Avon was the world’s top direct-sales cosmetics firm,

with a total work force of 2.6 million in over 130 countries, producing

sales of $4.8 billion ($1.7 billion in the United States alone). Ninety

percent of American women have purchased Avon products in their

lifetime, most likely because of the convenience, price, and quality,

but perhaps also due to the history of female fraternity and

empowerment that Avon promotes. The company’s overwhelmingly

female employee base and tradition of visiting customers in their

homes allowed women control of their own earnings long before it

was widely accepted.

Avon was founded in 1886, and Mrs. P.F.E. Albee of Winches-

ter, New Hampshire, originated the idea of going door-to-door to push

her wares. The company offered a money-back guarantee on their

products and the salespeople nurtured relationships with customers,

minimizing the need for advertising. The company prospered with

their pleasant, neighborly image and low-cost, dependable products.

However, in the 1970s and 1980s Avon’s fortunes declined when a

number of unsavvy business moves hurt sales and provoked an

exodus of salespeople. At that time, the company also suffered from

its outdated approach: Women were no longer waiting at home for the

doorbell to ring; they were at work all day. In 1993, Avon began

boosting morale and incentives for salespeople, then updated its

image, and in 1998 launched a $30 million advertising campaign. The

company recruited a bevy of new representatives who would sell in

offices and other business settings, and they focused on a more

desirable product line. In addition, Avon reached out overseas,

prompting women in South American, Russia, Eastern Europe, and

China to sign up as salespeople. In fact, the number of Avon

representatives in Brazil—478,000—is more than twice that of Bra-

zil’s army, with 200,000 soldiers. Avon’s strategies sharply increased

profits and swelled its stock.

Though the cherished but politically incorrect term ‘‘Avon

lady’’ is not quite accurate—two percent of the force is male—the

company still primarily consists of women selling cosmetics to

female friends, family members, neighbors, and coworkers, with 98

percent of its revenue coming from direct sales. Avon used the slogan

AYKROYDENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

147

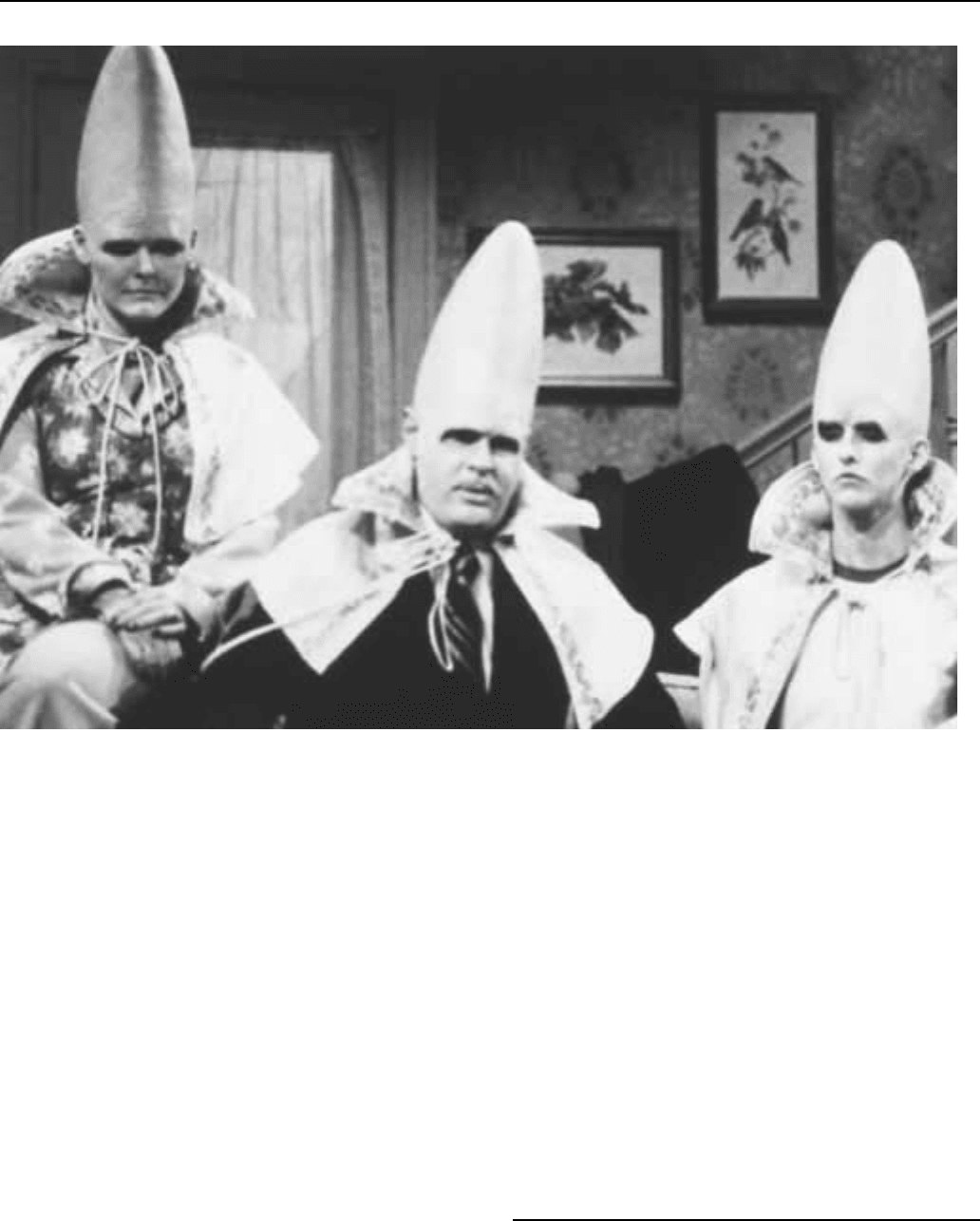

Dan Aykroyd (center) with Jane Curtin (left) and Laraine Newman (right) in the popular Conehead skit on Saturday Night Live.

‘‘Avon calling!’’ accompanied by a ‘‘ding-dong’’ doorbell noise

when it was known mainly for reaching clients at home before the rise

of women in the work force. However, the company in 1996 sold

about 50 percent of its goods in the workplace, and branched out to

offer a more extensive line of gifts for time-constrained working

women. Although Avon has traditionally carried skin care and other

hygiene products as well as cologne and jewelry for women, men, and

children, in the 1990s it expanded its selection greatly to become a

convenient way to shop for knick-knacks, toys, clothing and lingerie,

books, and videos.

Though management ranks were off-limits to women until

roughly the 1980s, Avon has quickly risen to become known for its

respected record in the area of female promotions. In 1997, however,

some were rankled when Christina Gold, president of North Ameri-

can operations, was slighted for a promotion to CEO in favor of an

outside male candidate. She later resigned. Despite this incident,

Working Woman magazine still called Avon one of the top female-

friendly firms in 1998 due to its largely female employee base and

number of corporate women officers. Overall, only three percent of

top executives at Fortune 500 companies in 1997 were women. At

Avon, on the other hand, over 30 percent of corporate officers are

women, and four of the eleven members of the board of directors are

women. Avon also has a good record of promoting women, with more

women in management slots—86 percent—than any other Fortune

500 firm. The company is also heavily involved in supporting

research for breast cancer.

—Geri Speace

F

URTHER READING:

Morris, Betsy. ‘‘If Women Ran the World, It Would Look a Lot Like

Avon.’’ Fortune. July 21, 1997, 74.

Reynolds, Patricia. ‘‘Ding Dong! Avon Lady Is Still Calling.’’ Star

Tribune. September 9, 1996, 3E.

Stanley, Alessandra. ‘‘Makeover Takeover.’’ Star Tribune, August

21, 1996, 1D.

Zajac, Jennifer. ‘‘Avon Finally Glowing Thanks to Global Sales—

And New Lip-Shtick.’’ Money. September 1997, 60.

Aykroyd, Dan (1952—)

Actor and writer Dan Aykroyd achieved stardom as a member of

the original Saturday Night Live (SNL) ‘‘Not Ready for Prime Time

Players.’’ During his tenure on SNL, he created some of the show’s

AYKROYD ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

148

classic skits and impersonations. He also memorably teamed up with

SNL’s John Belushi to perform as Elwood ‘‘On a Mission from God’’

Blues, one half of the ‘‘The Blues Brothers’’ band. Aykroyd is one of

the busiest actors on screen. Since SNL, Aykroyd has appeared in

more than twenty movies, including Ghostbusters (1984), which he

also wrote, Driving Miss Daisy (1989), and two movies based on the

SNL act, The Blues Brothers (1980) and Blues Brothers 2000 (1998).

He also stars, as an ex-biker priest, in the TV sitcom Soul Man, and

fronts a successful syndicated series, Psi Factors. Additionally, he is

also a highly productive writer, continuing to pen some of Holly-

wood’s most successful comedies.

—John J. Doherty

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Aykroyd, Dan.’’ Current Biography Yearbook. New York,

Wilson, 1992.